Improved Object-Centric Diffusion Learning with Registers and Contrastive Alignment

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Improved Object-Centric Diffusion Learning with Registers and Contrastive Alignment- ArXiv ID: 2601.01224

- Date: 2026-01-03

- Authors: Bac Nguyen, Yuhta Takida, Naoki Murata, Chieh-Hsin Lai, Toshimitsu Uesaka, Stefano Ermon, Yuki Mitsufuji

📝 Abstract

Slot Attention (SA) with pretrained diffusion models has recently shown promise for object-centric learning (OCL), but suffers from slot entanglement and weak alignment between object slots and image content. We propose Contrastive Object-centric Diffusion Alignment (CODA), a simple extension that (i) employs register slots to absorb residual attention and reduce interference between object slots, and (ii) applies a contrastive alignment loss to explicitly encourage slot-image correspondence. The resulting training objective serves as a tractable surrogate for maximizing mutual information (MI) between slots and inputs, strengthening slot representation quality. On both synthetic (MOVi-C/E) and real-world datasets (VOC, COCO), CODA improves object discovery (e.g., +6.1% FG-ARI on COCO), property prediction, and compositional image generation over strong baselines. Register slots add negligible overhead, keeping CODA efficient and scalable. These results indicate potential applications of CODA as an effective framework for robust OCL in complex, real-world scenes.💡 Summary & Analysis

1) **Register-augmented slot diffusion**. CODA introduces register slots that are independent of the input image, acting as attention sinks to absorb residual attention and keep object slots focused on meaningful associations. 2) **Mitigating text-conditioning bias**. By fine-tuning key, value, and output projections in cross-attention layers, CODA reduces biases inherited from pre-trained diffusion models, ensuring more accurate slot-image alignment. 3) **Contrastive alignment objective**. A contrastive loss ensures slots capture concepts present in the image, improving overall representation quality by maximizing mutual information between inputs and slots.📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

Introduction

Object-centric learning (OCL) aims to decompose complex scenes into structured, interpretable object representations, enabling downstream tasks such as visual reasoning , causal inference , world modeling , robotic control , and compositional generation . Yet, learning such compositional representations directly from images remains a core challenge. Unlike text, where words naturally form composable units, images lack explicit boundaries for objects and concepts. For example, in a street scene with pedestrians, cars, and traffic lights, a model must disentangle these entities without labels and also capture their spatial relations (e.g., a person crossing in front of a car). Multi-object scenes add further complexity: models must not only detect individual objects but also capture their interactions. As datasets grow more cluttered and textured, this becomes even harder. Manual annotation of object boundaries or compositional structures is costly, motivating the need for fully unsupervised approaches such as Slot Attention (SA) . While effective in simple synthetic settings, SA struggles with large variations in real-world images, limiting its applicability to visual tasks such as image or video editing.

Combining SA with diffusion models has recently pushed forward progress in OCL . In particular, Stable-LSD and SlotAdapt achieve strong object discovery and high-quality generation by leveraging pretrained diffusion backbones such as Stable Diffusion (SD). Nevertheless, these approaches still face two key challenges. First, as illustrated in 1 (left), they often suffer from slot entanglement, where a slot encodes features from multiple objects or fragments of them, leading to unfaithful single-slot generations. This entanglement degrades segmentation quality and prevents composable generation to novel scenes and object configurations. Second, they exhibit weak alignment, where slots fail to consistently correspond to distinct image regions, especially on real-world images. As shown in our experiments, slots often suffer from over-segmentation (splitting one object into multiple slots), under-segmentation (merging multiple objects into one slot), or inaccurate object boundaries. Together, these two issues reduce both the accuracy of object-centric representations and their utility for compositional scene generation.

In response, we propose Contrastive Object-centric Diffusion

Alignment (CODA), a slot-attention model that uses a pretrained

diffusion decoder to reconstruct the input image. CODA augments the

model with register slots, which absorb residual attention and reduce

interference between object slots, and a contrastive objective, which

explicitly encourages slot–image alignment. As illustrated

in 1 (right), CODA faithfully

generates images from both individual slots as well as their

compositions. In summary, the contributions of this paper can be

outlined as follows.

-

Register-augmented slot diffusion. We employ register slots that are independent of the input image into slot diffusion. Although these register slots carry no semantic information, they act as attention sinks, absorbing residual attention mass so that semantic slots remain focused on meaningful object–concept associations. This reduces interference between object slots and mitigating slot entanglement (4.1).

-

Mitigating text-conditioning bias. To reduce the influence of text-conditioning biases inherited from pretrained diffusion models, we finetune the key, value, and output projections in cross-attention layers. This adaptation further improves alignment between slots and visual content, ensuring more faithful object-centric decomposition (4.2).

-

Contrastive alignment objective. We propose a contrastive loss that ensures slots capture concepts present in the image (4.3). Together with the denoising loss, our training objective can be viewed as a tractable surrogate for maximizing the mutual information (MI) between inputs and slots, improving slot representation quality (4.4).

-

Comprehensive evaluation. We demonstrate that

CODAoutperforms existing unsupervised diffusion-based approaches across synthetic and real-world benchmarks in object discovery (5.1), property prediction (5.2), and compositional generation (5.3). On the VOC dataset,CODAimproves instance-level object discovery by +3.88% mBO$`^i`$ and +3.97% mIoU$`^i`$, and semantic-level object discovery by +5.72% mBO$`^c`$ and +7.00% mIoU$`^c`$. On the COCO dataset, it improves the foreground Adjusted Rand Index (FG-ARI) by +6.14%.

style="width:49.0%" />

style="width:49.0%" />  style="width:49.0%" />

style="width:49.0%" />

Related work

Object-centric learning (OCL). The goal of OCL is to discover compositional object representations from images, enabling systematic generalization and stronger visual reasoning . Learning directly from raw pixels is difficult, so previous works leveraged weak supervision (e.g., optical flow , depth , text , pretrained features ), or auxiliary losses that guide slot masks toward moving objects . Scaling OCL to complex datasets has been another focus: DINOSAUR reconstructed self-supervised features to segment real-world images, and FT-DINOSAUR extended this via encoder finetuning for strong zero-shot transfer. SLATE and STEVE combined discrete VAE tokenization with slot-conditioned autoregressive transformers, while SPOT improved autoregressive decoders using patch permutation and attention-based self-training. Our work builds on SA, but does not require any additional supervision.

Diffusion models for OCL. Recent works explored diffusion models as

slot decoders in OCL. Different methods vary in how diffusion models are

integrated. For example, SlotDiffusion trained a diffusion model from

scratch, while Stable-LSD , GLASS , and SlotAdapt leveraged pretrained

diffusion models. Although pretrained models offer strong generative

capabilities, they are often biased toward text-conditioning. To address

this issue, GLASS employed cross-attention masks as pseudo-ground truth

to guide SA training. Unlike GLASS, CODA does not rely on supervised

signals such as generated captions. SlotAdapt introduced adapter layers

to enable new conditional signals while keeping the base diffusion model

frozen. In contrast, CODA simply finetunes key, value, and output

projections in cross-attention, without introducing additional layers.

This ensures full compatibility with off-the-shelf diffusion models

while remaining conceptually simple and computationally efficient.

Contrastive learning for OCL. Training SA with only reconstruction

losses often leads to unstable or inconsistent results . To improve

robustness, several works introduced contrastive objectives. For

example, SlotCon applied the InfoNCE loss across augmented views of

the input image to enforce slot consistency. used contrastive loss to

enforce the temporal consistency for video object-centric models. In

contrast, CODA tackles compositionality by aligning images with their

slot representations, enabling faithful generation from both individual

slots and their combinations. Unlike , who explicitly maximize

likelihood under random slot mixtures and thus directly tune for

compositional generation, CODA focuses on enforcing slot–image

alignment; its gains in compositionality arise indirectly from improved

disentanglement. Although CODA uses a negative loss term, similar to

negative guidance in diffusion models , the roles are fundamentally

different. apply negative guidance during sampling to steer the

denoising trajectory, whereas CODA uses a contrastive loss during

training to improve slot–image alignment.

Background

Slot Attention (SA). Given input features $`{\mathbf{f}}\in \mathbb{R}^{M\times D_\mathrm{input}}`$ of an image, the goal of OCL is to extract a sequence $`{\mathbf{s}}\in \mathbb{R}^{N \times D_{\mathrm{slot}}}`$ of $`N`$ slots, where each slot is a $`D_{\mathrm{slot}}`$-dimensional vector representing a composable concept. In SA, we start with randomly initialized slots as $`{\mathbf{s}}^{(0)} \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times D_\mathrm{slot}}`$. Once initialized, SA employs an iterative mechanism to refine the slots. In particular, slots serve as queries, while the input features serve as keys and values. Let $`q`$, $`k`$, and $`v`$ denote the respective linear projections used in the attention computation. Given the current slots $`{\mathbf{s}}^{(t)}`$ and input features $`{\mathbf{f}}`$, the update rule can be formally described as

\begin{align*}

{\mathbf{s}}^{(t + 1)} = \mathtt{GRU} ({\mathbf{s}}^{(t)}, {{\mathbf{u}}^{(t)}}) \quad \text{where} \quad {\mathbf{u}}^{(t)} = \mathtt{Attention}(q({\mathbf{s}}^{(t)}), k({\mathbf{f}}), v({\mathbf{f}})) \,. %\rvm^{(t)}=\mathtt{softmax}(q(\rvs^{(t)})\dot k(\rvf)^\top/\,.

\end{align*}Here, attention readouts are aggregated and refined through a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU). Unlike self-attention , the $`\mathtt{softmax}`$ function in SA is applied along the slot axis, enforcing competition among slots. This iterative process is repeated for several steps, and the slots from the final iteration are taken as the slot representations. Finally, these slots are passed to a decoder trained to reconstruct the input image. The slot decoder can take various forms, such as an MLP or an autoregressive Transformer . Interestingly, recent works have shown that using (latent) diffusion models as slot decoders proves to be particularly powerful and effective in OCL.

Latent diffusion models (LDMs). Diffusion models are probabilistic models that sample data by gradually denoising Gaussian noise . The forward process progressively corrupts data with Gaussian noise, while the reverse process learns to denoise and recover the original signal. To improve efficiency, SD performs this process in a compressed latent space rather than pixel space. Concretely, a pretrained autoencoder maps an image to a latent vector $`{\mathbf{z}}\in \mathcal{Z}`$, where a U-Net denoiser iteratively refines noisy latents. Consider a variance preserving process that mixes the signal $`{\mathbf{z}}`$ with Gaussian noise $`{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}\sim \mathcal{N}(0, \mathbf{I})`$, given by $`{\mathbf{z}}_\gamma = \sqrt{\sigma(\gamma)} {\mathbf{z}}+ \sqrt{\sigma(-\gamma)} {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}`$, where $`\sigma(.)`$ is the sigmoid function and $`\gamma`$ is the log signal-to-noise ratio. Let $`{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{c}})`$ denote a denoiser parameterized by $`{\boldsymbol{\theta}}`$ that predicts the Gaussian noise $`{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}`$ from noisy latents $`{\mathbf{z}}_\gamma`$, conditioned on an external signal $`{\mathbf{c}}`$. In SD, conditioning is implemented through cross-attention, which computes attention between the conditioning signal and the features produced by U-Net. Training diffusion models is formulated as a noise prediction problem, where the model learns to approximate the true noise $`{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}`$ added during the forward process,

\begin{align*}

\min_{{\boldsymbol{\theta}}} \quad \mathbb{E}_{({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{c}}), {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}, \gamma} \left[ \| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{c}})\|^2_2 \right] \,

\end{align*}with $`({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{c}})`$ sampled from a data distribution $`p({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{c}})`$. Once training is complete, sampling begins from random Gaussian noise, which is iteratively refined using the trained denoiser.

