DynaFix Iterative Automated Program Repair Driven by Execution-Level Dynamic Information

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: DynaFix Iterative Automated Program Repair Driven by Execution-Level Dynamic Information- ArXiv ID: 2512.24635

- Date: 2025-12-31

- Authors: Zhili Huang, Ling Xu, Chao Liu, Weifeng Sun, Xu Zhang, Yan Lei, Meng Yan, Hongyu Zhang

📝 Abstract

Automated Program Repair (APR) aims to automatically generate correct patches for buggy programs. Recent approaches leveraging large language models (LLMs) have shown promise but face limitations. Most rely solely on static analysis, ignoring runtime behaviors. Some attempt to incorporate dynamic signals, but these are often restricted to training or fine-tuning, or injected only once into the repair prompt, without iterative use. This fails to fully capture program execution. Current iterative repair frameworks typically rely on coarse-grained feedback, such as pass/fail results or exception types, and do not leverage fine-grained execution-level information effectively. As a result, models struggle to simulate human stepwise debugging, limiting their effectiveness in multi-step reasoning and complex bug repair. To address these challenges, we propose DynaFix, an execution-level dynamic information-driven APR method that iteratively leverages runtime information to refine the repair process. In each repair round, DynaFix captures execution-level dynamic information such as variable states, control-flow paths, and call stacks, transforming them into structured prompts to guide LLMs in generating candidate patches. If a patch fails validation, DynaFix re-executes the modified program to collect new execution information for the next attempt. This iterative loop incrementally improves patches based on updated feedback, similar to the stepwise debugging practices of human developers. We evaluate DynaFix on the Defects4J v1.2 and v2.0 benchmarks. DynaFix repairs 186 single-function bugs, a 10% improvement over state-of-the-art baselines, including 38 bugs previously unrepaired. It achieves correct patches within at most 35 attempts, reducing the patch search space by 70% compared with existing methods, thereby demonstrating both effectiveness and efficiency in repairing complex bugs.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **Execution-Level Dynamic Information**: DynaFix uses the actual runtime behavior of a program to understand and fix bugs more effectively than traditional static code analysis. 2. **Iterative Repair Strategy**: By collecting execution traces iteratively, DynaFix refines patch generation with each attempt, much like how developers debug in real-life scenarios. 3. **ByteTrace Tool**: ByteTrace is a non-intrusive bytecode instrumentation tool that captures detailed runtime information such as variable states and control flow.Simplified Explanation: DynaFix automates the process of fixing software bugs by analyzing how programs actually run, providing more insights than just looking at static code.

Intermediate Explanation: Using LLMs, DynaFix iteratively collects runtime data through ByteTrace to generate and refine patches for software bugs, enhancing debugging efficiency.

Advanced Explanation: DynaFix leverages Large Language Models with ByteTrace’s detailed execution-level dynamic information collection to improve automated patch generation. This method captures nuanced program behaviors, enabling more accurate bug fixes than traditional static analysis methods.

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

Software systems underpin virtually every critical domain of modern society, such as manufacturing, aerospace, energy, and healthcare. As these systems grow in scale and complexity, they inevitably introduce a large number of bugs. Program repair is essential for maintaining stability and security throughout the software lifecycle. Prior studies show that developers spend 35%–50% of their time fixing bugs manually . To reduce this cost, researchers have extensively investigated APR techniques, which aim to automatically generate patches that automatically correct faulty code .

Traditional APR approaches can be broadly categorized into heuristic-based , constraint-based , and template-based methods . Heuristic methods search a large patch space but often suffer from efficiency degradation as the space expands. Constraint-based methods provide formal guarantees but struggle to scale to complex programs. Template-based methods, which are widely regarded as the most representative , depend on high-quality templates that are costly to construct and limit general applicability. To address these limitations, deep learning–based APR methods have emerged, typically formulating patch generation as a neural machine translation (NMT) task , trained on large corpora of bug–fix pairs . However, their effectiveness heavily relies on training data quality and drops significantly when encountering previously unseen bug types .

The rapid progress of LLMs has opened new opportunities for APR . Recent approaches adopt an iterative paradigm, where the LLM is guided by feedback from previous repair attempts. Beyond this, several studies have further explored incorporating dynamic execution information, leveraging runtime traces or behavioral signals to improve fault localization and patch generation . Although these methods achieve state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance on benchmarks, they still face two key challenges:

-

Over-reliance on static information and insufficient use of dynamic information. Despite the strong capabilities of LLMs in code generation and modification, their effectiveness in APR remains limited because they rely predominantly on static code artifacts (e.g., exception messages, test outcomes, or code comments), which provide only partial insight into the actual execution that causes failures. Recent studies showed that dynamic information (i.e., execution traces) can help LLMs understand runtime behaviors and support patch generation for complex software bugs. However, the use of dynamic information in existing work remains limited—most methods either restrict it to the training or fine-tuning phase , or inject it only once into the repair prompt , without leveraging it iteratively throughout the repair process. Because execution traces are only superficially or sporadically exploited, models cannot fully capture program behaviors or identify underlying causes in complex or multi-step bugs. This insufficient and non-iterative use of dynamic information, in turn, constrains their ability to localize faults and generate effective patches accurately.

-

Coarse-grained feedback in iterative repair without execution-level insights. The SOTA LLM-based APR approaches employ iterative repair strategies , where the model is repeatedly re-prompted by feedback from test results or bug reports after each repair attempt. However, such feedback is typically coarse-grained, often limited to the result level (e.g., pass/fail outcomes, exception types, or aggregated bug summaries). By contrast, effective real-world debugging depends on the fine-grained examination of runtime behaviors, including variable states, control-flow paths, and call stacks, to refine hypotheses and iteratively isolate the fault. The absence of execution-level insights constrains existing iterative methods, limiting their ability to handle complex bugs that require multi-step reasoning and progressive repair.

To address these limitations, we propose DynaFix, an LLM-based APR method that integrates execution-level dynamic information feedback into an iterative repair workflow. The key insight is that execution traces, which includes variable states, control-flow paths, and call stacks, provide essential behavioral evidence for understanding program faults and uncovering their root causes. To collect this information, we develop ByteTrace, a non-intrusive tool for collecting program execution traces, which collects precise and context-rich dynamic information to support DynaFix.

In each repair iteration, DynaFix executes the buggy program, records its execution traces via ByteTrace, and augments the repair prompt with the captured dynamic information. The LLM then generates candidate patches. If a patch fails validation, DynaFix re-executes the program, collects updated execution traces, and refines for the next iteration. This closed-loop process continuously grounds the LLM’s reasoning in the latest runtime behaviors, resembling how human developers iteratively debug with feedback. By sustaining iterative and fine-grained exploitation of dynamic information, DynaFix enables more accurate fault localization and more effective patch generation.

We conducted a comprehensive evaluation of DynaFix on the widely used Defects4J benchmark. On the 483 single-function bugs in Defects4J v2.0, DynaFix successfully repaired 186 bugs, comprising 100 from v1.2 and 86 from v2.0, and resolved 38 bugs that were not fixed by any of the selected baselines. Compared with LLM-based methods that rely solely on exception message prompts, DynaFix repaired 116 more single-function bugs and 13 more multi-function bugs, corresponding to improvements of 24.0% and 3.7% in repair rates, respectively.

Our contributions are summarized as follows:

-

We propose DynaFix, an LLM-based APR framework that integrates execution-level dynamic information into the repair process. By leveraging fine-grained runtime signals, DynaFix guides code modifications in an iterative manner that more closely aligns with how developers debug real programs.

-

We developed ByteTrace, a lightweight Java instrumentation tool for capturing detailed execution traces, enabling iterative repair based on execution-level feedback.

-

Extensive experiments on the Defects4J benchmark demonstrate that DynaFix outperforms 11 SOTA methods and successfully repairs 38 bugs that previous methods could not fix. To promote reproducibility, we will release a replication package including the DynaFix framework, the ByteTrace tool, and all experimental datasets upon acceptance.

Motivation

This section presents two real-world examples to illustrate the limitations of current APR approaches and highlight the necessity of incorporating execution-level dynamic information into the repair process. In the code listings, lines prefixed with “+” denote added code, while those with “–” indicate deleted code.

