Technologies for automatically generating work schedules have been extensively studied; however, in long-term care facilities, conditions vary between facilities, making it essential to interview the managers who create shift schedules to design facility-specific constraint conditions. The proposed method utilizes constraint templates to extract combinations of various components, such as shift patterns for consecutive days or staff combinations. The templates can extract a variety of constraints by changing the number of days and the number of staff members to focus on and changing the extraction focus to patterns or frequency. In addition, unlike existing constraint extraction techniques, this study incorporates mechanisms to exclude exceptional constraints. The extracted constraints can be employed by a constraint programming solver to create care worker schedules. Experiments demonstrated that our proposed method successfully created schedules that satisfied all hard constraints and reduced the number of violations for soft constraints by circumventing the extraction of exceptional constraints.

The nursing care industry has recently been facing a severe labor shortage, and reducing staff turnover has become a critical issue alongside efforts to recruit new personnel. Creating work shifts that satisfy staffing demands is an essential measure for attracting personnel and retaining employees [1,7]. Care worker scheduling resembles nurse scheduling problems (NSP) [4]; each must consider primary constraints, such as the number of staff needed, each staff member's workdays, work hours, and leave requests, and additional factors such as interpersonal relationships among the staff. Creating a care worker schedule typically requires an entire workday.

Technologies for automatically generating work schedules have been extensively studied [4]; however, in longterm care facilities, conditions differ significantly across facilities, and it is necessary to define constraints for each. Consequently, many interviews are required to obtain sufficient constraints to create a schedule automatically. Such interviews are a heavy burden for the facilities, which has hindered the introduction of the work schedule generation system, and very few facilities have introduced such a system [3]. Furthermore, compared to nurse scheduling, care worker scheduling is subject to various constraints, such as the number of available shifts varying significantly from person to person, the qualification status of staff varying, and many part-time staff working short hours. This study proposes a method for extracting constraints from past schedules and generating care worker schedules using the extracted constraints. The proposed method employs constraint templates to extract combinations of various components, such as shift patterns for consecutive days or staff combinations. In addition, unlike existing constraint extraction techniques, this study incorporates mechanisms to exclude exceptional constraints. That is, in past schedules, if there were days or a staff member with many leave requests, shifts assigned to them to compensate for staff shortages-despite being undesirable-are excluded from constraint analysis.

2 Related work

Care worker scheduling problems are typically categorized into home-and facility-based types [1]. The homebased type involves problems of determining dates and times for service and the period of service provided to a person in need of home care services. The facility-based type involves problems of determining shift assignments that respect staff leave requests and other preferences while promoting fairness in the working environment. Compared with NSPs, facility-type care worker scheduling problems are often over-constrained, making it difficult to obtain feasible solutions due to budget limitations and staffing shortages. Therefore, this study focuses on care worker scheduling problems in facilities. Kurokawa et al. solved the problems of maximizing overall sales by accumulating services by packing as many as possible into the hours when helpers are on duty while maintaining fairness in the working environment. They used genetic algorithms, differential evolution, tabu search, and quasi-annealing methods and compared the results [7]. Sakaguchi et al. proposed a schedule planning and caregiver assignment method that equalizes the workload of each care worker [9].

Research on the automatic design of constraints from past solutions has recently emerged. Constraints are essential when formulating real-world problems. Fajemisin et al. formalized the process of learning constraints from data, and reviewed recent literature on constraint learning [5].

Studies have also begun to be conducted on NSPs [6]. Paramonov et al. proposed a method for extracting constraints from two-dimensional tabular data using constraint templates [8]. Their method aggregates data within specific blocks and extracts element counts and combinations according to specified criteria. Kumar et al. proposed a method for extracting constraints from multidimensional design variables using tensor expressions [6]. This method uses aggregate functions to extract constraints that include numerical terms. Ben et al. focused on NSP’s dynamic characteristics, including unpredictable and unforeseen events such as accidents and nurses’ sick leave. They proposed a method for automatically and implicitly learning NSP’s constraints and preferences from available historical data without prior knowledge [2].

Although these previous studies have examined methods for extracting diverse constraints, the problem of identifying undesirable patterns within the extracted constraints remains underexplored.

3 The proposed method

This paper proposes a method to extract constraints from past schedules of a long-term care facility for elderly individuals using constraint templates and to generate a monthly daily care worker schedule based on the extracted constraints. Following are the key ideas of the proposed method.