Proposed method

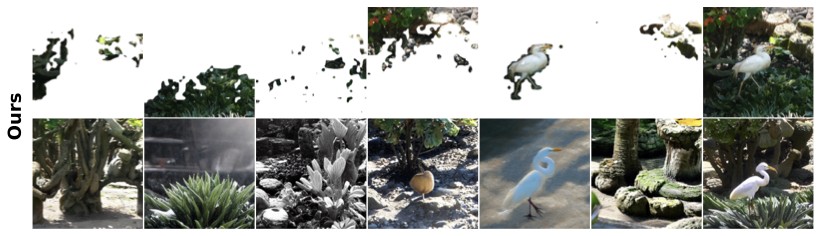

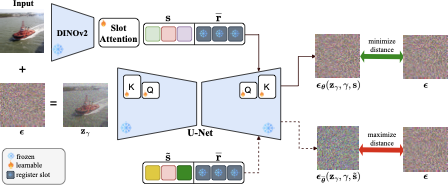

As summarized in 2, CODA builds on diffusion-based

OCL by extracting slot sequences from DINOv2 features with SA and

decoding them using a pretrained SD v1.5 . To address the challenges of

slot entanglement and weak alignment, CODA introduces three

components: (i) register slots to absorb residual attention and keep

object slots disentangled, (ii) finetuning of cross-attention keys and

queries to mitigate text-conditioning bias, and (iii) a contrastive

alignment loss to explicitly align images with their slots. These

modifications yield disentangled, well-aligned slots that enable

faithful single-slot generation and compositional editing.

style="width:90.0%" />

style="width:90.0%" />

CODA. The input

image is encoded with DINOv2 and processed by Slot Attention (SA) to

produce slot representations. The semantic slots s, together with register

slots $\overline{{\mathbf{r}}}$, serve

as conditioning inputs for the cross-attention layers of a pretrained

diffusion model. SA is trained jointly with the key, value, and output

projections of the cross-attention layers using a denoising objective

that minimizes the mean squared error between the true and predicted

noise. In addition, a contrastive loss is applied to align each image

with its corresponding slot representations.Register slots

An ideal OCL model should generate semantically faithful images when conditioned on arbitrary subsets of slots. In practice, however, most diffusion-based OCL methods fall short of this goal. As discussed in the introduction, decoding a single slot typically yields distorted or semantically uninformative outputs. Although reconstructions from the full set of slots resemble the input images, this reliance reveals a strong interdependence among slots (see 4 for more detailed analysis). Such slot entanglement poses a challenge for compositionality, particularly when attempting to reuse individual concepts in novel configurations.

To address this problem, we add input-independent register slots that act as residual attention sinks, absorbing shared or background information and preventing object slots from mixing. Intuitively, register slots are semantically empty but structurally valid inputs, making them natural placeholders for slots that can capture residual information without competing with object representations. We obtain these register slots by passing only padding tokens through the SD text encoder, a pretrained ViT-L/14 CLIP . Formally, let $`\texttt{pad}`$ denote the padding token used to ensure fixed-length prompts in text-to-image SD. By encoding the sequence $`[\texttt{pad}, \dots, \texttt{pad}]`$ with the frozen text encoder1, we obtain a fixed-length sequence of frozen embeddings serving as register slots $`\overline{{\mathbf{r}}}`$. We also explore an alternative design with trainable register slots in 5.2, and find that while learnable registers can also mitigate slot entanglement, our simple fixed registers perform best.

Why do register slots mitigate slot entanglement? The $`\mathtt{softmax}`$ operation in cross-attention forces attention weights to sum to one across all slots. When a query from U-Net features does not strongly match any semantic slot, this constraint causes the attention mass to spread arbitrarily, weakening slot–concept associations. Register slots serve as placeholders that absorb this residual attention, giving the model extra capacity to store auxiliary information without interfering with semantic slots. This leads to cleaner and more coherent slot-to-concept associations. Consistent with this view, we observe in 3 that a substantial fraction of attention mass is allocated to register slots. A similar phenomenon has been reported in language models, where $`\mathtt{softmax}`$ normalization causes certain initial tokens to act as attention sinks , absorbing unnecessary attention mass and preventing it from distorting meaningful associations.

In a related approach, introduced an additional embedding by pooling from either generated slots or image features. Unlike our method, their embedding is injected directly into the cross-attention layers and is explicitly designed to capture global scene information. While this might provide contextual guidance, it ties the model to input-specific features, reducing flexibility in reusing slots across arbitrary compositions. In contrast, our register slots are independent of the input image, making them better suited for compositional generation.

Finetuning cross-attention keys and queries

SD is trained on large-scale image–text pairs, so directly using its pretrained model as a slot decoder introduces a text-conditioning bias: the model expects text embeddings and tends to prioritize language-driven semantics over slot-level representations . This mismatch weakens the fidelity of slot-based generation. Prior works have approached this issue in different ways. For example, trained diffusion models from scratch, thereby removing text bias but sacrificing generative quality due to limited training data. More recently, proposed adapter layers to align slot representations with pretrained diffusion models, retaining generation quality but still relying on text-conditioning features.

In contrast, we adopt a lightweight adaptation strategy: finetuning only the key, value, and output projections in cross-attention layers . This allows the model to better align slots with visual content, mitigating text-conditioning bias while preserving the expressive power of the pretrained diffusion backbone. We find this minimal modification sufficient to eliminate the bias introduced by text conditioning. Unlike the previous approaches, our method is both computationally and memory efficient, requiring no additional layers or architectural modifications. This makes our approach not only effective but also conceptually simple. Formally, let $`{\boldsymbol{\phi}}`$ denote the parameters of SA, the denoising objective for diffusion models can be written as

\begin{align}

\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{dm}} ({\boldsymbol{\phi}}, {\boldsymbol{\theta}}) = \mathbb{E}_{({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{s}}), {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}, \gamma} \left[ \| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{s}}, \overline{{\mathbf{r}}})\|^2_2 \right] \,, \label{eq:denoising}

\end{align}where $`({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{s}})`$ are sampled from $`p({\mathbf{z}})p_{{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}({\mathbf{s}}\mid {\mathbf{z}})`$. In practice, $`{\mathbf{s}}`$ is not computed directly from $`{\mathbf{z}}`$, but rather from DINOv2 features of the image corresponding to $`{\mathbf{z}}`$. The U-Net is conditioned on the concatenation $`({\mathbf{s}}, \overline{{\mathbf{r}}})`$ of semantic slots $`{\mathbf{s}}`$ and register slots $`\overline{{\mathbf{r}}}`$. During training, the parameters of SA are optimized jointly with the finetuned key, value, and output projections of SD, while other parameters are kept frozen.

Contrastive alignment

The goal of OCL is to learn composable slots that capture distinct concepts from an image. However, in diffusion-based OCL frameworks, slot conditioning only serves as auxiliary information for the denoising loss, providing no explicit supervision to ensure that slots capture concepts present in the image. As a result, slots may drift toward arbitrary or redundant representations, limiting their interpretability and compositionality.

To address this, we propose a contrastive alignment objective that explicitly aligns slots with image content while discouraging overlap between different slots. Intuitively, the model should assign high likelihood to the correct slot representations and low likelihood to mismatched (negative) slots. Concretely, in addition to the standard denoising loss in [eq:denoising], we introduce a contrastive loss defined as the negative of denoising loss evaluated with negative slots $`\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}`$:

\begin{align}

\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{cl}}({\boldsymbol{\phi}}) = -\mathbb{E}_{({\mathbf{z}}, \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}), {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}, \gamma} \left[ \| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}_{\overline{{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}} ({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}, \overline{{\mathbf{r}}})\|^2_2 \right] \,, \label{eq:contrastive}

\end{align}where $`({\mathbf{z}}, \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}})`$ are sampled from $`p({\mathbf{z}})q_{{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid{\mathbf{z}})`$ and $`\overline{{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}`$ denotes stop-gradient parameters of $`{\boldsymbol{\theta}}`$. Minimizing [eq:denoising] increases likelihood under aligned slots, while minimizing [eq:contrastive] decreases likelihood under mismatched slots. We freeze the diffusion decoder and update only the SA module in [eq:contrastive], preventing the decoder from trivially reducing contrastive loss by altering its generation process. This ensures that improvements come from better slot representations rather than shortcut solutions. As confirmed by our ablations (see 5), unfreezing the decoder leads to unstable training and degraded performance across all metrics.

Finally,

combining [eq:denoising,eq:contrastive],

the overall training objective of CODA is defined as

\begin{align}

\mathcal{L}({\boldsymbol{\phi}}, {\boldsymbol{\theta}}) = \mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{dm}} ({\boldsymbol{\phi}}, {\boldsymbol{\theta}}) + \lambda_{\mathrm{cl}} \mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{cl}}({\boldsymbol{\phi}}) \,, \label{eq:total_loss}

\end{align}where $`\lambda_{\mathrm{cl}} \ge 0`$ controls the trade-off between the denoising and contrastive terms. We study the effect of varying $`\lambda_{\mathrm{cl}}`$ in 5.4. This joint objective forms a contrastive learning scheme that acts as a surrogate for maximizing the MI between slots and images, as further discussed in 4.4.

Strategy for composing negative slots. A straightforward approach for obtaining negative slots is to sample them from unrelated images. However, such negatives are often too trivial for the decoder, providing little useful gradient signal. To address this, we construct hard negatives—more informative mismatches that push the model to refine its representations more effectively . Concretely, given two slot sequences, $`{\mathbf{s}}`$ and $`{\mathbf{s}}'`$, extracted from distinct images $`{\mathbf{x}}`$ and $`{\mathbf{x}}'`$, we form negatives for $`{\mathbf{x}}`$ by randomly replacing a subset of slots in $`{\mathbf{s}}`$ with slots from $`{\mathbf{s}}'`$. This produces mixed slot sets that only partially match the original image, creating harder and more instructive negative examples. In our experiments, we replace half of the slots in $`{\mathbf{s}}`$ with those from $`{\mathbf{s}}'`$, and provide an ablation over different replacement ratios in 5.5. A remaining challenge is that naive mixing can yield invalid combinations, e.g., omitting background slots or combining objects with incompatible shapes or semantics. To mitigate this, we share the slot initialization between $`{\mathbf{x}}`$ and $`{\mathbf{x}}'`$. Because initialization is correlated with the objects each slot attends to, sampling from mutually exclusive slots under shared initialization is more likely to produce semantically valid negatives than purely random mixing .

Connection with mutual information

A central goal of our framework is to maximize MI between slots and the input image, so that slots capture representations that are both informative and compositional. To make this connection explicit, we reinterpret our training objective in [eq:total_loss] through the lens of MI. We begin by defining the optimal conditional denoiser, i.e., the minimum mean square error (MMSE) estimator of $`{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}`$ from a noisy channel $`{\mathbf{z}}_\gamma`$, which mixes $`{\mathbf{z}}`$ and $`{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}`$ at noise level $`\gamma`$, conditioned on slots $`{\mathbf{s}}`$:

\begin{align*}

\hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{s}}) = \mathbb{E}_{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}\sim p({\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}\mid {\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, {\mathbf{s}})}[{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}] = \underset{\tilde{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{s}})}{ \arg \min} \,\, \mathbb{E}_{p({\boldsymbol{\epsilon}})p({\mathbf{z}}| {\mathbf{s}})} \left[ \| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- \tilde{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{s}}) \|_2^2\right] \,.

\end{align*}By approximating the regression problem with a neural network, we obtain an estimate of the MMSE denoiser, which coincides with the denoising objective of diffusion model training. Let $`\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}`$ denote negative slots sampled from a distribution $`q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})`$. Under this setup, we state the following theorem.

