Beyond Demand Estimation Consumer Surplus Evaluation via Cumulative Propensity Weights

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Beyond Demand Estimation Consumer Surplus Evaluation via Cumulative Propensity Weights- ArXiv ID: 2601.01029

- Date: 2026-01-03

- Authors: Zeyu Bian, Max Biggs, Ruijiang Gao, Zhengling Qi

📝 Abstract

This paper develops a practical framework for using observational data to audit the consumer surplus effects of AI-driven decisions, specifically in targeted pricing and algorithmic lending. Traditional approaches first estimate demand functions and then integrate to compute consumer surplus, but these methods can be challenging to implement in practice due to model misspecification in parametric demand forms and the large data requirements and slow convergence of flexible nonparametric or machine learning approaches. Instead, we exploit the randomness inherent in modern algorithmic pricing, arising from the need to balance exploration and exploitation, and introduce an estimator that avoids explicit estimation and numerical integration of the demand function. Each observed purchase outcome at a randomized price is an unbiased estimate of demand and by carefully reweighting purchase outcomes using novel cumulative propensity weights (CPW), we are able to reconstruct the integral. Building on this idea, we introduce a doubly robust variant named the augmented cumulative propensity weighting (ACPW) estimator that only requires one of either the demand model or the historical pricing policy distribution to be correctly specified. Furthermore, this approach facilitates the use of flexible machine learning methods for estimating consumer surplus, since it achieves fast convergence rates by incorporating an estimate of demand, even when the machine learning estimate has slower convergence rates. Neither of these estimators is a standard application of off-policy evaluation techniques as the target estimand, consumer surplus, is unobserved. To address fairness, we extend this framework to an inequality-aware surplus measure, allowing regulators and firms to quantify the profit-equity trade-off. Finally, we validate our methods through comprehensive numerical studies.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **New Consumer Surplus Estimation Method**: We propose a new method for estimating consumer surplus that does not require modeling demand. This allows us to directly estimate the surplus without needing an accurate demand model. 2. **Inequality-Aware Surplus Estimation**: Developed a methodology that evaluates the distribution of surplus across different customer groups, taking into account income inequality. 3. **Flexible Machine Learning Integration**: We incorporate modern machine learning techniques and complex nonparametric models to enhance the accuracy of our estimation process.Simple Explanation with Metaphors:

- Beginner Level: Estimating consumer surplus is like determining the price of an item in a market by identifying hidden variables between prices and purchase decisions. Our method directly estimates these hidden variables, providing accurate insights into consumer surplus.

- Intermediate Level: Traditional demand modeling involves piecing together various factors to connect prices with purchasing behavior, much like solving a puzzle. However, our approach bypasses this step by directly estimating consumer surplus.

- Advanced Level: Previous demand models relied on complex assumptions for precise estimation of demand functions; however, our method achieves accurate surplus estimates without these assumptions. This enables us to effectively evaluate the distribution and inequality of consumer surplus.

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

With the proliferation of data on consumer behavior and the development of sophisticated Artificial Intelligence (AI), firms are increasingly adopting autonomous, targeted algorithmic strategies to price goods and offer personalized loans. For example, many e-commerce firms will dynamically adjust prices based on an individual’s purchasing history, demographics, or even browsing behavior (e.g., ), while financial firms employ similar targeted algorithms to set interest rates for auto loans, mortgages, and credit cards. Indeed, the setting of interest rates is widely recognized as a form of targeted pricing, with recent studies utilizing auto loan datasets to empirically demonstrate the efficacy of algorithmic pricing strategies . Although these prescriptive AI technologies promise to enhance market efficiency, boost firms’ revenues, and broaden inclusion through personalized service, there are also concerns regarding their potential adverse impact on consumers.

A primary concern is that increased firm revenues due to targeted algorithms come at the expense of consumer surplus, with recent models from the academic literature suggesting that this burden can be unfairly distributed . In addition, there is a growing concern that marginalized groups might be disproportionately affected by these pricing practices, facing steeper prices and lower surplus. For example, ride-hailing services have been found to charge higher fares in neighborhoods with larger non-white populations and higher poverty levels, indicating that these communities face larger price hikes due to algorithmic pricing strategies . These concerns have drawn significant attention from policymakers and the media . For example, a White House report highlighted the risks associated with algorithmic decision-making in pricing, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) recently initiated investigations into potential discriminatory pricing practices by mandating transparency from companies employing personalized pricing schemes , and lawmakers have called for scrutiny of major retailers’ pricing practices . Although there is significant interest, it is not yet clear what the impact of more targeted algorithmic pricing policies will be .

These developments underscore the need for robust auditing tools capable of evaluating the impact of algorithmic pricing on consumer surplus and its distribution across customers. For regulators like the FTC, such tools can help ensure firms are abiding by relevant laws and regulations, such as the Gender Tax Repeal Act of 1995 (commonly known as the “Pink Tax”), which prohibits gender-based pricing discrimination , or the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) that prohibits creditors from discriminating against demographic factors. They can also help policymakers understand the impacts of various types of algorithmic pricing and who is adversely affected, leading to better guidelines and rules. Such tools can also help firms assess regulatory or reputational risks of existing algorithms, and simulate outcomes to ensure future compliance. They also provide the opportunity to strike a better balance between short-term profit and long-term customer relationships by ensuring consumer surplus remains at sustainable levels for all customer types.

Despite this need, there are issues regarding the efficacy of existing consumer surplus estimation methods. Typically, estimation techniques rely on first estimating demand and then integrating demand to calculate surplus (e.g., ), so the accuracy of the surplus estimate is highly dependent on the accuracy of the demand estimate. This approach is inherently indirect and requires estimating demand as a potentially complex function of price, even when the surplus target can be a simple scalar. Classical demand models depend on parametric assumptions and can be biased when behavior deviates from the assumed form . More flexible nonparametric and machine learning methods, such as neural networks , relax functional assumptions but often require very large datasets and careful tuning to achieve reliable accuracy, and typically have slower convergence rates. Given these shortcomings, it is useful to explore more direct alternatives for consumer surplus estimation that are less dependent on accurate demand estimation, and to investigate how to incorporate machine learning estimates while still achieving fast convergence rates.

One key feature of many successful modern pricing algorithms that can be leveraged for new methods of surplus estimation is that they involve a degree of price experimentation. In practice, market conditions, competitor actions, and consumer preferences evolve over time, so pricing algorithms must continuously explore the demand curve rather than solely exploit current prices to maintain optimality . Recent empirical work has observed severe bias in the estimation of price sensitivity at a large supermarket chain when using relatively static historic pricing data compared to experimental data, while have demonstrated that prices set after a period of price experimentation drastically improved profitability at ZipRecruiter. These examples also indicate an increased willingness among firms to engage in experimentation, which has become more ubiquitous as e-commerce platforms enable continuous price updates. While primarily intended to support profit maximization, this inherent randomization also provides a rich source of quasi-experimental variation that can be leveraged to estimate the consumer surplus.

One natural approach to utilizing such data and potentially avoiding explicit demand estimation is to adapt inverse-propensity-score weighting (IPW) from causal inference . However, the availability of quasi-experimental data alone does not solve the fundamental difficulty of measuring consumer welfare. Unlike revenue, which is entirely determined by the price and the observed purchase decision, consumer surplus relies on the customer’s valuation, a variable that is inherently latent. In the observational data, we do not observe the surplus. Instead, we only observe a binary purchase decision, which serves as a coarse approximation indicating that the valuation exceeded the price. Because the true outcome of interest is never directly seen, standard causal inference techniques such as weighting observed outcomes cannot be directly applied.

Motivated by these challenges, we propose the new cumulative propensity weight (CPW) estimator, which directly estimates consumer surplus and bypasses the need for explicit demand modeling. This approach leverages the randomness already present in the observational data due to the need to balance exploration and exploitation in many modern algorithmic pricing strategies. Intuitively, each observed purchase outcome at a randomized price is an unbiased estimate of demand. By carefully reweighting that observation according to how often a target pricing policy would offer a price at or below the one observed for similar customers, relative to how frequently that price level appeared historically, we are able to reconstruct the consumer surplus, i.e., the integral or the area under the demand curve, when these weighted outcomes are aggregated. When the historical pricing policy is known or well documented, the approach is straightforward to implement and is entirely model-free. When it is unknown, the cumulative weights can be estimated from transaction data.

Building on the cumulative-weights idea, we introduce a doubly robust estimator with cross-fitting that delivers reliable surplus estimates even when either the demand model or the historical pricing distribution is misspecified. Specifically, when the historical pricing policy is known or can be estimated accurately, consistency holds even with a biased demand model. In contrast, when demand is asymptotically unbiased, consistency holds even with a misspecified historical pricing model. Furthermore, mirroring standard doubly robust estimators in causal inference, our estimator achieves efficiency under weak rate conditions without imposing the Donsker condition on either demand or cumulative-weight estimation. This flexibility enables the use of modern machine learning techniques and complex nonparametric models. We formally establish that our proposed estimators are asymptotically equivalent to the efficient influence function, and therefore achieve the lowest possible asymptotic variance. Finally, we prove the asymptotic normality of the proposed estimators, enabling the construction of valid confidence intervals, enabling policymakers to assess the reliability of these estimates.

To address fairness, we extend our objective from estimating the standard consumer surplus to estimating an inequality-aware surplus. This new target captures both the magnitude of surplus a policy creates and its distribution across different customer types via a single pre-specified parameter. At its baseline, this parameter replicates the standard arithmetic average of customers’ surplus, but as it decreases, it places progressively greater weight on outcomes for worse-off groups. This approach is based on generalized mean aggregates as studied by and . To achieve this objective, we derive the efficient influence function of this new target and adapt our cumulative weights approach to construct an efficient estimator. Due to the nonlinearity of the objective, this estimator does not inherit full double robustness. Instead, it is singly robust with respect to the demand model, in that consistency holds as long as the demand is correctly specified, even if the cumulative weights are misspecified. This alters the theoretical requirements for establishing the asymptotic properties compared to the previous case: while incorporating cumulative weights still has the benefit of relaxed rate conditions, i.e., allowing flexible machine learning models, demand estimation requires stricter control, specifically satisfying standard nonparametric rates. Nevertheless, we derive valid asymptotic properties for this new estimator and show it has the minimal asymptotic variance among all regular estimators, which enables auditors to report valid confidence intervals for both aggregate and equity-sensitive surplus.

