Evaluating Feature Dependent Noise in Preference-based Reinforcement Learning

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Evaluating Feature Dependent Noise in Preference-based Reinforcement Learning- ArXiv ID: 2601.01904

- Date: 2026-01-05

- Authors: Yuxuan Li, Harshith Reddy Kethireddy, Srijita Das

📝 Abstract

Learning from Preferences in Reinforcement Learning (PbRL) has gained attention recently, as it serves as a natural fit for complicated tasks where the reward function is not easily available. However, preferences often come with uncertainty and noise if they are not from perfect teachers. Much prior literature aimed to detect noise, but with limited types of noise and most being uniformly distributed with no connection to observations. In this work, we formalize the notion of targeted feature-dependent noise and propose several variants like trajectory feature noise, trajectory similarity noise, uncertainty-aware noise, and Language Model noise. We evaluate feature-dependent noise, where noise is correlated with certain features in complex continuous control tasks from DMControl and Meta-world. Our experiments show that in some feature-dependent noise settings, the state-of-the-art noise-robust PbRL method's learning performance is significantly deteriorated, while PbRL method with no explicit denoising can surprisingly outperform noise-robust PbRL in majority settings. We also find language model's noise exhibits similar characteristics to feature-dependent noise, thereby simulating realistic humans and call for further study in learning with feature-dependent noise robustly.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **Modeling Feature-Dependent Noise**: - Simple Explanation: When deciding on your favorite food, taste and price can be key features. Sometimes we get confused between these two, which may lead to errors in our choices. This study proposes a way to model such types of errors from non-expert teachers' feedback. - Intermediate Explanation: Preference-based Reinforcement Learning (PbRL) trains agents based on the feedback received from teachers. However, non-expert teachers might be confused about certain features, leading their feedback to contain noise. The research introduces methods for defining and modeling this feature-dependent noise. - Advanced Explanation: Feedback from non-expert teachers is critical in PbRL but can introduce noise due to confusion over specific state-action pairs. This study formalizes and models various types of feature-dependent noise to enhance agent learning performance.-

Modeling Non-Expert Teachers:

- Simple Explanation: When friends recommend food, their recommendations might vary based on personal taste or experience. The study categorizes non-expert teachers into different types and suggests methods for understanding their feedback patterns.

- Intermediate Explanation: Feedback from non-expert teachers affects agent learning in PbRL. These teachers can be confused about certain features. This research defines various types of non-expert teachers and models how their confusion impacts the feedback given to agents.

- Advanced Explanation: Non-expert teachers provide feedback based on experience and specific features, which may vary widely. The study categorizes these teachers into different types and analyzes their feedback patterns to improve agent learning performance.

-

Evaluating Noise Models:

- Simple Explanation: To ensure that recommended food tastes good, evaluating the reliability of recommendations is crucial. This research suggests methods for assessing the trustworthiness of non-expert teacher feedback.

- Intermediate Explanation: Improving agent learning in PbRL requires understanding and evaluating the impact of noise from non-expert teachers’ feedback. The study introduces ways to evaluate different types of feature-dependent noise.

- Advanced Explanation: Enhancing PbRL agent performance necessitates a thorough evaluation of the noise present in non-expert teacher feedback. This research evaluates various types of feature-dependent noise, providing methods to improve overall learning efficiency.

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

Deep Reinforcement Learning (RL) has been successful in recent times and has been deployed extensively in interesting applications covering chip design , water management systems , gaming companions and healthcare . Despite its success, specifying informative reward functions for RL remains challenging and they are usually defined by experts or RL developers. There is evidence in literature that reward functions designed by trial and error can often overfit to a specific RL algorithm or learning context and can significantly reduce the overall task metric performance. Proxy reward functions can also lead to unwanted phenomena like reward hacking .

An easier way to specify a reward function is by making it sparse; i.e., provide a reward of $`+1`$ when a task is completed and $`0`$ otherwise. Deep RL has been known to suffer from the well-known sample-inefficiency problem due to such sparse reward , thus making it hard for the agent to learn efficiently. In order to reduce the dependency on hand-crafted reward functions, Preference-based RL (PbRL) has been a popular teacher-in-the-loop paradigm where a reward function is learned from teacher provided binary preference over pairs of trajectory segments. The Deep RL agent uses the learned reward function to learn an optimal policy well aligned with the teacher’s task preference. While generally, these methods have been successful on complex continuous control tasks, they assume access to an oracle for preference labels, which is a limiting assumption.

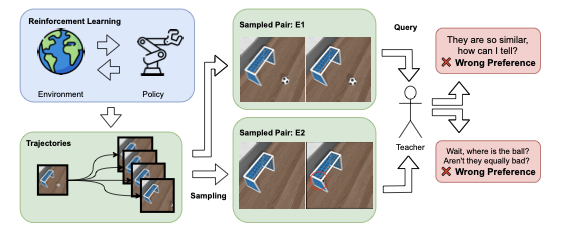

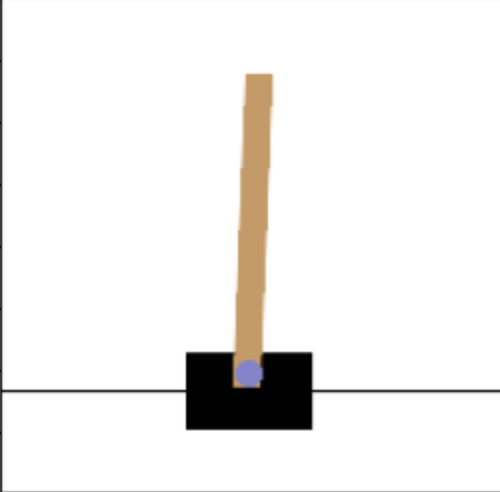

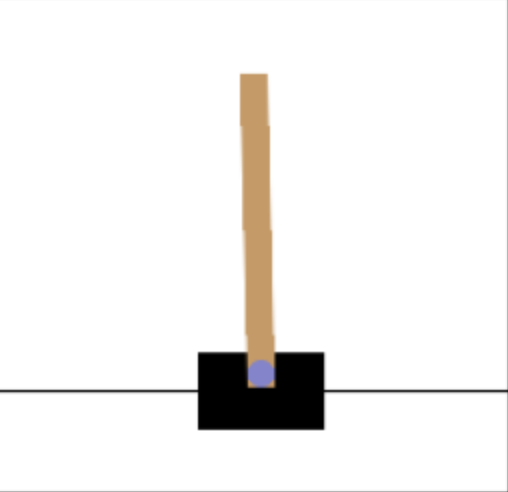

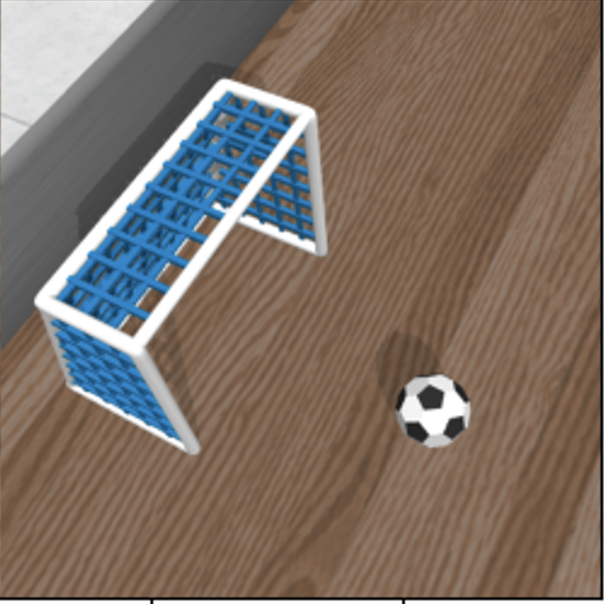

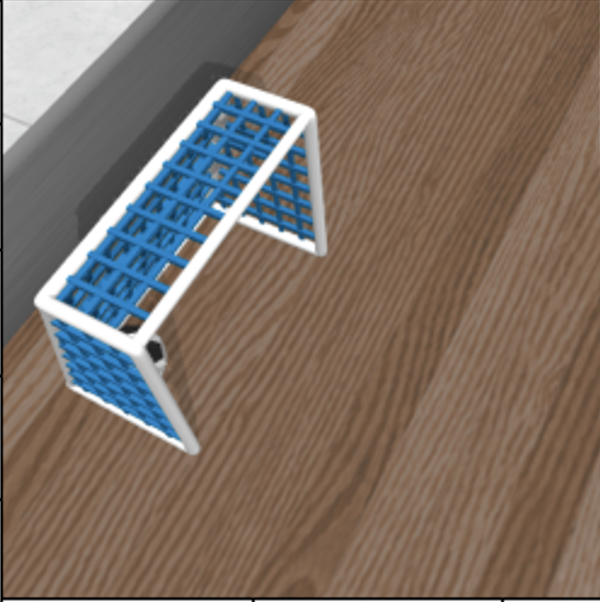

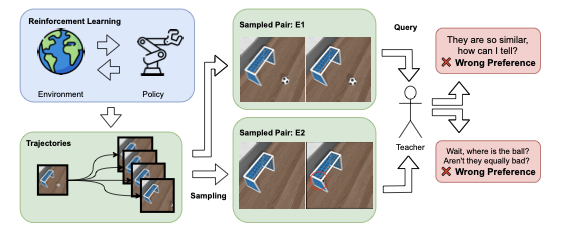

To address this limiting assumption of access to oracle for preference labels, Lee et al. introduced various kinds of teachers, including myopic and mistake-scripted teachers, trying to simulate human teachers prone to error. In this work, we formalise the idea of feature-dependent noise within the framework of preference-based RL motivated by different ways in which humans are prone to error while trying to give comparative feedback on pairs of trajectories. Let us take the example of Figure 1, where within PbRL, a human teacher encounters two similar trajectories as shown in example E1. It is hard for humans to provide comparative feedback on such trajectories, likely making them prone to error. Another analogous example, as shown in example E2, is when the two sampled trajectories have minute but non-trivial differences (the soccer ball in the figure is barely visible), thus making the teacher skip these important details and hence inducing noise in the preference labels. Prior work handles similar trajectory pairs by assigning a neutral preference. However, in practical settings, non-expert annotators may not reliably recognize such similarities, leading to inconsistent or noisy preference feedback.

In this work, we introduce several teacher models of feature-dependent noise, which provide practical ways of modelling preference from non-expert teachers. The intuition behind feature-dependent noise is that these noise models depend on specific feature subsets or representations and hence vary as a function of features. These kinds of noise functions arise from uncertainty in human judgment, which is systematically linked to the observable features of trajectories. As an example, if a human teacher induces noise over the preference label because of similarity between the trajectory pair, feature-dependent noise varies as a function of the similarity measure between the two trajectories, which means that the non-expert teacher makes more errors for similar trajectories and less for diverse trajectories. We also empirically evaluate the noise function of language models when they are employed as teachers inside PbRL to understand if they are behaviorally similar to feature-dependent noise.

In recent years, several state-of-the-art algorithms have proposed denoising mechanisms to identify and filter noisy preference data. In this work, we evaluate feature-dependent noise models using one such state-of-the-art approach. However, because feature-dependent noise is correlated with trajectory features, it is often challenging for these algorithms—designed primarily to handle uniform (feature-independent) noise—to detect such errors effectively. While uniform noise affects preference labels randomly, and is thus more easily identified by existing denoising methods, feature-dependent noise exhibits structured correlations that make it substantially harder to identify and filter, thus leading to poor agent performance.

Contributions of this work include (1) formalisation of feature-dependent noise within the PbRL framework, providing a foundation for structured, feature-correlated uncertainty in preference data, (2) introduction of multiple feature-dependent noise models that capture realistic, feature-driven inconsistencies arising from non-expert human feedback; and (3) evaluation of these noise models using several state-of-the-art PbRL algorithms to assess their impact on agent learning performance. (4) empirical analysis of LLM/VLM-based feedback using different qualities of these models, demonstrating that their induced noise functions exhibit strong similarities to feature-dependent noise. We introduce and systematically evaluate several feature-dependent noise models for existing PbRL algorithms, which form the main contribution of this work. Evaluations involving VLM-based PbRL are included solely to illustrate the similarity between advice generated by VLMs and feature-dependent noise, and is not the primary focus of this work. Extensive experiments on complex continuous control benchmarks from DMControl and Meta-world reveal that these noise functions remain difficult for existing denoising algorithms to detect, thus identifying the need for research in this direction.

Preliminaries

Reinforcement Learning: Reinforcement learning (RL) is represented

using a Markov Decision Process (MDP), which is a quintuple denoted by

$`M= ( \mathcal{S}, \mathcal{A}, \mathcal{P}, R, \gamma )`$, where

$`\mathcal{S}`$ denotes the agent’s state space, $`\mathcal{A}`$ is the

agent’s action space,

$`\mathcal{P}:\mathcal{S}\times \mathcal{A} \times \mathcal{S} \rightarrow [0,1]`$

is the environmental dynamics transition probability,

$`R: \mathcal{S} \times \mathcal{A} \times \mathcal{S} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}`$

is the reward function that outputs immediate reward, and $`\gamma`$ is

a discount factor. The agent’s goal is to learn a policy $`\pi(a|s)`$

which maximizes the discounted sum of rewards.

