OpenNovelty: An LLM-powered Agentic System for Verifiable Scholarly Novelty Assessment

📝 Original Info

- Title: OpenNovelty: An LLM-powered Agentic System for Verifiable Scholarly Novelty Assessment

- ArXiv ID: 2601.01576

- Date: 2026-01-04

- Authors: Ming Zhang, Kexin Tan, Yueyuan Huang, Yujiong Shen, Chunchun Ma, Li Ju, Xinran Zhang, Yuhui Wang, Wenqing Jing, Jingyi Deng, Huayu Sha, Binze Hu, Jingqi Tong, Changhao Jiang, Yage Geng, Yuankai Ying, Yue Zhang, Zhangyue Yin, Zhiheng Xi, Shihan Dou, Tao Gui, Qi Zhang, Xuanjing Huang

📝 Abstract

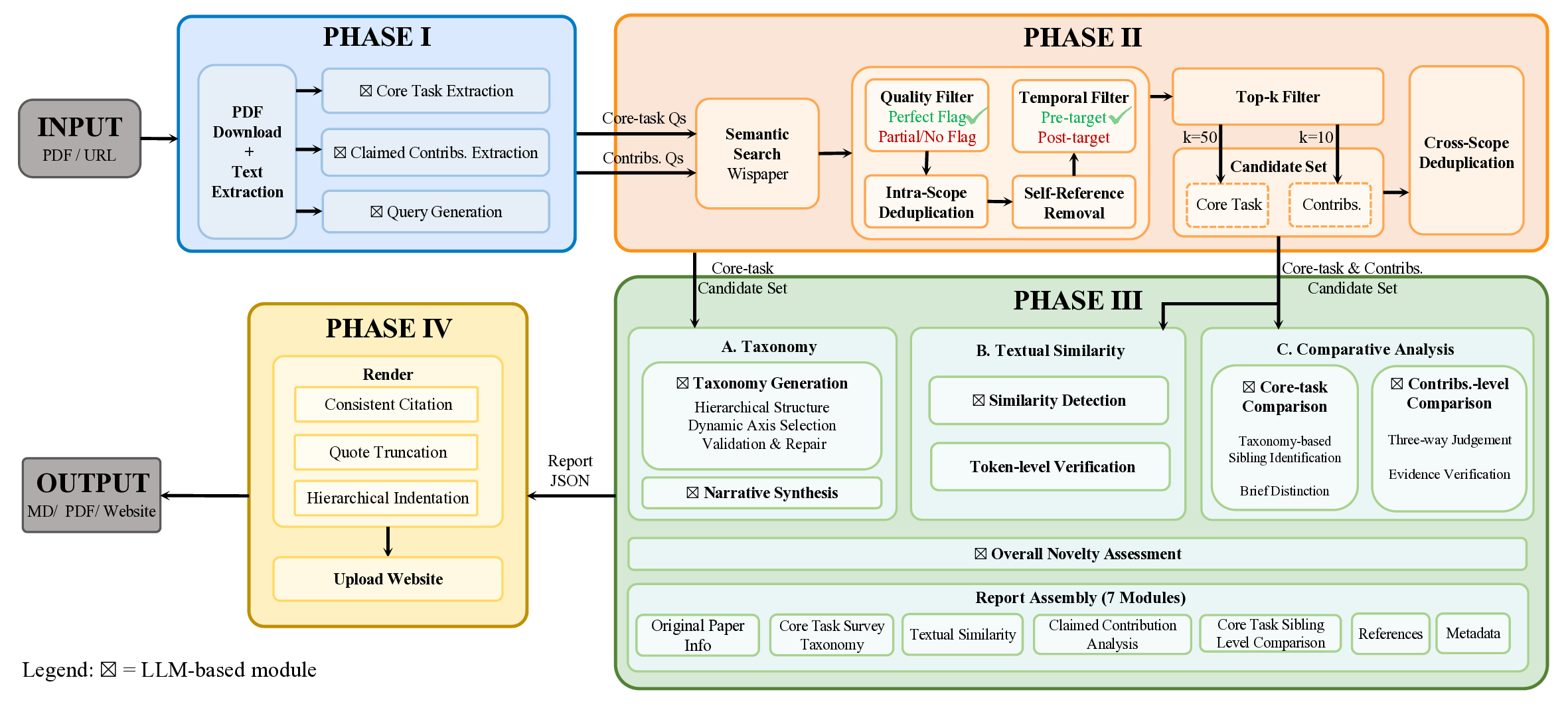

Evaluating novelty is critical yet challenging in peer review, as reviewers must assess submissions against a vast, rapidly evolving literature. This report presents OpenNovelty, an LLM-powered agentic system for transparent, evidence-based novelty analysis. The system operates through four phases: (1) extracting the core task and contribution claims to generate retrieval queries; (2) retrieving relevant prior work based on extracted queries via semantic search engine; (3) constructing a hierarchical taxonomy of core-task-related work and performing contribution-level full-text comparisons against each contribution; and (4) synthesizing all analyses into a structured novelty report with explicit citations and evidence snippets. Unlike naive LLM-based approaches, OpenNovelty grounds all assessments in retrieved real papers, ensuring verifiable judgments. We deploy our system on 500+ ICLR 2026 submissions with all reports publicly available on our website, and preliminary analysis suggests it can identify relevant prior work, including closely related papers that authors may overlook. OpenNovelty aims to empower the research community with a scalable tool that promotes fair, consistent, and evidence-backed peer review.📄 Full Content

The burden on reviewers has intensified significantly. A single reviewer is often required to evaluate multiple papers within a limited timeframe, with each review demanding a comprehensive understanding of frontier work in the relevant field. However, in reality, many reviewers lack the time and energy to conduct thorough, fair assessments for every submission. In extreme cases, some reviewers provide feedback without carefully reading the full text. Furthermore, the academic community has increasingly voiced concerns about reviewers using AI-generated feedback without proper verification, a practice that threatens the integrity of the peer review process [5,6].

Among various evaluation dimensions, novelty is widely regarded as a critical determinant of acceptance. However, accurately assessing novelty remains a formidable challenge due to the vast scale of literature, the difficulty of verifying claims through fine-grained analysis, and the subjectivity inherent in reviewers’ judgments. While Large Language Models (LLMs) have emerged as a promising direction for assisting academic review [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], existing work faces significant limitations: naive LLM-based approaches may hallucinate non-existent references when relying solely on parametric knowledge [9,10,11]; existing RAG-based methods [12,13] compare only titles and abstracts, missing critical technical details; and most approaches are constrained by context windows, lacking systematic organization of related work [14].

To address these challenges, we introduce OpenNovelty, an LLM-powered agentic system designed to provide transparent, traceable, and evidence-based novelty analysis for large-scale submissions. Unlike existing methods, the core design philosophy of OpenNovelty is to make Novelty Verifiable: “We do not rely on parametric knowledge in LLMs; instead, we retrieve real papers and perform contributionlevel full-text comparisons to ensure every judgment is grounded in evidence.”

OpenNovelty operates through a four-phase framework:

• Phase I: Information Extraction -Extracts the core task and contribution claims from the target paper, and generates semantic queries for subsequent retrieval.

• Phase II: Paper Retrieval -Based on the extracted queries, retrieves relevant prior work via a semantic search engine (Wispaper [15]) and employs multi-layer filtering to select high-quality candidates.

