An Agentic Framework for Neuro-Symbolic Programming

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: An Agentic Framework for Neuro-Symbolic Programming- ArXiv ID: 2601.00743

- Date: 2026-01-02

- Authors: Aliakbar Nafar, Chetan Chigurupati, Danial Kamali, Hamid Karimian, Parisa Kordjamshidi

📝 Abstract

Integrating symbolic constraints into deep learning models could make them more robust, interpretable, and data-efficient. Still, it remains a time-consuming and challenging task. Existing frameworks like DomiKnowS help this integration by providing a high-level declarative programming interface, but they still assume the user is proficient with the library's specific syntax. We propose AgenticDomiKnowS (ADS) to eliminate this dependency. ADS translates free-form task descriptions into a complete DomiKnowS program using an agentic workflow that creates and tests each DomiKnowS component separately. The workflow supports optional human-in-the-loop intervention, enabling users familiar with DomiKnowS to refine intermediate outputs. We show how ADS enables experienced DomiKnowS users and non-users to rapidly construct neuro-symbolic programs, reducing development time from hours to 10-15 minutes.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **NeSy Systems:** This paper introduces neuro-symbolic (NeSy) systems that combine deep learning with symbolic reasoning methods to create more robust and interpretable models. Think of it as adding GPS to a car to guide its path, enabling the model to learn while adhering to logical constraints.-

AgenticDomiKnowS (ADS): ADS is introduced as a method for creating NeSy programs using natural language instructions and task descriptions. It functions like an AI coordinator that breaks down tasks into smaller steps, allowing each part to be executed and refined independently.

-

User-Friendly Web Interface: ADS provides an interactive web interface that simplifies the programming process by allowing users to verify or modify code sections easily. This is akin to assembling blocks, where you can edit and run individual parts of the program while viewing their effects in real-time.

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

Deep learning models augmented with symbolic reasoning methods, often referred to as neuro-symbolic (NeSy) systems, aim to combine the strengths of deep learning with the structured, logically consistent symbolic formalisms . NeSy systems could make the models more robust, interpretable, and data-efficient than purely neural approaches . However, authoring NeSy programs remains challenging, as existing frameworks impose a steep learning curve, requiring users to know the syntax and semantics of the target formalism for each symbolic system they employ .

This complexity is exemplified by NeSy frameworks such as DomiKnowS , a declarative Python library that integrates symbolic logic with deep learning models. DomiKnowS operates by allowing users to define a conceptual graph that encodes concepts, relations, and logical constraints, which are then coupled with deep learning models. While this conceptual graph offers significant flexibility, utilizing the library requires mastering its syntax and manually encoding every logical rule. Consequently, this process is both error-prone and time-consuming for those without prior experience with the framework.

A previous attempt to generate DomiKnowS programs with LLM assistance focused solely on the creation of the conceptual graph and its constraints, and not a complete DomiKnowS program. Constrained by the capabilities of earlier LLMs, it is designed to provide a UI that primarily serves as a coding assistant, requiring significant intervention by users who are familiar with the library. While newer LLMs have improved at expressing logical constraints and high-level relational structures , they continue to struggle with mapping them into correct syntax for domain-specific libraries. Additionally, because NeSy libraries like DomiKnowS are underrepresented or non-existent in pre-training corpora, LLMs frequently fail to generate their programs .

In this demo paper, we introduce AgenticDomiKnowS (ADS) to overcome these generation barriers and enable users to create NeSy programs using natural language instructions and task descriptions. Unlike coding assistants such as Codex or Gemini CLI 1 that synthesize an entire program at once, ADS employs an agentic workflow that breaks the development process into distinct stages, generating, executing, and refining each code section independently. This allows ADS to isolate and fix errors within specific components. ADS uses an iterative loop to fix syntactic errors identified during code execution and semantic errors detected by an LLM-based reviewer in a self-refinement process . ADS supports an optional human-in-the-loop mechanism for user intervention.

