Dream2Flow Bridging Video Generation and Open-World Manipulation with 3D Object Flow

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Dream2Flow Bridging Video Generation and Open-World Manipulation with 3D Object Flow- ArXiv ID: 2512.24766

- Date: 2025-12-31

- Authors: Karthik Dharmarajan, Wenlong Huang, Jiajun Wu, Li Fei-Fei, Ruohan Zhang

📝 Abstract

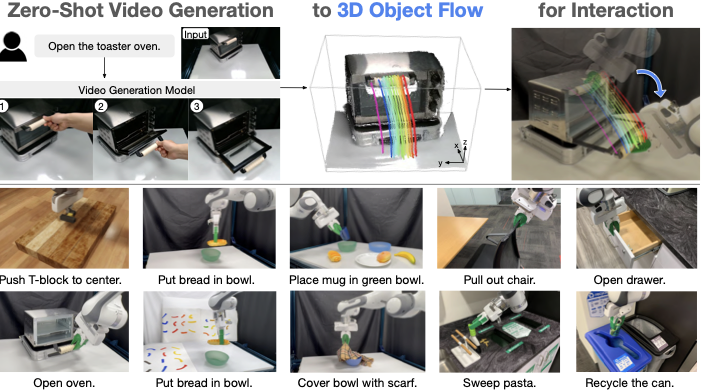

Generative video modeling has emerged as a compelling tool to zero-shot reason about plausible physical interactions for open-world manipulation. Yet, it remains a challenge to translate such human-led motions into the low-level actions demanded by robotic systems. We observe that given an initial image and task instruction, these models excel at synthesizing sensible object motions. Thus, we introduce Dream2Flow, a framework that bridges video generation and robotic control through 3D object flow as an intermediate representation. Our method reconstructs 3D object motions from generated videos and formulates manipulation as object trajectory tracking. By separating the state changes from the actuators that realize those changes, Dream2Flow overcomes the embodiment gap and enables zero-shot guidance from pre-trained video models to manipulate objects of diverse categories-including rigid, articulated, deformable, and granular. Through trajectory optimization or reinforcement learning, Dream2Flow converts reconstructed 3D object flow into executable low-level commands without task-specific demonstrations. Simulation and real-world experiments highlight 3D object flow as a general and scalable interface for adapting video generation models to open-world robotic manipulation. Videos and visualizations are available at https://dream2flow.github.io/.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **3D Object Flow Interface:** - **Simplified:** The robot follows the 3D object motion from synthetic videos to learn new tasks. - **Intermediate:** By tracking object movements predicted by vision models in generated videos, the robot plans its actions. - **Advanced:** Dream2Flow extracts 3D object flow from text-conditioned video generations and uses this as a target for robotic action.-

Action Inference:

- Simplified: The robot is designed to act based on the object motion predicted by vision models.

- Intermediate: Based on 3D object flow, the robot plans actions necessary to complete tasks.

- Advanced: Given the state of the robot and position of objects, Dream2Flow optimizes actions to track predicted 3D object flow.

-

Application in Real Domains:

- Simplified: Dream2Flow can perform various tasks using RGB-D observations and language instructions.

- Intermediate: Using 3D object flows extracted from synthetic videos, robots complete tasks in real-world settings.

- Advanced: In both simulation and real domains, Dream2Flow performs diverse tasks given only RGB-D observations and text commands.

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

Robotic manipulation in the open world could greatly benefit from visual world models that predict how an environment would evolve given an agent’s interactions. Recent advances in generative video modeling have produced systems capable of zero-shot synthesizing minute-long, high-fidelity clips of physical interactions in pixel space, conditioned on an unseen initial image and an open-ended task instruction . Such video models implicitly capture intuitive physics and rich priors of object properties and interactions, making them compelling for open-world manipulation settings where a robot is tasked to complete novel tasks in unseen environments through partial observations.

Despite their promise, it remains unclear what role such models should serve in a robot manipulation system. Most frontier video generators produce the best interaction clips with a human embodiment. This reflects where supervision is most abundant as human interactions are significantly more broadly documented than those of robots. But this becomes a challenge for using them in robotic manipulation due to the embodiment gap and hence the different action spaces.

We propose extracting actionable signals from their visual predictions of human interactions, which will then be enacted by a robot. This essentially separates the state changes in the real world from the actuators that realize those changes. Our proposed method, Dream2Flow, employs 3D object flow as an intermediate interface that bridges high-level video simulation with low-level robot actions. Dream2Flow works because, despite occasional visual artifacts, state-of-the-art video generation models often predict physically plausible object motions that align with the task intent in open-world manipulation tasks. Then, given generated videos, instead of trying to directly mimic the human motions for completing a given task, we focus on reconstructing and reproducing the object flows in 3D.

The problem is thus reduced to object trajectory tracking: the robot’s job is to manipulate the object to closely follow the generated flow that the video model imagined. This approach cleanly separates what needs to happen (i.e., state changes in an environment) from how a particular embodiment achieves it with respect to its kinematic and dynamic constraints (i.e., actions). Importantly, it seamlessly interfaces with both motion planners and sensorimotor policies—the extracted object motion in 3D serves as the tracking goal for trajectory optimization or a reinforcement learning policy, which then yields a sequence of low-level robot joint commands.

Leveraging off-the-shelf models and tools, we demonstrate an autonomous pipeline that 1) generates a text-conditioned video of plausible interaction , 2) obtains 3D object flow by performing depth estimation and point tracking using vision foundation models , and 3) synthesizes robot actions that realize this flow using trajectory optimization and reinforcement learning. Notably, this design enjoys a number of desirable benefits in manipulation tasks. By first leveraging video models—pre-trained on large corpora of human activities—to interpret and ground open-ended language commands in visual predictions, our system inherits a scalable mechanism for task specification. These predictions are then distilled into reconstructed 3D object flow, a representation that naturally captures diverse object interactions spanning rigid, articulated, deformable, and granular objects. Together, this synergy enables an end-to-end pipeline that performs open-world manipulation directly from visual perception and language, without task-specific data or training.

In summary, our key contributions are:

-

We propose 3D object flow as an interface for adapting off-the-shelf video generation models for open-world manipulation by formulating it as an object trajectory tracking problem.

-

We demonstrate its effectiveness by implementing the approach in both simulated and real domains, which performs diverse tasks given only RGB-D observations and language instructions in a zero-shot manner.

-

We examine the properties of 3D object flow by comparing it with alternative intermediate representations and by studying its key design choices as well as generalization properties.

Related Works

Task Specification in Manipulation

Specifying tasks for the wide range of manipulation problems spans symbolic, learning-based, outcome-driven, and object-centric interfaces. Classical approaches encode goals and constraints with symbolic formalisms such as PDDL and temporal logics, or optimize cost-augmented formulations . Learning-based systems specify tasks often through language and perception, mapping instructions to actions via language-conditioned visuomotor policies and vision–language–action models . Outcome-based specification sets goals by example observations, e.g., image goals with goal-conditioned policies , and some works incorporate force targets . Object-centric alternatives rely on descriptors or keypoints to capture task-relevant structure . Recently, foundation models enable higher-level interfaces that compile intent into actionable specifications via code , 3D value maps akin to potential fields , keypoint relations , or affordance maps .

