Foundation models on the bridge: Semantic hazard detection and safety maneuvers for maritime autonomy with vision-language models

📝 Original Info

- Title: Foundation models on the bridge: Semantic hazard detection and safety maneuvers for maritime autonomy with vision-language models

- ArXiv ID: 2512.24470

- Date: 2025-12-30

- Authors: Kim Alexander Christensen, Andreas Gudahl Tufte, Alexey Gusev, Rohan Sinha, Milan Ganai, Ole Andreas Alsos, Marco Pavone, Martin Steinert

📝 Abstract

The draft IMO MASS Code requires autonomous and remotely supervised maritime vessels to detect departures from their operational design domain, enter a predefined fallback that notifies the operator, permit immediate human override, and avoid changing the voyage plan without approval. Meeting these obligations in the alert-to-takeover gap calls for a short-horizon, humanoverridable fallback maneuver. Classical maritime autonomy stacks struggle when the correct action depends on meaning (e.g., diver-down flag means people in the water, fire close by means hazard). We argue (i) that vision-language models (VLMs) provide semantic awareness for such out-of-distribution situations, and (ii) that a fast-slow anomaly pipeline with a short-horizon, human-overridable fallback maneuver makes this practical in the handover window. We introduce Semantic Lookout, a cameraonly, candidate-constrained vision-language model (VLM) fallback maneuver selector that selects one cautious action (or stationkeeping) from water-valid, world-anchored trajectories under continuous human authority. On 40 harbor scenes we measure per-call scene understanding and latency, alignment with human consensus (model majority-of-three voting), short-horizon risk-relief on fire hazard scenes, and an on-water alert→fallback maneuver→operator handover. Sub-10 s models retain most of the awareness of slower state-of-the-art models. The fallback maneuver selector outperforms geometry-only baselines and increases standoff distance on fire scenes. A field run verifies end-to-end operation. These results support VLMs as semantic fallback maneuver selectors compatible with the draft IMO MASS Code, within practical latency budgets, and motivate future work on domain-adapted, hybrid autonomy that pairs foundation-model semantics with multi-sensor bird's-eye-view perception and short-horizon replanning. Website: https://kimachristensen.github.io/bridge_policy📄 Full Content

The regulatory IMO MASS Code currently being drafted speaks directly to this. Systems should “be able to detect whether [their] current state of operation meets the ODD”, and if the ship deviates from its operational envelope it should “enter a predefined fallback state” and “notify [its] crew and the operator”. Navigation automation must be “capable of being overridden at all times” and “allow for control to be taken immediately”. The “use of the voyage plan, and any modification of the voyage plan” by the navigation system is “not . . . possible without . . . approval . . . by the [operator]” (IMO, Maritime Safety Committee, 2024). We take this as a design requirement for an alert → fallback maneuver → human override loop in which the fallback maneuver consists only of short-horizon actions chosen from pre-approved primitives (or Station-keeping), is immediately overridable, and never edits the overall voyage plan. In this paper, the IMO fallback state is the vessel’s predefined degraded mode after an alert, and the fallback maneuver is the single short-horizon, pre-approved motion action executed within that fallback state during the alert-to-override interval until the operator overrides (takes manual control) or the alert clears.

Classic maritime stacks typically cover obstacle detection (e.g., radar/LiDAR), tracking (e.g., AIS, multi-target trackers), and short-horizon collision avoidance (Johansen et al., 2016;Hem et al., 2024). They don’t, however, interpret semantic cues such as “diver-down” flags, “keep-out” lines, or a vessel on fire; cases where the correct action depends on meaning, not geometry alone. To complicate things further, many hazards appear as out-of-distribution (OOD) scenes for vessel/object detectors: rare, open-ended “unknown unknowns” beyond prior experience (Sinha et al., 2022). Foundation models like large language models (LLMs) and vision-language models (VLMs) trained on internet-scale data provide strong semantic priors that support zero-/few-shot generalization and improved OOD behavior (Brown et al., 2020;Radford et al., 2021;Wortsman et al., 2022). Following Sinha et al. (2024), we define anomalies as semantic deviations from prior operational experience and leverage a two-stage pattern in which a fast embedding-space monitor can trigger slower generative reasoning. Their work shows this can enable real-time OOD anomaly detection and reactive planning; what remains is to adapt it to the specific needs of maritime autonomy and the IMO MASS code requirement for immediate, human-overridable control. We argue that being able to detect and react to such anomalies is an essential step in moving beyond constant, laborious human supervision and enabling one-to-many supervised maritime autonomy.

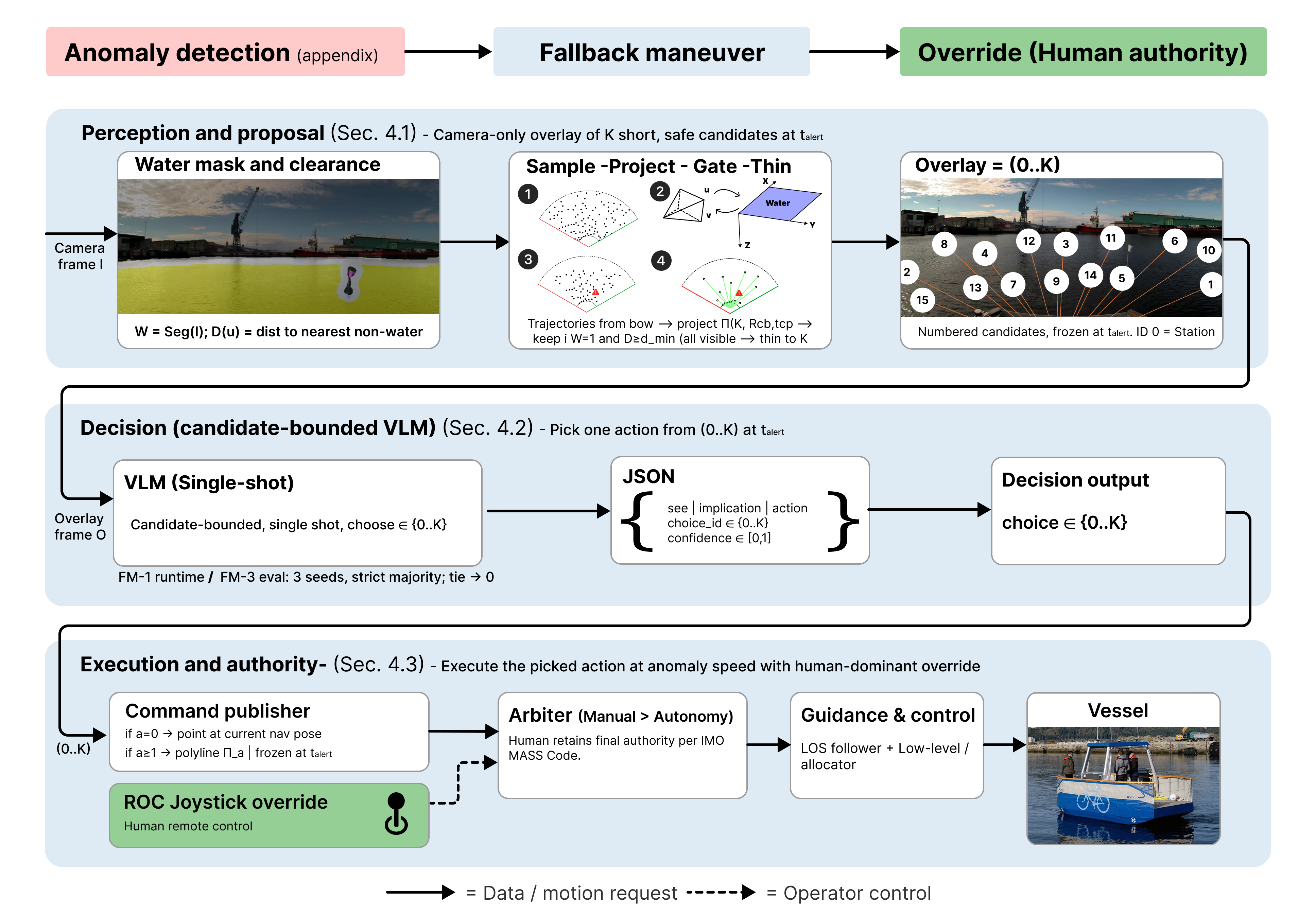

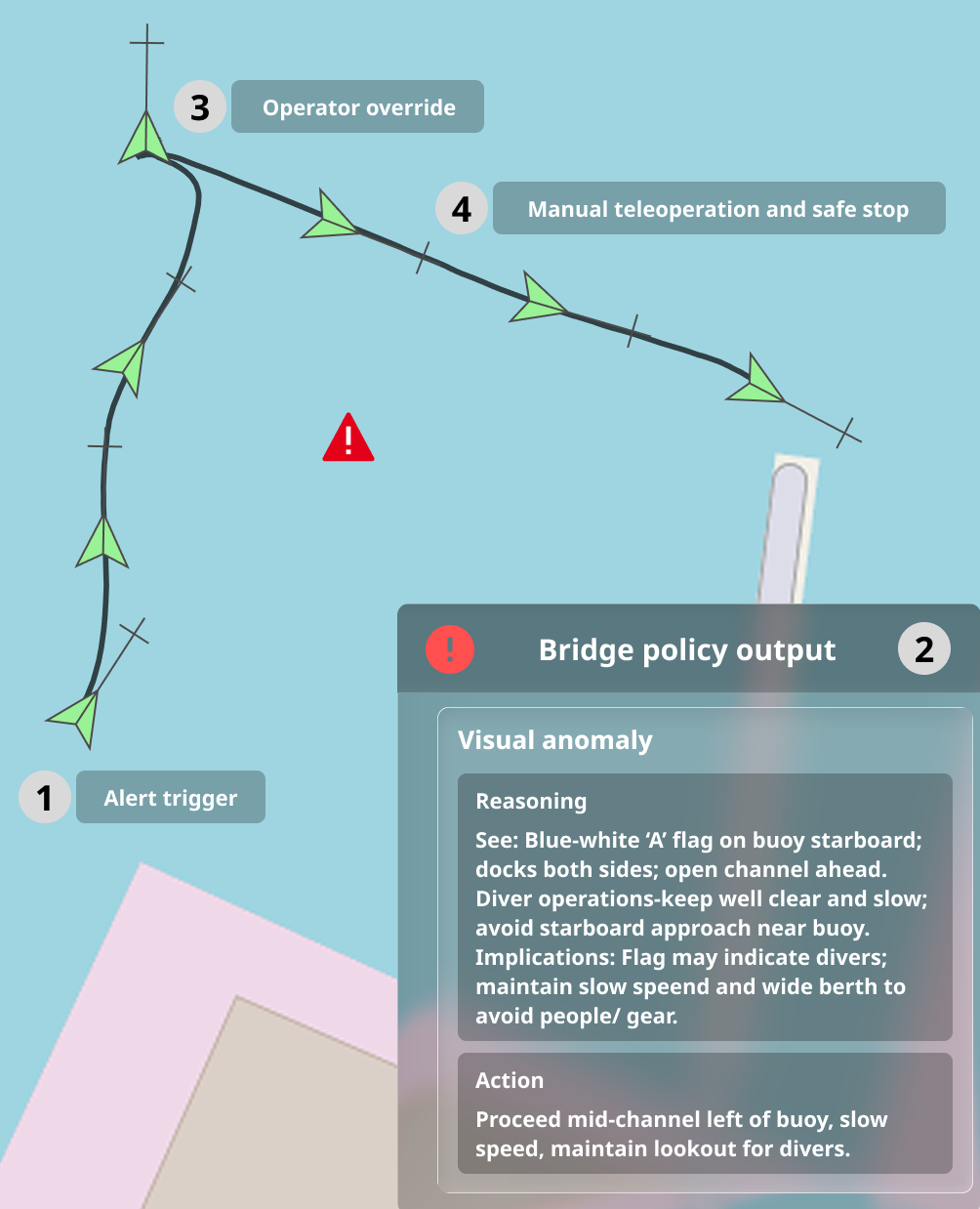

We operationalize the IMO MASS constraints as an alert → fallback maneuver → human override loop. Stage (1) is a small, camera-first fast anomaly alert adapted from Sinha et al. (2024). In Appendix A, we provide details and small n evidence that this monitor also functions in the maritime domain. Stage (2) is a short-horizon fallback maneuver that keeps the vessel safe and interpretable until the operator takes charge. Stage (3) is a hard-priority joystick override at the ROC. This paper focuses mainly on Stage (2) while validating the full chain.

