The Illusion of Insight in Reasoning Models

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: The Illusion of Insight in Reasoning Models- ArXiv ID: 2601.00514

- Date: 2026-01-02

- Authors: Liv G. d Aliberti, Manoel Horta Ribeiro

📝 Abstract

Do reasoning models have "Aha!" moments? Prior work suggests that models like DeepSeek-R1-Zero undergo sudden mid-trace realizations that lead to accurate outputs, implying an intrinsic capacity for self-correction. Yet, it remains unclear whether such intrinsic shifts in reasoning strategy actually improve performance. Here, we study mid-reasoning shifts and instrument training runs to detect them. Our analysis spans 1M+ reasoning traces, hundreds of training checkpoints, three reasoning domains, and multiple decoding temperatures and model architectures. We find that reasoning shifts are rare, do not become more frequent with training, and seldom improve accuracy, indicating that they do not correspond to prior perceptions of model insight. However, their effect varies with model uncertainty. Building on this finding, we show that artificially triggering extrinsic shifts under high entropy reliably improves accuracy. Our results show that mid-reasoning shifts are symptoms of unstable inference behavior rather than an intrinsic mechanism for self-correction.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **Definition & Framework:** We define "Aha!" moments as measurable mid-trace shifts and introduce an experimental framework to study intrinsic self-correction during RL fine-tuning. 2. **Empirical Characterization at Scale:** Across over 1 million traces spanning domains, temperatures, training stages, and model families, we show that reasoning shifts are rare and typically coincide with lower accuracy, challenging the view that they reflect genuine insight. 3. **Intervention:** We develop an intervention method to induce reconsideration when models are uncertain, yielding measurable accuracy gains.📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

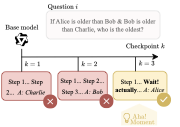

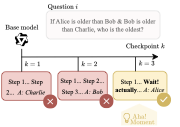

Anecdotal evidence suggests that language models fine-tuned with reinforcement learning exhibit “Aha!” moments—episodes of apparent insight reminiscent of human problem-solving. For example, highlight mid-trace cues such as “Wait… let’s re-evaluate step-by-step,” which sometimes accompany correct answers. Yet, the nature, frequency, and impact of these events (Fig. 1) remain unclear . 1

The existence of “Aha!” moments is linked to whether reasoning models can intrinsically self-correct, i.e., revise their reasoning mid-response without external feedback. Model improvements often arise from extrinsic mechanisms like verifiers, reward queries, prompting techniques, or external tools . In contrast, intrinsic self-improvement must be inferred from reasoning traces and is arguably more safety-relevant, as it implies that a model can reorganize its reasoning from internal state alone .

/>

/>

Studying the effect of reasoning shifts is challenging. First, these events may occur (and affect performance) during training, yet evaluations are typically conducted only post-training . Second, reasoning models rarely release mid-training checkpoints, limiting longitudinal analyses across the training lifecycle. Third, even when shifts are observed, attributing correctness to a mid-trace change (rather than to general competence or memorization) requires systematically controlled comparisons. This gap motivates the need for a systematic investigation of whether reasoning shifts reflect genuine insight.

Present work. Here, we investigate whether mid-trace reasoning shifts (e.g., “Wait… let’s re-evaluate”) signal intrinsic self-correction in reasoning models. Our study is guided by three questions:

RQ1: Do reasoning shifts raise model accuracy?

RQ2: How does the effect of reasoning shifts vary with training stage and decoding temperature?

RQ3: Are reasoning shifts more effective when reasoning models are uncertain?

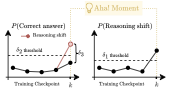

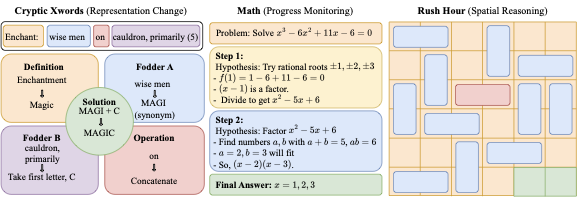

To answer these, we (i) formalize “Aha!” moments as measurable mid-trace shifts in reasoning that improve performance on problems that were previously unsolved by the model (Fig. 2; §3); (ii) curate a diverse evaluation suite (§4) spanning cryptic crosswords , mathematical problem-solving (MATH-500) , and Rush Hour puzzles ; and (iii) GRPO-tune and annotate the reasoning traces of Qwen2.5 and Llama models (§5).

Our analysis spans $`1`$M+ annotated reasoning traces across hundreds of checkpoint evaluations (10–20 per model/run), 3 domains, 4 temperatures, 2 model sizes, and 2 model architectures, providing a longitudinal view of how mid-trace reasoning evolves during RL fine-tuning. With this setup, we connect shift behavior to both correctness and token-level uncertainty signals .

Our results show that reasoning shifts are rare (overall $`\sim`$6.31% of traces) and generally do not improve model accuracy (RQ1). We further find that their impact on accuracy does not reliably flip sign across training stages, but varies substantially with decoding temperature (RQ2). Finally, we find that spontaneously occurring shifts do not become reliably helpful under high uncertainty; however, externally triggered reconsideration under high entropy improves accuracy across benchmarks, including a +8.41pp improvement on MATH-500 (and smaller gains on crosswords and Rush Hour) (RQ3). Our results are robust across datasets, prompts, and model families.

Contributions. We make three key contributions:

-

Definition & framework. We formalize “Aha!” moments as measurable mid-trace shifts and introduce an experimental framework for studying intrinsic self-correction during RL fine-tuning.

-

Empirical characterization at scale. Across $`1`$M+ traces spanning domains, temperatures, training stages, and model families, we show that reasoning shifts are rare and typically coincide with lower accuracy, challenging the view that they reflect genuine insight.

-

Intervention. We develop an entropy-gated intervention that induces reconsideration when models are uncertain, yielding measurable accuracy gains.

Related Work

Emergent Capabilities. Large language models often appear to acquire new abilities abruptly with scale—such as multi-step reasoning or planning —but it remains debated whether these shifts reflect intrinsic cognitive change or artifacts of evaluation . Many behaviors labeled as “emergent” arise only under extrinsic scaffolds. Structured prompts—e.g., Chain-of-Thought , the zero-shot cue “Let’s think step by step” , or Least-to-Most prompting —elicit intermediate reasoning that models rarely produce on their own. Optimization methods such as SFT , RLHF , and GRPO reinforce these externally induced behaviors, potentially amplifying the appearance of intrinsic ability gains.

Self-Correction and “Aha!” Moments. Self-correction in reasoning models can arise through extrinsic mechanisms—such as verifier models or tool calls —or through intrinsic shifts that occur without any external intervention . Recent work has examined these dynamics, including frameworks for trained self-correction and benchmarks for iterative refinement , and analyses of mid-inference adjustments . Studies of models such as DeepSeek-R1 suggest that reward optimization can induce intrinsic reflection-like artifacts. However, other works have raised doubts about whether observed reasoning shifts reflect genuine insight or superficial self-reflection . Yet, there has been no systematic evaluation of whether RL-trained models exhibit true intrinsic “Aha!”-style self-correction throughout RL fine-tuning, nor whether such shifts reliably improve correctness when tracked across checkpoints and decoding regimes.

Insight Characterization. In cognitive psychology, insight is classically defined as an abrupt restructuring of the problem space, exemplified by ’s chimpanzees stacking boxes to reach bananas. Recent work seeks analogous phenomena in reasoning models: mid-trace uncertainty spikes—sometimes described as “Gestalt re-centering”—have been associated with shifts in reasoning strategy . Metrics such as RASM aim to identify linguistic or uncertainty-based signatures of genuine insight , yet existing approaches misclassify superficial hesitations as insight at high rates in some settings (up to 30%) . These limitations highlight the need for rigorous criteria to distinguish genuine restructurings from superficial reflection.

Safety, Faithfulness, and Alignment. Transparent reasoning traces are central to alignment and faithfulness, as they allow human oversight of not only a model’s outputs but the process that produces them . When self-corrections occur without oversight, they raise concerns about hidden objective shifts or deceptive rationales that can mislead users . Process supervision—rewarding intermediate reasoning steps rather than only final answers—has been shown to improve both performance and interpretability in math reasoning tasks . Complementing this, uncertainty-aware methods help models detect and respond to unreliable reasoning (e.g., via abstention or filtering when uncertainty is high), improving robustness and trustworthiness . Understanding whether mid-trace shifts reflect genuine correction or uncertainty-driven artifacts is therefore directly relevant to evaluating the safety and reliability of reasoning models.

Formalizing “Aha!” Moments

We define an “Aha!” moment as a discrete point within a model’s chain-of-thought where the model abandons its initial reasoning strategy and adopts a qualitatively different one that improves performance. We formalize this notion below.

Let $`\{f_{\theta_k}\}_{k=0}^K`$ denote a sequence of checkpointed

reasoning models. At checkpoint $`k`$, the model defines a policy

$`\pi_{\theta_k}(a_t \mid a_{ denote expected correctness. Let $`S_{q_j,k}(\tau) \in \{0,1\}`$

indicate whether a mid-trace shift occurs in a sampled trajectory

$`\tau`$ at checkpoint $`k`$. This binary label is produced by our

shift-detection pipeline, which identifies lexical and structural

changes in reasoning strategy (detailed in

App. 11.1). We write

$`P(S_{q_j,k}=1)`$ for the probability (under

$`\tau \sim \pi_{\theta_k}`$) that a sampled trace contains a detected

shift. Definition 1 (“Aha!” Moment). Let

$`\delta_1,\delta_2,\delta_3 \in [0,1]`$ be thresholds for prior

failure, prior stability, and required performance gains. An “Aha!”

moment occurs for $`(q_j,k)`$ iff: $`\forall i < k,\; P_{\theta_i}(\checkmark \mid q_j) < \delta_1`$

(Prior failures), $`\forall i < k,\; P(S_{q_j,i}=1) < \delta_2`$ (Prior

stability), $`P_{\theta_k}(\checkmark \mid q_j, S_{q_j,k}=1) - P_{\theta_k}(\checkmark \mid q_j) > \delta_3`$

(Performance gain). In plain terms, a checkpoint $`k`$ qualifies as an “Aha!” moment for

$`q_j`$ if: (1) all earlier checkpoints consistently fail on the problem

(prior failures); (2) earlier checkpoints show little evidence of

mid-trace shifts (prior stability); and (3) at checkpoint $`k`$,

traces containing a detected shift yield a strictly higher correctness

rate than traces overall (performance gain).2 Together, these

conditions ensure that a detected shift is both novel and

beneficial, preventing superficial or noisy variations from being

counted as insight-like events.

