Value Vision-Language-Action Planning & Search

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Value Vision-Language-Action Planning & Search- ArXiv ID: 2601.00969

- Date: 2026-01-02

- Authors: Ali Salamatian, Ke, Ren, Kieran Pattison, Cyrus Neary

📝 Abstract

Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models have emerged as powerful generalist policies for robotic manipulation, yet they remain fundamentally limited by their reliance on behavior cloning, leading to brittleness under distribution shift. While augmenting pretrained models with test-time search algorithms like Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) can mitigate these failures, existing formulations rely solely on the VLA prior for guidance, lacking a grounded estimate of expected future return. Consequently, when the prior is inaccurate, the planner can only correct action selection via the exploration term, which requires extensive simulation to become effective. To address this limitation, we introduce Value Vision-Language-Action Planning and Search (V-VLAPS), a framework that augments MCTS with a lightweight, learnable value function. By training a simple multilayer perceptron (MLP) on the latent representations of a fixed VLA backbone (Octo), we provide the search with an explicit success signal that biases action selection toward high-value regions. We evaluate V-VLAPS on the LIBERO robotic manipulation suite, demonstrating that our value-guided search improves success rates by over 5 percentage points while reducing the average number of MCTS simulations by 5-15 percent compared to baselines that rely only on the VLA prior.💡 Summary & Analysis

**3 Key Contributions:** 1. **Value Function Introduction:** Introduces a value function to complement the limitations of VLA models in predicting future success. 2. **MCTS Improvement:** Integrates this value function into MCTS for more effective planning and search capabilities. 3. **Performance Enhancement:** Demonstrates improved success rates and reduced simulation counts in LIBERO robotic manipulation tasks.Simple Explanation:

- Comparison: The VLA model teaches robots to act based on camera inputs and language instructions but struggles with predicting future success alone.

- Solution: This paper proposes adding a value function to the MCTS search algorithm, enabling more intelligent robot behavior.

Sci-Tube Style Script:

- Beginner Level: “How do we teach robots to behave? This paper adds a value function to the MCTS search algorithm to make robots smarter.”

- Intermediate Level: “VLA models are effective for teaching robots but have limitations in predicting future success. Adding a value function to MCTS can solve this issue.”

- Advanced Level: “To address VLA model sensitivity under distribution shifts, we propose the V-VLAPS framework, which significantly improves robotic manipulation performance and efficiency.”

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

Abstract

Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models have emerged as powerful generalist policies for robotic manipulation, yet they remain fundamentally limited by their reliance on behavior cloning, leading to brittleness under distribution shift. While augmenting pretrained models with test-time search algorithms like Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) can mitigate these failures, existing formulations rely solely on the VLA prior for guidance, lacking a grounded estimate of expected future return. Consequently, when the prior is inaccurate, the planner can only correct action selection via the exploration term, which requires extensive simulation to become effective. To address this limitation, we introduce Value Vision-Language-Action Planning and Search (V-VLAPS), a framework that augments MCTS with a lightweight, learnable value function. By training a simple multi-layer perceptron (MLP) on the latent representations of a fixed VLA backbone (Octo), we provide the search with an explicit success signal that biases action selection toward high-value regions. We evaluate V-VLAPS on the LIBERO robotic manipulation suite, demonstrating that our value-guided search improves success rates by over 5 percentage points while reducing the average number of MCTS simulations by 5–15% compared to baselines that rely only on the VLA prior.

startsection section1@-2.0ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex1.5ex plus 0.3ex minus0.2ex

Introduction

Deploying robotic policies in open-world settings requires reliability under distribution shift. Recent advances in robot learning have been driven by large-scale Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models, transformer policies that predict action sequences from multimodal observations and language instructions. While VLA models serve as effective priors for generalist behaviors, they are fundamentally limited by their reliance on behavior cloning. As a result, they often exhibit brittle behavior when facing out-of-distribution (OOD) states.

A promising approach to address this problem is to augment the pretrained model with a planning search algorithm that explores possible outcomes in simulation. One such search algorithm is Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), which constructs a search tree by simulating rollout trajectories, balancing exploration of uncertain actions with exploitation of high-likelihood ones . Following , we can leverage a VLA model as a policy prior to guide the MCTS, using a visit-count heuristic to manage exploration. However, we observe that relying solely on the VLA prior is insufficient for robust long-horizon planning. In the formulation proposed by , the search lacks a value function, meaning it has no grounded estimate of the expected future return. Consequently, if the VLA prior is inaccurate, assigning high probability to suboptimal actions, the planner has no mechanism to correct this bias other than exhaustive count-based exploration. In other words, the search relies on the imitation prior rather than the underlying reward structure.