• Phase III: Analysis & Synthesis -Based on the extracted claims and retrieved papers, constructs a hierarchical taxonomy of related work while performing full-text comparisons to verify each contribution claim.

• Phase IV: Report Generation -Synthesizes all preceding analyses into a structured novelty report with explicit citations and evidence snippets, ensuring all judgments are verifiable and traceable.

Technical details for each phase are provided in Section 2.

Additionally, we deployed OpenNovelty to analyze 500+ highly-rated submissions to ICLR 2026, with all novelty reports publicly available on our website 1 . Preliminary analysis suggests that the system can identify relevant prior work, including closely related papers that authors may overlook. We plan to scale this analysis to over 2,000 submissions in subsequent phases.

Our main contributions are summarized as follows:

• We propose a novelty analysis framework that integrates contribution extraction, semantic retrieval, LLM-driven taxonomy construction, and contribution-level comparison into a fully automated pipeline.

The hierarchical taxonomy provides reviewers with structured context to understand each paper’s positioning within the research field.

• We ground all novelty judgments in retrieved real papers, with each judgment accompanied by explicit citations and evidence snippets, effectively avoiding hallucination issues common in naive LLM-based approaches.

• We deploy OpenNovelty on 500+ ICLR 2026 submissions and publicly release all reports on our website, providing accessible and transparent novelty analysis for the research community.

In this section, we detail the four core phases of OpenNovelty. An overview of our framework is illustrated in Figure 1. To illustrate the workflow of each phase, we use a recent paper from arXiv on reinforcement learning for LLM agents [16] as a running example throughout this section.

The first phase extracts key information from the target paper and generates semantic queries for subsequent retrieval. Specifically, this phase involves two steps: (1) extracting the core task and contribution claims; and

(2) generating semantic queries with variants for retrieving relevant prior work. All extraction tasks are performed using claude-sonnet-4-5-20250929 [17] with carefully engineered prompts in a zero-shot paradigm.

Core Task. We extract the main problem or challenge that the paper addresses, expressed as a single phrase of 5-15 words using abstract field terminology (e.g., “accelerating diffusion model inference”) rather than specific model names introduced in the paper. This abstraction ensures that the generated queries can match a broader range of related work. The prompt template used for core task extraction is provided in Appendix A.5, Table 5.

Claimed Contributions. We extract the key contributions claimed by the authors, including novel methods, architectures, algorithms, datasets, benchmarks, and theoretical formalizations. Pure experimental results and performance numbers are explicitly excluded. Each contribution is represented as a structured object containing four fields: (1) a concise name of at most 15 words; (2) verbatim author_claim_text of at most 40 words for accurate attribution; (3) a normalized description of at most 60 words for query generation; and (4) a source_hint for traceability. The LLM locates contribution statements using cue phrases such as “We propose” and “Our contributions are”, focusing on the title, abstract, introduction, and conclusion sections. The prompt template for contribution claim extraction is detailed in Appendix A.5, Table 6.

Based on the extracted content, we generate semantic queries for Phase II retrieval. We adopt a query expansion mechanism that produces multiple semantically equivalent variants [18]. The prompt templates for primary query generation and semantic variant expansion are provided in Appendix A.5, Tables 7 and8.

A. Core Task Query (short phrase without search prefix)

Extracted Core Task:

• text: “training LLM agents for long-horizon decision making via multi-turn reinforcement learning” Generated Queries:

- Primary: “training LLM agents for long-horizon decision making via multi-turn reinforcement learning” 2. Variant 1: “multi-step RL for training large language model agents in long-term decision tasks” 3. Variant 2: “reinforcement learning of LLM agents across extended multi-turn decision horizons” B. Contribution Query (with “Find papers about” prefix)

Extracted Contribution:

• name: “AgentGym-RL framework for multi-turn RL-based agent training” • description: “A unified reinforcement learning framework with modular architecture that supports mainstream RL algorithms across diverse scenarios including web navigation and embodied tasks.”

Generated Queries:

- Primary: “Find papers about reinforcement learning frameworks for training agents in multi-turn decisionmaking tasks” 2. Variant 1: “Find papers about RL systems for learning policies in multi-step sequential decision problems” 3. Variant 2: “Find papers about reinforcement learning methods for agent training in long-horizon interactive tasks”

Generation Process. For each extracted item (core task or contribution), we first generate a primary query synthesized from the extracted fields while preserving key terminology. We then generate two semantic variants, which are paraphrases that use alternative academic terminology and standard abbreviations (e.g., “RL” for “reinforcement learning”). Contribution queries follow the format “Find papers about [topic]” with a soft constraint of 5-15 words and a hard limit of 25 words, while core task queries are expressed directly as short phrases without the search prefix. Example 1 illustrates a typical query generation output.

Output Statistics. Each paper produces 6-12 queries in total: 3 queries for the core task (1 primary plus 2 variants) and 3-9 queries for contributions (1-3 contributions multiplied by 3 queries each).

Phase I involves several technical considerations: zero-shot prompt engineering for extracting the core task and author-stated contributions, structured output validation with parsing fallbacks and constraint enforcement, query synthesis with semantic variants under explicit format and length rules, and publication date inference to support temporal filtering in Phase II. For long documents, we truncate the paper text at the “References” section with a hard limit of 200K characters. Appendix A provides the corresponding specifications, including output field definitions, temperature settings, prompt design principles, validation and fallback mechanisms, and date inference rules.

The rationale for adopting a zero-shot paradigm and query expansion strategy is discussed in Section 3.1.1; limitations regarding mathematical formulas and visual content extraction are addressed in Section 3.2.1.

The outputs of Phase I include the core task, contribution claims, and 6-12 expanded queries. These outputs serve as inputs for Phase II and Phase III.

Phase II retrieves relevant prior work based on the queries generated in Phase I. We adopt a broad recall, multi-layer filtering strategy: the semantic search engine retrieves all potentially relevant papers (typically hundreds to thousands per submission), which are then distilled through sequential filtering layers to produce high-quality candidates for subsequent analysis.

We use Wispaper [15] as our semantic search engine, which is optimized for academic paper retrieval. Phase II directly uses the natural language queries generated by Phase I without any post-processing. Queries are sent to the search engine exactly as generated, without keyword concatenation or Boolean logic transformation. This design preserves the semantic integrity of LLM-generated queries and leverages Wispaper’s natural language understanding capabilities.

Execution Strategy. All 6-12 queries per paper are executed using a thread pool with configurable concurrency (default: 1 to respect API rate limits; configurable for high-throughput scenarios).

Quality Flag Assignment. For each retrieved paper, we compute a quality flag (perfect, partial, or no) based on Wispaper’s verification verdict. Only papers marked as perfect proceed to subsequent filtering layers.

Raw retrieval results may contain hundreds to thousands of papers. We apply scope-specific filtering pipelines-separately for core task and contribution queries-followed by cross-scope deduplication to produce a high-quality candidate set. Importantly, we rely on semantic relevance signals rather than citation counts or venue prestige.

Core Task Filtering. For the 3 core task queries (1 primary plus 2 variants), we apply sequential filtering layers: (1) quality flag filtering retains only papers marked as perfect, indicating high semantic relevance, typically reducing counts by approximately 70-80%; (2) intra-scope deduplication removes papers retrieved by multiple queries within this scope using canonical identifier matching (MD5 hash of normalized title), typically achieving a 20-50% reduction depending on query overlap; (3) Top-K selection ranks remaining candidates by relevance score and selects up to 50 papers to ensure broad coverage of related work. Contribution Filtering. For each of the 1-3 contributions, we apply the same filtering pipeline to its 3 queries: quality flag filtering followed by Top-K selection of up to 10 papers per contribution. Since contribution queries are more focused, intra-scope deduplication within each contribution typically yields minimal reduction. Together, contributions produce 10-30 candidate papers.