Idea 1: Extracting constraints from past work schedules. The proposed method extracts constraints from past work schedules using constraint templates. The templates can extract a variety of constraints by changing the number of days and the number of staff to T 3 H 3 Keep the working hours within the specified limit.

T 3 H 4 Assign the required number of staff for each shift.

T 4 H 5 Assign N i and No to two consecutive days.

T 2 Soft S 1 Assign a day off the day after the No.

T 1 S 2 Assign a shift sequence of No, D, and holiday if a holiday cannot be assigned to the day after No.

T 1 S 3 Prohibit a sequence of No, a day off, and N i .

T 1 S 4 Equalize the number of night shift assignments.

T 3 S 5 Prohibit more than four consecutive day shifts.

T 1 S 6 Assign the requested days off or shifts to staff according to their requests.

focus on and changing the extraction target to patterns or frequency. Idea 2: Incorporating staffing margin to exclude exceptional constraints. If exceptional work patterns caused by understaffing, as described above, are extracted, patterns that must be avoided, such as long consecutive shifts, will be allowed when creating a new work schedule. We exclude such patterns by introducing staffing margin and flexibility, which express the ratio of available workers relative to the number of necessary workers and the ratio of the number of requested leave days relative to the number of the leave days, respectively. Idea 3: Employing constraint programming solver with gradual constraint relaxation. Any solver can use the extracted constraints, such as linear programming, constraint programming, and meta-heuristics. This study adopts a constraint programming solver to validate the extracted constraints’ effectiveness. The solver disallows assignments outside the extracted patterns, yet some valid assignments may not have appeared in past schedules. Therefore, when no feasible solution is found, the proposed method gradually relaxes some of the hard constraints into soft constraints to obtain a feasible solution.

