Enemy strategies in turn-based games should be surprising and unpredictable. This study introduces Mirror Mode, a new game mode where the enemy AI mimics the personal strategy of a player to challenge them to keep changing their gameplay. A simplified version of the Nintendo strategy video game Fire Emblem Heroes has been built in Unity, with a Standard Mode and a Mirror Mode. Our first set of experiments find a suitable model for the task to imitate player demonstrations, using Reinforcement Learning and Imitation Learning: combining Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning, Behavioral Cloning, and Proximal Policy Optimization. The second set of experiments evaluates the constructed model with player tests, where models are trained on demonstrations provided by participants. The gameplay of the participants indicates good imitation in defensive behavior, but not in offensive strategies. Participant's surveys indicated that they recognized their own retreating tactics, and resulted in an overall higher player-satisfaction for Mirror Mode. Refining the model further may improve imitation quality and increase player's satisfaction, especially when players face their own strategies. The full code and survey results are stored at: https://github.com/YannaSmid/MirrorMode.

In video games, non-playable character (NPC) behavior has relied on artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms for decades [23]. Now, with the quick advancements made in AI, new possibilities are found to enhance the behavior of NPCs, to increase the quality of a video game. NPC behavior refers to how characters in games should act and react to certain events in the game environment. Realistic NPC behavior contributes significantly to the player immersion and satisfaction of the game [16]. Traditionally, these behavior types are handled by Finite State Machines (FSM) or Behavior Trees (BT), where each character follows a set of predefined heuristics and transitions between states based on game events [8]. Nevertheless, this method of programmable behavior can result in repetitive behavior that makes NPCs predictable in their actions [1,17].

In strategy games, predictability in enemy tactics can have a major influence on player experience. Strategy games require tactical thinking to defeat a team of opponents, while keeping your own team alive. Statistics in 2024 have shown that the popularity of strategy games has drastically decreased in the past 9 years [28]. This may be linked to the predictability of the enemy’s action as it makes games easier to play, possibly reducing the engagement of more experienced players [1]. In addition to this, it is found that playing several repetitive games can cause boredom [5].

Therefore, this study aims to address the risk of boredom in strategy video games by introducing Mirror Mode, a new game mode where the enemy NPCs learn a strategy based on the player’s strategy through Imitation Learning (IL) [20]. A simplified version of the mobile strategy game Fire Emblem Heroes [21] was developed, to apply combinations of Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL), Behavioral Cloning (BC), and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), in order to train agents. The performance of the algorithms are assessed through ablation and optimization experiments, where the best configuration of algorithms and their hyperparameters were used for further evaluations through user studies. The conducted user studies evaluated the performance of the trained agents and their imitation quality. The research aims to answer the central research question: How will a player’s game experience be influenced when NPCs imitate their strategy in a turn-based strategy game?

With the results of the finetuning experiments the study aims to further explore the sub-question: “To what extent can reinforcement learning (RL) and imitation learning (IL) be applied to teach NPCs the strategy of a player in a turn-based strategy game?”

Altogether, the study provides an innovative method of playing strategy games, and offers insights into the effectiveness of IL and RL for large discrete spaces, to imitate individual player strategies.

The key contributions of this study are as follows.

• We implement a new strategy game where agents are trained using Behavioral Cloning, Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning, and Reinforcement Learning. • We report the first evidence of behavior cloning in a player’s strategy in a turn-based game. • Users report higher satisfaction with the game through the increased interaction.

Maintaining a balance between the skills of a player and the difficulty of the game is a key principle in game design, to influence the player’s engagement and satisfaction. According to Csíkszentmihályi’s flow theory, an individual is most engaged when the challenge of an activity is well aligned to their skill level, creating an optimal state of focus and satisfaction [7,13]. However, game experience is also shaped by the motivation to play a game, which differs for each player. Players who focus primarily on achieving in-game objectives tend to be more satisfied with smooth and accessible gameplay, while those who play for enjoyment are more engaged by challenging and exciting gameplay [6]. This highlights the difficulty of creating a single game experience that satisfies all types of players. Many game developers provide adjustable difficulty settings, allowing players to match the challenge to their abilities as they play. However, frequently adjusting the difficulty can break immersion and disrupt the player’s sense of flow, making it harder for them to stay engaged over time [13]. Researchers are therefore finding a more suitable method for adapting difficulty in video games, with smarter AI algorithms.

Building onto the difficulty settings of video games, AI offers new methods in order to maintain a player’s satisfaction.

Early work by Sanchez-Ruiz et al. explored NPC adaptation in the turn-based strategy game Call to Power2, using an ontological approach [22]. Agents retrieve actions by looking up similar states in a library, with stored previously used tactics. While it proved effective in improving decision-making speed and accuracy, the approach was limited in adapting to entirely new conditions and involved computational complexity due to its ontology-based reasoning.

Research by Akram et al. has shown that the player satisfaction has improved after the implementation of AI driven mechanics for the animation of NPCs, to improve the realism in their behavior. They suggest that further improvement on the game satisfaction can include using AI for the adaptability of NPCs on player’s gaming behavior [1].

Whilst several studies have explored AI’s potentials for NPC behavior adaptation, little research has built on the idea to train agents based on real-time player strategies to improve the tactics adaptation in strategy video games. Strategy video game environments are considerably complex, making it challenging to train computationally demanding AI algorithms such as RL [29].

Researchers explored a wider range of possibilites of RL for adaptive behavior. OpenAI Five was the first AI system that was able to defeat professional players in the multiplayer real-time strategy game Dota 2 [18]. Through deep RL and self-play, the algorithm succeeded in defeating the world champions in the game, marking it a great success for the use of RL in real-time strategy games. Continuing on this work, OpenAI demonstrated the adaptability of agents while letting them play a game of hide-and-seek, through self-play [4]. The research applied PPO and Generalized Advantage Estimation to optimize their policy. It was found that through self-play, agents learned to develop counter-strategies to earlier discovered in-game strategies.

Amato and Shani further investigate adaptive strategy behavior for NPCs, in the turn-based strategy game Civilization [2]. They applied Q-learning and Dyna-Q for switching between strategies given the current game situation. Their results show high potential for the use of RL to teach agents specific strategies, and the authors encourage investigating the use of more advanced RL approaches in the future.

According to research by Zare et al., IL offers a more advanced RL approach in complex learning environments, by incorporating human demonstrations to teach agents the targeted behavior [29].

Ho and Ermon introduced Generative Adversarial Inverse Learning (GAIL), an adversarial approach that enables policy training from expert demonstrations without explicit reward systems [12]. Subsequently, Gharbi and Fennan compared GAIL with alternative IL and RL algorithms including PPO and BC, finding it highly effective at replicating complex player strategies [11]. They further suggest that combining GAIL with model-free RL methods could yield adaptive game AI capable of both imitation and responsiveness, a claim that this study is going to investigate further by incorporating GAIL with PPO.

While prior work has not examined RL and IL techniques for imitating player behavior in turn-based strategy games specifically, the aforementioned existing research highlights the potential of integrating AI in video games to produce a more adaptive and engaging game experience. The studies motivate examining the effects of PPO, BC, and GAIL combined in strategy video games. Accordingly, this study further explores the application of IL in strategic game environments to find the opportunities of creating more adaptable agents that copy strategies.

This study developed a game environment to investigate the impact of an enemy AI that imitates player behavior. The technical setup as well as the implementation and design of the game environment is explained in this section, details on the agent AI can be found in the next section.

