Coordinated Humanoid Manipulation with Choice Policies

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Coordinated Humanoid Manipulation with Choice Policies- ArXiv ID: 2512.25072

- Date: 2025-12-31

- Authors: Haozhi Qi, Yen-Jen Wang, Toru Lin, Brent Yi, Yi Ma, Koushil Sreenath, Jitendra Malik

📝 Abstract

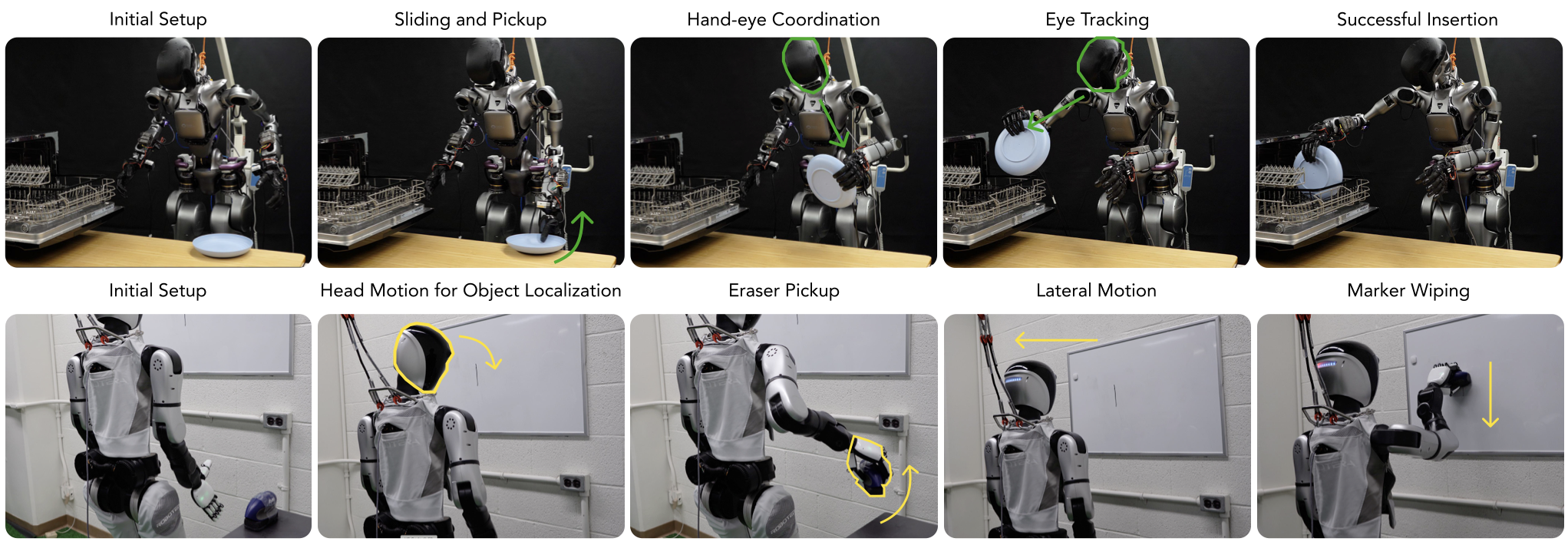

Humanoid robots hold great promise for operating in human-centric environments, yet achieving robust whole-body coordination across the head, hands, and legs remains a major challenge. We present a system that combines a modular teleoperation interface with a scalable learning framework to address this problem. Our teleoperation design decomposes humanoid control into intuitive submodules, which include hand-eye coordination, grasp primitives, arm end-effector tracking, and locomotion. This modularity allows us to collect high-quality demonstrations efficiently. Building on this, we introduce Choice Policy, an imitation learning approach that generates multiple candidate actions and learns to score them. This architecture enables both fast inference and effective modeling of multimodal behaviors. We validate our approach on two real-world tasks: dishwasher loading and whole-body loco-manipulation for whiteboard wiping. Experiments show that Choice Policy significantly outperforms diffusion policies and standard behavior cloning. Furthermore, our results indicate that hand-eye coordination is critical for success in long-horizon tasks. Our work demonstrates a practical path toward scalable data collection and learning for coordinated humanoid manipulation in unstructured environments.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **Modular Teleoperation Interface:** This paper introduces a modular teleoperation interface to simplify whole-body control of humanoid robots. The user can select and switch between specific skills, such as mapping VR controller pose changes directly to the robot's arm end-effector positions.-

Choice Policy: Choice Policy generates multiple predictions for given observations, capturing multimodal behaviors while enabling efficient whole-body control through a single forward pass of a neural network.

-

Experimental Results: The paper evaluates the effectiveness of Choice Policy in tasks such as dishwasher loading and whiteboard wiping, demonstrating its superior performance over diffusion policies and behavior cloning methods.

Sci-Tube Style Description:

- Beginner Level: This paper presents an interface that allows VR controllers to control a humanoid robot’s arms, hands, and head, making complex tasks easier. It also introduces Choice Policy, which helps robots learn different ways to perform tasks.

- Intermediate Level: Choice Policy selects the best action from multiple possibilities for any given observation, helping humanoid robots react quickly and accurately in various situations.

- Advanced Level: The paper describes how Choice Policy uses neural networks to efficiently capture multimodal behaviors, allowing for fast inference and effective control over complex manipulation tasks. This approach outperforms traditional methods like diffusion policies or behavior cloning.

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

Humanoid robots have the potential to perform complex tasks in human-centric, unstructured environments. To succeed in such settings, they must coordinate their head, hands, and body to actively search for, locate, grasp, and manipulate objects . Achieving this level of dexterity and flexibility, however, remains highly challenging. It requires seamless whole-body coordination and the tight integration of locomotion and manipulation.

