Parallel Universes, Parallel Languages A Comprehensive Study on LLM-based Multilingual Counterfactual Example Generation

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Parallel Universes, Parallel Languages A Comprehensive Study on LLM-based Multilingual Counterfactual Example Generation- ArXiv ID: 2601.00263

- Date: 2026-01-01

- Authors: Qianli Wang, Van Bach Nguyen, Yihong Liu, Fedor Splitt, Nils Feldhus, Christin Seifert, Hinrich Schütze, Sebastian Möller, Vera Schmitt

📝 Abstract

Counterfactuals refer to minimally edited inputs that cause a model's prediction to change, serving as a promising approach to explaining the model's behavior. Large language models (LLMs) excel at generating English counterfactuals and demonstrate multilingual proficiency. However, their effectiveness in generating multilingual counterfactuals remains unclear. To this end, we conduct a comprehensive study on multilingual counterfactuals. We first conduct automatic evaluations on both directly generated counterfactuals in the target languages and those derived via English translation across six languages. Although translation-based counterfactuals offer higher validity than their directly generated counterparts, they demand substantially more modifications and still fall short of matching the quality of the original English counterfactuals. Second, we find the patterns of edits applied to high-resource European-language counterfactuals to be remarkably similar, suggesting that cross-lingual perturbations follow common strategic principles. Third, we identify and categorize four main types of errors that consistently appear in the generated counterfactuals across languages. Finally, we reveal that multilingual counterfactual data augmentation (CDA) yields larger model performance improvements than cross-lingual CDA, especially for lower-resource languages. Yet, the imperfections of the generated counterfactuals limit gains in model performance and robustness.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **Multilingual Counterfactual Generation:** This paper studies how LLMs generate counterfactual examples across multiple languages, akin to rephrasing a story in various languages while preserving its core message.-

Evaluation of Counterfactual Effectiveness: The effectiveness of these counterfactuals is measured using metrics like Label Flip Rate, Similarity, and Perplexity, similar to evaluating essays based on several criteria in a writing competition.

-

Utilization for Model Improvement: Multilingual counterfactuals are used for data augmentation to enhance model performance and robustness, much like learning cooking better by following recipes in different languages.

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

The importance of providing explanations in multiple languages and illuminating the behavior of multilingual models has been increasingly recognized . Counterfactual examples, minimally edited inputs that lead to different model predictions than their original counterparts, shed light on a model’s black-box behavior in a contrastive manner . However, despite significant advancements in counterfactual generation methods and the impressive multilingual capabilities of LLMs , these approaches have been applied almost exclusively to English . Moreover, cross-lingual analyses have revealed systematic behavioral variations between English and non-English contexts , suggesting that English-only counterfactuals are insufficient for capturing the full scope of model behaviors. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of LLMs in generating high-quality multilingual counterfactuals remains an open question.

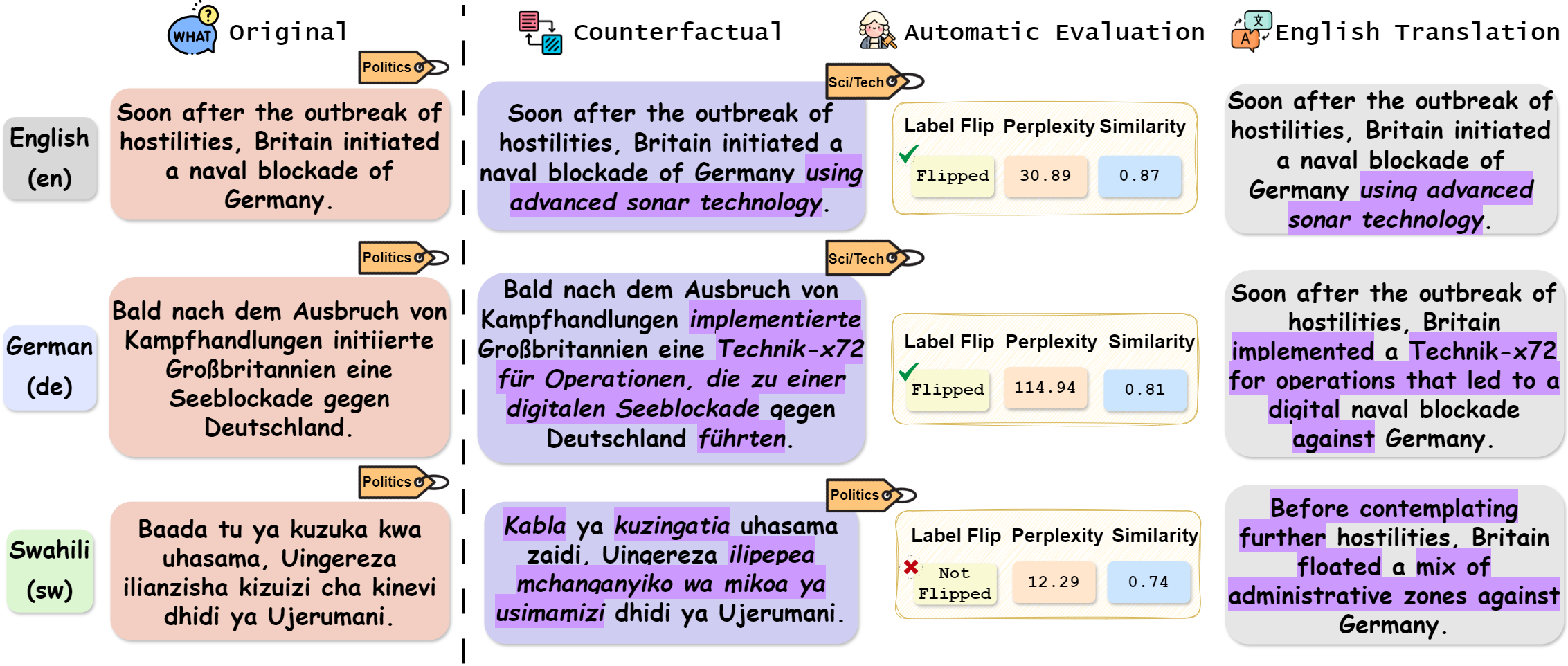

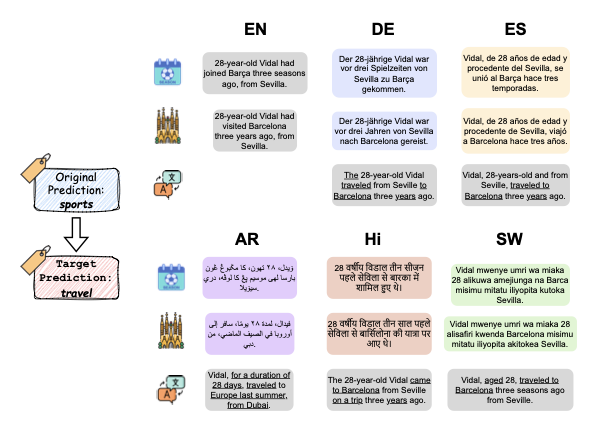

To bridge this gap, we conduct a comprehensive study on multilingual counterfactuals generated by three LLMs of varying sizes across two multilingual datasets, covering six languages: English, Arabic, German, Spanish, Hindi, and Swahili (Figure 1). First, we assess the effectiveness of (1) counterfactuals generated directly in the target language (DG-CFs), and (2) translation-based counterfactuals obtained by translating English counterfactuals (TB-CFs). We observe that DG-CFs in high-resource European languages can frequently successfully change the model prediction, as identified by higher label flip rate (LFR). In particular, English counterfactuals generally surpass the LFR of those in other languages. In comparison, TB-CFs outperform DG-CFs in terms of LFR, although they require substantially more modifications. Moreover, TB-CFs show lower LFR compared to the original English counterfactuals from which they are translated. Second, we investigate the extent to which analogous modifications are applied in counterfactuals across different languages to alter the semantics of the original input. Our analysis demonstrates that input modifications in English, German, and Spanish exhibit a high degree of similarity; specifically, similar words are edited across languages (cf. Figure 24). Third, we report four common error patterns observed in the generated counterfactuals: copy-paste, negation, inconsistency and language confusion. Lastly, we investigate the impact of cross-lingual and multilingual counterfactual data augmentation (CDA) on model performance and robustness . While there are mixed signals regarding performance and robustness gains, multilingual CDA generally achieves better model performance than cross-lingual CDA, particularly for low-resource languages.

Related Work

Counterfactual Example Generation.

produces contrastive edits that shift a model’s output to a specified

alternative prediction . Polyjuice leverages a fine-tuned GPT2 to

determine the type of transformation needed for generating

counterfactual instances . propose a method to determine impactful input

tokens with respect to generated counterfactual examples. generates

counterfactual examples by combining rationalization with span-level

masked language modeling. uncover latent representations in the input

and link them back to observable features to craft counterfactuals. uses

LLMs as pseudo-oracles in a zero-shot setting, guided by important words

generated by the same LLM, to create counterfactual examples. utilizes

feature importance methods to pinpoint the important words that steer

the generation of counterfactual examples. However, all of these methods

have been evaluated exclusively on English datasets, leaving the ability

of LLMs to generate multilingual counterfactuals underexplored.

Counterfactual Explanation Evaluation.

The quality of counterfactuals can be assessed using various automatic evaluation metrics. Label Flip Rate (LFR) is positioned as the primary evaluation metric for assessing the effectiveness and validity of generated counterfactuals . LFR is defined as the percentage of instances in which labels are successfully flipped, relative to the total number of generated counterfactuals. Similarity measures the extent of textual modification, typically quantified by edit distance, required to generate the counterfactual . Diversity quantifies the average pairwise distance between multiple counterfactual examples for a given input . Fluency assesses the degree to which a counterfactual resembles human-written text .

Multilingual Counterfactuals.

propose using multilingual counterfactuals as additional training data for machine translation – an approach known as counterfactual data augmentation (CDA). The counterfactuals employed in CDA flip the ground-truth labels rather than the model predictions, and therefore differ from counterfactual explanations explored in this paper. leverage counterfactuals to evaluate nationality bias across diverse languages. use counterfactuals to measure answer attribution in a bilingual retrieval augmentation generation system. Nevertheless, none of existing work has investigated how well LLMs are capable of generating high-quality multilingual counterfactual explanations.

Experimental Setup

Counterfactual Generation

Our goal is to generate a counterfactual $`\tilde{x}`$ for the input $`x`$, changing the original model prediction $`y`$ to the target label $`\tilde{y}`$. Our goal is to provide a comprehensive overview of multilingual counterfactual explanations rather than to develop a state-of-the-art generation method. Accordingly, we adopt a well-established counterfactual generation approach proposed by , which is based on one-shot Chain-of-Thought prompting 1 and satisfies the following properties:

-

Generated counterfactuals can be used for counterfactual data augmentation (§5.4).

