Counterfactual Self-Questioning for Stable Policy Optimization in Language Models

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Counterfactual Self-Questioning for Stable Policy Optimization in Language Models- ArXiv ID: 2601.00885

- Date: 2025-12-31

- Authors: Mandar Parab

📝 Abstract

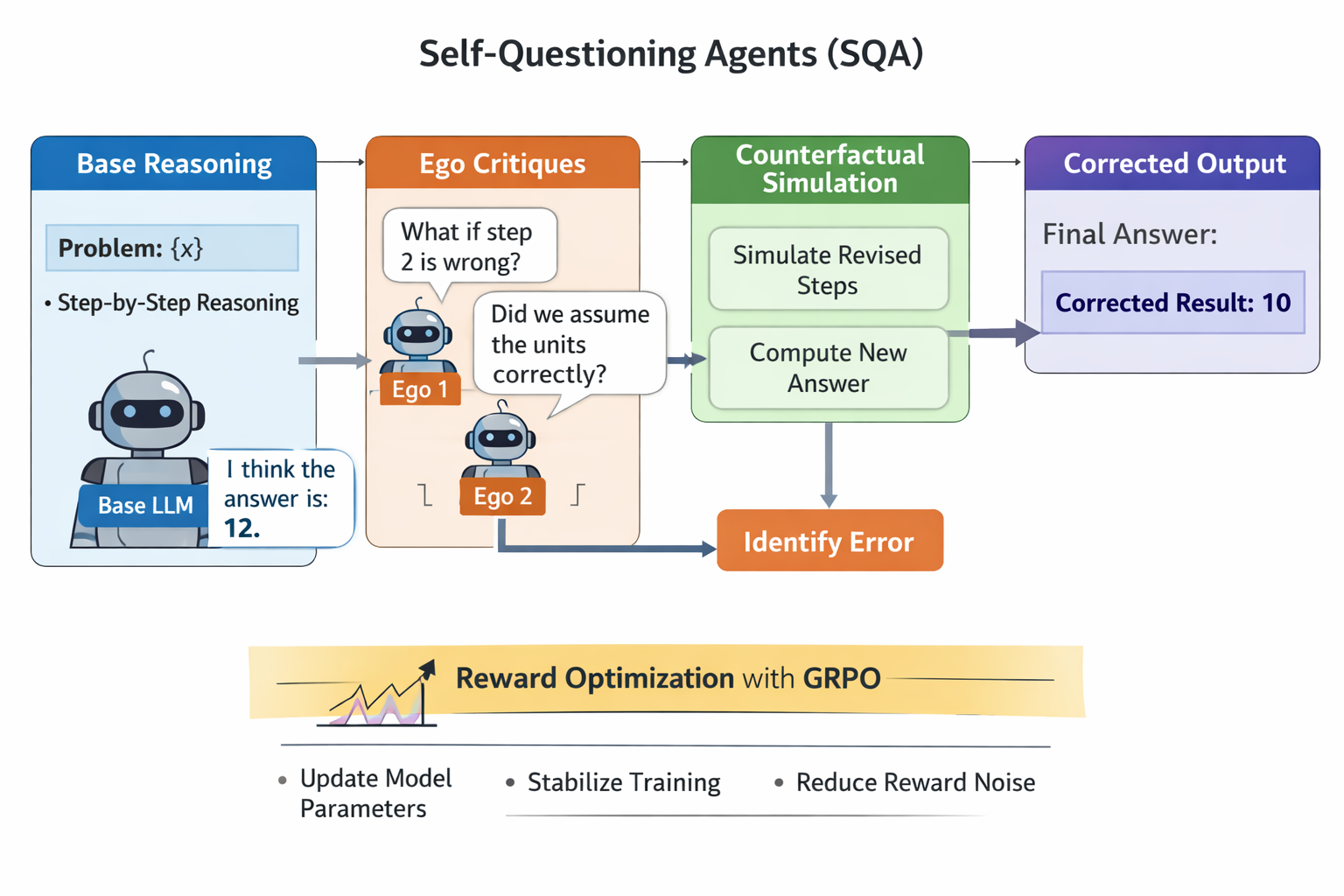

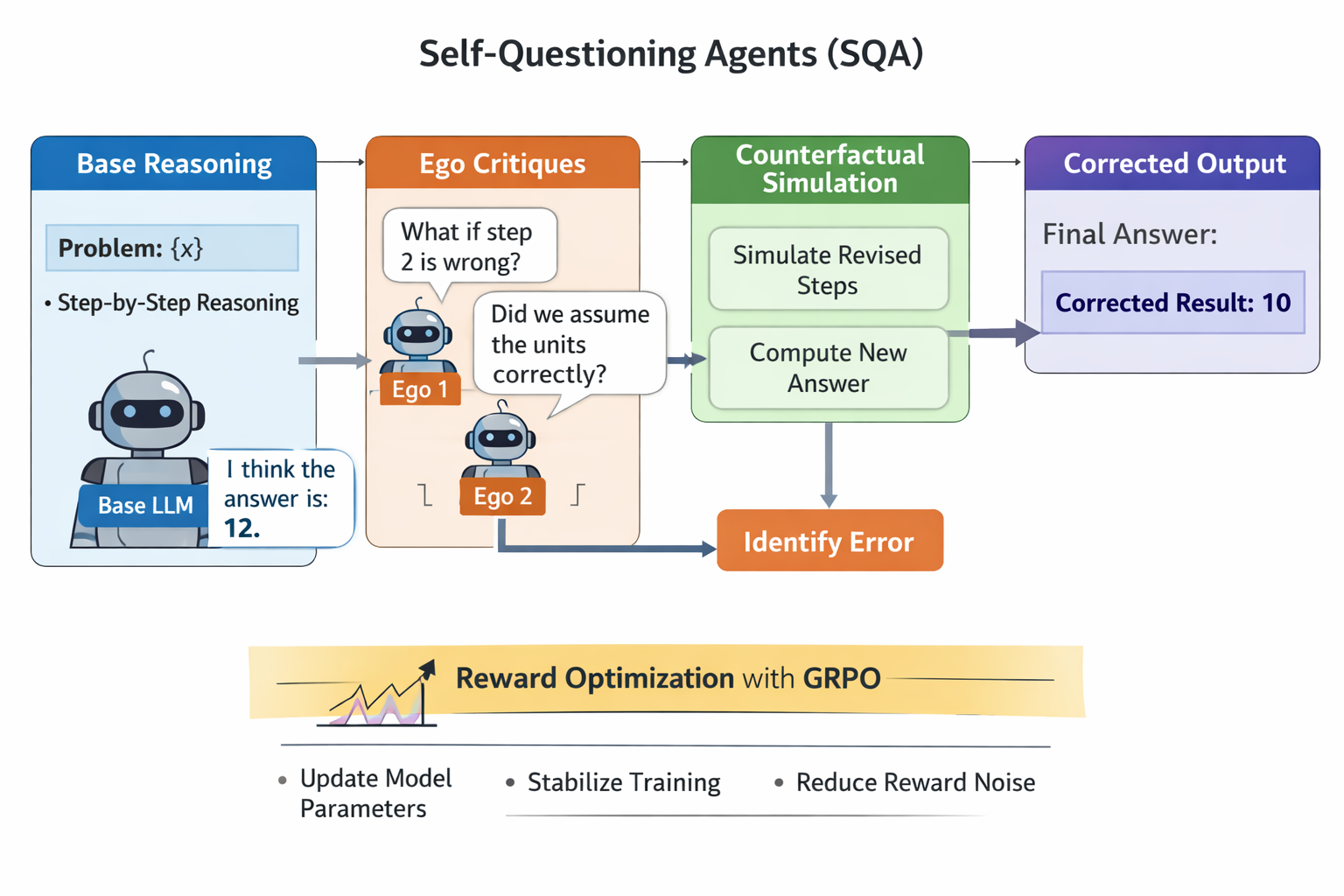

Recent work on language model self-improvement shows that models can refine their own reasoning through reflection, verification, debate, or self-generated rewards. However, most existing approaches rely on external critics, learned reward models, or ensemble sampling, which increases complexity and training instability. We propose Counterfactual Self-Questioning, a framework in which a single language model generates and evaluates counterfactual critiques of its own reasoning. The method produces an initial reasoning trace, formulates targeted questions that challenge potential failure points, and generates alternative reasoning trajectories that expose incorrect assumptions or invalid steps. These counterfactual trajectories provide structured relative feedback that can be directly used for policy optimization without auxiliary models. Experiments on multiple mathematical reasoning benchmarks show that counterfactual self-questioning improves accuracy and training stability, particularly for smaller models, enabling scalable self-improvement using internally generated supervision alone.💡 Summary & Analysis

1. **Counterfactual Self-Questioning: A New Paradigm for Problem Solving** - This research introduces a method where language models can generate and evaluate alternative scenarios of their own reasoning process, much like asking themselves "what if this step was wrong?" to identify potential errors.-

GRPO: The Stable Foundation for Policy Optimization

- Counterfactual Self-Questioning uses multiple inference trajectories generated by the model itself, compared using Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) to create learning signals and optimize policies stably.

-

The Power of Internal Review: Improving Performance Without External Critics