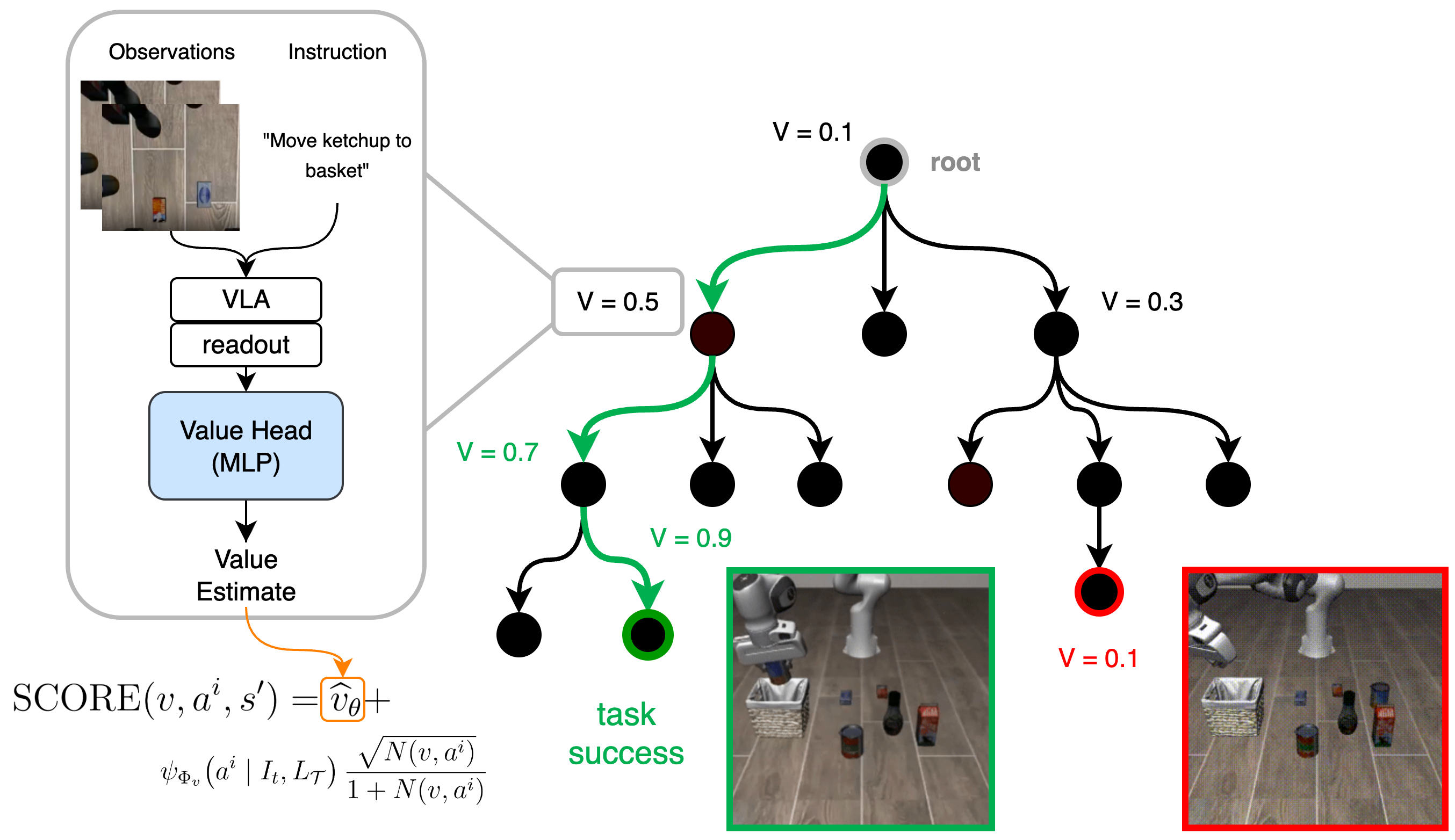

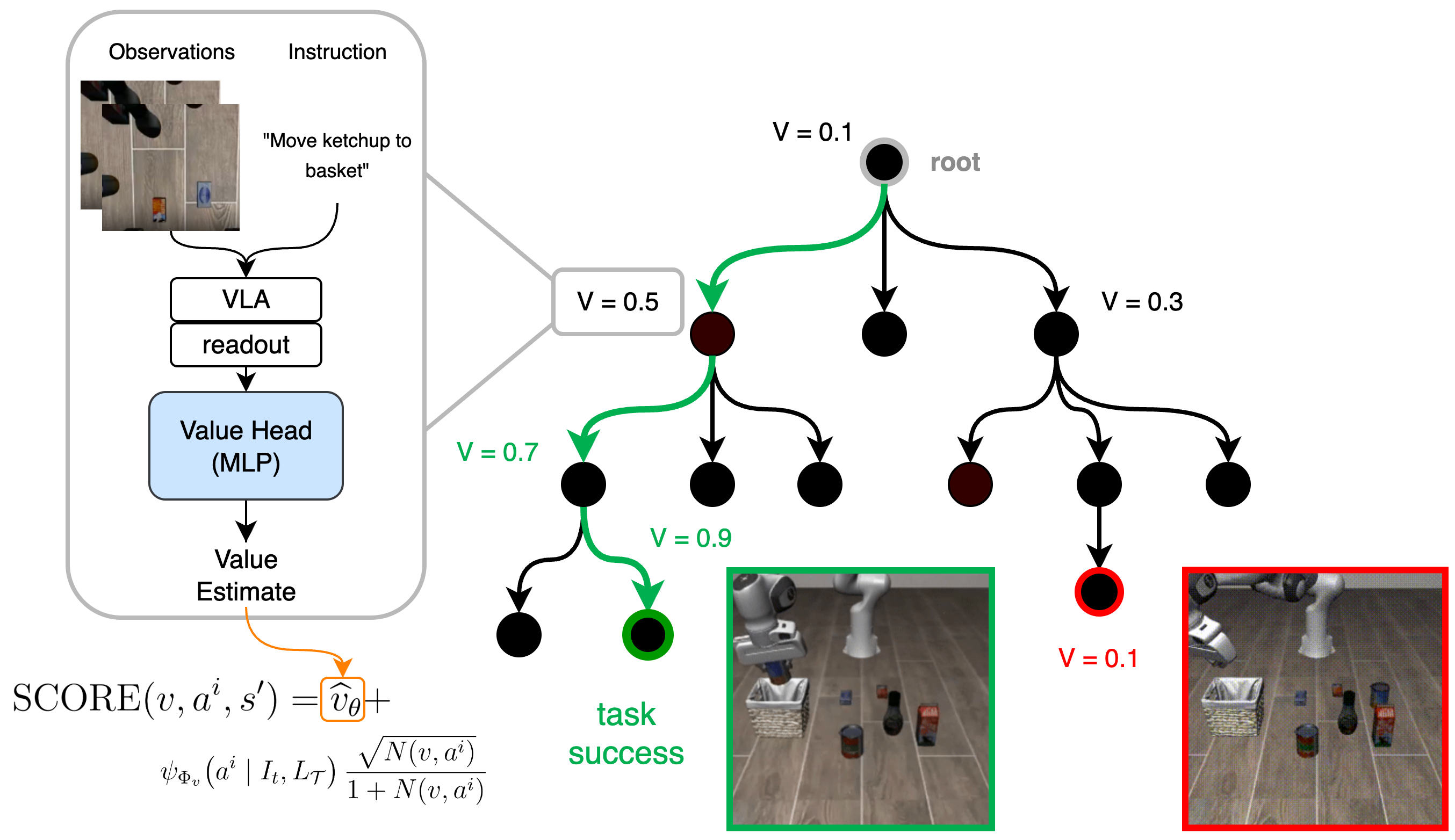

To address this limitation, we introduce Value Vision-Language-Action Planning and Search (V-VLAPS). As shown in Figure 1, we augment the MCTS action selection with a lightweight and learnable value head that is similar to the search formulation used by . This value head provides the missing reward signal, biasing action selection toward states with higher expected return and effectively correcting the search when the prior policy is inaccurate. This is a promising approach, as we show in Section [sec:experiments_and_results], even training a very small value head on a small set of data can help with biasing the action selection towards the right region of the action space. We further show the benefits of adding a value head by evaluating V-VLAPS in a simulated suite of robotic manipulation tasks (LIBERO). Our simple change results in over 5 percentage points improvement of the success rate while reducing the average number of MCTS simulations by 5-15% depending on the task suite.

startsection section1@-2.0ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex1.5ex plus 0.3ex minus0.2ex

Related Work

startsectionsubsection2@-1.8ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex0.8ex plus .2ex

Vision–Language–Action Policies Vision–language–action (VLA) models are designed to map visual observations and natural-language instructions directly to robot actions. Early systems showed that a single transformer policy can be trained on large collections of robot demonstrations and language-labelled tasks, and then be reused across many manipulation skills . In our work, we use Octo as a fixed generalist VLA backbone and build our method on top of its latent representation; the same method can be used with other VLA models.