-

Human intervention or additional training of LLMs is not required, thereby ensuring computational feasibility.

-

Generated counterfactuals rely solely on the evaluated LLM to avoid confounding factors, e.g., extrinsic important feature signals .

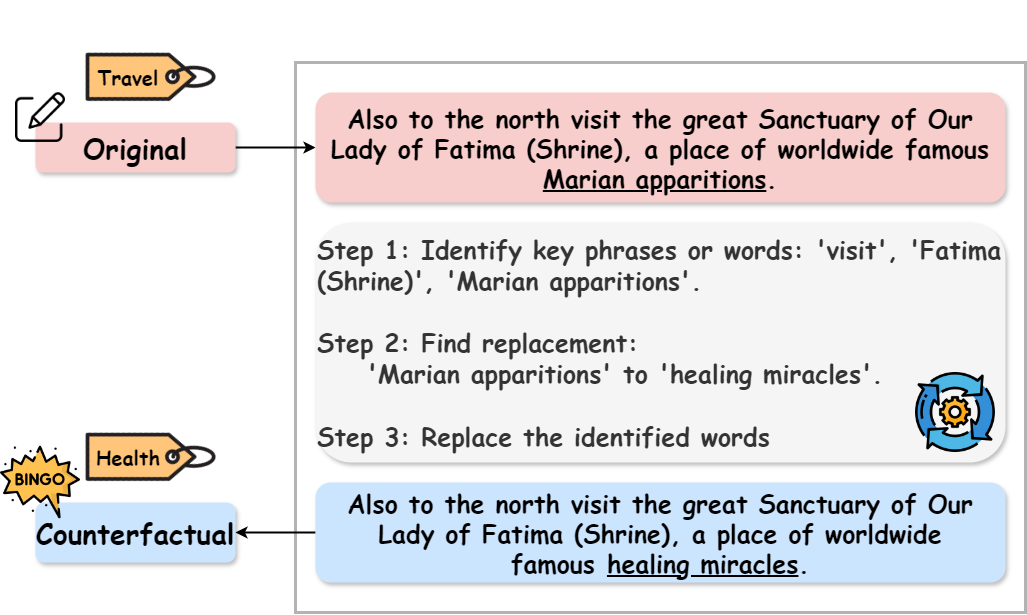

We directly generate counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}`$ (DG-CFs, Table [subtab:direct]) in target languages through a three-step process as shown in Figure 2:

-

Identify the important words in the original input that are most influential in flipping the model’s prediction.

-

Find suitable replacements for these identified words that are likely to lead to the target label.

-

Substitute the original words with the selected replacements to construct the counterfactual.

Furthermore, we investigate the effectiveness of translation-based counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}_{\textsf{en}\text{-}\ell}`$ (TB-CFs, Table [subtab:translation]), where $`\ell \in \{\textsf{ar,de,es,hi,sw}\}`$. Specifically, LLMs first follow the three-step process in Figure 2 to generate counterfactuals in English. We then apply the same LLM to translate these generated counterfactuals into the target languages (Figure 12). Translation quality is evaluated in Appendix 10 by automatic evaluation metrics (§10.1) and human annotators (§10.2).

Datasets

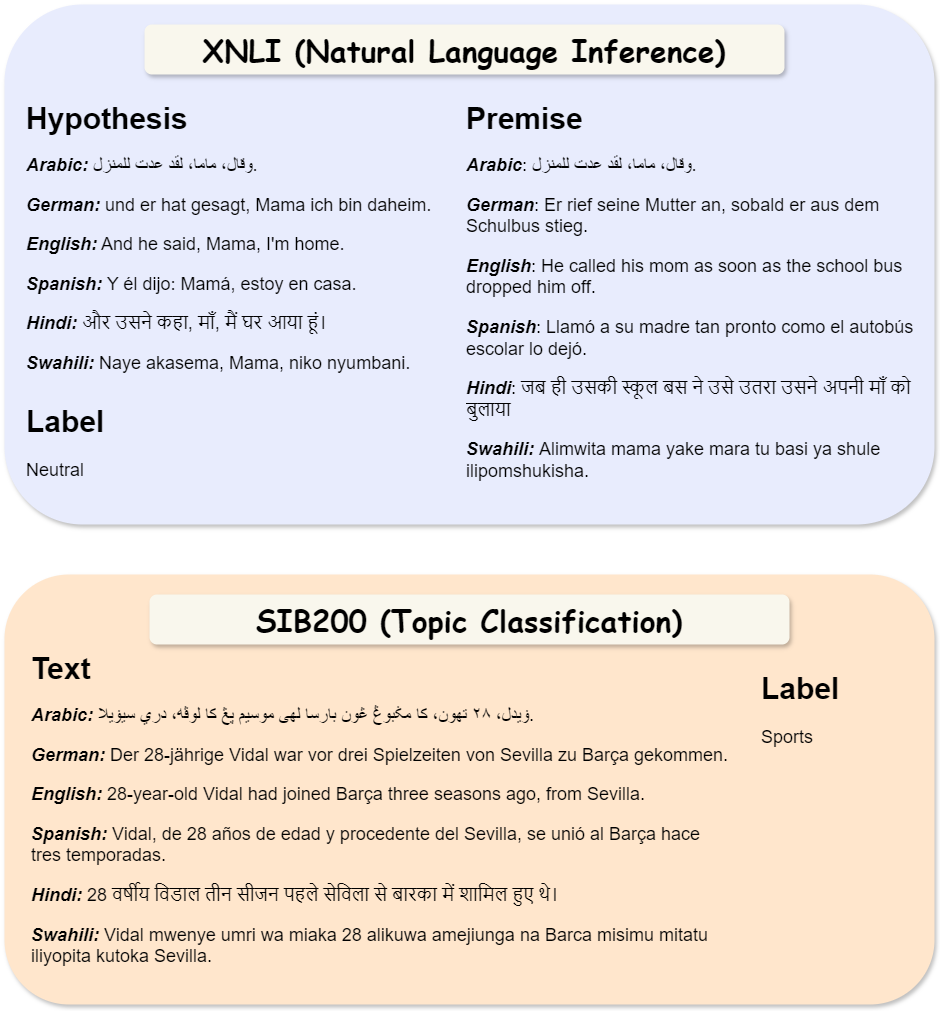

We focus on two widely studied classification tasks in the counterfactual generation literature: natural language inference and topic classification. Accordingly, we select two task-aligned multilingual datasets and evaluate the resulting multilingual counterfactual examples.2

XNLI

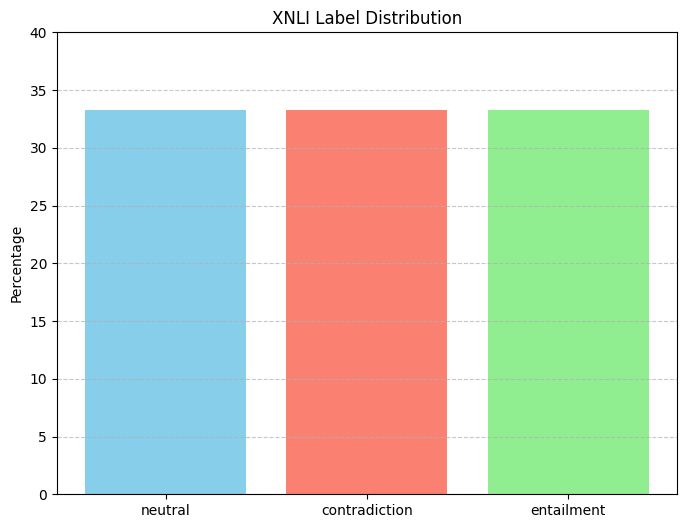

is designed for cross-lingual natural language inference (NLI) tasks. It extends the English MultiNLI corpus by translating into 14 additional languages. XNLI categorizes the relationship between a premise and a hypothesis into entailment, contradiction, or neutral.