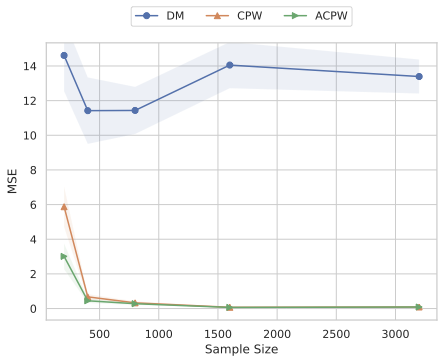

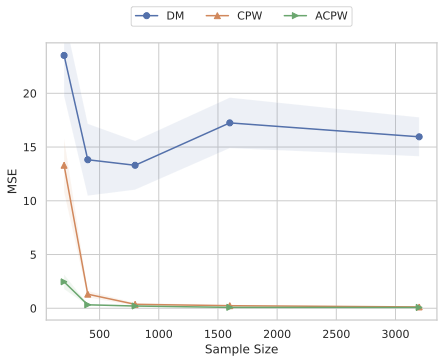

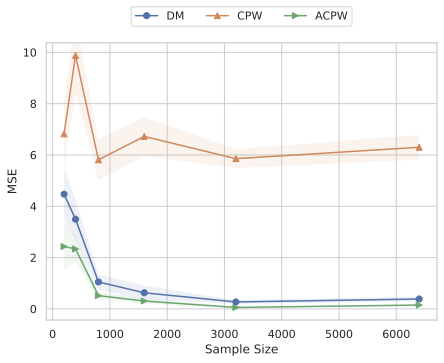

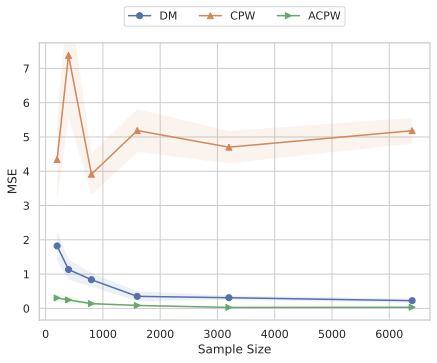

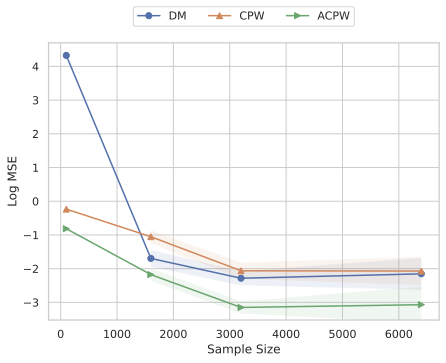

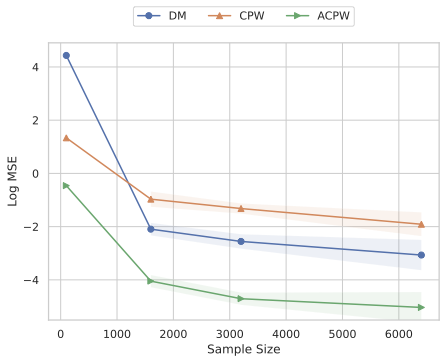

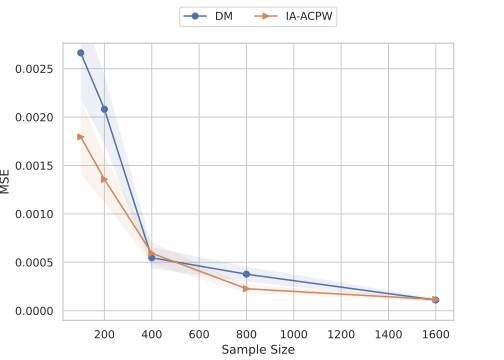

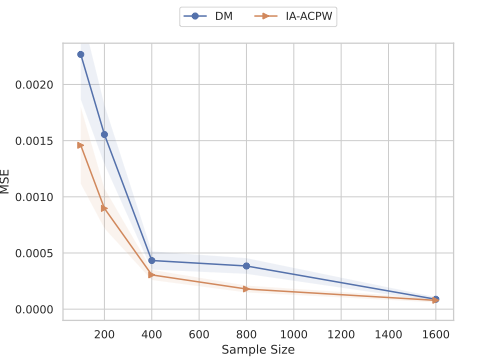

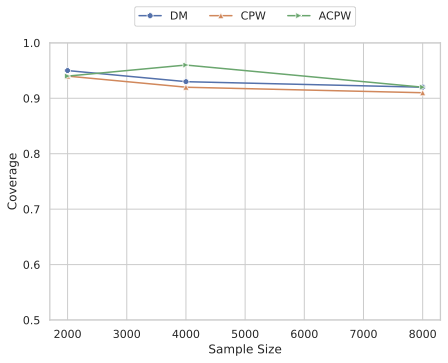

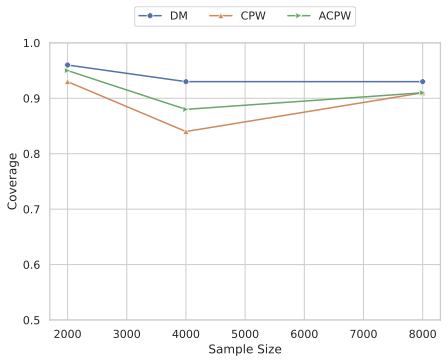

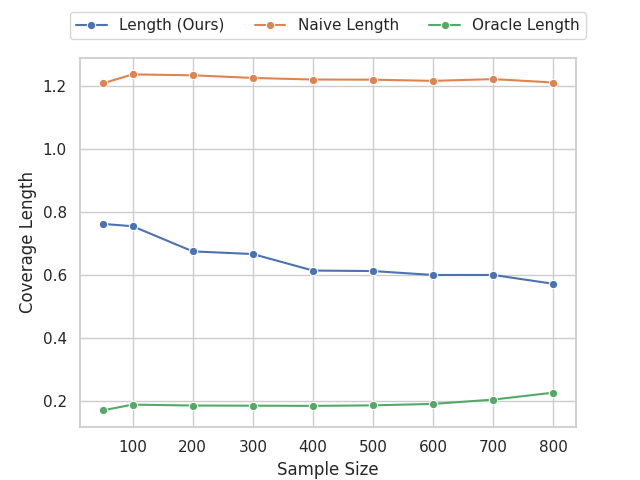

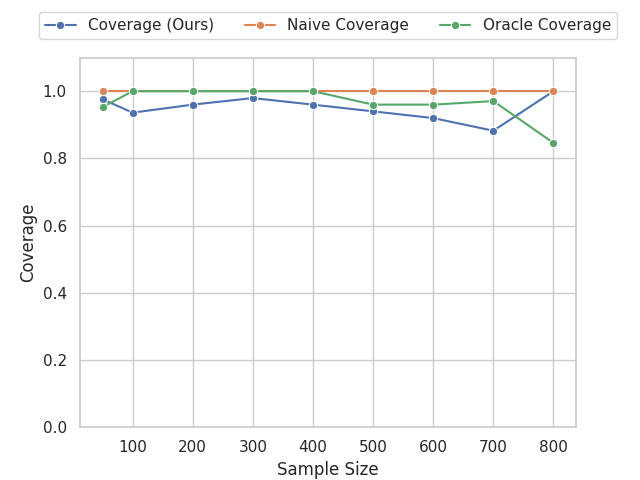

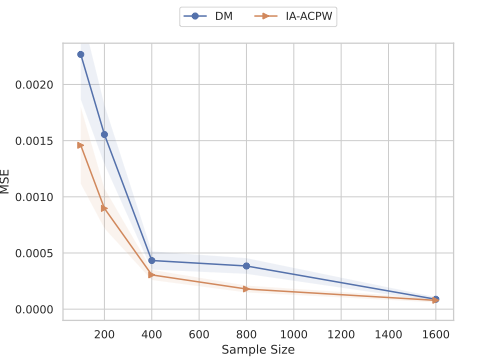

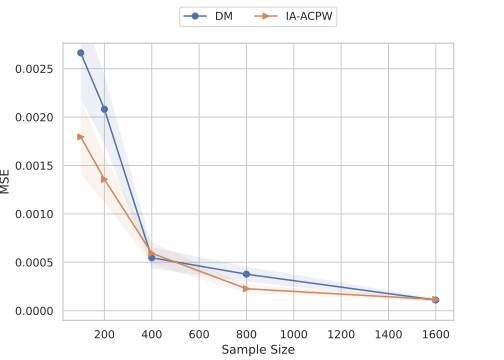

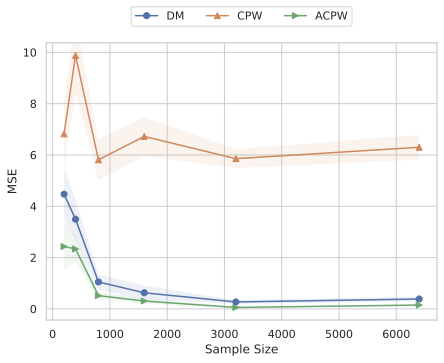

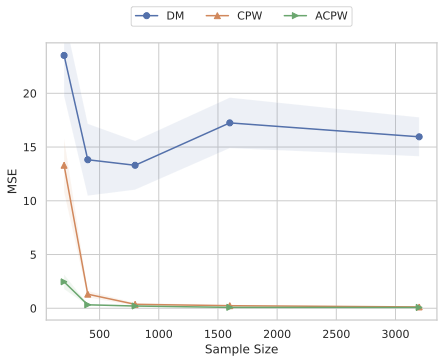

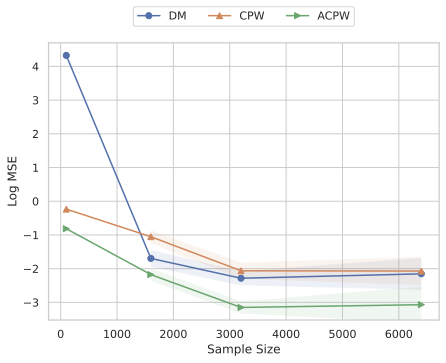

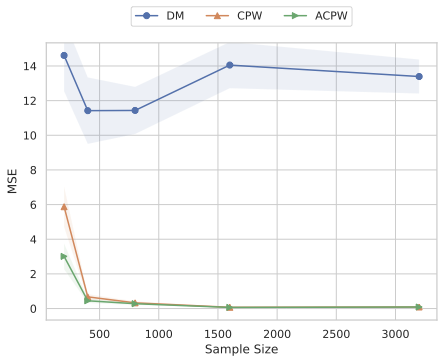

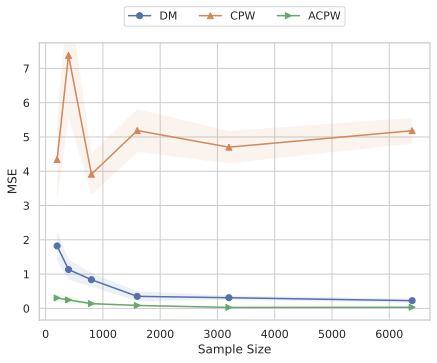

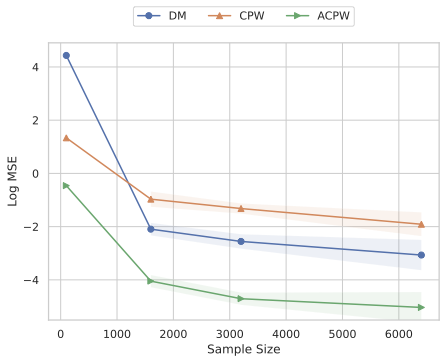

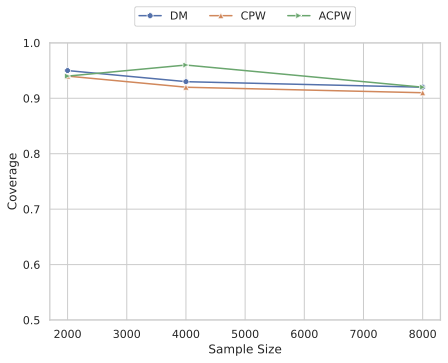

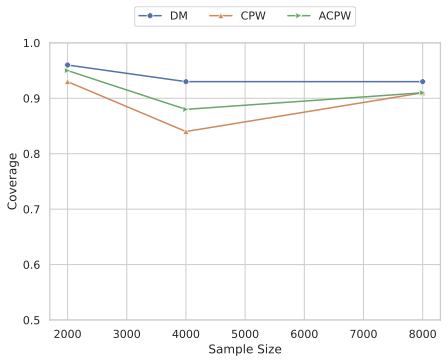

Our experiments confirm the reliability and robustness of the proposed framework. For the standard aggregate surplus, our doubly robust estimator accurately recovers the true surplus even when either the demand or pricing model is misspecified, achieving the best convergence rate when both are well specified. We further evaluate our inequality-aware surplus, studying its estimation error and confidence interval coverage. Despite the theoretical shift to single robustness for this nonlinear objective, our results demonstrate that the estimator remains highly effective, producing accurate point estimates and valid confidence intervals across varying equity settings.

