In safety-critical domains, reinforcement learning (RL) agents must often satisfy strict, zero-cost safety constraints while accomplishing tasks. Existing model-free methods frequently either fail to achieve near-zero safety violations or become overly conservative. We introduce Safety-Biased Trust Region Policy Optimisation (SB-TRPO), a principled algorithm for hard-constrained RL that dynamically balances cost reduction with reward improvement. At each step, SB-TRPO updates via a dynamic convex combination of the reward and cost natural policy gradients, ensuring a fixed fraction of optimal cost reduction while using remaining update capacity for reward improvement. Our method comes with formal guarantees of local progress on safety, while still improving reward whenever gradients are suitably aligned. Experiments on standard and challenging Safety Gymnasium tasks demonstrate that SB-TRPO consistently achieves the best balance of safety and task performance in the hard-constrained regime.

Reinforcement learning (RL) has achieved remarkable success in domains ranging from games to robotics, largely by optimising long-term cumulative rewards through trial-anderror interaction with an environment. However, in many real-world applications unconstrained reward maximisation is insufficient: agents must also satisfy safety or operational constraints. This problem is naturally formulated as a Constrained Markov Decision Process (CMDP, see (Altman, 2021)), which includes cost signals representing undesirable or unsafe outcomes in addition to rewards. Within this framework, safe RL has been studied under a wide range of objectives and algorithmic paradigms (see (Wachi et al., 2024;Gu et al., 2024b) for surveys).

Most existing work formulates safe RL as maximising discounted expected reward subject to the discounted expected cost remaining below a positive threshold (e.g., (Ray et al., 2019;Achiam et al., 2017;Yang et al., 2022)). This formulation is appropriate when costs represent soft constraints, such as resource consumption or wear-and-tear -for example, an autonomous drone that must complete its mission before its battery is depleted. In such cases, incurring costs can be acceptable provided their expected frequency remains low.

However, in many safety-critical domains any non-zero cost corresponds to catastrophic failure. Robots operating near humans cannot afford collisions, and autonomous vehicles must never violate speed or distance limits in safety-critical zones. In these settings, expected-cost formulations with a positive cost threshold are misaligned with the true safety objective: policies must avoid safety violations entirely, rather than merely keeping them small in expectation. This motivates a hard-constrained formulation, in which safety violations are unacceptable and policies must achieve zero cost with high reliability.

Limitations of Existing Approaches. Despite substantial progress in constrained RL, existing model-free methods struggle in hard-safety regimes. Lagrangian approaches, such as TRPO-and PPO-Lagrangian (Ray et al., 2019), rely on penalty multipliers to trade off reward and cost. In practice, this often leads to either unsafe policies (when penalties are small) or overly conservative behaviour with poor task completion (when penalties are large), with performance highly sensitive to hyperparameter choices. Moreover, once penalties increase, recovery from conservative regimes is difficult, particularly under sparse or binary cost signals.

Projection-based methods such as Constrained Policy Optimization (CPO) (Achiam et al., 2017) explicitly attempt to maintain feasibility at each update. While appealing in principle, this often results in severely restricted update directions or vanishing step sizes in challenging environments, leading to slow learning and low reward. More recent methods, including CRPO (Xu et al., 2021) and PCRPO (Gu et al., 2024a), alternate between cost and reward optimisation or combine gradients via simple heuristics. When safety violations are frequent or hard to eliminate, these approaches tend to prioritise cost reduction almost exclusively, again resulting in poor task performance.

Overall, existing methods are primarily designed for soft constraints and degrade qualitatively when applied to hardsafety settings: they either violate safety constraints or achieve safety at the cost of extremely low task performance. This gap motivates the need for algorithms that are explicitly designed for hard-constrained reinforcement learning and can make reliable progress toward safety while still enabling meaningful reward optimisation.

Our Approach. We propose Safety-Biased Trust Region Policy Optimisation (SB-TRPO), a principled algorithm for reinforcement learning with hard safety constraints, which dynamically balances progress towards safety and task performance. Conceptually, SB-TRPO combines the cost and reward natural policy gradients in a dynamically computed convex combination, enforcing a fixed fraction of optimal cost reduction while directing the remaining update capacity towards reward improvement. Unlike CPO and related methods, SB-TRPO does not switch into separate feasibilityrecovery phases, avoiding over-conservatism and producing smoother learning dynamics. This ensures reliable progress on safety without unnecessarily sacrificing task performance and generalises CPO, which is recovered when maximal safety progress is enforced.