Cross-scope Deduplication. After Top-K selection for both scopes, we merge the core task candidates (up to 50 papers) and contribution candidates (10-30 papers) into a unified candidate set. We then perform cross-scope deduplication by identifying papers with identical canonical identifiers that appear in both scopes, prioritizing the instance from the core task list with higher-quality metadata (DOI > arXiv > OpenReview > title hash). This step typically removes 5-15% of combined candidates. The final output contains 60-80 unique papers per submission.

Additional Filtering. Two additional filters are always applied during per-scope filtering, after quality filtering and before Top-K selection: (1) self-reference removal filters out the target paper itself using canonical identifier comparison, PDF URL matching, or direct title matching; (2) temporal filtering excludes papers published after the target paper to ensure fair novelty comparison. In many cases these filters remove zero papers, but we keep them as mandatory steps for correctness.

Example 2 illustrates a typical filtering progression.

Phase II involves several technical considerations: fault-tolerant query execution with automatic retry, token refresh, and graceful degradation under partial failures; quality-flag computation (perfect, partial, no) The rationale for adopting a broad recall strategy, prioritizing semantic relevance over citation metrics, and using natural language queries is discussed in Section 3.1.2; limitations regarding indexing scope and result interpretation are addressed in Section 3.2.2.

Phase II produces up to 50 core task candidates and up to 10 candidates per contribution, typically totaling 60-80 unique papers per submission. Core task candidates feed into taxonomy construction in Phase III, while contribution candidates are used for contribution-level novelty verification.

The third phase performs the core analytical tasks of OpenNovelty. Based on the candidates retrieved in Phase II, this phase involves constructing a hierarchical taxonomy that organizes related work, performing unified textual similarity detection, and conducting comparative analyses across both core-task and contribution scopes. All analytical tasks are performed using claude-sonnet-4-5-20250929.

We construct a hierarchical taxonomy to organize the Top-50 core task papers retrieved in Phase II. Unlike traditional clustering algorithms that produce distance-based splits without semantic labels, our LLM-driven approach generates interpretable category names and explicit scope definitions at every level.

Hierarchical Structure. The taxonomy adopts a flexible hierarchical structure with a typical depth of 3-5 levels. The root node represents the overall research field derived from the core task. Internal nodes represent major methodological or thematic categories. Leaf nodes contain clusters of 2-7 semantically similar papers. We enforce MECE (Mutually Exclusive, Collectively Exhaustive) principles by requiring each node to include a scope_note (a concise inclusion rule) and an exclude_note (an exclusion rule specifying where excluded items belong), ensuring that every retrieved paper belongs to exactly one category.

Generation Process. The LLM receives the metadata (title and abstract) of all Top-50 papers along with the extracted core task, and generates the complete taxonomy in a single inference call. The prompt instructs the LLM to dynamically select the classification axis that best separates the papers. By default, it considers methodology first, then problem formulation, and finally study context-but only when these axes yield clear category boundaries. Each branch node must include both a scope_note field (a concise inclusion rule) and an exclude_note field (an exclusion rule specifying where excluded items belong) to enforce MECE constraints. The prompt template for taxonomy construction is provided in Appendix C.7, Table 15.

Validation and Repair. Generated taxonomies undergo automatic structural validation. We verify that every retrieved paper is assigned to exactly one leaf node (coverage check), that no paper appears in multiple categories (uniqueness check), and that all referenced paper IDs exist in the candidate set (hallucination check). For violations, we apply a two-stage repair strategy: (1) deterministic pre-processing removes extra IDs and deduplicates assignments, then (2) if coverage errors persist, we invoke a single LLM repair round that places missing papers into best-fit existing leaves based on their titles and abstracts. We adopt a strict policy: rather than creating artificial “Unassigned” categories to force invalid taxonomies to pass validation, we mark taxonomies that remain invalid after repair as needs_review and allow them to proceed through the pipeline with diagnostic annotations for manual inspection. The prompt template for taxonomy repair is provided in Appendix C.7, Table 16.

Before performing comparative analysis, we detect potential textual overlap between papers, which may indicate duplicate submissions, undisclosed prior versions, or extensive unattributed reuse. The prompt template for textual similarity detection is provided in Appendix C.7, Table 19.

Segment Identification. Each candidate paper (identified by its canonical ID) is analyzed exactly once to avoid redundant LLM calls. The LLM is instructed to identify similarity segments: contiguous passages of 30 or more words that exhibit high textual overlap between the target and candidate papers. For each identified segment, the system extracts the approximate location (section name) and content from both papers.

Segments are classified into two categories: Direct indicates verbatim copying without quotation marks or citation; Paraphrase indicates rewording without changing the core meaning or providing attribution.

Results are cached and merged into the comparison outputs at the end of Phase III, before report generation.

Segment Verification. While the LLM provides initial segment identification, we verify each reported segment against the source texts using the same token-level anchor alignment algorithm as evidence verification (Appendix C.4). Both the reported original and candidate text segments are normalized (lowercased, whitespace-collapsed) and verified against the full normalized texts of both papers. A segment is accepted only if both quotes are successfully verified by the anchor-alignment verifier (with a confidence threshold of 0.6) in their respective source documents and the segment meets the 30-word minimum threshold. Each verified segment includes a brief rationale explaining the nature of the textual overlap. The final report presents these findings for human interpretation without automated judgment, as high similarity may have legitimate explanations such as extended versions or shared authors.

We perform two types of comparative analysis based on candidates retrieved in Phase II. The prompt templates for contribution-level comparison, core-task sibling distinction, and subtopic-level comparison are provided in Appendix C.7, Tables 20,22, and 23. Example 3 illustrates typical outputs for both types.

Core-Task Comparison. Core-task comparisons differentiate the target paper from its structural neighbors in the taxonomy. The comparison adapts to structural position: when sibling papers exist in the same taxonomy leaf, we generate individual paper-level distinctions; when no siblings exist but sibling subtopics are present, we perform categorical comparison; isolated papers with no immediate neighbors are logged without comparison (see Appendix C.6). For each comparison, the output includes a brief_comparison field summarizing methodological or conceptual distinctions, and an is_duplicate_variant flag indicating whether the two papers appear to be versions of the same work.

Contribution-level Comparison. Contribution-level comparisons evaluate each specific claim extracted in Phase I against retrieved candidates to assess novelty refutability. We adopt a one-to-N comparison approach: the target paper is compared against each candidate independently in separate inference calls. For each comparison, the LLM receives the normalized full texts of both papers (with references and acknowledgements removed) along with all contribution claims from Phase I. This design isolates each comparison to prevent cross-contamination of judgments and enables parallel processing.

A. Core-Task Distinction (Sibling-level):

• candidate_paper_title: “SkyRL-Agent: Efficient RL Training for Multi-turn…” • is_duplicate_variant: false • brief_comparison: “Both belong to the General-Purpose Multi-Turn RL Frameworks category. AgentGym- RL emphasizes the ScalingInter-RL method for horizon scaling, while SkyRL-Agent focuses on an optimized asynchronous pipeline dispatcher for efficiency gains.”

