SWE 플레이그라운드 인공지능 코딩 에이전트를 위한 합성 프로젝트 생성 파이프라인

📝 Original Info

- Title: SWE 플레이그라운드 인공지능 코딩 에이전트를 위한 합성 프로젝트 생성 파이프라인

- ArXiv ID: 2512.12216

- Date:

- Authors: Unknown

📝 Abstract

Prior works on training software engineering agents have explored utilizing existing resources such as issues on GitHub repositories to construct software engineering tasks and corresponding test suites. These approaches face two key limitations: (1) their reliance on pre-existing GitHub repositories offers limited flexibility, and (2) their primary focus on issue resolution tasks restricts their applicability to the much wider variety of tasks a software engineer must handle. To overcome these challenges, we introduce SWE-Playground, a novel pipeline for generating environments and trajectories which supports the training of versatile coding agents. Unlike prior efforts, SWE-Playground synthetically generates projects and tasks from scratch with strong language models and agents, eliminating reliance on external data sources. This allows us to tackle a much wider variety of coding tasks, such as reproducing issues by generating unit tests and implementing libraries from scratch. We demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach on three distinct benchmarks, and results indicate that SWE-Playground produces trajectories with dense training signal, enabling agents to reach comparable performance with significantly fewer trajectories than previous works. Project Page: neulab.github.io/SWE-Playground📄 Full Content

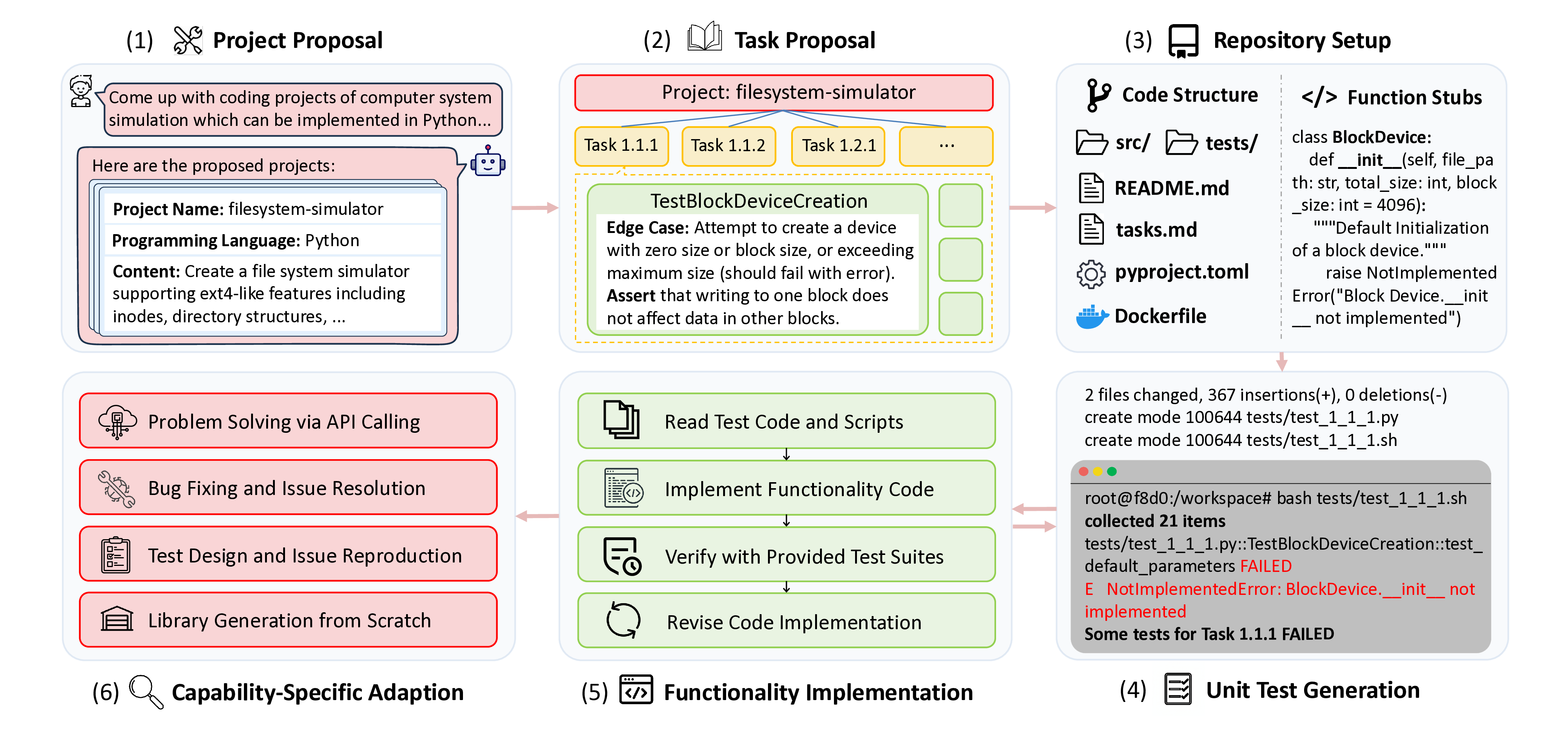

In this paper, we introduce SWE-Playground, a fully automated pipeline that synthetically constructs software engineering environments, including training tasks, starter code, and unit tests, from the scratch, for developing versatile coding agents. Using frontier LLMs and agents, the pipeline proposes a full software project, decomposes it into verifiable tasks, and automatically creates the repository scaffold along with matching unit tests. Implementations are then evaluated against these tests, providing a reliable reward signal for training agents.

A key advantage of SWE-Playground lies in its inherent flexible framework. By synthetically creating all tasks and verification tests from scratch, our pipeline avoids any reliance on external resources. To demonstrate this adaptability, we extend our pipeline to support issue resolution and reproduction tasks via issue proposal and injection, and to create library generation tasks by stubbing out the generated implementation. This approach enables the collection of a rich and diverse training dataset, containing trajectories for both de novo project development and targeted issue resolution and reproduction. Since the entire pipeline operates without manual intervention and can be readily adapted to new tasks, often requiring little more than writing a different prompt to target a new domain, it presents a more scalable and cost-effective paradigm for wider adaption in the training of coding agents.

Using trajectories collected exclusively from SWE-Playground, we train models to validate the effectiveness of our approach. Our model consistently demonstrates superior performance over the base model across three distinct benchmarks that assess a wide range of coding capabilities. In stark contrast, agents trained on prior environments, such as SWE-Gym (Pan et al., 2025) and R2E-Gym (Jain et al., 2025b), which are typically limited to SWE-bench format tasks, exhibit limited generalization to these benchmarks. While they show minor gains on some out-of-domain tasks, these improvements do not match their source domain performance, and they suffer noticeable degradation on others. This result highlights that though prior environments successfully produce specialized agents that excels at SWEbench, our SWE-Playground is capable of cultivating robust and generalizable coding proficiency, and thus developing versatile coding agents. SWE-Playground produces trajectories with dense training signal. Our experiments collect 704 trajectories, a set significantly smaller than those used by R2E-Gym (Jain et al., 2025b) and SWE-smith (Yang et al., 2025b). Despite this smaller dataset, our models achieve comparable performance. Further analysis reveals that our trajectories are substantially richer, containing more tokens and tool calls on average compared to those from previous environments. Moreover, they feature a higher proportion of bash execution, demonstrating a paradigm of execution-based software development rather than simple code generation. We attribute this high data efficiency to the dense and complex nature of SWE-Playground tasks and generated trajectories.

