Context-aware LLM-based AI Agents for Human-centered Energy Management Systems in Smart Buildings

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Context-aware LLM-based AI Agents for Human-centered Energy Management Systems in Smart Buildings- ArXiv ID: 2512.25055

- Date: 2025-12-31

- Authors: Tianzhi He, Farrokh Jazizadeh

📝 Abstract

This study presents a conceptual framework and a prototype assessment for Large Language Model (LLM)-based Building Energy Management System (BEMS) AI agents to facilitate context-aware energy management in smart buildings through natural language interaction. The proposed framework comprises three modules: perception (sensing), central control (brain), and action (actuation and user interaction), forming a closed feedback loop that captures, analyzes, and interprets energy data to respond intelligently to user queries and manage connected appliances. By leveraging the autonomous data analytics capabilities of LLMs, the BEMS AI agent seeks to offer context-aware insights into energy consumption, cost prediction, and device scheduling, thereby addressing limitations in existing energy management systems. The prototype's performance was evaluated using 120 user queries across four distinct real-world residential energy datasets and different evaluation metrics, including latency, functionality, capability, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness. The generalizability of the framework was demonstrated using ANOVA tests. The results revealed promising performance, measured by response accuracy in device control (86%), memory-related tasks (97%), scheduling and automation (74%), and energy analysis (77%), while more complex cost estimation tasks highlighted areas for improvement with an accuracy of 49%. This benchmarking study moves toward formalizing the assessment of LLM-based BEMS AI agents and identifying future research directions, emphasizing the trade-off between response accuracy and computational efficiency.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **Importance of LLMs**: Large Language Models (LLMs) are crucial in improving interactions between Building Energy Management Systems (BEMS) and humans, acting like the brain that thinks for the building. 2. **Enhanced User Interfaces**: LLM-based AI agents can provide insights and advice to help users achieve their energy management goals, much like a smart assistant tailoring its actions based on user needs. 3. **Context Awareness**: LLMs understand user intent, gather necessary information, and assist in achieving energy management objectives, similar to a building that adjusts itself according to time and circumstances.📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

Large Language Model ,Building Energy Management System ,AI Agents ,Human-Building Interaction

Introduction

Buildings account for approximately 30% of global energy consumption , and are therefore critical in achieving energy efficiency. Targeted mitigation strategies, such as adaptive and human-centered control strategies , smart grid operations , Internet of Energy (IoE) adoption , and fault detection frameworks , combined with reactive and proactive user interactions, can facilitate efficient energy use in buildings . To this end, Building Energy Management Systems (BEMS) have been developed and extensively studied . These systems could optimize energy efficiency and support tasks such as human-centered operations, demand response, consumption and cost monitoring, and anomaly detection . Residential BEMS alternatives serve as intelligent control centers in IoT-enabled smart homes to coordinate meters, sensors, actuators, smart appliances, and hubs. BEMS’ design concepts center around offering user-friendly interfaces for end users to manage energy use and achieve comfort and efficiency goals . In different contexts, users can rely on different interaction modalities. Recent advances in AI-powered technologies, especially those involving natural language processing, have improved user-BEMS interfaces. A prominent example is the use of smart speakers with virtual assistants, which serve as intelligent hubs for both user engagement and smart appliance control .

Previous studies have broadly investigated the applications and architectures of BEMS with various objectives, such as enhancing energy efficiency, reducing operational cost, load profiling, and improving user comfort . However, there have been challenges associated with their practical implementation in meeting such goals due to system complexities that may present a steep learning curve for users . These challenges can be observed in both commercial and residential settings, although they may be more pronounced in the latter due to users’ varying levels of technical knowledge. Users may lack awareness of all system features, such as the availability and functionality of smart sensors and devices, or the optimal ways to use those systems, and might have limited ability to use them effectively, given the lack of intuitive interfaces. Moreover, users’ goals may vary widely, from reducing energy cost to enhancing comfort or optimizing the integration of distributed energy resources . However, users are often unaware of their energy use and generation patterns, and the relationship between those patterns and their behavior and actions, which limits the extent to which BEMS capabilities can be leveraged to improve energy efficiency.

Intuitive user interfaces could be leveraged to partially address these complexities by facilitating user-technology interactions and guiding users in leveraging the system’s capabilities toward achieving their objectives. However, given the varied user objectives, the design of such interfaces calls for flexibility. Conventional interfaces have commonly struggled to adapt to these varied objectives, often failing to accommodate open-ended and general user goals or support complex decision-making processes . In recent years, AI-powered technologies have emerged with the aim of facilitating user interactions through natural language interfaces. However, they often provide only basic support . For instance, as noted, voice-enabled smart speakers have become prevalent but are commonly limited to answering simple queries posed by users . The emergence of large language models (LLMs) has created opportunities to address those limitations. However, even when these interfaces are equipped with more advanced technologies, such as LLMs to understand and respond to user queries, their responses remain generic, whereas effective energy management, particularly when aligned with heterogeneous user objectives, requires awareness of building-specific hardware configurations, operational data patterns, and system attributes . To address these limitations, our research investigates how LLM-based AI agents can be designed and configured to go beyond AI agents with strong conversation capabilities and function as ambient AI agents that are capable of providing context-aware support for users’ goals. Context-awareness pertains to AI agent ability to understand the specifics of their operational environments, including energy consumption and generation patterns, and the operational states of appliances.

LLM-based agentic frameworks, exemplified by platforms such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT series and Google’s Gemini series, may offer potential solutions to the aforementioned challenges. Trained on large-scale textual datasets, LLMs learn language patterns and contextual relationships to understand, generate, and interact in human language . Researchers have successfully integrated LLMs into AI agents to enable autonomous reasoning steps (e.g., Chain-of-Thought prompting) that approximate certain aspects of human problem-solving and decision-making processes . With unified frameworks comprising key modules, such as profile (instructions for AI agents), memory, planning, and action or perception, cognition (“brain”), and action , different LLM-based AI agents have been designed to suit various tasks and applications. These include simulation agents in social science research , tool-augmented agents in natural sciences , and embodied agents for industrial automation and robotics . The integration of LLM-based ambient AI agents, capable of observing, perceiving, analyzing, and adjusting a BEMS’ environment, has the potential to enable more flexible, convenient, and intuitive user interaction mechanisms between users and BEMS. Such mechanisms could, in turn, be leveraged to enhance user awareness and engagement in reactive and proactive building energy management systems and control applications . Our vision centers around a BEMS AI Agent that can communicate with users in natural language, independently and autonomously analyze building data to identify context-aware responses to users’ queries, and provide feedback and actions to help users achieve their energy management goals. To this end, our study (1) investigates a conceptual framework for LLM-based AI Agents, specifically tailored for context-aware smart building energy management, (2) develops a prototype of this framework for smart home energy management, and (3) evaluates its feasibility (in terms of effectiveness and latency), as well as generalizability in addressing several categories of user queries with varied complexities. This involved constructing a query benchmark and assessing how reliably the AI Agent can respond across different building conditions, providing a clear measure of its robustness and adaptability. We have sought to define the fundamental components, functionalities, and capabilities required for such a framework. For developing and evaluating our framework prototype, we utilized real-world smart residential building configurations and energy data from different households.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the research background and related studies. Section 3 outlines the proposed framework, detailing the designed prototype, and the evaluation methods for the LLM-based BEMS AI Agent. The findings from our evaluations of the prototype on residential building energy datasets are detailed in Section 4. This is followed by a discussion of the results and their implications for future work in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes by presenting the findings and contributions of this study.

Research Background

Building Energy Management Systems (BEMS) and Interfaces

Building Energy Management Systems (BEMS) have evolved alongside advances in system design, information transmission technologies, and optimization algorithms over the past decade . In practice, a BEMS can be viewed as a modular system that brings together four major components: (1) sensors and meters that track environmental conditions and energy consumption, (2) communication networks and protocol translators (e.g., Zigbee), (3) data storage, forecasting tools, and optimization modules for environmental and energy analysis, and (4) control layers with user interfaces that connect to HVAC, lighting, energy information systems, and other controllable devices . This layered architecture enables buildings to monitor and manage energy consumption, aligning efficiency with operational and comfort constraints . From a life cycle perspective, BEMS also supports operation and maintenance (O&M) workflows in which anomaly detection, diagnostics, and performance tracking are increasingly data-driven . Effective energy management depends on rich, heterogeneous inputs that feed analysis and control modules, including historical energy use, the use of distributed energy resources, thermal dynamics, occupancy and schedules, operational constraints, and appliance controllability . In residential contexts, BEMS commonly emphasize thermostatic control and HVAC scheduling, time of use shifting to reduce peak demand costs, and coordination of different resources such as rooftop photovoltaic (PV) systems and battery storage . Increasingly, these approaches are being integrated with BEMS interfaces such as smart home energy hubs and appliance‐level control, allowing households to actively participate in energy management while maintaining comfort and minimizing operational costs .

BEMS interfaces have traditionally been designed around dashboard-oriented front ends that provide system alarms, time‐series trends, and setpoint controls to users. These visual dashboards are often optimized for expert users and typically offer limited interactivity or explanation beyond data display. In recent years, however, a shift has begun toward more occupant-centered interfaces that emphasize engagement, feedback, and actionable insights. Modular building energy systems demonstrate that embedding context-aware feedback, goal setting, and suggestions, can lead to energy efficiency while preserving comfort and productivity . For instance, Francisco et al. integrated spatial, color‐coded Building Information Modeling (BIM) visualizations into feedback systems to help occupants better interpret energy use and meaningfully engage with building operations . In residential contexts, Vassileva et al. evaluated how feedback devices (displays, dashboards) influence consumption when combined with contextual cues . While effective for monitoring and supervisory control, such interfaces have rarely supported natural language-based interactions with occupants or context-aware guidance for specific end uses . Meanwhile, users increasingly face a growing number of smart devices without a unifying, intelligible control layer for energy management . Occupants could benefit from an intelligent central coordinating assistant to organize appliances and personalize interactions .