Figure 2 illustrates this behavior.

Algorithm [alg:aha-moment] in

App. 11.1 formalizes the detection

procedure. The thresholds $`(\delta_1,\delta_2,\delta_3)`$ act as tunable criteria:

stricter values prioritize precision by requiring consistent prior

failure and rare prior shifts, while looser values increase recall. In

our experiments, we select these thresholds on a held-out development

slab and validate robustness using bootstrap confidence intervals

(App. 12.2). In all

cases, probabilities such as $`P_{\theta_k}(\checkmark \mid q_j)`$ and

$`P_{\theta_k}(\checkmark \mid q_j, S_{q_j,k}=1)`$ are estimated from

finitely many sampled traces per $`(q_j,k)`$. This definition parallels the classical cognitive characterization of

insight: a sudden restructuring of the problem space that enables

solution . Hallmarks of such shifts include explicit self-reflective

cues (e.g., “wait,” “let’s reconsider’’) and an observable pivot in

strategy . Theoretical accounts such as representational change theory ,

progress monitoring theory , and Gestalt perspectives on problem-solving

provide complementary lenses for interpreting analogous shifts in

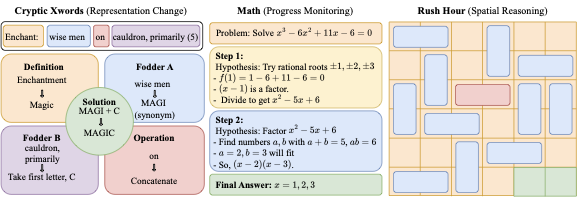

reasoning models. Our evaluation suite spans three complementary reasoning lenses

(Fig. 3): representational change in

cryptic Xwords (left), quantitative problem solving (center), and

spatial reasoning in RHour–style puzzles (right). Each domain offers

automatic correctness checks, natural opportunities for mid-trace

verification, and structured signals of strategy. All data are in

English; dataset sizes and splits are summarized in

Table 6, and additional filtering and

scoring details are provided in

App. 10.1. Throughout, we score answers

by normalized exact match (canonicalizing case, whitespace, and

punctuation before exact comparison;

App. 10.1). Cryptic Xwords. Cryptic Xwords clues hide a wordplay instruction

(e.g., anagram, abbreviation, homophone) beneath a misleading surface

reading, requiring representational shifts to solve. We train on natural

clues from Cryptonite and evaluate on a

synthetic test set with device-balanced templates

(App. 10.1), scoring by normalized exact

match. Math. Math word problems test symbolic manipulation and multi-step

deduction, with reasoning progress naturally expressed step-by-step. We

train on RHour. We synthetically generate

RHour sliding-block puzzles, where the

goal is to free a target car from a crowded grid by moving obstructing

vehicles. We generate balanced $`4{\times}4`$, $`5{\times}5`$, and

$`6{\times}6`$ boards and evaluate on $`6{\times}6`$ only. Boards are

solved optimally via BFS with per-size node caps, discarding timeouts

(App. 10.1). We filter trivial cases and

stratify remaining instances into easy ($`<`$4 moves), medium

($`<`$6), and hard ($`\geq`$6) buckets by solution

length. We fine-tune reasoning models with GRPO across evaluation domains

(§5.1); collect and annotate reasoning traces

during training (§5.2); and estimate model uncertainty to

trigger entropy-based interventions

(§5.3). Motivated by claims of mid-trace “Aha!” behavior in DeepSeek-R1 , we

adopt Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) as our fine-tuning

method. GRPO is an RLHF-style algorithm that optimizes chain-of-thought

generation by comparing groups of sampled completions and extends PPO

with group-normalized advantages and KL regularization to a frozen

reference policy. Full implementation details appear in

App. 10.4. We fine-tune Qwen2.5 and Llama 3.1 models on each domain for up to

1,000 steps. Our primary experiments use Qwen2.5-1.5B trained for 1,000

steps ($`\approx`$2.5–3 epochs per domain), while larger models

(Qwen2.5-7B and Llama 3.1-8B) are evaluated at 500 steps due to compute

constraints. To verify that models improve during training, we evaluate

at multiple checkpoints and report accuracy at initialization (Step 0)

and at the final evaluated checkpoint (Step 950 for the 1.5B runs;

Step 500 for 7B/8B).

Table 1 summarizes coverage and accuracy

gains. We use lightweight, task-specific prompts that structure reasoning into

a Model coverage and learning progress. Accuracy at initialization

(Step 0) and at the final training checkpoint, along with the absolute

gain ($`\Delta`$). All results are 1-shot evaluations at temperature

$`0`$ on the fixed test sets described in

§4. We evaluate each model at a fixed cadence of every 50 training steps

from initialization (Step 0) to Step 950 inclusive (i.e., checkpoints

$`k\in\{0,50,\ldots,950\}`$), yielding 20 checkpoints per run. At each

checkpoint, we generate $`G{=}8`$ completions per problem using a

fixed decoding policy (temperature $`\{0,0.05,0.3,0.7\}`$,

top-$`p{=}0.95`$). Each completion follows the tag-structured output

contract in

App. 10.2, with private

reasoning in Evaluation sets are held fixed across checkpoints: 500 problems for

MATH-500, 130 synthetic clues for

Xwords, and 500 $`6{\times}6`$ RHour boards. For our Qwen2.5-1.5B

models, because each item is evaluated at all 20 checkpoints across

$`T{=}4`$ temperatures with $`G{=}8`$ samples, each run yields 320,000

Math traces, 83,200 Xwords traces, and 320,000 RHour traces. This

longitudinal structure allows us to track how mid-trace behavior evolves

during RL fine-tuning. We additionally produce 160,000 Qwen2.5-7B traces

and 160,000 Llama3.1-8B traces for

MATH-500 across 10 checkpoints (Step 0 to

Step 450 every 50 steps) to investigate behavior across architecture and

model size. Details about our training and evaluation setup appear in

App. 10.1. To identify reasoning shifts at scale, we use GPT-4o as an LLM-as-judge.

Following evidence that rubric-prompted LLMs approximate human

evaluation , we supply a fixed rubric that scores each trajectory for

(i) correctness, (ii) presence of a mid-trace reasoning shift, and (iii)

whether the shift improved correctness. To reduce known sources of judge bias—position, length, and model

identity effects —we randomize sample order, use split–merge

aggregation, enforce structured JSON outputs, and ensemble across prompt

variants. We also adopt a conservative error-handling policy: we assign

no shift when the cue prefilter fails or when the judge output is

invalid or low-confidence

(App. 11.2). Agreement is high: on

MATH-500, GPT-4o achieves

$`\kappa\!\approx\!0.726`$ across prompt variants and $`\kappa=0.79`$

relative to human majority vote, comparable to expert–expert reliability

. For additional details, see

App. 11.3. For qualitative examples,

see App. 13.6. To relate reasoning shifts to model uncertainty, we measure token-level

entropy throughout each response. At generation step $`t`$, with

next-token distribution $`\mathbf{p}_t`$, we compute Shannon entropy

$`H_t = -\sum_v p_t(v)\log p_t(v)`$. For each completion, we summarize

uncertainty by averaging entropy over the We also study whether uncertainty can be exploited to improve

performance via artificially triggered reflection. In a follow-up

experiment, we test three semantically similar but lexically distinct

reconsideration cues (C1–C3), for example: (C3) “Wait, something is not

right, we need to reconsider. Let’s think this through step by step.”

For each cue, we first obtain the model’s baseline completion (Pass 1),

then re-query the model with the same decoding parameters while

appending the reconsideration cue (Pass 2). We evaluate gains both

overall and under an entropy gate: we split instances into

high-entropy (top 20% within domain) and low-entropy (bottom 80%)

buckets based on Pass 1 sequence entropy, and compare Pass 2 accuracy

across buckets. Cue-specific results and regressions are reported in

App. 12.4. We show that spontaneous reasoning shifts are rare and generally harmful

to accuracy, and that formal “Aha” events are vanishingly rare (RQ1;

§6.1); that this negative effect

remains stable across training stages but varies systematically with

decoding temperature (RQ2;

§6.2); and that extrinsically

triggered shifts reliably improve performance, especially on

high-entropy instances (RQ3;

§6.3). Do reasoning shifts improve accuracy? Before analyzing formal “Aha!”

moments, we first consider the broader class of reasoning shifts—any

mid-trace pivot detected by our annotator, irrespective of whether it

satisfies the stricter criteria in

Def. 1. If such shifts reflected

genuine insight, traces containing them should be more accurate than

those without them. Across domains, temperatures, and checkpoints for Qwen2.5–1.5B,

reasoning shifts remain uncommon (approximately $`7.6\%`$ of samples;

pooling all models/domains yields 6.31%) and are associated with

substantially lower accuracy: $`2.57\%`$ for shifted traces versus

$`16.44\%`$ for non-shifted traces, $`N{=}723{,}200`$. A pooled logistic

regression of correctness on a shift indicator confirms that this

difference is highly significant (p $`< 10^{-1198}`$).3 To test whether this pattern is specific to small GRPO-tuned models, we

evaluate DeepSeekR1 and GPT4o under matched decoding conditions on

MATH. As shown in

Table [tab:external-models], both

models exhibit very low canonical shift rates across temperatures

(0.40–0.60% for DeepSeekR1 and 2.20–3.00% for GPT4o), and accuracy

conditioned on a shift shows no systematic benefit, suggesting that the

phenomenon generalizes across model families and training paradigms.

