Understanding and Steering the Cognitive Behaviors of Reasoning Models at Test-Time

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Understanding and Steering the Cognitive Behaviors of Reasoning Models at Test-Time- ArXiv ID: 2512.24574

- Date: 2025-12-31

- Authors: Zhenyu Zhang, Xiaoxia Wu, Zhongzhu Zhou, Qingyang Wu, Yineng Zhang, Pragaash Ponnusamy, Harikaran Subbaraj, Jue Wang, Shuaiwen Leon Song, Ben Athiwaratkun

📝 Abstract

Large Language Models (LLMs) often rely on long chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning to solve complex tasks. While effective, these trajectories are frequently inefficient, leading to high latency from excessive token generation, or unstable reasoning that alternates between underthinking (shallow, inconsistent steps) and overthinking (repetitive, verbose reasoning). In this work, we study the structure of reasoning trajectories and uncover specialized attention heads that correlate with distinct cognitive behaviors such as verification and backtracking. By lightly intervening on these heads at inference time, we can steer the model away from inefficient modes. Building on this insight, we propose CREST, a training-free method for Cognitive REasoning Steering at Test-time. CREST has two components: (1) an offline calibration step that identifies cognitive heads and derives head-specific steering vectors, and (2) an inference-time procedure that rotates hidden representations to suppress components along those vectors. CREST adaptively suppresses unproductive reasoning behaviors, yielding both higher accuracy and lower computational cost. Across diverse reasoning benchmarks and models, CREST improves accuracy by up to 17.5% while reducing token usage by 37.6%, offering a simple and effective pathway to faster, more reliable LLM reasoning.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **Cognitive Head Discovery**: The paper provides empirical evidence for specific attention heads that correlate with particular reasoning behaviors, offering insights into how cognitive patterns are represented within a model's hidden states. 2. **Test-Time Behavioral Steering**: A plug-and-play activation intervention technique is proposed to steer reasoning behaviors at test time without additional training. 3. **Comprehensive Evaluation**: The method is validated across diverse benchmarks, demonstrating improved reasoning accuracy and reduced token usage.📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

Introduction

Recent advances in Reinforcement Learning (RL)-based training have substantially improved the reasoning capabilities of large language models (LLMs), enabling the emergence of “aha” moments and allowing them to excel in complex tasks such as coding and planning . This capability is largely enabled by extended Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning processes. While effective, the reasoning trajectories generated by LLMs are often suboptimal. From an efficiency perspective, long CoT processes consume significantly more tokens than standard responses, leading to increased latency, especially problematic for on-device applications. In terms of performance, recent studies have shown that LLMs often struggle with overthinking , generating unnecessarily verbose explanations for simple problems, and underthinking , where they halt reasoning prematurely before fully exploring complex solutions. Surprisingly, some work even suggests that effective reasoning can emerge without any explicit thinking process .

To guide and enhance the reasoning process, prior work has primarily focused on directly controlling response length . However, there has been limited exploration of the internal cognitive mechanisms that underlie and drive these reasoning behaviors. Drawing inspiration from cognitive psychology, where deliberate processes such as planning, verification, and backtracking, often associated with System 2 thinking, are known to enhance human problem-solving, we posit that analogous cognitive behaviors can be identified and, importantly, steered within LLMs. In particular, we hypothesize that certain components of the model, such as attention heads, specialize in tracking and modulating these distinct reasoning patterns.

In this work, we categorize reasoning processes into two types: linear reasoning (i.e., step-by-step problem solving) and non-linear reasoning (e.g., backtracking, verification, and other divergent behaviors ). To understand how these behaviors are represented in the activation space, we label individual reasoning steps accordingly and train a simple linear classifier to distinguish between them based on hidden activations. Using linear probes, we identify a small subset of attention heads, referred to as cognitive heads, whose activations are highly predictive of reasoning type. Also, Steering these heads effectively alters the model’s cognitive trajectory without additional training.

Based on these findings, we introduce CREST (Cognitive

REasoning Steering at Test-time), a training-free framework

for dynamically adjusting reasoning behaviors during inference.

CREST operates by first performing a simple offline calibration to

identify cognitive heads and compute steering vectors from

representative reasoning examples. Then, during test-time, it uses

activation interventions based on these vectors to adaptively guide the

model’s reasoning trajectory, suppressing inefficient cognitive modes

and encouraging effective reasoning behavior. Importantly, CREST is

compatible with a wide range of pre-trained LLMs and does not require

any task-specific retraining or gradient updates, making it highly

scalable and practical for real-world applications. And the test-time

steering incurs negligible overhead, achieving matching throughput while

reducing token consumption, thereby leading to an overall end-to-end

efficiency gain.

In summary, our key contributions are as follows: (i) Cognitive Head

Discovery: We provide empirical evidence for the existence of

cognitive attention heads that correlate with specific reasoning

behaviors, offering new interpretability into how cognitive patterns are

represented within a model’s hidden states. (ii) Test-Time Behavioral

Steering: We propose a plug-and-play activation intervention technique

that enables test-time steering of reasoning behaviors without

additional training. (iii) Comprehensive Evaluation: We validate our

method across a diverse reasoning benchmarks, including MATH500, AMC23,

AIME, LiveCodeBench, GPQA-D and Calender Planning, demonstrating that

CREST not only enhances reasoning accuracy (up to 17.50%, R1-1.5B on

AMC23) but also substantially reduces token usage (up to 37.60%, R1-1.5B

on AMC23).

Related Works

We organized prior research into three categories and move more related works in Appendix [sec:extend_related_work].