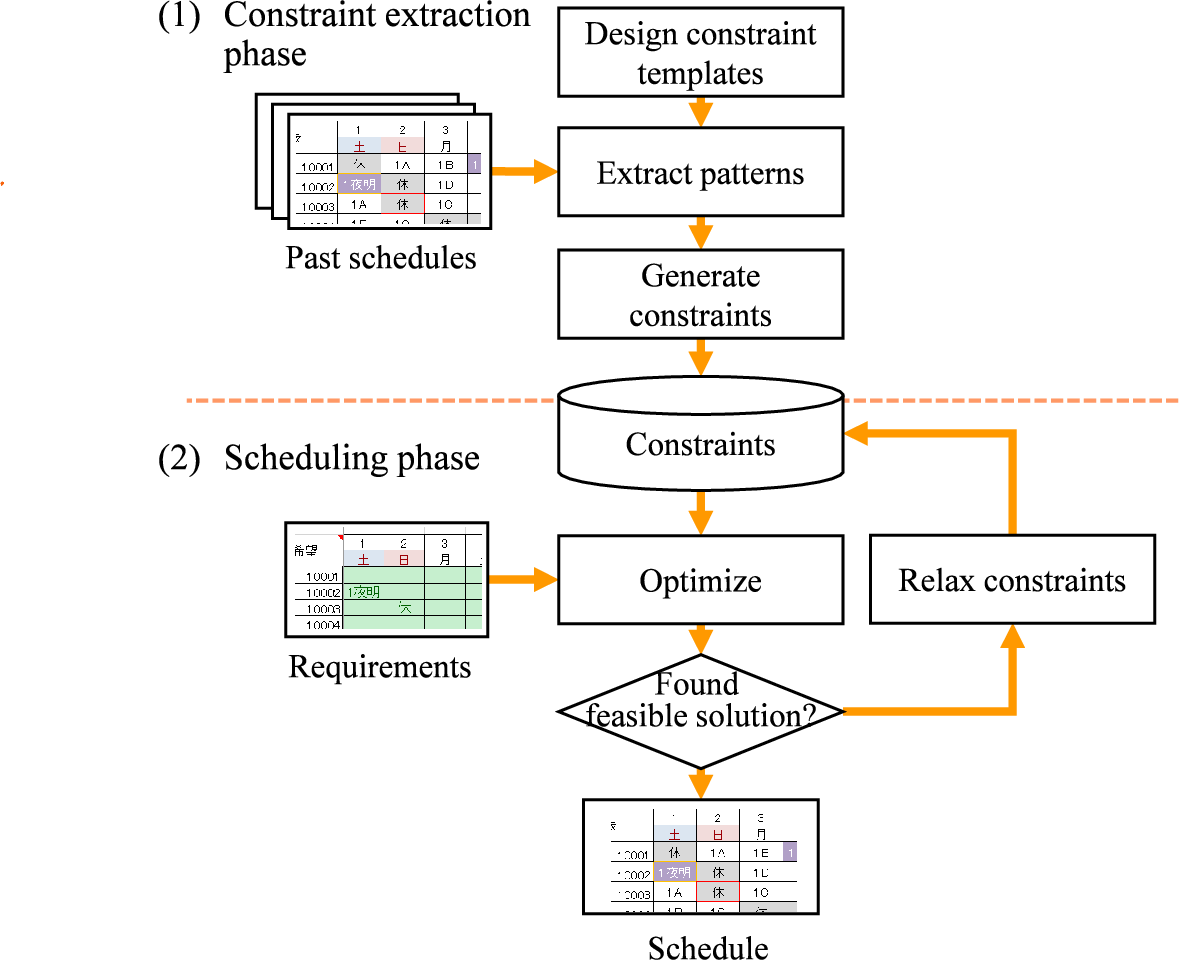

Fig. 1 shows the overall structure of the proposed method, which includes a constraint extraction phase and a scheduling phase. In the constraint extraction phase, constraints are extracted from past work schedules using constraint templates, which are work patterns or the number of occurrences of patterns in a range of interest from past work schedules.

The scheduling phase generates a new schedule using the extracted constraints. In the scheduling phase, various methods, such as constraint satisfaction solvers and meta-heuristics, can be used in the proposed method.

In the scheduling phase, the solver decides a set X of binary variables that indicate, for each day d, staff member w, and shift s, whether w takes s on d (1) or not (0).

where D denote the set of days to be scheduled; our proposed method builds monthly rosters, so |D| ∈ {28, . . . , 31}.

W and S denote the staff set and the set of shift types, respectively.

The staff rostering problem can be formulated as follows:

where V i (x) = 1 if x violates constraint i and 0 otherwise; C Soft and C Hard collect soft and hard constraints, respectively. Thus, the solution satisfies all hard constraints while reducing violations of soft constraints.

For instance, a constraint to ensure that staff w takes exactly one shift on day d, can be described as follows:

Likewise, a constraint to satisfy demand for shift s on day d is subject to

that is, at least r d,s staff for shift s.

The specified shift combinations are retrieved from past schedules using constraint templates in the constraint extraction stage. These templates specify the shift and staff combinations to be extracted, and those that appear are considered assignable combinations. Table 1 shows the constraint templates applied in this method.

The constraint template comprises the period, number of persons, generality, type, and reference information.

The number of days determines the length of time for extracting the pattern and the number of times. The number of persons determines how many patterns are extracted. Generality specifies whether the focus is on particular elements (e.g., members) or on all elements, while type determines whether the pattern is extracted or how many times it is measured. Reference determines which data are referred to when extracting elements other than past schedules, such as days of the week and requested holidays. Constraint templates T 1 and T 2 extract shift patterns a staff member has worked consecutively. The extracted constraints are formalized and passed to the solver in the scheduling phase. We specifically extract the assignable shifts obtained using T 1 for each staff member individually, and extract the assignable shifts for all staff members using T 2 . Constraint template T 3 extracts the number of days per month that each staff member is available to work. Constraint template T 4 extracts the number of shifts required for each day of the week. The above template is necessary because the number of required workers changes for each day of the week.

Table shows the relationship between the constraint templates and general constraints obtained by interviews to a facility manager. Constraints are generally categorized as hard constraints that must be satisfied and soft constraints that should be satisfied as far as possible. Hard constraints H 1 and H 3 limit monthly working days and working hours, and T 3 derives these limits from past schedules. Likewise, H 2 guarantees that each staff member receives only shifts they can cover, and T 3 extracts this constraint as well. H 5 addresses night work that spans two dates; N i and N o denote the shifts on the start and end days, respectively. Constraints of this type follow from template T 2 . In the facility we interviewed, staff take the day after a night shift off; however, when applying our method to other facilities that assign consecutive nights, T 2 still captures the corresponding constraints.