Building on these observations, we summarize three major barriers for BEMS in residential settings. First, explainability: most front-end systems have limited capacity to communicate the rationale behind control decisions, which reduces system explainability and undermines users’ ability to understand and potentially trust the BEMS. User studies consistently report dissatisfaction with building‐level feedback alone, highlighting a need for appliance‐specific insights and actionable recommendations . Second, adaptivity: current interfaces rarely tailor their content to users’ contexts, preferences or literacy levels. Energy literacy differs greatly across stakeholders, including operators, facility managers, and everyday occupants . Standardized kW/kWh displays often do little to engage or educate, whereas alternative framings such as monetary cost, comfort impact, historical comparisons, or social norms have been shown to be more effective . Third, integration: the heterogeneity of devices and fragmented ecosystems often prevents BEMS from providing unified control and delivering a coherent user experience. Case studies of residential energy management emphasize the importance of converting technical results into user-friendly recommendations and continuous operational guidance, rather than presenting them as one-time reports . Collectively, previous studies indicate that the success of a building energy management system is determined not only by the quality of its optimization algorithms but also by how users interact with the system. Building on this foundation, our study conceptualizes the BEMS not only as a control stack but also as a human‐centered interface that must coordinate algorithms, devices, and users, an orientation that directly motivates the AI agent design presented in this study.

LLM-based AI Agents for Smart Buildings and BEMS

Large Language Models (LLMs) are foundation models trained to understand and generate human language, supporting tasks such as question answering, summarization, translation, and content generation . Beyond text, LLMs can integrate structured inputs and tool outputs, making them flexible for data retrieval, reasoning, and explanation . Recent studies frame LLMs as the “brains” of interactive AI agents that couple language understanding with external tools and actuators . Compared with rule-based agents, LLM-based AI agents can interpret vague intents, decompose tasks, call functions (e.g., data queries, simulations), and synthesize results into action plans or explanations . They have been explored in scientific discovery , software engineering , education , and the AEC domain , often serving as a reasoning-and-orchestration layer that translates user goals into tool calls. In the context of energy and buildings, these capabilities suggest a path to smart building interfaces that interact with users in natural language while grounding responses in energy information and operational constraints . Such interfaces can lower cognitive load, personalize feedback, and offer explanations of control choices . However, practical deployment must also address accuracy, latency, and cost, and combine LLMs with guardrails and domain tools to ensure reliable, auditable operation in building environments .

At the same time, the advancements of IoT devices have increased functionality but also complexity in smart environments . Users and operators frequently confront fragmented apps and rigid rules (e.g., If This Then That (IFTTT) conditional statements for automation) that struggle with nuanced intents and evolving contexts . LLM-based AI agents address this by performing contextual reasoning over sensor states, schedules, and user preferences, enabling fluent, natural interactions (e.g., “It feels stuffy in the room, can you fix it?”) and generating concrete actions such as adjusting airflow and setpoints . As LLMs can generalize from language alone, they reduce the need for exhaustive command templates and enable faster implementation across heterogeneous device ecosystems . Empirical studies lend strong support to these directions. For example, natural-language front ends have been shown to improve IoT platform usability when combined with semantic parsing and hierarchical planning . Similarly, datasets such as VISH expand the range of goal-oriented smart-home commands that agents can recognize and execute . More recent systems go a step further by translating informal or vague statements into actionable multi-step plans, enabling coordination across multiple devices and constraints .

LLM-based AI agents are also being adopted within BEMS, a domain historically reliant on manual or rule-based workflows and specialized interfaces . The AI agents align naturally into BEMS workflows, in which they can parse a user query, fetch historical data and constraints, evaluate scenarios, and present options and plans to users. By linking language understanding to data pipelines, agents can translate questions into analyses (e.g., “What drives last month’s peak?”), summarize anomalies, and recommend targeted actions such as thermostat setbacks, schedule tuning, or retrofit opportunities . Beyond conversational support, researchers report progress on LLM-enabled pipelines for load analysis, forecasting, and fault/anomaly detection , where statistical outputs are paired with narrative explanations that foster more effective interactions . These trends point toward a BEMS future in which optimization and interaction could co-exist within a single, conversational control interface. Several case studies illustrate the emerging applications. For example, Gamage et al. proposed a contextualized QA framework that uses ChatGPT to resolve ambiguous or incomplete user queries in energy management systems, streamlining occupant-system communication . Zhang et al. developed an automated, GPT-assisted data-mining workflow for building energy analysis and report 89.17% accuracy in identifying chiller-plant waste patterns over a year-long dataset . Jin et al. translated natural-language intents into optimization problems to align recommendations with user-specific energy preferences (e.g., EV charging, rooftop PV) . Ahn et al. embedded ChatGPT within an EnergyPlus-in-the-loop setup to coordinate HVAC control for comfort and CO2, achieving simulated savings of 16.8% . Taken together, previous studies suggest that LLM-based agents can make building data more interpretable, recommendations more actionable, and controls more transparent. By anchoring the AI agents in the BEMS pipeline reviewed in prior work and explicitly targeting current BEMS interface shortcomings, the goal of this study is to advance a practical pathway for an LLM-enabled, human-centered AI agent for energy management that is both accurate and effective in deployments.

Methodology

The methodology section describes the rationale behind the design of the conceptual framework, as well as the processes involved in the development of the prototype and its evaluation experiments using real-world data.

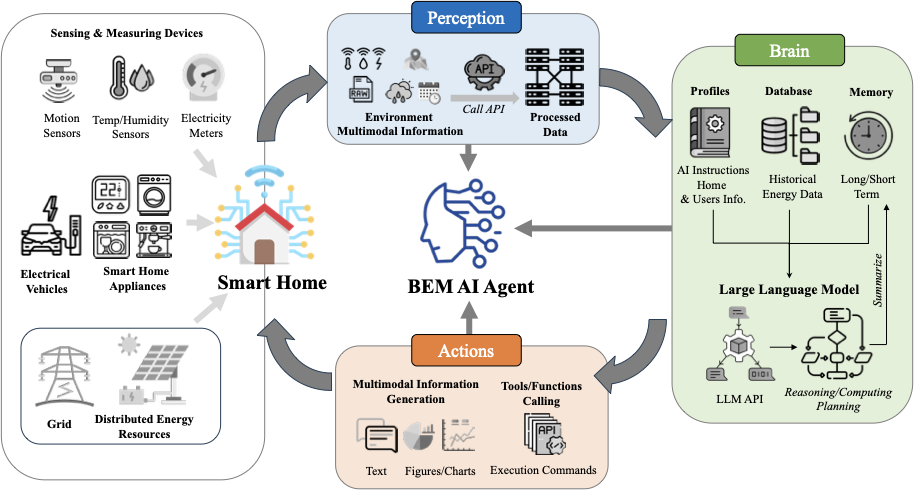

Conceptual Framework

Development and key components of LLM-based AI agents from previous studies form the fundamental structure of the proposed BEMS AI Agent. In prior research , LLM-based AI agents commonly consist of three major modules, each containing several key components. The central processor module, or “brain” of the AI agent, is the first and most vital module . Beyond the core LLM with its pretrained knowledge for reasoning and planning, the “brain” includes other key components, such as the system instructions and memory of the AI agent . System instructions of the LLM define the roles and tasks of AI agents, usually in the form of text-based prompts that instruct and guide the agent’s behavior . Memory, comprising both short-term and long-term memories, helps the agents understand context, accumulate experiences, and perform tasks more efficiently and accurately .

The second module is the perception module, which processes multiple modalities of data sources, such as textual, visual, audio, and other structured data . Functioning as the AI agent’s primary interface with the environment, this module helps the agent to extract relevant features from sensory inputs and support environment representation and informed decision-making . The third module, the Action module, is responsible for both traditional LLM-based actions, such as textual output, as well as expanded actions through external tool integration . Pretrained LLMs have inherent limitations, such as a lack of up-to-date knowledge and the propensity to generate hallucinated or factually inaccurate outputs and commands . To address these limitations, specialized external tools have been developed to expand the AI agent’s action space, utilizing supplementary resources and functions to accomplish intended outcomes .