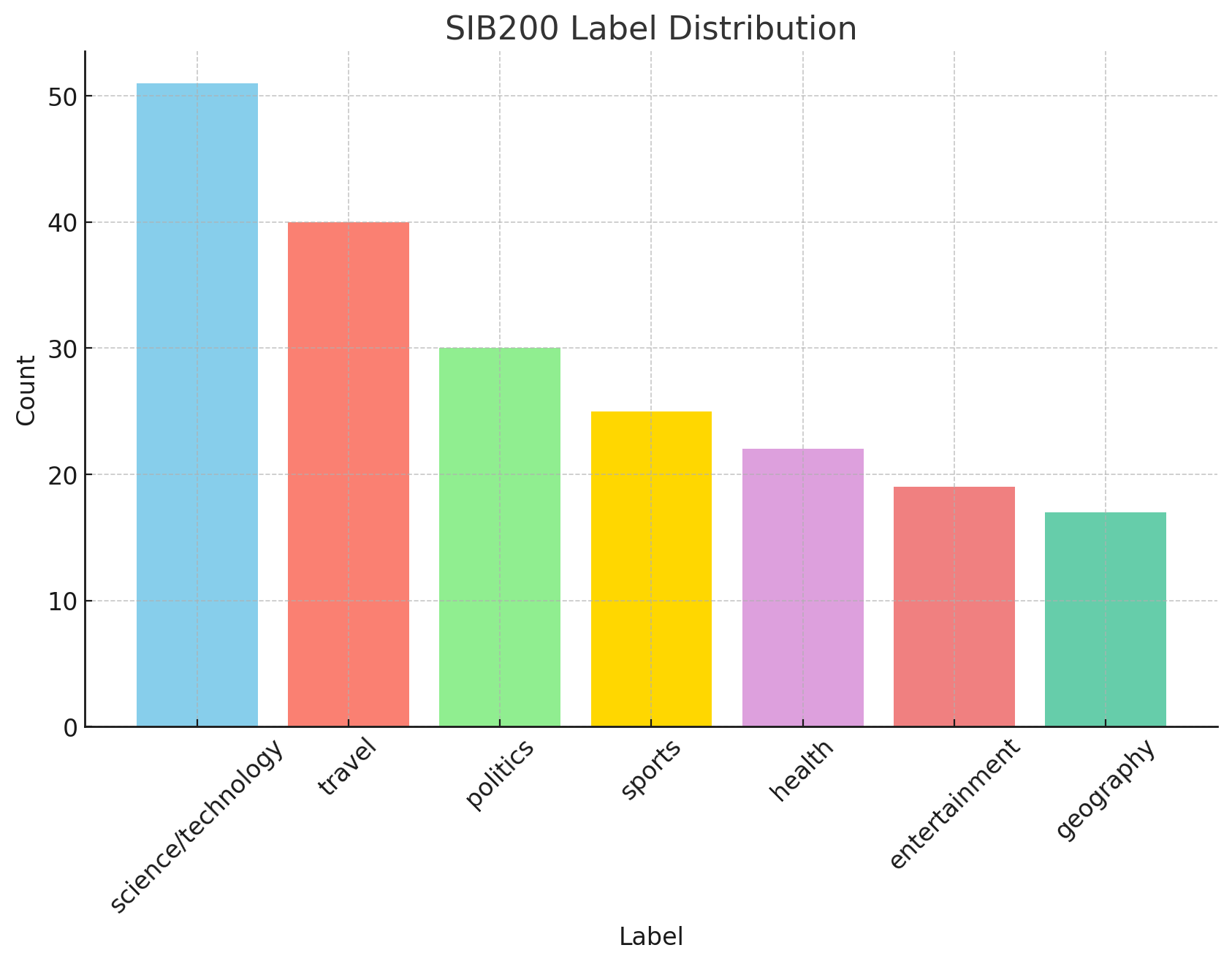

SIB200

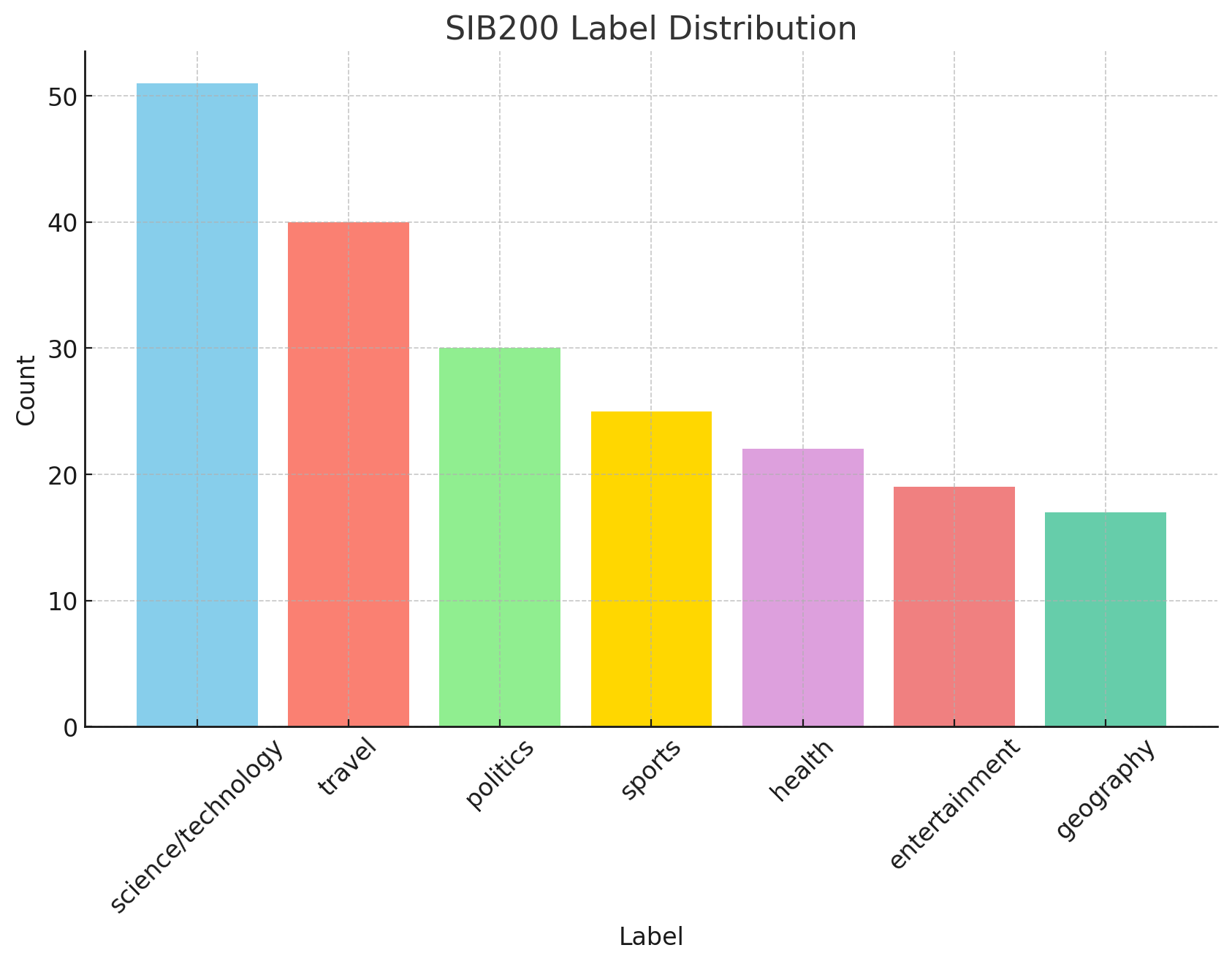

is a large-scale dataset for topic classification across 205 languages. SIB200 categorizes sentences into seven distinct topics: science/technology, travel, politics, sports, health, entertainment, and geography.

Language Selection

We identify six overlapping languages between the XNLI and SIB200 datasets: English, Arabic, German, Spanish, Hindi, and Swahili. These languages are representative of their typological diversity, spanning a spectrum from widely spoken to low-resource languages and encompassing a variety of scripts.

Models

We select three state-of-the-art, open-source, instruction fine-tuned

LLMs with increasing parameter sizes: Qwen2.5-7B , Gemma3-27B ,

Llama3.3-70B .3 These models offer multilingual support and have

been trained on data that include multiple selected languages

(§3.2,

Appendix 9.1.1). Furthermore, in our experiments,

we aim to use counterfactuals to explain a multilingual BERT , which

is fine-tuned on the target dataset

(§3.2).4

Evaluation Setup

Automatic Evaluation

We evaluate the generated multilingual counterfactuals using three automated metrics widely adopted in the literature :

Label Flip Rate (LFR)

quantifies how often counterfactuals lead to changes in their original model predictions . For a dataset containing $`N`$ instances, LFR is calculated as:

\begin{equation*}

LFR = \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^{N} \mathds{1} \big(\mathcal{M}(\tilde{x}_i) \neq \mathcal{M}(x_{i})\big)

\end{equation*}where $`\mathds{1}`$ is the indicator function, which returns 1 if the condition is true and 0 otherwise. $`\mathcal{M}`$ denotes the model to be explained. $`x_{i}`$ represents the original input and $`\tilde{x}_i`$ is the corresponding counterfactual.

Textual Similarity (TS)

The counterfactual $`\tilde{x}`$ should closely resemble the original

input $`x`$ , with smaller distances signifying higher similarity.

Following and , we employ a pretrained multilingual SBERT

$`\mathcal{E}`$5 to capture semantic similarity between inputs:

\begin{equation*}

TS = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \texttt{cosine\_similarity}\Bigl(\mathcal{E}(x_i), \mathcal{E}(\tilde{x}_i)\Bigl)

\end{equation*}Perplexity (PPL)

is the exponential of the average negative log-likelihood computed over a sequence. It measures the naturalness of text distributions and indicates how fluently a model can predict the subsequent word based on preceding words . For a given sequence $`\mathcal{S} = (t_1, t_2, \cdots, t_n)`$, PPL is computed as follows:

\begin{equation*}

PPL(\mathcal{S}) = \exp\left\{\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n} \log{p_{\theta}(t_i|t_{<i})}\right\}

\end{equation*}While GPT2 parameterized by $`\theta`$ is commonly used in the

counterfactual literature to calculate PPL , it is trained on English

data only and is therefore unsuitable for multilingual counterfactual

evaluation. Consequently, we use mGPT-1.3B , which excels at modeling

text distributions and provides coverage across all target languages, to

compute PPL in our experiments.6

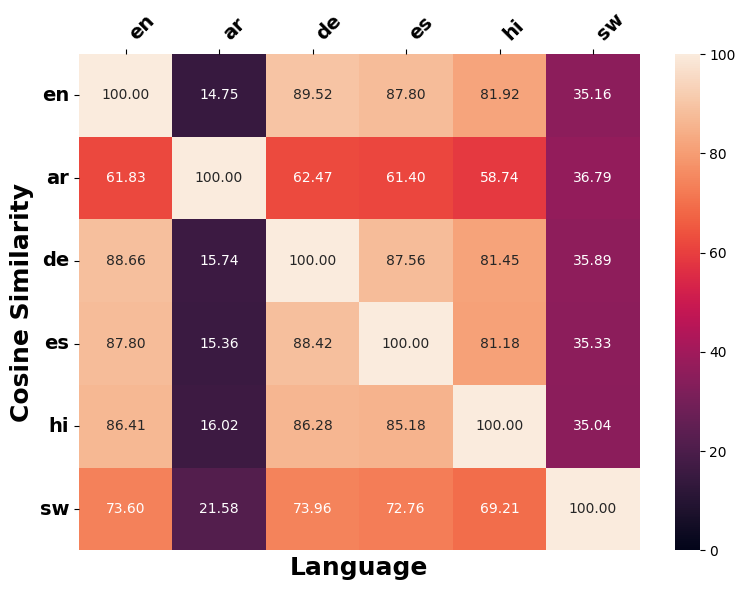

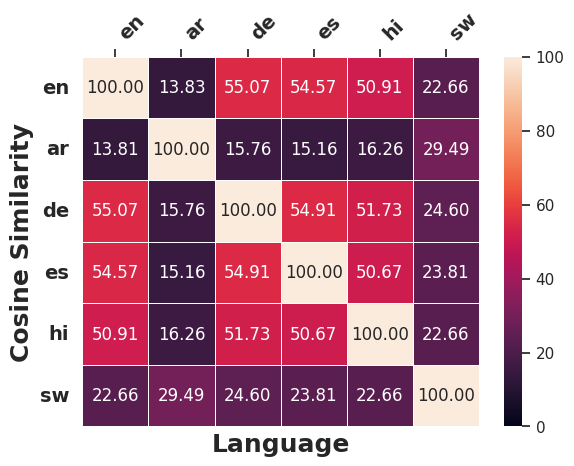

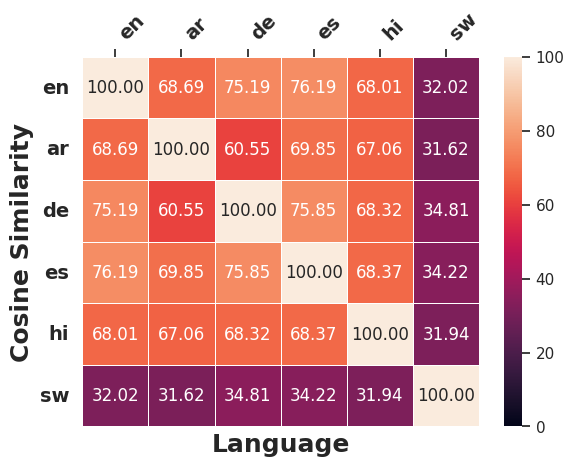

Cross-lingual Edit Similarity

Following the concept of cross-lingual consistency , we investigate the

extent to which cross-lingual modifications are consistently applied in

counterfactuals across different languages to alter the semantics of the

original input.7 To this end, we employ the same multilingual SBERT

deployed in

§5.1 to measure the

sentence embedding similarity by (1) computing pairwise cosine

similarity among directly generated counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}_{\ell}`$

across different target languages $`\ell`$; (2) back-translating the

directly generated counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}_{\ell}`$ from language

$`\ell`$ into English $`\tilde{x}_{\ell\text{-}\textsf{EN}}`$ and

quantifying the pairwise cosine similarity among these (back-translated)

English counterfactuals.