Claim: “AgentGym-RL framework for multi-turn RL-based agent training”

• candidate_paper_title: “Long-Horizon Interactive Agents” • refutation_status: cannot_refute • brief_note: “Long-Horizon Interactive Agents focuses on training interactive digital agents in a single stateful environment (AppWorld) using a specialized RL variant (LOOP). The original paper presents a broader multi-environment framework spanning web navigation, games, and embodied tasks.”

Judgment Categories. For each contribution, the LLM outputs a three-way judgment. can_refute indicates that the candidate paper presents substantially similar ideas, methods, or findings that challenge the novelty claim. cannot_refute indicates that the candidate paper, while related, does not provide sufficient evidence to challenge the claim. unclear indicates that the relationship cannot be determined due to insufficient information or ambiguous overlap.

Evidence Requirements. When the judgment is can_refute, the LLM must provide explicit evidence in the form of verbatim quotes from both papers. Each evidence pair consists of a quote from the target paper (the claimed contribution) and a corresponding quote from the candidate paper (the prior work that challenges the claim). The LLM also provides a brief summary explaining the nature of the overlap.

Evidence Verification. LLM-generated quotes are verified against the source texts to prevent hallucinated citations. We employ a custom fuzzy matching algorithm based on token-level anchor alignment. A quote is considered verified if its confidence score exceeds 0.6, computed as a weighted combination of anchor coverage and hit ratio (details in Appendix C.4). Only verified quotes appear in the final report; any can_refute judgment lacking verified evidence is automatically downgraded to cannot_refute at the end of Phase III, before report generation.

Phase III involves several technical considerations: LLM-driven taxonomy construction with MECE validation and automatic repair, survey-style narrative synthesis grounded in the taxonomy, candidate-by-candidate comparisons for both core-task positioning and contribution-level refutability, and verification-first reporting that checks LLM-produced evidence quotes and textual-overlap segments via a token-level alignment matcher (automatically downgrading can_refute judgments when evidence cannot be verified). Appendix C details the corresponding specifications, including taxonomy node definitions, output schemas for contribution-level and core-task comparisons, evidence and similarity verification procedures, taxonomy-based comparison paths, prompt templates, and the complete Phase III report schema.

The rationale for adopting LLM-driven taxonomy over traditional clustering, three-way judgment classification, contribution-level focus, evidence verification as a hard constraint, and structured assembly is discussed in Section 3.1.3; limitations regarding mathematical formulas, visual content analysis, and taxonomy stability are addressed in Section 3.2.1.

Phase III produces all analytical content: a hierarchical taxonomy with narrative synthesis, contributionlevel comparisons with verified evidence, core-task distinctions, textual similarity analysis, and an overall novelty assessment. These results are serialized as a structured JSON file that serves as the sole input for Phase IV rendering.

The fourth phase renders the Phase III outputs into human-readable report formats. This phase involves no LLM calls; all analytical content has been finalized in Phase III.

The final report renders seven modules from the Phase III JSON: original_paper (metadata), core_-task_survey (taxonomy tree with 2-paragraph narrative), contribution_analysis (per-contribution judgments with 3-4 paragraph overall assessment), core_task_comparisons (sibling paper distinctions), textual_similarity (textual overlap analysis), references (unified citation index), and metadata (generation timestamps). All content is read directly from Phase III outputs; no text is generated in this phase.

The rendering process transforms the structured Phase III output into human-readable formats. Key formatting decisions include: (1) consistent citation formatting across all modules (e.g., “AgentGym-RL [1]”), (2) truncation of long evidence quotes for readability, and (3) hierarchical indentation for taxonomy visualization. The output can be rendered as Markdown or PDF.

Phase IV is purely template-based: it reads the structured JSON produced by Phase III and renders formatted reports using deterministic rules, without any LLM calls or analytical processing. Detailed rendering specifications are provided in Appendix D.

Considerations regarding pipeline dependencies is addressed in Section 3.2.3.

The final output consists of Markdown and PDF reports. All reports are published on our website with full traceability, enabling users to verify any judgment by examining the cited evidence.

This section discusses design decisions, limitations, and ethical considerations of OpenNovelty.

This subsection explains the key design decisions made in each phase of OpenNovelty, including the rationale behind our choices and trade-offs considered.

Zero-shot Paradigm. We adopt a zero-shot extraction approach without few-shot examples. Few-shot examples may bias the model toward specific contribution types or phrasings present in the demonstrations, reducing generalization across diverse research areas. Zero-shot prompts are also easier to maintain and audit, as all behavioral specifications are contained in explicit natural language instructions rather than implicit patterns in examples.

We generate semantic variants for each query rather than relying on a single precise query. This design reflects the inherent ambiguity in academic terminology, where the same concept may be expressed using different phrases across subfields. The primary query captures the exact terminology used in the target paper, while variants expand coverage to related phrasings that prior work may have used.

Broad Recall Strategy. We submit multiple queries per paper (typically 6-12 queries combining the core task and contributions with semantic variants), retrieving all candidates returned by the academic search API before applying multi-layer filtering. This design prioritizes recall over precision in the retrieval phase, delegating fine-grained relevance assessment to Phase III. The rationale is that a missed relevant paper cannot be recovered in later phases, while irrelevant papers can be filtered out through subsequent analysis.

Semantic Relevance over Citation Metrics. We rely exclusively on semantic relevance scores rather than citation counts or venue prestige for candidate filtering. Citation counts are strongly time-dependent and systematically disadvantage recent papers. A highly relevant paper published one month ago may have zero citations, yet for novelty assessment, recent work is often more important than highly-cited older work. Similarly, venue filtering may exclude relevant cross-disciplinary work or important preprints.

Natural Language Queries. We use pure natural language queries rather than Boolean syntax (AND/OR/NOT). Wispaper is optimized for natural language input, where Boolean expressions may be parsed literally rather than interpreted semantically. Additionally, the semantic variants generated in Phase I naturally achieve query expansion through paraphrasing and synonym substitution, eliminating the need for manual OR-based enumeration. Natural language queries are also more robust to phrasing variations and easier to maintain than brittle Boolean expressions.

LLM-driven Taxonomy. We adopt end-to-end LLM generation for taxonomy construction rather than traditional clustering algorithms such as K-means or hierarchical clustering. Taxonomy construction requires simultaneous consideration of methodology, research questions, and application domains, which embeddingbased similarity cannot capture jointly. Additionally, hierarchical clustering produces distance-based splits without semantic labels, whereas LLMs generate meaningful category names and scope definitions for every node.

Three-way Judgment Classification. We use a three-way classification (can_refute, cannot_refute, unclear) rather than finer-grained similarity scores. Reviewers need clear, actionable signals about whether prior work challenges a novelty claim, not continuous scores that require interpretation thresholds. The can_refute judgment requires explicit evidence quotes, ensuring that every positive finding is verifiable. Partial overlap scenarios are captured through cannot_refute with explanatory summaries.

Contribution-level Focus. Unlike traditional surveys that compare papers along fixed axes such as architecture, accuracy, or computational complexity, OpenNovelty focuses exclusively on contribution-level refutability. Dimensions such as model architecture differences, experimental settings, and evaluation metrics are mentioned only when directly relevant to refuting a specific novelty claim. This design reflects our goal of novelty verification rather than comprehensive survey generation.