+ if (this.allowDuplicateXValues) {

+ add(x, y);

+ return null;

+ }

XYDataItem overwritten = null;

int index = indexOf(x);

+ if (index >= 0) {

- if (index >= 0 && !this.allowDuplicateXValues) {

Listing [lst:chart5-patch] shows the

developer patch for the Chart-5 vulnerability in Defects4J . Here, the

condition this.allowDuplicateXValues has been removed from the generic

condition block and refined as a new conditional statement. The failure

reported by JUnit was , indicating an array boundary violation but

lacking sufficient contextual information to localize the fault. For

LLM-based APR methods, this ambiguity expands the search space for

possible patches. Without access to runtime values of variables such as

x, y, or the return result value of the indexOf, it becomes

difficult for the model to determine whether the fault stems from a

missing null check, an incorrect index calculation, or inconsistent

data.

for (int i = getNumObjectiveFunctions(); i < getHeight(); i++) {

- if (MathUtils.equals(getEntry(i, col), 1.0, epsilon) && (row == null)) {

+ if (!MathUtils.equals(getEntry(i, col), 0.0, epsilon)) {

+ if (row == null) {

row = i;

- } else if (!MathUtils.equals(getEntry(i, col), 0.0, epsilon)) {

Listing [lst:math87-patch] presents the

developer patch for the Math-87 bug. The target function identifies

whether a matrix column is a unit vector and returns the row index

containing the value 1.0. Although the static code appears correct,

JUnit reports the exception

junit.framework.AssertionFailedError: expected:<10.0> but was:<0.0>.

Based solely on this message and static code, LLM-based APR systems

often misdiagnose the fault. Providing the actual col input at runtime

reveals that getEntry(i, col) returns a value close to but not exactly

1.0 due to floating-point precision errors. This small deviation leads

to the function returning an incorrect row index.

/>

/>

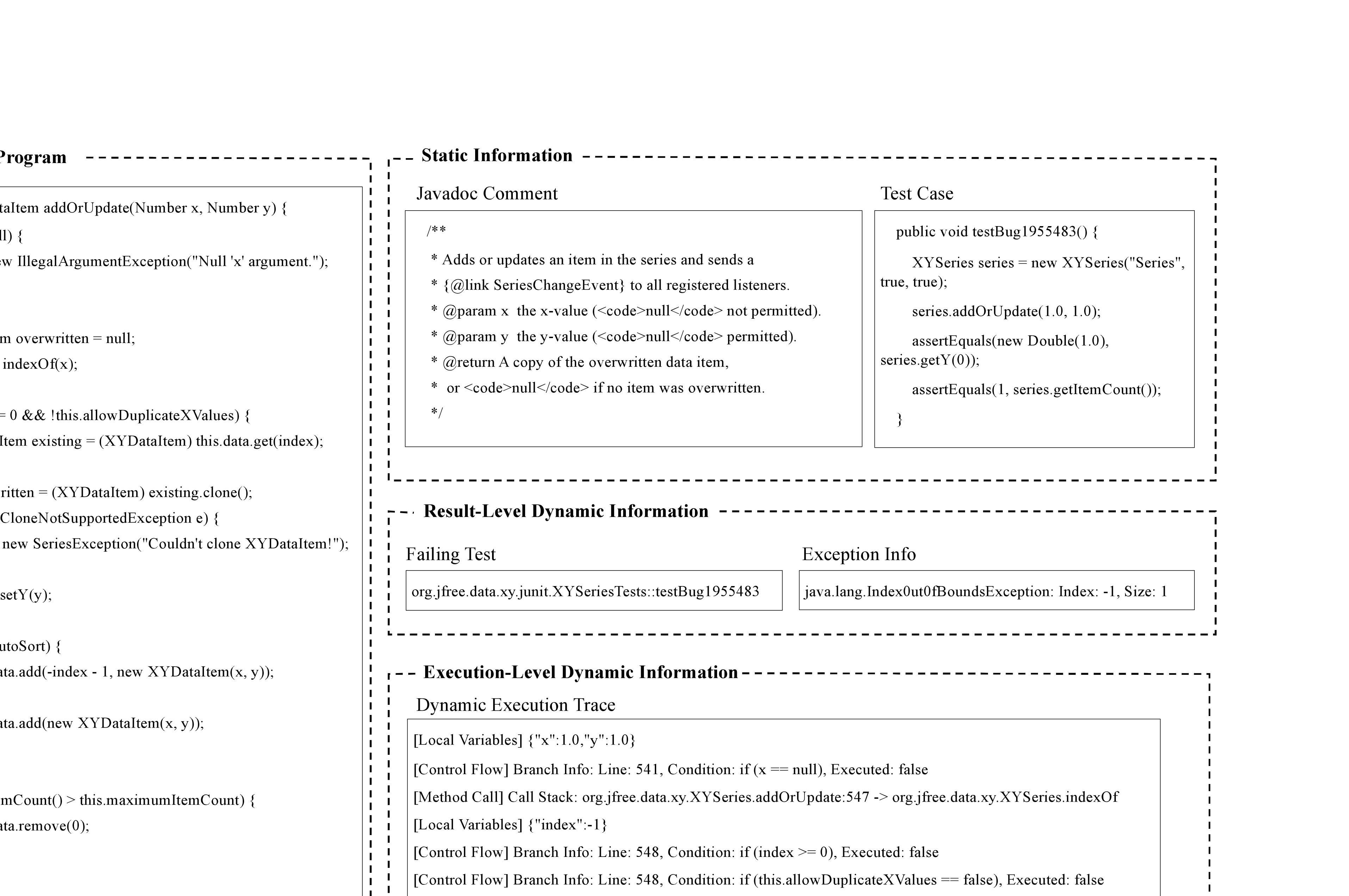

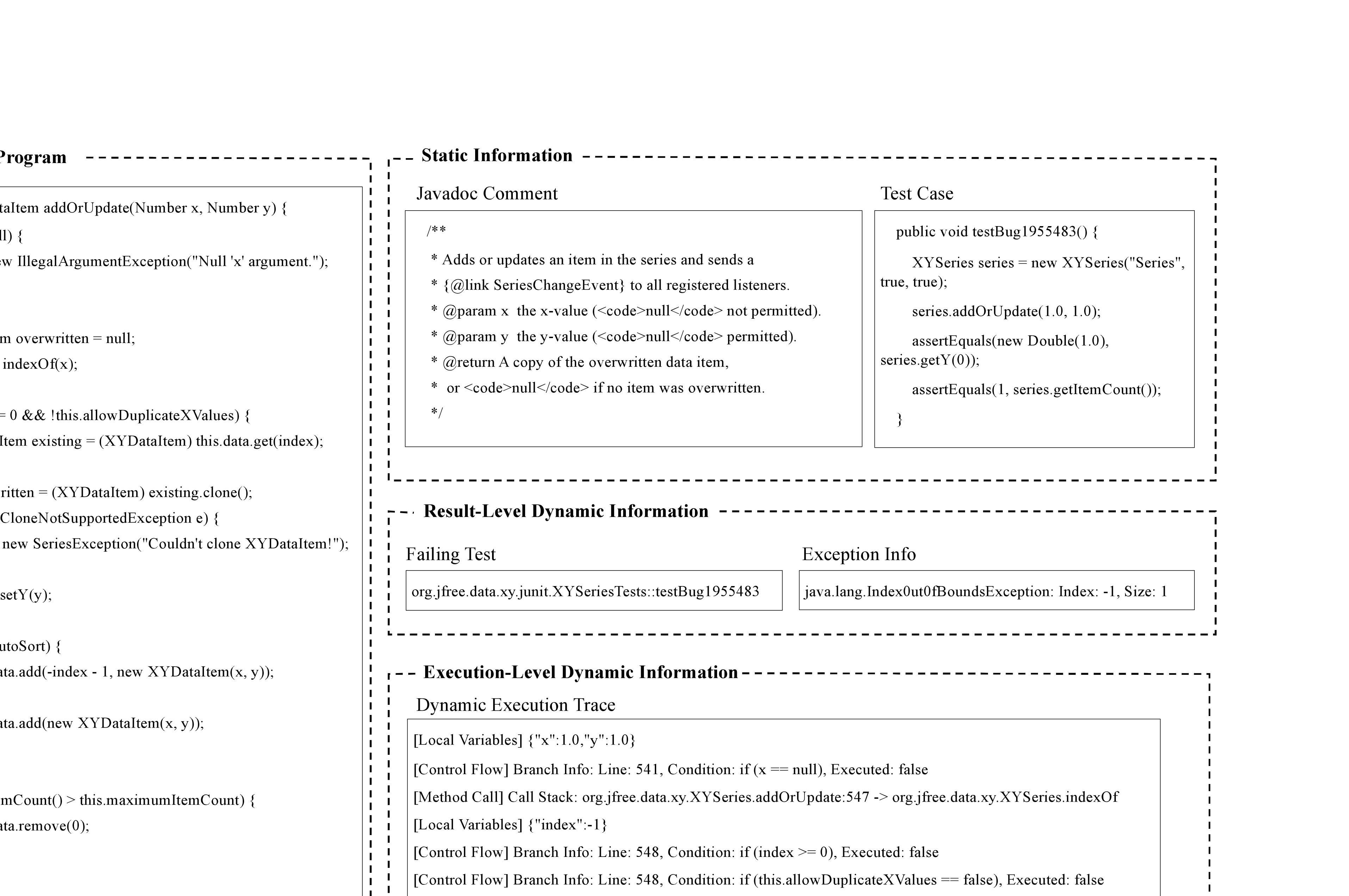

The above examples highlight key challenges faced by current LLM-based APR techniques in effectively leveraging information during repair. As illustrated in Fig. 1, most existing approaches primarily depend on static information such as buggy source code, code comments, and test cases. Others incorporate dynamic signals, but these are typically limited to coarse result-level feedback such as pass/fail test outcomes or exception information. While such signals can confirm the occurrence of a failure, they provide little insight into the underlying execution state, making it difficult for models to accurately localize faults. Recent studies have begun to explore finer-grained execution-level dynamic information(e.g., variable states, control-flow) . However, most of these methods exploit such data during training or inject it once into a repair prompt, leaving its potential for iterative repair largely untapped.

