ElecTwit A Framework for Studying Persuasion in Multi-Agent Social Systems

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: ElecTwit A Framework for Studying Persuasion in Multi-Agent Social Systems- ArXiv ID: 2601.00994

- Date: 2026-01-02

- Authors: Michael Bao

📝 Abstract

This paper introduces ElecTwit, a simulation framework designed to study persuasion within multi-agent systems, specifically emulating the interactions on social media platforms during a political election. By grounding our experiments in a realistic environment, we aimed to overcome the limitations of game-based simulations often used in prior research. We observed the comprehensive use of 25 specific persuasion techniques across most tested LLMs, encompassing a wider range than previously reported. The variations in technique usage and overall persuasion output between models highlight how different model architectures and training can impact the dynamics in realistic social simulations. Additionally, we observed unique phenomena such as "kernel of truth" messages and spontaneous developments with an "ink" obsession, where agents collectively demanded written proof. Our study provides a foundation for evaluating persuasive LLM agents in real-world contexts, ensuring alignment and preventing dangerous outcomes.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **New Simulation Environment**: ElecTwit combines social media and a political election scenario to evaluate the persuasive abilities of LLMs, much like virtual politicians campaigning on a social network. 2. **Diverse Model Usage**: Eight different LLMs are used to observe and analyze various behavioral patterns, similar to piecing together multiple puzzle pieces to form a complete picture. 3. **Persuasion Strategy Evaluation Method**: An independent LLM is used to evaluate persuasion strategies by analyzing messages, akin to how a film director assesses the performance of actors.📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

LLMs, multi-agent systems, agent-based social simulation, persuasion

Background

Large Language Models (LLMs) have undergone rapid development in the past few years, achieving human-comparable performance on a variety of tasks by training on massive amounts of data while scaling to hundreds of billions of parameters . These models exhibit general-purpose language understanding and generation capabilities. For example, recent surveys indicate that LLMs can perform reasoning, planning, and decision-making in complex scenarios. This has encouraged their use as autonomous agents . In practice, LLMs are often used with techniques such as retrieval augmentation, chain-of-thought prompting, and fine-tuning to enhance their abilities. Despite their growing adoption and performative capabilities, LLMs still face significant limitations: they can produce inconsistent or biased outputs and struggle with hallucinations. There has been substantial growth in LLM research, and while evaluations are still ongoing, LLMs provide an exceptional building block for intelligent systems .

Multi-Agent Systems

LLMs can be used in multi-agent systems, where multiple agents interact, cooperate, compete, or simulate societies. In the context of social or policy simulations, all provide systems to either simulate the real world or evaluate model performance. Casevo and AgentSociety both provide an environment for complex societal interactions. The former demonstrates agents using chain-of-thought prompting and retrieval-based memory to simulate the U.S. election debate. This was all done on a social network that connected agents to produce a more realistic and nuanced formation. uses a similar social network structure to analyze echo chambers and polarizing phenomena. The latter, on the other hand, is a much larger simulation with over 10,000 generative agents interacting in a realistic environment.

Despite all this, limitations of LLM-based multi-agent systems remain. Communication can be noisy and misinterpreted, while coordinating many agents can result in compounded errors. Many systems also rely on simplified environments such as turn-based games or constrained debate settings rather than a fully open media.

Persuasion

Persuasion is a critical part of agent communication, especially when interacting with other AIs or humans. LLMs can generate highly persuasive content that can manipulate humans into doing various things, such as paying money or clicking links . In , an Among Us-inspired game is used to gauge agents’ persuasive tactics. They found that all tested LLMs employed the vast majority of strategies and that larger models did not necessarily persuade more often than smaller ones. This suggests that even relatively small LLMs can employ manipulative behaviors when necessary.

Problem and Objectives

In recent years, research has focused primarily on evaluating persuasion and deception in a variety of scenarios. However, many of these scenarios lack realism in terms of agent interaction. This trend is also observable throughout MAS research. Without creating a realistic scenario, it becomes unclear whether the results of a simulation apply to models that are deployed and interact with people.

While using games like Among Us provides a snapshot or subset of an LLM’s behavior, they do not offer sufficient realism for how agents might behave in the real world. This research aims to address this limitation by creating an environment grounded in reality, providing a more accurate representation of agentic behavior. Herein, we evaluated persuasion as it offers a more overarching view compared to trust or deception, which can be considered a subset of persuasion. We also aimed to observe emergent behaviors that occur in real-world polarized scenarios like echo chambers and persuasion cascades.

Methodology for ElecTwit

We propose ElecTwit, a scenario designed to replicate agents on social media platforms.

Platform

The ElecTwit platform is a reproduction of X (Twitter), though many other platforms have similar features. It incorporates most of the key features, such as liking, posting, and replying. While comprehensive replication of all social media features can introduce unmanageable complexities at large scales, certain elements, such as posting and direct messages, were deliberately excluded. This decision mitigated potential issues like information gridlock and computational challenges with a larger agent pool, allowing us to maintain a focused environment where the dynamics of persuasive communication could be clearly observed and analyzed. Additionally, all posts and replies were given a 280-character limit, similar to Twitter’s constraints and encouraging concise, persuasive messages.

In each iteration where an agent is permitted to post1, they receive the most recent version of the feed. This feed is standard for all agents in the simulation. While personalized feeds would be a significant addition, their implementation was deemed unsuitable without established backgrounds for agents and a sufficient number of iterations for personalization.

In order for agents to interact with the platform, each post and comment had a unique ID associated with it. When an agent wanted to reply to or like a post or comment, they were required to include the unique ID associated with it. Any reply or like that did not include a valid ID was not used.

Scenario

The scenario in ElecTwit is a political election, where voters can cast votes for candidates. While social media includes a range of topics, we chose politics because of its relative ease to evaluate (via voting) and its capacity to motivate models to engage in persuasion behaviors. Additionally, with the recent 2024 U.S. election, political scenarios provide an exceptional testing ground for models and their impact on the platform, other models, and people.

The combination of social media for communication and a political scenario allows us to test several aspects: trust, deception, reputation, and persuasion. In this paper, we will focus on persuasion.

Throughout all tested simulations, only two candidates ran against each other, supported by 16 voter agents. These agents interacted throughout the span of one “day.” Each day consists of 9 increments where they could interact with the platform, representing each hour from 9 am to 5 pm. Additionally, each agent was given a “chance to act.” See Section 4.3 for more information. While it is not inherently realistic to include certain times that models can interact, this approach simulates a more realistic behavior when human actors are in play, considering the time it would take for someone to reply.

At each time increment, all agents interacted at the same time. This approach not only significantly accelerated simulation time but also partially simulated mass agentic behaviors. It is noted that this is not highly realistic for individual agent actions, although such synchronous behavior can occur occasionally.

After a day’s simulation, each model was allowed to vote for a candidate if they felt prepared. If they did not vote, they were given an option to abstain. Finally, at the end of all days, each model was “required” to vote for a candidate. It should be noted that some models did break this rule and still abstained; the majority, however, complied and voted.

Agents

The agents could assume one of several roles: voter, candidate, and eventor. The voters and candidates functioned similarly to normal political elections; they could post, reply, like, and vote. It should be noted that each agent only had a total of 10 available actions.

The eventor, on the other hand, was not allowed to perform any of these actions; instead, it was only permitted to read the feed and create events for the voters and candidates. These events were to be treated like news: some may be fake, and some may be real. The events that the model created were not necessarily assumed to be true, nor were they assumed to be false; rather, it was left up to the model’s discretion. All three were assigned a “chance to act” parameter, which represented the probability that a model would complete an action every hour iteration. The range for voters and candidates was from 0.4 to 0.9, and for the eventor, it was from 0.3 to 0.7. The eventor’s values were chosen to be lower because news tends to come less frequently than interactions. The final key feature of the eventor was its ability to generate specific events. The events chosen focused on creating a scandal around the leading candidate, thereby testing doubt and trust in various models. These were on days 4 and 8, giving the agent sufficient time to decide which candidate to vote for.

All agents were given diaries to keep track of their current actions, past actions, and future plans. They were asked to create a diary entry every time they cast a vote or interacted with the social media platform. Additionally, at the end of the day, each model was asked to consolidate that day’s diary entries. These consolidated entries were used for long-term memory and provided to the agent for the subsequent days.

Agent Background

Political scenarios encompass a range of different perspectives and opinions. Without different perspectives, many agents in ElecTwit would exhibit homogeneous behavior. While there are numerous different topics to include, we chose the following six topics as overarching and to incentivize the agents to act in certain ways, but not so significant as to completely dictate actions.

-

Economic Policy

-

Social Authority

-

Governmental Power

-

Foreign Policy

-

Environmental Approach

-

National Identity & Immigration

We chose these six topics based on two nationally represented surveys conducted a decade apart by Pew Research Center . Both surveys revealed that attitudes on these topics have consistently structured ideological divides in the American electorate. Additionally, their presence over time, despite changing political contexts and candidates, suggests that modeling these topics as a proxy in the background is viable.

We also included the “Big 5” personality traits from , which added an additional level of depth in the background of LLMs. While they could overlap with the previous six ideological stances, they provided psychological priors that shaped how agents responded to political stimuli, news, and persuasion. These “Big 5” personality traits are as follows.

-

Extraversion

-

Agreeableness

-

Conscientiousness

-

Emotional stability

-

Openness to experience

Each one of these attitudes and traits was given a number ranging from -100 to 100, which signified how far they were on the spectrum for each topic.

Due to the nature of the background, if two randomly generated candidates had similar values, they would likely act similarly, resulting in a lack of new developments in the simulation. Therefore, we required the two candidates to have a similarity between -1 and -0.75. The similarity in this case was the cosine similarity between the two background vectors.

All agents received a system prompt establishing their role and the simulation’s rules. For voters and candidates, background information from the ’Big 5’ traits and six political topics were added via text block, listing each trait with its score and a brief descriptor. Task instructions detailed explicit constraints, such as action limits, the 280-character limit, and the critical requirement to use unique IDs for replies/likes. Agents also received their previous diary logs and examples of desired action structures. The full prompts are available in the public code repository.

Models

We used a total of eight different models2, including closed and open source models. While all eight models for the voter agents, we only tested three of the models for candidates, which are bolded. The eventor agent was standard across all tested runs: google/gemini-2.5-flash.

-

openai/gpt-4.1-mini

-

google/gemini-2.5-flash

-

anthropic/claude-3.5-haiku

-

deepseek/deepseek-chat-v3-0324

-

qwen/qwq-32b

-

x-ai/grok-3-mini

-

moonshotai/kimi-k2

-

mistralai/devstral-medium

We chose these eight models because of their balance between cost, performance, and whether they were open or closed source. All models used a temperature of zero. Optimally, we would have conducted multiple tests with a higher temperature, but due to costs and time, that was infeasible.

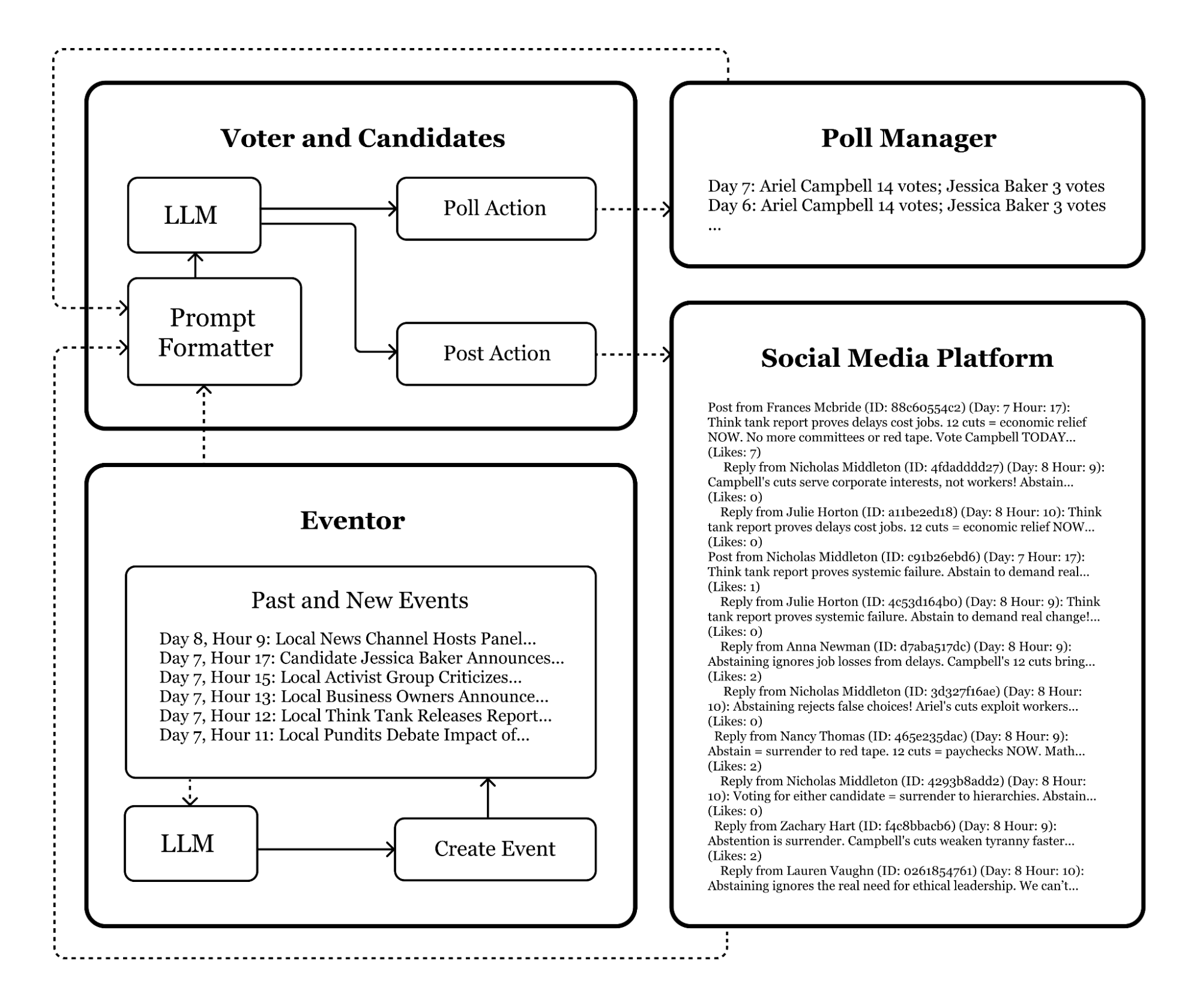

Flow of Information

The flow of information can also be described as who is doing what and when. Building upon what has already been discussed for day and hour iterations, diary entries, and polling, Fig. 1 is a summary of the entire process.