Preference-based RL: In Preference-based RL (PbRL) , the reward

function $`R`$ is trained from teacher preferences. Preferences are

binary signals between two trajectory segments, which provide

comparative feedback denoting which trajectory segment is favored over

another. Given a pair of trajectories,

$`\tau_1 = \{(s_t^1, a_t^1)\}_{t=0}^T`$ and

$`\tau_2 = \{(s_t^2, a_t^2)\}_{t=0}^T`$, the preference label

$`y \in \{1,0.5,0\}`$ denotes whether $`\tau_1 \succ \tau_2 (y=1)`$ ;

$`\tau_1 \prec \tau_2 (y=0)`$ or $`\tau_1 = \tau_2 (y=0.5)`$. The

primary goal in PbRL is to learn a reward model

$`\hat{R}_\theta(s, a)`$, parameterised by $`\theta`$, that is

consistent with preferences. This is done via modelling preferences

using the Bradley-Terry model as below:

\begin{equation*}

P_{\theta}(\tau_1 \succ \tau_2)=\frac{e^{\sum_t \hat{R}_\theta(s_t^1,a_t^1)}}{e^{\sum_t \hat{R}_\theta(s_t^0,a_t^0)

}+e^{\sum_t \hat{R}_\theta(s_t^1,a_t^1)}}

\end{equation*}where $`P(\tau_1 \succ \tau_2)`$ denotes the probability of preferring trajectory $`\tau_1`$ over $`\tau_2`$. Cross-entropy loss between the preference labels and the predicted labels is minimized to update the Reward function $`\hat{R}_\theta (s,a)`$ as below:

\begin{equation*}

L(\theta)=-\mathbb{E}[y\log P_\theta (\tau_1 \succ \tau_2)+(1-y)\log P_\theta (\tau_2 \succ \tau_1)]

\end{equation*}Feature Dependent Noise

In this work, we formalize feature-dependent noise (FDN) induced by a teacher in context to PbRL. We consider binary preferences (the ones that supply maximum information) and filter out equal preferences (y=0.5) as they pose no difference in training. Let $`Y`$ and $`Y^*`$ denote random variables for observed preference label and unobserved ground-truth label. We denote preferences as $`y \in \mathcal{Y}`$, which represents the annotators’ preferences towards a pair of feature subset $`\langle \mathbf{X}_1, \mathbf{X}_2 \rangle`$, where $`\mathbf{X}_1`$ and $`\mathbf{X}_2 \in \mathbb{P}(\mathbf{X})`$, i.e, $`\mathbf{X}_1`$ and $`\mathbf{X}_2`$ belongs to the power set of $`\mathbf{X}`$. For PbRL, the feature space $`\mathbf{X}`$ refers to a feature mapping $`\phi: \mathcal{T} \rightarrow \mathbb{P}(X)`$ over the states and actions in a trajectory space $`\mathcal{T}`$. Given an unobserved ground truth reward function $`R_o`$, the true trajectory reward over any trajectory $`\tau \in \mathcal{T}`$ is $`G(\tau)=\sum_{i=0}^T \gamma^{i}R_o(s_i,a_i,s_{i+1})`$. For each trajectory pair $`(\tau_1, \tau_2)`$ , we define an oracle teacher $`T_o`$ that gives ground truth preferences $`y^*`$ as below:

\begin{equation}

T_o(\tau_1 \succ \tau_2) = \sigma\left(G(\tau_1) - G(\tau_2)\right)

\end{equation}based on the ground truth reward function $`R_o`$. Here, $`\sigma(\cdot)`$ is the sigmoid function. Note that we can also make the oracle teacher deterministic using thresholding as below:

\begin{equation}

T_o(\tau_1 \succ \tau_2) =

\begin{cases}

1 & \text{if } G(\tau_1) > G(\tau_2) , \\

0 & \text{if } G(\tau_1) < G(\tau_2).

\end{cases}

\label{equ:deterministic_teacher}

\end{equation}To model a non-expert teacher $`T_{n}`$, we have a noise function $`N(\tau_1, \tau_2): \mathcal{T}^2\rightarrow [0,1]`$, representing the probability of mistakenly flipping a preference label given trajectory pair $`(\tau_1`$,$`\tau_2`$) and unobserved ground truth preference label $`y^*`$. Mathematically, the noise function $`N(\tau_1,\tau_2)=P(Y \neq Y^*|Y^*, \phi(\tau_1),\phi(\tau_2))`$ is defined over feature subsets corresponding to the trajectory pairs. The model of the non-expert teacher is represented as:

\begin{equation}

T_n(\tau_1 \succ \tau_2) = T_o(\tau_1 \succ \tau_2)(1-N(\tau_1, \tau_2)) + T_o(\tau_2 \succ \tau_1)N(\tau_1, \tau_2)

\end{equation}In the above equation, the first part represents the probability that the noisy teacher $`T_n`$ chooses the preference label correctly in accordance with the ground truth, and the second part denotes the probability that it chooses the trajectory ordering $`(\tau_1 \succ \tau_2)`$ incorrectly, opposite to the ground truth label. The assumption is that the noise function is symmetric so $`\forall \tau_1, \tau_2, N(\tau_1, \tau_2)=N(\tau_2, \tau_1)`$, and the teachers $`T_o`$ and $`T_n`$ are conditionally independent of each other. While this function can be a plain constant, i.e., $`N(\tau_1, \tau_2)=C`$, modelling uniform distribution noise, we focus on more complicated cases, where this probability depends on the feature space, giving us feature-dependent noise. We will elaborate on different types of feature-dependent noise in the following section.

style="width:100.0%" />

style="width:100.0%" />

Feature Dependent Noise Categories

In this section, we discuss various types of Feature-Dependent Noise.

Trajectory Similarity Noise The intuition behind this noise is that

if two trajectories are similar, the probability of inducing FDN by

teachers increases and vice-versa. In Trajectory Similarity Noise, the

feature is a pair of full trajectories $`x=(\tau_1, \tau_2)`$, and the

noise function would be

$`N(\tau_1,\tau_2) \sim \frac{1}{D(\phi(\tau_1),\phi(\tau_2))}`$, where

$`D`$ is a distance measure. In our settings, we consider the whole

trajectory so that $`\phi`$ is an identity mapping. An instance could

be,

$`N(\tau_1,\tau_2) = min(1, \frac{1}{||\phi(\tau_1)-\phi(\tau_2))||^2_2})`$,

where the probability of noise is proportional to the L2 distance

between two trajectories. Another way of computing D would be to use

encoders to compute distance in latent space, where

$`D =||\phi(Enc(\tau_1))-\phi(Enc(\tau_2))||^2_2`$; $`Enc(\tau)`$ refers

to the encoder function that outputs trajectory representation in

embedding space. In our experiments, for ease of controlling noise

proportion, we manually pick the threshold to ensure the desired amount

of noise.

Trajectory Feature Magnitude Noise: Human teachers often struggle to

reliably distinguish between trajectories when the differences are

concentrated in certain feature subsets that strongly affect perceived

stability. In particular, in domains such as HalfCheetah, large

variations in the torques applied across joints can cause the resulting

trajectories to appear visually unstable. This instability increases the

likelihood of label flips, thereby increasing the probability of FDN. In

this type of noise, the feature is a subset of the trajectory features.

These features are predefined from domain knowledge, where the teacher

lacks the ability to distinguish good or bad trajectory segments owing

to high variations (change in magnitude) of the feature subsets.

The feature is a pair of trajectories $`x = (\tau_1, \tau_2)`$ where

each trajectory is summarized by the time-averaged norm of its state or

action feature subsets. Here, the feature mapping $`\phi`$ maps to a

subset in the feature space $`\mathbf{X}`$. Let

$`\Delta = \lVert \phi(\tau_1) \rVert - \lVert \phi(\tau_2) \rVert`$,

where

$`\lVert \phi(\tau) \rVert = \tfrac{1}{T}\sum_{t=1}^{T}\lVert \phi(\tau)_t \rVert_2`$

denotes the mean norm over a feature subset as per the trajectory. The

noise function is defined as

\begin{equation}

N(\tau_1, \tau_2) = \sigma \left( \beta \, \log\!\big(1 + |\Delta|\big) \, \mathrm{sign}(\Delta) \right)

\label{eq:magnitude}

\end{equation}where $`\beta`$ is a scaling parameter. A Bernoulli sample from

$`N(\tau_1,\tau_2)`$ determines whether the preference label is flipped,

with an upper bound on the number of flips per batch. The sign function

incorporates the relative magnitudes of trajectory feature subsets, such

that $`N(\tau_1,\tau_2)`$ increases when one trajectory exhibits larger

feature magnitudes compared to the other.

Uncertainty-aware Noise: Human annotators are more likely to provide

unreliable feedback on comparisons where the reward model itself is

uncertain. Judgements that are deemed hard for the model are often hard

for teachers as well. So, injecting noise guided by an uncertainty

estimate (e.g., the difference between reward predictions) provides a

realistic simulation of preference corruption. In this type of FDN, the

feature subset corresponds to the predicted preference distribution from

an ensemble of reward models along with their observations and actions.

For each trajectory pair $`x = (\tau_1, \tau_2)`$, we compute the

difference between the predicted returns of the trajectory. Here, based

on the Bradley-Terry Model, the lower the difference, the higher the

uncertainty. Samples are then ranked according to their uncertainty

estimation, and the top $`\epsilon\%`$ most uncertain pairs are selected

for label flipping, where $`\epsilon`$ controls the desired noise level,

as shown in

Equation [equ:uncertainty]; $`threshold`$ is

decided by the top $`\epsilon\%`$ most uncertain pairs’ uncertainty

estimation and $`G_{\theta_t}`$ is the trajectory return given by the

reward model $`\hat{R}_{\theta_t}`$ at time step $`t`$.

\begin{equation}

N(\tau_1, \tau_2) =

\begin{cases}

1 & \text{if } |G_{\theta_t}(\tau_1) - G_{\theta_t}(\tau_2)| < threshold, \\

0 & \text{if } |G_{\theta_t}(\tau_1) - G_{\theta_t}(\tau_2)| \ge threshold.

\end{cases}

\label{equ:uncertainty}

\end{equation}Adversarial Noise: Adversarial Noise is developed specifically against RIME, a state-of-the-art noise-robust PbRL algorithm. RIME relies on KL divergence to detect noisy labels, where the KL divergence between noisy preference and predicted logits from the reward model is higher. We inject noise into samples that gives a low KL divergence between the prediction from the reward function and the incorrect preference that’s opposite to the ground truth. In other words, the noise is injected into labels and trajectories where it’s most likely to bypass RIME’s denoise mechanism by having a small KL divergence, as shown in Equation [equ:adversarial]. Here, $`T_{\theta_t}(\tau_1,\tau_2)`$ is the distribution of preferring each trajectory, given the current learnt reward function under the Bradley-Terry model, and $`T_w(\tau_1,\tau_2))`$ is the wrong teacher, which will always give the opposite prediction to the oracle teacher $`T_o`$. The $`threshold`$ is similarly determined by the top $`\epsilon\%`$ KL divergence candidates. Unlike uncertainty-aware noise, this type of noise is purely hypothetical, as it requires access to ground truth labels.

\begin{equation}

N(\tau_1, \tau_2) =

\begin{cases}

1 & \text{if } Div_{KL}(T_{\theta_t}(\tau_1,\tau_2)||T_w(\tau_1,\tau_2)) < \text{threshold}, \\

0 & \text{if } Div_{KL}(T_{\theta_t}(\tau_1,\tau_2)||T_w(\tau_1,\tau_2)) \ge \text{threshold}.

\end{cases}

\label{equ:adversarial}

\end{equation}Hybrid Noise: The intuition behind hybrid noise is that some samples may be ambiguous due to both behaviorally small differences (similar trajectories) or instability (high feature subset magnitude) and low model confidence (as indicated by similar returns). Hence, in this type of FDN, we combine the noise model of behavioral FDN with uncertainty-aware noise. Targeted behavioral noise in areas where the reward model is highly uncertain would result in an induced noise distribution correlated with the true preference distribution and hence make it difficult for the reward model to distinguish between preference ambiguity and preference annotation error. For each trajectory pair $`x = (\tau_1,\tau_2)`$, we compute a trajectory behavior-based score denoted by $`\text{score}_{\text{f}}(x)`$ and a model-uncertainty-based score denoted by $`\text{score}_{\text{u}}(x)`$ derived from uncertainty of the reward model. For $`\text{score}_{\text{f}}(x)`$, it can be any kind of other noise. For example, we can take trajectory distance as $`\text{score}_{\text{f}}(x)`$, giving a hybrid noise of trajectory similarity noise and uncertainty-aware noise. The total score for every trajectory pair is

\begin{equation*}

\text{score}(x) = \alpha \cdot \text{score}_{\text{f}}(x) + (1-\alpha)\cdot \text{score}_{\text{u}}(x),

\end{equation*}Here, $`\alpha \in [0,1]`$ is a weight coefficient that balances the

contribution of the feature-based score and the model-uncertainty score.

Here, if $`\alpha=0`$, then it gives uncertainty-aware noise and if

$`\alpha=1`$, it gives the feature-based noise.

Language Model Noise: In this type of noise, we employ an LLM or VLM

as a teacher for eliciting preference, as done in prior work like

RL-VLM-F and RL-SaLLM-F . LLMs are inherently known for providing noisy

advice by virtue of properties like hallucination . The judgments of

language models majorly rely on latent representations rather than true

reward signals. They are often biased towards salient or easily

perceived feature subsets rather than task-relevant dynamics; hence, the

induced noise is most likely to be an FDN. The goal here is to employ a

language model as a teacher to deduce if the noisy distribution induced

by these models is closer to FDN and hence difficult to detect by

existing denoising techniques in PbRL literature.

Experiments

The experiments are designed to answer the following research questions:

-

Can current state-of-the-art PbRL denoising methods effectively handle feature-dependent noise?

-

How do the proposed variants of feature dependent noise compare against each other within the PbRL framework?

-

Do LMs induce feature dependent noise?

-

Does the state-of-the-art denoising PbRL algorithm, RIME, consistently outperform algorithms without explicit denoising mechanisms under the proposed noise models?

Experiment Setup

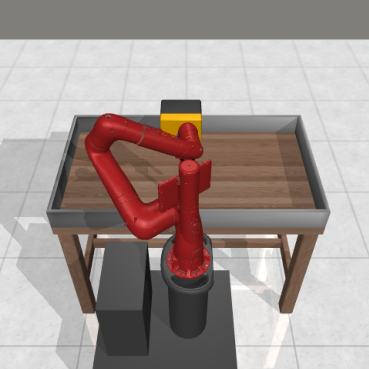

We follow the general experimental design from RIME , adapting it to study feature-dependent noise rather than only uniform noise. Specifically, we evaluate on three locomotion domains from DMControl : Walker, HalfCheetah, and Quadruped. These tasks provide diverse control dynamics and allow us to test noise sensitivity across environments. We also have experiments from Meta-World on Hammer, Sweep-Into and Button Press as reported in the Appendix Section 8. A scripted teacher provides pairwise trajectory preferences based on ground-truth episodic returns as Equation [equ:deterministic_teacher], which are then corrupted according to the noise models defined in Section 3.1. We inject noise rates of 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%, consistent with robustness studies in prior work.

For a fair comparison, we follow RIME’s preference-based RL setup. Walker and HalfCheetah uses $`1000`$ preference queries at every learning step and a reward batch size of $`100`$. Quadruped, being more challenging, uses $`4000`$ preference queries per learning step and a reward batch of $`400`$. For all the environments, we use unsupervised pre-training to pre-train the reward model as done in RIME. All results are averaged over 5 runs, and the mean episodic return and standard deviation are reported.1 We use RIME as a baseline, as it is the current state-of-the-art method in Pb-RL to detect and filter uniform random noise over preference labels. More details are shown in Appendix Section 7.