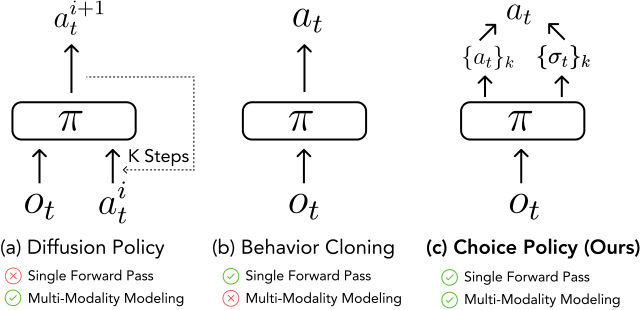

One widely used approach for acquiring new robot skills is learning from demonstrations (LfD). This approach typically involves a human teleoperator controlling the robot’s arms and hands via cameras, motion capture, or Virtual Reality (VR) interfaces to collect expert trajectories, which are subsequently used for supervised imitation learning. However, this approach has several challenges. First, integrating all components is difficult: while some systems incorporate hand-eye coordination , upper-lower body coordination, or waist movement individually, combining them all becomes increasingly complex. Second, existing LfD methodologies often face a trade-off between efficiency and expressiveness: they either rely on iterative computation, which is too slow for the real-time demands of adaptive loco-manipulation, or utilize architectures that are insufficiently expressive to capture the multimodal nature of human demonstrations.

In this paper, we present a system for collecting high-quality demonstrations of coordinated humanoid head, hand, and leg movements. By leveraging this system, we are able to collect high-quality real-world data for complex tasks. We then introduce a novel framework for learning autonomous skills from this dataset. Our method, Choice Policy, captures the multimodal behaviors present in demonstrations without relying on diffusion models or prior tokenization. This approach enables efficient whole-body control through a single forward pass of a neural network.

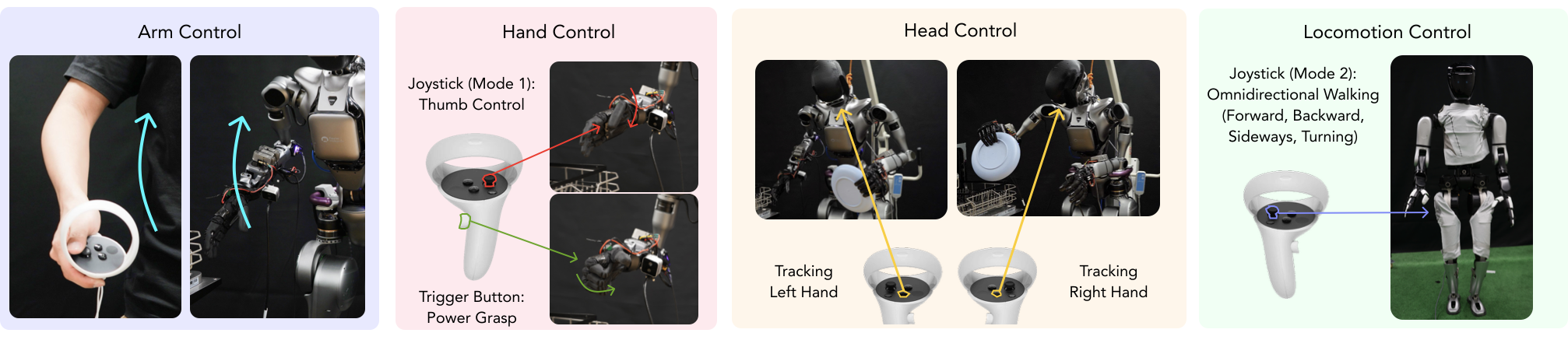

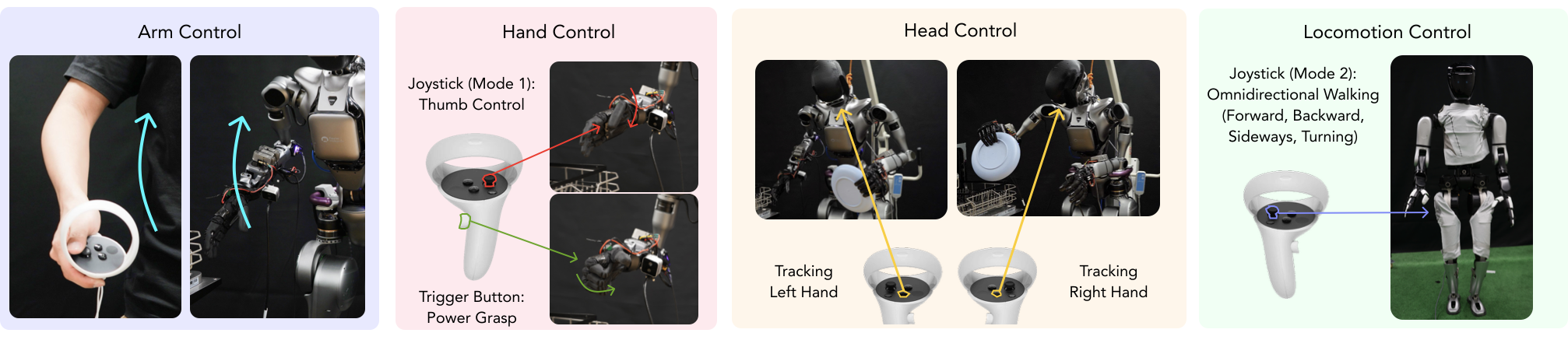

Teleoperation Interface. To overcome the complexity of full-body humanoid control, we developed a modular teleoperation interface designed for both intuitiveness and versatility. Instead of requiring the operator to manage every degree of freedom simultaneously, our system decomposes control into a set of functional submodules. This modularity does not limit the robot’s expressive range; instead, it provides a powerful abstraction that allows the user to focus on high-level task logic.