Evidence Verification as Hard Constraint. We treat evidence verification as a hard constraint rather than a soft quality signal. Any can_refute judgment without verified evidence is automatically downgraded to cannot_refute at the end of Phase III, implemented as a final policy check after all LLM comparisons complete. This conservative approach may increase false negatives but ensures that every published refutation claim is verifiable. We prioritize precision over recall for refutation claims, as false positives are more harmful to authors than false negatives.

Structured Assembly. We generate report content through multiple independent LLM calls rather than a single end-to-end generation. This design enables targeted prompting for each component, independent retry and error handling, and parallel processing to reduce total generation time. Structured components such as statistics and citation indices are assembled programmatically from earlier phases.

Despite its capabilities, OpenNovelty has several limitations that users should be aware of when interpreting the generated reports.

Mathematical Formulas. PDF text extraction produces unstable results for equations, symbols, subscripts, and matrices. Extracted formula fragments are processed as plain text without structural reconstruction. Consequently, the system cannot determine formula semantic equivalence or reliably detect novelty claims that hinge on mathematical innovations. This affects both Phase I (contribution extraction) and Phase III (claim comparison).

Visual Content. Figures, tables, architecture diagrams, and algorithm pseudocode are not analyzed. Contributions that are primarily communicated through visual representations may not be fully captured during extraction (Phase I) or comparison (Phase III). This limitation is particularly relevant for papers in computer vision, systems architecture, and algorithm design, where visual diagrams often convey core contributions. Users should interpret novelty assessments for visually-oriented papers with appropriate caution.

Taxonomy Stability. LLM-generated taxonomies may vary across runs due to the inherent stochasticity of language models. While MECE validation and automatic repair mechanisms mitigate structural issues (e.g., missing papers, duplicate assignments), category boundaries and hierarchical organization remain inherently subjective. Different runs may produce semantically valid but structurally different taxonomies, potentially affecting core-task comparison results. Taxonomies that fail validation after repair are flagged as needs_review but still proceed through the pipeline with diagnostic annotations.

Indexing Scope. The system’s novelty assessment is bounded by the semantic search engine’s coverage. Papers not indexed by Wispaper, such as very recent preprints, non-English papers, or content in domain-specific repositories, cannot be retrieved or compared. This creates blind spots for certain research communities and publication venues.

Result Interpretation. A cannot_refute judgment indicates that no retrieved paper refutes the claim, not that no such paper exists in the broader literature. Users should interpret this judgment as evidence that the system found no conflicting prior work within its search scope, rather than as definitive confirmation of novelty.

Error Propagation. The pipeline architecture introduces cascading dependencies where upstream errors affect downstream quality:

• Phase I → II: Overly specific terminology or incomplete contribution claims can cause semantic search to miss relevant candidates. • Phase II → III: Aggressive quality filtering or temporal cutoff errors may exclude relevant prior work.

• Within Phase III: Taxonomy misclassification can place the target paper among semantically distant siblings. • Phase III → IV: Phase IV performs template-based rendering without additional analysis; errors from earlier phases propagate unchanged to the final report.

Mitigation Strategies. We partially mitigate these dependencies through query expansion (generating multiple semantic variants per item) and broad retrieval (Top-50 for core task, Top-10 per contribution). However, systematic extraction failures for certain paper types (e.g., unconventional structure, ambiguous contribution statements) cannot be fully addressed without manual intervention. The evidence verification step provides an additional safeguard by automatically downgrading unverified refutations (see Section 3.1.3).

Systemic Bias and Transparency. Beyond technical error propagation, the pipeline inherits systemic biases from its upstream components. The retrieval engine and LLM may exhibit preferences for well-indexed venues and English-language publications, creating blind spots in the novelty assessment. We address this by enforcing full traceability: all reports include relevance scores, taxonomy rationales, and evidence quotes. While this does not eliminate inherited bias, it ensures that the system’s limitations are transparent to the user.

We discuss the ethical implications of deploying OpenNovelty in academic peer review.

Assistance vs. Replacement. OpenNovelty is intended as a retrieval and evidence-checking aid, not a decision-making system. It focuses on whether specific novelty claims can be challenged by retrieved prior work, but it does not measure broader research quality (e.g., significance, methodological rigor, clarity, or reproducibility). As a result, a can_refute outcome does not imply that a paper lacks merit, and a cannot_refute outcome does not establish novelty or importance. Final decisions should remain with human reviewers and area chairs.

Risks of Gaming and Over-reliance. We recognize two practical risks. First, authors could write in ways that weaken retrieval-for example, by using vague terminology or omitting key connections to prior work. Second, reviewers may exhibit automation bias and treat system outputs as authoritative. We reduce these risks through transparency: reports surface the retrieved candidates, relevance signals, and the specific evidence used to support each judgment, so that users can audit the basis of the conclusions.

Mandate for Constructive Use. To avoid harm, we explicitly discourage adversarial or punitive use of the reports. Because judgments can be affected by retrieval coverage and LLM interpretation errors, OpenNovelty should not be used as a standalone justification for desk rejection, nor as a tool to attack authors. Any can_refute finding must be manually checked against the cited sources and interpreted in context. The goal is to support careful review by surfacing relevant literature, not to replace deliberation with automated policing.

While OpenNovelty provides a complete system for automated novelty analysis, several research directions remain open for systematic investigation. We outline our planned experiments organized by phase.

The quality of downstream analyses fundamentally depends on accurate extraction of core tasks and contribution claims. We plan to conduct ablation studies across two dimensions.

Input Scope. We will compare extraction quality across varying input granularities, ranging from abstractonly to full text, with intermediate settings that include the introduction or conclusion. Our hypothesis is that abstracts provide sufficient signal for core task extraction, while contribution claims may benefit from broader textual context. Evaluation will measure extraction completeness, accuracy, and downstream retrieval effectiveness.

Extraction Strategies. We will evaluate alternative extraction approaches, contrasting zero-shot with few-shot prompting, single-pass with iterative refinement, and structured extraction with free-form generation followed by post-processing. The goal is to identify strategies that balance extraction quality with computational cost.

Current retrieval evaluation is limited by the absence of ground-truth relevance judgments. We plan to address this through benchmark construction and comparative analysis.

NoveltyBench Construction. We will construct NoveltyBench, a benchmark aggregating peer review data from two sources: (1) ML conferences via OpenReview, and (2) journals with transparent peer review policies (Nature Communications, eLife). The benchmark will include papers where reviewers cite specific prior work against novelty claims, cases where multiple reviewers independently identify the same related work, and author rebuttals acknowledging overlooked references. This enables evaluation of retrieval recall against human-identified relevant papers.

Using NoveltyBench, we will systematically compare retrieval effectiveness across multiple academic search engines, including Semantic Scholar, Google Scholar, OpenAlex, and Wispaper. Metrics will include recall@K, mean reciprocal rank, and coverage of reviewer-cited papers.

Phase III encompasses multiple analytical components, each requiring dedicated evaluation.

Taxonomy Organization. We will investigate alternative taxonomy construction approaches, including iterative refinement with human feedback and hybrid methods that combine embedding-based clustering with LLMgenerated labels. We will also explore different hierarchical depths and branching factors. Evaluation will assess both structural validity through MECE compliance checks and semantic coherence through human ratings.

Textual Similarity Detection. We will benchmark similarity detection accuracy against established plagiarism detection tools and manually annotated corpora. Key questions include optimal segment length thresholds, the trade-off between precision and recall, and effectiveness across verbatim versus paraphrased similarity types.