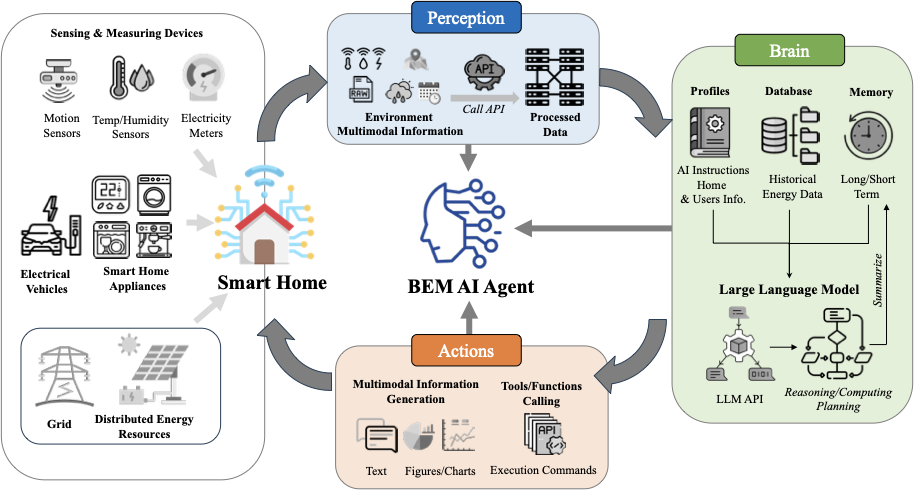

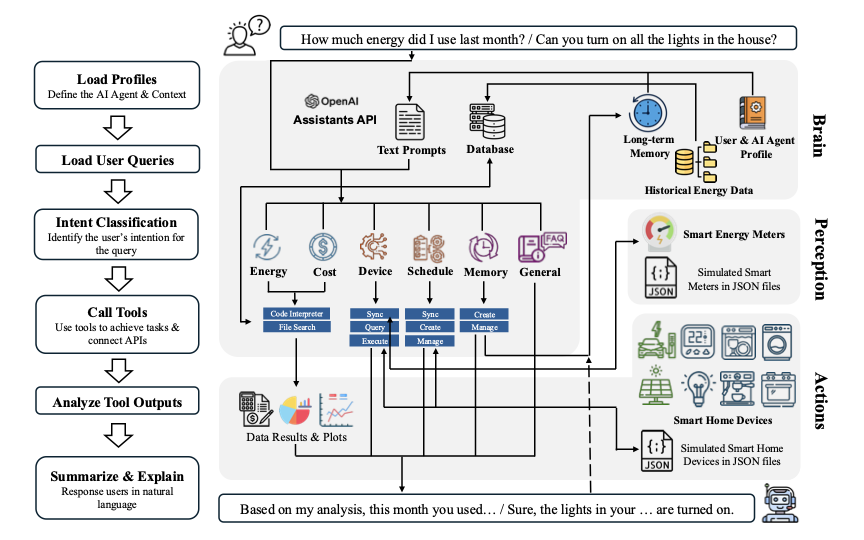

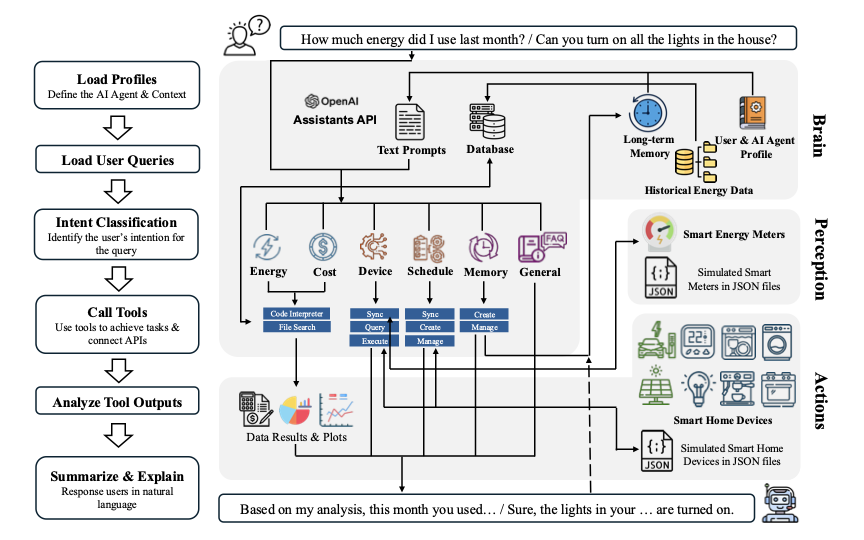

Drawing on these foundational modules and building on the established frameworks for Building Energy Management Systems (BEMS) and AI agents from prior research, we have introduced a conceptual framework for the LLM-based AI agent for human-centered building energy management system, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Perception Module

The perception module forms the sensory foundation of the AI agent, enabling it to acquire and preprocess multimodal data from both indoor and outdoor environments. It interfaces various sensors and devices, such as smart electricity meters (to measure both aggregate and appliance level energy use ), occupancy sensing systems, temperature and humidity sensors (either from a thermostat or from distributed nodes), indoor air quality (IAQ) sensors, wearable sensors, smart appliances, energy storage systems, and electric vehicles to collect contextual data critical for assessing energy usage, environmental conditions, and device states. Additional data streams, such as weather information, utility constraints, occupant location (indoor positioning of occupants), and calendar events, can also be gathered via specialized application programming interfaces (APIs) from third-party sensors and resources. These raw data are processed, structured, and relayed to the brain module to provide a comprehensive picture of the smart environment states either in real-time or as historical observations. Analogous to how sensory organs (e.g., eyes and ears) gather data from the environment and send it to the human brain for interpretation, the perception module of the ambient AI agent serves as the brain’s counterpart, integrating and interpreting data from various data streams to construct a coherent representation of the environment. It should be noted that not all environments are equipped with a full range of sensors and smart devices, and therefore, the ambient AI agent should be able to adapt and infer the state of the environment according to the available contextual configuration. Nonetheless, a standardized (ontology) representation of hardware configurations could facilitate uniform implementation of the perception module across different environments. However, the LLM capabilities could potentially be leveraged to facilitate the mapping between hardware configurations and data streams.

/>

/>

Brain Module

At the core of the AI agent is the brain module (i.e., central computational module), which functions as the primary computational layer responsible for coordinating the operations. It is responsible for multimodal data integration, reasoning, and interfacing with the external control layer for actuation. It leverages code generation and execution capabilities to synthesize contextual data and develop models, employs tools to activate memory retrieval, and manages computational processes to enable intelligent interactions and energy management. The core functionalities of LLM-based data analysis tools could enable agents to perform autonomous context-aware reasoning and continuous learning in dynamic environments.

Data and Memory: The processed multidimensional contextual data, such as the historical energy data, originating from the perception module, is stored and organized in the brain module’s database. The brain module also stores and utilizes other information, such as the AI Agent system instructions and user interaction records. The information storage in the brain module can be conceptually compared to human memory. Therefore, the brain module’s memory is divided into long-term and short-term categories. Long-term memory encodes user-defined preferences for devices/appliances usage and schedules, historic energy consumption patterns, history of user interactions, and other disturbances such as occupancy trends (if available). Short-term memory includes data related to transient states such as the real-time devices/appliance statuses, and the ongoing user interactions/conversations context. Technologies such as vector databases and their associated tools (e.g., Milvus and FAISS ) are commonly employed to support long-term semantic memory, enabling efficient similarity-based retrieval of historical user interactions, preferences, and contextual knowledge . In parallel, time-series databases (e.g., InfluxDB , TimescaleDB ) are widely used to store and query high-resolution historical building performance data, including energy consumption, device states, and environmental sensor readings. To provide a structured and machine-interpretable representation of building assets and their interrelationships, ontology-driven digital twinning approaches are also increasingly adopted. Standards and frameworks such as Brick Schema and BOT (Building Topology Ontology) enable semantic interoperability across heterogeneous building systems by formally modeling equipment, spaces, sensors, and their topological and semantic relationships. Overall, the brain module is not bound to a single implementation but can incorporate various data, and memory technologies, enabling extensibility and comparative evaluation in future work.

AI Agent’s Identity and Contextual Encoding: To provide the AI agent with contextual understanding, the brain module maintains a structured profile or system instructions that define the AI agent’s operational constraints, functional objectives, and user-specific requirements. This profile, stored in text format (or other structured formats such as JSON), encodes: User-defined constraints and preferences (e.g., thermal comfort preferences), building metadata (e.g., HVAC zoning configurations, energy sources and storage integration (as applicable), appliance specifications), and operational policies governing the AI agent’s decision framework in energy management. By embedding these parameters, the AI agent ensures that generated recommendations and control actions align with user needs and building-specific attributes.

Data-driven Reasoning and Control: The LLM interfaces with the memory and profile representations to process them and perform reasoning, computation for inference and predictive analytics, and control/actuation signal generation. Using its advanced language model, the AI agent integrates data from various sources to generate and run specialized data analysis. The AI agent utilizes historical trends, real-time sensor streams, and environmental parameters to execute data analysis to find patterns, create summary statistics, predict patterns and detect anomalies and guide the responses related to energy management strategies. To this end, it dynamically generates executable scripts for data analysis and rule-based automation. Processed insights are translated into actionable commands for the Action Module, which executes device-level adjustments, automated scheduling, and adaptive user guidance.

Action Module

The action module manages user interactions (both visual and conversational) and controls various smart devices and appliances to manage energy use and facilitate human-building interaction. It manages communication with users, generating multi-modal outputs such as text messages or notifications with energy suggestions, and visual representations of energy use patterns through various visualizations (such as figures, charts, and graphs) to help users better understand those patterns and identify areas for improvement. Beyond user engagement, the action module executes direct control over smart devices and appliances while managing distributed energy resources (DERs) through commands generated using the LLM’s tools and function-calling capabilities. This includes autonomous scheduling, dynamic load adjustments, and state-dependent configuration of devices such as HVAC systems, lighting, energy storage systems (batteries), and energy generation resources (e.g., photovoltaic arrays, if applicable). When enabled with additional functions, the system can also be used to optimize operations for improved energy efficiency and reduced operational costs.

In this conceptual framework, which consists of three fundamental modules, the AI agent and users interact within a feedback loop in an environment, creating an adaptive system that continually monitors and adjusts operations. Sensors collect environmental data, which the perception module processes and forwards to the brain module for analysis along with user input. The action module then communicates with users and implements decisions to adjust devices, with ongoing monitoring refining actions for energy efficiency and occupant comfort.

AI Agent Prototype Design

To assess the feasibility of the proposed LLM-based ambient AI Agent for energy management in buildings, we developed a prototype tailored for residential buildings. During development and testing, we focused primarily on the functionality and performance of the framework’s brain module, given that our primary objective was to examine the performance of LLM-based reasoning capabilities rather than the framework’s interfaces. As such, to represent the interfaces between the brain and the perception modules, we utilized existing building energy data (from real-world field studies) and simulated smart building monitoring at the aggregate and appliance levels. Likewise, we examined how the control signals from the brain module interface with the action module through simulated adjustments in the states of devices and appliances. The following subsections outline the internal structure of the brain module and how it interfaces with the other modules. To develop this prototype, we have adopted the OpenAI Assistants API.

/>

/>

Prototype’s perception module

As noted, the perception module is the sensory infrastructure of the AI agent, which is responsible for collecting and organizing multimodal contextual data. Considering that our objectives include the assessment of the feasibility of autonomous computational analyses by the brain module and the evaluation of their generalizability to different contexts, for the perception module, we adopted the sensor system configuration as presented in the Pecan Street Project DataPort and utilized their publicly available datasets as the primary source of contextual data. The Pecan Street Project is a smart grid initiative that deploys energy monitoring instrumentation (and partial actuation) in residential buildings across several U.S. states such as Texas, California, New York. Its infrastructure includes various sensing systems and energy management technologies—including energy management systems (EMS), rooftop photovoltaics (PV) meters, electric vehicle (EV) meters, and residential energy storage systems—to track and analyze electricity consumption and generation . For measurement, the project uses eGauge energy sensors to monitor circuit-level electricity usage for multiple appliances and systems, providing one-minute circuit-level and whole-building electricity data from households . In this study, we used historical data from four buildings in the Pecan Street DataPort to simulate the perception module’s functions. In the prototype, two separate files represent the simulated perception and brain modules interface:

-

A JSON file (smart meters JSON file) stores the data on the current statuses of all devices and available resources. It contains date and time, building identifier (for different tested buildings), and available energy meters (i.e., available devices being monitored). Each meter entry includes an ID, name, description, status, unit (kW), and real-time energy consumption. For example: { “Dishwasher”: { “name”: “Dishwasher”, “description”: “eGauge meter data present for power draw of the dishwasher.”, “status”: “AVAILABLE”, “online”: true, “unit”: “kW”, “value”: 1.8 } }. This entry indicates that the dish washer is currently using 1.8 kW of power. When the AI agent needs current states of the devices/appliances (i.e., the “real-time” states), it calls functions to retrieve the relevant data from the smart meters JSON file, as illustrated in Figure 2.