Specifically, our system utilizes a VR controller as the primary input device. The controller’s pose changes are mapped directly to the arm’s end-effector pose. The controller buttons are used to manage atomic grasp types: the four non-thumb fingers are actuated as a single group, while the thumb moves independently. For hand-eye coordination, the user can activate a mode where the head tracks either the left or right hand, reflecting the fact that many manipulation tasks require close hand-object interaction. Finally, the user can use the joystick to command locomotion by leveraging a base policy trained via reinforcement learning (RL) in simulation .

This design provides several advantages. First, the teleoperator can actively select and switch between specific skills instead of continuously mirroring the robot’s full pose, which greatly reduces physical fatigue. Second, by simplifying hand movements into precision and power grasps, the system covers a broad range of manipulation skills while making data collection significantly less demanding. Furthermore, this modular abstraction is not limiting. The interface is designed to be extensible, allowing for the integration of more complex skills such as finger gaiting in the form of additional submodules, as shown in .

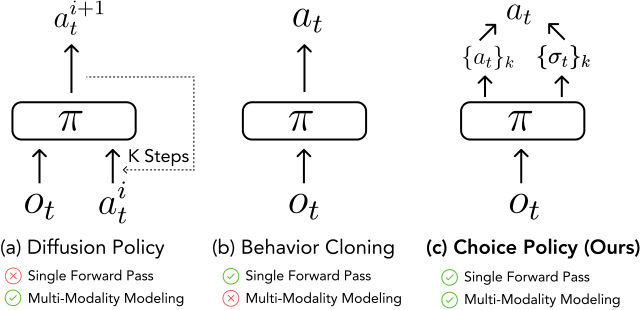

Policy Learning. The collected demonstrations are inherently multimodal due to the variations and preferences of the teleoperator. While diffusion policies are a popular solution, their inference speed is often too slow for real-time reactive manipulation. These methods frequently require additional optimization or involve a trade-off between fast responsiveness and smooth motion . Behavior cloning can achieve fast control, but it often struggles to capture the multimodal nature of manipulation. To address this, we propose Choice Policy, which is inspired by multi-choice learning literature . This approach generates multiple predictions for a given observation, combining the efficiency of a single forward pass with the ability to model multimodality.

During inference, the Choice Policy outputs $`K`$ candidate action sequences, each with an associated score. The action with the highest score is selected for execution. During training, the score network is supervised to predict the overlap between each proposal and the ground-truth action, which is measured as the negative mean squared error (MSE). The action proposal network is trained using a winner-takes-all paradigm where only the proposal with the smallest MSE is updated through backpropagation. This method enables the policy to capture multimodal behaviors in the dataset while maintaining fast inference speeds.

Results. We evaluate our approach on two tasks that highlight the importance of coordinated control for humanoid robots: (1) dishwasher loading and (2) whole-body loco-manipulation for whiteboard wiping. In the dishwasher loading task, the robot’s head must actively shift its gaze from the handover position to the insertion position. In the loco-manipulation task, the robot must maintain stable walking gaits while adapting to errors caused by imprecise initial and final positions.

We conduct comprehensive real-world experiments to study the effects of hand-eye coordination and the proposed Choice Policy algorithm. Our results show that the Choice Policy consistently outperforms both diffusion policy and behavior cloning with action chunking. We further perform ablation studies demonstrating that learned score-based selection is significantly more effective than baselines.

Related Works

Humanoid locomotion and manipulation have been studied extensively for several decades; we refer the reader to recent surveys for a comprehensive overview . In this section, we focus our discussion on comparing our approach with existing literature regarding humanoid teleoperation and policy learning.

Humanoid Manipulation

Because humanoids share a similar morphology with humans, a common strategy involves retargeting human movements to robots via keypoint matching. This area has progressed significantly in recent years. ExBody decouples upper-body motion tracking from lower-body stability control to demonstrate expressive robot dancing. Subsequent work has further improved motion tracking capabilities by demonstrating agile humanoid movement , extreme balance motion , and more general reference tracking .

Combined with advancements in computer vision for human pose estimation, these motion tracking capabilities provide a versatile interface for humanoid teleoperation. Early works such as H2O , OmniH2O , and HumanPlus utilize human keypoints as input and convert them into physically plausible robot control commands learned via sim-to-real transfer. TWIST employs motion capture devices to improve keypoint estimation accuracy, while Sonic demonstrates system-level improvements that result in smooth and robust behavior.

/>

/>

However, due to retargeting errors, it remains difficult to teleoperate manipulation tasks using only keypoint reference tracking. Alternatively, recent work has explored using Virtual Reality (VR) devices to control humanoid robots by applying whole-body inverse kinematics to the remaining joints, which provides accurate wrist and hand pose information . Despite this progress, simultaneously controlling all degrees of freedom remains challenging. Most existing systems either control only the upper body or lack active head control. These limitations make data collection difficult, and as a result, learning autonomous policies that can coordinate the head, hands, arms, and legs remains an open problem. For example, Open-Television learn manipulation policies for upper body only and HumanPlus learns decoupled upper and lower body motions. While AMO demonstrates an autonomous policy for whole-body manipulation, their experiments utilize the Unitree G-1 platform, which is a half-sized humanoid where balancing and control are less demanding. HOMIE also decouples locomotion from upper-body teleoperation, but it utilizes a simpler gripper and demonstrates less complex tasks that lack bimanual coordination or integrated loco-manipulation.

In contrast, our approach provides full-body teleoperation by decomposing coordination into modular sub-skills, including hand-eye coordination, arm tracking, hand grasps, and locomotion. This modularity simplifies both teleoperation and data collection. The resulting high quality demonstrations enable us to train autonomous policies that achieve whole-body manipulation for a full-sized humanoid.