- What Makes a Good Software Agent?

Software engineering is a multifaceted discipline that extends far beyond merely writing code, encompassing tasks such as designing, coding, testing, and debugging. Underscoring this, Meyer et al. (2019) studies the work of human software developers and finds that only 15% of their time is spent actively coding. Moreover, code development itself is not monolithic, and it requires a diverse set of specialized skills for effective software engineering.

Fortunately, there are a variety of benchmarks designed to evaluate the capabilities of language models to tackle these various coding tasks. SWE-bench (Jimenez et al., 2024) is the canonical benchmark for the “issue in, patch out” bugfixing use case, focusing on popular Python repositories. SWE-bench-Live (Zhang et al., 2025b) addresses the static limitations of SWE-bench, introducing a live and automated pipeline that curates fresh, contamination-resistant tasks from real-world GitHub issues. SWE-Bench Pro (Deng et al., 2025) also builds upon SWE-bench with more challenging tasks to capture realistic, complex, enterprise-level problems beyond the scope of SWE-bench.

In addition to this specific issue resolution paradigm, benchmarks are emerging to cover other critical aspects of the code development lifecycle:

• Building Libraries from Scratch: Commit-0 (Zhao et al., 2024) tasks models with rebuilding and generating the entire library from the initial commit.

• Multilingual Bug Fixing: Multi-SWE-bench (Zan et al., 2025) and SWE-bench Multilingual (Yang et al., 2025b) cover a wider range programming languages beyond Python, including C++, TypeScript, Rust, etc.

• Multimodal Understanding: ArtifactsBench (Zhang et al., 2025a) and SWE-bench Multimodal (Yang et al., 2025a) test the capability to ground code generation and understanding in visual artifacts.

• Test Generation: SWT-Bench (Mündler et al., 2024) and TestGenEval (Jain et al., 2025a) evaluates model performance on reproducing GitHub issues in Python.

• Performance Optimization: SWE-Perf (He et al., 2025), SWE-fficiency (Ma et al., 2025), and Kernel-Bench (Ouyang et al., 2025) benchmark models on optimizing code performance in diverse scenarios and programming languages.

A full comprehensive review can be found in Appendix A.

Several recent works have focused on developing specialized environments for training SWE agents. SWE-Gym (Pan et al., 2025) first explores the construction of environments for training SWE agents with pre-installed dependencies and executable test verification derived from real-world GitHub issues. R2E-Gym (Jain et al., 2025b) proposes a synthetic data curation recipe to create execution environments from commits through backtranslation and test collection or generation, which removes the reliance on human-written pull requests or unit tests. Similarly, SWEsmith (Yang et al., 2025b) facilitates automatic generation of scalable training environments and instances via function rewriting and bug combination. SWE-Mirror (Wang et al., 2025a) further scales this by mirroring issues across repositories. SWE-Flow (Zhang et al., 2025c) utilizes Test-Driven Development (TDD) to produce structured development tasks with explicit goals directly from unit tests, thereby generating training instances.

However, crucially, while these environments represent significant progress, they share a fundamental limitation that they largely rely on existing GitHub repositories to source their data. This approach inherently restricts the diversity and availability of tasks to what can be mined from public code. Consequently, it remains difficult to acquire balanced training data that covers the full spectrum of aforementioned skills for training a versatile coding agent. This bottleneck can be exacerbated by the extensive manual effort required for filtering, verifying, and packaging these real-world issues into training environments. Leveraging a fully automated pipeline that spans from project proposal to functionality implementation, SWE-Playground attempts to address this fundamental problem.

In this section, we elaborate on the pipeline of SWE-Playground and how we can collect high-quality data for training versatile coding agents with our proposed pipeline. The pipeline is illustrated by Figure 2, and prompts used can be found in Appendix D.

The pipeline of SWE-Playground begins with an LLM call requesting a project proposal aligned with a specific domain of coding problems we aim to generate for. This generation process is steered by a prompt that rigorously defines various parameters of the project. In our implementation, as detailed in Appendix D.1, we prompt the agent to achieve particular high-level attributes such as project topic and programming language, and granular, robustness-ensuring constraints that are critical for maintaining quality, including:

• Scope and complexity metrics to guarantee scale, specifically requiring projects to involve multicomponent architectures and a minimum volume of core logic rather than simple. Crucially, these constraints are highly adaptable. By simply modifying the system prompt, the requirements can be tailored to suit a wide range of use cases, ensuring the flexibility of our pipeline. Furthermore, to prevent mode collapse and ensure broad coverage, we require the model to generate multiple tasks simultaneously, thereby maximizing the diversity of the resulting project pool.

Following the proposal stage, each project is processed independently to decompose the high-level requirements into executable units. To ensure a logical and organized implementation flow, we employ a hierarchical generation structure: the project is first divided into distinct phases, then modules, and finally concrete tasks, simulating the real-world project implementation process.

Come up with coding projects of computer system simulation which can be implemented in Python…

Here are the proposed projects: In this stage, achieving optimal task granularity is critical. We instruct the model to maintain a balanced workload by defining tasks at the granularity of a single pull request, ensuring they are substantial yet manageable. For example, typical tasks include scaffolding base data structures, implementing core algorithms, or developing user interface components. Furthermore, to maintain a focus on high-value engineering, we restrict the hierarchy to a maximum of five phases and explicitly exclude auxiliary activities such as documentation or deployment, forcing the agent to concentrate solely on building core functionality with clear logical dependency chains.

Once a task is defined, we generate a corresponding detailed checklist that provides a granular explanation and explicitly specifies the requisite unit tests, standard cases, specific assertions, and potential edge cases. This practice offers two primary advantages. First, unit tests serve as a reliable reward signal. Though previous works have explored training software engineering verifier models for inference-time scaling (Pan et al., 2025;Jain et al., 2025b), unit tests remain more trustworthy provided that current language models and agents can generate adequate tests (Chou et al., 2025). Second, the detailed checklist acts as a clear guide, steering the agent in implementing unit tests in the later stage.

Please refer to Appendix D.2 for the detailed prompt used for task proposal in our experiments.

After the project proposal and step-by-step tasks are generated, the pipeline moves to the setup stage. An agent is in charge of establishing the foundational code structure, delineating necessary files, utilities, and function stubs without implementing any core functionality. Such practice ensures that all subsequent work is carried out within a predefined scaffolding, thereby confining the scope of implementation and preventing disorganized development. Furthermore, we also request the agent to generate environmental dependencies and Docker related files, allowing for the creation of a readily executable sandboxed environment.