2D/3D Flow in Robotics

Dense motion fields—optical flow, point tracks, and 3D scene/object flow—provide an embodiment-agnostic, mid-level interface for manipulation . In scene-centric formulations, policies parameterize or condition on motion in 2D or 3D to decide actions, with point/keypoint interfaces unifying perception and action and with action-flow improving precision . In object-centric formulations, desired object motion is specified independently of embodiment and then converted into actions via policy inference, planning, and optimization . When actions are absent, retargeting with predicted tracks and dense correspondences offers a practical bridge across embodiments . Advances in perception and tracking such as RGB-D motion-based segmentation, 3D scene flow in point clouds, zero-shot monocular and ToF-based scene flow, rigid-motion learning, refractive flow for transparent objects, deformable and articulated reconstruction, and structured scene representations make the interface reliable. Flow-derived supervision further supports learning, and video generation supplies plausible visual rollouts for planning and imitation . Our approach follows the object-centric path by reconstructing 3D object flow from language-conditioned generations and tracking it under embodiment constraints, complementing other flow-conditioned policy representations .

Video Models for Robotics

Recent work increasingly integrates video models across robotic tasks in various ways . They can serve as auxiliary training objectives , as reward models , as policies , or as a simulator for the environments . Notably, predictive modeling in robotics can leverage video frame prediction as a form of world model. By simulating future visual observations, these models can enable visual planning and manipulation by anticipating how the environment will evolve. For example, a video generative model can simulate long-horizon task outcomes, effectively acting as a visual planner . Video models in this way can also serve as as dynamics models . Another notable direction is that video generation can directly provide new training data for robot learning. Several recent works devise frameworks to imagine new trajectories in the form of videos and use them to train or finetune policies, particularly for imitation learning .

Method

style="width:99.0%" />

style="width:99.0%" />

Herein, we introduce the problem formulation of Dream2Flow in Sec. 3.1. Leveraging 3D object flow as an interface, we subsequently discuss how to extract 3D object flow from video generations in Sec. 3.2 and how to plan actions with 3D object flow for manipulation in Sec. 3.3.

Problem Formulation

Given a task instruction $`\ell`$, an initial RGB-D observation $`(I_0 \in \mathbb{R}^{H\!\times\!W\!\times\!3},\, D_0 \in \mathbb{R}^{H\!\times\!W})`$, and a known camera projection $`\Pi`$ (intrinsics and extrinsics to the robot frame), our goal is to output an action sequence $`u_{0:H-1} \in \mathcal{U}^H`$ that accomplishes the task by following an object motion inferred from a generated video. We make no assumption about a specific action parameterization: $`\mathcal{U}`$ may represent motion primitives, end-effector poses, or low-level controls.

Extracting 3D Object Flow. From $`(I_0,\ell)`$, an image-to-video model produces frames $`\{V_t\}_{t=1}^T`$, and a video-depth estimator provides a per-frame depth sequence $`\{Z_t\}_{t=1}^T`$. Using a binary mask $`M`$ of the task-relevant object, and the projection $`\Pi`$, we lift masked image points with $`Z_{1:T}`$ to obtain an object-centric 3D trajectory $`P_{1:T} \in \mathbb{R}^{T\times n\times 3}`$ in the robot frame; we refer to $`P_{1:T}`$ as the 3D object flow.

Action Inference with 3D Object Flow. We represent state as the task-relevant object and the robot: $`x_t = (x_t^{\text{obj}}, r_t)`$, where $`x_t^{\text{obj}} \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times 3}`$ are object points and $`r_t`$ denotes the robot state. Let $`f`$ be a dynamics model and $`\hat{x}_{t+1} = f(\hat{x}_t, u_t)`$ with $`\hat{x}_0 = x_0`$. At each planning step $`t`$, we use a time-aligned target $`\tilde{P}_t \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times 3}`$ derived from the video object flow (e.g., via uniform time-warping or nearest-shape matching). We formulate action inference as an optimization problem:

\begin{equation*}

\label{eq:problem}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{\{u_t \in \mathcal{U}\}} \ \ & \sum_{t=0}^{H-1} \lambda_{\text{task}}\big(\hat{x}^{\text{obj}}_t, \tilde{P}_t\big) + \lambda_{\text{control}}(\hat{x}_t, u_t) \\

\text{s.t.}\ \ & \hat{x}_{t+1} = f(\hat{x}_t, u_t), \quad \hat{x}_0 = x_0,\\

& \lambda_{\text{task}}\big(\hat{x}^{\text{obj}}_t, \tilde{P}_t\big) = \sum_{i=1}^n \big\|\hat{x}^{\text{obj}}_t[i]-\tilde{P}_t[i]\big\|_2^2,

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}Section 3.3 instantiates $`\mathcal{U}`$ and $`f`$ for different domains.

Extracting 3D Object Flows from Videos

Video Generation: Given the task language instruction $`\ell`$ and an RGB image of the workspace without the robot visible $`I_0\!\in\!\mathbb{R}^{H \times W \times 3}`$, Dream2Flow uses an off-the-shelf image-to-video generation model to produce an RGB video $`\{V_t\}_{t=1}^T`$ with $`V_t\!\in\!\mathbb{R}^{H \times W \times 3}`$, showing the task being performed. We do not include the robot in the initial frame or mention the robot in the text prompt, as we empirically find that current image-to-video generation models not specifically finetuned on robotics data tend to produce physically implausible fine-grained interactions, and consequently have worse object trajectories (for details see Appendix 5.1).

Video Depth Estimation: Given the generated video, Dream2Flow leverages SpatialTrackerV2 to estimate per-frame depth $`\{\tilde{Z}_t\}_{t=1}^T`$, $`\tilde{Z}_t\!\in\!\mathbb{R}^{H \times W}`$. Due to the scale-shift ambiguity of monocular video, we compute global $`(s^\star,b^\star)`$ by aligning the first frame to the initial depth $`D_0`$ from the robot, and obtain calibrated depths $`Z_t = s^\star\tilde{Z}_t + b^\star`$.

3D Object Flow Extraction: 3D object flow aims to produce 3D trajectories $`P_{1:T}\!\in\!\mathbb{R}^{T \times n \times 3}`$ with visibilities $`V\!\in\!\{0,1\}^{T\times n}`$ for the task-relevant object. We first localize the relevant object using Grounding DINO to produce a bounding box from $`(I_0,\ell)`$, and then use the box to prompt SAM 2 for a binary mask. From the masked region at $`t{=}1`$, we sample $`n`$ pixels and track them across the video with CoTracker3 to obtain 2D trajectories $`c_i^t`$ and visibilities $`v_i^t`$. Visible points are lifted to 3D using the calibrated depths and camera intrinsics/extrinsics, producing $`P_{1:T}`$ as in Sec. 3.1.