Although VLA models can perform a wide range of tasks, they are typically used in a purely reactive way: at each step, the model receives the current observation and instruction and outputs the next action (or action chunk), without explicit long-horizon planning. In challenging scenes or out-of-distribution configurations, this can lead to failures that the policy does not recover from . In the language modeling paradigm, many methods have been introduced to mitigate similar issues by scaling test-time compute, such as chain-of-thought prompting , self-consistency sampling , and MCTS during inference .

extend these ideas to the robotics domain to address the limitations of reactive execution. They introduced Vision-Language-Action Planning and Search (VLAPS), which embeds a pre-trained VLA into a model-based search procedure and uses the VLA to define action proposals and abstractions for planning. In our work, we build on VLAPS and keep the same fixed VLA backbone, but additionally learn a value function over its latent state and incorporate the resulting value predictions into VLAPS’s scoring rule to guide the search.

startsectionsubsection2@-1.8ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex0.8ex plus .2ex

Monte Carlo Tree Search

A natural way to compensate for the myopic behaviour of reactive policies is to add a search procedure that can simulate possible future outcomes before committing to an action. Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) is a widely used algorithm for this purpose. It incrementally builds a search tree by repeatedly simulating trajectories from the current state, and at each iteration it selects actions that balance exploring uncertain branches with exploiting branches that have produced good returns in previous simulations . Typically, each iteration proceeds through four phases: selection, expansion, simulation, and backpropagation. The resulting statistics over node visit counts and returns are then used to estimate action values at the root.