- The method enables internal review without relying on external critics or large ensembles, making it particularly useful in scenarios where such dependencies are impractical.

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) have achieved strong performance on mathematical and logical reasoning tasks when equipped with structured prompting techniques such as chain-of-thought , step-wise verification , and domain-specific training . Despite these advances, LLM reasoning remains brittle: small errors in intermediate steps often propagate, models exhibit overconfident hallucinations, and failures are difficult to detect without external verification . Improving reasoning reliability therefore requires mechanisms that expose and correct internal failure modes rather than relying solely on final-answer supervision.

Recent work explores whether LLMs can improve themselves through internally generated feedback. Approaches such as Reflexion , STaR , Self-Discover , debate , and self-rewarding language models demonstrate that models can iteratively refine their reasoning. However, these methods typically rely on external critics, multi-agent debate, extensive sampling, or auxiliary verifier models, increasing computational cost and architectural complexity.

In contrast, human reasoning often relies on targeted counterfactual interrogation such as asking whether a particular step might be wrong and exploring the consequences before committing to a conclusion. This suggests an alternative paradigm for LLM self-improvement one based on internally generated counterfactual critique rather than external verification.

In this paper, we introduce Counterfactual Self-Questioning, a framework in which a single language model generates and evaluates counterfactual critiques of its own reasoning. Given an initial chain-of-thought solution, the model produces targeted “What if this step is wrong?” probes, simulates alternative reasoning trajectories, and uses the resulting signals to refine its policy. Counterfactual critiques are generated by lightweight ego critics that share parameters with the base model and introduce no additional learned components.