Contributions. We summarise our main contributions:

• We present a new perspective on hard-constrained policy optimisation, introducing a principled trust-region method that casts updates as dynamically controlled trade-offs between safety and reward improvement. • We underpin this method with theoretical guarantees, showing that every update yields a local reduction of safety violations while still ensuring reward improvements whenever the gradients are suitably aligned. • We empirically evaluate SB-TRPO on a suite of Safety Gymnasium tasks, demonstrating that it consistently achieves meaningful task completion with high safety, outperforming state-of-the-art safe RL baselines.

Finally, we contend that hard-constrained regimes are rarely addressed explicitly in model-free safe reinforcement learning, despite being the appropriate formulation for genuinely safety-critical applications. By specifically targeting this setting, our work seeks to draw the community’s attention to a practically important yet largely neglected problem class.

Primal-Dual Methods. Primal-dual methods for constrained RL solve a minimax problem, maximising the penalised reward with respect to the policy while minimising it with respect to the Lagrange multiplier to enforce cost constraints. RCPO (Tessler et al., 2018) is an early twotimescale scheme using vanilla policy gradient and slow multiplier updates. Under additional assumptions (e.g., that all local optima are feasible), it converges to a locally optimal feasible policy. Likewise, TRPO-Lagrangian and PPO-Lagrangian (Ray et al., 2019) use trust-region or clippedsurrogate updates for the primal policy parameters. PID Lagrangian methods (Stooke et al., 2020) augment the standard Lagrangian update with additional terms, reducing oscillations when overshooting the safety target is possible. Similarly, APPO (Dai et al., 2023), which is based on PPO, augments the Lagrangian of the constrained problem with a quadratic deviation term to dampen cost oscillations.

Trust-Region and Projection-Based Methods. Constrained Policy Optimization (CPO) (Achiam et al., 2017) enforces a local approximation of the CMDP constraints within a trust region and performs pure cost-gradient steps when constraints are violated, aiming to always keep policy updates within the feasible region. FOCOPS (Zhang et al., 2020) is a first-order method solving almost the same abstract problem for policy updates in the nonparameterised policy space and then projects it back to the parameterised policy. P3O (Zhang et al., 2022) is a PPO-based constrained RL method motivated by CPO. It uses a Lagrange multiplier, increasing linearly to a fixed upper bound, and clipped surrogate updates to balance reward improvement with constraint satisfaction. Constrained Update Projection (CUP) (Yang et al., 2022), in contrast to CPO, formulates surrogate reward and cost objectives using generalised performance bounds and Generalised Advantage Estimators (GAE), and projects each policy gradient update into the feasible set defined by these surrogates, allowing updates to jointly respect reward and cost approximations. Milosevic et al. (2024) propose C-TRPO, which reshapes the geometry of the policy space by adding a barrier term to the KL divergence so that trust regions contain only safe policies (see Section D.1 for an extended discussion). However, similar to CPO, C-TRPO switches to pure cost-gradient updates when the policy becomes infeasible, entering a dedicated recovery phase. In follow-up work, Milosevic et al. (2025) introduced C3PO, which resembles P3O and relaxes hard constraints using a clipped penalty on constraint violations.

Reward-Cost Switching. CRPO (Xu et al., 2021) is a constrained RL method that alternates between reward maximistion and cost minimistion depending on whether the current cost estimate indicates the policy is infeasible. Motivated by CRPO’s tendency to oscillate between purely reward-and cost-focused updates, (Gu et al., 2024a) propose PCRPO, which mitigates conflicts between reward and safety gradients using a softer switching mechanism and ideas from gradient manipulation (Yu et al., 2020;Liu et al., 2021). When both objectives are optimised, the gra-dients are averaged, and if their angle exceeds 90 • , each is projected onto the normal plane of the other.