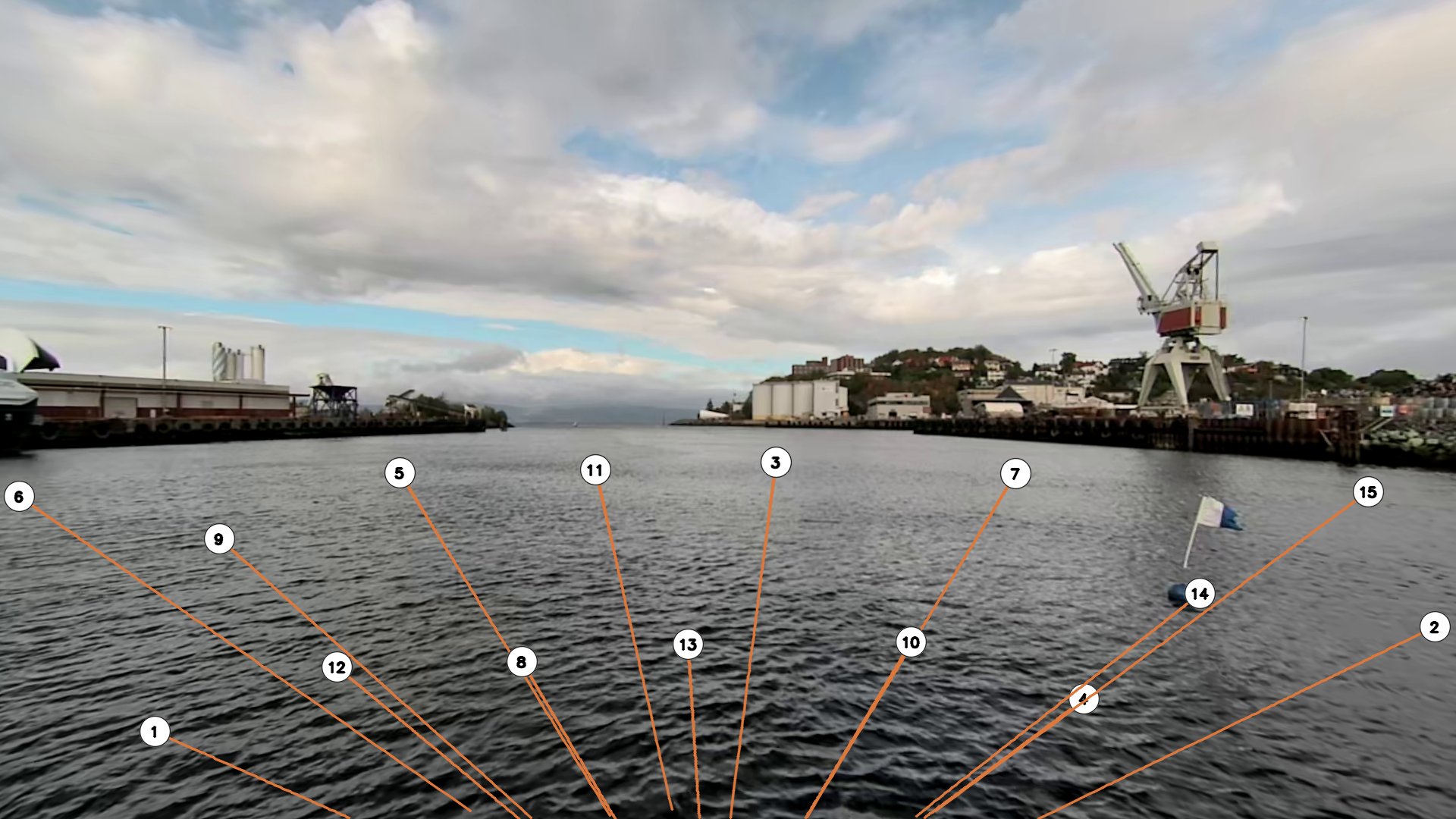

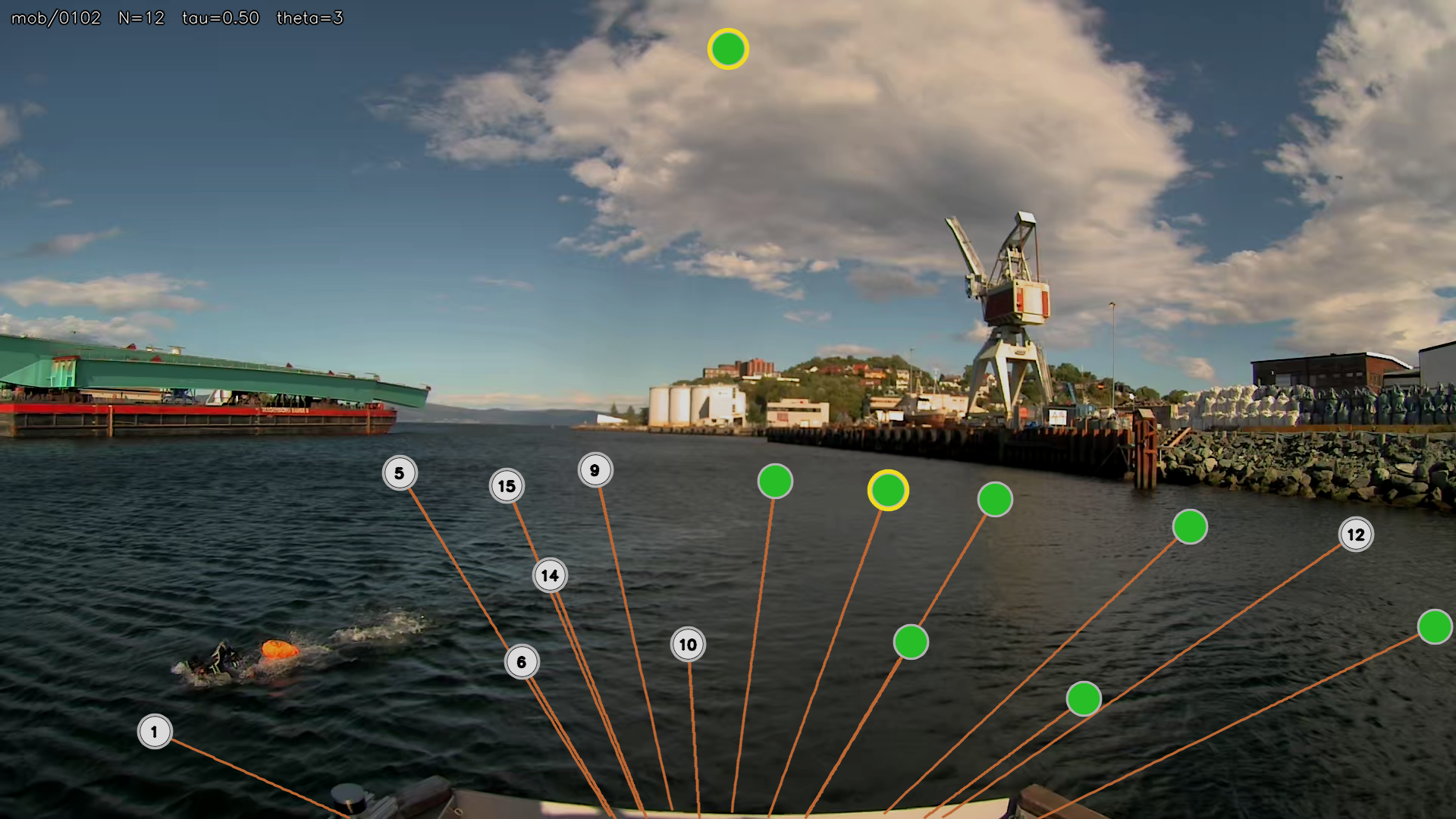

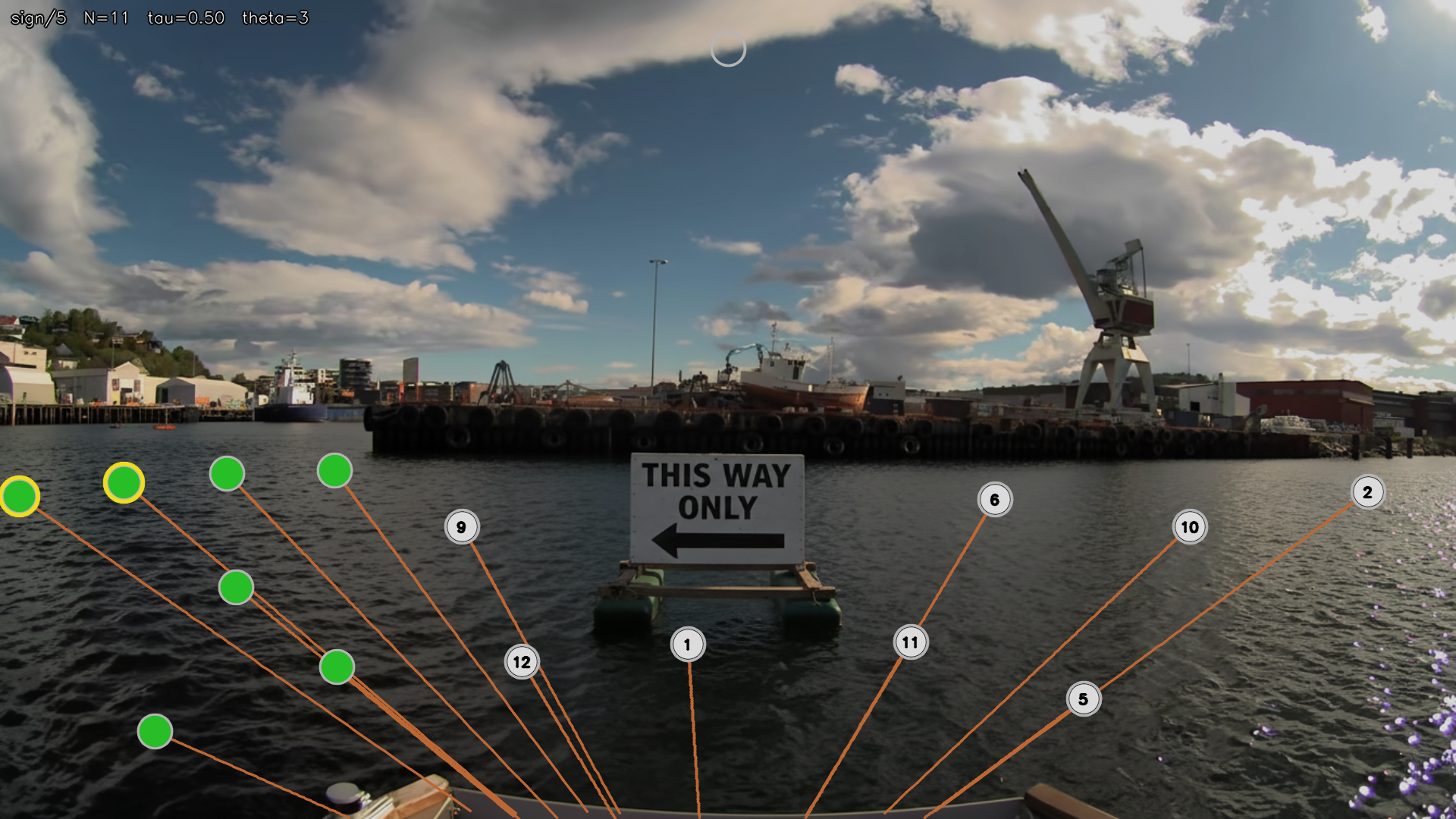

Specifically, we introduce Semantic Lookout, a proof-of-concept, camera-only fallback maneuver selector that constrains a vision-language model (VLM) to make one cautious, short-term choice among pre-vetted, water-safe trajectory candidates overlaid on the camera view (or to stop when uncertain). The system is designed to handle previously unseen semantic hazards and is aligned with the draft IMO MASS Code.

The objective of this study is to evaluate whether a candidateconstrained VLM can serve as an IMO MASS Code-aligned fallback maneuver selector in the alert-to-override interval. More broadly, we aim to evaluate foundation models as a promising technology to build reliability in OOD edge-cases that would otherwise require human judgment. We evaluate four questions on the same overlay stack used in live field tests: (i) scene understanding and latency in semantic maritime anomalies; (ii) alignment of selected fallback maneuvers with aggregated human Accept/Best judgments relative to geometryonly baselines; (iii) short-horizon “risk-relief” on unambiguously dangerous fire hazards (standoff distance); and (iv) endto-end operation of the alert→fallback maneuver→human override chain in a live harbor run with immediate joystick override and ROC-legible presentation, complemented by a formative handover human-machine interface (HMI) study. Detailed hypotheses, experiment setups and results are shown in Sec. 5. In summary, our contributions are as follows:

- IMO MASS-aligned fallback maneuver architecture.

We formalize the alert→fallback maneuver→override loop as the main design constraint: short-horizon, pre-approved actions (or Station-keeping), immediate override, and no overall voyage-plan edits. This leads to the following main modules (Fig. 1).

