QSLM A Performance- and Memory-aware Quantization Framework with Tiered Search Strategy for Spike-driven Language Models

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: QSLM A Performance- and Memory-aware Quantization Framework with Tiered Search Strategy for Spike-driven Language Models- ArXiv ID: 2601.00679

- Date: 2026-01-02

- Authors: Rachmad Vidya Wicaksana Putra, Pasindu Wickramasinghe, Muhammad Shafique

📝 Abstract

Large Language Models (LLMs) have been emerging as prominent AI models for solving many natural language tasks due to their high performance (e.g., accuracy) and capabilities in generating high-quality responses to the given inputs. However, their large computational cost, huge memory footprints, and high processing power/energy make it challenging for their embedded deployments. Amid several tinyLLMs, recent works have proposed spike-driven language models (SLMs) for significantly reducing the processing power/energy of LLMs. However, their memory footprints still remain too large for low-cost and resource-constrained embedded devices. Manual quantization approach may effectively compress SLM memory footprints, but it requires a huge design time and compute power to find the quantization setting for each network, hence making this approach not-scalable for handling different networks, performance requirements, and memory budgets. To bridge this gap, we propose QSLM, a novel framework that performs automated quantization for compressing pre-trained SLMs, while meeting the performance and memory constraints. To achieve this, QSLM first identifies the hierarchy of the given network architecture and the sensitivity of network layers under quantization, then employs a tiered quantization strategy (e.g., global-, block-, and module-level quantization) while leveraging a multi-objective performance-and-memory trade-off function to select the final quantization setting. Experimental results indicate that our QSLM reduces memory footprint by up to 86.5%, reduces power consumption by up to 20%, maintains high performance across different tasks (i.e., by up to 84.4% accuracy of sentiment classification on the SST-2 dataset and perplexity score of 23.2 for text generation on the WikiText-2 dataset) close to the original non-quantized model while meeting the performance and memory constraints.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **Introduction to the QSLM Framework**: - The QSLM framework automates the quantization process for large spike-driven language models (SLMs) to meet specific performance and memory constraints, making these models more suitable for embedded systems. - **Analogy**: Think of QSLM as a tailor who can adjust your suit perfectly to fit you without needing to remake it from scratch.-

Network Analysis and Quantization Search Strategy:

- The framework analyzes the network structure and sensitivity of each block under quantization, then automatically searches for optimal settings at different levels.

- Analogy: Imagine sorting through a vast library but with a smart assistant who knows exactly which books to pick based on your interests.

-

Final Quantization Setting Selection:

- QSLM selects the best quantization setting that balances performance and memory usage effectively.

- Analogy: It’s like choosing the right recipe for cooking, where you balance taste (performance) with available ingredients (memory).

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

Large Language Models (LLMs), Spike-driven Language Models (SLMs), Quantization, Memory Footprint, Embedded Systems, Design Automation.

Introduction

Transformer-based networks have achieved state-of-the-art performance (e.g., accuracy) in diverse machine learning (ML)-based applications, including solving diverse natural language tasks . In recent years, transformer-based large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated significant improvements in extending the capabilities of natural language models , thereby making it possible to produce high-quality language-based understanding and responses to the given inputs. Therefore, their adoption in resource-constrained embedded devices is highly in demand and actively being pursued for enabling customized and personalized systems . However, their large compute costs, huge memory footprints, and high processing power/energy make it challenging for their embedded deployments.

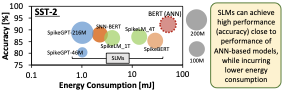

In the other domain, the advancements of spiking neural networks (SNNs) have demonstrated promising power/energy-efficient alternative to artificial neural network (ANN) algorithms, because of their sparse spike-driven operations . Therefore, recent works leveraged spike-driven operations for LLMs to reduce the processing power/energy requirements, i.e., so-called Spike-driven Language Models (SLMs); see Fig. 1. However, their memory footprints are still too large for embedded deployments. To reduce memory footprints of spike-driven models, quantization is one of the prominent methods , because it can effectively reduce memory footprints with slightly yet acceptable accuracy degradation. However, manually determining an appropriate quantization setting for any given SLM requires huge design time and large power/energy consumption. Therefore, this approach is laborious and not scalable for compressing different SLMs for different possible performance and memory constraints. Moreover, existing ANN quantization frameworks cannot be employed directly for SLMs due to the fundamental differences in synaptic and neuronal operations between ANNs and SNNs.