Our approach differs from prior self-improvement methods in three key ways. First, critique is generated from a single policy rollout rather than from ensembles, external critics, or stored successful trajectories. Second, counterfactual reasoning is applied within the model’s own reasoning trajectory rather than at the input or data level. Third, the resulting critiques are converted into structured learning signals using Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) , enabling stable policy updates without a learned value function.

We evaluate Counterfactual Self-Questioning on established mathematical reasoning benchmarks, including GSM8K , MATH , and Minerva-style quantitative reasoning tasks . Across four model families and multiple capacity regimes, the proposed method improves accuracy over standard chain-of-thought baselines, with the largest gains observed for small and medium-sized models. Ablation studies show that one or two counterfactual critics provide the best balance between critique diversity and optimization stability.

In summary, this work makes the following contributions:

-

We propose Counterfactual Self-Questioning, a verifier-free framework for improving LLM reasoning via internally generated counterfactual critique.

-

We introduce a simple training and inference pipeline that converts counterfactual critiques into structured policy optimization signals using GRPO.

-

We demonstrate consistent improvements on GSM8K, MATH, and Minerva-style tasks across multiple model sizes, with detailed analysis of stability and scaling behavior.

Related Work

Our work relates to prior efforts on improving language model reasoning through self-improvement, verification, multi-agent feedback, counterfactual reasoning, and reinforcement learning with model-generated signals. We position Counterfactual Self-Questioning as a method for constructing an internal, trajectory-level policy optimization signal that complements existing approaches.

Self-Improvement and Iterative Reasoning:

Several methods explore whether language models can improve their own reasoning using internally generated feedback. Reflexion introduces memory-based self-correction, STaR bootstraps improved policies from model-generated correct solutions, and Self-Discover synthesizes new reasoning strategies through internal feedback. Self-consistency sampling reduces variance by aggregating multiple reasoning paths. These approaches typically rely on extensive sampling, replay buffers, or external filtering. In contrast, Counterfactual Self-Questioning generates critique from a single policy rollout by probing alternative counterfactual trajectories, avoiding reliance on large ensembles or stored solutions.

Verification, Critics, and Debate:

Another line of work reduces hallucinations through explicit verification. Chain-of-Verification (CoVe) and step-wise verification validate intermediate reasoning, often using separate verifier models. Debate-based methods and model-based critics expose errors through adversarial interaction, while Constitutional AI uses predefined principles to guide self-critique. These approaches introduce additional models, agents, or rules. By contrast, Counterfactual Self-Questioning distills critique into a single-policy setting where counterfactual probes act as an implicit internal opponent without auxiliary components.

Counterfactual Reasoning:

Counterfactual reasoning has been widely used to improve robustness and causal generalization in NLP. Counterfactual data augmentation encourages models to capture causal structure rather than spurious correlations . Counterfactual thinking also underlies logical reasoning tasks that require evaluating alternative hypotheses. Our work differs in applying counterfactual reasoning within the model’s own reasoning trajectory rather than at the input or data level, enabling introspective error discovery during inference and training.

Reinforcement Learning and Self-Generated Rewards:

Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) and policy optimization methods such as PPO are central to modern LLM training. Recent work shows that models can generate their own reward signals , while Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) provides a stable framework for learning from relative feedback. Counterfactual Self-Questioning complements this line of work by producing structured, trajectory-level feedback that can be directly integrated into GRPO-style optimization.

Evaluation Benchmarks:

Mathematical reasoning benchmarks such as GSM8K , MATH , and Minerva-style datasets are standard for evaluating reasoning quality. While scaling laws highlight the role of model capacity, structured reasoning methods such as chain-of-thought prompting demonstrate that reasoning strategy and error mitigation are equally important. Our evaluation follows this established protocol.

Across prior work, the use of internally generated counterfactual probes as a unified learning signal remains underexplored. Existing methods emphasize reflection, verification, debate, or reward modeling, but do not systematically generate and resolve counterfactual alternatives to the model’s own reasoning trajectory. Counterfactual Self-Questioning fills this gap by introducing a single-policy mechanism that produces structured counterfactual feedback usable for both inference and policy optimization, offering a lightweight and scalable alternative to external critics.

Methodology

We propose Counterfactual Self-Questioning (CSQ), a training and inference framework in which a single language model generates and evaluates counterfactual critiques of its own reasoning. CSQ does not rely on external critics, auxiliary reward models, or multi-agent debate. Instead, it constructs a structured policy optimization signal by comparing a base reasoning trajectory with internally generated counterfactual alternatives. Figure 1 illustrates the overall workflow.

Problem Setup

We consider a dataset of reasoning problems

\mathcal{D} = \{(x_i, y_i)\},where $`x_i`$ denotes an input problem and $`y_i`$ its ground-truth answer. Let $`\pi_\theta`$ denote a language model policy parameterized by $`\theta`$. Given an input $`x`$, the policy generates a reasoning trajectory followed by a final answer:

\tau^{(0)} \sim \pi_\theta(\cdot \mid x), \qquad \hat{y}^{(0)} = f(\tau^{(0)}).This base trajectory corresponds to standard chain-of-thought reasoning and is unverified.

Our goal is to improve $`\pi_\theta`$ by enabling it to identify and correct failures in its own reasoning trajectory through internally generated counterfactual feedback. Crucially, all components of CSQ share the same parameters $`\theta`$; counterfactual generation introduces no additional models or learnable parameters.

Counterfactual Self-Questioning

Given the base trajectory $`\tau^{(0)}`$, CSQ generates a set of counterfactual probes that target potential failure points in the reasoning process. Each probe is conditioned on the base trajectory and prompts the model to consider an alternative hypothesis, such as the possibility of an incorrect intermediate step or a missing constraint.