Results and analysis

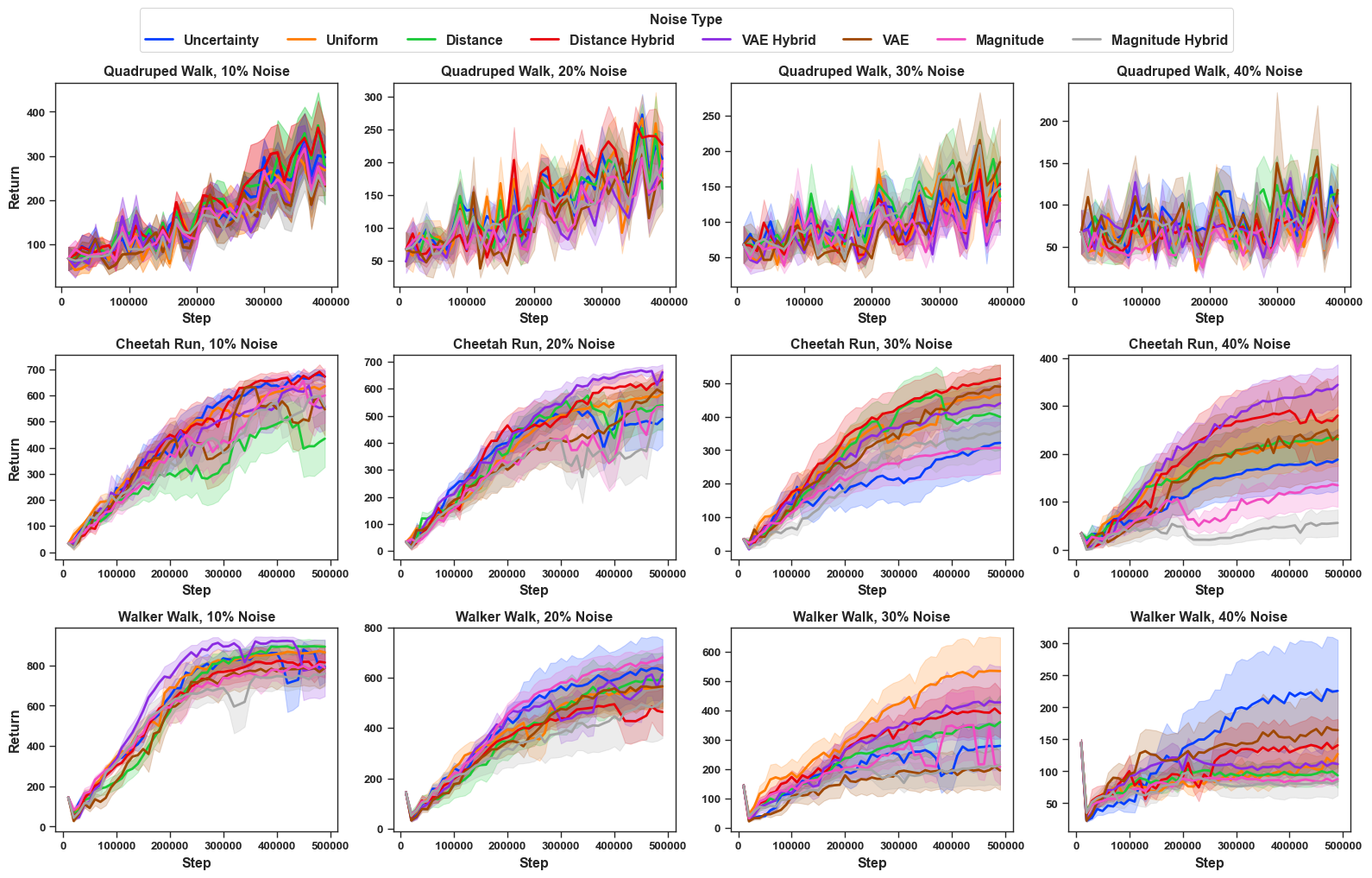

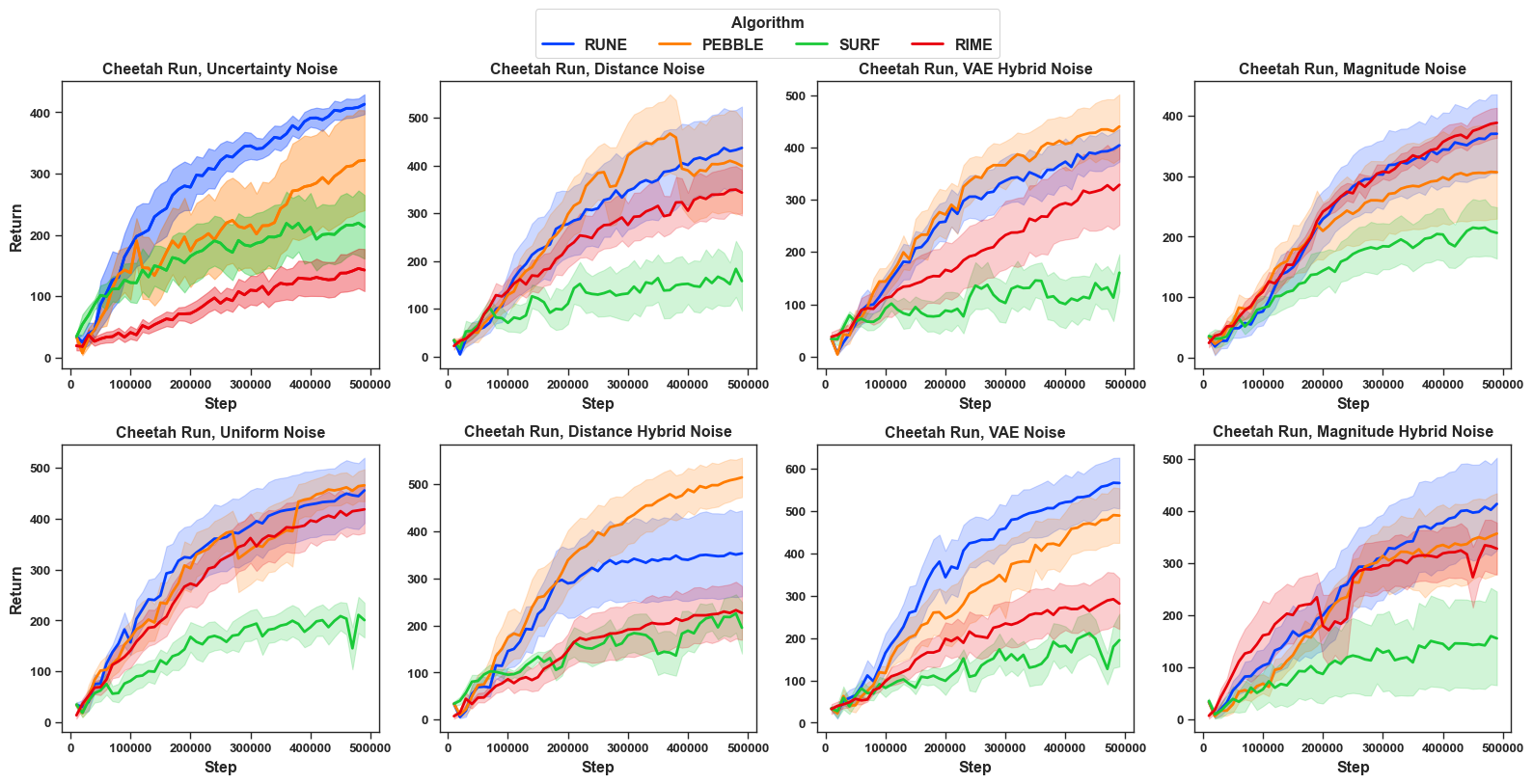

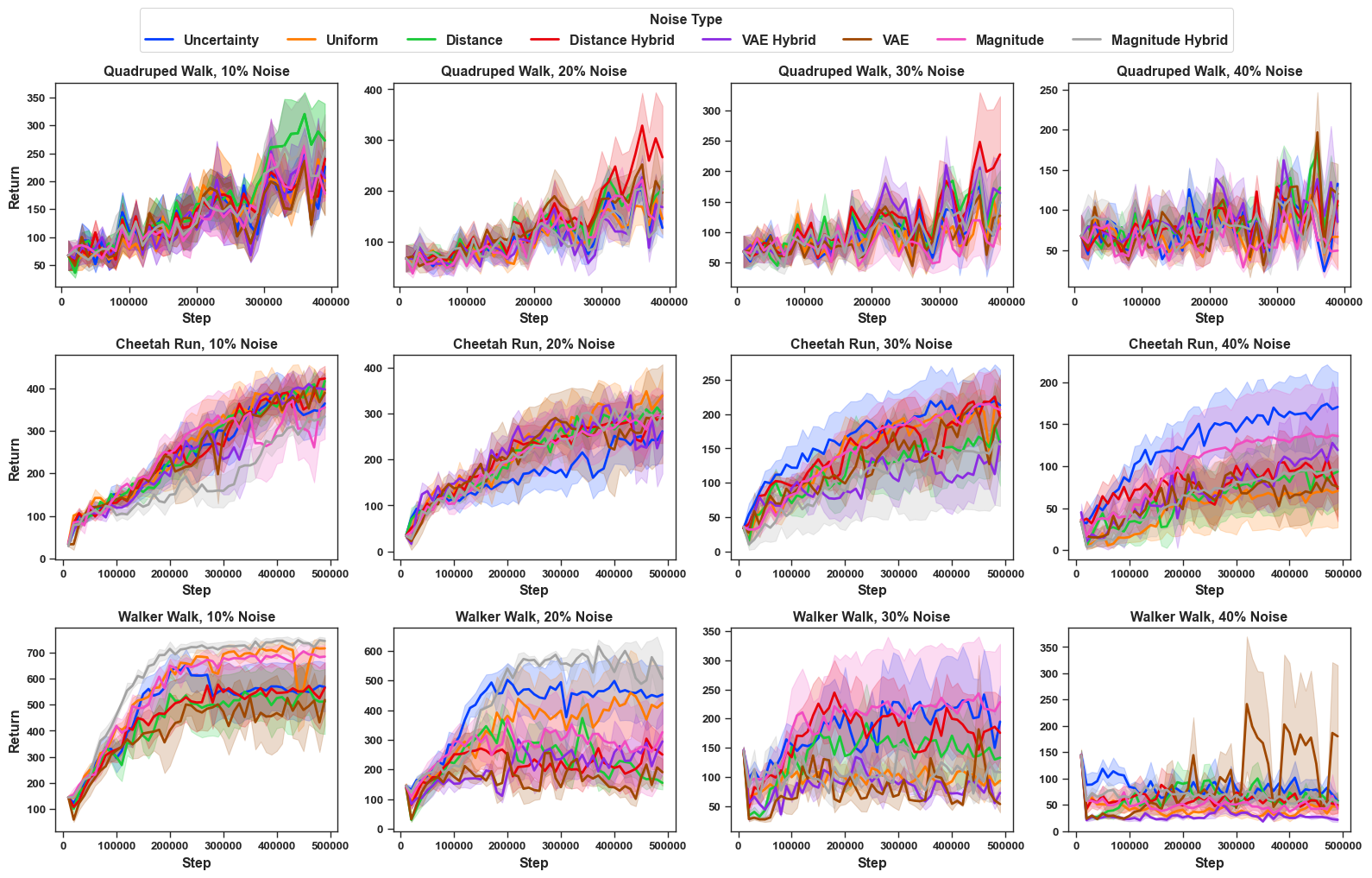

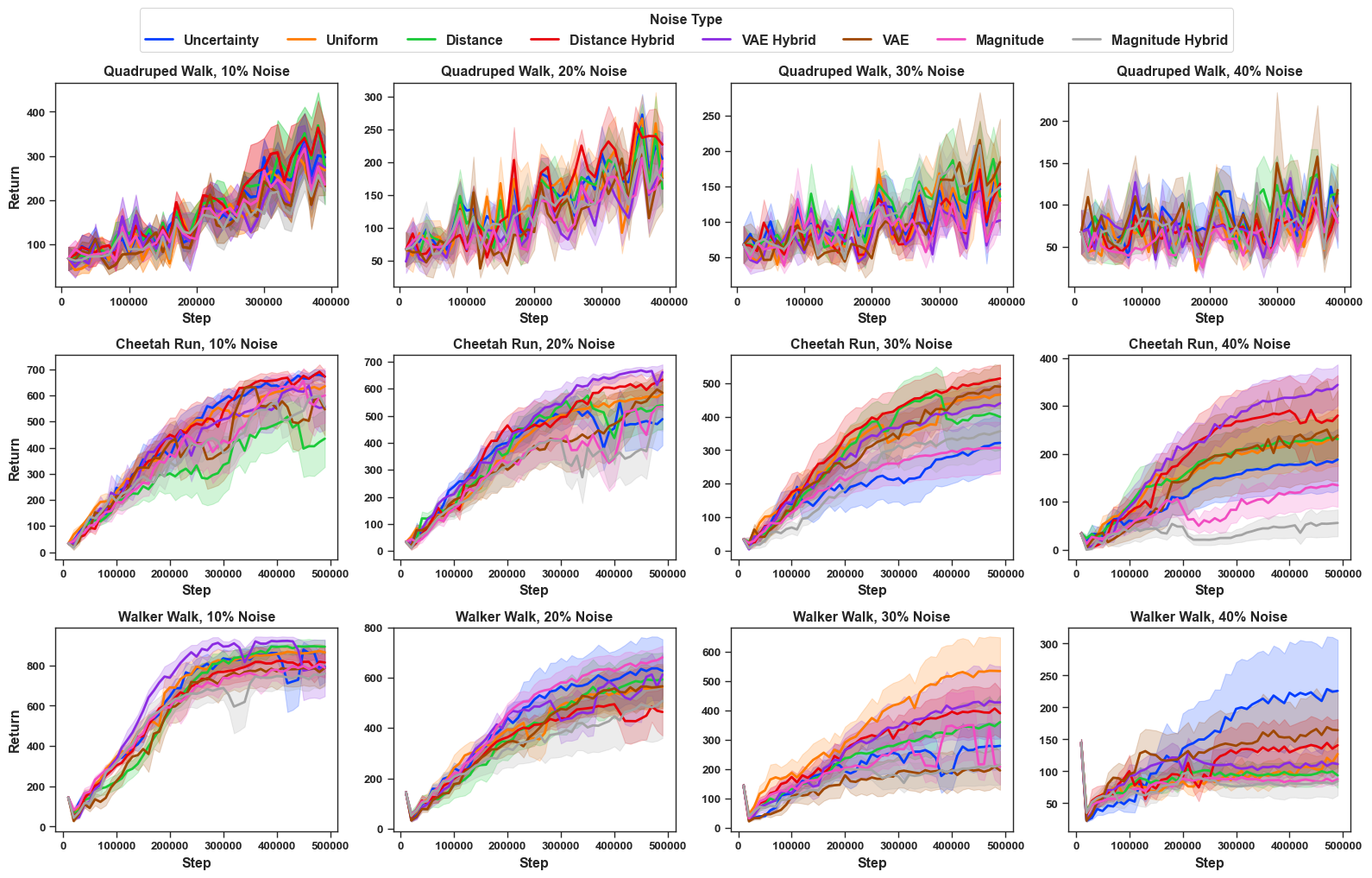

Trajectory Feature Magnitude Noise: This noise flips labels for trajectory pairs that show big differences in their action-level features. In this setup, we use the torque magnitudes from the action space of each domain to define the noise. The results are presented in Figure 3 as denoted by Magnitude (grey).