Exclude staff whose flexibility is less than τ f 18:

end for

Σt ← ReduceMonth(Dm, Σt)

end for

C ← C ∪ ReduceFinal(t, Φ, Σt, nm, τc) 30: end for 31: return C Preferences about night work are modeled as soft constraints, and template T 1 extracts them automatically. For example, the interviewed facility requires a day off after a night shift (S 1 ). When this proves difficult, it assigns a day shift on the following day and then grants a day off after that day shift (S 2 ). It also permits a night-off-night pattern (S 3 ). T 1 derives these rules from historical rosters. In addition, T 1 extracts a constraint that limits consecutive day shifts to at most three days (S 5 ), while T 3 balances night-shift assignments across staff (S 4 ) by using shift-count statistics.

As described above, most constraints fit one of four templates; accordingly, we include S 6 by a default constraint because S 6 is common across facilities.

end for 25:

for each u with (κ, u) ∈ supp(Dm) do

Uκ ← Uκ + µ Dm (κ, u) • u

end for 7:

8: end for 9: return Σ ′ t

The proposed method incorporates a staffing margin to exclude the workdays with staff shortages from constraint extraction. The staffing margin u d for a given workday d is the value obtained by dividing the number of staff available for work a d by the required number of staff r d , i.e., u d = a d r d . Note that u d can be calculated from the results of staff members’ vacation requests. If u d is less than the threshold value τ u , the constraint is not extracted for day d. When applying a constraint template that spans multiple days, the minimum staffing margin among those days is used.

The proposed method also considers a staff member that requests many leave days as an exception, because too many requests makes it more difficult to create a Algorithm 4 ReduceFinal(t, Φ, Σ t , n m , τ c )

for each κ with (κ, v) ∈ supp(Σt) do 4:

if vκ ≥ τc then 7:

end for 10:

for each κ with (κ, v) ∈ supp(Σt) do 13: In addition to excluding exceptions using the aforementioned u d and u f , the proposed method also omits shift patterns with low frequency. That is, if the number of occurrences of an extracted pattern is less than the threshold value τ c , it is not extracted as a constraint.

Algorithms 1, 2, 3, and 4 show the algorithm for extracting constraints using constraint templates T 1 through T 4 while considering staffing margin. The main loop, shown in Algorithm 1, runs per constraint template and per month. Each constraint template includes duration δ, target staff σ, generality Φ, and type γ. Using the template-defined sliding window W , our method scans historical rosters. It invokes procedure Collect shown in Algorithm 2 to list patterns and their counts, then invoke procedure ReduceMonth shown in Algorithm 4 for monthly aggregation. Procedure Collect scans the past scheduling table using window W , and generates a multiset ∆ of (κ, u) pairs. Its subprocedure Com-poseKey generates the aggregation key κ while encoding the generality (e.g., distinguish T 1 and T 2 ). After all months are processed, it run procedure ReduceFinal shown in Algorithm 4 to aggregate patterns and produce constraint instances. Procedure ReduceFinal aggregates the monthly summaries {Σ m } by key across months, calls Normalize to compute the template-specified metric, and converts the result into the final constraint instances to return. Subprocedure Normalize converts the daily staff count h to a cross-month scale; it returns h for COUNT type template with UNIT option, and h divided by its number of occurrence days for a template with WEEKDAY option.

The scheduling phase generates shift plans based on extracted constraints. Constraints specifying exact numbers of working days or staff members, such as H 1 and H 4 , are implemented in as soft constraints for the exact target and as hard constraints that allow minor deviations, enabling practical and flexible assignments.

When no feasible solution is found, the proposed method gradually relaxes hard constraints into soft ones and repeatedly apply the solver. Constraints extracted from Template T 2 are initially treated as hard constraints. However, since they prohibit all shift patterns that did not appear in past schedules, they can be overly restrictive. Moreover, they may conflict with other hard constraints and prevent scheduling generation. Thus, when infeasibility occurs, the proposed method begins by relaxing longer constraints from T 2 and reattempt solving. The similar staff members were identified using attributes that follow from contract type, such as feasible shift types and the number of working days.

In addition to the constraints extracted from the past schedules, the following constraints were manually added: constraints that were easily clarified during interviews and constraints related to newly hired staff, which were difficult to extract from past work schedules.

-Constraints for new staff members not included in past schedules used for extraction were defined by mirroring those of similarly positioned staff. -Constraints S 6 , which fulfills leave requests and shift preferences, was initially added as hard constraints.

