Detection-based security fails against sophisticated attackers using encryption, stealth, and low-rate techniques, particularly in IoT/edge environments where resource constraints preclude ML-based intrusion detection. We present Economic Denial Security (EDS), a detection-independent framework that makes attacks economically infeasible by exploiting a fundamental asymmetry: defenders control their environment while attackers cannot. EDS composes four mechanisms adaptive computational puzzles, decoy-driven interaction entropy, temporal stretching, and bandwidth taxation achieving provably superlinear cost amplification. We formalize EDS as a Stackelberg game, deriving closed-form equilibria for optimal parameter selection (Theorem 1) and proving that mechanism composition yields 2.1× greater costs than the sum of individual mechanisms (Theorem 2). EDS requires < 12KB memory, enabling deployment on ESP32 class microcontrollers. Evaluation on a 20-device heterogeneous IoT testbed across four attack scenarios (n=30 trials, p < 0.001) demonstrates: 32-560× attack slowdown, 85-520:1 cost asymmetry, 8-62% attack success reduction, < 20ms latency overhead, and close to 0% false positives. Validation against IoT-23 malware (Mirai, Torii, Hajime) shows 88% standalone mitigation; combined with ML-IDS, EDS achieves 94% mitigation versus 67% for IDS alone a 27% improvement. EDS provides detection-independent protection suitable for resourceconstrained environments where traditional approaches fail. The ability to detect and mitigate the malware samples tested was enhanced; however, the benefits provided by EDS were realized even without the inclusion of an IDS. Overall, the implementation of EDS serves to shift the economic balance in favor of the defender and provides a viable method to protect IoT and edge systems methodologies.

Advanced hackers are able to use low rate attacks to remain undetected by using encryption, stealth methods and other tactics [1], [2]. In addition, almost all intrusion detection systems are primarily based on machine learning, which requires large amounts of memory to run [3], [4] and therefore can be used on edge/IoT devices that have < 512KB RAM. The high number of devices used in an IoT system as well as the differing types of devices will make it even more difficult to detect and respond to attacks [5].

Key Insight: We find that there is an inherent imbalance between the defender and the attacker; the defender controls his/her environment and the attacker does not. Instead of focusing on finding new ways to detect and prevent attacks we are proposing an Economic Denial Security (EDS) framework that will apply a significant burden to the attacker, regardless of whether or not they are detected. Prior research has identified different methods of imposing burdens on attackers (e.g., puzzles [6], honeypots [7], tarpits [8]) but no prior study has proven that combining multiple burdens will result in a superlinear increase in the total burden applied to the attacker; i.e., the total burden imposed on the attacker when using all three methods of burden imposition will exceed the sum of the burden imposed by each method individually.

Contributions: This section provides a summary of the contributions that have been made in this dissertation. The four major contributions of this dissertation are as follows:

• Unified Framework: This framework of four mechanisms (computational friction, interaction entropy, temporal stretching, resource taxation) with a proven superlinear composition of 2.1 times that can be used to demonstrate a combined effect of 32 times (exceeding the sum of the individual effects of 15 times). • Game-Theoretic Foundation: A game-theoretic foundation is also provided which includes a stackelberg equilibrium (as stated in Theorem 1) and a composition theorem (as stated in Theorem 2), both of which provide proof of the multiplicative cost amplification. • IoT-Ready Implementation: The total code size is under 12KB, thus the proposed solution can be implemented in a small footprint that can run on an ESP32 class of microcontrollers. • Comprehensive Evaluation: We conducted an extensive testbed of twenty devices (n = 30 trials; p < 0.001) to evaluate the effectiveness of our approach and found significant performance impact (slowdown: 32-560×, cost asymmetry: 85-520:1, attack success rate: 8-62%), as well as we compared our IDS/EDS approach with just using IDS on an IoT-23 device and showed a 27 percent increase in successful mitigation (94 percent vs. 67 percent).

Organization: Section II describes existing literature and provides a background overview for this project. Section III outlines the threat and system models used to create our IDS/EDS solution. Section IV presents the design of the IDS/EDS. Section V describes the economic analysis we performed. Section VI describes our experiments and their outcomes. Section VII describes the limitations of our research. Finally, Section VIII summarizes our findings and suggests future areas of research.