These results characterize the “raw” behavioral signature of mid-trace

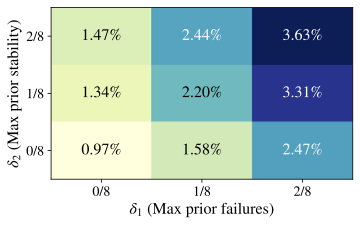

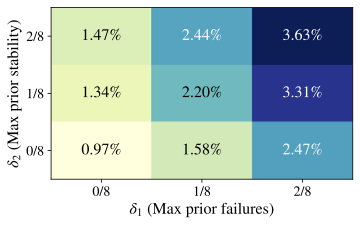

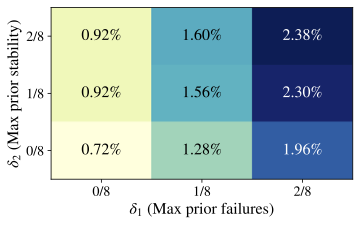

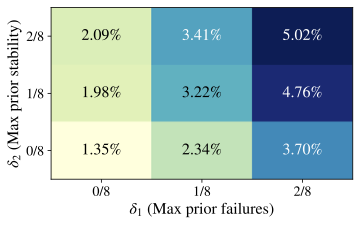

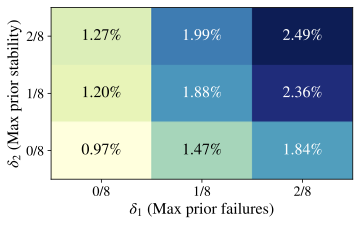

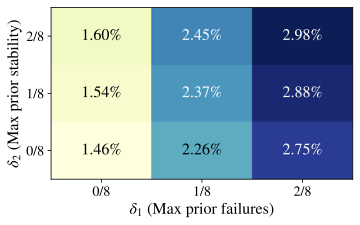

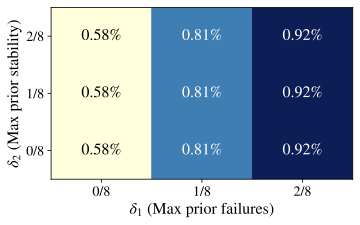

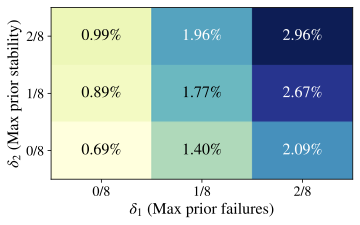

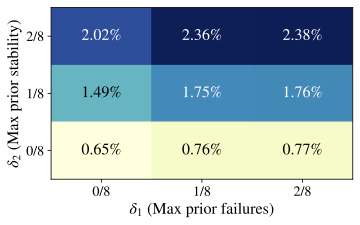

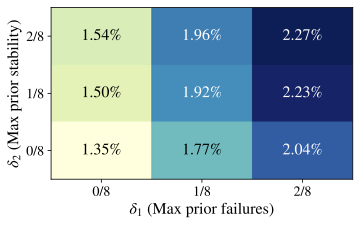

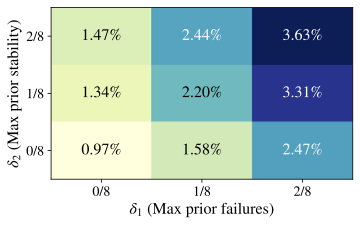

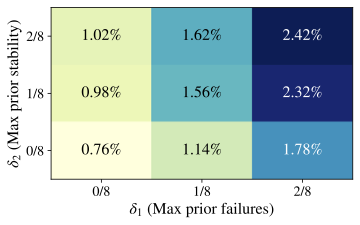

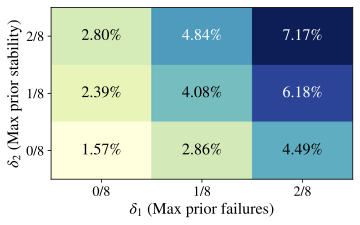

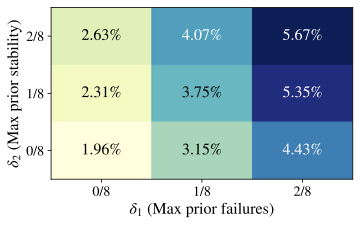

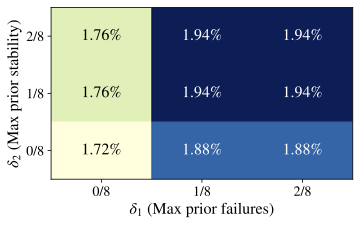

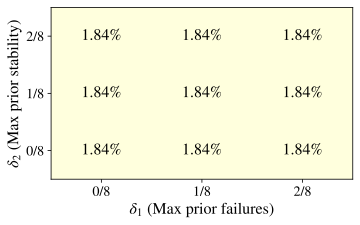

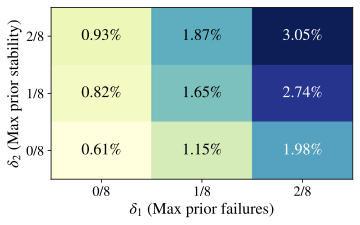

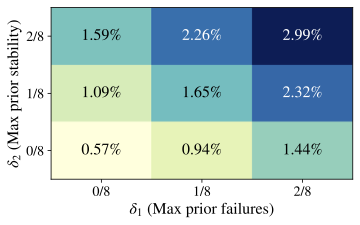

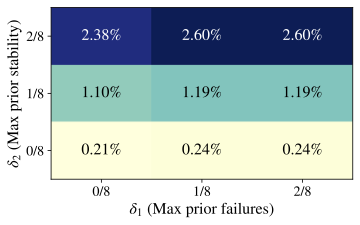

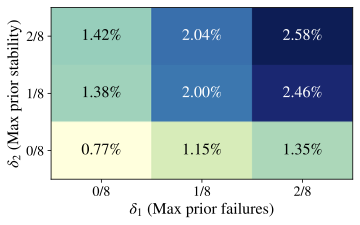

shifts, independent of any stricter “Aha!” interpretation. How frequent are formal “Aha!” moments? We now restrict attention to

the much smaller subset of events that satisfy all three criteria in

Def. 3. In

Fig. 4, by varying

$`\delta_1,\delta_2\in\{0,\,1/8,\,2/8\}`$ and fixing

$`\delta_3=\epsilon>0`$, we find that formal “Aha!” moments are

extremely rare, even with relatively lax constraints. Similar patterns

hold for Qwen2.5–7B and Llama3.1–8B

(App. 12). Pooling every

Crossword/Math/RHour checkpoint and temperature, the formal detector

fires on only $`1.79\%`$ of samples. Robustness checks. As surface cues such as “wait” or “actually”

often fail to track genuine strategy changes , and LLM-judge labels may

pick up prompt- or position-induced biases , we replicate RQ1 using

three detector variants (formal, GPT-based, lexical). All yield the same

conclusion; see

App. 12.6. Takeaway. Reasoning shifts are infrequent and generally harmful to

accuracy. Further, formal “Aha!” moments, which additionally require a

performance gain at the pivot, are vanishingly rare. Neither the general

phenomenon (reasoning shifts) nor its idealized form (“Aha!” moments)

appears to drive problem-solving performance of reasoning models. RQ1 establishes two constraints on “insight-like” behavior: broad

reasoning shifts are uncommon and tend to coincide with worse outcomes,

while formal “Aha!” events are so rare that they contribute little to

overall model performance. This raises a natural question: are we simply

averaging over regimes where shifts sometimes help and sometimes hurt?

We test two plausible sources of heterogeneity: (i) shifts might become

more (or less) effective at different stages of training; and (ii)

their impact might depend on the decoding temperature (and thus

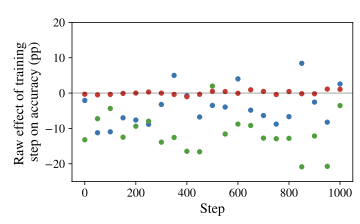

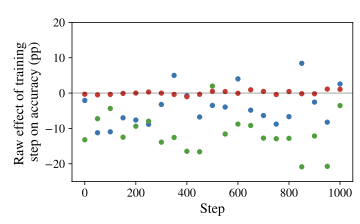

sampling entropy). How does the effect of reasoning shifts vary across training? To

test whether the shift–accuracy relationship changes as training

progresses, we regress correctness on problem fixed effects,

standardized training step, and the shift indicator. We report average

marginal effects (AME) with cluster–robust SEs at the problem level.

4 At $`T{=}0.7`$, we find no evidence that shifts become beneficial later

in training. In Xwords and Math shifts are uncommon

($`\%S{=}2.433`$; $`\%S{=}2.166`$) and are mildly harmful

($`\mathrm{AME}{=}{-}0.0311`$, $`p{=}0.02742`$;

$`\mathrm{AME}{=}{-}0.0615`$, $`p{=}1.55\times10^{-4}`$). In RHour, shifts are comparatively frequent ($`\%S{=}11.449`$) but

have no measurable practical effect on accuracy

($`\mathrm{AME}{\approx}0.0001`$, $`p{\ll}10^{-6}`$). Analogous results

for $`T\in\{0.0,0.05,0.3\}`$ are reported in

Appendix 13.1.