Reasoning Models. Early chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting and self-consistency decoding demonstrated that sampling diverse reasoning paths and selecting the majority answer improves accuracy. Structured search frameworks extend this idea: Tree-of-Thought , Graph-of-Thought , and Forest-of-Thought . Recent “thinking” model releases like OpenAI’s o-series , Anthropic’s Claude-3.7-Sonnet-Thinking , and Google’s Gemini-2.5-Flash , alongside competitive open-source models such as DeepSeek-R1 , Phi-4-Reasoning , and Qwen3 . These advances enhance models’ reasoning abilities and create new possibilities for in-depth analysis of their internal mechanisms.

Cognitive Behaviors in LLMs. Recent work defines cognitive behaviors as recurring patterns in reasoning traces—such as verification, backtracking, or sub-goal planning—that correlate with accuracy . These mirror human problem-solving heuristics and motivate methods that explicitly instill similar behaviors in LLMs . Our work extends this line by identifying internal attention heads linked to such behaviors.

Improving Test-Time Reasoning. Inference-time methods enhance

reasoning without retraining. Notable approaches include: (i) adaptive

compute control, which dynamically allocates tokens , and (ii) direct

trace manipulation, which edits or compresses chains-of-thought . More

recently, activation editing methods steer hidden representations

directly . Our approach, CREST, advances this strand by identifying

cognitive attention heads and demonstrating targeted head-level

interventions that improve efficiency while providing new

interpretability insights.

Dissecting and Modulating Cognitive Patterns in Reasoning

In this section, we examine how reasoning models exhibit and internalize cognitive behaviors, with a particular focus on non-linear thinking patterns such as verification, subgoal formation, and backtracking. We begin in Section 3.1 by identifying and categorizing these behaviors at the level of individual reasoning steps. Section [sec:prob] then investigates how such behaviors are reflected in the internal activations of attention heads, revealing a subset, namely, cognitive heads that reliably encode non-linear reasoning. Finally, in Section 3.3, we demonstrate that these heads can be directly manipulated at test time to steer the model’s reasoning trajectory, offering a mechanism for fine-grained control over complex reasoning without retraining.

Cognitive Behaviors in Reasoning Models

O1-like LLMs solve problems through extended chain-of-thought reasoning,

often exhibiting non-linear patterns that diverge from traditional

step-by-step reasoning. These non-linear trajectories (e.g.,

backtracking, verification, subgoal setting and backward chaining)

closely mirror human cognitive behaviors and enhance the model’s ability

to tackle complex problem-solving tasks . To analyze cognitive

behaviors, we segment the reasoning process, which is typically bounded

by the <think> and </think> markers tokens into discrete reasoning

steps, each delimited by the token sequence

“$`\backslash n \backslash n`$’’. We then categorize each reasoning step

into one of two types using keyword matching: Non-linear Reasoning,

if the reasoning step contains any keyword from a predefined set (e.g.,

$`\{\mathrm{Wait}, \mathrm{Alternatively}\}`$; full list in

Appendix 8.1), it is labeled as non-linear;

otherwise, it is classified as a Linear Reasoning step. We denote a

single reasoning step, composed of multiple tokens, as $`\mathrm{S}`$,

and use $`\mathrm{S}^l`$ and $`\mathrm{S}^n`$ to represent linear and

non-linear reasoning steps, respectively.

Identifying Attention Heads of Cognitive Behaviors

Analyzing cognitive behaviors during reasoning is inherently challenging, as for the same behavior, such as verification, can manifest differently across the token space, depending on the sample’s context and the underlying reasoning pattern. Intuitively, these behaviors often involve long-range token interactions, where the model retrieves and re-evaluates previous reasoning steps. Meanwhile, recent studies have shown that attention heads frequently perform distinct and interpretable functions, such as tracking, factual retrieval, and position alignment. This points toward a modular architecture in which specific heads may specialize in different cognitive sub-tasks. Motivated by this insight, we conduct a preliminary study and identify attention heads that are strongly correlated with cognitive behaviors during reasoning.

/>

/>

Setup. We begin by randomly sampling 500 training examples from the

MATH‑500 benchmark and running end‑to‑end inference with the

DeepSeek‑R1‑Distill‑Qwen‑1.5B model. Crucially, we define a “step”

as the contiguous chunk of reasoning text between two occurrences of the

special delimiter token \n\n.

-

Segment. For every prompt, split the chain-of-thought at the delimiter

\n\n, producing $`k`$ segments $`\{s_1,s_2,\ldots,s_k\}`$. Because the delimiter is kept,\n\nis the final token of each segment, so every $`s_\ell`$ (with $`\ell=1,\dots,k`$) represents one discrete thinking step. -

Embed each step. Re-run inference on the chain-of-thought $`\{s_1, s_2, ..., s_k\}`$ as one single prefill and capture the hidden state at the segment-terminating

\n\ntoken. Treat this vector as a compact summary of the preceding tokens, and extract the post-attention activationsMATH\begin{equation} a^{i,j}_{s_k}\in\mathbb{R}^{d}, \qquad i\!=\!1\ldots H,\; j\!=\!1\ldots L, \label{eq:activation} \end{equation}Click to expand and view morewhere $`i`$ indexes heads and $`j`$ layers. Thus, $`a^{i,j}_{s_k}`$ represents the contextual embedding of the delimiter token (

\n\n) at the end of segment $`s_k`$. -

Label & probe. Mark each step as linear ($`y_{s_k}=0`$) or non-linear ($`y_{s_k}=1`$). For every head $`(i,j)`$ fit a linear probe $`\theta^{i,j} \;=\; \arg\min_{\theta} \mathbb{E}\Bigl[ f\bigl( y_{s_k}, \sigma(\theta^{\!\top} a^{i,j}_{s_k}) \bigr) \Bigr],\label{eq:min-prob}`$ where $`\sigma`$ is the sigmoid and $`f`$ is mean-squared error loss function. See the training details in Appendix.

