Clinical trial failure remains a central bottleneck in drug development, where minor protocol design flaws can irreversibly compromise outcomes despite promising therapeutics. Although cutting-edge AI methods achieve strong performance in predicting trial success, they are inherently reactive for merely diagnosing risk without offering actionable remedies once failure is anticipated. To fill this gap, this paper proposes ClinicalReTrial, a self-evolving AI agent framework that addresses this gap by casting clinical trial reasoning as an iterative protocol redesign problem. Our method integrates failure diagnosis, safety-aware modification, and candidate evaluation in a closed-loop, reward-driven optimization framework. Serving the outcome prediction model as a simulation environment, ClinicalReTrial enables low-cost evaluation of protocol modifications and provides dense reward signals for continuous self-improvement. To support efficient exploration, the framework maintains hierarchical memory that captures iterationlevel feedback within trials and distills transferable redesign patterns across trials. Empirically, ClinicalReTrial improves 83.3% of trial protocols with a mean success probability gain of 5.7%, and retrospective case studies demonstrate strong alignment between the discovered redesign strategies and real-world clinical trial modifications.

Clinical trials represent the most critical and expensive phase in drug discovery, with an estimated cost of $2.6 billion (DiMasi et al., 2016) per approved drug, and low success rates of approximately 10-20% (Yamaguchi et al., 2021). Serving as documented plan that specifies the study's objectives, clinical trial protocols involve complex, interdependent design choices (Getz and Campo, 2017), such as eligibility criteria, dosing strategies, and endpoint definitions, where small design flaws can propagate into irreversible failure. These challenges motivate the use of AI systems (Zhang et al., 2023) that can reason over high-dimensional trial designs, leverage historical evidence, and systematically assess failure risks at scale.

Recent advances in AI have enabled increasingly accurate prediction of clinical trial outcomes. For example, Lo et al. (2019) uses structured metadata to model success likelihood; Fu et al. (2022); Chen et al. (2024bChen et al. ( , 2025) ) integrate heterogeneous data sources using architectures including graph neural networks and hierarchical attention mechanisms to achieve strong predictive performance; Yue et al. (2024); Liu et al. (2025) incorporate Large Language Models (LLMs) and external knowledge bases to enhance reasoning and explainability in trial outcome prediction.

Despite their success, existing approaches are inherently reactive in nature: they operate on a fixed clinical trial protocol and produce a prediction or post-hoc explanation of trial success or failure. However, these methods do not address a more practically consequential problem: they are unable to respond to a determined trial failure due to the lack of actionable interventions. In real-world drug discovery, stakeholders require not only assessments of failure risk, but also actionable guidance on protocol redesign, including principled modifications or augmentations informed by the identified sources of risk.

