Logics-STEM Empowering LLM Reasoning via Failure-Driven Post-Training and Document Knowledge Enhancement

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Logics-STEM Empowering LLM Reasoning via Failure-Driven Post-Training and Document Knowledge Enhancement- ArXiv ID: 2601.01562

- Date: 2026-01-04

- Authors: Mingyu Xu, Cheng Fang, Keyue Jiang, Yuqian Zheng, Yanghua Xiao, Baojian Zhou, Qifang Zhao, Suhang Zheng, Xiuwen Zhu, Jiyang Tang, Yongchi Zhao, Yijia Luo, Zhiqi Bai, Yuchi Xu, Wenbo Su, Wei Wang, Bing Zhao, Lin Qu, Xiaoxiao Xu

📝 Abstract

We present Logics-STEM, a state-of-the-art reasoning model fine-tuned on Logics-STEM-SFT-Dataset, a high-quality and diverse dataset at 10M scale that represents one of the largest-scale open-source long chain-of-thought corpora. Logics-STEM targets reasoning tasks in the domains of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM), and exhibits exceptional performance on STEM-related benchmarks with an average improvement of 4.68% over the next-best model at 8B scale. We attribute the gains to our data-algorithm co-design engine, where they are jointly optimized to fit a gold-standard distribution behind reasoning. Data-wise, the Logics-STEM-SFT-Dataset is constructed from a meticulously designed data curation engine with 5 stages to ensure the quality, diversity, and scalability, including annotation, deduplication, decontamination, distillation, and stratified sampling. Algorithm-wise, our failure-driven post-training framework leverages targeted knowledge retrieval and data synthesis around model failure regions in the Supervised Fine-tuning (SFT) stage to effectively guide the second-stage SFT or the reinforcement learning (RL) for better fitting the target distribution. The superior empirical performance of Logics-STEM reveals the vast potential of combining large-scale open-source data with carefully designed synthetic data, underscoring the critical role of data-algorithm co-design in enhancing reasoning capabilities through post-training. We make both the Logics-STEM models (8B and 32B) and the Logics-STEM-SFT-Dataset (10M and downsampled 2.2M versions) publicly available to support future research in the open-source community.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **Data and Algorithm Integration**: Viewing the SFT-RL pipeline as a distribution matching problem allows for better integration of data and algorithms to enhance model performance, akin to combining good ingredients to make great food. 2. **Failure-driven Post-training**: Generating data around failure regions guides models to perform better, similar to how students improve by focusing on their weaknesses. 3. **Data Curation Engine**: Combining public and synthetic datasets significantly improves the reasoning abilities of models, much like mixing different ingredients to create a new dish.📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

/>

/>

Introduction

In the past years, large language models (LLMs) like OpenAI’s o1 series , QwQ , and DeepSeek-R1 have demonstrated strong performance on challenging reasoning tasks in the field of mathematics and broader STEM. The reasoning capabilities in these models typically emerge from post-training techniques such as supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and/or reinforcement learning (RL) based on strong foundation models. However, while many models are open-sourced, the underlying post-training pipeline and training data curation remain undisclosed, creating both challenges and opportunities for future work.

More recently, the open-source community has made substantial efforts to develop data-construction recipes and algorithmic strategies for cultivating advanced reasoning capabilities in small-scale models, leading to a series of notable works such as Klear-Reasoner , Ring-Lite , MiMo , OpenThoughts , Llama-Nemotron , and AceReason-Nemotron , among others . However, despite these empirical successes, the community still lacks a unified framework to guide data curation and exploitation through post-training algorithms. It is widely recognized in the LLM community that “data is the new oil”, and the algorithm can only succeed when it effectively captures the desired data distribution. This motivates a central question in training reasoning models:

What does it take to build a Data-algorithm Co-design Engine for

Reasoning Models in terms of Effectiveness, Efficiency, and

Scalability?

In this report, we address this question from both theoretical and engineering perspectives. We first provide a data-centric view of the widely adopted SFT-RL pipeline by framing it as a distribution-matching problem. We hypothesize that the first-stage SFT builds a strong proposal distribution that one draws samples for following usage; and the second stage post-training, no matter SFT or RL, shifts the model towards a gold-standard target distribution behind desirable properties such as reasoning ability.

Building on this formulation, we push the boundaries of reasoning models by: (i) implementing a rigorous data curation pipeline to produce a scalable, broad-coverage, and high-quality long CoT dataset as a foundational proposal distribution; (ii) designing an optimized post-training pipeline that utilizes the curated data effectively and efficiently to improve the model’s reasoning capabilities.

Specifically, we curate reasoning data from publicly available datasets and further augment it with synthetic examples generated from documents parsed by Logics-Parsing . Coupled with a fine-grained, difficulty-aware stratified sampling strategy, extensive experiments show that our curated Logics-STEM-SFT-Dataset already equips LLMs with strong foundational reasoning capabilities. Moreover, we adopt a failure-driven post-training paradigm to further align the model with the gold-standard reasoning distribution. Concretely, after the first-stage SFT, we perform targeted knowledge retrieval and synthesize data around the model’s failure regions to guide a second-stage SFT or RL. This yields two alternative pipelines: SFT–RL and SFT–SFT. We systematically test our method under both SFT-RL and SFT-SFT pipelines and show that our approach substantially improves the model’s reasoning ability.

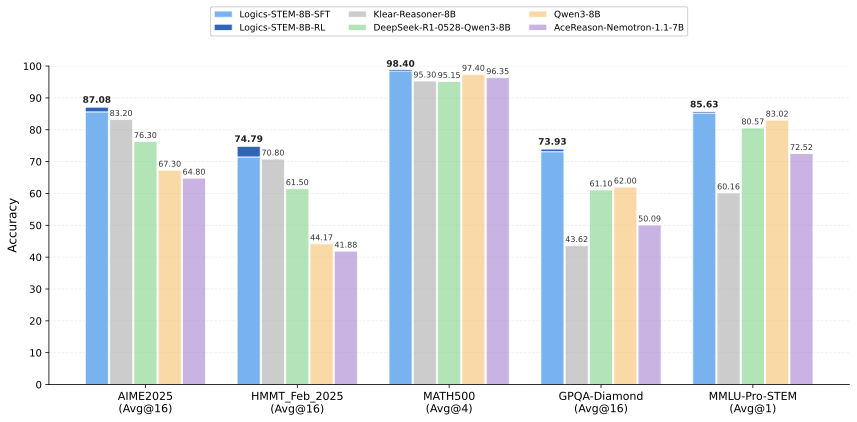

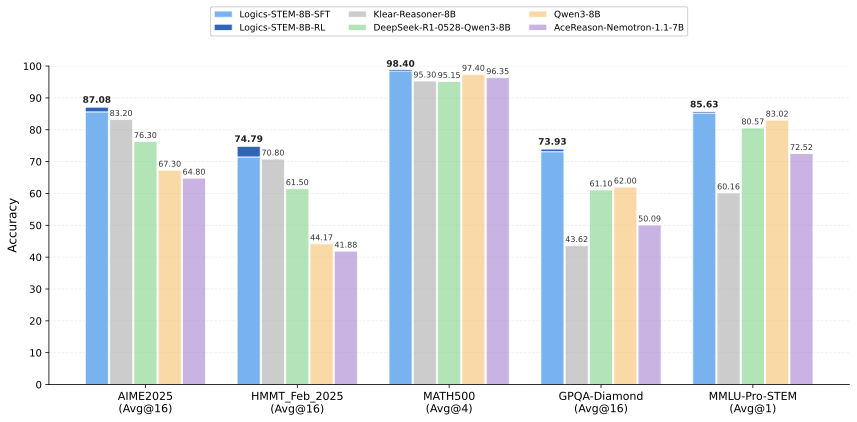

Consequently, we present Logics-STEM, a reasoning model finetuned from Qwen3 that achieves outstanding performance on multiple key reasoning benchmarks. At 8B scale, as shown in 1, Logics-STEM-8B outperforms Klear-Reasoner-8B, DeepSeek-R1-0528-Distill-8B and Qwen3-8B, scoring 90.42% on AIME2024, 87.08% on AIME2025, 74.79% on HMMT2025, 62.5% on BeyondAIME and 73.93% on GPQA-Diamond.

In summary, the contributions of our work are listed as follows.

-

We formulate the SFT-RL pipeline as a distribution matching problem and design a failure-driven post-training framework that leverages targeted knowledge retrieval and data synthesis around model failure regions to effectively and efficiently guide SFT and RL.

-

We design a data curation engine that effectively utilizes publicly available data and augments it with synthetic examples generated from documents. We then produce Logics-STEM-SFT-Dataset, a high-quality and diverse dataset that represents one of the largest‑scale open-source long chain-of-thought corpora at 10M scale.

-

Our reasoning model, Logics-STEM, outperforms other open source models of comparable size on STEM reasoning benchmarks. We release Logics-STEM (8B and 32B) at both the SFT and RL stages, along with the open version of Logics-STEM-SFT-Dataset, to support further research and development within the open-source community.

SFT-RL pipeline as a distribution matching

After pre-training, SFT followed by RL has become a widely adopted recipe for improving LLMs’ reasoning ability . SFT is typically used to familiarize the model with long chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning traces, while RL further aligns the model with human preferences or sharpens the policy distribution to produce more satisfactory responses with fewer samples . From this perspective, the overall post-training procedure can be viewed as optimizing an expected objective estimated via Monte Carlo sampling. Let the training data consist of pairs $`(x, y)`$, where $`x`$ is the prompt and $`y`$ is the target output (e.g., a long-CoT response ending with a boxed final answer). Denote by $`y^t`$ the $`t`$-th token in $`y`$1. We write the sample-level supervised loss as $`\ell_\theta(x, y)`$ (e.g., the negative log-likelihood, NLL), where $`\theta`$ are the model parameters. The training objective is then,

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:pop_risk}

\text{(Expected Risk)}\quad {\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta)=\mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim P^*}\big[\ell_\theta(x,y)\big],

\end{equation}where $`P^*(x,y)`$ denotes the (unknown) ideal target distribution over $`(x,y)`$. However, $`P^*`$ is rarely directly accessible in practice, as it corresponds to a “perfect” or gold-standard distribution for solving reasoning tasks. Instead, one only observes a surrogate dataset $`{\mathcal{D}}`$, which is drawn from some distribution $`P_0(x,y)`$ with $`P_0 \neq P^*`$. This dataset is typically assembled from diverse sources without a unified curation criterion, as we elaborate in 3. Consequently, $`P_0`$ can differ substantially from $`P^*`$, inducing a distribution mismatch between the available training data and the ideal target distribution that would best support reasoning.

The mismatch between target and training distribution.

Practically, a biased optimization is done through minimizing $`\mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim P_0}\big[\ell_\theta(x,y)\big]`$ via Monte Carlo estimation, for which one samples mini-batches $`\{x_i, y_i\}_{i=1}^B`$ from $`P_0`$ and approximate the expectation by the empirical mean. To eliminate the bias between target and training, we first look at the issues that cause high expected risk. We consider an importance sampling formula and reformulate [eq:pop_risk] as

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:iw_grad_form}

{\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta)

=\mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim P^*}\big[\ell_\theta(x,y)\big]=

\mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim P_0}\!\left[

\underbrace{\frac{P^*(x,y)}{P_0(x,y)}}_{\text{Density Ratio}}\underbrace{\,\ell_\theta(x,y)

}_{\text{Sample-wise Loss}}\right],

\end{equation}The high risk of $`{\mathcal{L}}^*`$ is caused by two issues: 1) high density ratio $`\frac{P^*(x,y)}{P_0(x,y)}`$, which means the region is underestimated or rarely seen in training but important in the target distribution; and 2) high sample-wise loss $`\ell_\theta(x,y)`$, which means the model completely fails in these samples.

Remark: From the formula above, we hypothesize that: 1) the first stage SFT is trying to fit the model to a good proposal distribution $`P_0`$, and 2) the second stage RL is trying to explore the region that has a high density ratio and shifts the distribution towards the golden distribution.

We elaborate on the remark a bit. SFT fits the model to $`P_0`$ through a large-scale dataset $`{\mathcal{D}}\sim P_0`$, which provides good proposal distribution with broad coverage and grants the model with general reasoning abilities. However, at this stage, the mismatch between $`P_0`$ and $`P^*`$ would make the optimization biased, thus performing suboptimally on specific tasks. The second stage training is used to implicitly eliminate the bias. For instance, a vanilla policy gradient can be considered as fitting a distribution depending on the advantage function $`A(x,y)`$ ,

\begin{equation}

P^\prime(y \mid x) \propto P_0(y \mid x) e^{\beta A(x,y)},

\end{equation}where $`\beta`$ is the regularization weight. With a proper selection, $`P^\prime`$ can be considered as a good surrogate for the target distribution of $`P^*`$, and the second-stage RL is used to shift the distribution towards $`P^*`$. We provide a detailed discussion in Appendix 9.3.

With this understanding, the second-stage RL can even be replaced by SFT with proper algorithm design, as we will illustrate theoretically in 4 and empirically in 5. As such, we propose two key principles for building a data-algorithm co-design engine for strong reasoning models:

(1) Stage-1 SFT should produce a strong proposal distribution. To this end, we empirically design a data engine that generates high-quality training data, guided by practical experience and engineering insights. 3 details this data engine.

(2) Stage-2 post-training should efficiently shift the model toward the target distribution. In 4, we propose a more effective and efficient way to leverage data to shift the model toward $`P^*`$. Specifically, we introduce a failure-driven resampling for second-stage post-training, enabling target-oriented optimization to enhance reasoning ability.