Policy Representations

Imitation learning is a widely used approach for acquiring skills from expert demonstrations. This paradigm includes methods such as simple behavior cloning and implicit behavior cloning . However, due to the nature of human teleoperation, where different operators possess varying preferences, multimodality presents a central challenge. Specifically, for a single observation, multiple expert actions may be valid. Diffusion-based policies address this issue by modeling distributions over actions, but their sampling-based inference is often too slow for the real-time requirements of humanoid control . Conventional behavior cloning offers fast inference through a single forward pass, but it frequently collapses multimodal data into an average, which often leads to suboptimal or unstable actions.

Recent work has attempted to mitigate this limitation by discretizing action spaces or introducing tokenized representations . However, these methods have not yet demonstrated strong performance on high-degree-of-freedom humanoids that require tight whole-body coordination. In contrast, our approach produces multiple proposals and learns to select among them efficiently. This framework preserves fast inference while capturing the multimodal behaviors necessary for complex manipulation tasks.

Modular Teleoperation Interface

Our teleoperation system is illustrated in Figure 1. Teleoperating a humanoid for precise manipulation is inherently challenging due to the need for whole-body coordination across high-dimensional action spaces. To simplify control, we decompose humanoid manipulation into four modular skills: 1) hand-eye coordination, 2) hand-level atomic grasps, 3) arm end-effector tracking, and 4) omnidirectional walking and standing. While our upper-body design is inspired by HATO , our design of head control and lower-body locomotion introduces novel capabilities for integrated loco-manipulation. Although these modules simplify data collection, they are ultimately unified into a single data-driven policy as described in Section 4.

Arm Control. Similar to HATO , arm control is activated only when the trigger button is pressed. We refer to this as on-demand activation: at each control step, the VR controller’s relative pose change is transformed into the robot’s frame, from which the absolute end-effector pose is computed. We use inverse kinematics to solve for the target joint positions, which are sent to the humanoid for execution.

This on-demand activation is critical for collecting large-scale, precise demonstrations. Many complex tasks require the two arms to operate sequentially rather than simultaneously. Our design allows one arm to remain stationary while the other operates. This prevents the idle arm from drifting or hovering in midair, which reduces teleoperator fatigue and avoids unnecessary robot motion. Additionally, on-demand activation enables the robot to achieve larger pose changes in position or orientation. The human operator can reset and extend the controller iteratively to re-center their workspace. This allows for extended movements without needing to physically reproduce the entire motion. While such selective activation is common in industrial arm teleoperation, it has rarely been adopted for humanoid platforms.

Hand Control. The four non-thumb fingers are grouped and actuated together via the grip button, while the joystick independently controls the thumb. Both the grip button and the joystick provide continuous-valued signals that are mapped to finger actuation. This allows the operator to perform fine-grained movements and adjust the tightness of a grasp. Despite this dimensionality reduction, the essential grasp taxonomy is preserved; examples include power grasps, precision grasps, and flattening . While we currently use these atomic primitives, the framework is not limiting. These skills can be further extended to more complex behaviors. For instance, finger gaiting could be achieved by mapping additional controller inputs to specific finger coordination patterns .

This design offers two key advantages for high-quality data collection. First, it simplifies control because maintaining a stable button press is far easier for the teleoperator than maintaining a precise finger pose. Second, it improves accuracy. High-DoF finger tracking often produces jittery and unstable motions, whereas our reduced mapping yields smoother and more reliable grasps.

Hand-Eye Coordination. Most manipulation tasks are hand-centric. They require the head to maintain visibility of the active hand. For example, when the robot loads a dishwasher and inserts a plate into the dishrack, it must look at the hand to confirm that the plate is correctly aligned. Motivated by this observation, we implement a button-triggered tracking mode. Pressing the button switches the head to follow either the left or the right hand.

Specifically, let $`p_h \in \mathbb{R}^3`$ denote the 3D position of the selected hand in the robot base frame, and let $`p_{head} \in \mathbb{R}^3`$ denote the head position. The relative displacement vector is $`r=p_h-p_{head}`$. From this vector, we compute the desired yaw and pitch angles that orient the head toward the hand. The yaw is obtained as the azimuth angle in the $`xy`$-plane: $`\text{yaw} = \arctan2(r_y, r_x)`$, while the pitch is given by the elevation angle: $`\text{pitch} = \arctan2(-r_z, \sqrt{r_x^2 + r_y^2})`$. The roll angle is fixed to zero. Finally, each angle is clipped to its corresponding joint limit before being sent as a target command. This implementation ensures that the head camera continuously points toward the selected hand. Consequently, the manipulation region remains within the field of view, which reduces occlusions during long-horizon tasks.

Locomotion Policy. For tasks that require lower-body movement, we use a velocity conditioned reinforcement learning (RL) policy trained in simulation and transferred to the real robot. The policy runs at 100 Hz and takes velocity commands such as stand, walk forward, walk backward, walk sideways, and turn, each of which is parameterized by a target velocity. The RL policy outputs target joint positions that are tracked by low-level PD controllers on the robot. During teleoperation, we utilize the Quest controller’s joystick to toggle between locomotion and manipulation modes. In locomotion mode, joystick movements specify velocity commands to control the walking direction. In manipulation mode, the joystick independently controls the thumb movement. Releasing the joystick while in locomotion mode defaults the robot to the stand action. The training setup, including the reward design, domain randomization, and network architecture, follows ; detailed implementation are provided in our supplementary material.

Humanoid Platform. We use the Fourier GR-1 and Robotera Star-1 as examples to demonstrate the generality of our method. The GR-1 is a human-sized robot with a total of 32 actuated motors: 6 motors on each leg, 7 motors on each arm, 3 motors on the waist, and 3 motors on the head. It has two Psyonic Ability Hands mounted; each Ability Hand has 6 motors. In total, this system has 44 degrees of freedom (DoF), providing the flexibility to accomplish various tasks. The Star1 is another humanoid platform, featuring a head with 2 DoF, a waist with 3 DoF, 7 DoF per arm, and 6 DoF per leg. In addition, it is equipped with two XHand, each offering 12 actuated DoF without passive joints. Altogether, the Star1 has 55 actuated DoF, enabling complex whole-body motions and dexterous manipulation.