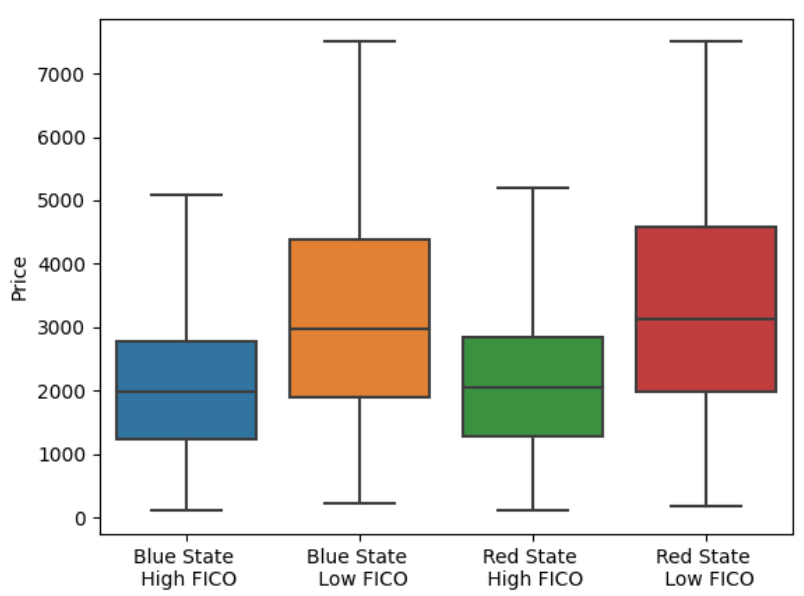

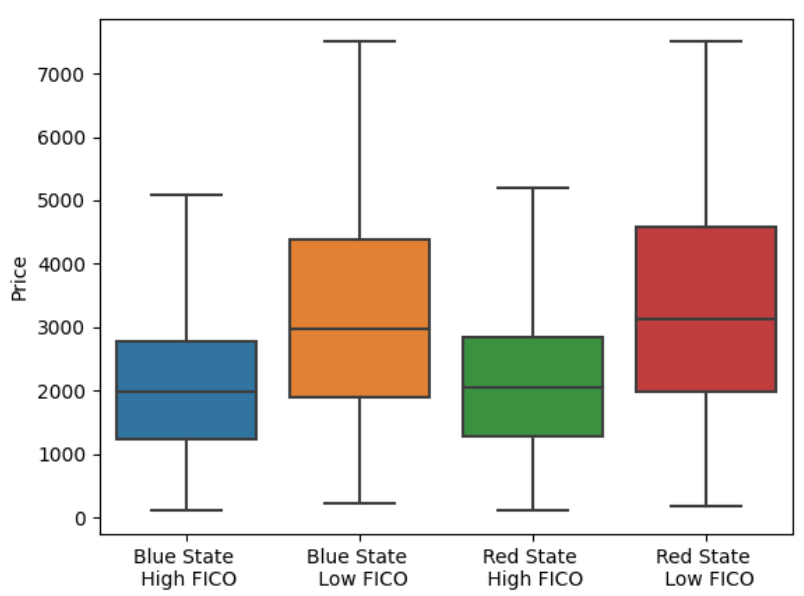

To further demonstrate the power of this framework, we apply it to a large-scale financial dataset of U.S. automobile loans. The global automotive market size was estimated at USD 2.75 trillion in 2025 and is projected to reach USD 3.26 trillion by 2030 . It is an important driver of household financial stability and is increasingly dominated by algorithmic underwriting. We compare the welfare outcomes of a historical pricing policy against a trained AI pricing agent. Our analysis reveals an aggregate consumer surplus–equity tradeoff: personalized pricing reduces total consumer surplus while narrowing disparities across credit and political groups, demonstrating the framework’s value for auditing and regulatory evaluation.

Related Work

Consumer Surplus Estimation

There is a substantial literature on consumer surplus evaluation in both discrete choice environments, where consumers typically choose one alternative from a set (e.g., ), and continuous demand settings (e.g., ), such as gasoline purchases . Our work is more closely aligned with discrete choice models, but we focus on a single-item setting in which we observe individual customer characteristics and a binary outcome indicating whether they purchase the item. Initially, parametric models of demand were used for surplus estimation , for example, the widely used logsum formula . This relies on strong assumptions about preferences and customer heterogeneity, such as additive extreme-value error distributions, which may lead to misleading welfare conclusions if the model is misspecified.

To overcome such restrictive assumptions and make inferences in a broader range of settings, many semiparametric and nonparametric methods for estimating demand have been developed . These typically involve flexible nonparametric regression to fit the demand function directly, followed by an integration to calculate the surplus. For example, in the continuous setting, fit demand using series and kernel estimators, and use it to solve a differential equation based on Shephard’s Lemma. Subsequent research has focused on incorporating unobserved consumer heterogeneity into these models . Similarly, in the discrete choice setting, estimates a conditional nonparametric probability of purchase for each item (demand in this setting), then integrates to estimate consumer surplus. Recent machine learning approaches have used neural networks to flexibly estimate demand and surplus with minimal functional-form assumptions , including in discrete choice models . Tree ensemble methods have also been proposed . A comprehensive account of nonparametric consumer surplus estimation can be found in and .

A critical trade-off in these nonparametric demand estimation methods is that convergence can be slower, leading to worse finite-sample performance than in well-specified parametric models. In either case, the consumer surplus estimates are only as accurate as the demand model. In contrast, we present approaches that do not require modeling demand at all, and show that we can achieve faster convergence when we have a slowly converging demand model.

Some recent applications of consumer surplus estimation can be found, for example, in , who use an ordered probit to analyze Netflix data. employ a Bayesian parametric framework to estimate surplus from a large-scale randomized price experiment at ZipRecruiter. Other research has leveraged quasi-experimental variation in prices. For instance, uses a regression discontinuity design to estimate price elasticities and surplus from Uber’s surge pricing data.

Much of this literature is focused on incorporating income effects, which is not the focus of our paper. We focus on settings where the expenditure represents a small fraction of the consumer’s total budget. In such regimes, the income effects are negligible, and the Marshallian consumer surplus provides a near-exact approximation of the Hicksian compensating variation . Alternatively one can interpret our analysis as applying when consumer utilities are quasilinear.

Causal Inference and Off-Policy Evaluation

Much of the recent work on auditing pricing algorithms can be viewed through the lens of off-policy evaluation (OPE). The OPE literature initially centered on the inverse propensity weighting (IPW) framework: each observed outcome is weighted by the reciprocal of its treatment (in our setting, price) assignment probability, or propensity score, yielding an unbiased estimate of the counterfactual reward when the propensity model is correct . A complementary line of research advocates the direct method (DM), which replaces missing counterfactuals with fitted values from an outcome model. When that model is correctly specified, the DM can be more efficient than IPW . Recognizing that either component may be misspecified in practice, the doubly‑robust estimator blends the two ideas and remains consistent so long as either the propensity model or the outcome model is estimated without systematic error. Empirical evidence suggests that, when at least one nuisance model is reasonably accurate, the doubly robust estimator achieves lower mean‑squared error than either IPW or the DM on their own . The idea of the doubly robust method originates from the missing data literature and has been widely adopted in causal inference and policy learning/evaluation .

In the management science community, there is a growing body of literature that leverages off-policy learning techniques to estimate revenue in pricing settings. This stream of research is often grounded in the “predictive to prescriptive” analytics framework , which formally integrates machine learning predictions with optimization models to derive decision policies from observational data. Complementing this methodological foundation, recent studies have developed rigorous statistical learning frameworks for personalized revenue management and demonstrated the practical efficacy of these data-driven pricing algorithms through large-scale field experiments . Specifically, researchers have used OPE techniques to address pricing settings characterized by binary demand , as well as censored demand resulting from inventory shortages , and unobserved confounding . In contrast to these works, our primary objective is the estimation of consumer surplus rather than revenue. This shift substantially alters the estimation problem: unlike the standard OPE setting, where the outcome is directly observed, surplus relies on consumer valuations that are never seen. In our context, we observe only a binary purchase decision, a coarse proxy indicating whether valuation exceeds price rather than the continuous valuation itself. Because the true outcome variable is latent, conventional causal inference techniques cannot be directly applied, necessitating the development of the novel methodological tools presented here.

Organization

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 3 formalizes the consumer surplus estimation problem. Section 4 introduces the Cumulative Propensity Weighting (CPW) estimator, a novel approach that leverages the randomness in algorithmic pricing to estimate surplus without explicit demand integration. Section 5 develops the Augmented CPW (ACPW) estimator, establishing its double robustness. Section 6 extends the framework to inequality-aware surplus measures, introducing a parameter to trade off aggregate surplus against equity. Section 7 provides the theoretical analysis, proving the asymptotic normality and efficiency of the proposed estimators. Section 8 presents numerical experiments validating the method’s robustness and demonstrates its application to a large-scale U.S. auto loan dataset. Finally, Section 9 concludes with managerial implications. The appendices contain proofs of all theorems and auxiliary lemmas. Lastly, we provide an extension on partial identification bounds for settings where the overlap assumption is violated in Appendix 19.

Problem Formulation

Consider a population of heterogeneous consumers with features $`X \in \mathcal X`$, and valuations (i.e., willingness to pay), $`V\in \mathbb{R}^+`$, interested in purchasing at most one unit of an item. For a fixed price $`p`$, the average consumer surplus can be defined as the average excess of each consumer’s valuation over the price they pay,

\begin{align*}

{\cal S}(p) = \mathbb{E}\left[\left(V - p\right)_+\right],

\end{align*}where $`x_+=\max(x,0)`$. Alternatively, in a lending scenario, we can consider $`p`$ as a periodic interest payment and interpret $`V`$ as the maximum interest the customer is willing to pay, with the surplus being the positive difference between them. Note, we may be interested in assessing the conditional surplus $`{\cal S}(p|X) = \mathbb{E}_V[\left(V - p\right)_+ \, | \,X]`$ associated with a particular group of interest for comparison purposes, or population surplus $`{\cal S}(p) = \mathbb{E}_X\mathbb{E}_V[\left(V - p\right)_+ \, | \,X]`$, which is the surplus over all customers. For notational simplicity, we focus on the latter, but our results also hold for the former, unless otherwise noted. We highlight that this definition is consistent with traditional “area under the demand curve" calculation of consumer surplus , where the demand curve is defined as the probability of purchase, as highlighted in Section 3.1. We do not incorporate income effects into the model and focus on goods where expenditure represents a small fraction of the consumer’s total budget. In this case, the income effects are negligible . Alternatively, but resulting in the same framework, we focus on customers with quasilinear utility.