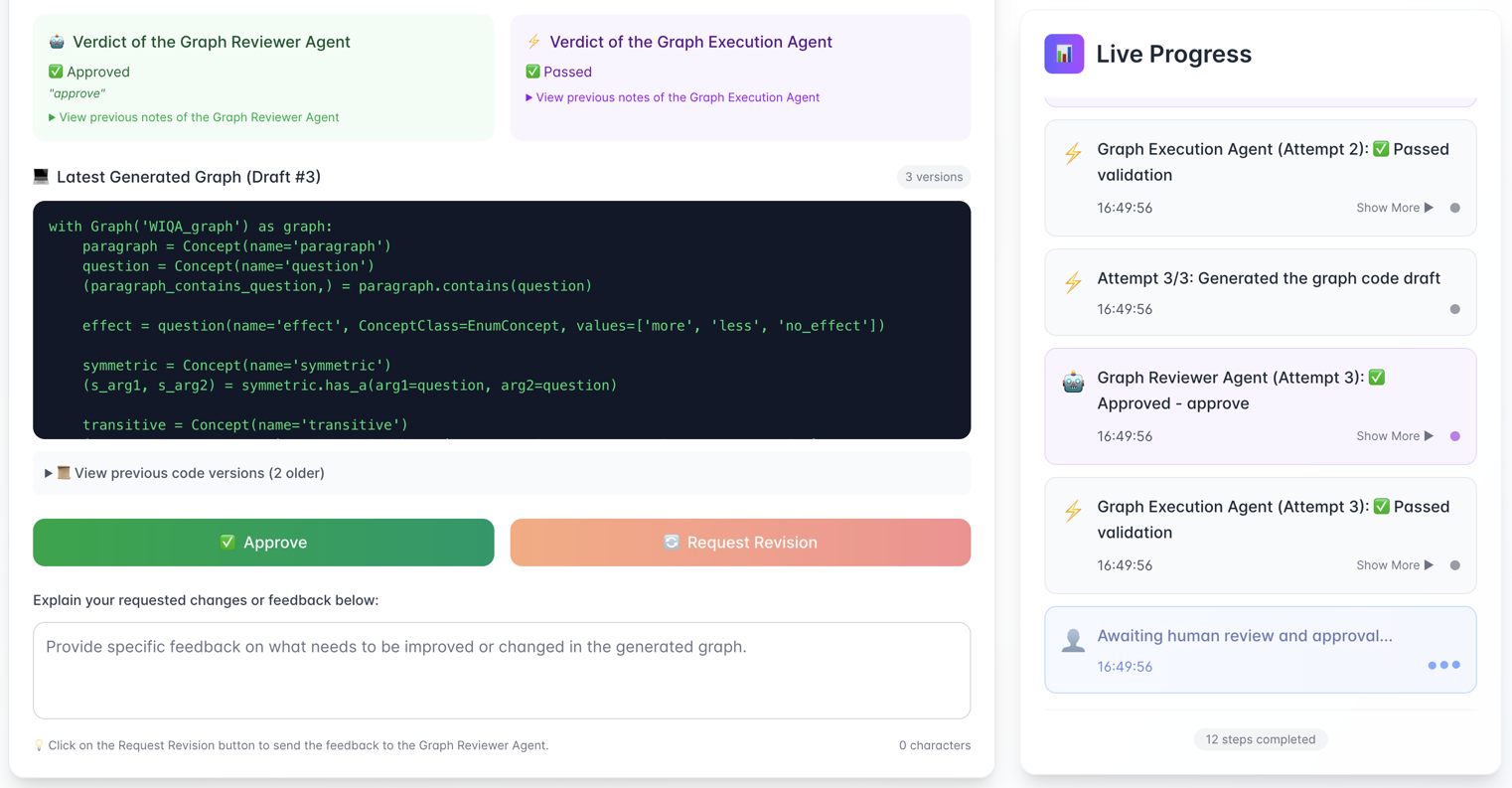

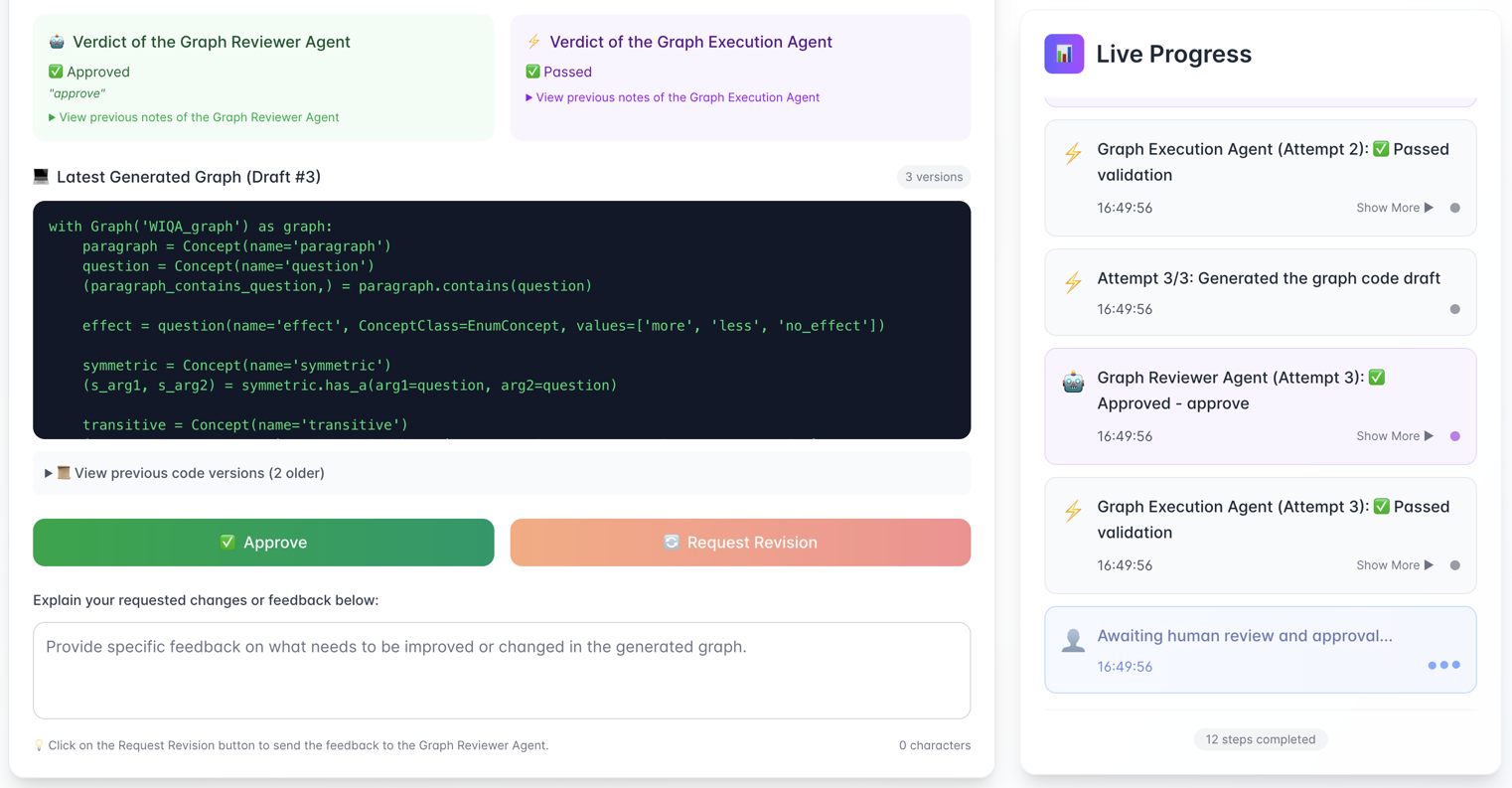

We facilitate this human-in-the-loop mechanism through an interactive web interface that provides access to ADS and visualizes the information needed for verification or refinement. The interface generates the DomiKnowS program as a plug-and-play executable Jupyter notebook, utilizing general-purpose VLMs as pre-initialized learning models for immediate inference. We also show how ADS helps DomiKnowS users accelerate their programming and non-users adopt NeSy programming without prior implementation experience.

Background: DomiKnowS

DomiKnowS uses a domain-specific Python-based language to define concepts, relations, and logical operators that encode domain knowledge as logical constraints. We use a procedural question-answering task, WIQA , to illustrate a DomiKnowS program. The WIQA dataset consists of paragraphs and associated questions asking about the effect of a perturbation, labeled as is_more, is_less, or no_effect. Crucially, there exists a transitivity relation between the answers to these questions when they form a causal chain. For example, if one question asks about the effect of step $`A`$ on $`B`$, and another about $`B`$ on $`C`$, their answers logically constrain the answer to a third question regarding the effect of $`A`$ on $`C`$. We consider this transitivity essential for solving the task because it allows us to inject domain knowledge into the model, ensuring that predictions across related questions remain globally consistent. Figure 1 shows how this task is represented in DomiKnowS, highlighting two main components of a DomiKnowS program: the Knowledge Declaration and the Model Declaration.

In the Knowledge Declaration, we specify a conceptual graph that

includes the concepts and relations. Using the concepts of this graph,

the logical constraints needed to model this task can be defined. For

WIQA, we create a paragraph concept and a question concept. We

define the answer classes, is_more, is_less, and no_effect, that