Counterfactual Data Augmentation

To validate whether, and to what extent, counterfactual examples enhance

model performance and robustness , we conduct cross-lingual and

multilingual CDA experiments using a pretrained multilingual BERT .

The baseline for CDA is denoted as $`\mathcal{M}_{base}`$, which is

fine-tuned on

$`D_{\text{base}_{c}}= \left\{\left(x_{i,\textsf{en}}, y_i\right) \mid i \in \mathcal{N}\right\}`$

for cross-lingual CDA, and on

$`D_{\text{base}_{m}}= \left\{\left(x_{i,\ell}, y_i\right) \mid i \in \mathcal{N}, \ell \in \{\textsf{en,ar,de,es,hi,sw}\}\right\}`$

for multilingual CDA, where $`\mathcal{N}`$ denotes the total number of

data points. The counterfactually augmented models $`\mathcal{M}_{c}`$

and $`\mathcal{M}_{m}`$ are fine-tuned using $`D_{\text{base}_{c}}`$ and

$`D_{\text{base}_{m}}`$, respectively, along with their corresponding

counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}_{\ell}`$ in the target languages $`\ell`$,

generated either directly

(§5.4) or through translation

(Appendix 11.3) with different LLMs.

Results

Multilingual Counterfactual Quality

Directly Generated Counterfactuals

Table [subtab:direct] displays that LFR is

dramatically higher for all models on

SIB200 than on

XNLI, reflecting the greater inherent

difficulty of the NLI task. Counterfactuals in English tend to achieve

the highest LFR on both XNLI and

SIB200. On

XNLI, the gap between high- and

low-resource languages widens with model scale, reaching up to

$`16.46\%`$. In contrast, on SIB200,

this gap narrows, where, for instance, counterfactuals in Swahili

generated by Llama3.3-70B attain the highest LFR. Nevertheless,

higher-resource European languages (English, German, and Spanish)

generally exhibit higher LFRs than lower-resource languages (Arabic,

Hindi and Swahili). Furthermore, counterfactuals in Hindi consistently

achieve the best perplexity scores across all three models, indicating

superior fluency, whereas counterfactuals in Arabic are generally less

fluent. Meanwhile, counterfactuals in Arabic involve more extensive

modifications to the original texts indicated by lower textual

similarity, whereas those in Swahili and German are generally less

edited. However, the higher textual similarity for Swahili reflects

fewer LLM edits, resulting in lower LFR. Additionally, no single model

produces counterfactuals that are optimal across every metrics and

language. Likewise, counterfactuals in none of the languages

consistently excel across all evaluation metrics. For example, English

counterfactuals achieve higher LFR, but exhibit lower fluency and

require more edits than those in other languages, underscoring that the

idea of an “optimal” or “suboptimal” language for counterfactual quality

is inherently contextual and metric-dependent.

Translation-based Counterfactuals

Comparison with DG-CFs.

Table [subtab:translation] demonstrates that, in most cases8, TB-CFs $`\tilde{x}_{\textsf{en}\text{-}\ell}`$ yield higher LFR than DG-CFs $`\tilde{x}_\ell`$ in the target language $`\ell`$ (Table [subtab:direct]). The LFR improvement is most pronounced for German and least significant for Hindi, although the validity of counterfactuals in Hindi consistently benefits from the translation. Despite TB-CFs $`\tilde{x}_{\textsf{en}\text{-}\ell}`$ achieving higher LFR compared to DG-CFs $`\tilde{x}_\ell`$, overall, the LFR of $`\tilde{x}_{\textsf{en}\text{-}\ell}`$ is lower than that of the original English counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}_{\textsf{en}}`$. In addition, TB-CFs $`\tilde{x}_{\textsf{en}\text{-}\ell}`$ are generally less similar to the original input than DF-CFs, showing 15.44% lower similarity on average. This difference is due to artifacts introduced by machine translation, and they tend to exhibit lower fluency (38% lower on average) owing to limitations in translation quality.

Correlation between TB-CFs and Machine Translation.

The degree of LFR improvement is weakly positively correlated with the machine translation quality, measured by automatic evaluation (Spearman’s $`\rho=0.27`$, Table [tab:automatic_evaluation_translation]) and by human evaluation (Spearman’s $`\rho=0.07`$, Table [tab:human_evaluation]) (Appendix 10). The weak observed correlations suggest that improvements are driven primarily by the quality of the English counterfactuals, with translation quality contributing only to a limited extent.