The above teleoperation primitives are designed primarily to ensure accurate demonstrations. Adopting a modular approach offers several key benefits. First, the reduced complexity makes teleoperation much easier to learn: in our experiments, users typically required less than 10 minutes of practice before they could smoothly perform complex, long-horizon tasks. Second, modularity allows us to balance usability during data collection with flexibility during learning. Although upper-body teleoperation is decomposed into modules, the final policy is a unified neural network that integrates all signals in a fully data-driven manner.

Choice Policy

An overview of our method is shown in Figure 2. Given an observation $`o_t`$, the policy outputs a set of action proposals $`\{a_t^{(k)}\}_{k=1}^K`$ together with corresponding scores $`\{\sigma_t^{(k)}\}_{k=1}^K`$. The final action is selected by choosing the proposal with the highest score. During training, the scores are learned to predict the negative mean squared error (MSE) between each candidate trajectory and the ground truth.

The policy takes as input an RGB image and proprioceptive signals; it outputs target joint positions for the arms and hands. When locomotion is involved, the policy additionally outputs high-level commands for the lower body.

Background

Imitation learning via behavior cloning (BC) is a common approach for acquiring robot skills. Given a dataset $`\mathcal{D}=\{(o_t, a_t)\}`$ of observations and demonstrated actions, the policy $`\pi`$ is trained to minimize a regression loss, typically the mean squared error (MSE):

\mathcal{L}_{\text{BC}} = \| \pi(o_t) - a_t \|^2.While effective, this approach struggles when demonstrations are multimodal. In teleoperation data, humans rarely repeat identical trajectories; therefore, multiple different actions may be valid for the same state. Naively minimizing MSE with a deterministic policy usually causes the model to average across these actions, often producing unrealistic or suboptimal behaviors.

To address this, diffusion policies and their variants train generative models that better capture multimodal distributions. This results in a more expressive policy class, but it comes at the cost of slow inference, making real-time control difficult. Although alternative methods exist , they typically involve a trade-off between accuracy and computational speed.

In this section, we present an alternative algorithm motivated by multiple-choice learning for structured prediction problems . These problems require a model to output multiple valid hypotheses given a single input. In computer vision, this approach is utilized by SAM , where a network predicts multiple possible segmentation masks for a single user click to resolve spatial ambiguity. Similarly, learning from teleoperation data is inherently ambiguous; a single visual observation often corresponds to several valid expert behaviors in the training data. Motivated by these designs, our approach predicts multiple candidate action trajectories along with a score that ranks them, effectively capturing this behavioral diversity without the computational overhead of iterative sampling.

/>

/>

Policy Architecture.

Our model consists of a feature encoder, an action proposal network, and a score prediction network. The feature encoder maps visual observations and proprioceptive inputs into a single vector representation. The action proposal network then takes this feature and predicts a set of candidate action trajectories. In parallel, the score prediction network takes the same feature as input and outputs a score for each trajectory.

Observation Encoder. We use two types of observations: visual inputs (RGB and depth) and proprioceptive signals. For RGB, we adopt a frozen DINOv3 feature encoder . For depth, we use a randomly initialized ResNet-18 trained from scratch, with all batch normalization layers replaced by group normalization as in . For proprioception, we use a 3-layer MLP with ReLU activations. Not all tasks use the same set of observation modalities, but all comparisons and baselines are given access to the same information with the same encoder design. The features from different modalities are then concatenated to form the final feature vector $`\mathbf{f}_t`$.

Action Proposal Network. We then pass the feature vector $`\mathbf{f}`$ to an action proposal network. Different from typical action prediction, we predict a set of candidate actions $`\{\mathbf{a}_k\}_{k=1}^{K}`$. Each $`\mathbf{a}`$ is a multi-step prediction, following the practice of , therefore $`\mathbf{a}_t \in \mathbb{R}^{T \times |A|}`$, where $`|A|`$ is the action dimension. In practice, we use a two-layer MLP with an output channel size $`|K| \times |T| \times |A|`$ and reshape it to the desired dimension.

Score Prediction Network. To select the best action, we must also predict the quality of each candidate trajectory. Similar to , which predicts the score of each segmentation by estimating its intersection-over-union (IoU) with the ground truth, our approach predicts the MSE between each action trajectory and the ground-truth trajectory. We implement this using a two-layer MLP that outputs $`|K|`$ channels, where each channel represents the score of one action trajectory.

# N: batch size

# K: number of proposals

# T: action prediction horizon

# x: input features with shape [N, K, A, T]

scores = score_pred(x) # [N, K]

actions = action_proposal(x)

score_idx = scores.argmin(dim=1)

if train: # training

gt = gt[:, None].repeat(1, K, 1, 1) # [N, K, A, T]

loss = mse(gt, pred_action).mean(dim=(2, 3))

score_loss = ((scores - loss.detach()) ** 2).mean()

action_loss = loss[torch.arange(loss.shape[0]), loss_mask].mean()

loss = action_loss + score_loss

return loss

else: # inference

actions = actions[torch.arange(N), score_idx]

return actionsTraining Objective

During training, the policy outputs $`K`$ candidate action trajectories $`\{a_t^{(k)}\}_{k=1}^K`$ and a set of predicted scores $`\{\sigma_t^{(k)}\}_{k=1}^K`$. We first compute the mean squared error (MSE) between each proposal and the ground-truth trajectory $`a_t`$, averaged over action dimensions and the prediction horizon:

\ell^{(k)} = \frac{1}{|A||T|} \sum_{i=1}^{|A|} \sum_{j=1}^{|T|}

\big(a_t^{(k)}[i,j] - a_t[i,j]\big)^2.These per-proposal errors $`\{\ell^{(k)}\}`$ serve two purposes. First, they are used as regression targets for the score prediction network:

\mathcal{L}_{\text{score}} = \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^K

\big(\sigma_t^{(k)} - \ell^{(k)}\big)^2.Second, we adopt a winner-takes-all strategy for updating the action proposal network. The proposal with the smallest error is selected: $`k^\star = \arg\min_{k} \ell^{(k)}`$, and only this winning trajectory $`a_t^{(k^\star)}`$ receives gradients. The corresponding action loss is $`\mathcal{L}_{\text{action}} = \ell^{(k^\star)}`$.