Moreover, existing methods lack a systematic feedback mechanism that continuously incorporates execution-level dynamic information throughout the repair loop. Approaches that rely primarily on static information, such as those in generate patches in a single step and cannot refine a patch once it fails, while iterative approaches using result-level signals are constrained to high-level feedback (e.g., pass/fail or exception type) that fails to convey deeper execution behaviors. Without stepwise use of fine-grained execution-level feedback, these approaches often resemble a trial-and-error process rather than converging through developer-like reasoning guided by execution information, ultimately limiting their effectiveness in addressing complex bugs.

Approach

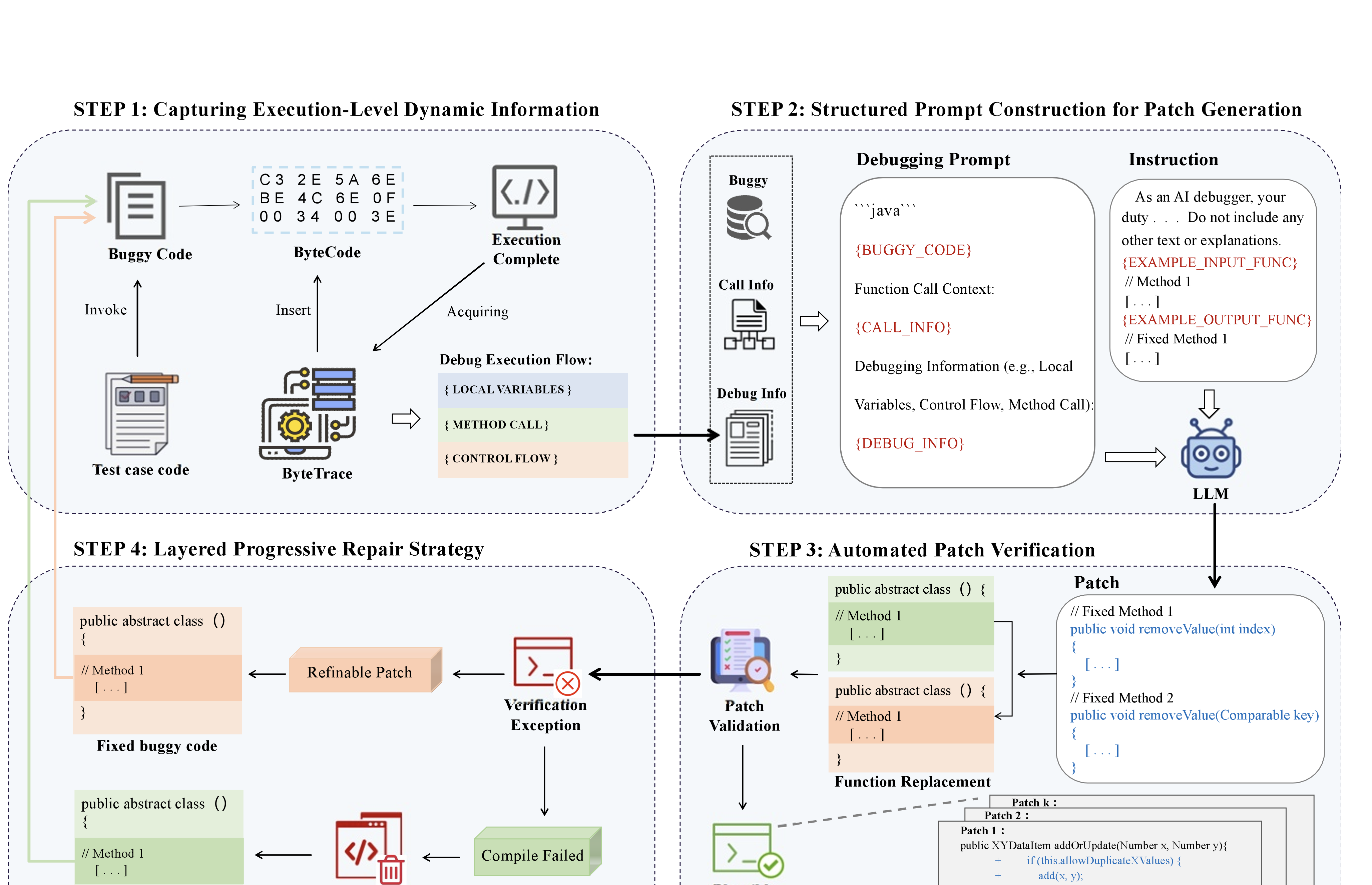

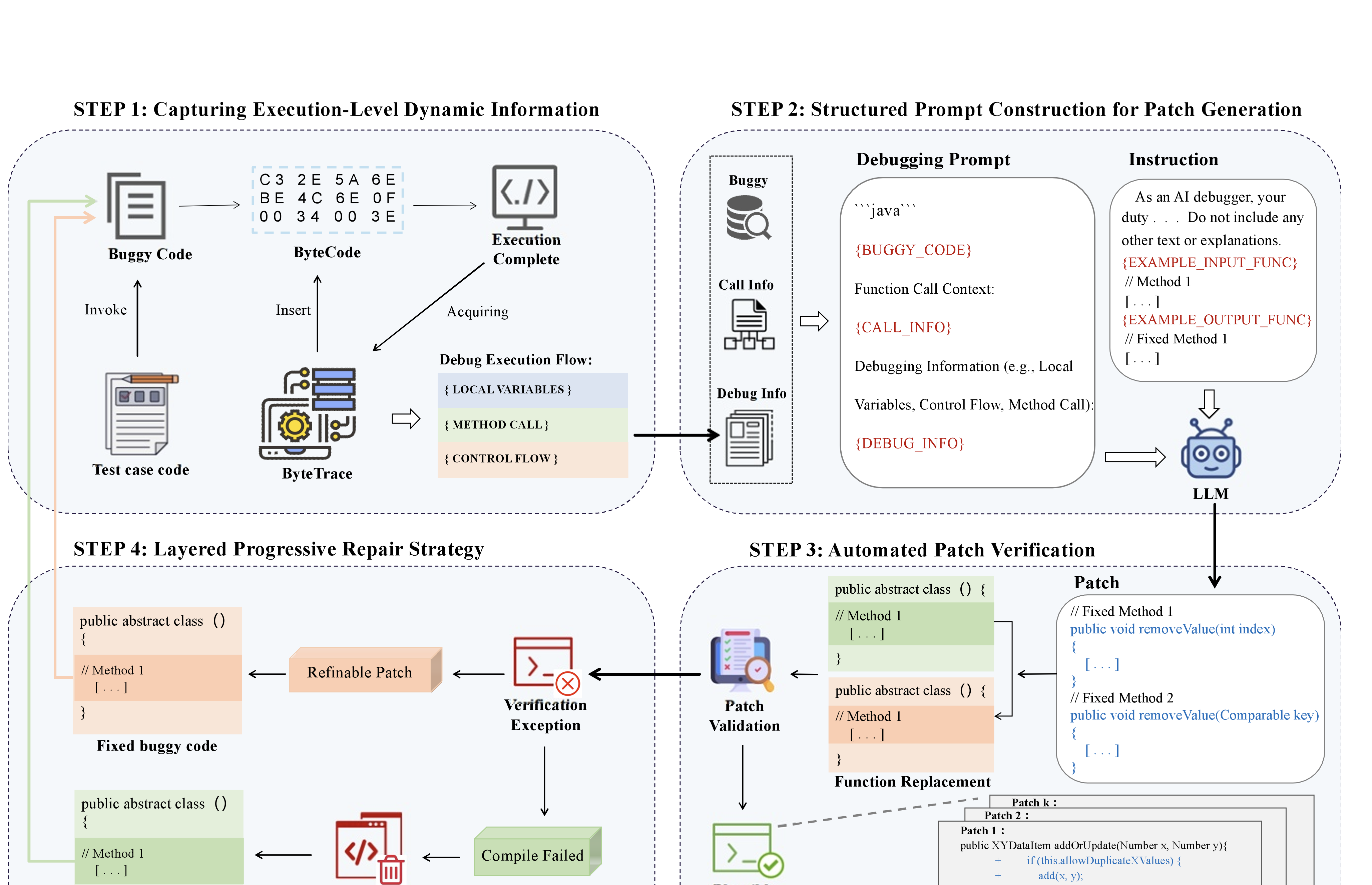

Figure 2 illustrates the framework of our proposed approach. We introduce DynaFix, an iterative APR approach driven by execution-level dynamic information. First, In terms of information granularity, DynaFix addresses the limitations of JUnit’s coarse exception reporting by integrating non-intrusive bytecode instrumentation into the repair process. Instead of modifying source code directly, our framework instruments bytecode to capture dynamic behavioral information during program execution without interfering with normal operation. This runtime data is then fed back to the LLM, providing richer context on bug behavior and enabling more informed repair decisions. Second, regarding the repair process, we design a Layered Progressive Repair (LPR) strategy, which prioritizes promising patches and discards unpromising ones at an early stage. This targeted strategy improves efficiency by focusing computational resources on promising candidates.