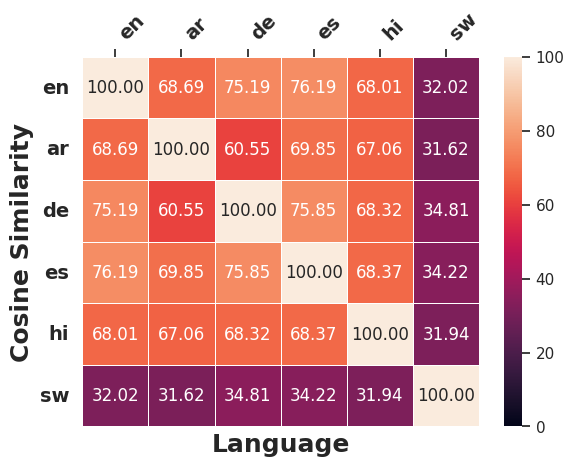

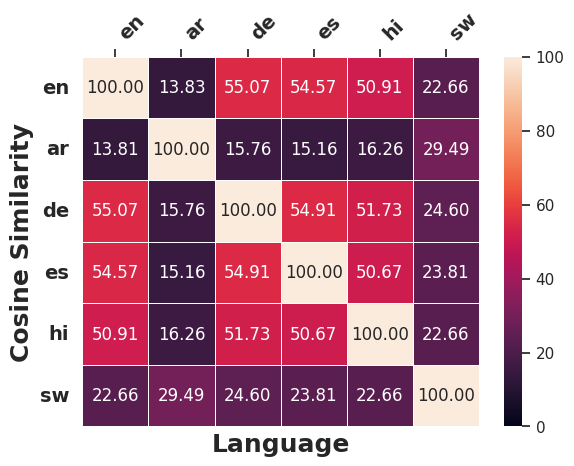

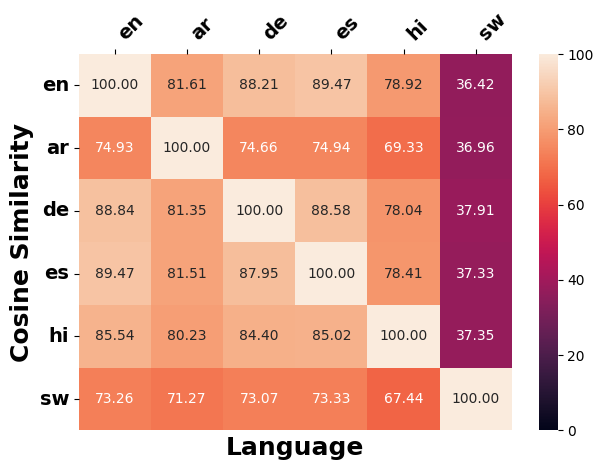

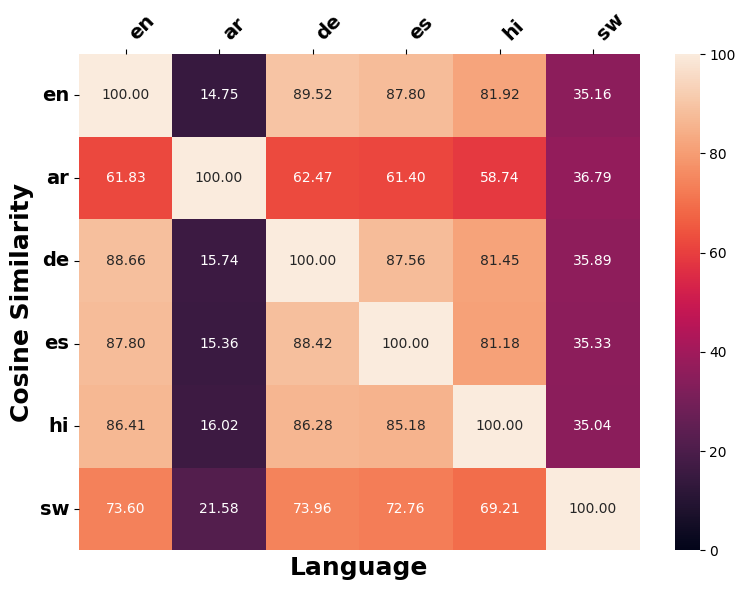

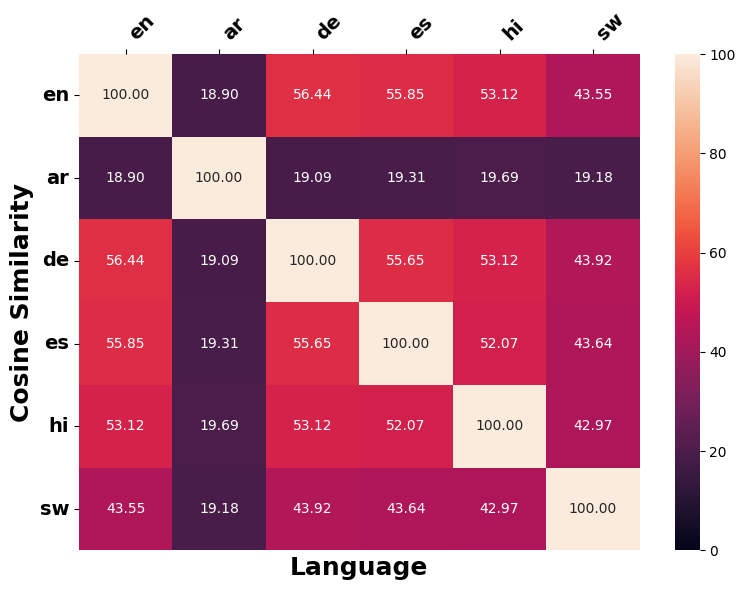

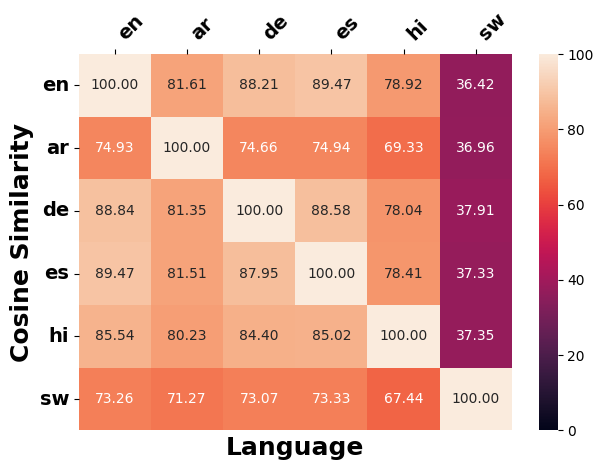

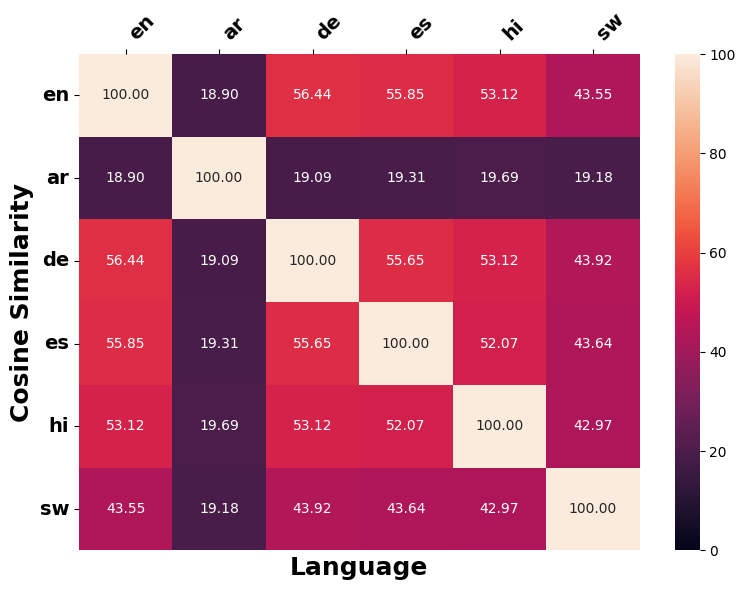

SBERT.Cross-lingual Edit Similarity

Figure 5 and Figure 23 indicate that LLMs generally edit inputs for Swahili and Arabic counterfactuals in a substantially different manner than other languages, as evidenced by lower cosine similarity scores.9 Notably, for European languages (English, German and Spanish), LLMs tend to apply similar modifications to the original input during counterfactual generation (Figure 24), likely because of structural and lexical similarities among these languages (Appendix 11.2.3). Additionally, the edits applied across different languages when generating counterfactuals on SIB200 differ markedly from those on XNLI, as reflected in noticeable differences in cosine similarity scores between the two datasets. This disparity likely stem from SIB200’s focus on topic classification. When a target label is specified, compared to XNLI, there might be more distinct ways to construct valid counterfactuals that elicit the required prediction change.

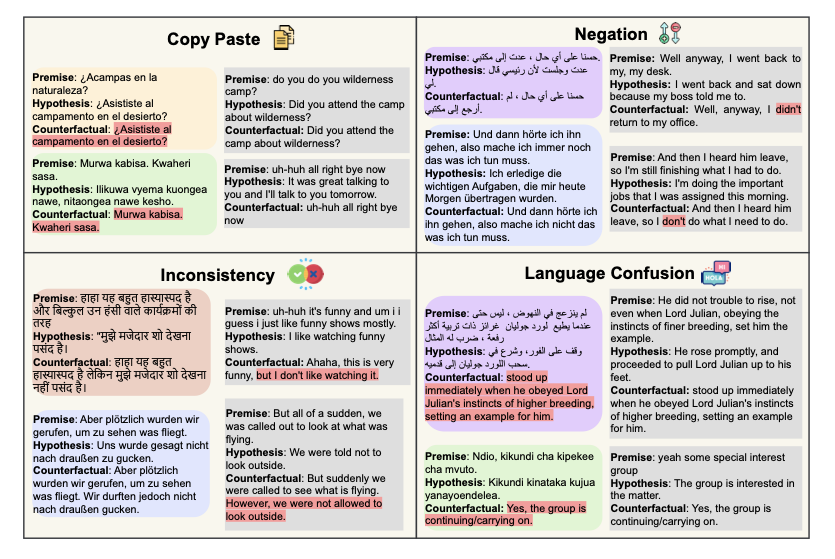

Error Analysis

Generating counterfactuals is not immune to errors, possibly due to the suboptimal instruction-following ability of LLMs and their difficulty in handling fine-grained semantic changes. have identified three common categories of errors in English counterfactuals. We hypothesize that similar issues may arise in multilingual counterfactual generation. Building on this insight, we examine the directly generated counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}_\ell`$ in all target languages, analyzing them both manually and automatically, depending on the type of error. To facilitate our investigation, we translate the counterfactuals into English when necessary and compare them against their original texts. Based on this process, we identify four distinct error types, which we summarize below (see Figure 9 for examples in each error type).

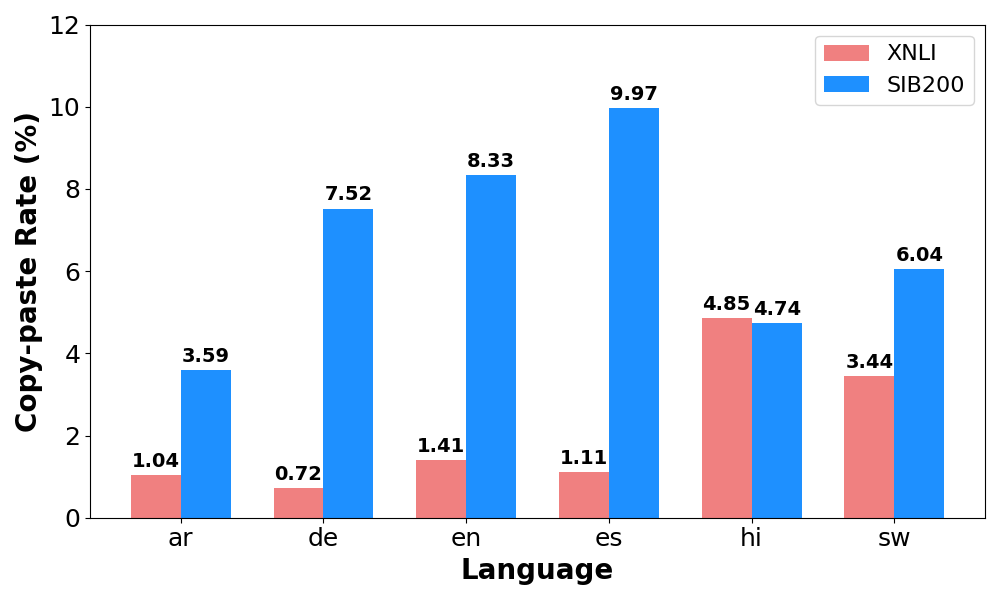

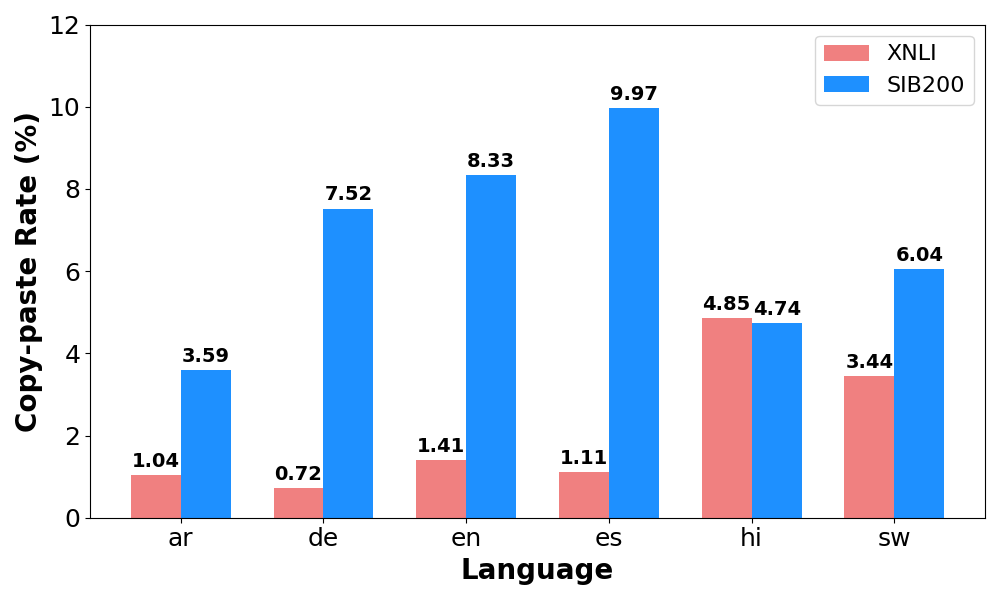

Copy-Paste. When LLMs are prompted to generate counterfactuals by altering the model-predicted label, they occasionally return the original input unchanged as the counterfactual. Figure 6 shows that the copy-paste rate is considerably higher on SIB200 (average: $`6.7\%`$) than on XNLI (average: $`2.1\%`$). However, the trend in two datasets is not consistent across languages. High-resource languages like English and Spanish in SIB200 present higher copy-paste rates. In contrast, lower-resource languages like Hindi and Swahili in XNLI are most affected by the copy-paste issue. A closer inspection suggests that LLMs often struggle to sufficiently revise the input to align with the target label, resulting in incomplete or superficial edits.

Negation. For counterfactual generation, LLMs often attempt to reverse the original meaning by introducing explicit negation while preserving most of the context. However, this strategy frequently fails to trigger the intended label change, resulting in semantically ambiguous or label-preserving outputs . A likely reason is that LLMs may rely on shallow heuristics – negation being a common surface-level cue for meaning reversal learned during pretraining. Especially in languages with simple and explicit negation markers, such as English and German, LLMs tend to perform minimal edits (e.g., adding “not”) rather than making deeper structural changes required for a true semantic shift.