In Walker, Trajectory Feature Magnitude Noise is slightly easier to detect than Uniform noise at 10% with better agent performance than Uniform (orange line) and becomes increasingly easier to detect than Uniform at higher noise rates. In Half Cheetah, this noise is similar in performance to Uniform noise at 10-20% corruption but is harder to detect than Uniform noise at 30-40%. In Quadruped, this noise is harder to detect at 10% and easier to detect or comparable at higher noise levels. The effect of trajectory feature noise is domain- and noise-level-dependent and does not have a clear pattern. We hypothesize that the structure of this type of noise makes it easier to detect; RIME can easily recognize that all samples that have large torque values are noise and hence, are easier to detect than identifying a random noisy sample. This detection becomes even easier at higher noise levels due to the availability of more noisy samples.

Uncertainty Aware Noise: This noise represents the idea: what if the teacher happens to be erroneous, where the student is also underperforming? We simulate uncertainty-aware noise by injecting noise into trajectories where the reward function has the highest uncertainty, i.e., the predicted reward between two trajectories is very close to each other. This noise refers to value-based similar trajectories as seen from the lens of the reward model. The results are presented in Figure 3 as denoted by Uncertainty (blue). It can be seen that this noise is generally harder with lower learning performance in our domains as compared to Uniform noise is denoted by the orange line, except for Walker, and the agents tend to converge to a much lower episodic return, sometimes not learning at all (e.g: 30% noise on Half Cheetah). This suggests that the previous denoise algorithms are still challenged by this type of noise.

Trajectory Similarity Noise We tested the trajectory similarity noise with two distance metric: (1) L2 distance and (2) VAE embedding distance. In L2 distance, we take the L2 norm distance between the trajectory pairs. In the VAE embedding distance, we pretrain a VAE encoder to embed the trajectory into a much smaller vector representation, and then we take the L2 distance between the two embeddings. We use MLP and transformers as our encoders. The details of our encoder training and architecture can be found in Appendix Section [app:vae]. The learning curves under trajectory similarity noise can be found in Figure 3 as denoted by Distance and VAE. It is observed that the VAE can be significantly harder in comparison with Uniform Noise across domains. For example, VAE noise deteriorates the episodic return in all of our domains under most noise percentages, with Walker under 30% being an exception. L2 Distance, on the other hand, shows a trend to be easier to handle, and the policy still learns relatively well against up to 40% noise in Walker and Cheetah. One reason for this is that similar trajectories come with similar rewards, and wrong preferences over similar trajectories usually give smaller negative effects to reward function learning, while this might not hold for latent space representation.

Hybrid Noise Here, we combine two criteria: how uncertain the reward model is about a preference, and how similar or unstable the trajectories are under chosen features. The weight coefficient $`\alpha`$ is a hyperparameter to determine the contribution of individual noise functions. We study two types of hybrid noise:

-

Magnitude Hybrid Noise: targets pairs with large contrast in feature magnitudes when the model is also uncertain.

-

Similarity Hybrid Noise: targets pairs that look behaviorally alike (e.g., small distances in feature or embedding space) with high model uncertainty.

Magnitude Hybrid Noise: This noise reflects a challenging pattern,

as the teacher provides incorrect feedback on samples where the reward

function is uncertain and the teacher is erroneous due to behavioral

instability. The teacher makes mistakes in feature space, where the

reward model is most likely to get preferences wrong. Results for this

noise are shown in

Figure 3 denoted by Magnitude Hybrid

(green).

In HalfCheetah

(Figure 3a–d), Magnitude Hybrid Noise

performs almost the same as Uniform at 10–20% corruption ($`\alpha=0.9`$

at 10%, $`\alpha=0.3`$ at 20%) but shows stronger performance at higher

noise levels. At 30% ($`\alpha=0.3`$), the results demonstrate that

Magnitude Hybrid performs better than Uniform noise. At 40%

($`\alpha=0.1`$), the results show that the algorithm fails to learn

because aggressive flipping in ambiguous regions causes collapse, while

Uniform still retains some learning ability.

In Walker, Magnitude Hybrid demonstrates slightly better performance

than Uniform at 10–20% ($`\alpha=0.5`$ at 10% and 20%). At 30-40%

($`\alpha=0.7`$ at 30%, $`\alpha=0.9`$ at 40%), Magnitude Hybrid noise

performs significantly better, severely degrading agent performance by

targeting highly uncertain preference pairs. In Quadruped, the advantage

of Magnitude Hybrid (harder to detect and hence, lower performance)

emerges clearly at all noise levels ($`\alpha=0.9`$ at 10%,

$`\alpha=0.5`$ at 20% and 30%, $`\alpha=0.3`$ at 40%). Unlike Walker,

the superiority of this noise over Uniform remains consistent.

To summarize, Magnitude Hybrid noise on average is harder to detect than

pure Trajectory Feature Noise consistently in every domain.

Similarity Hybrid Noise: We also test Hybrid Noise from Uncertainty Aware Noise and trajectory similarity noise (both L2 and VAE). We take $`\alpha=0.5`$ for these experiments. As shown in Figure 3 denoted by Distance Hybrid(purple) and VAE Hybrid(brown), this fusion makes noise much more challenging to learn from compared to Uniform noise. With the increase in noise ratio, all types of noise become hard to tackle, and this effect is most significant in low-scale noises, as a high proportion of noise, regardless of the type of noise, generally flattens the learning curve. For example, under 10% noise, hybrid noise gives a lower episodic return in all three domains in comparison with Uniform noise. We also observe that the Distance Hybrid learning curve almost flattens under 40% noise in HalfCheetah, while the Distance noise itself in the same scale still allows satisfactory episodic reward, thus emphasizing the importance of behavioral noise in uncertain areas.

To summarise, we found several hybrid noises that pose a harder challenge to preference-based RL algorithms, and this effect is often more significant under low-scale noise of 10%, where the proposed FDN is harder to detect (lower agent performance) than uniform noise $`83\%`$ of the time across all domains in DMControl.2 Here to answer R1 and R2, the current state-of-the-art PbRL denoising methods cannot handle them effectively. In comparison with trajectory similarity noise or trajectory feature magnitude noise, hybrid noise often renders as the most challenging one to filter by RIME. Table [tab: episodic_return_all_noise] reports the final mean return for all noise levels across all domains, demonstrating that some variant of hybrid noise outperforms other variants approximately $`70\%`$ of the time, thereby supporting the claim.

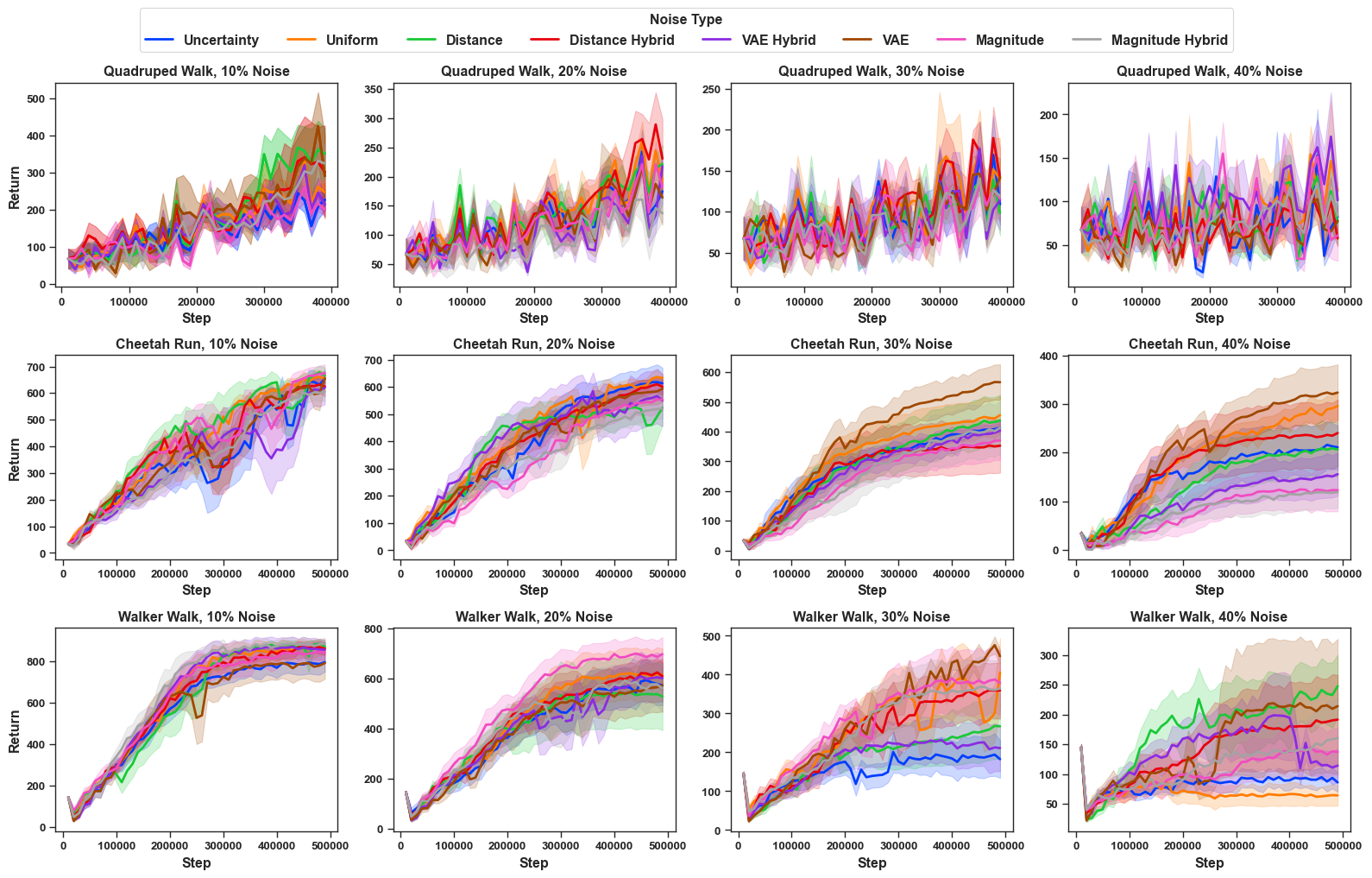

Adversarial Noise: While adversarial noise is injected to attack the KL-divergence-based denoising techniques with the knowledge of ground truth, it is found that this method, surprisingly, does not always work. The results are shown in Figure 3, denoted as Adversarial (yellow). For example, we see that in Walker, adversarial noise constantly gives a higher episodic return than Uniform noise, while in other domains, adversarial noise is generally much harder than Uniform Noise. This pattern is consistent with Uncertainty Aware Noise’s results, and it suggests that the current noise-robust PbRL methods can have domain bias in denoising ability. Here to answer our research questions, the adversarial noise shows a similar pattern3 with uncertainty-aware noise and is generally harder than uniform noise.

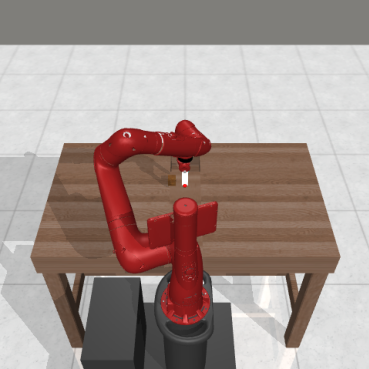

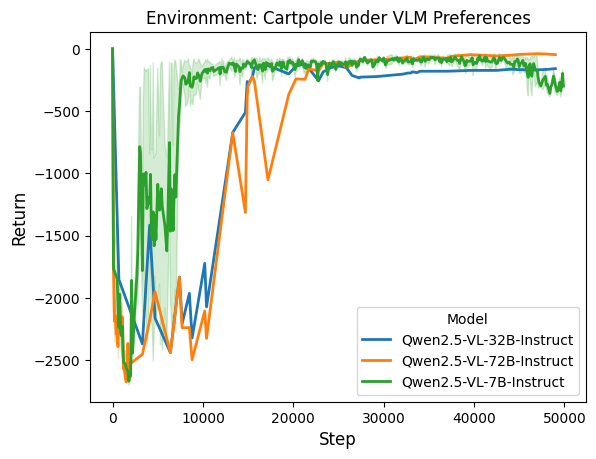

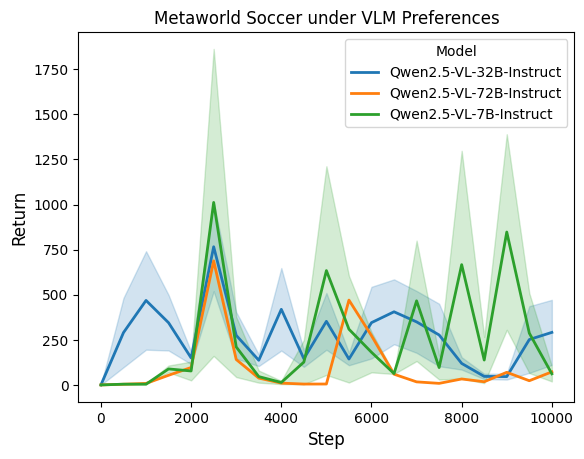

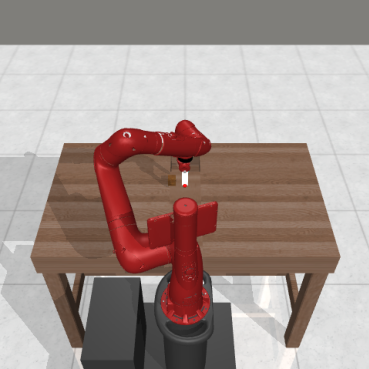

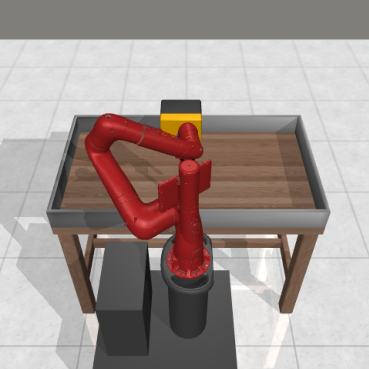

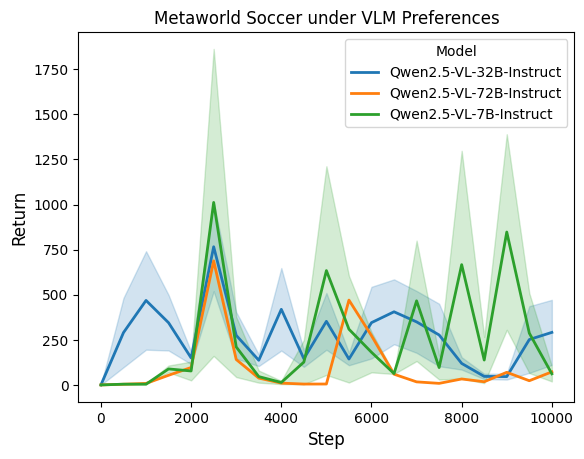

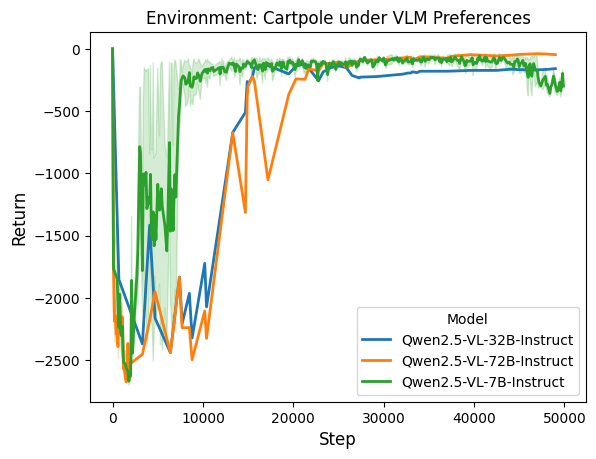

Language Model Noise: We tested with Qwen 2.5 VL series model, with model sizes of 7B, 32B and 72B, to provide preferences. We tested two visual domains, Cart Pole and Metaworld Soccer. We chose these two domains as they provide intuitive visual signals for preference feedback. In CartPole, the goal is to keep the rod vertical to the ground as much as possible, and therefore, the teacher may simply compare the angles of the rod to provide high-quality references. In Metaworld Soccer, the agent needs to control a robot arm to move the soccer into the gate, and the teacher can provide high-quality preferences by observing the distance between the soccer and the gate. The prompts we use to elicit preference follow similar settings in and can be seen in Appendix 9.