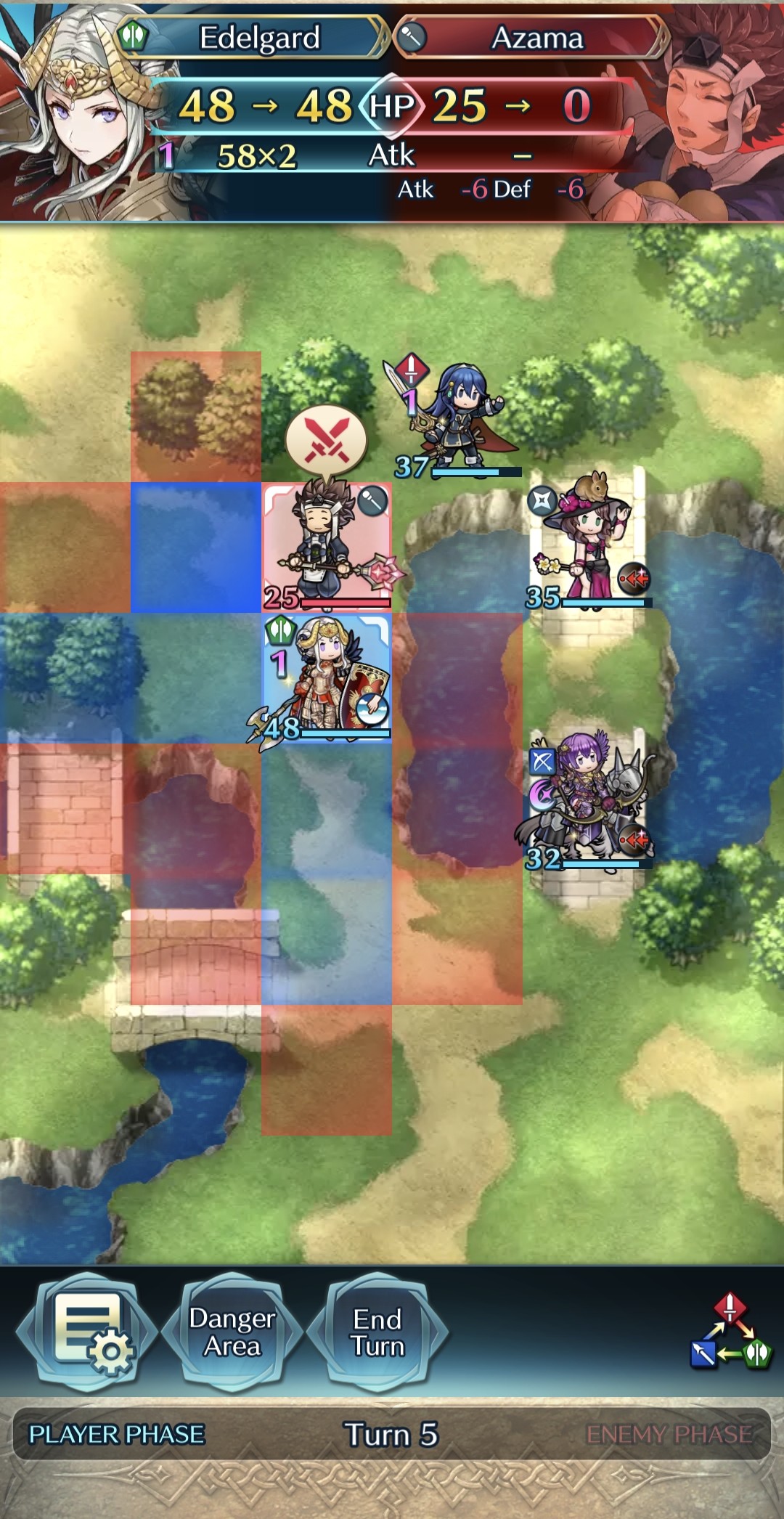

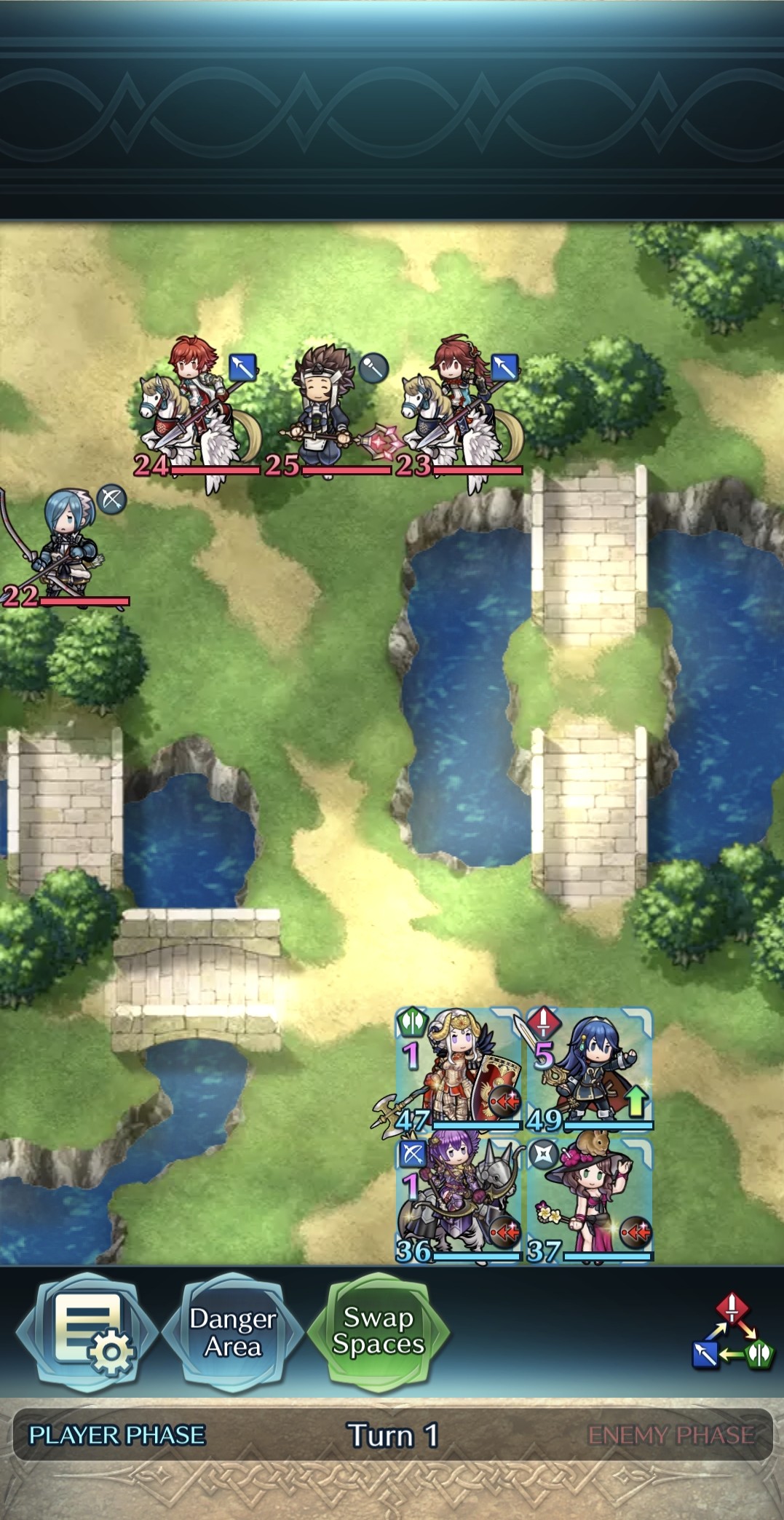

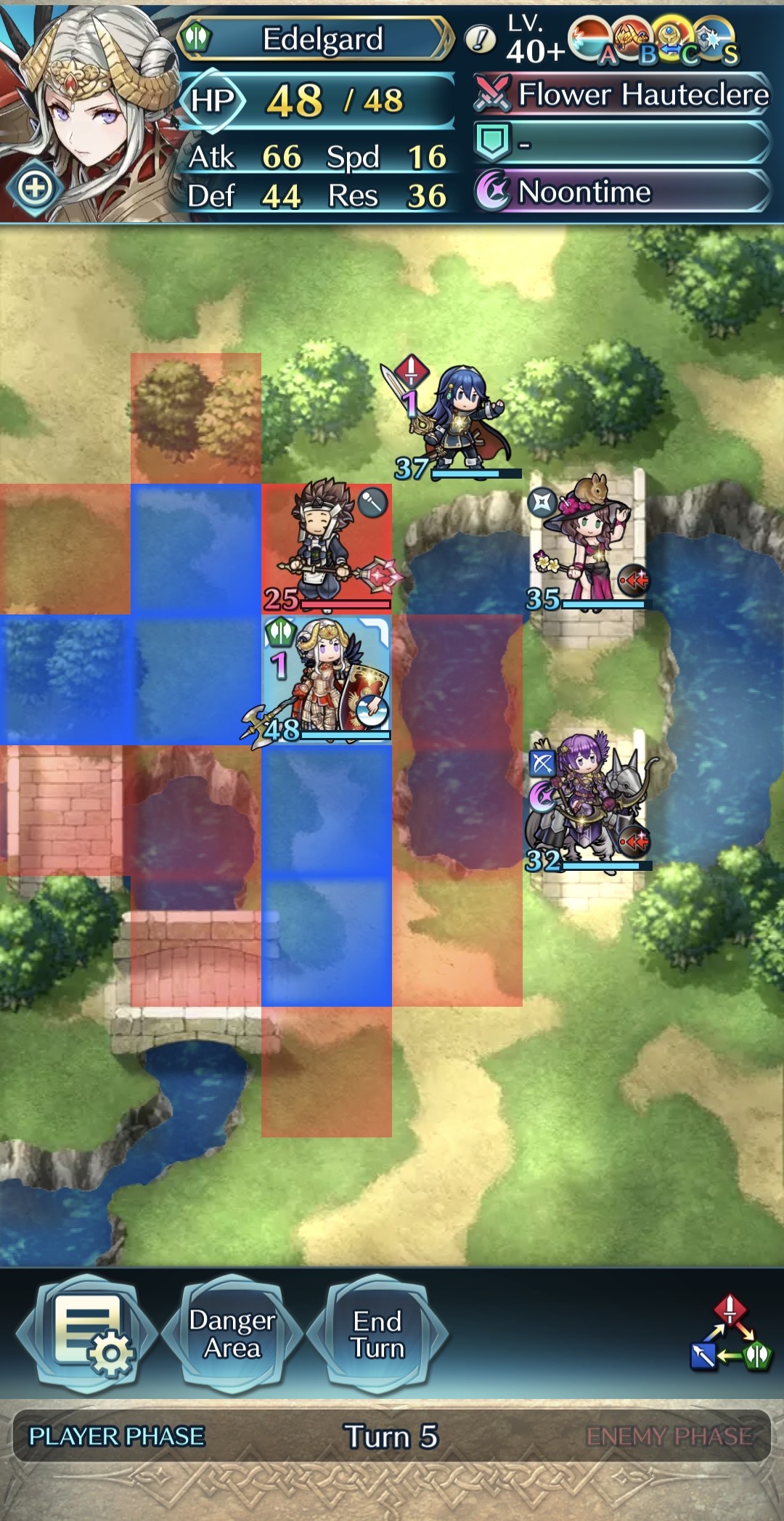

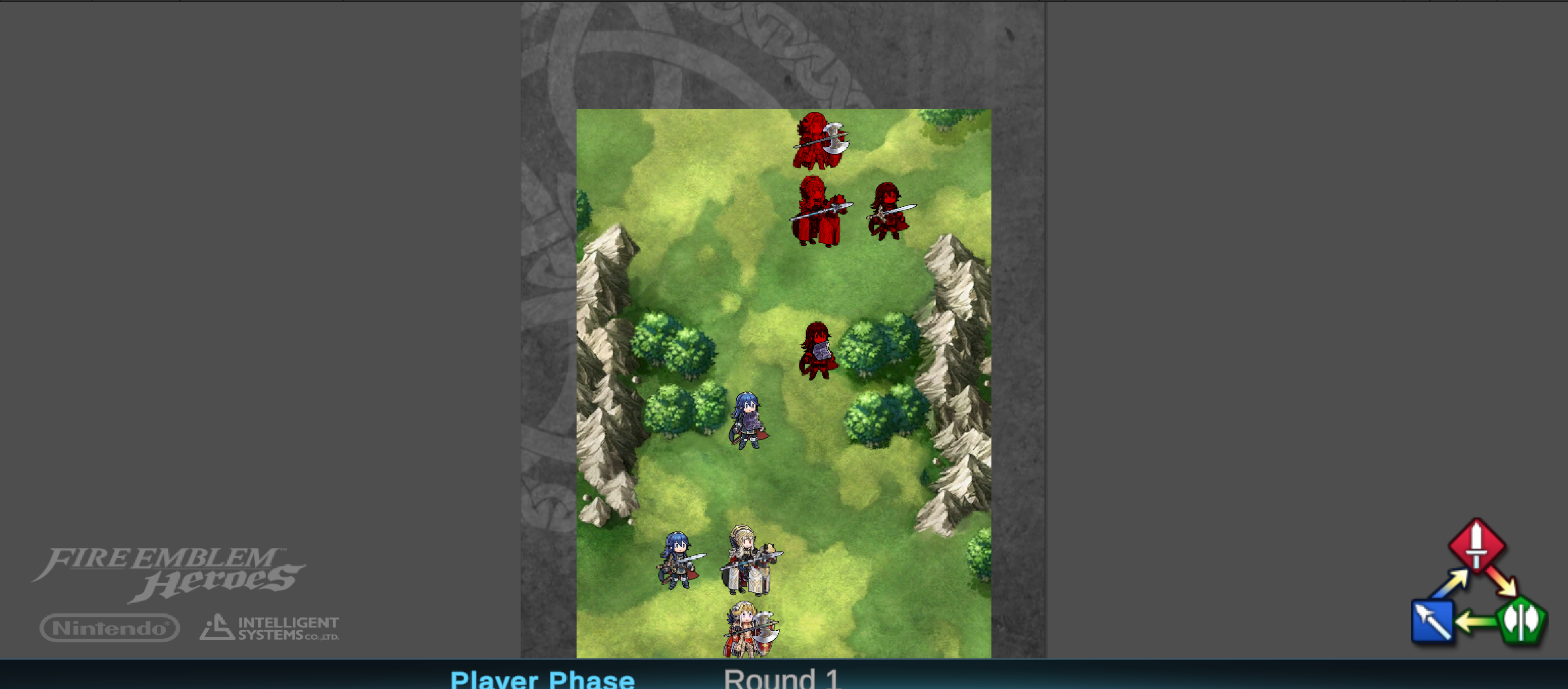

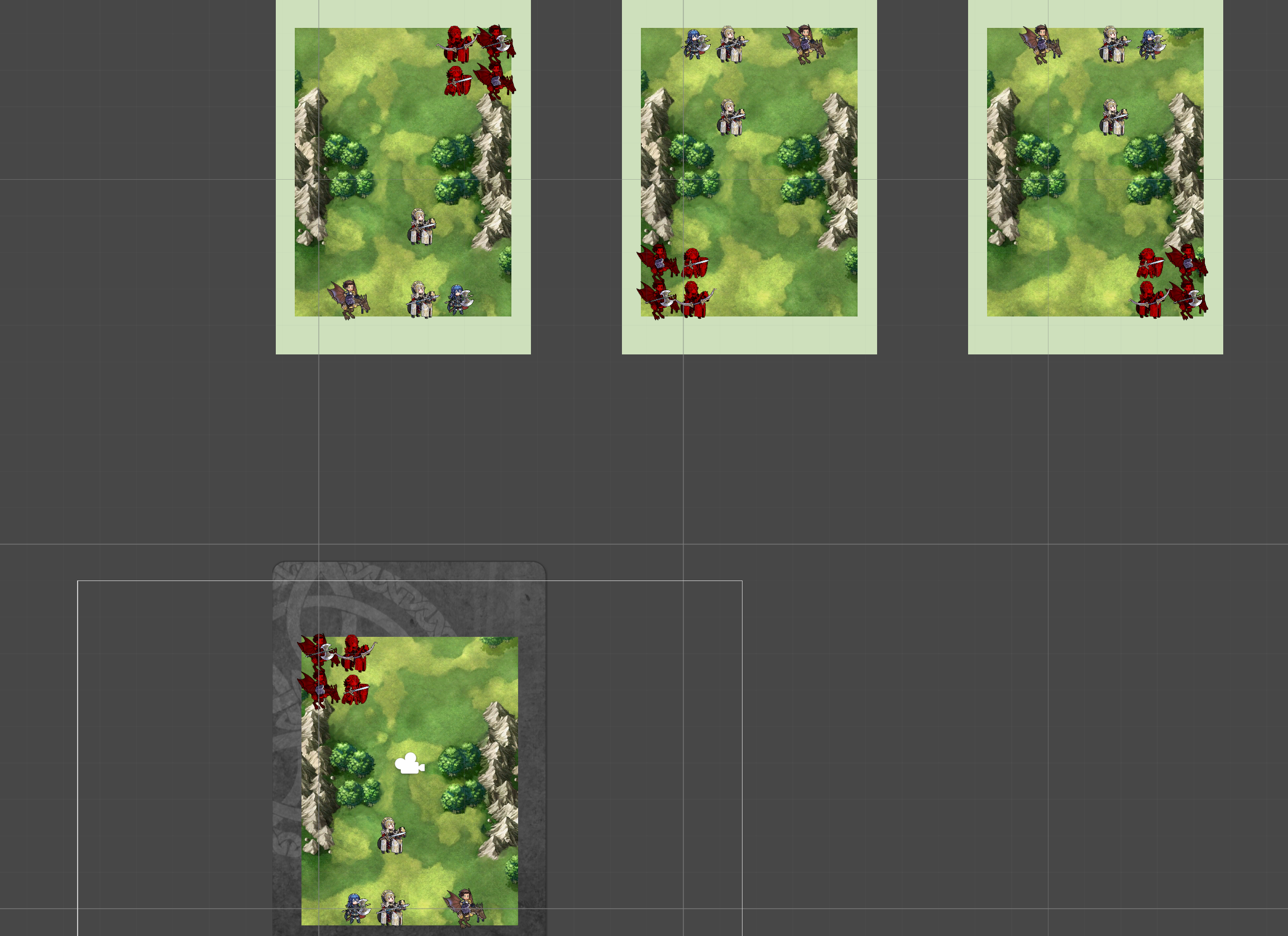

To study the potential of RL and IL in strategy video games, Fire Emblem Heroes is used as a layout of the typical tactical rules and designs in a regular strategy video game setting. Fire Emblem is a turn-based strategy role-playing game developed by Intelligent Systems and published by Nintendo. This research uses a simplified version of the 2017 mobile game adaption, Fire Emblem Heroes [21], maintaining the complex tactical thinking in a compact 6 × 8 grid-based map, such as the maps shown in Figure 1.

The game revolves around an alternating player and enemy phase. Starting with the player phase, all units are positioned on one tile on the map. Characteristics corresponding to the player’s team can be recognized by its blue color, while the enemy team is always represented by the red color. An example of the start interface can be seen in Figure 1a. In each phase, all surviving units in a team have one turn. One unit can be selected at a time to perform an action in their turn, which can be to move, wait, or attack. Attacks are only possible if a foe is within the attack range of a unit, and a target may counterattack if their range matches the attacker’s range. Figure 1b shows how the game presents tiles that are within attack or movement range. Tiles that are in attack range are highlighted in red, and tiles that are within movement range in blue. A unit can move to any tile highlighted in blue, as given in Figure 1c. If an enemy stands on a tile within attack range, the tile is highlighted in brighter red to indicate that the enemy can be selected to attack. When a target is selected, the combat information appears in the top of the screen, shown in Figure 1d.

The game ends when all units on one side are defeated. Each team contains four units, and the game starts at the player phase.

Each unit belongs to one of four types: infantry, cavalry, flying, and heavy armor units. The unit type determines their terrain accessibility, step size, and attack and defense power named as stats. Units also carry one of the five weapon types: sword, lance, axe, bow, or magic. Weapons determine attack range and can apply advantages and effectiveness. Melee weapons (sword, axe, lance) have a range of one tile, while bow and magic can attack from two tiles away.

The strategic thinking arises from the interaction of unit types, their weapons, and stats. The melee weapons are part of a weapon triangle, presented in Figure 2, similar to the “rock, paper, scissors” principle. Sword has an advantage against axe, axe against lance, and lance against sword. Boosting damage by 1.2x, or 0.8 the other way around.

Bows are highly effective against flying units, dealing 1.5× extra damage. Heavy armor units have a high attack and defense, but a low resistance, making them only vulnerable to magic. Magic units have a high resistance, and are valuable to defeat the heavy armor units, but they are vulnerable to melee attacks.

Lastly, the five core stats are important to keep in mind. HP determines the hit points the unit can take. Attack calculates the damage output by the unit. Defense is subtracted from the damage of an attacker carrying a melee weapon, whereas the resistance is subtracted from the damage dealt by a magic user. The speed enables a follow-up attack when the difference in speed between attacker and target differs at least 5 points.

Originally, the game includes more types than the aforementioned unit and weapon types. In addition, the strategies are widely influenced by special abilities, assists, and skills. To maintain simplicity, this implementation solely focuses on the interaction between the four unit types, and five weapon types.

A 2D game environment is created in Unity Engine. For the integration of ML tools from Python PyTorch library with Unity, the ML-Agent toolkit has been developed by Juliani et al., including the RL and IL algorithms programmed in Python [15]. The installation steps and setup instructions are followed according to ML-Agent version release 22 [14].

A constructed virtual environment within the same directory of the game environment allows interaction between the game environment and the ML tools in python.

The final game environment setup is posted on our GitHub page [3]. More detailed installation instructions and requirements are also mentioned.

The 2D grid-based map existing of 6x8 tiles, is recreated in a Unity 2D environment. The map is designed with complete symmetry across both axes. Each team starts on its own side of the map, ensuring that all tile types and movement distances are balanced and mirrored between the player and enemy units.

Units are defined by a combination of movement type, weapon type, and combat stats. These variables are set public and can be assigned in the Unity Inspector tab, in the Information component of the unit. The enemy types are completely randomized each game round. For both teams, the combat stats are randomized. Standard Mode and Mirror Mode are each created in a separate scene. In both scenes, all visual sprites and icons are collected from publicly available Fire Emblem Fandom community resources in the game assets page [10], and the unit sprites from the character misc information from the heroes list [27]. The resulting interface of the implemented game is shown in Figure 3, with the given interface after selecting a unit in Figure 3a and initiating a combat in Figure 3b.

The difference between the two scenes lies in the map layout, data collection, and enemy behavior.

The standard scene functions as a platform for collecting data, as well as training agents. The mirror scene is solely used for playing Mirror Mode, to evaluate the effect of the trained agents to imitate the player’s strategy. In this scene, the enemy team is a complete mirror of the player’s team, including unit types, weapons, and positions, as shown in Figure 4.

For the Standard Mode, a rulebased enemy AI is implemented based on the derived gameplay observations by expert players, documented by Game8 Inc. [9]. The algorithm follows a greedy approach, summarized in Algorithm 1, where enemies always attack if there is an opposing unit within their attack range. When multiple targets are in range, the enemy chooses the unit to which it can deal the most damage. If no opposing units are within attack range, the enemy holds its position. Furthermore, the order in which enemy units take their turns is determined by the following a set of priorities. Melee attackers are prioritized over ranged attackers, and are allowed to attack first. Result:

perform 𝑒 stays idle return end remove 𝑒 from 𝐸 end Among units with the same attack range, it prioritizes the units that can reach the player units the fastest. If all factors are equal, the leftmost unit in the map acts first.

Behavior. The enemy action decision process in the mirror scene is purely controlled by the learned algorithm, provided by a trained model. In the enemy’s turn, the agent requests a decision from the trained model. This returns the discrete actions array based on the collected observation. The enemy agent uses the array to set the actions. A summary of this enemy behavior is provided by Pseudocode 2.