-

Instead of a database system, in the developed prototype, a CSV file stores the historical energy consumption data for all devices/appliances, represented as energy use time series (in kWh). This file represents the processed historical energy data provided to the prototype’s brain module. The CSV file headings include the names of different appliances and devices in the building in one table. The number of these devices is different across buildings.

Brain module

As the AI agent’s core computational processor that enables the overall system’s functionality, the brain module encompasses several key elements including (i) profiles (for the AI agent, the user(s), and the building), (ii) the historical energy dataset, (iii) a long-term memory, (iv) a reasoning logic, and (v) several functions that enable analysis and actuation. The brain module elements and their integration are as illustrated in Figure 2 and outlined in pseudocode in Algorithm [alg:configure_bems].

AI Agent, User(s), and Building Profiles: The profiles guide the AI Agent’s brain module by setting objectives and establishing its knowledge base. The AI agent profile includes a general description of the AI agent’s role (e.g., “You are an AI agent for a smart building energy management system…”) and its capabilities (e.g.,“You have access to the database of a smart building energy usage…”). This profile provides a comprehensive set of instructions for the AI agent and defines its identity and skill set. The user profiles describe resident(s’) characteristics (e.g., “The users who live in this single-family house are a family of four: 2 adults, 2 children…”) These profiles can be expanded with more information to enable personalized user interactions. The building profile comprises different sets of information: (1) the sensor list, which explains all sensors collecting energy consumption data from appliances, (2) the device list, which details all connected IoT smart appliances, and (3) the electricity time-of-use rates. The lists include names of the sensors and devices that match exactly with the data from the JSON files of the simulated appliances. The electricity rates include off-peak (00:00 - 17:00, 20:00 - 24:00) and peak (17:00 - 20:00) rates, credits for energy exported back to the grid, and EV discounts between 00:00 and 06:00. These information sets help the AI agent understand the context of the energy consumption data, specific device configurations, and associated energy cost to better assist users with their requests. All profiles are text-based prompts uploaded to the OpenAI Assistants API to build the AI agent.

Energy Data: The energy dataset serves as the input for the AI agent’s brain module, allowing it to analyze energy supply/consumption patterns and offer user suggestions. The energy data could include both historical and real-time data streams. As noted, for this prototype, we used data from the Pecan Street project in a CSV file format. To this end, we extracted one month of historical energy supply and consumption data from four houses (two in Texas and two in New York) as case study testbeds. These datasets consist of various time series sampled at 15-minute intervals, representing attributes such as grid electricity usage, energy generation, EV charging, and circuit-level appliance consumption data (e.g., air conditioning systems and kitchen appliances). Houses equipped with pv panel systems may exhibit negative grid usage values, indicating excess electricity export to the grid.

Long-term Memory: The long-term memory is implemented as a persistent knowledge layer that captures stable user preferences, recurring behavioral patterns, and system-relevant constraints derived from user–agent interactions. Rather than storing raw conversational history, the memory formation process follows a deliberate extraction and consolidation mechanism, in which the AI agent identifies candidate memory entries based on explicit user instructions (e.g., “Remember that…”) or implicit signals indicating consistent and future-relevant intent. During this process, the AI agent transforms interaction content into structured, normalized memory representations that encode actionable information such as device targets, temporal conditions, and recurrence patterns. For example, when a user requests lowering the air conditioning (AC) temperature after 10 p.m., the agent derives a semantic rule such as “The user prefers a lower AC setpoint at 10:00 PM on a daily basis”, which is stored as a long-term memory entry. Stored memories subsequently inform future reasoning related to AC control, thermal comfort, and energy efficiency recommendations. Users retain direct governance over the memory system and may explicitly add, modify, or remove memory entries through natural-language commands. In the prototype, validated memories are persisted in a structured JSON format and accessed by the AI agent through tool-based retrieval and update operations. While this implementation is lightweight, it demonstrates a principled memory derivation mechanism that can be extended in future work using more advanced memory management frameworks.

Procedure:

-

Initialize Agent Instructions

-

Load AI_agent_profile, user_profile, building_profile (energy_meter_profile, device_profile).

-

Store these profiles in structured AI_agent_instructions.

-

-

Define Tools and Their Schemas

-

Register available API tools (e.g., code_interpreter, file_search).

-

Define additional tools (device, schedule, memory) with corresponding schemas and core methods (sync, query, execute).

-

-

Establish Reasoning Logic

-

For each incoming user query:

-

Interpret query intention.

-

Determine primary category (1 of 6 main categories).

-

Identify secondary category (1 of 24 subcategories).

-

Select functions from AI_agent_instructions:

if query_category = “Energy Consumption and Analysis - Energy Historical Data” then code_interpreter(historical_energy_data_file) else if query_category = “Device Control - Device General Operation” then device_execute(device_status)

$`\vdots`$

-

-

Check if additional information is needed:

if additional information is required then call memory functions or request user input if function call valid then proceed else respond with explanation

-

-

Incorporate Agent Instructions

-

Compile relevant profiles and reasoning logic in AI_agent_instructions.

-

Specify AI_agent_model (e.g., “gpt-4o”).

-

-

Prepare Data Files

-

Upload historical_energy_data_file.

-

Include additional files (energy_rate, memory_file) as needed.

-

-

Deploy the AI Agent

- Deploy the configured BEMS_AI_agent via the appropriate API.

Tools/Functions Design: The AI agent has been equipped with various tools that enable it to perform complex tasks and interact with smart home sensors, meters, and devices. These tools facilitate the functioning of the perception and actions modules. Following intent classification, user queries are processed according to detailed instructions on the tools to be employed, corresponding to different query categories. OpenAI Assistants API provides two built-in tools that can be directly utilized: “File Search” for processing and searching through files, and the “Code Interpreter” for writing and executing Python code, enabling the processing of different data files. In addition to these built-in tools, we developed customized functions for interacting with smart home meters and devices. For meter-related tasks, we implemented “action-meters-QUERY” to retrieve readings and information from smart meters within the smart home. For device-related tasks, a sync-query-execute workflow was implemented to ensure that the AI agent operates with grounded device information (as shown in Figure 2), rather than hallucinating unavailable devices or unsupported functionalities. The “action-devices-SYNC” and “action-devices-QUERY” functions retrieve device metadata and real-time operational states from the smart home environment, while “action-devices-EXECUTE” issues validated commands to modify device states accordingly. Schedule-related functions include “action-schedule-CREATE”, “action-schedule-SYNC”, and “action-schedule-CHANGE” to create, synchronize, and modify device schedules. Similarly, memory-related functions, such as “action-memory-CREATE”, “action-memory-SYNC”, and “action-memory-CHANGE”, manage the AI agent’s memory generation and management. All the customized functions have been used to simulate the information queries and device control by processing the JSON file representing smart devices and energy sensors.

Reasoning Strategy: LLM-based AI assistants could use different reasoning strategies to complete tasks. Among different alternatives, in our prototype, we have included Chain-of-Thought (CoT) and Tree-of-Thought (ToT) frameworks to guide the LLM’s reasoning process because they provide complementary reasoning capabilities. Unlike the traditional Input-Output (IO) modality, where the LLM directly generates a final response upon receiving users’ queries, the CoT framework, introduced by Wei et al. , uses intermediate reasoning steps, enhancing the LLM’s reasoning, computation, and planning capabilities in complex tasks such as building energy management . Additionally, the ToT framework allows the LLM to branch at certain points in the reasoning process, enabling it to decompose user queries into subcategories, which are then addressed with specific instructions or tools .

For the ToT-based user queries intent classification, we adopted a set of user intent categories synthesized from prior Human-AI interaction and agent design studies , and further extended them to support energy-centric analysis tasks relevant to building energy management. As summarized in Table [tab:intent_categories], user queries are organized into six primary intent categories: Energy (Energy Consumption & Analysis), Cost (Cost Management), Device (Device Status & Control), Schedule (Device Scheduling & Automation), Memory, and General (General Information & Support). Each primary category is further decomposed into three to five secondary intent categories, resulting in a total of 24 intents. This hierarchical categorization is embedded within the CoT reasoning structure (Algorithm [alg:configure_bems], Procedure 3), where the initial reasoning step focuses on identifying the primary intent, followed by a secondary classification step that refines the user’s underlying goal. The introduction of secondary intent categories enables more precise intent disambiguation and improves the agent’s ability to map user queries to appropriate tools/functions or control actions. All intent definitions, category descriptions, and representative example queries are encoded as text-based prompt instructions and integrated into the AI agent profile.