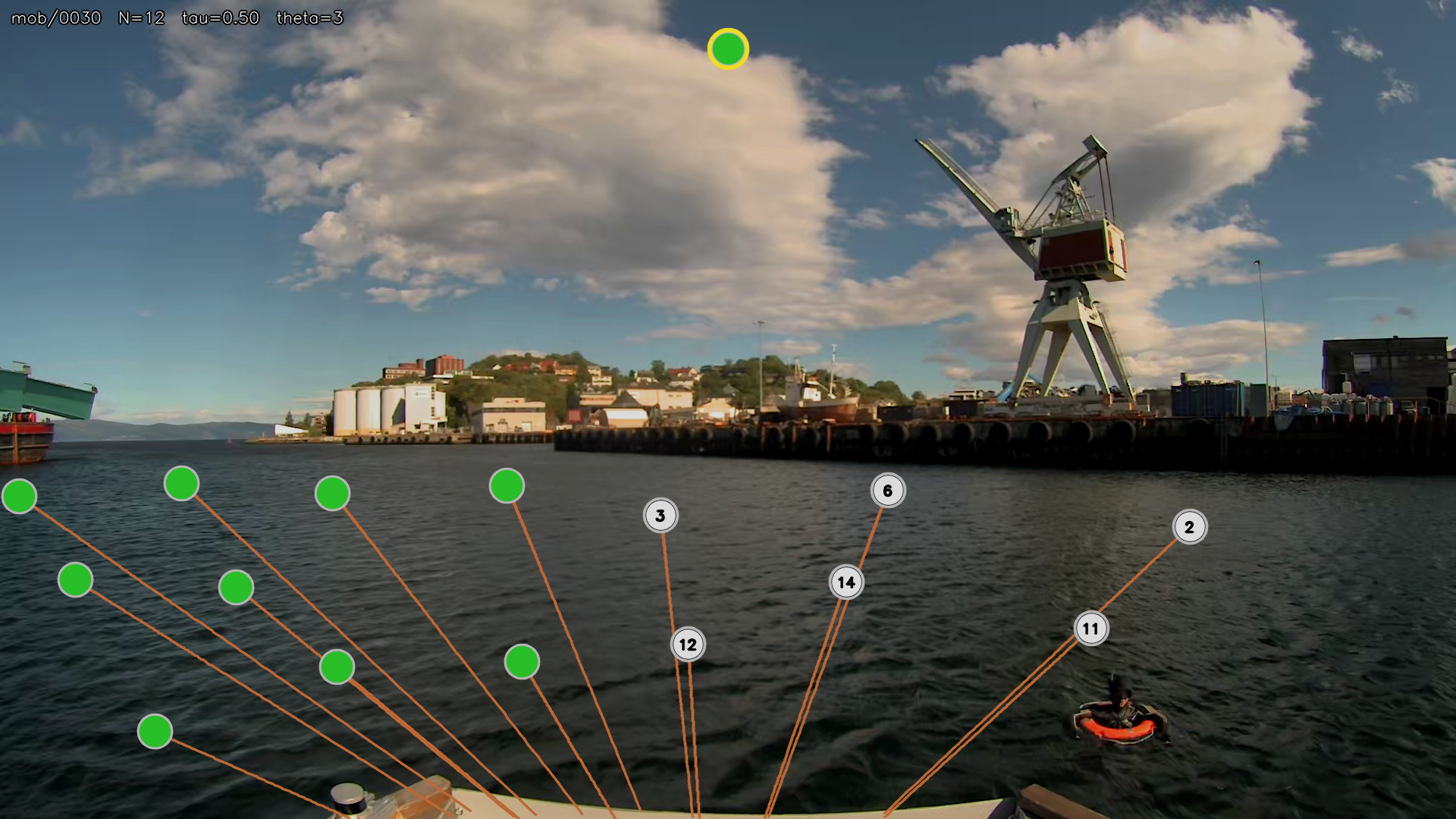

From a single image frame, we compute a water mask and pixel-clearance, sample/project short motion primitives, gate them in pixel-space, then reduce to a world-anchored, numbered candidate set used consistently online and offline.

-

VLM fallback maneuver selector with low-level execution and human override. A strict-schema VLM decision over the above candidates and an execution/authority path that publishes world-fixed waypoints to a lineof-sight waypoint follower with a direct joystick override blend ensuring immediate human authority.

-

Evidence of feasibility. Small-n fast anomaly monitor experiment (Appendix A); offline evaluation on overlays with human labeled ground truth; short-horizon fire “risk-relief” vs. geometry-only baselines; and a live alert→fallback maneuver→operator handover experiment with immediate joystick override. In all cases, the navigation system must be capable of override at all times so human control can be taken immediately. Any use of, or changes to, the voyage plan require Master (person in charge) approval (IMO, Maritime Safety Committee, 2024) These provisions support our focus on the alert→override interval.

ROC supervision and HMI. The NTNU Shore Control Lab provides a flexible, instrumented ROC for studying remote supervision and handover under realistic constraints (Alsos et al., 2022). Building on this infrastructure, a human-centered “situation awareness by design” ROC prototype emphasizes a camera-first view, explicit mode/authority cues, and predictable human control (Gusev et al., 2025). Evidence for one-to-many supervision remains limited: a controlled study reports degraded performance when operators supervise three vessels vs. one, and shows that shorter available response times (e.g., 20 s vs. 60 s) materially affect takeover outcomes, with lacking decision support systems compounding the effect (Veitch et al., 2024).

Control takeover is not instantaneous: first experimental results on highly automated inland vessels suggest that takeover times of more than 20 s can be expected even in simplified scenarios (Shyshova et al., 2024). Survey-based results for conventional merchant ships further suggest that response and situation-awareness recovery can be on the order of minutes (including physical movement to the control position), with reported time-budgets for hazardous situations also on the order of several minutes and with high variability (Wróbel et al., 2025). Together, these results motivate systems that both buy time via safety-preserving degraded-mode actions and support rapid situation awareness during the alert-to-override window.

To our knowledge, there is no published demonstration of robust one-operator to multi-vessel supervision with acceptable performance in realistic conditions. In this work, we adapt the ROC prototype from Gusev et al. (2025) for our experiments and use Endsley’s SA lens (perception, comprehension, projection) as a framing when designing the graphical user interface used in the formative HMI experiment in Sec. 6 (Endsley, 2023). We do not explicitly test one-to-many supervision, but see this system as one of the steps toward it.

FM/LLM UIs in maritime. Prior work explored LLM-based conversational mission planning with the operator explicitly in the Master role (Christensen et al., 2025). Separately, a simulator study of a VHF conversational interface found lower trust than a human officer and argued for tighter coupling to autonomy and retained ROC oversight (Hodne et al., 2024). Our focus differs from these: we target the ODD/OE alert window with VLM-driven, world-anchored actions.

Our approach. We contribute an IMO MASS Code-aligned anomaly-handling method for the interval between alert and override that proposes a single cautious fallback maneuver (or abstains) with brief rationale, preserves immediate override, and is intended to help buy time and reduce operator time pressure in the alert→override window. This is aimed at making supervision of multiple vessels by one operator feasible, even though we evaluate a single vessel here. All closed-loop experiments run on the Shore Control Lab workstation from Gusev et al. (2025). This is to our knowledge the first use of foundation models in the real maritime domain used for anomaly handling specifically and for vision-to-action in general (one single exception comes close to the latter, which runs a rudimentary and simulated VLM vision to action ASV stack (and no anomaly detection or handling) (Kim and Choi, 2025)).

Perception. Some common camera-based maritime perception methods include (i) semantic water/obstacle segmentation to obtain a navigable-water mask, and (ii) object detection to localize and classify vessels and other targets. Representative segmentation approaches include Water Segmentation and Refinement (WaSR) and its embedded variant (eWaSR), along with inland/canal variants that can handle reflections, wakes, and narrow channels. Joint detect-and-segment models have also been demonstrated on edge hardware (Bovcon and Kristan, 2022;Teršek et al., 2023;Zhou et al., 2022;Yang et al., 2024). On the detection side, YOLO-family models trained on domain-specific datasets (e.g., SMD/SMD-Plus, SeaShips) offer real-time performance but remain constrained by narrow taxonomies and out-of-distribution brittleness (Kim et al., 2022), with many rare or ad hoc hazards (e.g., diver-down flags, fire) lying outside the training distribution.

Collision avoidance. Representative COLREGs-compliant collision avoidance methods formulate the problem as a scenario-based MPC (SB-MPC): at each step, a finite set of course/speed behaviors is simulated and scored by a cost that blends collision risk, COLREGs penalties, and maneuver effort (Johansen et al., 2016;Hagen et al., 2022). In deployed stacks, SB-MPC is typically fed by multi-target tracks from AIS/radar fusion before optimization (Hem et al., 2024). Surveys place SB-MPC alongside velocity-obstacle methods, potential-field/gradient methods, and graph/sampling-based planners; these approaches are fundamentally geometry-and rule-centric, encoding COLREGs (IMO, 2018) over kinematics rather than interpreting semantic cues and scene meaning (Zhang et al., 2021;Öztürk et al., 2022).

Our approach. Our system is a camera-only proof-of-concept: eWaSR water masks gate a world-anchored candidate set, and our VLM fallback maneuver selector selects among admissible candidates based on scene meaning instead of only geometry or predefined categories. For baseline comparison, we evaluate simple geometry-only, semantics-agnostic heuristics on the same gated candidate set (Keep-station / Keep-course / Keepstarboard / Forward / Clearance). This is a camera-only simplified proxy to SB-MPC and similar systems for our proofof-concept scope. Selected behaviors are executed by a standard dynamic positioning (DP) system with line-of-sight (LOS) guidance and azimuth-thruster control allocation on our vessel (see Appendix B and Tufte et al. (2026); Brekke et al. (2022) for details).

Foundation models (FMs) (Bommasani et al., 2021), such as LLMs and VLMs, have enabled semantic reasoning across various autonomous systems, including manipulation (Kim et al., 2024;Bjorck et al., 2025;Octo Model Team et al., 2024), navigation (Shah et al., 2023a,b), aerial systems (Saviolo et al., 2024), and long-horizon planning (Driess et al., 2023). These models have been used to bridge natural language instructions and visual input with physical plans and actions (Stone et al., 2023), generate code that can act as control policies (Liang et al., 2023), and construct reward functions (Yu et al., 2023). Various prompting strategies have been developed to elicit actionable knowledge from off-the-shelf VLMs, including iterative visual goal prompting (Nasiriany et al., 2024), keypoint prompting (Huang et al., 2025;Deitke et al., 2025), selecting from predefined skill libraries (Ichter et al., 2023), and anticipating failure modes (Ganai et al., 2025). Vision-languageaction (VLA) models trained end-to-end for robotics have been developed (Zitkovich et al., 2023;Black et al., 2025), but they often suffer from limited training data and lower generalization compared to large-scale VLM counterparts trained on internetscale data (Radford et al., 2021). These generalist policies face deployment challenges including latency, safety verification, lack of interpretability, and domain adaptation (Ren et al., 2023a;Sinha et al., 2024).

Our approach. In safety-critical domains such as maritime autonomy, regulatory frameworks like the IMO MASS Code mandate strict requirements on human oversight and explainability. We propose that pairing zero-shot semantic reasoning from offthe-shelf VLMs with the reliability of classical autonomy stacks offers a pragmatic path forward, leveraging the complementary strengths of foundation model reasoning and domain-specific perception-planning architectures.

2.4. Robotic out-of-distribution detection and safety response OOD Detection. While deep learning systems have powered great advances in robot autonomy, such autonomous systems still struggle on rare and unexpected corner cases (Sinha et al., 2022;Geirhos et al., 2020). Simply enumerating and controlling the ODD of ML-based robots is challenging, as a model’s region of competence is implicit in its training data. Therefore, to alleviate the need for constant human supervision, many robotics works have proposed so-called out-of-distribution detectors in recent years (e.g., see Sharma et al. (2021); Lakshminarayanan et al. (2017); Ruff et al. (2021)). These algorithms aim to detect anomalous conditions wherein model performance degrades so that a safety response can be triggered. While many works aim to detect component-level degradation, like when a perception model degrades in bad weather (Sinha et al., 2023;Gupta et al., 2024;Filos et al., 2020;Richter and Roy, 2017), some recent works introduce runtime monitors that detect contextual, semantic anomalies and reason about the appropriate safety intervention using LLMs and VLMs (e.g., see Elhafsi et al. (2023)). These works demonstrate promising results leveraging the general common-sense reasoning capabilities of foundation models (FMs) to handle scenarios that would otherwise require human judgment. Our goal is to validate these capabilities in the maritime domain and thereby establish anomaly handling as a valuable use case of FMs in maritime autonomy.

Maritime anomaly detection. Maritime anomaly detection has mainly been studied for traffic surveillance and Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) decision support, where anomalies are deviations or inconsistencies in AIS-based trajectories and behavior (Riveiro et al., 2018;Wolsing et al., 2022;Stach et al., 2023). Related work for MASS considers detecting abnormal surrounding vessels from AIS/GIS features (Tyasayumranani et al., 2022), while onboard monitoring targets propulsion/engine-room faults from vibration and other machinery signals (Jeong et al., 2023;Öster, 2024). To our knowledge, no current work addresses onboard camera-based perception anomalies or FM-based contextual anomaly handling for maritime autonomy, which is our focus.

Two challenges must be addressed to practically integrate FMs into real-time decision making. First, querying state-of-the-art FMs like GPT-5 incurs significant latency and constantly querying such models is expensive. Therefore, we follow (Sinha et al., 2024), which proposes a “thinking fast and slow” approach wherein a fast, cheap anomaly detector runs in real-time and triggers the slower reasoning of a FM only in the event of an unusual situation. Second is to bridge the gap between the high-level, text-based reasoning of a VLM and the physical actions that the autonomy stack should execute to maintain safety. In (Ren et al., 2023b), the authors assume the system can freeze in place to await a human takeover when the robot is uncertain. In contrast, other works execute fully autonomous recovery behaviors by making the FM choose from a predefined set of safety interventions (Sinha et al., 2024) or by using additional VLMs to identify safe alternate goals (Ganai et al., 2025).

Our approach. The existing methods cannot however be directly used due to the unique considerations in the maritime do-

Point in camera frame (depth coordinate is main. In particular, a) the MASS Code (IMO, Maritime Safety Committee, 2024) necessitate a handover to a human, excluding fully autonomous recovery behaviors, and b) stopping a vessel to await a human takeover is not always possible or can even increase safety risks. Instead, we propose a novel framework wherein a VLM bridges the gap between the detection of an anomaly and operator takeover by reasoning over and executing short-term keep-safe behaviors.