Script. The player’s actions are handled through the mouse input system. Selecting units, tiles, and targets are all handled through intuitive clicking interaction, based on the original game. Each player unit contained its distinct recording component and agent behavior script, available through the ML-Agents package [26]. Once an action is put through, the script processes the observed state and taken action by the player, and stores the corresponding state-action pair in demonstration files. The approach for the research begins with the underlying programming for training the Mirror Mode AI and collecting data. This section describes the dataset that is used for training the models, including the methods for collecting the data. Followed by our used training methods that incorporates the RL algorithm PPO, and IL approaches BC and GAIL. RL makes use of a reward system whereas the collected dataset is only utilized by the IL algorithms.

Player demonstrations were collected from real-time games played in the standard scene. The scene includes three augmented environments, that were created by flipping the original map configuration along the x-axis, y-axis, and both axes, as presented in Figure 5a. This allowed a single set of demonstrations to generate four unique moves at one time step. The collected demonstration data is stored in .𝑦𝑎𝑚𝑙 files saved in the game scene directory.

Training agent models for the Mirror Mode enemies occurred in the standard scene as well. Alongside the four augmented environments, six more environments were created to accelerate training. In total, all ten environments functioned as direct copies from the original environment and operate in parallel only when training was enabled (Figure 5b). During training, the agent scripts in Unity were activated, that use the directed information available in a .yaml format. This file includes the demonstration path from the collected player data, and the desired parameters and algorithm names for the model. The unit behaviors script handled the interaction input explained in 3.3.3, as well as the functions enabling RL. It first collects observations from the current state of the map based on the agent’s local position. Then, invalid actions are masked from the model, preventing these actions from getting selected. For this study, the function filters out the tiles that are not reachable for an agent at a current state, and the targets that are not available to attack. Lastly, it receives the selected action given through the mouse interaction provided by the user. Once the game scene is started in Unity, the training progression begins.

The used RL algorithm, PPO, requires a defined action space, state space, and reward system. This section presents how the three were implemented for this study.

The actions space is given by an array of three discrete action variables: action type, selected tile, targeted unit.

An action type holds an index that corresponds to the action chosen by the player, which can be to wait (0), to move (1), or to attack (2).

The selected tile corresponds to the index of a tile within the map size 6x8, resulting in an array of size 48. This tile index then maps to the tile that the unit needs to move to. For the waiting action, this equals the index of the tile that the unit is currently already on. For the attack action, the tile that the unit stands on to launch it attack from is used.

Lastly, the targeted unit decides the target that will be attacked during an initiated combat. If no combat is initiated, the value is of no use. In case an attack is performed, the index of the target unit is used.

Space. The state space of the game is constructed by an array with size 136. This array stores all relevant information concerning the unit’s and enemy’s stats, weapon, and unit types, and the manhattan tile distance between the unit and an opponent are stored in the array. For more compatible computation all values are normalized to a value between 0-1.

System. Finding a proper reward system for the game environment acquired testing and time. A reward range of [-1,1] was followed, recommended by the package creators [24]. Killing enemies and winning a round was rewarded by a positive reward of one. A negative reward of one was given to a unit after it had died, or when the game round was lost. Any other rewards for choosing valid actions received a reward of +0.3. To stimulate training, a maximum set of actions per game was implemented and set to a value of 20. After reaching the maximum value, the game ends in a tie resulting in a punishment of -1. This improved the learning curve, making sure the agents did not avoid attacking targets.

Finding these settings, the agents were fully ready to learn from the environment and demonstrations, with no further complications that led to unjustified behavior. The rest of the research continued with these agent settings.

For the IL behavior of the agent, we employ BC and GAIL algorithms developed by Juliani et al. [15]. IL is used in conjunction with RL, to enable better copying behavior and reduce the time it takes for an agent to acquire a proper behavior. The collected dataset provides the expert demonstrations from which the IL algorithms lean a policy. GAIL rewards the agent using an adversarial approach that evaluates how closely its actions match those in the demonstrations. The GAIL loss serves as a penalty for the discriminator when it misclassifies an agent action as a demonstration action or vice versa. We aim to keep this loss at a moderate level and use it as an indicator of how well the agent imitates the demonstrations. BC is used to pre-train the agents before applying RL and GAIL. It updates the agent’s policy to exactly replicate the actions the demonstration set, and is therefore most effective when a sufficiently large set of demonstrations is available. Consequently, BC is used in combination with GAIL and RL to leverage imitation behavior.

The degree to which the agent relies on demonstration data can be set manually through the strength parameter. For both BC and GAIL, various values are tested in the firs half of experiments, to provide an optimal configuration.

A set of optimal hyperparameters and algorithm combinations to train the Mirror Mode model, were found through the first two conducted experiments. These two experiments form the first half of the experimental setup for this research paper, to find an answer to the question whether RL and IL can be used to imitate player’s strategy in video games. This is followed by the third experiment, involving user studies to evaluate the effectiveness of the agent models on game experience and its imitation capabilities.

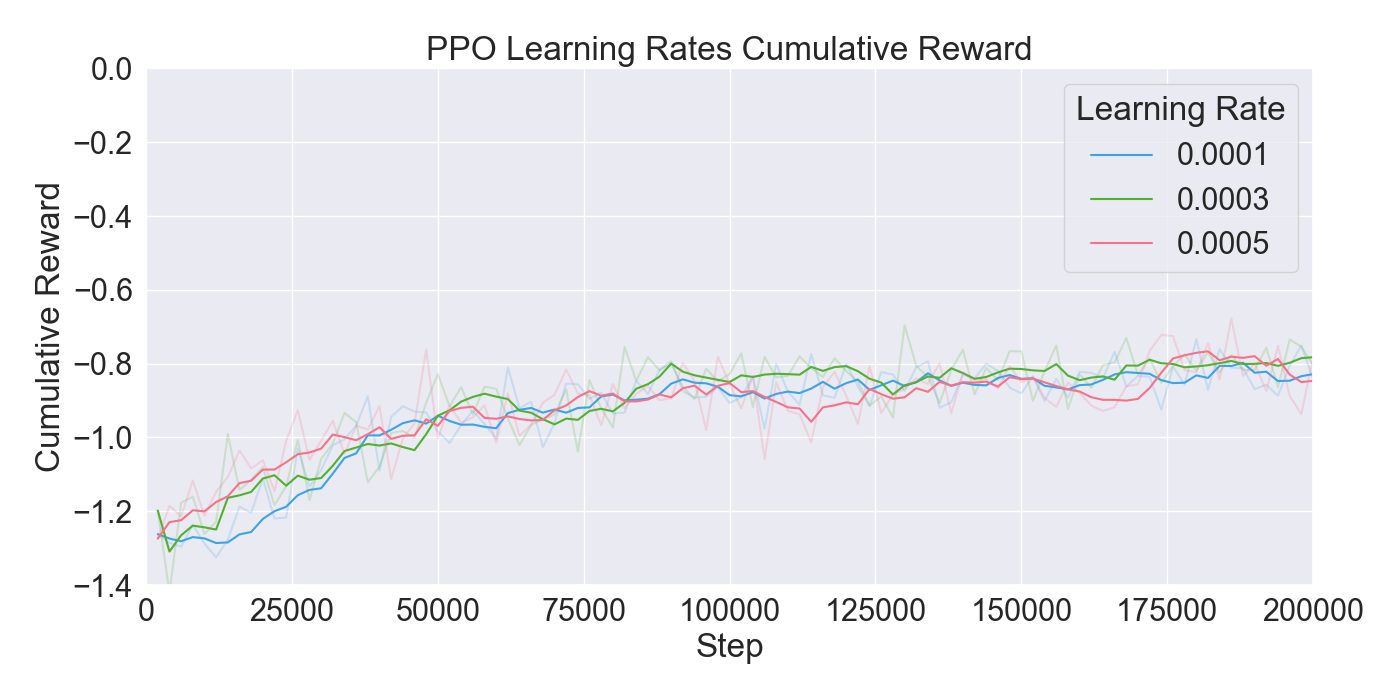

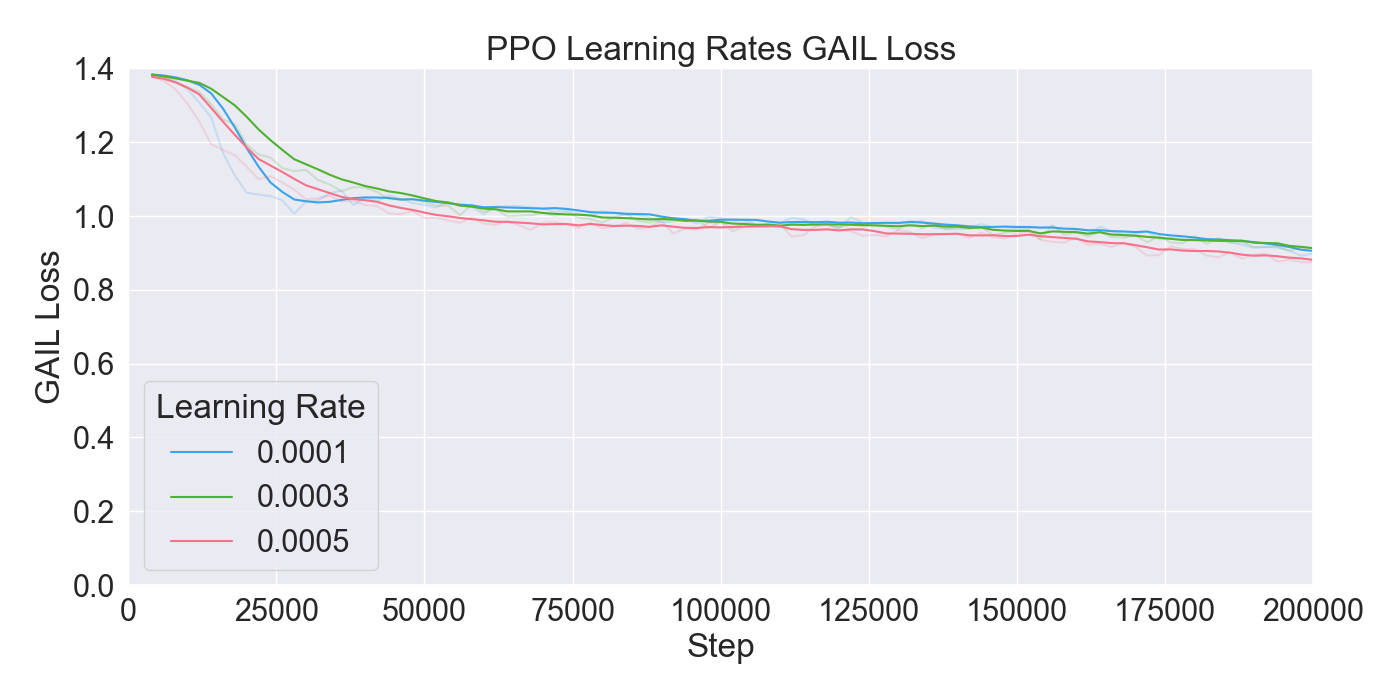

The aim of the first experiment was to optimize the performance and imitation quality of the agents, by adjusting one parameter at the time, while keeping the others constant. The value range of each parameter recommended by the ML-Agent developers were taken into consideration [25].

Optimizing the models for this study purely focused on the following hyperparameters:

• BC strength;

• PPO learning rate 𝛼;

• GAIL learning rate 𝛼;

• extrinsic strength;

• curiosity strength.