The final training loss combines these two terms: $`\mathcal{L} = \mathcal{L}_{\text{action}} + \mathcal{L}_{\text{score}}`$. This encourages the proposal network to generate diverse candidates while the score network learns to approximate their true quality. This enables the policy to efficiently select the best trajectory during inference time.

Inference

At inference time, the policy generates $`K`$ candidate trajectories in a single forward pass. The score prediction network assigns a score to each proposal, and the trajectory with the lowest predicted error is selected for execution:

a_t = a_t^{(k^\star)}, \quad

k^\star = \arg\min_{k} s_t^{(k)}.This procedure allows the policy to efficiently select among multiple valid behaviors. It preserves the fast inference speed of behavior cloning while effectively handling multi-modality. To demonstrate that our approach is simple to implement, we provide the PyTorch pseudocode in Figure 3.

Experiments

We evaluate our approach on two tasks: (1) Dishwasher Loading and (2) Loco-Manipulation Wiping. The dishwasher loading task is used to test the effectiveness of our learning algorithm, the quality of the teleoperation system, and the importance of hand-eye coordination, as well as to conduct ablation studies. The more challenging loco-manipulation wiping task serves as a demonstration of the flexibility of our teleoperation system and shows that our policy learning methods can extend to more complex, long-horizon tasks.

Dishwasher Loading

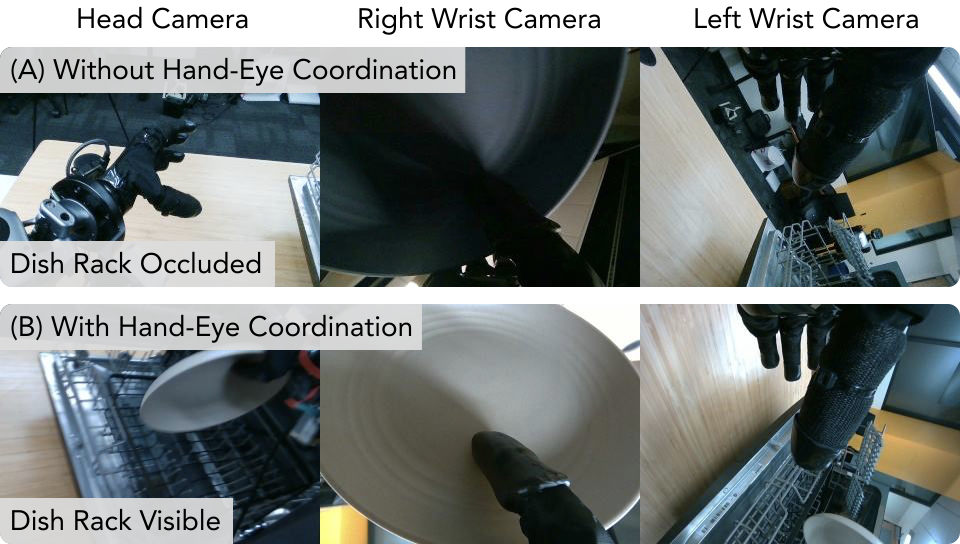

Task Setup. At the start of each trial, a plate is placed near the edge of a table in front of the robot. Because the plate is thin and cannot be grasped directly from the top, the robot must leverage environmental contacts. It first slides the plate closer to the edge to avoid finger-table collisions and then grasps it securely. The plate is subsequently handed over from one hand to the other before being inserted into the dishrack inside the dishwasher. Since the dishwasher is not initially visible from the head camera and the wrist camera becomes occluded by the plate, the robot must actively adjust its head to track the manipulating hand. Without proper head control, the dishrack cannot be observed.

This task is particularly challenging for two reasons. First, the thin plate requires the use of environmental support, such as sliding along the table surface, to achieve a stable pickup. Second, the task is long-horizon and composed of three tightly coupled sub-skills: pickup, handover, and insertion. In this sequence, failure at any stage leads to overall failure. These factors underscore the need for reliable coordination across subsystems and robust handling of multi-modality in demonstrations.

We demonstrate this task using the Fourier GR-1 humanoid robot. To isolate the effect of hand-eye coordination, we minimize the influence of locomotion and lower-body movement by mounting the robot on a fixed shelf during this experiment. We collect 100 demonstrations for this task.

/>

/>

Inputs. In this task, we use the RGB camera on the robot’s head as well as two cameras mounted on the wrists. We also include the joint positions of the upper body and hands, which results in a 29-dim proprioceptive input vector.

Main Results. Table [tab:dishwasher] compares our method with behavior cloning (BC) and Diffusion Policy (DP). All approaches perform reliably during the pickup stage. However, both BC and DP succeed in only about 70% of handovers, reflecting the difficulty of modeling multiple valid handover strategies. Their performance drops further during insertion, with success rates of only 50%. In contrast, Choice Policy maintains high reliability throughout the sequence; it improves handover success to 90% and achieves 70% on insertion. These results indicate that Choice Policy handles multi-modality in demonstrations more effectively while retaining fast inference, leading to more consistent execution of the complete task.