The results can be seen in Figure 6 and the corresponding noise can be seen in Table [tab:vlm_noise]4. We can find that in the Cart Pole, even the smallest model can achieve a high episodic return. Though with a rather small model like Qwen 2.5 VL 7B, the preference noise reaches as high as $`0.458`$, the agent is still able to learn against such a high level of noise, while in the same proportion of Uniform noise, we see the learned policy completely failed in the task. This is due to the fact that most errors in preferences are made in similar images. Examples of wrong preferences are presented in Appendix 9. As a result, the learned reward functions are still able to correctly penalise or encourage desired behaviour in most of the observations in Cart Pole. Another observation here is that the smaller VLM (Qwen2.5-7B) drives faster learning than stronger models, indicating that smaller, noisier teachers can still offer more effective feedback—aligning with the larger model’s paradox in literature.

We observed a similar pattern in Metaworld Soccer, where preference errors are often made in similar image observations. However, the Metaworld Soccer is a much more complicated domain that requires 3D understanding, and all of the models fail to provide high-quality preferences. For example, even the biggest model, Qwen 2.5 VL 72B, gives about 29.6% noise, and our smallest model, Qwen 2.5 VL 7B, almost gives random preferences. As a result, none of the models can guide the policy to solve the task, and at the same scales of uniform noise, similarly, all policies failed to complete the task. Furthermore, sometimes the soccer ball is almost blocked by the gate, and the VLM may not notice it, just like a human teacher. Here, to answer our research question R3, the VLM Noise is feature-dependent noise and consists of similar characteristics to trajectory similarity noise, as well as humans. Learning with this type of noise is challenging in complex high-dimensional domains like Meta-world Soccer as opposed to an easy domain like Cartpole.