In general, firms are interested in offering and evaluating pricing policies that can be both targeted and stochastic, where the price offered to the customer with feature $`X`$ is associated with a pricing policy $`\pi: {\cal X}\rightarrow \Delta({\cal P})`$, which is a conditional probability mass/density over the price space $`{\cal P}`$ given the feature $`X \in {\cal X}`$. Then the average consumer surplus under the pricing policy $`\pi`$ is defined as

\begin{align}

\label{def: consumer surplus for random p}

{\cal S}(\pi) = \mathbb{E}\left[\int_{\cal P}\pi(p \, | \,X)\left(V - p\right)_+ \text{d}p\right],

\end{align}where the underlying expectation is taken with respect to the joint distribution of $`(X, V)`$. If $`V`$ is observed, then one can estimate $`{\cal S}(\pi)`$ by directly using the sample average to approximate the expectation in Equation [def: consumer surplus for random p]. However, in practice, consumers’ valuations $`V`$ are typically unobserved, which presents a challenge for the estimation task. While a consumer’s valuation $`V`$ is often unobserved, typically their binary purchase decision $`Y`$ is often recorded at the price they were offered $`P \in {\cal P}`$. This purchase decision is determined by whether their valuation exceeds the offered price $`P`$:

\begin{align}

\label{model: true model}

Y &= \mathbb{I}(V > P).

\end{align}where $`\mathbb{I}(\cdot)`$ denotes the indicator function. Here, $`Y=1`$ denotes a purchase (the condition is met), and $`Y=0`$ denotes no purchase. In addition to $`V`$ being unobserved, we often face a distribution shift, where we may want to evaluate surplus under a pricing policy that is different from the historical policy that generated the data. In general, we consider three objectives: (i) evaluating consumer surplus of a new pricing strategy (also referred as the target policy) $`\pi`$; (ii) evaluating the consumer surplus of a current or previously used pricing strategy $`\pi_D`$ from the historical data (also referred as the behavioral policy); and (iii) evaluating the change in surplus between historical and new policies:

\begin{align}

\label{def: difference in consumer surplus}

\Delta(\pi) = \mathbb{E}\left[\int_{\cal P}\left(\pi(p \, | \,X)- \pi_D(p \, | \,X)\right)\left(V - p\right)_+ \text{d}p\right],

\end{align}We note that the historical pricing distribution $`\pi_D`$ may be known or unknown, while $`\pi`$ is always known. When the firm is engaged in algorithmic pricing, often the historical pricing policy is encoded digitally and is therefore known. When it is unknown, it can typically be estimated from the data. Generally, the difference between evaluating (i) and (ii) arises from unknown $`\pi_D`$, which can introduce additional challenges in the estimation. We will focus on this case when evaluating (ii) unless otherwise noted. The offline dataset can thus be represented as $`{(X_i, P_i, Y_i)}_{i=1}^n`$, consisting of i.i.d. samples of $`(X, P, Y)`$ generated under a historical pricing policy $`\pi_D`$.

Next, we present some conditions necessary for the identification of the average consumer surplus $`{\cal S}(\pi)`$ under the observational data-generating distribution. First, we provide the formal definition of identification.

Definition 1 (Identifiability). A parameter of interest $`\theta`$ in a probabilistic model $`\{\mathcal{P}_\theta: \theta \in \Theta \}`$ is said to be identifiable if the mapping $`\theta \mapsto \mathcal{P}_\theta`$ is injective, i.e., $`\mathcal{P}_{\theta_1} = \mathcal{P}_{\theta_2} \implies \theta_1 = \theta_2`$.

For identification in this setting, we require two conditions to hold:

Assumption 1. (Ignorability) $`P \protect\mathpalette{\protect\independenT}{\perp}V |X`$.

Assumption 2. (Overlap) The price data generating distribution satisfies $`\pi_D(p \, | \,x)>0`$, for all $`p \in {\cal P}`$, and every $`x\in {\cal X}`$. In addition, the support $`{\cal P}`$ contains the support of the valuation $`V`$. For identifying $`\Delta(\pi)`$, we only require the support of $`\pi_D`$ to contain the support of $`\pi`$.

Assumption 1 is similar to the classical causal assumptions of ignorability or exchangeability, see, e.g., . It states that, conditional on consumer characteristics $`X`$, the distribution of valuations is unaffected by the offered price, facilitating the identification of surplus. It is commonly satisfied as long as the factors that drove the historical pricing decisions are recorded and available in the observed data. It is worth noting that Assumption 1 does not impose any parametric structure on the consumer valuations model. Assumption 2 requires that every possible price $`p \in {\cal P}`$ has a positive probability of being observed for the observational data. This means the previous pricing policy must involve some degree of randomization, which, as previously discussed, is necessary for a pricing policy to obtain and maintain optimality. Such a condition is similar to the positivity condition in causal inference for identifying the average treatment effect. Without this coverage assumption, nonparametric identification of the demand function, and consequently, the absolute consumer surplus, is impossible without relying on strong extrapolation assumptions. However, we note that the requirements are significantly relaxed when evaluating the difference in surplus between two policies. In that context, we only require overlap over the prices proposed by the new policy $`\pi`$, rather than the entire price space. While identifying absolute surplus requires observing demand at extreme prices (to capture total willingness to pay), estimating policy differences is often sufficient for decision-making and aligns with standard practices in the literature . While we establish identification and estimation results for both quantities, we acknowledge the difference is easier to practically implement.

To address settings where Assumption 2 does not hold, Appendix 19 introduces an extension that exploits demand function properties (specifically monotonicity and log-concavity) to bound the surplus. Experimental results in Appendix 19.3 confirm the validity of these partial identification bounds and illustrate their superior tightness compared to naive bounds derived from the natural [0, 1] support of purchase probability.

Next, we present a commonly used baseline approach for estimating $`{\cal S}(\pi)`$ and discuss its limitations. Without loss of generality, we assume $`\mathcal P = [0, \infty)`$.

Baseline Solution: Direct Method

A classic approach to calculate the consumer surplus is to calculate the area under the demand curve above a particular price (for example, ). Under Assumption 1 we show this form is equivalent to our consumer surplus definition ([def: consumer surplus for random p]) for the stochastic pricing policy setting

\begin{align}

\label{eqn: identification}

&{\cal S}(\pi) = \mathbb{E}\left[\int_0^\infty\pi(p \, | \,X) \int_{z=p}^\infty \mu(X,z)dzdp \right],

\end{align}where $`\mu(x,z) \equiv \mathbb{E}[Y \, | \,X=x, P = z] \equiv\mathbb{P}[V > z \, | \,X=x]`$ is the probability of purchase, which can be considered the demand function in this setting. A brief proof showing the equivalence is provided in Proposition 3 in Appendix 10.1 and follows from carefully changing the order of integration. While Assumption 2 is not strictly required for the derivation of this identity, it is necessary for the identification and estimation of $`\mu(x,z)`$ over the integration range. This equation shows that even when the valuation $`V`$ is unobserved, the surplus can still be identified by first computing the integral of the demand function $`\mu(x,z)`$ over prices above $`p`$, and then taking a weighted average over price using the target policy $`\pi`$. When surplus under the behavior policy $`\pi_D`$, or the difference in surplus is of interest, it simplifies to

\begin{gather}

\label{eqn: identification behavioral}

{\cal S}(\pi_D) = \mathbb{E}_{X, P\sim \pi_D}\left[\int_{P}^{\infty}

\mu(X,z)dz\right], ~~ \Delta(\pi) = {\cal S}(\pi) - {\cal S}(\pi_D).

\end{gather}In practice, the demand function $`\mu(x, p)`$ is generally unknown and must be estimated by regressing $`Y`$ on $`X`$ and $`P`$, yielding an estimator $`\widehat \mu(x, p)`$. Then the direct method (DM) uses the sample average to approximate Equations [eqn: identification] and [eqn: identification behavioral] and gives

\begin{gather}

\label{eqn:dm_estimator}

\widehat {\cal S}_{DM}(\pi)= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \int_0^\infty\pi(p | X_i) \int_{p}^\infty \widehat \mu(X_i, z)dzdp, ~~ \widehat {\cal S}_{DM}(\pi_D)= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \int_{P_i}^\infty \widehat \mu(X_i, z)dz, \\

\widehat \Delta_{DM}(\pi) = \widehat {\cal S}_{DM}(\pi) - \widehat {\cal S}_{DM}(\pi_D),

\end{gather}where $`\widehat \mu(\cdot, \cdot)`$ is the estimator of the demand function. We note that the historic surplus estimator $`\widehat{\mathcal{S}}_{DM}(\pi_D)`$ has the advantage of not requiring an estimate of the historic pricing policy distribution $`\widehat{\pi}_D`$ (when it is unknown), compared to the naive approach of substituting $`\widehat{\pi}_D`$ into $`\widehat{\mathcal{S}}_{DM}(\pi)`$, highlighting the suitability of each estimator for its particular task.

As discussed previously, the performance of the DM estimator depends critically on the accuracy of the outcome model $`\widehat \mu(x, p)`$, which can be challenging to estimate in practice. Traditional demand estimators that impose fixed parametric forms can yield biased results whenever actual purchasing behavior strays from those assumptions. In contrast, modern fully non‑parametric techniques, such as neural‑network demand models , avoid functional‑form misspecification but generally require a very large sample before they deliver reliable accuracy, limiting their practicality in many observational settings. Furthermore, the DM relies on numerical integration of estimated functions. This step requires the underlying estimation to be uniformly accurate across $`\mathcal{P}`$. Lastly, the numerical integration procedure itself can introduce bias and raise computational burden since the integration must occur over all prices for every datapoint.

These limitations associated with the DM estimator motivate the exploration of alternative approaches. In the next section, we present our newly proposed solutions for identifying and estimating $`\mathcal{S}(\pi)`$.

Cumulative Propensity Weights Representation and Estimation

We next present an alternative approach for consumer surplus estimation that avoids the challenges of estimating a demand function and numerical integration. This estimator leverages the price variation already present in modern algorithmic pricing due to the need to balance exploration and exploitation. Rather than explicitly integrating to get the area under an estimated demand curve, the estimator approximates this area by an aggregate of weighted purchase outcomes, each of which is an unbiased estimate of demand at a given price. By carefully weighing the observations, we can recover the consumer surplus in expectation. Formally, our estimator is motivated by the following alternative identification result.