Figure 7a echoes this pattern:

across checkpoints, shifted traces are not systematically more accurate

than non-shifted ones. We repeat robustness checks using alternative

detector variants across $`T\in\{0,0.05,0.3,0.7\}`$ in

App. 13.5. We observe the same qualitative

pattern with the stricter formal “Aha!” detector

(Appendix 13.3), but because it fires

on only $`\approx 10^{-3}`$ of traces at $`T{=}0.7`$, estimates are

underpowered for fine-grained stage-by-stage heterogeneity; critically,

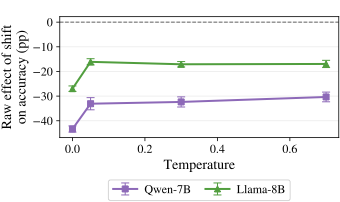

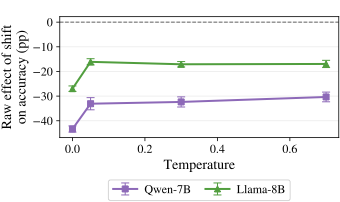

we do not see a consistent late-training transition to positive effects. How does the effect of reasoning shifts vary with decoding

temperature? We next ask whether temperature modulates the

relationship between shifts and correctness. We regress correctness on

problem fixed effects, standardized temperature, and the shift

indicator, aggregating across training steps. 5 Table 3 summarizes the average association between

shifts and correctness while controlling for standardized decoding

temperature (via Raw per-temperature contrasts

(Fig. 6) sharpen the interpretation:

on Xwords, shifts can coincide with productive correction at low

$`T`$, but the benefit weakens and may reverse by $`T{=}0.7`$. In

Math, shifts remain harmful across temperatures, though the raw

penalty attenuates as $`T`$ increases. In RHour, the curve stays close

to zero in magnitude, reflecting the near-zero accuracy regime. Takeaway. We find that reasoning shifts do not reliably yield higher

accuracy across specific training phases or at particular temperatures. The results above (particularly Xwords, see

Fig. 6) suggest that decoding

temperature may modulate the effect of reasoning shifts: at low $`T`$

they sometimes align with productive corrections, while at higher $`T`$

they resemble noise. Because temperature primarily alters sampling

entropy rather than the model’s underlying reasoning process , this

points to a link between shifts and internal uncertainty. We thus ask

whether, under high-uncertainty regimens, reasoning shifts are more

frequent or become more helpful. Are reasoning shifts more likely under high uncertainty? To test

whether shifts preferentially occur when the model is uncertain, we

relate each trace’s reasoning shift indicator to its sequence-level

entropy. We pool traces across all decoding temperatures and training

checkpoints, and fit a logistic regression of shift prevalence on

standardized entropy with problem fixed effects and cluster-robust SEs

(clustered by problem). 6 Pooling all traces across domains (Xwords, Math, RHour), we find

weak evidence that higher entropy is associated with fewer detected

shifts on average (OR$`\approx 0.77\times`$, $`\beta=-0.258`$,

$`\mathrm{SE}=0.143`$, $`p=0.070`$; 95% CI OR $`\in[0.58,1.02]`$;

$`N=723{,}200`$). This aggregate pattern masks domain heterogeneity: the

entropy–shift association is positive in Xwords

(OR$`\approx 2.05\times`$) and RHour (OR$`\approx 1.19\times`$), but

negative in Math (OR$`\approx 0.58\times`$). One possible

interpretation is that in Math, high-entropy generations more often

reflect diffuse exploration or verbose “flailing” rather than a discrete

mid-trace pivot, so the rare, rubric-qualified shifts concentrate in

comparatively lower-entropy traces. Do reasoning shifts improve performance under high uncertainty? A

natural hypothesis is that when the model is uncertain, a mid-trace

pivot might reflect productive self-correction. We test this by

stratifying traces into high-entropy instances (top 20% within domain)

and low-entropy instances (bottom 80%), using a fixed entropy

threshold per domain. Within each stratum, we estimate the effect of a

shift on correctness using a logistic regression with problem fixed

effects and controls for continuous entropy and training step, and

report the shift coefficient alongside the raw accuracy difference

between shifted and non-shifted traces. 7 Table 4 shows that shifts do

not become reliably beneficial in the high-entropy regime. In Math,

shifts remain harmful even among high-entropy traces (raw

$`\Delta=-7.40`$pp) and are substantially more harmful in the

low-entropy majority (raw $`\Delta=-22.88`$pp). In Xwords, the point

estimate in the high-entropy stratum is near zero (raw

$`\Delta=+0.63`$pp), but shifts are rare and estimates are noisy. In

RHour, accuracy is near-zero throughout, so estimated effects are

statistically detectable due to sample size but negligible in magnitude. Can artificially triggered reasoning shifts improve performance? The

negative results above suggest that spontaneous shifts are not a

dependable self-correction mechanism, even when the model is uncertain.

High entropy does not cause more spontaneous pivots; rather, it

identifies instances where a second-pass reconsideration has higher

marginal value. We therefore test an extrinsically triggered “forced

Aha” intervention: for each prompt we generate a baseline completion

(Pass 1), then re-query the model under identical decoding settings

while appending a reconsideration cue (Pass 2), and compare paired

correctness outcomes. Pass 2 uses the same cue across all domains; see

App. 12.4 for the exact

wording and additional analyses. Table 5 reports paired results

aggregated across checkpoints and decoding temperatures. Triggered

reconsideration yields a large gain on Math

($`0.322\!\rightarrow\!0.406`$; $`+8.41`$pp) and a small gain on

Xwords ($`+0.45`$pp), while remaining negligible in absolute terms on

RHour ($`+0.01`$pp) due to its near-zero base rate. The paired “win”

counts show that improvements dominate backslides in Math (50,574

wrong$`\rightarrow`$right vs. 23,500 right$`\rightarrow`$wrong),

indicating that the effect is not merely random flipping. In contrast,

Xwords shows near-balanced wins and losses (5,380 vs. 5,004),

consistent with a much smaller net gain. Finally, consistent with uncertainty serving as a useful gate for

reflection,

Appendix 12.4 shows that these

gains are amplified on high-entropy instances

(Table 18), with a complementary

regression analysis reported in

Table 19. Forced “Aha” (triggered reconsideration), sample-level results. We

compare paired outcomes between a baseline generation (Pass 1) and a

second generation with an appended reconsideration cue (Pass 2).

$`\hat p_{\text{P1}}`$ and $`\hat p_{\text{P2}}`$ denote accuracies in

each pass; $`\Delta`$ (pp) is the percentage-point gain. Takeaway. Reasoning shifts are a low-base-rate event whose

association with entropy varies by domain, and conditioning on

uncertainty does not reveal a “hidden regime” where spontaneous shifts

reliably help. In contrast, artificially triggering reconsideration

yields consistent gains, especially for Math and especially in the

high-entropy tail

(App. 13.7,

Table 18). We formalize and empirically test the notion of intrinsic “Aha!”

moments, mid-trace reasoning shifts that appear to reflect sudden

insight. We find that they are vanishingly rare and that mid-trace

reasoning shifts are typically unhelpful, even in states of high

uncertainty. However, by intervening to trigger reconsideration under

high-entropy conditions, we demonstrate that uncertainty can be

converted into productive reflection, resulting in measurable accuracy

gains. This reframes reasoning shifts not as an emergent cognitive ability, but

as a mechanistic behavior—a byproduct of the model’s inference dynamics

that can nonetheless be harnessed and controlled. Rather than asking

whether models have insight, it may be more useful to ask how and when

they can be made to simulate it. This shift in perspective bridges

recent work on uncertainty-aware decoding , process supervision , and

self-correction , positioning mid-trace reasoning as a manipulable

mechanism for improving reliability rather than genuine insight. Our findings open several directions for further investigation. First,

the link we uncover between uncertainty and the usefulness of

mid-reasoning shifts invites new forms of process-level supervision that

explicitly condition reflection on entropy or confidence estimates .

Second, future work should examine whether RL-based objectives that

reward models for revising earlier answers truly improve reasoning or

merely reinforce uncertainty-responsive heuristics. While recent

approaches such as demonstrate that self-correction can be trained, our

results highlight the need for analyses that disentangle the learning of

reflection-like language from genuine representational changes. It would

be valuable to investigate what the observed dynamics between

uncertainty and mid-reasoning shifts reveal about human insight—whether

uncertainty-driven reconsideration in models mirrors metacognitive

signals in people, or whether the resemblance is purely linguistic.

Bridging computational and cognitive accounts of “Aha!” phenomena could

help identify which internal mechanisms, if any, correspond to genuine

insight. Finally, we hope that this piece inspires more fundamental

research into the impact of RL post-training on model performance: why

do algorithms like GRPO lead to a performance shift if not from improved

reasoning? While our study offers the first systematic analysis of “Aha!” phenomena

in reasoning models, it has several limitations. First, our detection of

reasoning shifts relies on explicit linguistic cues (e.g., “wait,”

“actually”) and measurable plan changes. This makes our estimates

conservative: models may undergo unlexicalized representational changes

that our detector misses, while some detected shifts may instead reflect

superficial hedges. Future work could incorporate hidden-state dynamics

or token-level embeddings to better identify implicit restructurings.