Model-Based and Shielding Approaches. Shielding methods (Alshiekh et al., 2018;Belardinelli et al., 2025;Jansen et al., 2020) intervene when a policy proposes unsafe actions, e.g. via lookahead or model predictive control, but typically require accurate dynamic models and can be costly. (Yu et al., 2022) train an auxiliary policy to edit unsafe actions, balancing reward against the extent of editing. Other typically model-based methods leverage control theory (Perkins & Barto, 2002;Berkenkamp et al., 2017;Chow et al., 2018;Wang et al., 2023).

We consider a constrained Markov Decision Process (CMDP) defined by the tuple (S, A, P, r, c, γ), where S and A are the (potentially continuous) state and action spaces, P (s ′ | s, a) is the transition kernel, r : S → R is the reward function, c : S → R ≥0 is a cost function representing unsafe events, and γ ∈ [0, 1) is the discount factor. A stochastic policy π(a | s) induces a distribution over trajectories τ = (s 0 , a 0 , s 1 , a 1 , . . . ) together with P .

In safety-critical domains, the objective is to maximise discounted reward while ensuring that unsafe states are never visited, i.e. c(s t ) = 0 for all times t almost surely:

Directly enforcing this zero-probability constraint over an infinite horizon is intractable in general, especially under stochastic dynamics or continuous state/action spaces. Even a single unsafe step violates the constraint, and computing the probability of an unsafe event across the infinite time horizon is typically infeasible.

To make the problem tractable, we re-formulate it as an expected discounted cost constraint with cost threshold 0:

Since costs are non-negative, any policy feasible under (Problem 2) is also feasible for the original (Problem 1).

Setting the standard CMDP expected discounted cost threshold to 0, this re-formulation enables the use of off-the-shelf constrained policy optimisation techniques whilst in principle still enforcing strictly safe behaviour.

Discussion. Most prior work in Safe RL focuses on positive cost thresholds (e.g. 25 in Safety Gymnasium (Ji et al., 2023)). However, in genuinely safety-critical applications there is no meaningful notion of an “acceptable” amount of catastrophic failure. Positive thresholds conflate the problem specification with an algorithmic hyperparameter, making training brittle, environment-dependent, and misaligned with true safety objectives.

Our zero-cost formulation instead directly encodes the intrinsic hard-safety requirement. Conceptually, it provides a clear, principled target for algorithm design: policies should strictly avoid unsafe states, and algorithm design can focus on achieving this reliably rather than tuning a threshold that only approximates safety.

We first derive the idealised SB-TRPO update, before presenting a practical approximation together with its performance-improvement guarantees. Finally, we summarise the overall method in a complete algorithmic description.

In the setting of hard (zero-cost) constraints, the idealised CPO (Achiam et al., 2017) update seeks a feasibilitypreserving improvement of the reward within the KL trust region:

This update only considers policies that remain feasible. When no such policy exists within the trust region, CPO (and related methods such as C-TRPO) switches to a recovery step:

Empirically, the (Recovery) step does drive the cost down, but often at the expense of extreme conservatism and with no regard for task reward (by design). Once a zero-cost policy has been found, CPO switches back to the feasibilitypreserving update (CPO). Starting from these overly cautious policies, any improvement in task reward typically requires temporarily increasing the cost. This is ruled out by the constraint in (CPO). As a consequence, CPO gets “stuck” near low-cost but task-ineffective policies (cf. Section 5), never escaping overly conservative regions of the policy space.

To address this limitation, we introduce a more general update rule that seeks high reward while requiring only a controlled reduction of the cost by at least ϵ ≥ 0:

Note that CPO corresponds to the special case ϵ = J c (π old ), which forces feasibility at every iteration. In contrast, this formulation does not require the intermediate policies to remain feasible (see Section 6 for an extended discussion).

To ensure that (Update 1) always admits at least one solution, and to avoid the need for an explicit recovery step such as (Recovery), we choose ϵ to be a fixed fraction of the best achievable cost improvement inside the trust region. Formally, for a safety bias β ∈ (0, 1], we define

Crucially, this guarantees feasibility of (Update 1) as well as ϵ ≥ 0. The parameter β controls how aggressively the algorithm insists on cost reduction at each step.

β = 1 Recovers CPO. Setting β = 1 forces each update to pursue maximal cost improvement within the trust region, reducing the cost constraint in (Update 1) to J c (π) ≤ c * π old . Note that c * π old = 0 iff (CPO) is feasible. Thus, (Update 1) for β = 1 elegantly captures both the recovery and standard feasible phases of CPO.