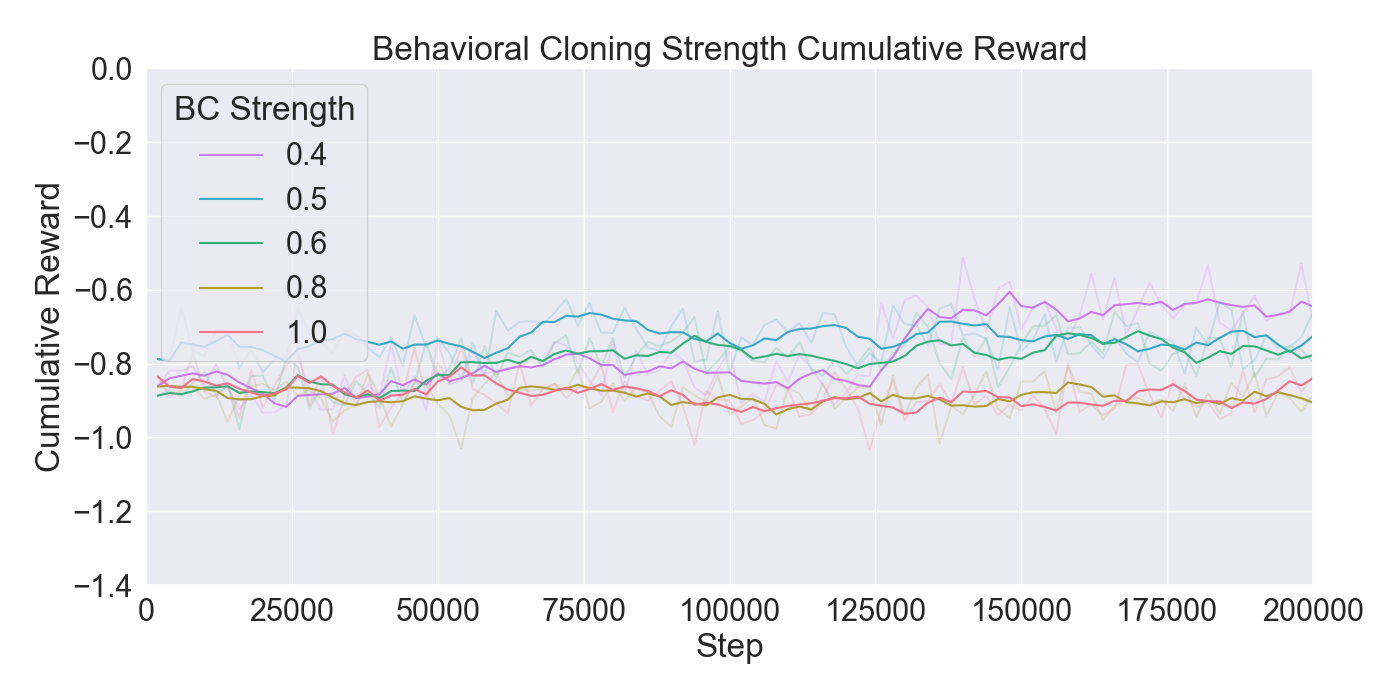

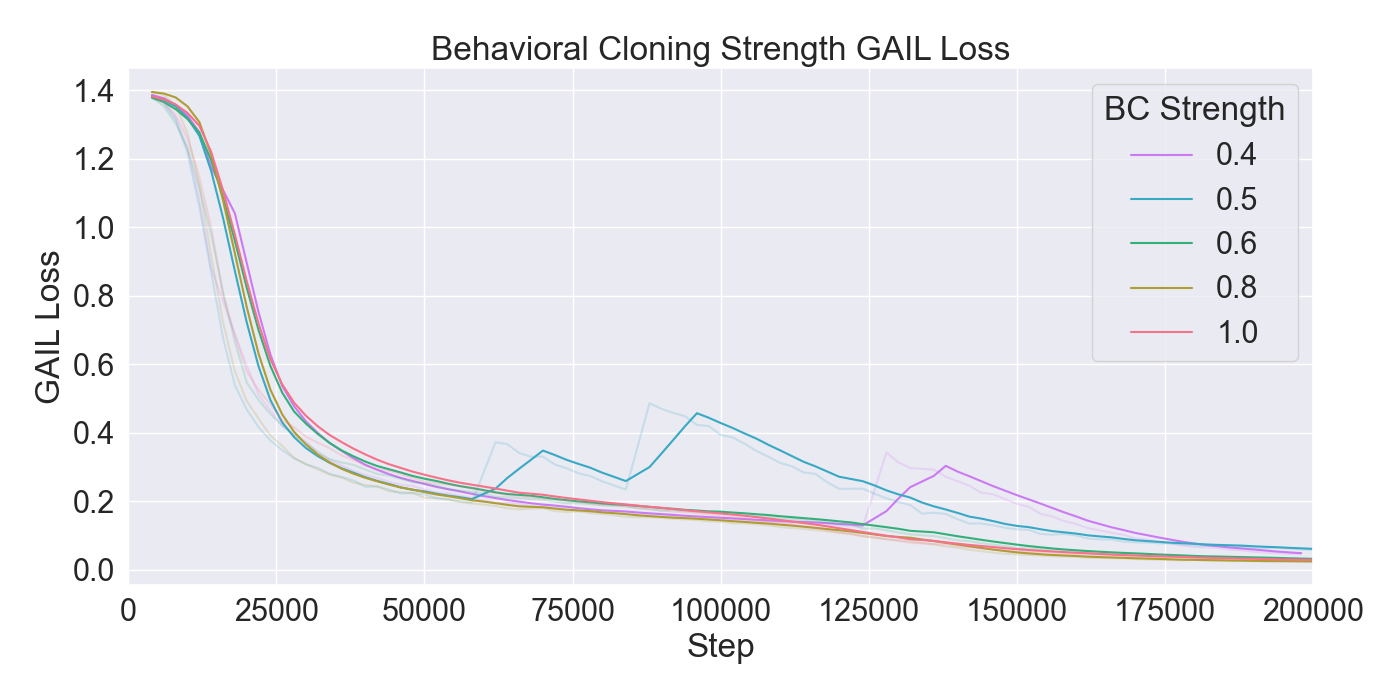

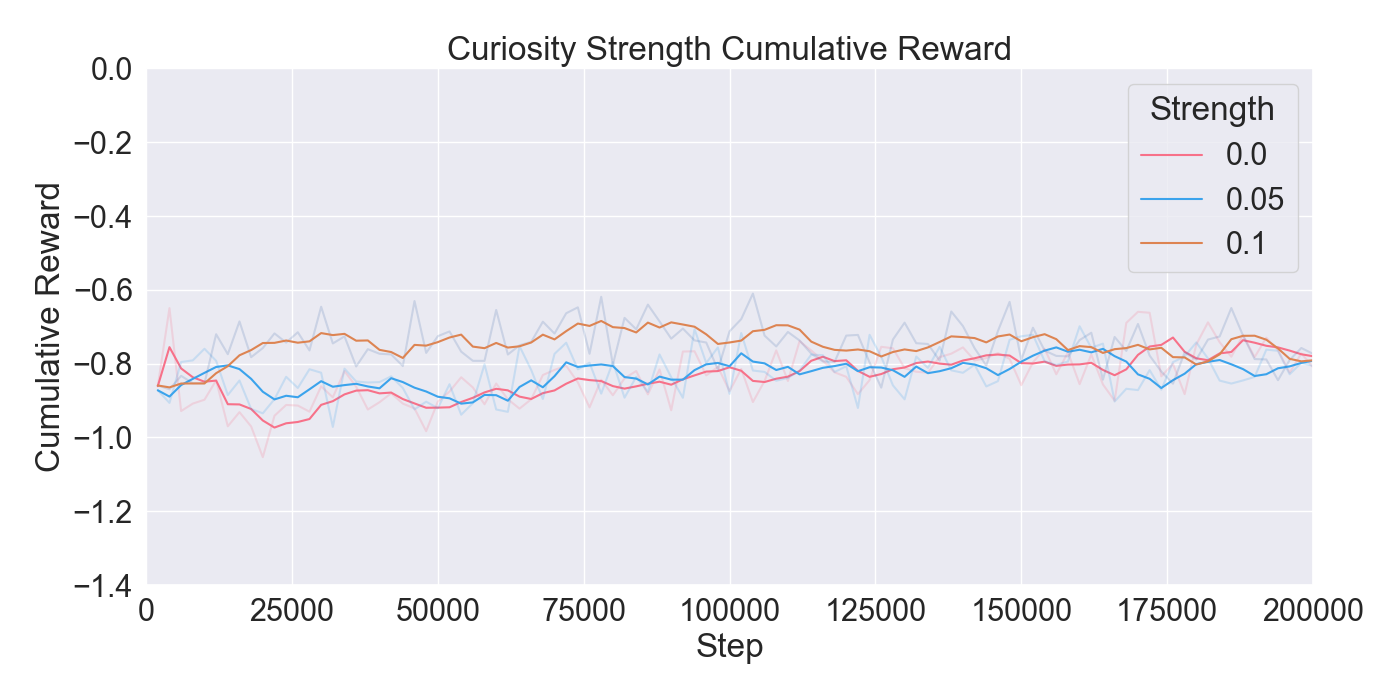

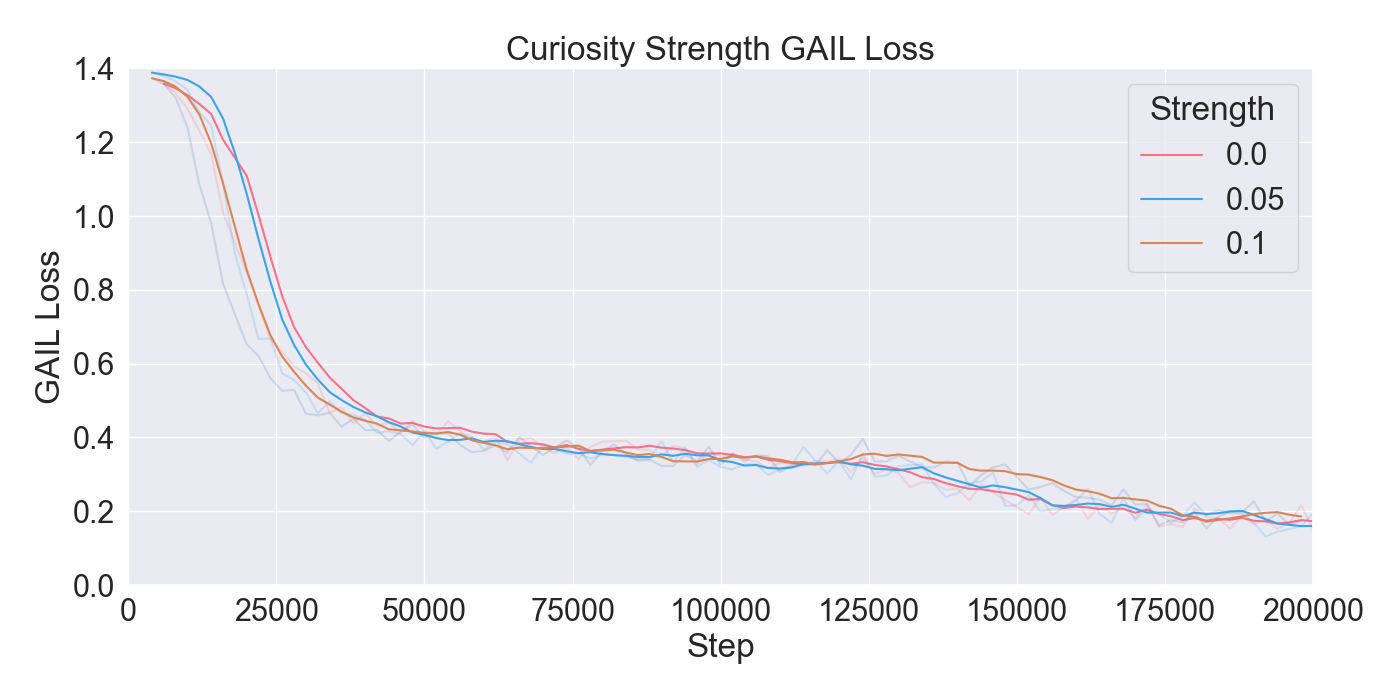

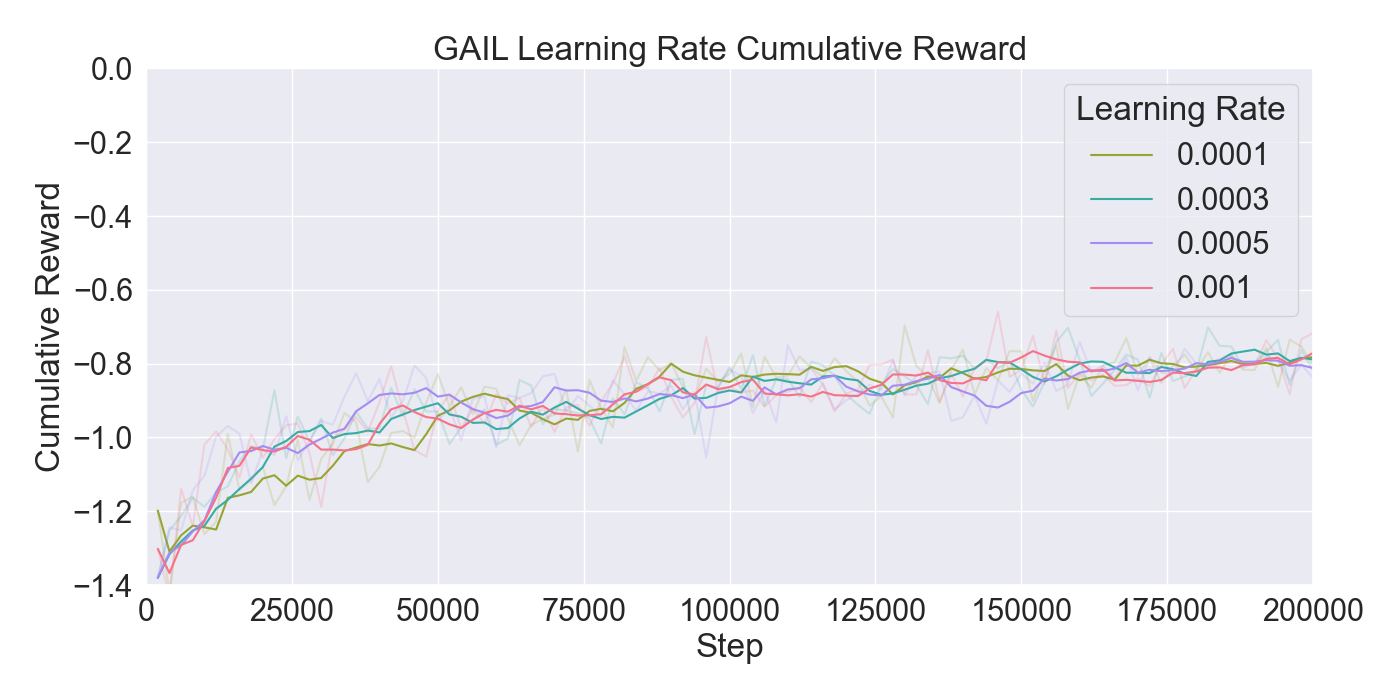

For each tested hyperparameter, the used values for testing are summarized in Table 1. The rows show the parameters that are tuned, and the columns show the values set to the parameters while tuning. The tested values for each parameter are presented in bold font. Remaining parameters not mentioned in the list are set to their default values. Each model was trained for 200,000 steps starting at step 0 with no prior knowledge yet. Models were evaluated based on the total cumulative reward and GAIL loss. Cumulative reward served as a measurement for learning capability of the agents, and GAIL loss for the ability of imitating a player’s strategy.