The resulting probes pinpoint heads whose activations best distinguish linear from non-linear reasoning and supply the foundation for the calibration and steering stages that follow.

Across multiple prompts. For each prompt $`\ell`$, segmentation yields $`k_\ell`$ steps $`S^{(\ell)}=\{s^{(\ell)}_1,\dots,s^{(\ell)}_{k_\ell}\}`$. Collectively these form the global set $`\mathcal{S}=\bigcup_{\ell=1}^{n} S^{(\ell)}`$, whose size is $`|\mathcal{S}|=\sum_{\ell=1}^{n} k_\ell`$. Every $`S^{(\ell)}\in\mathcal{S}`$ is embedded, labeled, and probed exactly as described above, so all downstream analyses operate on the full collection of $`\sum_{ \ell=1}^{n}k_ \ell`$ reasoning segments.We define $`a^{i,j}_{s_k^{(\ell)}}`$ for prompt $`\ell`$.

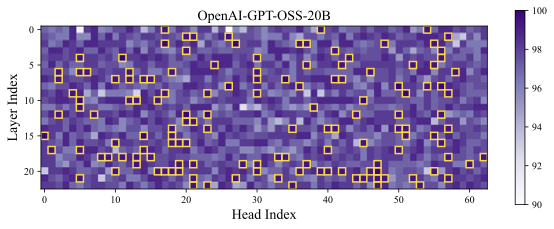

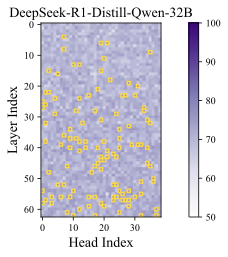

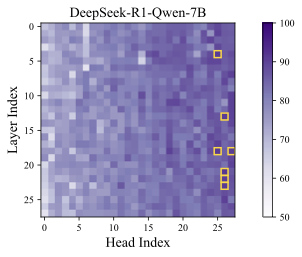

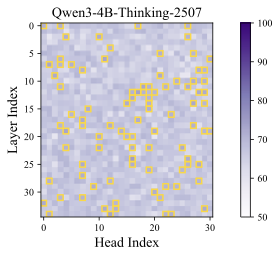

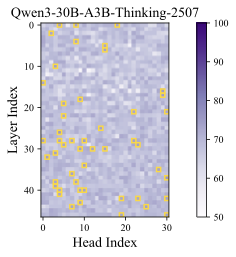

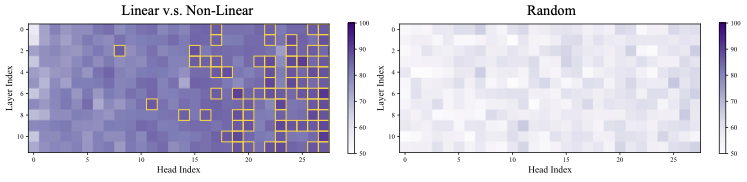

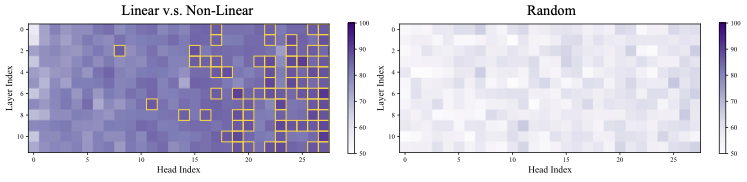

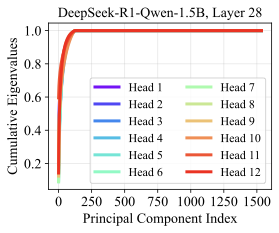

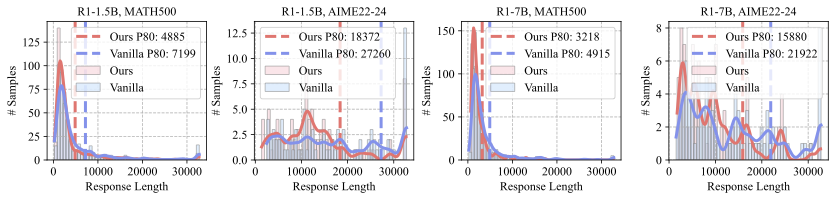

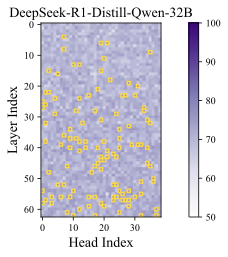

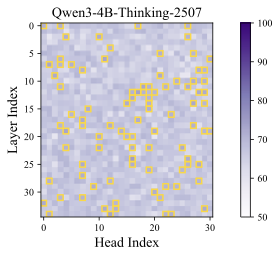

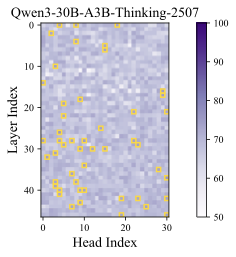

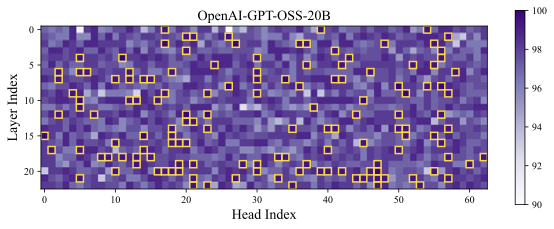

Results. The classification accuracy is shown in Figure 1, with additional results across different models and datasets provided in Appendix 9.1. As a sanity check, we repeat the probing procedure on randomly sampled tokens, shown in the right part of Figure1, where the classification accuracy remains near chance level—indicating no distinguishable signal. In contrast, the left subfigure reveals that certain attention heads achieve significantly higher accuracy. We refer to these as Cognitive Heads, while the remaining are treated as standard heads. Notably, cognitive heads are more prevalent in deeper layers, which is aligned with the expectation that deeper layers capture higher-level semantic features and shallow layers encode token-level features . Some cognitive heads also emerge in middle layers, suggesting a distributed emergence of cognitive functionality across the model.