MCTS has been particularly successful in domains where a reasonably accurate simulator is available. In board games such as Go, Chess, and Shogi, MCTS combined with learned policies and values has led to systems that reach and surpass human expert performance . In these settings, the search runs entirely in simulation and only the final chosen move is executed in the real environment. bring this style of planning to vision–language–action models in the VLAPS framework. They use MCTS over discrete action chunks, with a pre-trained VLA policy providing action priors that focus and refine the search of an otherwise completely intractable space. Their formulation combines their VLA-informed prior with visit-count-based exploration heuristics in a PUCT-style scoring rule which allows MCTS to exploit the strengths of the pre-trained policy while still exploring alternative action sequences.

startsectionsubsection2@-1.8ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex0.8ex plus .2ex

Learned Value Functions for Tree Search and VLA Planning

Combining learned value functions with tree search has proved highly effective in domains where planning is possible. In AlphaGo and its successors, deep neural networks predict both a policy over moves and a scalar value estimate from a board position; Monte Carlo Tree Search uses the policy to prioritize promising actions and the value to evaluate leaf nodes without long rollouts . This combination allows the search procedure to concentrate computation on moves that are both likely under the learned policy and lead to positions that the value function predicts as strong, rather than relying solely on visit counts and simulation outcomes of intractably long rollouts.

VLAPS adopts a similar strategy for vision–language–action policies, but stops short of learning an explicit value function over the VLA latent state. In , the quality of a node is determined by search statistics and VLA-derived action priors, but there is no separate learned estimate of how good it is to be at a particular state. In contrast, we keep the underlying VLA and search procedure fixed, and introduce a small value head which takes the VLA latent state as input. This head is trained to predict Monte Carlo returns from VLA rollouts, and its predictions are incorporated into the VLAPS selection rule. Conceptually, this brings the use of value functions in VLAPS closer to the value-guided tree search used in game-playing systems like AlphaGo, while operating in the setting of vision–language–action control.

startsection section1@-2.0ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex1.5ex plus 0.3ex minus0.2ex

Methodology

We extended VLAPS by learning a value function over Octo latent states and using this value to guide Monte Carlo Tree Search. We first collected rollouts of the Octo model and computed Monte Carlo value targets for each state ([sub:data_collection]). We then trained a three-layer MLP (the “value head”) to predict these targets from Octo’s last-layer representation (readout) ([sub:value_training]). Finally, we integrated the learned value into VLAPS’ tree search by modifying the node selection score to bias branches towards high-value nodes ([sub:value_integration]).

startsectionsubsection2@-1.8ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex0.8ex plus .2ex

Data Collection We construct training data for the value head by rolling out a fixed pretrained VLA policy, without any planning, on LIBERO tabletop manipulation tasks. At the beginning of each episode, the environment provides an initial observation $`o_0`$ and a language instruction $`g`$. At each decision step t, the VLA (Octo) receives $`(o_t,g)`$, computes a latent readout vector $`h_t \in \mathbb{R}^d`$ which acts as the summary representation of the past observations and the task. It then uses the readout to output an action chunk $`c_t`$, which consists of a sequence of low-level actions. We execute the entire chunk $`c_t`$ in the environment, applying each low-level action in order, until the chunk finishes or the episode terminates. The environment then returns the next observation $`o_{t+1}`$, and we query the VLA again. This produces an episode as a sequence of decision steps $`(o_0, c_0, o_1, c_1, ..., o_T)`$.

Episodes terminate either when the task is successfully completed or when a timeout horizon is reached. We use a sparse terminal reward: if the task is successfully completed before the timeout, the episode receives a terminal reward of 1; otherwise (failure or timeout), it receives a terminal reward of 0. All intermediate rewards are zero. Thus each episode has a binary outcome indicating success or failure.

For each decision step t in an episode, we define a Monte Carlo value target by propagating the terminal reward backward through time. Let $`R \in \{0,1\}`$ denote the terminal reward for the episode and let $`T`$ be the index of the final decision step. We assign each state at decision step $`t`$ a target:

G_t =

\begin{cases}

\gamma^{T - t}, & \text{if the episode ends in success } (R = 1), \\

0, & \text{if the episode ends in failure } (R = 0).

\end{cases}where $`\gamma \in (0,1]`$ is a discount factor (we set it to 0.99). This target can be interpreted as a Monte Carlo estimate of the state value under our sparse success reward when following the VLA policy.