Theorem 1. *Let $`{\mathbf{z}}`$ and $`{\mathbf{s}}`$ be two random variables, and let $`\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}`$ denote a sample from a distribution $`q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})`$. Consider the diffusion process $`{\mathbf{z}}_\gamma = \sqrt{\sigma(\gamma)}{\mathbf{z}}+ \sqrt{\sigma(-\gamma)}{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}`$, with $`{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}\sim \mathcal{N}(0, \mathbf{I})`$. Let $`\hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{s}})`$ denote the MMSE estimator of $`{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}`$ given $`({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{s}})`$. Then the negative of mutual information (MI) between $`{\mathbf{z}}`$ and $`{\mathbf{s}}`$ admits the following form:

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

-I({\mathbf{z}}; {\mathbf{s}}) &= \underbrace{\frac{1}{2} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \Big(\mathbb{E}_{({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{s}}), {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}} \left[\| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- \hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{s}}) \|^2 \right] - \mathbb{E}_{({\mathbf{z}}, \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}), {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}} \left[\| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- \hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}) \|^2 \right] \Big)d\gamma}_{\Delta} \\[-1.2ex]

& \quad + \mathbb{E}_{{\mathbf{z}}}\left[ D_{\mathrm{KL}}( q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})) - D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}))\right] \,.

\end{aligned}

\label{eq:mutual-loss-paper}

\end{equation}

```*

</div>

Direct optimization

of <a href="#eq:mutual-loss-paper" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="eq:mutual-loss-paper">[eq:mutual-loss-paper]</a> is

infeasible, both due to the high sample complexity and the difficulty of

evaluating the KL-divergence terms. The quantity $`\Delta`$ instead

provides a practical handle: it measures the denoising gap between

aligned and mismatched slots, and thus serves as a tractable surrogate

for MI. For this reason, we adopt the training objective

in <a href="#eq:total_loss" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="eq:total_loss">[eq:total_loss]</a>, which aligns

directly with $`\Delta`$. Since the register slots

$`\overline{{\mathbf{r}}}`$ are independent of the data, they do not

influence $`I({\mathbf{z}};{\mathbf{s}})`$. Furthermore, when

$`\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}`$ are sampled independently of $`{\mathbf{z}}`$

such that

$`q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}})=p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}})`$,

the KL-divergence terms

in <a href="#eq:mutual-loss-paper" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="eq:mutual-loss-paper">[eq:mutual-loss-paper]</a> can be

reinterpreted as dependency measures between $`{\mathbf{s}}`$ and

$`{\mathbf{z}}`$:

<div id="coro:one" class="corollary">

**Corollary 1**. *With the additional assumption

$`q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}}) = p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}})`$

in <a href="#the:mi" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="the:mi">1</a>, it follows that

``` math

\begin{align}

\Delta = -I({\mathbf{z}}; {\mathbf{s}}) - D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p({\mathbf{z}})p({\mathbf{s}}) || p({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{s}})) \, .\label{eq:sum_of_mutual_info}