serve as labels associated with the questions. We define a one-to-many

containment relation between paragraphs and questions. To express the

logical relations between questions, we introduce a transitivity

concept that connects triplets of questions ($`t_1, t_2, t_3`$).

Finally, we add a logical constraint using ifL and andL operators:

if a transitivity relation exists for a triplet then if the first two

question ($`t_1, t_2`$) both indicate an increase (is_more), then the

third question ($`t_3`$) must also indicate an increase.

In the Model Declaration, we load the data elements from the dataset and

attach them as properties to the corresponding concepts using predefined

DomiKnowS sensors (e.g., ReaderSensor). We also assign trainable

models here: an LLMLearner wrapping an LLM to predict the question

labels. We populate the graph edges, such as the transitivity triplets

provided by the dataset. After these steps, the program can be executed

to infer the outputs while obeying the logical constraints using Integer

Linear Programming (ILP) . Moreover, we can train the models to learn to

satisfy the constraints using the underlying algorithms proposed in

related research .

System Overview

style="width:100.0%" />

style="width:100.0%" />

ADS is implemented as a LangGraph2 workflow over a shared memory state between multiple agents. It stores the task description, code drafts, reviews, and outputs of code executions. As depicted in Figure 2, the workflow starts with a user-provided natural-language task description. Using this task description, examples of similar tasks are retrieved from a RAG database, and then ADS proceeds through the two main phases of Knowledge Declaration and Model Declaration.

RAG

The process begins with a retrieval step in which, given the input task description, the Rag Selector agent searches a pool of 12 prior DomiKnowS programs and retrieves the five most similar ones based on their task descriptions. These serve as in-context examples for the LLMs later in the workflow. These retrieved programs are authored by users of DomiKnowS library.