Intuition for Using a Safety Bias β < 1. Choosing β < 1 intentionally relaxes this requirement: the policy must still reduce cost, but only by a fraction of the optimal improvement. This slack provides room for reward-directed updates even when the maximally cost-reducing step would be overly restrictive. In practice, β < 1 prevents the algorithm from getting trapped in low-reward regions and enables steady progress towards both low cost and high reward.

The theoretical properties of the idealised (Update 1) can be summarised as follows:

Lemma 4.1. Let π 0 , π 1 , . . . be the sequence of policies generated by the idealised (Update 1). Then 1. The cost is monotonically decreasing:

the modified constrained problem:

NB Rewards do not necessarily monotonically increase, and J c (π k+1 ) = J c (π k ) does not preclude future cost reductions since the trust regions continue to evolve as long as rewards improve.

Since direct evaluation of J r (π) and J c (π) for arbitrary π is infeasible, we employ the standard surrogate objectives (Schulman et al., 2015) with respect to a reference policy π old . For reward (and analogously for cost), we define

By the Policy Improvement Bound (Schulman et al., 2015),

In particular, J r (π old ) = L r,π old (π old ), and similar bounds hold for J c . These observations justify approximating the idealised (Update 1) by its surrogate:

As in TRPO, the KL constraint guarantees that the surrogates remain close to the true policy performances.

Second-Order Approximation. Henceforth, we assume differentiably parameterised policies π θ and overload notation, e.g. J c (θ) for J c (π θ ). Linearising the reward and cost objectives around the current parameters θ old and approximating the KL divergence by a quadratic form with the Fisher information matrix yields the quadratic program

where g r := ∇L r,θ old (θ old ), g c := ∇L c,θ old (θ old ) and F denotes the Fisher information matrix.1 To choose ϵ and approximate Equation (1), we analogously approximate the trust-region step that maximally decreases the cost surrogate

and set ϵ := -β • ⟨g c , ∆ c ⟩ with safety-bias β ∈ (0, 1]. This guarantees feasibility of (Update 3). The new parameters are then updated via θ = θ old + ∆ * , with ∆ * the solution of (Update 3), analogous to the TRPO step but enforcing an explicit local cost reduction.

Approximate Solution via Cost-Biased Convex Combination. Solving (Update 3) analytically requires computing the natural gradients F -1 g r and F -1 g c and their coefficients (cf. Lemma B.4 in Section B.2), which is often numerically fragile for large or ill-conditioned F . Instead, we follow TRPO and compute the KL-constrained reward and cost steps separately using the conjugate gradient method (Hestenes et al., 1952):

with ∆ c given by Equation ( 2). Both steps satisfy the same KL constraint, and thus any convex combination

2). We therefore choose the largest reward-improving combination which also satisfies ⟨g c , ∆⟩ ≤ -ϵ (see Figure 1 for a visualisation and Lemma B.3):

(4)

This approximation of (Update 3) ensures an approximate cost decreases at each update:

Likewise, if the reward gradient is non-zero and its angle with ∆ c does not exceed 90 • , an increase in reward is guaranteed. Formally, sufficiently small steps along ∆ are required for the local gradient approximations to hold: Theorem 4.2 (Performance Improvement). There exists

This result complements Lemma 4.1 with guarantees for the gradient-based approximate solution of (Update 1). Unlike CPO and related methods such as C-TRPO (Milosevic et al., 2024), which have a separate feasibility recovery phase, our update can guarantee reward improvement for all steps in which the angle between cost and reward gradients does not exceed 90 • . Once the cost gradient is near zero (g c ≈ 0), updates focus on reward improvement (see also Figure 2). Overall, this scheme dynamically balances cost and reward objectives, naturally stabilising learning. Algorithm 1 Safety-Biased Trust Region Policy Optimisation (SB-TRPO)

training epochs N ∈ N 1: initialise θ 2: κ ← 10 -8 {small constant to avoid division by 0} 3: for N epochs do g r , g c ← policy gradient estimate of ∇L r,π θ (π θ ) and ∇L c,π θ (π θ ) using D 6:

∆ r , ∆ c ← calculated via the conjugate gradient algorithm to optimise Equations ( 2) and (3)

η ← 1 {line search for constraint satisfaction} 10:

Our practical algorithm, implementing the ideas of the preceding subsections, is given in Algorithm 1. We now highlight the key additions.