\end{align}

```*

</div>

Minimizing $`\Delta`$ therefore corresponds to maximizing MI plus an

additional reverse KL-divergence

in <a href="#eq:sum_of_mutual_info" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="eq:sum_of_mutual_info">[eq:sum_of_mutual_info]</a>.

Intuitively, this reverse KL-divergence contributes by rewarding

configurations where the joint distribution

$`p({\mathbf{z}},{\mathbf{s}})`$ and the product of marginals

$`p({\mathbf{z}})p({\mathbf{s}})`$ disagree in the opposite direction of

MI. In combination with the forward KL in MI, this enforces divergence

in both directions, thereby promoting stronger statistical dependence

between $`{\mathbf{z}}`$ and $`{\mathbf{s}}`$. Proofs are provided

in <a href="#appedix:theoretical_results" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="appedix:theoretical_results">1</a>.

### Experiments

We design our experiments to address the following key questions:

**(i)** How well does `CODA` perform on unsupervised object discovery

across synthetic and real-world datasets?

(<a href="#sec:unsupervised" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="sec:unsupervised">5.1</a>) **(ii)** How effective are

the learned slots for downstream tasks such as property prediction?

(<a href="#sec:property_prediction" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="sec:property_prediction">5.2</a>) **(iii)** Does `CODA`

improve the visual generation quality of slot decoders?

(<a href="#sec:image_gneration" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="sec:image_gneration">5.3</a>) **(iv)** What is the

contribution of each component in `CODA`?

(<a href="#sec:ablation_studies" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="sec:ablation_studies">5.4</a>) To answer these

questions, `CODA` is compared against state-of-the-art fully

unsupervised OCL methods, described

in <a href="#appendix:sota-comparision" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="appendix:sota-comparision">2.2</a>.

**Datasets.** Our benchmark covers both synthetic and real-world

settings. For synthetic experiments, we use two variants of the MOVi

dataset : MOVi-C, which includes objects rendered over natural

backgrounds, and MOVi-E, which includes more objects per scene, making

it more challenging for OCL. For real-world experiments, we adopt PASCAL

VOC 2012 and COCO 2017 , two standard benchmarks for object detection

and segmentation. Both datasets substantially increase complexity

compared to synthetic ones, due to their large number of foreground

classes. VOC typically contains images with a single dominant object,

while COCO includes more cluttered scenes with two or more objects.

Further dataset and implementation details are provided

in <a href="#appendix:experimental_setup" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="appendix:experimental_setup">2</a>.

#### Object discovery

Object discovery evaluates how well slots bind to objects by predicting

a set of masks that segment distinct objects in an image. Following

prior works, we report the FG-ARI, a clustering similarity metric widely

used in this setting. However, FG-ARI alone can be misleading, as it may

favor either over-segmentation or under-segmentation , thus failing to

fully capture segmentation quality. To provide a more comprehensive

evaluation, we also report mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) and mean

Best Overlap (mBO). Intuitively, FG-ARI reflects instance separation,

while mBO measures alignment between predicted and ground-truth masks.

On real-world datasets such as VOC and COCO, where semantic labels are

available, we compute both mBO and mIoU at two levels: instance-level

and class-level. Instance-level metrics assess whether objects of the

same class are separated into distinct instances, whereas class-level

metrics measure semantic grouping across categories. This dual

evaluation reveals whether a model tends to prefer instance-based or

semantic-based segmentations.

<a href="#tab:segmentation_synthetic" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="tab:segmentation_synthetic">[tab:segmentation_synthetic]</a>

shows results on synthetic datasets. `CODA` outperforms on both MOVi-C

and MOVi-E. On MOVi-C, it improves FG-ARI by +7.15% and mIoU by +7.75%

over the strongest baseline. On MOVi-E, which contains visually complex

scenes, it improves FG-ARI by +2.59% and mIoU by +3.36%. In contrast,

SLATE and LSD struggle to produce accurate object segmentations.

<a href="#tab:segmentation_real_world" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="tab:segmentation_real_world">[tab:segmentation_real_world]</a>

presents results on real-world datasets. `CODA` surpasses the best

baseline (SlotAdapt) by +6.14% in FG-ARI on COCO. `CODA` improves

instance-level object discovery by +3.88% mBO$`^i`$ and +3.97%

mIoU$`^i`$, and semantic-level object discovery by +5.72% mBO$`^c`$ and

+7.00% mIoU$`^c`$ on VOC. Qualitative results in

<a href="#fig:segmentation_samples" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="fig:segmentation_samples">[fig:segmentation_samples]</a>

further illustrate the high-quality segmentation masks produced by

`CODA`. Overall, these results demonstrate that `CODA` consistently

outperforms diffusion-based OCL baselines by a significant margin. The

improvements highlight its ability to obtain accurate segmentation,

which facilitates compositional perception of complex scenes.

<div class="minipage">

</div>

<div class="minipage">

</div>

<div class="minipage">

</div>

<div class="minipage">

</div>

#### Property prediction

Following prior works , we evaluate the learned slot representations

through downstream property prediction on the MOVi datasets. For each

property, a separate prediction network is trained using the frozen slot

representations as input. We employ a 2-layer MLP with a hidden

dimension of 786 as the predictor, applied to both categorical and

continuous properties. Cross-entropy loss is used for categorical

properties, while mean squared error (MSE) is used for continuous ones.

To assign object labels to slots, we use Hungarian matching between

predicted slot masks and ground-truth foreground masks. This task

evaluates whether slots encode object attributes in a disentangled and

predictive manner, beyond simply segmenting objects.

We report classification accuracy for categorical properties (Category)

and MSE for continuous properties (Position and 3D Bounding Box), , as

shown in <a href="#tab:movie" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="tab:movie">[tab:movie]</a>. With the exception of *3D

Bounding Box*, `CODA` outperforms all baselines by a significant margin.

The lower performance on 3D bounding box prediction is likely due to

DINOv2 features, which lack fine-grained geometric details necessary for

precise 3D localization. Overall, these results indicate that the slots

learned by `CODA` capture more informative and disentangled object

features, leading to stronger downstream prediction performance. This

suggests that `CODA` encodes properties that enable controllable

compositional scene generation.

<div class="minipage">

</div>

<div class="minipage">

</div>

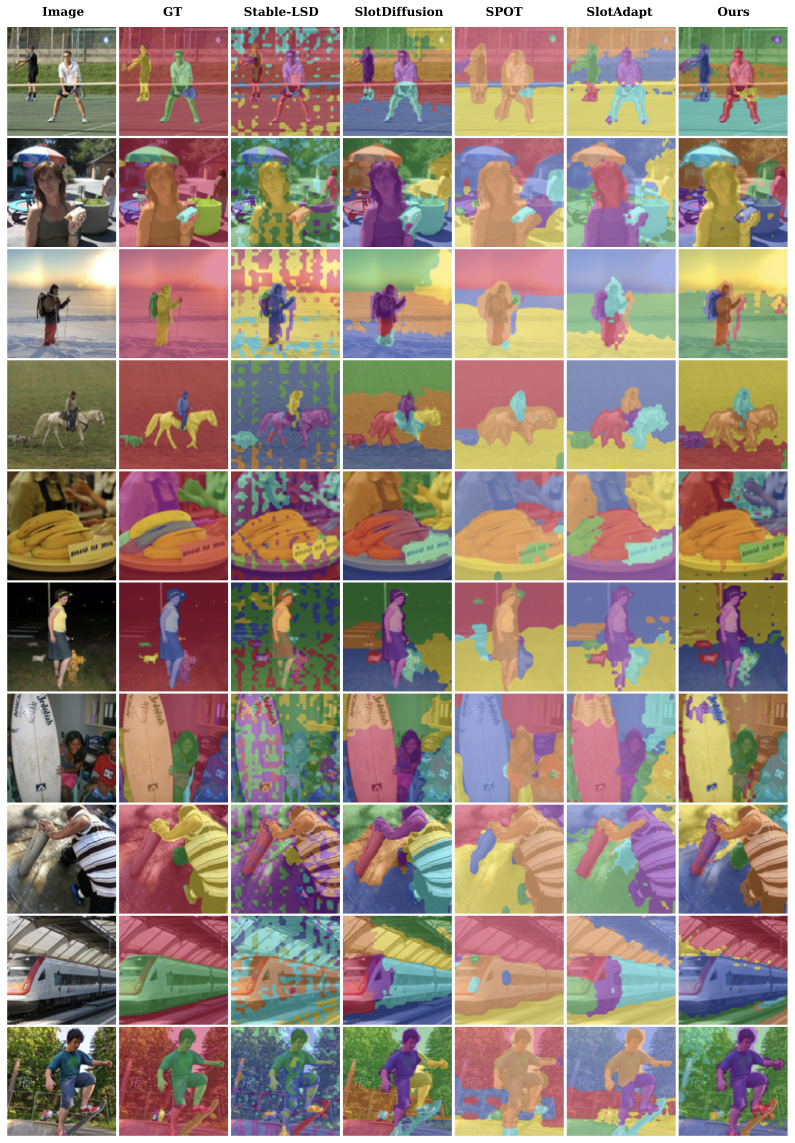

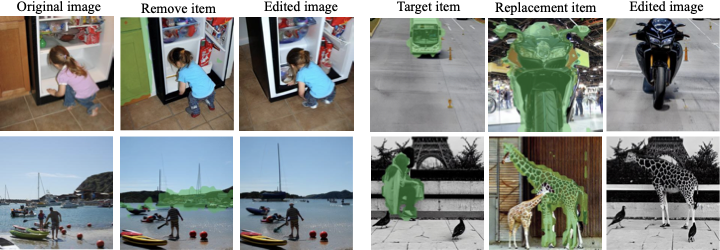

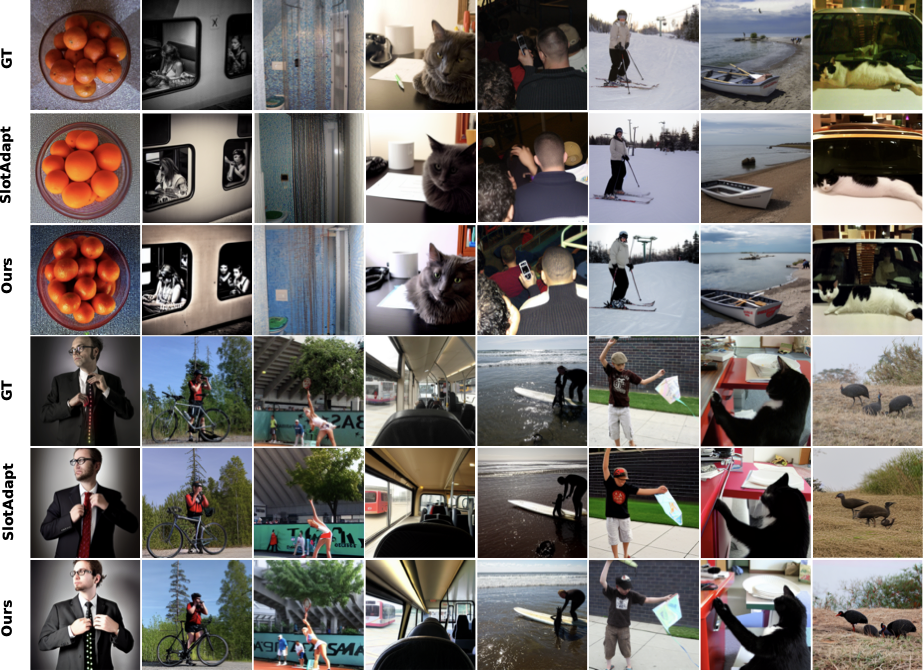

#### Compositional Image generation

To generate high-quality images, a model must not only encode objects

faithfully into slots but also recombine them into novel configurations.

We evaluate this capability through two tasks. First, we assess

*reconstruction*, which measures how accurately the model can recover

the original input image. Second, we evaluate *compositional

generation*, which tests whether slots can be recombined into new,

unseen configurations. Following , these configurations are created by

randomly mixing slots within a batch. Both experiments are conducted on

COCO. In our evaluation, we focus on image fidelity, since our primary

goal is to verify that slot-based compositions yield visually coherent

generations. We report Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) and Kernel

Inception Distance (KID) as quantitative measures of image quality.

<a href="#tab:generation_results" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="tab:generation_results">[tab:generation_results]</a>

shows that `CODA` outperforms both LSD and SlotDiffusion, and further

achieves higher fidelity than SlotAdapt. In the more challenging

compositional generation setting, it achieves the best results on both

FID and KID, highlighting its effectiveness for slot-based composition.

Beyond quantitative metrics,

<a href="#appendix:fig:edited_samples,fig:appendix:editing"

data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="appendix:fig:edited_samples,fig:appendix:editing">[appendix:fig:edited_samples,fig:appendix:editing]</a>

demonstrates `CODA`’s editing capabilities. By manipulating slots, the

model can remove objects by discarding their corresponding slots or

replace them by swapping slots across scenes. These examples highlight

that `CODA` supports fine-grained, controllable edits in addition to

faithful reconstructions. Overall, `CODA` not only preserves

reconstruction quality but also significantly improves the ability of

slot decoders to generalize compositionally, producing high-fidelity

images even in unseen configurations.

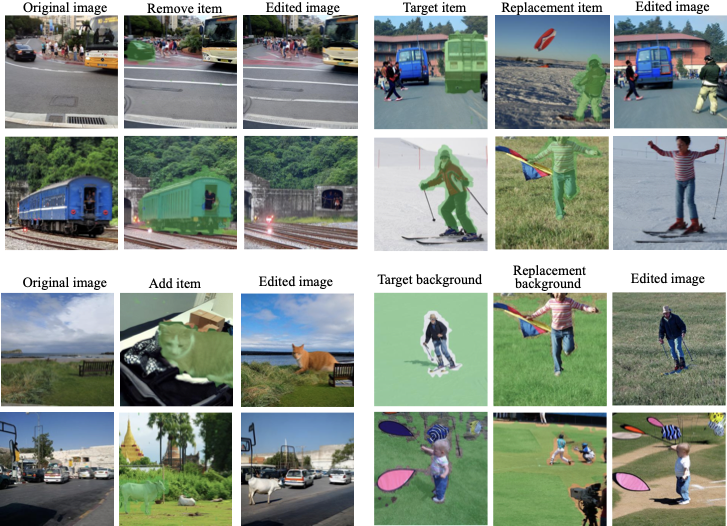

<figure id="appendix:fig:edited_samples" data-latex-placement="!htp">

<img src="/posts/2026/01/2026-01-03-190628-improved_object_centric_diffusion_learning_with_re/edited_samples.png" style="width:100%" /> style="width:95.0%" />

<figcaption>Illustration of compositional editing. <code>CODA</code> can

compose novel scenes from real-world images by removing (left) or

swapping (right) the slots, shown as masked regions in the

images.</figcaption>

</figure>

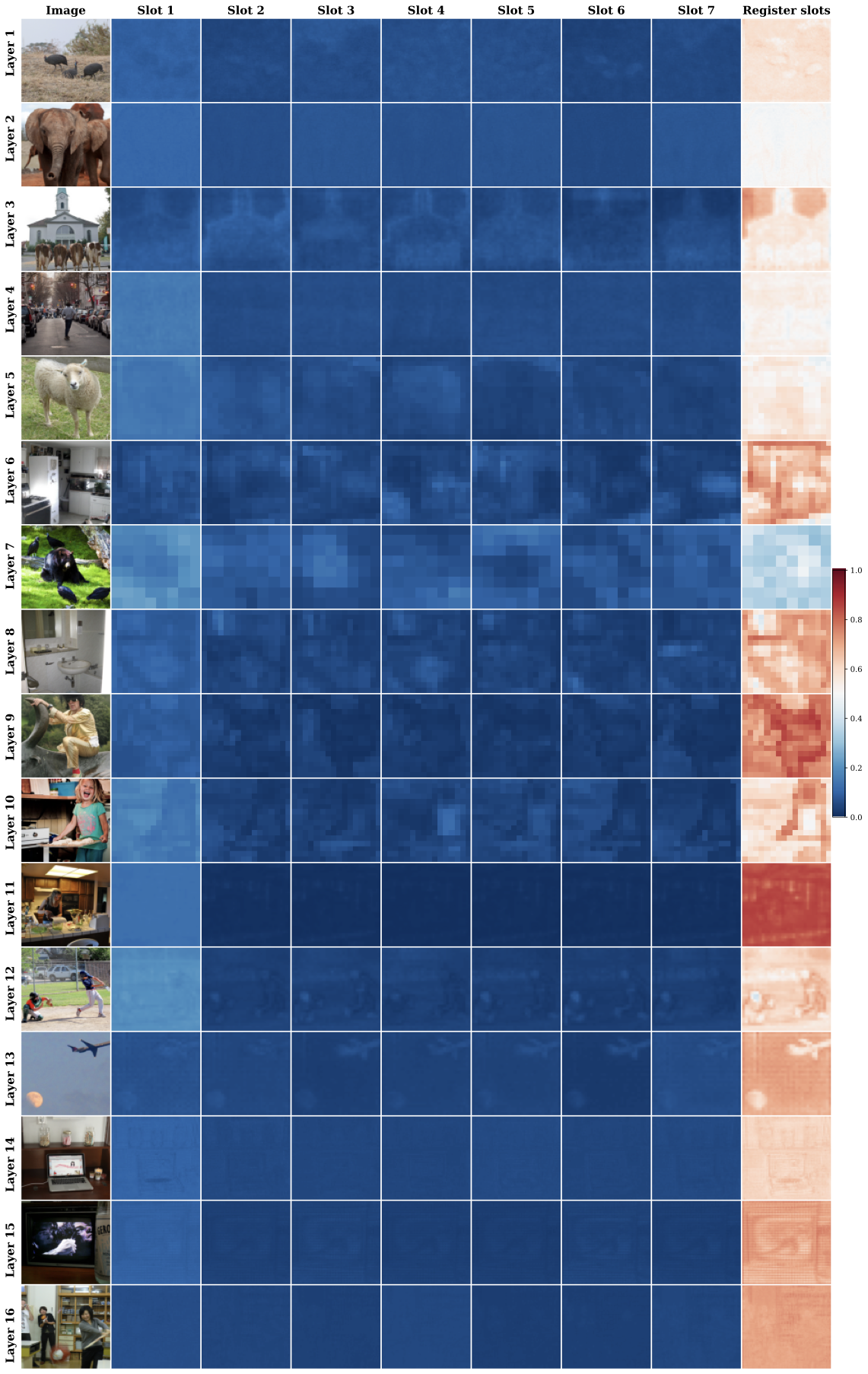

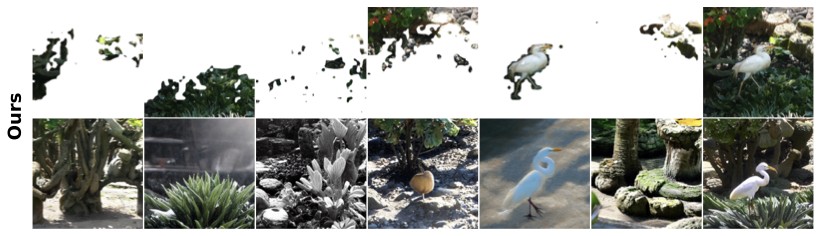

#### Ablation studies

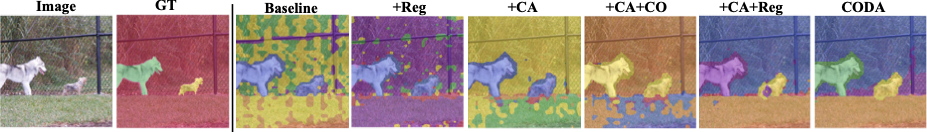

<figure id="fig:ablation_example" data-latex-placement="!htp">

<img src="/posts/2026/01/2026-01-03-190628-improved_object_centric_diffusion_learning_with_re/examples_ablation.png" style="width:100%" /> />

<figcaption>Illustration of the ablation study on VOC. We start from the

pretrained diffusion model as a slot decoder (Baseline), adding register

slots (Reg), finetuning the key, value, and output projections in the

cross-attention layers (CA), adding contrastive alignment

(CO).</figcaption>

</figure>

We conduct ablations to evaluate the contribution of each component in

our framework, with results on the VOC dataset summarized in

<a href="#table:ablation_voc" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="table:ablation_voc">5</a>. The baseline (first row) uses

the frozen SD as a slot decoder. Finetuning the key, value, and output

projections of the cross-attention layers (**CA**) yields moderate

gains. Introducing register slots (**Reg**) provides substantial

improvements, particularly in mBO, by reducing slot entanglement. Adding

the contrastive loss (**CO**) further boosts mIoU; however, applying it

without stopping gradients in the diffusion model ($`\circ`$) degrades

performance. When combined, all components yield the best overall

results, as shown in the final row, with qualitative examples in

<a href="#fig:ablation_example" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="fig:ablation_example">4</a>. Further ablation studies on

the COCO dataset are reported

in <a href="#appendix:table:register_affect"

data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="appendix:table:register_affect">3</a> and additional

results are provided in

<a href="#appendex:additional_results" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="appendex:additional_results">5</a>. Overall, the

ablations demonstrate that each component contributes complementary

benefits in enhancing compositional slot representations.

<figure id="table:ablation_voc" data-latex-placement="!htp">

<div class="minipage">

<img src="/posts/2026/01/2026-01-03-190628-improved_object_centric_diffusion_learning_with_re/segmentation_samples.png" style="width:100%" /> />

</div>

<div class="minipage">

<p><span id="table:ablation_voc"

data-label="table:ablation_voc"></span></p>

</div>

<figcaption>Segmentation masks learned by <code>CODA</code> on

COCO</figcaption>

</figure>

### Conclusions

We introduced `CODA`, a diffusion-based OCL framework that augments slot

sequences with input-independent register slots and a contrastive

alignment objective. Unlike prior approaches that rely solely on

denoising losses or architectural biases, `CODA` explicitly encourages

slot–image alignment, leading to stronger compositional generalization.

Importantly, it requires no architectural modifications or external

supervision, yet achieves strong performance across synthetic and

real-world benchmarks, including COCO and VOC. Despite its current

limitations

(<a href="#appedix:limitation" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="appedix:limitation">6</a>), these results highlight the

value of register slots and contrastive learning as powerful tools for

advancing OCL.

### Reproducibility Statement

<a href="#appedix:implementation_details"

data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="appedix:implementation_details">2.4</a> provides

implementation details of `CODA` along with the hyperparameters used in

our experiments. All datasets used in this work are publicly available

and can be accessed through their official repositories. To ensure full

reproducibility, the source code is available as supplementary material.

### LLM Usage

In this work, large language models (LLMs) were used only to help with

proofreading and enhancing the clarity of the text. All research ideas,

theoretical developments, experiments, and implementation were conducted

entirely by the authors.

### Ethics Statement

This work focuses on improving OCL and compositional image generation

using pretrained diffusion models. While beneficial for controllable

visual understanding, it carries risks: (i) misuse, as compositional

generation could create misleading or harmful content; and (ii) bias

propagation, since pretrained diffusion models may reflect biases in

their training data, which can appear in generated images or

representations. Our method is intended for research on OCL and

representation, not for deployment in production systems without careful

considerations.

# Appendix

### Proofs

#### Proof of <a href="#the:mi" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="the:mi">1</a>

To prove <a href="#the:mi" data-reference-type="ref+label"

data-reference="the:mi">1</a>, we build on theoretical results that

connect data distributions with optimal denoising regression. Let define

the MMSE estimator of $`{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}`$ from a noisy channel

$`{\mathbf{z}}_\gamma`$, which mixes $`{\mathbf{z}}`$ and

$`{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}`$ at noise level $`\gamma`$ as