We extract the readout vector and pair it with its value target to obtain training examples $`(h_t, G_t)`$. Aggregating these pairs across many VLA rollouts yields a dataset of state–value examples that we use to train the value head.

startsectionsubsection2@-1.8ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex0.8ex plus .2ex

Value Head Training Our goal is to learn a value function that maps the VLA’s latent representation at each decision step to the scalar value target defined in Section 3.1. Concretely, given the Octo readout vector $`h_t \in \mathbb{R}^d`$ at decision step t, we learn a function $`V_\theta : \mathbb{R}^d \to \mathbb{R}`$ that predicts a scalar estimate $`\hat{v}_t`$ of the state value: $`\hat{v}_t = V_\theta(h_t)`$.

We parameterize $`V_\theta`$ as a lightweight three-layer multilayer perceptron (MLP). The architecture is intentionally small compared to the underlying Octo model, so that evaluating the value head adds minimal overhead during planning.

We train this value head on the dataset of readout–value pairs $`\{(h_t, G_t)\}`$. The training objective is to regress onto the Monte Carlo value targets $`G_t`$ using mean squared error: $`\mathcal{L}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{(h_t, G_t)} \bigl[(V_\theta(h_t) - G_t)^2\bigr]`$.

In practice, we approximate this expectation by sampling mini-batches from the dataset and performing stochastic gradient descent with the Adam optimizer. During training, the parameters of the underlying Octo VLA are kept fixed; only the value head parameters $`\theta`$ are updated. After convergence, $`V_\theta`$ provides a compact estimate of the state value at each decision step, which we use to guide the tree search.

startsectionsubsection2@-1.8ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex0.8ex plus .2ex

Value Integration After training our MLP, we defined a PUCT style score for selecting nodes in Monte Carlo Tree Search . This amounts to using a selection score with the following form, for a given node-action pair $`(v,a)`$:

\begin{align}

\mathrm{PUCT}(v,a)= Q(v,a) + U(v,a)

\end{align}Following , we defined the $`U`$ portion of this score by:

\begin{align}

\label{eq:VLAPS-Score}

U(v, a^i) = \mathrm{VLAPS\_SCORE}(v, a^i) = \psi_{\Phi_v}\!\left(a^i \mid I_t, L_\mathcal{T}\right) \frac{\sqrt{N(v, a^i)}}{1 + N(v, a^i)}

\end{align}where $`v, a^i`$ are the current node and $`i`$th sampled action chunk from the VLA defined distribution $`\beta_{\Phi}`$ and $`L_\mathcal{T}, I_t, N(v, a^i)`$ are the task description, observation at time $`t`$, and number of times the $`i`$th action has been taken from the node $`v`$. The distribution $`\beta_{\Phi}`$ is a softmax centred around a sampled action chunk from the VLA of action chunks using the flattened euclidean distances from action chunks in a preset, finite library; $`\psi_{\Phi_v}\!\left(a^i \mid I_t, L_\mathcal{T}\right)`$ is defined similarly but using the candidate actions sampled from the distribution described above instead of the whole library.

The $`Q`$ portion of our score is then defined using our value estimator:

\begin{align}

Q(v, a^i) = V_\theta\left(h\right)

\end{align}where $`V_\theta`$ is our value estimator parametrized by $`\theta`$, and $`h`$ is the VLA’s transformer outputs of state information i.e. observations, task description at the state reached by taking $`a^i`$. We use a value function approximation as opposed to a state-action value function ($`V`$ vs. $`Q`$) because in this setup, transitions are deterministic. Taken altogether, the selection score is as follows:

\begin{align}

\mathrm{SCORE}(v, a^i, s') = \widehat v_\theta\left(\mathrm{readout}(s')\right) + \psi_{\Phi_v}\!\left(a^i \mid I_t, L_\mathcal{T}\right) \frac{\sqrt{N(v, a^i)}}{1 + N(v, a^i)}

\end{align}We then use this score to select nodes to expand, or in the case that they are already expanded, expand their subtrees.

startsection section1@-2.0ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex1.5ex plus 0.3ex minus0.2ex

Experiments and Results

startsectionsubsection2@-1.8ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex0.8ex plus .2ex

Dataset and Training Setup Using the method described in Section [sub:data_collection], we collected readout–value pairs across multiple LIBERO tasks. Specifically, we collected training data for tasks 1, 6, and 8 from the spatial suite, and tasks 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 from the object suite. LIBERO Object tasks primarily test object-centric manipulation: the robot must pick up a specified object and place it into a basket. LIBERO Spatial tasks emphasize spatial reasoning: the robot must pick up a target object from a specified position and place it onto another target region, such as a plate. Interestingly, we observed some of these tasks are much harder for the VLA. For example object task 6 has around 0% success rate, resulting in highly imbalanced data. To prevent the value head from collapsing to always predicting zero, we applied class balancing by randomly downsampling failure states so that the number of successful and failed examples was equal. Table [tab:dataset_stats] summarizes the final dataset composition per task.