Manipulating Cognitive Behaviors via Activation Intervention

r0.26  style=“width:100.0%” />

style=“width:100.0%” />

We then investigate whether nonlinear chains of thought can be modulated at test time by directly editing the activations of the most “cognitive” attention heads, following the methodology of .

Prototype construction. With the definition in Setup. For a prompt, we have $`N_\ell = \sum_{k=1}^{|S^{(\ell)}|}\mathbb{I}[y_{s_k^{(\ell)}}=1]`$ non-linear thoughts. With $`v_\ell^{i,j} = \frac{1}{N_\ell} \sum_{k=1}^{|S^{(\ell)}|}a^{i,j}_{s_k^{(\ell)}}\, \mathbb{I}[y_{s_k^{(\ell)}}=1]`$ defined as non-linear average activation for $`\ell`$-th prompt, we form a head-specific vector capturing the average pattern of nonlinear reasoning:

\begin{align}

v^{i,j} = \frac{1}{N}

\sum_{\ell=1}^{n}N_\ell\,v_\ell^{i,j} \quad \text{with} \quad N = \sum_{\ell=1}^{n}N_\ell,

\label{sec:activate-ave}

\end{align}Thus, $`v^{i,j}`$ represents the mean activation across all non-linear steps.

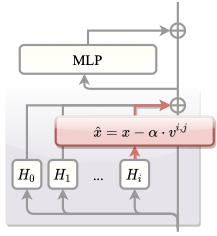

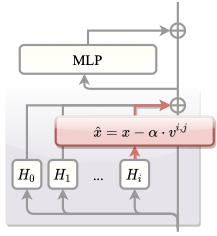

Online intervention. As shown in

Figure [fig:framework], we pause after each

reasoning step (i.e., after generating \n\n), select the top 7% of

attention heads (ranked by the classification‐accuracy metric

in equation [eq:min-prob]), and modify their

activations via

\begin{equation}

\hat{x}^{i,j}

= x^{i,j} - \alpha\,v^{i,j}

\label{eq:keyfunc1}

\end{equation}Here, $`\alpha`$ is a tunable scalar controlling intervention strength:

$`\alpha > 0`$ attenuates nonlinear behavior, while $`\alpha < 0`$

amplifies it. Notably, $`x^{i,j}`$ corresponds to the post-attention

state at inference, whereas $`v^{i,j}`$ summarizes activation at \n\n

positions.

style="width:90.0%" />

style="width:90.0%" />

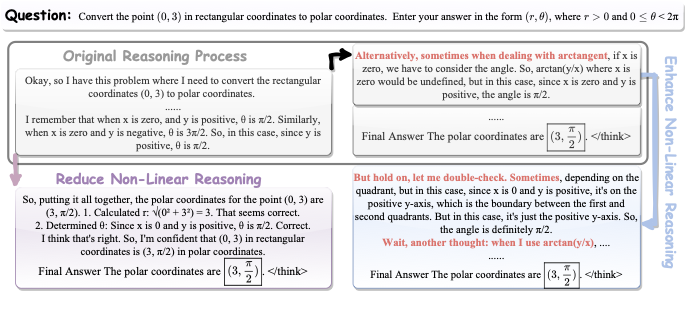

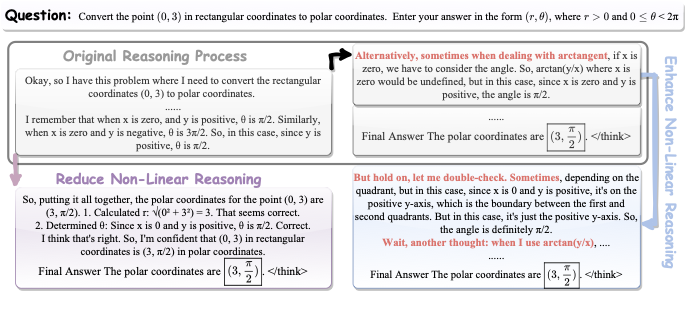

As shown in Figure 2, we pause the reasoning process at Step 9, during which all previous steps followed a linear reasoning trajectory. In the original process, the subsequent step initiates a non-linear reasoning pattern—specifically, a backward chaining behavior —starting with the word “alternatively.” However, after applying activation intervention to suppress non-linear reasoning, the model continues along a linear trajectory and still arrives at the correct final answer. Conversely, we pause the model at Step 10—after it completes a non-linear segment and resumes linear reasoning. In this case, we enhance the non-linear component via activation intervention, causing the model to continue along a non-linear path instead.