We consider an autonomous surface vessel (ASV) with a forward-facing monocular camera and a nominal waypointfollowing system under human authority. An exogenous alert at time t alert triggers a one-shot fallback maneuver decision (this alert is based on the existing fast anomaly detection method adapted from Sinha et al. (2024) and validated for the maritime domain in Appendix A). Throughout the paper, a fallback maneuver denotes the short-horizon, operator-overridable action executed in the alert-to-override interval, and the fallback maneuver selector denotes the module that chooses it from a pre-vetted candidate set. During this alert, we assume that the system has the following information (see also Table 1 for description of symbols):

- A calibrated camera image I, 2. an identified water mask W = Seg(I), where Seg() defines the segmentation function returning 1 for water and 0 for anything else, 3. a pixel-space clearance map on Ω, i.e., the minimal distance (in the image plane) to shore or other identified objects in the water, given by

From this, we generate a finite set of K short, straight, and feasible motion primitives proposed ahead of the vessel. The feasible motion candidates are paths in the water and contain a minimum safe margin. Their projected samples (via the known camera model) satisfy for all visible samples u,

for a margin d min (pixels). The retained set of motion primitives is indexed {1, . . . , K}, with 0 reserved to Station-keeping.

Problem formulation. The fallback maneuver selector selects a single action a ∈ {0, . . . , K} once at t alert from the overlaid view; no replanning occurs within the episode. The selected action is executed at a cautious anomaly-mode speed until termination by human override or alert clearance; operator authority strictly dominates autonomy. We assume camera-only perception and start-from-rest. We evaluate (i) human alignment of the chosen action (and scene understanding) and (ii) short-horizon directional risk relief on the same overlays.

Here we show how our implementation instantiates the oneshot fallback maneuver selection problem posed in Section 3 as a concrete, camera-only method executed at the alert rising edge t alert . From a single calibrated camera frame, we (i) compute a conservative water mask and a pixel-space clearance map, (ii) generate and gate short straight motion trajectories in the boat frame, (iii) render a numbered overlay ({1, . . . , K} with 0 denoting Station-keeping), (iv) query a vision-language model (VLM) once to select a fallback action, (v) and publish either a Station-keeping point or a world-fixed path to a lineof-sight waypoint follower. Operator input always has priority (MANUAL > AUTONOMY). The same overlay/gating stack is used both for offline evaluation and closed-loop field testing, with only vehicle-specific execution and override being different (see details in section 5). The remainder of this section is divided into the following three components: Trajectory candidate generation and gating (Section 4.1), VLM fallback maneuver selection (Section 4.2), and Execution and arbitration (Section 4.3), as illustrated in Fig. 1.

At the alert rising edge t alert , we operate on a single calibrated forward image I. We use four coordinate frames, see Fig. 2: the image plane Ω ⊂ Z 2 with pixel coordinates u = (u, v), a body-fixed horizontal frame {b} with p b = x y 0 ⊤ (x forward, y lateral starboard), a camera frame {c}, and a local North-East-Down (NED) world frame {n}. The calibrated projection from frame {b} to Ω uses an intrinsic matrix K, and the transformation from body frame {b} to world frame {n} uses an extrinsic transformation by translation r b nb (position of the vessel relative to the NED-frame given in the body frame) and rotation matrix R n b ∈ SO(3):

(

The above is valid when p c 3 > 0 and u ∈ Ω (in front of the camera, in-frame). All selection and gating in this subsection happens in Ω, putting candidates into {n} happens later in Sec. 4.2.

Water and clearance. From the image I we compute a conservative binary water mask

using the embedded Water Segmentation and Refinement (eWaSR) maritime segmentation model (Teršek et al., 2023), and a per-pixel clearance map (Euclidean distance to the nearest non-water pixel) using Eq. (1). A narrow bottom band is treated as trivially water to ensure connectivity at the hull.

Sampling and projection. We sample N raw straight motion primitives in {b} from a fixed local anchor at the bow (4.0, 0.0) m to endpoints drawn in an annulus r ∈ [R min , R max ] within a forward half-angle |ϕ| ≤ ϕ max . Each primitive is discretized into N ℓ points in B and projected via (3). A sample is visible if p c 3 > 0 and u ∈ Ω. Let k 0 be the first visible index; the endpoint pixel must also be visible.

Require: Pixel-space gating. A candidate is retained if every visible projected sample from k 0 to the endpoint satisfies

This enforces that the commanded segment lies entirely on water with a pixel margin, without requiring world geometry or multi-sensor fusion.

Thinning and indexing. From the surviving set, we select up to K primitives by farthest-point thinning on endpoint pixels to promote spatial spread (Appendix,Alg. 3). Candidates are indexed as {1, . . . , K} (ID 0 is reserved for Station-keeping). We use K = 15 and d min = 40 px in both offline evaluation and live field tests. Here d min = 40 px is an image-space clearance margin used as a conservative camera-only proxy to reject candidates whose projected samples pass too close to non-water regions. A fixed pixel margin corresponds to a larger physical separation for more distant boundaries, so it is most critical in the near field. In a production system this gating module would naturally be replaced or augmented by range-aware perception (e.g., stereo, LiDAR, radar) without changing the remainder of the Semantic Lookout fallback maneuver selector.

The whole generation and gating algorithm is summarized in Alg. 1.

Input and output schema. The model receives only the overlayed image O with labeled candidates {1, . . . , K} (ID 0 denotes Station-keeping) and an instruction prompt (see Appendix E). It returns a single strict JSON object {“see”:"<= 15 words", “implications”:"<= 15 words", “action”:"<= 15 words (no ids)", “choice_id”: 0..K, “confidence”: 0..1}

We parse and connect choice_id to {0, . . . , K} (invalid JSON maps to Station-keeping (choice_id = 0). The free-text fields (see, implications, action) are logged for analysis and are also used with the operator UI to support situational awareness in the formative handover study (Sec. 6).

Failure handling and safe defaults. The fallback maneuver selector is invoked only after an external anomaly alert at t alert . It is therefore a post-alert safety module: it does not guarantee anomaly detection, and missed or late alerts are handled by the nominal autonomy stack and the upstream alerting monitor (Appendix A). Within the fallback maneuver selector itself, we implement conservative safe defaults for three failure modes. (i) If the VLM call times out, returns an API error, or produces an invalid or non-conforming JSON object, we set choice_id = 0 (Station-keeping) and notify the ROC. (ii) If the candidate generation/gating yields no feasible motion candidates (i.e., K = 0 after gating), we likewise default to Stationkeeping and notify the ROC. (iii) If voting in FB-n produces no strict majority (ties, see below), we default to Station-keeping by design. In all cases, joystick override remains available at all times and dominates autonomy.

Runtime single-shot selection (FB-1). We issue one call per alert. Let f θ denote the VLM and let y = f θ (O); the executed action is

and is applied once within the episode (no replanning).

To probe robustness, we evaluate n independent calls on the same overlay O with distinct seeds {η s } n s=1 :

We aggregate by strict majority of n (ties ⇒ Station-keeping):

Where a s ∈ {0, . . . , K} is the ID from the s-th stochastic call, c k = |{ s : a s = k }| counts votes for candidate k, arg max k c k returns any maximizer, and ID 0 denotes Station-keeping. We refer to the runtime selector as FB-1 and the evaluation ensemble as FB-n. In all experiments, we use n=3 (FB-3, see Sec. 5). Sampling multiple test-time rollouts and aggregating by majority follows standard self-consistency / test-time compute-scaling practice in LLM reasoning (Wang et al., 2022).

Temporal anchoring. Candidates are frozen in the world frame at t alert using the navigation pose T N←B (t alert ). At command issue, we re-project those world-fixed polylines for visualization and publish the world-fixed geometry to the controller. This decouples perception/decision latency from actuation while preserving the action space from Sec. 4.1.

The whole fallback maneuver selector algorithm is summarized in Alg. 2. Operator override. Let τ d denote the desired actuation after arbitration, τ m the autonomy (motion) command, τ h the human (joystick) input, and α ∈ [0, 1] a blending factor (see Fig. 4). We use a direct blend that guarantees at least 50% human authority and ramps to full override:

Here, the blending factor α determines

We do this to enable continuous control and a seamless transition between vessel and operator in Sec. 6, and to revert back to fully autonomous control in case of loss of signal midtransition. Details of the α schedule transitions are specified in Appendix B.1.

In this section we evaluate the method on camera overlays at alert time, using the candidate generation and gating stack (and control/arbitration where applicable) described in Section 4. We structure the evaluation around a series of experiments that test the following four hypotheses:

• H1 (Scene understanding). Modern VLMs can correctly recognize semantic, marine-specific, hazards and their implications, and propose appropriate high-level action descriptions, at latencies that are usable in the alert→override handover window.

• H2 (Action alignment with human choices). The corresponding fallback maneuvers selected from these action descriptions align with aggregated human “Acceptable/Best” judgments on the same overlays, outperforming simple geometry-only baselines.

• H3 (Risk-relief).

On unambiguously dangerous fire scenes, the fallback maneuver selector selects short-horizon actions that increase separation from the hazard relative to keep-course/starboard geometry-only baselines.

• H4 (Integrated field test and handover). The full alert→fallback maneuver→override chain can be executed on a real vessel with immediate joystick override and a ROC-legible user interface (UI), consistent with IMO MASS Code constraints.

Experiment rationale. We run four main experiments, corresponding to each respective hypothesis. Experiment 1 (Sec. 5.2) evaluates scene understanding: given a single overlaid camera frame and a strict output schema, can models describe the hazard, its implication, and a safe high-level action, and how does this trade off with latency? Experiment 2 (Sec. 5.3) evaluates to what extent the selector’s chosen trajectory IDs under FB-3 agree with human judgments on the same overlays, using aggregated Accept/Best sets to approximate “reasonable” actions in semantic anomalies. Experiment 3 (Sec. 5.4) focuses on the unambiguously dangerous fire subset, measuring short-horizon directional risk relief versus geometry-only baselines. Experiment 4 (Sec. 5.5) closes the loop on water, testing the full alert→fallback maneuver→override chain on a real ASV with ROC supervision. Each (model, scene) is run n times with distinct seeds. Unless stated otherwise, we use n=3 (FB-3) and aggregate by strict majority (ties ⇒ Station-keeping). Single-shot results (FB-1) are reported where relevant. Models receive only the numbered overlay image and an instruction prompt, no additional geometry or labels are provided at inference time.

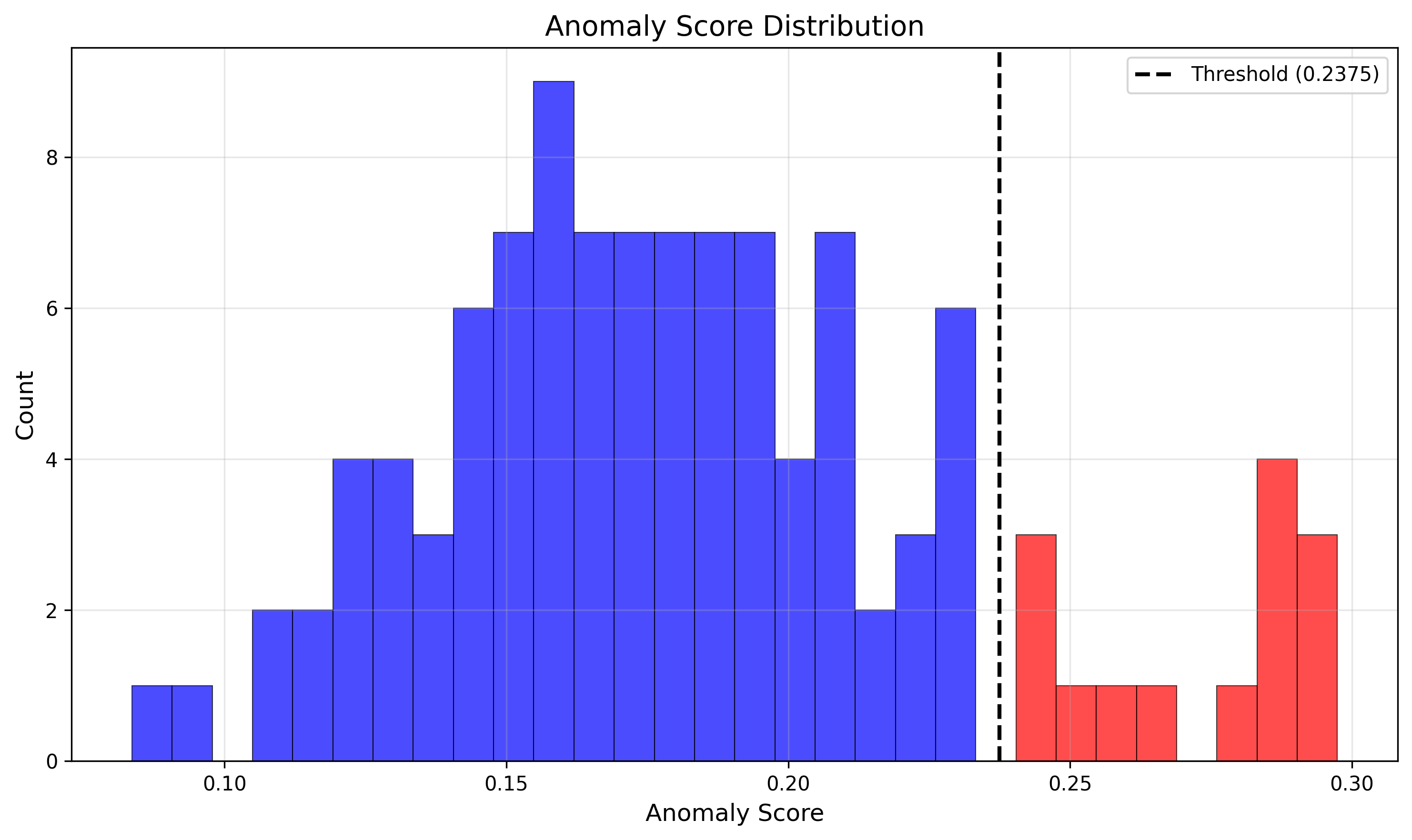

In Appendix A, we also evaluate the fast alert of our alert→fallback maneuver→operator system (an established fast anomaly detection alert method adapted from Sinha et al. ( 2024)), to validate that it also works, given the distribution shift for the maritime domain. 4. Custom signs (AI-enhanced): e.g., keep-out or restricted-area signage inserted into vessel-captured frames.