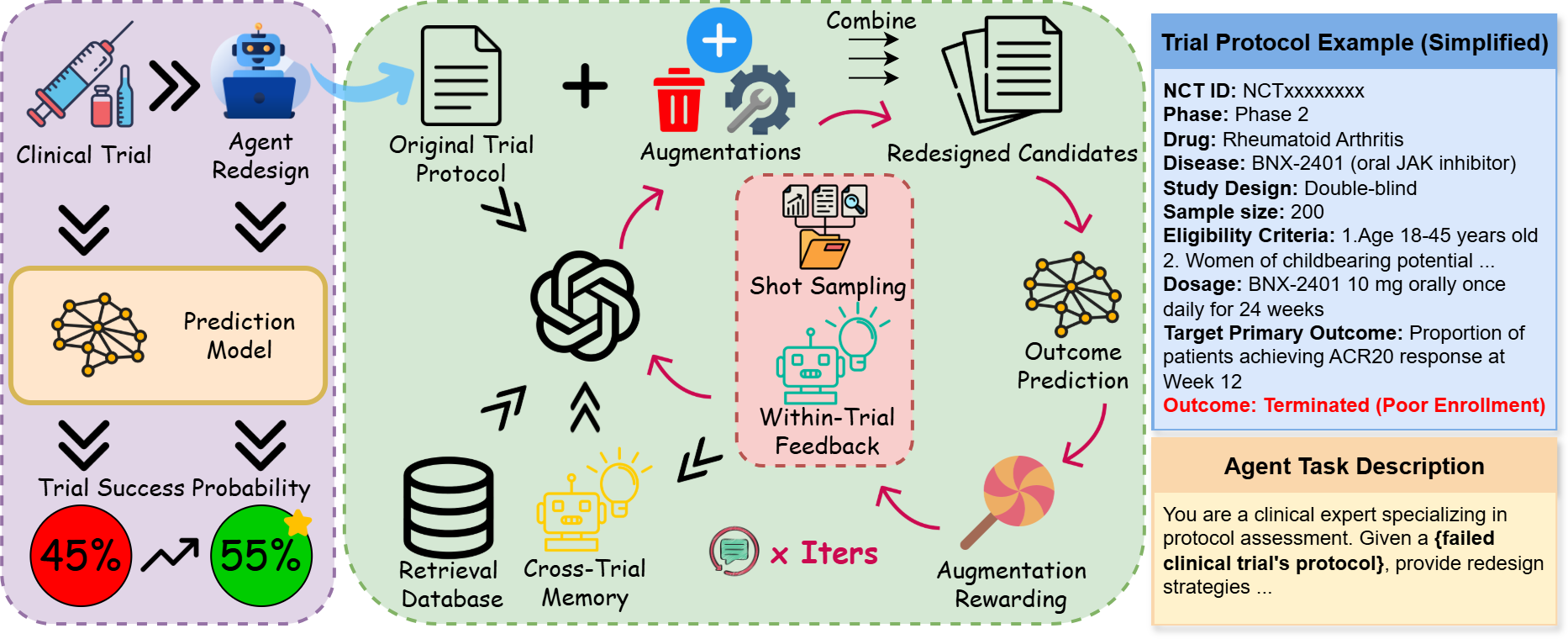

To bridge this gap, in this work, we propose ClinicalReTrial, a self-evolving AI agent framework that moves beyond static prediction toward actionable intervention via end-to-end trial protocol optimization, while continuously improves its redesign policies. The framework instantiates a coordinated multi-agent pipeline that performs failure diagnosis, protocol redesign, and candidate evaluation, with domain knowledge and safety awareness embedded at each decision stage. Beyond a single optimization run, we adopt the prediction model as a simulation environment to provide rewards for continuous self-improvement. Specifically, ClinicalReTrial maintains local memory to accumulate iteration-level feedback and rewardattributed modification outcomes for within-trial adaptation, while a global memory distills transferable redesign patterns across trials to enable warm start initialization and exploration calibration. Through this hierarchical learning structure and reward-driven closed-loop optimization, ClinicalReTrial systematically explores the protocol modification space and learns to identify highimpact interventions that improve clinical trial success probability.

Experimentally, our prediction model demonstrated the strongest performance (PR-AUC > 0.75), allowing it to serve as a reliable simulation environment for evaluation and agent optimization. In the trial redesign experiments, ClinicalReTrial successfully improve 89.3% of trial protocols with mean probability gain ∆p = 5.7%, achieved at negligible cost ($0.12/trial). We further conduct multiple real-world retrospective case studies. Impressively, the redesigns generated by ClinicalReTrial exhibit strong strategic alignment with independently derived real-world trial modifications, highlighting the potential of self-evolving AI agents to support principled, clinically grounded trial redesign. Main contributions are listed as follows: (1) (to the best of our knowledge) We are the first to formulate clinical trial optimization as an AI-solvable and in silico-verifiable problem. (2) We propose a multi-agent pipeline with domain knowledge that decomposes clinical trial protocol optimization into analysis, augmentation, and evaluation. (3) We develop a simulation-driven clinical trial optimization framework with hierarchical memory utilization for continuous self-improvement.

Early efforts employed classical machine learning (logistic regression (LR), random forests) on expertcurated features (Gayvert et al., 2016;Lo et al., 2019), establishing feasibility but lacking multimodal data integration. Deep learning approaches addressed this: Fu et al. (2022) proposed HINT, integrating drug molecules, ICD-10 codes, and eligibility criteria; Chen et al. (2024b) added uncertainty quantification; Wang et al. (2024) designed LLM-based patient-level digital twins; Chen et al. (2025) released a standardized TrialBench with multi-modal baselines. while maintaining competitive performance. Recent LLM approaches demonstrate medical reasoning (Singhal et al., 2023), enhanced via retrieval-augmented generation (Lewis et al., 2020) with databases like DrugBank (Wishart et al., 2018), Hetionet (Himmelstein et al., 2017), and domain-adapted encoders like BioBERT (Lee et al., 2020). Building on this, Yue et al. (2024) introduced ClinicalAgent, decomposing prediction into specialized sub-task agents with ReAct reasoning (Yao et al., 2023). Liu et al. (2025) proposed AutoCT for autonomous feature engineering via Monte Carlo Tree Search (Chi et al., 2024).

However, these methods function as discriminators mapping protocols to success probabilities without explaining why failures occur or how to modify protocols. First to formulate generative optimization, our multi-agent architecture leverages chain-of-thought (Wei et al., 2022), and least-tomost prompting (Zhou et al., 2023) for hierarchical problem decomposition.

Overview We propose ClinicalReTrial, a selfimproving multi-agent system that redesigns failed clinical trials through reward-driven iterative optimization. First, Section 3.1 formulates the clinical trial optimization problem. Then, Section 3.2 details the agent components, Section 3.3 presents the hierarchical learning mechanisms, and Section 3.4 describes the knowledge retrieval system. For ease of exposition, Figure 1 illustrates the whole process and Algorithm 1 formalizes the iterative optimization procedure.

Let T 0 = {e 1 , e 2 , . . . , e K } denote a clinical trial protocol decomposed into K modifiable elements (e.g., eligibility criteria, dosage regimens, endpoint definitions), where a prediction model f θ : T → [0, 1] assigns success probability p 0 = f θ (T 0 ). Each element e i admits a set of augmentations A i = {a i1 , a i2 , . . . , a im i } representing clinically valid modifications, constructing candidate protocols T ′ = T 0 ⊕ S by recombining augmented elements with the original protocol. Given the exploration set of redesigned protocol candidates T = {T ′ 1 , T ′ 2 , . . . , T ′ N } evaluated through the model to obtain predicted probabilities, each p ′ j = f θ (T ′ j ), the optimization objective seeks for maximizing

if r max > r best then r best ← r max , T * ← arg max T ′ ∈explored r(T ′ )

7:

Nmax ); 10: return T * , r best success probability (p * ), with overall improvement measured by ∆p = p * -p 0 where p * = f θ (T * ).

The Analysis Agent identifies modification targets within failed trial protocols. Given a failed protocol and prior failure modes: {POOR ENROLLMENT, SAFETY/ADVERSE EFFECT, DRUG LACK OF EF-FICACY}. the agent produces a prioritized set of modification, targeting the protocol feature under consideration. Then specifies the action strategy, {DELETE, MODIFY, ADD} with confidence score.

Protocol Taxonomy. Protocol features are classified by catagories: eligibility criteria into participation barriers, safety exclusions, selection criteria, and enrichment criteria; dosage/outcomes by safety risk, failure contribution, and modification efficacy. This taxonomy guides action selection given the observed failure reason and according analysis.

Action Determination. The agent extracts failure signatures via action category alignment and confidence scoring, pre-calibrated using historical modification success patterns. At iteration t = 1, the agent receives warm start guidance from crosstrial memory ( §3.3.3); from t ≥ 2, it incorporates performance patterns from prior iterations ( §3.3.2). These insights yield prioritized modification targets balancing domain knowledge with empirical feedback, which guide the Augmentation Agent ( §3.2.2) to generate concrete modifications.