We trained three separate value heads on this dataset: one trained only on spatial tasks, one trained only on object tasks, and one trained jointly on both suites. This allows us to measure the extent to which value learning on one suite benefits the other.

startsectionsubsection2@-1.8ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex0.8ex plus .2ex

Quantitative Evaluation To evaluate whether the learned value improves planning quality, we compared the following models on both spatial and object LIBERO suites: the base VLA policy without planning, VLAPS without a learned value, V-VLAPS trained only on one suite, and V-VLAPS trained on both suites. To ensure a robust evaluation, we evaluated each method across 10 rollouts per initial state for all available initializations (0–9). As seen in Table [tab:libero_results], adding the value head increased the success rate by 5.2% for the spatial task suite and 2.8% for the object task suite. Table [tab:planning_metrics] demonstrates that the average number of MCTS simulations, how many times we started the search again from the root node, is also lower for V-VLAPS compared to VLAPS. Specifically, we observe 5% reduction for spatial suite and 14% for the object suite. Task 9 for the spatial suite is particularly interesting as it clearly highlights the benefit of adding a value head. This is an especially difficult task for Octo as it consistently fails across all different initial states. In this case, V-VLAPS performs 31% better than VLAPS while spending fewer iterations in MCTS. Importantly, our collected dataset did not include any example for task 9, which suggests that the learned value head generalized well across the tasks within the same suite. Interestingly, it seems like training on both tasks suites does not help with the performance. This raises the question of whether we should use one value head that generalizes over different tasks suites or whether we would need one value head per task suite; we further discuss this in Section [sec:conclusions_and_future_work].

startsectionsubsection2@-1.8ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex0.8ex plus .2ex