Second, our evaluation spans three reasoning domains but remains limited

to tasks with well-defined correctness signals (math, Xwords, spatial

puzzles). Whether similar patterns hold for open-ended reasoning or

multi-turn interaction remains an open question. Third, our intervention

experiments manipulate model behavior via prompt-level cues rather than

modifying training objectives. Thus, while we demonstrate that

uncertainty-gated reconsideration can improve accuracy, this does not

establish a causal mechanism of internal insight. Extending our analysis

to training-time interventions or process supervision would help clarify

how reflection-like behaviors emerge and generalize. Finally, as with

most large-model studies, our results depend on a small set of families

(Qwen, Llama) and inference hyperparameters (e.g., temperature, sampling

policy). Broader replications across architectures, decoding methods,

larger sizes, and reinforcement-learning setups are necessary to test

the generality of our conclusions. Our study analyzes the internal reasoning behavior of large language

models and does not involve human subjects or personally identifiable

data. All datasets used—MATH-500 ,

Cryptonite , and synthetic

RHour puzzles—are publicly available and

contain no sensitive content. We follow the terms of use for each

dataset and model. Because our work involves interpreting and modifying model reasoning

traces, it carries two potential ethical implications. First, methods

that manipulate mid-trace behavior could be misused to steer reasoning

models toward undesirable or deceptive outputs if deployed

irresponsibly. Our interventions are limited to controlled research

settings and designed to study model uncertainty, not to conceal

reasoning or produce persuasive content. Second, interpretability claims

about “insight’’ or “self-correction’’ risk overstating model

understanding. We therefore emphasize that our findings concern

statistical behavior, not human-like cognition or consciousness. Generative AI tools were used to enhance the search for related works

and to refine the writing and formatting of this manuscript. We followed

the recommendations of , who provide guidance for legitimate uses of AI

in research while safeguarding qualitative sensemaking. Specifically,

Claude, ChatGPT, and Elicit were used to identify relevant research

papers for the Related Work and Discussion sections (alongside

non-generative tools such as Google Scholar and Zotero). After the

Discussion had been written, ChatGPT was used to streamline and refine

the prose, which was then manually edited by the authors. Claude and

ChatGPT were additionally used for formatting tasks, such as generating

table templates and translating supplementary materials to LaTeX. Where

generative AI was used, the authors certify that they have reviewed,

adapted, and corrected all text and stand fully behind the final

content. All model runs, including training and inference, were conducted on

NVIDIA A100 GPUs or NVIDIA A6000 GPUs, with resource management, access

controls, and energy considerations in place. We estimate the total

carbon footprint of all experiments at

approximately 110 kg CO2e, following the methodology of . This work was supported by a First-Year Fellowship from the Princeton

University Graduate School. We are grateful for computational resources

provided by the Beowulf cluster, and we thank the ML Theory Group for

generously sharing additional compute. We also acknowledge the support

of the Center for Information Technology Policy (CITP) and the

Department of Computer Science at Princeton University. We thank our

volunteer annotators and the broader Princeton community. Special thanks

to Cannoli, our lab dog, and to the musical artist, Doechii. This first part of the appendix collects the reproducibility

scaffolding for our experiments: what data we train and evaluate on,

what prompts and output contracts we impose, and how GRPO training is

configured. We begin with dataset sizes and domain-specific

preprocessing details

(§10.1). We then provide the

verbatim system-level prompts used in each domain, including the shared

Table 6 summarizes dataset sizes, splits,

and evaluation coverage for all three reasoning domains. We include

additional details here for reproducibility. We use the Cryptonite corpus for training

and generate synthetic evaluation clues using device-balanced templates.

All answers are normalized (uppercase, punctuation-stripped) before

exact-match scoring. The training distribution is We generate balanced $`4{\times}4`$, $`5{\times}5`$, and $`6{\times}6`$

puzzles and evaluate on $`6{\times}6`$ only. Puzzles are solved

optimally via BFS with per-size node caps; unsolved or degenerate boards

are removed . Solutions are canonicalized before comparison. Code to regenerate the synthetic Cryptic Xwords evaluation set and the

selected RHour puzzles is included in our repository under System Prompt — Cryptic Xwords You are an expert

cryptic-xword solver. Do this (repeat until fully consistent): A) DEVICE

TRIAGE • List plausible devices from anagram, container, reversal,

hidden, charade, deletion, homophone, double def, &lit, letter

selection, substitution, abbr. • For each, quote the indicator

word(s). Reject with a reason. B) PARSE • Mark the **definition** (start

or end). • Mark the **wordplay** with exact fodder + operations. C)

CHECKS • Enumeration must match exactly. • Letter accounting must be

exact (anagram multiset or stepwise build). D) DECIDE • Pick the

candidate best matching definition, indicator(s), and enumeration. • Do

NOT assume anagram without a clear anagrind and fully used fodder. E)

RECONSIDER (if any check fails) • Begin the next <think> with:

"Wait, we need to reconsider. Let’s think this through step by step." •

Say why it failed, then re-run A–D with an alternative device/parse.

FORMAT (no deviations): • Reasoning only in <think>…</think>

• Final entry ONLY (UPPER-CASE) in <answer>…</answer> Clue:

Close, as seen in plaNET EARly (4) <think>Device: HIDDEN;

indicator "as seen in". Def: "Close". Wordplay: hidden in "plaNET EARly"

-> NEAR. Enumeration: (4) OK.</think> <answer> NEAR

</answer> Clue: Mix TEA for a hot drink (3) <think>Device:

ANAGRAM; indicator "Mix". Fodder TEA -> TEA. Def: "a hot drink".

Accounting exact; (3) OK.</think> <answer> TEA

</answer> Clue: Shoe liner at home on fish (6) <think>Device

triage: hidden ? ("on" is not a hidden indicator), anagram ✗ (no

anagrind), charade ✓ ("at home"=IN, "on"=next to), homophone ✗,

... Attempt (HIDDEN) rejected: no indicator; also hidden spans

don’t give (6). Candidate attempt (wrong path): — fails

enumeration/indicator, so we must rethink. Re-evaluate as CHARADES: IN

("at home") + SOLE ("fish") -> INSOLE. Accounting: INSOLE letters: I

N S O L E (6). Definition "Shoe liner" fits. Enumeration (6)

OK.</think> <answer>INSOLE</answer> Our system prompts serve two purposes: (i) scaffold domain-appropriate

reasoning with verifiable intermediate structure, and (ii) standardize

outputs so they are machine-checkable and comparable across checkpoints.

Across all domains we therefore (a) separate private reasoning from the

final response with explicit tags ( System Prompt — Math You are an expert *mathematics

problem-solver. Every time you receive a problem you must: • Analyze it

thoroughly. – Pinpoint the **goal** (what quantity/set/form is

requested). – Pinpoint the **givens/constraints** (domains, integrality,

non-negativity, geometric conditions). – Choose the **methods** to apply

(algebraic manipulation, factorization, inequalities, counting, modular

arithmetic, geometry, calculus, etc.). – Write out the full derivation

that leads to the final result. • Check that the result satisfies all

original constraints (no extraneous roots, correct domain, simplified

form, exact arithmetic). • Respond in **exactly** the tag-based format

shown below – no greeting, no commentary outside the tags. – The final

answer goes inside <answer> **only**. – Use **exact** math

(fractions, radicals, π, e). Avoid unnecessary decimals. – Canonical

forms: integers as plain numbers; reduced fractions a/b with b>0;

simplified radicals; rationalized denominators; sets/tuples with

standard notation; intervals in standard notation. – If there is **no

solution**, write NO SOLUTION. If the problem is **underdetermined**,

write I DON’T KNOW. • You have a hard cap of **750 output tokens**. Be

concise but complete. TAG TEMPLATE (copy this shape for every problem)

<think> YOUR reasoning process goes here: 1. quote the relevant

bits of the problem 2. name the mathematical tool(s) you apply 3. show

each intermediate step until the result is reached If you spot an error

or an unmet constraint, iterate, repeating steps 1–3 as many times as

necessary until you are confident in your result. Finish by verifying

the result satisfies the original conditions exactly

(substitution/checks). </think> <answer> THEANSWER

</answer> We ask models to reason entirely inside Dataset sizes. Training instances are natural clues (Xwords),

problems (Math), and boards (RHour); evaluation uses synthetic clues for

Xwords.

The Xwords prompt encodes established solving practice: device triage

(anagram, container, reversal, hidden, etc.) with quoted indicators,

followed by a two-part parse (definition and wordplay) and two

hard checks: exact enumeration and exact letter accounting. This

combination suppresses common failure modes such as defaulting to

anagrams without a bona fide anagrind or silently dropping letters in

charades. The reconsideration loop is narrow: it requires explaining

why the current attempt fails before proposing an alternative

device/parse. We found this prevents thrashing while still eliciting

genuine mid-trace pivots when a better device is available. Examples in

the prompt illustrate (i) a hidden, (ii) an anagram, and (iii) a

charade—covering the most frequent device classes in our corpus. The math prompt stresses (i) goal/givens/methods triage, (ii) exact,

symbolic manipulation with canonical forms (fractions, radicals,

$`\pi`$, $`e`$), and (iii) end-of-proof validation (domain, extraneous

roots, simplification). We explicitly specify what to output when a

problem is infeasible (“ System Prompt — RHour You are an expert RHour

(N×N) solver. TASK • Input fields are provided

in the user message: - Board (row-major string with ’o’, ’A’, ’B’..’Z’,

optional ’x’) - Board size (e.g., 4x4 or 5x5 or 6x6) - Minimal moves to

solve (ground-truth optimum), shown for training • OUTPUT exactly ONE

optimal solution as a comma-separated list of moves. - Move token =

<PIECE><DIR><STEPS> (e.g., A>2,B<1,Cv3) -

Directions: ’<’ left, ’>’ right, ’^’ up, ’v’ down - No spaces, no

prose, no extra punctuation or lines. GOAL • The right end of ’A’ must

reach the right edge. OPTIMALITY & TIE-BREAKS • Your list must have

the minimal possible number of moves. • If multiple optimal sequences

exist, return the lexicographically smallest comma-separated sequence

(ASCII order) after normalizing tokens. VALIDATION • Tokens must match:

^[A-Z][<>^v]+̣(,[A-Z][<>^v]+̣)*$ • Each move respects vehicle

axes and avoids overlaps with walls/pieces. • Applying the full sequence

reaches the goal with exactly moves moves. IF INCORRECT /

UNVALIDATED • Repeat reasoning process, iterating until correct. FORMAT

• Answer in the following way: <think> Your reasoning

</think> <answer> A>2,B<1,Cv3 </answer> For RHour puzzles, the prompt formalizes the interface between

natural-language reasoning and a discrete planner. Inputs are normalized

($`N\times N`$ board, row-major encoding), and The full configs, exactly as used for training, are available in our

repository under To probe how sensitive performance is to system-prompt wording, we

evaluated $`K{=}5`$ paraphrased system prompts for Prompts are released verbatim below. We use the same decoding policy

across checkpoints (temperature, top-$`p`$, stop criteria), cache RNG

seeds, and reject outputs that violate the format contracts before

computing task-specific rewards. This protocol ensures that improvements

in correctness or in “Aha!” prevalence reflect changes in the model’s

internal state rather than changes in instructions or graders. Figures

8,

9,

10 show our verbatim system level

prompts. We fine-tune instruction models (Qwen 2.5–1.5B, Qwen 2.5–7B,

Llama 3.1–8B) with Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) , using

task-specific, tag-constrained prompts that place private reasoning in

We use the OpenR1 GRPO trainer with a vLLM inference server for

on-policy rollouts and All rewards are per-sample and clipped to $`[0,1]`$. Xwords. Exact match on the inner Math. Requires the full tag template; the gold and predicted