Formally, for each input $`x`$, we generate $`N_{\text{cf}}`$ counterfactual trajectories:

\tau^{(k)} \sim \pi_\theta(\cdot \mid x, \tau^{(0)}, q^{(k)}), \qquad k = 1,\dots,N_{\text{cf}},where $`q^{(k)}`$ denotes a counterfactual query derived from the base reasoning. These queries encourage the model to revise assumptions, re-evaluate computations, or explore alternative solution paths. Counterfactual trajectories are explicitly instructed to expose and repair potential errors rather than produce arbitrary disagreement.

Each trajectory $`\tau^{(k)}`$ yields a candidate answer $`\hat{y}^{(k)}`$. At inference time, the set $`\{\tau^{(0)}, \tau^{(1)}, \dots, \tau^{(N_{\text{cf}})}\}`$ can be used as a lightweight verification mechanism. During training, these trajectories form a comparison group for policy optimization.

Policy Optimization with GRPO

We optimize $`\pi_\theta`$ using Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) , which is well suited for settings where multiple trajectories are available for the same input. For each problem $`x`$, we define a trajectory group

\mathcal{G}(x) = \{\tau^{(0)}, \tau^{(1)}, \dots, \tau^{(N_{\text{cf}})}\}.Each trajectory $`\tau \in \mathcal{G}(x)`$ receives a scalar reward

R(\tau) = \alpha R_{\text{correct}}(\tau) + \beta R_{\text{repair}}(\tau)

- \gamma R_{\text{instability}}(\tau),where $`R_{\text{correct}}`$ indicates answer correctness, $`R_{\text{repair}}`$ rewards trajectories that correct errors present in the base trajectory, and $`R_{\text{instability}}`$ penalizes incoherent or internally inconsistent counterfactual reasoning.

GRPO computes a group-level baseline

b(x) = \frac{1}{|\mathcal{G}(x)|} \sum_{\tau \in \mathcal{G}(x)} R(\tau),and defines the relative advantage

A(\tau) = R(\tau) - b(x).The policy update is given by

\theta \leftarrow \theta + \eta

\mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \mathcal{G}(x)}

\left[\nabla_\theta \log \pi_\theta(\tau \mid x)\, A(\tau)\right].Because all trajectories are generated by the same policy, optimization internalizes the corrective patterns exposed by counterfactual reasoning. Over training, the base policy increasingly produces more reliable reasoning trajectories without requiring explicit counterfactual prompting at inference time.

Dataset $`\mathcal{D} = \{(x_i, y_i)\}`$, policy $`\pi_\theta`$, number of counterfactuals $`N_{\text{cf}}`$ Generate base reasoning trajectory $`\tau^{(0)} \sim \pi_\theta(\cdot \mid x)`$ Extract base answer $`\hat{y}^{(0)}`$ Generate counterfactual query $`q^{(k)}`$ conditioned on $`\tau^{(0)}`$ Generate counterfactual trajectory $`\tau^{(k)} \sim \pi_\theta(\cdot \mid x, \tau^{(0)}, q^{(k)})`$ Form trajectory group $`\mathcal{G}(x) = \{\tau^{(0)}, \dots, \tau^{(N_{\text{cf}})}\}`$ Compute rewards $`R(\tau)`$ for all $`\tau \in \mathcal{G}(x)`$ Update $`\theta`$ using GRPO over $`\mathcal{G}(x)`$

Implementation Details

In practice, we use a small number of counterfactual trajectories, $`N_{\text{cf}} \in \{1,2,3\}`$, which balances critique diversity and optimization stability. A single counterfactual trajectory often identifies isolated arithmetic errors, while two trajectories reliably expose complementary failure modes such as incorrect assumptions and missing constraints. Larger values introduce redundancy and noise, yielding diminishing returns.

We evaluate CSQ across models of varying capacity, including

Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct, Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct, Qwen2-0.5B-Instruct,

and Mathstral-7B-v0.1. Training is performed with a learning rate of

$`1\times10^{-6}`$ for 3–5 epochs, batch size 4 with gradient

accumulation of 2, and counterfactual generations capped at 256 tokens.

Across models, CSQ consistently improves accuracy by 2–10 absolute points, with the largest relative gains observed for smaller models. These results indicate that counterfactual self-questioning provides an effective and scalable internal training signal, particularly in regimes where external supervision or large ensembles are impractical.

Experiments

We evaluate Self-Questioning Agents (SQA) across multiple model scales and model families to test whether ego-driven counterfactual critique improves mathematical reasoning accuracy. Our study includes small, medium, and domain-specialized language models and emphasizes controlled comparisons against standard chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting under matched decoding settings.

Our experiments are designed to answer three questions:

-

Does ego-driven counterfactual critique improve accuracy relative to a CoT baseline?

-

How does performance change as the number of ego agents increases?

-

Can GRPO reliably absorb ego-generated critique signals into the base policy?

Unless otherwise specified, results are averaged across multiple random seeds to account for stochasticity in both generation and policy optimization.

Training Setup

We follow standard evaluation protocols for mathematical reasoning and evaluate on two widely used benchmarks:

-

GSM8K : approximately 8.5k grade-school math word problems requiring multi-step arithmetic and logical reasoning.

-

MATH : roughly 12k high-school and competition-level problems spanning algebra, geometry, number theory, and calculus.

We report most results on GSM8K, which is widely used for evaluating data-efficient reasoning and self-improvement methods and provides a relatively clean signal for reasoning improvements. We additionally run a subset of experiments on MATH to probe robustness on more challenging problems.