Once the project scaffolding is in place, a dedicated agent1 is responsible for generating the unit tests. The agent is guided by the checklist formulated during the task proposal stage, which ensures comprehensive test coverage and the implementation of all necessary tests. Operating as an agent, rather than a static LLM, provides the ability to access existing files and execute its own generated tests. This active verification capability ensures tests can correctly import dependencies, invoke functions, and produce expected errors.

To standardize the evaluation pipeline across diverse

@@ 39,8 +39,3 @@ 39 39 def init(self, total_size, block_size): 39 39

“““Initialize a block device " projects, we require the agent to generate a uniform execution entry point for each task. This script orchestrates the environment setup and executes the unit tests, ensuring a consistent interface for the training loop. Furthermore, the generation process applies domain-specific verification criteria, such as enforcing numerical stability for mathematical tools, concurrency safety for database engines, or serialization compliance for network protocols.

In this stage, the mandate of our agent is to focus solely on the test requirements without anticipating how the functionality will be implemented. It is required to be maximally strict, compelling the subsequent implementation to conform precisely to these requirements to pass. This strictness is essential for preventing faulty implementations, even at the cost of increased implementation difficulty.

From project proposal to unit test generation, the pipeline prepares a coding project together with the unit tests, which collectively forms the environment for training coding agents. Following this, the agent, either trained or used for distillation, implements the core functionalities based on task instruction. In our implementation, the agent is given access to the unit test code. We find this necessary because as previously noted, the implementation of unit tests is highly rigorous and offers no tolerance for implementation deviations. Without this access, achieving a passing solution would be exceptionally difficult for the agent. It is worth noting that the adoption of such configuration is flexible, depending on both features of the generated unit tests and performance of the agent.

After the agent completes the implementation, the test suites in the repository are replaced with the original tests produced during the test generation stage, which is a critical step to mitigate the risk of reward hacking, where the agent might otherwise pass tests by directly editing the test code. The original unit tests are subsequently executed to verify the correctness of implementation. This overall process leverages a similar idea to the concept of self-questioning (Chen et al., 2025), as unit test generation and functionality implementation form a mutual verifica-tion loop. An issue in either stage, be it a flawed test or an incorrect implementation, will lead to the failure of unit tests, thereby adding to trustworthiness of the generated unit tests. and also robustness of the entire verification process. Notably, we alternate between unit test generation and functionality implementation, forming a loop. This approach ensures that subsequent unit tests are adapted to the the cumulative functionality, which simplifies the implementation the implementation process by removing the need of revisiting or modifying the previously validated code.

In our implementation, we mandate that the agent does not access the provided unit tests initially. Instead, it is encouraged to construct its own verification scripts based on the task description, a practice that simultaneously cultivates its test generation capabilities.

The above pipeline supports the creation of general repository-level coding tasks. However, as discussed in Section 2.1, software engineering requires solving a variety of tasks beyond this. To demonstrate the flexibility of SWE-Playground, we showcase in this section how our pipeline can be adapted to generate tasks for three distinct use cases over which we measure performance in our experiments. Prompts can be found in Appendix D.6.

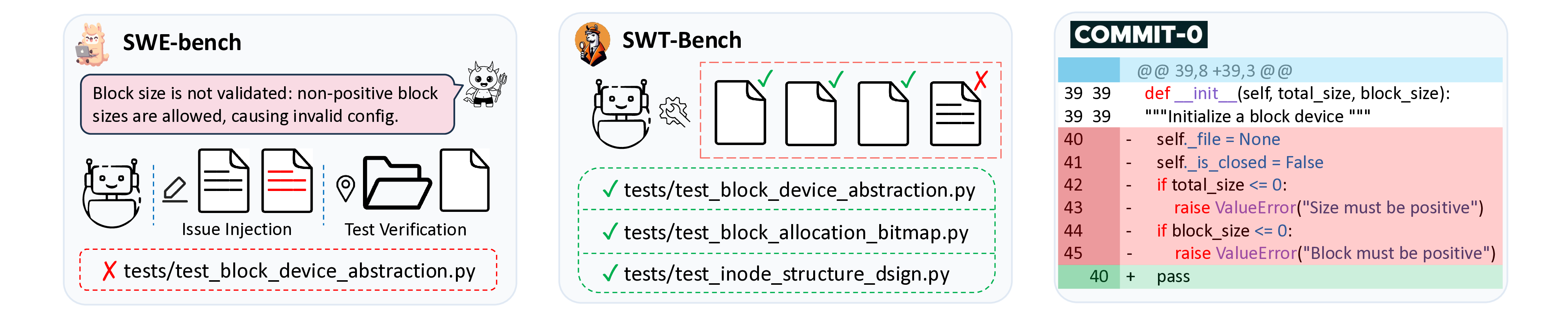

Issue Resolution: SWE-bench (Jimenez et al., 2024) is the canonical benchmark for software engineering tasks, and it features resolving real GitHub issues. This task setting requires a repository that is generally functional but contains a minor bug affecting certain functionalities. With our pipeline, a functional repository already exists, with the only remaining task being the generation of a specific issue and its injection into the code. Similar to Yang et al. (2025b), we first leverage an LLM to formulate an issue based on the unit test documentation and code of the task, and then call an agent to inject the issue into the repository. The existing test suites can directly verify the correctness of the injection, where a failing test serves as the success signal.

Test Generation: SWT-Bench (Mündler et al., 2024) velop unit tests to reproduce issues. For this setting, beyond injecting the issue into the repository, we also require the agent to modify the test suites so that the injected bug is no longer directly detectable. The agents are then tasked with formulating a test script that exposes the faulty behavior and then integrate this script into the existing test suites to complete the task, a procedure identical to SWT-Bench.

Generating Libraries from Scratch: Commit-0 (Zhao et al., 2024) evaluates agents on constructing the entire repository from scratch, with no step-to-step decomposition. For this setting, the complete and functional repositories generated by our pipeline serve as the target artifacts and reference implementation. To simulate the Commit-0 task format, we replace all function bodies with pass statements and then prompt agents to re-implement the project. Notably, we do not use the existing test suites to verify implementation correctness in our experiments. Instead, we let the agent attempt the full task and directly collect its trajectory, which aligns with a pure distillation setting. We adopt such strategy out of the practical necessity. Because our pipeline separates functionalities into step-by-step tasks and the unit tests are designed to be inherently stringent, it is challenging for the agent to pass all tests within a single call.

With our proposed SWE-Playground pipeline, we collect from 28 generated projects a total of 280 general trajectories (as detailed in Section 3.1 to Section 3.5) and 424 task specific trajectories (as detailed in Section 4), respectively 213 for issue resolution, 183 for issue reproduction and 28 for library generation. Following Pan et al. (2025) and Jain et al. (2025b), we use OpenHands (Wang et al., 2025b) CodeAct Agent our agent Scaffold, and select Qwen-2.5-Coder series (Hui et al., 2024) as our the base model. We adopt SWE-bench Verified (Chowdhury et al., 2024), SWT-Bench Lite and Commit-0 Lite as the evaluation splits for the respective benchmarks. We provide details in Appendix B. agents to overfit to a narrow task distribution, hindering their development of versatile coding skills. Conversely, the varied nature and task adaptation strategy of the trajectories generated by SWE-Playground can foster stronger crosstask performance, enabling agents to be more robust and generalizable. As we have argued, all these coding benchmarks hold equal importance for real-world application, and a truly capable coding agent should be competitive across the entire suite of tasks.