Reasoning Data Engine

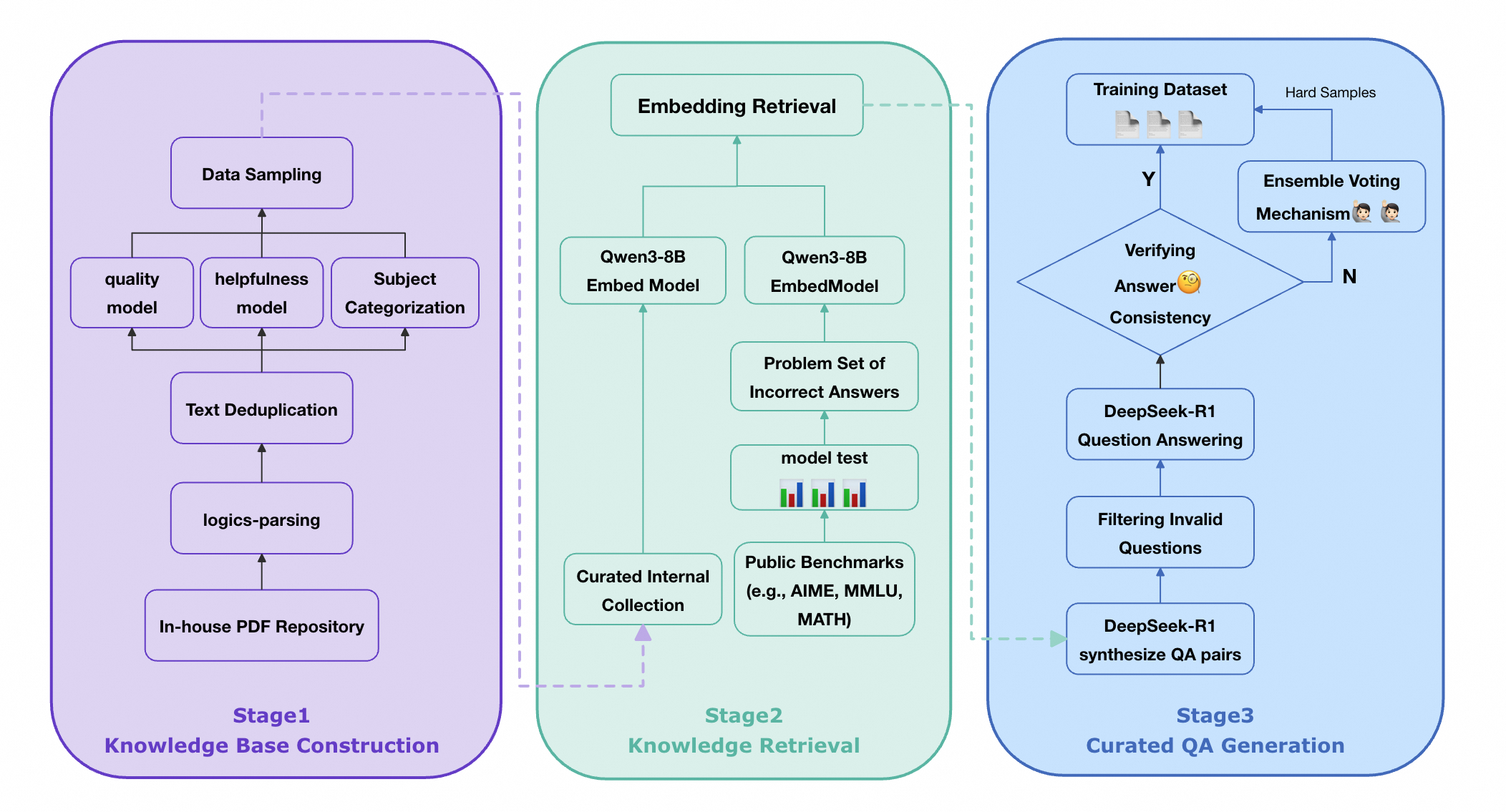

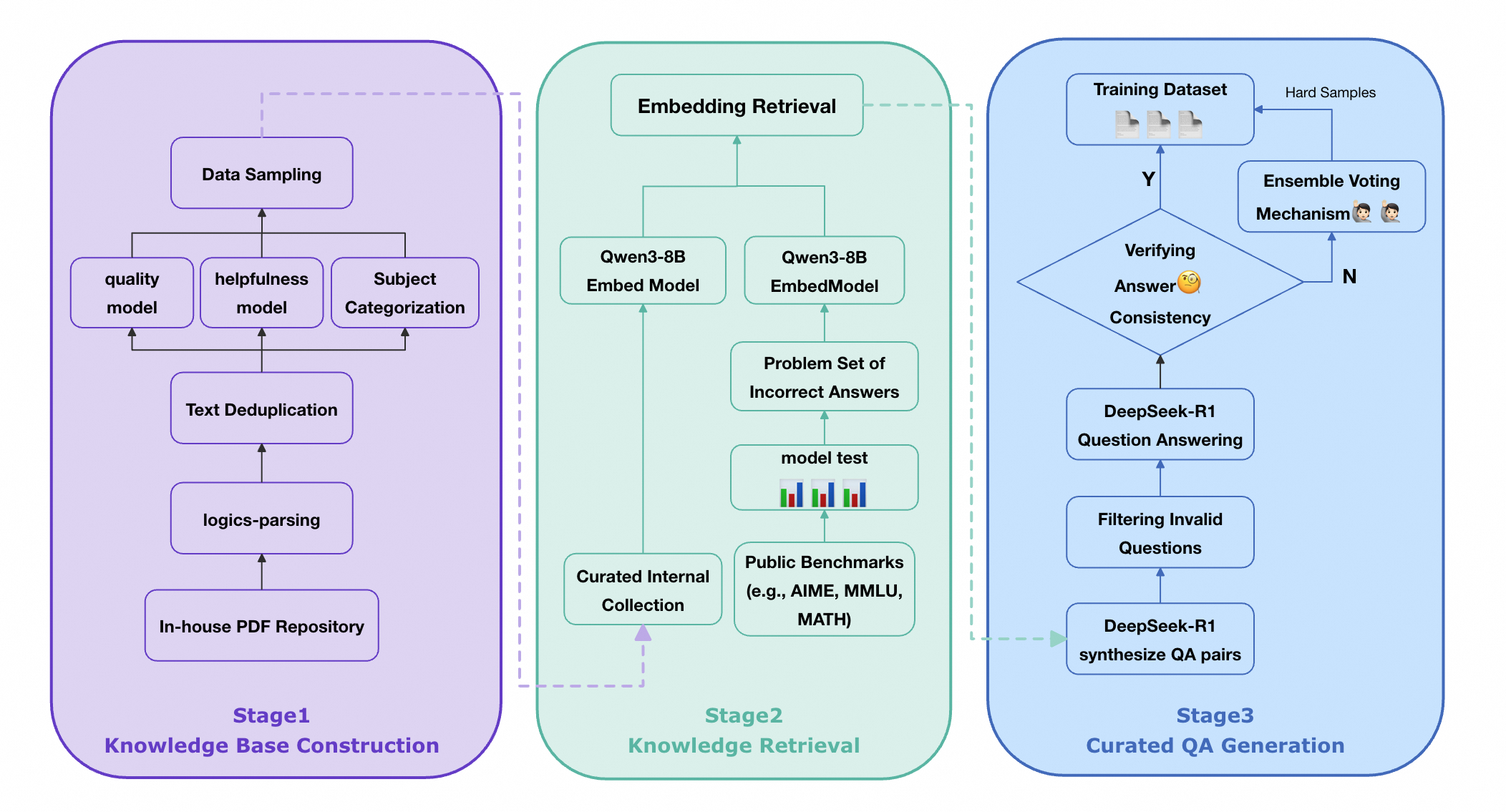

The central goal of the first-stage SFT is to build a diverse, effective, and scalable data engine that learns a proposal distribution $`P_0`$ tailored to reasoning tasks. To this end, we construct long CoT datasets that are rich in reasoning content and generalize well across a wide range of reasoning benchmarks to ensure the $`P_0`$ has a broad support. As shown in 2, our pipeline collects questions from selected sources and produces high-quality reasoning question-response pairs through a series of curation steps.

style="width:100.0%" />

style="width:100.0%" />

Data Curation Pipeline

Data Collection.

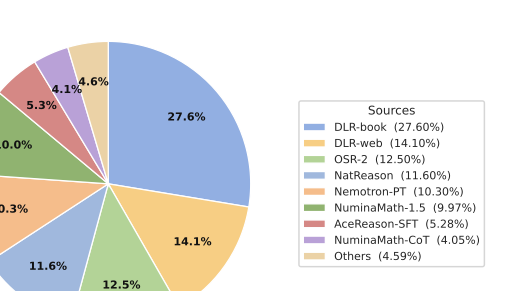

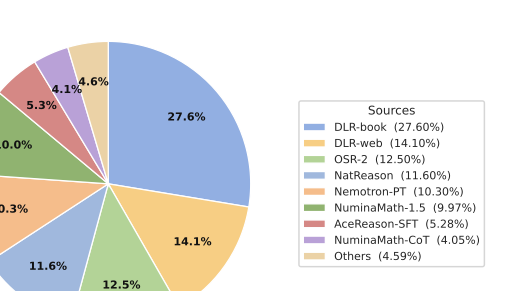

Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of open-source data. To fully leverage open-source data and ensure diversity, we aggregate questions from a wide range of highly regarded and frequently cited sources on Huggingface2, as listed in Appendix 7.1. For the purpose of preventing potential quality risks, all early synthetic subsets and multi-modal subsets are excluded. Additional, we utilize DEGISNER to incorporate synthetic datasets from books and webpages (DLR-Book and DLR-Web in ) to further scale dataset volume and enhance diversity. All PDF-format documents are parsed into plain text by Logics-Parsing and subsequently processed through the DESIGNER synthesis pipeline.

Annotation.

To unify data curation for the SFT and to further accommodate the subsequent RL with verifiable reward (RLVR) stages, we prompt Qwen3-235B-Instruct-25073 to annotate each sample (including question, meta-data, solution, and answer) across multiple dimensions: (1) whether the question is valid and unambiguous, (2) the discipline and domain associated with the question, (3) the educational level of the question, (4) the answer type, and (5) the verifiable answer (if exists). Samples that do not pass the validity and unambiguity check are subsequently filtered out. Details of annotation are provided in Appendix 7.2.

Deduplication.

To ensure diversity, deduplication is performed at multiple granularities, including both exact and near-duplicate removal. Firstly, we generate an MD5 fingerprint for each question and eliminate redundant samples with identical fingerprints across all sources. Moreover, we apply MinHash-based deduplication using 24 bands with a bandwidth of 10 to identify and eliminate near-duplicate samples. Specifically, within each group of samples sharing the same MinHash bucket, samples with valid questions and verifiable answers are prioritized for retention. Ultimately, approximately two-thirds of the data (about 10 million instances) are retained.

Decontamination.

We perform decontamination against the evaluation benchmarks to eliminate potential contamination in the training data, employing both MinHash-based and N‑gram based methods. Any training sample sharing the same MinHash bucket or an identical 13‑gram with evaluation samples is removed.

Response Distillation.

To balance computational efficiency and response accuracy,

Qwen3-235B-A22B-Thinking-25074 serves as the teacher model to distill

reasoning responses for each question. Generation configurations are

detailed in Appendix 7.3. To suppress systematic bias

during subsequent training, we discard responses that exhibit

degenerative repetition. Concretely, any response with an n-gram

duplication ratio exceeding a predefined threshold is excluded from the

training dataset. Optional further answer verification is conducted

using math-verify library5. In cases where responses do not match

the standard verifiable answers, the teacher model is employed to

regenerate the response once more. The strategy of filtering out

incorrect responses is not adopted, as empirical results indicate that

it leads to degraded performance, consistent with the conclusion of

OpenThoughts .

Weighted Stratified Sampling

Despite the implementation of extensive filtering strategies, the volume

of data generated by our pipeline remains a significant challenge for

model training, thereby necessitating further data sampling. Inspired by

OpenThoughts , we employ a difficulty-based weighted stratified

sampling strategy on STEM-related data to achieve a balance between

reasoning density and data diversity. Specifically, token length of the

response is adopted as a natural and effective proxy for question

difficulty. Our subsequent experiment corroborates the finding of

OpenThoughts that length-based sampling outperforms annotation-based

alternatives.

However, we further observe that purely length-based sampling leads to

degraded model performance on relatively elementary benchmarks (See

Section 5.2.1). To address this

issue, we adopt a stratified sampling strategy for data mixing. In

practice, we compute the quantiles of response token lengths and retain

all samples above the 75th percentile. Samples between the 50th and 75th

percentiles are downsampled by 50%, while those between the 20th and

50th percentiles are downsampled by 10%. This approach ensures a high

reasoning density within the training set while maintaining overall data

diversity.

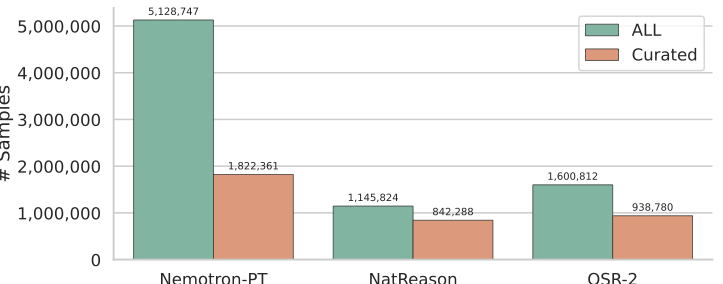

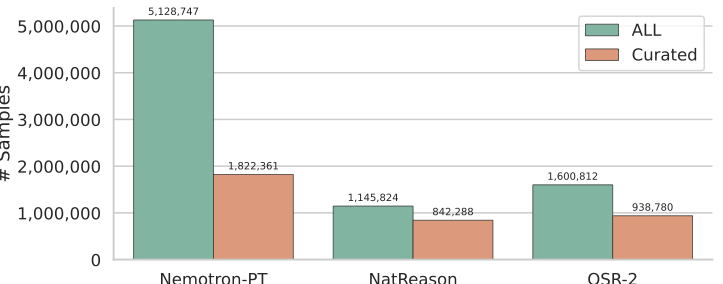

The curated Dataset Statistics

After these fine-grained steps, we obtain Logics-STEM-SFT-Dataset-7.2M before stratified sampling. To the best of our knowledge, it is among the largest open-source long chain-of-thought corpora that is high-quality, diverse, and most importantly, ready for direct use. The overall data flow is shown in 3. We further report the source dataset distribution in 5, and summarize dataset statistics before and after curation for the large-scale open-source sources in 4, highlighting our curation engine’s emphasis on both data quality and diversity. After stratified sampling, we obtain Logics-STEM-SFT-Dataset-2.2M, comprising 1.05M math samples and 1.14M broader-STEM samples distilled from a teacher model to preserve strong reasoning traces.

style="width:100.0%" />

style="width:100.0%" />

/>

/>

/>

/>

Failure-Driven Post-training via Knowledge Enhancement

The widely used post-training pipeline consists of two stages: SFT followed by second-stage RL. From our distribution-matching perspective (2), the second stage aims to better approximate the target distribution, and can be implemented via either SFT or RL. Accordingly, in this section we introduce a failure-driven post-training pipeline that is both effective and efficient. Our paradigm is theoretically grounded to better fit the gold-standard distribution for reasoning ability, and is sample-efficient as it correctly leans towards the regions that contribute most to distribution matching.