The Augmentation Agent translates diagnostic insights from the Analysis Agent into diverse de-sign refinements that address identified weaknesses while preserving clinical validity.

Action-specific Variant Generation. The agent employs action-specific logic: DELETE critical failure factors while preserving safety; MODIFY adjusts thresholds or operationalizes vague terms; ADD introduces biomarker enrichment or contraindication criteria. Multiple variants per target enable exploration, with candidates proceeding to validation ( §3.2.3).

To make sure ClinicalReTrialAgent’s proposed augmentations satisfy clinical safety standards, the system employs LLM-as-a-Judge (Zheng et al., 2023) through hierarchical validation stages.

Autonomous Safety Validation. The agent checks and prunes unsafe modifications (dosage changes, population shifts, contraindications) and autonomously retrieves evidence from DrugBank, Disease Database, and PubMed ( §3.4) when parametric knowledge is insufficient. Validated candidates that passed all stages of progressive filtering proceed to the Exploration Orchestrator ( §3.2.4) for simulation-based evaluation and reward assignment.

The Exploration Orchestrator combines validated augmentations with the original trial protocol into complete redesigned trial candidates, each evaluated through simulation based assessment with outcome probability assigned that guides augmentation rewards and hierarchical learning ( §3.3).

Our framework enables progressive improvement through hierarchical knowledge consolidation operating at two temporal scales: within-trial learning accumulates local memory M local t across iterations for trial-specific refinement, while cross-trial learning maintains global memory M global to transfer successful patterns across the trial corpus.

To identify which individual modifications drive improvement, we decompose protocol-level outcome probabilities into augmentation-level rewards. The Exploration Orchestrator first evaluates combined trial variants via prediction, then attributes credit to individual modifications. For each augmentation m, we compute its marginal contribution across the explored combinatorial space:

The complete reward distribution R t = {(m i , r(m i ), v i )} encompasses all augmentations with their rewards and validation status, enabling performance-stratified knowledge extraction from both successful modifications and contraindicated patterns.

Knowledge distillation operates on the complete reward distribution R t , serving as short-term memory. Strategic-level knowledge K s t guides which modification categories merit prioritization. Tactical modification examples K t t are used to calibrate how modifications should be formulated.

Agent Integration. The Analysis Agent partitions aspects into three coverage sets: previously failed modifications (zero confidence), previously successful modifications (diversification penalty to avoid over-exploitation), and unexplored modifications (exploration bonus). Confidence scores combine coverage-based adjustments with actiontype success rates from historical trials. The Augmentation Agent samples performance-stratified exemplars for few-shot prompting, while the Exploration Agent maintains a redesign pool of topquartile modifications (r > 0, 75th percentile) for combinatorial search reuse.

Global memory M global maintains generalizable patterns through two representations: Qualitative strategic guidance (aspect-level recommendations extracted via LLM synthesis from high performing redesign patterns) provides warm start initialization for the Analysis Agent at iteration t = 1, where iteration feedback is absence; Quantitative statistical signatures (mean reward, variance, modification success rate) enable the Augmentation Agent to continuously calibrate exploration intensity, scaling generation count inversely with historical success rates and proportionally to pattern variance. After each trial converges, patterns distilled from the final iteration, enabling systematic knowledge transfer where each trial benefits from and contributes to the evolving global memory.

The multi-agent system augments embedded parametric knowledge with targeted retrieval from curated biomedical databases: DrugBank (Wishart et al., 2018) with pharmacological profiles including toxicity, metabolism, contraindications; Disease Database (Chen et al., 2024a) that contains diagnostic criteria, symptomatology, risk factors; and PubMed Abstract spanning 1975-2025. Retrieval employs dense embeddings (BioBERT (Lee et al., 2020) for drugs/diseases, PubMedBERT (Gu et al., 2021) for literature) with FAISS indexing.

Retrieved results undergo LLM-driven validation, filtering tangential content, while enforcing strict temporal constraints that limit PubMed queries to prevent outcome leakage.

We evaluate ClinicalReTrial across two dimensions: (1) simulation environment performance, validating that GBDT-based outcome predictors achieve sufficient accuracy to serve as reliable feedback oracles, and (2) ClinicalReTrialAgent optimization quality, demonstrating that our multiagent system successfully redesigns failed trials through iterative learning.

Our system is built on GPT-4o-mini and evaluated on failed clinical trials from the TrialBench dataset (Chen et al., 2025). Using 20769 annotated Phase I-IV trials, we encode multi-modal features into 6,173-dimensional embeddings (details in Appendix A.1.2) and train LightGBM (Ke et al., 2017) classifiers to predict trial outcome ŷ ∈ [0, 1]. We follow TrialBench’s train-test split, further splitting the training set 8:2 for training-validation. Due to computational constraints, we evaluate the agent on a stratified sample of 60 failed trials from the test set (20 enrollment, 20 safety, 20 efficacy failures) representing diverse trial phases (Data detail in Appendix A.1.1). The agent operates with a 5-iteration budget. We employ an adaptive exploration strategy: when the estimated factorial space < 1, 000 combinations, we perform exhaustive exploration to find the optimal solution; otherwise use beam search with width k = 8. We measure effectiveness through predicted probability improvement, threshold achievement rate, and convergence efficiency.

Our Simulation Environment’s model (GBDT) is compared against Baseline approaches (Trial-Bench (Chen et al., 2025) and HINT (Fu et al., 2022), prior SOTA systems operating on original TrialBench features), and Logistic Regression also trained on the same encodes (Appendix A.1.2).