7B models and 32B models perform inconsistently. According to our result, 7B and 32B models exhibit distinct performance patterns. Firstly, on SWE-bench Verified, models trained with SWE-Gym, R2E-Gym, and our SWE-Playmix show similar improvement trends on the resolved rate. The improvement of 32B models is consistently around 1.6 times that of 7B models, with the only exception being SWE-smith, which uses significantly more trajectories for training its 32B model. On the empty patch rate for 32B models, the base model is already highly competitive, causing SWE-Gym-32B to ultimately underperform it. However, even under this circumstance, our SWE-Play-32B still achieves a lower empty patch rate, demonstrating the robustness of our collected data. Secondly, on SWT-Bench, though SWE-Gym and R2E-Gym both exhibit comparable results to the baseline for 7B models, their performance consistently degrades for 32B models. This is likely because the Qwen2.5-Coder-7B is already mostly incapable of these tasks, meaning its performance is already at a floor and cannot be degraded further. However, for the more capable Qwen2.5-Coder-32B, this performance gain is lost, demonstrating that these methods are inherently detrimental to model capability of reproducing issues as evaluated by SWT-Bench. However, SWE-smith models show a completely different pattern on this benchmark. SWE-smith-7B, which achieves a higher coverage delta while failing to solve any instances, is far surpassed by the performance of SWEsmith-32B which demonstrates a strong improvement.

To investigate how different trajectory types influence model performance, we conduct an ablation study by training an-other two 7B model: SWE-Play-general with 280 generalpurpose trajectories, and SWE-Play-swe with 213 issue resolution trajectories, as described in Section 5.1. The results are presented in Table 2.

Results indicate that training solely on general trajectories yields performance gains on three of the four metrics. The only exception is a nearly same coverage delta on SWT-Bench. Such finding demonstrates that generalist training, which focuses on implementing functionalities within large code repositories, effectively develops core coding abilities for the agents. We attribute this success to the intrinsic design of the SWE-Playground task proposal and data collection pipeline. Firstly, in our tasks, models are required to build projects from a blank template, a process analogous to generating a library from the initial commit of Commit-0.

Secondly, the natural process of implementing new functionality often involves identifying and resolving bugs, which directly enhances model performance on issue resolution tasks in SWE-bench. Finally, during data collection, we explicitly prompt the model to write its own test scripts before implementing the core functionalities or accessing provided test files. This practice empowers the model with the skills of unit test generation and issue reproduction. Consequently, though not identical in prompt format and task type to SWEbench, SWT-Bench, or Commit-0, the general trajectories still result in substantial performance improvement.

Furthermore, as expected, training with issue resolution trajectories boosts model performance on SWE-bench Verified. While SWE-Play-swe slightly outperforms SWE-Playgeneral on this specific benchmark, it lags considerably behind SWE-Play-mix, which is trained on a combination of all collected trajectories, containing all data used for SWE-Play-swe, plus the general trajectories and additional trajectories tailored for issue reproduction and library generation.

The superior performance of SWE-Play-mix highlights the importance of data diversity.

Given that general and issue resolution trajectories are known to boost performance, we further seek to validate the contribution of our other two types of trajectories: issue reproduction and library generation. We hypothesize that these trajectories provide complementary skills, leading to a synergistic improvement. To test this, we train an ablation model using only a mixture of general and issue resolution trajectories, and results are provided in Table 3. This ablated model achieves the same resolved rate on SWE-bench Verified as the model trained only with issue resolution trajectories, while both significantly outperformed by our full SWE-Play-mix model. This gap demonstrates that the inclusion of issue reproduction and library generation trajectories is the critical factor that contributes to the further improvement, proving their direct and positive influence on the issue resolution capability and confirming the effectiveness of cross-scenario transferability.

Results indicate that models trained on SWE-Playground achieve similar comparable performance with fewer trajectories. Within all the evaluated benchmarks for 7B models, SWE-Play-mix is only outperformed by R2E-Gym on SWEbench Verified, which relies on a training dataset nearly five times larger (3,321 trajectories versus our 704). Moreover, as specified in Section 6.1, our SWE-Play-swe-7B surpasses SWE-Gym-7B on SWE-bench Verified while using less than half the volume of identically formatted training trajectories.

Crucially, this efficiency advantage persists when accounting for the total tokens of training data. As detailed in Table 4, while our trajectories contain more tokens on average, the aggregate size of our dataset (∼27.5M tokens) remains significantly smaller than that of R2E-Gym (∼45.8M tokens). This confirms that SWE-Playground achieves competitive performance with reduced computational overhead, regardless of whether the cost is measured by instance count or total token consumption.

These outcomes raise a critical question: why can our framework demonstrate better data efficiency compared with various previous methods? To answer this, we perform a detailed comparative analysis of our trajectories against those from baseline studies, with the results presented in Table 4.

Our analysis reveals that trajectories generated with SWE-Playground are quantifiably more complex and comprehensive. As shown in the table, they contain two to three times more tokens and messages on average, including a higher number of assistant tokens, tool calls and lines of code edited, compared to other datasets. We characterize this quality as a higher learning density. This concept, in line with the Agency Efficiency Principle introduced by Xiao et al. (2025), suggests that trajectories dense with diverse and complex actions provide a more potent learning impetus per sample. The richness of our trajectories demonstrates this principle in practice, leading to greater data efficiency.

Furthermore, our trajectories exhibit a significantly higher proportion of bash execution actions. This indicates that the agent learns a more robust development methodology, dedicating more steps to inspecting the project structure and verifying its implementation rather than focusing narrowly on code generation. We posit that such emphasis on a realistic iterative workflow provides a more pragmatic learning foundation and thus yields a more capable agent. 4. Trajectory statistics for different datasets. We report the total number of trajectories (Total Count) and several metrics averaged per trajectory: number of messages (Message), total tokens (Token), assistant tokens (Assist Token), tool call trials (Tool Call), and edited code lines (Lines Edited). Bash Proportion is the percentage of bash executions among all tool calls.

In this paper, we present SWE-Playground, a novel environment for training versatile coding agents. Our results demonstrate that SWE-Playground supports training agents with strong performance across various coding benchmarks with a remarkably smaller dataset. We holistically argue that performance improvement on SWE-bench alone is insufficient, and proficiency across multiple benchmarks is critical for training coding agents.

While these results are promising, we identify two key directions for future work. Firstly, incorporating a broader set of benchmarks, such as SWE-bench Multimodal and SWE-perf, would further validate the extensibility of our framework, as their features align well with the generative capabilities of SWE-Playground pipeline. Secondly, conducting RL experiments is an interesting direction to explore the full potential of our environment generation pipeline. As we have argued, our pipeline creates a scenario where unit test generation and code implementation mutually verify each other. Training an agent to master both skills through RL could directly probe its capacity to develop self-verifying and, ultimately, self-improving coding agents like Liu et al. (2025).