Algorithmic Design

First-stage Supervised Fine-tuning

Once the data are ready to use, we conduct the first-stage SFT. Considering the token-level decomposition and the supervised loss as the negative log-likelihood (NLL), the training will yield an optimized parameter $`\theta_1`$,

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:stage1-sft}

\theta_1=\arg\min_{\theta}\;\mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim P_0}\big[\ell_\theta(x,y)\big],

\quad

\ell_\theta(x,y)=-\sum_{t=1}^{T}\log \pi_\theta\!\left(y^t\mid x,y^{<t}\right).

\end{equation}where $`T`$ denotes the sequence length, $`\pi_\theta(y^t|x, y^{ Although SFT improves LLM performance by fitting the model to a proposal

distribution $`P_0`$, it remains limited on complex reasoning tasks,

especially high-difficulty, cross-domain STEM problems where models

often fail to produce correct answers. This problem reveals that there

is still a distance between $`P_0`$ and $`P^*`$. Thus, to solve the

mismatch between $`P_0`$ and $`P^*`$, we conduct a second-stage

post-training via the following steps: evaluation $`\rightarrow`$

knowledge retrieval $`\rightarrow`$ data synthesis $`\rightarrow`$

continued training. The evaluation helps us identify the regions

$`(x,y)`$ that cause high overall loss (failure regions). Once the

failure region is found, we retrieve from external documents for

knowledge enhancement and synthesize more query-response pairs to

provide more samples and compensate for the density ratio

in [eq:iw_grad_form]. Then, a

second-stage training is done to minimize $`\ell_\theta(x,y)`$ in that

region. After the first-stage SFT and obtaining $`\theta_1`$, the model has

already gained the basic information. To find the regions (i.e.,

query-response pairs) that the model underestimated (high density ratio

between $`P^*`$ and $`P_0`$) or highly biased (high sample-wise loss

$`\ell_\theta(x,y)`$), we evaluate the model on a distribution

constructed from gold-standard evaluation tasks (such as AIME2025 ,

MMLU etc.) denoted as a distribution $`Q`$, and collect failure cases

from this evaluation distribution. We define a failure function

$`w_{\theta_1}(x)\in\mathbb{R}_+`$ to evaluate the value of the current

sample to the model training, which in our implementation is a binary

indicator of verified incorrectness: This induces a failure-driven query distribution which increases the sampling probability of regions where the current

model performs poorly. Under the assumption that $`Q`$ is a proper

surrogate for $`P^*`$, we can show that the new query distribution can

better minimize the expected risk

in [eq:iw_grad_form]. We left the

proof in Appendix 9. Failure resampling alone does not explicitly provide missing knowledge,

as it cannot expand the support of $`P_0`$, and thus can only provide a

better approximation to the existing set. We therefore introduce an

external document corpus $`\mathcal{K}=\{d\}`$ to enhance the

second-stage training, where $`d`$ denotes the external knowledge

document instances. This external document corpus can be retrieved to

further scale up the training dataset. We formalize retrieval as sampling via a kernel. Let $`\varphi(\cdot)`$

be an embedding model and define similarity (via cosine similarity) as

$`s(x,d)=\langle \varphi(x),\varphi(d)\rangle`$, we can define the

conditional sampling distribution over external documents in the

knowledge base as where $`\tau`$ is the temperature to adjust the distribution. In

practice, to enhance the sparsity of retrieval to improve efficiency, we

use a top-$`k`$ truncated variant looks like: Intuitively, $`K_{\tau,k}(d\mid x)`$ specifies how likely a failure case

$`x`$ “activates” a related knowledge document $`d`$, thereby

transferring sampling mass from failure regions to their neighborhoods

in the knowledge space. Given a retrieved document instance $`d`$, we synthesize a new training

example $`(x',y')`$ via powerful LLMs such as DeepSeek R1 . We view

synthesis as another conditional kernel

$`G((x^\prime, y^\prime)\mid d)`$ and apply an acceptance filter

$`a(x^\prime, y^\prime)\in\{0,1\}`$ (e.g., answer-consistency

verification), yielding

$`G_{\mathrm{acc}}(x^\prime, y^\prime\mid d)\propto G(x^\prime, y^\prime\mid d)\,a(x^\prime, y^\prime)`$. Combining failure sampling, retrieval, and synthesis, we obtain the

synthetic data distribution: or equivalently, Thus, the second stage trains on a distribution that mixes

$`P_\text{syn}`$ and $`P_0`$ with percentage $`\lambda`$. Rather than

relying on implicit distribution matching via RL, we argue that SFT can

be used for explicit distribution matching in the second stage, yielding

the following training objective: Equivalently, this is done via sampling datapoints from $`P_0`$ and

$`P_\text{syn}`$ through a percentage of $`\lambda`$. We prove the

following theorem to show that, under mild conditions, the

failure-driven post-training yields better expected loss. Theorem 1 ((Informal) Failure-driven training minimizes the expected

loss.). *Let $`\nabla {\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta)`$ be the ideal target

graident, $`\nabla {\mathcal{L}}_{1}(\theta)`$ be the stage-2 gradient

under the synthetic distribution $`P_{1}`$, and

$`\nabla {\mathcal{L}}_0(\theta)`$ be the gradient under the original

distribution $`P_0`$. Assuming the gradient is normalized such that

$`\|\nabla {\mathcal{L}}_1(\theta)\|=\|\nabla {\mathcal{L}}_0(\theta)\|`$

and $`Q\approx P*`$, the failure-driven construction of $`P_1`$ makes

the gradients better aligned with the target gradient, i.e., Then, for sufficiently small learning rate $`\eta`$, one stage-2

optimization step using $`P_{1}`$ yields no larger target risk than

using $`P_0`$: The vanilla RL objective is Practically, we test our model using GRPO and DAPO , which we defer the

introduction in 4.2.4. We then introduce our engineering implementation. The central tenet of

second-stage training and data usage is to identify the underestimated

region from the failure cases and remediate them using external,

high-fidelity knowledge sources. This is done through three steps: 1)

knowledge base construction, 2) knowledge retrieval engine, and 3)

curated question-answer (QA) pair generation. The overall pipeline is

illustrated

in 7. Notably, data employed in the

second stage is generated automatically without any human annotation. We curated an internal multi-source PDF corpus encompassing academic

papers, technical monographs, authoritative textbooks, and technical

reports. To preserve both structural fidelity and semantic integrity, we

employed LogicsParsing(),a proprietary, high-precision PDF parsing tool,

to convert raw documents into structured HTML format. Subsequently, we

applied a multi-dimensional quality filtering mechanism: A text quality model evaluated linguistic fluency; A usefulness model quantified information richness; A fine-grained subject classification model assigned domain-specific

labels. Only documents exhibiting high fluency, high knowledge density, and

unambiguous domain specificity were retained, culminating in a

high-quality, structurally coherent knowledge base. We first evaluate the SFT model on multiple established STEM benchmarks,

including AIME2025 , MATH500, MMLU that works as the gold-standard

distribution $`Q`$. We then collect questions answered incorrectly as

“knowledge deficiency” samples. These erroneous instances are then

encoded into dense vector representations using the Qwen3-8B-Embed6.

Concurrently, every document in the knowledge base is embedded using the

same model. Leveraging a vector retrieval algorithm, we retrieve the

top-30 semantically most relevant documents for each incorrect question,

ensuring high topical, conceptual, or methodological alignment between

the query and retrieved content. Utilizing the DeepSeek-R1 as the synthesis kernel

$`G((x^\prime, y^\prime)\mid d)`$, we automatically generate two

Query-Response pairs per retrieved document, each requiring deep

reasoning based on the document’s core knowledge points and logical

structure. To guarantee answer accuracy and consistency, a

dual-verification mechanism is implemented to serve as the acceptance

filter: In the first pass, a question and a preliminary answer are generated

jointly; In the second pass, the model is prompted with the question alone to

generate an independent answer; Only samples yielding identical answers across both passes are

retained as high-confidence training instances. For inconsistent cases, we aggregate additional model responses and

applied a majority-voting mechanism to determine a consensus answer;

These samples are incorporated into the training set as “hard examples.”

Furthermore, the length of the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning trace

generate during the second answer synthesis serves as a proxy indicator

for difficulty, as longer CoT sequences typically signify more complex

reasoning steps and greater challenge. This criterion facilitates the

selection of high-difficulty samples, ensuring the training data not

only possesses high reliability but also effectively stimulates the

model’s potential for advanced reasoning. Through this rigorous

pipeline, we ultimately synthesize a dataset comprising approximately

30K high-quality, high-difficulty, knowledge-aligned QA pairs. This

dataset is subsequently used to train the SFT model, resulting in

substantial improvements in robustness and generalization on complex

reasoning tasks. We test GRPO and DAPO for our framework, which defines the policy

ratio $`r_{i, t}`$ and the renormalized advantage function

$`\hat{A}_{i}`$ as, We adopt the clip-higher strategy alongside batch-level reward

normalization. Specifically, for each $`x\sim P_1(x)`$, we sample

multiple $`\{y_i\}_{i=1}^G`$, and defines the In addition to the answer correctness reward as

in [eq:rl-binary], we add format

compliance and reasoning-length reward to the RL. We use the open-source framework ROLL to compute verified rewards. For

math problems, we use We observe that even when the final answer is incorrect, longer and more

explicit CoT traces often facilitate self-correction and gradual

convergence to the correct solution. Accordingly, we encourage deeper

reasoning by assigning a length-based reward: for incorrect answers, the

reward increases monotonically with the CoT length; for correct answers,

we grant the maximum length reward by default to avoid discouraging

concise yet correct reasoning. We also find that CoT generations can be

redundant. To improve diversity and information density, we incorporate

an $`n`$-gram–based repetition penalty into the reward. Formally, let $`A\in\{0,1\}`$ indicate answer correctness, $`\ell`$ be

the reasoning-trace length, and $`\ell_{\min},\ell_{\max}`$ be length

bounds. We define the normalized length score The final length-aware reward is $`r_{\text{len}} = s(T,A)\cdot \rho,`$

where $`\rho\in(0,1]`$ is a penalty factor computed from the $`n`$-gram

repetition rate of the generated text. With systematic experiments, we show that our framework not only yields

significant gains in reasoning accuracy on STEM benchmarks but also

establishes a novel, reproducible, transferable, and highly efficient

paradigm for data construction in the post-training phase. Models are evaluated on representative reasoning benchmarks spanning

mathematics and broader STEM disciplines. For mathematical reasoning, we

assess performance on AIME2024 , AIME2025, HMMT_Feb_2025, BRUMO2025,

BeyondAIME, and MATH-500. For remaining STEM domains, we adopt

GPQA-Diamond , R-Bench , MMLU-Pro , and CMMLU as benchmarks.

Particularly for MMLU-Pro and CMMLU, we select STEM-related subsets to

specifically evaluate the model’s reasoning capabilities in STEM fields,

as detailed in 7.4. To ensure statistical robustness and mitigate sampling variability, we

conduct $`N`$ independent generations for each test instance using

zero-shot evaluation, adhering to the generation configurations detailed

in 10 by default. For

reasoning-intensive benchmarks with a limited number of test instances,

such as AIME2024, AIME2025, BeyondAIME, HMMT_Feb_2025, and GPQA-Diamond,

we perform $`16`$ generations per case. In contrast, for elementary

benchmarks or those with a larger number of test instances, we use up to

$`4`$ generations per instance. Consequently, we report Pass@1 as the

primary evaluation metric, with additional Pass@K (also referred to as

Best@N) and majority-vote accuracy (Majority@N) as supplementary

metrics. Further details of evaluation settings are described in

8.1. As shown in [tab:3,tab:4], Logics-STEM-8B-RL

significantly outperforms other reasoning models of comparable size from

the community, scoring 90.42% on AIME2024, 87.08% on AIME2025, 74.79% on

HMMT2025, 62.5% on BeyondAIME and 73.93% on GPQA-Diamond. The

consistently strong performance across diverse benchmarks further

evidences the robust domain-generalization capacity of the proposed data

curation strategy, demonstrating the effectiveness of our SFT and RLVR

strategies. Notably, Logics-STEM-8B-SFT achieves reasoning performance comparable to

state-of-the-art open-source reinforcement learning models of similar

scale, such as Klear-Reasoner-8B. This finding demonstrates our ability

to fully leverage high-quality reasoning datasets and further suggests

that, for models of small size, knowledge distillation through SFT can

be as effective as RL-centric post-training. Moreover, as evidenced by the substantial improvements in the

Majority@N on competition-level benchmarks shown in

3, the application of RLVR after supervised

fine-tuning (SFT) significantly enhances model reasoning ability by

further concentrating the probability distribution around correct

answers, even when SFT has already established a strong baseline. As explained in

3.2, further sampling over

the massive outputs of the curation pipeline is essential. Therefore we

conduct a series of ablation experiments to identify the most effective

sampling strategy. Specifically, for each sampling strategy, we

uniformly sample 200K records to construct the training set and

fine-tune the model for one epoch. Length-based sampling has been demonstrated to be an effective sampling

method ; nevertheless, our experiments demonstrate that its exclusive

use degrades the model’s elementary reasoning and generalization

capacities, as reported in

4. the ablation model trained solely

with length-based sampling incurs significant performance drops on

MATH500, MMLU-Pro-Math, and GPQA-Diamond, despite notable gains on

AIME2024, AIME2025, and HMMT2025. Another set of ablation experiments focuses on variants of stratified

sampling. We explore sampling based on the token length of response

generated by the teacher model and the annotated education level of the

question. The results in Table

4 demonstrate that the former serves as

a natural and more effective proxy for question difficulty. We therefore adopt length-based stratified sampling to mitigate

catastrophic forgetting of elementary reasoning capabilities, while

scaling the training set to strengthen advanced reasoning capabilities. To investigate how different types of benchmark-recall document

synthesis affect second-stage training, we construct training data using

two representative benchmarks: (i) Scientific QA (e.g., GPQA), (ii)

Mathematical reasoning (e.g., Math500, AIME2024/2025, and HMMT).