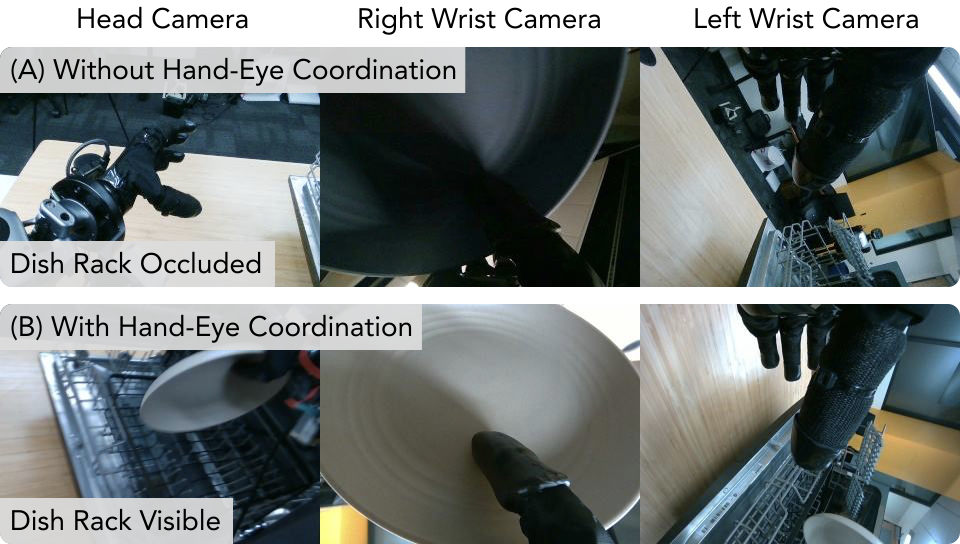

Hand-Eye Coordination. We also find that head orientation has a strong impact on task performance. Table [tab:dishwasher] shows results for cases where the head camera does not track the active hand. Without adaptive head motion, all methods still succeed in pickup but struggle in later stages. This is particularly evident during insertion, where success rates drop to nearly zero. This failure occurs because the fixed viewpoint often occludes the dishrack, preventing precise placement. By contrast, with adaptive hand-eye coordination, the robot maintains visibility of the manipulating hand throughout the task, which substantially improves performance in both handover and insertion.

Figure 4 further illustrates this effect: without coordination, the dishrack is occluded, whereas with coordination, it remains clearly visible. These results highlight that hand-eye coordination is critical for complex manipulation tasks, especially when accurate placement depends on maintaining clear visual feedback.

Out-of-Distribution (OOD) Evaluations. We further evaluate robustness under out-of-distribution conditions (Table [tab:dishwasher_ood]) across two settings: Color OOD and Position OOD. In the Color OOD setting, the robot manipulates a green plate, even though only pink, blue, and brown plates were seen during training. In the Position OOD setting, the plate is placed slightly outside the training range.

In both settings, performance drops compared to in-distribution tasks. Color variation mainly reduces insertion accuracy, while position shifts prove to be more challenging. All methods degrade significantly in the latter case; for instance, insertion success falls near zero for diffusion policy and behavior cloning. In contrast, choice policy demonstrates greater robustness by achieving higher success rates in both handover and insertion, though performance still falls short of in-distribution levels. The results highlight the difficulty of generalizing to unseen appearances and positions, while showing that our choice policy maintains comparatively strong performance.

Ablation Experiments. Since our method outputs $`K`$ candidate actions at each step, it is natural to ask how performance changes if these proposals are used differently. We evaluate three alternatives: (1) Random Choice, where one proposal is selected uniformly at random; (2) Mean Choice, where the $`K`$ actions are averaged; and (3) Single Choice, where a single proposal is used consistently across all steps. For the single-choice variant, we report both the best and worst performing heads.

As shown in Table [tab:dishwasher_ablation], all variants underperform compared to our scoring-based selection. Random choice achieves moderate pickup success but fails in later stages. Averaging proposals performs poorly because multimodal actions cannot be meaningfully averaged. Furthermore, using a fixed single head is inconsistent and results in large performance gaps between the best and worst cases. In contrast, our scoring-based method achieves high success across all stages. These results confirm that the scoring mechanism is critical, as it allows the policy to adaptively select the most suitable proposal at each step.