Failure-specific Prediction. Implemented in ClinicalReTrialAgent, the simulation environment must correctly predict specific failure outcomes (enrollment, safety, efficacy). We train three independent binary GBDT classifiers on our encoded features, each targeting one failure detection task against success. Table 1, 2 and 3 report comprehensive metrics across our models and baseline approaches re-trained for the binary task: Poor Enrollment, Safety/Adverse Effect and Lack of Efficacy prediction. Our model achieves PR-AUC > 0.75 across all failure modes, meeting the threshold for reliable discriminative feedback. All models achieve Failure Detection Rates of 70-74% at task-specific thresholds (p ≥ 0.6 for enrollment, p ≥ 0.9 for safety, p ≥ 0.85 for efficacy). This ensure that predicted probability shifts ∆p > 0.03 reliably indicate improved trial designs (Appendix A.1.1).

TrialBench Benchmark. We further validate the same model architecture against existing benchmarks on the TrialBench 4-class classification task (predicting Success, Enrollment Failure, Safety Failure, or Efficacy Failure). Table 4 shows the Simulation Environment’s base model in our sim- ulation environment performed best over all baselines, with higher ROC-AUC of 0.06 to 0.19.

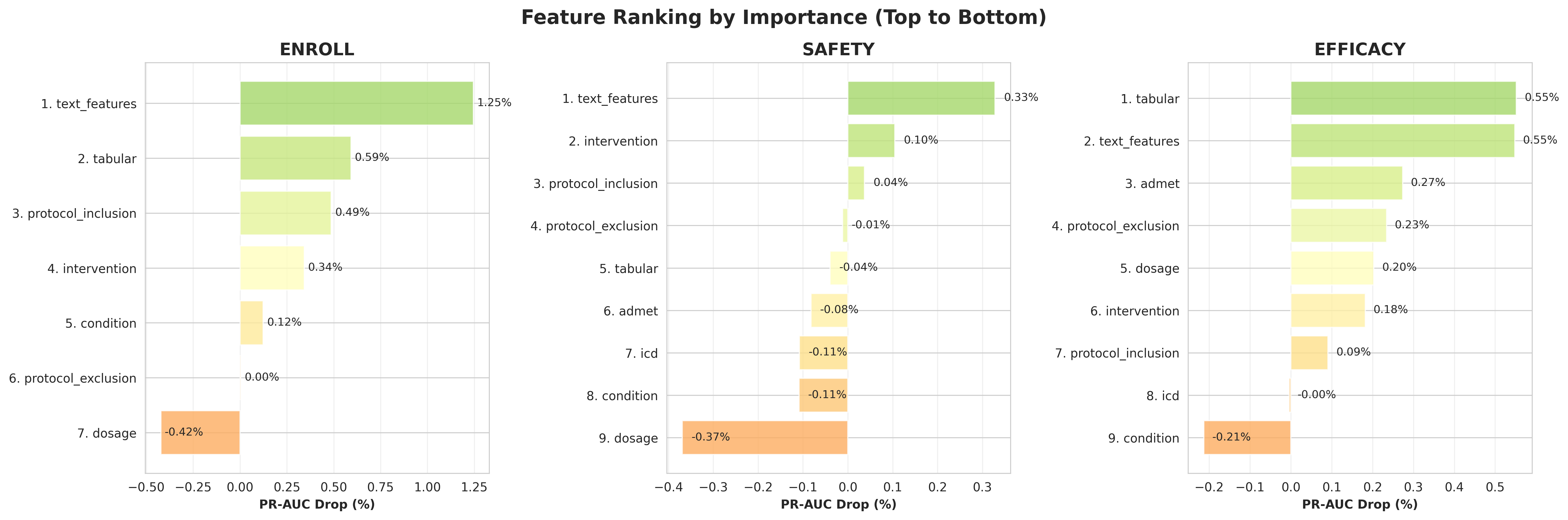

Feature Importance Analysis. We studied feature importance analysis with SHAP (Lundberg and Lee, 2017). Consistent with our hypothesis, sentence-level eligibility, Drug-disease interaction features and endpoint alignment features are most important for outcomes prediction (Appendix A.1.3).

Having confirmed the simulation environment’s reliability, we evaluate ClinicalReTrialAgent’s ability to redesign failed clinical trials.

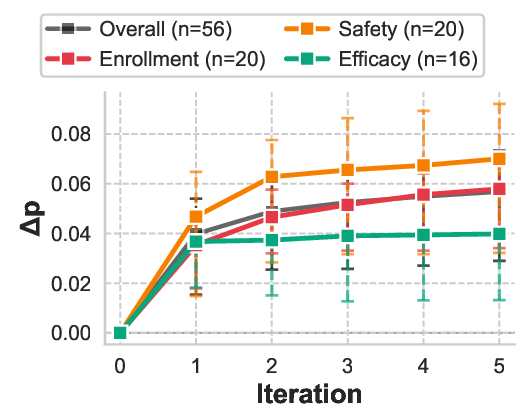

Table 5 reports comprehensive convergence statistics across all trials. The Agent had 83.3% of protocol designs improved (50/60 successfully processed trials showed positive ∆p), with 4 trials (6.7%) encountering agent failures where the system identified zero opportunities of potential redesign, occurring in the efficacy failure mode. The system demonstrated efficient convergence patterns, with 15% (9/60) of trials exhibiting natural termination before iteration 5 due to exhausted modification space. Most trials used all 5 iterations, suggesting adaptive stopping could improve efficiency. Performance heterogeneity across failure modes reflects the differential amenability of clinical trial design elements to protocol-level intervention. Safety failures exhibit the largest improvements (mean ∆p = +0.070, IQR [+0.032, +0.092]), as adverse events often stem from identifiable contraindication patterns that can be systematically addressed through eligibility refinement and dosage adjustment. Enrollment failures show substantial gains (mean ∆p = +0.058), consistent with the observation that recruitment barriers frequently arise from overly restrictive or poorly specified inclusion criteria rather than fundamental feasibility constraints. Efficacy failures demonstrate the smallest yet statistically meaningful improvements (mean ∆p = +0.040), as therapeutic effectiveness depends heavily on drug-disease compatibility, where sometimes protocol modifications alone cannot fix the essential drug failure. As shown in Figure 2, the learning trajectory reveals major initial gains followed by decreasing returns. This pattern validates the knowledge distillation mechanism: high-quality modifications are identified early through rapid retrieval augmented analysis, while later iterations exploit narrower optimization opportunities by refining secondary parameters or addressing edge case contraindications.