Action Inference with 3D Object Flow

Simulated Push-T Domain. For tasks involving non-prehensile manipulation, such as the Push-T task, Dream2Flow uses a push skill primitive parameterized with the start push position on a flat table $`(c_x, c_y)`$, a unit push direction $`(\Delta c_x, \Delta c_y)`$, and the distance of the push $`d`$. In this setting, we learn a forward dynamics model that takes as input a feature-augmented particles $`\Tilde{x}_t \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times 14}`$ of the whole scene and produces $`\Delta \hat{x}_{t+1}`$, the delta of positions of each point for the next timestep. The features associated with each point consist of the position, RGB color, and normal vector as determined from camera observations along with the push parameters (as further elaborated in Appendix 5.2).

To optimize the 3D object flow following cost with the learned dynamics model, we use random-shooting, where $`r`$ push skill parameters are randomly sampled such that all pushes will make contact with the object of interest at different points and directions. Then, we select the push skill parameter out of $`r`$ ones that has the least cost according to the predicted point positions from the dynamics model. For determining which timestep from the video should be used in the cost function, we find the timestep $`t^{\star}`$ where the points of the relevant object in the trajectory are closest to the current observed points with further details in Appendix 5.3.

Real-World Domain. We use absolute end-effector poses as the action space and a rigid-grasp dynamics model for the real robot domain. With this combination, we first proceed to grasp the desired part from the relevant object, and then use the dynamics model and point-flow following objective to move the end-effector such that the grasped part moves in a fashion similar to the video. We use AnyGrasp to propose candidate grasps on the object of interest, but these grasps may not lie exactly on the desired part. We select the grasp closest to the thumb as detected from the video by HaMer , as we observe that in generated videos, the hand tends to interact with the relevant part of an object, such as the handle.

The rigid-grasp dynamics model assumes that the grasped part is rigid; consequently, the prediction of point positions to the next timestep can be described by a sequence of rigid transformations for the grasped subset, while non-grasped points remain unchanged. To produce a trajectory of end-effector poses, Dream2Flow directly optimizes the objective using PyRoki , incorporating pose smoothness and reachability costs as $`\lambda_{\text{control}}`$ in addition to the 3D object-flow following cost $`\lambda_{\text{task}}`$ as in Appendix 5.6.

Simulated Door Opening Domain. For the Door Opening task, we use reinforcement learning to learn a sensimotor policy which moves the object according to the 3D object flow with SAC . This approach can be viewed as using the simulator as a dynamics model for compiling the optimization process prescribed in Eq. [eq:problem] into a parametric policy in an offline fashion, using 3D object flow as the reward function. Depending on the embodiment used, the action space consists of delta end-effector poses and delta joint angles for the gripper or dexterous hand. The reward function used consists of one term which encourages the end-effector to move toward the current mean object particle position along with another term for encouraging matching the 3D object flow, $`\frac{t^{\star}}{t_{\text{end}}}`$, where $`t^{\star}`$ is the timestep with the closest particle positions to the 3D object flow and $`t_{\text{end}}`$ is the last timestep of the object motion (further details in Appendix 5.8). By training policies with such an object-centric reward, we observe different strategies emerge to accomplish the same object motion across embodiments, including quadruped manipulators, humanoids with dexterous hands, and fixed-base arms with parallel grippers.

Experiments

We seek to answer the following research questions through our experiments: $`\mathbf{\mathcal{Q}1}`$: What are properties of 3D object flow when used as an interface to bridge videos and robot control? $`\mathbf{\mathcal{Q}2}`$: How does Dream2Flow perform compared to alternative interfaces? $`\mathbf{\mathcal{Q}3}`$: How effective is 3D object flow as a reward for learning sensimotor policies? $`\mathbf{\mathcal{Q}4}`$: How does the choice of video model affect Dream2Flow in simulation and in real-world tasks? $`\mathbf{\mathcal{Q}5}`$: How does the choice of dynamics model affect the performance of Dream2Flow?

Tasks

style="width:96.0%" />

style="width:96.0%" />

For evaluation, we consider several tasks involving different types of objects and manipulation strategies (Fig. 2).

Push-T

We develop a simulated Push-T task in OmniGibson , where a T-shaped block is placed with a random position and yaw angle on the wooden platform. It is a success if the T-block ends up within 2cm translation and 15 degrees rotation from the goal position, where the T-shaped block is in the center of the board facing forwards.

Put Bread in Bowl

The Put Bread in Bowl task consists of a fake piece of bread and a green bowl placed randomly on the workspace. A trial is a success if the bread is inside the bowl at the end.

Open Oven

In the Open Oven task, the toaster oven is randomly placed in a semi-circular arc with the orientation towards the base of the robot. A trial is considered a success if the opening angle is at least 60 degrees.

Cover Bowl

The Cover Bowl task starts with a folded scarf placed at a random position and orientation on the workspace, with a blue bowl placed next to it. The trial is a success if the scarf is covering at least 25% of the top of the bowl after the robot finishes execution.

Open Door

In the Open Door task from Robosuite , a door is placed at random positions and orientations on top of a table. Rotating the handle and pulling the door open by at least $`17^\circ`$ without timing out is a success.

Properties of 3D Object Flow as a Video-Control Interface

/>

/>

/>

/>

We run Dream2Flow on the simulated Push-T task with Wan2.1 as the video generation model. For this task only, we allow prompting with a goal image of the T-block in the center, similar to the example final state in Fig. 2, as this task requires accurate movement. We consider 10 different initial states with the same final state. We then proceed to run 10 trials for each initial configuration on different seeds to properly evaluate performance due to the stochastic nature of random shooting, yielding 100 total trials. The result appears in Table 4. We note that in this task, 6 generated videos included substantial morphing of the T-block, which consequently ruined the tracking and downstream execution.

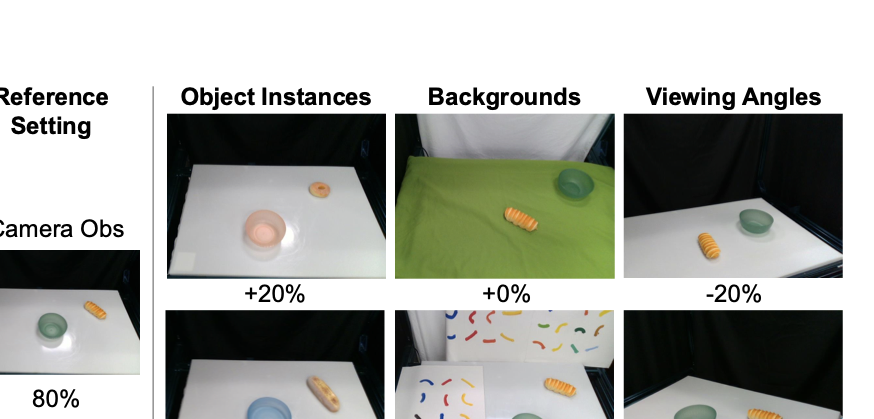

We evaluate Dream2Flow’s ability to perform manipulation with different types of objects with Veo 3 as the video generation model in the real world for 10 trials per task, and report the results in Table 1.