r0.42  style=“width:75.0%” />

style=“width:75.0%” />

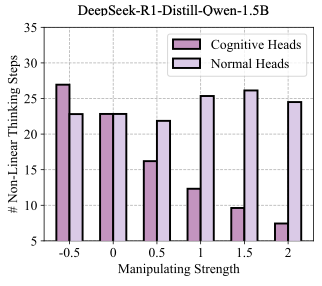

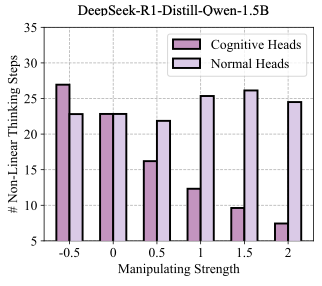

While all versions of the reasoning process ultimately produce the correct final answer, they differ significantly in trajectory length: the original process takes 17 steps, the reduced non-linear path takes only 12 steps, and the enhanced non-linear path extends to 45 steps, implying potential redundancy in current reasoning processes. To further quantify the effects of the intervention, we collect statistical results from the intervention process. Using 100 samples from the MATH500 test set, we observe that the DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-1.5B model takes an average of 22.83 steps to complete the reasoning process. When varying the intervention strength, the number of non-linear reasoning steps adjusts accordingly. In contrast, when applying the same manipulation to non-cognitive (i.e., normal) heads—specifically, the bottom 7% of attention heads with the lowest classification accuracy—the number of reasoning steps remains largely unchanged across different intervention strengths, as shown in Figure [fig:activation_intervention_stat]. These results support the existence of cognitive attention heads and demonstrate the feasibility of manipulating cognitive behaviors during reasoning.

CREST: Cognitive REasoning Steering at Test-time

As observed in the previous section, the model is able to arrive at the correct final answer with fewer non-linear reasoning steps, suggesting the presence of redundant reasoning that hinders end-to-end efficiency. Motivated by these insights, we propose a training-free strategy to adaptively adjust the reasoning process during inference. Our framework consists of two main processes: an offline calibration stage, along with a test-time steering stage.

Offline Calibration

We perform the following two steps to process the head vectors for controlling the reasoning process. It is worth noting that this offline calibration stage is a one-shot procedure, requiring only negligible cost compared to LLM training and incurring no additional latency during subsequent inference.

Identifying cognitive heads.

We begin by locating the cognitive attention heads that matter most for reasoning, details as follows:

-

Calibration dataset and Probing. As describe in Setup of Section [sec:cross-seq], we draw some training samples, embed each step, labeled, and probe to every attention head and rank them by accuracy.

-

Selection. Keep the top $`10\%`$ of heads. For each retained head $`(i,j)`$, we pre-compute $`v^{i,j}`$ as defined in 3.3, the average hidden state across the non-linear reasoning steps.

Aligning head-specific vectors via low-rank projection.

r0.42  />

/>

Since the head vector is derived from a specific calibration dataset and identified through keyword matching to capture non-linear reasoning steps, it inevitably carries noise within the activation space. As a result, the head-specific vector becomes entangled with irrelevant components and can be expressed as

v^{i,j} = v_{\mathrm{reason}}^{i,j} + v_{\mathrm{noise}}^{i,j},where $`v_{\mathrm{reason}}^{i,j}`$ denotes the true non-linear reasoning direction, and $`v_{\mathrm{noise}}^{i,j}`$ represents spurious components. This concern is further supported by recent findings that length-aware activation directions can also be noisy .

To address this, we analyze the covariance structure of the collected activations. Specifically, given a set of activations $`\{ a^{i,j}_{s_k} \}`$, we concatenate activations from all steps into a single matrix: $`A^{i,j} = \bigl[ a^{i,j}_{s_k} \bigr] \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times N}.`$ We compute the empirical covariance matrix and perform its eigen-decomposition as follows:

\begin{equation}

\Sigma^{i,j}

\;=\;

\frac{1}{N}\sum_{k=1}^{N}

\bigl(A^{i,j}_k - \bar{A}^{i,j}\bigr)\bigl(A^{i,j}_k - \bar{A}^{i,j}\bigr)^{\top};

\Sigma^{i,j} \;=\; Q^{i,j}\Lambda^{i,j}\bigl(Q^{i,j}\bigr)^{\top}

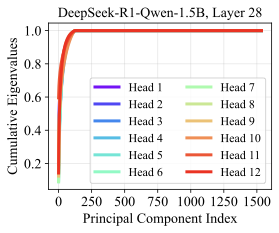

\end{equation}where $`\bar{A}^{i,j}`$ is the average activation across $`N`$ samples. We then visualize the distribution of cumulative eigenvalues, as shown in Figure [fig:pca].

We observe that the signal-to-noise ratio of the raw head vector is low, with the critical information concentrated in a low-rank subspace. To remove such redundancy, we perform a low-rank projection to constrain the head vector into an informative subspace. However, if each head is assigned its own subspace, the resulting representations may lose comparability across heads, as the shared space is replaced by distinct, head-specific subspaces. Therefore, we adopt a shared subspace to filter out the noise components of head vectors. Instead of computing the head-specific covariance matrix $`\Sigma^{i,j}`$, we aggregate the activations of all heads within a layer, $`A^{j} = \Bigl[\sum_{i=1}^{N_h} a^{i,j}_{s_k}\Bigr] \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times N}`$, where $`N_h`$ is the number of heads in layer $`j`$ and $`N`$ is the number of samples. We then compute the eigenspace $`Q^{j}`$ from the covariance of $`A^{j}`$, and project each head vector $`v^{i,j}`$ onto the top-$`n`$ eigenvectors to obtain the aligned representation:

\hat{v}^{i,j} \;=\; Q^{j}[:,:n] \, {Q^{j}[:,:n]}^{\top} v^{i,j}Test-time Steering

During decoding, immediately after each reasoning step, we rotate the representation of the last token to enforce orthogonality with the pre-computed steering direction, while preserving the original activation magnitude:

\begin{equation}

\hat{x}^{i,j}

= \frac{\lVert x^{i,j} \rVert}{\lVert x^{i,j} - \big((x^{i,j})^{\top} v^{i,j}\big) v^{i,j} \rVert}

\left( x^{i,j} - \big((x^{i,j})^{\top} v^{i,j}\big) v^{i,j} \right),

\label{eq:keyfunc2}

\end{equation}where $`x^{i,j}`$ denotes the original representation and $`v^{i,j}`$ is the steering direction. We use $`\ell_2`$ norm here.