Knowledge Declaration

The next step is generating the Knowledge Declaration code, which produces a graph code comprising the conceptual graph and first-order logical constraints. Knowledge Declaration is handled by a feedback loop between three agents: The Graph Design Agent proposes a new graph code implementation based on the task description and the retrieved RAG examples. Consequently, the Graph Execution Agent executes the newly generated graph code and records the output errors. In parallel, the Graph Reviewer Agent produces a natural-language review of the generated graph to verify its semantics. This reviewer suggests that the constraints be modified if needed, correct the definition of relations, and remove unnecessary concepts. If the generated graph is not approved by either or both the Graph Execution Agent and the Graph Reviewer Agent, it will be sent back to the Graph Design Agent along with the feedback.

When the agents either approve a draft or hit the attempt limit, the workflow reaches Graph Human Reviewer, which asks the user whether they approve the graph and to collect feedback otherwise. If the user rejects the graph, the system clears accumulated review and execution notes, resets the attempt counter, and sends control back to Graph Design Agent for a new round of revisions while applying the human feedback. If the user approves, the controller advances to the next stage.

Model Declaration

In the Model Declaration stage, ADS assigns sensors and learners to the graph concepts. A central design decision in ADS is to minimize the use of some complex DomiKnowS classes without losing any DomiKnowS functionalities and instead delegating their operations to ordinary Python code, which LLMs are generally better at generating. This results in sensors being the i) ReaderSensor, which is used to read the data elements, ii) LabelReaderSensor, which is used to read the labels/annotations, iii) EdgeReaderSensor, which connects the concepts in a containment relation, and iv) ManyToManyReaderSensor, which connects the concepts in a has_a relationship.

The Learner Module in DomiKnowS, which assigns a deep learning model to predict a label, is replaced by a multi-purpose VLM named LLMModel. This allows the learner to process multimodal inputs. The learner can perform zero-shot inference or be fine-tuned within the DomiKnowS framework for improved accuracy.

The Sensor Design Agent generates the sensor code based on the task description, generated graph, and the RAG retrieved sensor codes. If syntax errors occur, it attempts one automatic refinement. The resulting code is then handed to the Sensor Human Coder, who can either approve it or edit it further. In the second step of the Model Declaration stage, the user explains in natural language how dataset elements map to the graph concepts. This assignment is deferred to this stage to accommodate varying graph designs. Using user’s description and retrieved RAG examples, the Property Designator Agent updates the code to bind dataset elements as concept properties. Additionally, the agent generates tailored prompts for the VLMs, specifying their outputs. The final code is exported to a Jupyter notebook containing cells for the graph, dataset, and sensor sections, along with the DomiKnowS installation commands.

User Interface Implementation

ADS’ user interface (UI) is implemented as a web application composed of a Next.js 3 frontend and a Python backend, FastAPI 4. The system is hosted on infrastructure managed by the Division of Engineering Computing Services at Michigan State University, utilizing a server equipped with dual AMD EPYC 7413 24-Core Processors and 755 GB of RAM. UI’s goal is to provide general access to ADS and to facilitate effective human-in-the-loop interaction by clearly displaying the information necessary for verification or refinement.

Backend

The backend is a Python service built with FastAPI acting as the central orchestrator, exposing REST endpoints to the React frontend while interfacing with a containerized MongoDB 5 instance. In the MongoDB database, the backend stores the LangGraph memory state after each user interaction, together with basic user and session information.

Frontend

The frontend is a Next.js app built with React 6 and TypeScript, styled with CSS, and communicating with the backend via HTTP requests to a REST API. At each step of the workflow shown in Figure 2, the interface retrieves the complete LangGraph memory state but dynamically renders only the information relevant to the current specific stage. For example, as illustrated in Figure 3, the Graph Human Reviewer is presented with a view containing the latest generated graph code, agent verdicts, and execution logs. This design ensures that the user has access to all context necessary to make an informed decision. Additionally, the user can switch tabs to inspect details from previous steps, providing an optional historical view.

style="width:100.0%" />

style="width:100.0%" />

Experiments

Datasets

We use a test dataset of 12 previously developed DomiKnowS programs that span Natural Language Processing, Computer Vision, and Constraint Satisfaction Problems (CSP). The NLP tasks encompass hierarchical topic classification on the 20 News dataset , logical and causal reasoning covering RuleTaker , WIQA , BeliefBank , and ProPara , as well as consistency-constrained classification using Spam and IMDB . In the Vision domain, we utilize hierarchical image recognition with hierarchically grouped CIFAR-10 and Animals & Flowers image classification alongside arithmetic constraint tasks like MNIST-Sum . Finally, the CSP category includes classical combinatorial inference problems such as Sudoku and Eight Queens to test strict logical constraint satisfaction. Refer to the Appendix 8 for more details about these tasks. These 12 examples also serve as the retrieval corpus for our RAG framework. As a result, during the testing of a specific example, it is excluded from the retrieval base to prevent data leakage. Additionally, we introduce three new tasks for human evaluation designed to assess performance across increasing levels of constraint complexity: simple unconstrained classification of Amazon Reviews , hierarchical classification of Scientific papers (WOS) , and sequence labeling of CoNLL dataset entities with constraints on tags.