For both datasets, accuracy is computed by exact match between the normalized final numeric answer and the ground-truth answer (e.g., removing formatting artifacts and extraneous whitespace).

We evaluate four language models spanning a range of parameter scales and specialization levels:

-

meta-llama/Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct, representing small general-purpose models;

-

meta-llama/Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct, representing medium-scale general-purpose models;

-

Qwen2-0.5B-Instruct, a compact model with limited capacity;

-

mistralai/Mathstral-7B-v0.1, a math-specialized model trained with domain-specific data.

This set enables analysis across capacity regimes and tests whether gains persist for models already tuned for mathematical reasoning. Across all experiments, models generate up to 256 tokens per solution with temperature $`0.2`$. These decoding settings are held fixed across baselines and SQA variants to ensure fair comparison.

We evaluate multiple configurations varying the number of ego agents:

N_{\text{ego}} \in \{1, 2, 3\}.All training runs use the same hyperparameters unless otherwise stated:

-

learning rate: $`1 \times 10^{-6}`$,

-

weight decay: $`0.01`$,

-

batch size: $`4`$,

-

gradient accumulation steps: $`2`$ (effective batch size of $`8`$),

-

training epochs: $`3`$–$`5`$,

-

generation batch size for ego critiques: $`128`$.

Fine-tuning is performed using Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) , with reward shaping derived from ground-truth correctness and ego critique quality (Section 3.3). For each model, the baseline is measured using the same training pipeline but without ego-generated critiques, isolating the contribution of ego-driven self-questioning. This setup enables controlled measurement of how ego-generated counterfactual signals affect learning and final accuracy across model scales.

Baselines

We compare Self-Questioning Agents against the following baseline and our method:

-

CoT Baseline: Standard chain-of-thought prompting without explicit verification, self-questioning, or reinforcement learning. Each model generates a single reasoning trace followed by a final answer, following established practice .

-

Self-Questioning (ours): The proposed method, in which ego agents generate counterfactual critiques of the base reasoning and the model is fine-tuned using GRPO with reward shaping derived from critique quality and ground-truth supervision.

For all configurations, we run three to four random seeds. Reported numbers are averaged across seeds.

Results: Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct

Table 1 reports results for the 1B-parameter Llama model across ego configurations.

| Setting | Trained Acc. | Lift (pts) | Lift (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| $`N_{\text{ego}} = 1`$ | 35.28 | +2.25 | +6.79% |

| $`N_{\text{ego}} = 2`$ | 35.84 | +2.70 | +6.96% |

| $`N_{\text{ego}} = 3`$ | 33.43 | +0.88 | +2.65% |

Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct results on GSM8K. Baseline accuracy: 33.14%.

Ego-driven self-questioning yields consistent improvements over the CoT baseline, with best performance at one or two ego agents. Adding a third ego provides smaller gains and can reduce stability, suggesting that limited counterfactual diversity is helpful while excessive critique introduces noise that weakens the learning signal.

Results: Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct

Table 2 presents results for the 3B-parameter Llama model.

| Setting | Trained Acc. | Lift (pts) | Lift (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| $`N_{\text{ego}} = 1`$ | 59.89 | +0.18 | +0.30% |

Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct results on GSM8K.

Improvements are smaller than for the 1B model but remain positive and stable. This is consistent with prior observations that self-generated feedback yields diminishing returns as capacity increases . Larger models tend to exhibit stronger internal verification, leaving less headroom for additional critique to provide large gains.

Results: Qwen2-0.5B-Instruct

Results for the smallest evaluated model are shown in Table 3.

| Setting | Trained Acc. | Lift (pts) | Lift (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| $`N_{\text{ego}} = 2`$ | 10.84 | +2.48 | +30.20% |

Qwen2-0.5B-Instruct results on GSM8K. Baseline accuracy: 8.36%.

SQA produces a substantial relative improvement for Qwen2-0.5B, yielding a $`\sim`$30% lift over the baseline. This highlights the effectiveness of ego-generated counterfactual critique in low-capacity regimes, where errors are frequent and diverse and counterfactual probes provide informative supervision during GRPO training.

Results: Mathstral-7B

Table 4 reports results for the domain-specialized Mathstral-7B model.

| Setting | Trained Acc. | Lift (pts) | Lift (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| $`N_{\text{ego}} = 2`$ | +0.18 | +0.18 | +0.30% |

Mathstral-7B results on GSM8K.

For Mathstral-7B, which is explicitly trained for mathematical reasoning, ego-driven improvements are modest but consistent. This suggests that domain-specialized models already exhibit strong internal verification and therefore benefit less from additional counterfactual critique. Importantly, SQA does not degrade performance in this setting.

After GRPO fine-tuning, the base model improves even when ego prompting is removed at inference, indicating that counterfactual critique is internalized during training rather than functioning only as an inference-time heuristic.

Analysis

We analyze when and why ego-driven counterfactual critique improves mathematical reasoning. Across all evaluated models, three consistent trends emerge. First, introducing one or two ego critics reliably improves accuracy over standard chain-of-thought reasoning, while gains diminish or degrade beyond three egos. Second, smaller models benefit the most, whereas larger and domain-specialized models show smaller but stable improvements. Third, Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) successfully incorporates ego-generated signals when critique diversity is present but bounded.