RHour. Composite score combining exact (canonical token

sequence), prefix (longest common prefix vs. gold), solve (shorter

optimal solutions $`\uparrow`$), and a planning heuristic $`\Phi`$

(distance/blockers decrease $`\uparrow`$); when a board is provided we

legality-check and simulate moves, otherwise a gold-only variant

supplies solve/prefix shaping. Defaults (used here):

$`w_\text{exact}{=}0.65`$, $`w_\text{solve}{=}0.20`$,

$`w_\text{prefix}{=}0.10`$, $`w_\Phi{=}0.05`$. Across runs we use cosine LR schedules with warmup, clipped

advantages/values, and KL control targeting

$`\text{KL}_\text{target}\!\approx\!0.07`$ via an adaptive coefficient

($`\beta`$) with horizon $`50`$k and step size $`0.15`$; value loss

weight $`0.25`$; PPO/GRPO clip ranges $`0.05`$–$`0.10`$ depending on

run; horizon $`1024`$; $`\gamma{=}0.99`$, $`\lambda_\text{GAE}{=}0.95`$. We use fixed system prompts per domain that enforce exact formatting (no

deviation), encourage compact reasoning, and cap Table [tab:grpo-configs] summarizes only

the run-level choices that differ by domain/model; all other defaults

follow the overview above. We train with ZeRO-3 (stage 3), CPU offload for parameters and

optimizer, and the standard single-node launcher; the provided

Jobs were launched under Slurm on 8-GPU nodes, using a mix of NVIDIA

A100 and RTX A6000 GPUs. For the Qwen2.5-1.5B runs, we reserve

one GPU for vLLM rollouts and use the remaining GPUs for

This appendix details the pipeline used to (i) label mid-trace reasoning

shifts in individual generations and (ii) operationalize formal “Aha!”

events as a checkpoint-level phenomenon. We first present our formal

“Aha!” detector, which combines prior-failure, prior-stability, and

conditional-gain criteria

(App. §11.1). We then describe the

trace-level shift annotation protocol used throughout the paper

(App. §11.2). Finally, we document the

LLM-as-a-judge reliability protocol and the human-labeling template used

for validation

(App. §11.3 and

App. §11.4). Alg. [alg:aha-moment] operationalizes

Def. 1 and

Fig. 2 via three checks: Prior failures: for $`q_j`$, all checkpoints $`i Prior stability: mid-trace shifts are rare for $`i Conditional gain at $`k`$: when a mid-trace shift occurs at

$`k`$, expected correctness increases by a prescribed margin. For each pair $`(q_j,k)`$ we draw $`M`$ independent traces

$`\tau^{(m)} \sim \pi_{\theta_k}(\cdot \mid q_j)`$ under a fixed

decoding policy (temperature $`\tau`$, top-$`p`$, and stop conditions

held constant across $`k`$): For the conditional estimate we average only shifted traces at $`k`$: with a tiny $`\epsilon`$ (e.g., $`10^{-6}`$) to avoid division by zero.

If the denominator is $`0`$, Step 3 is inconclusive and the procedure

returns . We mark a generation as shifted if it contains both: (i) a lexical

cue of reconsideration (e.g., “wait”, “recheck”, “let’s try”, “this

fails because …”), and (ii) a material revision of the preceding plan

(rejects/corrects an earlier hypothesis, switches method or candidate,

or resolves a contradiction). We implement this with a conservative

two-stage detector (lexical cue prefilter + rubric-guided adjudication)

described in

App. §11.2. To calibrate superficial

hedges and edge cases, we tuned thresholds for the cue matcher and

clamping on a small, human-verified set

(App. §11.4). For each $`i and we require $`\widehat{\Pr}[S_{q_j,i}{=}1] < \delta_2`$ for all

$`i We set $`(\delta_1,\delta_2,\delta_3)`$ on a held-out development slab

by maximizing F1 for Aha

vs. non-Aha against human labels. Unless

stated otherwise, we use $`\delta_1{=}0.125`$ (prior correctness

ceiling), $`\delta_2{=}0.125`$ (shift-rate ceiling), and

$`\delta_3{=}0.125`$ (minimum gain). To guard against Monte Carlo noise

in $`\hat P`$, we further require the one-sided bootstrap CI (2000

resamples over traces) for

$`\hat P_{\theta_k}(\checkmark \mid q_j, S{=}1) - \hat P_{\theta_k}(\checkmark \mid q_j)`$

to exceed $`0`$ at level $`\alpha{=}0.05`$. If this test fails, Step 3

returns . Step 1: Prior failures Step 2: Prior stability Step 3: Performance gain

$`p_k \gets P_{\theta_k}(\text{correct}\mid q_j)`$

$`p^{\text{shift}}_{k} \gets P_{\theta_k}(\text{correct}\mid q_j,\; S_{q_j,k}{=}1)`$ Unless noted otherwise, we use $`M{=}8`$ samples per $`(q_j,k)`$,

top-$`p{=}0.95`$, temperature $`\tau{=}0.7`$, and truncate at the first

full solution (math), full entry parse (xword), or solved board state

(RHour). We cache RNG seeds so cross-checkpoint comparisons differ only

by $`\theta_k`$. The detector uses $`O(JKM)`$ forward passes (plus inexpensive

prefiltering and adjudication), where $`J`$ is the number of items and

$`K`$ the number of checkpoints. We cache

$`\{\tau^{(m)}, R(\tau^{(m)}), S(\tau^{(m)})\}`$ per $`(q_j,k)`$ for

reuse in ablations (temperature sweeps, entropy bins). (i) If any $`i For each $`(q_j,k)`$ we log: the prior-failure margin

$`\delta_1-\max_{i Our shift detector may miss unlexicalized representational changes

(false negatives) and can be triggered by surface hedges if the

adjudicator fails (false positives). The bootstrap addresses variance

within checkpoints but not dataset shift across checkpoints; we

therefore hold decoding hyperparameters fixed across $`k`$. We flag a binary shift in reasoning inside the Extract $`t \leftarrow \tau.\texttt{ Given checkpointed JSONL outputs, we annotate each trace in four steps: Parse. Extract Cue prefilter (A). Search Material revision check (B). For prefilter hits, query an LLM

judge (GPT–4o) with a rubric that restates (A)+(B) and requests a

strict JSON verdict plus short before/after excerpts around the

first cue. If the verdict is uncertain or invalid, assign FALSE. Record. Write the Boolean label and minimal diagnostics

(markers, first-cue offset, excerpts) back to the record; processing

order is randomized with a fixed seed. The procedure is

idempotent—existing labels are left unchanged. This conservative policy (requiring both an explicit cue and a

substantiated revision, and defaulting to FALSE on uncertainty)

keeps false positives low and yields conservative prevalence estimates. LLM-as-a-Judge — System Prompt (Shift in Reasoning) You

are a careful annotator of single-pass reasoning transcripts. Your task

is to judge whether the writer makes a CLEAR, EXPLICIT "shift in

reasoning" within <think>...</think>. A TRUE label requires BOTH: (A) an explicit cue (e.g., "wait", "hold

on", "scratch that", "contradiction"), AND (B) a material revision of

the earlier idea (reject/correct an initial hypothesis, pick a new

candidate, fix a contradiction, or change device/method). Do NOT mark TRUE for rhetorical transitions, hedging, or generic

connectives without an actual correction. Judge ONLY the content inside

<think>. Be conservative; these events are rare. LLM-as-a-Judge — User Template (filled per example)

Problem/Clue (if available): problem PASS-1 <think> (truncated if long): think Heuristic cue candidates (may be empty): cues

first_marker_pos: pos Return ONLY a compact JSON object with keys: - shift_in_reasoning:

true|false - confidence: "low"|"medium"|"high" - markers_found: string[]

(verbatim lexical cues you relied on) - first_marker_index: integer

(character offset into <think>, -1 if absent) - before_excerpt:

string (<=120 chars ending right before the first marker) -

after_excerpt: string (<=140 chars starting at the first marker) -

explanation_short: string (<=140 chars justification) To bias the LLM-as-a-judge toward explicit reconsideration, we

pre-filter traces using a hand-crafted list of lexical cues. Concretely,

we match case-insensitive regex patterns over the @ l Y @ Category & Representative cues (lemmas/phrases) We reject as insufficient evidence: (i) bare discourse markers without

correction (but, however, therefore, also); (ii) hedges or

meta-verbosity (maybe, perhaps, I think, let’s be careful)

without an explicit pivot; (iii) formatting or notational fixes only;

(iv) device/method names listed without rejecting a prior attempt; and

(v) cues appearing outside The judge must justify that the post-cue span negates or corrects a

prior claim, selects a different candidate, changes the solving

device/method, or resolves a contradiction. We store short

If the judge call fails or returns invalid JSON, we save the prompt to a

local log file, stamp FALSE, and continue. We clamp long We fix a shuffle seed for candidate order, sort files by natural

The whitelist privileges explicit cues and may miss unlexicalized

pivots (false negatives). Conversely, some cues can appear in

non-revisional discourse; the material-revision test mitigates but does

not eliminate such false positives. Because we default to FALSE on

uncertainty, prevalence estimates are conservative. We use GPT–4o as a scalable surrogate for shift annotation and address

known judge biases—position, length, and model-identity—with a

three-part protocol : Order randomization. We randomly permute items and (when

applicable) apply split–merge aggregation to neutralize position

effects . Rubric-anchored scoring. GPT–4o completes a structured JSON

rubric, following G-Eval-style guidance . Prompt-variant stability. We re-query with $`K{=}5`$

judge-prompt variants at judge temperature $`0`$ and report

inter-prompt agreement. Table 7 lists the five judge prompt variants;

Table [tab:judge-reliability-ckpt]

summarizes inter-prompt agreement on a fixed evaluation set. Judge prompt variants v1–v5 used for shift-in-reasoning annotation. For each trajectory we record: (i) graded correctness, (ii)

shift/no-shift label, (iii) whether a shift improved correctness, (iv)

GPT–4o’s confidence (low/med/high), and (v) auxiliary statistics (e.g.,

entropy). This separation supports analyses of shift prevalence versus

shift efficacy. Before judging, we apply a cue-based prefilter

(App. §11.2). Empirically, responses

without cue words almost never contain qualifying shifts (human

annotation of 100 such responses from Qwen-1.5B on

MATH-500 found none). We evaluated Qwen-1.5B (GRPO) on

MATH-500, using five paraphrased judge

prompts (v1–v5), randomized item order, and judge temperature $`0`$.