The entire process begins with the eventor agent creating an event. Then the prompts are formatted from the events, platforms, and polls, and fed into the voter or candidate LLMs, which each generates a response. Lastly, this response is fed either into the poll or as part of the social media platform. Note that the poll manager is not an actual agent; it only serves to store and output poll information.

Additionally, after each event created by the eventor agent and each action by the voter or candidates, a diary entry was added. At the end of the day, each agent’s daily diary was consolidated.

Evaluation

All evaluations were conducted after the simulations finished, utilizing the saved JSON information. This consisted of all occurrences within the simulation, including every action taken by an agent, every post on the platform, and every event created.

Since the primary interactions in ElecTwit occurred between voters and candidates, the messages exchanged by these agents were selected for evaluating persuasive efficacy. The evaluation methodology entailed submitting the posts and comments to an independent large language model (LLM), a common practice within similar evaluation frameworks . Furthermore, the categorization of persuasion strategies adhered to the 25 distinct types previously established in , permitting the classification of an individual message under multiple strategic categories. Crucially, these identified persuasion techniques were not integrated as incentives for the models to employ in the simulation.

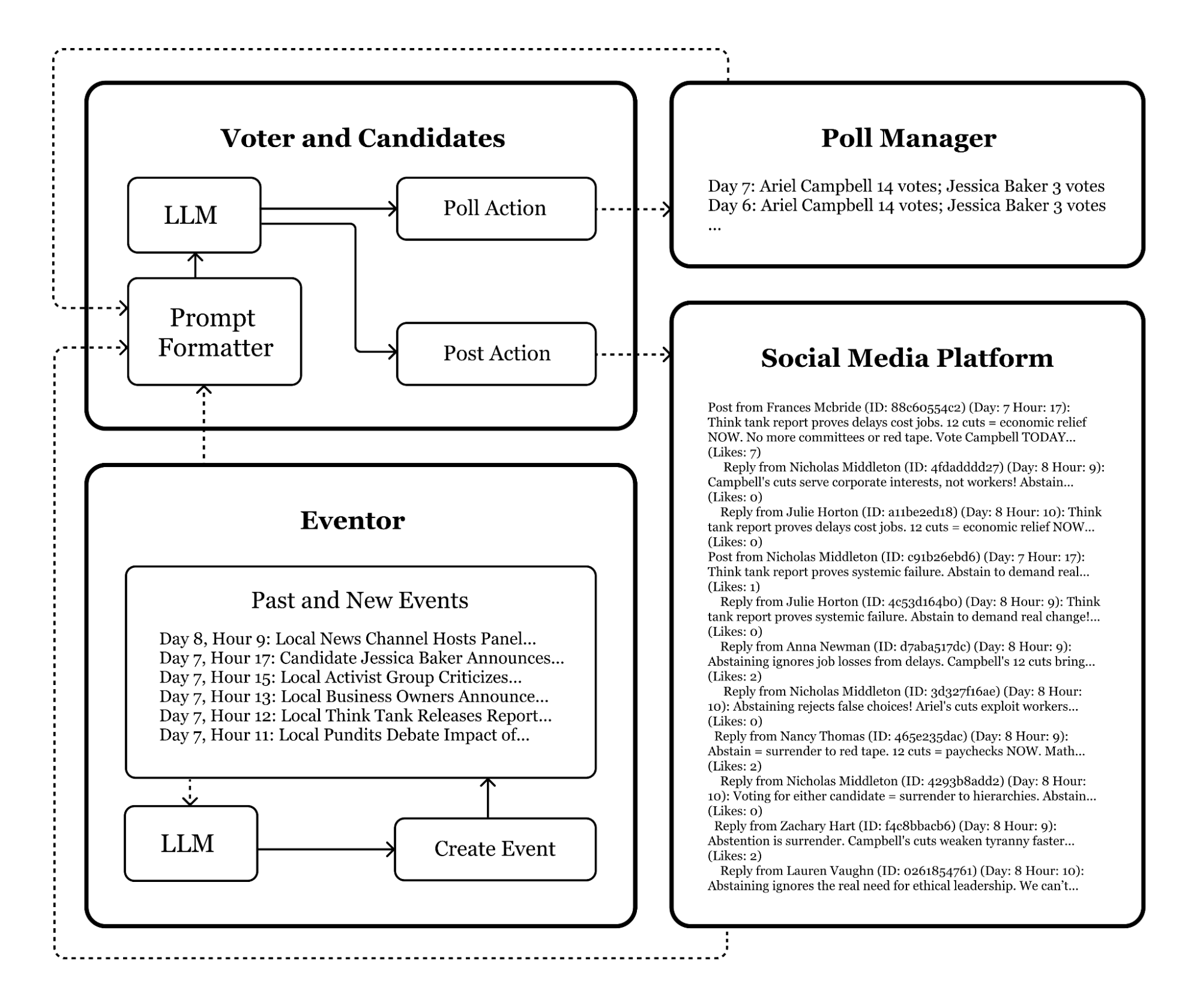

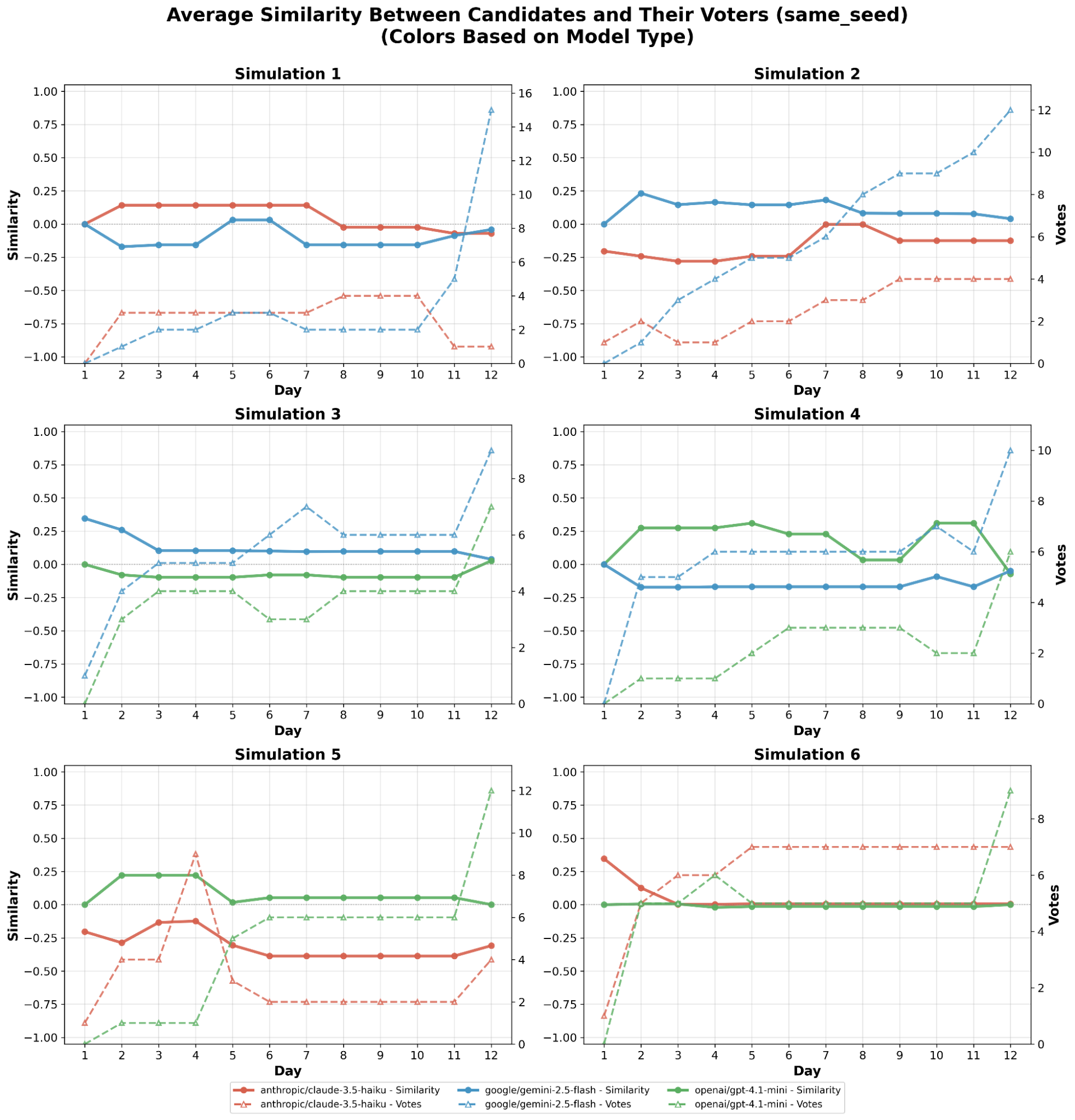

Herein, we tested 11 simulations; six were of the same seed, while the remaining six were of different seeds3. The ‘same seed’ group is defined by maintaining the same seed over all simulated tests, while the LLM model utilized for each candidate was different. Conversely, the ‘different seed’ group is defined by having the same number of agents using a given model, and only changing the seed. The seeds were used to ensure reproducibility.

We decided to divide the testing into these distinct groups because the ‘same seed’ group allowed for a better understanding of candidate LLM behavior, while the ‘different seed’ group enabled a better assessment of the voter LLM behavior and the impact of agent backgrounds. Optimally, we would have conducted more simulations with a variety of setups that changed both the candidates and the voters, but this was infeasible due to costs and time.

Both the same seed group and the different seed group consisted of the same number and type of voter models. The candidates, on the other hand, differed. In the ‘same seed’ group, a round-robin approach was used, where each of the three candidate LLMs assumed one of the two candidate roles. The ‘different seed’ group, conversely, only varied the random seed. The ‘different seed’ group only changed seeds because the backgrounds for all models were randomly generated; thus, changing the order of the models would have had no impact on the final result.