The system demonstrates practical feasibility with a mean cost of $0.12/trial across 56 trials-0.0000026% of typical $2.6B drug development costs (Lo et al., 2019). Table 7 shows consistent cost-effectiveness across failure modes (Cost/∆p: 3.0-4.8). Linear scaling enables industrial deployment: 1,000 trials cost $122, establishing ClinicalReTrialas practical for systematic optimization at scale.

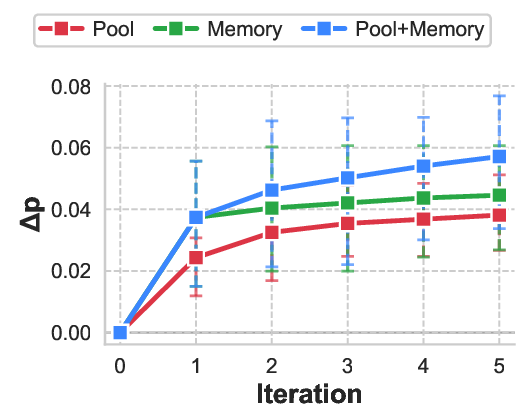

To validate architectural components, we conducted paired ablation across 10 enrollment failure trials, systematically removing: (1) memoryguided iterative learning and (2) redesign pool optimization. Each trial was evaluated under all three conditions with identical initialization, enabling within-subjects comparison.

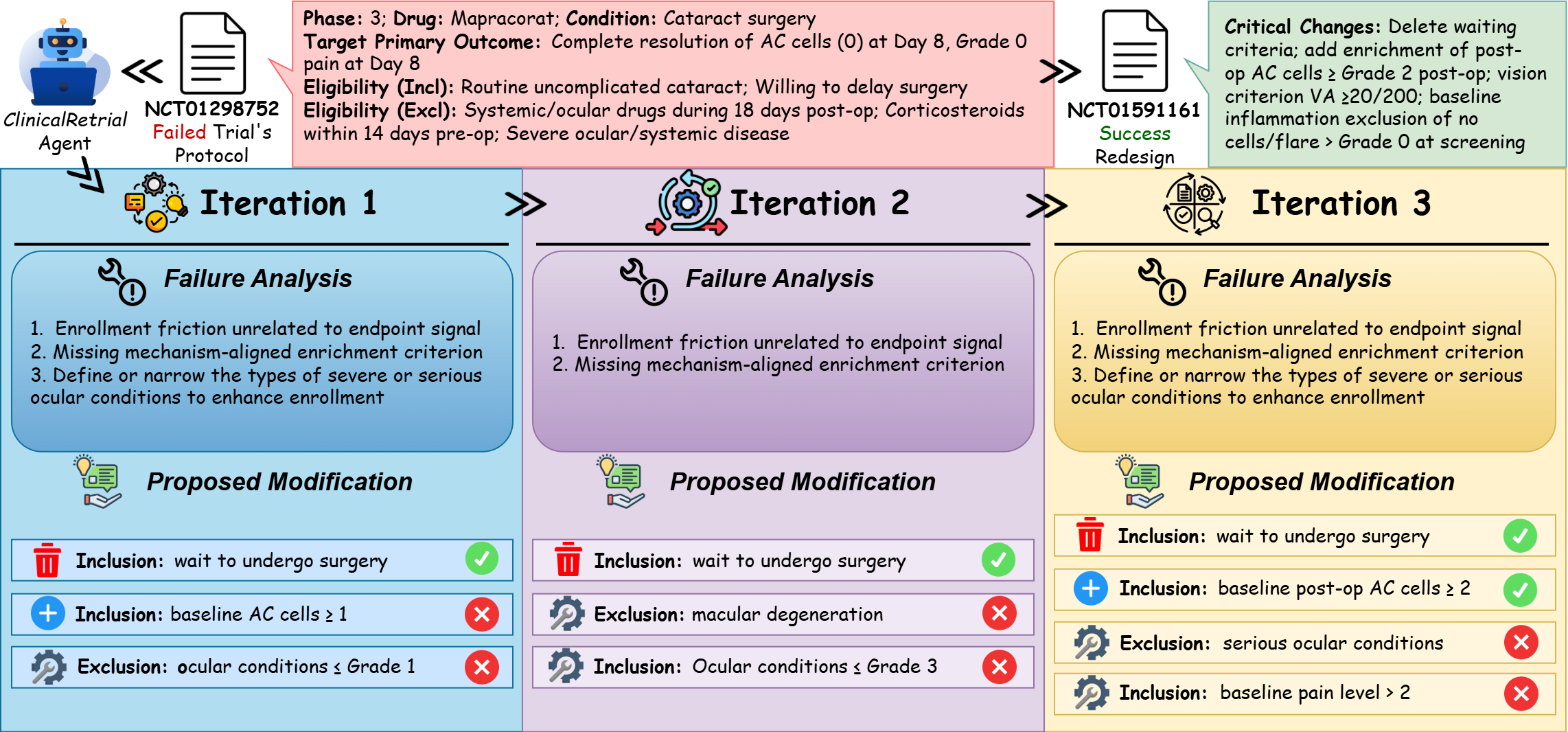

Both components contribute significantly and independently (Figure 3, Table 8). Memory removal degraded performance at iteration 1 (∆p = +0.0131, p = 0.042) and iteration 5 (∆p = +0.0190), demonstrating immediate warm start benefits that strengthen over iterations. Removing the redesign pool yielded comparable degradation (∆p = +0.0126). These findings validate our design: memory enables the agent to manage intelligent exploration, while the redesign pool enables exploitation by reusing successful modifications. Here we present a poor enrollment redesign case (safety and efficacy cases in Appendix A.5): NCT01298752, a Phase 3 trial of Mapracorat (antiinflammatory ophthalmic suspension) for postcataract surgery inflammation that failed due to slow enrollment. Sponsored by Bausch & Lomb, the trial was subsequently redesigned and successfully executed as NCT01591161. Figure 4 illustrates ClinicalReTrial’s iterative refinement process across three optimization cycles. The Enrollment barrier (cataract surgery waiting requirement) is efficiently identified with positive reward provided by simulation environment. The agent also progressively explores the modification space: baseline AC cell requirements is successfully added as an enrichment criterion; while agent also explores the safety enhancement, but end up failing to align with real-world redesign.