Counterfactual critiques generated by ego agents expose distinct failure modes in the base reasoning trajectory. With one ego, critiques are precise but narrow. With two egos, critiques provide complementary coverage of errors, while additional egos increasingly introduce conflicting or unproductive counterfactuals. This explains why performance peaks at two egos and degrades when critique diversity becomes excessive.

We also observe a stability diversity tradeoff in optimization. Limited critique diversity yields weak learning signals, while excessive diversity increases reward variance and destabilizes GRPO updates. Empirically, moderate diversity leads to stable gradients and consistent improvements across runs.

Finally, scaling behavior aligns with this interpretation. Smaller models benefit more from ego-driven critique because they produce more frequent and diverse reasoning errors and lack strong internal verification. Larger and math-specialized models already perform implicit verification, leaving less headroom for additional critique.

Detailed quantitative analyses, including critique diversity metrics, error localization statistics, reward variance measurements, and extended ablations, are provided in Appendix 12.

Discussion and Future Work

This work demonstrates that a single language model can generate, evaluate, and exploit counterfactual critiques of its own reasoning without auxiliary critics, ensembles, or human-written feedback. By internalizing counterfactual self-questioning, verification becomes an intrinsic behavior that can be optimized directly through learning rather than an external post-processing step.

Most prior verification and self-improvement methods rely on external components such as separate verifier models, debate among multiple agents, or ensemble sampling . In contrast, our results show that meaningful and actionable critique can be generated internally through prompting and parameter sharing alone. Ego agents approximate the functional role of external critics while remaining computationally lightweight, suggesting that verification need not be a distinct architectural module but can emerge as a property of a single policy.

Counterfactual self-questioning differs from reflective and debate-based approaches in how critique is produced. Rather than summarizing past failures or engaging in adversarial argumentation, ego agents introduce targeted counterfactual disruptions to the base reasoning trajectory. This focus on hypothetical failure points leads to earlier error discovery and more directly usable corrective signals, which empirically translate into improved accuracy and stable optimization, particularly for small and medium-capacity models.

Across experiments, smaller models benefit disproportionately from ego-driven critique, with large relative gains for models in the 0.5B–1B range and modest gains for larger or domain-specialized models. This mirrors trends observed in STaR, Self-Discover, and self-rewarding language models , where structured self-generated supervision is most effective when internal verification is weak. Larger models already perform implicit verification, leaving less headroom for additional critique.

From a learning perspective, counterfactual self-questioning can be viewed as structured augmentation over the reasoning space rather than the input space. Ego agents generate alternative reasoning trajectories that revise equations, assumptions, or intermediate steps, resembling counterfactual data augmentation but applied online and directly to chains of thought.

Our analysis highlights a tradeoff between stability and diversity. One ego provides precise but narrow feedback, while two egos maximize useful disagreement. Additional egos increase diversity but introduce variance that degrades the reward signal and destabilizes GRPO. Effective self-critique therefore requires bounded diversity, a consideration that will be critical for scaling self-improving systems.

Beyond mathematical reasoning, counterfactual self-questioning suggests a general design pattern for agentic systems. Ego critics could probe unsafe reasoning paths, challenge fragile assumptions in long-horizon plans, or question tool-use decisions before execution. The lightweight, model-internal nature of the mechanism makes it well suited for integration into planning agents, retrieval-augmented generation pipelines, and tool-augmented workflows.

Several directions for future work remain open. Ego agents in this study generate single-hop counterfactuals; extending them to multi-hop or tree-structured reasoning may enable deeper error correction. Learning specialized or adaptive critics, or invoking ego critique selectively based on uncertainty, could further improve efficiency and stability. Combining counterfactual self-questioning with external tools such as symbolic solvers or execution environments is another promising direction.

Overall, counterfactual self-questioning points toward language models that do not merely generate answers but actively interrogate and refine their own reasoning. The results suggest that meaningful self-improvement is possible using a single model and its own reasoning traces, providing a foundation for more robust and autonomous reasoning systems.

Additional analyses and exploratory results are provided in the Appendix.

Conclusion and Limitations

We introduced Counterfactual Self-Questioning, a lightweight framework in which a single language model generates counterfactual critiques of its own reasoning and uses the resulting trajectories as a structured signal for policy optimization. By probing potential failure points through internally generated counterfactuals, the model learns to identify fragile steps, repair faulty reasoning, and produce more reliable solutions without relying on external critics, ensembles, or auxiliary verifier models.

Across four model families and multiple capacity regimes, counterfactual self-questioning consistently improves mathematical reasoning accuracy, with the largest gains observed for small and medium-sized models that lack strong internal verification. Our experiments and analyses show that one or two counterfactual critics strike an effective balance between critique diversity and optimization stability, while larger numbers introduce noise that degrades learning. Despite its simplicity, the approach is single-model, parameter-efficient, and verifier-free, yet captures many of the benefits associated with reflective, debate-based, and self-rewarding methods.

At the same time, the method has important limitations. Because counterfactual critics share parameters with the base policy, effectiveness depends on model capacity. Very small models often struggle to generate informative critiques, while large or domain-specialized models already perform substantial implicit verification and therefore exhibit limited headroom for improvement. As a result, the approach is most effective in an intermediate regime where reasoning errors are frequent but amenable to correction.

Training stability further depends on bounded critique diversity and careful reward shaping. Increasing the number of counterfactual trajectories improves coverage only up to a point; beyond one or two critics, counterfactuals increasingly conflict or drift, introducing variance that destabilizes GRPO updates. Ego-generated critiques may also drift semantically, for example by assuming nonexistent errors or altering problem constraints, particularly for smaller models. While reward shaping mitigates these effects, counterfactual drift remains an inherent limitation of model-generated supervision.