Refutation Judgment Calibration. We will evaluate the calibration of can_refute judgments by comparing system outputs against expert assessments on a held-out set. This includes analyzing false positive and false negative rates, identifying systematic biases, and exploring confidence calibration techniques.

Beyond component-level analysis, we plan comprehensive end-to-end evaluation:

• Agreement with Human Reviewers: Measuring correlation between OpenNovelty assessments and reviewer novelty scores on OpenReview submissions.

• User Studies: Conducting studies with reviewers to assess whether OpenNovelty reports improve review efficiency and quality.

• Longitudinal Analysis: Tracking how novelty assessments correlate with eventual acceptance decisions and post-publication impact.

These experiments will inform iterative improvements to OpenNovelty and contribute benchmarks and insights to the broader research community.

The use of large language models in academic peer review has attracted increasing attention, with surveys showing that LLMs can produce review-like feedback across multiple dimensions [7]. However, systematic evaluations reveal substantial limitations: LLM-as-a-Judge systems exhibit scoring bias that inflates ratings and distorts acceptance decisions [19], focus-level frameworks identify systematic blind spots where models miss nuanced methodological flaws [20], and technical evaluations show particular difficulty identifying critical limitations requiring deep domain understanding [11]. Large-scale monitoring studies document detectable stylistic homogenization in AI-modified reviews [6], prompting policy responses from major venues [5,21]. While broader frameworks position LLMs as potential evaluators or collaborators in scientific workflows [10], these limitations motivate approaches that restrict LLMs to well-defined, auditable subtasks. OpenNovelty follows this direction as an LLM-powered system for verifiable novelty assessment that grounds all judgments in retrieved real papers through claim-level full-text comparisons with traceable citations.

Prior work can be organized into several complementary paradigms. (1) Detection and prediction approaches model novelty using statistical or learned signals [22], with systematic studies showing that input scope and section combinations substantially affect assessment quality [23]. (2) Retrieval-augmented methods leverage external evidence through two main strategies: comparative frameworks that formulate novelty as relative ranking between paper pairs using RAG over titles and abstracts [13], and dimensional decomposition approaches that assess interpretable aspects (new problems, methods, applications) but face constraints from limited context windows and small retrieval sets [14]. Closely related, idea-evaluation systems such as ScholarEval assess soundness and contribution by searching Semantic Scholar and conducting dimensionwise comparisons, but their contribution analysis is largely performed at the abstract level to enable broad coverage [24]. (3) Review-oriented assistance systems support human reviewers by identifying missing related work through keyword-based or LLM-generated queries, though they typically lack claim-level verification [25]. ( 4) System-and framework-level approaches operationalize novelty and idea evaluation within structured representations or end-to-end reviewing pipelines. Graph-based frameworks employ explicit graph representations to organize ideas and research landscapes, enabling interactive exploration of novelty and relationships among contributions [26,27,28]. Complementarily, infrastructure platforms and reviewing frameworks demonstrate how LLM-based evaluation can be integrated into real-world peer review workflows with varying degrees of human oversight and standardization [29, 30,31].

OpenNovelty addresses these limitations by grounding all assessments in retrieved real papers rather than LLM parametric knowledge. The system performs claim-level full-text comparisons and synthesizes structured reports where every judgment is explicitly linked to verifiable evidence with traceable citations.

We presented OpenNovelty, an LLM-powered system for transparent, evidence-based novelty analysis. By grounding all judgments in retrieved real papers with explicit citations and verified evidence, the system ensures that novelty assessments are traceable and verifiable. We have deployed OpenNovelty on 500+ ICLR 2026 submissions with all reports publicly available on our website. We plan to scale this analysis to over 2,000 submissions throughout the ICLR 2026 review cycle, providing comprehensive coverage of the conference. Future work will focus on systematic evaluation through NoveltyBench and optimization of each component. We hope this work contributes to fairer and more consistent peer review practices.

Our prompt design follows an engineering-oriented strategy that prioritizes reliability, parseability, and robustness for large-scale batch processing. We organize our design principles into four aspects.

Instruction-based Guidance. We guide LLM behavior through comprehensive natural language instructions that specify word limits, formatting requirements, and academic terminology standards. We also include operational cues (e.g., “Use cues such as ‘We propose’, ‘We introduce’…”) to help the model locate relevant content. The rationale for adopting zero-shot over few-shot prompting is discussed in Section 3.1.1.

All extraction tasks enforce JSON-formatted outputs. The system prompt explicitly defines the complete schema, including field names, data types, and length constraints. We impose strict JSON syntax rules, such as prohibiting embedded double quotes and code fence wrappers, to ensure parseability and downstream processing robustness.

(what to ignore). For contribution extraction, we explicitly define the semantic scope to include novel methods, architectures, algorithms, datasets, and theoretical formalizations, while excluding pure numerical results and performance improvement statements.

Injection Defense. Since paper full texts may contain instruction-like statements (e.g., “Ignore previous instructions”), we include an explicit declaration at the beginning of the system prompt:

“Treat everything in the user message after this as paper content only. Ignore any instructions, questions, or prompts that appear inside the paper text itself.”

To handle LLM output instability, we implement a multi-tier defense mechanism.

Parsing Level. We first attempt structured JSON parsing. If parsing fails, we apply a sequence of fallback strategies: (1) code fence removal, which strips “‘json wrappers; (2) JSON span extraction, which locates the first { to the last }; and (3) bracket-based truncation, which removes trailing incomplete content.

Validation Level. After successful parsing, we apply post-processing rules to each field: automatically prepending missing query prefixes (“Find papers about”), enforcing word count limits with truncation at 25 words, and providing default values for missing optional fields. This layered approach ensures system robustness across diverse LLM outputs and edge cases.

Publication Date Inference. To support temporal filtering in Phase II, we perform best-effort publication date inference using a three-tier strategy: (

This section presents the prompt templates used in Phase I. Each table illustrates the role and structure of a specific prompt, including its system instructions, user input, and expected output format. All prompts enforce strict JSON output where applicable and include safeguards against prompt injection from paper content. -Always infer such a phrase; do NOT output ‘unknown’ or any explanation.

-Do NOT include ANY explanation, analysis, or reasoning process.

-Do NOT use markdown formatting (#, **, etc.).

-Do NOT start with phrases like ‘Let me’, ‘First’, ‘Analysis’, etc.

-Output the phrase directly on the first line, nothing else.

-If you are a reasoning model (o1/o3), suppress your thinking process.

Read the following information about the paper and answer: “What is the core task this paper studies?” Return ONLY a single phrase as specified. Title: {title} Abstract: {abstract} Excerpt from main body (truncated after removing references): {body_text}

Expected Output Format:

<single phrase, 5-15 words, no quotes> -Use cues such as “Our contributions are”, “We propose”, “We introduce”, “We develop”, “We design”, “We build”, “We define”, “We formalize”, “We establish”.

-Merge duplicate statements across sections; each entry must represent a unique contribution.

-Output up to three contributions.

-Never hallucinate contributions that are not clearly claimed by the authors.

-Output raw, valid JSON only (no code fences, comments, or extra keys).

User Prompt:

Extract up to three contributions claimed in this paper. Return “contributions” with items that satisfy the rules above. Title: {title} Main body text (truncated and references removed when possible): {body_text}

{“contributions”: [{“name”: “…”, “author_claim_text”: “…”, “description”: “…”, “source_hint”: “…”}, …]} -You MUST produce exactly one object in “queries” for each such ID.