Language Models

For our experiments, we employ GPT-5 version gpt-5-2025-08-07 to evaluate performance across reasoning levels ranging from minimal to medium. We also used two state-of-the-art open-weight models: Kimi-K2-Thinking and DeepSeek-R1-V3.1 . Although these models demonstrated superior performance, their long inference latency made them impractical for an interactive website.

Evaluation of ADS Workflow

The first significant step of our workflow is Knowledge Declaration, where the conceptual graph is generated. To evaluate the graphs, we sampled each task in our test dataset three times for a total of 36 tests. We manually assess syntactically correct graphs using two annotators, labeling them as Correct, Redundant (semantically correct but with harmless redundant constraints), and Semantically Incorrect. As detailed in Table 1, open-weights models DeepSeek R1 and Kimi k2 achieved the best results, with Kimi k2 reaching 97.22% accuracy. However, their inference latency was notably high, rendering them impractical for deployment in an interactive web UI. We therefore use GPT-5 (low) in this stage of the workflow, which matches GPT-5 (medium) with 86.11% accuracy but offers a superior speed-accuracy trade-off. Our analysis also suggests that GPT-5 and Kimi k2 specifically benefited from the inclusion of the Graph Reviewer Agent, whereas DeepSeek used it to a lesser extent. To see the detailed results, refer to the Appendix 10.

| Model | C | R | C + R |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-5 (Minimal) | 44.44% | 25.00% | 69.44% |

| GPT-5 (Low) | 61.11% | 25.00% | 86.11% |

| GPT-5 (Medium) | 69.44% | 13.89% | 83.33% |

| DeepSeek R1 | 69.44% | 19.44% | 88.89% |

| Kimi k2 | 86.11% | 11.11% | 97.22% |

Percentage of correct graphs (C), semantically correct graphs with harmless redundancies (R), and all semantically correct graphs (C+R) for each model.

For the Model Declaration stage, we set the graph generator model to GPT-5 (Low) and vary the reasoning level only for the model-code generation to test the workflow end-to-end. We sample each of the 12 test tasks 5 times, yielding 60 runs in total. GPT-5 with minimal, low, and medium reasoning results in 20, 14, and 11 failures, respectively. Because this stage does not employ the large iterative repair loop used in Knowledge Declaration, we choose GPT-5 (medium) for Model Declaration, as it provides the best accuracy while maintaining acceptable inference time. By manually inspecting three runs per task, we observed that at this point in the pipeline, any remaining issues in the code, aside from semantically incorrect graphs, are reliably captured by running the program. Refer to Appendix 10 for detailed results.

Human Evaluation

We assessed ADS with six participants (three DomiKnowS experts and three non-users) using three progressively difficult tasks. We measured the development time for each task, excluding runtime. Detailed information regarding the task specifications and participant instructions is available in Appendix 9. Empirically, creating DomiKnowS programs is time-consuming, often requiring hours to implement even simple tasks. In contrast, using ADS, DomiKnowS users finish most tasks in about 10-15 minutes, as shown in Table 2.

Users 1 and 3 only edited code to read the dataset inputs. User 2 modified task 2’s sensor code and asked the model to revise the graph in Task 3. User 4 completed tasks 1 and 3 easily, but found task 2’s semantically correct batch definition (article_group.contains(article)) difficult to resolve. User 5 succeeded without issues, debugging task 2 despite lacking familiarity with the framework. User 6 also succeeded in all tasks and spent 5 minutes debugging Task 3’s code.

| Users | Non-Users | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-4 (lr)5-7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Task 1 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 15 | 9 |

| Task 2 | 10 | 10 | 9 | F | 15 | 10 |

| Task 3 | 11 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 8 | 15 |

Related Work

Integration of neural learning models with symbolic reasoning has led to the development of various NeSy frameworks . In this work, we use DomiKnowS , which creates a declarative graph-based representation to formulate Domain Knowledge. DomiKnowS distinguishes itself by supporting a flexible formulation of NeSy integration, allowing users to switch between various training and inference algorithms and enabling supervision at the granular concept level. For a comprehensive comparison of DomiKnowS and other NeSy frameworks, such as DeepProbLog , and Scallop , we refer the reader to .

Our objective of synthesizing NeSy programs from natural language descriptions necessitates the use of LLMs as coders. While LLMs have shown remarkable proficiency in generating code for general-purpose languages like Python , their performance degrades significantly on languages or libraries where training data is scarce . Consequently, existing NeSy frameworks typically utilize LLMs only with task-specific prompts to extract symbolic representations of natural language queries , or configure learning components, such as crafting prompts .