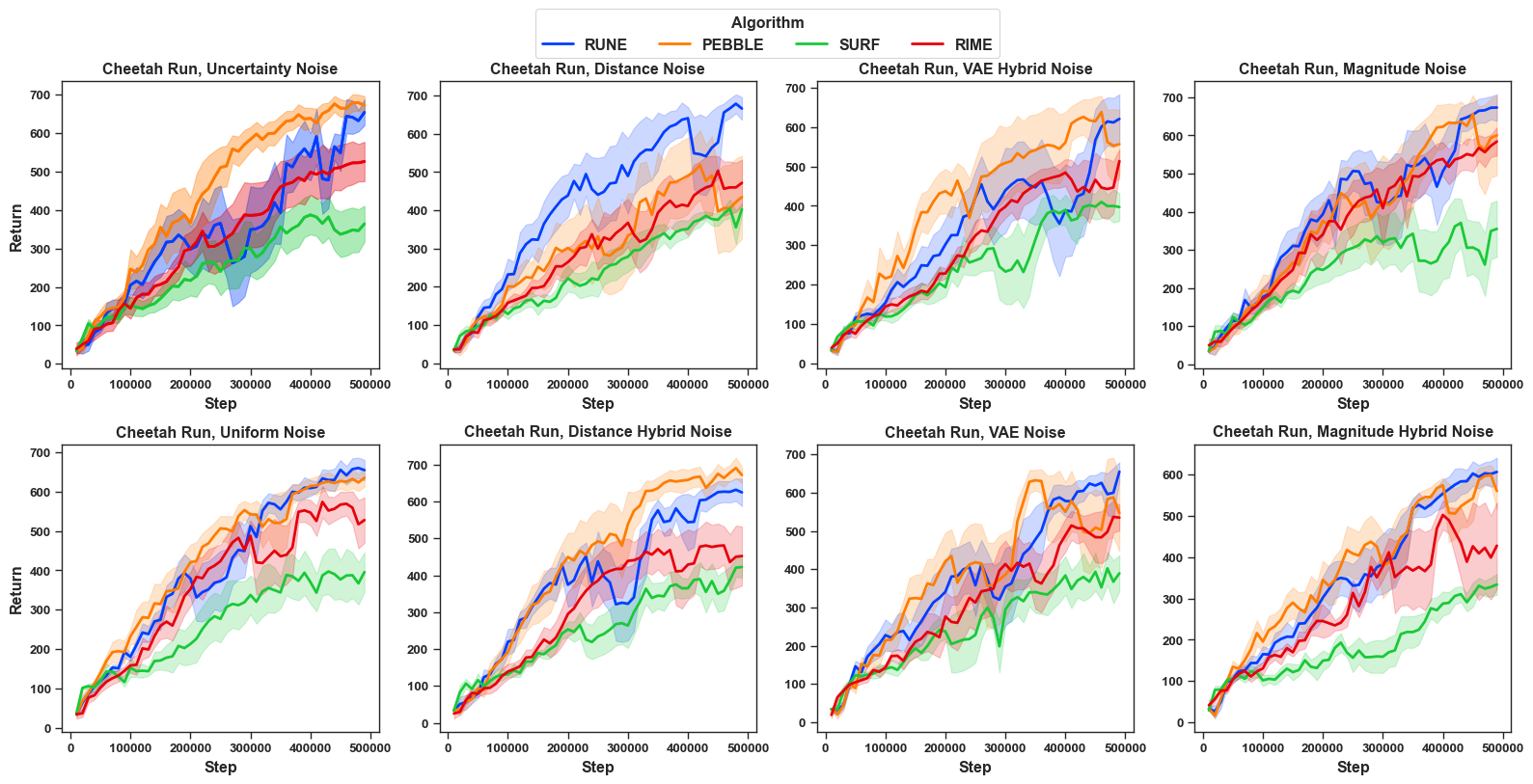

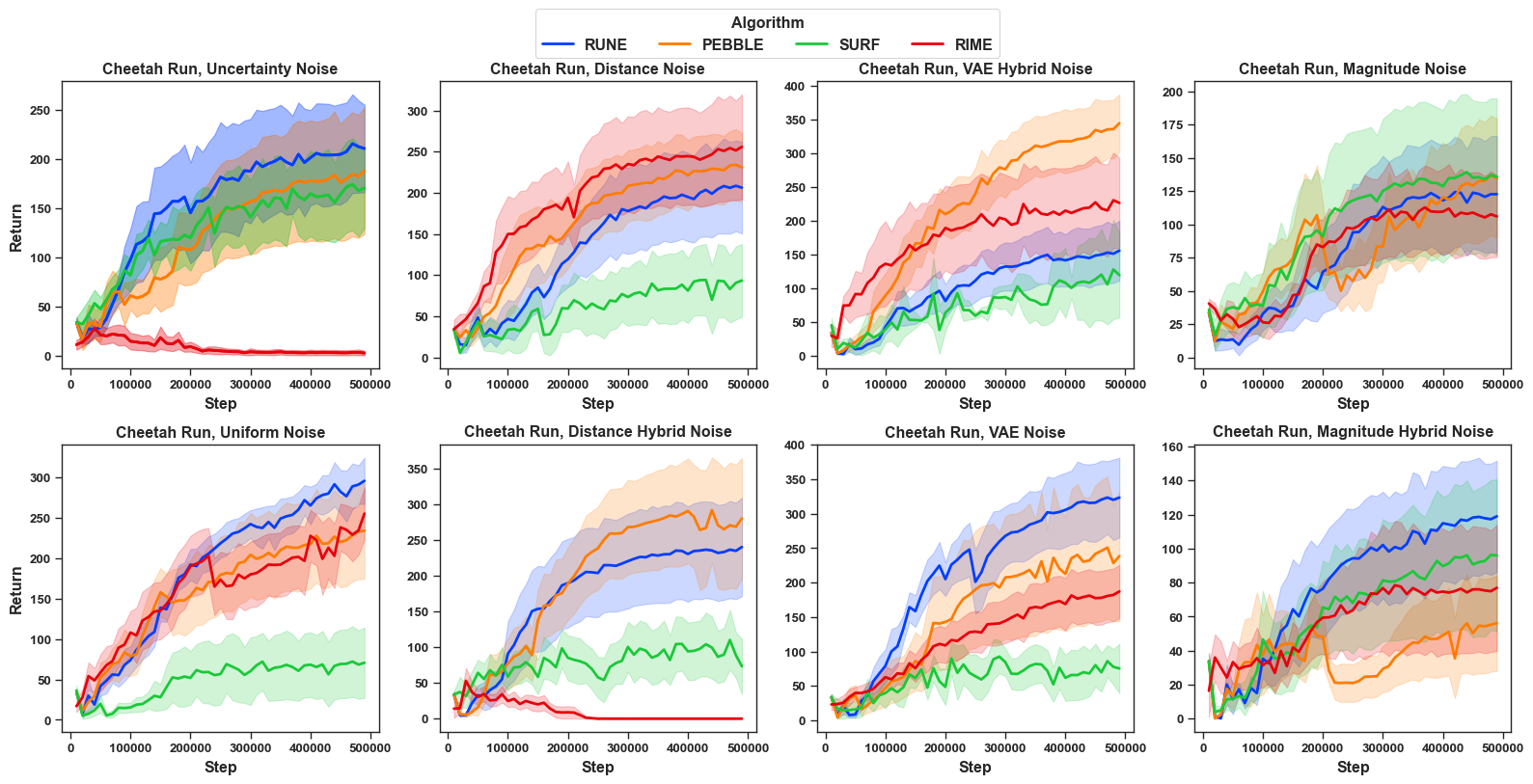

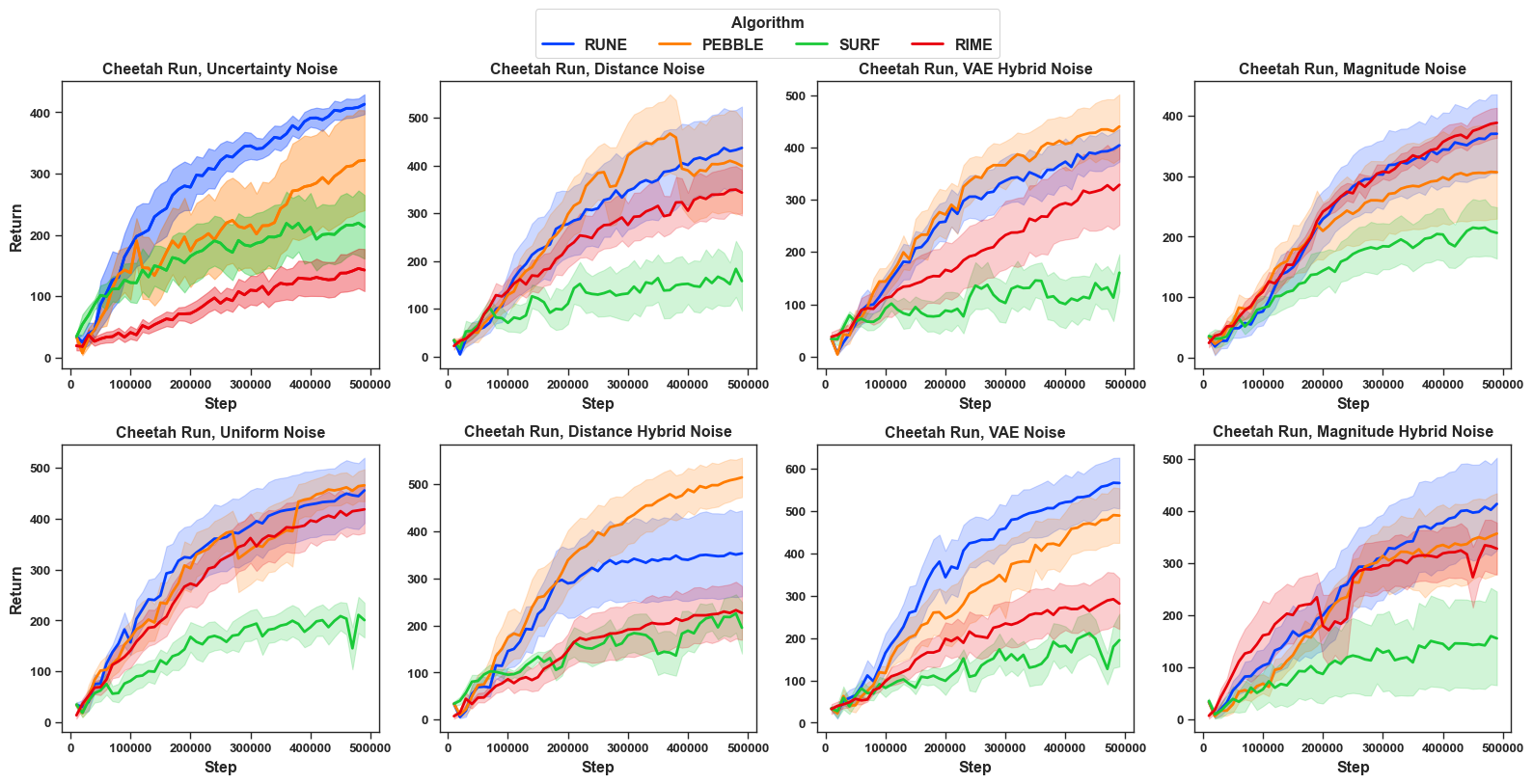

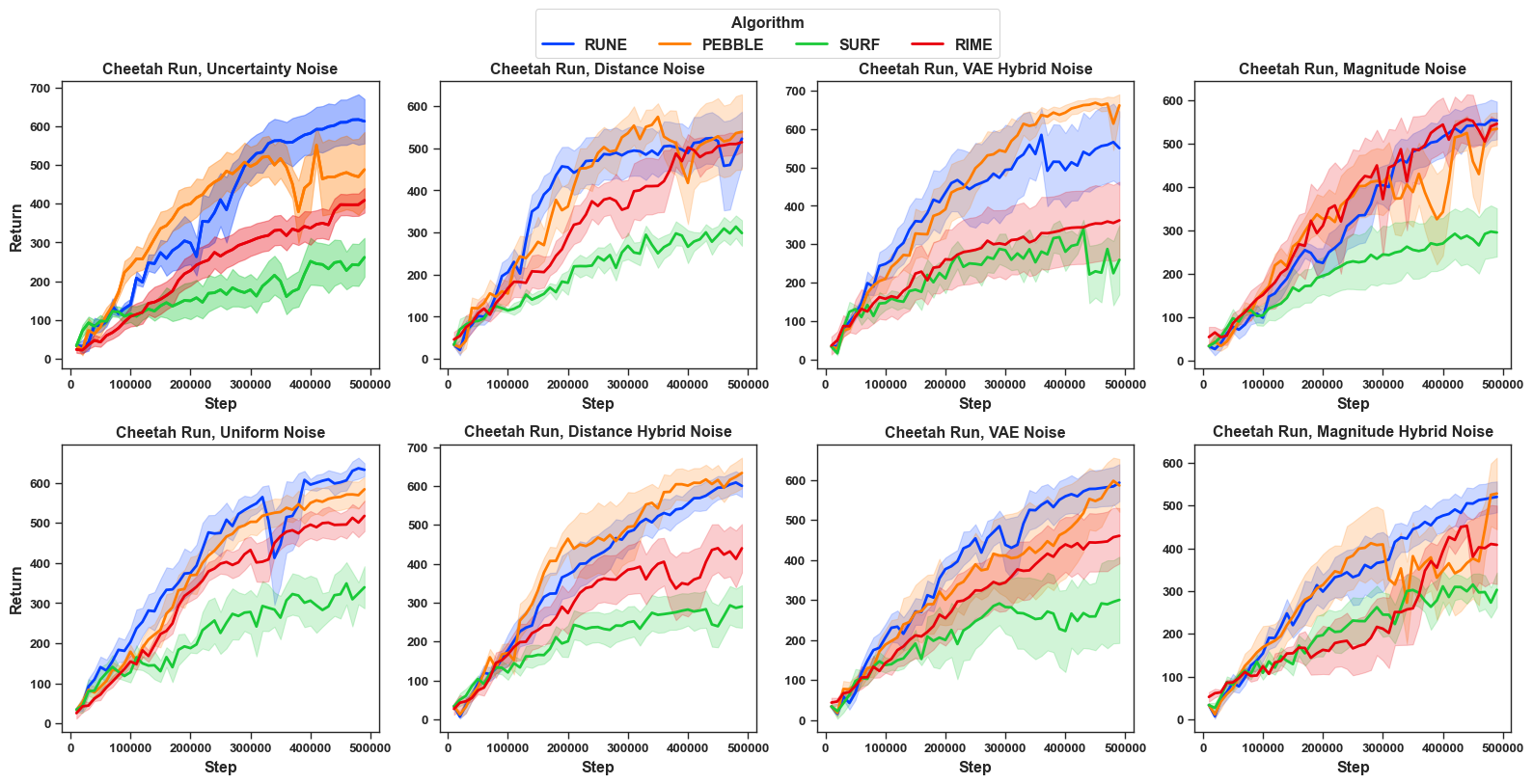

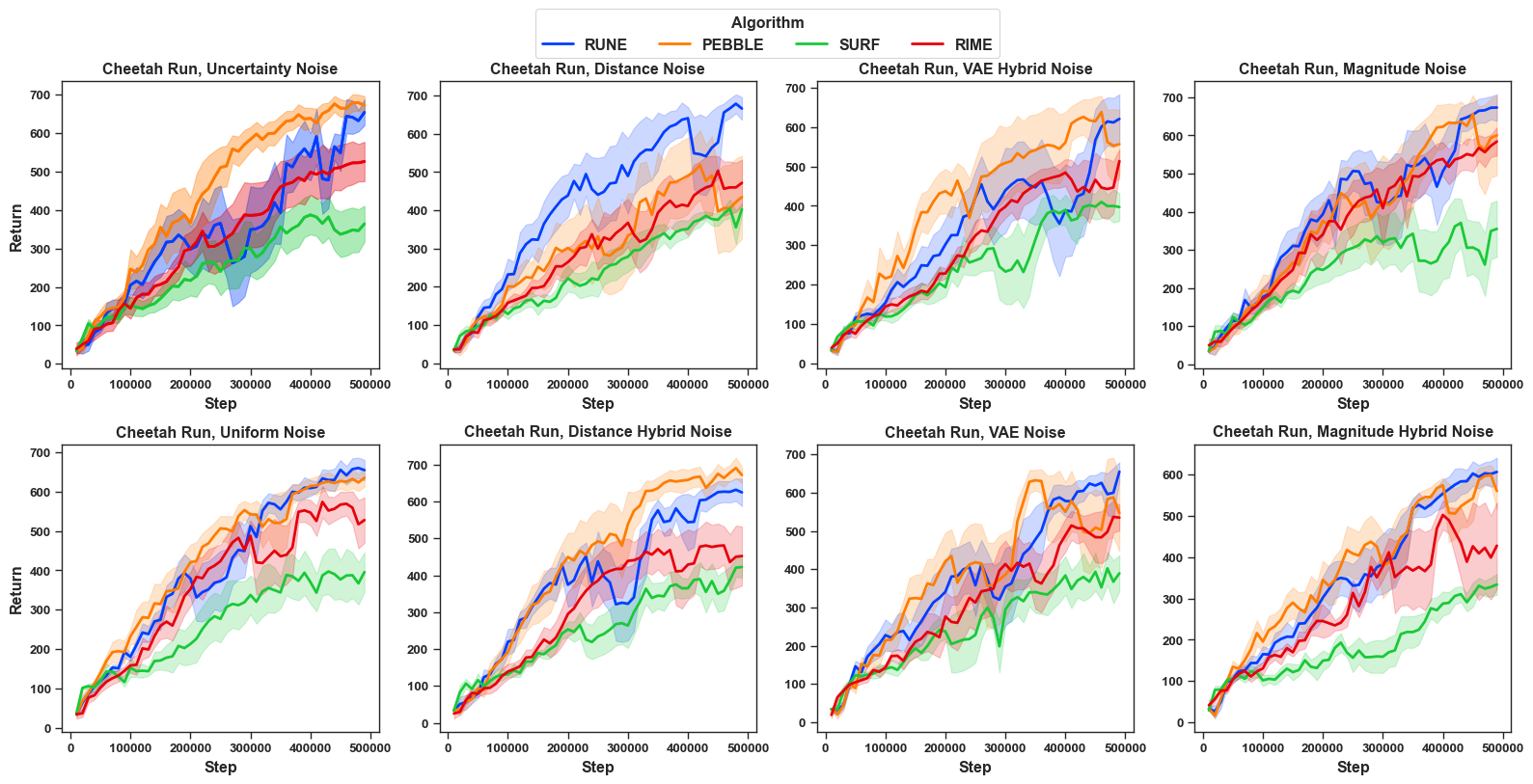

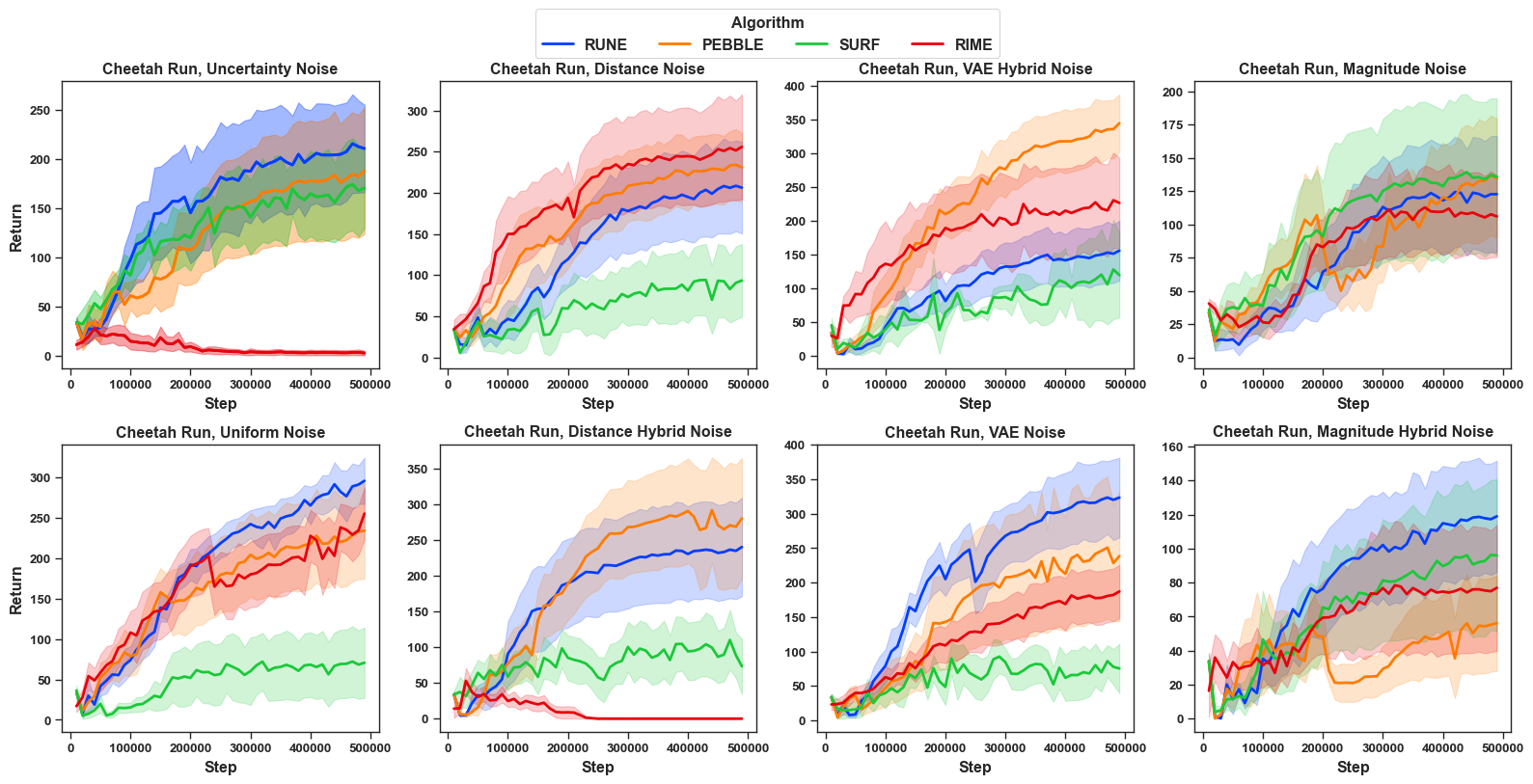

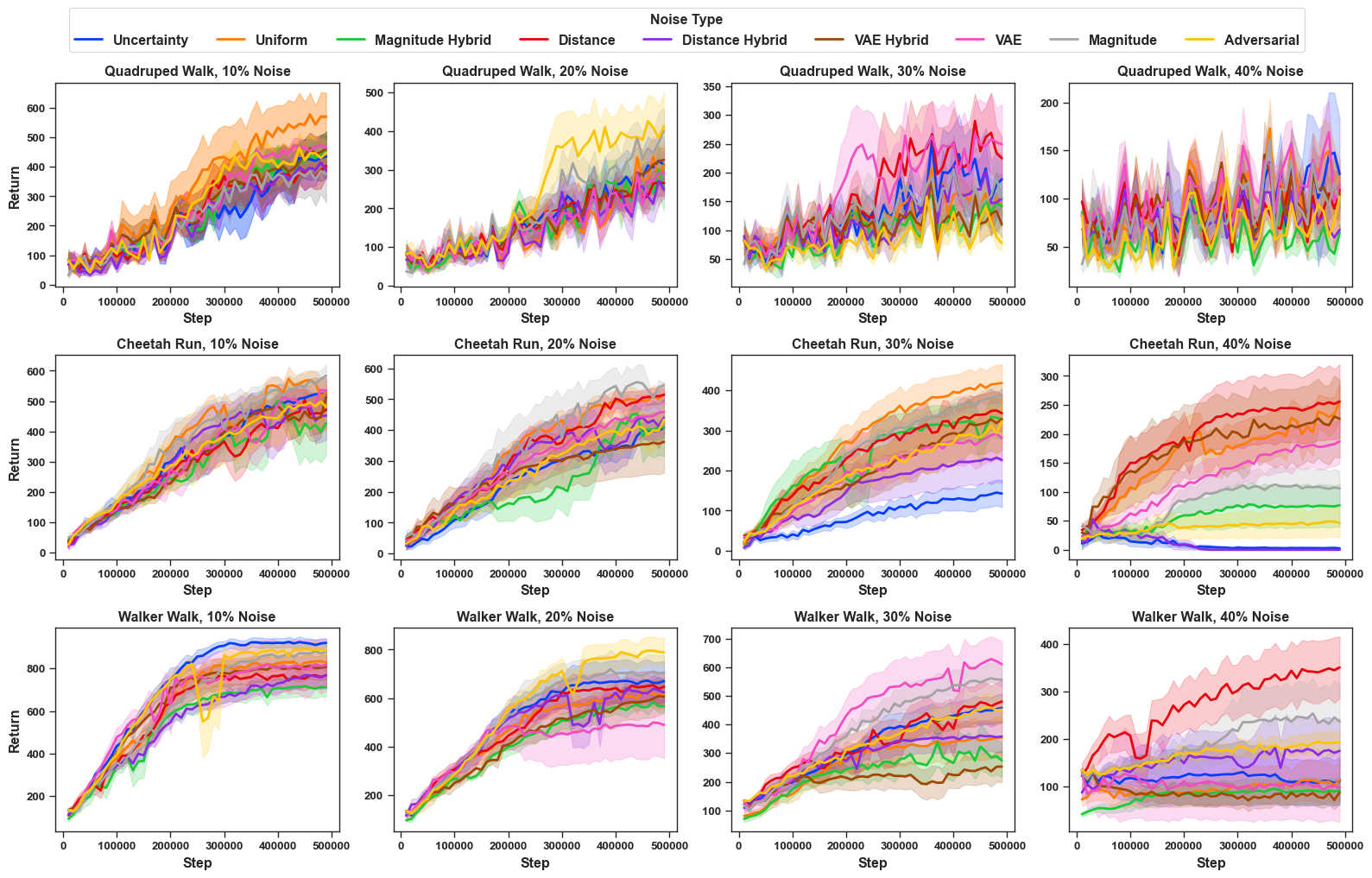

Different PbRL algorithms under FDN: To answer R4, we further benchmarked the learning performance of other PbRL algorithms that do not explicitly handle noisy preference, including PEBBLE , SURF and RUNE . We compare them under a fixed setting—Cheetah Run with different scales and all eight types of noise—as shown in Figure 7, with other results in Appendix Section 11 as in Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16. Overall, SURF (denoted in green) often performs worst among the four methods. A plausible explanation is that SURF augments preference labels using its learned reward model, which could amplify label errors when the teacher is imperfect. In contrast, RUNE tends to be the most stable. RIME shows substantial variability across noise types; for instance, under high distance-hybrid noise (30% and 40%), it can even perform worst as compared to other algorithms. We also observe in majority cases (94% cases in Cheetah run; 63% in Walker walk; 56% in quadruped) , RIME is not consistently the best in terms of performance. Therefore, we can non-affirmatively answer R4. This result further highlights the inherent difficulty of feature-dependent noise, where a denoising method may fail to generalize and can underperform as compared to other non-denoising methods. Additional results of individual comparison of PEBBLE, SURF and RUNE under different noise models can be found in Appendix ( Section 11).