The workflow consists of four main steps:

-

Step 1 (Section 3.1): We employ ByteTrace, a tool developed in this study, to perform non-intrusive bytecode instrumentation on the buggy program. During test execution, ByteTrace captures dynamic runtime information, including variable states, control-flow paths, and call stacks.

-

Step 2 (Section 3.2): The collected debugging information is combined with the original buggy source code to construct debugging prompts, thereby supplying the LLM with execution context for the bug. These prompts help the LLM better understand bug behavior and generate candidate patches. To further guide patch generation, we incorporate instruction prompts, including role definitions and one-shot examples, ensuring that the LLM outputs code in the expected format.

-

Step 3 (Section 3.3): The candidate patch generated by the LLM is applied to the source code and validated by running test cases. This automated validation ensures that patch correctness is assessed automatically.

-

Step 4 (Section 3.4): We apply the LPR strategy to iteratively refine patches based on validation results. When a patch fails validation, two cases are distinguished:

-

(a) Compilation Error: The patch is discarded, and the repair process restarts using the debugging information collected from the original buggy code.

-

(b) Test Failure: If the patch compiles but fails in test execution, it is treated as a refinable patch with potential for further improvement. Updated debugging information, is collected based on the current buggy code, and used to guide the next repair iteration.

-

/>

/>

Capturing Execution-Level Dynamic Information

A core feature of DynaFix is its ability to exploit execution-level dynamic information as iterative feedback. To capture such information from buggy programs at runtime, we integrate a non-intrusive bytecode instrumentation mechanism into the framework. This mechanism records dynamic behaviors such as local variables, method call traces, and control flow during program execution with test cases. By instrumenting bytecode rather than directly modifying source code, our approach captures rich execution-level dynamic information without disrupting normal program execution. Moreover, the modular instrumentation design facilitates scalability and allows automatic adaptation to benchmarks such as Defects4J.

Specifically, we extended and integrated the DebugRecorder tool from DEVLoRE . The original DebugRecorder only leverages JavaAgent and ASM to instrument Java programs and monitor local variable values. Building on this foundation, we developed ByteTrace, a bytecode instrumentation tool that serves as the core data collection component of our APR framework. Compared with DebugRecorder, ByteTrace adds support for tracing method call stacks and conditional control flow, thereby providing a more comprehensive execution context for program repair. Furthermore, ByteTrace modularizes the instrumentation logic, enabling automatic adaptation to the Defects4J benchmark and enabling efficient collection of execution-level dynamic data in large-scale APR experiments.

For information granularity selection, we adopt function-level instrumentation. Prior studies show that function-level granularity provides sufficient context for fault localization and repair while avoiding the fragmentation problems in statement-level or variable-level tracing. This design also aligns with the input-output paradigm of LLMs, which are typically trained to process and generate code at the function level. Therefore, DynaFix employs function-level instrumentation to balance repair effectiveness with scalability in LLM-based workflows. please say that which experimental result approves the balance.