We collect 10 scenes per category. For AI-enhancement, we use Gemini 2.5 Flash Image (Fortin et al., 2025) on frames from the real vessel, which are treated identically to real scenes. This enables testing anomalous situations that would have been dangerous or impractical otherwise. Representative real and enhanced example scenes are shown in Figure 7.

Model grid and run protocol. In Experiments 1 and 2 we evaluate a diverse set of vision-language models and inference settings shown in Table 2. Specific models are chosen for Experiments 3 and 4 based on performance in the first two. For each (model, scene) we issue three calls with distinct seeds to assess stability (strict-majority voting as above). We use a conservative prompt that advises Station-keeping when uncertain (alternative prompts, neutral/proactive, are ablated in Appendix E.2). For every call we record end-to-end latency.

Reporting conventions. We report 95% confidence intervals where relevant. For proportions (e.g., Accept@1, Best-set@1) we use the Wilson interval and write p [L, U]. For continuous outcomes (e.g., awareness score, latency) we report the mean ± 95% CI. Pareto scatter plots omit intervals to reduce clutter; the corresponding leaderboards/tables include them.

Overview and method. Experiment 1 evaluates whether, given the overlaid image and strict output schema, models accurately describe the hazard, its safety implications, and a high-level safe action, and how this trades off with latency. This addresses H1 at the level of textual scene understanding, independent of the specific candidate ID (which is evaluated separately in 5.3).

Each scene is associated with a short human-labeled ground truth that describes the hazard, implications and high-level safe behavior. We compare model output to ground truth with an LLM-as-judge configured as GPT-5-low (see Gu et al. (2024) for an overview of LLM-as-judge as a method). The judge is provider-blind and sees only the textual ground truth and model output (not image, candidates etc.) It also tolerates synonyms and penalizes off-topic or unsafe recommendations (see Appendix E.3 for the specific LLM-as-judge prompt).

The judge emits three component scores with fractional credit in [0, 1]:

- Hazard recognition (1.0 = explicitly correct cue, 0.75 = clearly implied, 0.5 = generic hazard, 0 = wrong/missing). 2. Implication (does the text state why it matters for safety, e.g., people in water, restricted area, fire risk). 3. Action (is the proposed high-level maneuver broadly consistent with ground truth, independent of choice ID).

We aggregate to a single awareness score in [0, 1] with fixed weights:

Reasoning is evaluated per call (FB-1, all three seeds). For each (model, anomaly) and overall, we report (i) the mean awareness score and (ii) the mean end-to-end model latency.