``` math

\begin{align*}

\hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma)= \mathbb{E}_{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}\sim p({\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}\mid {\mathbf{z}}_\gamma)}[{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}] = \underset{\tilde{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma)}{ \arg \min} \,\, \mathbb{E}_{p({\boldsymbol{\epsilon}})p({\mathbf{z}})} \left[ \| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- \tilde{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma) \|_2^2\right] \,.

\end{align*}showed that the log-likelihood of $`{\mathbf{z}}`$ can be written solely in terms of the MMSE solution:

\begin{align}

\log p({\mathbf{z}}) = -\frac{1}{2} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}\left[\| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- \hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma) \|^2 \right] d\gamma + c \,, \label{eq:nll_unconditional}

\end{align}where $`c = -\frac{D}{2} \log(2\pi e) + \frac{D}{2}\int_{-\infty}^\infty \sigma (\gamma) d\gamma`$ is a constant independent of the data, with $`D`$ denoting the dimensionality of $`{\mathbf{z}}`$.

Analogously, defining the optimal denoiser $`\hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{s}})`$ for the conditional distribution $`p({\mathbf{z}}\mid {\mathbf{s}})`$ yields

\begin{align}

\log p({\mathbf{z}}\mid {\mathbf{s}}) = -\frac{1}{2} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}\left[\| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- \hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{s}}) \|^2 \right] d\gamma + c \,. \label{eq:nll_conditional}

\end{align}Let $`\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \sim q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})`$ denote slots sampled from an auxiliary distribution $`q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}})`$, which may differ from $`p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})`$. Using the KL divergence, we obtain

\begin{align*}

D_{\mathrm{KL}}\left(q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}}) \right) &= \mathbb{E}_{q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}})} \left[ \log \frac{q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}})}{ p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})} \right] \\

&= \mathbb{E}_{q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})} \left[ \log q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}}) - \log p({\mathbf{z}}\mid \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}) - \log p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}) + \log p({\mathbf{z}}) \right] \\

&= -\mathbb{E}_{q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}})} \left[\log p({\mathbf{z}}\mid \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}) \right] + D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}})) + \log p({\mathbf{z}})\,.

\end{align*}This leads to the following decomposition of the marginal distribution:

\begin{align*}

\log p({\mathbf{z}}) & = \mathbb{E}_{q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}})} [\log p({\mathbf{z}}\mid \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}})] + D_{\mathrm{KL}}( q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})) - D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}))

\end{align*}Consequently, the mutual information (MI) between $`{\mathbf{z}}`$ and $`{\mathbf{s}}`$ can be expressed as

\begin{align*}

I({\mathbf{z}}; {\mathbf{s}}) &= \mathbb{E}_{p({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{s}})}\left[ \log p({\mathbf{z}}\mid {\mathbf{s}}) \right] - \mathbb{E}_{p({\mathbf{z}})} \left[ \log p({\mathbf{z}}) \right] \\

&= \mathbb{E}_{p({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{s}})}\left[ \log p({\mathbf{z}}\mid {\mathbf{s}}) \right] - \mathbb{E}_{p({\mathbf{z}})}\mathbb{E}_{q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})} [\log p({\mathbf{z}}\mid \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}})] \\

& \quad - \mathbb{E}_{p({\mathbf{z}})}[ D_{\mathrm{KL}}( q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})) - D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}))]

\end{align*}From [eq:nll_conditional], it follows that

\begin{align}

-I({\mathbf{z}}; {\mathbf{s}}) &= \frac{1}{2} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathbb{E}_{({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{s}}), {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}} \left[\| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- \hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{s}}) \|^2 \right] d\gamma - \frac{1}{2} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \mathbb{E}_{({\mathbf{z}}, \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}), {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}} \left[\| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- \hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}) \|^2 \right] d\gamma \nonumber\\

& \quad + \mathbb{E}_{{\mathbf{z}}}\left[ D_{\mathrm{KL}}( q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})) - D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}))\right] \nonumber\\

&= \frac{1}{2} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \Big(\mathbb{E}_{({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{s}}), {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}} \left[\| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- \hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, {\mathbf{s}}) \|^2 \right] - \mathbb{E}_{({\mathbf{z}}, \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}), {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}} \left[\| {\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}- \hat{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}}({\mathbf{z}}_\gamma, \gamma, \tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}) \|^2 \right] \Big)d\gamma \nonumber \\

& \quad + \mathbb{E}_{{\mathbf{z}}}\left[ D_{\mathrm{KL}}( q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})) - D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}))\right] \,, \label{eq:main_theorem}

\end{align}which completes the proof. $`\square`$

Proof of <a href="#coro:one" data-reference-type=“ref+label”

data-reference=“coro:one”>1

Under the assumption that $`q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}}) = p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}})`$, it yields

\begin{align}

\mathbb{E}_{{\mathbf{z}}} \left[ D_{\mathrm{KL}}(q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}))\right] &= \mathbb{E}_{{\mathbf{z}}} \left[ D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}))\right] \nonumber \\

&= 0 \, . \label{eq:second_kl}

\end{align}Similarly, the expected KL-divergence term in [eq:main_theorem] simplifies as follows:

\begin{align}

\mathbb{E}_{{\mathbf{z}}}\left[ D_{\mathrm{KL}}( q(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}\mid {\mathbf{z}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})) \right] &= \mathbb{E}_{{\mathbf{z}}}\left[ D_{\mathrm{KL}}( p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}) || p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})) \right] \nonumber \\

&= \mathbb{E}_{p({\mathbf{z}})p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}})} \left[ \log \frac{p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}})}{p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}} \mid {\mathbf{z}})} \right] \nonumber \\

&= \mathbb{E}_{p({\mathbf{z}})p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}})} \left[ \log \frac{p({\mathbf{z}}) p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}})}{p(\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}, {\mathbf{z}})} \right] \nonumber \\

&= D_{\mathrm{KL}}(p({\mathbf{z}})p({\mathbf{s}}) || p({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{s}})) \,. \label{eq:first_kl}

\end{align}Substituting [eq:first_kl,eq:second_kl] into [eq:main_theorem] completes the proof. $`\square`$

Remark 1. [eq:first_kl] shows that the additional expected KL-divergence reduces to the reverse KL divergence between the product of marginals $`p({\mathbf{z}})p({\mathbf{s}})`$ and the joint distribution $`p({\mathbf{z}}, {\mathbf{s}})`$. This term complements the standard mutual information $`I({\mathbf{z}};{\mathbf{s}})`$, and together they form the Jeffreys divergence. Intuitively, while MI penalizes approximating the joint by the independent model, the reverse KL penalizes the opposite mismatch, thereby reinforcing the statistical dependence between $`{\mathbf{z}}`$ and $`{\mathbf{s}}`$.

Experimental setup

This section outlines the experimental setup of our study. We detail the datasets, baseline methods, evaluation metrics, and implementation choices used in all experiments.

Datasets

MOVi-C/E . These two variants of the MOVi benchmark are generated with the Kubric simulator. Following prior works , we evaluate on the 6,000-image validation set, since the official test sets are designed for out-of-distribution (OOD) evaluation. MOVi-C consists of complex objects and natural backgrounds, while MOVi-E includes scenes with a large numbers of objects (up to 23) per image.

VOC . We use the PASCAL VOC 2012 “trainaug” split, which includes 10,582 images: 1,464 images from the official train set and 9,118 images from the SDB dataset . This configuration is consistent with prior works . Training images are augmented with center cropping and then random horizontal flipping applied with a probability of 0.5. For evaluation, we use the official segmentation validation set of 1,449 images, where unlabeled pixels are excluded from scoring.

COCO . For experiments, we use the COCO 2017 dataset, consisting of 118,287 training images and 5,000 validation images. Training images are augmented with center cropping followed by random horizontal flipping with probability 0.5. For evaluation, we follow standard practice by excluding crowd instance annotations and ignoring pixels corresponding to overlapping objects.

Baselines

We compare CODA against state-of-the-art fully unsupervised OCL

models. The baselines include SA , DINOSAUR , SLATE , SLATE$`^+`$ (a

variant using a pretrained VQGAN instead of a dVAE), SPOT2 ,

Stable-LSD3 SlotDiffusion4 , and SlotAdapt . For DINOSAUR, we

evaluate both MLP and autoregressive Transformer decoders. For SPOT, we

report results with and without test-time permutation ensembling (SPOT

w/ ENS, SPOT w/o ENS). We use the pretrained checkpoints released by the

corresponding authors for SPOT and SlotDiffusion.

Metrics

Foreground Adjusted Rand Index (FG-ARI). The Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) measures the similarity between two partitions by counting pairs of pixels that are consistently grouped together (or apart) in both segmentations. The score is adjusted for chance, with values ranging from 0 (random grouping) to 1 (perfect agreement). The Foreground ARI (FG-ARI) is a variant that evaluates agreement only on foreground pixels, excluding background regions.

Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU). The Intersection over Union (IoU) between a predicted segmentation mask and its ground-truth counterpart is defined as the ratio of their intersection to their union. The mean IoU (mIoU) is obtained by averaging these IoU values across all objects and images in the dataset. This metric measures how well the predicted segmentation masks overlap with the ground-truth masks, aggregated over all instances.