Structured Prompt Construction for Patch Generation

/>

/>

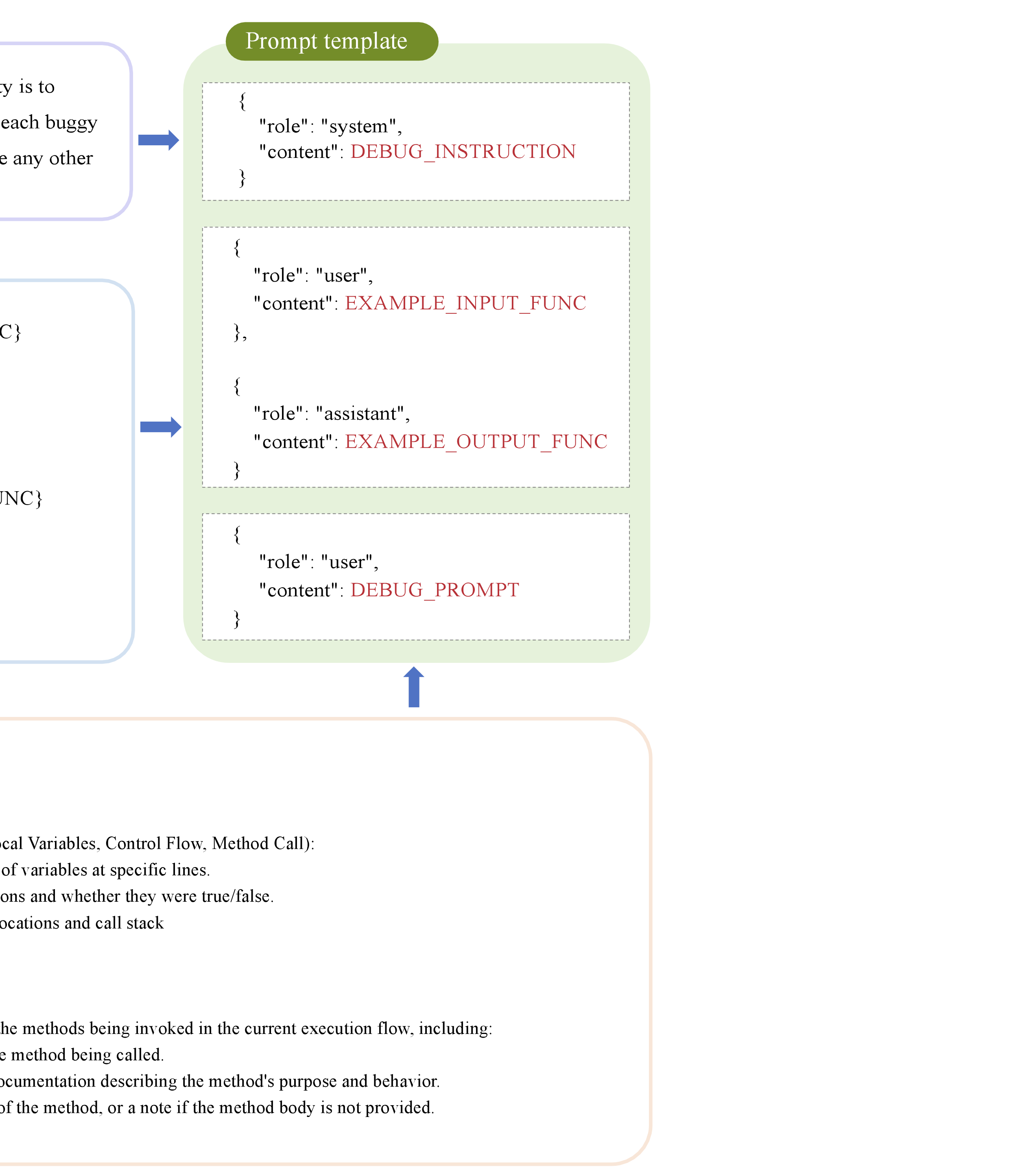

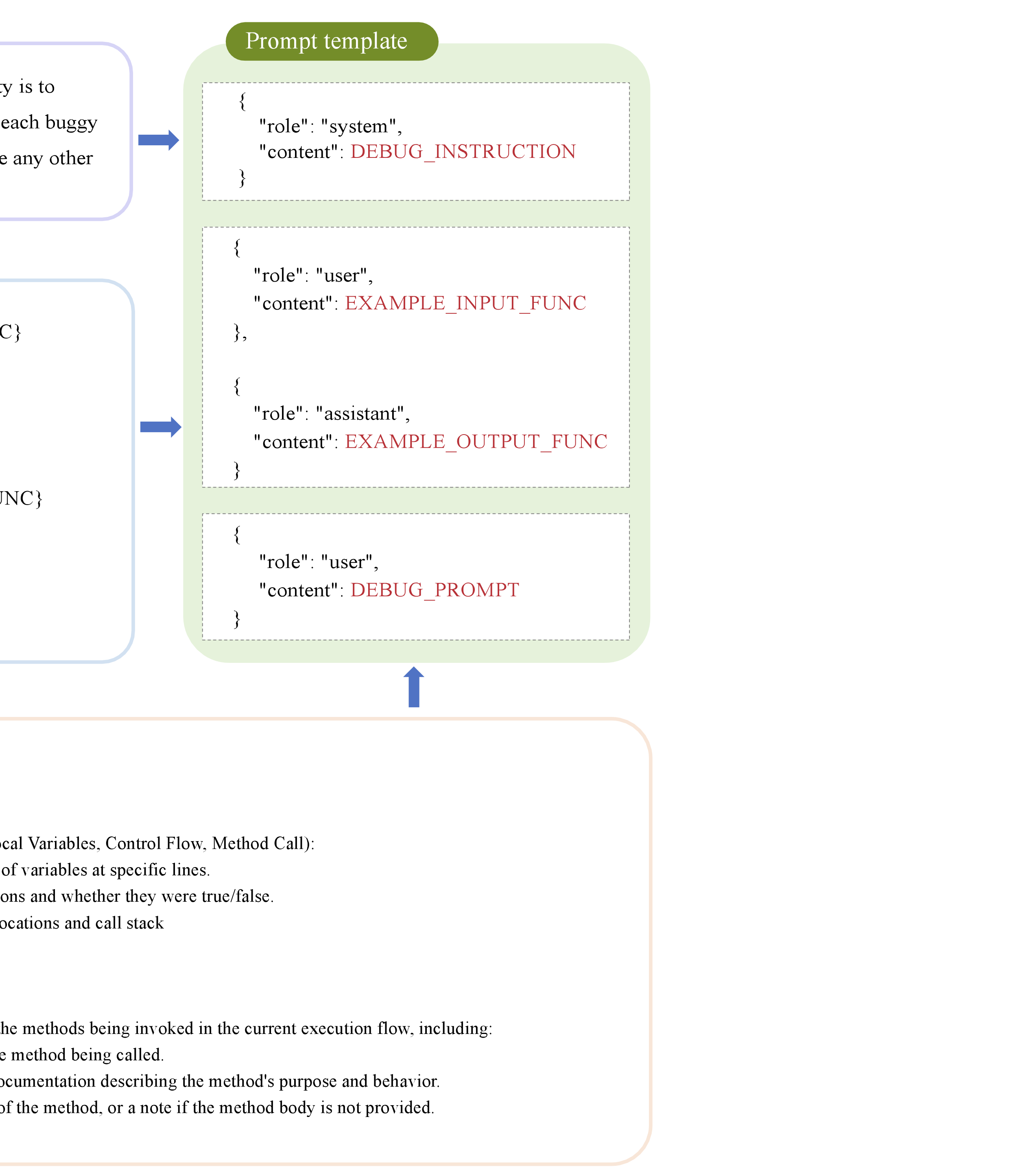

For LLM-based APR, the design of a well-structured and semantically clear prompt is critical to repair performance . Even with comprehensive bug-related information, poorly designed prompts can limit model understanding and result in suboptimal patches. To achieve efficient and accurate information transmission, we designed a hierarchical prompt template, as shown in Figure 3, consisting of three parts: system instructions, input-output example, and debugging information.

The instruction explicitly defines the LLM’s role as an AI debugger,

requiring it to generate corrected versions of buggy functions without

producing any explanatory text. This enforces role awareness and output

format constraints. The template then provides a representative one-shot

example, inspired by recent findings that including one or two examples

significantly improves code generation performance compared to zero-shot

prompting. In this example, the input consists of a buggy function with

handcrafted debugging information, and the output presents the fully

repaired function. The repaired function is marked a consistent

identifier, such as // Fixed Method X, to enable deterministic patch

extraction.

Finally, we inject debugging information collected by ByteTrace. This includes: (1) the buggy function as the repair target; (2) dynamic execution traces such as variable states, control-flow paths, and call stacks, accompanied by short in-prompt explanations to aid model understanding; and (3) call context, including function names, signatures, and callees code, retrieved from the codebase via dynamic call relationships.

This structured prompt design enables the LLM to clearly identify the repair task, interpret execution-level dynamic information, and reason about call dependencies. As a result, the model is guided to generate a targeted and verifiable patch in the expected format.

Automated Patch validation

To evaluate the correctness of the patch, DynaFix replaces the faulty function in the original program with the generated fix. It then executes the corresponding test suite to ensure successful compilation and test passing. While passing all tests suggests plausible correctness, prior work has shown that benchmark test suites often suffer from limited coverage, allowing incorrect patches to be misclassified as correct . To address this issue, following standard practices in the APR community , we further conduct manual inspection of test-passing patches to assess whether they are semantically equivalent to the developer’s fix. This two-stage process is used to verify that the reported patches are both test-adequate and semantically valid.

Layered Progressive Repair Strategy

Due to the high computational cost and token-based billing model of mainstream LLM services, large-scale and multi-round invocations of models during APR can lead to significant resource consumption and economic overhead. To address this, we introduce the LPR strategy, which incrementally explores the patch space in both breadth and depth. In the breadth phase, it rapidly evaluates candidate patches, discarding invalid ones to save resources. Refinable patches that pass partial tests then enter the depth phase, where execution-level dynamic information guides step-by-step refinement. This design focuses resources on viable repair directions and is intended to balance repair effectiveness with computational resource consumption. We provide empirical evidence of its efficiency in Section 5.3.

As described in Algorithm [alg:lpr], LPR takes as input a set of buggy programs $`\mathcal{B}`$ with as input a set of buggy programs diagnostic information and outputs either a successfully repaired program or a failure report. For each bug, the system first initiates breadth-based layered repair, generating an initial candidate patch $`p_0`$ using the LLM. If $`p_0`$ fails to compile or results in runtime exceptions, it is immediately discarded to avoid wasting resources on invalid repair directions. If $`p_0`$ passes all test cases, the bug is considered successfully repaired, and the process terminates. All generated patches, including those that fail validation, are stored along with their function code and validation results. In subsequent rounds, the LLM is prompted to generate new patches that differ from those in the patch history, thereby encouraging diversity in candidate fixes. This first phase aims to explore a broad range of potential repair directions quickly.

If the patches generated during a breadth-based search fail to fully repair the program but pass a subset of test cases, they are deemed potentially promising. The system then proceeds to the second phase: depth-first progressive repair. In this phase, the ByteTrace tool performs bytecode instrumentation on the function modified by the current patch $`p_{d-1}`$. It collects execution-level dynamic information, including variable states, control-flow paths, and call stacks. This information is incorporated into a new prompt to guide the generation of the next patch $`p_d`$ based on $`p_{d-1}`$. After each depth attempt, the patch is validated. If it passes all tests, the repair is deemed successful. If it fails to compile or encounters fatal errors, the current repair path is abandoned, and the system returns to breadth-based exploration.

LPR tests a maximum of $`B`$ rounds of breadth-based fixes on each buggy, with a maximum of $`D`$ depth-based fixes per round. If all $`B \times D`$ repair attempts fail, the system marks the current buggy as unrepairable.

Experimental Setup

Research Questions

In this paper, we investigate the following research questions (RQs):

-

RQ1: Can DynaFix outperform the SOTA APR approaches? We evaluate DynaFix on the Defects4J benchmark dataset and compare its repair effectiveness with a set of SOTA APR techniques.

-

RQ2: How effective is DynaFix in enhancing LLM-based APR? We evaluate the effectiveness of DynaFix in improving the repair capability of LLMs by comparing different types of feedback, and further investigate the role of execution-level dynamic information and iterative mechanisms in repairing complex bugs.

-

RQ3: How do different LPR settings affect DynaFix’s repair effectiveness and search efficiency? We investigate the impact of varying LPR search parameters on repair effectiveness and LLM resource consumption. We further evaluate DynaFix’s search efficiency under the LPR strategy, comparing maximum patch attempts per bug with those of the baseline methods.

-

RQ4: How each component of DynaFix contributes to repair effectiveness? We analyze the impact of different types of dynamic information at the execution level collected by ByteTrace and the contribution of the LPR strategy to overall repair performance.

Datasets

Our experiment adopted the widely used Defects4J benchmark , which includes 835 real-world bugs from 17 open-source repositories in v2.0. The latest update removes five bugs, leaving 830 for our study. Following previous work , these bugs are classified into 483 single-function bugs and 347 multi-function bugs. The single-function subset is further divided into v1.2 (255 bugs) and v2.0 (228 bugs). For each bug, Defects4J provides a buggy and a fixed version, along with a corresponding test suite that reproduces the bug and validates the fix. This setup allows realistic evaluations based on DynaFix in debugging scenarios and facilitates fair comparisons with existing APR methods on a unified benchmark.