In this work, we have presented ClinicalReTrial, a novel self-evolving agent framework that moves beyond passive clinical trial outcome prediction to enable proactive optimization of clinical trial protocols. By integrating an interpretable, accurate simulator with an autonomous Agent capable of causal reasoning and iterative design refinement, our system not only able to forecast trial success but also generates actionable modifications, including adjusting eligibility criteria, dosing regimens, or endpoint definitions to enhance feasibility and likelihood of success. Evaluated on standardized Tri-alBench benchmark, ClinicalReTrial achieves strong predictive performance while demonstrating the ability to discover significant protocol improvements with clinical best practices.

Our framework has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, the simulation environment’s predictive accuracy creates potential for false improvement signals and missed opportunities, though validation filtering and iterative refinement provide partial mitigation; this constraint could be addressed by integrating future state-of-the-art prediction models as drop-in replacements for the GBDT oracle. Second, the system lacks adaptive convergence detection; 83.9% of trials exhausted the full 5-iteration budget rather than stopping when modification potential plateaus, suggesting the need for learned stopping criteria based on diminishing returns patterns. Third, retrospective case study analysis reveals tactical domain knowledge gaps: while the system excels at strategic-level reasoning, it may struggle with operational specifics such as selecting appropriate biomarkers, anticipating implementation con-straints, and distinguishing when radical simplification outperforms incremental fortification, often over-relying on complexity multiplication where parsimony proves more effective. Future work should prioritize prospective validation in collaboration with clinical trial sponsors, integration of specialized biomarker knowledge bases to address tactical gaps, development of adaptive stopping mechanisms to improve computational efficiency, and expansion to larger-scale evaluation encompassing broader disease areas and trial designs.

Dataset we used to train the prediction models comprises 20,769 clinical trials from TrialBench’s failure reason dataset. Table 9 shows the label distribution across four categories. The class imbalance reflects real-world trial outcomes: enrollment challenges are the most common failure mode (34.8%), followed by efficacy gaps (10.7%), while safety failures are relatively rare (6.7%) due to rigorous preclinical screening. Success cases (47.8%) include trials that completed without major protocol violations or early termination.

Due to computational cost constraints, we randomly select a stratified sample of 60 trials from the test set (20 enrollment, 20 safety, 20 efficacy), ensuring representation across failure modes and trial phases. Table 10 presents the phase composition.

This sentence-level representation preserves granularity essential for aspect-specific modification-ClinicalReTrialAgent can target individual criteria rather than generic protocol summaries.

Graph Features. We incorporate pre-trained molecular and disease encodings to capture pharmacological properties and disease characteristics. Drug Molecular Graphs. Each drug molecule m is represented as a graph G m = (V, E) where nodes v ∈ V are atoms and edges (u, v) ∈ E are bonds. We employ Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) to aggregate neighborhood information over L iterations:

where m

uv ∈ R dmpnn is the message from atom u to atom v at layer l, N (u) denotes neighbors of u, ⊕ denotes concatenation, and W i , W h are learnable transformation matrices. After L message passing iterations, node embeddings are computed as:

(4)

The graph-level drug embedding is obtained via global average pooling:

For trials with multiple drugs, we average their embeddings. The MPNN encoder is pretrained on pharmacokinetic (ADMET) tasks, then fine-tuned on trial outcome labels (details in Appendix A.1). Disease Hierarchical Encoding. Each disease is represented by an ICD-10 code d i following a hierarchical taxonomy with ancestors A(d i ) = {a 1 , a 2 , . . . , a p }. We use Graph-based Attention Model (GRAM) to encode hierarchical disease information. Each code c has a learnable base embedding e c ∈ R dgram . The hierarchical embedding for disease d i is computed as an attention-weighted sum over itself and its ancestors:

where the attention weight α ji measures the relevance of ancestor a j to the current disease d i :

where ϕ(•) : R 2dgram → R is a learnable single-layer network. For trials targeting multiple diseases, we average their embeddings. The GRAM encoder is initialized with the ICD-10 hierarchical ontology, then fine-tuned on historical trial success rates (details in Appendix A.1).

Tabular Features. We encode structured trial metadata through a modular pipeline that processes categorical attributes, demographic constraints, administrative properties, and enrollment characteristics. The pipeline extracts 29 numerical features.

Problem Formulation and Dataset. We formulate clinical trial outcome prediction as a binary classification problem over three distinct failure modes: poor enrollment, safety/drug adverse effect, and drug inefficacy. We train models separately for each failure mode, enabling ClinicalReTrialAgent to target specific causes during protocol optimization. Our experiments utilize the TrialBench dataset (Chen et al., 2025), which contains over 12,000 annotated clinical trials spanning Phase I through Phase IV, with each trial labeled according to outcome. The dataset provides multi-modal features including drug molecular structures, disease ICD-10 codes, eligibility criteria text, trial metadata, and intervention details. Following standard practice to avoid temporal leakage, we partition data chronologically by trial completion year. According to Feature Concatenation and Prediction. All feature modalities are concatenated into a single input vector:

where semicolons denote concatenation. For each failure mode τ ∈ {enrollment, safety, efficacy}, we train a separate LightGBM classifier M τ that predicts trial success probability, optimizing binary cross-entropy loss. The predicted probability ŷ = M τ (x trial ) ∈ [0, 1] serves as the reward signal for evaluating protocol modifications in the agent system.