Our work aligns most closely with research on end-to-end NeSy program generation. However, prior efforts in this space generally rely on task-specific prompt engineering and custom tool interfaces or executors . In contrast, we address the challenge of synthesizing complete, executable programs for a NeSy library with scarce training data. Our approach is domain-agnostic and enables program generation for any task or domain that can be represented in DomiKnowS.

Conclusion and Future Work

We introduced AgenticDomiKnowS (ADS), an interactive framework that enables NeSy programming by using natural language task descriptions. By decomposing the workflow into modular stages with self-correcting syntactic and semantic agents, ADS eliminated the steep learning curve typically associated with DomiKnowS. We showed that ADS enables DomiKnowS users and non-users to rapidly construct NeSy programs.

For future work, we aim to extend our methodology to a generalized system that supports any open-source NeSy framework that are low-resource for pre-training of LLMs. We plan to develop mechanisms that automatically recognize and separate a library’s distinct components, gathering specific information and examples for each. This will allow the system to generate and test components individually, facilitating end-to-end synthesis of NeSy programs across different symbolic formalisms.

DomiKnowS Selected Tasks

Natural Language Processing Tasks

Hierarchical News Classification

This task involves performing topic classification using the 20 News dataset , organized into three distinct levels of granularity. The objective is to assign news articles to broad categories at Level 1 (e.g., comp, sci, rec), sub-categories at Level 2 (e.g., windows, crypt, autos), and specific entities at Level 3 (e.g., IBM, hockey, guns). The primary modeling challenge lies in satisfying strict hierarchical consistency constraints, which dictate that a valid classification path must respect parent-child relationships. For example, selecting a class like “baseball” necessitates the activation of its parent “sport” and ancestor class “rec”.

Spam Classification

This task utilizes a dataset of emails containing headers, bodies, and spam labels to evaluate consistency modeling. The objective involves deploying two independent classifiers that predict whether a given email is spam or not based on its content. The constraint is a logical consistency requirement between these two models to prevent contradictory outputs. Specifically, the system enforces that the predictions must align such that if the first model predicts “spam”, the second model is prohibited from predicting “not spam”.

Sentiment Analysis

Using the IMDB dataset , this task performs sentiment analysis. One model predicts separate positive and negative probabilities, respectively. A constraint is applied to enforce single-label classification, ensuring every review is categorized as strictly positive or negative.

Procedural Text Understanding

This task utilizes the ProPara dataset to evaluate a model’s ability to track and reason about the dynamic states of entities within procedural text. The objective is to monitor the lifecycle of various elements across a sequence of steps, determining their specific location status (known, unknown, or non-existent) at each stage, while simultaneously identifying the transition actions—such as create, destroy, or other—that drive these changes. The constraints enforce strict causal consistency between actions and state updates. For instance, an action classified as create or destroy must logically correspond to a valid transition between existence and non-existence, ensuring that the predicted sequence of events adheres to the physical laws described in the procedure.

Causal Reasoning

This task focuses on reasoning about cause-and-effect relationships within procedural texts using the WIQA dataset . The objective is to analyze paragraphs describing sequences of events and determine the qualitative influence between events categorized as: 1) more (positive effect), 2) less (negative effect), or 3) no effect. Logical constraints here include symmetry and transitivity. Symmetric constraints dictate that if the effect of a cause is reversed, e.g., more rain becomes less rain, the effect must invert. Transitivity constraints ensure logical consistency across chains of events. For instance, if event A increases event B, and event B increases event C, then event A must also be inferred to increase event C.

Belief-Consistent Question Answering

This task focuses on verifying the truthfulness of facts associated with various entities using the BeliefBank dataset , with a primary emphasis on maintaining global consistency across predictions. The system evaluates a set of candidate sentences describing an entity, aiming to determine which assertions are factually correct. The critical constraint mechanism is derived from a provided relational graph that defines positive and negative correlations between specific attributes. For example, classifying an entity as a “bird” might positively imply it “can fly”, while classifying it as a “reptile” might negatively correlate with that same trait. As a result, if a specific attribute is predicted as true, all positively correlated attributes must also be accepted, and all negatively correlated attributes must be rejected, resulting in a non-contradictory set of beliefs for each entity.

Logical Reasoning Question Answering

This task evaluates logical reasoning capabilities using the RuleTaker dataset , where the model is presented with a context paragraph containing natural language atomic facts and implication rules. For each context, the model must answer a series of questions verifying the truth value of specific facts. The core constraint is to enforce logical consistency across these predictions. Specifically, if the context establishes a conditional rule (e.g., “if A then B”) and the model affirms the antecedent, it is structurally required to affirm the consequent, ensuring that the set of predicted answers adheres to the deductive logic.

Vision Tasks

Hierarchical Image Classification I

This task applies a hierarchical structure to the standard CIFAR-10 dataset , organizing the ten base classes into two high-level semantic groups: “animal” and “vehicle”. The animal category subsumes natural entities, “bird”, “cat”, “deer”, “dog”, “frog”, and “horse, whereas the “vehicle” category includes artificial objects, “airplane”, “automobile”, “ship”, and “truck”. The model must respect the strict implication that selecting a specific subclass, e.g., “ship”, necessitates the activation of its correct parent, “vehicle”.