Baselines and Metrics

In RQ1, we compare DynaFix against 11 SOTA APR systems, covering 4 paradigms: 5 LLM-based approaches including FitRepair , Repilot , GAMMA , AlphaRepair , and GIANTREPAIR ; 4 deep learning-based methods including ITER , SelfAPR , Tare , and KNOD ; 1 template-based technique TBar ; and 1 agent-based approach RepairAgent . In RQ2, we compare pure LLMs, LLMs with JUnit exception messages, and LLMs with fine-grained execution-level feedback. This allows us to assess the benefits of execution-level feedback over coarse-grained signals and the value of iterative utilization in repairing complex bugs. In RQ3, we evaluate DynaFix’s search efficiency under the LPR strategy using the maximum patch attempts per bug, defined as the product of the maximum number of iterations and the number of candidate patches per iteration. we include nine of the eleven most effective baselines from RQ1, excluding Tare and TBar due to unreported search details. In RQ4, we perform an ablation study on DynaFix, using prompts with specific information added or removed as baselines to investigate the contributions of each information component to APR performance.

A plausible patch is defined as one that passes all provided unit tests, and a correct patch as a plausible patch that is semantically equivalent to the developer’s fix. For evaluation, we follow the evaluation criteria of existing studies , and compare the number of bugs correctly fixed by each baseline. Because correctness validation requires substantial manual effort, RQ1 analyses are based on correct patches, whereas other experiments are evaluated using plausible patches.

Implementation and Configuration

Configuration. We used GPT-4o as the underlying LLM, accessed via the OpenAI API . Following Xu et al.’s and Xia et al.’s work, the temperature is set to 1.0 to balance diversity and determinism. For each bug, the LLM generates up to 35 candidate patches, determined by the breadth and depth of the exploration of DynaFix. For all baseline APR systems, we directly adopt the official experimental results reported in their respective publications.

DynaFix. We implemented the ByteTrace tool in Java to capture the execution-level dynamic information at runtime, while the core repair logic of DynaFix is implemented in Python. Based on the RQ3 experiments, we set the LPR strategy configuration to a maximum exploration breadth of 7 and a depth of 5. Unlike earlier APR studies that allocate up to 5 hours to repair a single bug, ByteTrace’s efficient tracing and the rapid generation of LLM patches substantially reduce runtime, with most of the time spent in the testing phase. Consequently, each repair attempt is limited to 30 minutes, allowing multiple iterations until a successful repair is achieved or the exploration limit is reached.

Fault localization. To isolate repair effectiveness from the influence of localization accuracy, we adopt perfect fault localization provided by the official Defects4J dataset. All the baselines also operate under the identical perfect localization settings, ensuring fairness and comparability.

Results

RQ1: Effectiveness over the SOTA

Number of Bugs Fixed

We evaluate DynaFix against SOTA APR methods on Defects4J v1.2 and v2.0. To ensure fairness, all methods were compared in perfect fault localization settings. For reproducibility, we use the repair data released by each respective APR method. Since bug coverage varies between methods, we normalize the results by retaining only the 483 single-function bugs selected in this study and discarding all data outside this scope for fair comparison.

It is worth noting that DynaFix uses function-level bug units for repair, whereas some baselines adopt function-level fault localization and others rely on line-level localization. These differences reflect inherent design choices rather than evaluation bias. Table [tab:comparison] summarizes the number of correct patches produced by each APR method. Due to space constraints, detailed results for v2.0 are provided in our open-source repository1.

As shown in Table [tab:comparison], DynaFix has the highest number of correct patches in both datasets, repairing a total of 186 single-function bugs and outperforming all baselines. Specifically, on v1.2, DynaFix fixed 100 bugs, which is 14 more than the strongest baseline GIANTREPAIR, while on v2.0, it fixed 86 bugs compared to GIANTREPAIR’s 83. Notably, GIANTREPAIR aggregates the outputs of four LLM models, while DynaFix achieves superior performance with only a single model augmented with execution-level dynamic information. Compared to other strong baselines, DynaFix repaired 39 more bugs than RepairAgent (an improvement of 26.5%), 56 more than FitRepair (+43.1%), 71 more than KNOD (+61.7%), and 74 more than Repilot (+66.1%).

/>

/>

/>

/>

// Runtime context at line 192 -> Local Variable

headerBuf = [116, 101, 115, ..., 0, 0, ...]

// Developer patch

+ catch (IllegalArgumentException e) {

+ IOException ioe = new IOException("Error detected parsing the header");

+ ioe.initCause(e);

+ throw ioe;

+ }

- currEntry = new TarArchiveEntry(headerBuf);

// DynaFix patch

+ catch (IllegalArgumentException e) {

+ throw new IOException("Invalid tar header encountered", e);

+ }

- currEntry = new TarArchiveEntry(headerBuf);

Complementarity Analysis

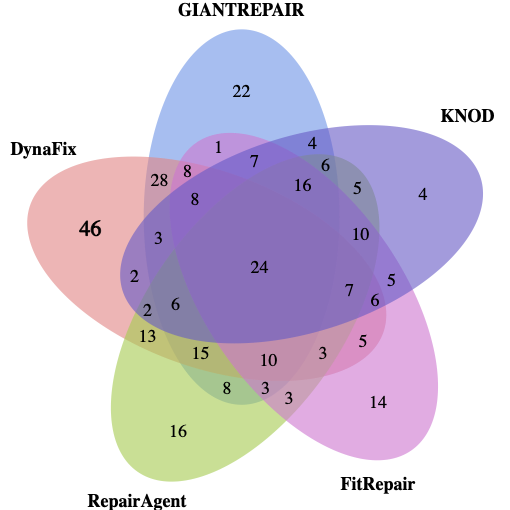

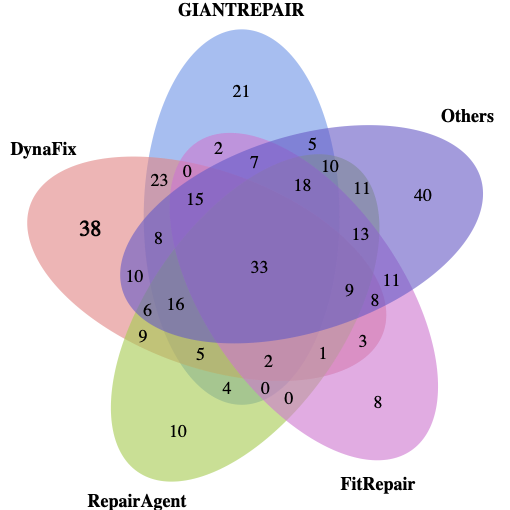

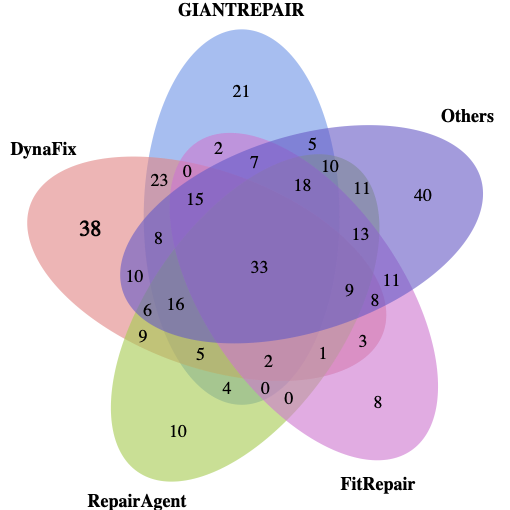

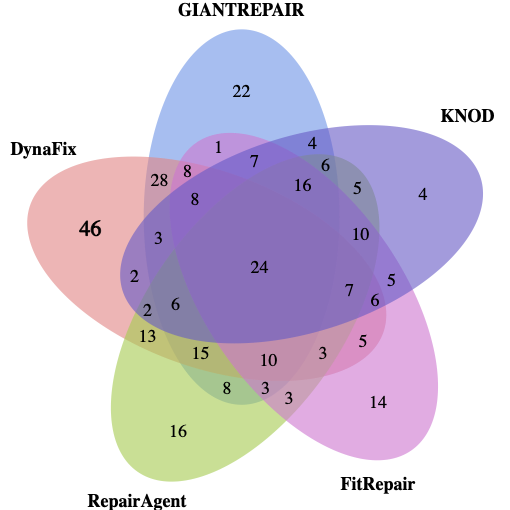

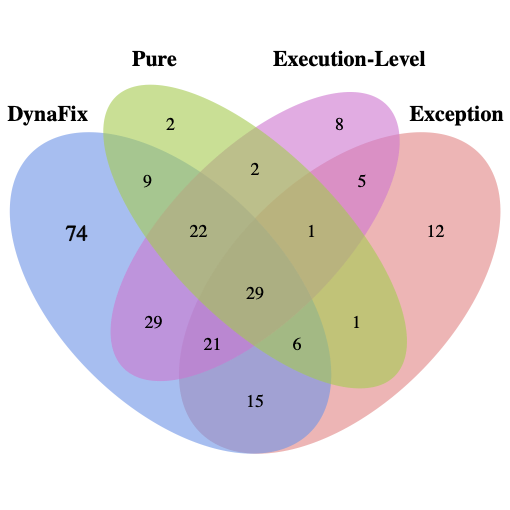

To investigate how DynaFix complements existing APR methods, we analyze the overlaps and differences in fixed bugs across all 483 single-function bugs. Figure 6(a) compares DynaFix with the top four baselines, and Figure 6(b) extends the comparison to all eleven methods. Compared with the top four baselines, DynaFix achieves 46 unique fixes, which is 23 more than GIANTREPAIR. Compared with all eleven baselines, DynaFix still achieves 38 unique fixes. These results indicate that DynaFix effectively leverages the execution-level dynamic information to repair bugs that remain unresolved by other APR approaches.