Following a unified data construction pipeline, we generate second-stage

training samples from incorrectly answered questions in these benchmarks

and train models independently. Experimental results demonstrate that

training data synthesized from GPQA errors not only significantly

improves GPQA evaluation performance but also delivers notable

generalization gains across mathematical reasoning benchmarks (e.g.,

AIME, HMMT). In contrast, training data derived solely from mathematical

benchmarks yields limited improvement in overall STEM capabilities. This finding suggests that the complex reasoning patterns inherent in

scientific QA tasks may possess stronger cross-domain transferability,

making them more valuable for enhancing general reasoning abilities. In this section, we examine how different settings and modules influence

the RLVR training process. We present ablation experiments with detailed

results and demonstrate how they inform the design of our final training

recipe. Our experiments cover different loss functions, including Group Relative

Policy Optimization (GRPO) (), Decoupled Clip and Dynamic Sampling

Policy Optimization (DAPO) (). We first conduct ablation studies on Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct using the

DAPO-Math-17K dataset and find that employing the DAPO objective in

conjunction with Reinforce++ as the advantage estimator yields more

stable and consistent improvements. As shown in

6, an early ablation indicates

that the DAPO loss function outperforms the GRPO Loss on our SFT model.

Therefore, the DAPO objective coupled with Reinforce++ as the advantage

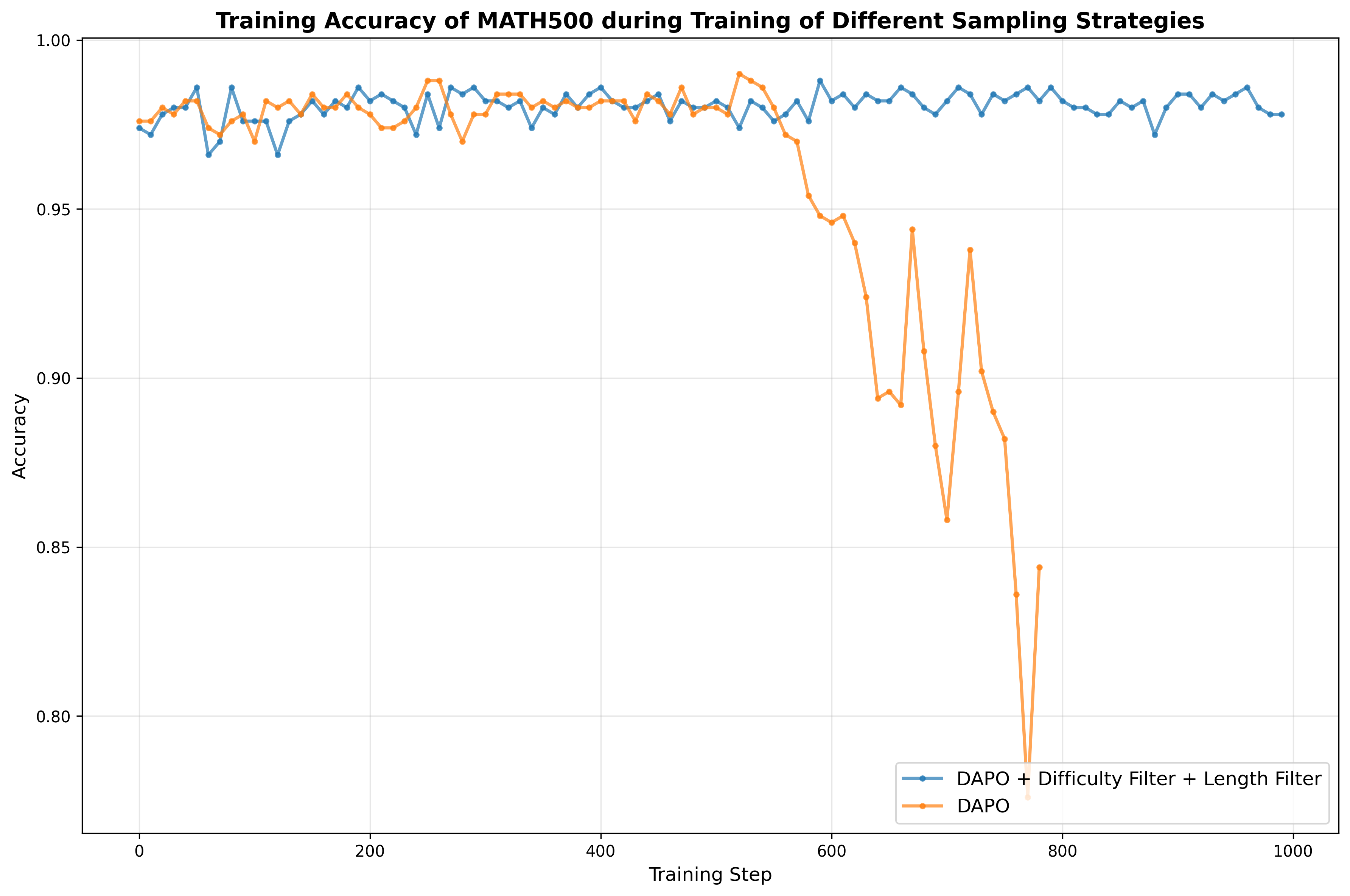

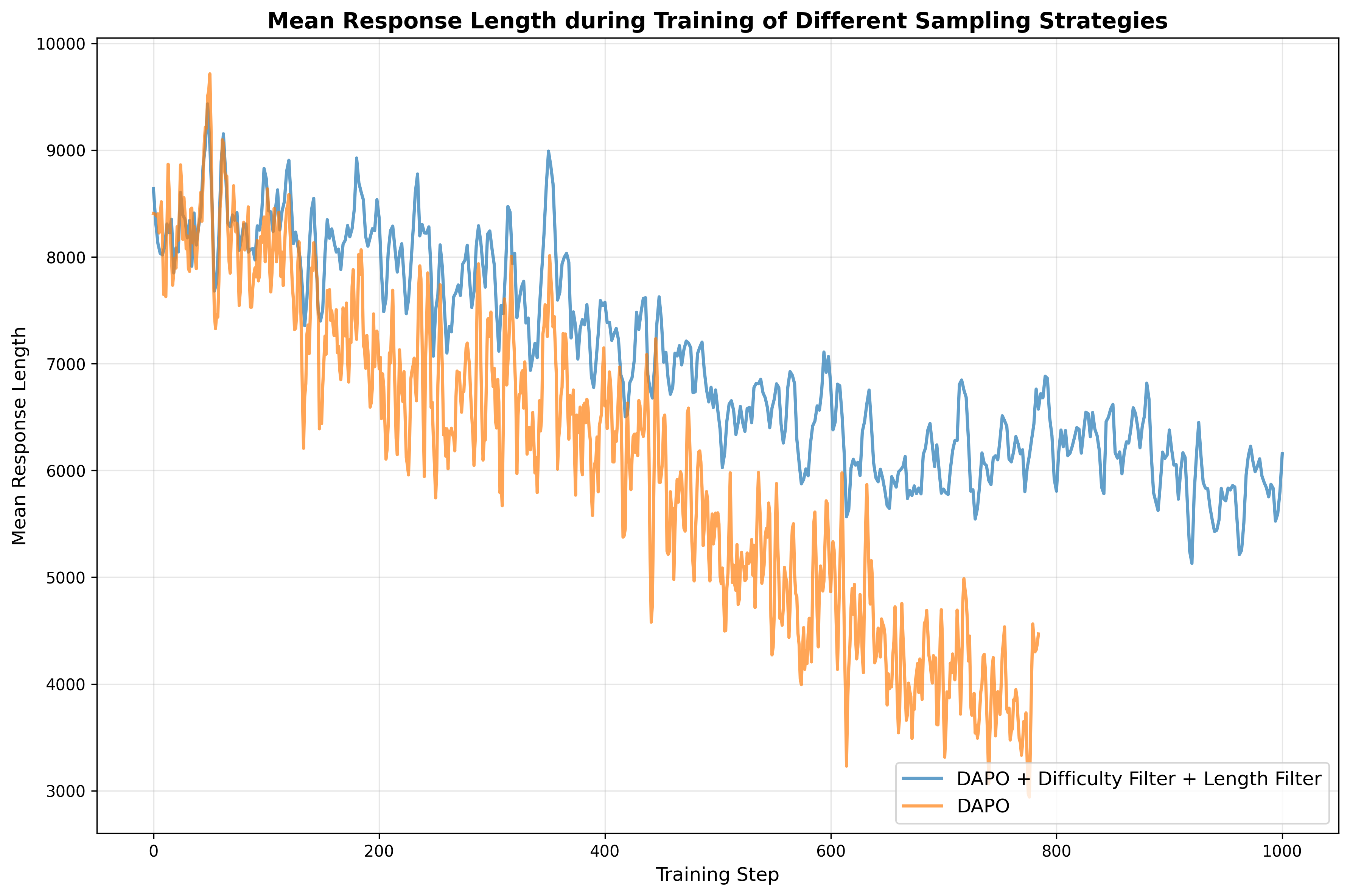

estimator is adopted as the final algorithm. Following , we take advantage of dynamic data sampling strategy in our