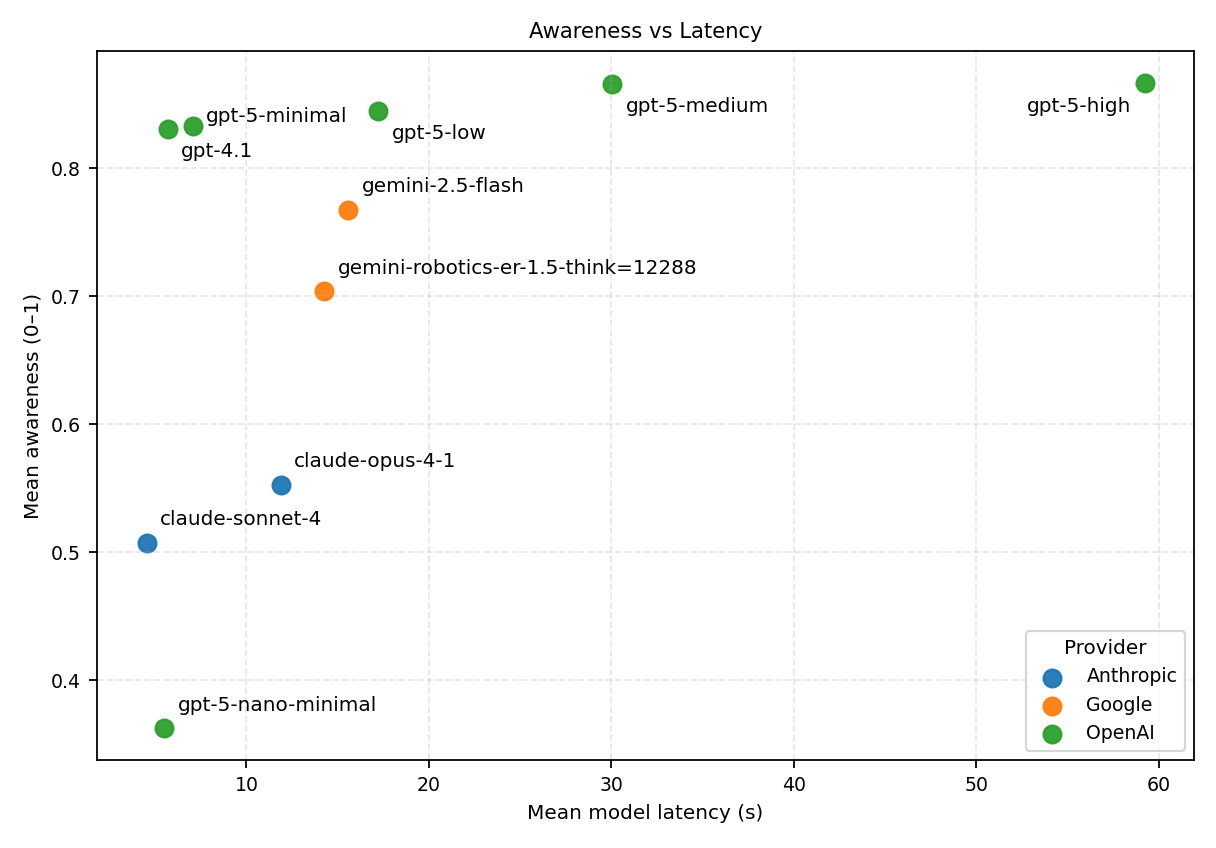

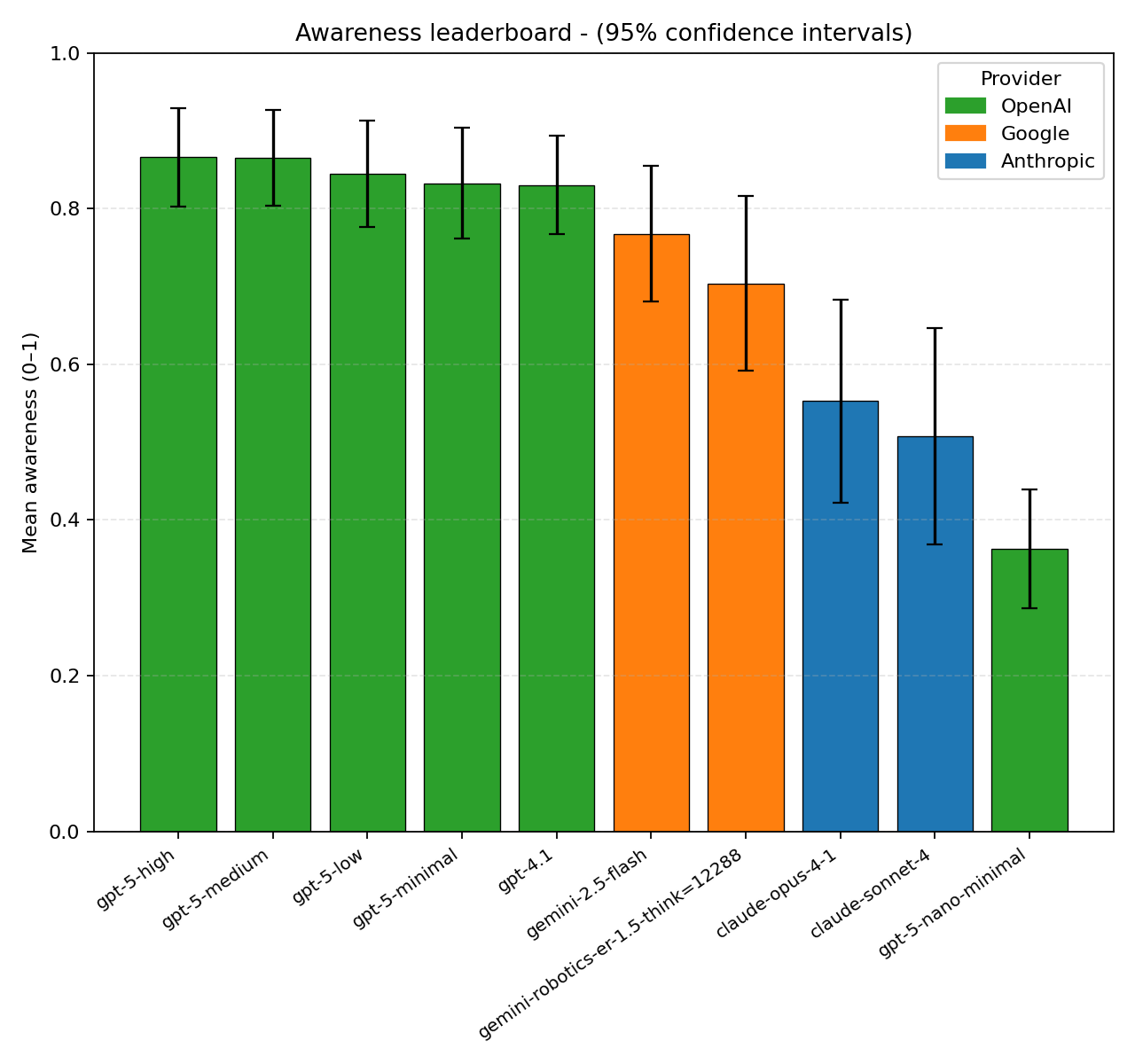

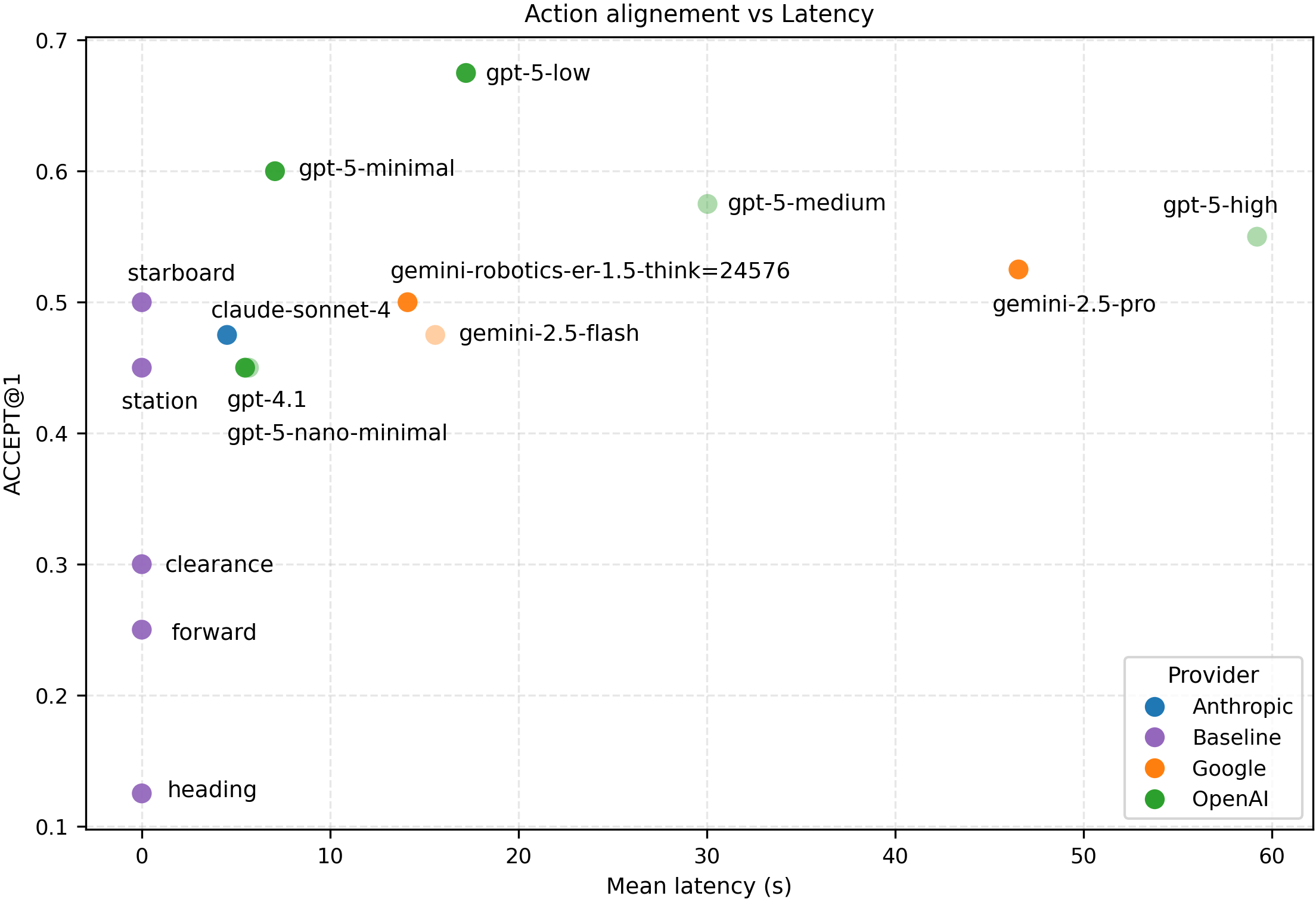

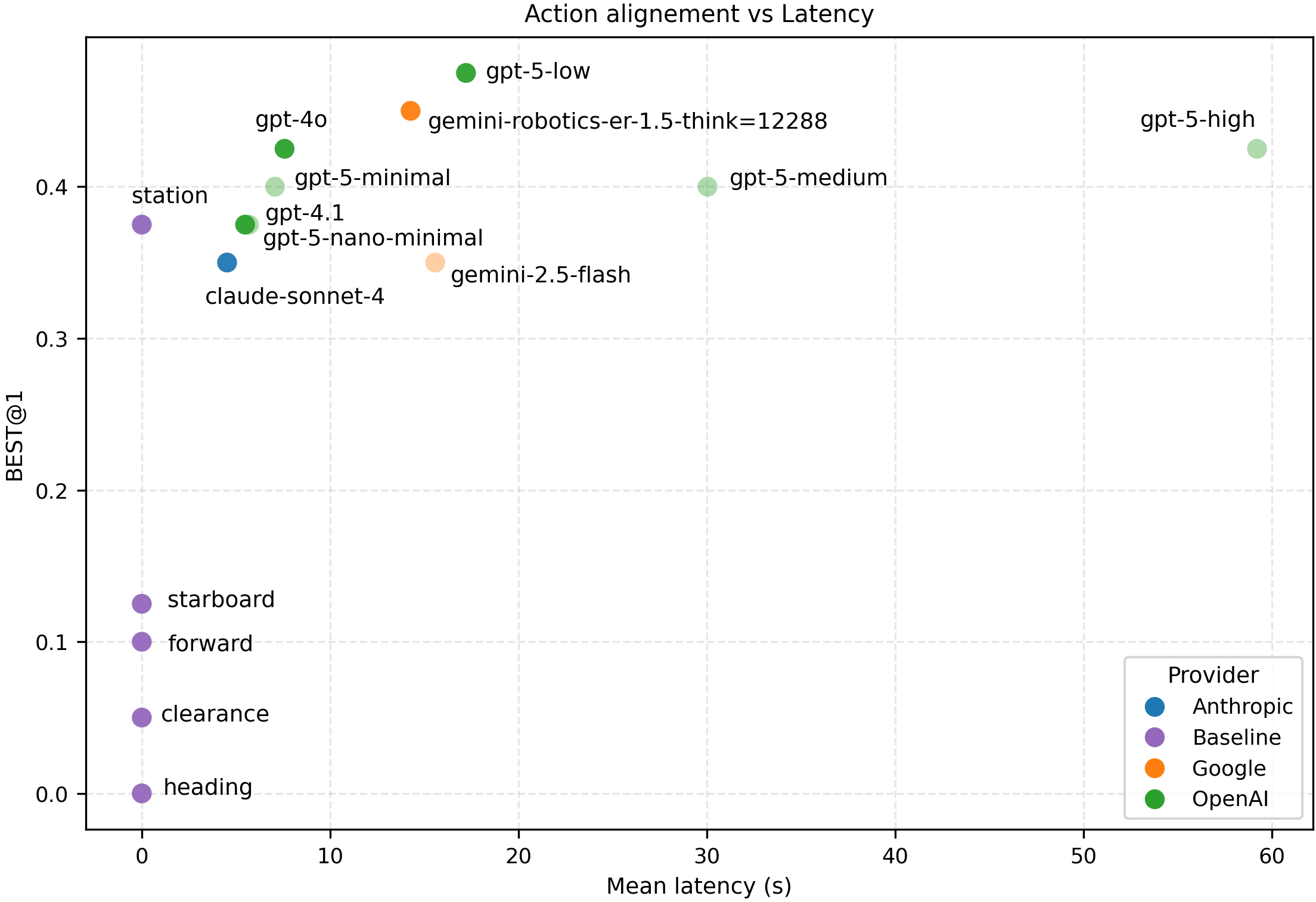

Results and analysis. We evaluate per-call scene understanding (hazard, implication, action) using the LLM-as-judge protocol above and report mean awareness and end-to-end latency across the 40 scenes (10 per anomaly). Figures 8 and9 summarize the awareness-latency Pareto frontier by provider. Error bars in Figure 9 show 95% confidence interval (CI).

OpenAI models show overall best performance: gpt-5-high shows the highest mean awareness (0.866 ± 0.063) at 59.2 ± 4.0 s, while strong sub-10 s alternatives, gpt-4.1 (0.830 ± 0.063 at 5.69 ± 0.22 s) and gpt-5-minimal (0.833 ± 0.071 at 7.07 ± 0.47 s), provide most of the performance at much lower latency (Table 3). Incremental gains beyond ∼30 s are within CI (like gpt-5-medium at 0.866 ± 0.062 at 30.0 ± 1.9 s vs. gpt-5-high).

The best non-OpenAI frontier points are gemini-2.5-flash (0.768 ± 0.087 at 15.6 ± 1.1 s) and gemini-robotics-er-1.5 think=12288 (0.704 ± 0.112 at 14.3 ± 0.6 s), while Anthropic’s fastest frontier point is claude-sonnet-4 (0.507 ± 0.139 at 4.53 ± 0.11 s). The best models mostly span from ∼5-7 s at ∼0.83 awareness to ∼60 s at ∼0.87 awareness score.

Across the Top-5 frontier entries, hazard, implication and action scores are generally high and balanced (Hazard: ∼0.83-0.87, Implication: ∼0.81-0.85, Action: ∼0.84-0.88) (Table 3). Appendix E.5 shows the results for all models tested. 11.7% for Signs and 1.4% for Fire. In the low-awareness subset, mean rubric subscores are low for scene understanding and implications (see/hazard: 0.16, implication: 0.18), while action is higher (0.33), indicating that the dominant root cause is missed or misinterpreted hazards rather than fine-grained action disagreement. Notably, even among low-awareness outputs, models sometimes propose plausible generic maritime actions (e.g., “slow down” / “keep clear”) without correctly identifying the cue, which can make the text appear reasonable while being semantically ungrounded. Typical recurring modes are: missed anomaly (no grounding), misidentification as a benign buoy/marker/clutter, a generic COLREG-like caution template, and implication gaps (e.g., noticing a flag/shape but not inferring divers or rescue constraints).

Takeaways. These results support hypothesis H1: modern VLMs can achieve high maritime scene awareness at practical latencies, with sub-10 s models retaining most of the awareness of much slower systems. When the selector correctly recognizes the hazard, the resulting rationale is specific enough to support explainable handovers in the ROC GUI, while remaining failure modes are dominated by subtle, low-salience cues such as the alpha diver flag and small, distant MOB targets.

Overview and method. Experiment 2 evaluates whether the picked trajectory ID under FB-3 matches what humans consider reasonable actions on the same overlays. Because these semantic anomalies involve value-laden tradeoffs and partial observability from only a single camera view, there is no unique ground-truth “correct” action label. Instead we treat aggregated human judgments as a proxy for reasonable behavior in cases where geometry alone is insufficient. Human raters mark any number of Acceptable candidates and select a single Best candidate. The Station-keeping option (ID 0) is available and treated like any other candidate. Each scene is rated by N ≥ 11 raters. For rater r, let A (r) ⊆ {0, . . . , K} be the Acceptable set and b (r) ∈ {0, . . . , K} the Best pick. “None acceptable” is treated as abstention and set to Station-keep.

To form the Acceptable consensus we define the acceptance frequency

and set

To allow for scenes with more than one defensible “best” action (e.g., stop near a MOB vs. steer away), we permit up to three Best items when support is split across strong contenders.

We first count “best” votes per candidate:

Let the top vote count be

We require each Best item to clear a threshold that encodes two simple safeguards: (i) it must be reasonably competitive with the top option (at least half as many votes), and (ii) it must have a non-trivial minimum of raters (at least one quarter of N):

Candidates meeting this support are retained,

(16) If |BEST| > 3, we keep the three items with largest v k (ties broken by larger pk , then smaller ID). This results in one to three “best” choices when raters split between a small number of strong alternatives, while still filtering outlier picks. Qualitative inspection of per-scene ACCEPT and BEST sets shows reasonable results (see Appendix E.4

Metrics and baselines. Each (model, scene) is run three times with distinct seeds; unless otherwise stated we report majorityof-three (FB-3). We measure:

• Accept@1: fraction of scenes where the chosen ID lies in the human consensus ACCEPT set.

• Best@1: fraction of scenes where the chosen ID lies in the human consensus BEST set.

These metrics explicitly tie the model’s action to what humans regard as acceptable or preferred among the pre-vetted candidates. Purely geometric metrics like distance to shore or relative bearing would not capture semantics such as divers, signage, or people in the water. By aggregating raters, we approximate the notion of “reasonable behavior” in these ambiguous, meaning-dependent scenes.

We compare the selector method to geometry-only baselines, which operate on the identical, gated set: Station-keep (always pick ID 0); Keep-course (pick the candidate with the smallest bearing relative to vessel heading, |ϕ k |); Keep-starboard (pick the most starboard gated trajectory); Forward (maximize forward displacement (x) of the endpoint); Clearance (maximize the minimum pixel-space clearance along the candidate’s projected samples).

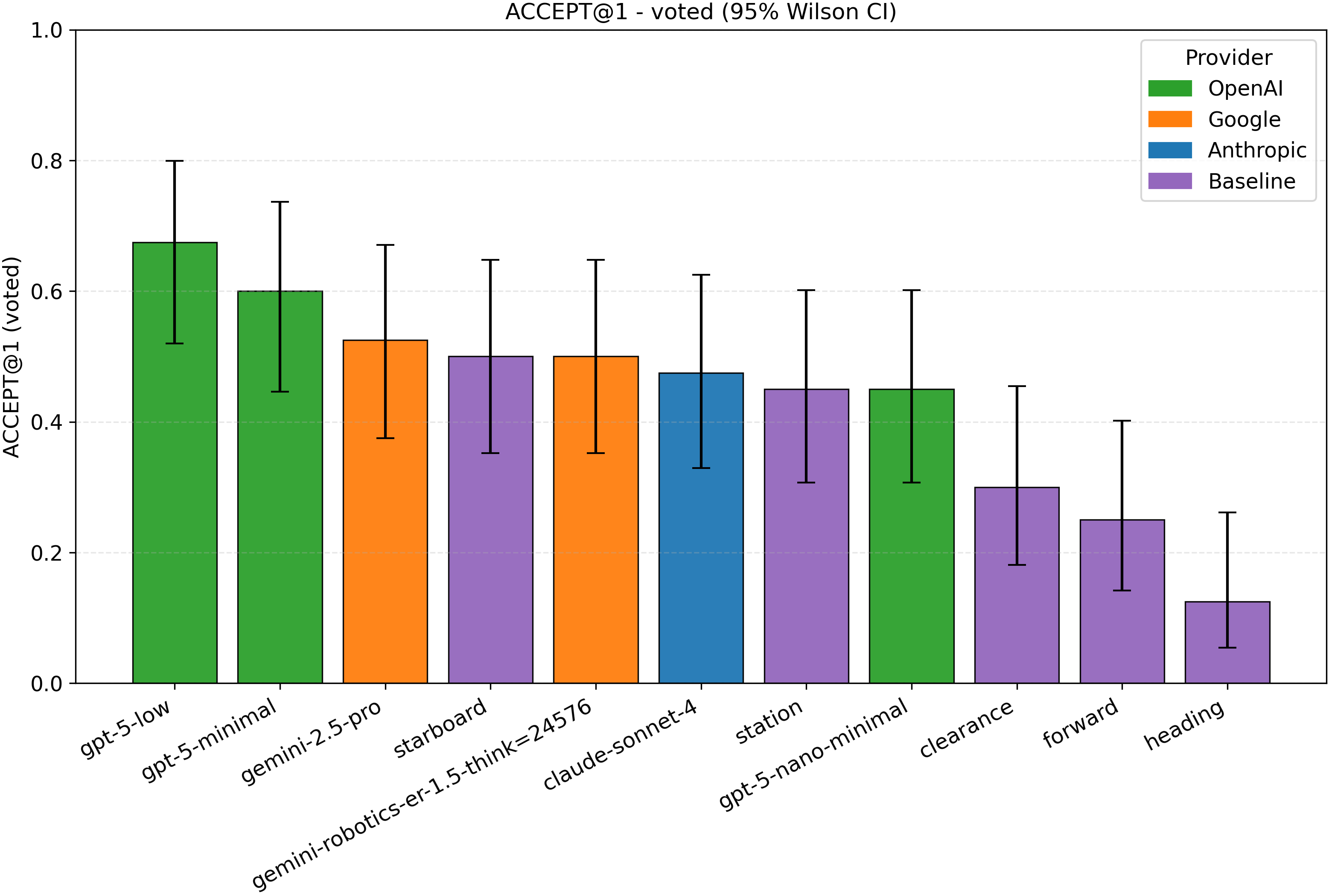

Results and analysis. We evaluate whether the picked candidate aligns with the human consensus Accept and Best sets on the same overlay, using FB-3. Geometry-only baselines operate on the same, gated set of candidates (Keep-station, Keepstarboard, Keep-course, Forward, Clearance) as defined above.