Mean Best Overlap (mBO). The Best Overlap (BO) score for a predicted segmentation mask is defined as the maximum IoU between that predicted mask and any ground-truth object mask in the image. The mean BO (mBO) is then computed by averaging these BO scores across all predicted masks in the dataset. Unlike mIoU, which evaluates alignment with ground-truth objects directly, mBO emphasizes how well each predicted mask corresponds to its best-matching object, making it less sensitive to under- or over-segmentation.

Implementation details

The hyperparameters are summarized in

1. We initialize the U-Net denoiser

and VAE components from Stable Diffusion v1.55 . During training,

only the key, value, and output projections in the cross-attention

layers are finetuned, while all other components remain frozen. For slot

extraction, we employ DINOv26 with a ViT-B backbone and a patch size

of 14, producing feature maps of size $`32\times32`$. The input

resolution is set to $`512\times512`$ for the diffusion model and

$`448\times448`$ for SA. As a form of data augmentation, we apply random

horizontal flipping (Rand.HFlip) during training with a probability of

0.5. The negative slots are constructed by replacing 50% of the original

slots with a subset of slots sampled from other images within the batch.

CODA is trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of

$`2 \times 10^{-5}`$, a weight decay of $`0.01`$, and a constant

learning rate schedule with a warm-up of 2500 steps. To improve

efficiency and stability, we use 16-bit mixed precision and gradient

norm clipping at 1. All models are trained on 4 NVIDIA A100 GPUs with a

local batch size of 32. We train for 500k steps on the COCO dataset and

250k steps on all other datasets. Training takes approximately 5.5 days

for COCO and 2.7 days for the remaining datasets. For evaluation, the

results are averaged over five random seeds. To ensure a fair

comparision, for all FID and KID evaluations, we downsample CODA’s

$`512\times512`$ outputs to $`256\times256`$, matching the resolution

used in prior works.

Attention masks for evaluation. We evaluate object segmentation using the attention masks produced by SA. At each slot iteration, attention scores are first computed using the standard $`\mathtt{softmax}`$ along the slot axis and then normalized via a weighted mean:

\begin{align*}

{\mathbf{m}}^{(t)} = \underset{N}{\mathtt{softmax}} \left( \frac{q({\mathbf{s}}^{(t)}) k({\mathbf{f}})^\top}{\sqrt{D}} \right) \Longrightarrow \quad {\mathbf{m}}^{(t)}_{m,n} = \frac{{\mathbf{m}}^{(t)}_{m,n}}{\sum_{l=1}^M {\mathbf{m}}^{(t)}_{l,n}} \,,

\end{align*}where $`D`$ denotes the dimension of $`k({\mathbf{f}})`$. The soft attention masks from the final iteration are converted to hard masks with $`\mathtt{arg max}`$ and used as the predicted segmentation masks for evaluation. This procedure ensures that each pixel is assigned to the slot receiving the highest attention weight.

| Hyperparameter | MOVi-C | MOVi-E | VOC | COCO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | ||||

| Training steps | 250k | 250k | 250k | 500k |

| Learning rate | $`2\times 10^{-5}`$ | $`2\times 10^{-5}`$ | $`2\times 10^{-5}`$ | $`2\times 10^{-5}`$ |

| Batch size | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Learning rate warm up | 2500 | 2500 | 2500 | 2500 |

| Optimizer | AdamW | AdamW | AdamW | AdamW |

| ViT architecture | DINOv2 ViT-B | DINOv2 ViT-B | DINOv2 ViT-B | DINOv2 ViT-B |

| Diffusion | SD v.1.5 | SD v.1.5 | SD v.1.5 | SD v.1.5 |

| Gradient norm clipping | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Weighting $`\lambda_{\mathrm{cl}}`$ | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Image specification | ||||

| Image size | 512 | 512 | 512 | 512 |

| Augmentation | Rand.HFlip | Rand.HFlip | Rand.HFlip | Rand.HFlip |

| Crop | Full | Full | Central | Central |

| Slot attention | ||||

| Input resolution | $`32 \times 32`$ | $`32 \times 32`$ | $`32 \times 32`$ | $`32 \times 32`$ |

| Number of slots | 11 | 24 | 6 | 7 |

| Number of iterations | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Slot size | 768 | 768 | 768 | 768 |

Hyperparameters used for CODA on MOVi-C, MOVi-E, VOC, and COCO

datasets

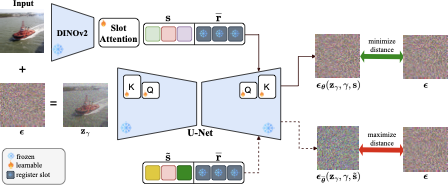

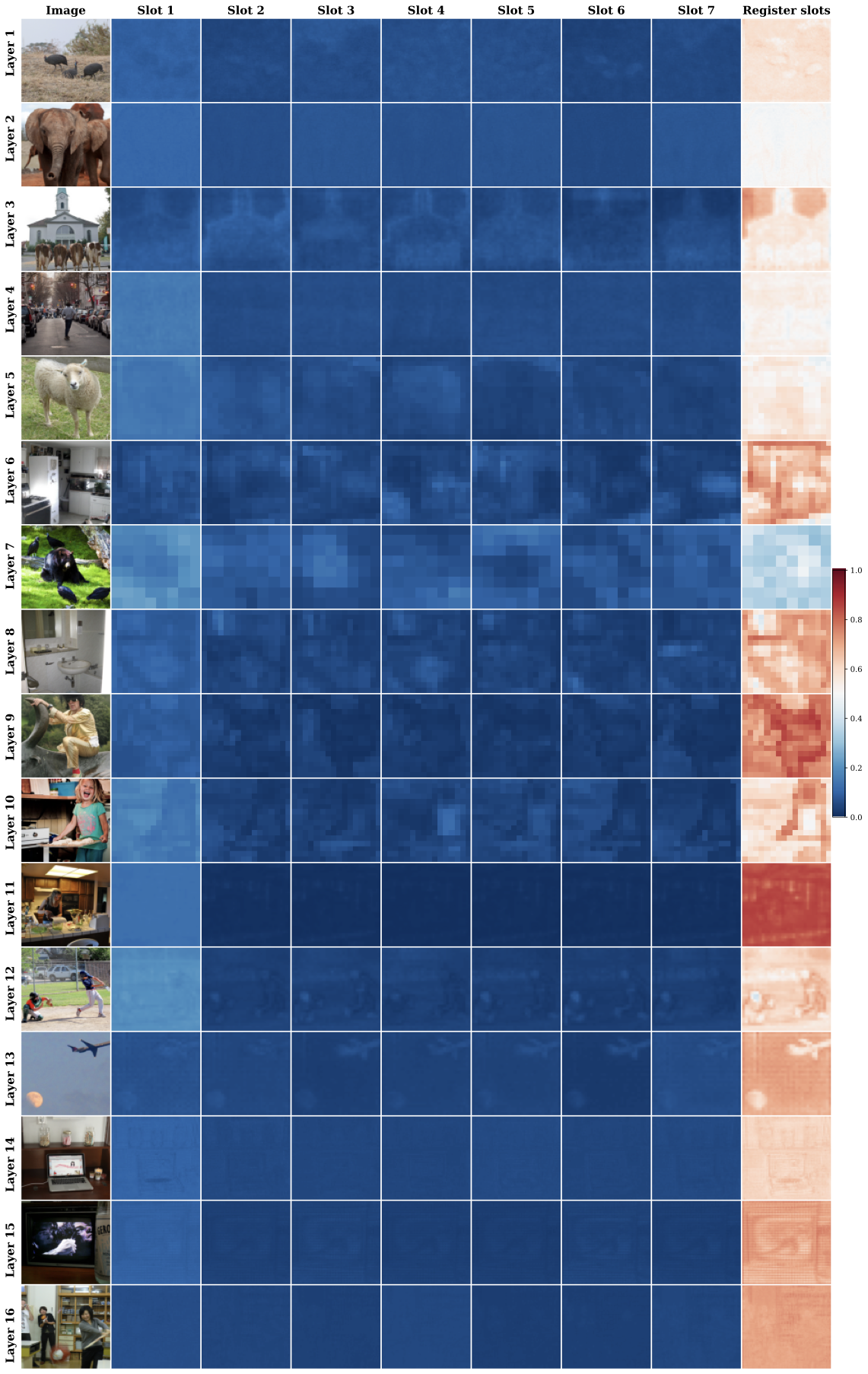

Visualization of attention scores

We visualize the attention scores in

6, showing the

average attention mass assigned to semantic slots versus register slots.

CODA is trained on the COCO dataset, and illustrative images are

randomly sampled. Since the cross-attention layers in SD are multi-head,

we average the attention maps across both heads and noise levels.

Interestingly, although register slots are semantically empty, they consistently absorb a substantial portion of the attention mass. This arises from the $`\mathtt{softmax}`$ normalization, which forces attention scores to sum to one across all slots. When a query does not strongly correspond to any semantic slot, the model must still allocate its attention; register slots act as neutral sinks that capture these residual values. This mechanism helps preserve clean associations between semantic slots and object concepts.

style="width:97.0%" />

style="width:97.0%" />

CODA. Each image in row

Layer i and

column Slot j

visualizes the total attention mass assigned to slot j at layer i. The last column reports the total