Table [tab:judge-reliability-ckpt]

reports percent agreement (PO), mean pairwise Cohen’s $`\kappa`$, and

95% bootstrap CIs. Relative to a human majority-vote reference on 20 examples, GPT–4o

achieved Cohen’s $`\kappa=0.794`$ with PO$`=0.900`$. Mean human–human

agreement was lower (PO$`=0.703`$, mean pairwise $`\kappa=0.42`$), and

mean LLM–human agreement was intermediate (PO$`=0.758`$, mean pairwise

$`\kappa=0.51`$).

Table 8 summarizes these

comparisons. Human validation of shift labels. We compare GPT–4o shift judgments

against a human majority-vote reference on a 20-item validation set (PO

= percent agreement). We also report mean pairwise Cohen’s $`\kappa`$

among human annotators and between GPT–4o and individual humans on the

same items. We include the full rubric and sample items from our human annotation

survey in

App. §11.4. We used $`6`$ volunteer adult annotators (unpaid), recruited from the

authors’ academic networks. Participants gave informed consent on the

task page and could withdraw at any time. No sensitive personal

information was requested. This activity consisted solely of judgments about model-generated text

and did not involve collection of sensitive data or interventions with

human participants. Under our institutional guidelines, it does not

constitute human-subjects research; consequently, no IRB review was

sought. Items were shown in randomized order. Annotators saw the original

Question asked and the verbatim Primary label: Yes/No (shift present). Optional fields: confidence

(low/med/high), first cue index (character offset), and a one-sentence

rationale. Edge cases defaulted to No unless a method switch (e.g.,

completing-the-square $`\to`$ factoring; permutations $`\to`$

stars-and-bars; prime factorization $`\to`$ Euclidean algorithm) was

evident. Annotators completed a short calibration set (including Examples A–H)

with immediate feedback. During labeling we interleaved hidden gold

items and monitored time-on-item; submissions failing pre-registered

thresholds were flagged for review. Each item received independent labels. We report Cohen’s $`\kappa`$ with

95% bootstrap CIs. We did not collect sensitive demographics. Released artifacts include

prompts, anonymized traces (with Read the model’s (1) The model clearly switches strategies mid-trace. (2) It abandons

one method after noticing a contradiction, dead end, or mistake, and

adopts a different method. (3) This is a real strategy pivot, not a

small fix. (1) The model keeps using the same method throughout. (2) It only

makes minor arithmetic/algebra fixes. (3) It adds detail or notation

without changing approach. Important: cue words alone (“wait”,

“recheck”, etc.) do not count; look for an actual method switch. Identify the initial method. Look for a pivot: does the model drop

that plan and adopt a different method? Ignore small fixes. Answer

Yes only with a clear pivot; otherwise No. Question. How many sides would there be in a convex polygon if the sum

of all but one of its interior angles is $`1070^\circ`$? Model Correct answer: Yes. Why: Notices a contradiction and switches

approach. Question. Simplify $`3/\sqrt{27}`$. Model Correct answer: No. Why: One method throughout (simplify radical

$`\to`$ rationalize). Question. Solve $`x^{2}-5x-14=0`$. Model Correct answer: Yes. Why: Switch from completing the square to

factoring. Question. Compute

$`\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(\dfrac{x^{2}+3x+2}{x+1}\right)`$. Model Correct answer: No. Why: Stays with quotient rule; no pivot. Question. How many nonnegative integer solutions $`(x,y)`$ satisfy

$`x+y=20`$? Model Correct answer: Yes. Why: Pivot from permutations framing to

stars-and-bars. Question. What is the sum of the first $`50`$ odd integers? Model Correct answer: No. Why: Single recalled formula; no change in

method. Question. Find $`\gcd(252,198)`$. Model Correct answer: Yes. Why: Abandons prime factorization for

Euclidean algorithm. Question. Solve the system $`x+y=10,\; xy=21`$. Model Correct answer: No. Why: One consistent quadratic/Vieta

approach. Annotation Questions, Verbatim. Then, our annotators are asked to

provide Yes/No answers as to whether a shift in reasoning occurred for

the following $`20`$ questions. We have included one sample question

here, to provide an example of the task: Question Asked: If $`a`$ and $`b`$ are positive integers such that

$`\gcd(a,b)=210`$, $`\mathop{\text{lcm}}[a,b]=210^3`$, and $`a Model Response: <think>The greatest common divisor (GCD) of $`a`$

and $`b`$ is given as $`210`$, and their least common multiple (LCM) is

$`210^3`$. This implies that both $`a`$ and $`b`$ share the prime

factors of $`210`$, which are $`2`$, $`3`$, and $`5`$. Let’s express $`a`$ and $`b`$ in terms of their prime factorizations: Given that $`\gcd(a,b) = 210 = 2^1 \cdot 3^1 \cdot 5^1`$, we get the

following equations from comparing exponents: For the GCD: For the LCM: Thus, Since $`\mathop{\text{lcm}}[a,b] = 210^3`$, substituting the values

gives us: This simplifies our expressions for $`w`$, $`v`$, and $`t`$ to: Therefore, the only combination satisfying these conditions is: Substituting back into the expression for $`a`$ yields: However, since $`a < b`$, this alone does not provide any new

information because $`a = b`$. To find all pairs $`(a, b)`$ where $`a < b`$ and $`\gcd(a, b) = 210`$: -

We need to consider all combinations of $`a`$ and $`b`$ such that: Considering $`x > x'`$, $`y > y'`$, and $`z > z'`$: - For $`x > x'`$: Since $`x`$ cannot be greater than 1 (as $`a`$ must

be less than $`b`$), the only possibility is $`x' = 0`$ (i.e., $`a`$ can

take on any power of 2 except 0, making $`a = 210k`$ where $`k`$ is some

integer). - Similarly, considering $`y > y'`$ and $`z > z'`$, the same logic

applies for powers of 3 and 5 respectively. Thus, $`a`$ could be $`210 \cdot 3^m \cdot 5^n`$ for various

combinations of $`m`$ and $`n`$. Each choice of $`m`$ and $`n`$ uniquely determines $`a`$, resulting in

infinitely many possible values of $`a`$ because there are infinitely

many integers $`m`$ and $`n`$.</think> Fill-in-the-bubble response. Choices: Yes / No (no alternative /

third choice was provided). LLM-as-a-Judge assessed answer. “Yes”. Post-assessment, we reveal the LLM-as-a-Judge answer to participants and

encourage them to invite others to participate. Each individual’s score

was weighted equally, and we analyzed annotator agreement as described

in 11.3. The complete assessment

is made available as part of our codebase. This appendix collects supplementary analyses that extend and

stress-test the main results. We first report the prevalence of formal

“Aha!” events under threshold grids and summarize cross-domain patterns

(App. §12.1). We then

replicate key regressions and uncertainty analyses on larger model

families (Qwen2.5–7B and Llama 3.1–8B) to verify that the shift effects

generalize beyond Qwen2.5–1.5B

(App. §12.3). Next, we test whether

entropy-gated, extrinsically triggered reconsideration is robust to

the specific cue wording

(App. §12.4). Finally, we

evaluate external models (DeepSeekR1 and GPT4o) under the same

shift-detection protocol and compare alternative shift detectors

(App. §12.5 and

App. §12.6). Together, these

checks show that our qualitative conclusions are stable across domains,

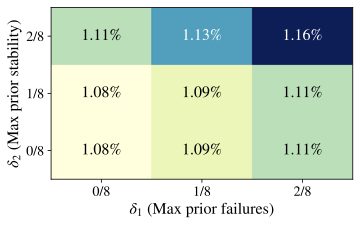

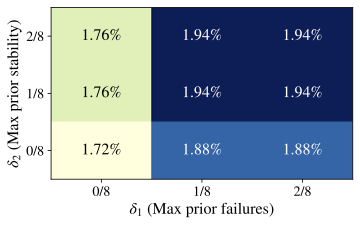

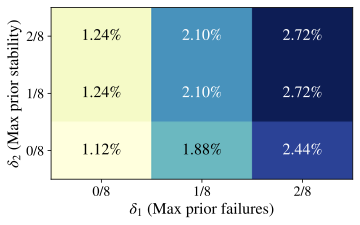

model families/sizes, prompt variants, and detector choices. Each panel reports the share of problem–checkpoint pairs $`(q_j,k)`$

that satisfy our operational definition of an “Aha!” moment

(Def. 1) under a grid of thresholds:

$`\delta_1\!\in\!\{0,\tfrac{1}{8},\tfrac{2}{8}\}`$ (maximum prior

accuracy), $`\delta_2\!\in\!\{0,\tfrac{1}{8},\tfrac{2}{8}\}`$ (maximum

prior shift rate), and, unless noted, $`\delta_3=\epsilon>0`$ (any

non-zero gain at $`k`$). Cells show the percentage and the raw counts

$`(\#\text{events}/\#\text{pairs})`$. We aggregate over checkpoints

$`\leq\!1000`$ with $`G{=}8`$ samples per item, and we use the

conservative detector described in

App. 11.2 (lexical cue and material

revision; default to FALSE on uncertainty). Three robust trends emerge across Xword, Math, and RHour and

across model families/sizes. Rarity. Even under the lenient gain criterion

$`\delta_3\!=\!\epsilon`$, “Aha!” events occupy a very small fraction

of problem–checkpoint pairs. Most cells are near zero; none approach a

large fraction. This mirrors the main-text finding that mid-trace

shifts seldom coincide with measurable improvements. Sensitivity to prior instability and prior accuracy. Relaxing

either prerequisite increases counts but remains small in magnitude.