Theorem 1. *Under Assumptions 1 and 2, we have

\begin{align}

\label{eqn: identification CPW}

{\cal S}(\pi) =\mathbb{E}\left[\frac{F^\pi(P \, | \,X)}{\pi_D(P \, | \,X)}Y\right],

\end{align}where $`F^\pi(p|x)`$ denotes the cumulative distribution function under the target policy, i.e., $`F^\pi(p|x) \equiv \int_0^p \pi(u|x) du`$.*

Proof. The proof follows from the law of iterated expectations and a change of the order of integration:

\begin{align*}

& \underbrace{\mathbb{E}\!\left[ \int_{p=0}^\infty \pi(p\mid X) \int_{z=p}^\infty \mu(X,z) \, dz \, dp \right]}_{\mbox{Equation \eqref{eqn: identification}} }

= \mathbb{E}\!\left[ \int_{p=0}^\infty \int_{z=p}^\infty \pi(p\mid X)\,\mu(X,z) \, dz \, dp \right] \\

= & \; \mathbb{E}\!\left[ \int_{z=0}^\infty \int_{p=0}^z \pi(p\mid X)\,\mu(X,z) \, dp \, dz \right] = \mathbb{E}\!\left[ \int_{z=0}^\infty \Big(\int_{p=0}^z \pi(p\mid X)\,dp\Big)\,\mu(X,z) \, dz \right] \\

= & \;\mathbb{E}\!\left[ \int_{z=0}^\infty \frac{F^\pi(z\mid X)}{\pi_D(z\mid X)}\,\mu(X,z) \,\pi_D(z\mid X)\,dz \right] = \mathbb{E}\!\left[ \frac{F^\pi(P\mid X)}{\pi_D(P\mid X)}\,Y \right].

\end{align*}◻

Analogously, the historical consumer surplus and change in surplus can be identified by replacing $`\pi`$ with $`\pi_D`$ in Equation [eqn: identification CPW] and taking the difference:

\begin{equation}

{\cal S}(\pi_D) =\mathbb{E}\left[\frac{F^{\pi_D}(P \, | \,X)}{\pi_D(P \, | \,X)}Y\right], \mbox{ and } \Delta(\pi_D) =\mathbb{E}\left[\frac{\left(F^{\pi}(P \, | \,X)-F^{\pi_D}(P \, | \,X)\right)}{\pi_D(P \, | \,X)}Y\right].

\end{equation}Based on Theorem 1, our proposed CPW estimators can be derived by taking the sample average of Equation [eqn: identification CPW]:

\begin{align}

\label{eqn:ips_estimator}

\widehat {\cal S}_{CPW}(\pi)=& \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \frac{F^\pi(P_i | X_i)}{\widehat \pi_D(P_i | X_i)}Y_i,~~

\widehat {\cal S}_{CPW}(\pi_D)= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \frac{\widehat F^{\pi_D}(P_i | X_i)}{\widehat \pi_D(P_i | X_i)}Y_i,\\

&\widehat \Delta_{CPW}(\pi)= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \frac{(F^\pi(P_i | X_i)-\widehat F^{\pi_D}(P_i | X_i))}{\widehat \pi_D(P_i | X_i)}Y_i,

\end{align}where $`\widehat \pi_D`$ and $`\widehat F^{\pi_D}`$ are the estimators for the density and cumulative density for the historic policy, respectively.

We next present a simple example, illustrated in Figure 1, to give further intuition behind the CPW estimator.

Example 1.

Suppose that we are estimating the consumer surplus for a

target-pricing policy that assigns equal probability to three discrete

prices $`p_1

Now assume that the historical data were generated by a (known) historical pricing policy, uniformly distributed from 0 to 1. In the historical data, we happen to observe 13 random realized prices $`\{p_i'\}_{i=1}^{13}`$, which is a sparse representation of what would occur with more samples. Each realized pair $`(p_i', Y_i)`$ gives an unbiased snapshot of expected demand at that threshold, i.e., $`\mathbb{E}[Y\mid P=p_i']`$, where the black circles indicate the conditional expectations to which empirical averages converge with sufficient data for each price point. If we were to aggregate the outcomes $`Y_i`$ (or expected outcomes with enough data), we would approximate the total area under the demand curve. However, to approximate the consumer surplus for the target pricing policy by aggregation, we need different weights. In particular, to recreate the previous surplus calculation, we must weight observations at $`p'_{11}, p'_{12}, p'_{13}`$ by three times as much as at $`p'_5, p'_6, p'_7,p'_8`$, since the area under the curve in $`[p_3, 1)`$ is included in the surplus calculation for all three prices under the target policy (dark pink), whereas $`[p_1,p_2)`$ is only included once (light pink). $`[0,p_1)`$ is not included at all, while $`[p_2,p_3)`$ is included twice. This weight is the fraction of target policy prices whose surplus includes that historical price and is proportional to the cumulative target mass, which for the three-point target policy is $`F^{\pi}(p_i') \;=\; \frac{1}{3}\sum_{j=1}^{3}\mathbf 1\{p_i'\ge p_j\}`$ (i.e., $`F^{\pi}(p_1')=0, F^{\pi}(p_5')=1/3, F^{\pi}(p_9')=2/3, F^{\pi}(p_{11}')=1`$). This is shown in the lower panel of Figure 1. As a result, with more sampled price points along the range of prices, the weighted average $`\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \frac{F^{\pi}(p'_i )}{ \pi_D(p'_i )}Y_i`$ will eventually approximate the area under the demand curve, weighted by the frequency it is included in the target surplus calculation, i.e., $`\frac{1}{3}\sum_{i=1}^{3} \pi(p_i) \int_{z=p_i}^{\infty} \mathbb{E}[Y \, | \,P = z]dz`$, as the number of samples gets large. 1

This approach contrasts with standard IPW in off-policy evaluation in two significant ways. First, the observable $`Y`$ is not the unobserved surplus, $`(V-P)_+`$, we are trying to estimate under the new pricing policy. Second, the numerator of the weighting term is the cumulative target policy density $`F^\pi(P\mid X)`$, not the target density $`\pi(P|X)`$ at $`P`$ that typically appears in IPW. This is due to the need to estimate the average of an integral (or area) rather than the usual average outcome. As such, standard IPW techniques cannot be applied.

Compared to the direct method (Equation [eqn: identification]), this result requires knowledge, or an estimate, of the pricing distribution $`\pi_D`$ instead of the demand function $`\mu(X, P)`$. When the historic pricing policy is known, this estimator is unbiased and completely model-free. This may occur if a company is investigating the consumer surplus implications of its own algorithmic pricing policy, or a policymaker mandates that the algorithm be made available for audit. Alternatively, if the historical pricing policy is relatively simple, it may be much easier to estimate than a complex demand function. Furthermore, the DM requires numerical integration over the price space $`P`$ for every observation, which can be computationally expensive. In contrast, the CPW estimator is a simple weighted average, making it computationally efficient for large datasets. This alternative estimator provides the regulator or firm with crucial flexibility in surplus estimation.

Nevertheless, the performance of the CPW estimator remains sensitive to the accuracy of the estimated historical pricing policy distribution when it is not available and may be subject to misspecification. To further address this issue, we introduce the augmented CPW (ACPW) estimator, which combines elements of both the DM and CPW approaches, remaining consistent if either component is correctly specified, and is therefore more robust.

Doubly Robust Representation and Estimation

The construction of the ACPW estimator is grounded in the theory of the efficient influence function (EIF). The EIF is pivotal for two main reasons: it characterizes the semiparametric efficiency bound (the minimal asymptotic variance of any regular estimator), and it provides a constructive mechanism for achieving this bound. Intuitively, the EIF acts as a correction term that removes the first-order bias from a naive plug-in estimator (e.g., DM or CPW estimators in our context). This correction is essential for ensuring that the final estimator remains $`\sqrt{n}`$-consistent and asymptotically normal, even when the nuisance components (such as the demand function and cumulative weights) converge at slower rates. Formally, the EIF is defined as the canonical gradient of the target parameter, e.g., $`\mathcal{S}(\pi)`$, $`\mathcal S(\pi_D)`$ and $`\Delta(\pi)`$, with respect to the underlying data distribution. By constructing our estimator based on this gradient, we ensure it is asymptotically efficient (i.e., minimax optimal). For a comprehensive treatment of this theory, we refer readers to . We now present the derived EIF for $`{\cal S}(\pi)`$ under our semi-parametric model [model: true model]. Let $`\mathcal D = (X, P, Y)`$.

Theorem 2. *Suppose Assumptions 1 and 2 hold, the EIF for $`{\cal S}(\pi)`$ is

\begin{gather}

\label{eqn: eif}

\psi^\pi(\mathcal{D}) = \int_0^\infty \pi(p| X) \int_{p}^\infty \mu(X, z)dzdp + \frac{F^\pi(P | X)}{\pi_D(P | X)}(Y - \mu(X,P))-{\cal S}(\pi).

\end{gather}If the behavior policy $`\pi_D`$ is evaluated, then the EIF takes the form

\begin{gather}

\label{eqn: eif behav}

\psi^{\pi_D}(\mathcal {D})= \int_{P}^\infty \mu(X, z)dz + \frac{F^{\pi_D}(P | X)}{\pi_D(P | X)}(Y - \mu(X,P))-{\cal S}(\pi_D).

\end{gather}Finally, the EIF for the difference in surplus $`\Delta(\pi)`$ is given as $`\psi^{\Delta}(\cal{D}) = \psi^\pi(\cal {D}) -\psi^{\pi_D}(\cal {D})`$.*

This is formally proved in Appendix 11. A key property of the EIF is that it has mean zero. This motivates the following estimators, defined by setting the empirical mean of the EIFs in Equations [eqn: eif] and [eqn: eif behav] to zero:

\begin{align}

\label{eq:empirical dr}

\widetilde {\cal S}_{ACPW}(\pi) &= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \bigg[\int_0^\infty\pi(p | X_i) \int_{p}^\infty \widehat\mu(X_i, z)dzdp + \frac{F^\pi(P_i | X_i)}{\widehat \pi_D(P_i | X_i)}(Y_i - \widehat \mu(X_i,P_i))\bigg], \\

\label{empirical dr2}\widetilde {\cal S}_{ACPW}(\widehat \pi_D) &= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \bigg[\int_{P_i}^\infty \widehat\mu(X_i, z)dz + \frac{ \widehat F^{\pi_D}(P_i | X_i)}{\widehat\pi_D(P_i | X_i)}(Y_i - \widehat \mu(X_i,P_i))\bigg], \\

\widetilde \Delta_{ACPW}(\pi) &= \widetilde {\cal S}_{ACPW}(\pi)- \widetilde {\cal S}_{ACPW}(\widehat \pi_D).

\end{align}One can observe that the ACPW estimator integrates elements of both the DM and CPW approaches, and it can be shown that the ACPW estimator remains consistent if either the demand function or the behavior policy is correctly specified, a property known as double robustness. The double robustness property is formally stated in the following proposition for the case of the known target policy, but the other cases also hold with near identical proofs.