As an example, Listing

[lst:unique-patch] illustrates a

bug repaired solely by DynaFix. The failure arises from a direct

invocation of new TarArchiveEntry(headerBuf), when headerBuf

contains unparsable data, this call throws an uncaught

IllegalArgumentException, leading to program termination. By

leveraging runtime values of local variables, DynaFix detects the

invalid input, precisely localizes the exception trigger to line 192,

and generates a correct patch. In contrast, existing APR techniques can

only recognize that an exception occurs, without identifying the

fault-inducing statement or the specific type of invalid input. The

limitation leaves a substantially larger search space and reduces the

likelihood of generating an effective patch.

Answer to RQ1: DynaFix repairs 186 single-function bugs in Defects4J, exceeding 11 SOTA methods on both v1.2 and v2.0; It contributes 38 unique repairs that no baseline achieves. These results demonstrate that DynaFix iteratively leverages execution-level dynamic information, enabling more effective bug localization and patch generation, and thus achieving superior and complementary repair capabilities beyond existing methods.

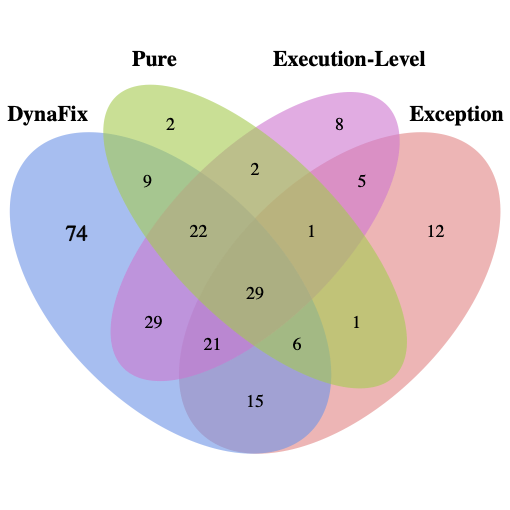

RQ2: Effectiveness of DynaFix in Enhancing LLM-Based APR

To evaluate the effectiveness of DynaFix in enhancing LLM repair capabilities, we conducted experiments on the full Defects4J v2.0 dataset, which contains 483 single-function and 347 multi-function bugs. We compared four settings: (i) Pure LLM without additional information, (ii) LLM with traditional JUnit exception messages, (iii) LLM with execution-level dynamic information, and (iv) DynaFix, which integrates dynamic information with iterative repair. Table [tab:dynafix_vs_exception] summarizes the results. For single-function bugs, Pure LLM fixed only 72 bugs (14.9%). Adding exception messages or execution-level information improved repair rates to 18.6% and 24.2%, respectively, indicating that dynamic information provides greater benefit than exception messages. However, relying solely on execution-level dynamic information brings only limited improvement. When combined with an iterative mechanism, DynaFix repaired 206 bugs with a repair rate of 42.6%, representing a 27.7% improvement over Pure LLM and more than doubling the performance of either baseline. This demonstrates that the iterative mechanism is crucial for exploiting the value of dynamic information.

For multi-function bugs, exception messages led to slightly better results (18 fixes) than execution-level information (15 fixes), likely because the verbose and complex nature of multi-function traces reduces the effectiveness of single-shot reasoning. Nevertheless, when augmented with iteration, DynaFix fixed 31 bugs (8.9%), more than tripling the performance of Pure LLM and significantly outperforming both baselines. These findings suggest that execution-level information alone does not generalize well to complex cases, but iteration enables the LLM to progressively extract useful signals.

We further analyzed DynaFix’s unique repair capabilities, as shown in Figure 9. For single-function and multi-function bugs, DynaFix achieved 74 and 14 unique fixes, respectively, significantly surpassing the baselines using only execution-level dynamic information or JUnit exception messages. Notably, the exception information baseline achieved more unique fixes in both single-function (12 cases) and multi-function (5 cases) bugs than execution-level dynamic information. This indicates that providing fine-grained dynamic information alone is not necessarily superior to exception messages, but when combined with an iterative mechanism, DynaFix can fully exploit the potential of execution-level dynamic information and achieve unique fixes that other methods cannot cover.

| Bug Type | Enhancement Method | #Bugs | #Plausible | Fix Rate | Δ over Pure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-function | DynaFix | 483 | 206 | 42.6% | +27.7% |

| Execution-Level Info | 483 | 117 | 24.2% | +9.3% | |

| Exception Info | 483 | 90 | 18.6% | +3.7% | |

| Pure | 483 | 72 | 14.9% | - | |

| Multi-function | DynaFix | 347 | 31 | 8.9% | +6.6% |

| Execution-Level Info | 347 | 15 | 4.3% | +2.0% | |

| Exception Info | 347 | 18 | 5.2% | +2.9% | |

| Pure | 347 | 8 | 2.3% | - |

/>

/>

/>

/>

Answer to RQ2: DynaFix significantly enhances LLM-based APR on Defects4J v2.0, repairing 206 single-function bugs (42.6%) and 31 multi-function bugs (8.9%), and outperforming baselines that rely solely on exception messages or execution-level dynamic information. While execution-level information alone provides limited gains, its integration with iterative repair enables significant improvements. DynaFix achieves 74 unique fixes for single-function bugs and 14 unique fixes for multi-function bugs not achieved by the baselines.

RQ3: Impact of LPR Search Parameters on DynaFix’s Repair Effectiveness and Search Efficiency

To evaluate how search breadth and depth influence the performance of the LPR strategy, we conducted experiments under different parameter settings. Since varying both parameters requires multiple LLM invocations and incurs high computational costs, we selected 255 single-function bugs from Defects4J v1.2 for evaluation. This dataset is a representative subset of Defects4J v2.0, with similar distributions of bug difficulty and type, allowing the results to be reasonably extrapolated. Figure 10 shows the trend of the number of plausible patches generated and the average cost per fixed bug repaired under fixed depth and fixed breadth configurations.

When the search depth is fixed at 3 (Figure 10a), the repair cost increases steadily as the search breadth increases. The number of plausible patches rises initially, peaks at a breadth of 7, and then stabilizes. When the search breadth is fixed at 5 (Figure 10b), increasing depth similarly increases the repair cost, while the patch benefit gradually diminishes once the depth exceeds 5.

This phenomenon can be explained as follows. Beyond breadth 7 or depth 5, the search has already covered most high-quality patches, and further expansion primarily introduces redundant, low-quality variants. Moreover, the generative capacity of the LLM is inherently bounded; expanding the search space no longer produces substantially more effective patches, but it continues to raise computational costs, leading to diminishing returns. Based on this trade-off, we adopt a breadth of 7 and a depth of 5 as the default LPR configuration in DynaFix to balance patch output and efficiency.

After determining the default LPR configuration, we further evaluate search efficiency across approaches. Unlike traditional APR systems where runtime dominates cost, LLM-based repair is constrained by token-based billing. As a result, the number of patch attempts directly translates into economic overhead, making this metric particularly relevant. To capture this overhead, we introduce the metric maximum patch attempts per bug, defined as the product of the maximum number of iterations and the number of candidate patches per iteration. This metric reflects the worst-case repair effort for each system and complements existing measures such as repair rate and runtime. For the fairness of comparison, we exclude Tare and TBar due to missing data in their original publications. As shown in figure 11, most existing baselines adopt large-scale patch searches, often generating over 500 candidates per bug and sometimes exceeding 5,000, which reduces search efficiency. In contrast, guided by fine-grained dynamic execution information, DynaFix requires only 35 iterations with a single candidate patch per iteration. This reduces the maximum attempts by over 70% compared to the most efficient baseline, RepairAgent, while still achieving superior repair effectiveness.

Answer to RQ3: Search breadth and depth significantly influence DynaFix’s repair performance and efficiency. Increasing either parameter initially produces more plausible patches but leads to diminishing returns and higher cost once the breadth exceeds 7 or the depth exceeds 5. With optimized settings, DynaFix requires only 35 patch attempts per bug, over 70% fewer than the most efficient baseline, indicating that precise dynamic execution guidance and parameter tuning enable efficient repair with minimal search overhead.