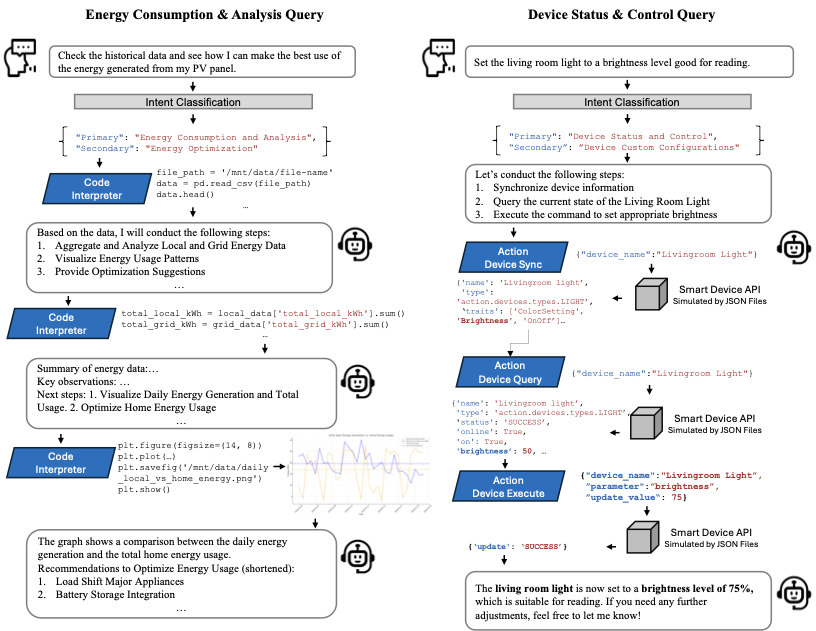

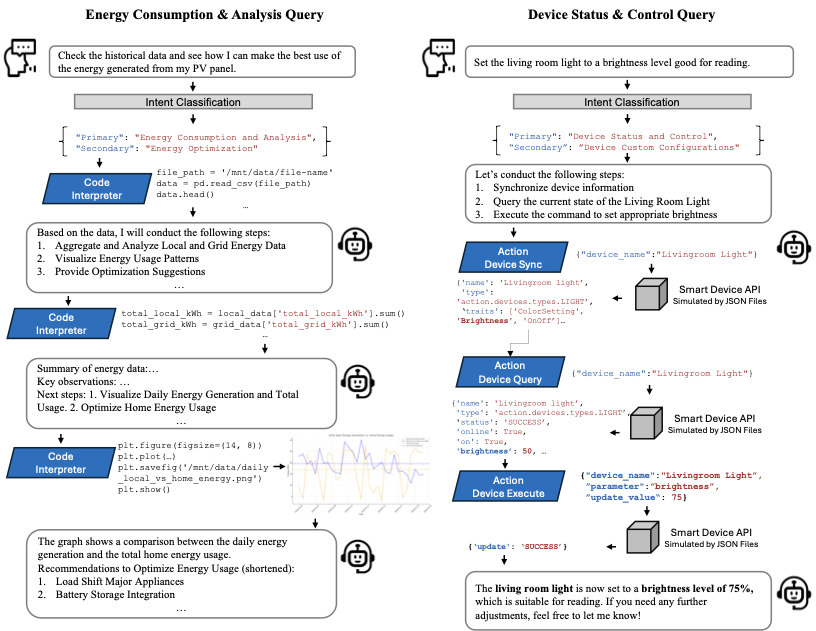

As illustrated in Algorithm [alg:configure_bems] (Procedure 3) and Figure 2, the AI agent processes user queries and generates responses using a step-wise Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning framework, while the Tree-of-Thought (ToT) framework supports structured intent classification and action selection. Upon receiving a user query, the agent first analyzes the user’s intent and classifies it into one primary category (out of six) and one secondary category (out of 24), as defined in Table [tab:intent_categories]. For example, when a user asks about the appliance with the highest energy use in the past month, the AI agent classifies the primary category as “Energy Consumption & Analysis” and the secondary category as “Energy Historical Data”. This categorization represents the reasoning branches within the ToT framework, which govern how the agent explores multiple solution pathways or requests further details. Once the intent categories are identified, the CoT instructions encoded in the agent profile guide the generation of intermediate reasoning steps (e.g., selecting the appropriate energy data source or determining the required analysis). The agent then invokes pre-defined functions or tools, such as a code interpreter for historical energy analysis or a device execution function for appliance control. Some tools generate outputs directly (e.g., numerical results or visualizations), while others rely on data retrieved from external APIs, such as smart meter readings or real-time device status. In the final CoT step, the agent synthesizes the tool outputs and presents the results to the user in natural language. This integrated reasoning workflow enables the agent to adapt effectively to user queries of varying complexity.

Action module

Simulated Smart Devices: Similar to the approach used for the perception module, in this prototype, the action module was simulated by mimicking the operation of external APIs, represented by a JSON data schema (Figure 2). This setup includes smart devices, each represented through a {“Parameter”:“Value/State”} format to represent the status of devices, encompassing “devices-info” and “devices-state”. To enable control operations, Python functions were developed as a mock backend, reflecting how commands would be executed on physical devices. These functions process incoming requests from the AI agent, adjust the simulated states of smart devices, and update the JSON files accordingly.

AI Agent Responses: The AI agent’s outputs, ranging from suggestions for energy savings and device control strategies to analysis results and visualizations, are presented to users through an interactive and conversational interface. For instance, the agent may provide graphs illustrating historical energy consumption, provide textual summary information, or propose adjustments to improve usage. During testing, these responses were logged and employed for the framework evaluation, allowing us to assess how effectively the AI agent responds to user queries for managing smart building energy usage.

Prototype Evaluation

Experiment Design

The evaluations focused on two aspects: (1) the feasibility and latency of the BEMS AI agent prototype in responding to different categories of user queries and (2) to assess the generalizability of the framework across different contexts. Therefore, we used historical data from four residential buildings (houses) with varied configurations. As noted, historical energy data for these houses were extracted from the Pecan Street Dataset, focusing on one month of energy consumption data from two buildings in Texas (ID: TX-01 & TX-02, January 2018) and two buildings in New York (ID: NY-01 & NY-02, August 2019). Table [tab:test-buildings] shows the characteristics of these houses, which represent different smart home configurations. All four cases included photovoltaic panels and electric vehicle charging, which make them prosumers and expand the scope of query assessments.

Based on previous studies , user queries were categorized into six primary and twenty-four secondary categories, as detailed in Table [tab:intent_categories]. For each secondary category, five distinct user queries were posed to the AI agent. This comprehensive testing approach allows for a multifaceted evaluation of the AI agent’s capabilities. Queries related to energy consumption analysis and cost management assess the AI agent’s core functionalities, including providing suggestions and information visualization to users for home energy management. Queries regarding device status and control test the AI agent’s perception and action modules, particularly its connectivity with external APIs in a simulated environment. Meanwhile, queries on device scheduling, automation, and memory evaluate the AI agent’s ability to create schedules and store memory based on general or vague user requests. Finally, general information and support queries assess the AI agent’s performance in providing guidance, troubleshooting, and technical support. Different types of queries initiate different pre-defined tools (functions) configured for the AI agent, and the tool/function call results are used by the AI agent for further actions as elaborated in Algorithm [alg:agent_test]). In total, 120 queries across six primary categories were tested for each testbed building, resulting in 480 observations overall. The AI agent’s responses and their response latency (time), as well as token usage were recorded in markdown files (md format) as shown in the Algorithm [alg:agent_test]. These interaction logs were used for performance assessment using predefined evaluation metrics.

Procedure:

-

Initialize Memory

-

Load memory_file.

-

Prepare additional_instructions (e.g., extra memory content or configuration parameters).

-

-

Process User Queries

-

For each query_id in queries_dict:

-

Retrieve user_query = queries_dict[query_id].

-

Call AI_AGENT_SERVER(AI_agent_name, user_query, data_file_path, …):

(a) Start the timer.

(b) Run the AI agent with user_query.

(c) While agent_state is"queued"or"in_progress":

wait.(d) If agent_state =

"requires_action":

perform function calls, gather function_result,

and submit function_result back to the AI agent.

(e) Continue running the AI agent until agent_state ="end".

(f) Stop the timer and record execution time and token usage.

(g) Record function calls, execution time, token usage, and response content in query_id_interaction_log_file (md).

(h) If necessary, update memory_file and save as updated_memory_file

-

-

-

Finalize

- Print confirmation:

"All queries have been processed by the AI Agent."

- Print confirmation:

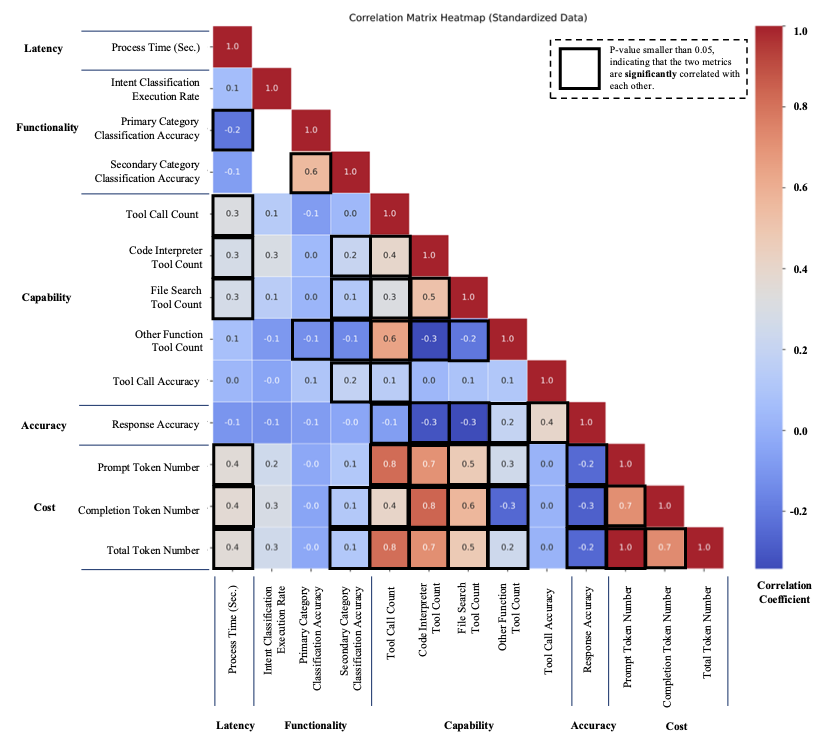

Evaluation Metrics: The prototype’s performance was evaluated using metrics derived from previous studies . The evaluation covered five key indicators, including latency, functionality, capability, accuracy, and cost, which will be described below. The detailed description and the dimensions of these metrics have been presented in Table [tab:eval-anova].

(1) Latency — The response latency of the AI agent was measured in seconds, defined as the elapsed time between receiving a user query and generating a final natural-language response. This latency measurement captures the end-to-end processing time of the agent, including intent classification, intermediate reasoning, tool call, and response synthesis. Latency statistics were analyzed across different query categories to assess the agent’s responsiveness under varying task types and reasoning complexity. By comparing processing times among categories, this evaluation provides insight into how different reasoning paths and tool dependencies affect system responsiveness in practical usage scenarios.

(2) Functionality — The AI agent’s intent classification performance was evaluated by comparing its predicted primary and secondary intent categories for each user query against predefined ground truth labels. Ground truth intent annotations were specified in advance for all test queries. Classification accuracy was used as the primary evaluation metric, providing insight into the agent’s ability to correctly interpret user intent, adhere to the prompt-based instructions, and follow the Tree-of-Thoughts reasoning structure when categorizing queries and selecting appropriate actions.

(3) Capability — The AI agent’s ability to appropriately invoke external tools (e.g., “Code Interpreter” or “action-devices-EXECUTE”) was evaluated during response generation. Tool activation accuracy was assessed through manual inspection of whether the agent correctly selected and executed the required tools for each query. Responses that activated all expected tools were classified as fully accurate (score = 1). Responses that activated incorrect tools or failed to activate any required tools were classified as incorrect (score = 0). Partial accuracy (score = 0.5) was assigned when only a subset of the expected tools was correctly activated.