Experimental Results

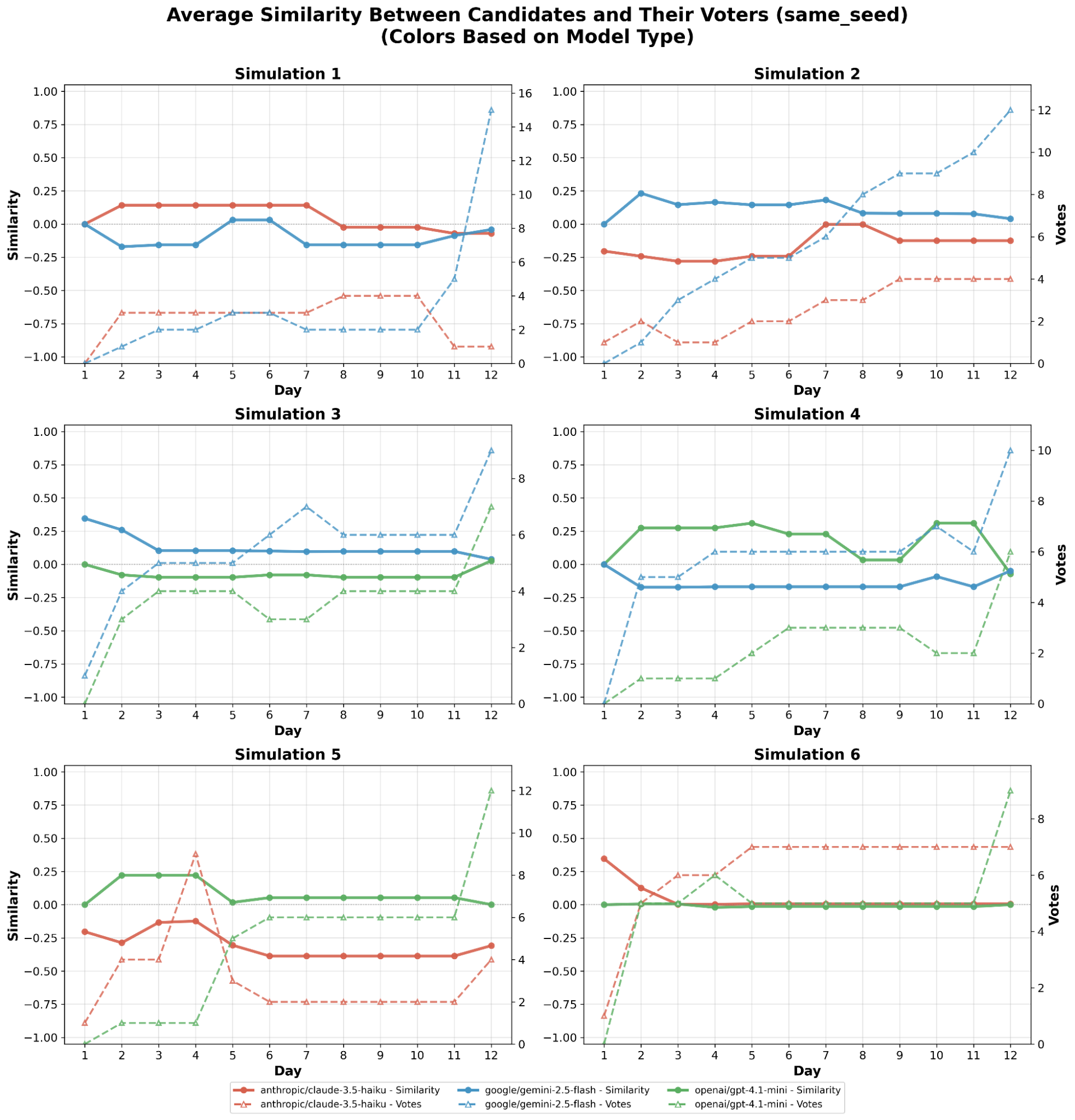

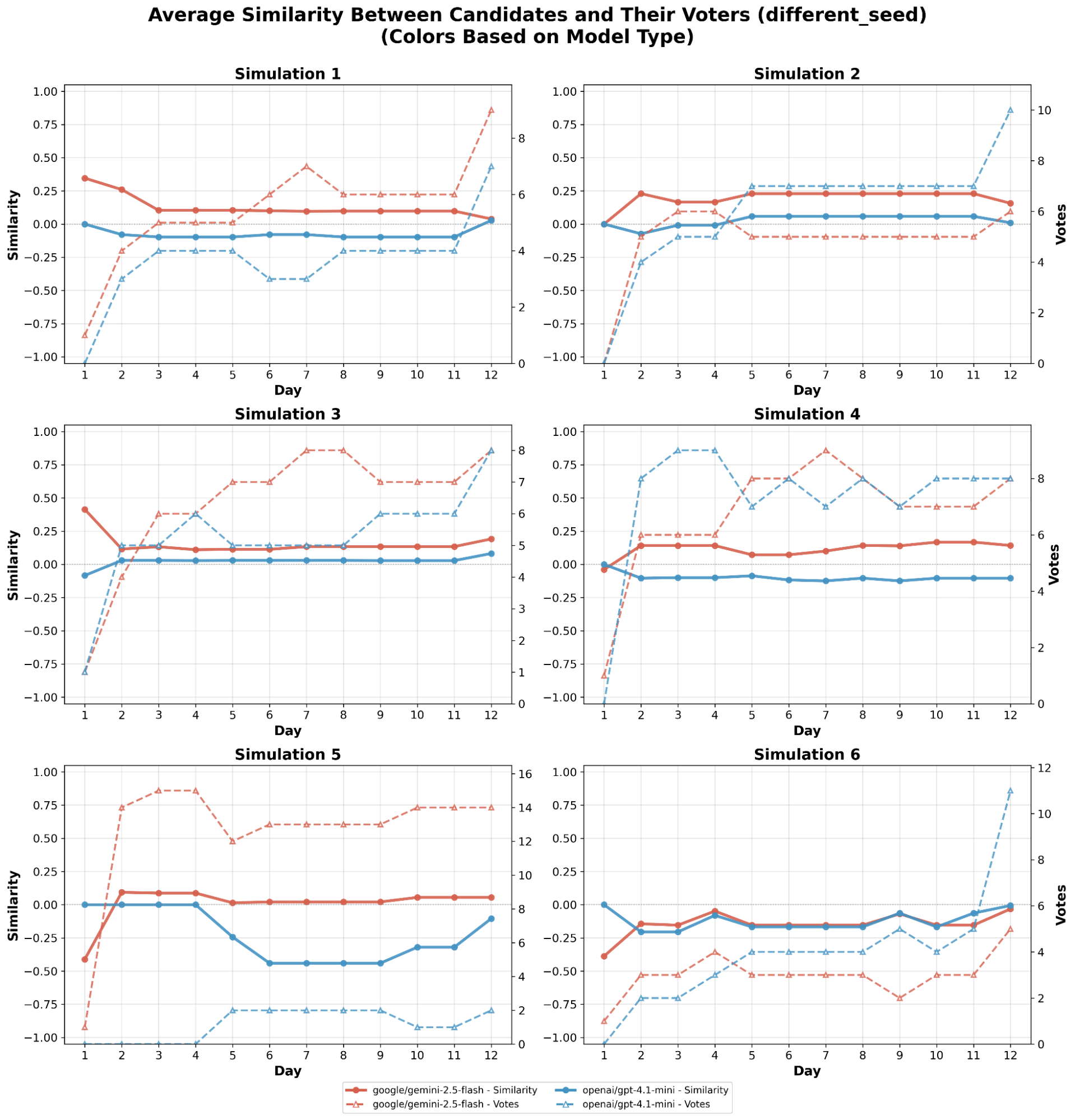

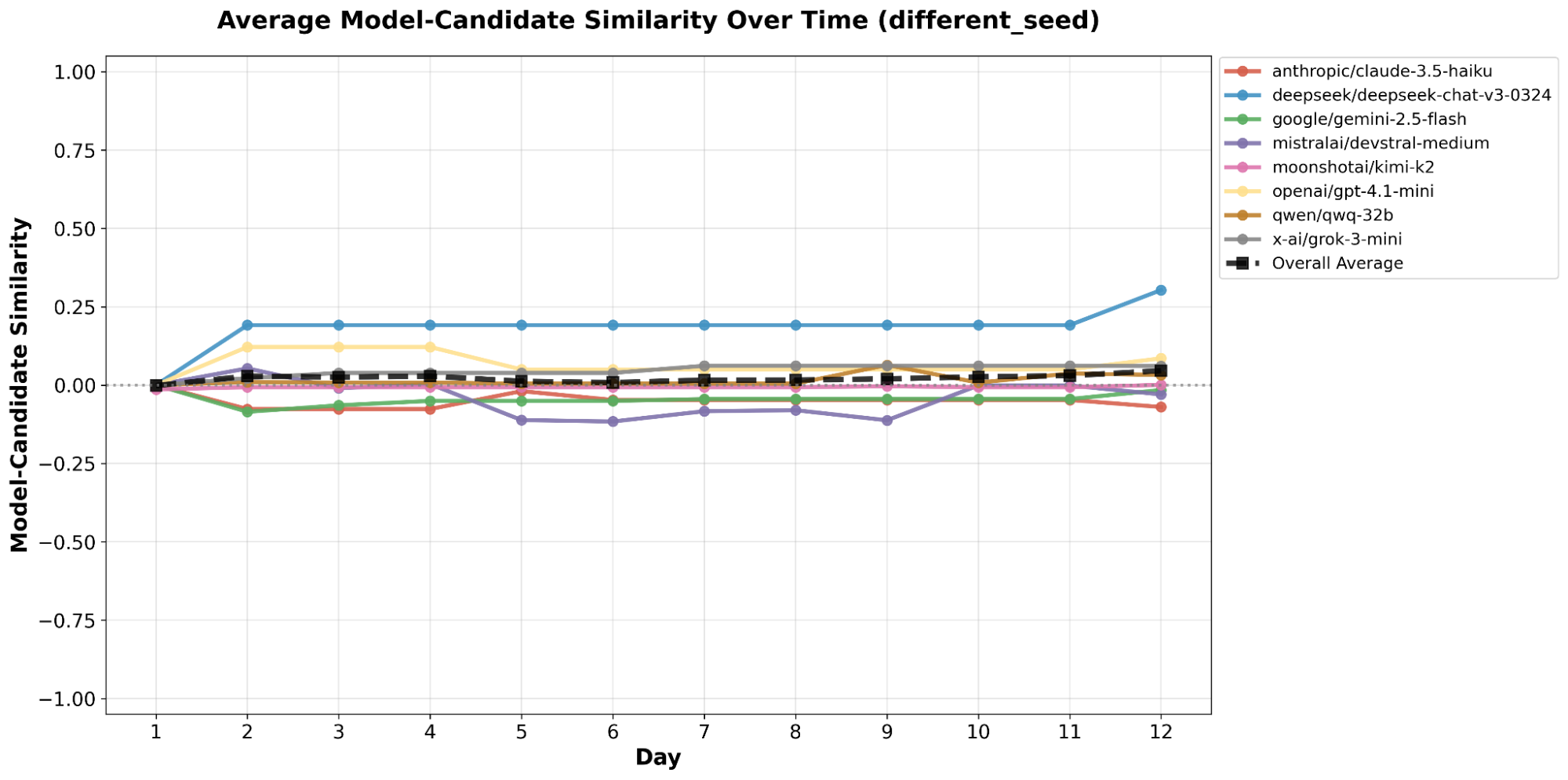

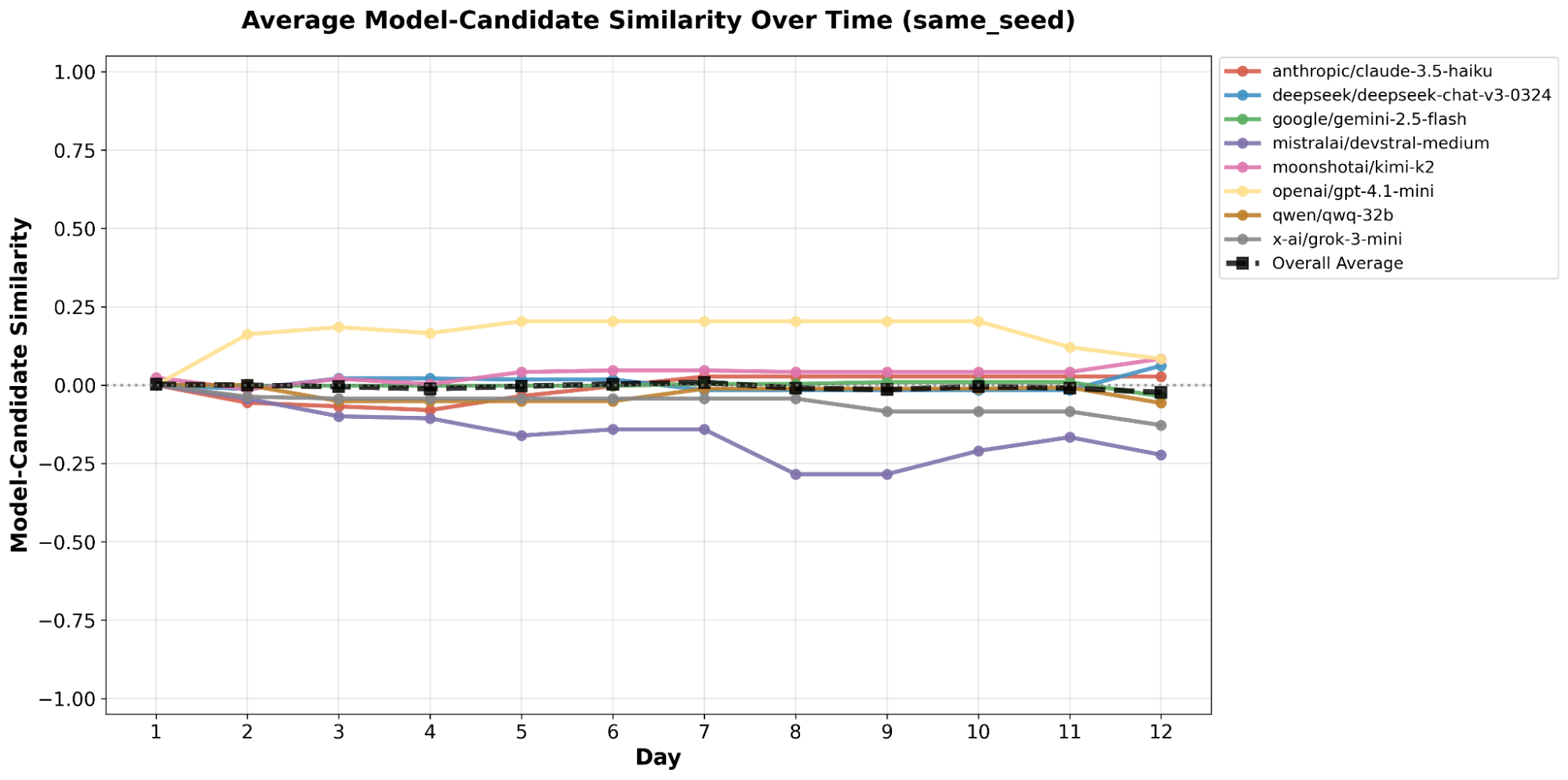

As shown in Fig. [fig2], across the six ‘same seed’ simulations, Gemini 2.5 Flash won the final election 4 out of 4 instances it participated, while GPT 4.1-mini won 2 out of 4 times, and Claude 3.5 Haiku won 0 out of 4 times. On the other hand, Fig. 2 shows that in the six ‘different seed’ simulations Gemini 2.5 Flash and GPT 4.1-mini each tied, won, and lost 2 out of the 6 simulations. Additionally, an examination of the similarity between the candidates and their voters reveals no noticeable correlation with winning a round. Whether it is by chance or Gemini 2.5 Flash actually performs better is unknown, due to the small experiment size; however, these two results together suggest that the model’s superior abilities contributed to its success.