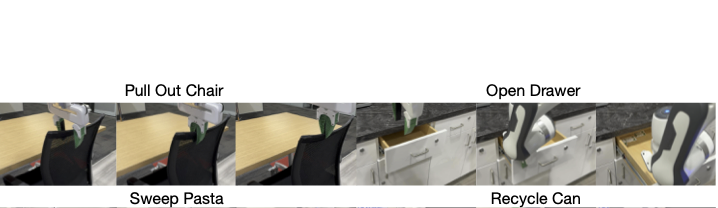

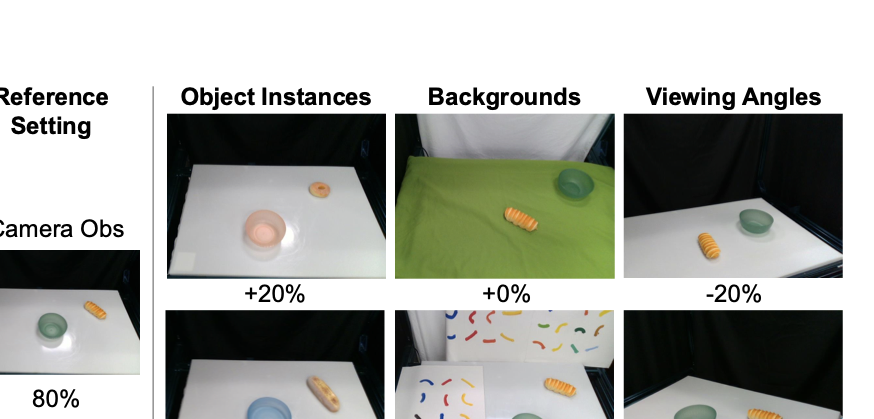

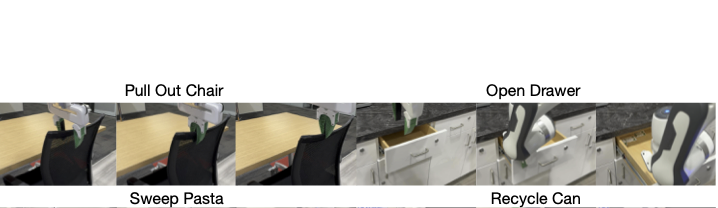

To assess Dream2Flow’s generalization to different object instances, backgrounds, and viewing angles, we conduct an additional five trials each for six different scenarios, as shown in Fig. 3. Compared to the reference setting, with exception of putting a large piece of bread, there is not a significant drop off in performance, suggesting that Dream2Flow inherits some generalization through the use of video generation models. We additionally show that Dream2Flow can perform different tasks from the same scene in Fig. 4 due to the ability of video generation models to follow different task instructions given the same input image. We have additional case studies demonstrating that 3D object flow can be used for downstream manipulation in in-the-wild settings for tasks such as pulling a chair, opening a drawer, sweeping pasta, and recycling a can, as shown in Fig. [fig:pull_fig] and Appendix 5.7.