In particular, moving to higher $`\delta_2`$ (allowing more prior

shifts, i.e., lower prior stability) and higher $`\delta_1`$ (allowing

occasional prior solves) produces the visually “warmest’’

cells—consistent with the intuition that “Aha!” detections concentrate

where traces have shown some volatility and the item is not maximally

hard. Domain/model differences. RHour exhibits a higher raw shift

rate (App. §6.2), but the “Aha!” filter

(requiring a gain at $`k`$) prunes most cases; the absolute prevalence

remains low. Xword shows small pockets of higher prevalence when

$`\delta_1,\delta_2\!\geq\!\tfrac{1}{8}`$, whereas Math is uniformly

sparse. Scaling from Qwen 1.5B to 7B or switching to Llama 3.1–8B does

not materially increase prevalence. Replacing $`\delta_3{=}\epsilon`$ with a minimal absolute lift (e.g., at

least one of the $`G{=}8`$ samples flips from incorrect to correct at

$`k`$) further reduces counts but preserves the qualitative ordering

across domains and models. Across all settings, formal “Aha!” moments—requiring both a mid-trace

reasoning pivot and a contemporaneous performance gain—are vanishingly

uncommon. The sparse, threshold-stable patterns in

Figs. 16–17 show this

finding across temperatures, domains, and models. To make our threshold-selection procedure concrete, we ran the

grid/bootstrapped threshold search across the stored Qwen2.5–1.5B

evaluation outputs for each domain and temperature. For each domain$`\times`$temperature root, we searched a small grid

$`\delta_1,\delta_2\in\{0,1/8,2/8\}`$ and

$`\delta_3\in\{\text{None},0,0.05,0.125\}`$ (with Across these stored outputs, the selected thresholds yield extremely low

event prevalence, and gains are generally small, unstable, or negative.

In particular, for Math at $`T\in\{0.05,0.3\}`$ the best available

configurations (under this search) have negative bootstrap lower

bounds, indicating no robust evidence that shifted traces outperform the

baseline on the flagged pairs. We extend the main-text analysis to probe the role of model family and

size. Replicating the raw-effect analyses for Qwen2.5–7B and

Llama 3.1–8B on Math, we observe the

same qualitative pattern reported for Qwen2.5–1.5B: mid-trace

reasoning shifts are consistently detrimental across training steps and

remain negative across decoding temperatures (magnitudes vary, not the

sign), matching

Fig. 15 and

Table 9. We begin by checking whether the core RQ1 finding about rarity

generalizes across model family and size. Using the same formal detector

(Def. 1) and threshold grid as in the

main text, we compute the fraction of problem–checkpoint pairs that

qualify as “Aha!” events.

Fig. 12 shows that these

events remain extremely sparse for both Qwen2.5–7B and Llama 3.1–8B

(Math, $`T{=}0.7`$). We then repeat the regression analysis from

Table 3 for these models.

Figure 15 visualizes the raw

effect across training steps and decoding temperatures. This appendix extends the main-text uncertainty analysis to larger model

families on Math, using traces from

Qwen2.5–7B and Llama 3.1–8B. Our goal is to test a simple

hypothesis: if reasoning shifts are primarily an uncertainty response,

then shifts should become more likely as uncertainty rises. We

operationalize uncertainty using each trace’s sequence-level entropy

and use the same GPT-derived binary shift indicator as in the main text. For each decoding temperature $`T`$, we regress the shift indicator on

standardized sequence entropy with problem fixed effects and

cluster-robust standard errors clustered by problem: Across both model families, we again find a non-positive association

between entropy and shift prevalence. In particular, at $`T{=}0.05`$ and

$`T{=}0.7`$, a 1 SD increase in entropy significantly reduces the odds

of a detected shift (OR$`_{1\sigma}{=}0.63`$, $`p{=}0.001294`$;

OR$`_{1\sigma}{=}0.67`$, $`p{=}0.002396`$), while the estimates at

$`T{=}0`$ and $`T{=}0.3`$ are not distinguishable from zero. This

mirrors the smaller Qwen2.5–1.5B Math

models: shifts are not more common in high-entropy regimes, and when a

dependence is detectable, it points in the opposite direction. To complement the prevalence analysis,

Table 10 stratifies the

raw shift effect on correctness by entropy (high = top 20%, low =

bottom 80%), pooling temperatures and restricting to early training

steps (steps $`\le\!450`$). The qualitative picture is consistent across

strata: shifts are associated with lower accuracy even within the

high-entropy slice. Finally,

Table 11 reports paired

sample-level results for triggered reconsideration (Pass 2). This

manipulation differs from spontaneous shifts: it explicitly prompts the

model to re-evaluate. On Math, forced

reconsideration yields a positive gain for Qwen2.5–7B ($`+5.97`$pp)

but a negative gain for Llama 3.1–8B ($`-4.19`$pp) in this

evaluation slice. We tested only on a subset given the high compute

cost. Forced “Aha” (triggered reconsideration), sample-level results on

Math. $`\hat p_{\text{P1}}`$ and

$`\hat p_{\text{P2}}`$ are accuracies in baseline vs. forced pass;

$`\Delta`$ is the percentage-point gain; “wins” count paired samples

where one pass is correct and the other is not. To test whether the effect of artificially triggered reflection depends

on the specific reconsideration cue used, we evaluate three semantically

similar but lexically distinct prompts: C1: “Hold on, this reasoning might be wrong. Let’s go back and

check each step carefully.” C2: “Actually, this approach doesn’t look correct. Let’s restart

and work through the solution more systematically.” C3: “Wait, something is not right; we need to reconsider. Let’s

think this through step by step.” For each cue, we re-run $`8\times 500`$ Math problems (Qwen2.5–1.5B,

final checkpoint) with 1-shot decoding at $`T{=}0.1`$, obtaining $`500`$

paired baseline and cued completions per cue. We then fit a logistic

regression for each cue, controlling for baseline correctness and

problem identity.8 Across all cues, higher entropy is strongly associated with improved

post-intervention accuracy.

Table 12 reports standardized entropy

coefficients, unit odds ratios (raw entropy), and odds ratios for a 1 SD

increase in entropy. Entropy-gated improvement under three reconsideration cues.

$`\beta`$ is the coefficient on standardized entropy from a logistic

regression controlling for baseline correctness and problem fixed

effects; brackets give 95% CIs. OR is the unit odds ratio (raw entropy),

and OR$`_{1\sigma}`$ is the odds ratio for a $`1`$ SD increase in

entropy. All three cues show the same qualitative pattern: a one–standard

deviation increase in entropy substantially increases the odds of

correctness after the reconsideration cue (2.2$`\times`$–2.5$`\times`$

across cues). C2 yields the strongest effect, but the differences are

modest, indicating that the intervention’s success is tied to

uncertainty rather than to any particular lexical phrasing. To verify that our findings are not an artifact of the GRPO-tuned models

studied in the main paper, we evaluate two widely discussed reasoning

models—DeepSeekR1 and GPT4o—under our shift-detection protocol. These

models have been cited as exhibiting frequent “Aha!” moments or dramatic

mid-trace realizations , making them a natural stress test for our

methodology. We evaluate both models on the full MATH

benchmark with: 1-shot decoding, temperatures $`T\in\{0, 0.05\}`$, identical prompting format (with no system-level alterations or heuristics. Each model generates exactly one chain-of-thought sample per problem,

yielding $`N{=}500`$ traces per model per temperature. We use the same annotation protocol as in

§5.2 and

App. 11.2: Cue prefilter: at least one explicit lexical cue of

reconsideration (e.g., “wait”, “actually”, “hold on”), using the

whitelist in

Table [tab:shift-cue-whitelist]. Material revision: GPT4o judges whether the post-cue reasoning

constitutes a genuine plan pivot (rejecting a candidate, switching

method, resolving a contradiction), returning a strict JSON verdict. Cases lacking either (A) lexical cue or (B) structural revision are

labeled as no shift. Table [tab:external-models] shows

shift prevalence and conditional accuracy by decoding temperature. Both

models exhibit low canonical shift base rates under our definition.

For GPT4o, conditional accuracy given a shift is not reliably higher

than the non-shift baseline: at $`T{=}0.05`$, shifted traces are

substantially less accurate ($`P(\checkmark\mid S{=}1)=0.18`$

vs. $`P(\checkmark\mid S{=}0)=0.724`$), and at $`T{=}0`$ shifted traces

are also lower ($`0.60`$ vs. $`0.724`$). For DeepSeekR1, the number of

shifted traces is extremely small (2–3 traces), so conditional

comparisons are unstable. These results reinforce two conclusions: Low base rate of canonical shifts. Even high-capability

reasoning models produce criteria-satisfying mid-trace pivots only

rarely. Canonical shifts do not reliably improve accuracy. Conditional

accuracy given a shift is unstable across temperatures and does not

show a consistent benefit. We release the full set of model outputs and shift annotations used in

this analysis on Hugging Face; see

Table 13. Released external-model outputs. Hugging Face datasets containing

1-shot MATH-500 traces used in

App. §12.5, for $`T\in\{0,0.05\}`$. Prior work shows that superficial linguistic markers of hesitation—such

as “wait,” “hold on,” or “actually”—are unreliable indicators of genuine

cognitive shifts. Keyword-based detectors misclassify such cues at high

rates, often interpreting hedges or verbosity as insight-like events .

Recent analyses of “Aha!”-style behavior in LLMs similarly report that

many mid-trace cues reflect shallow self-correction or filler language

rather than substantive plan changes . In parallel, LLM-as-a-judge evaluations are known to exhibit position,

ordering, and verbosity biases unless structured and controlled .