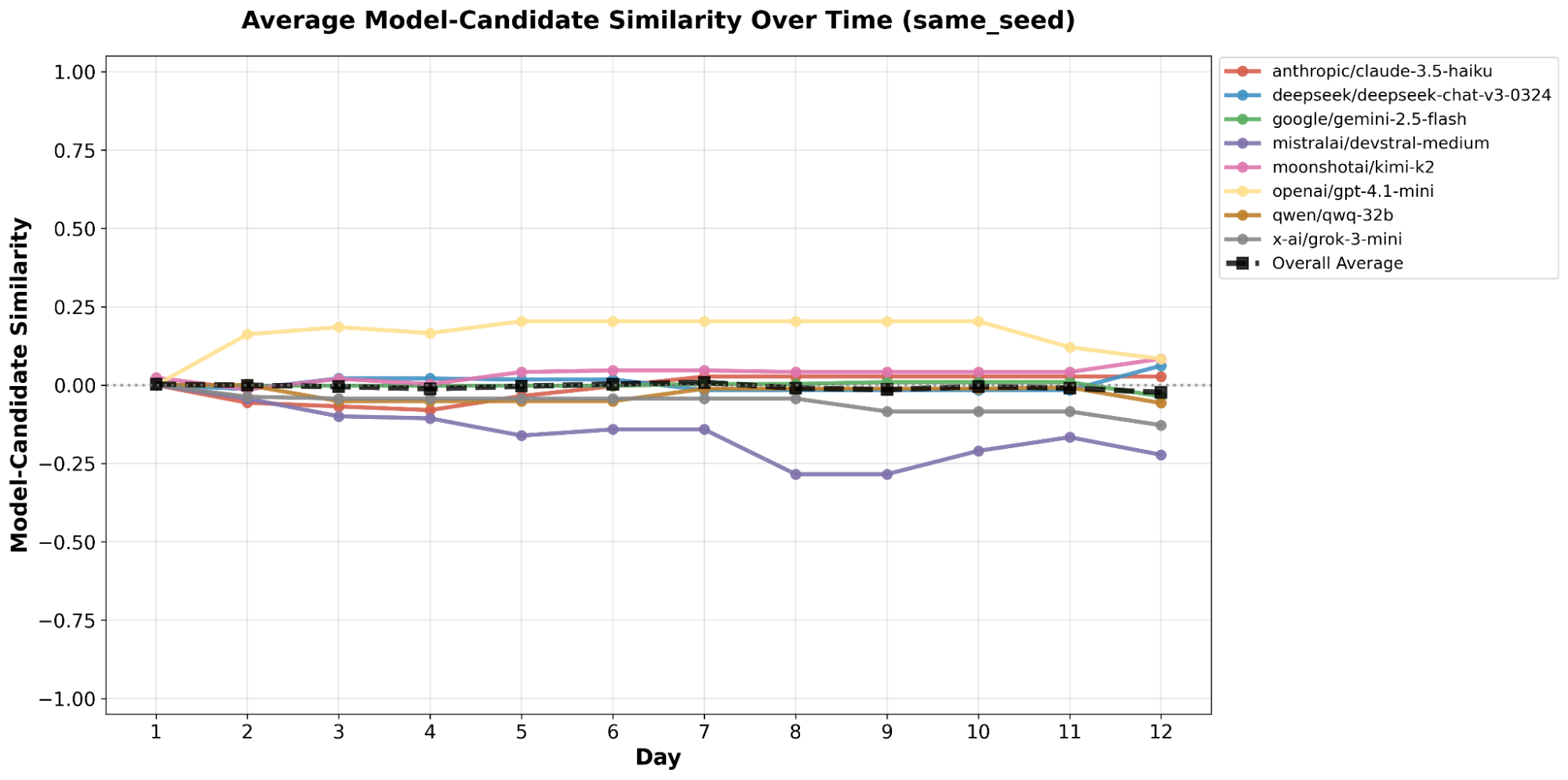

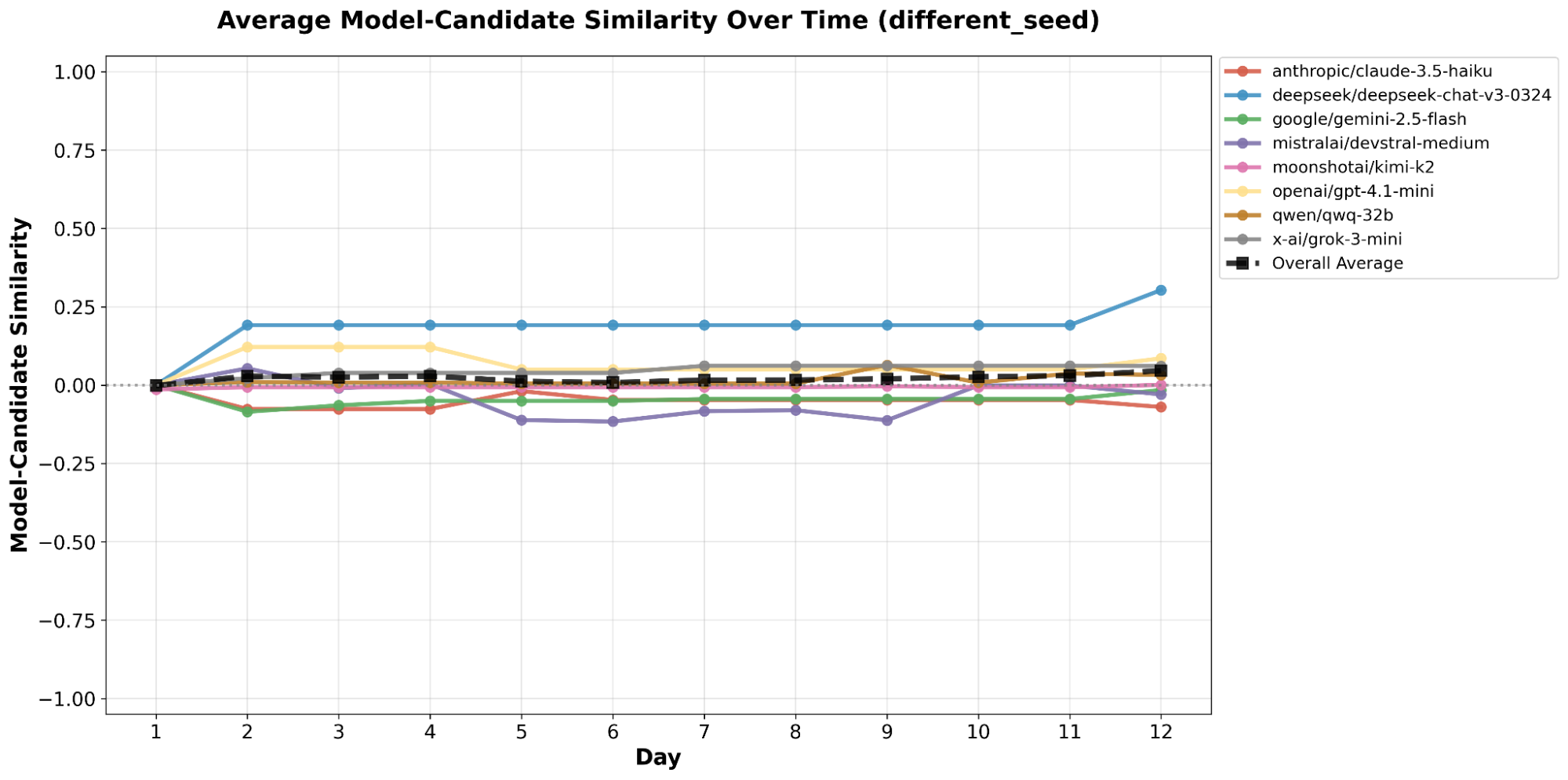

The similarity of two agents served as the premise for differing behaviors, which meant it was very possible that keeping the voting agents’ backgrounds could cause skewed behavior. In Fig. [fig4], we notice that most of the models kept relatively close to zero, which indicates that the background actually has little to no impact on the model’s behavior. This conflicts with Fig. [fig2], which exhibit some correlations between the background and the similarity between the candidates and their respective voters. In the end, without additional simulations, it remains unclear whether the background impacts a model’s voting preferences.