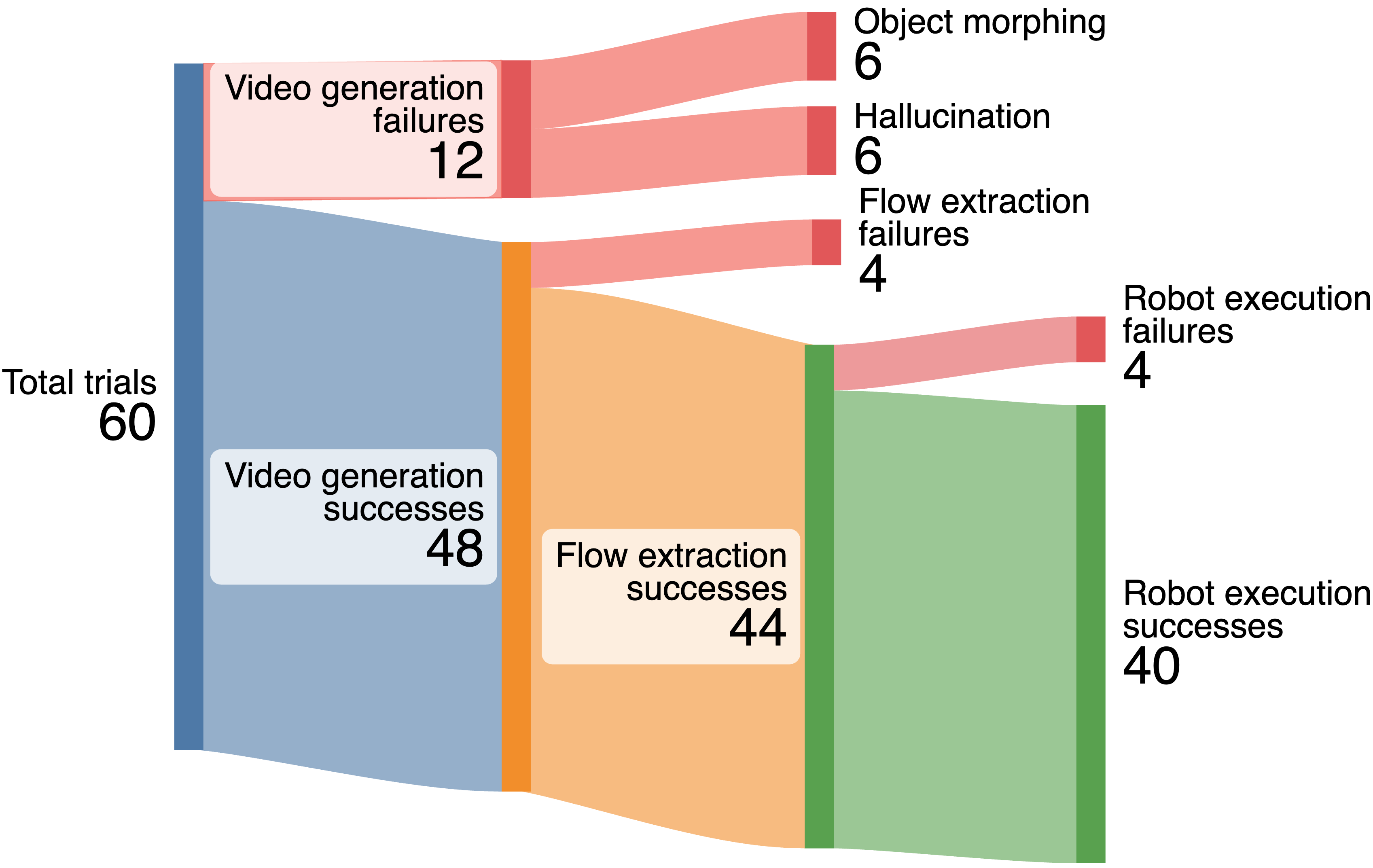

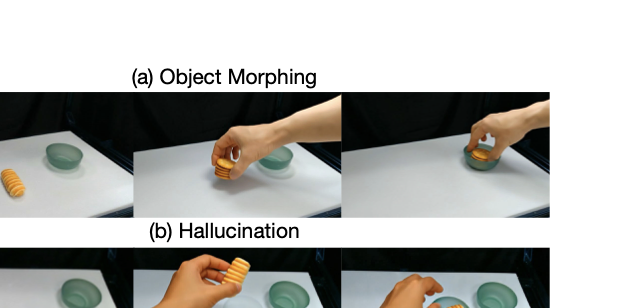

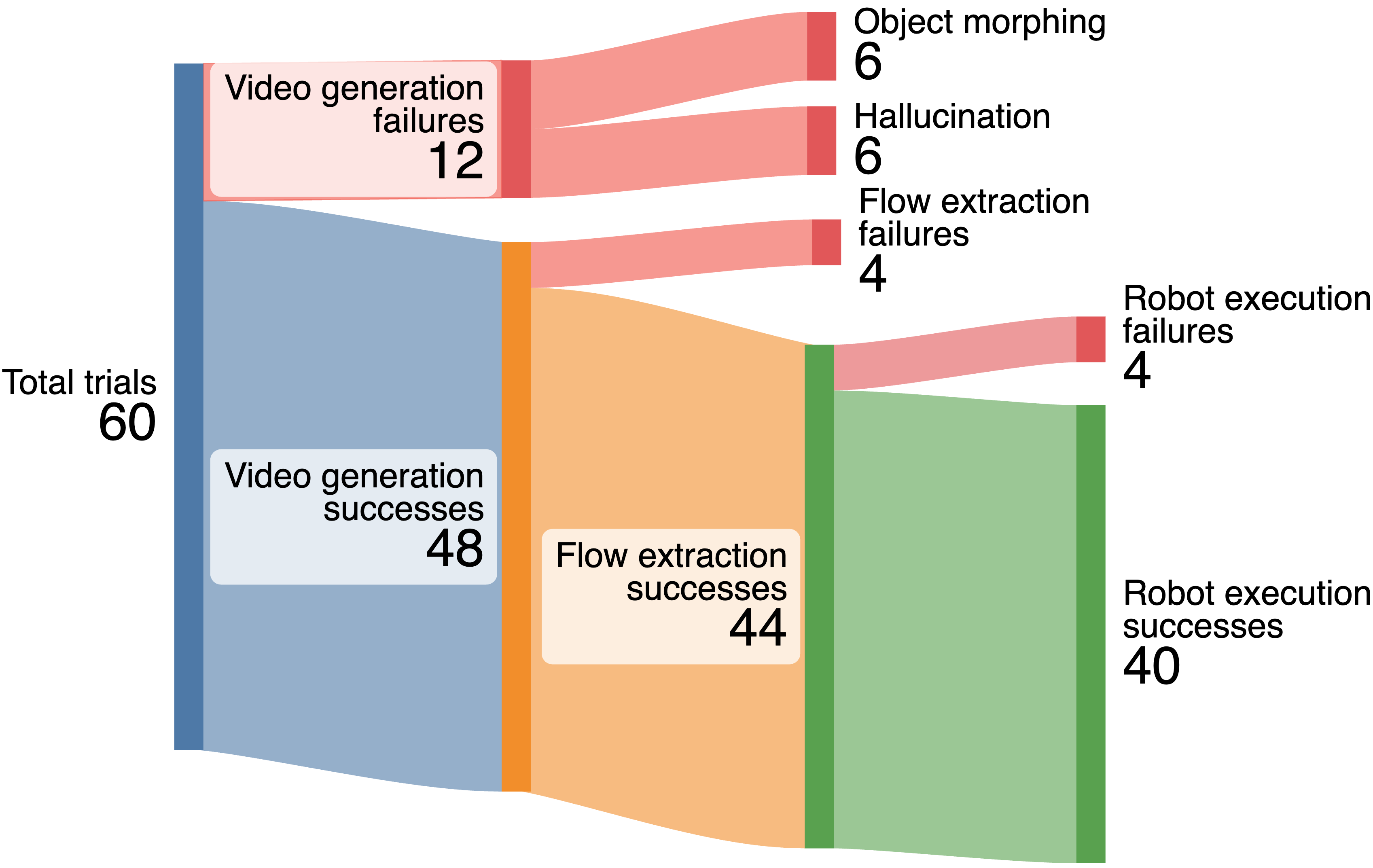

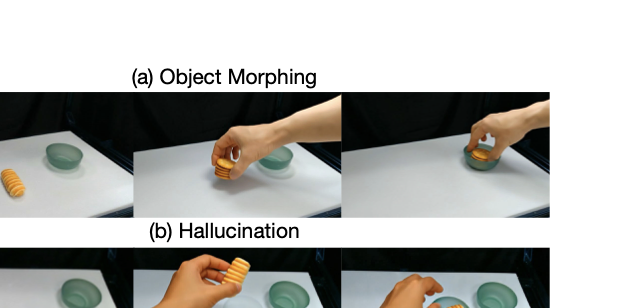

For all 60 trials of Dream2Flow executed in the real world, we provide a breakdown of failures in Fig. 6. In the 12 video generation failures, for half the time, the generated video either morphs an object in an implausible way or hallucinates new objects, causing tracking to unreasonably fail or making the robot move an object to an incorrect 3D location. The four flow extraction failures occurred because of severe rotations or objects temporarily going out of view of the camera, leading to tracks with no visibility in the end. The four robot execution failures occurred in the Bowl Covering task, where the robot either did not grasp at the correct point or did not move enough.

How does Dream2Flow perform compared to alternative interfaces?

For the three tasks in the real world, we consider the following alternative interfaces related to extracting object trajectories from videos:

| Task | AVDC | RIGVID | Dream2Flow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bread in Bowl | 7/10 | 6/10 | 8/10 |

| Open Oven | 0/10 | 6/10 | 8/10 |

| Cover Bowl | 2/10 | 1/10 | 3/10 |

Comparisons of intermediate representations on real robot. Dream2Flow outperforms AVDC and RIGVID across three tasks by following 3D object flow rather than rigid transforms alone.

AVDC

AVDC leverages generated videos by computing dense optical flow between frames to track points on a rigid object. Then, using the initial depth and the point correspondences, it solves for a sequence of rigid transforms of the relevant object, allowing for trajectory playback after a grasp has occurred. In our implementation, we utilize the video depth corresponding to the tracks from the optical flow, and optimize for rigid transforms relative to the initial frame, as we empirically found that to be less noisy than the original optimization procedure.