Inconsistency. Counterfactuals may introduce statements that are logically contradictory or incoherent relative to the original input. This often results from the model appending or modifying content without fully reconciling the semantic implications of the added text with the existing context. In such cases, the counterfactual may contain mutually exclusive statements, e.g., simultaneously asserting that an event occurred and that it was prohibited (cf. Figure 9). These inconsistencies highlight the model’s difficulty in preserving global meaning while introducing label-altering edits, particularly when attempting to retain much of the original phrasing.

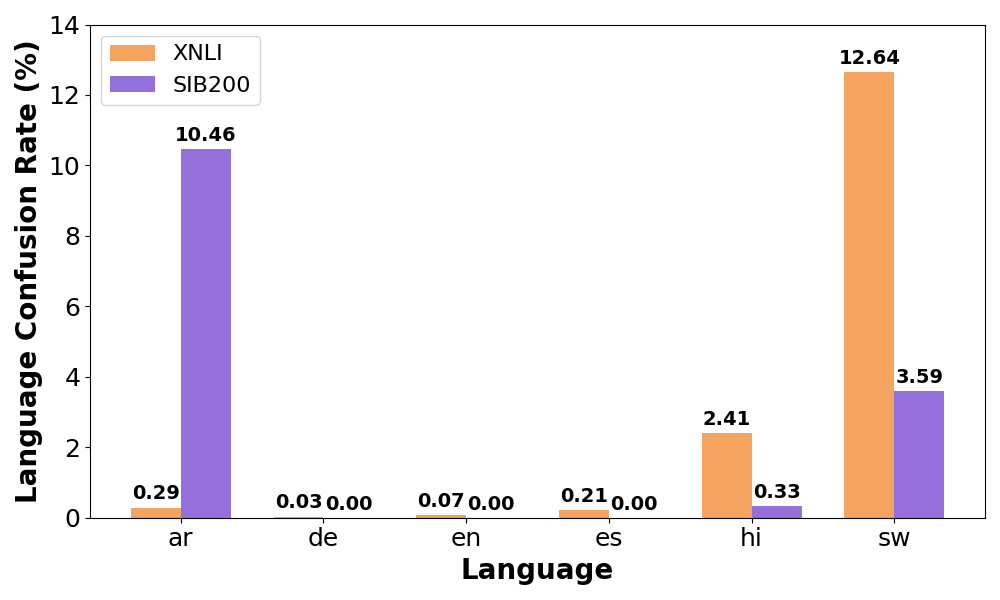

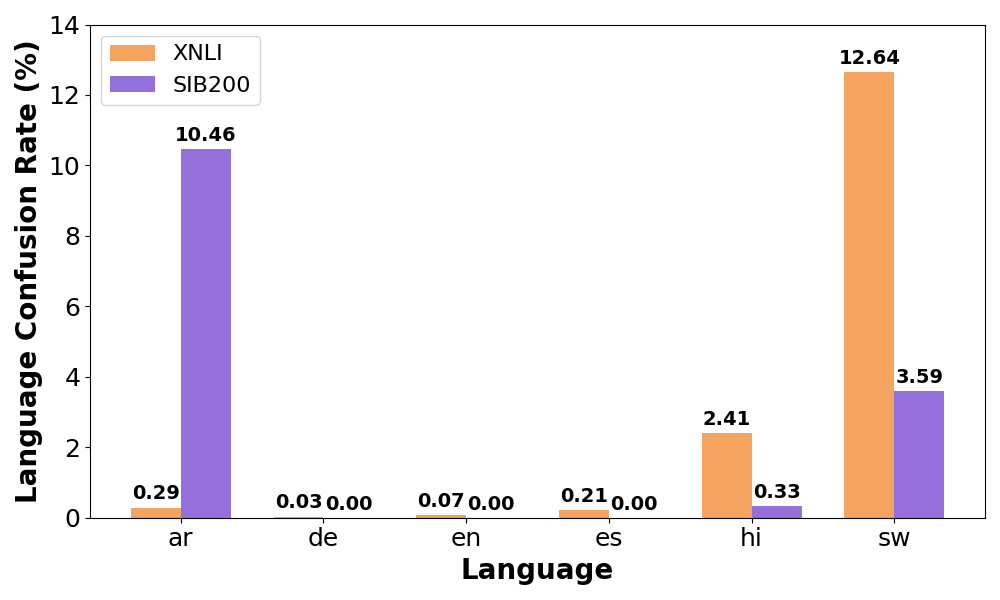

Language Confusion. We further identify the language of directly generated counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}`$ and examine whether it aligns with the intended target language.10 Figure 7 illustrates the language confusion rate across different languages on XNLI and SIB200. Overall, counterfactuals in high-resource languages, i.e., German, English, and Spanish, can be generated consistently in the expected target language. In contrast, when relatively lower-resource languages, such as Arabic or Swahili, are specified as the target language, LLMs frequently misinterpret the prompts11 or default to generate counterfactuals in the predominant language of English .

Counterfactual Data Augmentation

Table [tab:cda] reflects that for the base model $`\mathcal{M}_{base}`$, multilingual CDA generally leads to a substantial improvement in performance compared to cross-lingual CDA across two datasets. This effect is especially compelling for Arabic, with average accuracy gains of $`64.45\%`$, while for English, the improvement is least observable due to its already satisfactory performance in the cross-lingual setting.

For XNLI, cross-lingual CDA enhances model performance only on English, while degrading performance on the other languages. In the context of multilingual CDA, overall, model performance improves across languages other than Swahili. For SIB200, in the cross-lingual setting, CDA generally has an adverse impact on model performance. Meanwhile, although the generated counterfactuals are more effective and valid (Table [tab:automatic_evaluation]), in the multilingual setting, augmenting with these counterfactuals only yields reliable gains in English and Spanish, while it even consistently hampers performance for Swahili. This effect is remarkably pronounced when using smaller LLMs.

The limited performance improvement from augmenting with counterfactuals can be attributed to the imperfection of generated counterfactuals (Figure 9), which stems from both the limited multilingual capabilities of LLMs and suboptimal multilingual counterfactual generation method. We take a close look into how error cases (Figure 9) affect the model performance gains achieved through CDA. Table 4 reveals that, after excluding error cases (copy-paste and language confusion), overall performance improves; however, the magnitude of enhancement varies across languages (Appendix 11.3.5). Furthermore, while counterfactuals for SIB200 often succeed in flipping model predictions, they frequently fail to flip the ground-truth labels due to insufficient revision, an essential requirements for CDA, resulting in noisy labels that can even deteriorate performance .12

Conclusion

In this work, we first conducted automatic evaluations on directly generated counterfactuals in the target languages and translation-based counterfactuals generated by three LLMs across two datasets covering six languages. Our results show that directly generated counterfactuals in high-resource European languages tend to be more valid and effective. Translation-based counterfactuals yield higher LFR than directly generated ones but at the cost of substantially greater editing effort. Nonetheless, these translated variants still fall short of the original English counterfactuals from which they derive. Second, we revealed that the nature and pattern of edits in English, German, and Spanish counterfactuals are strikingly similar, indicating that cross-lingual perturbations follow common strategies. Third, we cataloged four principal error types that emerge in the generated counterfactuals. Of these, the tendency to copy and paste segments from the source text is by far the most pervasive issue across languages and models. Lastly, we extended our study to CDA. Evaluations across languages show that multilingual CDA outperforms cross-lingual CDA, particularly for low-resource languages. However, given that the multilingual counterfactuals are imperfect, CDA does not reliably improve model performance or robustness.

Limitations

We use multilingual sentence embeddings to assess textual similarity between the original input and its counterfactual (§5.1), following . While token-level Levenshtein distance is widely adopted as an alternative , it may not fully capture similarity for non-Latin scripts. This underscores the need for new token-level textual similarity metrics suited to multilingual settings.

We do not exhaustively explore all languages common to SIB200 and XNLI; instead, we select 6 languages spanning from high-resource to low-resource to ensure typological diversity and cover a variety of scripts (§3.2). Thus, expanding the evaluation to more languages and exploring more models with different architectures and sizes are considered as directions for future work.

Since machine translation quality is not strongly correlated with the improvement of counterfactual validity (§5.1.2). Therefore, approaches based on machine translation may not be an optimal method for multilingual counterfactual generation. The quality of multilingual counterfactuals could potentially be considerably improved by adopting post-training methods, such as MAPO , serving as a promising way for future work.

In this work, following prior research on comprehensive studies of English counterfactuals , we focus exclusively on automatic evaluations of multilingual counterfactuals along three dimensions – validity, fluency and minimality (§5.1), rather than on subjective aspects such as usefulness, helpfulness, or coherence of counterfactuals , which can only be assessed through user study. As future work, we plan to conduct a user study to subjectively assess the quality of the multilingual counterfactuals.

Ethics Statement

The participants in the machine translation evaluation (Appendix 10.2) were compensated at or above the minimum wage, in accordance with the standards of our host institutions’ regions. The annotation took each annotator approximately an hour on average.

Author Contributions

Author contributions are listed according to the CRediT taxonomy as follows:

-

QW: Writing, idea conceptualization, experiments and evaluations, analysis, user study, visualization.

-

VBN: Writing, preparation and evaluation of human-annotated counterfactuals for multilingual CDA.

-

YL: Writing and error analysis.

-

FS: Multilingual CDA on test set.

-

NF: Writing – review & editing and supervision.

-

CS: Supervision and review & editing.

-

HS: Supervision and review & editing.

-

SM: Supervision and funding acquisition.

-

VS: Funding acquisition and proof reading.

Acknowledgment

We thank Jing Yang for her insightful feedback on earlier drafts of this paper, valuable suggestions and in-depth discussions. We sincerely thank Pia Wenzel, Zain Alabden Hazzouri, Luis Felipe Villa-Arenas, Cristina España i Bonet, Salano Odari, Innocent Okworo, Sandhya Badiger and Juneja Akhil for evaluating translated texts. This work has been supported by the Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR) as part of the projects BIFOLD 24B and VERANDA (16KIS2047).

Counterfactual Generation

LLMs have demonstrate multilingual capabilities, yet they remain predominantly English-centric due to imbalanced training corpora , resulting in inherent bias toward English. This imbalance can subsequently hinder the models’ proficiency in other languages, often leading to suboptimal performance in non-English contexts . Consequently, we conduct our experiments using English prompts only.

Figure 10 and Figure 11 demonstrate prompt instructions for counterfactual example generation on the XNLI and SIB200 datasets. An example from each dataset is included in the prompt. Figure 12 illustrates the prompt instruction for translating a counterfactual example from English to a target language.

Given two sentences (premise and hypothesis) in {language_dict[language]} and their original relationship, determine whether they entail, contradict, or are neutral to each other. Change the premise with minimal edits to achieve the target relation from the original one and output the edited premise surrounding by <edit>[premise]</edit> in language. Do not make any unnecessary changes.