(4) Accuracy — To evaluate the reliability and accuracy of the AI agent, we constructed a benchmark dataset containing ground-truth response logic and correct outputs for each test query by manually processing the input data. The agent-generated responses were then compared against this benchmark to assess response accuracy. For queries involving code generation or numerical calculations, both the correctness and completeness of the generated code were examined. Additional evaluation criteria were applied to specific query types. For prediction tasks, the agent’s outputs were compared with ground-truth future energy consumption data. Visualization tasks were evaluated based on readability and informativeness. Response accuracy was also rated using a three-level scale: correct (1), partially correct (0.5), and incorrect (0). Responses were identified as correct when both the reasoning process and the final outputs fully matched the benchmark logic and ground-truth results. On the other hand, a response was labeled as partially correct when portions of the reasoning process or underlying logic were valid, but the final numerical results or conclusions did not exactly match the ground-truth answers. Responses were labeled as incorrect when the reasoning, methodology, or final results substantially deviated from the benchmark, or when the generated outputs failed to address the query requirements.

(5) Cost — The cost refers to the AI agent’s inference cost, considering that the prototype used OpenAI’s GPT-4o in zero-shot mode. The number of tokens used (input and output) and the token usage cost associated with tool usage (e.g., “Code Interpreter” and “File Search”) were tracked. A token refers to a piece of text, such as a word or part of a word, that serves as the basic unit of analysis for the LLM’s processing and understanding of language. Token costs were calculated based on OpenAI pricing models. It is worth noting that the price of the tokens may vary based on the usage of the language model and the updates of the APIs.

Analysis Methods: Descriptive statistics, including the mean, median, and standard deviation, were computed for all evaluation metrics, along with frequency distributions and ratios to summarize overall performance patterns. These statistics were visualized using bar charts and box plots to facilitate comparative analysis. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess the generalizability of the proposed prototype across different buildings by examining whether statistically significant differences existed in evaluation metrics under varying building contexts. In addition, ANOVA was used to evaluate the AI agent’s performance across different query categories by analyzing between-group and within-group variance, thereby identifying whether certain types of queries posed systematically greater challenges to the agent. These analyses enable a rigorous examination of performance consistency and robustness across heterogeneous operational conditions. Complementary qualitative content analysis was conducted to provide deeper insights into the AI agent’s tool usage behavior and response generation strategies that are not fully captured by quantitative metrics.

Results and findings

In this section, we have first presented the generalizability assessment of the AI agent across different buildings to show that the framework generalizes well across buildings and then discussed the performance of the proposed AI agent framework by using the average of evaluation metrics across all user queries.

Framework’s Generalizability

To validate the framework’s generalizability, we calculated the mean value of the evaluation metrics for each testbed and conducted a one-way ANOVA test. The null hypothesis of the ANOVA test was that the means of the evaluation metrics from the four residential buildings are equal. The results are presented in Table [tab:eval-anova]. As shown, all but one of the one-way ANOVA test results have a p-value greater than 0.05, indicating no statistically significant difference between the mean responses from the tests conducted on the four testbeds. The only metric showing a significant difference is the intent classification execution rate (p-value = 0.04), with a Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test revealing that the mean values from TX-02 and NY-02 testbeds were significantly different, with a mean difference of 0.16. These results demonstrate that the AI agent’s responses across the four buildings are consistent, thereby verifying the generalizability of the framework for energy management tasks across different buildings with performance consistency.

Since the prototype’s performance was consistent across the four testbeds, we averaged the performance metrics, as shown in Table [tab:eval-anova]. In terms of latency, the AI agent took approximately 23 seconds on average to respond to user queries. Regarding functionality, around 60% of the responses involved step-wise intent classification as guided by the Tree-of-Thought structure embedded in the AI agent’s profile prompts. The intent classification achieved high accuracy (0.91) in identifying the first category of user queries, but a lower accuracy (0.75) for the secondary category classification task. As for the prototype’s capability in tool usage, the tool call accuracy was high at 0.94, with various tools (e.g., code interpreter, file search, and other functions) triggered based on the type of user query. The average response accuracy among all four test houses of 0.79 indicates the AI agent’s promising performance in handling user queries. From a cost perspective, considering the OpenAI pricing for the tested model (gpt-4o, $2.50 per 1M input tokens, $10.00 per 1M output tokens, accessed in October 2024), the average cost per query was $0.0776 (with a total of 29,467 tokens). The evaluation metrics vary across different categories of user queries, which will be discussed further in the following sections.

Note: The p-value is lower than the alpha level of .05, and the null hypothesis is rejected.

Performance Differences Among Categories of User Queries

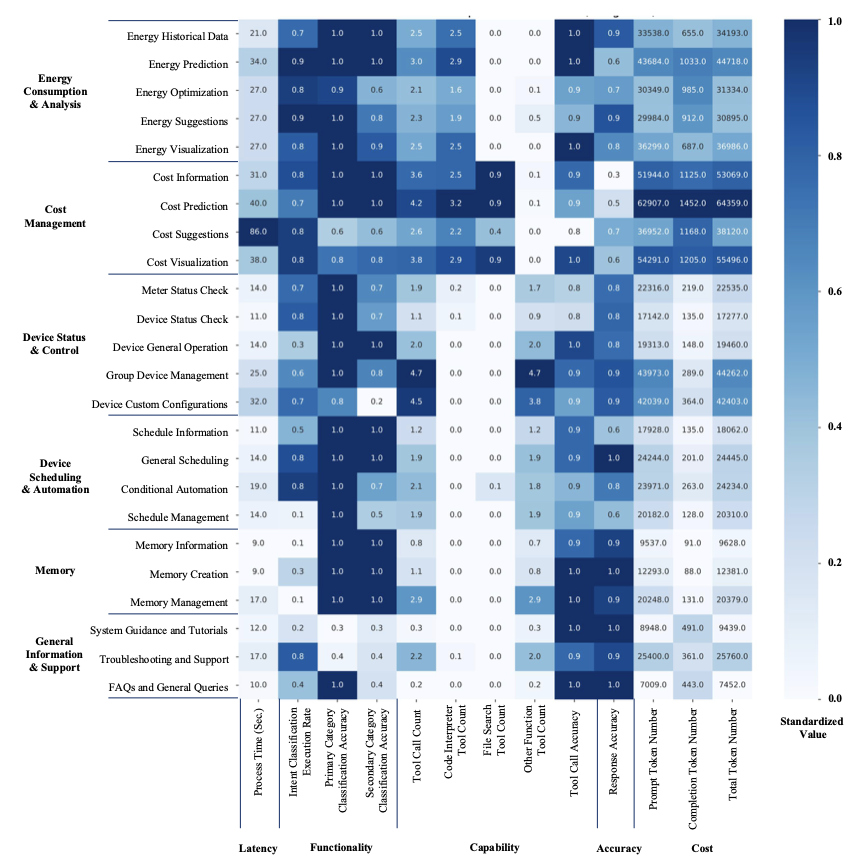

The performance evaluation metrics for different primary categories of user queries are presented in Table [tab:metrics_function_capa] (presenting functionality and capability metrics) and Table [tab:metrics_time_cost_acc] (presenting latency, cost, and accuracy). From the functionality perspective (i.e., intent classification and category identification), the prototype performed well in energy consumption & analysis and cost management tasks, achieving high execution rates and query intent classification accuracy (Table [tab:metrics_function_capa]). However, for queries related to IoT device control (device status & control, device scheduling & automation), the intent classification execution rate dropped to 0.55-0.62. The rate further decreased for tasks related to memory (0.13) and general information & support (0.45). This suggests that, for complex tasks requiring a reasoning process, the AI agent follows the designed instructions to perform intent classification. However, for more straightforward user queries, such as general information & support, the AI agent tends to bypass intent classification and directly processes the queries.

Regarding the AI agent’s capability in tool calls, it performed well with tool call accuracy exceeding 0.90 across all query categories. Queries related to the computation and calculation of energy and cost required more tool calls associated with the code interpreter (2.28 and 2.71, respectively). In contrast, queries related to smart device control more frequently triggered other function tools related to the control of IoT devices (2.63 for device status & control, and 1.71 for device scheduling & automation). The file search tool was primarily triggered for cost management tasks (0.8), where the AI agent needed to access stored files to retrieve energy pricing information for calculations.

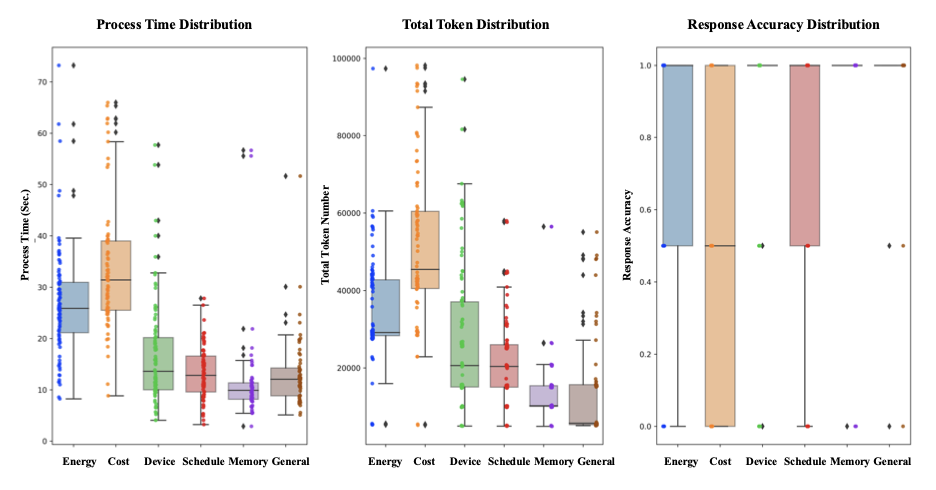

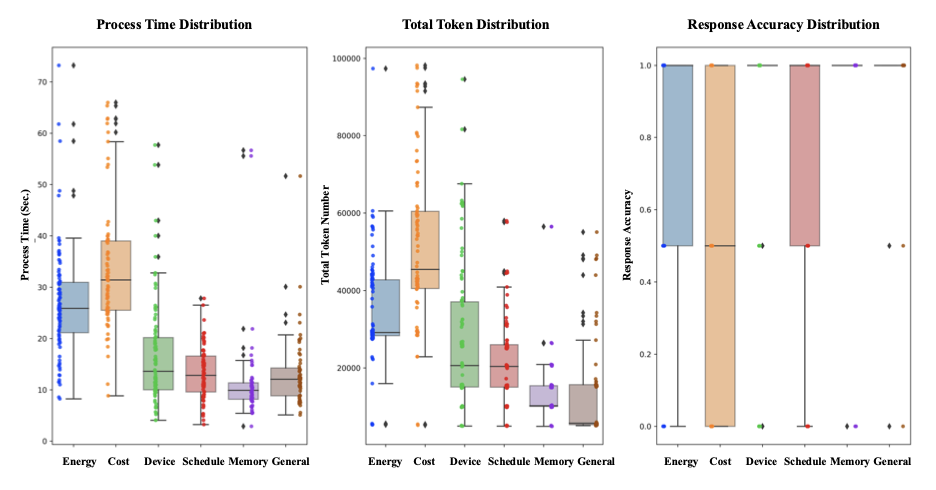

In terms of the prototype’s latency, queries related to cost management required the longest processing time, with an average of 49 seconds. Further investigation revealed two outlier values (over 600 seconds) that skewed the mean. After removing these outliers, the average processing time for cost management tasks was approximately 34 seconds. Energy consumption & analysis tasks also required more processing time, with an average of 27 seconds. In comparison, the process time for device control and scheduling tasks were shorter, averaging 19 and 14 seconds, respectively, while memory and general information queries took 12 and 13 seconds. A major factor contributing to the longer processing times was the higher token usage in tasks requiring access to historical energy data and code execution for energy analysis and cost management. This is further illustrated in Figure 3, where the distribution of the evaluation metrics is presented in box plots for different categories of user queries. The box plots demonstrate a clear distribution pattern between processing time and token usage across query types.