Finally, counterfactual self-questioning introduces additional computational overhead during training due to multiple forward passes per example and has been evaluated primarily on mathematical reasoning benchmarks. Its effectiveness for other domains, such as planning, code generation, commonsense reasoning, or safety-critical tasks, remains an open question. Moreover, ego critiques in this work are single-hop and probabilistic rather than formal or multi-step verifications, limiting guarantees in high-stakes settings.

Overall, counterfactual self-questioning demonstrates that meaningful self-improvement can emerge from a single model interrogating its own reasoning traces. While further work is needed to improve robustness, adaptivity, and domain generality, these results suggest a promising direction for building more reliable and self-correcting language models using internal counterfactual feedback.

Appendix

This appendix provides supporting experimental details, extended analyses, ablations, and implementation specifics referenced in the main paper. All material here complements the main text and is included to support reproducibility and transparency.

Prompt Templates

This section documents the exact prompts used for base reasoning, counterfactual self-questioning, and critique generation. All prompts were fixed across experiments.

Base Chain-of-Thought Prompt

You are a helpful reasoning assistant. Solve the problem step-by-step.

Show your reasoning before giving the final answer.

Problem: {x}

Counterfactual Self-Questioning Prompt

The following is a solution produced by another model:

Solution:

{r}

Ask a precise "What if this step is wrong?" question.

Identify the earliest likely incorrect step and describe

how the reasoning would change under this counterfactual.

Counterfactual Critique Prompt

Given your current explanation {explanation}, check whether it is correct.

If not then, how will you solve this question: {question} differently?

First, provide a step-by-step explanation for how to solve it.

Answer Extraction and Formatting Instructions

To reduce variance due to formatting, we append the following instruction to all generation prompts:

Return the final answer on a new line in the format:

Final Answer: <answer>

During evaluation, we extract the substring following “Final Answer:” and apply normalization described in Appendix 11.1.

Reward Definition and Selection Rules

This section specifies the reward components and the selection mechanism used in training and inference.

Reward Components

Each trajectory $`S`$ receives a scalar reward:

R(S) = \alpha R_{\text{correct}}(S) + \beta R_{\text{critique}}(S) - \gamma R_{\text{drift}}(S).-

Correctness: $`R_{\text{correct}}(S)=\mathbb{I}[\hat{y}(S)=y]`$ using normalized exact match (Appendix 11.1).

-

Critique utility: $`R_{\text{critique}}(S)`$ rewards counterfactual trajectories that (i) differ from the base when the base is incorrect, and (ii) produce a correct answer. In practice, we use:

MATHR_{\text{critique}}(S_k)=\mathbb{I}[\hat{y}_0\neq y]\cdot \mathbb{I}[\hat{y}_k=y].Click to expand and view more -

Counterfactual drift: $`R_{\text{drift}}(S)`$ penalizes trajectories that change the problem semantics or introduce inconsistent assumptions. We approximate drift with simple heuristics (e.g., missing “Final Answer” line, non-numeric output on GSM8K, contradiction with stated probe, or degenerate outputs).

Trajectory Selection Rule

During inference, we choose among $`\{\hat{y}_k\}`$ using a lightweight rule: (i) if any ego produces a consistent corrected solution (passes internal consistency checks), select the most common answer among the consistent set; else (ii) fallback to the base answer. We also report an ablation that selects by majority vote over all candidates.

Training Configuration

Unless otherwise stated, all experiments use the following configuration:

-

Optimizer: AdamW

-

Learning rate: $`1 \times 10^{-6}`$

-

Weight decay: 0.01

-

Batch size: 4

-

Gradient accumulation steps: 2

-

Epochs: 3–5

-

Max new tokens: 256

-

Generation batch size: 128

-

Reward aggregation: GRPO-style group baseline

Training was conducted on NVIDIA A100 or L4 GPUs depending on model size.

Evaluation Protocol

Answer Normalization

For GSM8K and related tasks, we normalize extracted answers by: stripping whitespace, removing commas in numerals, converting common fractions/decimals where applicable, and extracting the last valid numeric token if multiple candidates appear.

Decoding Settings

Unless otherwise stated: temperature $`0.2`$, max new tokens $`256`$. We use the same decoding settings for baselines and our method.

Extended Analysis

This section provides detailed quantitative analyses supporting high-level observations in the main paper, including critique diversity, error localization, reward variance, and scaling behavior.

Critique Diversity and Disagreement Rates

We quantify critique diversity using pairwise cosine similarity between sentence-level embeddings of ego-generated counterfactual critiques. Lower similarity indicates broader exploration of the counterfactual space.

For Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct:

-

$`N_{\text{ego}} = 1`$: critiques are precise but narrow.

-

$`N_{\text{ego}} = 2`$: 41.3% disagreement, indicating complementary coverage.

-

$`N_{\text{ego}} = 3`$: 68% disagreement, often contradictory or unproductive.

Error Localization by Ego Critics

We measure whether at least one ego critic correctly identifies the first incorrect step in the base chain of thought:

-

$`N_{\text{ego}} = 1`$: 58% success.

-

$`N_{\text{ego}} = 2`$: 74% success.

-

$`N_{\text{ego}} = 3`$: 69% success.

Counterfactual Depth and Failure Modes

Manual inspection reveals three dominant categories:

-

Arithmetic recomputation.

-

Assumption revision (constraints/units).

-

Structural correction (equation setup).