#####Begin Example####

Original relation: entailment

Premise: A woman is talking to a man.

Hypothesis: Brown-haired woman talking to man with backpack.

Target relation: neutral

Step 1: Identify phrases, words in the premise leading to the entailment relation: ’man’;

Step 2: Change these phrases, words to get neutral relation with minimal changes: ’man’ to ’student’;

Step 3: replace the phrases, words from step 1 in the original text by the phrases, words, sentences in step 2.

Edited premise: <edit>A woman is talking to a student.</edit>

#####End Example#####

Request: Given two sentences (premise and hypothesis) in {language_dict[language]} and their original relationship, determine whether they entail, contradict, or are neutral to each other. Change the premise with minimal edits to achieve the neutral relation from the original one and output the edited premise surrounding by <edit>[premise]</edit> in {language_dict[language]}. Do not make any unnecessary changes. Do not add anything else.

Original relation: {prediction}

Premise: {premise}

Hypothesis: {hypothesis}

Target relation: {target_label}

Edited premise:

Given a sentence in {language_dict[language]} classified as belonging to one of the topics: “science/technology”, “travel”, “politics”, “sports”, “health”, “entertainment”, “geography”. Modify the sentence to change its topic to the specified target topic and output the edited sentence surrounding by <edit>[sentence]</edit> in language. Do not make any unnecessary changes.

#####Begin Example#####

Original topic: sports

Sentence: The athlete set a new record in the marathon.

Target topic: health

Step 1: Identify key phrases or words determining the original topic: ’athlete’, ’record’, ’marathon’.

Step 2: Modify these key phrases or words minimally to reflect the target topic (health): ’athlete’ to ’patient’, ’set a new record’ to ’showed improvement’, ’marathon’ to ’rehabilitation’.

Step 3: Replace the identified words or phrases in the original sentence:

Edited sentence: <edit>The patient showed improvement in the rehabilitation.</edit>

#####End Example#####

Request: Given a sentence in {language_dict[language]} classified as belonging to one of the topics: “science/technology”, “travel”, “politics”, “sports”, “health”, “entertainment”, “geography”. Modify the sentence to change its topic to the specified target topic and output the edited sentence surrounding by <edit>[sentence]</edit> in language. Do not make any unnecessary changes.

Original topic: {prediction}

Sentence: {text}

Target topic: {target_label}

Edited sentence:

You are a professional translator, fluent in English and {language}. Translate the following English text to {language} accurately and naturally, preserving its tone, style, and any cultural nuances. Text to translate: {counterfactual}

Datasets

Dataset Examples

Figure 13 presents parallel examples from the XNLI and SIB200 datasets in Arabic, German, English, Spanish, Hindi and Swahili.

Label Distributions

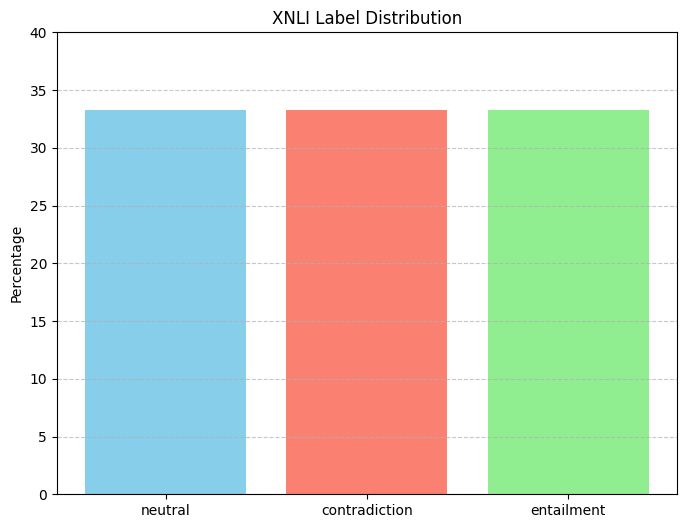

Figure 16 illustrates the label distributions for XNLI and SIB200.

Experiment

Models

LLMs for Counterfactual Generation

Table [tab:used_model] displays three open-source LLMs are utilized for counterfactual generation (§3.3).

Table [tab:language] shows language support

for the selected languages as shown in

§3.2. For Qwen2.5-7B, the model

supports additional languages beyond those listed in

Table [tab:language]; however, these are not

specified in the technical report . Similarly, Gemma3-27B is reported

to support over 140 languages , though the exact supported languages are

not disclosed.

Explained Models

| Language | SIB200 | XNLI |

|---|---|---|

| en | 87.75 | 81.57 |

| de | 86.27 | 71.53 |

| ar | 37.75 | 64.90 |

| es | 86.76 | 74.73 |

| hi | 78.43 | 59.88 |

| sw | 70.10 | 52.25 |

Task performance (in %) of the explained mBERT model across all

selected languages on SIB200 and

XNLI.

Table 1 presents the task

performance of the explained models $`\mathcal{M}_{ft}`$

(§5.1) across all

identified languages on the XNLI and

SIB200 datasets. For

XNLI, we use the fine-tuned mBERT

model, which is publicly available and downloadable directly from

Huggingface13. For SIB200, we

fine-tuned a pretrained mBERT on the

SIB200 training set.

mBERT fine-tuning on SIB200

We fine-tuned bert-base-multilingual-cased14 for 7-way topic

classification

(Figure 15). The input CSV

contains a text column with multilingual content stored as a Python dict

(language$`\rightarrow`$text) and a categorical label. Each row is

expanded so that every language variant becomes its own training example

while inheriting the same label. We split the expanded dataset into 80%

train / 20% validation with a fixed random seed. We train with the

Hugging Face Trainer15 using linear LR schedule with 500 warmup

steps, for 3 epochs, at a learning rate $`2e^{-5}`$, with a batch size

16 and weight decay of 0.01. We evaluate once per epoch and save a

checkpoint at the end of each epoch. The best checkpoint is selected by

macro-$`F_1`$ and restored at the end. Early stopping monitors

macro-$`F_1`$ with a patience of one evaluation round.

| Model | XNLI | SIB200 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Qwen2.5-7B |

9h | 1h | ||

Gemma3-27B |

11h | 8h | ||

Llama3.3-70B |

17h | 13h |

Inference time for counterfactual generation per language using

Qwen2.5-7B, Gemma3-27B, and Llama3.3-70B on

XNLI and

SIB200.

Inference Time

Table 2 displays inference time for

counterfactual generation per language using Qwen2.5-7B, Gemma3-27B,

and Llama3.3-70B on XNLI and

SIB200.

Machine Translation Evaluation

Automatic Evaluation

Given that we explore translation-based counterfactuals (§3.1), we employ three commonly used automatic evaluation metrics to assess translation quality at different levels of granularity, following .

BLEU

measures how many n-grams (contiguous sequences of words) in the candidate translation appear in the reference.

chrF

measures overlap at the character n-gram level and combines precision and recall into a single F-score, better capturing minor orthographic and morphological variations.

XCOMET

is a learned metric that simultaneously perform sentence-level evaluation and error span detection. In addition to providing a single overall score for a translation, XCOMET highlights and categorizes specific errors along with their severity.

All three selected metrics are reference-based. However, since we do not have ground-truth references (i.e., gold-standard counterfactuals in the target languages), we perform back-translation by translating the LLM-translated counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}_{\textsf{en}\text{-}\ell}`$ (§3.1) back into English, yielding $`\tilde{x}_{\text{back}}`$. We then compare $`\tilde{x}_{\text{back}}`$ with the original English counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}_{\textsf{en}}`$ (Table [tab:automatic_evaluation_translation]), known as round-trip translation .

Human Evaluation

To further validate the multilingual counterfactual examples translated by LLMs $`\tilde{x}_{\textsf{en}\text{-}\ell}`$ (§3.1) beyond automatic evaluation metrics, we conducted a human evaluation in the form of Direct Assessment (DA) on a continuous scale from 0 to 100, following . Note that in this user study, we only evaluate the quality of machine translated texts instead of assessing the quality of multilingual counterfactual explanations. We randomly select ($`k=10`$) dataset indices for XNLI and SIB200. For each subset, i.e., model-language pair (Table [tab:automatic_evaluation]), the translated counterfactuals in the target language, generated by the given model for the selected indices, are evaluated by two human annotators. The counterfactuals are presented to annotators in the form of questionnaires. We recruit $`n=10`$ in-house annotators, all of whom are native speakers of one of the selected languages (§3.2). Figure 17 illustrates the annotation guidelines provided to human annotators for evaluating the quality of machine translation texts.

Dear Participants,

Thank you for being part of the annotation team. in this study, we will evaluate machine-translated texts generated by large language models (LLMs) from English source texts. You will be presented with pairs of texts: the original text in English and its translation in one of the following target languages—German, Spanish, Arabic, Hindi, or Swahili.

Your evaluation should be based on how well the translation captures the meaning of the sentence in the target language. The English reference translation is included only to help resolve ambiguities — do not score based on how closely the system-generated translation matches the reference. If the system-generated translation uses different words or phrasing but adequately conveys the meaning, it should not be penalized.

The focus of this evaluation is on how well the system-generated English translation conveys the meaning of the sentence in the target language. Do not penalize translations for awkward or unnatural English phrasing as long as the meaning is adequately preserved. You will use a slider (0–100) to score each translation.

• 0% – No meaning preserved

• 33% – Some meaning preserved

• 66% – Most meaning preserved

• 100% – Adequate translation, all meaning preserved

Please try to be consistent in your use of the scale across all items. Your valuable evaluation willhelp improve the quality of machine translation for endangered languages.

Results

Automatic Evaluation

Table [tab:automatic_evaluation_translation] displays that, overall, Spanish and German translations exhibit higher quality compared to Arabic, Hindi, and Swahili across various evaluation metrics with different levels of granularity (§10.1). We observe a strong correlation between BLEU and XCOMET, with Spearman’s $`\rho`$ of 0.89 for XNLI and 0.77 for SIB200.

Human Evaluation

| Language | IAA | $`p`$-value |

|---|---|---|

| ar | 0.7558 | $`2.93e^{-12}`$ |

| de | 0.5142 | $`2.64e^{-05}`$ |

| es | 0.5940 | $`1.84e^{-06}`$ |

| hi | 0.7440 | $`9.61e^{-12}`$ |

| sw | 0.9005 | $`1.23e^{-22}`$ |

Inter-annotator agreement scores and $`p`$-values across all languages apart from English.

Table [tab:human_evaluation]

delivers direct-assessment (DA scores for back-translated

counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}_{\textsf{en}\text{-}\ell}`$ on

XNLI and

SIB200. Overall, Arabic, Spanish, and

German back-translations achieve good quality. Notably, Qwen2.5-7B

exhibits markedly poorer Swahili translation quality than the other two

models.