Such conditions lead us to the research problem targeted in this paper, i.e., how can we efficiently quantize any given pre-trained SLM, while maintaining high performance (e.g., accuracy) and meeting the memory constraint? A solution to this problem may advance the design automation for efficient embedded implementation of SLMs.

/>

/>

State-of-the-art of SLMs and Their Limitations

SLM development is a relatively new research avenue, hence the state-of-the-art works still focus on achieving high performance (e.g., accuracy), such as SpikeBERT , SpikingBERT , SNN-BERT , SpikeLM , SpikeLLM , and SpikeGPT . Specifically, spike-driven BERTs leverage BERT networks from ANN domain and apply spiking neuronal dynamics on them, while employing different techniques, such as knowledge distillation and input coding enhancements . SpikeLM and SpikeLLM target to scale up spiking neuronal dynamics to large models (e.g., up to 70 billions of weight parameters for SpikeLLM). Meanwhile, SpikeGPT targets at reducing the computational complexity in SLMs by replacing the spike-driven transformer modules with the spike-driven receptance weighted key value (SRWKV) modules, while maintaining the high performance. These state-of-the-art highlight that the efforts for quantizing SLMs have not been comprehensively explored.

A Case Study and Associated Research Challenges

/>

/>

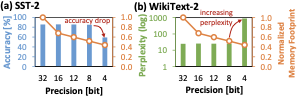

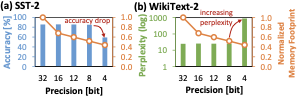

To show the potentials and challenges in quantizing SLMs, we perform an experimental case study. Here, we apply uniform quantization on the weight parameters of the pre-trained SpikeGPT-216M with the same precision level across its attention blocks, then employ the quantized model for solving the sentiment analysis on the SST-2 dataset and evaluating the perplexity on the WikiText-2 dataset . Further details of experiments are provided in Sec. 4, and the experimental results are presented in Fig. 2. These results show that, the post-training quantization (PTQ) scheme leads to significant memory reduction, while preserving high performance (e.g., accuracy and perplexity) when employed with appropriate quantization. Otherwise, it leads to notable performance degradation.

Furthermore, these observations also expose several research challenges, as follows.

-

Quantization process should handle different network complexity levels (e.g., number of layers) efficiently.

-

Quantization process should be able to meet different possible performance (e.g., accuracy) and memory constraints, thus making it practical for diverse applications.

-

Quantization process should minimize manual intervention to increase its scalability for handling different networks, performance requirements, and memory budgets.