If the solution remains infeasible, the proposed method proceeds to incrementally remove shift requests by staff members to further relax the constraints.

Experiments using 48 months of scheduling data at a special nursing home for elderly individuals in Kagoshima city were conducted to verify the proposed method’s effectiveness. This facility divides its living space into two units, U1 and U2; For four years, we created work schedules for the facility, and the facility manager revised them, thereby accumulating data. In this experiment, the proposed method abstracted all of the day shifts in U1 and U2 into one type of shift, D, and the night shifts in U1 and U2 were abstracted into 1N and 2N, respectively. Thus, day shift collapses to one shift type D across U1 and U2, whereas night shift preserves the unit label and unifies the night-start and night end days, N i and N o , into 1N (U1) and 2N (U2), as shown in Table 3. A, B, and C shifts denote day shifts with different start times (A: early; B: standard, C: late); A shift also holds the day-shift leadership. D denotes the day-care assignment for non-residential service users, and E denotes a morning-only assignment.

The task of constructing detailed shifts including original 16 shift types from the abstracted ones is considerably easier than generating the abstract shifts themselves. The practical shift can be obtained by subdividing the day shift D into 10 variations. This is because the constraints on these detailed shifts are relatively weak compared to those for night shifts or leave, and can be satisfied by adjustments within the subdivision framework, thus allowing the process to be performed in a nearly greedy manner. The quality of the final, detailed shift depends directly on the quality of the initial abstract shifts; higher-quality abstract shifts yield a high-quality final schedule.

We took this approach because the data for constraint extraction was insufficient for many constraints. The relationship between the constraint templates and constraints obtained by the hearing under the condition that abstracted day shifts, as mentioned above, was summarized in Table 3.4. Templates T 1 and T 2 were applied to past schedules to extract patterns ranging from two to seven days in duration, i.e., n min d = 2 and n max d = 7. Parameters τ c , τ u , and τ f were set to 0.15, 1.25, and 0.5, respectively 1 .

Table 4 shows the number of constraints extracted from past schedules for 36 months. Incorporating staffing margin and flexibility reduces constraints obtained using T 1 . Fig. 2 shows example constraints created using T 1 for staff 10005. The values within each extracted constraint instance includes staff ID and an available shift sequence. For instance, the first instance indicates staff 10005 can take a day shift after a day off, and the fourth instance describes they can take a day off after a night shift and then work a day shift the following day. It demonstrated that the proposed method could generate essential constraints, such as scheduling night shifts for two consecutive days and providing a day off subsequent to night shifts. Fig. 3 shows example constraints excluded as exceptions using staffing margin and flexibility. The examples showed that schedules assigning day shifts immediately following night shifts and schedules assigning a single day shift with days off before and after were excluded as exceptions.

Fig. 4 shows the extraction results using the constraint template T 3 , which provides a list of available shifts for each staff member. The numerical values within each extracted constraint instance denote the staff ID, shift type, the start and end work dates for the month, and the lower and upper limits for the shift. Furthermore, T 3 told us that staff member 10006 is a part-time staff member because of the small number of days they work and which staff members need to reduce the number of night shifts. Fig. 5 shows constraint examples extracted using the constraint template T 4 . Each extracted constraint 1 These thresholds were heuristically determined. τ c and τ u were calculated based on the value near the 33rd percentile of monthly occurrence rates across shift patterns (after sorting in ascending order), and (dailyminimum+2)/(dailyminimum) for day shifts (e.g., 10/8), respectively. We set τ f = 0.5 because months with leave requests on more than half of the days showed many exceptional assignments. instance specifies the day of week, the shift, and the number of staff needed. These results indicate that the number of day shift workers required varies depending on the day of the week. This is because day-care services are provided only on certain days of the week at the facility, and the number of day shift workers is reduced on weekends when day-care services are not provided. In addition, two night shift workers are required for each unit regardless of the day of the week. This is because the staff in charge of the night shift from the day before to the day of the experiment and the staff in charge of the night shift from the day of the experiment to the next day are needed separately.

Next, using the extracted constraints, the proposed method generated care work schedules for 12 months. The strength of the extracted constraints was manually established as follows. All constraints extracted by T 1 were regarded as soft constraints. For the constraints extracted by T 3 , the exact extracted count was treated as a soft constraint, while the count within a ±1 range was treated as a hard constraint. For example, if the extracted number of times was 8, two constraints were created: a soft constraint to satisfy the specified number of times and a hard constraint to keep the number of times within the range of seven to nine. The conditions extracted in T 4 were also expressed as a combination of hard and soft constraints like those extracted by T 3 . For example, if four staff members are required to shift D on a particular day, there is no constraint violation if four staff members are assigned. A soft constraint is violated if five staff members are assigned, and a hard constraint is violated if more than six or fewer than three staff members are assigned.