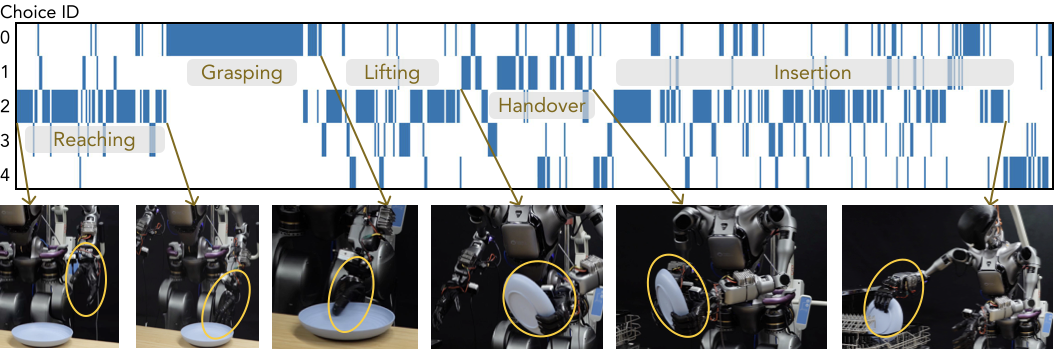

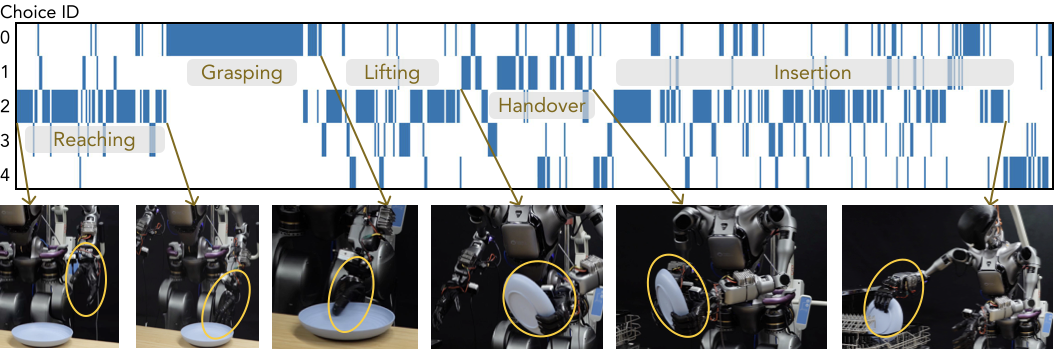

Qualitative Visualization. To better understand the internal behavior of the Choice Policy, we visualize the selection of action proposals during a full rollout of the dishwasher loading task (Figure 5). Each row represents one of the $`K=5`$ action proposals (Choice IDs), while the columns represent the progression of task phases.Interestingly, the visualization reveals that the model does not select a single head for the entire task. Instead, different proposal heads specialize in specific sub-skills. For instance, Choice ID 2 is consistently selected during the reaching and handover phases, while Choice ID 0 dominates the grasping stage. This suggests that the network naturally decomposes the long-horizon task into distinct modes, where each head learns to represent a specific portion of the behavior.

/>

/>

Whole-Body Manipulation for Whiteboard Wiping

Task Setup. In this task, a whiteboard eraser is placed at the robot’s side, outside its initial field of view. The robot must first move its head to locate the eraser and then grasp it. After pickup, the robot walks to the left toward the marked region of the whiteboard and wipes the target area clean.

This task is particularly challenging for several reasons. First, the robot’s initial pose is randomized at the start of each episode, which requires robust perception and planning. Second, locomotion introduces uncertainty because the final position after walking often deviates from the commanded target. Finally, once the robot reaches its approximate destination, it must accurately adjust its arm and body to perform effective wiping. These sources of uncertainty make the task a rigorous test of whole-body coordination. We collect 50 demonstrations for this task.

Inputs. The policy receives RGB and depth images from the head camera. Depth input is critical; we find that using RGB alone is insufficient for accurately estimating the distance to the whiteboard. Additionally, the policy receives upper-body proprioception and hand joint positions. The action space consists of target joint states for the upper body and hands, along with a low-dimensional command interface for the lower body that specifies turning, forward or backward motion, and lateral movement.

Main Results. The results are summarized in Table [tab:wiping]. We were unable to deploy Diffusion Policy because its slow inference and training instability. Both Behavior Cloning (BC) and Choice Policy successfully completed the initial head-movement stage. Choice Policy achieved higher success in grasping the eraser and demonstrated more reliable locomotion. In contrast, while behavior cloning occasionally reached the board, it often failed to perform stable wiping because of inaccurate final positioning.

Although the overall success rates are modest, this task is extremely challenging. It requires integrating perception, grasping, locomotion, and whole-body adjustment in a real-world environment. The results suggest that while current policies can handle individual stages reliably, achieving robust end-to-end success in long-horizon humanoid manipulation remains an open challenge.

Conclusion

In this paper, we presented a method for coordinated humanoid whole-body control for complex, long-horizon manipulation tasks. We introduced a modular teleoperation system that decomposes control into different modules. Furthermore, we proposed an efficient policy learning framework for learning from demonstrations that is capable of modeling multi-modality with a single forward pass. By utilizing the data collected through our teleoperation system and this policy learning framework, we demonstrated that humanoid robots can successfully perform several challenging manipulation tasks.

Limitations and Future Work. Although our approach shows promising results, several limitations remain. First, the visual perception component has limited generalization to substantially different scenes and objects. Incorporating more diverse training data or pre-training on large-scale datasets could improve robustness. Second, our current hand-eye coordination relies on a heuristic algorithm to direct the head toward the active hand. Developing a more adaptive or learned mechanism could further enhance performance. Addressing these limitations is a critical direction for enabling more reliable and versatile humanoid manipulation.

Acknowledgment

This work is supported in part by the program “Design of Robustly Implementable Autonomous and Intelligent Machines (TIAMAT)", Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency award number HR00112490425.

Appendix

Whole-body Control Framework

Our whole-body control framework consists of a 20 Hz high-level command module and a 100 Hz low-level controller. The high-level command module runs on an external workstation, while the low-level controller executes on the robot’s onboard compute. Communication between the two modules is facilitated via ROS2 over Ethernet.

The high-level commands are generated from a VR controller and include head motion, arm end-effector targets, hand states, and linear and angular velocity commands for locomotion. The low-level controller is implemented as a reinforcement-learning-based locomotion policy that is capable of maintaining balance during motion.

The low-level controller is trained in IsaacGym using the Denoising World Model Learning (DWL) approach . Our implementation follows the training procedure and design choices described in DWL while adapting the observation space and command interface to support whole-body humanoid locomotion, as detailed in Table [tab:obs_space] and Table 1. To enable the policy to learn both static standing and walking behaviors, we introduce an additional command sampling strategy in which static stand commands are sampled with a probability of 10%.

| Observation | Scaling |

|---|---|

| Commanded forward velocity | $`\times |

| \begin{cases} | |

| 1.2, & v_x \ge 0 \ | |

| 0.6, & v_x < 0 | |

| \end{cases}`$ | |

| Commanded lateral velocity | $`\times 0.3`$ |

| Commanded yaw rate | $`\times 0.3`$ |

| Lower-body joint velocity | $`\times 0.1`$ |

.

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)