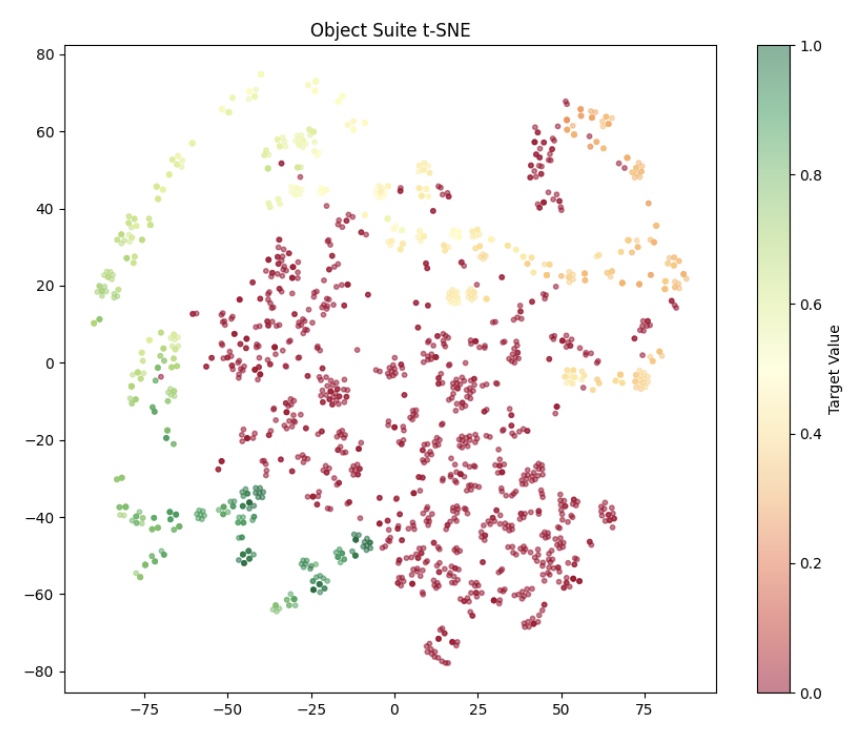

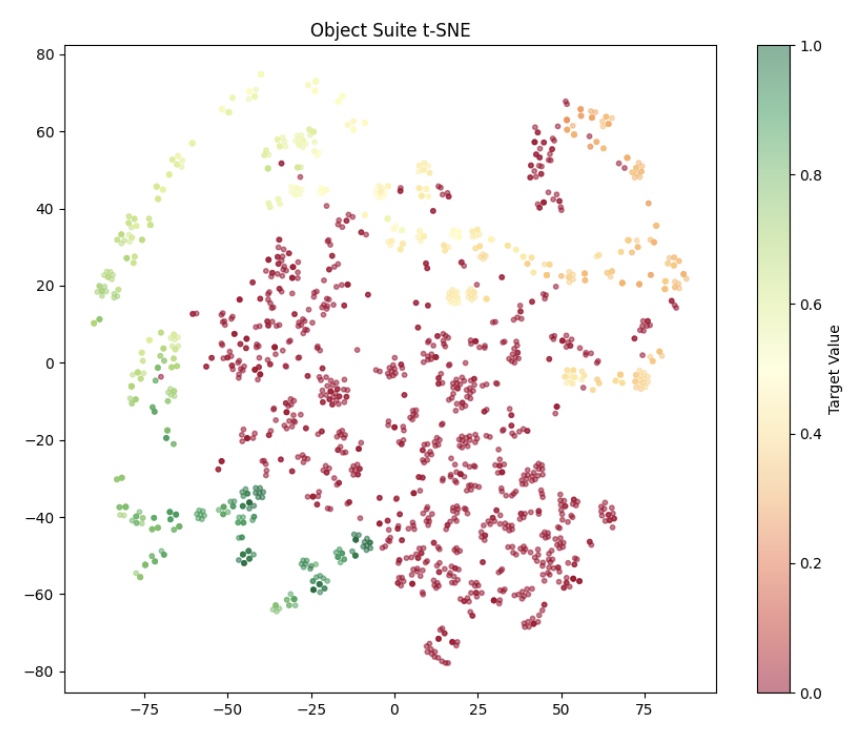

Qualitative Analysis Motivated by the performance gains we observed and by prior work suggesting a separation between success and failure latent representations in other VLA models , we analyzed the structure of Octo latent readouts. We projected readouts into two dimensions using t-SNE and inspected their distribution. Figure 2 visualizes this embedding and highlights differences between successful and unsuccessful trajectories. As seen, a very nice pattern emerges, where we can see the path that should be taken in this 2D space to go from the initial state to the target, suggesting the readouts may encode enough information to get an estimation for the expected reward.