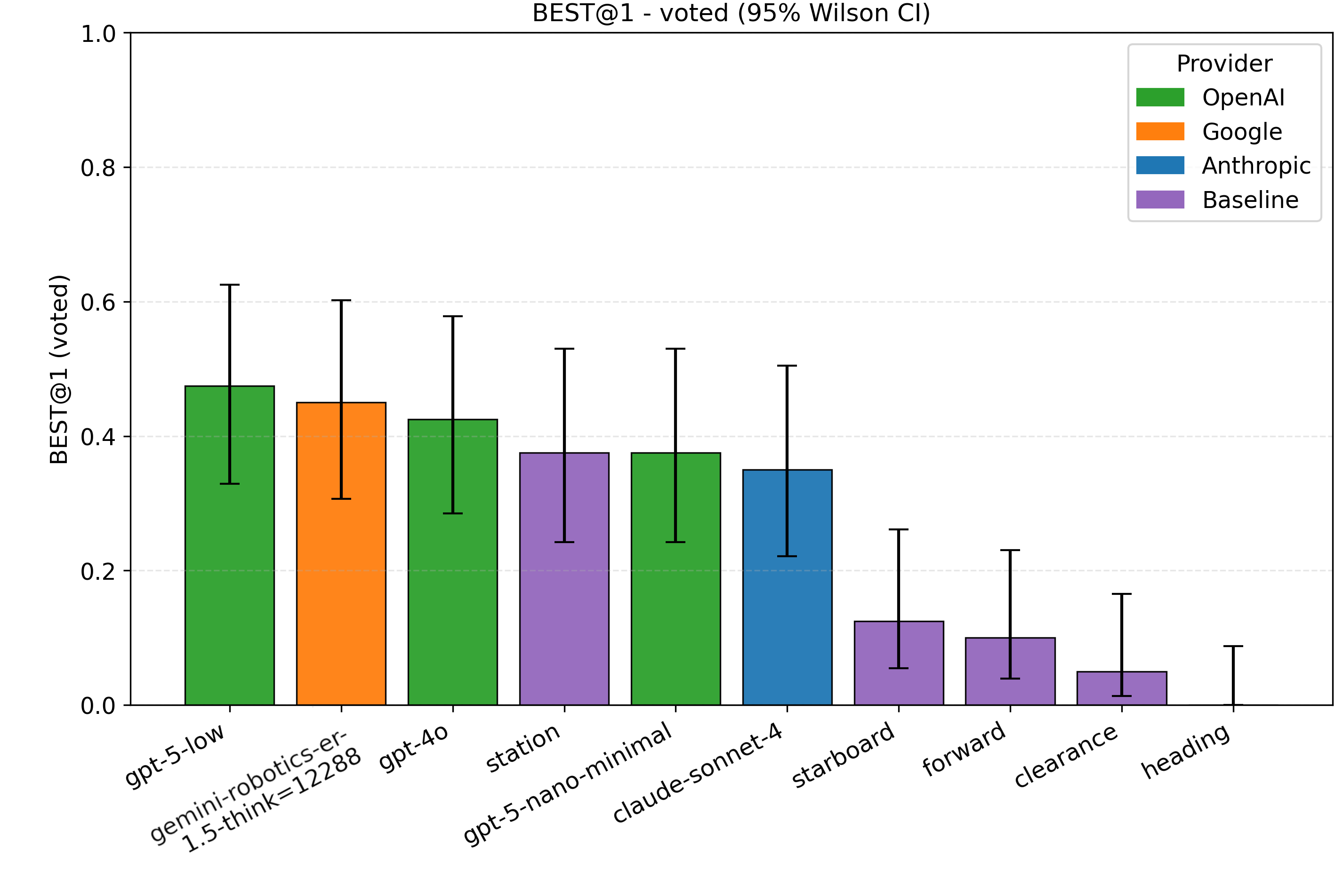

Figures 10 and11 show per-provider Pareto frontiers for action alignment versus mean latency, all baselines are included and are plotted at zero latency. Models that were on the frontier in Fig. 8 (scene understanding) but are not on the current frontier appear as transparent carryovers for reference. The leader boards in Figures 12 and13 similarly show frontier models (but not carryover) and baselines, with 95% Wilson CIs.

Across the full set of scenes, the best overall model on both metrics is gpt-5-low, which we therefore use for FB-3 in the risk-relief analysis in Experiment 3. Its FB-3 results are Accept@1 = 0.68 [0.52, 0.80] and Best@1 = 0.48 [0.33, 0.63] at a latency of 16.1 s (Table 4). In the sub-10 s region, gpt-5minimal achieves Accept@1 = 0.60 [0.45, 0.74] and Best@1 = 0.40 [0.26, 0.55] at 6.7 s, while gpt-4o yields Accept@1 = 0.55 [0.40, 0.69] and Best@1 = 0.43 [0.29, 0.58] at 5.8 s. These provide strong and fast alternatives with a modest drop from the overall best. Like in Experiment 1, OpenAI models dominate the frontier.

Because Station (ID 0) appears frequently in the human consensus, baseline Keep-station is relatively competitive: it obtains Accept@1 = 0.45 [0.31, 0.60] and Best@1 = 0.38 [0.24, 0.53] (Table 4). This also highlights the general dataset composition: Station is in the rater Accept set for 45% of scenes and in the Best set for 37.5% of scenes. In contrast, Keep-starboard is often acceptable but rarely best (Accept@1 = 0.50 [0.35, 0.65], Best@1 = 0.13 [0.05, 0.26]), consistent with open-water frames and pre-vetted trajectories that already avoid obvious non-water regions. All model and baseline results are in Appendix E.6.

Failure-case analysis and anomaly-specific observations. Peranomaly tables (Fire, Diver flag, MOB, Custom sign) are provided in Appendix E.6.1 -Appendix E.6.4. As in Experiment 1, action alignment spreads are largest on the low-salience categories (Diver flag, MOB) and smaller on Fire/Sign. Typical misalignment modes mirror the scene-understanding failures: missing or misinterpreting the cue (e.g., diver-down marker or distant MOB confused with buoy/clutter) can lead to selecting a candidate that passes too close to the hazard region. A second reason is on the conversion from understanding to concrete action: even when the hazard is correctly described at a high level, mapping that intent to a single numbered best candidate among many options is stricter and requires better grounding than producing a plausible textual recommendation. This is re-flected in a consistent gap between high-level scene understanding and concrete action selection: the best mean awareness in Experiment 1 reaches 0.866, whereas the best overall action alignment here peaks at Accept@1 = 0.68 and Best@1 = 0.48 (Table 4), indicating that selecting an acceptable/best specific short-horizon path is considerably harder for the models than describing the situation and a generic safe response.

Takeaways. The experiment supports hypothesis H2: within our pre-vetted candidate set, the FB-3 selector aligns with human Accept/Best judgments more often than geometry-only baselines, even though Station-keeping and keep-starboard remain competitive in many scenes. This suggests that semantics-not only simple geometric rules-matter in the relatively small set of cases where those defaults would be unsafe, and that action alignment with human consensus is a useful proxy for “reasonable” behavior in such semantic anomalies. The observed gap between awareness and action alignment suggests that translating high scene understanding into concrete safe actions is a key remaining bottleneck.

Table 4: Overall action alignment (FB-3 majority-of-three) with 95% Wilson CIs over N=40 scenes; median latency across calls.

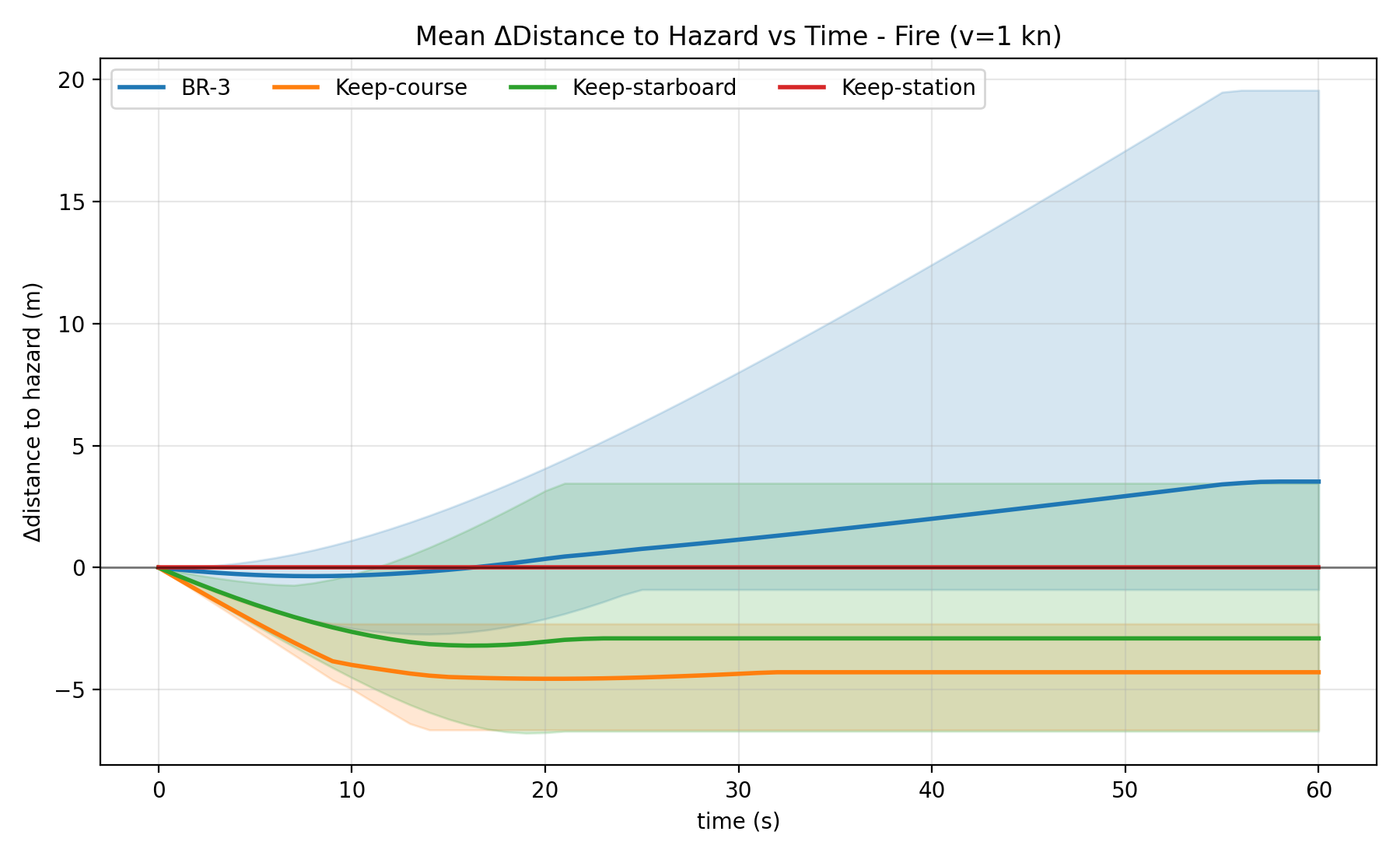

Accept@1 Best@1 Latency Overview and method. In the event of an anomaly detection, the time between alert and human override could be considerable. Experiment 3 asks whether the selector can reason about an unambiguously dangerous hazard and move the vessel toward safety, addressing H3 on directional risk relief. We focus on the fire subset, where the hazard location is well defined. We evaluate the winning selector, FB-3 (gpt-5-low), on short-horizon directional risk relief and compare it to baselines (Keep-station, Keep-course and Keep-starboard) on the unambiguously dangerous fire subset of the dataset. For each scene we annotate a single hazard point h on the water plane, back-projected with the known camera intrinsics and extrinsics from (3), Section 4.1. h is only used for evaluation. We start from the bow anchor x 0 = (4.0, 0.0) m in the boat frame and execute the chosen trajectory at a constant anomaly speed U anom = 0.514 m/s (1 kn) without replanning. If the endpoint is reached early, the vessel stops. This is simulated only and assumes the hazard is stationary.

For a horizon H(s), let x H (p) be the position after straight-line motion toward the chosen endpoint (or x H = x 0 for Keep-station). We measure change in separation

so that positive values indicate increased distance from the hazard (risk relief), negative values decreases distance from the hazard, and Keep-station is always 0. Because fire is unambiguously dangerous and localized on the water plane, this geometric standoff metric directly captures whether a choice moves away from or toward the hazard and is easier to interpret than in the more ambiguous anomaly types where multiple actions could be reasonable for humans.

Results and analysis. We report mean ∆d H across scenes as a function of time and at fixed horizons H ∈ {10, 30, 60} s, and also show min-max values to visualize best and worst runs (Table 5 and Fig. 14). FB-3 yields large positive relief on some scenes while remaining neutral on others, depending on the situation. It outcompetes all baselines, which show mean zero (station) or negative (the rest).

Takeaways. These findings support H3: on unambiguously dangerous fire scenes, the FB-3 method tends to increase standoff distance compared to keep-course, keep-starboard, or Station-keeping, providing directional evidence that the humanalignment result from Experiment 2 translates into shorthorizon risk relief when the hazard is spatially localized and semantically unambiguous. Overview and method. To validate the selector in a real, closedloop system, we ran the end-to-end stack on a real ASV with control and override capabilities as described in Sec. 4.3. This addresses H4 by testing whether the full alert→fallback maneuver→override chain functions under realistic constraints.

We executed n = 5 diving flag scenario runs from the ROC with real human operators who could accept the alert and take manual control. The selector used FB-1 (gpt-5-medium), selected offline because of its high performance on diver-flag scene understanding cases. For each run:

- An anomaly alert was raised (manually for this proof-ofconcept). 2. The selector produced a single action ID and textual rationale, which were shown to the operator together with a map view. 3. The world-fixed path for the chosen candidate was sent to the LOS controller and executed at anomaly-mode speed, with joystick override always available. 4. The operator took control from the ROC and performed a short manual approach and safe stop at the dock.