Proposition 1. *Let $`\bar{\mu}(x,p)`$ and $`\bar{\pi}_D(p|x)`$ denote the population limits of the estimators $`\widehat{\mu}(x,p)`$ and $`\widehat{\pi}_D(p|x)`$, respectively, such that:

\sup_{x,p} |\widehat{\mu}(x,p) - \bar{\mu}(x,p)| =o_p(1) \quad \text{and} \quad \sup_{x,p} |\widehat{\pi}_D(p|x) - \bar{\pi}_D(p|x)| =o_p(1).If either of the following conditions holds: (i) $`\bar\mu(X,P)=\mu(X,P)`$, almost surely; (ii) $`\bar \pi_D(P|X)= \pi_D(P|X)`$, almost surely. Then we have consistency such that:

\begin{gather*}

\left|\widetilde {\cal S}_{ACPW}(\pi)-{\cal S}(\pi)\right|=o_p(1),

\end{gather*}where $`o_p(1)`$ denotes a quantity that converges to zero in probability as the sample size $`n \to \infty`$.*

The proof of Proposition 1 can be found in Appendix 12. This property is important because it provides the regulator with flexibility in surplus estimation, depending on whether consistent demand estimation or historical pricing policy density estimation is possible to achieve. Besides the desirable doubly robust property, another advantage of the ACPW estimator is that, under minimal rate conditions on the two nuisance estimators (the demand function and the behavior policy density), it can achieve the lowest possible variance bound when combined with data splitting or a cross-fitting procedure . We next outline the $`K`$-fold cross-fitting procedure, a minor algorithmic modification of the vanilla ACPW estimators in Equations [eq:empirical dr] and [empirical dr2]. Specifically, we partition the sample indices $`\{1,\ldots,n\}`$ into $`K`$ disjoint folds of approximately equal size, with any finite number $`K`$. For each observation $`i`$, let $`k(i)`$ denote the fold containing $`i`$. Denote by $`\widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(x,p)`$ and $`\widehat \pi_D^{-k(i)}(p \mid x)`$ the estimators of the demand function and the behavior policy, respectively, which are trained using only the data excluding the $`k(i)`$-th fold (hence the notation $`-k(i)`$). The resulting ACPW estimator with cross-fitting is denoted as

\begin{gather*}

\widehat {\cal S}_{ACPW}(\pi)= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \left[\int_0^\infty\pi(p | X_i) \int_{p}^\infty \widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i,z) dzdp + \frac{F^\pi(P_i | X_i)}{\widehat\pi_D^{-k(i)} (P_i | X_i)}(Y_i - \widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i,P_i))\right],\\

\widehat {\cal S}_{ACPW}(\pi)= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \left[\int_0^\infty\pi(p | X_i) \int_{p}^\infty \widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i,z) dzdp + \frac{F^{\widehat \pi_D, -k(i)}(P_i | X_i)}{\widehat\pi_D^{-k(i)} (P_i | X_i)}(Y_i - \widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i,P_i))\right].

\end{gather*}This cross-fitting approach ensures that each observation is evaluated using nuisance estimates fitted on independent data, thereby reducing overfitting bias and enabling valid asymptotic inference even when the nuisance functions are estimated by flexible machine learning methods, as will be detailed in Section 7.

Inequality-Aware Surplus

A common concern among policymakers when evaluating a pricing policy is not only how the aggregate surplus changes, but also how it is distributed among consumers. In particular, there are concerns about equity and the impact on those who are worst off. One approach used in welfare economics to address these issues is to emphasize outcomes for customers with the lowest surplus when aggregating surpluses across the population. We follow this direction by extending the proposed off-policy consumer surplus estimation techniques to welfare measures that are sensitive to how surplus is distributed across customer types.

Let $`\mathcal{S}(\pi\mid X)`$ denote the surplus for customers with characteristics $`X`$, which represent customer types. Earlier sections implicitly aggregated welfare using the arithmetic mean, $`\mathcal{S}(\pi)=\mathbb{E}_{X}[\mathcal{S}(\pi\mid X)]`$, effectively averaging across all customer types. Following the Atkinson tradition and related work , we instead consider the generalized-mean family

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:atkinson-agg}

(\mathcal{S}^r(\pi))^{1/r},

\end{equation}where $`\mathcal{S}^r(\pi):=\mathbb{E}_{X}\big[\mathcal{S}(\pi\mid X)^r\big]`$. This coincides with the standard arithmetic average when $`r=1`$ and increasingly prioritizes lower-surplus groups as $`r`$ decreases, becoming more inequality averse. This supplies a transparent policy parameter $`r`$ that trades off aggregate surplus against its dispersion across customer segments. The continuous extension at $`r=0`$ yields the geometric mean, and $`r=-1`$ yields the harmonic mean. In the following, for brevity, we focus on $`r\neq 0`$ to avoid restating results that are functionally the same. For a finite sample $`\{X_i\}_{i=1}^{n}`$, the standard DM estimator is:

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:atkinson-agg-sample}

\left(\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}\widehat{\mathcal{S}}(\pi\mid X_i)^{r}\right)^{1/r}=\left[\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n} \left(\int_0^\infty\pi(p | X_i) \int_{p}^\infty \widehat\mu(X_i, z)dzdp\right)^r\right]^{1/r},

\end{equation}Without loss of generality, we will focus on estimating $`\mathcal{S}^r(\pi)`$, which can be transformed after estimation to recover $`\mathcal{S}^r(\pi) ^{1/r}`$. Next, we derive the efficient influence function for the target $`\mathcal{S}^r(\pi)`$ and behavioral $`\mathcal{S}^r(\pi_D)`$ policies and their corresponding efficient estimators. The EIF is given by the following theorem.

Theorem 3. *Under Assumptions 1 and 2, for $`r\neq 0`$, the EIF for $`{\cal S}^r(\pi)`$ is

\begin{gather}

\nonumber r \frac{(Y-\mu(X,P))F^\pi(P|X)}{\pi_D(P|X)} \left(\int_0^\infty\pi(p | X) \int_{p}^\infty \mu(X, z)dzdp \right)^{r-1}\\

+\left( \int_0^\infty\pi(p | X) \int_{p}^\infty \mu(X, z)dzdp \right)^r-{\cal S}^r(\pi), \label{eqn: eif aware}

\end{gather}and the EIF for $`{\cal S}^r(\pi_D)`$ is

\begin{gather}

\nonumber r \left[\frac{(Y-\mu(X,P))F^{\pi_D}(P|X)}{\pi_D(P|X)} + \int^\infty_P \mu(X,z)dz \right]\left(\int_0^\infty\pi_D(p | X) \int_{p}^\infty \mu(X, z)dzdp \right)^{r-1}

\\

+ (1-r)\left( \int_0^\infty\pi_D(p | X) \int_{p}^\infty \mu(X, z)dzdp \right)^r-{\cal S}^r(\pi_D).

\end{gather}By linearity, the EIF of $`\Delta^r(\pi)`$ follows by taking the difference between the above two EIFs.*

Theorem 3 establishes the EIF for the inequality-aware surpluses, $`{\cal S}^r(\pi)`$, $`{\cal S}^r(\pi_D)`$ and their difference $`\Delta_r(\pi)`$ and is proved in Appendix 13. In more detail, Equation [eqn: eif aware] shares a structure analogous to the EIF for the standard surplus in Equation [eqn: eif]: the $`\int_0^\infty\pi(p | X) \int_{p}^\infty \mu(X, z)dzdp`$ term corresponds to the DM component, while $`\frac{(Y-\mu(X,P))F^\pi(P|X)}{\pi_D(P|X)}`$ is a mean-zero de-biasing term incorporating cumulative weights, which plays a crucial role in variance reduction, enabling the resulting estimator to attain the semiparametric efficiency bound. Naturally, Theorem 3 motivates the following estimators to estimate $`{\cal S}^r(\pi)`$ and $`{\cal S}^r(\pi_D)`$ respectively, obtained by setting the empirical mean of the EIF to zero together with cross-fitting:

\begin{align}

\label{eq:aware estimator}

\widehat {\cal S}^r(\pi)= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \Bigg[ &r \frac{(Y_i-\widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i,P_i))F^\pi(P_i|X_i)}{\widehat{\pi}^{-k(i)}_D(P_i|X_i)} \left(\int_0^\infty \pi(p | X_i) \int_{p}^\infty \widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i, z)dzdp\right)^{r-1} \nonumber \\

&+ \left(\int_0^\infty\pi(p | X_i) \int_{p}^\infty \widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i, z)dzdp \right)^r \Bigg],

\end{align}\begin{align*}

\nonumber \widehat {\cal S}^r(\pi_D) = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n &\Bigg[r \left(\frac{(Y_i-\widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i,P_i))\widehat F^{\pi_D,-k(i)}(P_i|X_i)}{\widehat\pi_D^{-k(i)}(P_i|X_i)} + \int^\infty_{P_i} \widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i,z)dz \right) \\

& \quad \times \left(\int_0^\infty \widehat \pi_D^{-k(i)}(p | X_i) \int_{p}^\infty \widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i, z)dzdp \right)^{r-1} \\

& + (1-r)\left( \int_0^\infty \widehat\pi_D^{-k(i)}(p | X_i) \int_{p}^\infty \widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i, z)dzdp \right)^r\Bigg]

\end{align*}Then $`\widehat \Delta^r(\pi)=\widehat {\cal S}^r(\pi) - \widehat {\cal S}^r(\pi_D)`$.

We refer to this class of estimators as the inequality-aware ACPW estimator (IA-ACPW). Although the estimator $`\widehat{\mathcal{S}}^r(\pi)`$ in Equation [eq:aware estimator] is derived from the EIF in [eqn: eif aware] and incorporates both DM and CPW elements, it does not possess the double robustness property typically associated with the ACPW estimator. This stems from the fact that the functional $`S^r(\pi)`$ is nonlinear when $`r \neq 1`$. For example, the functional reweights observations such that small surpluses gain more leverage for $`r < 1`$. Consequently, a single data point perturbs the estimator differently than it would under a simple arithmetic mean. Due to this nonlinearity, $`\widehat{\mathcal{S}}^r(\pi)`$ is consistent only if the demand model is correctly specified, although the historic pricing policy $`\widehat \pi_D`$ can be misspecified. The necessity of consistency for the demand estimation can clearly be seen in Equation [eq:aware estimator], where the first term disappears when $`\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \left(Y_i-\widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i,P_i)\right)`$ converges to 0, leaving the second term which is clearly only consistent when demand is consistent. However, as we will show in the asymptotic analysis in Section [sec:normality_aicpw], the cumulative weights play an important role in reducing variance, enabling the use of flexible machine learning policies with slower convergence rates.

The estimation of the inequality-aware surplus of the behavioral policy $`\mathcal{S}^r(\pi_D)`$ presents an even greater challenge. Unlike $`\widehat{\mathcal{S}}^r(\pi)`$, the estimator $`\widehat {\cal S}^r(\pi_D)`$ does not enjoy even single robustness; it requires the simultaneous consistency of both the demand model $`\widehat \mu`$ and the propensity model $`\widehat \pi_D`$. This added fragility arises because $`\pi_D`$ is not known but estimated, and it serves a dual role: it acts as the propensity weight in the debiasing term and explicitly defines the integration measure in the demand term. Consequently, if $`\widehat \pi_D`$ is misspecified, the estimator converges to a functional of the wrong policy, preventing consistency even if the demand model $`\widehat \mu`$ is perfect.

An example showing inconsistency of $`\widehat{\mathcal{S}}^r(\pi)`$ with a misspecified demand model is given next.