Although the AI agent used more resources and time for tasks related to energy and cost analysis, the response accuracy indicates that improvements are still needed. For simpler tasks such as device control and general information, the AI agent achieved high response accuracy (0.86 and 0.98, respectively). However, for more complex reasoning and analysis tasks, response accuracy dropped to 0.77 for energy consumption & analysis queries and 0.49 for cost management queries. This suggests that while the BEMS AI agent can handle general energy management tasks, its reasoning capabilities, particularly for cost management, require further enhancement. The detailed response differences across query categories will be discussed in the following sections.

Note: Two outliers (over 600 seconds of process time) were removed in the process time metric.

/>

/>

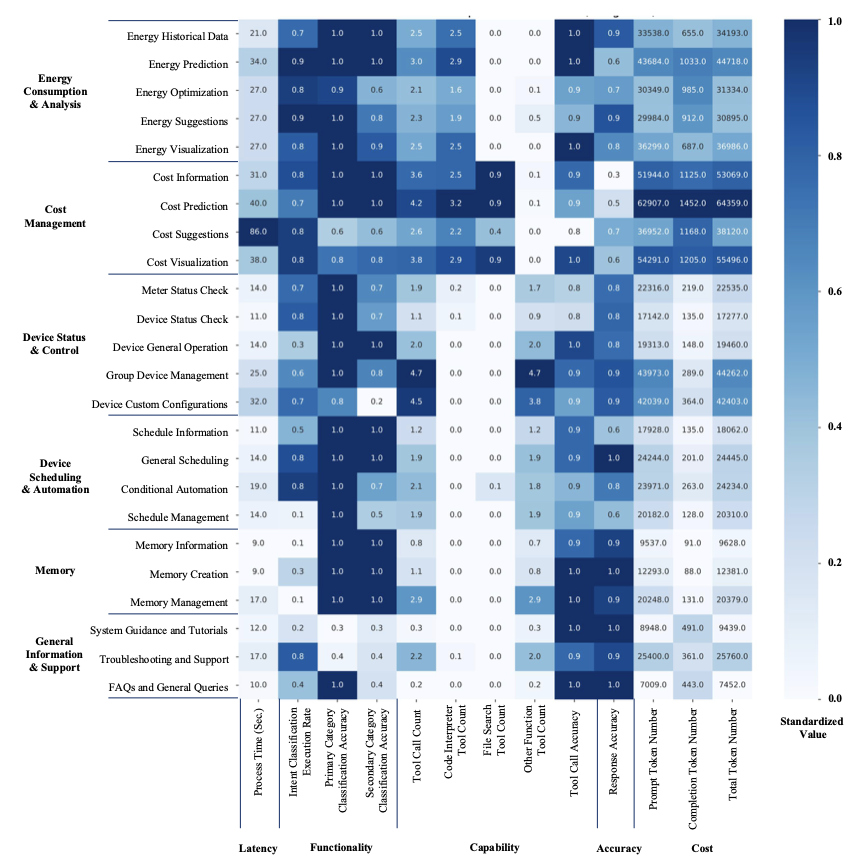

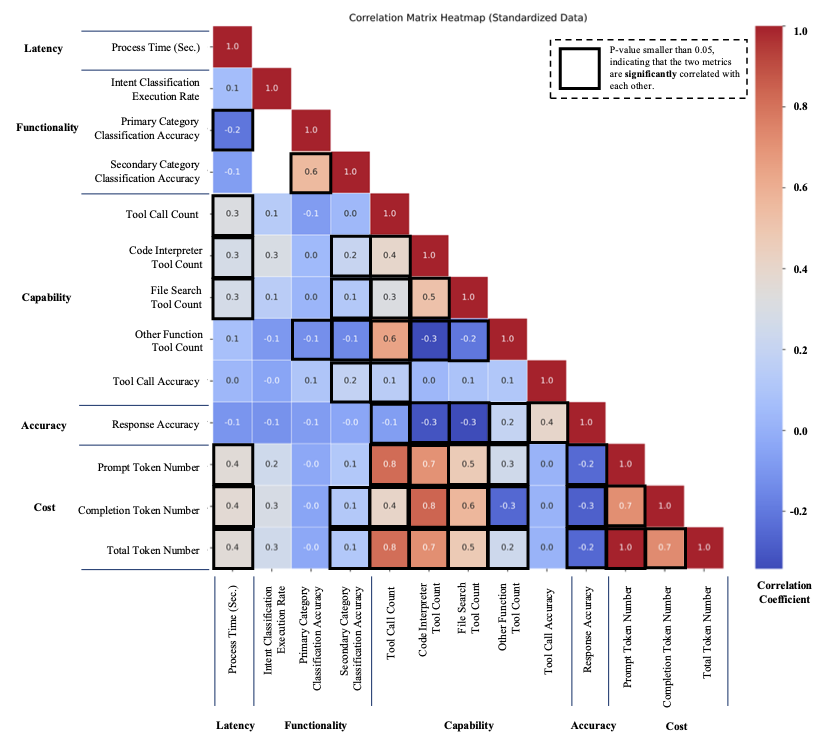

AI Agent Responses to User Queries

To further evaluate the BEMS AI agent’s performance in responding to different user queries, we compiled the mean values of the evaluation metrics across all secondary categories. Since each secondary category includes five queries, and these queries were tested across four residential buildings, each value represents the mean of 20 data points. These mean values were used to create a heatmap to visualize the distribution of the evaluation metrics for the various secondary categories of test queries, as shown in Figure 4. In the heatmap, the blue color indicates the relative values for each evaluation metric standardized along each column. The actual mean values of the evaluation metrics are displayed within each cell for reference. For example, in the “Latency - Process Time (Sec.)” column of Figure 4, within the “Device Status & Control” primary category, tasks such as device and meter status checks take only around 11-14 seconds to execute. In contrast, more complex queries, such as those related to custom device configurations and group device management, take significantly longer, approximately 25-32 seconds. This example highlights the heatmap’s usefulness in revealing the AI agent’s performance variations when handling different types of user queries in greater detail. This visualization have also been referred to in subsequent subsections to explore the AI agent’s dynamic response performance across various user queries.

/>

/>

Energy Consumption & Analysis

/>

/>

One of the major goals of the BEMS AI agent is to provide context-aware energy management insights and suggestions to users. The tested results (Figure 4) reveal that the AI agent prototype performed well in tasks related to historical energy data analysis (with a response accuracy of 0.9), energy suggestions (0.9), and energy visualization (0.8). However, in tasks related to energy prediction (0.6) and energy optimization (0.7), there is still room for improvement. The result logs for each response to the tested user queries were analyzed to study the workflow of the AI agent in responding to queries. As shown in the example presented in Figure 5, when the user asked how to best utilize the energy generated from the PV panel, the AI agent first conducted intent classification to identify the query’s purpose. Following this, the tool “Code Interpreter” was activated to load the stored historical energy data file. Based on the initial data loading, the AI agent outlined the steps required to provide recommendations, then wrote and executed Python code within “Code Interpreter” to generate the initial analysis results. These results enabled the AI agent to identify historical local generation and usage patterns, after which it plotted a figure to visualize these patterns and offered specific recommendations based on the observed trends. This example illustrates how the AI agent follows a logical workflow to systematically provide energy management suggestions and demonstrates its context-awareness by offering recommendations based on actual energy consumption data rather than generic suggestions.

The strong context-aware computing and reasoning abilities of the AI agent are further evident in its handling of energy analysis, optimization, and suggestion tasks. For example, in response to the energy optimization query asking “What are the best practices for optimizing energy use with my home devices?”, the AI agent not only calculated the daily energy consumption for each device but also identified peak usage times for high-consumption devices, such as the dishwasher (with a peak usage at 7:00 p.m.) and the clothes washer (with a peak usage at 9:00 p.m.). The AI agent then recommended shifting the usage of these high-consumption devices to off-peak hours. Another example is the agent’s response to the energy suggestion query asking “Can you recommend an energy-saving schedule for my home?” After analyzing the peak usage times of energy-consuming devices and proposing new schedules, the AI agent also automatically activated the tool “action-schedule-CREATE” to adjust the running schedule for the devices. This analysis-suggestion-action process is fully automated, which may appeal to some users for its convenience but may not be favored by others who prefer greater control over their smart devices.

The AI agent did not perform as well in energy prediction tasks, exhibiting long latency (34 seconds), high computational cost (the highest token usage in this category), and the lowest response accuracy (0.6). The tested queries asked about future monthly energy usage for total consumption, specific devices, and energy generation. We compared the ground truth data with the AI agent’s predictions to evaluate its accuracy. As we did not specify the methods to be used for prediction tasks, we observed that out of 20 responses, 10 used Random Forest Regression, 6 used Linear Regression, 2 used ARIMA (AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average) model, and 2 used a simple moving average forecast method. For the machine learning models, the AI agent applied the timestamps as the feature and energy usage data as the target to train the models, all of which were implemented using the “Code Interpreter” tool. Although the models were simple, the accuracy could be improved if specific steps for energy prediction were provided in the instructions. One reason for the low response accuracy is that many responses were evaluated as partially correct (0.5). For example, some responses did not correctly convert energy usage units from kW to kWh but still displayed the results as kWh. Additionally, the prediction models, being too simplistic with limited data (one month of historical energy usage with 15-minute intervals), could not generate accurate predictions, which should be improved with more historical energy data included for analysis.