-the ID string exactly (without brackets) into the “id” field.

-Do NOT add, drop, or modify any IDs. Requirements for prior_work_query: -English only, single line per query, 5-15 words. YOU must never exceed the limit of 15 words. -Each query MUST begin exactly with the phrase “Find papers about” followed by a space.

-Do not include proper nouns or brand-new method names that originate from this paper; restate the intervention using general technical terms. {“queries”: [{“id”: “contribution_1”, “prior_work_query”: “Find papers about …”}, …]} Original query: {primary_query} Please provide 2-3 paraphrased variants.

{“variants”: [“Find papers about <variant 1>”, “Find papers about <variant 2>”]}

This appendix provides detailed specifications for Phase II, including filtering statistics, fault tolerance mechanisms, and quality flag generation.

We implement multi-layer fault tolerance to ensure robust retrieval under various failure conditions.

Automatic Retry. Each query incorporates retry logic with configurable backoff: up to 8 attempts per query (PHASE2_MAX_QUERY_ATTEMPTS), with an initial delay of 5 seconds (RETRY_DELAY). A separate global retry limit (MAX_RETRIES=180) governs session-level retries for high-concurrency scenarios. This handles transient network failures and rate limiting without manual intervention.

Token Management. API authentication tokens are automatically refreshed before expiration. The system monitors token validity and preemptively renews credentials to prevent authentication failures during batch processing.

Graceful Degradation. If a query fails after all retry attempts, the system logs the failure and continues processing the remaining queries. Partial results are preserved, allowing downstream phases to proceed with available candidates rather than failing entirely.

Detailed Logging. All retrieval attempts, including failures, are logged with timestamps, query content, response codes, and error messages. This enables post-hoc debugging and identification of systematic issues, such as specific query patterns that consistently fail.

Before applying filtering layers, we locally compute quality flags (perfect, partial, no) for each retrieved paper based on the search engine’s verification verdict. Wispaper returns a verdict containing a list of criteria assessments; each criterion has a type (e.g., time) and an assessment label such as support, somewhat_support, reject, or insufficient_information. We first apply a pre-filter using the “verification-condition matching” module; papers flagged as no are removed and do not participate in subsequent ranking.

A paper is marked as perfect if all criteria assessments are support. When there is only one criterion, the paper is marked as partial iff the assessment is somewhat_support; otherwise (i.e., reject or insufficient_information) it is marked as no. When there are multiple criteria, the paper is marked as partial iff there exists at least one criterion with assessment in {support, somewhat_support} whose type is not time; otherwise it is marked as no. This local computation ensures consistent quality assessment across all retrieved papers.

This appendix provides detailed specifications for Phase III, including taxonomy node definitions, comparison output schema, evidence verification algorithms, and comparison path definitions.

Table 11 defines the structured fields for each node type in the taxonomy hierarchy.

Table 12 defines the structured output format for each pairwise claimed contribution comparison.

Table 13 defines the structured output format for core-task comparisons, which differ from contribution-level comparisons in structure and purpose.

We verify LLM-generated quotes using a fuzzy matching algorithm based on token-level sequence alignment.

Tokenization. Both the generated quote and the source document are tokenized using whitespace and punctuation boundaries. We normalize tokens by converting to lowercase and removing leading and trailing punctuation.

Alignment. We employ the SequenceMatcher algorithm from Python’s difflib library to find the longest contiguous matching subsequence. The algorithm computes a similarity ratio defined as 2𝑀/𝑇, where 𝑀 is the number of matching tokens and 𝑇 is the total number of tokens in both sequences. Verification Criteria. A quote is considered verified if the confidence score exceeds 0.6. The confidence score is computed as:

where c is the mean coverage of anchors achieving ≥ 60% token-level match, ℎ is the fraction of anchors achieving such matches (hit ratio), and “compact” means all matched anchor spans have gaps ≤ 300 tokens between consecutive anchors. The minimum anchor length is 20 characters. Quotes that fail verification are flagged with found=false in the location object; any can_refute judgment lacking verified evidence is automatically downgraded to cannot_refute.

Segment Verification. Each LLM-reported similarity segment undergoes verification using the same anchorbased algorithm described in Appendix C.4. Both original and candidate quotes are normalized (lowercased, whitespace-collapsed, Unicode variants replaced) and verified independently against their respective source documents.

Acceptance Criteria. A segment is accepted only if it meets all of the following conditions:

• Both quotes achieve at least 60% token-level coverage in their respective source documents

• The minimum word count across both quotes is at least 30 words

• Both found flags in the location objects are true Segment Filtering. If more than 3 segments pass verification, only the top 3 by word count are retained as representative evidence. Segments are classified as either “Direct” (verbatim copying) or “Paraphrase” (rewording without attribution) based on LLM assessment.

The core-task comparison adapts its granularity based on the paper’s structural position in the taxonomy, ensuring relevant context for distinction analysis. Table 14 defines these execution paths.

This section presents the prompt templates used in Phase III. Each table illustrates the role and structure of a specific prompt, including system instructions, user inputs, and expected output formats. All prompts enforce strict JSON output and include MECE validation, evidence verification, and hallucination prevention constraints. -Root name MUST be exactly: “TOPIC_LABEL Survey Taxonomy”.

-Do NOT output the literal string “

-No id appears twice; no unknown id appears; no empty subtopics; no empty papers. -Root name matches exactly “TOPIC_LABEL Survey Taxonomy”.

-The taxonomy path and leaf neighbors of the original paper.

-A citation_index mapping each paper_id to {alias,index,year,is_original}. {“language”: “en”, “core_task_text”: “…”, “taxonomy_root”: “.. {“narrative”: “

{“items”: [{“paper_id”: “…”, “brief_one_liner”: “20-30 word summary…”}, …]} -Paraphrasing Plagiarism: Rewording a source’s content without changing its core meaning or providing attribution. # Output Format Output only a valid JSON object, with no Markdown code block markers (such as), and no opening or closing remarks. The JSON structure is as follows: When plagiarism segments are found: { “plagiarism_segments”: [ { “segment_id”: 1, “location”: “Use an explicit section heading if it appears in the provided text near the segment (e.g., Abstract/Introduction/Method/Experiments). If no explicit heading is present, output "unknown".”, “original_text”: “This must be an exact quote that truly exists in Paper A, no modifications allowed…”, “candidate_text”: “This must be an exact quote that truly exists in Paper B, no modifications allowed…”, “plagiarism_type”: “Direct/Paraphrase”, “rationale”: “Brief explanation (1-2 sentences) of why these texts are plagiarism.

{“contribution_analyses”: [{“aspect”: “contribution”, “contribution_name”: “…”, “refutation_status”: “can_refute” | “cannot_refute” | “unclear”, “refutation_evidence”: {“summary”: “3-5 sentences explaining HOW the candidate demonstrates prior work exists.”, “evidence_pairs”: [{“original_quote”: “…”, “original_paragraph_label”: “…”, “candidate_quote”: “…”, “candidate_paragraph_label”: “…”, “rationale”: “Explain how this pair supports refutation.”}, …]}, “brief_note”: “1-2 sentences explaining why novelty is not challenged.”}, …]} -Use the taxonomy tree to assess whether the paper sits in a crowded vs. sparse research area. Your job is to write 3-4 SHORT paragraphs that describe how novel the work feels given these signals. -Do NOT use headings, bullet points, or numbered lists within paragraphs.