In this paper, we present SWE-Playground, an automated pipeline to synthesize environments and trajectories for the training of versatile coding agents. We anticipate several potential impacts of this work. First, SWE-Playground offers a pathway to advance the field of automated software engineering. As discussed, real-world software engineering requires a diverse set of skills beyond simple code completion, and SWE-Playground offers a robust framework for incorporating and training these versatile capabilities.

From a broader perspective, with more research attention focused on the purely synthetic training data and self-evolving agents, SWE-Playground shows promising results for further research regarding these topics.

At the same time, although our experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of the SWE-Playground pipeline, rigorous quality control is essential if these systems are to be deployed in high-stakes scenarios. Furthermore, generating unit tests with LLMs remains an emerging research topic.

Currently, there is a scarcity of benchmarks designed to evaluate this specific capability, and few works have discussed it systematically. Consequently, further research is required before models can be fully and reliably incorporated for automated verification.

Coding Agents. Capable Large Language Models and robust agent scaffolds are two critical components of modern coding agents. Recent state-of-the-art language models include proprietary ones such as Claude Sonnet 4.5 (Anthropic, 2025b) and GPT-5 (OpenAI, 2025b), as well as open-source models such as Qwen3-Coder (Qwen Team, 2025), Kimi K2 (Kimi Team et al., 2025) and DeepSeek-V3.1 (DeepSeek-AI, 2024). For coding agents scaffolds, SWE-agent (Yang et al., 2024) introduces the concept of agent-computer interface which offers a small set of simple actions for interacting with files.

Building upon SWE-agent, mini-SWE-agent (Yang et al., 2024) achieves similar performance with a simpler control flow.

OpenHands (Wang et al., 2025b) expands on this by offering a wider action space including web browsing and API calls, enabling models to tackle more complex and diverse tasks. SWE-search (Antoniades et al., 2024) employs a multi-agent system and Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) strategy for planning to enhance flexibility during state transition. The combination of these powerful models and agent scaffolds enables coding agents to solve real-world coding challenges and even surpass the performance of human engineers on certain tasks (Li et al., 2025) .

Coding Tasks and Benchmarks. HumanEval (Chen et al., 2021) is the first coding benchmark to use an executable environment for verification instead of relying on vague text similarity, laying the foundation for subsequent work. Live-CodeBench (Jain et al., 2024) advances this by increasing the difficulty and evaluation coverage, gathering problems from contests across various competition platforms. BigCodeBench (Zhuo et al., 2024) challenges models to follow complex instructions to invoke function calls as tools for solving practical tasks. In addition to these function-level and file-level edition tasks, a large number of recent benchmarks have been designed to test the performance of models and agents on repository-level coding tasks. Commit-0 (Zhao et al., 2024) targets rebuilding existing libraries from scratch. SWE-bench (Jimenez et al., 2024) is also crafted from real GitHub repositories and challenges models to solve issues noted in pull requests. SWE-Bench Pro (Deng et al., 2025) builds upon SWE-bench with more challenging tasks to capture realistic, complex, enterprise-level problems beyond the scope of SWE-Bench. SWE-bench Multimodal (Yang et al., 2025a) and SWE-bench Multilingual (Yang et al., 2025b) both extend SWE-bench to evaluate more diverse abilities. SWE-bench Multimodal incorporates visual elements such as diagrams and screenshots to test whether modals can perform well on visual information. SWE-bench Multilingual covers nine different programming languages for the evaluation of various application domains. Multi-SWE-bench (Zan et al., 2025) is also a issue-resolving benchmark aiming to evaluate various programming languages. SWT-Bench (Mündler et al., 2024) evaluates model proficiency on reproducing GitHub issues in Python. TestGenEval (Jain et al., 2025a) measures test generation performance in well-maintained Python repositories. Arti-factsBench (Zhang et al., 2025a) assesses the ability to transform multimodal instructions into high-quality and interactive visual artifacts. SWE-Perf (He et al., 2025) and SWE-fficiency (Ma et al., 2025) benchmarks models on optimizing code performance in real-world repositories. KernelBench (Ouyang et al., 2025) evaluates model capability on writing efficient GPU kernels. We argue that all the evaluated abilities are equally important for coding agents, and the exceptional performance on a single benchmark is not indicative of a truly capable agent.

We provide a comprehensive review of these representative coding tasks and benchmarks in Table 5. (Yao et al., 2023), empowering agents with the ability to interact with the command line, edit files and browse the web based on a reasoning and acting loop.

OpenHands also provides securely isolated Docker sandboxes for all the actions to be executed, thereby ensuring a safe and consistent execution environment that prevents unintended changes to the host system. In our experiments, we use version 0.48.02 of OpenHands and disable the browsing tool and function call features.

Dataset Collection and Statistics. We employ an ensemble of Gemini 2.5 Pro (Comanici et al., 2025), GPT-4.1 (OpenAI, 2025a) and Claude Sonnet 4 (Anthropic, 2025a) for proposing projects. For proposing step-by-step tasks, we use GPT-4.1. All agents involved in our pipeline are implemented using OpenHands in conjunction with Claude Sonnet 4. We collect from 28 generated projects a total of 280 general trajectories (as detailed in Section 3.1 to Section 3.5) and 424 capability-specific trajectories (as detailed in Section 4), respectively 213 for issue resolution, 183 for issue reproduction and 28 for library generation, with Claude Sonnet 4. In experiments, we exclusively use the trajectories of finishing the task instead of those for generating the task. While the trajectories for unit test generation and issue injection could be valuable for training agents on specialized tasks such as generating unit tests from documentation, we do not include such benchmarks in our experiments, with the exception of SWT-Bench (Mündler et al., 2024), which requires agents to reproduce issues, but not to purely write unit tests. Therefore, we only adopt the trajectories that were are relevant to the capabilities evaluated in the benchmarks, namely, the trajectories of building up the project, fixing bugs and reproducing issues.

Training details. Following previous works (Pan et al., 2025;Jain et al., 2025b;Yang et al., 2025b), we select Qwen-2.5-Coder series (Hui et al., 2024), Qwen-2.5-Coder-7B-Instruct and Qwen-2.5-Coder-32B-Instruct, as our base models. We finetune the base model with all the trajectories mixed together and randomly shuffled, using a learning rate of 1e-5 and training for 3 epochs. Given that the length of our functionality implementation trajectories frequently exceeds the default maximum context length of 32,768 tokens, we follow the official instructions3 to extend context length using YaRN (Peng et al., 2024) during both training and inference stage. Following Jain et al. (2025b), we use LLaMA-Factory (Zheng et al., 2024) for efficient model finetuning, and adopt Zou et al. (2025) to further integrate sequence parallelism feature.