Correlation with Automatic Metrics.

Table [tab:correlation] illustrates Spearman’s rank correlation ($`\rho`$) between automatic evaluation metric results and human evaluation results. We observe that BLEU and XCOMET show moderate correlations with human judgments, whereas chrF correlates positively on XNLI but negatively on SIB200.

Agreement.

Table 3 reports inter-annotator agreement (IAA) scores and associated $`p`$-values for all languages (§3.2) except English. Annotators show high agreement for Swahili, whereas German exhibits comparatively low agreement. Nevertheless, the $`p`$-values indicate that the observed agreements are statistically significant.

Evaluation

Perplexity

Table [tab:perplexity] illustrates the perplexity scores of data points across the selected languages (§3.2) from the XNLI and SIB200 datasets. We observe that on XNLI, the Hindi premises and hypotheses exhibit the highest fluency, whereas the English ones exhibit the lowest. On SIB200, the German texts are the most fluent, while the Arabic texts are the least fluent.

Cross-lingual Edit Similarity

Cosine Similarity of Original Inputs

Figure 20 illustrates cosine similarity scores for instances across different language from XNLI and SIB200. We observe that, despite the availability of parallel data from XNLI and SIB200, Swahili texts are generally less similar to those in other languages.

Cosine Similarity of Back-translated Counterfactuals

Figure 23 shows cosine similarity scores for translated counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}_{\ell\text{-}\textsf{en}}`$ in English across different language $`\ell`$ from XNLI and SIB200. Notably, the translated counterfactuals exhibit significantly lower pairwise similarity compared to the multilingual counterfactuals generated prior to translation.

Cross-lingual Counterfactual Examples

To further probe cross-lingual edit behavior beyond pairwise cosine similarity, we qualitatively examine how LLMs modify the original inputs across languages. Figure 24 presents counterfactuals in all selected languages that aim to change the label from sports to travel. Consistent with Figure 23, European languages (English, German, Spanish) show largely parallel edit strategies during counterfactual generation. These modifications underlined in Figure 24 reveal lexical and structural convergence when LLMs edit the original input for counterfactual generation and verbs and nouns are replaced with similar words in most cases (e.g., replacing “join” with “travel” or “visit” and “season” with “year”).

By contrast, the Arabic example employs a markedly different strategy and, in this instance, introduces geographic bias via the insertion of “Dubai”. For Swahili, the model often fails to fully alter the original semantic – e.g., retaining “three reasons”, which should be replaced to remove sport-specific content – resulting in ambiguous labels.

Counterfactual Data Augmentation

Training Data for CDA

For models fine-tuned on XNLI, our training data is randomly sampled from the validation split, while evaluation is conducted on the test split. For SIB200, our training data is randomly sampled from the training split, while evaluation uses the development split. The respective splits were chosen because of their limited sizes.

Counterfactual instances are loaded from pre-computed files, with each counterfactual example paired with its predicted label as determined by the generating LLM. For $`\mathcal{M}_{base}`$, models are trained exclusively on original examples with their ground-truth labels. For CDA, the training data is augmented by including both original instances and their corresponding counterfactual variants with their predicted labels, effectively doubling the dataset size.

Model Training Details

All CDA models are based on bert-base-multilingual-cased and

fine-tuned for sequence classification using AdamW optimizer with cosine

learning rate scheduling, 0.1 warmup ratio, 0.01 weight decay, 4

gradient accumulation steps, and random seed 42. Training parameters are

optimized separately for each dataset and counterfactual generation

model through grid search.

Dataset-Specific Configurations

XNLI models use larger training sets with shorter sequences, while SIB200 models employ smaller training sets with longer training schedules. Maximum training set sizes are constrained by dataset and split selection: 2,400 examples for XNLI (validation split) and 700 examples for SIB200 (training split). Training sizes within these limits vary across models due to grid search optimization.

Counterfactual Model Variations

For SIB200, all best performing models

use identical parameters regardless of counterfactual generation model

or cross-lingual vs. multilingual configuration: 700 training examples,

20 epochs, batch size 8, maximum sequence length 192, and learning rate

8e-06. For XNLI, models trained with

counterfactuals generated by different LLMs exhibit distinct

hyperparameter configurations in our grid search, except for a shared

maximum sequence length of 256. $`\mathcal{M}_c`$ and $`\mathcal{M}_m`$

augmented by counterfactuals generated by Gemma3-27B use identical

parameters compared to baseline models, while models trained with

counterfactuals generated by Qwen2.5-7B and Llama3.3-70B use

different learning rates, batch sizes, and training schedules in the

explored parameter space, as shown in

Table [tab:model_training_params].

| Model | Cross-lingual | Multilingual | ||||||

| Size | Epochs | Batch | LR | Size | Epochs | Batch | LR | |

| ℳbase | 2400 | 8 | 16 | 1e−05 | 2400 | 8 | 16 | 1e−05 |

ℳc/ℳm

(Gemma3-27B) |

2400 | 8 | 16 | 1e−05 | 2400 | 8 | 16 | 1e−05 |

ℳc/ℳm

(Llama3.3-70B) |

2400 | 12 | 24 | 2e−05 | 2000 | 12 | 8 | 2e−05 |

ℳc/ℳm

(Qwen2.5-7B) |

2400 | 8 | 24 | 3e−05 | 2400 | 8 | 24 | 3e−05 |

Human Annotated Counterfactuals

Apart from evaluating base models and counterfactually augmented models

on the test set from the original datasets, we also prepare

human-annotated counterfactuals, which can be considered as

out-of-distribution data. For XNLI, we

extend the English counterfactuals from

SNLI provided by 16 and translate

them into target languages with Llama3.3-70B17 with the same prompt

used in Figure 12. For

SIB200, we ask our in-house annotators

to manually create the English counterfactuals. For those, we keep the

target label distribution as balanced as possible to avoid any label

biases. Similarly, we translate them into target languages with

Llama3.3-70B.

Results

Directly Generated Counterfactual Data Augmentation.

Table [tab:cda_human]

displays the CDA results on human-annotated counterfactuals (§11.3.3). Aligned with the findings on the original dataset (§5.4), multilingual CDA simultaneously yields greater robustness gains, evidenced by higher accuracy, than cross-lingual CDA. On SIB200, the robustness of counterfactually data augmented models generally improves across all languages, with occasional declines in Hindi and Swahili. The gains are more pronounced for cross-lingual CDA, particularly for English, Spanish, and German. For XNLI, CDA reduces model robustness, with a consistent degradation observed on the English subset, whereas for Arabic, Hindi, and Swahili, multilingual CDA results in noticeable robustness enhancements.

Translation-based Counterfactual Data Augmentation.

Since cross-lingual CDA includes only English counterfactuals, we omit these results in Table [tab:cda_translation], as they are identical to Table [tab:cda] and Table [tab:cda_human]. Table [tab:cda_translation] shows that for translation-based counterfactual data augmentation, multilingual CDA yields noticeably better model performance than cross-lingual CDA, particularly for lower-resource languages (Arabic, Hindi and Swahili) – a pattern consistent with our findings for directly generated counterfactual augmentation. Specifically, the cross-lingual CDA generally hampers model robustness, with exceptions for Arabic on XNLI and English on SIB200.

Error Analysis

| Language | CDA Performance |

|---|---|

| en-before | 73.45 |

| en-after | 73.62 (+0.17) |

| ar-before | 64.89 |

| ar-after | 65.26 (+0.37) |

| de-before | 68.42 |

| de-after | 69.07 (+0.65) |

| es-before | 69.94 |

| es-after | 71.12 (+1.18) |

| hi-before | 75.76 |

| hi-after | 78.10 (+2.34) |

| sw-before | 76.77 |

| sw-after | 78.92 (+2.15) |

Counterfactual data augmentation (CDA) performance comparison before and after filtering out error cases (copy-paste and language confusion).

We provide additional evidence showing how error cases affect the model

performance enhancement achieved through counterfactual data

augmentation. While copy-paste and language confusion cases are easily

detectable using tools or regular expressions, the manual recognition of

inconsistency and negation is highly time-consuming. We, therefore,

conducted a small-scale CDA experiment (on

XNLI with counterfactuals generated by

Qwen2.5-7B) that specifically filtered out these easily detectable

cases.

Table 4 reveals that after filtering out error cases (copy-paste and language confusion), model performance is improved across all languages. The improvement on English is limited, since the error cases in English are rather rare. The extent of this improvement is directly related to the percentage of initial error cases. For instance, Hindi and Swahili exhibited higher rates of both copy-paste and language confusion (Figure 9); consequently, after filtering, these languages achieved greater performance gains compared to English or other high-resource European languages.

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)

A Note of Gratitude

The copyright of this content belongs to the respective researchers. We deeply appreciate their hard work and contribution to the advancement of human civilization.-

Prompt instructions and the rationale for using English as the prompt language are provided in Appendix 7. ↩︎

-

Dataset examples and label distributions are presented in Appendix 8. ↩︎

-

Further details about the used models for counterfactual generation and inference time can be found in Appendix 9. ↩︎

-

Information about the explained models and the training process is detailed in Appendix 9.1.2. ↩︎

-

https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/paraphrase-multilingual-MiniLM-L12-v2 ↩︎

-

Average perplexity scores of data points in different target languages across each dataset are provided in Table [tab:perplexity]. ↩︎

-

We instruct LLMs to edit each original input in multiple languages while keeping the target counterfactual label fixed. ↩︎

-

In other cases, impairments in translation-based counterfactual quality may suffer from imperfect translations and limitations in LLMs’ counterfactual generation capabilities, particularly pronounced on XNLI. ↩︎

-

Cosine similarity scores for original input and back-translated counterfactuals $`\tilde{x}_{\ell\text{-}\textsf{en}}`$ in English from XNLI and SIB200, are provided in Appendix 11.2. ↩︎

-

More discussion about the selection of languages for prompts can be found in Appendix 7. ↩︎

-

Further details on CDA, including training-data selection, model training, and additional results evaluated using human-annotated counterfactuals, are offered in Appendix 11.3. ↩︎

-

https://huggingface.co/MayaGalvez/bert-base-multilingual-cased-finetuned-nli ↩︎

-

https://huggingface.co/google-bert/bert-base-multilingual-cased ↩︎

-

https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/main_classes/trainer ↩︎

-

https://github.com/acmi-lab/counterfactually-augmented-data ↩︎

-

We argue that the translation quality should be similar to that shown in Table [tab:automatic_evaluation_translation] and Table [tab:human_evaluation], since we use the same

Llama3.3-70Bmodel, and thus we leave the machine translation evaluation out. ↩︎