Our Novel Contributions

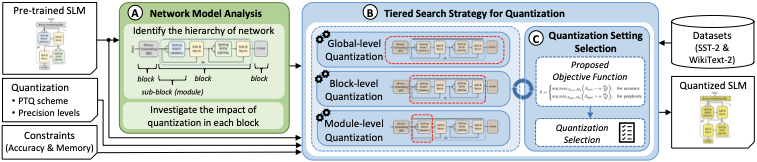

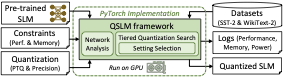

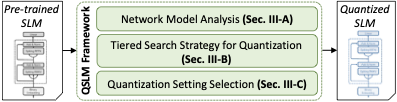

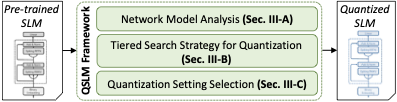

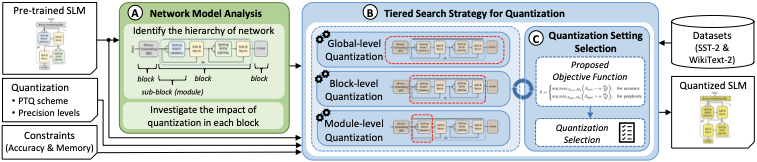

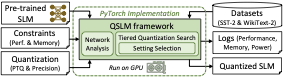

To address the targeted problem and research challenges, we propose QSLM, a novel framework that performs automated Quantization for compressing pre-trained Spike-driven Language Model (SLM) to meet the performance (e.g., accuracy) and memory constraints. To achieve this, QSLM performs the following key steps; see an overview in Fig. 3.

-

Network Model Analysis (Sec. 3.1): It aims to identify the structure of the given pre-trained model, determine the network hierarchy to be considered for quantization search, and investigate the sensitivity of each block of the network under quantization on the performance (e.g., accuracy).

-

Tiered Search Strategy for Quantization (Sec. 3.2): It aims to perform automated quantization and evaluation for the model candidates under different phases (e.g., global-, block-, and module-level quantization, subsequently) based on the network hierarchy and the sensitivity analysis, while considering the performance and memory constraints.

-

Quantization Setting Selection (Sec. 3.3): It selects the final quantization setting from the candidates by leveraging our trade-off function that quantifies the candidates’ benefits based on their performance and memory footprint.

Key Results: We implement the QSLM framework using PyTorch and then run it on the Nvidia RTX A6000 multi-GPU machine. Experimental results show that QSLM provides effective quantization settings for SLMs. It saves by up to 86.5% of memory footprint, reduces by up to 20% of power consumption, and maintain high performance across different tasks (i.e., by up to 84.4% accuracy of sentiment classification on the SST-2 and 23.2 perplexity score of text generation on the WikiText-2) close to the non-quantized model, while meeting the performance and memory constraints. These results show the potential of QSLM framework for enabling embedded implementation of SLMs.

/>

/>

Background

SNNs: An SNN model design typically encompasses spiking neurons, network architecture, neural/spike coding, and learning rule . Recent SNN developments in software and hardware have advanced the practicality of SNNs for diverse ultra-low power/energy application use-cases.

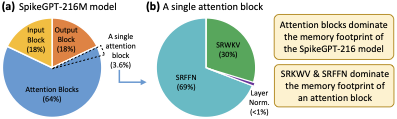

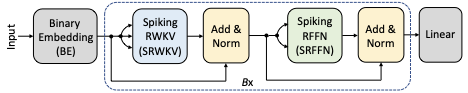

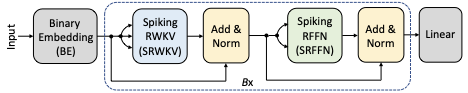

SLMs: Recently, several state-of-the-art SLMs have been proposed in the literature, such as SpikeBERT , SpikingBERT , SNN-BERT , SpikeLM , SpikeLLM , and SpikeGPT . In this work, we consider SpikeGPT as the potential model candidate for embedded systems since it offers competitive performance with the lowest energy consumption due to its reduced computational complexity; see Fig. 1. Specifically, SpikeGPT replaces traditional self-attention mechanism with Spiking Receptance Weighted Key Value (SRWKV) and Spiking Receptance Feed-Forward Networks (SRFFN).

/>

/>

/>

/>

SRWKV leverages element-wise products rather than matrix-matrix multiplication, hence reducing the computational cost of the attention mechanism. Meanwhile, SRFFN is employed to replace the conventional feed-forward network (FFN) with a spiking-compatible version. Its network architecture is illustrated in Fig. 4 and summarized in Table 13. If the data have been processed through all network layers, the model either employs a classification head for natural language understanding (NLU) or a generation head for natural language generation (NLG).

| Block |

|

|

Quantity |

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input |

|

|

1 |

|

||||||||

| Attention |

|

|

18 |

|

||||||||

| Output |

|

|

1 |

|

SNN Quantization

There are two possible schemes for quantizing SNN models, namely Quantization-aware Training (QAT) and Post-Training Quantization (PTQ) . QAT quantizes an SNN model during the training phase based on the given precision level. Meanwhile, PTQ quantizes the pre-trained SNN model with the given precision level. In this work, we consider the PTQ scheme since it avoids the expensive training costs, such as the computational time, memory, and power/energy consumption . To realize this, we employ the simulated quantization approach to enable fast design space exploration and provide representative results in performance (e.g., accuracy) and power/energy consumption saving .