Related work

Preference-based Reinforcement Learning: The motivation behind PbRL

is that reward functions are often manually engineered by trial and

error and not correlated to an actual task metric . Hence, this paradigm

does not require access to a reward function. Instead, a reward function

is learned from comparative feedback called preference over pairs of

trajectories from humans using the Bradley-Terry model . A recent

notable success is LLM fine-tuning, to align the LLM responses in

accordance with human preference. A state-of-the-art algorithm, PEBBLE

improves sample efficiency of PbRL by introducing unsupervised

pretraining followed by recent advances with respect to preference

annotation, query diversity, and sampling strategies.

Teacher models in PbRL: Most of the above-mentioned prior work,

including PEBBLE, assumes preferences from a perfectly scripted teacher,

which is not ideal. To alleviate this assumption, Lee at al. proposed

several models of simulating actual human behavior, including mistakes

and myopic scripted teachers. Moreover, they introduced an equally

preferable teacher with preferences sampled from a uniform distribution

$`(0.5,0.5)`$ if the two trajectory pairs are value-wise similar. They

also observed that a noise level of as small as $`10\%`$ led to poor

performance of the agent. Our work is inspired by Lee et al.’s work on

proposing realistic models of irrational teachers. However, we go beyond

these simple models and formalize complex noise functions to model

teacher errors within PbRL. There is also prior work that uses LLM/VLM

as a teacher to provide preference . However, LLM/VLM preferences rely

on strong models like GPT, and its noise’s influence on policy learning

within PbRL has not been explored.

Noise Robust Techniques in PbRL: In supervised learning literature,

identifying, filtering, and correcting noisy labels have been widely

studied with techniques like the small-loss trick , co-teaching among

peer networks and learning the noise transition matrix . Xue et al.

learned a reward function from inconsistent and diverse annotators by

using an encoder-decoder-based architecture in latent space and

computing reward uncertainty in that space. However, they used the

stochastic teacher model from Lee et al.’s work and focused on diverse

annotators but not on robustness against noise. Adapting the idea of the

small-loss trick, RIME proposed a denoising discriminator mechanism

where the trustworthy preference sample is identified as the ones with

low KL-divergence between the observed and the predicted preference

along with correction of noisy samples by flipping their labels. They

achieve superior agent performance with a noise level of up to $`30\%`$.

In another recent work , Huang et al. adapted co-teaching from

supervised learning literature between an ensemble of three reward

models to teach each other using identified clean samples showing

robustness against noise upto $`40\%`$; however, they had to utilize

demonstrations to mitigate the effects of noise. All of the

prior-mentioned noise-robust methods show good performance with the

uniform noise model; i.e., with a fixed probability, preference labels

are flipped in these settings. Though the idea of feature-dependent

noise exists within supervised literature , to the best of our

knowledge, we are the first to introduce the idea of feature-dependent

noise within the PbRL framework. We also select one of the current

state-of-the-art algorithms, RIME, to evaluate its impact on policy

learning. There has been some recent work to reduce the burden of

seeking preference queries from teachers on similar or indistinguishable

trajectories. These are likely strategies to explicitly reduce a

specific type of feature-dependent noise in our setting; however, these

works do not study the effects of noisy preference.

Conclusion

This work introduced models of irrational teachers within the Preference-based Reinforcement Learning (PbRL) framework by formalizing feature-dependent noise, where a teacher’s feedback depends on specific trajectory features. We proposed several such noise types—feature magnitude, feature similarity, and uncertainty noise—and evaluated them using a state-of-the-art denoising algorithm designed for uniform noise. Our results show that feature-dependent noise can be harder to detect due to its correlation with underlying features, highlighting the need for methods that can identify structured noise. Future work will explore denoising algorithms tailored to such noise and user studies to understand how often non-experts induce these biases.

Appendix

Implementation details

We adopted RIME as our test bed. Each environment is initialized with its corresponding MuJoCo configuration. The training system performs alternating operations between reward model updates and policy optimization. The replay buffer receives new labels from reward updates, which maintain the learned reward function in alignment with policy actions.

The agent uses intrinsic state-entropy rewards to build up the replay

buffer during the unsupervised pre-training phase (unsup_steps) before

the teacher preferences become available. The system selects feedback

samples through adaptive methods based on the chosen feed type, which

includes uniform, disagreement, entropy, or $`k`$-center, until it

exhausts the maximum feedback budget.

All experiments were executed on NVIDIA A40/L40S GPUs with CUDA acceleration. Each run was repeated across 5 random seeds for statistical stability, and the reported results correspond to the mean and standard deviation across seeds.

Experimental Settings of Hybrid Noise

For all experiments, we follow the RIME framework settings with

task-specific adjustments to stabilize training across different

domains. The number of unsupervised steps (unsup_steps) varies

slightly by environment, while other components remain constant.

Table 1 contains the set of $`\alpha`$

values that have been pointed out as the optimum values for all

experiments of Magnitude Hybrid Noise.

For Similarity Hybrid Noise, the optimum $`\alpha`$ value was 0.5 for

all scales of noise, indicating equal weighting in the scores of

Uncertainty Aware Noise and Trajectory Similarity Noise.

| DMControl Domain | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walker Walk | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| HalfCheetah Run | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Quadruped Walk | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

Optimum $`\alpha`$ values found for Magnitude Hybrid Noise after experimenting multiple cases with $`\alpha \in [0, 1]`$.

VAE Encoder Settings

We use VAE encoders in our VAE Encoding Distance Noise experiments. These encoders are trained on the collected trajectories on a previous normal run of Preference-Based Reinforcement Learning. For Cheetah, we train our encoders on an MLP neural network. For Quadruoped and Walker, where the observation dimension is higher and requires a stronger encoder, we choose a transformer structure. The hyperparameters are shown in Table [tab:vae_settings].