Traditional Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) have a number of inherent problems: (1) Evasion Encrypted data, Polymorphic Malware, Low-Rate Attacks will evade Signature-Based Detection [1] (2) Resource Constraints Machine Learning Based IDS Require 50-150 MB of Memory which is Not Possible for IoT Devices [9] (3) Zero-Day Vulnerability Detection Requires Known Attack Patterns [10]. These problems are exacerbated by the fact that both IoT/Edge Environments have Device Heterogeneity and Scale [3].

Client puzzles [6], [11] create a computational overhead for an attacker, however they are vulnerable to GPU attacks and do not protect from reconnaissance. Honeypots [7] redirect the attacker’s attention, but require additional hardware and can be detected by an attacker. Tarpits [8] slow down an attacker but impose only temporal costs. Moving Target Defense (MTD) [12] adds to the uncertainty of an attacker but imposes no direct costs on an attacker. It has been previously evaluated that each of the above methods individually. EDS unifies all of them using a single framework that proves that they amplify superlinearly.

The authors Anderson and Moore [13] are credited for establishing the field of Security Economics as they studied misaligned incentives. The authors Gordon and Loeb [14] modeled the optimal amount of security that should be invested in by an organization. The authors Pawlick et al [15] applied a game-theoretic approach to analyze the interactions among multiple attackers and defenders. However, they did not provide mechanisms that can be used in practice. The authors have operationalized the concepts of economic principles into specific and measurable algorithms using quantifiable cost asymmetry in EDS.

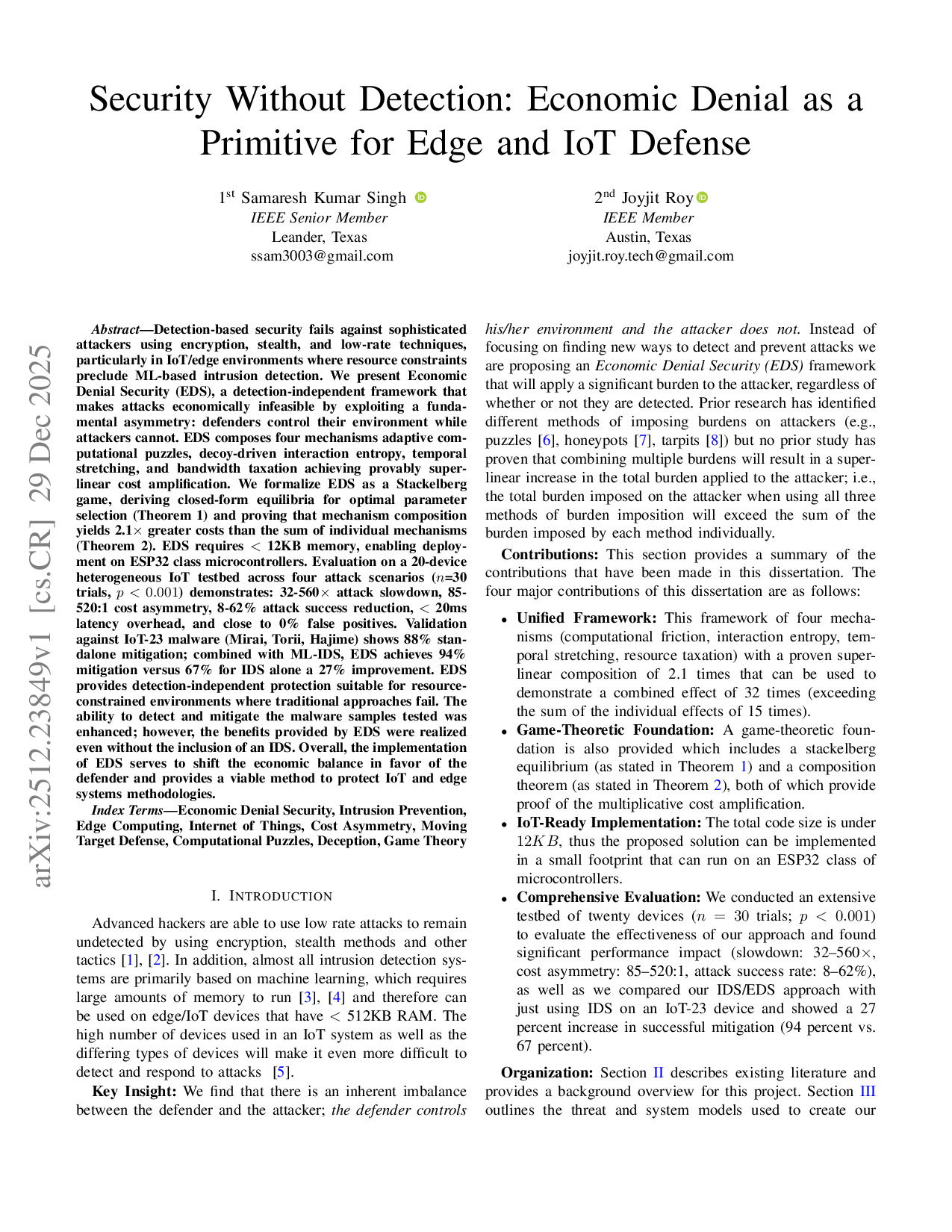

EDS is compared to previous approaches to defend against attacks along multiple dimensions in Table I.