The QSLM Framework

We propose the novel QSLM framework to solve the targeted problem and related challenges, whose overview is presented in Fig. 5. It employs network model analysis to identify the model structure and identify its block sensitivity under quantization, tiered search strategy to systematically perform quantization on the model, and quantization setting selection that considers performance and memory constraints. Details of its key steps are discussed in the following sub-sections.

Network Model Analysis

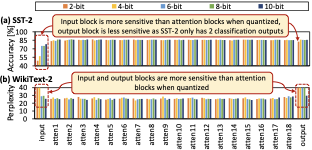

To perform effective quantization, it is important to apply appropriate precision levels on the weight parameters of the model. Therefore, this step targets to understand the network structure of the model, identify its architectural hierarchy for quantization search, and investigate its block sensitivity under quantization on the performance, through the following ideas.

-

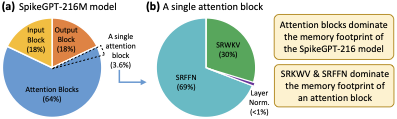

We identify blocks in the network model that can be quantized. Typically, they are categorized as the input, attention, and output blocks.

-

For each block, we identify the sub-blocks (modules) and the respective number of weights to estimate the memory saving potentials; see Table 13 and Fig. 6 for SpikeGPT-216M.

-

Then, we investigate the block sensitivity under quantization by applying different precision levels to individual block and evaluating the performance (e.g., accuracy). It is useful for devising a suitable strategy for quantization search.

/>

/>

/>

/>

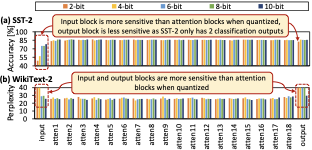

For instance, we conduct experiments that apply different weight precision levels on each block of the SpikeGPT-216M for sentiment analysis on the SST-2 and text generation on the WikiText-2. Experimental results are presented in Fig. 7, from which we make the following key observations.

-

The input and output blocks are more sensitive than the attention blocks, since the loss of information from quantization in these blocks lead to notable performance degradation. Therefore, the input and output blocks should be carefully quantized to maximize memory reduction while ensuring high performance (e.g., accuracy).

-

The attention blocks are less sensitive than the input/output block. Considering that the attention blocks dominate the memory footprint, quantizing them potentially lead to significant memory reduction. Therefore, quantizing the attention blocks is beneficial to achieve significant memory reduction.

These observations are then leveraged in Sec. 3.2 to enable automated quantization process.

(1) Pre-trained model ($`Net`$), its performance ($`P`$) and memory

footprint ($`M`$); (2) Pre-defined bit precision levels $`b`$:

$`b\in`$ $`\{16, 14, 12, ... 4\}`$, and its number of precision levels

($`N_b`$); (3) Number of blocks in the model ($`N_k`$); (4)

Number of modules in the attention block ($`N_m`$); (5) Constraints:

performance constraint ($`const_A`$), and memory constraint

($`const_M`$); Quantized model ($`Net_q`$);

BEGIN

Initialization:

$`c`$ = 0; $`candQ[c,:,:]`$ = 32;

$`P`$, $`M`$ = test($`Net`$, $`candQ[c,:,:]`$);

$`cStat[c].perf`$ = $`P`$;

$`cStat[c].mem`$ = $`M`$;

Process:

// Global-level quantization $`c`$ = $`c`$+1; $`candQ[c,:,:]`$ =

$`b[i]`$; $`Net_{t}`$ = quantize($`Net`$, $`candQ[c,:,:]`$);