The main motivation behind this design is to eliminate the dependence on hyperparameters. Previous steering methods require tuning the steering strength for each model , which limits their practical applicability due to the need for careful hyperparameter adjustment. In contrast, by preserving the activation norm, we avoid the need for such tuning. Moreover, activation outliers are a well-known issue in LLMs, often leading to highly unstable activation magnitudes . Our norm-preserving strategy mitigates this problem by preventing large norm fluctuations during inference, thereby making the steering process more stable.

Experiments

Implementation Details

Models & Datasets. We conduct experiments on widely used reasoning models of different scales, including DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-1.5B/7B/32B (R1-1.5B/7B/32B) , Qwen3-4B/30B , and GPT-OSS-20B . Evaluation is performed across a diverse set of reasoning benchmarks: MATH500 , LiveCodeBench , AIME (120 problems from the 2022–2025 American Invitational Mathematics Examination), AMC23 , GPQA-D , and Calendar Planning .

Baselines. We compare CREST against training-free methods and

include four competitive baselines from diverse perspectives: (i)

Thought Switching Penalty (TIP) , which suppresses the logits of

specific tokens (e.g., “Alternatively,” “Wait”) to reduce unnecessary

shifts in reasoning trajectories; (ii) SEAL , which performs task

arithmetic in the latent space to down-regulate internal representations

associated with such tokens; (iii) Dynasor , which reduces token cost

by performing early exit based on a consistency criterion during

decoding; and (iv) Soft-Thinking , which enables latent-space

reasoning with an entropy-based early-exit strategy. In addition, we

include the original full model as a baseline (Vanilla).

Hyperparameters. In CREST, the only hyperparameter is the number

of attention heads to steer. To avoid task-specific tuning, we conduct a

preliminary ablation study in

Section [sec:ablation] and fix this setting

for each model across all tasks. During decoding, we use the default

settings: temperature = 0.6, top-p = 0.95, and a maximum generation

length of 32,768 tokens.

Token-Efficient Reasoning with Superior Performance

Superior Performance against Other Baselines. To begin, we

demonstrate that CREST can reduce the token cost while achieving

superior performance. As shown in

Table [tab:math], on R1-1.5B,

CREST consistently improves over the vanilla baseline. For instance,

on AMC23, CREST attains 90.% Pass@1 while lowering the average token

cost from 8951 to 5584, a substantial 37.6% reduction. The trend

persists at larger model scales. With R1-7B, CREST achieves 92.4%

accuracy on MATH500 with only 2661 tokens, representing a 34% cost

reduction compared to vanilla, while exceeding other competitive

baselines such as TIP and Dynasor. Overall, these results highlight

the strength of CREST in jointly optimizing accuracy and efficiency.

Unlike prior baselines, which often trade one for the other,

CREST consistently demonstrates gains across both metrics, validating

its generality.

Consistent Improvements Across Model Sizes and Architectures. As

shown in Table 1, we further evaluate CREST across a

wide range of model sizes, from 1.5B to 32B, and across different

architectures, including Qwen-2, Qwen-3, and GPT-OSS. In each subfigure,

the token reduction ratio is visualized with horizontal arrows, while

the accuracy improvements are indicated by vertical arrows. The results

demonstrate that CREST consistently benefits diverse model families.

In some cases, the token reduction ratio reaches as high as 30.8% (R1-7B

on AIME22-24), while the accuracy improvement peaks at 6.7% (GPT-OSS-20B

on AIME25). These findings provide strong evidence of the generalization

ability of CREST across both model scales and architectures.

width=0.99

| Model | AIME2025 | AIME22–24 | ||||||

| Acc (V→C) | ΔAcc | Tokens (V→C) | ΔToken | Acc (V→C) | ΔAcc | Tokens (V→C) | ΔToken | |

| R1-1.5B | 17.0 → 20.3 | ↑ 3.3% | 15,986 → 12,393 | ↓ 22.5% | 18.0 → 20.2 | ↑ 2.2% | 17,052 → 13,407 | ↓ 21.4% |

| R1-7B | 43.5 → 43.5 | ↑ 0.0% | 12,114 → 8,058 | ↓ 33.4% | 44.0 → 44.0 | ↑ 0.0% | 13,692 → 9,471 | ↓ 30.8% |

| R1-32B | 57.7 → 61.0 | ↑ 3.3% | 12,747 → 10,274 | ↓ 19.4% | 64.0 → 64.0 | ↑ 0.0% | 11,465 → 9,730 | ↓ 15.1% |

| GPT-OSS-20B | 50.0 → 56.7 | ↑ 6.7% | 22,930 → 17,665 | ↓ 22.4% | 60.0 → 62.0 | ↑ 2.0% | 22,207 → 20,455 | ↓ 7.9% |

| Qwen3-30B | 73.30 → 73.33 | ↑ 0.03% | 15,936 → 14,568 | ↓ 8.6% | 78.0 → 78.0 | ↑ 0.0% | 15,292 → 13,973 | ↓ 8.6% |

Strong Generalization Across Diverse Task Domains. We further

evaluate CREST across multiple task domains, including mathematical

reasoning (AIME22–25, comprising all 120 problems from 2022–2025), code

generation (LiveCodeBench), common-sense reasoning (GPQA-D), and

planning (Calendar Planning), as reported in

Table [tab:tasks]. Despite being calibrated

only on MATH500, CREST generalizes effectively to both in-domain and

out-of-domain tasks. Within the math domain, it maintains strong

transfer, achieving 63.% accuracy on AIME22–25 while reducing token cost

from 11,823 to 9,903. Beyond math, CREST delivers consistent

improvements: on LiveCodeBench, accuracy increases from 56.3% to 59.3%

with fewer tokens; on GPQA-D, accuracy rises substantially from 32.3% to

40.9% while tokens drop from 7,600 to 6,627; and on Calendar Planning,

performance improves from 77.1% to 78.7% with notable cost reduction

(3,145 → 2,507). Similar patterns hold for larger architectures like

Qwen3-30B, where CREST boosts LiveCodeBench accuracy from 66.5% to

73.1% while also reducing tokens.