Benchmarks and Baselines. We select three distinct benchmarks to demonstrate the effectiveness of SWE-Playground: SWE-bench, SWT-Bench and Commit-0. SWE-bench (Jimenez et al., 2024) focuses on solving real GitHub issues. SWT-Bench (Mündler et al., 2024) evaluates agents on their ability to reproduce issues. Commit-0 (Zhao et al., 2024) tasks agents with building Python libraries from scratch. Collectively, these three benchmarks cover a wide range of critical coding capabilities, allowing for a comprehensive understanding on whether agents can handle various tasks. We adopt SWE-bench Verified (Chowdhury et al., 2024), SWT-Bench Lite and Commit-0 Lite as the evaluation splits for the respective benchmarks. We report resolved rate and empty patch rate for SWE-bench Verified, resolved rate and coverage delta for SWT-Bench Lite, and resolved rate for Commit-0 Lite. We select three strong baselines that focus on constructing coding environments and training SWE agents: SWE-Gym (Pan et al., 2025), R2E-Gym (Jain et al., 2025b) and SWE-smith (Yang et al., 2025b). Similar to our approach, SWE-Gym and R2E-Gym also build upon OpenHands, while SWE-smith is based on SWE-agent framework (Yang et al., 2024). We use vLLM (Kwon et al., 2023) to serve all the models for inference. We use OpenHands remote runtime (Neubig & Wang, 2024) to host docker containers during evaluation.

We provide our prompts used in our experiments for evaluating SWE-bench, SWT-Bench and Commit-0 with OpenHands framework as follows.

Prompt for SWE-bench Here is your task:

You need to complete the implementations for all functions (i.e., those with pass statements) and pass the unit tests.

Do not change the names of existing functions or classes, as they may be referenced from other code like unit tests, etc.

When you generate code, you must maintain the original formatting of the function stubs (such as whitespaces), otherwise we will not able to search/replace blocks for code modifications, and therefore you will receive a score of 0 for your generated code.

Here is the command to run the unit tests:

</test command> Make a local git commit for each agent step for all code changes. If there is not change in current step, do not make a commit.

We provide our full experimental results in Table 6. In addition to SWE-bench, SWT-Bench and Commit-0, we also evaluate models on BigCodeBench (Zhuo et al., 2024), a non-agentic benchmark which assesses models on programming challenges.

As the results show, all evaluated models demonstrate performance degradation against the base model on this benchmark, with SWE-smith-7B performing the worst with only a 6.08% success rate. This result validates that training with agentic trajectories inevitably comes at the cost of the capability on non-agentic static tasks. Firstly, models trained with agentic tasks typically adapt to the complex interactions and execution-based verification nature of agentic environments, and thus falter when facing static coding tasks. Secondly, agentic tasks such as SWE-bench are inherently different in format and capabilities evaluated from non-agentic tasks such as BigCodeBench, with the former focusing on context and project understanding, while the latter stressing algorithm design and instruction following. Furthermore, we hypothesize that this effect might be largely influenced by the design of the agent scaffold used during training.

We provide in this section the detailed prompts used for the SWE-Playground pipeline in our experiments.

System Prompt for Project Proposal

We are building a framework to train SWE agents to solve software engineering problems.

The plan is to propose projects and tasks for the agents to solve, collect task-solving trajectories, and then use these trajectories to train the agents.

Right now, we are proposing multiple diverse projects for our agent to solve.

We would like to work on a diverse set of projects to train a generalist SWE-agent that is strong across a wide range of complex computational tasks. Each task you propose should require multiple phases, 10+ distinct tasks, diverse technologies, and real-world complexity -think of projects that would take a professional developer 2-4 weeks to complete with multiple milestones and deliverables.

You should propose diverse Python projects that are algorithmically complex and require substantial core logic implementation. Projects should involve implementing sophisticated algorithms, data structures, computational methods, or complex system architectures from scratch.

System Prompt for Task Proposal

We are building a framework to train SWE agents to solve software engineering problems.

The plan is to propose projects and tasks for the agents to solve, collect task-solving trajectories, and then use these trajectories to train the agents.

We are currently in the middle of the proposal stage. Particularly, a project proposer has already proposed a project idea. Now, it is your job to do the following:

Propose a sequence of tasks to solve for this project. The proposed tasks should form a closed loop, meaning it could be self-contained without requiring any external dependencies, such as calls to external APIs or services. All necessary components and resources should be included within the project itself to ensure full autonomy and reproducibility.

Create a comprehensive task instruction document following this exact format: Make sure that the total number of phases should not exceed five. Focus on implementation tasks only -do not include documentation, deployment, evaluation, performance optimization (unless the project itself requires) etc. into the tasks. All phases should be dedicated to building the core functionality of the project.

Please follow the format of the exactly and avoid any extra information, as this file will be automatically parsed later in our pipeline. Remember to have all Phase, Module and Task present.

Please propose the tasks for the project: {{ project description }}.

Notice here are some constraints for the project: {{ constraints }} Format your output as: our response appears to be incomplete as it doesn’t have a closing </tasks>tag. Please continue generating tasks from exactly where you left off. Do not repeat any content from your previous response -just continue with the next task(s) and make

We are building a framework to train SWE agents to solve software engineering problems. The plan is to propose projects and tasks for the agents to solve, collect task-solving trajectories, and then use these trajectories to train the agents.

We are currently in the middle of the proposal stage. Particularly, a project proposer has already proposed a project idea and the tasks for this project has also been proposed in tasks.md. Project Description: {{ project description }} Notice here are some constraints for the project: {{ constraints }} Now, it is your job to do the following:

- Set up the basic repository structure for the project.

Create the initial project structure with the following components:

-Project Configuration Files: Set up appropriate configuration files based on the project type: -For Python projects: requirements.txt, setup.py, or pyproject.toml -For C++ projects: CMakeLists.txt, Makefile, or similar -For Rust projects: Cargo.toml -Directory Structure: Create the basic folder structure: -src/or app/for source code -tests/for test files -docs/for documentation -assets/for static resources (images, data files, etc.) -Initial Source Files: Create placeholder files to establish the project structure: -Main entry point (main.py, main.cpp, etc.) -Basic module structure -Initial test files

The repository should be immediately buildable and runnable, but you should not implement any anythings involved as tasks in task.md, which means your implemented setup must not pass any unit test.

You may create some directories and files, but do not write substantial content into them. The setup should only include the minimal structure needed to support the implementation of tasks. Also, unit tests should not be setup in this stage.

Notice that if you would like to initialize some classes and their functions, you should raise a NotImplementedErrorin each method body and do not provide any actual implementation, instead of simply leave a “pass”.

- Prepare Docker setup for the project.

-Modify Dockerfileand any other necessary files (such as .dockerignore) to enable containerized development of the project.

-Ensure the Docker setup installs all required build tools and dependencies for the project to compile and run, and most importantly for further development.

-The Docker container must be persistent for further development. Do not modify CMD ["tail","-f","/dev/nul"]is Dockerfile.

-For Python setup, you should create a new conda environment instead of directly installing all the packages. Therefore, use miniconda and environment.yml for setting up.

A template Dockerfile tailored to the project’s programming language has been provided in the repository. Please review and update this Dockerfile as needed to ensure it fully supports the specific requirements and dependencies of your project.

We are building a framework to train SWE agents to solve software engineering problems. The plan is to propose projects and tasks for the agents to solve, collect task-solving trajectories, and then use these trajectories to train the agents.