$`cStat[c]`$, $`X`$ = eval($`Net_{t}`$, $`P`$, $`M`$, $`const_A`$,

$`const_M`$); //

Alg. [Alg_Eval] $`cStat[c].met`$ =

‘true’; $`I_{last}`$ = $`i`$; $`cStat[c].met`$ = ‘false’; $`I_{tmp}`$ =

$`I_{last}`$;

// Block-level quantization $`c`$ = $`c`$+1; $`candQ[c,k,:]`$ = $`b[i]`$; $`Net_{t}`$ = quantize($`Net`$, $`candQ[c,:,:]`$); $`cStat[c]`$, $`X`$ = eval($`Net_{t}`$, $`P`$, $`M`$, $`const_A`$, $`const_M`$); // Alg. [Alg_Eval] $`cStat[c].met`$ = ‘true’; $`I_{last2}[k]`$ = $`i`$; $`cStat[c].met`$ = ‘false’; $`I_{tmp2}[k]`$ = $`I_{last2}[k]`$;

// Module-level quantization $`c`$ = $`c`$+1; $`candQ[c,k,m]`$ =

$`b[i]`$; $`Net_{t}`$ = quantize($`Net`$, $`candQ[c,:,:]`$);

$`cStat[c]`$, $`X`$ = eval($`Net_{t}`$, $`P`$, $`M`$, $`const_A`$,

$`const_M`$); //

Alg. [Alg_Eval] $`cStat[c].score`$ =

$`S_{tmp}`$; $`cStat[c].met`$ = ‘true’; $`I_{last3}[k,m]`$ = $`i`$;

$`cStat[c].met`$ = ‘false’; $`cand_{fin}`$ = select($`candQ`$,

max($`cStat[:].score`$), $`cStat[:].met`$);

$`Net_q`$ = quantize($`Net`$, $`cand_{fin}`$); return $`Net_q`$;

END

(1) Performance ($`P`$) and memory footprint ($`M`$) of the original

non-quantized model; (2) Input model ($`Net_{tmp}`$); (3)

Constraints: performance (i.e., accuracy/perplexity) constraint

($`const_A`$), and memory constraint ($`const_M`$); (4) Candidate

index ($`c`$); (1) Characteristics of the model candidates

($`cStat`$); (2) Status if constraints are met ($`X`$:

‘true’/‘false’);

BEGIN

Process:

$`P_{tmp}`$, $`M_{tmp}`$ = test($`Net_{tmp}`$); $`S_{tmp}`$ =

calc_score($`P_{tmp}`$, $`M_{tmp}`$); //

Eq. [Eq_Score] $`X`$ = check($`P`$,

$`M`$, $`const_P`$, $`const_M`$, $`P_{tmp}`$, $`M_{tmp}`$);

$`cStat[c].perf`$ = $`P_{tmp}`$; $`cStat[c].mem`$ = $`M_{tmp}`$;

$`cStat[c].score`$ = $`S_{tmp}`$; return $`cStat`$, $`X`$;

END

Tiered Search Strategy for Quantization

This step aims to enable an automated quantization process to maximize the memory reduction, while meeting both performance constraint ($`const_A`$) and memory constraint ($`const_M`$). To obtain this, we propose a tiered search strategy that applies a certain bit precision level ($`b`$) to the targeted weights from the highest-level network hierarchy to the lowest one (e.g., global-level, block-level, and module-level quantization, subsequently). Its key steps are described below (pseudocode in Alg. [Alg_QuantSearch] and [Alg_Eval]).

-

Global-level quantization: We uniformly quantize all blocks in the model based on the pre-defined list of precision levels ($`b`$), such as $`b\in`$ $`\{16, 14, 12, ..., 4\}`$. Here, we orderly apply $`b`$ value from the largest to the smallest ones, while evaluating if the quantized model meets both $`const_{A}`$ and $`const_{M}`$.

-

If both constraints are met, then the investigated precision level $`b`$ is recorded as the quantization candidate ($`candQ`$).