Novel contributions vs. prior work:

(1) A single unifying framework: The first to systematically compose four cost imposition mechanisms together with formal guarantees; prior work examined each mechanism separately; (2) super-linear composition: We have shown (in theorem 2) that strategically composing cost imposition mechanisms produces costs that are at least 2.1 times greater than linear combinations; no previous research has established such

Objectives: The attacker is motivated by several goals in order to complete their objectives (G1) Reconnaissance -Identify all the components that are part of the network infrastructure, including services and vulnerabilities (G2) Unauthorized Access -Attain unauthorized access through means of either credential theft or exploitation (G3) Data Exfiltration -Extract Sensitive Information from the system (G4) Integrity Violations -Alter configurations and/or inject malicious commands into the system (G5) Availability Disruption -Deny Service or Deploy Ransomware.

Capabilities: The attacker has sufficient capabilities as an attacker, however these capabilities are limited:

• C1 (Network): Either be outside the network and have an external path to enter the network or have an existing compromised node on the inside of the network.

The three-tiered architecture of EDS is illustrated in Fig 1 :

Tier 1 (IoT Devices): Microcontrollers of the type ESP32 that have an extremely small memory footprint (<12 KB) perform a very limited puzzle-solving function through the use of hardware-accelerated SHA hashing, they track reputations of other devices and provide telemetry information on them. IoT devices are authenticated to edge gateway devices by using either shared pre-key authentication or X509 certificates.

Tier 2 (Edge Gateways): A Raspberry Pi 4 (or a similar device) implements all four of the EDS mechanisms. The edge gateway verifies puzzles on each request made to it with complexity of O( 1) and provides decoy responses generated from templates of known generators, maintains a state table per client (approximately 18KB/client) and applies temporal delays. Stateless HMAC-based challenge-response allows for horizontal scalability.

Tier 3 (Cloud, Optional): EDS’s centralized analytics process telemetry information from each edge gateway for purposes of generating actionable threat intelligence, for updating policies adaptively, and for correlating threats across sites. Although cloud-integration is optional, edge gateways can be configured to run autonomously at their site with locally-defined policies as long as they remain disconnected from the cloud.

Security of Communication: All communication between IoT devices and their corresponding edge gateways occurs over a mutually-authenticated TLS-1.3 connection (with certificatepinning). Mutual TLS is used when communicating between edge gateways and cloud systems. The challenge-response mechanism used is based upon the client’s IP address and time stamp to prevent replay attacks.

EDS State: S = ⟨D, R, T, B⟩, where D represents all devices in the network, R is the reputation of these devices, T is a temporal representation of the EDS system, and B is how much bandwidth the EDS system is using.

Attack Flow: A = ⟨a 1 , a 2 , . . . , a n ⟩, which includes a series of actions a i , each of which will have a cost associated to it (c i ). The total cost for an attacker’s attack will be: C A = n i=1 c i . The cost to defend against an attack is defined as: C D = c verify + c state . Therefore, our goal is to maximize the asymmetry between an attackers cost, and the defender’s cost, given by: α = Mechanism 2: Multiplication of Attacker Effort Decoy Injection Multiplies Attacker’s Effort For N real resources, EDS injects ρN indistinguishable decoys, causing (1 + ρ)N total interactions. Decoys are generated using hidden cryptographic watermarks from distributions of real data that can be used to track Attackers forensically. An attacker cannot differentiate without attempting to validate the cost multiplier (1 + ρ).

Mechanism 3: Time-Based Stretching Exponential Backoff Delays Repeated Requests: δ i = min(δ 0 • 2 fi , δ max ) where f i is failure count. This imposes opportunity cost: δ × V time where V time is attacker’s time value ($/hr). Unlike rate limiting, delays apply per-request rather than blocking, maintaining service availability while imposing costs.