Example 2. *(Inequality-aware ACPW estimator is not robust to demand misspecification) Consider estimating the functional

{\cal S}^r(\pi) = \biggl(\int_0^\infty \pi(p) \int_{z=p}^\infty \mu(z)\,dz\,dp\biggr)^r

\quad\text{with}\quad r=\tfrac12,in a setting without covariates, where $`\mu(\cdot)\equiv \mathbb{E}[Y\mid P=\cdot]`$ denotes the demand function.*

*Assume $`P\sim\mathrm{Uniform}[0,1]`$, so the behavior policy satisfies $`\pi_D(p)=1`$ for all $`p\in[0,1]`$. Let the target policy also be $`\pi(p)=1`$, which implies $`F^\pi(z)=z`$, and suppose the true demand function is $`\mu(p)=1-p^2.`$ Under this setup, define

\theta^*=\int_0^1 \pi(p) \int_p^1 \mu(z)\,dz\,dp

= \int_0^1 1 \cdot \left[ z - \frac{z^3}{3} \right]_p^1 \,dp

= \int_0^1 \left(\frac{2}{3} - p + \frac{p^3}{3}\right)\,dp

= \frac14,so that $`\mathcal{S}^r(\pi)=(\theta^*)^{1/2}=\frac12.`$*

*Now, suppose the analyst uses a misspecified linear demand model whose limiting fit is $`\bar\mu(p)=1-\tfrac12 p .`$ The corresponding first-stage limit is

\bar\theta

=\int_0^1 \pi(p) \int_p^1 \bar\mu(z)\,dz\,dp

=\int_0^1 1 \cdot \left[ z - \frac{z^2}{4} \right]_p^1 \,dp

=\int_0^1 \left(\frac{3}{4} - p + \frac{p^2}{4}\right)\,dp

=\frac13.Hence, the population limit of the IA-ACPW estimator is

\bar\theta^{1/2}

\;+\;

\frac12\,\bar\theta^{-1/2}

\,

\underbrace{\mathbb{E}\!\left[

\frac{F^\pi(P)}{\pi_D(P)}\,

\bigl(Y-\bar\mu(P)\bigr)

\right]}_{\int_0^1 z(0.5 z-z^2)\,dz

=-1/12}=\sqrt{\frac13}

\;-\;

\frac{\sqrt{3}}{24},which differs from the true value $`1/2`$. Therefore, even when the behavior policy is correctly specified, misspecification of the demand model combined with the nonlinearity of the target functional yields a non-vanishing second-order remainder term and leads to bias.*

Theoretical Analysis

In this section, we establish the asymptotic normality of our proposed estimators and highlight the conditions required to achieve this. These results are particularly important, since they enable statistical inference and the construction of confidence intervals for surplus estimates. In practice, this allows firms to rigorously assess whether changes in their pricing strategy lead to statistically significant improvements in overall surplus or consumer welfare. For example, an e-commerce company may wish to evaluate whether a newly deployed dynamic pricing algorithm $`\pi`$ yields a higher expected consumer surplus than the existing pricing strategy $`\pi_D`$. By constructing confidence intervals for the respective estimators, the firm can formally test whether the observed improvement is statistically meaningful, rather than the result of random variation in sales data.

We also show that these estimators attain the semiparametric efficiency bounds. This means that, among all regular and asymptotically linear estimators, our proposed estimators achieve the lowest possible asymptotic variance. Although all estimators for the same target achieve this bound, the assumptions required to achieve it can differ, and in particular we show that the conditions for ACPW are relatively mild, allowing fast rates of convergence even if the demand function or historical price density estimates converge at slower rates. Throughout, we assume that all derived EIFs have finite second moments, $`\widehat \pi_D(p|x) > c`$ for some constant $`c`$, and that $`\widehat \mu(x,p)`$ is bounded for all $`p`$ and $`x`$.

In what follows, we start with the standard consumer surplus $`(r=1)`$, where the strongest results can be established, before progressing to the inequality-aware surplus, which presents additional challenges. We focus on analyzing the estimators for the surplus of a known policy $`\pi`$. Analogous results for the behavior policy surplus $`{\cal S}(\pi_D)`$ and difference $`\Delta(\pi)`$ follow similar techniques and can be found in Appendix 15. For completeness, we additionally present the results for the DM method, which forms part of our theoretical contribution.

Analysis of Standard Consumer Surplus $`(r=1)`$

We impose three sets of technical conditions corresponding to three estimators: CPW, ACPW, and DM, although we cover assumptions for DM in Appendix 14.1 for brevity. We begin with the assumptions required for the CPW estimator.

Required Assumptions

Assumption 3 (Assumptions required for the CPW). *(i)

$`\sqrt{\mathbb{E}\left[\widehat \omega(X,P)-\omega(X,P)\right]^2}=o_p(1)`$

, where $`\omega(x,p)\equiv\frac{F^\pi(p | x)}{\pi_D(p | x)}`$, and

$`\widehat \omega(x,p)\equiv\frac{F^\pi(p | x)}{\widehat\pi_D(p | x)}`$

is the estimator of $`\omega(x,p)`$.

(ii) The behavior policy is estimated using a function class that

satisfies the Donsker property.

(iii) There exist basis functions $`\phi(x,p) \in \mathbb{R}^L`$ and a

vector $`\beta \in \mathbb{R}^L`$ such that

\begin{gather}

\label{eq:approximation}

\sup_{x,p} |\mu(x,p)-\phi(x,p)^\top \beta | =O(L^{-s/d}),

\end{gather}where $`s`$ is a fixed positive constant and $`O(\cdot)`$ is the

standard big-$`O`$ term.

(iv) The estimated CPW weights satisfy

\begin{gather*}

\left \lVert\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \phi^\pi(X_i)- \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \widehat \omega(X_i,P_i)\phi(X_i,P_i) \right \rVert_2 =o_p(n^{-1/2}),

\end{gather*}where $`\| \cdot \|_2`$ is denoted as Euclidean norm, $`\phi(\cdot, \cdot)`$ is the basis function that satisfy Equation [eq:approximation], and $`\phi^\pi(x)=\int^\infty_0 \pi(p | x) \int_p \phi(x,z)dz dp`$.*

Assumption 3 (i) is relatively mild, as it merely requires $`\widehat \pi_D`$ to be consistent, with no rate specified. Assumption 3 (ii) imposes a complexity (size) constraint on the function class used for estimating the behavior policy. Before further discussing this assumption, we formally define the Donsker class as follows.

Definition 2 ($`P`$-Donsker Class). Let $`(\mathcal{X}, \mathcal{A}, P)`$ be a probability space and $`\mathcal{F}`$ be a class of measurable functions. We denote by $`L_2(P)`$ the space of all measurable functions that are square-integrable with respect to $`P`$. The associated $`L_2`$-norm is defined as $`\|\cdot \|_{P,2}`$. We define the following components to characterize the complexity of $`\mathcal{F}`$:

-

Brackets: for any two functions $`l, u \in L_2(P)`$, the bracket $`[l, u]`$ is the set of functions $`\{f : l(x) \leq f(x) \leq u(x) \text{ for all } x \in \mathcal{X}\}`$. An $`\epsilon`$-bracket in $`L_2(P)`$ is a bracket $`[l, u]`$ such that $`\|u - l\|_{P,2} < \epsilon`$.

-

Bracketing number: the bracketing number $`N_{[]}(\epsilon, \mathcal{F}, L_2(P))`$ is the minimum number of $`\epsilon`$-brackets in $`L_2(P)`$ needed to cover $`\mathcal{F}`$.

-

*Bracketing integral: the entropy integral is defined as

MATHJ_{[]}(\delta, \mathcal{F}, L_2(P)) = \int_{0}^{\delta} \sqrt{\log N_{[]}(\epsilon, \mathcal{F}, L_2(P))} \, d\epsilon ```*Click to expand and view more

Assume that there exists a measurable function $`F`$ such that $`|f(x)| \leq F(x)`$ for all $`f \in \mathcal{F}`$ and $`x \in \mathcal{X}`$, with $`\mathbb{E}(F^2) < \infty`$. Then the class $`\mathcal{F}`$ is called a $`P`$-Donsker class if $`J_{[]}(\delta, \mathcal{F}, L_2(P)) < \infty`$, for some $`\delta > 0`$.

Intuitively speaking, a Donsker class is a collection of functions that is not too large or too complex. This helps ensure that the average behavior of these functions becomes stable as we collect more data. Many commonly used machine learning models form Donsker classes. These include standard parametric models such as linear and generalized linear models, as well as nonparametric regression methods like wavelets and tensor product B-splines (see Section 6 of for a review). However, it is important to note that many modern black-box machine learning algorithms do not inherently satisfy the Donsker property. High-capacity models, such as over-parameterized deep neural networks, unpruned random forests, or gradient boosting machines, often operate in function spaces with massive complexity. Without explicit structural constraints (e.g., sparsity, norm regularization, or bounded depth), these classes can be too rich to admit a uniform Central Limit Theorem. Nevertheless, under specific technical conditions, even these state-of-the-art models can be shown to satisfy the Donsker property. For instance, discusses conditions for decision trees, while (Lemma 4) and (Lemma 5) provide the necessary sparsity and boundedness constraints for decision trees and neural networks, respectively, to remain within the Donsker regime.

Assumption 3(iii) is commonly adopted in the policy evaluation literature, see, for example, . When the demand function $`\mu(x,p)`$ lies within a Hölder or Sobolev smoothness class, Assumption 3(iii) is automatically satisfied, with $`s`$ as the Hölder smoothness parameter of the function $`\mu(x,p)`$. In such cases, one can approximate $`\mu(x,p)`$ using wavelet or tensor product B-spline basis functions. It can be observed from Equation [eq:approximation] that the smoother the function and the greater the number of basis functions, the smaller the approximation error.

Assumption 3(iv) requires the estimated CPW weight to have the approximately balancing property. It is relatively mild, since Lemma 1 (see Appendix 10.2) establishes that the true weight satisfies

\begin{align*}

\mathbb{E}\left[\phi^\pi(X) - \omega(X,P)\phi(X,P)\right] = 0.

\end{align*}In fact, exact balance over empirical data, meaning equality with $`0`$ rather than convergence at rate $`o_p(n^{-1/2})`$, can be achieved when the number of basis functions $`L`$ is fixed . Note that the $`o_p(n^{-1/2})`$ balance can still be achieved in settings where the number of basis functions $`L`$ grows with the sample size , and one can similarly follow the approach therein to construct a CPW estimator that satisfies Assumption 3 (iv).

Next, we present assumptions to show the asymptotic properties of ACPW.

Assumption 4 (Assumptions required for the ACPW). *Assume $`\pi_D(p \, | \,x)>c`$, for all $`p \in {\cal P}`$, and every $`x`$, for some constant $`c`$. In addition, suppose that the estimators for the demand function and the behavior policy are constructed using the cross-fitting procedure, and that they achieve the following convergence rate for $`k = 1, \cdots, K`$:

\begin{align}

\label{eq: product rate}

\sqrt{\mathbb{E}[(\widehat \mu^{-(k)}(X,P)-\mu(X,P))^2]} =O_p(n^{-\alpha_1}), \mbox{ and } \; \sqrt{\mathbb{E}[(\widehat \omega^{-(k)}(X,P)-\omega(X,P))^2]}=O_p(n^{-\alpha_2}),

\end{align}with $`\alpha_1, \alpha_2>0`$, and $`\alpha_1+\alpha_2>1/2`$.*

Assumption 4 allows the nuisances to be estimated at rates slower than the parametric $`O_p(n^{-1/2})`$, making it a mild condition. For example, it is satisfied when both estimators achieve $`o_p(n^{-1/4})`$, thereby accommodating flexible machine learning methods for consumer surplus estimation. Given these assumptions, we are able to show asymptotic normality of the proposed estimators.