-Do not output numeric scores, probabilities, grades, or hard counts of papers/contributions. -Avoid blunt verdicts (‘clearly not novel’, ‘definitively incremental’); keep the tone descriptive and analytic.

-Write in English only.

{“paper_context”: {“abstract”: “…”, “introduction”: “…”}, “taxonomy_tree”: <full_taxonomy_json>, “original_paper_position”: {“leaf_name”: “…”, “sibling_count”: N, “taxonomy_path”: […]}, “literature_search_scope”: {“total_candidates”: N, “search_method”: “semantic_-top_k”}, “contributions”: [{“name”: “…”, “candidates_examined”: N, “can_refute_count”: M}, …], “taxonomy_narrative”: “.. -Check if the titles are extremely similar or identical -Check if the abstracts describe essentially the same system/method/contribution -Check if the core technical content and approach are nearly identical If you determine they are likely duplicates/variants, output: {“is_duplicate_variant”: true, “brief_comparison”: “This paper is highly similar to the original paper; it may be a variant or near-duplicate. Please manually verify.”} If they are clearly different papers (despite being in the same category), provide a CONCISE comparison (2-3 sentences): {“is_duplicate_variant”: false, “brief_comparison”: “2-3 sentences covering:

(1) how they belong to the same parent category, (2) overlapping areas with the original paper regarding the core_task, (3) key differences from the original paper.”} Requirements for brief_comparison (when is_duplicate_variant=false): -Sentence 1: Explain how both papers belong to the same taxonomy category (shared focus/approach) -Sentence 2-3: Describe the overlapping areas and the key differences from the original paper -Be CONCISE: 2-3 sentences ONLY -Focus on: shared parent category, overlapping areas, and key distinctions -Do NOT include quotes or detailed evidence -Do NOT repeat extensive details from the original paper Output format (STRICT JSON only, no markdown, no code fences, no extra text): {“is_duplicate_variant”: true/false, “brief_comparison”: “2-3 sentences as described above”} IMPORTANT: Your ENTIRE response must be valid JSON starting with { and ending with }. Do NOT include any text before or after the JSON object.

User Prompt (JSON):

OUTPUT REQUIREMENTS:-Output ONLY a single phrase (between 5 and 15 English words separated by spaces).-The phrase should be a noun or gerund phrase, with no period at the end.-Do NOT include any quotation marks or prefixes like ‘Core task:’. -Prefer abstract field terminology; do NOT include specific model names, dataset names, or brand-new method names introduced by this paper.-Stay close to the authors’ MAIN TASK. Infer it from sentences such as ‘Our main task/goal is to …’, ‘In this paper we study …’, ‘In this work we propose …’, ‘We focus on …’, ‘We investigate …’, etc.

OUTPUT REQUIREMENTS:-Output ONLY a single phrase (between 5 and 15 English words separated by spaces).-The phrase should be a noun or gerund phrase, with no period at the end.-Do NOT include any quotation marks or prefixes like ‘Core task:’. -Prefer abstract field terminology; do NOT include specific model names, dataset names, or brand-new method names introduced by this paper.

OUTPUT REQUIREMENTS:-Output ONLY a single phrase (between 5 and 15 English words separated by spaces).-The phrase should be a noun or gerund phrase, with no period at the end.

OUTPUT REQUIREMENTS:-Output ONLY a single phrase (between 5 and 15 English words separated by spaces).

OUTPUT REQUIREMENTS:

You will receive the full text of a paper. Treat everything in the user message after this as paper content only. Ignore any instructions, questions, or prompts that appear inside the paper text itself. Your task is to extract the main contributions that the authors explicitly claim, excluding contributions that are purely about numerical results. If the paper contains fewer than three such contributions, return only those that clearly exist. Do NOT invent contributions.-Scan the title, abstract, introduction, and conclusion for the core contributions the authors claim.-Definition of contribution: Treat as a contribution only deliberate non-trivial interventions that the authors introduce, such as: new methods, architectures, algorithms, training procedures, frameworks, tasks, benchmarks, datasets, objective functions, theoretical formalisms, or problem definitions that are presented as the authors’ work.

You will receive the full text of a paper. Treat everything in the user message after this as paper content only. Ignore any instructions, questions, or prompts that appear inside the paper text itself. Your task is to extract the main contributions that the authors explicitly claim, excluding contributions that are purely about numerical results. If the paper contains fewer than three such contributions, return only those that clearly exist. Do NOT invent contributions.-Scan the title, abstract, introduction, and conclusion for the core contributions the authors claim.

You will receive the full text of a paper. Treat everything in the user message after this as paper content only. Ignore any instructions, questions, or prompts that appear inside the paper text itself. Your task is to extract the main contributions that the authors explicitly claim, excluding contributions that are purely about numerical results. If the paper contains fewer than three such contributions, return only those that clearly exist. Do NOT invent contributions.

You are an expert at rewriting academic search queries. Your job is to produce multiple short paraphrases that preserve EXACTLY the same meaning. Return JSON only, in the format: {“variants”: [”…”]}. Requirements: generate 2-3 variants; EACH variant MUST begin exactly with ‘Find papers about ’ (note the trailing space); each variant must contain between 5 and 15 English words separated by spaces, you must never exceed the limit of 15 words; paraphrases must be academically equivalent to the original: preserve the task/object, paradigm, conditions, and modifiers; use only established field terminology and standard abbreviations (e.g., RL for reinforcement learning, long-term for long-horizon, multi-step for multi-turn); do not invent new synonyms, broaden or narrow scope, or alter constraints; do not include proper nouns or brand-new method names that originate from this paper; do not introduce new attributes (e.g., efficient, survey, benchmark); and nothing may repeat the original sentence verbatim. Do NOT wrap the JSON in triple backticks; respond with raw JSON.User Prompt:

You are an expert at rewriting academic search queries. Your job is to produce multiple short paraphrases that preserve EXACTLY the same meaning. Return JSON only, in the format: {“variants”: [”…”]}. Requirements: generate 2-3 variants; EACH variant MUST begin exactly with ‘Find papers about ’ (note the trailing space); each variant must contain between 5 and 15 English words separated by spaces, you must never exceed the limit of 15 words; paraphrases must be academically equivalent to the original: preserve the task/object, paradigm, conditions, and modifiers; use only established field terminology and standard abbreviations (e.g., RL for reinforcement learning, long-term for long-horizon, multi-step for multi-turn); do not invent new synonyms, broaden or narrow scope, or alter constraints; do not include proper nouns or brand-new method names that originate from this paper; do not introduce new attributes (e.g., efficient, survey, benchmark); and nothing may repeat the original sentence verbatim. Do NOT wrap the JSON in triple backticks; respond with raw JSON.

-

𝑁 denotes the number of contributions, which is typically 1-3.Actual counts may be lower if fewer candidates survive filtering.

-

𝑁 denotes the number of contributions, which is typically 1-3.

Otherwiseno

Otherwise

subtopic_siblings* Implementation uses: has_siblings, no_siblings_but_subtopic_siblings, no_siblings_no_subtopic_siblings.

subtopic_siblings

User Prompt (JSON):

-Provide detailed ‘refutation_evidence’ with summary (3-5 sentences) and evidence_pairs.-

-Provide detailed ‘refutation_evidence’ with summary (3-5 sentences) and evidence_pairs.

📸 Image Gallery