-

If both constraints are not met, then the selected precision is set back to the last acceptable precision (from index-$`I_{last}`$ of list $`b`$). Then, we move to block-level quantization.

-

-

Block-level quantization: We quantize each block in the model with lower precision than the previously applied one in the global-level step. Then, we subsequently apply lower precision based on the list $`b`$, while performing evaluation.

-

If both constraints are met, then the investigated precision level $`b`$ is recorded as the setting for the respective block, and used to update the candidate $`candQ`$.

-

If both constraints are not met, then the selected precision for the respective block is set back to the last acceptable precision level (from index-$`I_{last2}`$ of list $`b`$). Afterward, we move to module-level quantization.

-

-

Module-level quantization: We quantize each module in the attention blocks with lower precision than the previously applied one in the block-level step. We further apply lower precision based on the list $`b`$, while performing evaluation.

-

If both constraints are met, then the investigated precision level $`b`$ is recorded as the quantization setting for the respective module, and used to update the candidate $`candQ`$.

-

If both constraints are not met, then the precision level $`b`$ for the respective module is set back to the last acceptable precision level (from index-$`I_{last3}`$ of list $`b`$).

-

Quantization Setting Selection

The tiered search strategy may obtain multiple quantization candidates

that meet $`const_A`$ and $`const_M`$. To select the most appropriate

solution, we quantify the benefit of the candidates considering their

performance (e.g., accuracy) and memory saving, and then select the one

with the highest score ($`S`$). To do this, we propose a

performance-and-memory trade-off function, that can be expressed as

Eq. [Eq_Score]. Here, $`A_{acc}`$ denotes

accuracy for classification task and $`A_{ppx}`$ denotes perplexity for

generation task; $`M`$ and $`M_q`$ denote memory footprints for the

original non-quantized model and quantized model, respectively; and

$`\alpha`$ denotes the user-defined adjustment factor. In the

classification task, it aims to maximize the score $`S`$, that is

proportional to the accuracy, since higher accuracy is better. In the

generation task, it aims to minimize the score $`S`$, since lower

perplexity is better. A candidate with larger memory than other

candidates will penalize more the score $`S`$. Furthermore, perplexity

score $`A_{ppx}`$ can be calculated using

Eq. [Eq_Perplexity], with $`N_T`$ is the

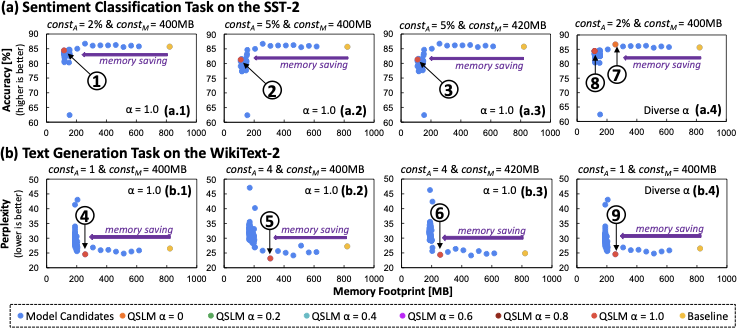

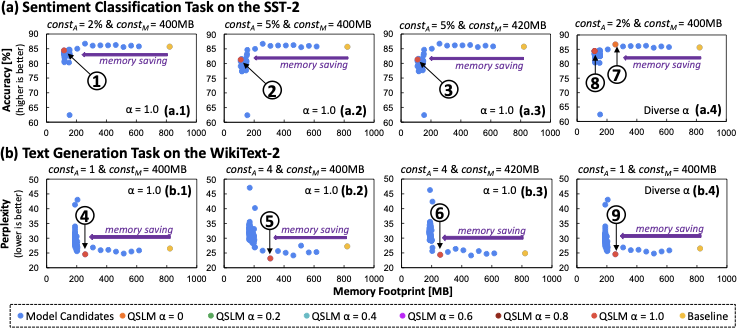

number of words (tokens) in the sequence, and $`P(w_i \mid w_{ To evaluate the QSLM framework, we develop its PyTorch-based