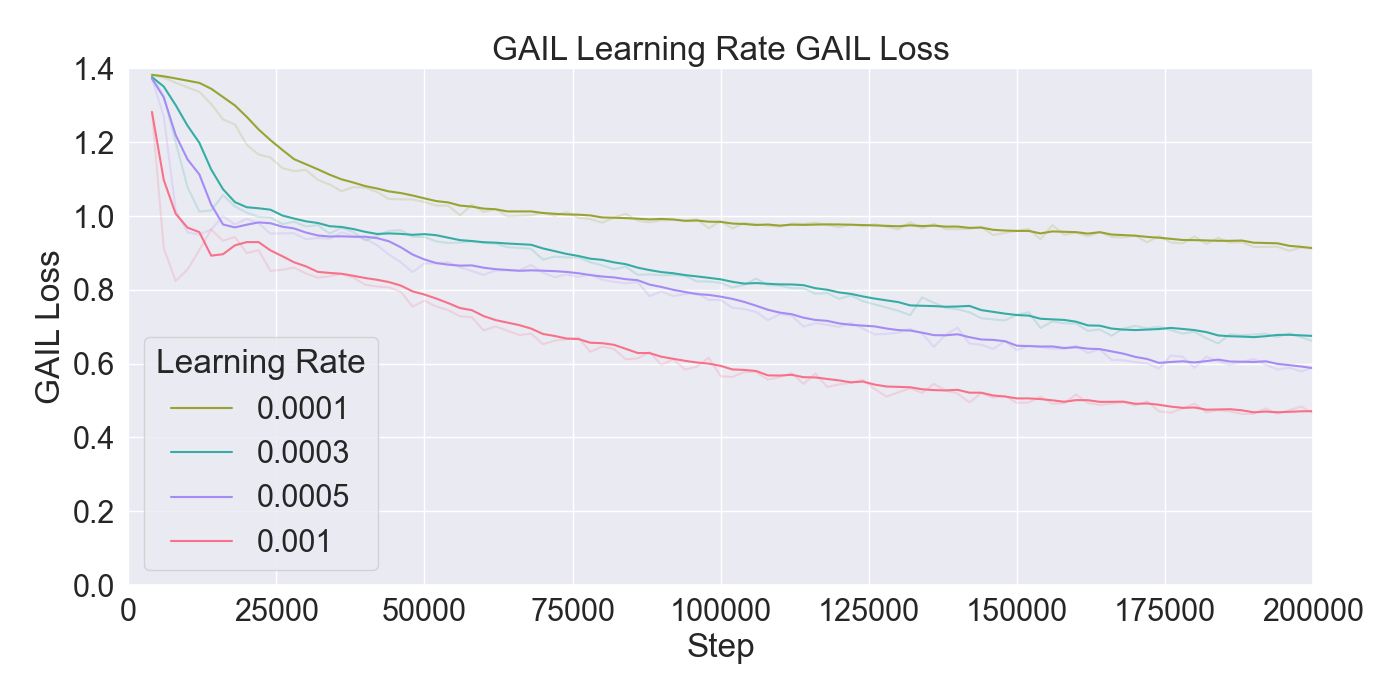

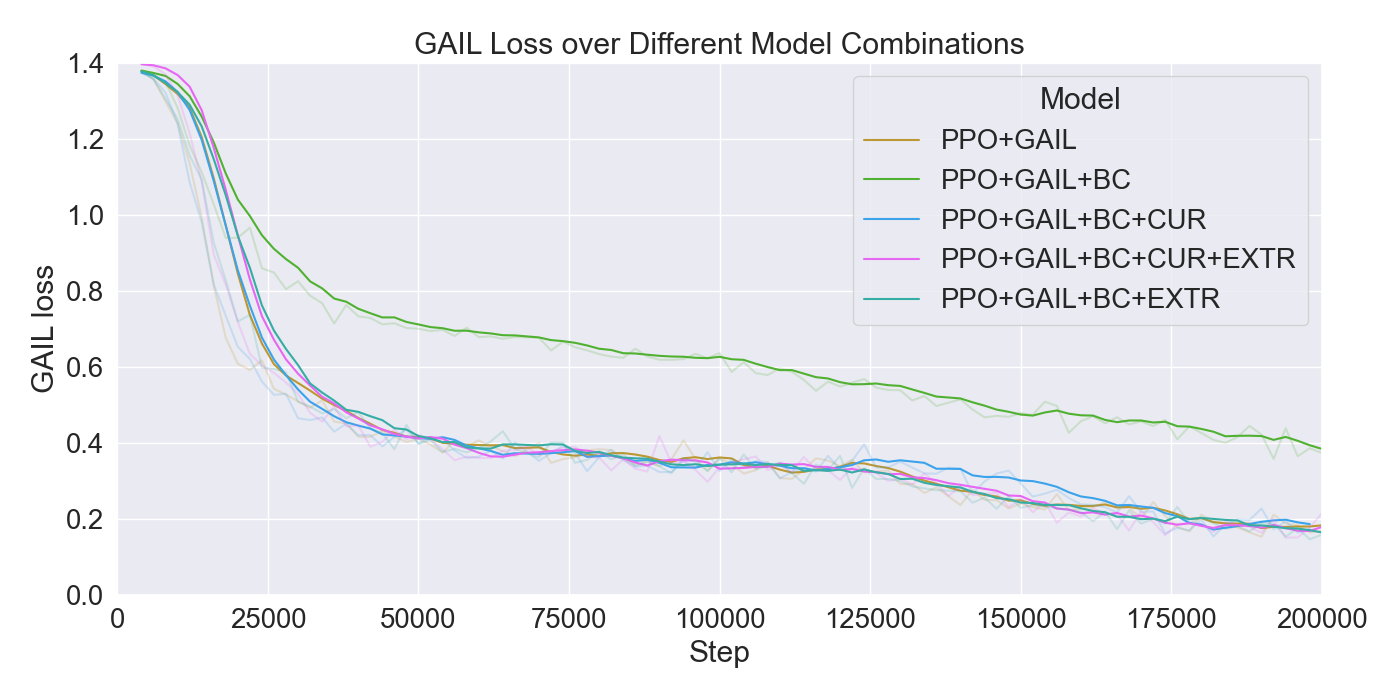

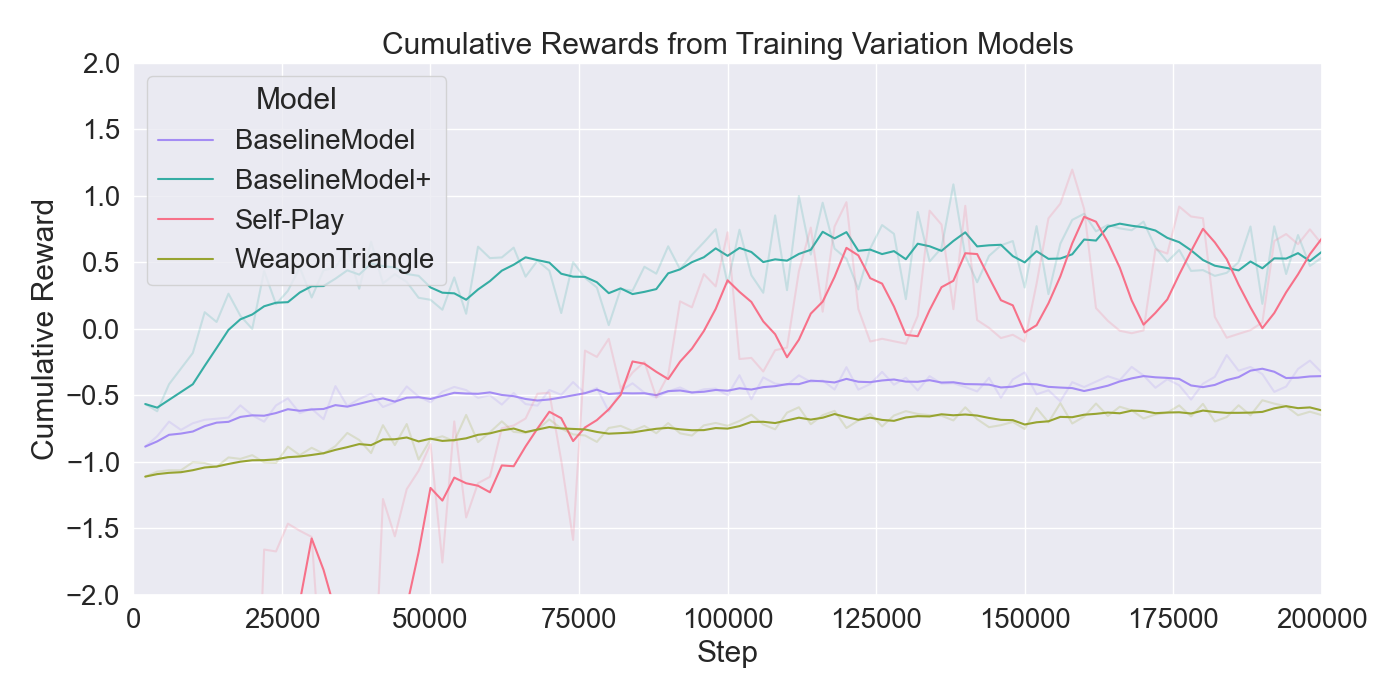

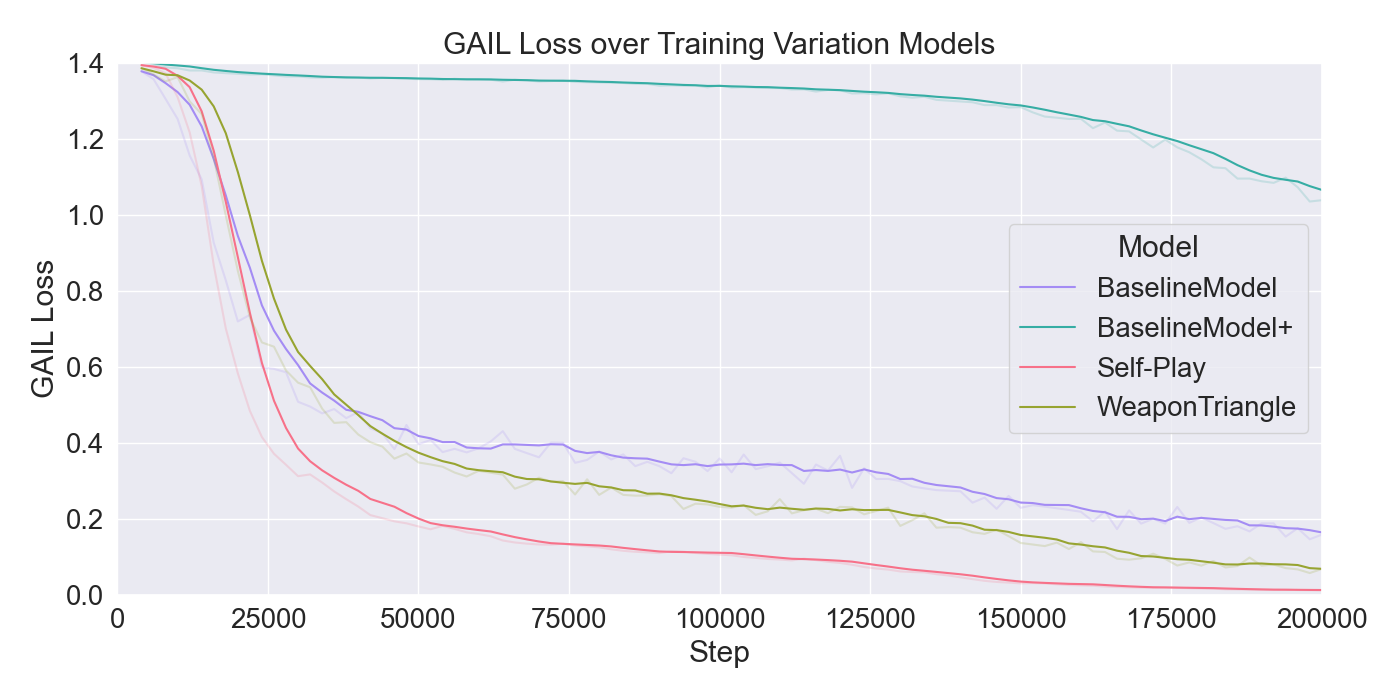

After identifying the optimal performing model from Experiment 5.1, further experiments were conducted to determine the optimal configuration for the enemy AI in Mirror Mode. Several combinations of RL and IL techniques were tested.

The following model variants were evaluated:

• PPO + GAIL + BC + Curiosity + Extrinsic Rewards;

• PPO + GAIL + BC + Extrinsic Rewards;

• PPO + GAIL + BC + Extrinsic Rewards + self-play Similar to the first experiment, the cumulative reward and GAIL loss served as performance evaluation metrics, taken over 200,000 steps.

During this phase, a fixed set of hyperparameters was used for consistency across models, as listed in Table 2.

To increase imitation quality, a final configuration is tested with increased values for the GAIL hidden unit and PPO batch size. Based

The results of the two conducted model configuration experiments are discussed in this subsection.

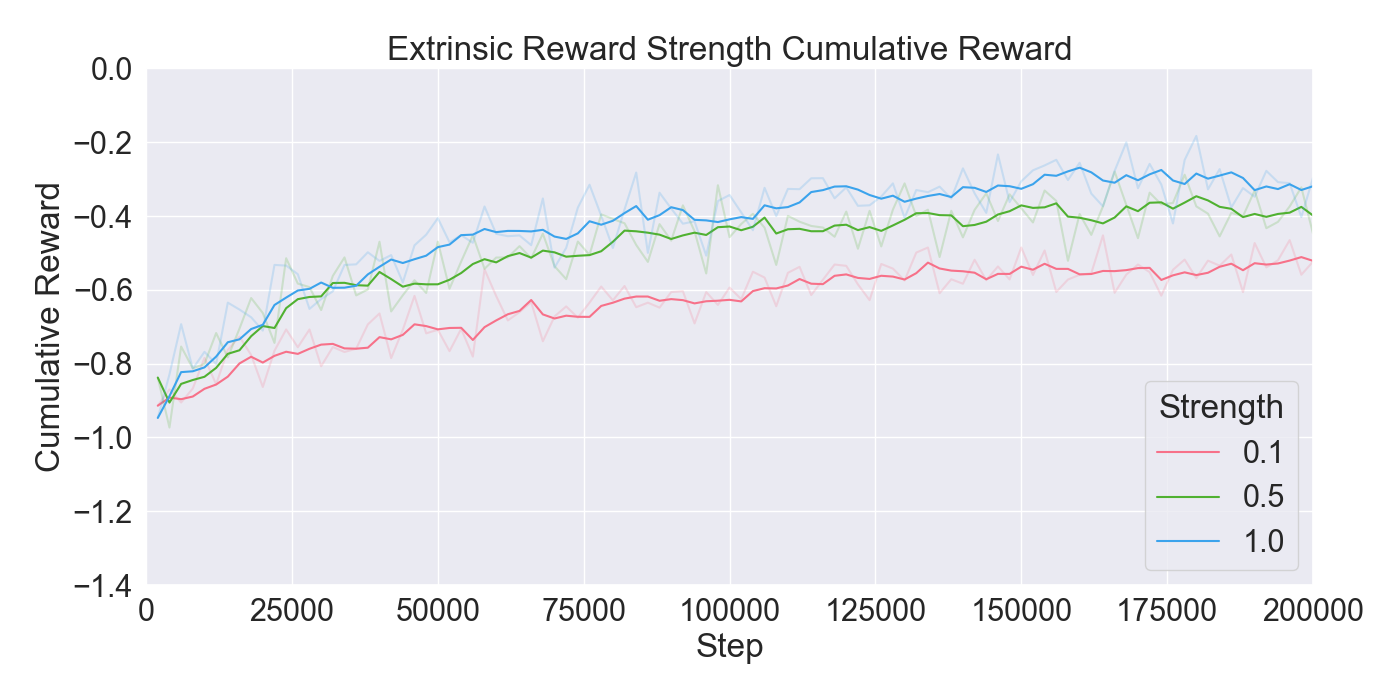

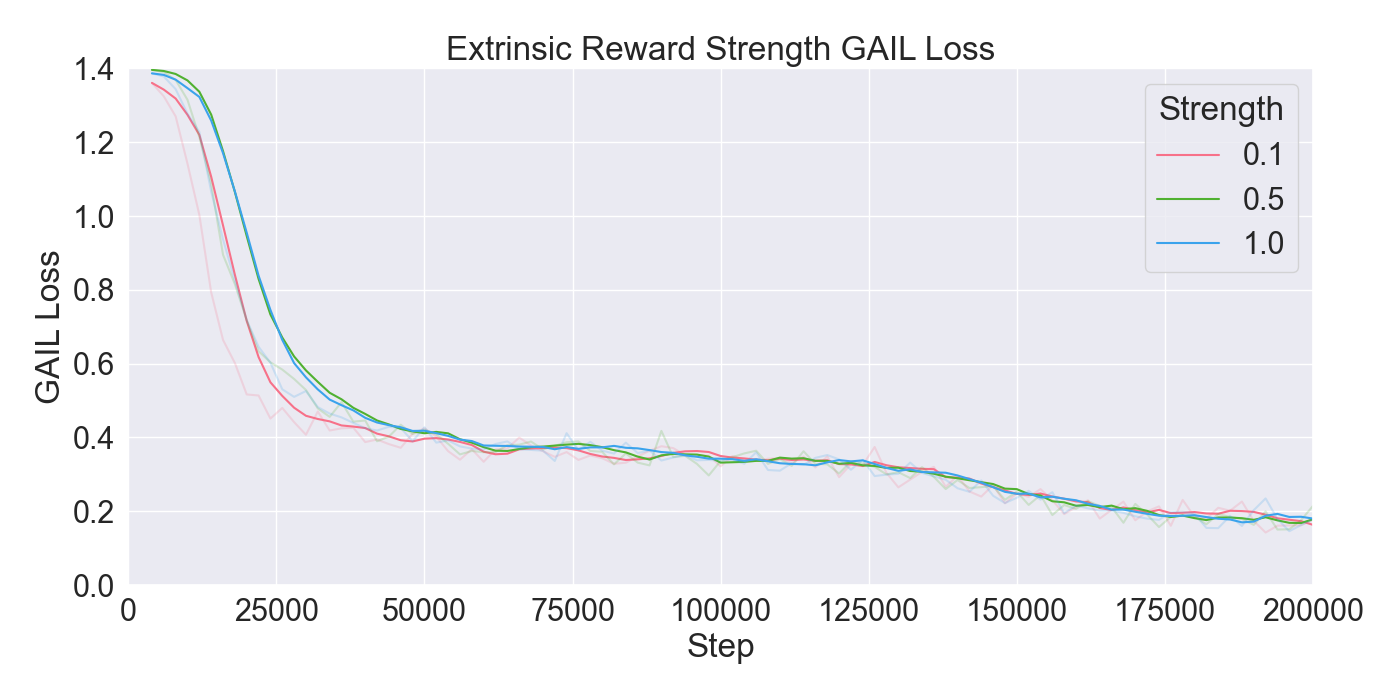

Finetuning. The finetuning experiment lead to the results presented in Figure 6. The results indicate a gradual learning progression for both PPO and GAIL, whereas BC shows a flattened learning curve. PPO and GAIL converge toward a relatively high cumulative reward of approximately -0.8, with GAIL demonstrating a faster convergence. The absence of environment interaction in BC may explain the flat learning trend. Despite the limited learning progression, the BC model achieves a rather good cumulative reward compared to the PPO and GAIL finetuning models. Specifically, a BC strength of 0.4 starts below -0.8, and improves to a higher reward of nearly -0.6, ultimately outperforming the PPO and GAIL. PPO results in a much higher GAIL discriminator loss, of roughly 0.9, compared to other models, suggesting a poor performance of the GAIL discriminator. Introducing a higher value for GAIL 𝛼 causes the discriminator loss to drop, showing a much wider range in discriminator loss over the training steps for GAIL compared to other finetuning models. Interestingly, introducing an extrinsic reward accelerates the learning curve drastically, with the cumulative reward converging to nearly -0.2 when the strength parameter is set to 1.0. However, extrinsic reward reduces the GAIL discriminator loss, dropping too close to zero, which may indicate poor imitation quality. In contrast, incorporating a curiosity-based reward appears to have little to no impact on either the cumulative reward or GAIL loss. The results closely resemble those from BC finetuning models without curiosity, suggesting limited effectiveness of curiosity in this setup.