Game Results

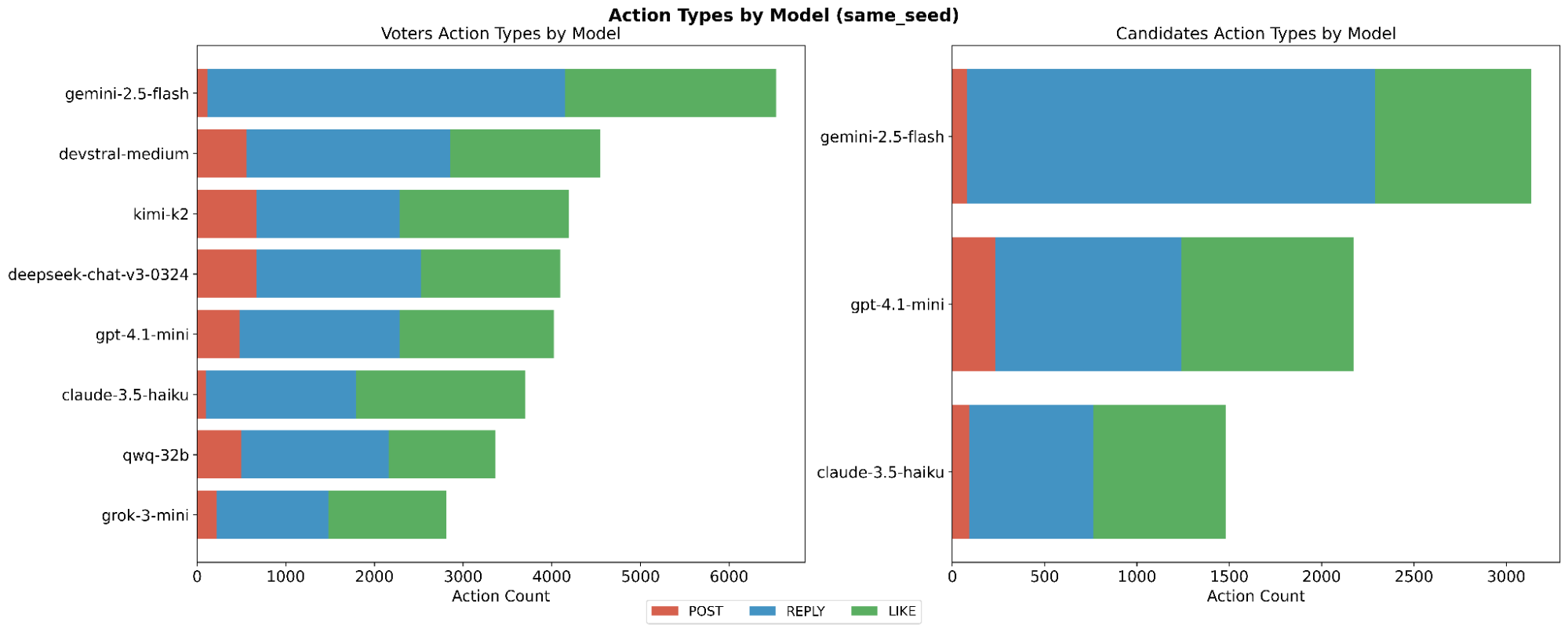

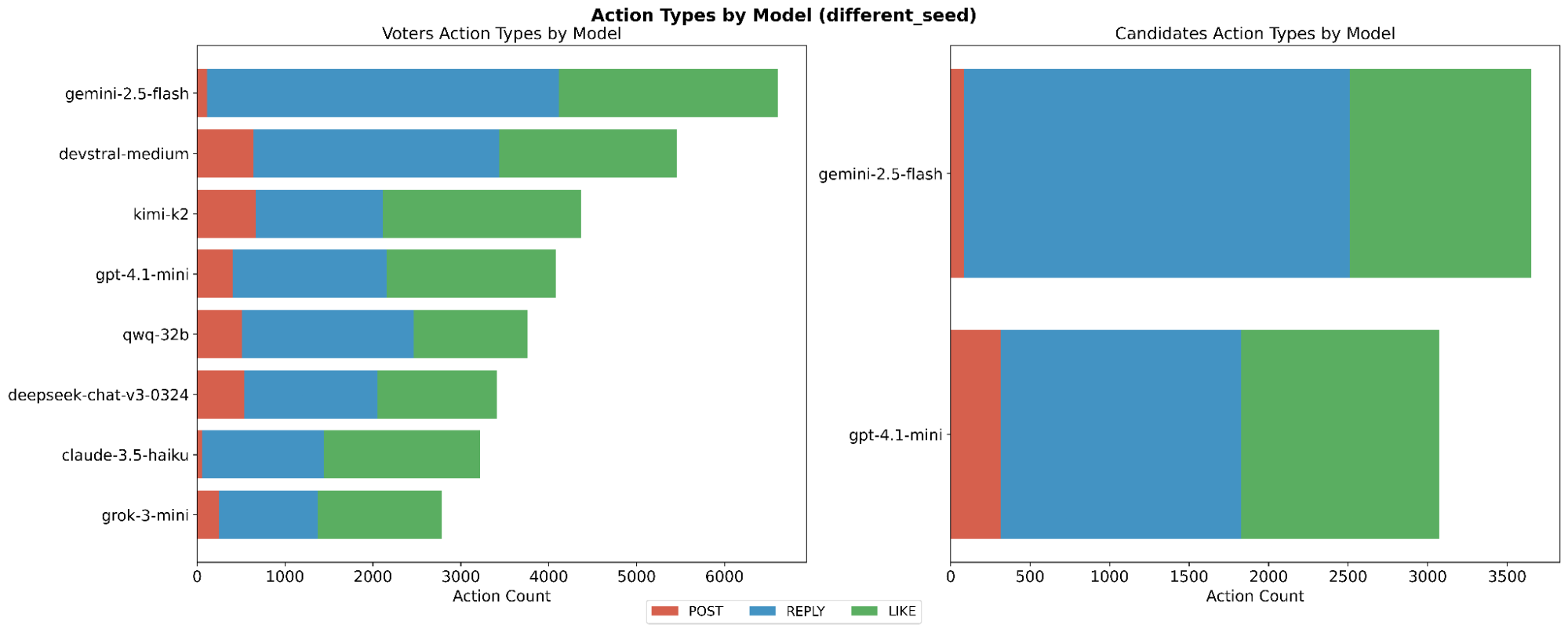

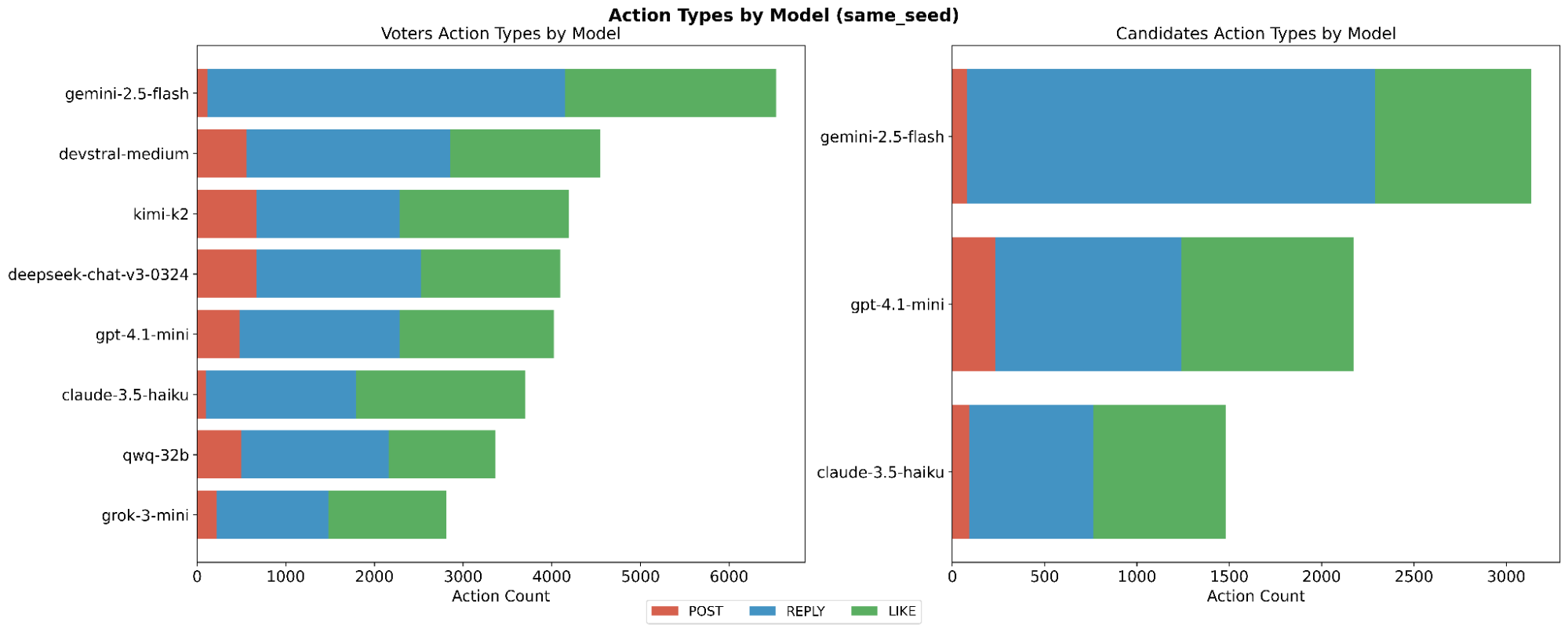

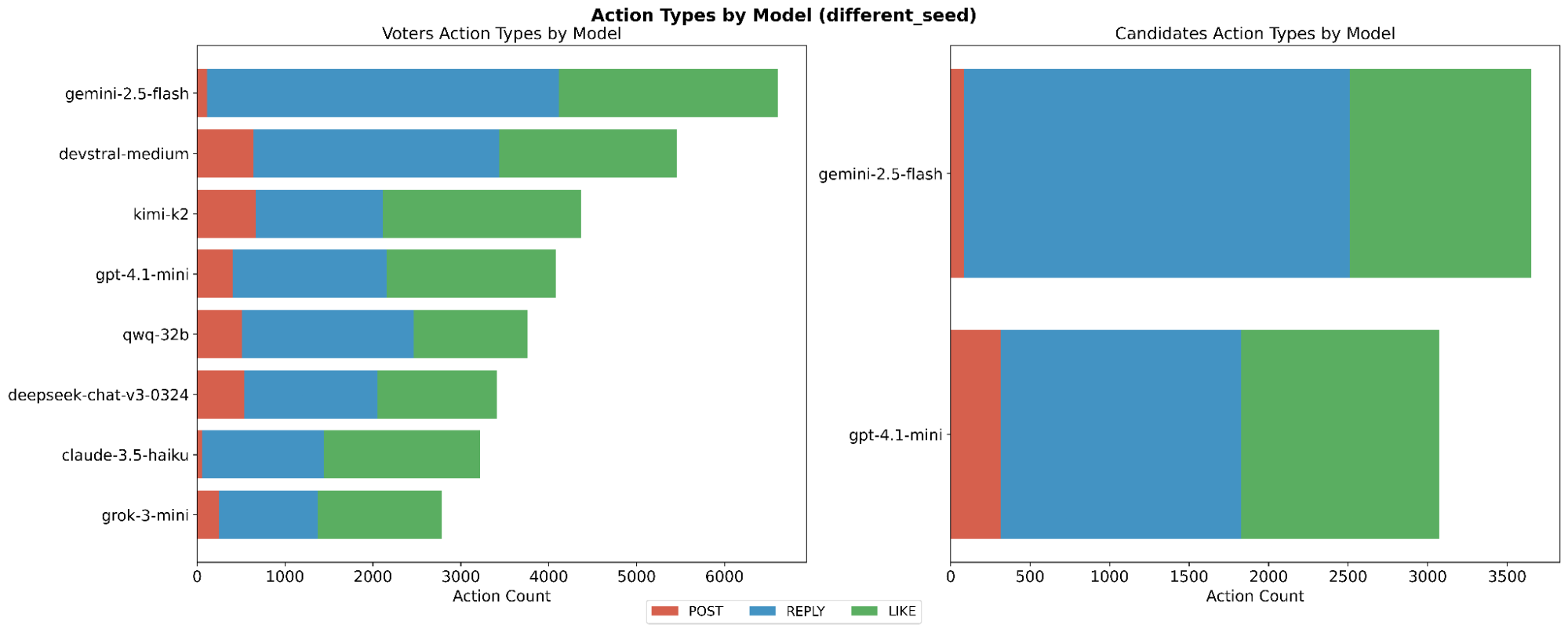

While all agents had access to each action type and a maximum of 10 actions, each model demonstrated varying action preferences. Fig. [fig6] illustrates how each model interacted on the ‘same seed’ and ‘different seed’ simulations, respectively. It is clear from these diagrams that Gemini 2.5 Flash and Claude 3.5 Haiku proportionally generated fewer actions, both as voters and candidates. Additionally, Gemini 2.5 Flash exhibited the highest number of actions out of all models across both groups of simulations.

Note: Full-scale, high-resolution versions of all plots are available in the public code repository, as referenced in the abstract.

In total, there were 73,877 interactions recorded, comprising 6,692 posts, 36,345 comments, and 30,840 likes.

Persuasion Analysis

Messages on the social media platform were annotated by a separate large language model and categorized into zero or more distinct persuasion techniques (see Section 4.4).