Analysis. The performance gains of CREST can be largely attributed

to the intrinsic redundancy in chain-of-thought reasoning, consistent

with recent findings that LLMs can often achieve competitive or even

superior performance without explicit reasoning when combined with

parallel test-time techniques such as majority voting , and that pruning

or token-budget-aware strategies applied to reasoning traces do not

necessarily harm accuracy . By intervening at the activation level,

CREST effectively mitigates this redundancy, achieving a win–win in

both efficiency and accuracy.

Further Investigation

Ablation Study on the Number of Steered Heads

When implementing CREST, a natural design question concerns the number

of attention heads to steer. To investigate this, we conduct ablation

studies on R1-1.5B and R1-7B on the AIME22-24 task.

Overall, we find that steering approximately the top 38% of attention heads delivers the strongest performance, balancing both accuracy and token reduction. Figure 3 illustrates the ablation study on the number of attention heads used for intervention. In this analysis, we rank heads by linear probing accuracy and evaluate the top subsets on the AIME22-24 benchmark. The results indicate that steering 38% of all attention heads provides the best balance, yielding improvements in both accuracy and token efficiency.

style="width:100.0%" />

style="width:100.0%" />

Moreover, we observe that the proportion of steerable heads is relatively stable across different models: both R1-1.5B and R1-7B achieve their best performance at similar attention head ratios. This consistency further confirms the robustness of our approach and highlights its ease of hyperparameter tuning. Consequently, we adopt this ‘gold ratio’ as the default setting in our experiments, thereby avoiding task-specific tuning that could risk information leakage from the test set.

style="width:100.0%" />

style="width:100.0%" />

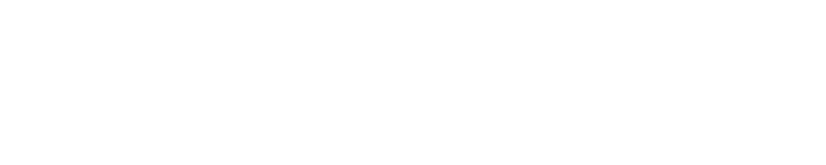

Response Length Distribution

In Section [sec:performance], we primarily

compared different methods based on the average token cost across the

full test set. To gain deeper insights into efficiency improvements, we

further analyze the distribution of response lengths.

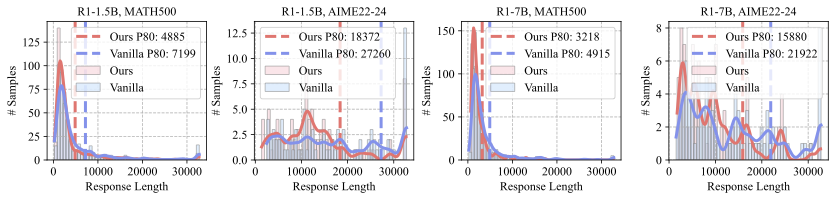

Figure 4 presents histograms comparing our

method with vanilla inference. Each subfigure shows both the

distribution and the token cost for the top 8% of samples. The results

reveal that CREST shifts the distribution leftward, highlighting more

pronounced token reductions in terms of both the average and the top-8%

subset.

We also observe that, under both CREST and vanilla inference, a small

number of failure cases reach the maximum generation limit of 32k

tokens. Upon closer inspection, these failures typically involve

repetitive outputs. This suggests that CREST could be further enhanced

by incorporating early-exit strategies to mitigate repetition. We will

explore in the future work.

Conclusion

In this paper, we investigate one of the core capabilities of large

language models: reasoning. We conduct a series of empirical studies to

better understand the reasoning processes of LLMs and categorize

extended chain-of-thought reasoning into two types: linear, step-by-step

reasoning and cognitive-style non-linear reasoning. Our findings reveal

that certain attention heads are correlated with non-linear cognitive

reasoning patterns and can be influenced through activation

intervention. Based on these insights, we propose CREST, a

training-free approach for steering the reasoning trajectory at test

time. Through extensive experiments, we demonstrate that

CREST improves both reasoning accuracy and inference efficiency

without requiring additional training. Moreover, our method is broadly

compatible with a wide range of pre-trained LLMs, highlighting its

practical potential for enhancing reasoning models in real-world

applications.

Extended Related Works

We organized prior research into three key categories and, to the best of our ability, emphasize the most recent contributions from the extensive body of work.