Reward Variance and Optimization Stability

We track reward variance across GRPO updates:

-

$`N_{\text{ego}} = 1`$: low variance, weak signal.

-

$`N_{\text{ego}} = 2`$: moderate variance, strongest signal.

-

$`N_{\text{ego}} = 3`$: high variance, unstable updates.

Scaling Behavior Across Model Sizes

Relative improvements decrease with capacity: Qwen2-0.5B yields $`\sim`$30% relative lift, Llama-3.2-1B improves by 6–7%, while Llama-3.2-3B and Mathstral-7B show $`\sim`$0.3%.

Extended Experimental Results

This section reports full per-run results for all evaluated models and ego configurations. Each table aggregates multiple random seeds and reports both absolute and relative performance changes compared to the chain-of-thought baseline.

Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct

Table 5 reports detailed results for the 1B-parameter Llama model under different numbers of ego critics, learning rates, and training epochs. Results are shown for individual runs and averaged across seeds.

| Configuration | Base Acc. | Trained Acc. | Lift (pts) | Lift (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (CoT) | – | 33.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 1 ego, lr=$`1\text{e-6}`$, ep=5 (avg) | 33.03 | 35.28 | +2.25 | +6.79 |

| 2 egos, lr=$`1\text{e-6}`$, ep=5 (avg) | 33.06 | 35.58 | +2.53 | +7.69 |

| 3 egos, lr=$`1\text{e-6}`$, ep=5 (avg) | 32.55 | 33.43 | +0.88 | +2.65 |

Aggregated GSM8K results for Llama-3.2-1B-Instruct across ego configurations.

Across configurations, introducing one or two ego critics consistently improves performance. Two egos achieve the strongest average gains, while three egos introduce variance that reduces net improvement.

Learning rate sensitivity.

Using a higher learning rate ($`5\times10^{-6}`$) with two egos leads to unstable training and degraded performance, confirming that counterfactual critique benefits from conservative optimization.

Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct

Table 6 reports results for the 3B-parameter Llama model.

| Configuration | Base Acc. | Trained Acc. | Lift (pts) | Lift (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (CoT) | – | 59.72 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 1 ego, lr=$`1\text{e-6}`$, ep=5 (avg) | 59.72 | 59.89 | +0.18 | +0.30 |

GSM8K results for Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct.

Improvements for the 3B model are modest but stable, consistent with the hypothesis that larger models already perform partial internal verification and therefore benefit less from explicit counterfactual critique.

Qwen2-0.5B-Instruct

Table 7 reports results for Qwen2-0.5B with two ego critics.

| Run | Base Acc. | Trained Acc. | Lift (pts) | Lift (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.73 | 10.69 | +2.96 | +38.24 |

| 2 | 8.26 | 11.14 | +2.88 | +34.86 |

| 3 | 9.10 | 10.69 | +1.59 | +17.50 |

| Average | 8.36 | 10.84 | +2.48 | +30.20 |

Extended GSM8K results for Qwen2-0.5B-Instruct with two ego critics.

Qwen2-0.5B shows the largest relative improvements, highlighting the effectiveness of ego-driven counterfactual critique in low-capacity regimes where baseline reasoning errors are frequent and diverse.

Mathstral-7B

For Mathstral-7B, which is explicitly trained for mathematical reasoning, ego-driven training yields small but consistent gains ($`\sim`$0.3%). Performance never degrades, indicating that counterfactual critique remains safe even for domain-specialized models.

Additional Ablations

This section evaluates design choices related to optimization, reward shaping, and ego configuration.

Number of Ego Critics

Across all models, performance follows a consistent pattern:

-

One ego improves accuracy with low variance.

-

Two egos maximize useful disagreement and achieve the strongest gains.

-

Three egos introduce excessive variance, reducing net improvement.

Learning Rate and Epoch Sensitivity

For Llama-3.2-1B, learning rates above $`1\times10^{-6}`$ lead to unstable optimization. Training for fewer than three epochs underutilizes counterfactual supervision, while beyond five epochs yields diminishing returns.

Optimization and Reward Design

-

Optimization: GRPO consistently outperforms PPO and supervised fine-tuning by stabilizing learning across multiple counterfactual trajectories.

-

Reward coefficients: $`(\alpha=1.0,\beta=0.7,\gamma=0.2)`$ achieves the best balance between correctness, critique utility, and drift control.

-

Critique depth: shallow multi-step counterfactuals outperform deeper trees, which tend to introduce hallucinated reasoning paths.

Inference-Time Ablations

We evaluate inference using (i) base-only reasoning, (ii) base + one ego, and (iii) base + two egos. Using ego critics at inference improves robustness, but most gains persist even when ego prompting is removed after training, indicating that counterfactual critique is internalized into the base policy.

Training Cost Estimates

For $`N_{\text{ego}}=2`$, each training example requires approximately four forward passes: one base solution and two counterfactual critiques, plus one additional selection pass. This corresponds to a $`\sim4\times`$ computational cost relative to supervised fine-tuning. In practice, shared-key caching and batched generation reduce wall-clock overhead.

Additional Implementation Notes

-

All experiments use bf16 precision.

-

Counterfactual generations are capped at 256 tokens.

-

Generation temperature is fixed at 0.2 across all runs.

-

Gradient accumulation is used to maintain an effective batch size of 8.

-

Evaluation uses normalized exact-match accuracy for GSM8K.

Reproducibility Checklist

We release prompt templates, hyperparameters, evaluation scripts, raw per-run results, and random seeds. All experiments can be reproduced using the configuration files included in the supplementary material.

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)