Considering these results, it was chosen to continue with a PPO learning rate set to 𝛼 = 0.0003, and GAIL learning rate to 𝛼 = 0.0001. Moreover, BC was retained to enhance the imitation learning, with its strength set to 0.4. Curiosity was excluded due to its minimal impact, while extrinsic reward was set to a moderate value of 0.5 to maintain the balance between imitation and exploration.

The results of the model configuration tests are presented in Figure 7. It is observable that the PPO model inclines most rapidly, reaching the highest cumulative reward. On the other hand, the model shows no imitation behavior, as it does not use imitation learning. 𝑃𝑃𝑂 + 𝐺𝐴𝐼𝐿 gradually inclines to a similar performance, but scores a rather low GAIL loss. The GAIL loss for most models decrease rapidly toward a value of 0.2, except 𝑃𝑃𝑂 + 𝐺𝐴𝐼𝐿 + 𝐵𝐶 which declines more gradually. For a longer training period, it is expected to lose imitation quality as the curves have not reached the minimum. In this case, the results indicate best imitation practice without extrinsic rewards or curiosity, but a better performance when extrinsic rewards are added to a model using BC. To focus on the imitation abilities, it was chosen to continue with BC, but including extrinsic rewards to allow better performance. To increase the model performance and steadier imitation, the last configuration tests set GAIL hidden units used to 128, and PPO batch size to 256. Additionally, Self-Play is applied to the setup with the found optimal hyperparameters, and another model is trained where the attacks are limited to melee weapons, reducing the action space. The corresponding results are presented in Figure 8.

BaselineModel+ converges quickly to a cumulative reward of nearly 0.6 despite a less stable curve. Overall, the BaselineModel+ demonstrates strong potential agent behavior. The GAIL loss shows a slower decrease over time, making it more suitable for training the Mirror Mode models over a larger period of steps. These results indicate that the modified batch size and hidden units result in a faster improvement in cumulative reward but a slower convergence of the GAIL loss. The Self-Play model shows a promising growth in cumulative reward, going from a large negative value to positive reward. However, unlike the BaselineModel+, Self-Play quickly decreases in GAIL loss, reaching a value too close to zero, making it not a reliable model for imitation purposes. Training a model purely on weapon triangle weapons shows no better results than the baseline model with the optimal parameters, indicating that fewer weapon types does not improve agent performance.

Although the model without IL implementation gives the best performance in regards of total reward, there is little guarantee that the agent imitates the player’s demonstrations. Therefore, the study chooses to continue with a model combining the RL techniques from PPO and extrinsic rewards for a steady performance, together with the two IL algorithms BC and GAIL for imitation assurance. The BaselineModel+ is the final configuration, used for training the agents that mimic players in the user experiments.

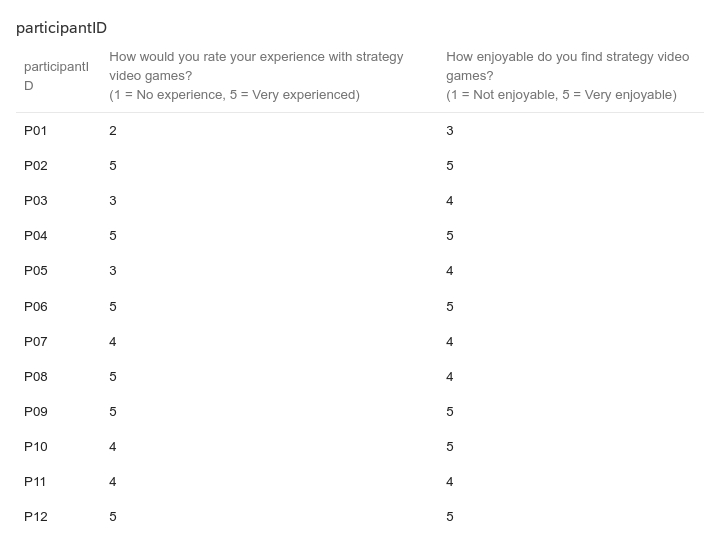

Inspired by Pagulayan et al. [19], both qualitative and quantitative data were collected in a small-scale set up to evaluate the effect of the Mirror Mode algorithm on gaming experience and satisfaction. Only experienced strategy video game players were asked to participate. Players were asked beforehand to rate their skills and familiarity with turn-based strategy video games.

The study included 12 participants, randomly assigned to a control group (𝑛 = 6) or an experimental group (𝑛 = 6). The experimental group played against agents that were trained on their personal recorded demonstrations, whereas the control group played against the strategy of one player from the experimental group. Each participant took part in two test sessions conducted on-site. In order for the AI model to learn from a participant’s gameplay, the two game modes for the test group were tested on separate days.

For the first session, the participant played the Standard Mode for five full rounds. Their game state and action pairs were recorded through the player script described in 3.3.3. Additional game behavior metrics were tracked in the agent script, including attack advantages and disadvantages, total movements, total attacks applied, total effective attacks, and total wins. After the playing session, a survey was administered to assess the participant’s experience and satisfaction. The survey provided a satisfaction score, through 9 rating questions on a scale from 1-5, indicating a player’s satisfaction of the game.

During the second session, the participant played the Mirror Mode, allowing the enemy AI to utilize the learned model from the Standard Mode. Similar playing metrics were collected, this time from the enemy agent using the Mirror Model. The session was again followed by the same survey for the satisfaction score, with additional questions that focus on comparing the Standard Mode and the Mirror Mode.

Each test was concluded with a few additional questions about the player’s experience, recorded in the survey. This casual interview allowed participants to provide qualitative feedback about their overall experience across both modes. Interview questions recorded the game experience, interests, and skills of the participants. Moreover, they were asked to describe the enemy behavior and any potential differences that they noticed between the two game modes.

After the conducted user studies, a total of six distinct agent models had been trained (over a total of 1M steps): one for each experimental participant. Over all the second sessions, each model was tested twice. One time against the participant whose demonstrations were used for training the model, and one time against one control participant. This allows fair comparison of the recorded performance metrics, between the enemy agent and the participants competing against that agent.

The results from the third experiment were collected through questionnaires, filled in by each participant. Only players familiar to strategy video games took part in this research. They were asked to rate their skills and familiarity beforehand, with the results presented in the Appendix 12. Independent t-test showed no significant differences between the experimental and control group in familiarity 𝑡 (10) = 0.00, 𝑝 = 1.00, or in skill level 𝑡 (10) = 0.42, 𝑝 = 0.69. Hence, the groups were considered fairly divided with respect to prior experience and knowledge.