We are currently in the final of the proposal stage. Particularly, a project proposer has already proposed a project idea to tackle, and the documentation for the project has already been set up. Task: {{ project task }} Now, it is your job to create unit tests for the project based on the documentation:

For each Task X.Y.Z, a list of unit tests are contained in the documentation. Unit tests are put into two categories: Code Tests and Visual Tests.

For Code Tests, you need to write the actual unit test code that verifies the functionality described in the test description. These should be proper unit tests with assertions that check specific behaviors, inputs, and outputs.

For Visual Tests, you need to create simple test programs that call multimodal agents to provide visual verification of UI components, rendering outputs, and user interface behaviors that cannot be easily tested through code assertions alone.

Please create unit test files for each task that has unit tests defined in the documentation. Organize the tests logically and ensure they cover all the test cases mentioned in the task descriptions.

The unit tests should be written in the appropriate language for the project and follow standard testing conventions and frameworks.

Along with the unit tests functions you have written, a bash script tests/X.Y.Z.shis needed. All unit tests will be finally executed via this bash script. Each bash script should:

- Set up the necessary environment (compile the project if needed) 2. Run the specific unit tests for that task 3. Handle both code tests and visual tests appropriately 4. Provide clear output indicating test results (pass/fail) 5. Exit with appropriate status codes (0 for success, non-zero for failure) For visual tests, the bash script should run the programs that invoke a multimodal agent to perform visual verification of the test outputs.

The scripts will be executed under root directory via bash ./tests/1.1.1.sh, and this bash script should run ./tests/test 1 1 1.pyvia pytest, which implements the unit test logic. So you should ensure that the scripts can be run in this way.

You do not need to install packages for unit tests. Also, if the tests run into cases such as Import Error or Not Implemented Error, you should treat it as a failure case instead of skipping it.

All Tasks should be covered by unit tests except those marked with N/A. You do not need to care about whether your unit tests need to import the implemented modules. You just need to be responsible for implementing unit tests, and the implementation of functions will be based on your unit tests. You shall not leave TODOs in unit tests.

We are generating unit tests task by task, and currently you need to implement: {{ unit test prompt }} Only work on generating code for this unit test and do not care about others and no documentation for unit tests is needed. You MUST NOT implement code except for unit tests.

Please note that your task is to generate unit tests that can verify the correctness of the code that others will implement. You should not make your unit tests pass with the current code implementation. You should also NEVER expect the raise of NotImplementedError in unit tests as this will encourage the behavior of leaving functions unfinished.

You should ensure the tests you implement correctly verify all the functions for different projects: -Mathematical tools: Unit tests should ensure numerical accuracy, handle edge cases like division by zero, infinity, and NaN values, test mathematical properties and invariants, and validate algorithm correctness across different input ranges -Language processors: Unit tests should verify parsing accuracy, tokenization correctness, syntax validation, error handling for malformed input, and proper handling of different language constructs and edge cases -Complex data structures: Database engines, distributed data structures should be tested for data integrity, concurrent access safety, performance characteristics, memory management, and correctness of complex operations like joins, transactions, and consistency guarantees -Advanced parsers: Unit tests should validate parsing of complex grammars, error recovery mechanisms, abstract syntax tree generation, semantic analysis correctness, and handling of ambiguous or malformed input -Network protocols: Unit tests should verify message serialization/deserialization, protocol state management, error handling for network failures, timeout behaviors, and compliance with protocol specifications -Optimization systems: Unit tests should test convergence properties, objective function evaluation, constraint satisfaction, performance benchmarks, and correctness of optimization algorithms across various problem instances Make sure that the functionality is thoroughly tested, rather than simply verifying that the output format matches expectations.

You are now given a project directory and required to finish the project task by task. You have finished all tasks before {{ task number }}. Now it’s your task to finish Task {{ task number }}.

/tests, and you can run via bash tests/{{ task number }}.sh. However, you should NEVER first read and run the unit tests when you start with the task. First directly read the source code and finish with the implementation without accessing the unit tests. During this process, you can write some your own test code or scripts to verify your implementation, but DO NOT read the content of the given tests. After you think you have finished your implementation, you can run and read the provided unit tests to further verify and also correct the issues of your implementation.

Passing all the tests of {{ task number }} and also all tests for previous tasks means you have finished this task. You MUST NOT modify any content under /tests. You also do not need to proceed to next tasks.

We are building a framework to train SWE agents to solve software engineering problems. The plan is to propose projects and tasks for the agents to solve, collect task-solving trajectories, and then use these trajectories to train the agents.

You are tasked with creating realistic software bugs/issues that will be injected into working code to generate training data for SWE agents. The current codebase is fully functional and passes all unit tests, but we need to introduce specific issues that agents can learn to fix. The validation function incorrectly handles empty string inputs. When an empty string is passed to validate input(), it should return False according to the specification, but the current condition checks ‘if not input’ which treats empty strings as invalid when they should be valid for this specific case. False, but according to the documentation and expected behavior, empty strings should be considered valid input for this validator. This worked in previous versions but seems to be broken now. The function appears to be treating empty strings the same as null/undefined values, which is incorrect according to the specification.

OpenHands Prompt for SWE-bench Issue Application You are given a project directory with working code and a specific issue that needs to be applied to the codebase.

Your task is to read the issue description and apply the described problem to the current working code. This means you should INTRODUCE the bug or issue described, causing the existing unit tests to fail. Identify where the issue should be applied based on the issue description 3. Make the necessary code changes to introduce the described issue/bug 4. The goal is to make the unit tests fail by introducing this specific issue 5. Run the unit tests of this task to ensure they no longer pass. DO NOT edit unit test files. 6. Keep changes minimal and focused on the specific issue described 7. Ensure the code still compiles/runs but with the intended bug/issue Important: You are introducing a problem into working code, not fixing it. The unit tests should fail after you apply this issue.

You are given a project directory with working code and a specific issue that needs to be applied to the codebase.

Your task is to read the issue description and apply the described problem to the current working code. Also, you should modify the test files so that the issue cannot be detected by the tests. This means you should INTRODUCE the bug or issue described, but still making that all the unit tests under ’tests/’ can pass by modifying the test scripts to remove the specific test functions related to this issue and also modify other functions is this issue will also cause them to fail. Identify where the issue should be applied based on the issue description 3. Make the necessary code changes to introduce the described issue/bug 4. The goal is to make the unit tests fail by introducing this specific issue 5. Run the unit tests of this task to ensure they no longer pass. DO NOT edit unit test files. 6. Keep changes minimal and focused on the specific issue described 7. Ensure the code still compiles/runs but with the intended bug/issue Important: You are introducing a problem into working code, not fixing it. Remember that you should remove the related test functions and keep test scripts pass.

Project Proposal for Project “version-control-system” Repo Name: version-control-system Programming Language: Python Project Description: Create a Git-like version control system with support for repositories, commits, branches, merging, and diff algorithms. Must implement object storage with SHA-1 hashing, three-way merge algorithm, conflict resolution, branch management, and repository compression. The system should handle binary files, large repositories (¿10MB), and maintain complete history integrity. CLI interface with commands for init, add, commit, branch, merge, log, diff, and status operations matching Git’s interface.