Reasoning Models. Early work on chain‑of‑thought (CoT) prompting and self‑consistency decoding showed that sampling diverse reasoning paths at inference time and selecting the most frequent answer markedly improves accuracy. Structured search frameworks subsequently generalise this idea: Tree‑of‑Thought performs look‑ahead search over branching “thought” sequences ; Graph‑of‑Thought re‑uses sub‑derivations through a non‑linear dependency graph ; and Forest‑of‑Thought scales to many sparsely activated trees under larger compute budgets . Since then, the field of reasoning language models has advanced rapidly, driven in large part by innovations in test‑time thinking strategies . Closed‑source providers now offer dedicated “thinking” variants such as OpenAI’s o‑series , Anthropic’s Claude‑3.7‑Sonnet‑Thinking , and Google’s Gemini‑2.5‑Flash . The open‑source community has kept pace with competitive models including DeepSeek‑R1 , Qwen2.5 , QWQ , Phi‑4‑Reasoning , and, most recently, Qwen3 , alongside emerging contenders such as R‑Star , Kimi‑1.5 , Sky , and RedStar . These open-weight models enable in-depth analysis of their underlying reasoning mechanisms, offering a unique opportunity to “unblack-box” their cognitive processes. In this work, we explore how manipulating internal components, such as attention heads and hidden states, can influence the model’s reasoning behavior.

Cognitive Behaviors in LLMs. In , a cognitive behavior is defined as any readily identifiable pattern in a model’s chain‑of‑thought—such as verification (double‑checking work), backtracking (abandoning an unfruitful path), sub‑goal setting (planning intermediate steps), or backward chaining (reasoning from goal to premises)—that appears in the text trace and statistically correlates with higher task accuracy or more sample‑efficient learning. These behaviors mirror classic findings in human problem solving: means–ends sub‑goal analysis , analogical transfer , and metacognitive error monitoring . Modern LLM methods explicitly instate the same heuristics—for example, chain‑of‑thought prompting makes the reasoning trace visible, while self‑consistency sampling and Tree‑of‑Thought search operationalize backtracking and sub‑goal exploration. By situating LLM “cognitive behaviors” within this well‑studied human framework, we both ground the terminology and reveal gaps where LLMs still diverges from human cognition, motivating a surge of techniques aimed at “teaching” models to think like human.

Methods to Improve Test-Time Reasoning Models. Rather than

modifying training regimes—e.g. self-fine-tuning or RL curricula such

as Absolute Zero —we review approaches that act only at inference.

Adapting (and extending) the taxonomy of , we distinguish four lines of

work and situate our own method, CREST, within the emerging fourth

category.

-

Light-weight tuning. Small, targeted weight or prompt updates steer models toward brevity without costly retraining. RL with explicit length penalties (Concise RL) and O1-Pruner shorten chains-of-thought (CoT) while preserving accuracy . Model-side tweaks such as ThinkEdit and an elastic CoT “knob’’ expose conciseness or length on demand . Together these studies reveal an inverted-U length–accuracy curve that motivates our desire to steer (rather than merely shorten) reasoning traces.

-

Adaptive compute control. The model spends tokens only when they help. Token-Budget-Aware Reasoning predicts a per-question budget ; confidence-based Fast–Slow Thinking routes easy instances through a cheap path ; early-exit policies such as DEE, S-GRPO, and self-adaptive CoT learning halt generation when marginal utility drops . Our results show that

CRESTcan combine with these token-savers, further reducing budget without extra training. -

Direct trace manipulation. These methods edit or reuse the textual CoT itself. SPGR keeps only perplexity-critical steps ; Chain-of-Draft compresses full traces to terse “draft’’ thoughts at $`\sim`$8 % of the tokens ; confidence-weighted self-consistency and WiSE-FT ensemble weights cut the number of sampled paths or models needed for robust answers . While these techniques operate in token space, ours intervenes inside the network, offering an orthogonal lever that can coexist with draft-style pruning.

-

Representation-level activation editing. A newer strand steers generation by editing hidden activations rather than weights or outputs. Early examples include Activation Addition (ActAdd) and Representation Engineering , which inject global steering vectors into the residual stream; PSA adds differential-privacy guarantees to the same idea .

CREST advances representation-level activation editing by

discovering cognitive attention heads aligning with concrete reasoning

behaviors and showing that head-specific interventions outperform

global vectors. Beyond performance, our cognitive-head analysis provides

new interpretability evidence that bridges recent attention-head

studies with activation-editing control.

More Implementation Details

Keyword List for Categorizing Reasoning Steps

To categorize thinking steps into linear and non-linear reasoning types, we adopt a keyword-matching strategy. Specifically, if a step contains any keyword $`s \in \mathcal{S}`$, it is classified as a non-linear reasoning step; otherwise, it is considered a linear reasoning step. The keyword set $`\mathcal{S}`$ includes:{Wait, Alternatively, Let me verify, another solution, Let me make sure, hold on, think again, think differenly, another approach, another method}.

Training Details for Linear Probing

To optimize the linear probe, we first randomly sample 1,000 features from both linear and non-linear thought steps to mitigate class imbalance, as linear steps significantly outnumber non-linear ones. The dataset is then randomly split into training, validation, and test sets with a ratio of $`8:1:1`$. We train the linear probe using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of $`1 \times 10^{-3}`$, which is decayed following a cosine annealing schedule. The final checkpoint is selected based on the highest validation accuracy.

More Experiment Results

Probing Accuracy of Reasoning Representations

/>

/>

/>

/>

/>

/>

/>

/>

/>

/>

We report the probing results of different models in Figure 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 where we can observe that certain attention heads exhibit higher accuracy, i.e., cognitive heads.

style="width:70.0%" />

style="width:70.0%" />

More Results of Activation Intervention

We present additional examples in Figure 10, illustrating the reasoning process when the non-linear reasoning component is either enhanced or reduced. Specifically, enhancing non-linear reasoning leads the model to generate longer reasoning chains (e.g., 84 steps), while reducing it results in shorter chains (e.g., 29 steps), compared to the original 31-step output.

Clarification of LLM Usage

In this work, large language models are employed to refine the writing and to aid in generating code for figure plotting. All generated outputs are thoroughly validated by the authors prior to use.

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)