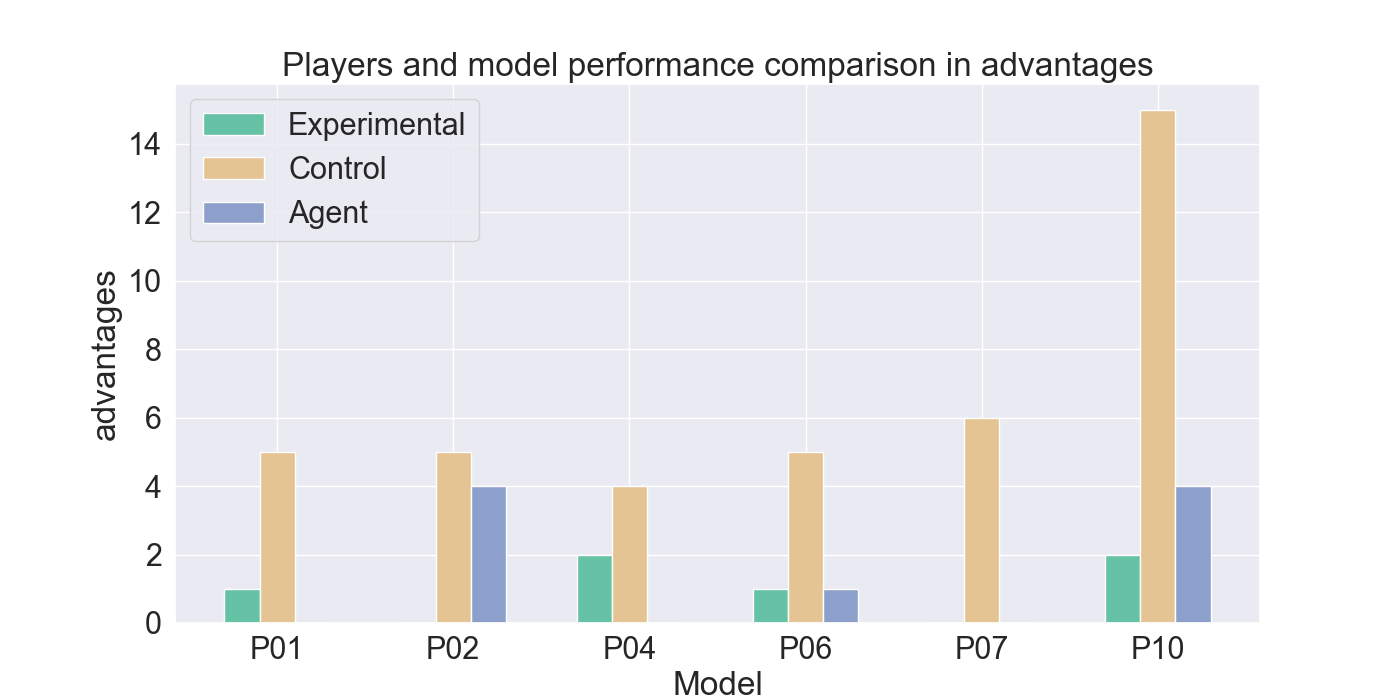

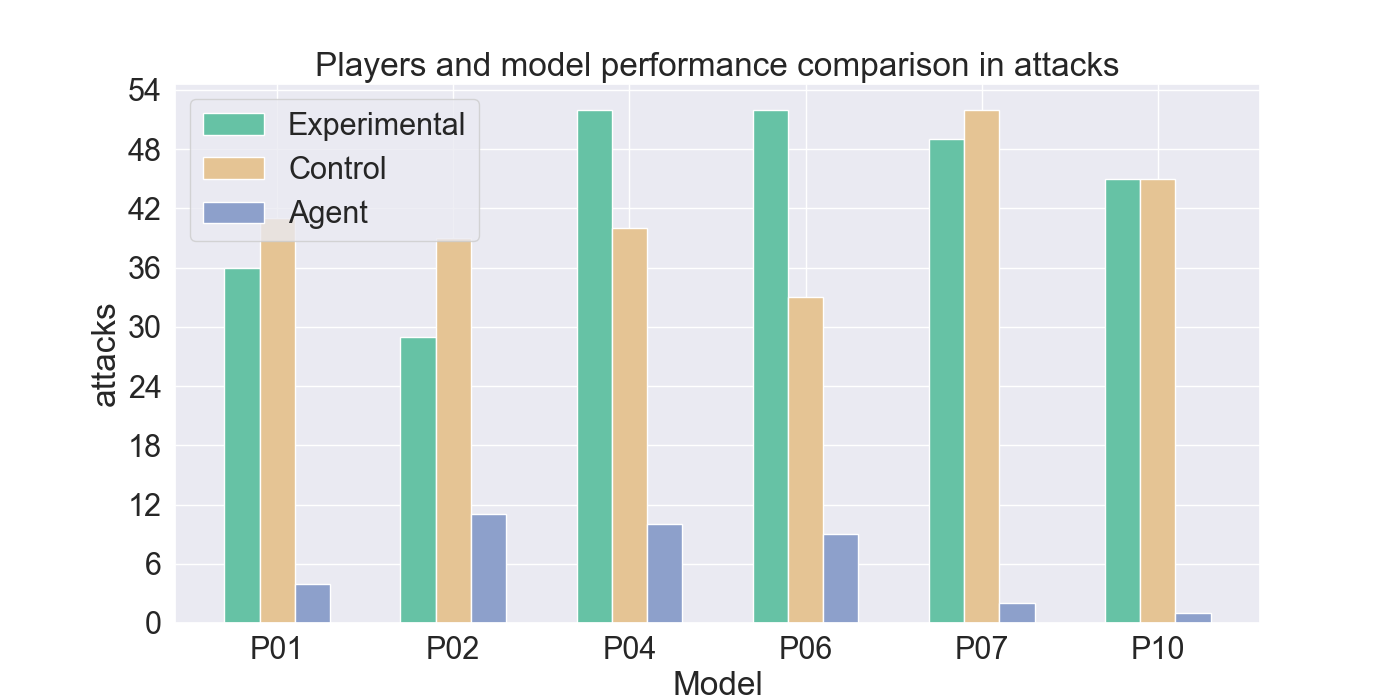

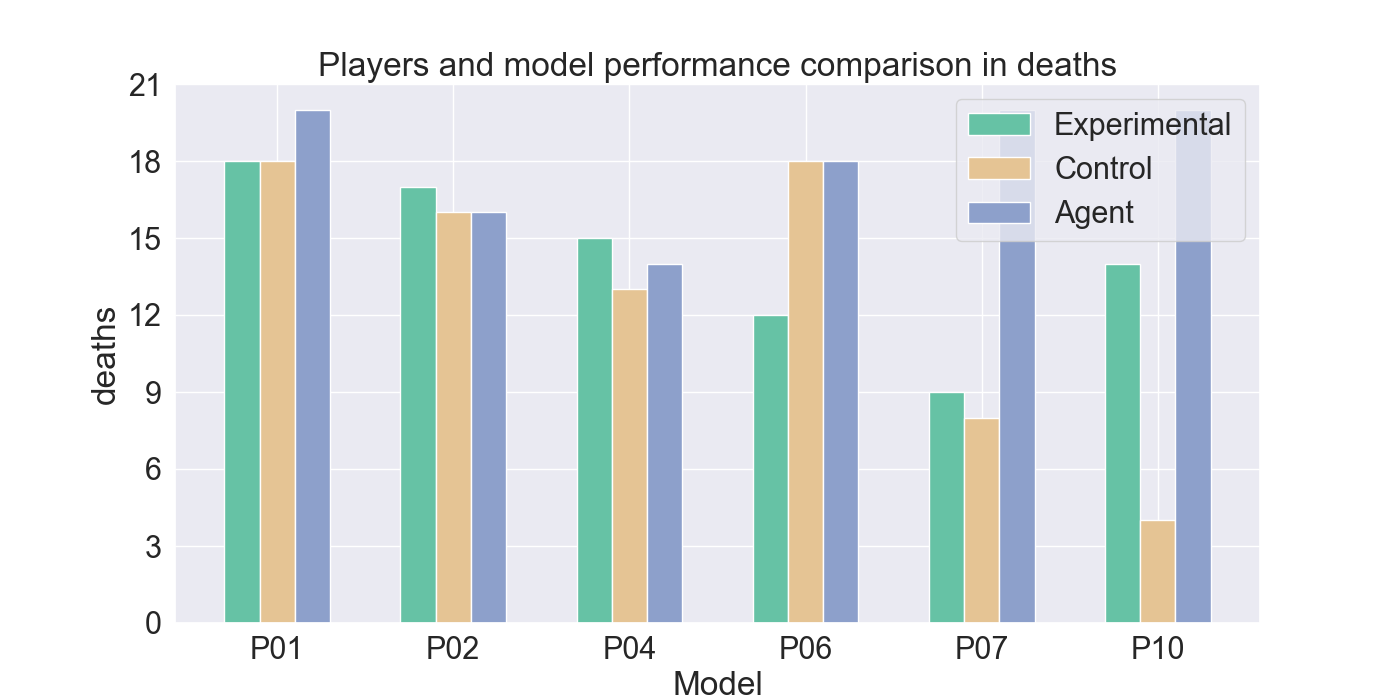

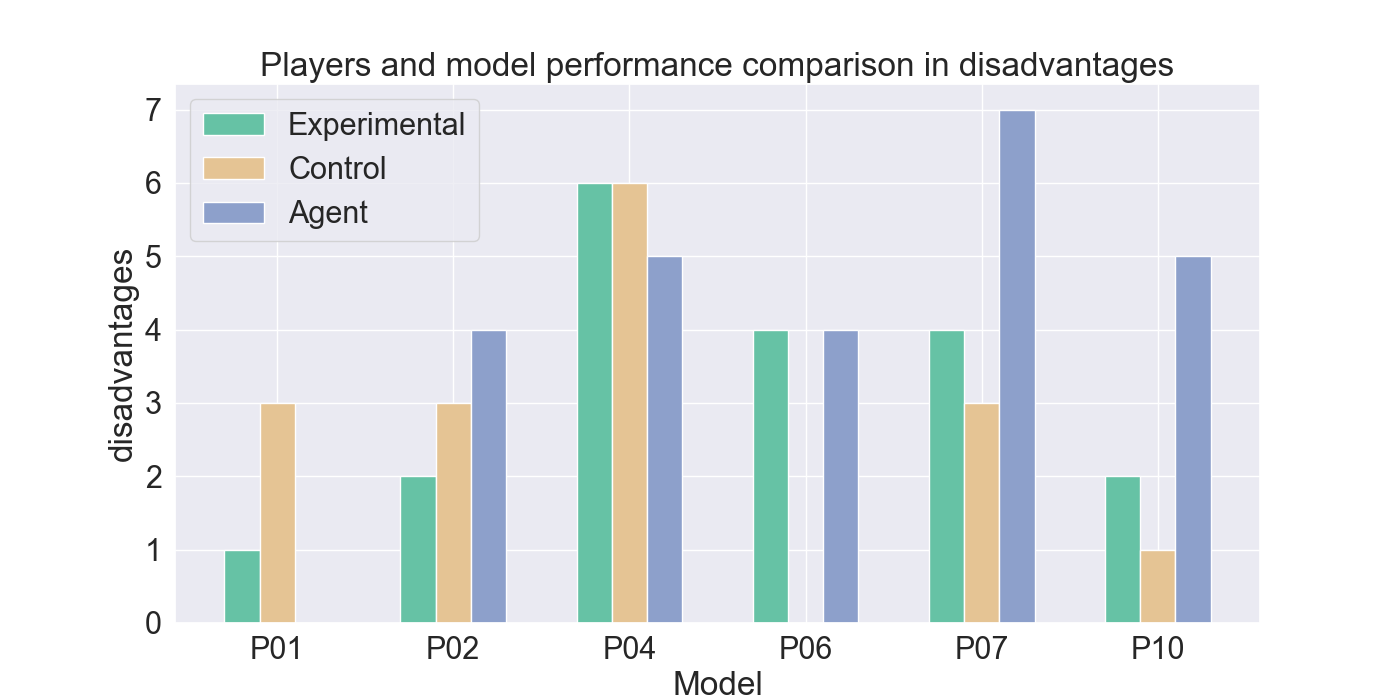

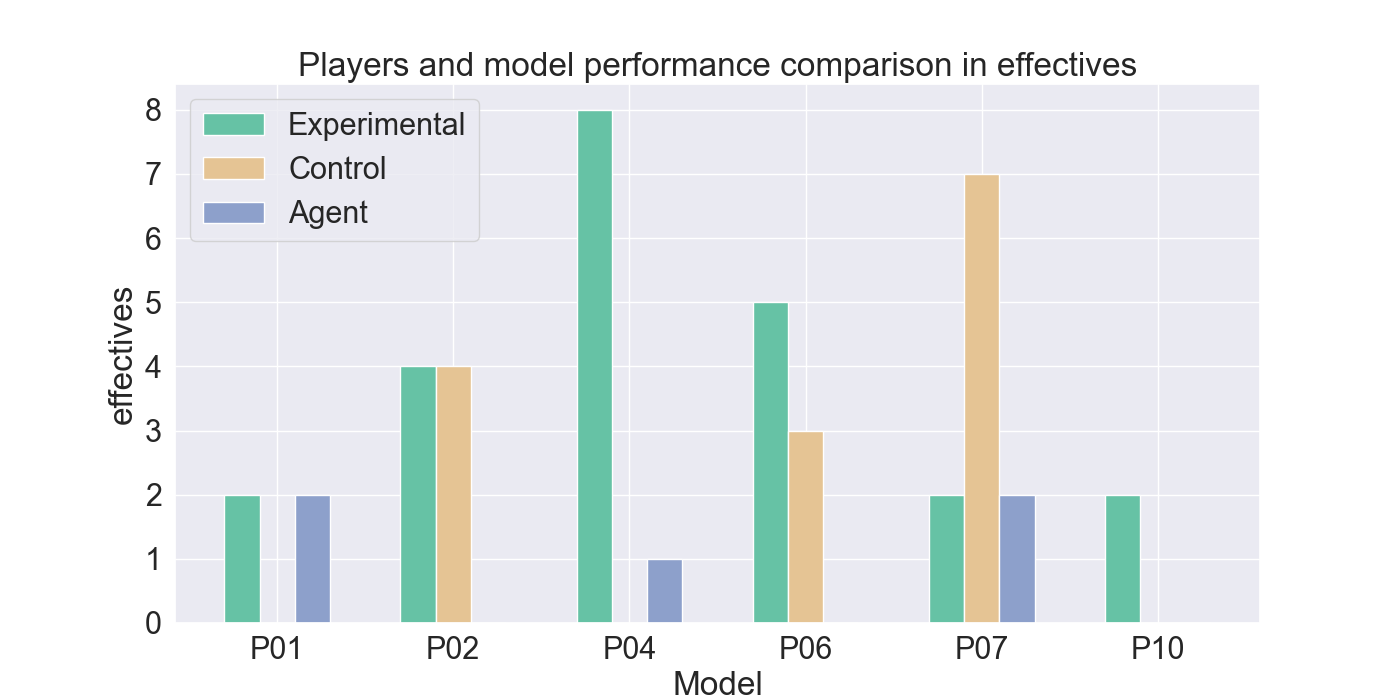

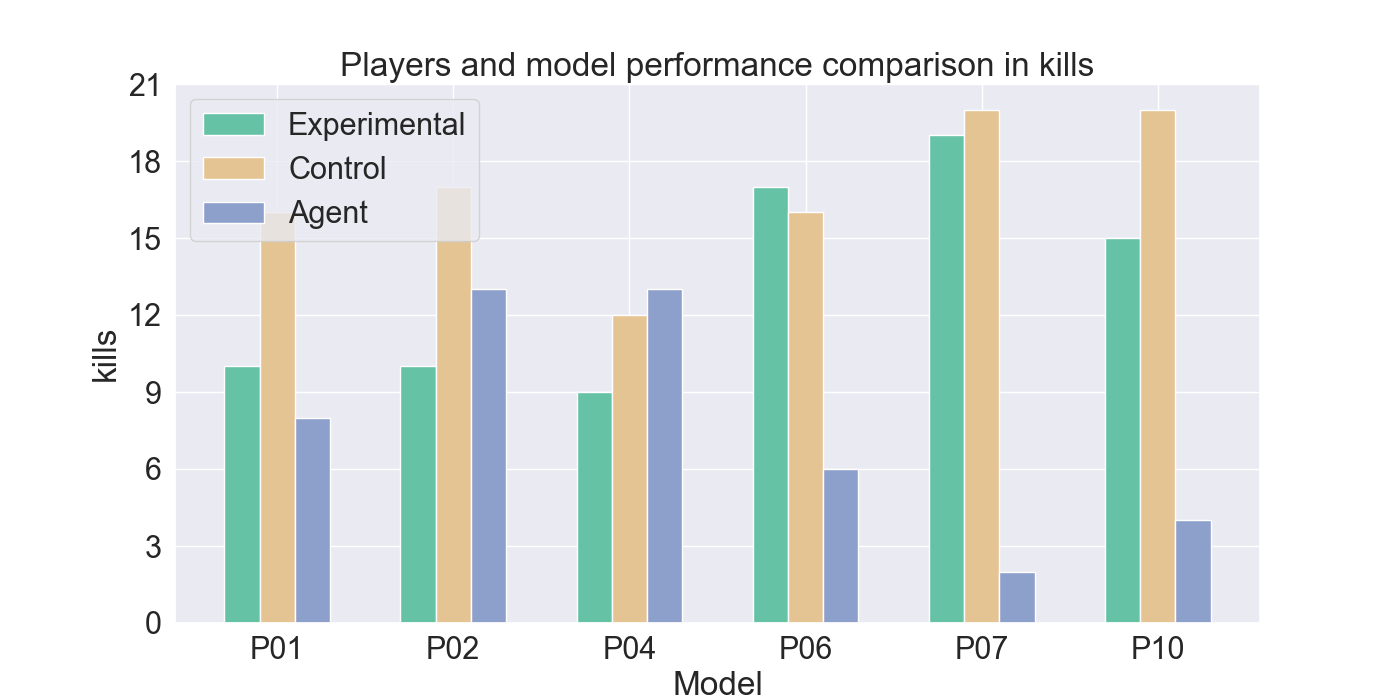

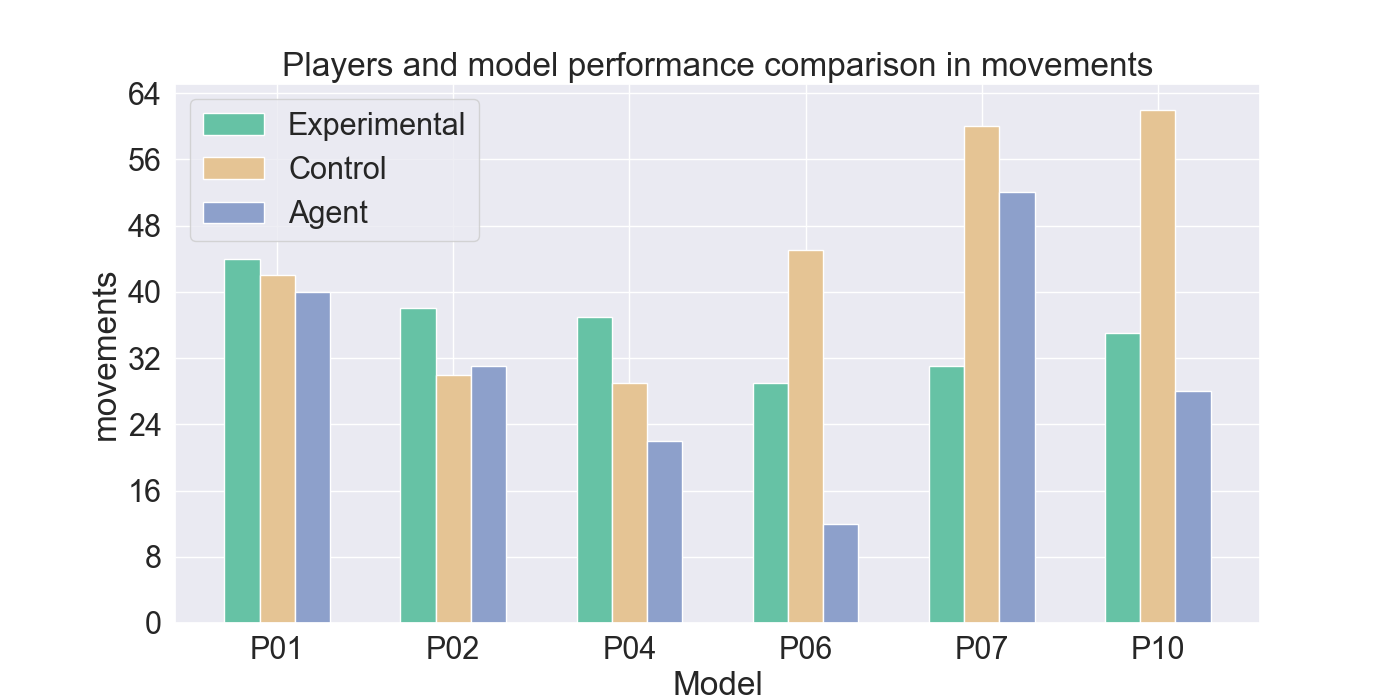

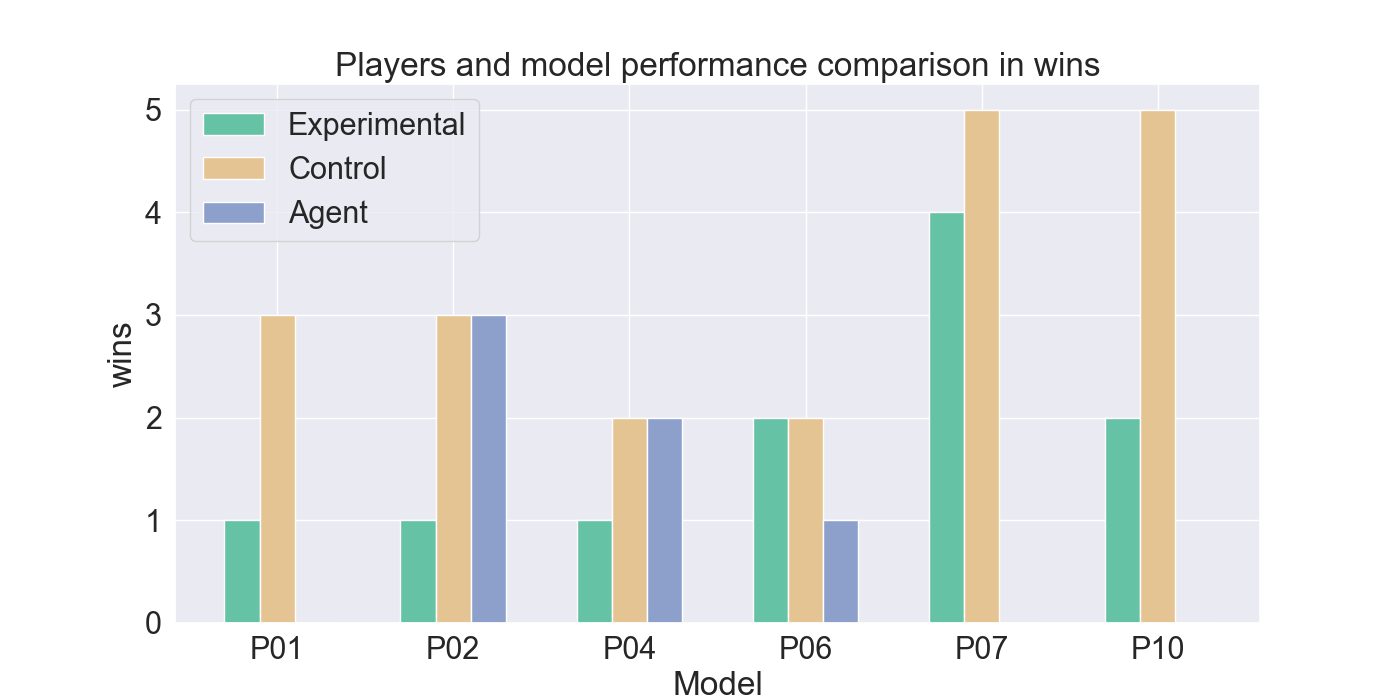

The measured performance metrics of the participants and the agent are presented in the results given in Figure 9. The agent performance metrics were taken in a total of 10 rounds: for both the experimental and control participant five rounds each. The total measured score was therefore divided by two, to calculate the average performance of the agent for each participant the agent competed against. High similarity between the agent and experimental metrics, together with low similarity to the control-group metrics, indicates strong imitation quality. Similar metric values between the control and agent bar indicate that it cannot be assured that the agent imitates the player presented by the experimental bar.