training pipeline. Specifically, we first drop the responses that are

longer than our default maximum length, it is called overlong length

filter. Also, for the difficulty filter, for each prompt, we will

calculate the average score within the group of all its responses, if it

is lower or greater than our set threshold, the data will not be

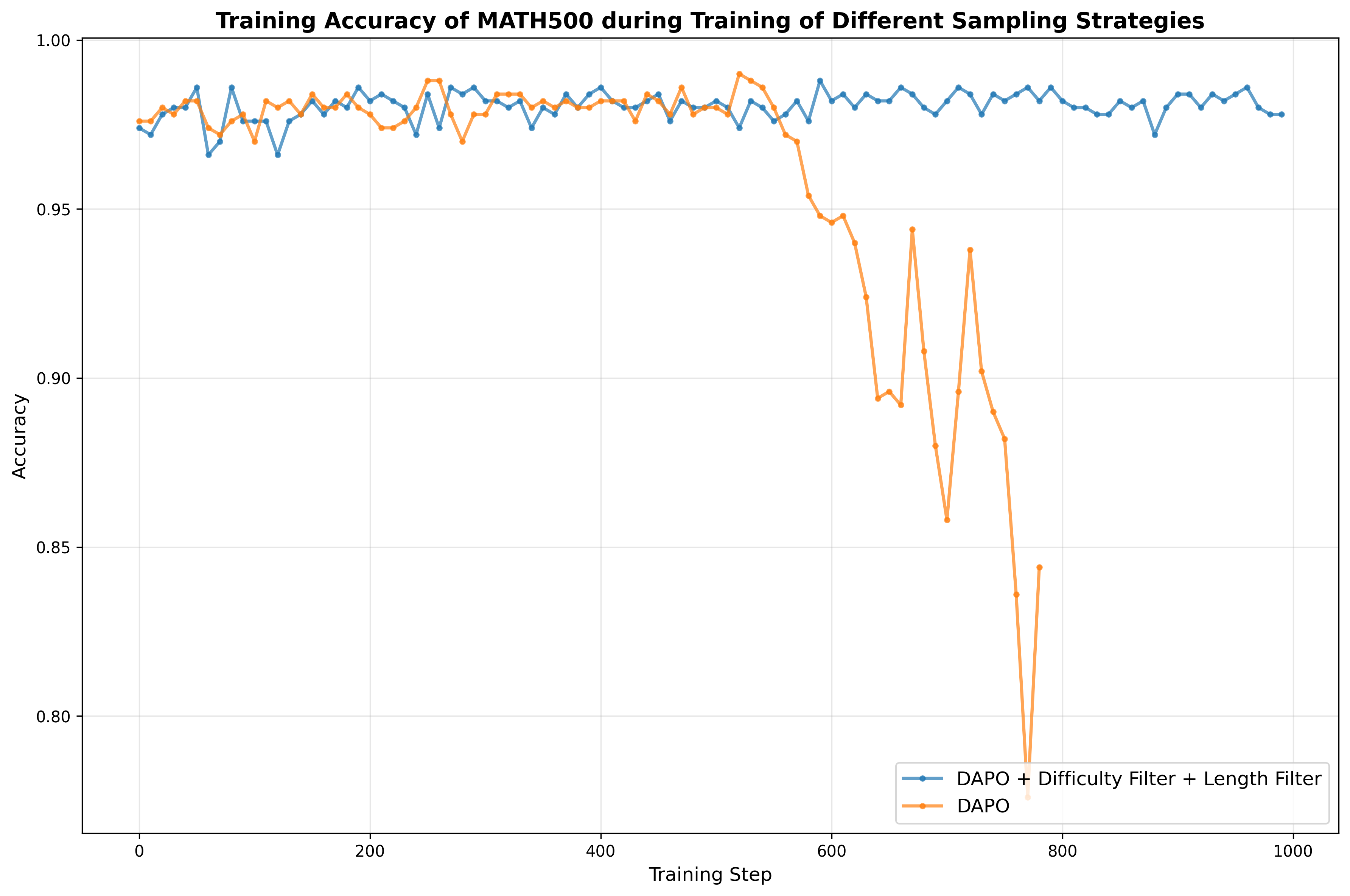

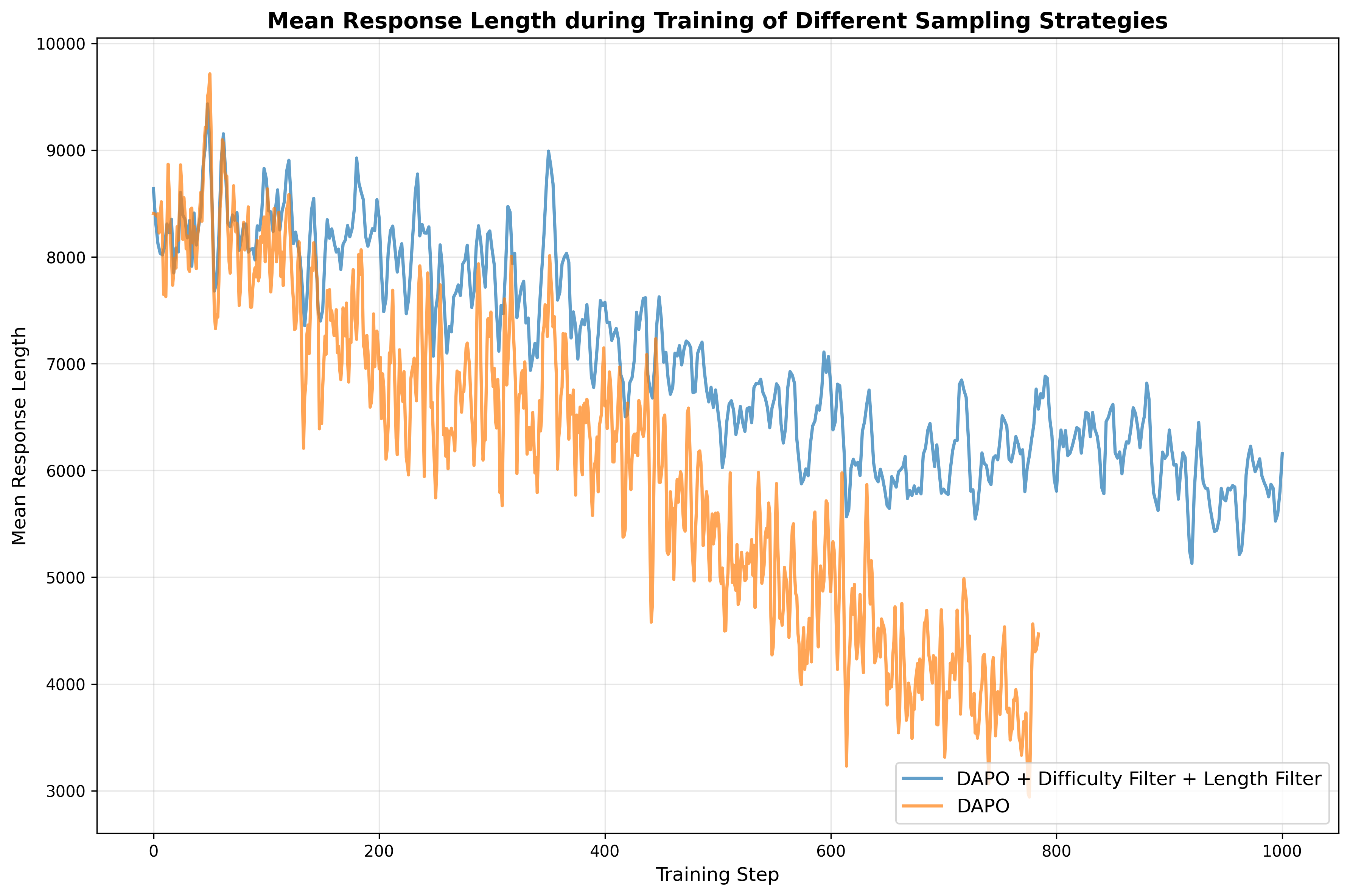

involved in the calculation of loss function. In this experiment, we conduct two groups of trials: one using our

original setting (with both the overlong-length and difficulty filters

enabled), and the other with both filters disabled. We set the lower and

upper thresholds for the average response score to 0.1 and 0.95,

respectively. As we can observe in

8, the group without a filter

tends to collapse in both the training accuracy and response length in

an early stage. Our analysis indicates that response groups with average scores that are

either too high or too low yield near-zero advantage values after

normalization, which in turn results in negligible or zero gradient

updates. Intuitively, such samples are either too “easy” or too “hard”

for the current model and provide little useful signal for learning.

Additionally, without the overlong-length filter, responses exceeding

the maximum allowed length are truncated, making it difficult to extract

the final output and leading to a short response length. Consequently,

both the overlong-length filter and the difficulty filter are essential

to ensure stable and effective training. Experimental results demonstrate that incorporating the reasoning-length

reward and repetition penalty mechanisms yields significant performance

improvements ranging from 2 to 3 percentage points on benchmark

datasets, including AIME2025, HMMT, and CMMLU. Consistent, albeit

modest, gains are also observed across all other evaluated benchmarks. In addition to the superior performance achieved by the model fine-tuned

from Qwen3-8B (as presented in

5.1.3), we also experiment with several

other models as initial models during the supervised fine-tuning (SFT)

stages. All of these experiments further confirm the effectiveness of

our data engine, as shown in 8. Firstly, we fine-tune Qwen3-8B-Base with the identical

Logics-STEM-SFT-2.2M dataset. The resulting model performs on par with,

though marginally weaker than, Logics-STEM-8B-SFT while substantially

surpassing Qwen3-8B. These gains demonstrate that our dataset is

sufficiently diverse and of high quality to support full-scale

supervised fine-tuning (SFT) in the STEM domain. Additionally, we evaluate the scalability of our approach by fine-tuning

Qwen3-32B. Remarkably, the resulting model, Logics-STEM-32B-SFT, still

exhibits substantial improvements in reasoning performance, further

corroborating the high quality of our dataset. In addition to the RLVR experiments, we conduct continual SFT

experiments using failure-driven synthetic data to assess the universal

effectiveness of the data across different post-training paradigms.

Analogous to the RLVR training setup, we conduct experiments on

Logics-8B-SFT, with training hyperparameters detailed in the Appendix.

To mitigate catastrophic forgetting, we experimentally construct

mixtures of 34K failure-driven synthetic data and existing SFT training

data at varying ratios. Notably, under an approximately 1:1 mixture of

failure-driven synthetic data and existing SFT data, the model achieves

improvements comparable to those obtained with the RLVR approach, as

presented in 9 . Due to different evaluation settings in officially reported results that

limit direct comparisons across models, we systematically assess the

effect of inference budget by independently evaluating each model under

varying context settings. As illustrated in [tab:3,tab:4], scaling up inference

budget from 32K context to 64K context leads to significant improvements

on competition-level benchmarks such as AIME2024, AIME2025, and

HMMT2025, whereas improvements on elementary benchmarks remain modest.

The observation is consistent with the intuition that more challenging

problems require deeper deliberation. Moreover, reasoning-oriented

models typically benefit more from the additional inference budget than

the vanilla Qwen3-8B baseline. In an experiment, we apply reinforcement learning on DAPO-Math-17k, a