Cannot use existing VCS libraries (e.g., GitPython, dulwich). Must implement all version control algorithms, diff algorithms, and merge strategies from scratch without using version control frameworks. Only basic file system operations and hashing allowed.

Project Proposal for Project “filesystem-simulator” Repo Name: filesystem-simulator Programming Language: Python Project Description: Create a file system simulator supporting ext4-like features including inodes, directory structures, file allocation, journaling, and defragmentation. Must implement block allocation algorithms, metadata management, crash recovery, and file system consistency checks. The simulator should handle file systems up to 1GB size and support concurrent file operations. CLI interface for mounting/unmounting, file operations (create, read, write, delete), directory navigation, and file system maintenance commands.

Cannot use existing file system libraries or implementations. Must implement all file system algorithms, block management, and metadata structures from scratch without using file system frameworks. Only basic file I/O for the underlying storage file allowed.

Task Proposal for Project “filesystem-simulator” # Project Description A comprehensive computer algebra system (CAS) that implements symbolic mathematics, polynomial arithmetic, and calculus operations. The system supports expression parsing from LaTeX format, algebraic simplification, differentiation, integration, and equation solving. It includes matrix operations, linear algebra capabilities, and numerical methods for root finding. The system can solve systems of equations with 10+ variables and integrate complex functions symbolically, providing step-by-step solutions and numerical approximations.

Build a complete computer algebra system from scratch that can parse LaTeX mathematical expressions, perform symbolic computations, and provide detailed step-by-step solutions. The system should handle polynomial arithmetic, calculus operations, matrix computations, and solve complex mathematical problems including large systems of equations and symbolic integration. -Create a constant node (e.g., 4.2).

-Create an operator node (e.g., ‘+’, with appropriate left/right children).

-Create a function node (e.g., ‘sin’, with argument node(s)).

-Create a node with metadata (e.g., position, LaTeX source, type info). -Traverse a nested expression (e.g., ‘sin(xˆ2 + 1)’).

-Traverse a tree with mixed operators and function nodes. -Compare two trees with equivalent structure but different variable names or constant values (should not be equal).

-Compare trees with different structures but representing the same expression (if structural equality is required, should not be equal; if mathematical equivalence, specify behavior). -The simplification process does not mutate the original tree structure outside of constant folding.

-## Test Case 2: IdentitySimplification Purpose: Verify that simplification correctly applies algebraic identities to remove or reduce redundant operations (e.g., x + 0 → x, x * 1 → x, x -0 → x, x / 1 → x, etc.). ### Test Scenarios Normal/Happy Path: -Simplify addition and subtraction identities: x + 0, 0 + y, z -0 -Simplify multiplication and division identities: x * 1, 1 * y, z / 1 -Simplify power identities: xˆ1, xˆ0, 1ˆy -Simplify nested identities: (x + 0) * 1, (y -0) / 1 Edge Cases / Boundaries: -Simplify expressions with multiple nested identities: ((x + 0) * 1) + 0 -Simplify identity operations on constants: 0 + 0, 1 * 1, 0ˆ0 (should behave as specified by system conventions) -Identity operations on function outputs (e.g., sin(x) + 0, log(y) * 1) Error Handling / Exception Cases: -Simplify invalid power identities such as 0ˆ0 (should raise exception or handle per convention) -Division by one or subtraction of zero when sub-expressions are malformed (should not break simplification) ### Assertions -Simplified expressions match mathematically equivalent, minimal forms with redundant identities removed.

-Complex expressions simplify recursively (identities are collapsed wherever they appear).

-Special cases like xˆ0 yield 1, 0ˆx yields 0 for x ̸ = 0, etc., handled according to system conventions.

-Edge cases such as 0ˆ0 are handled as per system design (error or defined value).

-Original expressions are not mutated unless simplification is performed in-place by design. -Results should be checked for mathematical correctness and structural integrity (i.e., tree correctness is preserved after simplification).

-Error and exception propagation during simplification must be robust and informative.

files changed, 367 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-) create mode 100644 tests/test_1_1_1.py create mode 100644 tests/test_1_1_1.sh Unit Test Generation root@f8d0:/workspace# bash tests/test_1_1_1.sh collected 21 items tests/test_1_1_1.py::TestBlockDeviceCreation::test_ default_parameters FAILED E NotImplementedError: BlockDevice.init not implemented Some tests for Task 1.1.1 FAILED class BlockDevice: def init(self, file_pa th: str, total_size: int, block _size: int = 4096): TestBlockDeviceCreation Functionality Implementation Project Name: filesystem-simulator Content: Create a file system simulator supporting ext4-like features including inodes, directory structures, … Programming Language: Python Edge Case: Attempt to create a device with zero size or block size, or exceeding maximum size (should fail with error).Assert that writing to one block does not affect data in other blocks.

files changed, 367 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-) create mode 100644 tests/test_1_1_1.py create mode 100644 tests/test_1_1_1.sh Unit Test Generation root@f8d0:/workspace# bash tests/test_1_1_1.sh collected 21 items tests/test_1_1_1.py::TestBlockDeviceCreation::test_ default_parameters FAILED E NotImplementedError: BlockDevice.init not implemented Some tests for Task 1.1.1 FAILED class BlockDevice: def init(self, file_pa th: str, total_size: int, block _size: int = 4096): TestBlockDeviceCreation Functionality Implementation Project Name: filesystem-simulator Content: Create a file system simulator supporting ext4-like features including inodes, directory structures, … Programming Language: Python Edge Case: Attempt to create a device with zero size or block size, or exceeding maximum size (should fail with error).

Performance on SWE-bench Verified with four distinct trajectory compositions: pure general trajectories, pure issue resolution trajectories, general trajectories plus issue resolution trajectories, and full mixture of all collected trajectories.

Do not run the provided test files to verify your fix, as the issue can not be detected by the test files.

Do not run the provided test files to verify your fix, as the issue can not be detected by the test files.

INTERFACE REQUIREMENT: -Command-line interface only: All projects must be operated via CLI with command-line arguments, flags, and text-based output -**-Projects that can be completed with <100 lines of core logic -Vague or ambiguous project descriptions that don’t specify concrete requirements -Any projects requiring GUI, web interfaces, or visual components such as computer graphics related tasks -Any projects requiring non-textual elements such as images or files as input and output -Any projects aiming at some open-ended problems and implementation correctness cannot be easily evaluated GOOD PROJECT TYPES: -Language processors: Compilers, interpreters, code analyzers, DSL implementations -Complex data structures: Database engines, distributed data structures -Mathematical tools: Computer algebra systems, numerical computation libraries, statistical frameworks -Advanced parsers: Complex format processors, protocol implementations, data transformation engines -Network protocols: Custom communication protocols, distributed consensus algorithms -Optimization systems: Constraint solvers, scheduling algorithms, resource allocation engines Examples of appropriately complex project proposals with clear specifications:

We use OpenHands CodeAct Agent in our experiments.

https://github.com/All-Hands-AI/OpenHands/releases/tag/0.48.0

📸 Image Gallery