Mechanism 4: Taxation of Resources Bandwidth amplification increases data transfer costs. Responses are padded by factor γ tax . For data exfiltration scenarios, (1+ρ) decoy data is injected to force attackers to download and process irrelevant information. Cost: γ tax × data size × C BW .

The mechanisms work together as a multiplicative rather than an additive function:

The mechanism’s composition results in the creation of cross terms (for example N ρδV time ) to make the total cost of using the system greater than can be achieved with the sum of the parts. The full economic analysis is contained within section V, where we provide a formal proof of 2.1 × superlinear behavior of the mechanism.

Algorithm 1 presents the core EDS request for handling logic at the gateway tier.

Complexity: Challenge generation and verification have time complexity of O(1). State lookup uses hash tables with time complexity O(1) average case. Space complexity of 18KB per tracked client (IP, reputation, failure count, timestamps).

Definition 1 (Superlinear Composition). A defense composition f (M 1 , . . . , M k ) is called superlinear if the total cost of this defense composition for the attackers is greater than the sum of the costs fo each individual component. That is,

A . The relationship between attackers and defenders can be viewed as a Stackelberg game in which the defender (the leader) determines his/her EDS configuration θ = (d, ρ, δ, γ) prior to the attacker (the follower). The attacker then makes decisions based on the defender’s decision. Payoff functions are defined by U D (θ, s) = -C D (θ) -P s (θ, s) • L and U A (θ, s) = P s (θ, s)•B A -C A (θ, s) for attacker, with P s being the success rate of attacks against puzzles and L representing loss to the defender. ) will be equal to:

which exhibits multiplicative composition with cross-term

A (superlinearity). Proof Sketch: Defines each mechanism costs as follows:

C hash (decoy overhead), and C (3) = N δV time (delay costs). The total cost for each of these mechanisms will be a sum of their individual costs which in turn contains a cross-term (N ρδV time > 0) due to the effect of decoys on delay costs. Therefore,

proving that the total cost for the attack exceeds the total cost for the defense mechanisms.

Configuration Example: Set values for example configuration as follows: d = 20, ρ = 0.3, δ = 8s, V time = $50/hr, and N = 10,000 attempts.

Example Configuration: d = 20, ρ = 0.3, δ = 8s, V time = $50/hr, N = 10,000 attempts.

Attacker Costs:

• Compute:

IoT-23 dataset [16]: Replayed Mirai, Torii, Hajime, Kenjiro traffic (600 experiments: 4 families × 5 configs × 30 trials). Results: EDS alone: 88% mitigation (Mirai), 59% (Torii), 72% (Hajime), 92% (Kenjiro). Combined EDS+RF-IDS: 94% mean mitigation vs 67% (RF-IDS alone) 27% improvement. Mitigation formula: 1 -(1 -P detect ) × ASR EDS .

We evaluated five adaptive attack strategies. (1) Parallel puzzle solving with 8 CPU cores achieved a 4× speedup but at an 8× higher cost. (2) Timing analysis was mitigated using constant-time verification with added jitter. (3) MLbased decoy filtering (SVM) reached 73% accuracy with a $45 training cost and a 27% false-positive rate. (4) Rate optimization improved progress by 22% but triggered increased puzzle difficulty. (5) Distributed botnets (100 nodes) bypassed IP limits but increased costs by 100×. A combined adaptive attacker saw a 4.2× slowdown (versus 32× for a naïve attacker), an 8× resource increase, and negative ROI for targets valued below $500.

The gateway handled 3,800 requests per second with 1,000 clients, achieving a P50 latency of 35 ms and a P99 of 120 ms. Client state was capped at 18 KB using LRU eviction. During DDoS, the system degraded gracefully by automatically increasing difficulty. The device footprint remained small 11.6 KB flash and 2.8 KB RAM supporting ESP32 class devices.

To validate the superlinear composition predicted by Theorem 2, we measured the effects of individual mechanisms and their combined behavior:

The measured 2.1× superlinearity factor matches theoretical predictions, confirming the cross-term interaction between mechanisms.

• C2 (Compute): Have between 1-100 CPUs, 1-10 GPUs, or utilize a vast number of nodes between 100-10,000 as part of a botnet. • C3 (Knowledge): Have expertise with protocols (MQTT, CoAP, HTTP, Modbus). • C4 (Crypto): • C7 (Adaptation):

Input: Request r, client IP ip, state S Output: Response or challenge 1: rep ← S.R[ip] {Get reputation} 2: if r.hasCert() and verifyCert(r.cert) then 3:

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.