Model Training and Validation. We employ LightGBM (Ke et al., 2017) for its computational efficiency with high-dimensional sparse features. Three independent models are trained for enrollment, safety, and efficacy failure prediction using cross-validation with early stopping. The trained GBDT models achieve strong predictive performance across all failure modes (PR-AUC > 0.75) with wellcalibrated probability estimates, validating the simulation environment as a reliable proxy for real trial outcomes.

Word-Level Attention Analysis. Figure 5 demonstrates the word-level attention weights captured by BioBERT embeddings in the TrialDura model, visualized through Shapley values. The heatmap reveals that clinical keywords such as “woman,” “contraception,” receive the highest attention weights (0.0208-0.0274), while functional words like prepositions and conjunctions are assigned lower weights. This attention distribution indicates that the model effectively focuses on medically relevant terminology when processing eligibility criteria, suggesting that domain specific language models can automatically identify critical phrases without explicit feature engineering. Sentence-Level Eligibility Weights. Table 6 illustrates a example of sentence-level importance scores within the inclusion criteria for trial NCT01102504, normalized across all eligibility statements, with weighted importance calculated on predict probability shift if masking out each eligibility protocols. The model assigns highest weights (0.20-0.25) to sentences describing acute cerebrovascular events such as “Transient ischemic attack (TIA)” and “Stroke (ipsilaterally to the stenotic artery),” while demographic criteria like age receive minimal attention (0.07). Notably, the quantitative stenosis threshold “> 30% stenosis on initial B-mode ultrasonography imaging” receives substantial weight (0.18), indicating that the model prioritizes disease severity markers and clinical events over basic demographic qualifications when predicting trial outcomes. Encodes Contributions Revealed Through Ablation Analysis. Figure 6 presents the relative importance of different encoders across three prediction tasks through systematic masking experiments. By individually masking each encoder and measuring the resulting PR-AUC drop, we quantify each component’s contribution to enrollment, safety, and efficacy outcome predictions. The analysis reveals task-specific dependency patterns: certain encoders prove critical for particular outcomes, with their removal causing substantial performance degradation, while showing minimal impact on other tasks. This heterogeneous importance distribution demonstrates that different aspects of trial design and patient characteristics drive distinct clinical endpoints. The varying magnitudes of PR-AUC drops across tasks validate the multi-task learning framework’s ability to capture task-specific representations while identifying which shared features are most crucial for each prediction objective.

The Analysis Agent implements a domain-aware ReAct reasoning pipeline adapted by failure mode (enrollment, safety, efficacy). Novel components include adverse event profiling, statistical power assessment, and design-level pivots. Table 13 summarizes failure-mode-specific adaptations.

Role: Clinical researcher classifying eligibility criteria Task: Classify criteria into 4 categories with confidence scores [0-1] Context: Phase: Phase 2 Mechanism: X inhibits Y pathway Endpoint: Measuring Z at 12 weeks Criteria to Classify: Must wait for fellow eye surgery until study completion Any prior participation in drug trials within 12 months Categories:

- PARTICIPATION_BARRIER: Timing/waiting requirements, administrative hurdles • 2. SAFETY_EXCLUSION: Medical risks (allergies, drug interactions, severe conditions) 3. SELECTION_CRITERION: Defines WHO is eligible (disease type, procedure type, demographics) 4. ENRICHMENT_CRITERION: Selects likely responders (biomarkers, mechanism-aligned traits)

For each criterion, assign scores [0-1] to ALL categories, pick PRIMARY (highest), give 1-sentence reason. Output Format: <participation_barrier_score>0.92</participation_barrier_score> <safety_exclusion_score>0.05</safety_exclusion_score> <selection_criterion_score>0.20</selection_criterion_score> <enrichment_criterion_score>0.10</enrichment_criterion_score> <primary_category>PARTICIPATION_BARRIER</primary_category> Waiting requirement for fellow eye surgery is a strong participation barrier with no medical justification.

Role: Clinical researcher evaluating mechanism alignment Task: Check if criteria select mechanism-appropriate patients and detect missing enrichment Questions:

- Do we select patients who HAVE the target condition this mechanism treats? 2. Do we select patients with baseline values allowing measurement of endpoint Y? 3. Are safety exclusions too broad, blocking potential responders?

If missing enrichment (no criteria selecting treatment-responsive patients):

• Propose ONE objective criterion with: measurement method, threshold, timing • Must be measurable (grades/scores/labs), not subjective (“anticipated”/“likely”) Output Format: <mechanism_analysis> Current criteria define cataract surgery candidates but lack enrichment for inflammation severity. Waiting requirement blocks eligible patients without medical benefit. </mechanism_analysis> <missing_enrichment_criterion> Add inclusion: Baseline anterior chamber cell grade $\geq$2+ (SUN criteria) measured within 7 days of enrollment. Selects patients with measurable inflammation for mechanism-aligned response assessment. </missing_enrichment_criterion>

Role: Clinical researcher analyzing safety failures Task: Parse and categorize adverse events for safety redesign Input: Adverse events: Hepatotoxicity (Grade 3, 25%), elevated AST/ALT (Grade 2, 40%) Intervention: Drug X (oral, 100mg daily for 28 days) Mechanism: Inhibits enzyme Y in Z pathway

- SEVERITY CLASSIFICATION: Extract Grade 3-5 events (dose-limiting), Grade 2 (tolerability) 2. ORGAN “aspect_name”: “[dosage|target_primary_outcome|surgical_model|…]”, “aspect_index”: null, “enrollment_impact”: “[Impact symbol]”, “safety_risk_impact”: “[Impact symbol]”, “net_recommendation”: “[MODIFY|ADD]”, “confidence”: 0.XX, “reasoning”: “[Trade-off reasoning]” } ],