implementation, then run it on the Nvidia RTX A6000 multi-GPU machine;

see Fig. 8. For the baseline non-quantized

model we consider the state-of-the-art pre-trained SpikeGPT-216M that

has been trained with 5B tokens from the OpenWebText dataset . We use

its publicly available pre-trained model and codes from the original

authors, and then reproduce the fine-tuning and testing phases with

their default hyperparameter settings on targeted tasks. In the

evaluation, we consider the following tasks: (1) a sentiment

classification task on the SST-2 dataset , and (2) a text generation

task on the WikiText-2 dataset . Under the baseline settings, we achieve

accuracy of 85.7% for the sentiment classification task, and perplexity

score of 26.5 for the text generation task. Here, we consider different

sets of constraints to investigate the performance of QSLM under

different constraint cases. In sentiment classification task, case-a1: $`const_A`$ = 2% and

$`const_M`$ = 400MB; case-a2: $`const_A`$ = 5% and $`const_M`$ =

400MB; and case-a3: $`const_A`$ = 5% and $`const_M`$ = 420MB. In text generation task, case-b1: $`const_A`$ = 1 and $`const_M`$ =

400MB; case-b2: $`const_A`$ = 4 and $`const_M`$ = 400MB; and case-b3:

$`const_A`$ = 4 and $`const_M`$ = 420MB. Note, $`const_A`$ denotes the maximum acceptable accuracy degradation or

perplexity increase, while $`const_M`$ denotes the maximum acceptable

memory footprint. Furthermore, we also perform ablation study for

investigating the impact of different $`\alpha`$ values with $`\alpha`$

$`\in`$ $`\{0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1\}`$. The experiments evaluate

several metrics, such as accuracy for sentiment classification task,

perplexity score for text generation task, memory footprint, and power

consumption (using nvidia-smi utility). Experimental results for sentiment classification task are provided in

Fig. 9(a). These results show that, QSLM

effectively reduces memory footprint of the baseline model across

different scenarios (i.e., different sets of constraints and different

$`\alpha`$ values), while meeting both accuracy and memory constraints.

Our key observations are the following. For case-a1 in Fig. 9(a.1): QSLM achieves 84.4% accuracy

and reduces 85.7% memory footprint; see . For case-a2 in Fig. 9(a.2): QSLM achieves 81.3% accuracy

and reduces 86.5% memory footprint; see . For case-a3 in Fig. 9(a.3): QSLM achieves 81.3% accuracy

and reduces 86.5% memory footprint; see . Meanwhile, experimental results for text generation task are provided in

Fig. 9(b). These results also show that,

QSLM effectively reduces memory footprint of the baseline model across

different scenarios (i.e., different sets of constraints and different

$`\alpha`$ values), while meeting both perplexity and memory

constraints. Our key observations are the following. For case-b1 in Fig. 9(b.1): QSLM achieves 24.6 perplexity

score and reduces 68.7% memory footprint; see . For case-b2 in Fig. 9(b.2): QSLM achieves 23.2 perplexity

score and reduces 62.4% memory footprint; see . For case-b3 in Fig. 9(b.3): QSLM achieves 24.4 perplexity

score and reduces 68.7% memory footprint; see . These significant memory savings while preserving high accuracy or low

perplexity can be obtained due to the systematic quantization approach

in our QSLM framework. Specifically, QSLM leverages the block

sensitivity information from model analysis to guide the quantization

search, then performs tiered search strategy to carefully apply

different precision levels on different network blocks/modules, while

ensuring the selected model candidates always meet the given constraints

(i.e., $`const_A`$ and $`const_M`$) by leveraging a

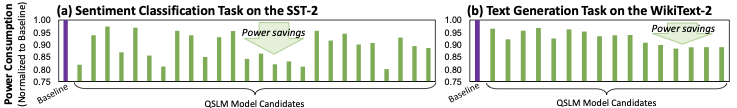

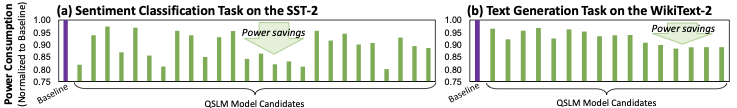

performance-and-memory trade-off function and the given constraints. Experimental results for power consumption of the baseline model and the