dataset that exclusively contains numeric verifiable answers. We observe

a marked deterioration in the model’s instruction-following ability,

specifically in its capacity to respond with option letters as

instructed, which leads to significant performance degradation on

GPQA-Diamond, R-Bench, and MMLU-Pro-STEM. This observation explains the

poor performance of Klear-Reasoner-8B on these benchmarks (See

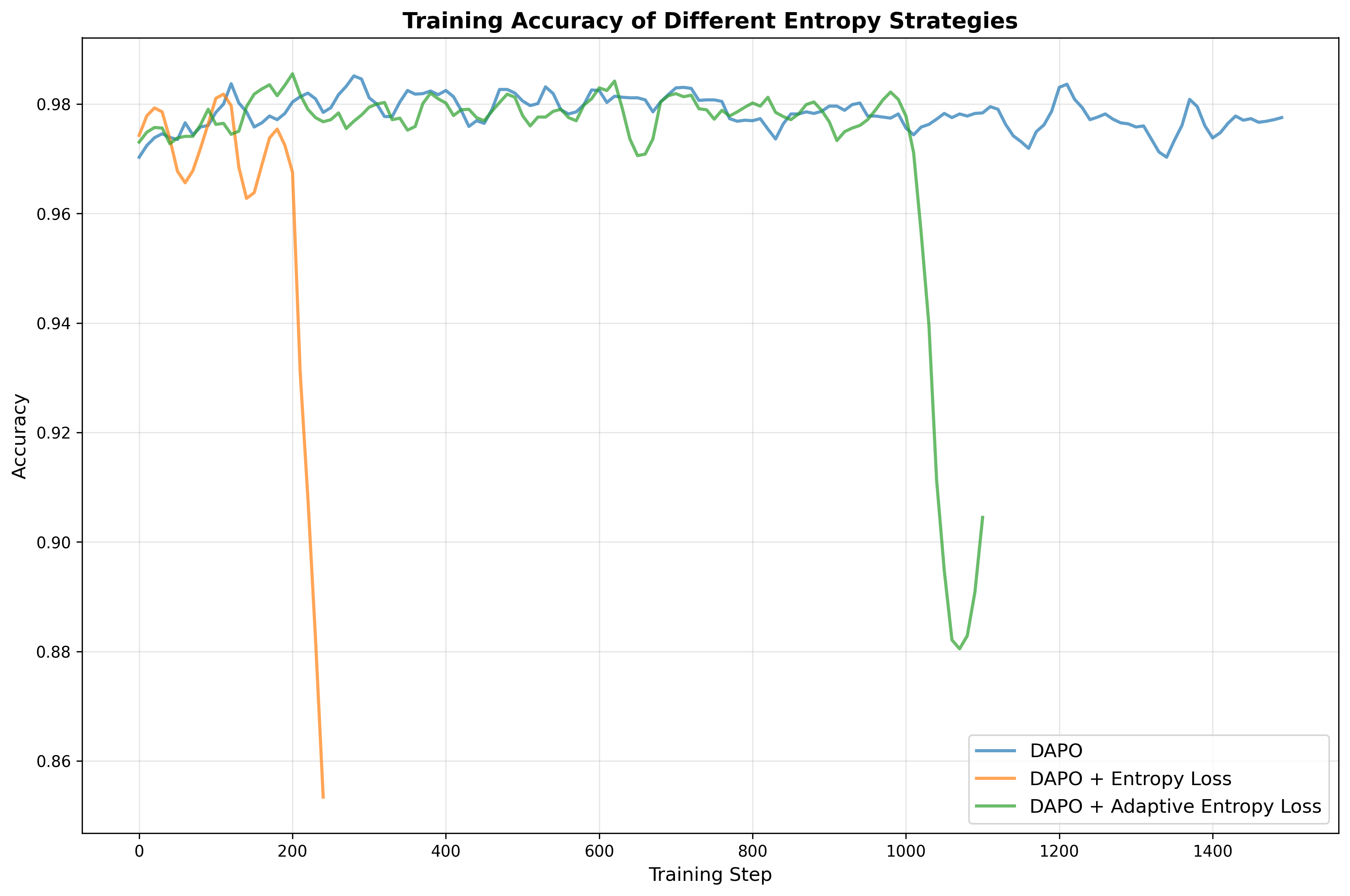

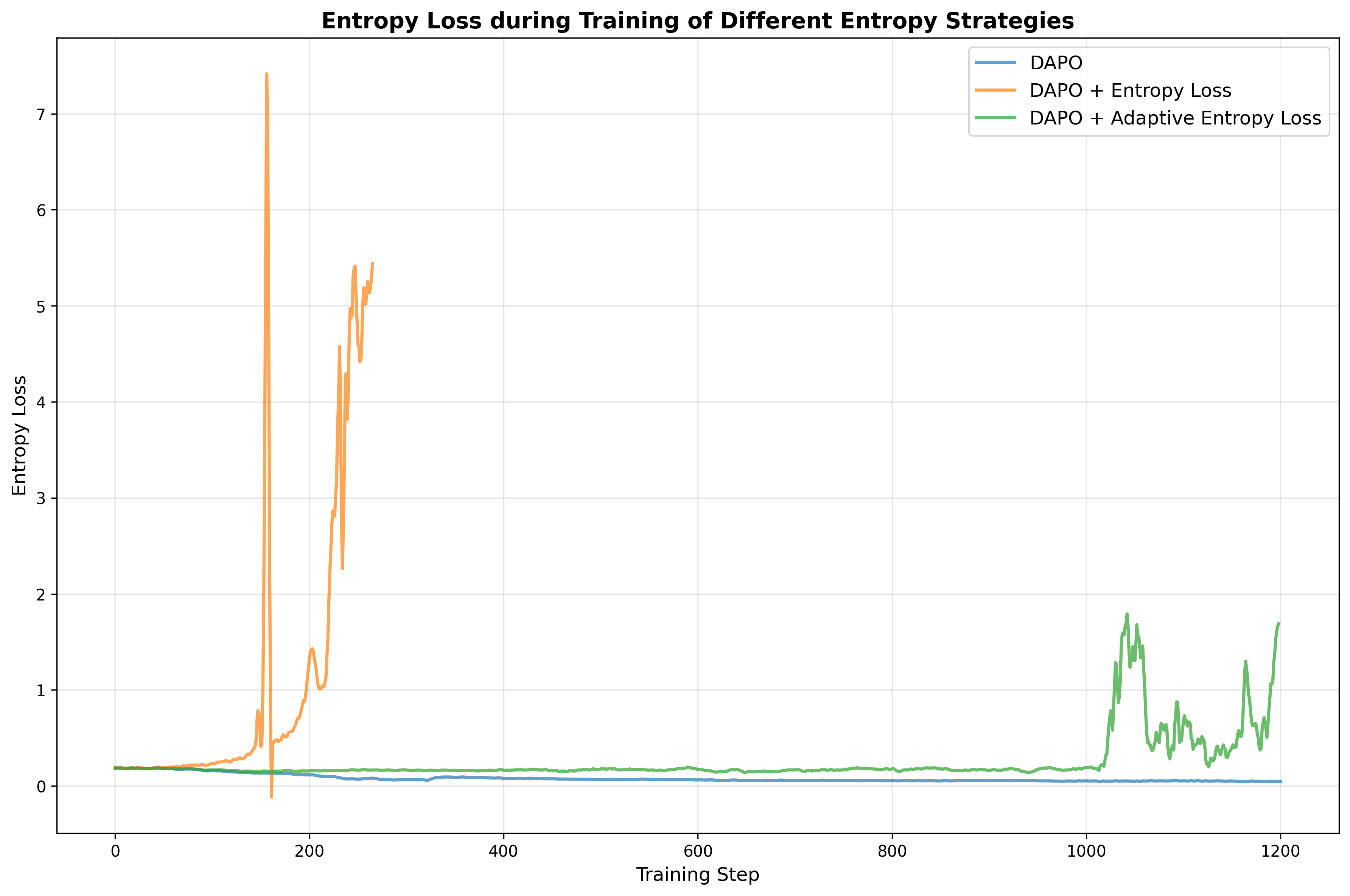

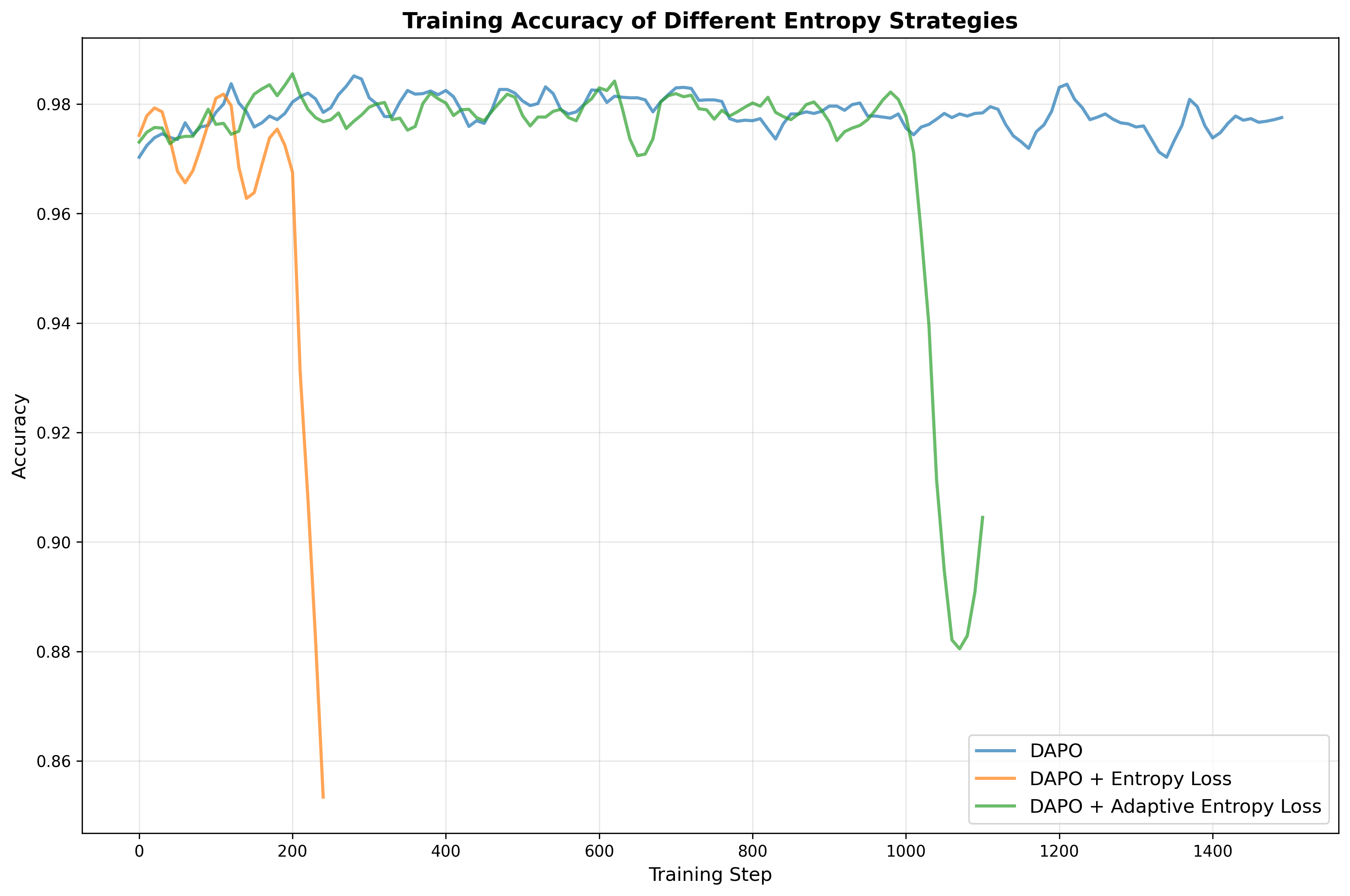

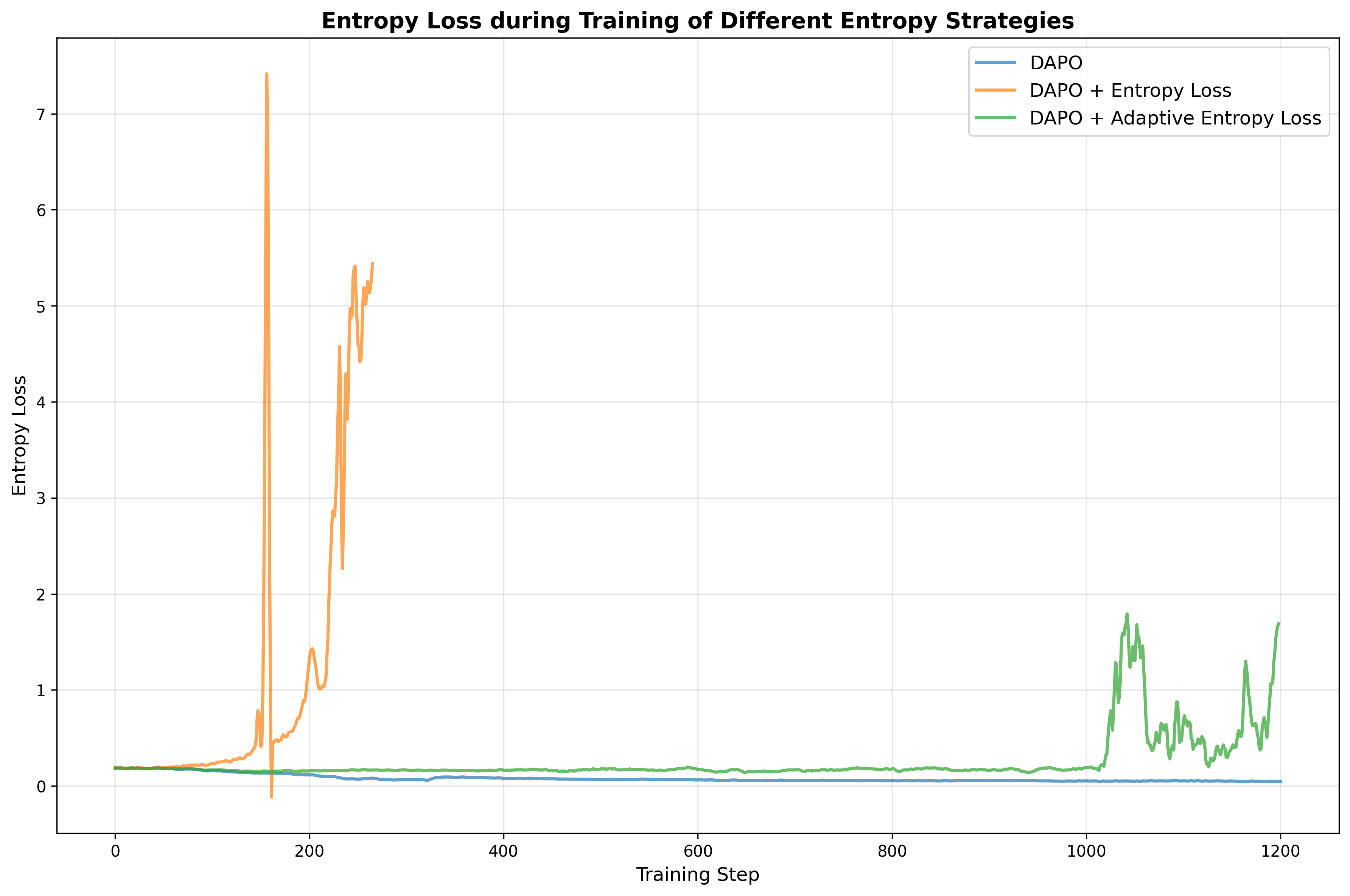

2). In our ablation study, we compare training objectives with and without

an entropy loss term, and we also explore adaptive entropy control

following the approach of , in which we stick to their hyperparameter

setting. Our experiments show that either incorporating a naive entropy

loss or implementing adaptive entropy loss requires careful

hyperparameter tuning and is prone to causing entropy explosion, as

illustrated in

9. Consequently, we exclude this

term from our final training recipe. We further investigate scaling the volume of failure-driven synthetic

data by relaxing the relevance threshold to retrieve more educational

documents associated with each failure case. However, as detailed in

[{appendix: scale

failure-driven}], this actually degrades the model’s performance. We

hypothesize that the additional documents are less strongly related to

the original failures, thereby breaking the expected scaling behavior. This technical report introduces Logics-STEM, a state-of-the-art

reasoning model specifically designed for STEM-related domains. Through

proposed data curation pipeline combined with the difficulty-based

stratified sampling strategy, we effectively select high-quality

reasoning data from both open-access sources and synthetic datasets,

thereby ensuring robust supervised fine-tuning. The further integration

of failure-driven post-training and complementary dynamic sampling leads

to substantial improvements in reasoning performance. For future work,

we plan to further investigate reinforcement learning techniques, scale

the model to larger architectures, and extend its capabilities to a

broader range of tasks, including coding and tool-integrated reasoning. We collect questions from the following highly regarded and frequently

cited datasets: NuminaMath1.5 (), OpenThoughts3 (), Mixture-of-Thoughts

(), AceReason-1.1-SFT (), AceReason-Math (), OpenScienceReasoning-2

7, OpenMathReasoning (), Llama-Nemotron-Post-Training-Dataset (),

DLR-Web (), DLR-Book (), Skywork-OR1-RL-Data (), NaturalReasoning (),

DeepMath-103K (), DAPO-Math-17k (), TheoremQA (), JEEBench (), GPQA-Main

(), GSM8K (), AIME 8, AMC 9, s1-teasers (), s1-probs (),

openaimath (). We structure and organize our reasoning data according to the following

dimensions: Questions are considered invalid and excluded from subsequent curation

if they: (1) lack required images; (2) is incomplete; (3) is

unsolvable. Data are categoried into 6 domains: Math, STEM(excluding Math),

Humanities&SocialScience, Business, Medicine&Biology, Code. Data are categorized by educational level into six tiers: elementary,

junior-secondary, senior-secondary, undergraduate, graduate, and

competition. Answer types are taxonomized as Boolean, multiple-choice, numeric,

vector/matrix, interval, expression, string, proof, textual

explanation, or other. In a narrow sense, verifiable answers include

only multiple-choice and numeric types, while in a broader sense,

verifiable answers further encompass Boolean, vector/matrix, interval,

and expression types. We adopt the recommended configuration parameters provided by Qwen team

for both response distillation and evaluation inference, as detailed in

10. Generation configuration for response generation

As described in Section 3.3, we select STEM-related subsets from

MMLU-Pro and CMMLU to evaluate the model’s reasoning capabilities in

STEM domains. To ensure consistency, we employ a uniform zero-shot evaluation protocol

across all benchmarks, where the model is instructed to enclose its

final answer within $`\backslash`$ Example Two quantum states with energies E1 and E2 have a lifetime

of $`10^-9`$ sec and $`10^-8`$ sec, respectively. We want to clearly

distinguish these two energy levels. Which one of the following options

could be their energy difference so that they can be clearly resolved? For other benchmarks, the following template is adopted: Example Let $`p`$ be the least prime number for which there exists a

positive integer $`n`$ such that $`n^{4}+1`$ is divisible by $`p^{2}`$.

Find the least positive integer $`m`$ such that $`m^{4}+1`$ is divisible

by $`p^{2}`$. We extract the answer from the For each test instance, we calculate three metrics as following: Pass@1 is defined as the average accuracy across $`N`$ rollout

samples. Best@N is assigned a value of 1 if any of the $`N`$ rollout

samples matches the gold answer, and 0 otherwise. Majority@N is assigned a value of 1 if the majority answer among

the $`N`$ rollout samples matches the gold answer, and 0 otherwise. Consequently, we report the evaluation result of each benchmark as the

average of the evaluation metrics computed over all test instances. Hyperparameters we use are listed in [tab:Hyperparam

for SFT,tab: hyperparam for rlvr,tab:Hyperparam for Continual SFT]. Hyperparameters for Supervised Fine-Tuning(SFT)

Hyperparameters for Reinforcement Learning with Verified Rewards(RLVR)

Hyperparameters for Continual Supervised Fine-Tuning(SFT)

We experiment with various entropy-based strategies but failed to

achieve a stable entropy loss or consistent improvements in accuracy

while training, as shown in

9. As described in

5.6, the volume of

failure-driven synthetic data is scaled to 150K. Fine-tuning the model

on a 1:1 mixture of these 150 K synthetic instances and 150 K existing

SFT examples yields the results reported in

14, where we observe

gains only on BeyondAIME and GPQA-Diamond accompanied by performance

drops on all other benchmarks, despite the increased number of training

steps. Consider a model trained by empirical risk minimization (ERM) on the

stage-1 training distribution $`P_0`$: However, our real goal is to minimize the risk under the (unknown)

target distribution $`P^*`$: We can decompose $`P(x,y)=P(x)P(y\mid x)`$, which gives a good

interpretation. In general, $`\hat{\theta}_0 \neq \theta^*`$ because the underlying

measure in the expectation changes from $`P_0`$ to $`P^*`$. This

mismatch manifests in several common failure modes: (1) Covariate/domain shift. The input marginal differs, i.e.,

$`P_0(x)\neq P^*(x)`$, so regions that are frequent under $`P^*`$ may be

rarely sampled under $`P_0`$. When the support overlaps, the target risk

admits an importance-weighted form which highlights that large density ratios $`\frac{P^*(x,y)}{P_0(x,y)}`$

correspond to regions that are under-covered by $`P_0`$ but can dominate

the target risk. (2) Support mismatch. A more severe problem occurs when there exists

a region $`\mathcal{A}`$ such that meaning that the target distribution assigns non-zero mass to inputs

never seen during stage-1 training. In this case, ERM on $`P_0`$ cannot

provide guarantees on $`\mathcal{A}`$. This would cause a extremely

large density ratio. (3) Underweighting high-loss regions. Even if $`P_0`$ and $`P^*`$

share support, uniform sampling under $`P_0`$ may assign very small

probability mass to difficult, high-loss examples. As a result, a large

fraction of gradient updates is spent on “easy” regions, while errors

concentrated in a small but critical subset (often over-represented in

target benchmarks) remain insufficiently optimized. (4) Conditional shift in outputs. Finally, the conditional

distribution can differ, i.e., $`P_0(y\mid x)\neq P^*(y\mid x)`$, which

in LLM post-training often appears as differences in solution style,

chain-of-thought structure, or answer formatting. Such mismatches can

lead the model to learn a behavior prior that is misaligned with the

target tasks. Our second-stage data construction explicitly targets these issues by

inducing a new training distribution $`P_{\mathrm{syn}}`$ from model

failures observed on a target set $`Q`$ (ideally, $`Q\approx P^*`$).