RIGVID

RIGVID uses 6D object pose tracking to generate a rigid object trajectory from a generated video. Since it is ill-defined to have such a pose for deformable objects, we do not use a 6D pose tracker, but instead adapt their approach by solving for a rigid pose transformation between the initial 3D points and visible 3D points from our 3D Object Flow computation in the same manner as AVDC.

We present the results in Table 1. While AVDC does a reasonable job at tracking the bread, the dense optical flow does not keep up with the motion of the oven, resulting in insufficient motion. Under certain circumstances, there are only a few visible points for RIGVID and AVDC, making transform estimation noisy. Attempting to follow the noisy transform trajectories leads to execution failures or optimization instability. Dream2Flow is less affected by this issue, because there is typically not a heavy cost when most of the points are occluded, allowing the planned end-effector poses to smoothly move between areas of high point visibility. The Cover Bowl task remains a challenge for AVDC and RIGVID, as in addition to video generation and tracking failures, the transform estimates are incorrect since the points are now on a deformable object.

How effective is 3D object flow as a reward for learning sensimotor policies?

The 3D object flow extracted by Dream2Flow can be used in an RL reward for training policies across different embodiments. We evaluate SAC policies trained using handcrafted object state reward from Robosuite and 3D object flow rewards on a Franka Panda, a Spot with floating base, and a GR1 with the right arm only across 100 random door positions, and report the results in Table 2 with corresponding episode visualizations in Figure 5. The policies trained with the object state and 3D object flow reward have comparable performance across all the embodiments. The learned strategies are different between the embodiments, as the Spot is able to move its base for better reachability and kinematic range, and the GR1 uses the area between the fingers and palm for pulling the door as opposed to individual fingers for better stability.

| Reward Type | Franka | Spot | GR1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Object State | 99/100 | 99/100 | 96/100 |

| 3D Object Flow | 100/100 | 100/100 | 94/100 |

Comparison of policies trained using different rewards. The policies trained using the 3D object flow reward perform comparably to those trained with the object state reward across different embodiments.

style="width:96.0%" />

style="width:96.0%" />

How does the choice of video model affect Dream2Flow in simulation and in real-world tasks?

| Video Generation Model | Push-T | Open Oven |

|---|---|---|

| Wan2.1 | 52/100 | 2/10 |

| Kling 2.1 | 31/100 | 4/10 |

| Veo 3 | - | 8/10 |

Effect of video generator. Veo 3 excels on real-world domains such as “Open Oven”, while Wan 2.1 performs better on simulated domains such as “Push-T”.

To evaluate how well different video generation models capture physically plausible object trajectories, we run Dream2Flow on the simulated Push-T task and the real Open Oven task using three models: Wan2.1 , Kling 2.1, and Veo 3 . The results are shown in Table 3. Note that there are no results for Veo 3 on Push-T because at the time of evaluation, Veo 3 did not support prompting with a goal image.

For the Push-T task, Kling 2.1 had more videos that had substantial morphing, throwing off the tracking, resulting in more downstream failures. For the Open Oven task, Wan2.1 tends to produce more videos with substantial camera motion, which violates the still camera assumption. Additionally, both Kling 2.1 and Wan2.1 produce videos where the direction of articulation is incorrect, such as revolving around the wrong axis, leading to far more failures than Veo 3.

How does the choice of dynamics model affect the performance of Dream2Flow?

| Dynamics Model Type | Success Rate | |

|---|---|---|

| Pose | 12/100 | |

| Heuristic | 17/100 | |

| Particle | 52/100 |

Dynamics model ablation. Particle dynamics substantially outperform pose and heuristic models, highlighting the importance of per-point predictions.

For the Push-T task, we compare the effect of different dynamics models used for planning. In addition to the particle-based dynamics model, we consider another learned dynamics model which takes in the block pose and push skill parameters and predicts the delta pose of the T-block, trained on the same data as the particle based dynamics model, as well as a heuristic dynamics model, which translates the points of the T-block in the direction and amount of the push without any rotation. We present the results in Table 4, and find that the particle representation for this dynamics model is crucial to ensure success, as despite having the same 3D object flow guidance, the pose and heuristic based dynamics models could not sufficiently account for the rotation needed.

Conclusion

We presented Dream2Flow, a simple, general interface that turns text-conditioned video predictions into executable robotic actions by reconstructing and tracking 3D object flow. This decouples what should happen in the world (task-relevant object motion and state change) from how a particular embodiment realizes it under kinematic, dynamic, and morphology constraints. Built entirely from off-the-shelf video generation and perception tools, Dream2Flow solves open-world manipulation tasks in simulation and on real robots across rigid, articulated, deformable, and granular objects using only RGB-D observations and language, without task-specific demonstrations. Experiments show consistent gains over trajectory baselines derived from dense optical flow or rigid pose transforms, robustness to variations in instances, backgrounds, and viewpoints, and the importance of both the upstream video model and downstream dynamics choice (with particle dynamics proving most reliable). A failure analysis highlights current bottlenecks, such as video artifacts (morphing, hallucinations), occlusion-induced tracking dropouts, and grasp selection mismatches as concrete directions for improvement. Overall, our results indicate that 3D object flow is a scalable bridge from open-ended video generation to robot control in unstructured environments.

Acknowledgments

This work is in part supported by the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI), the Schmidt Futures Senior Fellows grant, ONR MURI N00014-21-1-2801, ONR MURI N00014-22-1-2740.

Video Generation Prompts

For all real world tasks, the prompt to each video generation model consists of the initial RGB observation from one camera, as well as a language instruction of the form:

$`<`$TASK$`>`$ by one hand. The camera holds a still pose, not zooming in or out.

Values of <TASK>:

-

Put Bread in Bowl: The bread is grabbed and placed into the green bowl

-

Open Oven: The toaster oven is opened

-

Cover Bowl: The scarf is lifted by a corner and directly dragged over the blue bowl in one smooth motion without flinging the cloth or any dynamic / fast motions

-

Pull Out Chair: The chair is pulled out straight from under the table to the right by grabbing the middle

-

Open Drawer: The partially opened drawer is opened all the way out

-

Sweep Pasta: The brush with a green handle moves left to right to push the pasta into the compost bin

-

Recycle Can: The can is grabbed and dropped into the recycling bin

For the robustness evaluations, the word “bread” is replaced with “donut” or “long piece of bread” for the different object instances, but otherwise the prompt remains the same.

Since Dream2Flow leverages the position of a hand in the video to help select the grasp on the object, the “by one hand” phrase must be included. Additionally, “the camera holds a still pose” must be included to increase the probability that the generated videos do not have substantial camera motion, as the depth estimation pipeline assumes a still camera.

The T-shaped block slides and rotates smoothly to the center of the wooden platform.

style="width:96.0%" />

style="width:96.0%" />

For Push-T, since the task success requires accurate positions and to provide a better hint as to where the T block should go, we also provide a goal image of the T-block, as shown in Figure 7. At the time of evaluation, Veo 3 did not have the ability to take in an end frame, and hence was not considered for Push-T experiments.