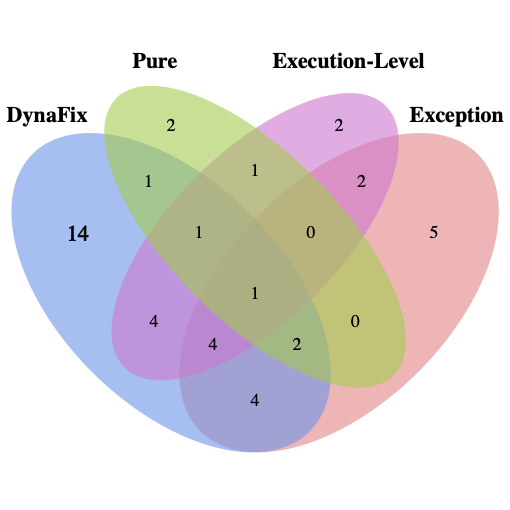

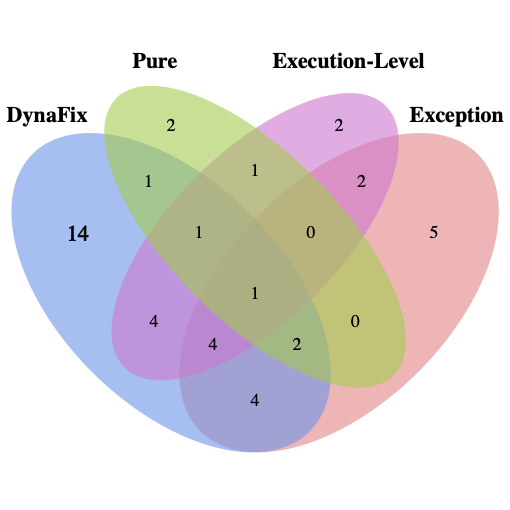

RQ4: Contribution of individual Component in DynaFix

To evaluate the contribution of individual components, we conducted an ablation study on 255 single-function bugs from Defects4J v1.2. Since RQ3 has already examined the sensitivity to search depth and breadth, these parameters were fixed to their optimal values. We varied only the dynamic execution information provided to the LLM and the use of the LPR strategy. The evaluated configurations are:

-

w/o Local Variables: Removing local variable values from the prompt.

-

w/o Control Flow: Removing control flow traces from the prompt.

-

w/o Method Call: Removing call stack and function call details.

-

w/o LPR: Disabling the hierarchical progressive repair (LPR) strategy.

-

Pure: Only the buggy function code is provided, without any dynamic information.

-

Default: DynaFix default configuration, Combining all execution-level dynamic information with the LPR strategy.

| Setting | #Plausible | Fix Rate | $`\Delta`$ from Default |

|---|---|---|---|

| w/o Local Variables | 97 | 38.0% | -5.5% |

| w/o Control Flow | 102 | 40.0% | -3.5% |

| w/o Method Call | 101 | 39.6% | -3.9% |

| w/o LPR | 55 | 21.6% | -21.9% |

| Pure | 34 | 13.3% | -30.2% |

| Default | 111 | 43.5% | – |

Table [tab:ablation-singlefunc] summarizes the results. Every component improves repair effectiveness, but the LPR strategy has the largest impact. Removing LPR reduces the fix rate by 21.9% and eliminates 56 plausible patches, highlighting its central role in simulating the iterative debug–fix cycle and enabling the LLM to exploit execution feedback effectively.

Among the execution-level features, local variables contribute the most. Removing them decreases the fix rate by 5.5%, corresponding to 14 fewer repairs. Excluding control flow reduces the fix rate by 3.5% with nine fewer repairs, while excluding method calls decreases it by 3.9% with ten fewer repairs. These smaller drops suggest partial redundancy, as the combination of LPR and the remaining features allows the model to infer some missing information. For example, when control flow traces are absent, variations in local variables and call stack patterns still provide clues about branch execution. Nevertheless, redundancy is only partial. For certain bugs, the absence of any single feature can prevent a correct fix, even when the other two features and LPR are present. This underscores the complementary role of dynamic execution information: each feature contributes to repair effectiveness, yet none can fully substitute for another.

Overall, the ablation study demonstrates that DynaFix achieves its effectiveness by combining detailed execution feedback with the LPR strategy. Dynamic feedback alone provides only marginal improvements, and LPR alone cannot fully exploit incomplete data. Their integration, however, aligns the repair process with real-world debugging practices. As a result, the Default configuration fixes 77 more bugs and attains a 30.2% higher repair rate compared to the Pure LLM baseline.

Answer to RQ4: The ablation study shows that all components contribute to repair effectiveness. The LPR strategy has the most significant impact, while execution-level features provide complementary benefits that together maximize repair performance.

Threats to Validity

Our study may be affected by potential threats to internal and external validity.

Threats to Internal Validity. One internal threat is the manual evaluation of patch correctness. Following established APR protocols , we carefully inspected each patch to confirm it fixed the underlying bug rather than bypassing tests. All validated patches and reproduction code are publicly available.

Another internal threat concerns potential data leakage, as the LLM may have been trained on open-source repositories partially overlapping with Defects4J . Prior work suggests such overlap has limited impact on APR, since training corpora rarely contain complete bug–fix pairs, making memorization of effective repairs unlikely. Furthermore, all LLM-based APR baselines face the same risk, preserving fairness in comparison. To further mitigate this concern, we evaluated 24 multi-function bugs newly introduced in Defects4J v3.0, which were not included in prior benchmarks. These bugs are more complex and harder to memorize. DynaFix repaired 9 of the 24 bugs, compared to 2 by the underlying LLM, demonstrating generalization to previously unseen bugs and reducing concerns about data leakage.

Finally, we relied on reported results for the baseline instead of re-running all tools to avoid inconsistencies from different configurations. While this is common practice, future work could re-execute all baselines in a unified environment for stricter reproducibility.

Threats to External Validity. A primary external threat is that the effectiveness of DynaFix may not be generalizable to other datasets. To address this concern, we evaluated it on two different benchmarks, Defects4J v1.2 and v2.0, and observed consistently solid performance, achieving SOTA results on both.

Another external threat arises from the reliance on a single LLM in the main experiments, which could introduce model-specific bias. To test robustness, we re-ran DynaFix using the open-source DeepSeek model . On 483 single-function bugs in Defects4J, this variant generated plausible patches for 228 bugs, again outperforming baseline approaches.

Finally, our evaluation is limited to Java programs. While DynaFix leverages execution-level instrumentation that is in principle language-agnostic, its effectiveness has only been demonstrated in Java. Extending evaluation to multiple programming languages is a promising direction for future work to more rigorously assess generality and robustness.

Related Work

APR has been studied from multiple perspectives, including predefined repair templates , heuristic rules , program synthesis , and more recently, deep learning .

Among recent LLM-based APR studies, the following works are most relevant to our research. FitRepair incorporates the plastic surgery hypothesis into LLM-based APR via patch-knowledge and repair-oriented fine-tuning. GIANTRepair reduces the search space by extracting patch skeletons from LLM outputs and instantiating them with contextual information.ChatRepair introduces dialogue-driven repair, where prompts are constructed using test failure information and past repair attempts. RepairAgent treats the LLM as an autonomous agent, leveraging dynamic prompts and a state machine to iteratively plan repair actions. SelfAPR proposes to utilize compiler and test diagnostics during the LLM’s self-supervised training to improve APR performance. Self-Debug improves program generation in APR tasks by generating code explanations from the LLM in a chain-of-thought manner. Despite these advances, most LLM-based methods either rely heavily on static information (e.g., source code and error messages) or only incorporate coarse-grained runtime feedback, leaving the potential of fine-grained dynamic signals underexplored.

In terms of leveraging execution-level dynamic information, TraceFixer enhances APR by incorporating local variable values and expected program states during CodeT5 fine-tuning, while Towards Effectively Leveraging Execution Traces systematically analyzes the potential of execution traces in APR and demonstrates their value for explaining failing test behaviors. Unlike these works, DynaFix not only captures more fine-grained execution-level dynamic information but also deeply integrates it into the LLM-based iterative repair process. This allows DynaFix to more closely simulate human-like debugging, enabling a more effective use of execution-level information.

Conclusion

In this paper, we propose DynaFix, an LLM-based APR framework that integrates execution-level dynamic information into an iterative repair workflow. DynaFix uses our ByteTrace tool to collect runtime information and combines it with a hierarchical progressive repair strategy, enabling more precise fault localization and context-aware patch generation in a debug-and-fix workflow. Evaluation on Defects4J v1.2 and v2.0 shows that DynaFix repaired 186 single-function bugs and fixed 38 previously unresolved bugs. Compared with LLM baselines using only exception information, DynaFix consistently improves repair performance for both single-function and multi-function bugs. These results suggest that integrating execution-level feedback into automated repair can better align with real-world debugging practices, enhancing the effectiveness of LLM-based program repair for complex bugs.

Data Availability

To facilitate reproducibility, we have provided a comprehensive replication package that includes the DynaFix framework, the ByteTrace tool, and all experimental datasets used in this study. The package has been submitted to the conference submission system and will be made publicly available upon acceptance of the paper.

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)

A Note of Gratitude

The copyright of this content belongs to the respective researchers. We deeply appreciate their hard work and contribution to the advancement of human civilization.-

Link will be provided upon publication. ↩︎