In addition to energy prediction, the AI agent also failed to provide correct responses for certain test queries due to various issues. In the intent classification step, some energy optimization queries were misclassified as energy suggestion tasks. This is understandable, as there are similarities between the two tasks and their corresponding user queries. In some cases, incorrect parameters were used in the calculations, leading to inaccurate outputs. For instance, for two testbeds in Texas, historical energy consumption data was acquired from January 2018 (a winter month). The data contained records for both ’air’ (cooling system) and ’heater’ or ’furnace’ (heating system). When the user queried about energy consumption related to air conditioning (AC), the AI agent used the incorrect record, resulting in inaccurate results. Another example is the response to the query asking “When are the peak hours of my energy usage over the past month?”, where the expected response should summarize the peak hours from the entire month’s data. However, the AI agent oversimplified the task and provided specific peak hours, such as “Here are the peak hours of your energy usage over the past month: 1. January 24th, 21:00 - 22:00, with a total usage of 18.539 kWh. 2. January 12th, 16:00 - 17:00, with a total usage of 17.474 kWh …”. Although these examples highlight the AI agent’s limitations in providing accurate responses in some cases, it is worth noting that with LLM capabilities, the AI agent can understand conversational context. This allows for continuous interaction between users and the AI agent, enabling users to offer further clarification through additional prompts, guiding the AI agent to fully understand the query and generate accurate responses accordingly.

Cost Management

An effective means of assisting users in energy management decisions is to compute energy consumption data into direct financial metrics, thereby enhancing clarity around energy-related expenses. To support this objective, the AI agent accesses dynamic energy pricing, accommodating fluctuations in peak and off-peak rates. Moreover, the energy pricing file integrates data on local energy generation, including credits from excess energy returned to the grid, thereby enabling users to maximize both energy efficiency and potential savings. To evaluate the AI agent’s performance in cost management, we examined its responses to user queries related to cost information, predictions, recommendations, and visualizations. Results indicate a process time of approximately 30–40 seconds per query (Figure 4), with frequent activations of the “Code Interpreter” and “File Search” tools. However, the accuracy of responses was notably lower for cost information (0.3) and prediction (0.5) tasks. Out of the 80 user queries tested, 21 (26%) responses were accurate, 37 (46%) were partially correct, and 22 (28%) were incorrect.

To generate accurate responses for cost-related queries, the AI agent must accurately analyze energy consumption data, retrieve current electricity rates, calculate costs based on consumption and pricing, and synthesize results for user-friendly reporting. Given the multi-step nature of this process, errors in any step can lead to partially or entirely incorrect responses. For instance, in response to the query “Can you provide a breakdown of my past month’s energy cost?”, the AI agent incorrectly classified energy generation as a cost rather than a cost-reducing credit, leading to inaccurate reporting. Similarly, when queried about air conditioning (AC) energy consumption, misidentifying the record reference (’air’ cooling system instead of ’heater’ or ’furnace’ heating system) led to erroneous results.

Despite these challenges, the agent demonstrated promising capabilities in scenarios where it provided correct responses. For example, in response to the query “What device incurred the highest charge on my energy bill last month?”, the AI agent accurately calculated costs for all home appliances and identified the electric vehicle charger as the device with the highest charge. In another case, for energy cost prediction the query “What is the estimated cost of my energy usage for next month?”, the AI agent employed random forest regression to forecast energy usage and then calculated an estimated cost of $51.73, closely aligning with the actual cost of $52.86. These correct responses highlight the AI agent’s potential in cost management, if its processes can be standardized and rigorously validated for accuracy. Enhancements in instructional design and system architecture are necessary to further improve the AI agent’s accuracy of cost management.

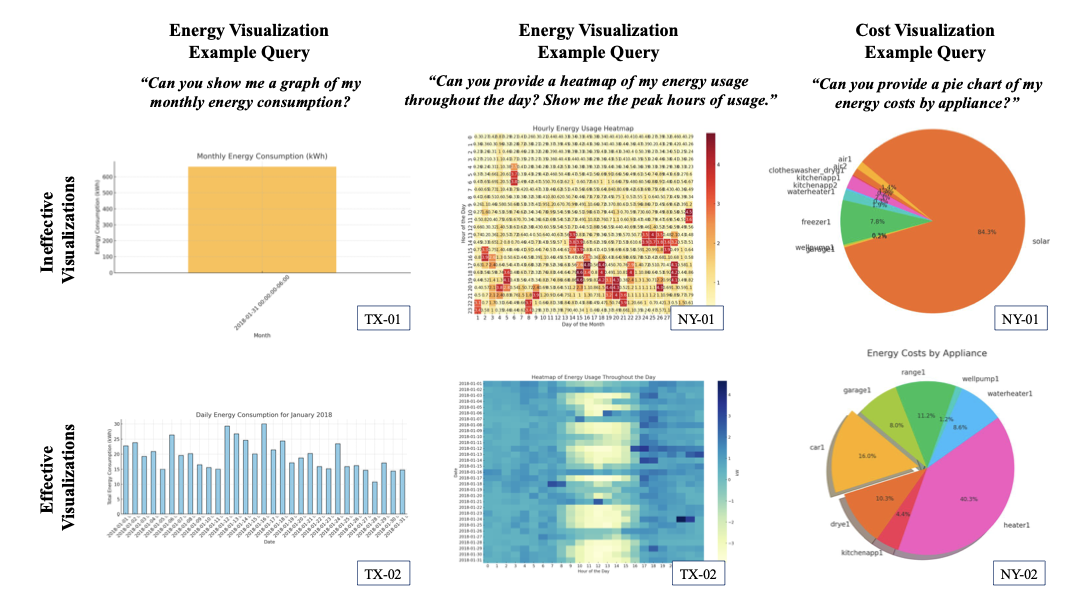

Data Visualization

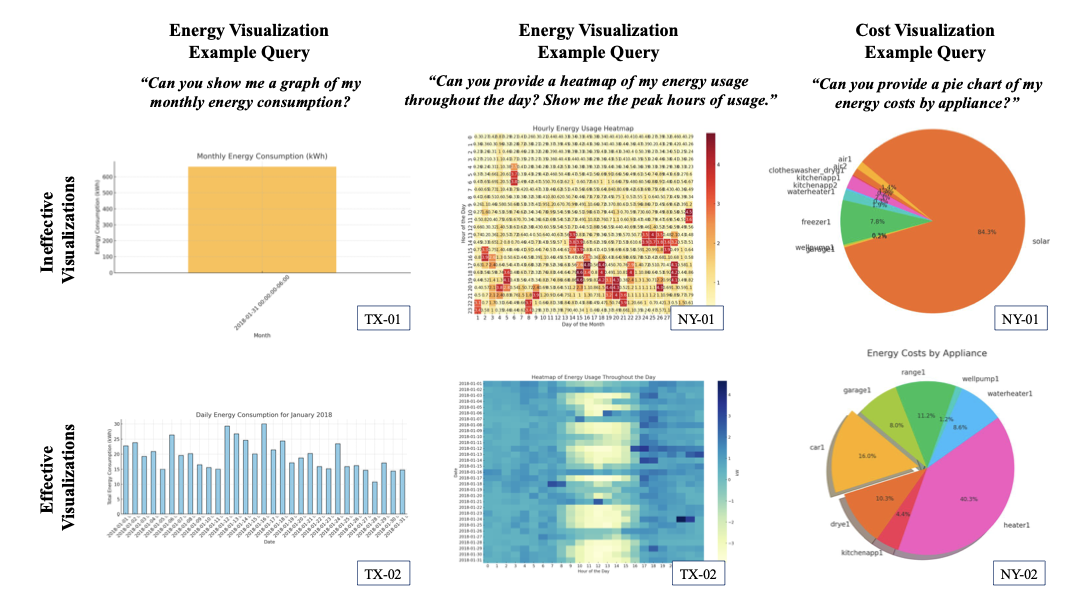

Using the “Code Interpreter” tool, the AI agent executes Python code to generate data visualizations in response to user queries. To evaluate this capability, we designed queries focused on energy visualization and cost visualization to assess its support for users’ decision-making processes. Of the 40 visualizations produced in response to these queries, 3 were entirely incorrect, 21 were partially correct, and 16 were accurate. We categorized the partially correct visualizations as inefficient, while accurate visualizations were classified as efficient, as demonstrated in the examples shown in Figure 6.

/>

/>

The inefficient visualizations provided insufficient information for effective energy management. For instance, in response to the query “Can you show me a graph of my monthly energy consumption?”, the response from the TX-01 testbed presented a single bar chart representing total monthly energy consumption. This visualization failed to offer meaningful insights for users. In contrast, the response from the TX-02 testbed generated a series of daily energy consumption bars, illustrating fluctuations and peaks across the month, and offering more actionable information for users. Similarly, in response to the query “Can you provide a pie chart of my energy costs by appliance?”, the response from the NY-01 testbed included energy credits within the energy cost breakdown, without direct user question. Conversely, the visualization generated for the NY-02 testbed provided a detailed and accurate pie chart, meeting user needs more effectively. Improving the generation of efficient visualizations will require refining the AI agent’s instructions and workflow design. Specifically, when user queries are general or vague, the AI agent should seek further clarification (e.g., plot type, data range, etc.) to produce more informative visualizations conducive to decision-making.

In addition to queries that explicitly request visualizations, the AI agent autonomously generated visualizations for certain unspecified queries, illustrating its proactive decision-support capabilities. In 33 instances, the AI agent created visualizations without explicit prompts, including 8 instances related to cost management and 25 related to energy consumption analysis. For example, for the query “Can you recommend an energy-saving schedule for my home?”, for the TX-01 testbed, it generated a heatmap displaying average energy consumption across weekday hours. This visualization effectively highlighted peak usage periods, enhancing the agent’s explanation of the recommended energy-saving schedule. Although some of the unanticipated visualizations are efficient visualizations that can contribute to AI agent’s responses, some of the visualizations are inefficient and less informative. The mechanics of generating data visualization without specification need to be further standardized. In addition, the impact of unanticipated visualizations on user satisfaction with the AI agent’s responses needs further investigation in future studies.

Device Control and Scheduling