The door opens all the way by itself to the right. The camera holds a still pose, not zooming in or out.

The Open Door task prompt does not include a hand to perform the action as it is in a simulated environment.

All prompts discussed in this section are identical for each video generation model evaluated. For Kling 2.1, a relevance value of 0.7 and a negative prompt of “fast motion, morphing, camera motion” are added.

Particle Dynamics Model

style="width:90.0%" />

style="width:90.0%" />

The particle dynamics model used in the Push-T task takes as input feature-augmented particles $`\Tilde{x}_t \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times 14}`$, consisting of the position, RGB value, normal vector, and push parameters and produces $`\Delta \hat{x}_{t+1}`$, the delta of positions of each point for the next timestep, as shown in Figure 8. The architecture of the particle dynamics model is a small Point Transformer V3 backbone surrounded by MLPs to project between the desired input and output sizes.

To get the input set of particles from the scene, there are 4 virtual cameras around the workspace, whose RGB-D observations are combined into a single point cloud. Then, points outside of the bounds of the wooden platform that the T-shaped block is on are discarded. Finally, this point cloud is voxel downsampled by randomly keeping only 1 particle per each 1.5cm sided cube. The same push parameter is appended to each particle’s features.

To train the particle dynamics model, we collect 500 transitions of random pushing actions. In this setting, we track particle positions before and after the push by using all objects’ poses from the simulator for efficiency, but in practice this can also be tracked with CoTrackerV3 and depth.

Push-T Planning Details

To optimize the particle trajectory following cost with the learned particle based dynamics model, Dream2Flow replans after every single push with random shooting until the T-block is within the specified tolerance to the goal or a maximum number of pushes have been executed. In this setting, at each replanning step, $`r`$ push skill parameters are randomly sampled such that all pushes will make contact with the object of interest at different points and directions. Then, Dream2Flow selects the push skill parameter out of those $`r`$ ones that has the least cost according to the predicted particle positions from the dynamics model with respect to a subgoal of particle positions (may not necessarily be the final goal position). While the T-block is being pushed, Dream2Flow uses the online version of CoTrackerV3 to track its motion, and once the push is completed, the tracked points are lifted into 3D, forming the updated particles of the T-block. We find that while parts of the T-block may be occluded during a pushing action, CoTrackerV3 tends to recover visibility of previously occluded points when the gripper lifts up.

Since Dream2Flow tracks particles for the T-block while the particle dynamics model takes in downsampled particles of the entire scene, Dream2Flow performs nearest neighbor matching to find correspondences between the currently tracked particles and the feature-augmented particles which are the input to the dynamics model. With these correspondences, and the predicted delta positions of these corresponding particles, Dream2Flow computes the predicted particle positions of the T-block as $`\hat{x}_{t+1} = \hat{x}_{t} + \Delta \hat{x}_{t+1}`$.

For determining which timestep from the video should be used in the cost function as a subgoal, Dream2Flow first finds the timestep $`t^{\star}`$ where the tracked particles are closest to the particles in the 3D object flow, as a single push can encompass the motion of many timesteps. Dream2Flow then chooses the particles from the timestep $`\min(t^{\star} + L, t_{\text{end}})`$ as the next subgoal for planning, where L is a fixed look ahead time amount, and $`t_{\text{end}}`$ is the final timestep of the video. In our experiments, we used $`L=20`$. We choose to use intermediate subgoals to be the target for random shooting as opposed to only the final particle positions of the T-block, as for cases involving substantial rotation, only having the final positions can result in the T-block have small translation error but large rotation error, eventually lead to timeouts.

Grasp Selection

style="width:90.0%" />

style="width:90.0%" />

Dream2Flow uses AnyGrasp to propose a set of up to 40 top-down grasps after applying the mask to the object of interest. Up to 20 grasps come from a point cloud in the coordinate frame of the camera, and another 20 grasps come from transforming those points into the coordinate frame of a virtual camera looking straight down in the center of the workspace. We added this addition virtual camera so that some more vertical grasps could be proposed.

While for rigid objects consisting of one part, such as a piece of bread, it is typically fine to grasp at any stable position, for articulated objects, the part that moves needs to be grasped instead. To perform grasp selection in such cases, we exploit video generation models’ ability to synthesize plausible hand-object interactions, typically where the hand first grabs the relevant part of the object and then proceeds to move it. Dream2Flow uses HaMer to detect the position of the hand, and in particular the thumb. If the predicted thumb position comes within 2cm of a proposed grasp, then such a grasp at the earliest timestep is chosen. An example of grasp selection with this method is shown in Figure 9.

It is possible that there are no such grasps detected, either because the grasp planner proposes grasps that are not near the hand in the video or the detections from HaMer are not accurate enough. In such cases, Dream2Flow defaults to a heuristic of selecting the closest grasp to the points on the movable part of the rigid object (obtaining points on the movable part is described in the next section).

Movable Part Flow Filtering for Rigid-Grasp Dynamics Model

style="width:99.0%" />

style="width:99.0%" />

Since the rigid-grasp dynamics model assumes that points that are grasped move with the end-effector, it is necessary to identify what points are part of the movable object. To determine this, we employ the heuristic that individual flows that move at least 1 pixel on average per timestep are part of the movable flow. We empirically chose the 1 pixel threshold, as we noticed that points tracked on the stationary parts of articulated objects such as the oven had low averages of how many pixels they moved.

For the 2D tracks associated with the movable part, it may be possible that for certain intermediate frames they are 1 pixel off, making the individual tracks belong to the background or floor when lifted into 3D, causing part of the 3D object flow to be dramatically incorrect, leading to downstream execution failures (such as trying to push the toaster oven’s door in the direction of the hinge). To remedy this issue, we utilize SAM 2 with positive point prompts in the initial frame for the movable part and negative point prompts for the non-movable part, and use the part mask over each consecutive frame to constrain the 2D flow (if any tracked point is outside of the mask, it is considered to be invalid).