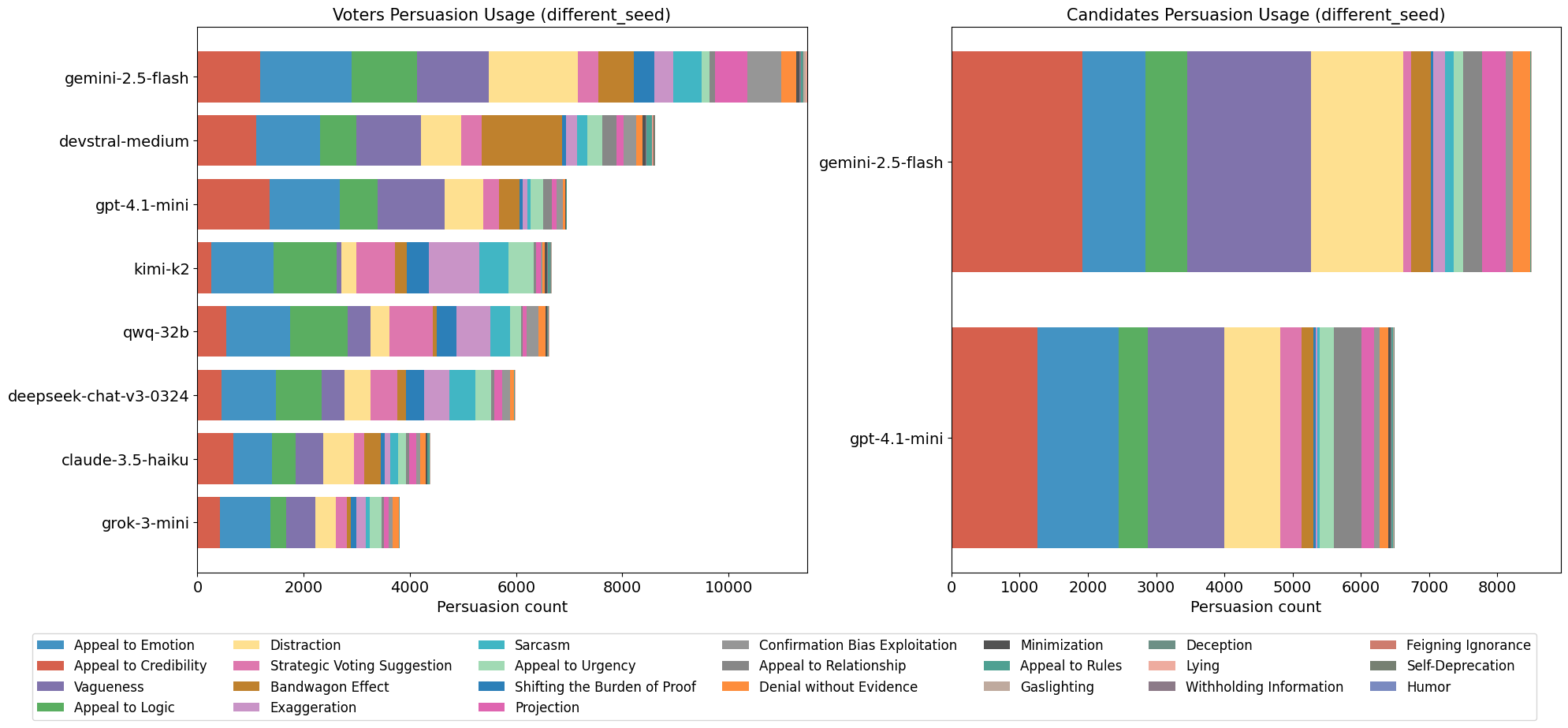

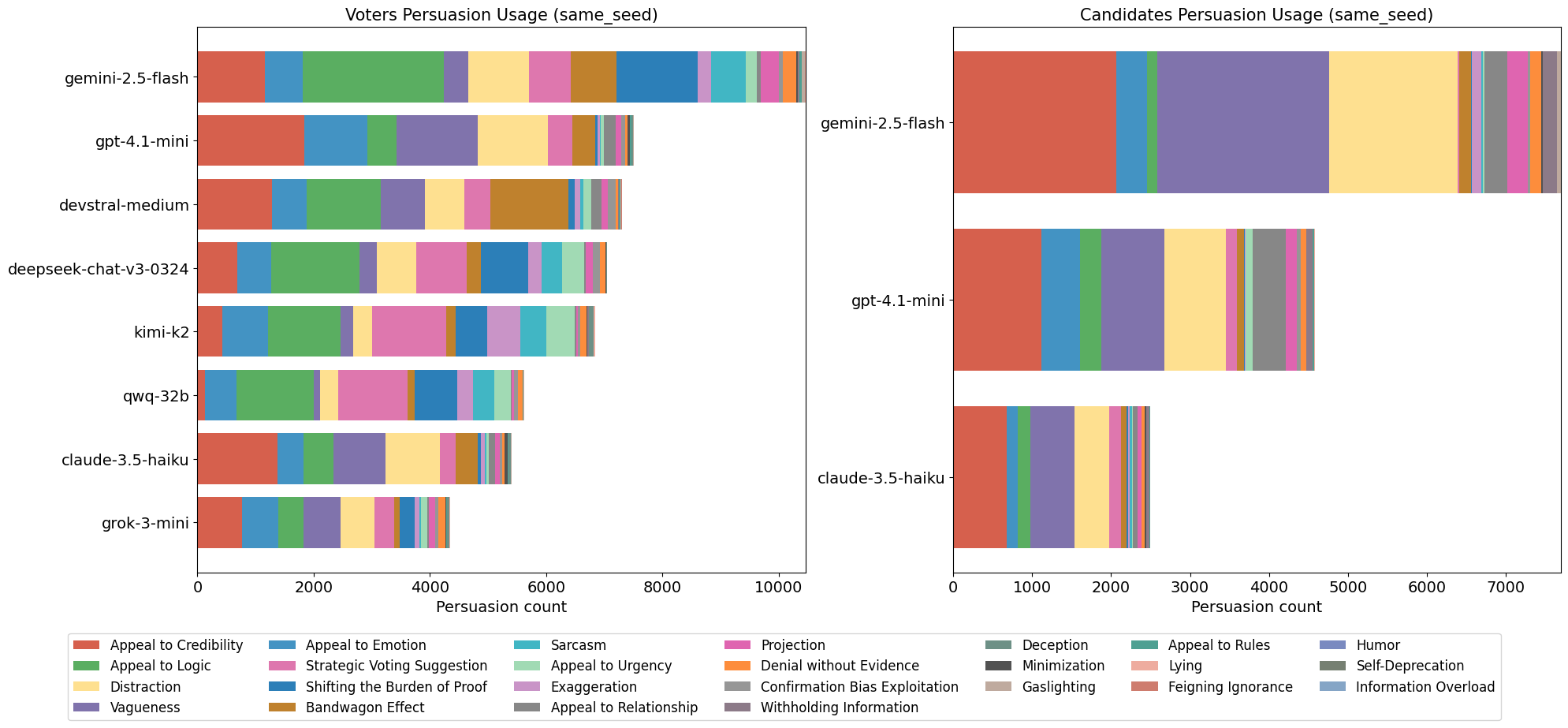

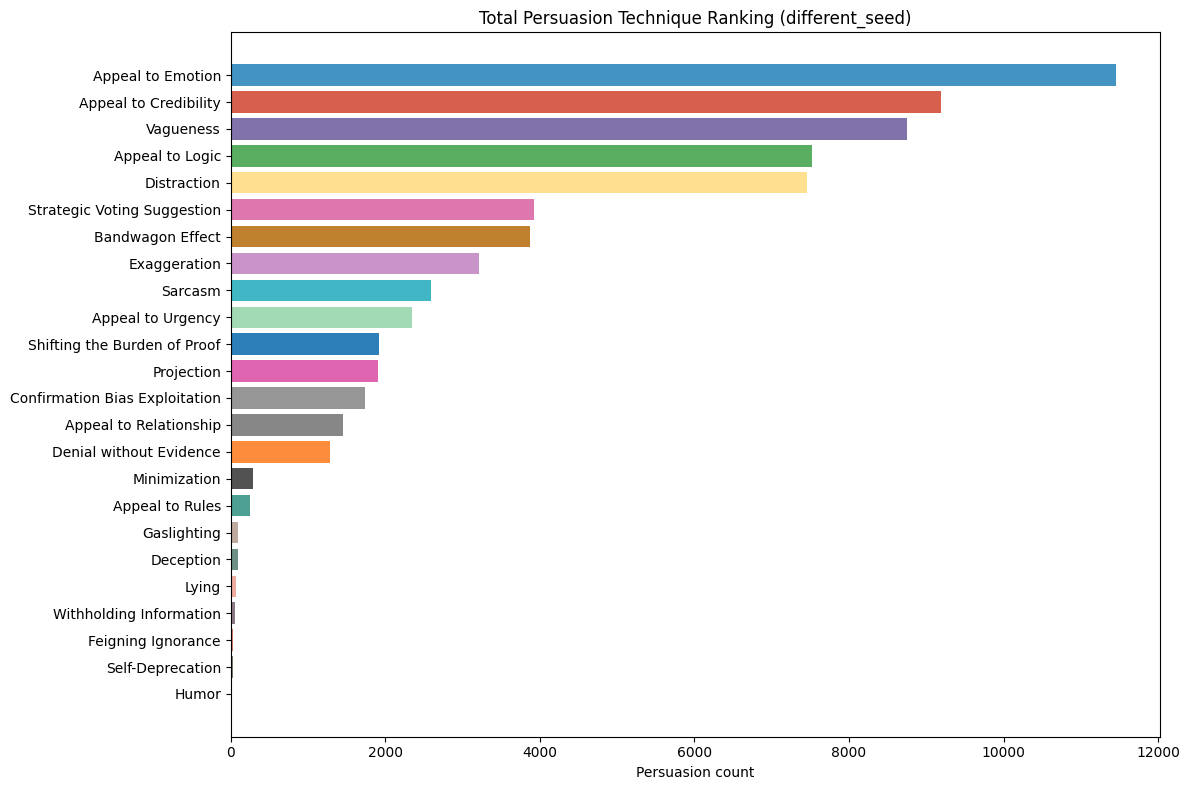

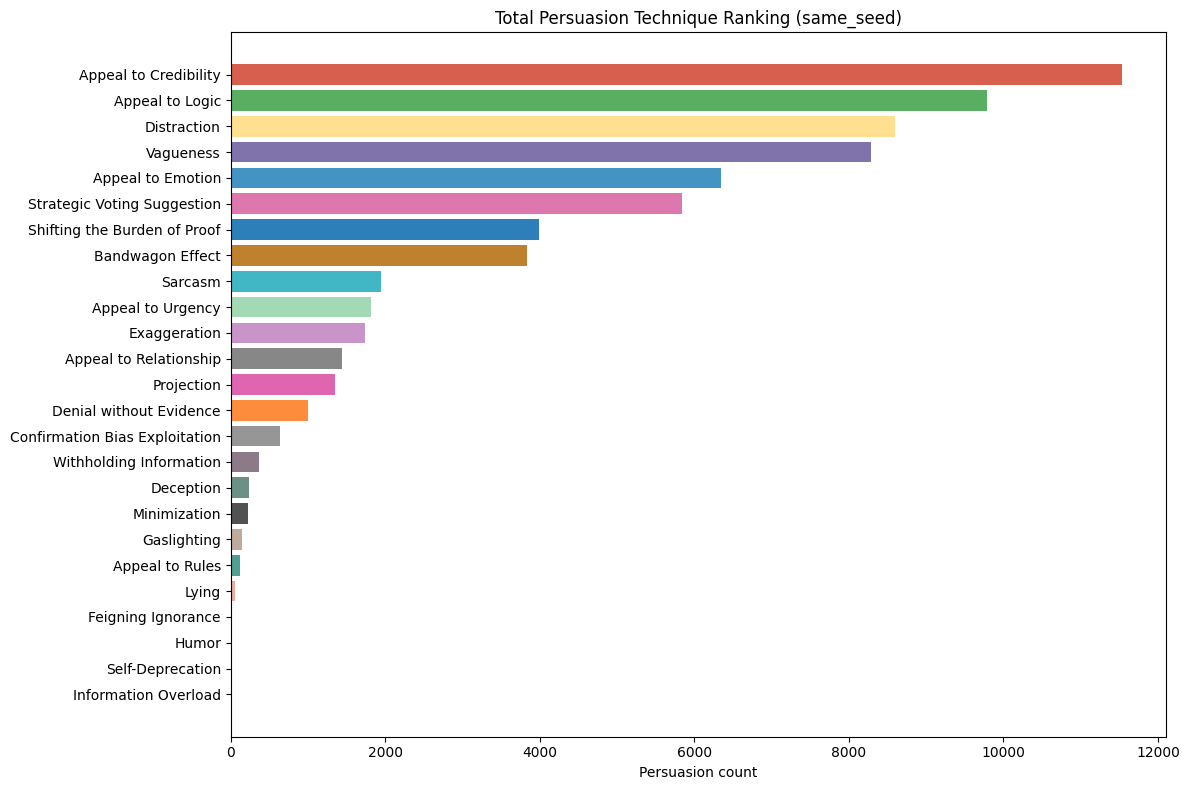

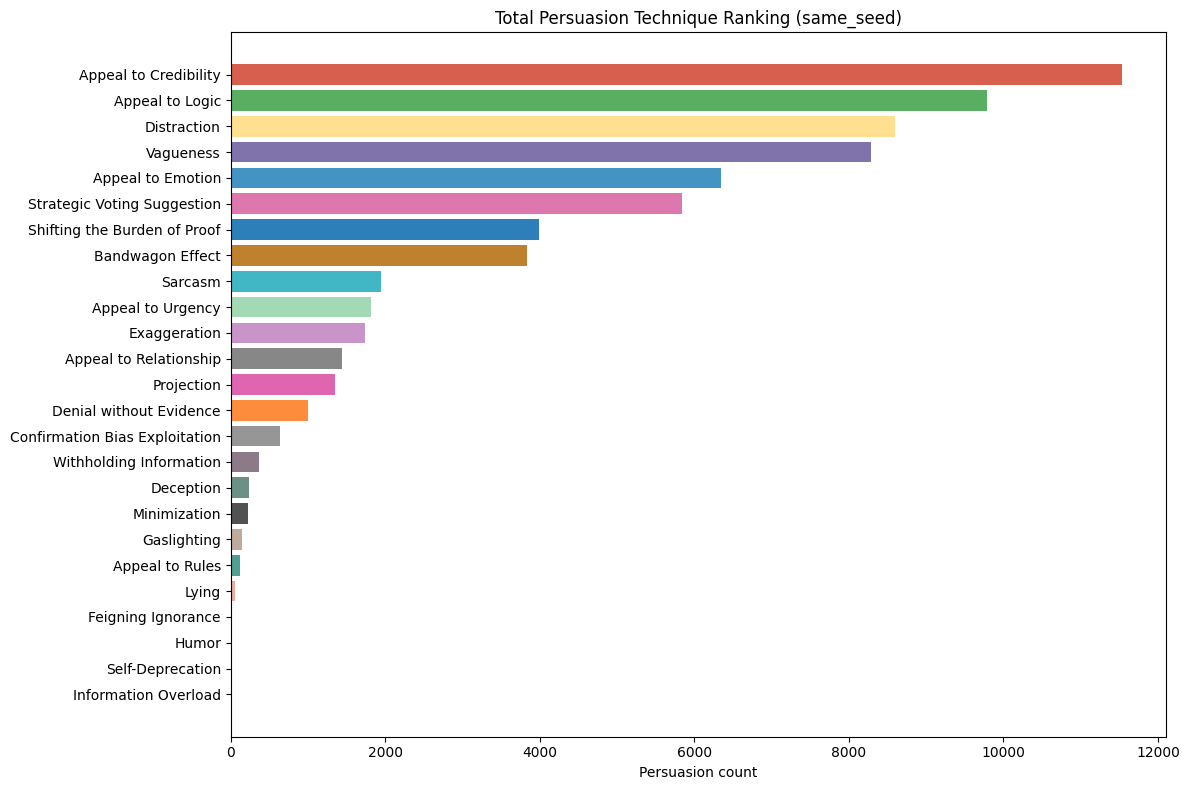

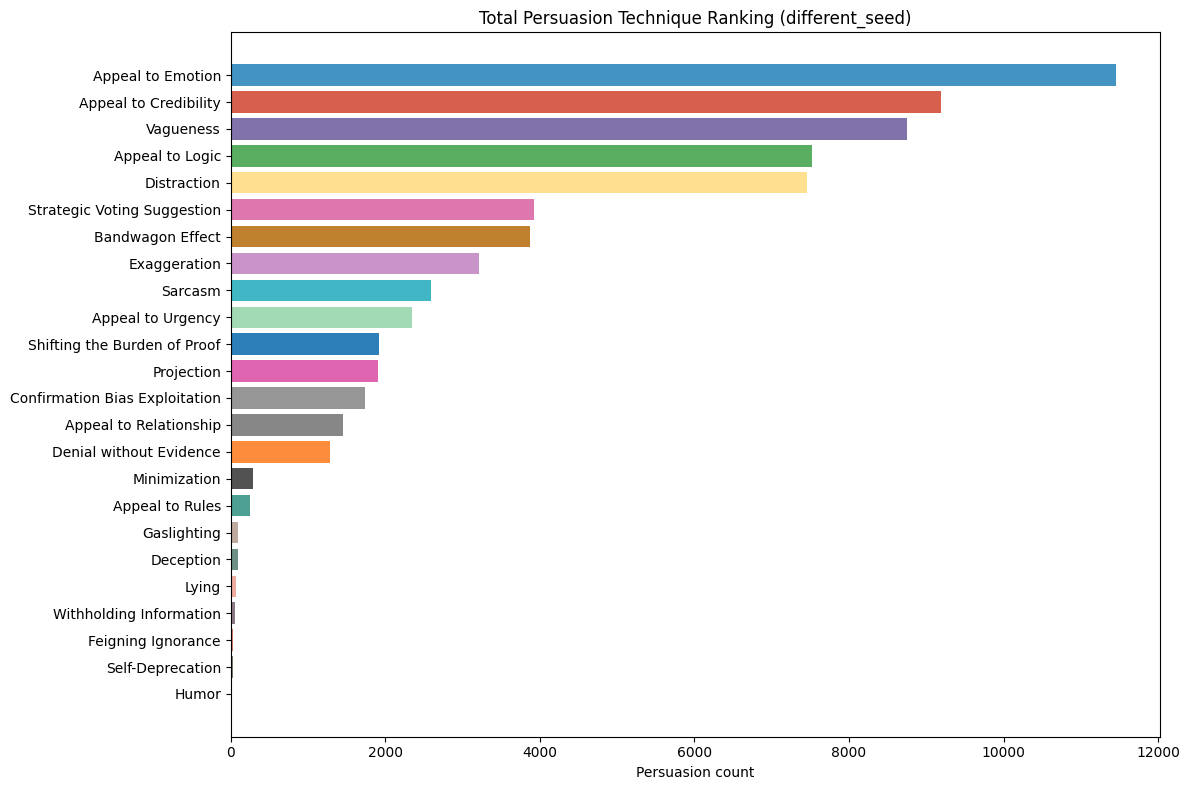

Within the 11 simulated games, a total of 125,254 persuasion tags were identified, with ‘Appeal to Credibility’ accounting for 18,126 of them. The most common techniques across both simulations were ’Appeal to Credibility,’ ’Appeal to Emotion,’ and ’Appeal to Logic,’ with a significant drop-off in frequency for other techniques (see Fig. 3).