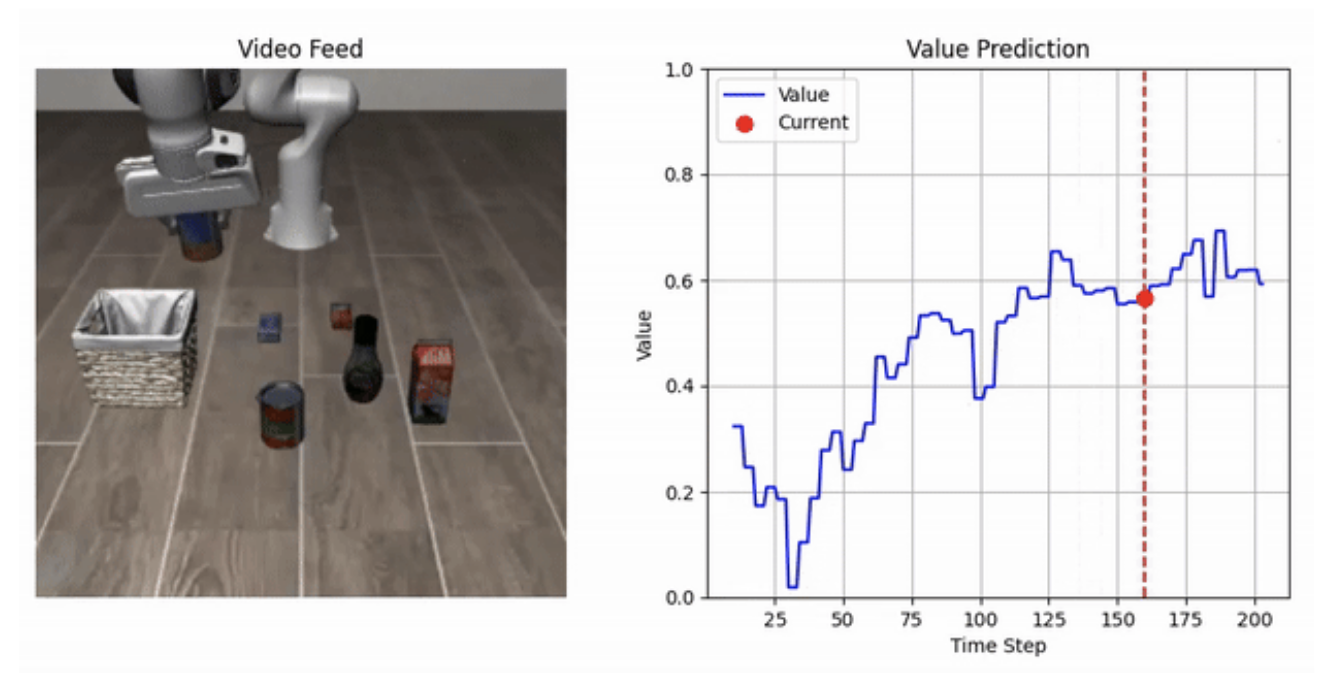

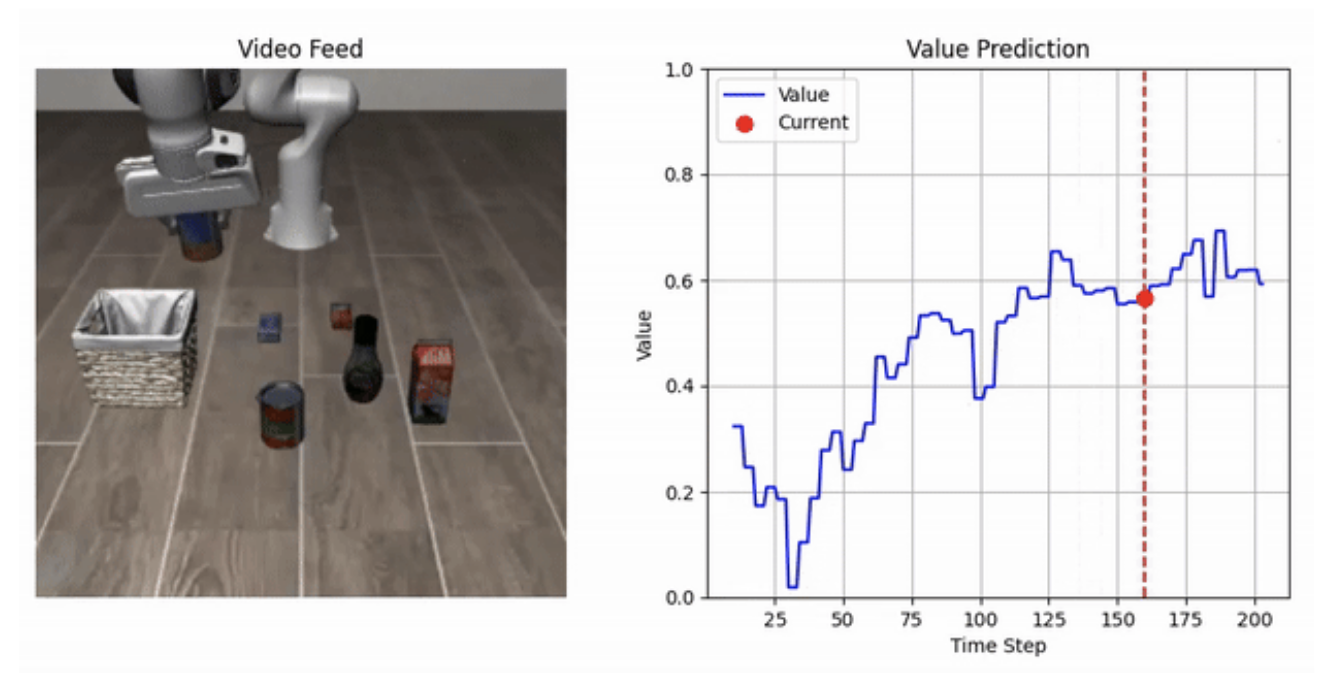

We also performed some qualitative analysis by visualizing the value estimations alongside corresponding rollouts. Figure 3 shows an example where the predicted value increases steadily as the robot approaches a successful completion state. Most of the learned values behaved meaningfully, although we observed occasional failures due to rare behaviors such as object drops. We expect this issue to diminish as we train on a larger and more diverse dataset that includes more tasks.

startsection section1@-2.0ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex1.5ex plus 0.3ex minus0.2ex

Discussion and Limitations Due to time and resource constraints, we could only test on tasks from two of the LIBERO task suites: Spatial and Object, and train on a subset of those. This setup naturally limits the ability of our value estimator to generalize effectively and limits the scope of our results to a more narrow class of tasks. Taking this into account, we were still able to achieve some improvement, and we hope to remedy these constraints in the future to iterate on these results.

The Octo VLA model comes with its own limitations. The data collected from episodes performed under the Octo VLA policy can be of poor quality, namely, on many tasks Octo either fails on all rollouts or succeeds on all rollouts. This uniformity makes it challenging to learn a general and interpretable value estimator with no reward signal. Once again, we still saw success and anticipate that if we collect data using a more sophisticated, guided approach, that we can see even better results. We see some structure in the readouts produced by the transformer on the Object suite, but less so in Spatial. Due to this, we also list the transformer readouts as a potential limitation as latent inputs to our value estimator. We might improve this by using a different VLA or passing a bigger observation context into the transformer. Finally, we will further investigate the generalization of our value head across task suites, training on single suites and multiple suites to assess the feasibility of training a generalist value estimator.

Lastly, like in , we must assume access to a realistic simulator/world model to carry out Monte Carlo tree search. Handling the inaccuracies that a simulator exhibits is an active area of research, and in the scope of this project, we do not address it; given the advancements in simulation accuracy and efficacy, we believe that this work can be extended to physical robotic tasks. Keeping with the theme of realism, the additional VLA calls that tree search requires are computationally expensive and time-consuming. We hope that improvements continue to be made in inference time and compute for VLA models and look forward to optimizing our current implementation for efficiency.

startsection section1@-2.0ex plus -0.5ex minus -.2ex1.5ex plus 0.3ex minus0.2ex

Conclusions and Future Work

We have presented V-VLAPS, a method that augments VLA-guided MCTS with a lightweight, learnable value estimator. Our results demonstrate that this simple, low-cost addition significantly improves planning efficiency and success rates by biasing the search toward high-return states.

Moving forward, we identify three key directions to enhance this framework. First, we aim to improve generalization by training on more diverse task suites. Specifically, we intend to analyze whether a single value head can effectively generalize across different domains or if task-specific estimators are required. Second, we plan to guide the data collection process using VLAPS. We hypothesize that training on search-generated data, rather than VLA rollouts, will yield more accurate value estimates and better test-time guidance. Finally, we intend to explore adaptive compute, using the learned value estimator to dynamically prune unpromising branches during rollouts, thereby allocating the search budget more efficiently.

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)