QSLM model candidates that meet both performance and memory constraints

are provided in

Fig. 10. For the sentiment

classification task, QSLM model candidates can reduce the power

consumption by 2.6%-20%. Meanwhile, for the text generation task, QSLM

model candidates can reduce the power consumption by 3.2%-11.6%. These

power savings come from the reduction of precision levels in the weight

parameters of the quantized models, thereby incurring lower

computational and memory power to complete the processing, as compared

to the baseline non-quantized model. Furthermore, these results also

demonstrate that, QSLM effectively optimizes power consumption, while

meeting both performance and memory constraints (i.e., $`const_A`$ and

$`const_M`$). Experimental results for investigating the impact of different

$`\alpha`$ values on the model selection are provided in

Fig. 9(a.4) for sentiment classification

task and Fig. 9(b.4) for text generation task. These

results show that, different $`\alpha`$ values may lead to different

model selection, as summarized below. In the sentiment classification task, $`\alpha`$ = 0 guides the QSLM

search strategy to put the memory aspect as non-priority, and hence

leading the selection process toward a model with higher accuracy and

higher memory footprint, as pointed by in

Fig. 9(a.4). Meanwhile, the other

investigated $`\alpha`$ values guide the QSLM search strategy to

adjust the priority level of memory aspect proportional to the

respective $`\alpha`$ value. In this case study, QSLM search strategy

selects a quantized model candidate that is pointed by in

Fig. 9(a.4). These results demonstrate

that, our performance-and-memory trade-off function in QSLM

effectively helps selection of quantized model based on the priority

of memory footprint relative to performance (e.g., accuracy). In the text generation task, all investigated $`\alpha`$ values lead

the QSLM search strategy to select a model with 24 perplexity score

and 68.7% memory saving, as shown by in

Fig. 9(b.4). These results demonstrate

that, there are some conditions that QSLM search strategy finds a

relatively dominant quantized model in performance (e.g., perplexity),

hence adjusting $`\alpha`$ with small values does not change the final

selection for the quantized model. In this paper, we propose the novel QSLM framework for performing

automated quantization on the pre-trained SLMs. Our QSLM significantly

reduces memory footprint by up to 86.5%, decreases power consumption by

up to 20%, preserves high performance across different tasks (i.e., by

up to 84.4% accuracy for the SST-2 dataset and 23.2 perplexity score for

the WikiText-2 dataset), while meeting the given accuracy and memory

constraints. These results also demonstrate that our QSLM successfully

advances the efforts in enabling efficient design automation for

embedded implementation of SLMs. This work was partially supported by the NYUAD Center for CyberSecurity

(CCS), funded by Tamkeen under the NYUAD Research Institute Award G1104.\begin{equation}

S =

\begin{cases}

\arg\max_{A_{acc}, M_q} \Bigl( A_{acc} - \alpha \, \frac{M_q}{M} \Bigr); & \text{for accuracy} \\

\arg\min_{A_{ppx}, M_q} \Bigl( A_{ppx} + \alpha \, \frac{M_q}{M} \Bigr); & \text{for perplexity}

\end{cases}

\label{Eq_Score}

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

A_{ppx} = \exp\left(-\frac{1}{N_T} \sum_{i=1}^{N_T} \log P(w_i \mid w_{<i})\right)

\label{Eq_Perplexity}

\end{equation}Evaluation Methodology

/>

/>

Results and Discussion

/>

/>

style="width:95.0%" />

style="width:95.0%" />

Reducing Memory while Maintaining High Performance

Reduction of Power Consumption

Impact of Different $`\alpha`$ Values on the Model Selection

Conclusion

Acknowledgment

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)