“step4_prioritization”: “[6-8 sentences with tiered recommendations (PRIMARY/SECONDARY/TERTIARY), timeline, and confidence level]”, “step5_synthesis”: “[4-6 sentences synthesizing failure analysis with quantification, expected benefits, trade-offs, and overall confidence]” }, “aspect_li”: [ { “aspect_name”: “eligibility/[inclusion|exclusion]_criteria”, “aspect_index”: N, “original_value”: “[Original criterion text]”, “aspect_type”: “list”, “analysis”: { “timestamp”: “YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM:SS”, “failure_analysis”: “[Analysis from step3 trade-off reasoning]”, “impact_level”: “[MAJOR|MINOR|NOT_RELATED]”, “action_type”: “[MODIFY|DELETE]”, “strategy”: “[Strategy from Analysis Agent]”, “confidence”: 0.XX }, “augment”: { “timestamp”: “YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM:SS”, “augment_val_li”: [ “[Augmentation 1]”, “[Augmentation 2]”, “[Augmentation 3]” ] } }, { “aspect_name”: “eligibility/[inclusion|exclusion]_criteria”, “aspect_index”: null, “original_value”: “N/A”, “aspect_type”: “list”, “analysis”: { “timestamp”: “YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM:SS”, “failure_analysis”: “[Analysis for ADD action]”, “impact_level”: “MAJOR”, “action_type”: “ADD”, “strategy”: “[Strategy from Analysis Agent]”, “confidence”: 0.XX }, “augment”: { “timestamp”: “YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM:SS”, “augment_val_li”: [ “[New criterion 1]”, “[New criterion 2]”, “[New criterion 3]” ] } }, { “aspect_name”: “[dosage|target_primary_outcome]”, “aspect_index”: null, “original_value”: “[Original value for string aspect]”, “aspect_type”: “string”, “analysis”: { “timestamp”: “YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM:SS”, “failure_analysis”: “[Analysis for string aspect]”, “impact_level”: “MAJOR”, “action_type”: “MODIFY”, “strategy”: “[Strategy from Analysis Agent]”, “confidence”: 0.XX }, “augment”: { “timestamp”: “YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM:SS”, “augment_val_li”:

We validate ClinicalReTrialAgent’s reasoning against real-world protocol modifications provides critical insight into clinical applicability. We analyze three trial pairs where investigators redesigned and successfully re-executed failed protocols, enabling direct comparison between expert redesign decisions and ClinicalReTrialAgent’s proposals. Each case represents a distinct failure mode: NCT01298752 (poor enrollment), NCT01919190 (safety/adverse effects), and NCT02169336 (efficacy inadequacy).

Poor Enrollment. To validate agent redesign quality against real-world outcomes, we analyze NCT01298752, a Phase 3 trial of Mapracorat (anti-inflammatory ophthalmic suspension) for post-cataract surgery inflammation that failed due to poor enrollment. Sponsored by Bausch & Lomb, the trial was subsequently redesigned and successfully executed as NCT01591161. The primary enrollment barrier in the failed trial was a timing restriction requiring subjects to “wait to undergo cataract surgery on the fellow eye until after the study has been completed”-a constraint that excluded bilateral cataract patients unwilling or unable to delay their second surgery. Both the real-world redesign and ClinicalReTrialAgent correctly identified this as the critical obstacle and proposed its removal. Additionally, both approaches recognized the need for enrichment criteria: the real-world redesign added specific postoperative inflammation thresholds (AC cells ≥ Grade 2) to ensure enrolled patients exhibited measurable inflammation suitable for treatment evaluation, while ClinicalReTrialAgent proposed conceptually similar criteria targeting “mild to moderate inflammation”. However, the agent failed to capture domain-specific refinements present in the real-world redesign, including baseline safety standardization (requiring Grade 0 inflammation at screening) and operational clarity improvements (specifying exclusion of active external ocular disease). These tactical gaps highlight the agent’s limitations in translating strategic insights into clinically precise protocol language.

Safety/Adverse Events. To validate agent redesign quality against real-world outcomes, we analyze NCT01919190, a Phase 4 trial of EXPAREL (liposomal bupivacaine) via TAP infiltration for post-surgical pain in lower abdominal procedures that failed due to severe adverse events (postoperative abdominal hemorrhage, 33.3% incidence). Sponsored by Pacira Pharmaceuticals, the drug was subsequently redesigned and successfully executed as NCT02199574 in a different surgical context. Table 16 compares the real-world redesign with ClinicalReTrialAgent’s proposals. The primary safety issue in the failed trial was postoperative abdominal hemorrhage (33.3% incidence), attributed to excessive systemic exposure from high-volume TAP infiltration in hemorrhage-prone surgical sites. Both the real-world redesign and ClinicalReTrialAgent correctly identified the fundamental need to pivot from an efficacy trial to a PK/safety study and to reduce dosage by 50%, demonstrating strong diagnostic capability and appropriate dose-finding reasoning. However, the real-world approach implemented several structural changes largely absent from or contradicted by the agent’s proposal: radical surgical model change (lower abdominal surgeries → tonsillectomy), eliminating hemorrhageprone anatomical sites entirely rather than attempting to “broaden” or “standardize” the same problematic surgical context; drastic scope reduction to a 12 patient PK characterization study rather than maintaining Phase 4 scale; and dramatic eligibility simplification, removing 6 of 10 complex exclusion criteria (chronic opioid use, metastatic disease, substance abuse, pain medication washout, TAP-specific anatomical concerns) to focus enrollment on the core safety profile.

4.5 Retrospective Case Studies: Real-World ValidationTo validate ClinicalReTrial’s clinical applicability, we analyze trial pairs, where investigators

4.5 Retrospective Case Studies: Real-World Validation

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.