Results on More Domains

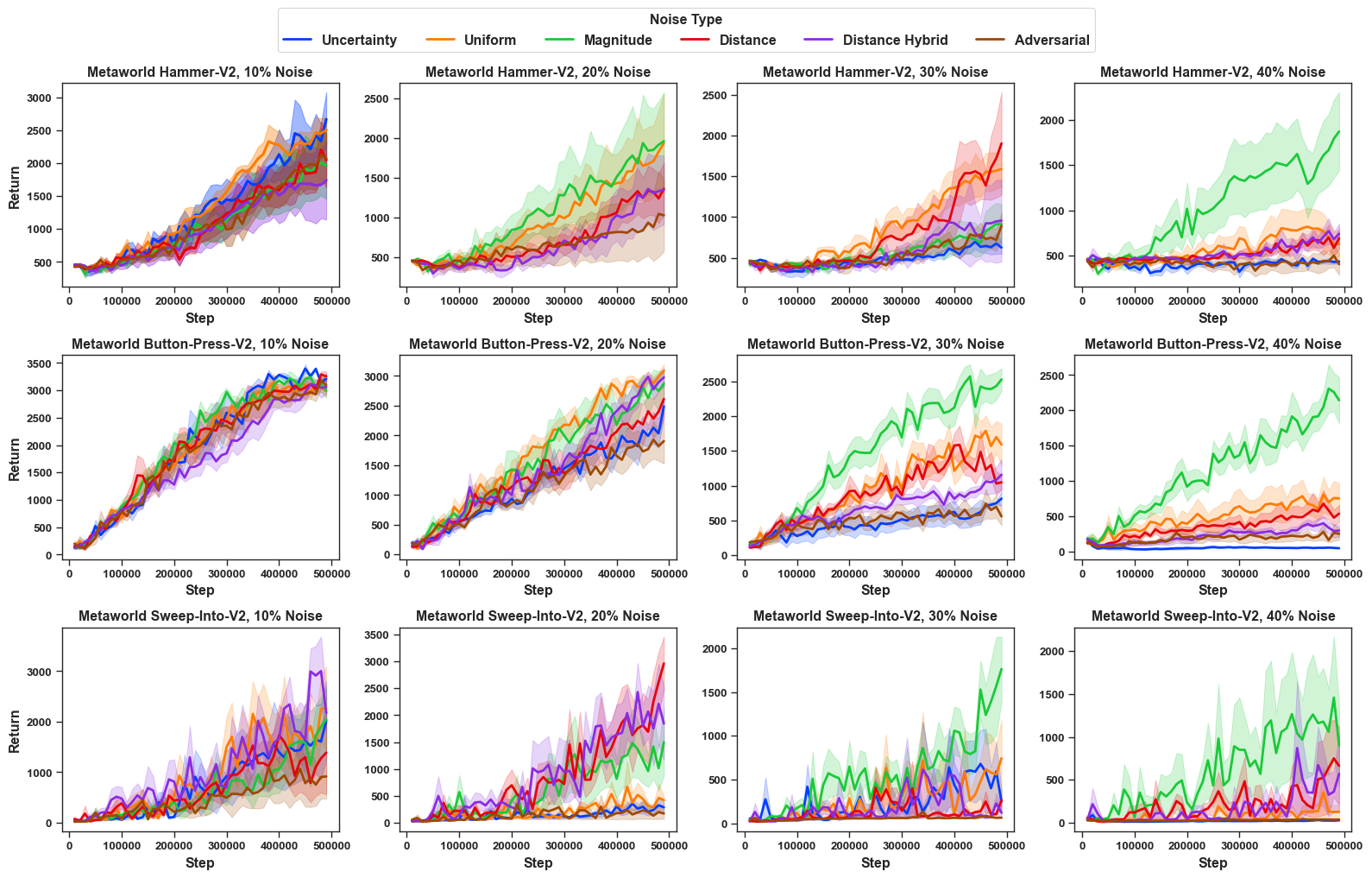

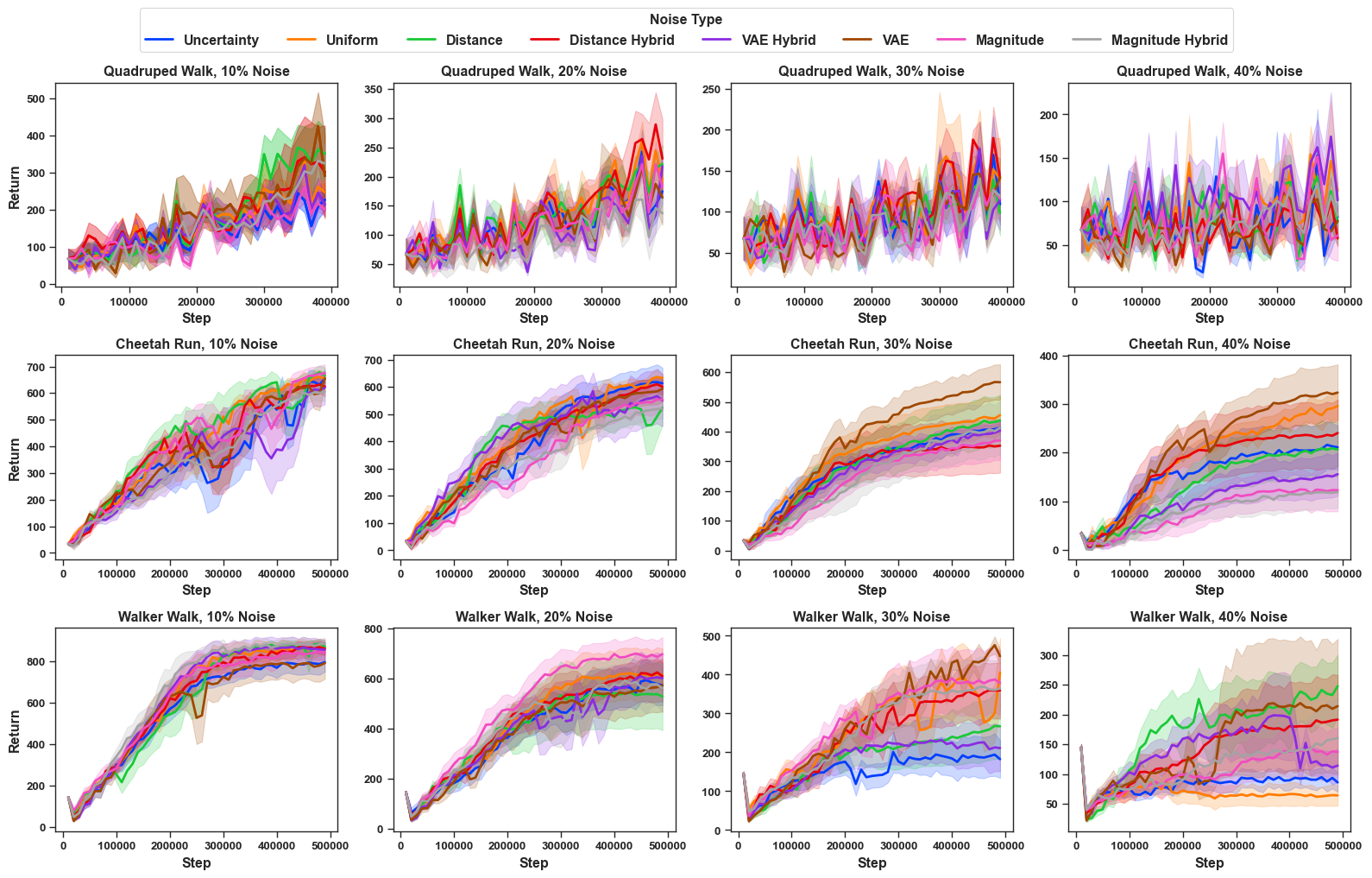

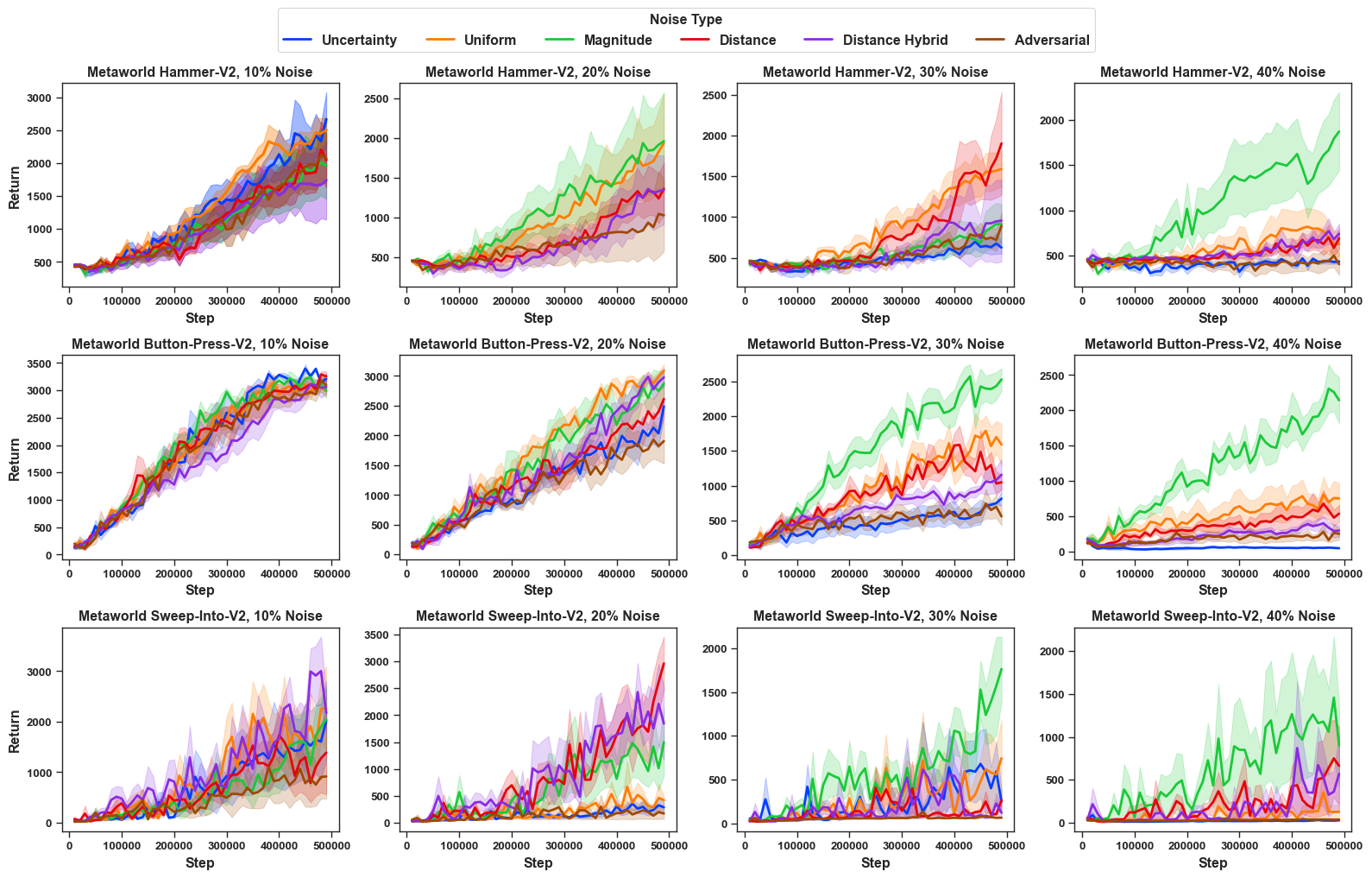

We also show our evaluation results on three Metaworld domains: Metaworld Button Press, Metaworld Sweep Into and Metaworld Hammer. The results are shown in Figure 8. While exceptions exist, we see uncertainty-aware noise, adversarial noise, and hybrid noise with L2 distance are often harder than uniform noise, and trajectory feature magnitude noise is often easier. This is consistent with our previous results in DMControl Domains.

Trajectory Feature Noise. The corruption levels of Metaworld domains produce different results based on the tasks and noise intensity levels. For this noise, we used the displacement of the end-effector as the feature space for all three domains. The results are presented in Figure 8 as denoted by Magnitude (green). Detailed results on the average final reward and the deviation of the same can be seen in Table [tab:metaworld_results]. The Hammer results show that Trajectory Feature noise helps because it adds mild variability that improves robustness. The noise level between 20% and 40% causes the system to perform actions in an unbalanced manner, which makes it difficult for the agent to determine the superior trajectories. In Button-Press, low noise (10%) helps, but larger noise corrupts the trajectory labels. Trajectory Feature noise in Sweep-Into at higher levels of noise is relatively easy to handle and shows much higher returns than uniform noise.

Adversarial Noise. As shown in Figure

8 denoted by

Adversarial(brown), the results show that Adversarial noise produces

the smallest returns in every domain because it successfully interferes

with preference labels. The results from Hammer and Button-Press show

that returns decrease sharply when corruption levels exceed 20–30%

because adversarial perturbations create systematic misdirection that

causes learning instability. Sweep-Into shows the highest sensitivity

because it fails to work with minimal noise levels which means that

adversarial perturbations break down preference consistency.

Trajectory Similarity Noise. As shown in Figure

8 denoted by Distance

(red), the effect of this noise remains better compared to Uniform

noise when the corruption level increases. The effect of Hammer-V2

becomes more pronounced when noise levels increase.

Similarity Hybrid Noise. As shown in Figure

8 denoted by Distance

Hybrid(purple), the degradation pattern of this noise appears more

gradual than what occurs with Distance noise or Adversarial noise alone.

It performs comparably to Uniform at 10–20% noise but causes a

consistent decline beyond 30%.

Uncertainty-Aware Noise. As shown in Figure

8 denoted by

Uncertainty(blue), it demonstrates stable performance under all

noise conditions. The model’s predictive uncertainty leads to a sharp

drop in performance between 30% and 40% noise.

VLM Prompt Templates

In this section, we present our prompt to elicit preferences. We adapt a similar setting from RL-VLM-F : we query VLM to summarise the observations first, and then ask VLM to think about the differences from the image observation summaries: which one is closer to the goal? We refer to these two prompts as the Image Summary Prompt and the Preference Elicitation Prompt. Furthermore, if the VLM cannot find significant differences between the two images, then we have indifferent preference, and we won’t use them in training.

1. What is shown in Image 1?

2. What is shown in Image 2?

3. The goal is to balance the brown pole on the black cart to be upright. Are there any differences between Image 1 and Image 2 in terms of achieving the goal?

<Image 1>

<Image 2>

Based on the text below to the questions:

1. What is shown in Image 1?

2. What is shown in Image 2?

3. The goal is to balance the brown pole on the black cart to be upright. Are there any differences between Image 1 and Image 2 in terms of achieving the goal?

<Text Summary of Image Observations>

Is the goal better achieved in Image 1 or Image 2? Reply with a single line of 0 if Image 1 achieves the goal better, or 1 if Image 2 achieves the goal better. Reply -1 if unsure or there is no difference.

1. What is shown in Image 1?

2. What is shown in Image 2?

3. The goal is to move the soccer ball into the goal. Are there any differences between Image 1 and Image 2 in terms of achieving the goal?

<Image 1>

<Image 2>

Based on the text below to the questions:

1. What is shown in Image 1?

2. What is shown in Image 2?

3. The goal is to move the soccer ball into the goal. Are there any differences between Image 1 and Image 2 in terms of achieving the goal?

<Text Summary of Image Observations>

Is the goal better achieved in Image 1 or Image 2? Reply a single line of 0 if Image 1 achieves the goal better, or 1 if Image 2 achieves the goal better. Reply -1 if unsure or there is no difference.

VLM Noise Examples

The VLM gives noisy preferences mostly due to these two reasons: (1) similar observations; (2) it requires image understanding ability beyond the VLM. We present here examples of observations where the VLMs made mistakes in our experiments. These examples are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10. In Figure 9, while the left image and right images show rods leaning towards right and left, the angles are very similar, and the VLM cannot give the correct preferences. In Figure 10, in the left image, the soccer is actually already in the goal, while the VLM did not notice and wrongly interpreted the image as “the soccer ball is outside of view”, hence giving incorrect preference.

Results on other algorithms

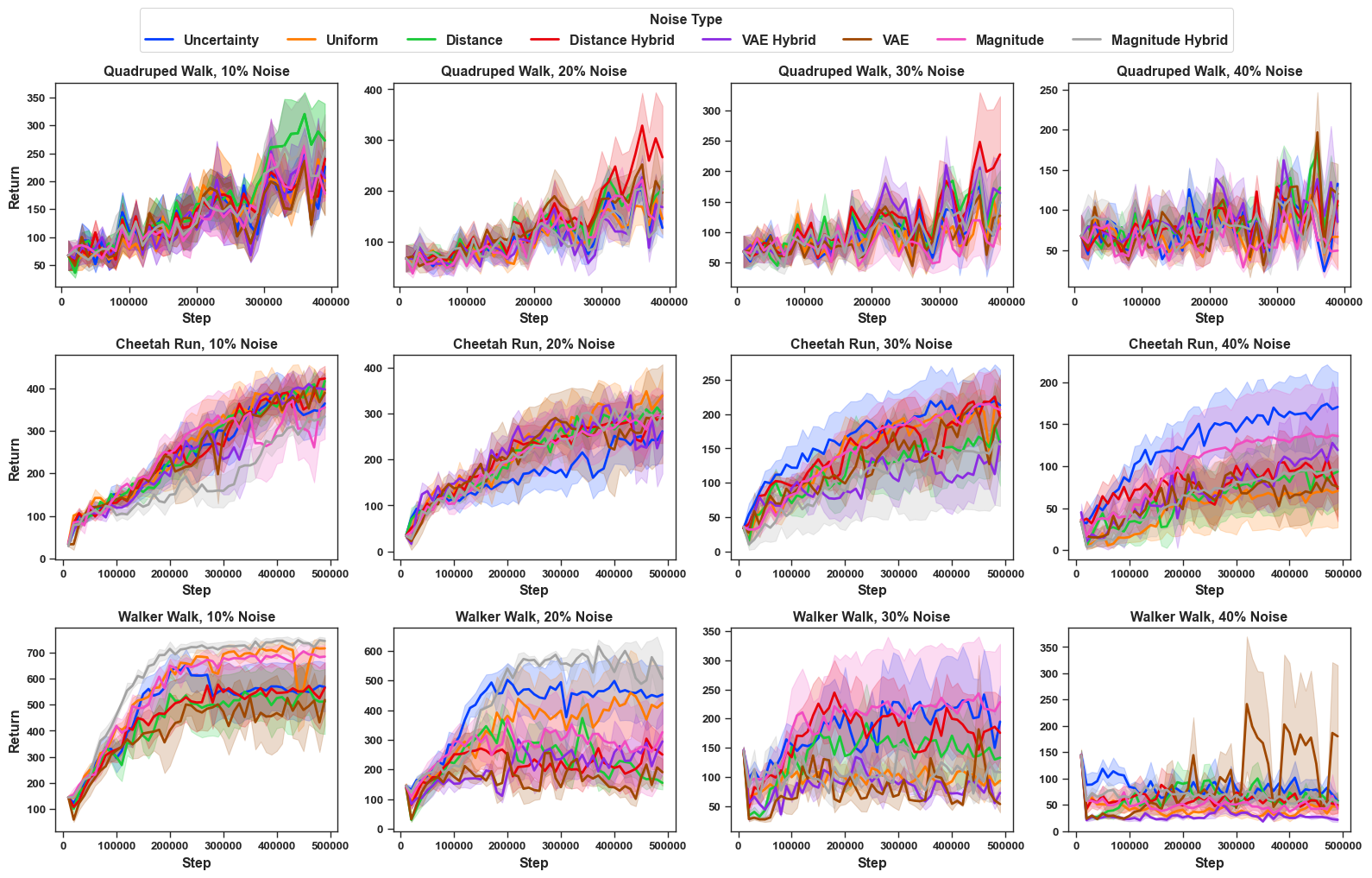

While RIME is one state-of-the-art de-noising PbRL algorithm, we also benchmarked the learning performance of other PbRL algorithms that do not explicitly handle noisy preference, including PEBBLE , SURF and RUNE . The results are shown in Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 respectively. The corresponding final episodic return are shown in Table [tab: episodic_return_all_noise_pebble], Table [tab: episodic_return_all_noise_rune], Table [tab: episodic_return_all_noise_surf]. Across methods, we observe a similar qualitative pattern to RIME: different noise types induce markedly different levels of difficulty. For example, under RUNE, uncertainty noise and magnitude-hybrid noise are generally more challenging as compared uniform noise. However, these trends these trends do not hold consistently across all algorithms and vary with the underlying algorithm. In PEBBLE, uncertainty noise sometimes leads to substantially lower return (more influence on algorithm) than uniform noise usually for higher scales of noise like 30% and 40% noise, but in other cases the ordering reverses. Still, magnitude-hybrid noise is consistently harder than uniform noise for PEBBLE (91% cases in our experiments across domains and scales of noise). For the remaining noise types, performance differences are often irregular and non-monotonic, suggesting that algorithms without explicit denoising mechanisms can be fragile under noisy preference supervision induced by FDN.

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)

A Note of Gratitude

The copyright of this content belongs to the respective researchers. We deeply appreciate their hard work and contribution to the advancement of human civilization.-

If the denoising algorithm reports poor agent performance with feature-dependent noise rather than uniform noise, then it is harder to detect. ↩︎

-

Refer to Table [tab:harder_than_uniform_dmcontrol] and [tab:harder_than_uniform_metaworld] in appendix for more summary statistics of FDNs on DMControl and Metaworld domains. ↩︎

-

Their influence towards episodic return in comparison with uniform noise shows moderate positive correlation with a Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient of 0.57. ↩︎

-

Due to limited computation, we only show runs with one seed for bigger models. ↩︎