The results indicate that Mirror Mode models struggle to imitate offensive behavior. The agents rarely perform attacks and fail to replicate effective and advantage attacks, compared to their corresponding participants. However, Figure 9d shows that the agents closely resemble the movement patterns from the experimental players they were trained on. In particular, agents trained on P01, P02, and P10 demonstrate a strong alignment with their player behavior. In contrast, P04, and P06 use fewer movement actions, while P07 shows considerably more movements than its participant.

When comparing the death rate in Figure 9b from the Mirror agents to the participants, it is noticeable that the Mirror agents show a higher death rate, than most participants. However, in most models the death rate closely matches that of the experimental participant it was trained on. Suggesting that agent’s skill level is adapted to that of the corresponding player. Notably, the death rates for P06 and P07, are higher than the rates from their participants. Similarly, the kill rates for P06, P07, and P10 are substantially lower than those of their corresponding participants.

It can be noted that the Mirror agents generally show low similarity to the control participants, supporting the idea that they are primarily imitate the strategies of the experimental group players. However, Figures 9g and9h indicate lower similarity with the experimental participants for these metrics, highlighting less accurate imitation in offensive tactics.

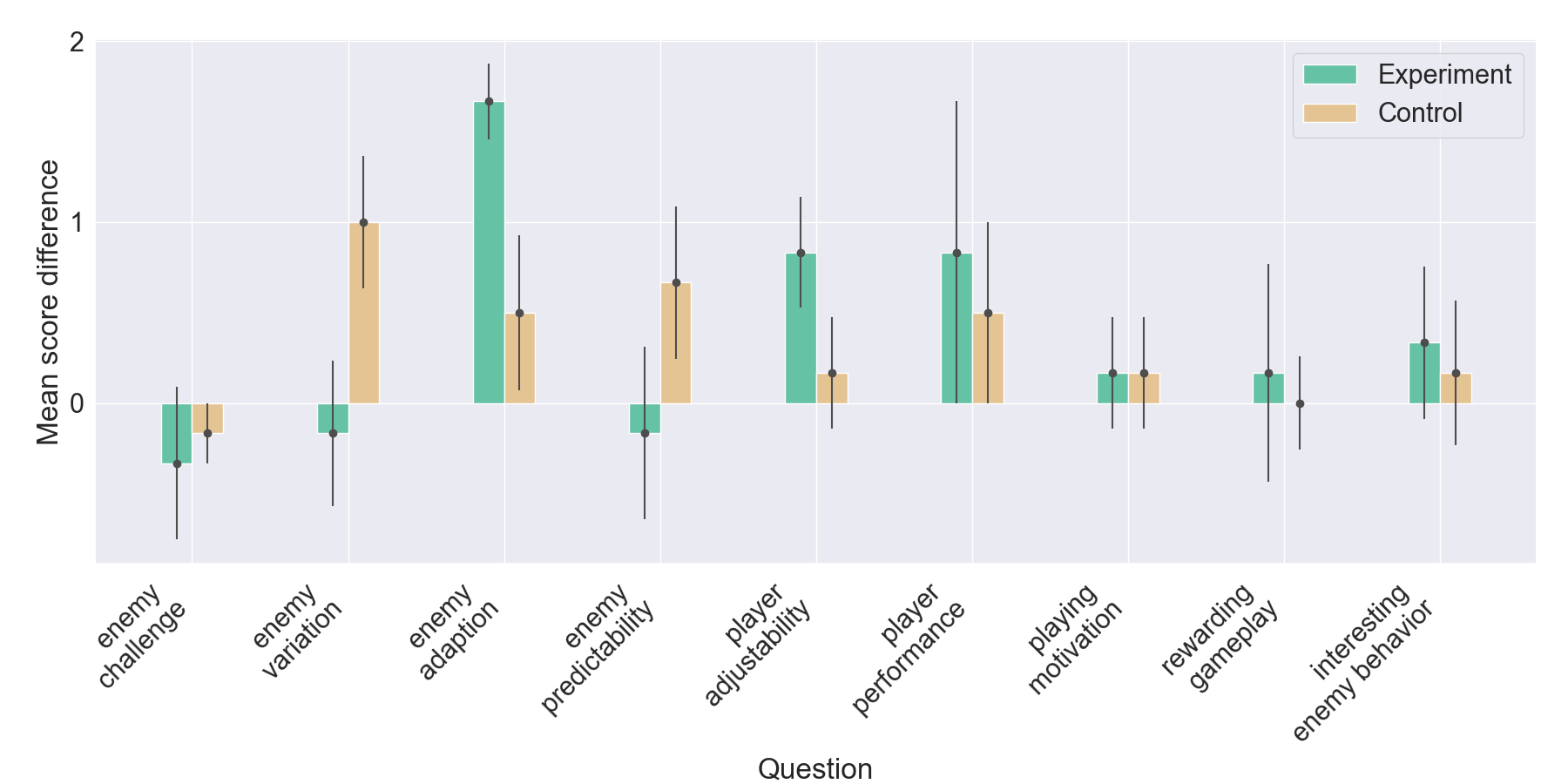

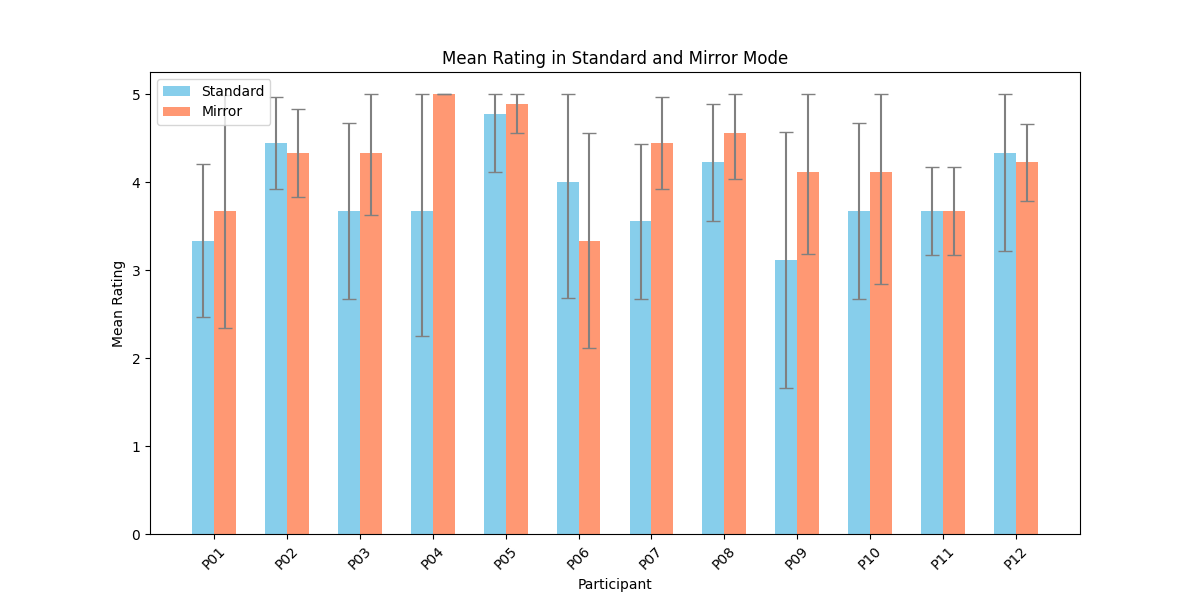

These observations suggest that while Mirror agents effectively replicate movement behavior from the experimental players, they lack behind in imitating offensive strategies. Nonetheless, the alignment in death rates with the original players indicates a degree of skill-level adaption in the trained models. 5.5.2 Questionnaire. For each of the nine rating questions, the difference in score was calculated across all participants, separately for the experimental and control groups. The mean difference in score across all participants in both groups is presented in Figure 10. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM), providing an indication of the precision of the estimated group means. The yaxis lists question themes, the x-axis shows the difference in mean score, with differences calculated as 𝑀𝑖𝑟𝑟𝑜𝑟𝑀𝑜𝑑𝑒 -𝑆𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑑𝑎𝑟𝑑𝑀𝑜𝑑𝑒.

Higher values indicate greater satisfaction in Mirror Mode, while smaller SEM reflects greater confidence. Results suggest increased satisfaction in enemy adaptability and player adjustability, but a decline in perceived challenge.

Interestingly, the control group found the enemy tactics less predictable and more varied compared to experimental participants. A possible explanation for this could be that experimental participants were fighting against their own tactics, making it easier for them to predict the choices made by the enemy. Only minor differences were observed in player’s motivation to continue playing, their sense of rewarding gameplay, and their perception of enemy’s behavior being interesting. Lastly, it can be noted that the enemy challenge went down, emphasizing the observation in higher challenge of Standard Mode. Some questions show relatively large SEM values, indicating uncertainty in the mean score differences. In particular, player performance and rewarding gameplay show a high SEM value, suggesting these scores may not accurately represent the underlying sample group. The larger error bars may partly reflect the small number of participants in each group.

The mean of the total satisfaction scores are calculated for each participant in both Standard Mode and Mirror Mode, presented in Figure 11. Despite P06 and P12 giving a higher satisfaction score for Standard Mode, most participants were more satisfied in Mirror Mode compared to Standard Mode. This suggests a positive influence on their game experience by Mirror Mode. However, both modes score generally high, indicating only little effect of Mirror Mode on overall game satisfaction. The standard deviations are generally similar across the two modes, indicating comparable variability in responses overall and similar range of satisfaction. However, variability differs notably between participants. Participant P04 is particularly noteworthy, showing a very high standard deviation in Standard Mode but zero deviation in Mirror Mode, highlighting the increase in satisfaction for Mirror Mode.

Furthermore, participants’ description of the enemy behavior differences of the two modes particularly also indicate the perception of the difference in offensive and defensive play style of the enemies, as shown in Table 3. Participants in the experimental group noticed the mirroring behavior from the enemies in Mirror Mode, imitating their defensive behavior from the standard game, such as P10 who is staying back, P06 who is less protective towards the magic unit, and P01 who is more likely to retreat. Only a few in the control group recognized their own strategies in the enemy tactics

P05 B I noticed that the enemy behaviour changed with respect to my performance, and it was harder than before. P03 B I feel like the enemy backed off more often in the 2nd mode. And also that they attacked one of my people that I brought forward more often, so I could adjust my strategy better. P02 A

The enemy behavior was more unpredictable which kept it very interesting P08 B It was smarter, less greedy and taking steps more carefully. It would sometimes retreat or do surprise attacks which was unexpected. P09 B Enemies would walk further away from you making you chase. Enemies did not always go on the offensive like it seemed in the first round. P11 B Honestly i thought they were way more defensive rather than just attacking every time they could:) P10 A

The enemy was staying back more, as I did. P06 A Second mode used the same units as me. Also, the magic unit was not protected as well which is a habit I have. P01 A It mirrored my strategy. So it kept escaping rather than attacking. P04 A Played more safe and felt really dynamic given the game state P07 A

The biggest difference was that the enemy decided to reposition a lot more and play more defensive, which made it a lot more challenging to attack effectively. P12 B They run away more. Used the strategy I used in the first 5 rounds but less smart executed in Mirror Mode, such as P05 and P12, than in the control group.

Overall, participants reported a change in enemy strategy, moving from offensive behavior to defensive when shifting from Standard Mode to Mirror Mode. Total satisfaction scores for each mode and participant are provided in Table B in the Appendix. Comparisons of overall satisfaction between the two modes show no significant differences. A two-tailed paired t-test with 𝛼 = 0.05 resulted in 𝑝 = 0.2566 for the experimental group and 𝑝 = 0.1144 for the control group.

Another significant test examined the relation between playing against one’s own tactics versus another player’s tactics. An independent t-test resulted in a p-value of 𝑝 = 0.9153, indicating no significant difference between the two conditions. This surprisingly large number, suggests that what specific human demonstrations are used has minimal influence on the game experience, as long as the demonstrations likely encourage more human-like behavior.

Statistics have shown a reduction in the popularity of strategy video games [28], potentially being caused by the repetitive and predictable behavior from NPC enemies [5,17]. Prior studies have found advanced techniques to incorporate AI with video games, making it more enjoyable for players [1]. Building on this, this study introduced a new game mode in strategy video games called Mirror Mode, where the enemy agents are trained on the playing behavior of players so the agents mimic their strategy.

Even though, the experimental results demonstrate promising indications of defensive imitation in Mirror Mode, further improvements are necessary for the agents to mimic a player’s overall strategy. Offensive tactics proved more challenging to replicate, with agents frequently holding back to initiate attacks or failing to exploit advantageous or effective actions. There are several reasons likely causing this behavior:

• Learning to attack properly requires the agent to learn to recognize when an opponent can be attacked, and from which tile they can attack that chosen opponent. This gives two additional steps compared to the singular act to move to a different tile. • The standard enemy AI had a high challenge, causing participants to struggle to defeat them and forcing them to retreat. As observed, players showed a higher death rate in Standard Mode, and rated the enemy AI as more challenging. This suggests a potential domino effect, where players who performed suboptimally in demonstrations, inadvertently transferred those struggles to their agents. Consequently, the agents inherited and reproduced similar results during training and their final model. • The models were trained for 1M steps. This may have not given enough time for the agent to learn proper attacking behavior.

Future work should focus on improving the game to decrease the challenge from the Standard Mode by incorporating more elements from the original games, such as abilities. Ideally, a testing environment within the real mobile game of Fire Emblem Heroes could develop more insights, reaching a larger audience, and enable realtime gameplay over an extended period of gameplays. This would allow the model to continuously integrate new demonstrations and adjusts to new player strategies that involve counter strategies developed against their own behavior. We also recommend a larger user study in order to achieve statistically significant results more easily.

Moreover, in-game evaluation can be used to assess imitation quality of different configured models, for real game performance and imitation insights, to find the most optimal model configuration. Refinements to the reward system are also necessary. In particular, providing explicit rewards for replication actions from recorded demonstrations. This could further improve imitation performance.

This research introduces a new gameplay mode called Mirror Mode, for turn-based strategy games. It is found that RL and IL techniques from the Unity ML-Agent package provided by Juliani et al. [15] show big potentials for teaching agents to copy the strategy of a player, in particular defensive tactics.

The first half of the study focused on providing a model for Mirror Mode. Leading to an answer to the question: “To what extent can RL and IL be applied to teach NPCs a player’s strategy in a turnbased strategy game?” It can be concluded that IL has a strong potential in teaching enemy agents a player’s strategy, with the proper configurations to maintain the imitation-exploration tradeoff. RL is more adaptable in finding its own strategy, and less suitable for copying player’s strategies. Therefore, IL is more preferable for the specific purpose of teaching NPCs a player’s strategy, with PPO and extrinsic rewards ensuring a good agent performance.

The second half of the study provided insights on the imitation quality in Mirror Mode, and the experience when playing this mode. Game metrics were taken from the participant’s gameplay, indicating a good imitation in defensive behavior rather than offensive tactics. Participants recognized their own retreating tactics in the Mirror Mode enemies. Surveys were taken to rate the participant’s game satisfaction for both modes, resulting in an overall higher satisfaction for Mirror Mode, though not significant yet.

In addressing the general question “How will a player’s game experience be influenced when NPCs imitate their strategy in a turnbased strategy game?”, this study therefore shows that the overall satisfaction of the game is moderately increased. Participants enjoyed Mirror Mode better due to the less predictable enemy behavior and their recognized defensive strategies, but making them easier to defeat.

In conclusion, Mirror Mode can increase the satisfaction of players in strategy games. Whether this can increase the popularity of strategy games remains to be discussed, but this study takes a first step.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. LIACS, Leiden © 2025 Copyright held by the owner/author(s).

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.