Constraints extracted using T 2 followed a different treatment. The constraints were generally considered as hard constraints; however, if a feasible schedule could not be created, the constraints were iteratively relaxed, i.e., regarded as soft constraints, beginning with the longest ones, until the scheduling succeeded.

This experiment used a CP-SAT solver Ver. 9.6.2534 in Google OR-Tools to directly verify the extracted constraints’ effect. The soft constraints were incorporated by using the number of violations as the objective function. We set the solver’s time limit to one hour. Constraints extracted using T 2 were treated as hard constraints, as specified in Sec. 3.6, but progressively relaxed starting from seven-day constraints when a feasible solution was unavailable. Solutions were identified directly under strict constraints in five of the twelve months, while in three months, relaxation to a weaker form with seven-day constraints was necessary. Moreover, additional relaxations to constraints of six, five, and four days were each required for one month, two months, and one month, respectively, whereas no greater relaxation was required during the twelve-month experimental evaluation.

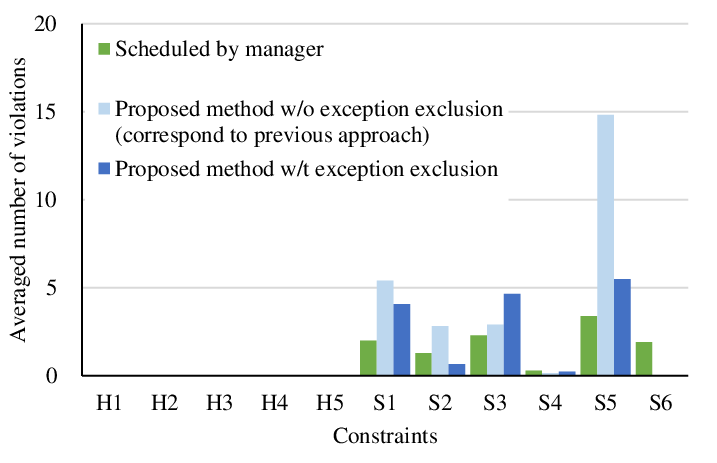

This experiment compared our proposed method, which removes exceptional constraints, against a variant that does not. This latter version (the proposed method without exception exclusion) was implemented to serve as a baseline corresponding to the conventional approach such as [2,6,8]. Figs. 6 and7 show an example schedule and the number of violations for hard and soft constraints obtained through interviews, respectively. Both cases of the proposed method with and without exception exclusion using staffing margin and flexibility showed no violations of any hard constraints, indicating that the proposed method successfully learned essential constraints. In addition, exception exclusion reduced the number of violations of soft constraints S 5 , demonstrating its effectiveness.

In particular, focusing on the number of violations for S 6 in Fig. 7, manager-designed schedules often failed to accommodate all staff requests, especially during months with many requests, averaging two unsatisfied vacation requests per month. In contrast, the proposed method, which initially enforced shift requests as hard constraints, generated conflict-free schedules that satisfied all requests.

This study proposes a method for extracting facilityspecific constraints from past work schedules to schedule care workers at long-term care facilities. This method can extract various constraints by preparing constraint templates while avoiding extracting exceptional constraints considering the staffing margin and flexibility, thus reducing the effort required for interviews when implementing a scheduling system, which often impedes the adoption of scheduling systems. Experiments in a facility with approximately 20 staff members confirmed that it is possible to extract a set of shifts for each staff member that can be allocated for a few consecutive days in addition to primary constraints, such as the types of shifts each staff member can work and the number of days each shift can be worked. Importantly, the proposed method successfully reduced the number of violations of soft constraints by excluding exceptional constraints. In the future, we plan to improve our method so that it can extract constraints without abstracting the day shifts.

The data included survey results of desired leave days from all staff Algorithm 5 C Hard ← C

Notation. For a multiset M , µ M (π) denotes the multiplicity (count) of pattern π in M ; ⊎ is multiset addition; supp(M ) = {x ∈ U |µ M (x) > 0} .

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.