The same n = 5 sessions are later used for a separate formative handover HMI study (Sec. 6), which analyzes operator experience qualitatively. (3) the operator took control from the ROC; and (4) a short manual approach and safe stop at the dock followed. This is a qualitative demonstration that the alert to handover system executes on real hardware on water. Qualitative HMI findings drawn from the same sessions are reported separately in Sec. 6.

Takeaways. This experiment supports H4 at a proof-of-concept level: the alert→fallback maneuver→override chain can run end-to-end on real ASV hardware with joystick override in a ROC user interface. In practice, the main limitation is VLM latency (around 30 s with the chosen model), suggesting that deployments should pair faster semantic models with the same arbitration and HMI pattern observed in our formative study.

As a complementary evaluation to the closed-loop sea trial in Sec. 5.5, we conducted a small formative handover humanmachine interface (HMI) study on the same diver-flag sessions (n = 5) to understand operator needs during the alertto-override interval. Operators supervised from the ROC, followed a think-aloud protocol during the run, and completed a brief semi-structured interview afterward. Analysis used a qualitative, deductive lens mapped to Endsley’s SA levels (L1-L3), with cross-cuts on workload/attention and trust/mode awareness (Endsley, 2023). The operators had access to a ROC with a wide field of view camera feed with GUI overlay elements, shown in Fig. 6, with additional modules added for our experiment, including the fallback maneuver output and map view like the one shown in Fig. 16. The full experimental protocol is included in Appendix C and the complete report is in Appendix D.

(i) Mode/authority salience needed to be persistent and explicit under time pressure. (ii) Split attention between map and camera pushed operators to request in-view AR overlays (hazard label with distance-bearing, recommended corridor, own-ship path, persistent tracking). (iii) Text brevity and placement mattered: short phrasing was preferred over dense text. (iv) Temporal context (detection/“last seen”, tracking status) would have improved confidence and reduced unnecessary scanning.

The following design principles should be implemented on production systems: Mode/authority should always be visible with explicit transition banners; critical cues should be moved to the camera view with lightweight, continuously updated overlays; the map should be retained for broader context; prefer short, high-value text with expand-on-demand functionality.

Limitations: These are single-scenario tests with small n. The findings are therefore formative only.

Our results suggest that a candidate-constrained VLM fallback maneuver selector can achieve high maritime scene understanding at practical latencies and translate that into action alignment with human consensus. Sub-10 s models retain most of the awareness of slow state-of-the-art models (Sec. 5.2), and FB-3 alignment exceeds geometry-only baselines (Sec. 5.3). On fire scenes, where the hazard is unambiguous, the fallback maneuver selector increases standoff distance relative to keepcourse/starboard baselines as well as the neutral keep-station (Sec. 5.4). A live on-water run confirms that the alert→fallback maneuver→operator handover executes end-to-end (Sec. 5.5), and the formative HMI study highlights how these semantics can be surfaced in a ROC interface (Sec. 6).

High model awareness leads to correct rationales on the ROC GUI overlay, which supports explainable handover: when the fallback maneuver selector recognizes what it is looking at, operators can receive useful, targeted explanations, provided that the user interface makes mode/authority and key cues salient. The HMI study suggests that dense text is limiting under time pressure, and that short, high-value rationales combined with in-view overlays and explicit mode/authority indicators better connect the fallback maneuver selector’s semantics to operator situation awareness.

The relative competitiveness of Keep-station reflects both our specific dataset and maritime reality: in many scenes, stopping is acceptable or even best. Likewise, starboard-only is often acceptable in open water, especially after we have filtered out obviously unsafe candidates. However, the operational risk resides in the few cases where those defaults are not appropriate. There, semantics (e.g., “fire is dangerous; increase clearance” or “divers may be in the water; avoid passing close to the flag”) matter, and the fallback maneuver selector’s alignment with human judgment is a proxy for good decisions in such semantic anomalies. The fire risk-relief analysis provides directional validation of that proxy despite low n by showing that, on clearly dangerous hazards, the fallback maneuver selector tends to increase standoff distance while simple geometry-only defaults can move the vessel closer.

The anomaly types also illustrate where current VLMs struggle. Diver flag and MOB scenes present small, low-salience cues that are frequently confused with buoys or background clutter, whereas Fire and Custom sign scenes are salient and explicit, and most models perform well. AI-edited scenes may also be easier (e.g., increased salience or data distribution overlap), but the dominant factor seems to be subtlety and rarity. The internationally recognized alpha diver flag may be underrepresented in pretraining data, and our blue-buoy mounting is atypical. Consistent with this, longer-latency reasoning models tend to do better on Diver-flag recognition and implications. Ultimately, despite 16 alternatives per scene, the best model selects among the top 1-3 human-preferred actions nearly half the time, indicating good but not perfect alignment. Common failure modes include missing the diver-down semantics, confusing distant MOB targets with buoys/clutter, and selecting conservatively when the safest action is not present in the forward camera-constrained candidate set.

Current constraints of the action space and sensors likely limit overall performance. We project straight-line candidates on a single camera view in front of the vessel. Here we treat K=15 as a pragmatic proof-of-concept choice rather than an optimized value. Selecting the optimal maneuver library and candidate count K is an important direction for future work. Furthermore, the best action might be outside the current field of view, and camera-only gating with a water mask is a proxy for true scene geometry. A multi-sensor bird’s-eye-view (e.g., radar/thermal/lidar) for candidate filtering and prompting, plus short-horizon replanning, should enlarge the reachable safe set and reduce failure modes attributable to missing context. Many of the same limitations apply to the human consensus ground truth; in both cases, the action is chosen from a single 2D camera view. Moreover, the baselines used are also camera-only proxies for real, more advanced, marine collision avoidance systems that fuse multiple sensors.

From an operational and IMO MASS perspective, we treat the fallback maneuver selector as a pre-approved degradedmode safety-maneuver method. On ODD exit, it selects within a pre-approved short-horizon envelope (station-keep or steeraway within a given radius) from pre-vetted, water-valid candidates, leaves the voyage plan unchanged, notifies the ROC, and remains immediately overridable. Operationally, we recommend a fast default model (<10 s) with repeated re-evaluation under a safety envelope, escalating to slower high-awareness models when time budget permits.

Limitations and scope. This work is a proof of concept that targets the post-alert interval: we evaluate the fallback maneuver selector that runs after an anomaly alert has been raised. Comprehensive validation of the upstream anomaly alert (including miss/false-alarm behavior in diverse maritime conditions) is an important but separate problem and remains future work beyond the small-n appendix check. In the live run the alert was triggered manually. Our perception and candidate gating are intentionally camera-only and rely on a water mask as a conservative proxy for range-aware obstacle clearance. Hazards outside the camera field of view, occlusions, and degraded visual conditions (e.g., glare, rain/spray, night) are not addressed in this study. The action space is limited to simplified straightline, short-horizon candidates and a single-shot decision without replanning, which can exclude otherwise safer maneuvers. The offline dataset covers one harbor/ODD with 40 scenes and includes AI-enhanced fire/sign scenarios used for early-stage validation, while this enables controlled testing of rare hazards, it may not capture real fire dynamics (e.g., wind-driven smoke) or all sources of sensor noise.

Given the modest number of scenes (N=40), the fire riskrelief subset (n=10), and the limited number of closed-loop runs (n=5), statistical power is limited and some estimates have nontrivial uncertainty. We therefore report 95% confidence intervals throughout and interpret the results as directional proof-ofconcept evidence rather than definitive performance guarantees. Repeated stochastic calls per scene (FB-n) probe decision stability, but do not substitute for additional independent scenarios spanning multiple ODDs and environmental conditions.

Finally, our awareness metric uses an LLM-as-judge and our model evaluations use API-accessed foundation models, so absolute latency and availability may vary across deployments, we therefore emphasize relative comparisons and conservative safe defaults (Sec. 4.2).

Future work. The anomaly→fallback maneuver→override loop provides a path to collect labeled scenes and operator outcomes for fine-tuning and continuous improvement, potentially leading to more domain-adapted VLMs and fallback maneuver selectors. To improve reproducibility and reduce APIand connectivity-related failure modes, future work should include evaluations with open-weight, vision-centric models (e.g., Qwen-VL (Bai et al., 2023)) and smaller locally deployable VLMs (e.g., 7B-30B) that can run on the ROC workstation or onboard. This would enable more predictable latency and availability, and provides a practical path toward domain adaptation (fine-tuning etc.) while retaining the same candidateconstrained interface and human-override guarantees. Next steps include expanding the dataset to include more real-world operational data, performing sensitivity and ablation experiments (e.g., measuring awareness-alignment correlation), integrating a multi-sensor BEV with a type of receding-horizon method, and evaluating non-motion responses (e.g., VHF communication) where appropriate.

We presented a proof-of-concept, camera-first, candidateconstrained VLM fallback maneuver selector that turns semantic scene understanding into short-horizon actions while keeping explicit human authority. Across 40 harbor scenes, fast models retained most of the awareness of slower systems, and the FB-3 selector aligned better with human preference than geometry-only baselines. On the unambiguously dangerous fire hazards, the fallback maneuver selector increased standoff distance, and a live on-water run verified the alert → fallback maneuver → override chain. Together, this supports VLMs as a semantic fallback maneuver selector that fits the IMO MASS Code-style degraded mode fallback maneuver within practical latency budgets. We believe this work can support the transition to one-to-many supervision of maritime autonomy.

Looking ahead, the main challenges are: handling rare, lowsalience cues; broader context than the single camera view; and decisions that evolve over time rather than a single shot. We see the path forward in domain-adapted models and pairing foundation-model semantics with a multi-sensor BEV and receding-horizon control, while using the general anomaly alert → fallback maneuver → override loop to turn override situations into training data for continual improvement.

works out of the box on small-n datasets. We use it only as a detector in a detect→fallback maneuver→override chain, the fallback maneuver stages are described elsewhere in our paper.

Procedure. Experts were given the scenario of being a captain responsible for 10 ferries in a shore control center. When an anomaly was detected on one vessel, they were instructed to monitor and, if needed, take control at the teledrive station. Participants engaged in a structured walkthrough of the interface while using a think-aloud protocol. Moderators provided only neutral prompts when necessary. All sessions were audio-and screen-recorded with internally selected participants.

Analysis. Notes and transcripts were coded thematically. Responses were categorized under situational awareness, interface clarity, workload, and trust.

Protocol script.

(a) Explanation about experiment i. You will take a part of an experiment evaluating human machine interaction and takeover procedure during anomaly alert. The idea behind the system is having multiple autonomous vessels being operative at the same time, where manual assessment and takeover might be needed. (b) Explanation about data collection i. We will take audio record for question answer analysis and video footage of the screen for further analysis of the GUI enhancements. (c) Explanation about equipment i. Joystick, throttle controller, map, compass, (some parts are dummies). Joystick can be used to take over any time during autonomous operation. (d) Training in think-aloud protocol i. Example: I see that the boat is standing still on the left side I can spot a sailboat not far from the boat. I think I will take over by using the joystick now because the boat is to close. 2. Test drive the vessel without anomaly (a) Training in think-aloud protocol i. Move the boat forward ii. Move the boat left iii. Rotate the boat 180 degrees iv. Try some free movements 3. Ask a few questions about the GUI (short) (a) Any comments or questions about the system before we start? 4. Brief about anomaly (a) “Imagine that you are the captain in charge of multiple ferries at the shore control center. All vessels operate autonomously without the need for manual control. However, when an anomaly is detected, the system notifies the operator, and the vessel experiencing the anomaly is automatically displayed in the teledrive station. An anomaly is defined as a situation the autonomy has never encountered before or cannot recognize as familiar. Test drive with anomaly.”

(b) Summarized: 1) You will need to take control of the vessel during an anomaly detection and 2) start bringing it closer to the closest dock. Which means that you first need to assess the situation and then do the correct takeover. 5. Test • Did the GUI told you when anomaly was detected?

• Was any of the information presented in the GUI unclear?

• Did you look at the map?

• Based on the information shown, how did you understand your next steps during the takeover?

• Did you feel you had enough information to take control?

- Cognitive load / stress

• Did the amount of information and the way it was presented stress you, or did it feel manageable?

• What do you think about anomaly detection with explainable AI that explains what happens?

• Would you have used this system as a captain?

• Any comments from your side Appendix D. Formative handover study report Future Status (Level 3 SA). The evaluation of sensory modalities in the graphical user interface of the anomaly detection module (GUI) is based on this 3-level model. This is consistent with known human-factors issues in shore control centers for unmanned or highly automated ships (e.g., information overload, mode confusion, timing/latency effects) and highlights the need for interfaces that externalize system state, intent, and uncertainty (Rutledal, 2024, p. 53); (Wahlström et al., 2015, p. 2). This design challenge can be framed in terms of Level 1 SA, since incoming signals to the operator’s perceptual system that encode the vessel’s state (e.g., through sight, hearing, and touch) are affected, which may have knock-on effects for Level 2 and Level 3 SA. In this context, we developed an anomaly detection and handling module with a GUI intended to support the operator in quickly understanding what the system has detected, what autonomy is doing, and when/where manual takeover is appropriate.

models near a high plateau on Fire and Custom sign. When defining “low awareness” as the bottom quartile of per-call awareness scores, failures concentrate overwhelmingly in the small/low-salience categories: 63.7% of Diver flag calls and 30.4% of MOB calls fall into this low-awareness subset, vs.

📸 Image Gallery