attention mass absorbed by the register slots. CODA

heavily attends to the register slots across all

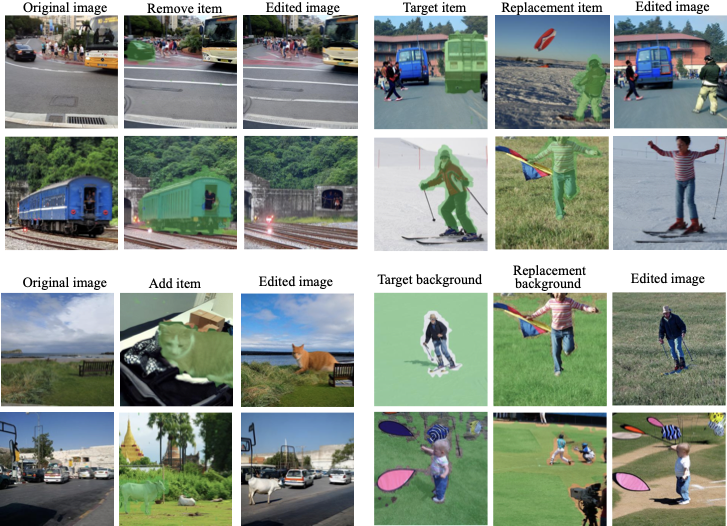

layers.Compositional image generation from individual slots

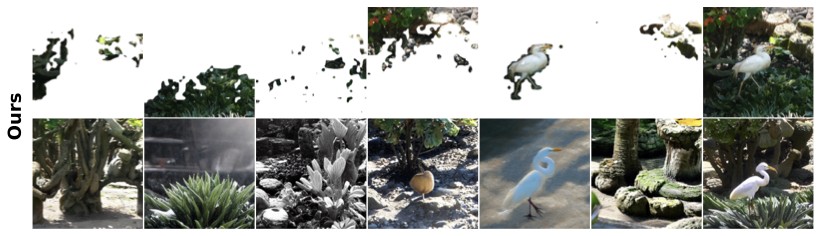

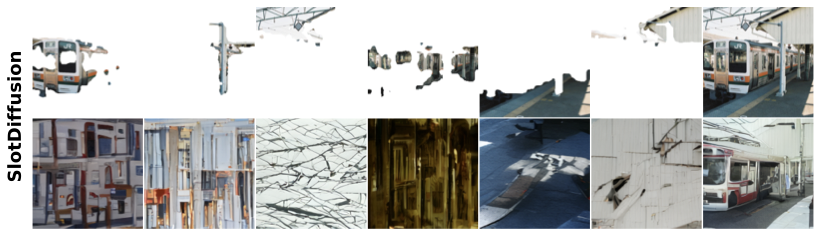

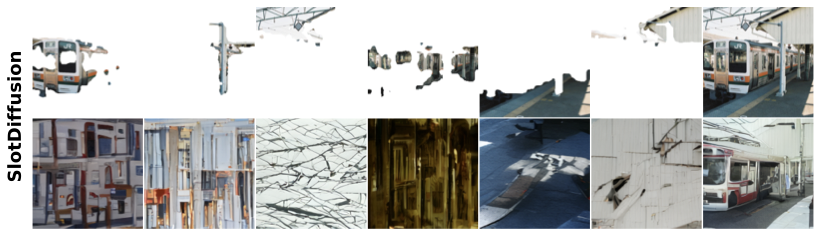

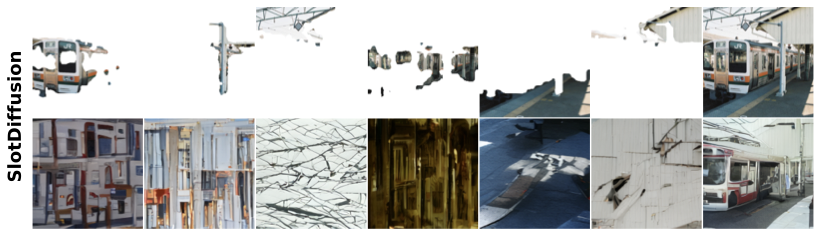

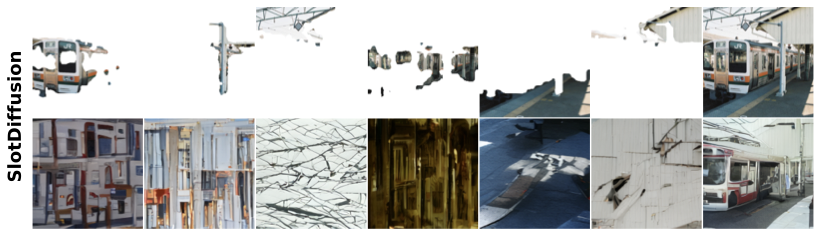

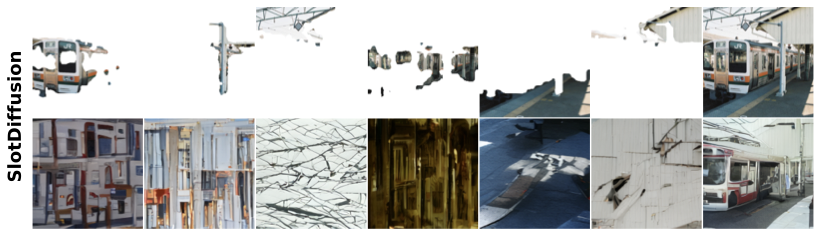

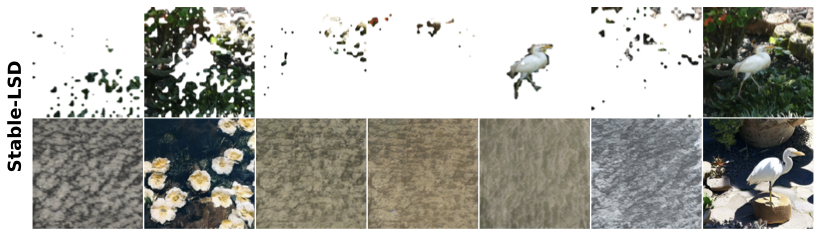

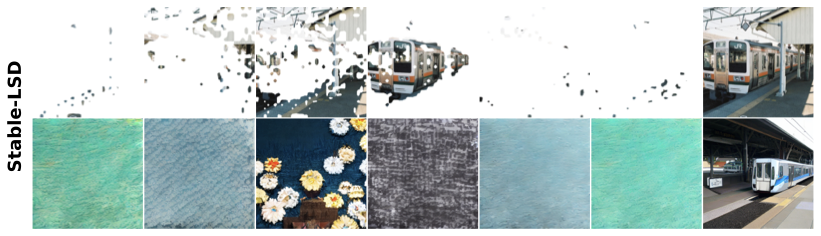

We evaluate the ability of diffusion-based OCL methods to generate

images from individual slots. As shown in

7, each input image is

decomposed into six slots, with each slot intended to represent a

distinct concept. We then condition the decoder on individual slots to

generate single-concept images. The last column shows reconstructions

using all slots combined. While all methods can reconstruct the original

images when conditioned on the full slot set, most fail to produce

faithful generations from individual slots. Specifically, Stable-LSD

produces mostly texture-like patterns that poorly match the intended

concepts, while SlotDiffusion , despite being trained end-to-end, also

struggles to generate coherent objects. In Stable-LSD, slots are jointly

trained to reconstruct the full scene, so object information can be

distributed across multiple slots rather than concentrated in any single

one. Consequently, removing all but one slot at test time puts the model

in an out-of-distribution regime, and single-slot generations do not

yield coherent objects even though the full slot set reconstructs the

image well. This reflects slot entanglement where individual slots mix

features from multiple objects. SlotAdapt partially alleviates this

issue through an average register token, but since their embedding is

injected directly into the cross-attention layers and tied to

input-specific features, it limits flexibility in reusing slots across

arbitrary compositions. In contrast, the input-independent register

slots introduced in CODA act as residual sinks and do not encode

input-specific features, enabling more faithful single-slot generations

and greater compositional flexibility.

To quantify these results, we report FID and KID scores by comparing

single-slot generations against the real images in the training set. For

each validation image, we extract six slots and generate six

corresponding single-slot images, ensuring a fair comparison across

methods. Results on the VOC dataset are reported in

4, where CODA

achieves the best scores, confirming its ability to generate coherent

and semantically faithful images from individual slots.

Although register slots substantially reduce background entanglement, they do not enforce a hard separation between foreground and background. The attention mechanism in SA still remains soft, and our objectives do not explicitly prevent semantic slots from attending to background regions. As a result, semantic slots may still absorb contextual pixels, especially near object boundaries or in textured areas that are useful for reconstruction, when the number of slots exceeds the number of objects. As a result, small “meaningless” background fragments may still be assigned to semantic slots, as seen in 7. Empirically, however, we find that register slots substantially decrease background leakage compared to baselines without registers.

style="width:90.0%" />

style="width:90.0%" />  style="width:90.0%" />

style="width:90.0%" />  style="width:90.0%" />

style="width:90.0%" />  style="width:90.0%" />

style="width:90.0%" />

CODA, register slots can be regarded as part of the U-Net

architecture as they are independent from the input. Compared to

baselines, our method generates faithful images from individual

slots.Additional results

In this section, we present supplementary quantitative and qualitative

results that provide further insights into the performance of CODA.

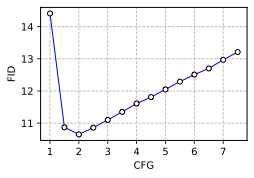

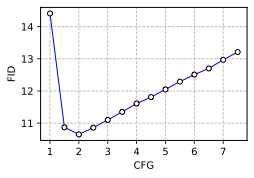

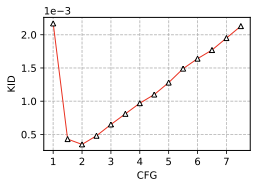

Classifier-free guidance

To enhance image generation quality, we employ classifier-free guidance

(CFG) , which interpolates between conditional and unconditional

diffusion predictions. A guidance scale of $`\mathrm{CFG}=1`$

corresponds to standard conditional generation. We conduct an ablation

study on different CFG values to assess their impact on generation

quality. As shown in

8, both FID and KID scores

improve with moderate guidance, with CODA achieving the best

performance at $`\mathrm{CFG}=2.0`$. This indicates that a balanced

level of guidance enhances fidelity without over-amplifying artifacts.

style="width:35.0%" />

style="width:35.0%" />  style="width:35.0%" />

style="width:35.0%" />

Learnable register slots

Several works have explored trainable tokens as auxiliary inputs to

transformers. For example, the [CLS] token is commonly introduced for

classification in ViT and BERT , while CLIP employs an [EOS] token.

These tokens serve as learnable registers that allow the model to store

and retrieve intermediate information during inference. demonstrated

that appending such tokens can boost performance by increasing token

interactions, thereby promoting deeper computation. Similarly, utilized

register tokens during pretraining to mitigate the emergence of

high-norm artifacts. Motivated by these findings, we experiment with

replacing our frozen CLIP-derived register slots with learnable ones.

These slots are appended to the slot sequence but remain context-free

placeholders.

Results on VOC with varying numbers of learnable register slots are

shown in 2. The model

without register slots ($`R=0`$) performs the worst across all metrics

(FG-ARI, mBO$`^i`$, mBO$`^c`$, mIoU$`^i`$, and mIoU$`^c`$).

Interestingly, introducing just a single register slot leads to a

significant performance boost. Further increasing the number of tokens

to $`R=77`$, matching the configuration used in CODA, yields only

marginal improvements. Although more register slots could slightly

increase computational cost, this is negligible as the number of

register slots is relatively small. For instance, using 77 register

slots increases GPU time by only 0.02% compared to the baseline without

using any register slot. Interestingly, CODA achieves the best

performance when using frozen register slots. These findings emphasize

the effectiveness of register slots in improving the model performance.

| $`R`$ | FG-ARI$`\uparrow`$ | mBO$`^i`$$`\uparrow`$ | mBO$`^c`$$`\uparrow`$ | mIoU$`^i`$$`\uparrow`$ | mIoU$`^c`$$`\uparrow`$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 15.44 | 47.03 | 52.63 | 49.75 | 55.63 |

| 1 | 30.39 | 54.47 | 59.96 | 50.21 | 55.34 |

| 4 | 29.89 | 54.91 | 60.15 | 50.65 | 55.65 |

| 64 | 30.40 | 54.62 | 59.93 | 50.47 | 55.45 |

| 77 | 30.21 | 55.26 | 60.89 | 50.86 | 56.07 |

CODA |

32.23 | 55.38 | 61.32 | 50.77 | 56.30 |

Ablation study on varying the number of register slots on the VOC dataset

Additional ablation on COCO

We further examine the contribution of frozen register slots on the COCO dataset, using pretrained SD as the slot decoder baseline. Different settings are evaluated: (i) adding register slots (+Reg), (ii) adding register slots combined with finetuning the key, value, and output projections in cross-attention layers (+CA), and adding the contrastive loss (+CO). As shown in 3, register slots consistently improve performance in both cases, demonstrating their robustness and effectiveness when integrated into the slot sequence.

| Method | FG-ARI$`\uparrow`$ | mBO$`^i`$$`\uparrow`$ | mBO$`^c`$$`\uparrow`$ | mIoU$`^i`$$`\uparrow`$ | mIoU$`^c`$$`\uparrow`$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 20.99 | 29.77 | 37.21 | 32.16 | 41.25 |

| Baseline + Reg | 23.64 | 31.14 | 39.07 | 32.64 | 41.91 |

| Baseline + CA | 36.99 | 33.82 | 38.08 | 35.04 | 41.24 |

| Baseline + CA + Reg | 45.95 | 35.80 | 40.32 | 35.76 | 41.75 |

| Baseline + CO | 25.24 | 30.14 | 38.77 | 32.83 | 42.99 |

| Baseline + CO + CA | 35.84 | 34.36 | 38.67 | 36.28 | 42.85 |

Baseline + CA + Reg + CO (CODA) |

47.54 | 36.61 | 41.43 | 36.41 | 42.64 |

Ablation study on the COCO dataset

We further analyze the effect of the contrastive loss on image generation. Results are reported in 4. Without the contrastive loss, Reg+CA achieves slightly better FID/KID under compositional generation than the full model Reg+CA+CO. This aligns with the role of CO, which is primarily intended to strengthen slot–image alignment and object-centric representations rather than to maximize image fidelity, and can therefore marginally degrade FID/KID. Overall, CO should be viewed as an optional component that further improve object discovery at a small cost in visual quality.