Hierarchical Image Classification II

This task employs the Animals and Flowers Image Classification dataset to evaluate hierarchical classification capabilities. The objective is to correctly identify images at two distinct levels: a coarse-grained superclass level (“animal” or “flower”) and a fine-grained subclass level containing specific entities. The constraints require that every image be assigned exactly one specific leaf node, which automatically implies its corresponding parent category.

Constrained Digit Classification

This task augments the standard MNIST handwritten digit recognition challenge by processing images in pairs rather than individually . The objective is to classify each image into one of ten digit classes. The model is also provided with the ground-truth sum of the two digits in the pair. The defining constraint is arithmetic consistency: the predictions for the two individual images must mathematically add up to the provided sum.

Constraint Satisfaction Problem Tasks

Sudoku Puzzle

This task involves solving Sudoku puzzles starting from a partially filled grid. The objective is to populate the remaining cells such that the entire board satisfies strict logical rules. The model represents the puzzle’s structural components, explicitly defining concepts for the board, rows, columns, and $`3 \times 3`$ sub-tables. The constraints strictly enforce the uniqueness property, such that no digit is repeated within any single row, column, or sub-table.

Eight Queens Puzzle

This task utilizes a dataset of partially filled chessboards to address the Eight Queens Puzzle. The objective is to determine the correct placement of the remaining queens on an $`8 \times 8`$ grid to achieve a complete and valid configuration. The constraint for this task requires that no two queens may occupy attacking positions relative to one another.

Instructions for the Human Study

Overview

Thank you for participating in this study. The goal of this experiment is to evaluate a system that translates natural language instructions into neuro-symbolic deep learning programs. You will be asked to describe specific tasks to the system, run the generated code, and report on the accuracy and efficiency of the process.

Phase 1: System Access

To begin the experiment, please open the demonstration interface at https://hlr-demo.egr.msu.edu/ and log in using the credentials provided by the instructor.

Phase 2: Task Workflow

For each of the tasks defined at the end of the instructions, please follow this procedure:

Define the Task

When the system asks you to describe the task, provide a detailed natural language description. Your description should clearly specify:

-

What the model needs to predict and how the different labels relate to one another.

-

Explicitly state if there are constraints or if there are none. If multiple constraints exist, define them individually.

You do not need to fully define all dataset features upfront. The system will prompt you for the dataset features in subsequent steps.

Continue to Navigate the Interface

-

Interact with the Interface and provide the requested information until the final code is provided in a Jupyter Notebook.

-

If you are not familiar with the DomiKnowS framework, strictly skip optional feedback or code editing prompts.

-

If you make a mistake, click “New task” (top-right) to start over.

Execute the Program

Once the website generates a program:

-

Download the generated Jupyter notebook.

-

Run the notebook locally or upload it to Google Colab (recommended).

-

Follow any instructions inside the notebook to import the datasets. Minor Python edits may be required to load the data correctly.

Phase 3: Reporting Results

After attempting all tasks, please compile a report containing:

-

How many tasks executed successfully using the instances in

domiknows.datasets. -

Approximate duration for each task in minutes.

-

Please submit your final notebooks.

Task Definitions

Preprocessed instances of the required datasets are provided in https://github.com/HLR/AgenticDomiKnowS/blob/execution/domiknows/datasets.py . Please complete the following three tasks:

Task (i): Amazon Reviews

Goal: Predict review ratings (1–5 stars) for an Amazon review dataset. There are no logical constraints between predictions.

Dataset Fields:

-

review_id -

title -

text -

label(Star rating: 0–4)

Task (ii): WOS Dataset

Goal: Predict two labels for each scientific article: a coarse category and a fine category. The predictions should not violate the parent-child relationships.

Hierarchy:

-

ECE $`\rightarrow`$ [Electricity, Digital control, Operational amplifier]

-

Psychology $`\rightarrow`$ [Attention, Child abuse, Social cognition, Depression]

-

Biochemistry $`\rightarrow`$ [Polymerase chain reaction, Molecular biology, Northern blotting, Immunology]

Dataset Fields:

-

article_id, -

coarse_id -

fine_id -

text -

coarse_label(Values 0–2), -

fine_label(Values 0–11)

Task (iii): Sequence Labeling of CoNLL Dataset

Goal: Given a sequence of tokens in a sentence, predict an IOB tag for each token. The tags must be consistent (e.g., an “I” tag cannot appear immediately after an “O” tag).