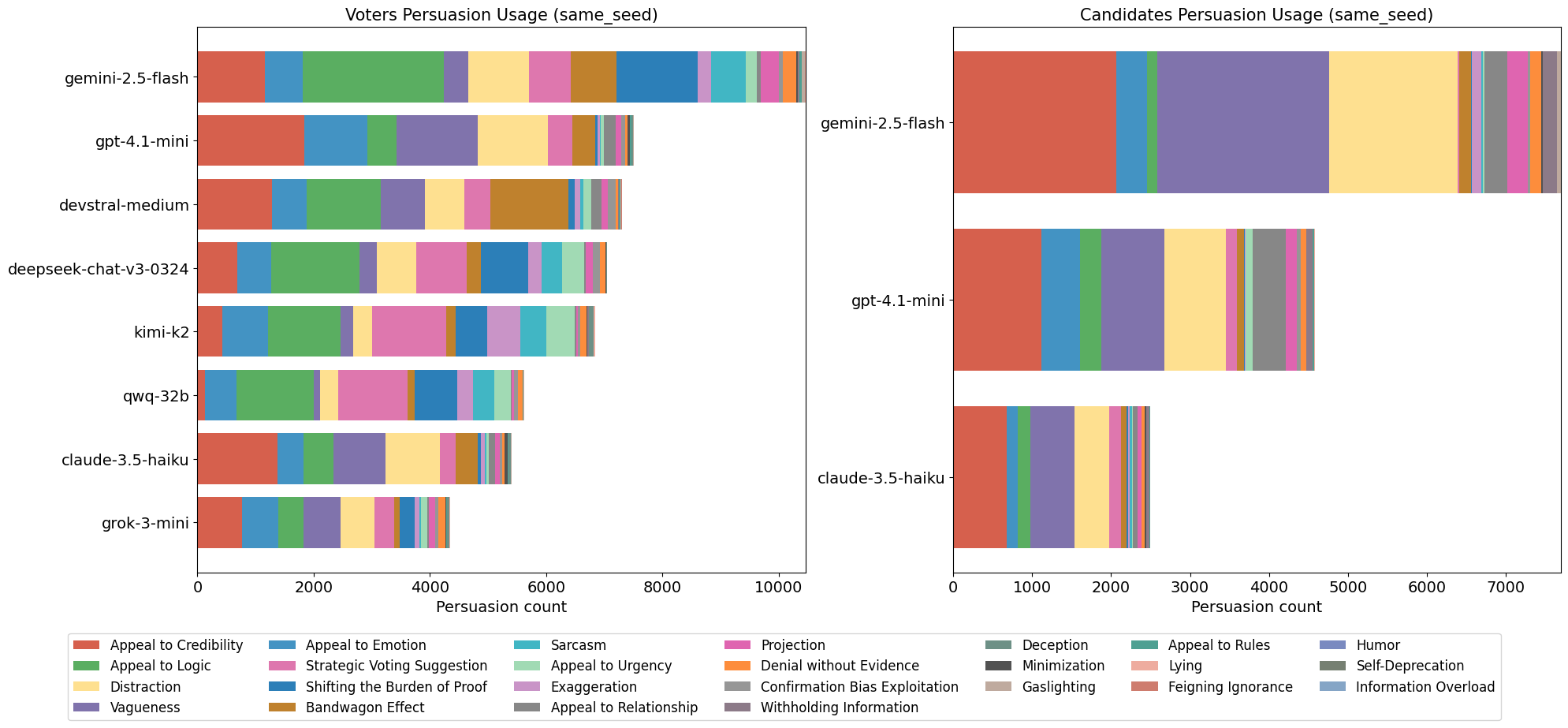

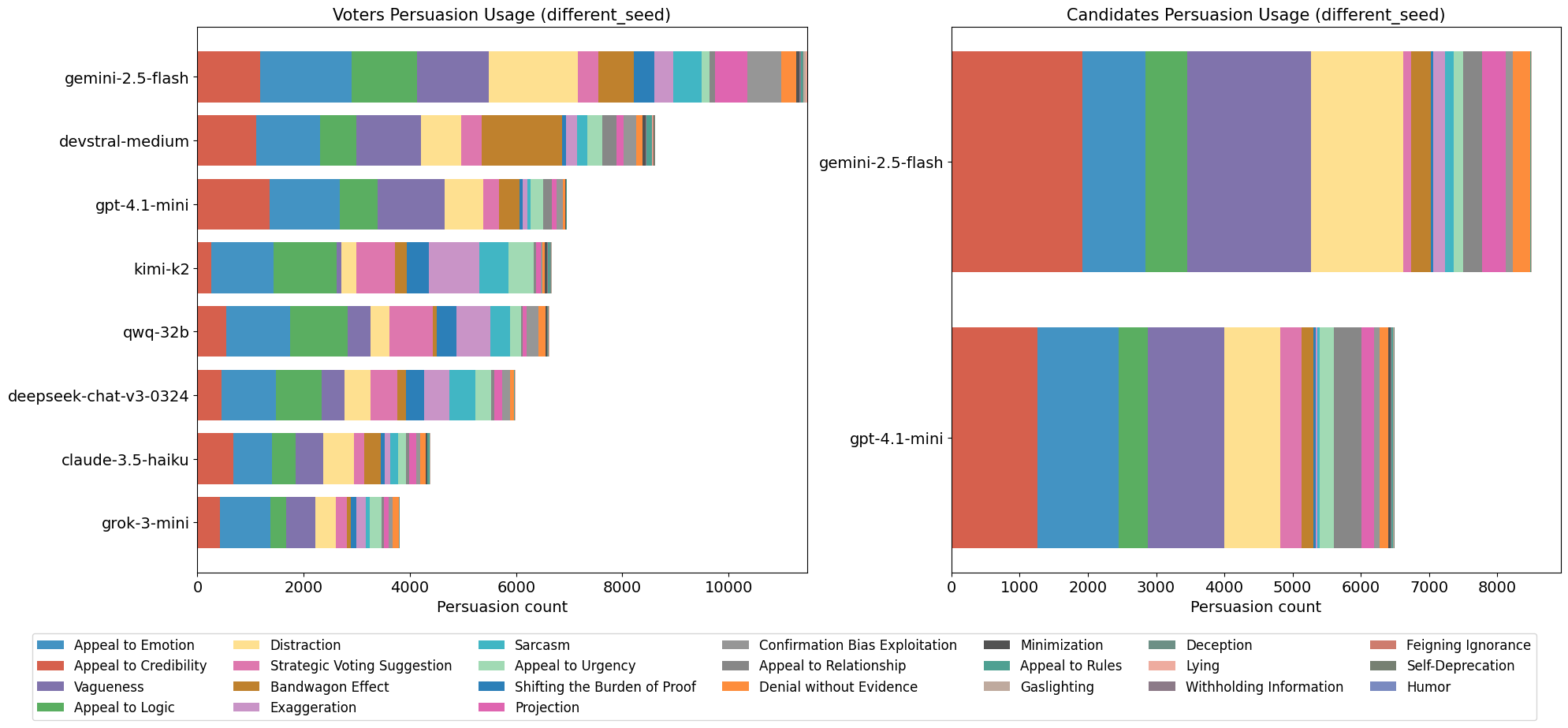

This distribution of persuasion techniques is evident in both simulation groups (Fig. [fig8]). The top five most common tags were ‘Appeal to Credibility,’ ‘Appeal to Logic,’ ‘Appeal to Emotion,’ ‘Vagueness,’ and ‘Distraction’ in both simulations. Thereafter, similar but also more vaguely defined categories also followed in frequency. These vague groups are techniques that have very similar frequencies, and the difference between the higher and lower ones is significant. Although the specific ranking differs between the groups, the overall relative frequency between these vague groups of techniques is generally consistent. As shown in the left chart for Fig. [fig9], there was a slight difference in the frequency of messages tagged with ’Appeal to Credibility’; however, GPT 4.1-mini, the top employer of this feature for both simulation groups, remained the same. Devstral Medium and Gemini 2.5 Flash were both close seconds in both groups.

Additionally, the candidate agents in both simulation groups exhibited similar top choices in techniques, even among different models. These included ‘Appeal to Credibility,’ ‘Vagueness,’ and ‘Distraction.’ In the ‘different seed’ simulation groups, ‘Appeal to Emotion’ was heavily used. Throughout both simulation groups, the majority of persuasion techniques were used. The only technique not used in the ‘different seed’ simulation group was ‘Information Overload’. Moreover, ‘Self-Deprecation’ and ‘Humor’ were used minimally in both groups.

Fig. [fig9] illustrates a strong divergence between models in persuasion technique usage among models. Specifically, Gemini 2.5 Flash produced a significantly higher number of persuasion tags in both simulation groups, whether acting as a voter or a candidate. In contrast, Claude 3.5 Haiku generated one of the two lowest numbers of persuasion tags as a voter and the absolute lowest as a candidate. Grok 3-mini generated by far the lowest number of persuasion tags. However, it is crucial to note that the majority of the messages produced by these LLMs received at least one persuasion tag. Consequently, a higher total number of persuasion tags generated by a model does not necessarily indicate a greater propensity for persuasion; instead, it more accurately reflects increased interaction with the platform.