Failure-driven resampling shifts training focus toward regions where the

current model performs poorly under the target distribution, mitigating

covariate shift and the underweighting of high-loss regions. Moreover,

embedding-based retrieval defines a kernel which maps failure queries to relevant external documents. By

synthesizing new training instances conditioned on the retrieved

documents, we effectively expand the support of the training data,

addressing support mismatch by assigning non-zero probability to regions

that were absent in $`P_0`$. Finally, the synthesis prompts and

verification filters allow us to better align output formats and

reasoning traces with target requirements, partially reducing

conditional shift. Theorem 2 (Failure-driven training minimizes the expected loss.).

*Let $`\nabla {\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta)`$ be the ideal target graident,

$`\nabla {\mathcal{L}}_{1}(\theta)`$ be the stage-2 gradient under the

synthetic distribution $`P_{1}`$, and $`\nabla {\mathcal{L}}_0(\theta)`$

be the gradient under the original distribution $`P_0`$. Assuming the

gradient is normalized such that

$`\|\nabla {\mathcal{L}}_1(\theta)\|=\|\nabla {\mathcal{L}}_0(\theta)\|`$

and $`Q\approx P*`$, the failure-driven construction of $`P_1`$ makes

the gradients better aligned with the target gradient, i.e., Then, for sufficiently small learning rate $`\eta`$, one stage-2

optimization step using $`P_{1}`$ yields no larger target risk than

using $`P_0`$: provided that: 1) The evaluation distribution $`Q`$ sufficiently covers

the target distribution and mimics $`P^*`$ around the failure region; 2)

The synthesis kernel $`G(y'|d)`$ correctly mimic $`P^*(y\mid x)`$ and 3)

the retrieval kernel $`K(d\mid x)`$ correctly obtain samples similar to

$`x`$.* We partition the data space based on the performance of the current

model $`\theta`$: Success Region ($`\mathcal{S}`$):

$`\mathcal{S} = \{x \mid w_{\theta}(x) = 0\}`$. The model predicts

correctly and the loss is negligible. Failure Region ($`\mathcal{F}`$):

$`\mathcal{F} = \{x \mid w_{\theta}(x) = 1\}`$. The model fails; loss

is high. Let $`y^*(x)`$ denote the ground truth label (from $`P^*`$) for input

$`x`$. We assume that in the success region $`\mathcal{S}`$, the model

is well-converged. The expected gradient is dominated by zero-mean

noise: Consequently, the target gradient is determined by the failure region.

Let $`\mathbf{v}^*`$ be the average gradient direction required to fix

the failures: Let the synthetic gradient be

$`\mathbf{v}_{\mathrm{syn}} = \mathbb{E}_{P_{\mathrm{syn}}}[\ell_\theta(x,y)]`$,

and assume a similarity factor $`\alpha > 0`$: Then we are able to compare the alignment of the vanilla gradient

$`\nabla {\mathcal{L}}_0`$ and the failure-driven gradient

$`\nabla {\mathcal{L}}_1`$ with the target gradient

$`\nabla {\mathcal{L}}^*`$. The original training distribution $`P_0`$

is dominated by easy samples. Let $`\varepsilon= P_0(\mathcal{F})`$ be

the proportion of failure cases in the original dataset, we have The inner product with the target gradient is: Then, recall $`P_1 = \lambda P_0 + (1-\lambda) P_{\mathrm{syn}}`$. The

synthetic distribution $`P_{\mathrm{syn}}`$ concentrates mass on

$`\mathcal{F}`$ and generates gradients $`\mathbf{v}_{\mathrm{syn}}`$. The inner product with the target gradient is: Substituting

$`\nabla {\mathcal{L}}^* \approx P^*(\mathcal{F})\mathbf{v}^*`$: From Eq. equation [eq:align_g0] and

Eq. equation [eq:align_g1], it is realistic to

assume $`\alpha \ge \varepsilon`$, then which implies that Remark. The inequality holds when

$`\alpha \ge \varepsilon\approx P_0(\mathcal{F})`$, where $`\alpha`$ is

the similarity factor between synthetic gradient and true gradient

(typically high approximating 1), and $`P_0(\mathcal{F})`$ is the error

rate on the training set (typically very low (e.g., $`<0.1`$) as the

model fits the training data). $`\alpha`$ is determined by cetrain

properties of $`Q`$, $`K`$ and $`G`$, which we discussed as, $`Q`$ has to approximate $`P^*`$. When $`Q \approx P^*`$, the

evaluation distribution $`Q`$ effectively covers the target failure

region, i.e., $`Q_{\theta}(\mathcal{F}) \approx 1`$. $`K`$ has to correctly retrieve the relevant documents. So the

retrieved $`z`$ are close to $`x`$ around the failure region. $`G(x,y\mid d)`$ jointly need to be close to $`P^*(x,y)`$ and

$`G(y'|d,x)`$ produces synthetic labels $`y'`$ that provide a

descent direction aligned with the ground truth, i.e.

$`y^\prime (x) \approx y^*(x)`$. If retrieval is irrelevant or

synthesis hallucinates (invalid $`K, G`$), then $`\alpha \le 0`$

in [eq:kernel_validity], and

the method fails. Lemma 4 (Gradient alignment yields larger one-step decrease of the

target risk). *Let

$`{\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta)=\mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim P^*}[\ell_\theta(x,y)]`$

be the target risk. Assume $`{\mathcal{L}}^*`$ is $`L`$-smooth, i.e.,

for all $`\theta,\theta'`$, Consider two update directions $`g_0`$ and $`g_1`$ at the same parameter

$`\theta`$, and define the updates If the step size satisfies $`\eta\le 1/L`$ and the two directions have

the same norm $`\|g_0\|=\|g_1\|`$, then In particular, among update directions of the same norm, a larger inner

product with the target gradient (i.e., better alignment) guarantees a

smaller target risk after one step.* Proof. Consider a single gradient-based update where $`g`$ is the update direction. Using a first-order Taylor

approximation of $`L^*`$ around $`\theta`$ yields Eq. equation [eq:taylor_first_order] shows

that, for a fixed step size $`\eta`$, the target risk decreases more in

one step when the inner product $`\langle \nabla L^*(\theta), g\rangle`$

is larger. Assume that $`{\mathcal{L}}^*`$ is $`L`$-smooth (i.e., its gradient is

$`L`$-Lipschitz). Then the descent lemma gives: Therefore, for the same step size $`\eta`$, if

$`\langle \nabla {\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta), g_0\rangle \leqslant\langle \nabla {\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta), g_1\rangle`$

makes the update reduce the target risk more effectively, i.e., For stage-2 SFT we typically take Substituting ends the proof. Our failure-driven post-training framework can be naturally extends to

reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards (RLVR). We first show

that RL (with KL regularization) can be viewed as distribution matching

towards a reward-tilted target distribution, and that failure-driven RL

further improves the match to the gold distribution $`P^*`$ by

correcting the mismatch. Let $`\pi_\theta(y\mid x)`$ denote the current policy and

$`\pi_0(y\mid x)`$ be a reference policy (the stage-1 SFT model), which

serves as a strong proposal distribution with broad support. Consider

the following KL-regularized RL objective : where $`A(x,y)`$ is the advantage of some verifiable reward (e.g.,

correctness/format/length), and $`\beta>0`$ controls the strength of the

KL penalty. For any fixed $`x`$, the maximizer

of [eq:kl_rl_objective] admits a

closed form: [eq:reward_tilted_optimal_policy]

shows that KL-regularized RL performs an exponential tilting of the

proposal $`\pi_0`$ by the advantage, thereby inducing an implicit target

conditional distribution. Moreover, [eq:kl_rl_objective] is

equivalent to a KL-based distribution matching problem: Therefore, a second-stage RL procedure can be interpreted as pushing

$`\pi_\theta(\cdot\mid x)`$ towards $`\pi^*_\beta(\cdot\mid x)`$, i.e.,

matching a target distribution $`P^*(y\mid x)`$. In practice, the overall goal is to reduce the target risk under the

unknown gold distribution $`P^*(x,y)`$. Even if RL improves the

conditional distribution $`P(y\mid x)`$, a mismatch on the prompt

marginal can still lead to suboptimal optimization signal. Concretely,

standard RL typically samples prompts from a surrogate prompt

distribution (e.g., the stage-1 prompt marginal $`P_0(x)`$), while the

true target prompt marginal under $`P^*`$ may emphasize different

regions (especially hard STEM problems). Our failure-driven data construction defines a new prompt distribution As discussed previously, $`P_1(x)`$ better mimic the real distribution

$`P^*(x)`$, thus provides a better estimation to the target

distribution. As a result, RL updates are computed using samples that

are more representative of the hard regions that dominate the target

risk, yielding a better approximation to the ideal distribution-matching

objective. Under $`P_1(x)`$, the KL-regularized RL objective becomes Thus, analogous to [eq:reward_tilted_optimal_policy],

[eq:rl_under_p1] corresponds to

matching the joint distribution where $`P_1(x)`$ is the surrogate prompt distribution and

$`P^\prime(y\mid x)\propto P_0(y\mid x)\exp\big(\beta A(x,y)\big)`$ is

the surrogate Response distribution. Overall $`P^{*}_{\beta,1}(x,y)`$

provides better estimated risk over the gold distribution $`P^*(x,y)`$

when $`P_1(x)`$ is a better surrogate of the target prompt marginal and

$`P^\prime(y\mid x)`$ is a good Response distribution. . The proof

follows almost the same

as 9.2, thus we omit it here.

We use subscripts $`y_i`$ to denote the $`i`$-th training example

and superscripts $`y^t`$ to denote the $`t`$-th token within an

example. ↩︎ https://huggingface.co/Qwen/Qwen3-235B-A22B-Instruct-2507

↩︎ https://huggingface.co/Qwen/Qwen3-235B-A22B-Thinking-2507

↩︎ https://huggingface.co/datasets/nvidia/OpenScienceReasoning-2

↩︎ https://huggingface.co/datasets/di-zhang-fdu/AIME_1983_2024

↩︎The Failure-driven Second-stage Training

Evaluation for failure region identification.

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:binary-failure}

w_{\theta_1}(x)\in\{0,1\}, \quad

w_{\theta_1}(x)=1 \;\;\text{iff the verified final answer of $\pi_{\theta_1}$ on $x$ is incorrect}.

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

\label{eq:failure-biased-q}

Q_{\theta_1}(x)=\frac{Q(x)\,w_{\theta_1}(x)}{\mathbb{E}_{x\sim Q}[w_{\theta_1}(x)]},

\end{equation}Retrieval kernel induced by embeddings.

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:kernel-full}

K_{\tau}(d\mid x)=\frac{\exp\!\big(s(x,d)/\tau\big)}{\sum_{d'\in \mathcal{K}}\exp\!\big(s(x,d')/\tau\big)},

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

\label{eq:kernel-topk}

K_{\tau,k}(d\mid x)\propto \exp\!\big(s(x,d)/\tau\big)\cdot \mathbf{1}\!\left[d\in \mathrm{Top-}k(x)\right].

\end{equation}Data synthesis and the induced synthetic training distribution.

Second Stage Post-training.

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:psyn}

P_{\mathrm{syn}}(x^\prime, y^\prime)

=

\mathbb{E}_{x\sim Q_{\theta_1}}\;

\mathbb{E}_{d\sim K_{\tau,k}(\cdot\mid x)}\!\left[

G_{\mathrm{acc}}(x^\prime, y^\prime\mid d)

\right],

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

\label{eq:psyn-sum}

P_{\mathrm{syn}}(x^\prime, y^\prime)

=

\sum_x Q_{\theta_1}(x)\sum_d K_{\tau,k}(d\mid x)\,G_{\mathrm{acc}}(x^\prime, y^\prime\mid d).

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

{\mathcal{L}}_1(\theta) \triangleq \mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim P_1}\big[\ell_\theta(x,y)\big],\quad P_1 = \lambda P_0 + (1-\lambda) P_{\mathrm{syn}}.

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

\langle \nabla {\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta), \nabla{\mathcal{L}}_1(\theta)\rangle

\ge

\langle \nabla {\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta), \nabla {\mathcal{L}}_0(\theta)\rangle,

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

{\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta-\eta \nabla {\mathcal{L}}_1(\theta)) \le {\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta-\eta \nabla {\mathcal{L}}_0(\theta)).

\end{equation}

```*

</div>

</div>

We left the proof and detailed derivation

in <a href="#app:grad_alignment" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="app:grad_alignment">9.2</a>.

### Extension to Reinforcement learning

Our framework is derived under the purpose of dealing the mismatch

between training and target distribution, thus it can be naturally

extended to design a second stage training under reinforcement learning

via verified reward (RLVR). We do not elaborate the theoretical proof in

the main text, as it follows a similar structure as failure-driven SFT,

but only show the algorithm here. The detailed derivation can be found

in <a href="#apdx: ext_RL" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="apdx: ext_RL">9.3</a>

#### Stage-2 RLVR.

We first sample the prompts from the marginal distribution $`P_1(x)`$.

Then, for a prompt $`x`$, the model samples an output

$`y\sim \pi_\theta(\cdot\mid x)`$ and receives a verified reward as the

advantage function $`A`$, where

``` math

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:rl-binary}

A(x,y)\in\{0,1\},

\quad

A(x,y)=1 \;\;\text{iff the final answer in $y$ is verified correct}.

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

\label{eq:stage2-rl}

{\mathcal{L}}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{x\sim P_{1}(x)}\;

\mathbb{E}_{y\sim \pi_\theta(\cdot\mid x)}\big[A(x,y)\big].