Dataset Fields:

-

sentence_id -

token_ids -

tokens -

labels(IOB tags)

Detailed Evaluation Results

We evaluate the workflows’ performance through a multi-stage analysis targeting both the Knowledge Declaration component and the complete workflow execution. Table [tab:automaticevaluation] presents the quantitative metrics from the automatic evaluation of the Knowledge Declaration phase, detailing the operational overhead in terms of design iterations, reviewer feedback loops, and syntax corrections required by different. Complementing these automatic metrics, Table [tab:tagged] provides the corresponding qualitative manual assessment for these sample runs. Extending the analysis to the end-to-end system, Table [tab:workflowresults] summarizes the error distribution for the entire workflow under different GPT-5 reasoning levels.

| Model | Sample | Tasks | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-14 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| GPT-5 (Minimal) | S1 | (2,1,0) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,2,3) | (3,3,3) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,2,1) | (3,3,0) | (2,1,0) |

| S2 | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,3,1) | (1,0,0) | (2,0,1) | (2,1,0) | (3,2,2) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,1,1) | (2,0,1) | |

| S3 | (3,1,1) | (1,0,0) | (3,3,3) | (3,3,1) | (1,0,0) | (3,1,2) | (3,2,0) | (3,0,2) | (1,0,0) | (3,3,0) | (2,1,1) | (2,1,0) | |

| S1 | (1,0,0) | (3,3,0) | (3,2,0) | (2,0,1) | (1,0,0) | (3,3,2) | (1,0,0) | (3,3,3) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,1) | (3,3,0) | (2,0,1) | |

| S2 | (2,0,1) | (2,1,0) | (3,3,2) | (2,1,1) | (2,0,1) | (3,3,1) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,1) | (2,1,0) | (2,1,0) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,0) | |

| S3 | (2,1,1) | (3,2,0) | (1,0,0) | (2,0,1) | (1,0,0) | (3,3,3) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,1) | (3,3,0) | (2,1,0) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,0) | |

| GPT-5 (Medium) | S1 | (3,2,1) | (1,0,0) | (3,2,1) | (3,1,1) | (2,1,1) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,1) | (3,3,2) | (3,3,0) | (3,3,0) | (3,2,0) |

| S2 | (3,2,1) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,0) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,1) | (2,1,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,2,3) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,1) | (3,2,0) | (1,0,0) | |

| S3 | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,3,1) | (3,3,1) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,2,3) | (3,3,1) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | |

| S1 | (3,2,1) | (1,0,0) | (3,2,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,2,0) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,0) | (2,1,0) | (2,1,0) | (1,0,0) | |

| S2 | (3,2,0) | (3,3,0) | (2,1,0) | (3,3,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,2,0) | (2,1,1) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | |

| S3 | (3,2,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,0) | (2,1,1) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,0) | |

| DeepSeek R1 | S1 | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,0,3) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) |

| S2 | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (2,1,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,1,1) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,0,3) | (2,0,1) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | |

| S3 | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | (3,0,3) | (1,0,0) | (1,0,0) | |

| Model | Sample | Tasks | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-14 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| GPT-5 (Minimal) | S1 | Se | C | R | C | R | Se | Sy | Se | C | Se | Se | C |

| S2 | C | C | R | Sy | C | Se | R | Se | C | Se | C | C | |

| S3 | R | C | C | C | C | Se | R | Se | C | R | R | C | |

| S1 | C | R | C | C | C | C | R | Sy | C | R | C | C | |

| S2 | C | C | Sy | C | C | Sy | R | C | C | R | C | C | |

| S3 | C | R | R | C | C | Sy | R | C | Se | R | C | C | |

| GPT-5 (Medium) | S1 | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | Sy | C | Se | C |

| S2 | C | R | C | C | C | C | R | Sy | C | R | Se | C | |

| S3 | C | R | C | C | C | C | R | Sy | Se | C | C | C | |

| S1 | Sy | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | |

| S2 | C | C | C | R | R | C | R | C | C | C | C | C | |

| S3 | C | C | C | C | C | C | R | C | C | C | C | C | |

| DeepSeek R1 | S1 | C | R | Sy | C | C | C | R | C | C | R | C | C |

| S2 | C | C | Se | C | C | C | R | Sy | C | R | C | C | |

| S3 | C | R | C | C | C | C | R | C | C | Sy | C | C | |

| Level | Sample | Tasks | Total | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-14 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

| Minimal | S1 | S | G | S | G | G | S | 20 | ||||||

| S2 | S | G | S | |||||||||||

| S3 | S | S | S | S | ||||||||||

| S4 | S | G | S | |||||||||||

| S5 | S | G | G | G | ||||||||||

| Low | S1 | S | G | S | 14 | |||||||||

| S2 | S | S | ||||||||||||

| S3 | S | S | ||||||||||||

| S4 | G | G | S | |||||||||||

| S5 | S | S | S | S | ||||||||||

| Medium | S1 | G | S | S | 11 | |||||||||

| S2 | S | |||||||||||||

| S3 | G | S | ||||||||||||

| S4 | S | S | ||||||||||||

| S5 | G | S | S | |||||||||||

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)

A Note of Gratitude

The copyright of this content belongs to the respective researchers. We deeply appreciate their hard work and contribution to the advancement of human civilization.-

These assistants proved incapable of generating DomiKnowS programs from documentation in our initial testing. ↩︎