Real World Planning Details

The optimization problem with a rigid-grasp assumption in the real world follows the same formulation as in Sec. 3.1, where we optimize robot joint angles $`\mathbf{q} \in \mathbb{R}^7`$ to minimize:

\begin{equation}

\sum_{t=0}^{H-1} \lambda_{\text{task}}\big(\hat{x}^{\text{obj}}_t, \tilde{P}_t\big) + \lambda_{\text{control}}(\hat{x}_t, u_t)

\end{equation}The control cost $`\lambda_{\text{control}}(\hat{x}_t, u_t)`$ is expanded into three components:

\begin{equation}

\lambda_{\text{control}}(\hat{x}_t, u_t) = w_r \mathcal{C}_r(\mathbf{q}_t) + w_s \mathcal{C}_s(\mathbf{q}_t, \mathbf{q}_{t-1}) + w_m \mathcal{C}_m(\mathbf{q}_t)

\end{equation}where:

-

$`\mathcal{C}_r(\mathbf{q}_t)`$: Reachability cost penalizing joint configurations outside the robot’s workspace

-

$`\mathcal{C}_s(\mathbf{q}_t, \mathbf{q}_{t-1})`$: Pose smoothness cost measuring the difference between consecutive end-effector poses after running forward kinematics

-

$`\mathcal{C}_m(\mathbf{q}_t)`$: Manipulability cost encouraging configurations with good manipulability

The weight parameters are set to $`w_r = 100`$, $`w_s = 1`$, and $`w_m = 0.01`$ to encourage the robot to make smooth motions within its joint limits. The task cost $`\lambda_{\text{task}}`$ uses a weight of $`w_f = 10`$ and follows the same formulation as in Sec. 3.1. The optimized end-effector poses after running forward kinematics are then fit with a B-spline and sampled such that each sampled pose is at least 1cm away from the previous and next pose and/or has a rotation difference of at least 20 degrees. To execute this planned trajectory, we use the IK solver from PyBullet to get target joint angles and then a joint impedance controller from Deoxys commands the Franka to reach those positions.

In-the-Wild Tasks

For In-the-Wild tasks, we consider:

Pull Out Chair

In the Pull Out Chair task, a black rolling chair is placed underneath a table. A trial is considered a success if the chair is moved at least 5cm horizontally from its initial position. The reason for the limited motion requirement is that in certain configurations, it is difficult for the Franka robot to push the chair.

Open Drawer

The Open Drawer task involves opening a partially opened drawer out to at least 90% of its full possible extension.

Sweep Pasta

In the Sweep Pasta task, there is a brush with a green handle placed against a wooden support structure, along with four pieces of dried pasta next to a compost bin. The objective is for the robot to grasp the handle of the brush and use the brush to push the pasta into the compost bin. If all pieces of pasta are inside of the compost bin, it is considered a success.

Recycle Can

In the Recycle Can task, an aluminum can is placed in between a recycling and trash bin while upright. A trial is successful if the can is inside of the recycling bin.

See Fig. 10 for rollouts for each of these in-the-wild tasks.

Open Door Reinforcement Learning Details

For the Open Door task, we utilize Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) to train sensorimotor policies across three different embodiments: a Franka Panda, a Spot robot, and a GR1 humanoid arm. The policies are trained to follow the 3D object flow extracted from generated videos, which serves as a reward signal.

Hyperparameters

The hyperparameters used for SAC training are detailed in Table 5. These values were consistent across all reward types and embodiments with exception of the GR1, which uses 10000 training iterations due to the larger action space.

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Learning rate | $`3 \times 10^{-4}`$ |

| Discount factor ($`\gamma`$) | 0.99 |

| Batch size | 256 |

| Buffer size | $`10^6`$ |

| Target update rate ($`\tau`$) | 0.005 |

| Target network update freq | 1 |

| Hidden layers | 2 |

| Hidden units per layer | 256 |

| Training iterations | 5000 |

| Episode horizon | 500 |

SAC Hyperparameters for Open Door Task.

Reward Functions

We compare policies trained with two different reward formulations: a handcrafted object state reward and a 3D object flow reward.

Object State Reward: The handcrafted reward $`R_{\text{state}}`$ consists of a reaching component $`r_{\text{reach}}`$ and a handle rotation component $`r_{\text{rot}}`$:

\begin{equation}

r_{\text{reach}} = 0.25 \cdot (1 - \tanh(10 \cdot d_{\text{gripper, handle}}))

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

r_{\text{rot}} = \text{clip}\left(0.25 \cdot \frac{|\theta_{\text{handle}}|}{0.5\pi}, -0.25, 0.25\right)

\end{equation}where $`d_{\text{gripper, handle}}`$ is the L2 distance between the robot’s end-effector and the door handle, and $`\theta_{\text{handle}}`$ is the rotation angle of the handle. The total reward is $`r_{\text{reach}} + r_{\text{rot}}`$, unless the door hinge angle $`\theta_{\text{hinge}} > 0.3`$ radians, in which case a completion reward of 1.0 is returned.

3D Object Flow Reward: The 3D object flow reward $`R_{\text{flow}}`$ leverages the reference trajectory $`P_{1:T}`$ extracted from the video. It consists of a particle tracking term $`r_{\text{particle}}`$ and an end-effector alignment term $`r_{\text{ee}}`$:

\begin{equation}

r_{\text{particle}} = 0.75 \cdot \frac{t^\star}{t_{\text{end}}}

\end{equation}where $`t^\star`$ is the index of the closest timestep in the reference trajectory $`P_{1:T}`$ based on the current object particle positions $`\hat{x}_t^{\text{obj}}`$ in the door frame:

\begin{equation}

t^\star = \mathop{\mathrm{argmin}}_{t \in \{1 \dots t_{\text{end}}\}} \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \|\hat{x}_t^{\text{obj}}[i] - P_t[i]\|_2

\end{equation}The end-effector term $`r_{\text{ee}}`$ encourages the robot to stay near the object particles:

\begin{equation}

r_{\text{ee}} = 0.25 \cdot (1 - \tanh(10 \cdot \|ee_{\text{door}} - \bar{x}\|_2))

\end{equation}where $`ee_{\text{door}}`$ is the end-effector position in the door body frame and $`\bar{x} = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \hat{x}_t^{\text{obj}}[i]`$ is the mean position of the object particles. The total reward is $`R_{\text{flow}} = r_{\text{particle}} + r_{\text{ee}}`$.

Instead of tracking the mean particle position with CoTrackerV3, we proceed to use a simpler approach of transforming the initial particles as the door angle changes for better computation efficiency. We thus consider the door joint angle to be a part of the state $`x_t`$.

Video Generation Failures

style="width:96.0%" />

style="width:96.0%" />

From the generated videos, we observe that there are two common failure modes: morphing and hallucination. Object morphing occurs when an existing object in the scene dramatically changes shape to something else, such as another object or an object with significantly different geometric properties than what it should be. Hallucination occurs when a new object (previously non-existent) appears in the scene. We show examples of morphing and hallucination for the Put Bread task in Fig. 11.

Limitations

Dream2Flow has several limitations. First, it relies on a rigid-grasp assumption for real world manipulation, limiting the types of tasks that can be performed. While this work shows that a particle dynamics model can be used for other types of tasks such as non-prehensile pushing, training and scaling a particle dynamics model for the real world is non-trivial and can be considered for future work. Another limitation is that the total processing time to get 3D object flow depending on the video generation model is between 3 and 11 minutes, which limits its usability, with the main bottleneck being the video generation. Since Dream2Flow relies upon one angle in a generated video, it cannot handle heavy occlusions gracefully, such as when the human hand covers the majority of a small object. Future work may consider methods which can deal with such occlusions better, such as 3D point trackers or full 4D representations.

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)