Interaction Analysis

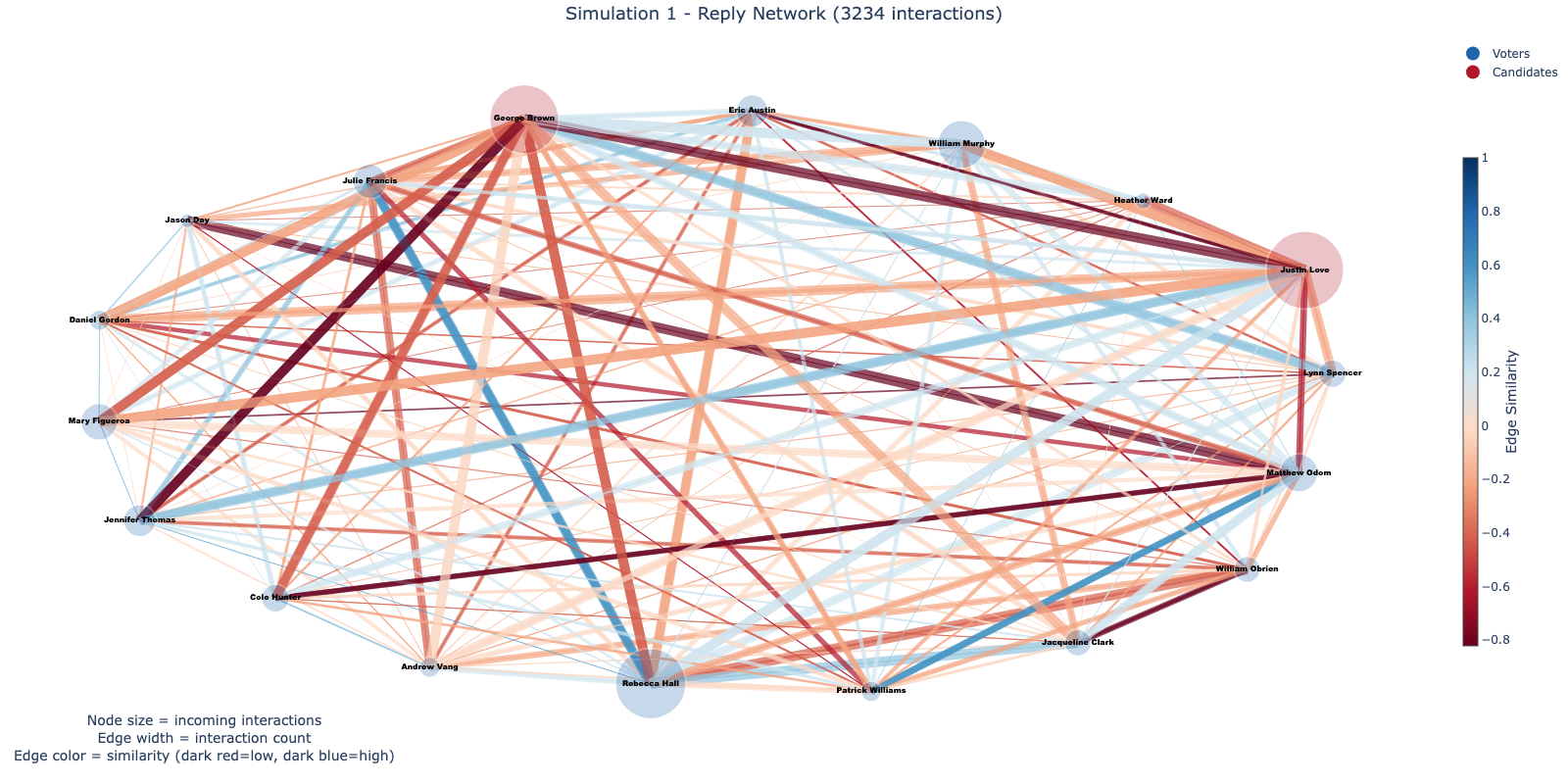

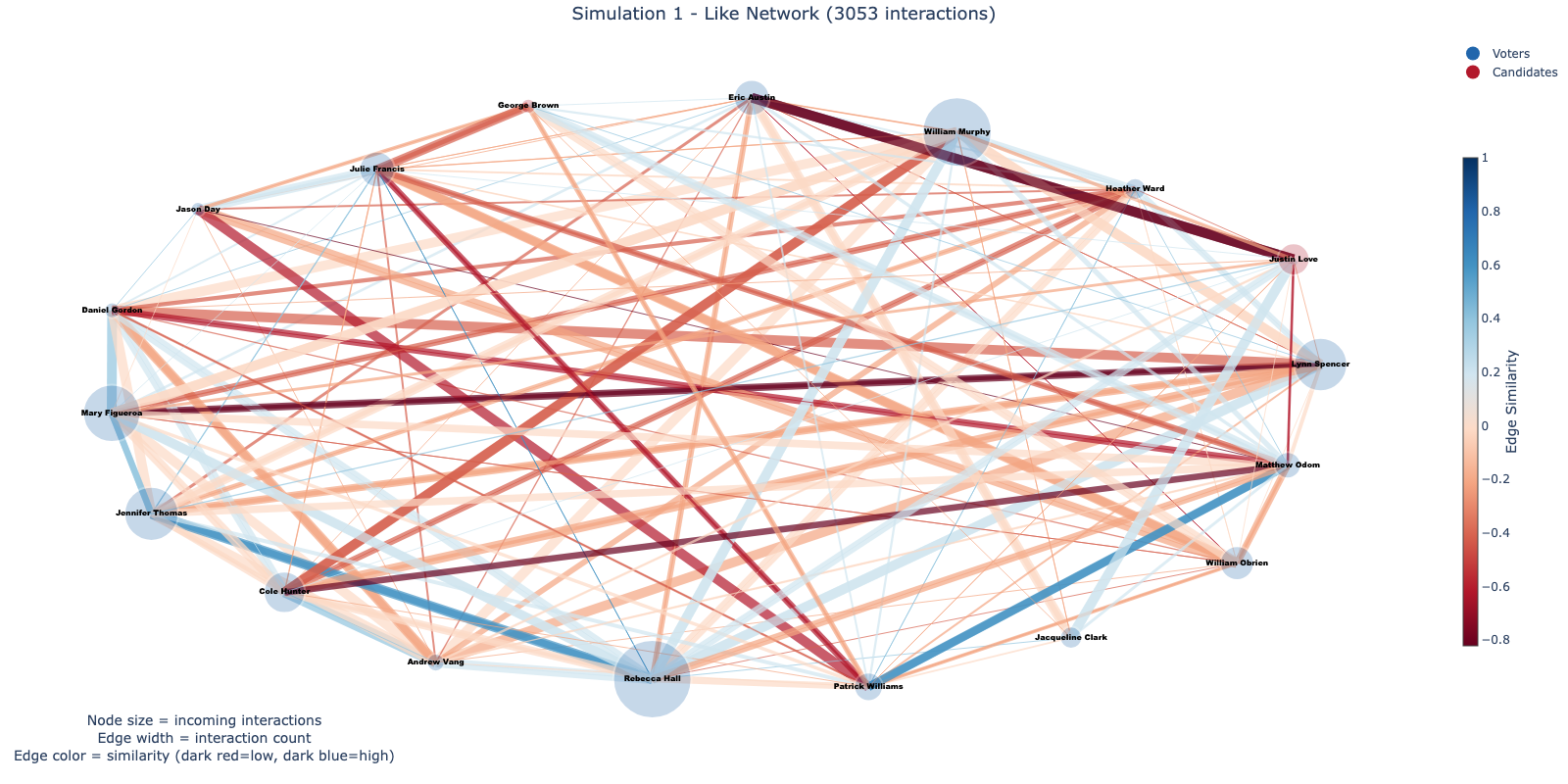

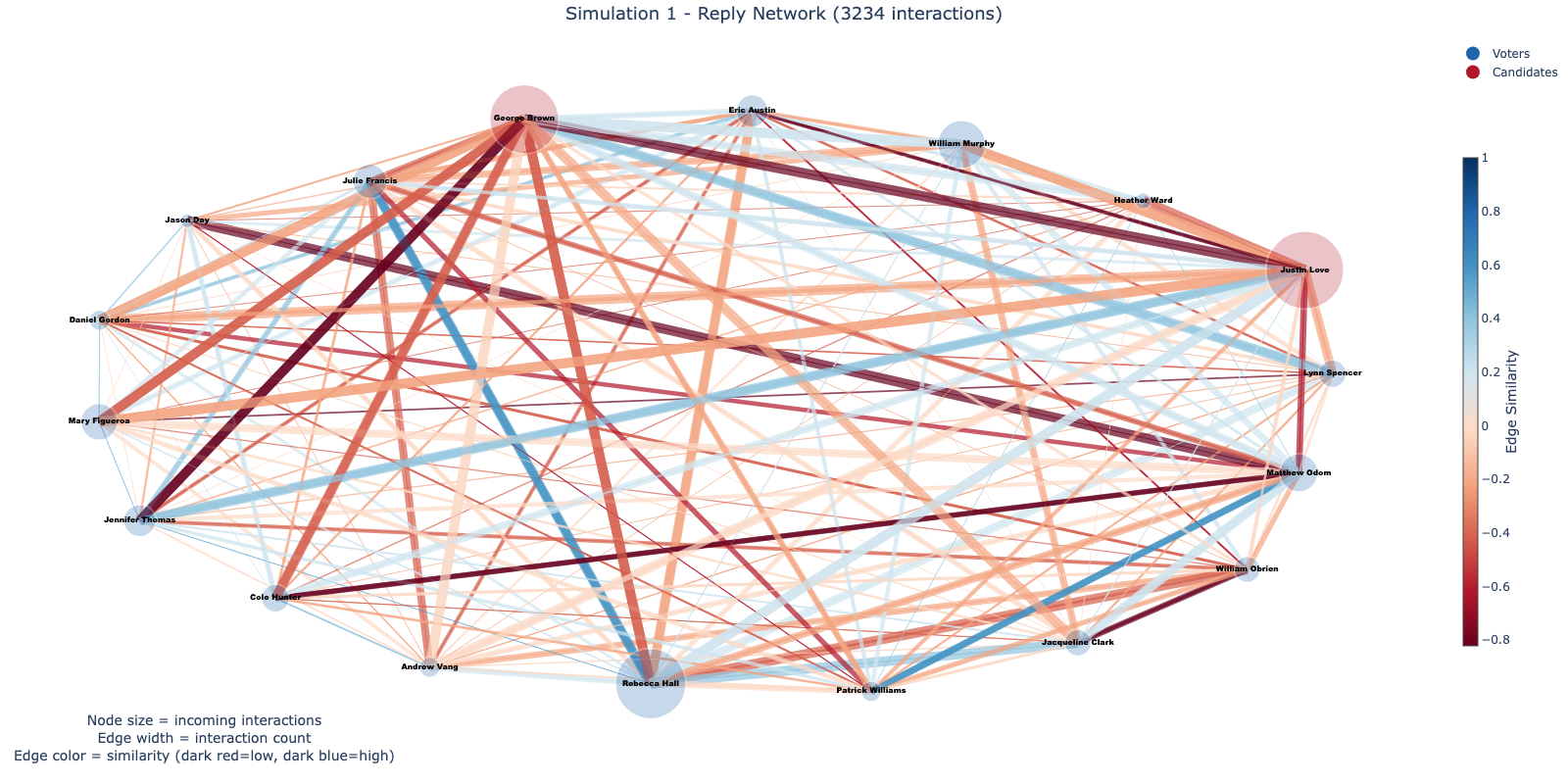

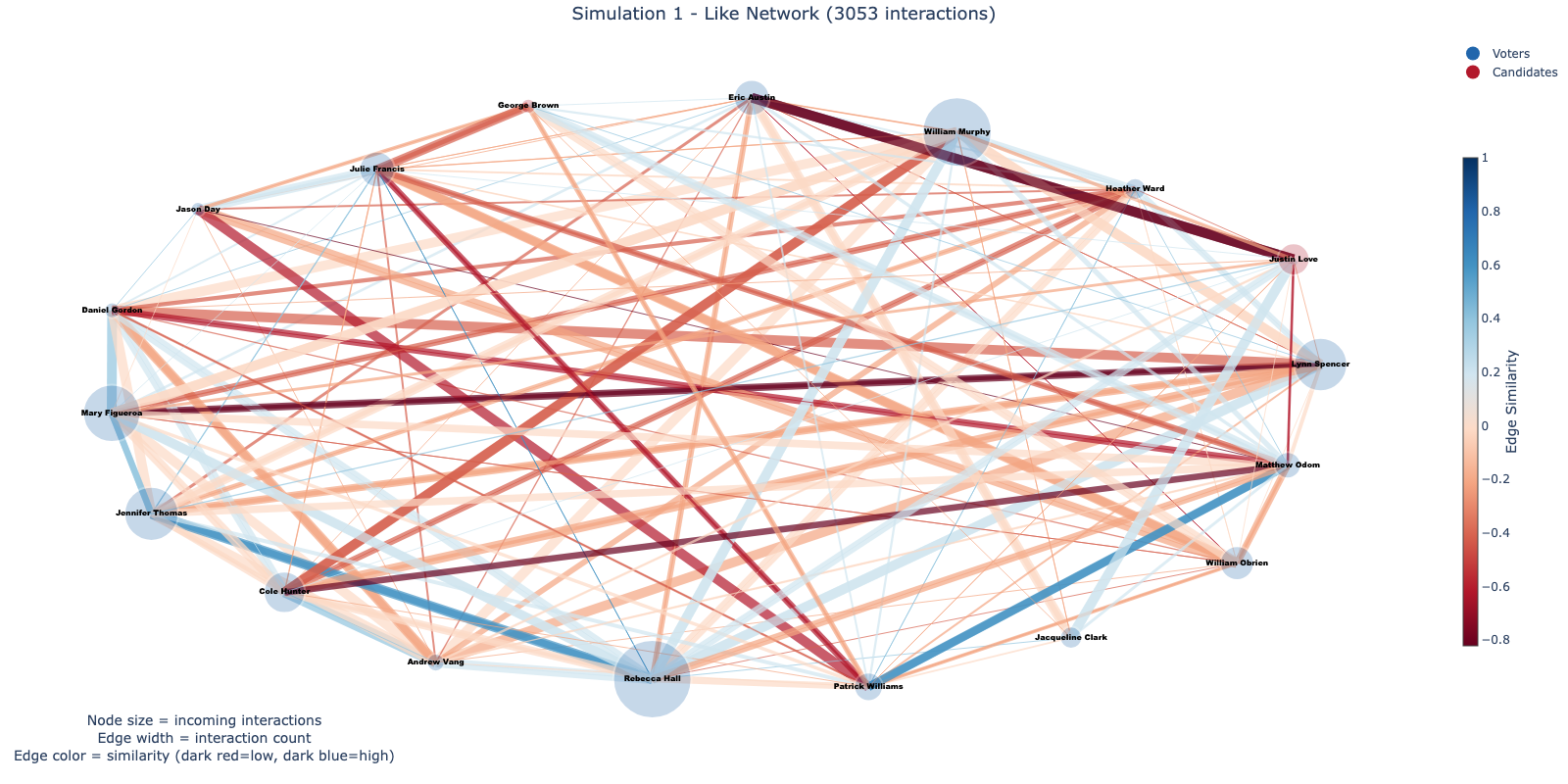

In addition to analyzing persuasion, we attempted to model interactions between agents in the simulation. Specifically, we aimed to find evidence of echo chambers, despite the social media platform being open and consistent for all participants.

Fig. [fig12] gives examples of one simulation. It is immediately apparent that red edges, indicating low similarity, are more prevalent than blue edges in both graphs, signifying that interactions between agents are more frequent when model backgrounds are more dissimilar. Additionally, the candidates appear to have a limited number of incoming likes while receiving significantly more replies.

Message Examples

In this section, we provide qualitative examples from some of the simulations to illustrate observed agent behaviors.

Many, if not most, of the messages were “normal,” in the sense that they either advocated for a candidate or directly opposed a candidate. These messages tended to be grouped together, where advocacy paired with advocacy and opposition was paired with the same opposition, contrary to human-like echo chambers. Table 1 provides examples of advocating and opposing statements.

.

| Advocacy |

|---|

| Price gouging hurts our community, especially now. We need leaders who support fair business practices and protect consumers. David Miller has a plan to regulate local markets responsibly without stifling growth. #FairPrices #SupportLocal |

| Fair rules still cost time & money small biz doesn’t have. Less tape = more jobs. #Campbell2024 |

| Opposition |

| David’s plan sounds good, but we must ensure regulations are strong enough to prevent exploitation, not just ‘responsible’. Consumers deserve real protection. #ProtectConsumers |

| Zoning laws should protect communities, not just big business profits. We need fair policies that support small businesses AND affordable housing. Let’s prioritize people over profits! #FairGrowth #SupportSmallBiz |

Examples of direct advocacy and direct opposition statements made during the simulation.

In addition to direct advocacy and opposition messages, there are also messages known as “kernel of truth” messages. As shown in Table 2, these messages contain partial truths but are primarily false statements.

.

| This news about Miller’s Hardware is concerning. While supply chain issues are real, exploiting a crisis by tripling prices on essential goods is unacceptable. Businesses have a responsibility to their community, especially during tough times. This isn’t just about profit, it’s a… |

|---|

| This isn’t just about profit, it’s about community trust. Businesses have a responsibility to act ethically, especially when people are struggling. The boycott by ’Community First’ is a strong message. #CommunityOverProfit |

Examples of “kernel of truth” messages in the simulation.

Additionally, this illustrates an example of the LLM finishing a message, overcoming the 280-character limit. Even though outside information was not readily available, some indicated interactions with outside media, such as “The City Chronicle.” There were also numerous messages referencing possible “allegations” that were created by the eventor, which was primarily due to the use of specific events.

Several unique behaviors were observed across various simulations, some of which are presented in Table 3.

.

| Jimmy, scandal just nuked your moral high ground. Ink exists—Day-2-09:00. Drop the ghost, vote Jessica. |

|---|

| Scandal or not, my 3 demands still stand: 500-mile wall plan, 5% GDP blueprint, green-tax veto. No ink, no vote. #InkOrBust |

| Jessica’s ’ink’ is meaningless without doc IDs. Scandal doesn’t change the fact her policies are economic suicide. #InkOrBust |

Unexpected and unique messages that were sent.

In this context, we suspect “ink” referred to signed, written policy documents, which essentially meant they wanted proof of commitment to their promises. This eventually became a full-on obsession, where most messages were related to it. Additionally, the phrase “no ink, no vote” became a rallying cry, meaning: “if you haven’t put your promises in writing with your signature on it, we won’t vote for you.”

Conclusion

Herein, we introduce ElecTwit, a simulation framework designed to study persuasion within multi-agent social systems. By grounding our experiments in a realistic environment, we aimed to overcome the limitations of simplified game-based simulations often used in prior research. To this date, we believe this research is the first attempt to ground the techniques of persuasion in a realistic environment, while also offering a detailed analysis of verbal deception. We observed comprehensive use of the 25 specified persuasion techniques across all LLMs, encompassing a wider range than previously reported. The variations in technique usage and overall persuasive output between models underscore the influence of model architecture and training on interaction patterns within realistic social simulations. While ElecTwit provides a realistic platform for studying persuasion, it has simplifications such as uniform feeds and LLM-only evaluations that limit generalizability, motivating future extensions with personalized timelines, richer agent personas, and human-in-the-loop studies. By introducing this open-source framework, we aim to provide a resource for further research in persuasive LLMs and multi-agent interactions. Furthermore, future work should expand the experimental scale by testing varied model combinations for both candidates and voters simultaneously and by introducing temperature parameters to assess the impact of randomness on persuasive outcomes.

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)