| Metric | Reconstruction | Compositional generation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-3 | Reg + CA | Reg + CA + CO | Reg + CA | Reg + CA + CO | |

| KID×103 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 27.95 | 30.44 | |

| FID | 10.65 | 10.65 | 29.34 | 31.03 | |

Effect of the contrastive loss weighting

We conduct an ablation study to analyze the impact of the weighting coefficient $`\lambda_\mathrm{cl}`$ in the contrastive loss term of our objective function in [eq:total_loss]. Results on the COCO dataset are shown in 5. The study reveals that moderate values of $`\lambda_\mathrm{cl}`$ achieve the best trade-off between the denoising and contrastive objectives, yielding the strongest overall performance. In practice, very small weights underuse the contrastive signal, while excessively large weights destabilize training and harm reconstruction quality. Although the contrastive loss shares a similar form with the diffusion loss, in practice, we find that it needs to be weighted by a relatively small factor $`\lambda_\mathrm{cl}`$ to obtain good results. Empirically, increasing $`\lambda_\mathrm{cl}`$ consistently degrades visual quality. We hypothesize that this happens because the contrastive term operates on slot-level features and, when heavily weighted, over-emphasizes alignment at the expense of the diffusion prior, leading to overspecialized and less realistic samples. In contrast, a small $`\lambda_\mathrm{cl}`$ acts as a weak regularizer that improves alignment while keeping the diffusion objective dominant.

| $`\lambda_{\mathrm{cl}}`$ | FG-ARI$`\uparrow`$ | mBO$`^i`$$`\uparrow`$ | mBO$`^c`$$`\uparrow`$ | mIoU$`^i`$$`\uparrow`$ | mIoU$`^c`$$`\uparrow`$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 45.95 | 35.80 | 40.32 | 35.76 | 41.75 |

| 0.001 | 46.07 | 35.99 | 40.50 | 36.18 | 42.18 |

| 0.002 | 45.93 | 35.88 | 40.79 | 35.74 | 42.02 |

| 0.003 | 47.54 | 36.61 | 41.43 | 36.41 | 42.60 |

| 0.004 | 46.87 | 36.38 | 41.13 | 36.26 | 42.41 |

| 0.005 | 44.98 | 35.80 | 40.86 | 35.44 | 41.75 |

Ablation study on varying the weighting terms in contrastive loss on the COCO dataset

Combination ratios for negative slots

This section explores different combination ratios for constructing

negative slots $`\tilde{{\mathbf{s}}}`$. As outlined

in 4.3, given two slot

sequences $`{\mathbf{s}}`$ and $`{\mathbf{s}}'`$ from two distinct

images $`{\mathbf{x}}`$ and $`{\mathbf{x}}'`$, we randomly replace a

fraction $`r \in (0,1]`$ of slots from $`{\mathbf{s}}`$ with those from

$`{\mathbf{s}}'`$. When $`r=1`$, the entire set of slots

$`{\mathbf{s}}`$ is replaced by $`{\mathbf{s}}'`$, while values

$`0

| $`r`$ | FG-ARI$`\uparrow`$ | mBO$`^i`$$`\uparrow`$ | mBO$`^c`$$`\uparrow`$ | mIoU$`^i`$$`\uparrow`$ | mIoU$`^c`$$`\uparrow`$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 32.34 | 54.58 | 60.52 | 50.44 | 55.97 |

| 0.50 | 32.23 | 55.38 | 61.32 | 50.77 | 56.30 |

| 0.75 | 33.34 | 55.06 | 60.98 | 50.12 | 55.61 |

| 1.00 | 32.67 | 54.60 | 59.84 | 49.73 | 54.64 |

Ablation study on varying the portion of negative slots on the VOC dataset

Comparison with weakly-supervised baselines

We compare CODA to GLASS , a weakly supervised approach that uses a

guidance module to produce semantic masks as pseudo ground truth. In

particular, BLIP-2 is used for caption generation to create guidance

signals. While this supervision helps GLASS mitigate over-segmentation,

it also limits its applicability in fully unsupervised settings. In

contrast, CODA does not rely on any external supervision and can

distinguish between multiple instances of the same class, enabling more

fine-grained object separation and richer compositional editing.

[appendix:tab:glass] reports the

results. We additionally consider GLASS$`^\dagger`$, a variant of GLASS

that uses ground-truth class labels associated with the input image.

While GLASS achieves stronger performance on semantic segmentation

masks, it underperforms CODA on object discovery, as reflected by

lower FG-ARI scores. This suggests that CODA is better at

disentangling distinct object instances at a conceptual level.

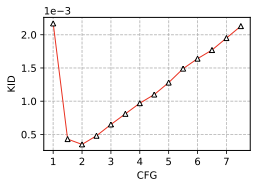

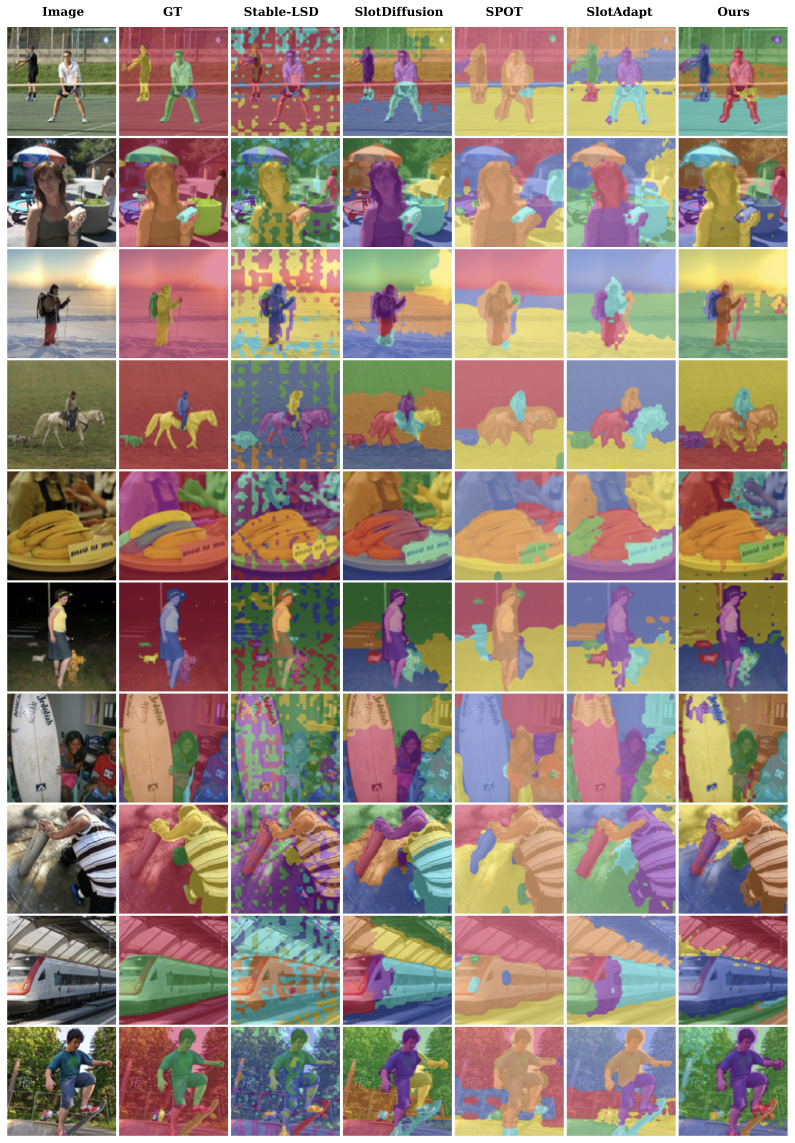

Qualitative comparison

To complement the quantitative results in the main paper, we present

additional qualitative examples that illustrate the effectiveness of

CODA. These examples provide a more complete picture of the model’s

performance and highlight its advantages over previous approaches.

Object segmentation. We visualize segmentation results in

9. CODA

consistently discovers objects and identifies semantically meaningful

regions in a fully unsupervised manner. Compared to diffusion-based OCL

baselines such as Stable-LSD and SlotDiffusion, CODA produces cleaner

masks with fewer fragmented segments, leading to more coherent object

boundaries.

/>

/>

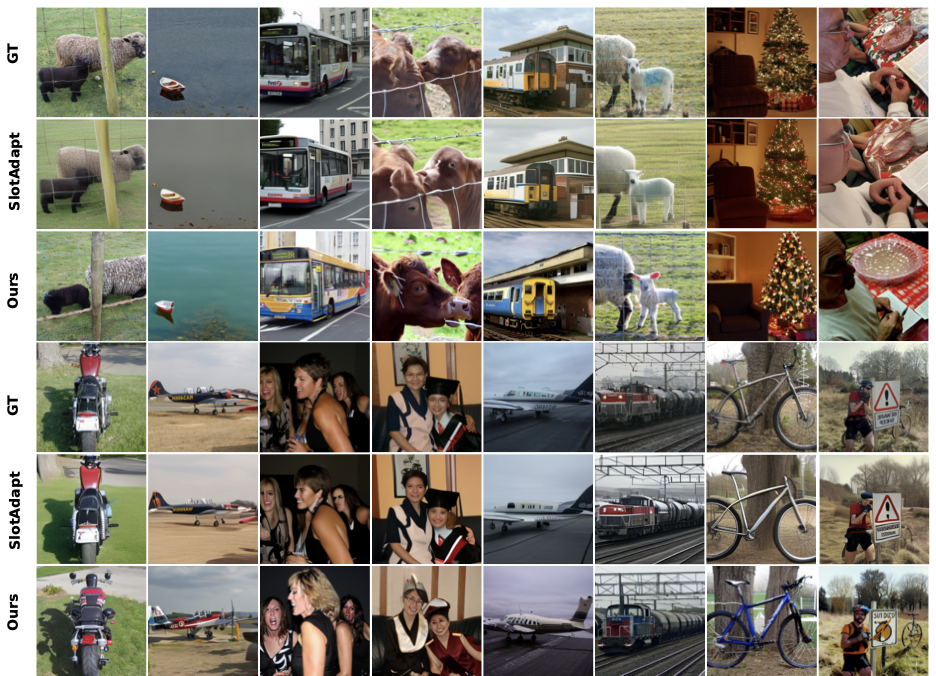

Reconstruction. [fig:appendix:visual_reconstruction:real_world,fig:appendix:visual_reconstruction:synthetic]

show reconstructed images generated by CODA. The results demonstrate

that CODA produces high-quality reconstructions when conditioned on

the learned slots. Importantly, the generated images preserve semantic

consistency while exhibiting visual diversity, indicating that the slots

capture abstract and meaningful representations of the objects in the

scene.

Compositional generation.

12 showcases COCO image edits

based on CODA’s learned slots, including object removal, replacement,

addition, and background modification. We find that the editing

operations are highly successful, introducing only minor adjustments

while consistently preserving high image quality.

CODA.CODA. />

/>

CODA composes novel scenes from real-world images by

removing (top left), swapping (top right), and adding (bottom left)

slots, as well as changing the background (bottom right). The masked

objects indicate the slots that are added, removed, or replaced relative

to the original image.Limitations and future work

While CODA achieves strong performance across synthetic and real-world

benchmarks, it has several limitations that open avenues for future

research. (i) CODA relies on DINOv2 features and SD backbones, which

may inherit dataset-specific biases and limit generalization to domains

with very different visual statistics. (ii) While our contrastive loss

improves slot–image alignment, full disentanglement in cluttered or

ambiguous scenes remains an open challenge. (iii) Inherited from SA,

CODA still requires the number of slots to be specified in advance.

This restricts flexibility in scenes with a variable or unknown number

of objects, and can lead to either unused slots or missed objects . In

our implementation, CODA uses a fixed number of semantic slots plus a

small number of register slots. Note that the register slots do not

reduce semantic capacity but also cannot resolve the fundamental

bottleneck when the true number of objects exceeds the available

semantic slots, in which case objects may still be merged into the same

slot despite reduced background entanglement. This is because the

contrastive alignment is defined only for semantic slots, which

encourages them to explain object-level content, while register slots

are discouraged from encoding object-like structure.