\end{equation}Engineering Implementation

Knowledge Base Construction

Knowledge Retrieval

Data Synthesis

Reinforcement Learning Implementation

\begin{equation}

r_{i, t}(\theta)=\frac{\pi_\theta\left(y_i^t \mid x, y_i^{<t}\right)}{\pi_{\theta_{\text {old }}}\left(y_{i}^t \mid x, y_{i}^{<t}\right)}, \quad \hat{A}_{i}=\frac{A_i-\operatorname{mean}\left(\left\{A_i\right\}_{i=1}^G\right)}{\operatorname{std}\left(\left\{A_i\right\}_{i=1}^G\right)} .

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

\label{eq: DAPO}

R(x,y) =\left[\frac{1}{\Sigma_{i=1}^{G}|y_i|}\sum_{i=1}^{G}\sum_{t=1}^{|y_i|}\min(r_{i, t}(\theta)\hat{A}_{i}, \text{clip}(1+\varepsilon, 1-\varepsilon, r_{i, t}(\theta))\hat{A}_{i})\right]

\end{equation}Answer Correctness.

math-verify to compare model outputs against

ground-truth answers and assign a binary reward as advantage

$`A_i\in\{0,1\}`$. For multiple-choice questions, we extract the option

in $`\texttt{\textbackslash boxed}\{...\}`$ and match it to the ground

truth. Following , we apply dynamic sampling to filter problematic

training instances by (i) dropping over-length responses and (ii)

excluding prompts whose response-group mean scores fall outside a preset

range. Hyperparameters are summarized in

Table 12.Length and Repetition Aware Reward.

s(T,A)=

\begin{cases}

1, & A=1 \ \text{or}\ T\ge T_{\max},\\

0, & A=0 \ \text{and}\ T\le T_{\min},\\

\dfrac{T-T_{\min}}{T_{\max}-T_{\min}}, & \text{otherwise}.

\end{cases}Experiments

General Evaluation

Benchmarks

Evaluation Setting

General Evaluation Results

Model

Benchmark

2-7

AIME2024

AIME2025

BeyondAIME

HMMT2025

BRUMO2025

MATH500

avg@16

avg@16

avg@16

avg@16

avg@16

avg@4

Qwen3-8B

76.0†

67.3†

42.88

44.17

67.92

97.4†

w/ 64K Context ♣

75.62

69.17

43.88

42.29

68.12

96.3

OpenThinker3-7B

69.0†

53.3†

34.69

42.7†

61.88

90.0†

AceReason-1.1-7B

72.6†

64.8†

44.69

41.88

69.79

96.35

R1-0528-Qwen3-8B

77.18

68.75

42.50

49.17

70.62

94.35

w/ 64K Context ♣

86.0†

76.3†

48.69

61.5†

74.17

95.15

Klear-Reasoner-8B-SFT

75.6†

70.1†

32.06

57.6†

68.96

94.8

w/ 64K Context ♣

82.29

81.88

52.31

67.08

81.46

95.25

Klear-Reasoner-8B

83.2†

75.6†

48.81

60.3†

72.71

95.7

w/ 64K Context ♣

90.5†

83.2†

50.25

70.8†

77.08

95.3

Logics-STEM-8B-SFT

80.62

73.33

44.31

57.71

72.92

97.5

w/ 64K Context ♣

90.42

85.62

61.25

71.46

86.67

98.85

Logics-STEM-8B-RL

80.62

74.79

48.31

57.29

75.83

97.8

w/ 64K Context ♣

90.42

87.08

62.5

74.79

86.46

98.4

Model

Benchmark

2-5

GPQA-Diamond

R-Bench

MMLU-Pro-STEM

CMMLU-STEM

avg@16

avg@1

avg@1

avg@1

Qwen3-8B

62.00†

64.03

83.02

85.69

w/ 64K Context ♣

60.23

63.35

82.99

85.92

OpenThinker3-7B

53.70†

54.71

70.15

72.96

AceReason-1.1-7B

50.09

57.08

72.52

72.21

R1-0528-Qwen3-8B

58.30

62.48

79.41

85.02

w/ 64K Context ♣

61.10†

63.21

80.57

85.02

Klear-Reasoner-8B-SFT

62.12

57.04

79.90

81.80

w/ 64K Context ♣

63.64

64.03

81.62

82.62

Klear-Reasoner-8B

44.76

46.36

59.80

63.90

w/ 64K Context ♣

43.62

49.31

60.16

64.12

Logics-STEM-8B-SFT

72.70

72.21

85.20

85.06

w/ 64K Context ♣

73.11

72.12

85.24

86.82

Logics-STEM-8B-RL

74.31

71.57

85.33

87.87

w/ 64K Context ♣

73.93

73.67

85.63

88.31

Model

Benchmark

2-9

AIME2025

HMMT2025

BeyondAIME

GPQA-Diamond

Maj@16

Best@16

Maj@16

Best@16

Maj@16

Best@16

Maj@16

Best@16

Qwen3-8B

76.67

83.33

53.33

66.67

46.00

65.00

64.14

83.33

w/ 64K Context ♣

83.33

83.33

56.67

66.67

50.00

66.00

62.12

84.85

R1-0528-Qwen3-8B

73.33

86.67

53.33

76.67

48.00

68.00

64.65

89.39

w/ 64K Context ♣

76.67

86.67

63.33

73.33

58.00

72.00

65.66

90.91

Klear-Reasoner-8B-SFT

73.33

83.33

63.33

80.00

34.00

59.00

66.67

90.91

w/ 64K Context ♣

86.67

96.67

76.67

86.67

61.00

78.00

68.69

91.41

Klear-Reasoner-8B

80.00

93.33

73.33

86.67

57.00

75.00

46.46

77.78

w/ 64K Context ♣

83.33

96.67

73.33

83.33

59.00

74.00

46.46

79.80

Logics-STEM-8B-SFT

80.00

90.00

60.00

76.67

46.00

68.00

76.26

91.41

w/ 64K Context ♣

90.00

93.33

76.67

93.33

66.00

80.00

75.25

91.41

Logics-STEM-8B-RL

80.00

90.00

63.33

73.33

50.00

67.00

76.26

91.92

w/ 64K Context ♣

93.33

96.67

83.33

93.33

67.00

82.00

77.27

92.42

Ablation Study of Data

Sampling Strategy

Stratified Sampling.

Difficulty-Based Sampling.

Model

Benchmark

2-6

AIME2025

HMMT2025

MATH500

GPQA-D

MMLU-Pro-STEM

avg@16

avg@16

avg@4

avg@16

avg@1

Purely Length-Based Sampling

55.62

36.88

$\underline{95.35}$

46.88

75.81

Stratified Sampling

w/ Length-Based

$\underline{53.12}$

34.38

95.5

49.91

79.15

w/ Annotation-Based

52.29

$\underline{34.58}$

94.2

$\underline{48.42}$

$\underline{77.82}$

Source of failure-driven Synthetic Data

Algorithm

Benchmark

2-7

AIME2024

AIME2025

HMMT2025

GPQA-D

MMLU-Pro-STEM

CMMLU-STEM

Avg@16

Avg@16

Avg@16

Avg@16

Avg@1

Avg@1

baseline

90.21

85.56

68.96

73.20

85.35

86.82

GRPO

sci-syn-data

90.42

87.08

74.79

73.93

85.63

88.31

math-syn-data

89.79

86.04

70.42

72.70

85.10

87.27

Ablation Study of Algorithms

RLVR Algorithm

Algorithm

Benchmark

2-7

AIME2024

AIME2025

HMMT2025

GPQA-D

MMLU-Pro-STEM

CMMLU-STEM

Avg@16

Avg@16

Avg@16

Avg@16

Avg@1

Avg@1

DAPO

90.83

85.62

72.92

73.96

85.23

87.34

GRPO

91.46

83.54

69.58

73.55

85.29

87.34

Dynamic Sampling

Length-based Reward and Repetition Penalty

Algorithm

Benchmark

2-7

AIME2024

AIME2025

HMMT2025

GPQA-D

MMLU-Pro-STEM

CMMLU-STEM

Avg@16

Avg@16

Avg@16

Avg@16

Avg@1

Avg@1

GRPO

w/ len reward

90.42

87.08

74.79

73.93

85.63

88.31

w/o len reward

90.21

85.00

70.83

73.74

84.87

85.84

The Generalizability of Data Engine

Generalizability of Logics-STEM-SFT-Dataset to Larger-scaled Models

Model

Benchmark

2-7

AIME2024

AIME2025

BeyondAIME

HMMT2025

MATH500

GPQA-D

avg@16

avg@16

avg@16

avg@16

avg@4

avg@16

Qwen3-8B-Base-SFT

81.04

72.92

43.62

57.5

96.85

72.79

w/ 64K Context

88.75

83.33

61.38

68.96

98.45

73.17

Logics-STEM-8B-SFT

80.62

73.33

44.31

57.71

97.5

72.70

w/ 64K Context ♣

90.42

85.62

61.25

71.46

98.85

73.11

Qwen3-32B♣

82.08

73.12

50.00

55.00

96.55

68.18

Logics-STEM-32B-SFT♣

92.71

89.38

63.56

77.92

98.30

76.64

Generalizability of Failure-Driven Data

Model

Benchmark

2-7

AIME2024

AIME2025

BeyondAIME

HMMT2025

MATH500

GPQA-D

avg@16

avg@16

avg@16

avg@16

avg@4

avg@16

Logics-STEM-8B-SFT ♣

90.42

85.62

61.25

71.46

98.85

73.11

Logics-STEM-8B-RL ♣

90.42

87.08

62.50

74.79

98.40

73.93

Logics-STEM-8B-Exp1 ♣

88.75

83.12

59.69

71.04

97.00

70.96

Logics-STEM-8B-Exp2 ♣

90.83

84.79

62.06

72.08

97.35

72.19

Logics-STEM-8B-Exp3 ♣

91.88

85.62

62.69

73.33

97.40

73.33

Scale Inference Budget

Unsuccessful Attempts

Numeric-Answer-Only RLVR

Entropy Loss in RLVR

Scale Failure-Driven Synthetic Data

Conclusion

More about Data

Source of Data

Annotation

Generation Configuration

Parameter

Value

Temperature

0.6

Top-K

20

Top-P

0.95

Max Context Length

32768

STEM Benchmarks

MMLU-Pro-STEM is composed of the following categories extracted from

MMLU-Pro: “math,” “health,” “physics,” “biology,” “chemistry,” “computer

science,” and “engineering.”

CMMLU-STEM is composed of the following subsets from MMLU-Pro:

“high_school_mathematics”, “elementary_mathematics”,

“college_mathematics”, “high_school_physics”, “high_school_chemistry”,

“high_school_biology”, “electrical_engineering”, “conceptual_physics”,

and “college_actuarial_science”.More about Evaluation

Setting

Zero-shot Evaluation

boxed{} in response to each

question.

For benchmarks featuring multiple-choice questions, such as

GPQA-Diamond, MMLU-Pro-STEM, CMMLU-STEM, we prompt the model with the

following template:

A. $`10^-4`$ eV

B. $`10^-11`$ eV

C. $`10^-8`$ eV

D. $`10^-9`$ eV

Please put your final option letter within $$`\backslash`$boxed{}$.

Please put your final answer within $$`\backslash`$boxed{}$.Answer Verification

\boxed{} expression of the model’s

response and evaluate its correctness by comparing it with the

ground-truth answer using the math-verify library.Evaluation Metrics

Training Setting

Hyperparamaters

Parameter

Value

Batch Size

128

Learning Rate

4e-5

Learning Rate Scheduler

Cosine

Warmup Steps

1000

Epoch

3

Parameter

Value

Rollout Batch Size

64

Learning Rate

1e-6

Number of Return Sequences in Group

8

Response Length

32768

Low Threshold for Difficulty Mask

0.1

High Threshold for Difficulty Mask

0.95

Parameter

Value

Batch Size

64

Learning Rate

1e-5

Learning Rate Scheduler

Cosine

Epoch

3

Supplementaries for Ablation Studies in RLVR

Adaptive Entropy Control

Scale Failure-Driven Synthetic Data

Model

Benchmark

2-7

AIME2024

AIME2025

BeyondAIME

HMMT2025

MATH500

GPQA-D

avg@16

avg@16

avg@16

avg@16

avg@4

avg@16

Logics-STEM-8B-SFT ♣

90.42

85.62

61.25

71.46

98.85

73.11

Logics-STEM-8B ♣

90.42

87.08

62.50

74.79

98.40

73.93

Logics-STEM-8B-Exp3 ♣

91.88

85.62

62.69

73.33

97.40

73.33

Logics-STEM-8B-Exp4 ♣

89.58

85.62

64.38

71.67

97.75

74.84

Theoretical Results for Failure-Driven Post-training

The Resources of Failure Modes

Minizing the loss on $`P_0`$ may not minimize the target risk on $`P^*`$.

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:erm_p0}

\hat{\theta}_0=\arg\min_{\theta}\ \mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim P_0}\big[\ell_\theta (x,y)\big].

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

\label{eq:erm_pstar}

\theta^*=\arg\min_{\theta}\ \mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim P^*}\big[\ell_\theta(x,y)\big].

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

\label{eq:iw}

\mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim P^*}\big[\ell_\theta(x,y)\big]

=

\mathbb{E}_{(x,y)\sim P_0}\!\left[\frac{P^*(x,y)}{P_0(x,y)}\,\ell_\theta(x,y)\right],

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

\label{eq:support_mismatch}

P^*(\mathcal{A})>0,\qquad P_0(\mathcal{A})=0,

\end{equation}How failure-driven retrieval-synthesis mitigates distribution mismatch.

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:retrieval_kernel_discuss}

K(d\mid x)\propto \exp\!\big(\langle \varphi(x),\varphi(d)\rangle/\tau\big),

\end{equation}Failure-driven Post-training Provides Better Gradient Estimation

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:grad_sim}

\langle \nabla {\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta), \nabla{\mathcal{L}}_1(\theta)\rangle

\ge

\langle \nabla {\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta), \nabla {\mathcal{L}}_0(\theta)\rangle,

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

{\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta-\eta \nabla {\mathcal{L}}_1(\theta)) \le {\mathcal{L}}^*(\theta-\eta \nabla {\mathcal{L}}_0(\theta)).

\end{equation}

```*

</div>

</div>