Asymptotic Normality

Theorem 4. *Under Assumptions

1 and

2, the following results hold:

(i) Suppose Assumption 3 holds, and further assume that the

number of basis functions $`L`$ satisfies $`L \gg n^{d/2s}`$, then

\begin{gather*}

\sqrt{n} \left( \widehat {\cal S}_{CPW}(\pi)-{\cal S}(\pi)\right)\rightarrow\mathcal{N}\left(0,\Sigma(\pi) \right),

\end{gather*}where $`\Sigma(\pi)\equiv \mbox{Var}[\psi^\pi(\cal {D})]`$, and $`\psi^\pi(\cal {D})`$ is the EIF for $`{\cal S}(\pi)`$ given by Equation [eqn: eif].*

*(ii) Under Assumption 4,

\begin{gather*}

\sqrt{n} \left( \widehat {\cal S}_{ACPW}(\pi)-{\cal S}(\pi)\right)\rightarrow \mathcal{N}\left(0,\Sigma(\pi) \right),

\end{gather*}

```*

*(iii) Under Assumption <a href="#asmp: dm" data-reference-type="ref"

data-reference="asmp: dm">5</a> in Appendix

<a href="#sec:assumptions_DM" data-reference-type="ref"

data-reference="sec:assumptions_DM">14.1</a>,

``` math

\begin{gather*}

\sqrt{n} \left( \widehat {\cal S}_{DM}(\pi)-{\cal S}(\pi)\right)\rightarrow \mathcal{N}\left(0,\Sigma(\pi) \right).

\end{gather*}

```*

</div>

This is proved in Appendix

<a href="#sec:normality_target" data-reference-type="ref"

data-reference="sec:normality_target">14</a>. Theorem

<a href="#thm:dr rate" data-reference-type="ref"

data-reference="thm:dr rate">4</a> shows that all three proposed

estimators achieve the semiparametric efficiency bound, i.e., among all

regular asymptotically linear estimators, they attain the minimal

asymptotic variance $`\psi^\pi(\cal {D})`$. They also converge to the

same asymptotic distribution. However, the conditions required for

attaining the efficiency bound differ across methods. In particular, the

DM and CPW estimators rely on their respective nuisance functions being

estimated within a Donsker class, together with additional requirements

such as smoothness and balancing. In contrast, the ACPW estimator avoids

such high-level conditions, requiring only a mild product-rate

assumption and sample splitting during estimation. This is significant

as it ensures that the ACPW estimator can have a fast convergence rate

even when the DM and CPW methods have slower convergence rates (such as

with more complicated machine learning estimators). As a result, ACPW

has the flexibility to be used across a wider range of settings for

surplus estimation.

It is also instructive to discuss why the plug-in estimators such as CPW

estimator can achieve the asymptotic normality with the same rate and

variance as ACPW. The intuition is that Assumption 3 elevates the CPW

estimator from an inverse-probability weighting method to a calibrated

estimator. The empirical average of the de-biasing term in

$`\psi^\pi(\mathcal D)`$ (i.e.,

$`\int_0^\infty\pi(p | X) \int_{p}^\infty \mu(X, z)dzdp - \frac{F^\pi(P | X)}{\pi_D(P | X)}\mu(X,P)`$)

is asymptotically negligible under Assumption 3. Specifically,

Assumption 3(iv) enforces a constraint that forces the estimated weights

to balance the empirical moments of the historical data against the

target policy, using the basis functions $`\phi`$ as the balancing

features. This connects directly to the demand model: since Assumption

3(iii) guarantees that the true demand function $`\mu`$ can be

accurately approximated by a linear combination of these same basis

functions, balancing $`\phi`$ effectively balances the demand function

itself. Quantitatively, provided the number of basis functions $`L`$ is

chosen sufficiently large (specifically $`L \gg n^{d/2s}`$), the

approximation error becomes negligible at the root-$`n`$ scale

($`o(n^{-1/2})`$). By calibrating the weights to remove the variation

explained by the covariates, the CPW estimator achieves the same error

reduction as explicitly subtracting a control variate. Consequently, it

attains the same semiparametric efficiency bound and asymptotic

normality as the doubly robust ACPW estimator, even without explicitly

estimating the demand function.

An analogous result to Theorem

<a href="#thm:dr rate" data-reference-type="ref"

data-reference="thm:dr rate">4</a> applies to the estimation of the

behavior policy surplus, $`{\cal S}(\pi_D)`$, and the difference in

surplus $`\Delta(\pi)`$. For a complete statement, see Theorem

<a href="#thm:dr rate behavior" data-reference-type="ref"

data-reference="thm:dr rate behavior">6</a> and Corollary

<a href="#thm:dr rate behavior difference" data-reference-type="ref"

data-reference="thm:dr rate behavior difference">1</a> in Appendix

<a href="#sec:behavioral_theory" data-reference-type="ref"

data-reference="sec:behavioral_theory">15</a>.

### Confidence Intervals

Based on the asymptotic normality established in Theorem

<a href="#thm:dr rate" data-reference-type="ref"

data-reference="thm:dr rate">4</a>, we can construct valid confidence

intervals for $`{\cal S}(\pi)`$. A key theoretical insight from our

analysis is that, although $`\widehat {\cal S}_{CPW}`$,

$`\widehat {\cal S}_{ACPW}`$, and $`\widehat {\cal S}_{DM}`$ rely on

different modeling strategies, they are all asymptotically linear

estimators governed by the same efficient influence function,

$`\psi^{\pi}(\mathcal{D})`$. Consequently, they share the same

asymptotic variance,

$`\Sigma(\pi) = \text{Var}(\psi^{\pi}(\mathcal{D}))`$.

To perform inference, we estimate this variance using the empirical

second moment of the estimated EIF. This provides a unified approach to

variance estimation, since regardless of whether the point estimate is

derived via direct modeling or propensity weighting, the uncertainty is

quantified by the variability of the underlying influence function. The

variance estimators for each method are given by:

``` math

\begin{align*}

&\widehat \Sigma_{CPW}(\pi)= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \left[\int_0^\infty\pi(p | X_i) \int_{p}^\infty \widehat \mu(X_i,z) dzdp + \frac{F^\pi(P_i | X_i)}{\widehat\pi_D (P_i | X_i)}(Y_i - \widehat \mu(X_i,P_i))-\widehat {\cal S}_{CPW}(\pi)\right]^2,\\

&\widehat \Sigma_{ACPW}(\pi)= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \bigg[\int_0^\infty\pi(p | X_i) \int_{p}^\infty \widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i,z) dzdp \\

&\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad + \frac{F^\pi(P_i | X_i)}{\widehat\pi_D^{-k(i)} (P_i | X_i)}(Y_i - \widehat \mu^{-k(i)}(X_i,P_i))-\widehat {\cal S}_{ACPW}(\pi)\bigg]^2,\\

& \widehat \Sigma_{DM}(\pi)= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \left[\int_0^\infty\pi(p | X_i) \int_{p}^\infty \widehat \mu(X_i,z) dzdp + \frac{F^\pi(P_i | X_i)}{\widehat\pi_D (P_i | X_i)}(Y_i - \widehat \mu(X_i,P_i))-\widehat {\cal S}_{DM}(\pi)\right]^2.

\end{align*}Note that for $`\widehat \Sigma_{CPW}(\pi)`$, we utilize the estimated demand function $`\widehat \mu`$ to construct the variance estimator, even though it is not used for the point estimate $`\widehat {\cal S}_{CPW}(\pi)`$ itself. Similarly, for $`\widehat \Sigma_{CPW}(\pi)`$, we utilize the estimated propensity weights $`\widehat \pi_D`$ to construct the variance estimator. The following proposition establishes the consistency of these variance estimators.

Proposition 2. *Under the assumptions of Theorem 4, the following consistency results hold:

\begin{gather*}

|\widehat \Sigma_{CPW}(\pi) - \Sigma(\pi)| = o_p(1), \quad

|\widehat \Sigma_{ACPW}(\pi) - \Sigma(\pi)| = o_p(1), \quad

\text{and} \quad |\widehat \Sigma_{DM}(\pi) - \Sigma(\pi)| = o_p(1).

\end{gather*}

```*

</div>

This is proved in Appendix

<a href="#sec:variance_consistency" data-reference-type="ref"

data-reference="sec:variance_consistency">16</a>. Accordingly, a

$`(1-\alpha)`$ confidence interval for $`\mathcal S(\pi)`$ can be

constructed using any of the three estimators. For example, using the

ACPW estimator, the interval is given by:

``` math

\begin{equation*}

\left[\widehat{\mathcal S}_{ACPW}(\pi) \; \pm\; z_{1-\alpha/2} \sqrt{\widehat \Sigma_{ACPW}(\pi)/n} \right],

\end{equation*}where $`z_{1-\alpha/2}`$ denotes the upper $`(1-\alpha/2)`$-quantile of the standard normal distribution. In large samples, this interval contains the true value $`\mathcal S(\pi)`$ with probability $`(1-\alpha)`$. Intervals for the CPW and DM estimators are constructed analogously. This allows firms and regulators to establish whether surplus improvements or declines are statistically meaningful, and is important for rigorous evaluation.

Asymptotic Normality of Inequality-Aware Surplus $`(r\neq 1)`$

We next establish the asymptotic normality of $`\widehat {\cal S}^r(\pi)`$ and show that it attains the semiparametric efficiency bound.

Theorem 5. *Suppose that Assumptions 1, 2, and 4 hold. In addition, assume that $`\alpha_1>1/4`$, then for $`r\neq 0`$, we have

\begin{align*}

\sqrt{n} (\widehat {\cal S}^r(\pi)- {\cal S}^r(\pi))\rightarrow \mathcal{N}(0,\Sigma^r(\pi)),

\end{align*}where $`\Sigma^r(\pi)`$ is the variance of the EIF in Equation [eqn: eif aware].*

Theorem 5 establishes that the proposed inequality-aware estimator achieves the semiparametric efficiency bound, and is proved in Appendix 17. A key distinction of this result, compared to the aggregate surplus case ($`r=1`$) presented in Theorem 4, is the requirement that the demand model converges at a rate faster than $`n^{-1/4}`$ (i.e., $`\alpha_1 > 1/4`$). This condition is stricter than the product-rate condition ($`\alpha_1 + \alpha_2 > 1/2`$), which is sufficient for the standard ACPW estimator.

This divergence arises from the nonlinearity of the target functional $`\mathcal{S}^r(\pi) = \mathbb{E}[(\cdot)^r]`$ when $`r \neq 1`$. In the analysis of the linear aggregate surplus ($`r=1`$), the remainder term of the estimator takes the form of a cross-product of errors between the demand and propensity models, $`(\widehat \omega - \omega)(\widehat{\mu} - \mu)`$. This product structure allows for a trade-off in accuracy between the two nuisance functions, underpinning the double robustness property. In contrast, expanding the nonlinear functional $`\mathcal{S}^r(\pi)`$ via a second-order Von Mises expansion introduces a purely quadratic error term associated with the curvature of the functional. Consequently, the remainder term includes a component proportional to $`\|\hat{\mu} - \mu\|^2`$. For the estimator to be $`\sqrt{n}`$-consistent and asymptotically normal, this quadratic term must vanish faster than $`n^{-1/2}`$. This necessitates that $`\|\hat{\mu} - \mu\| = o_p(n^{-1/4})`$, forcing the demand estimator to satisfy a stricter individual convergence rate. This mathematical necessity aligns perfectly with our observation that the IA-ACPW estimator is only single-robust: because the propensity score cannot cancel out the quadratic error introduced by the nonlinearity, the consistency of the final estimator becomes dependent on the quality of the demand model.