Line Search. In practice, we follow standard TRPO procedures by performing a line search along the cost-biased convex combination ∆: the KL constraint is enforced empirically to ensure that the surrogate approximations of J r and J c remain accurate; and the empirical reduction in the surrogate cost loss is checked to operationalise the cost decrease guarantee of Theorem 4.2, scaling the step if necessary.

Gradient Estimation. The gradients of the surrogate objective g r = ∇L r,π old (π old ) (analogously for cost) coincide with ∇J r (π old ), which is Monte Carlo estimated using the policy gradient theorem. The Fisher information matrix F is similarly estimated from trajectories.

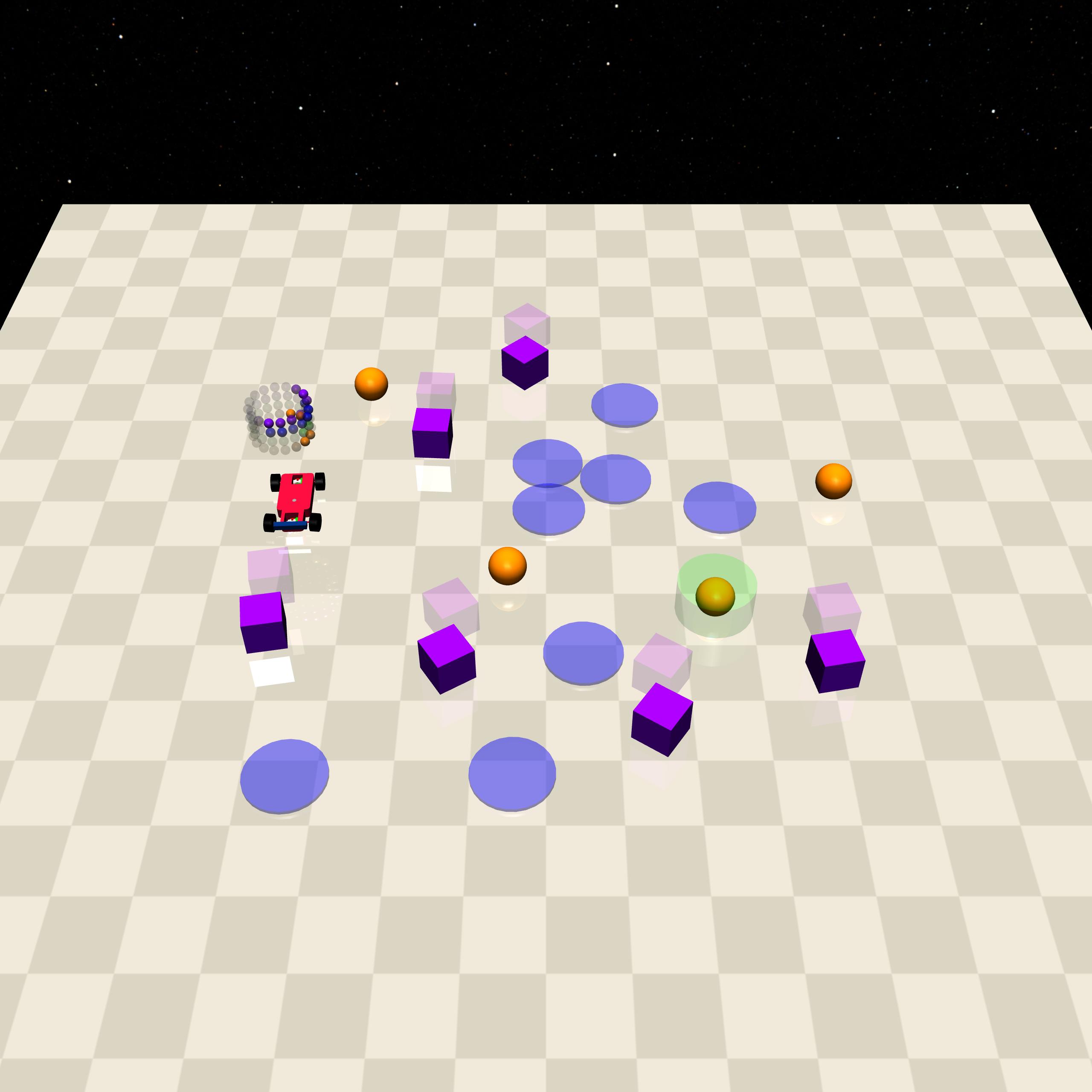

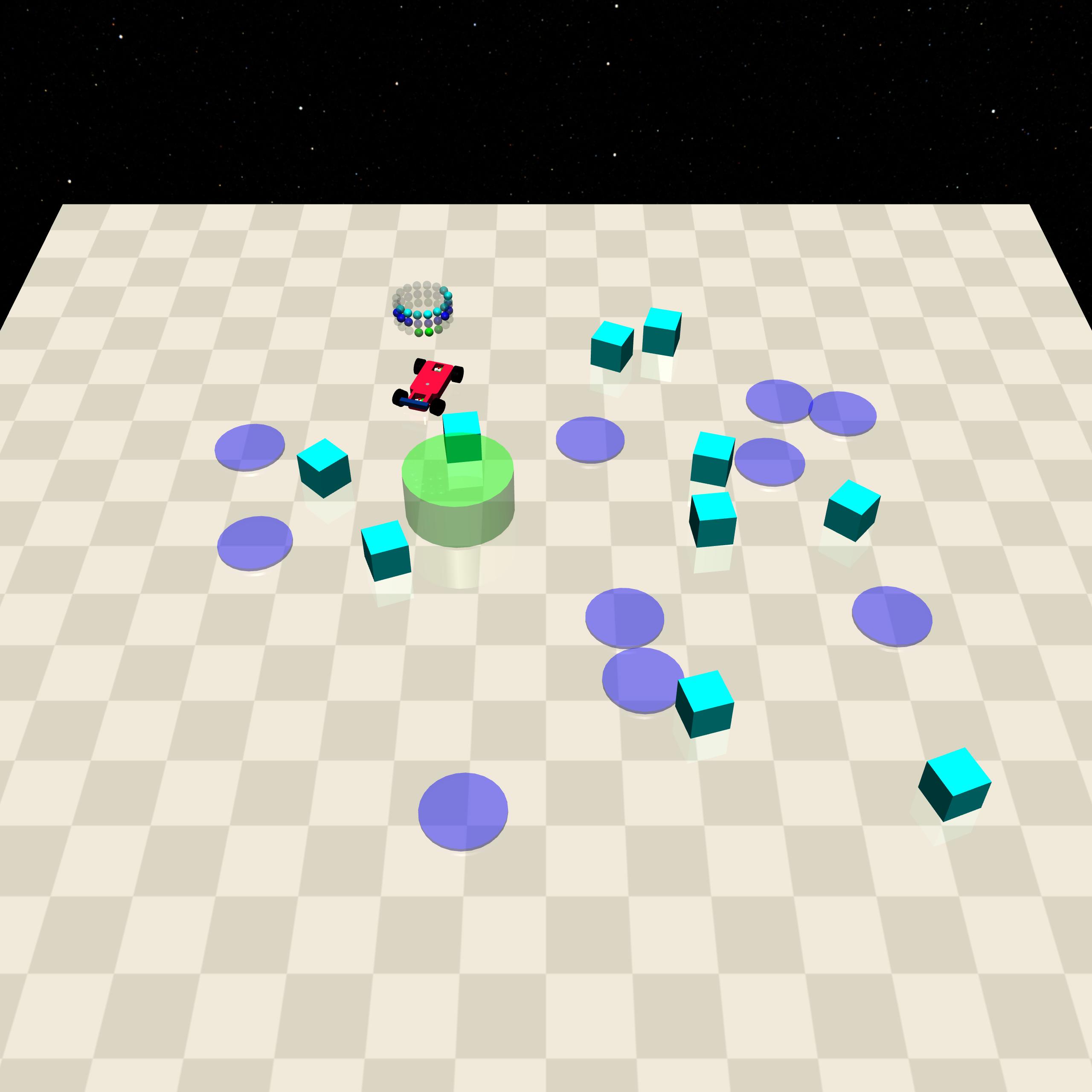

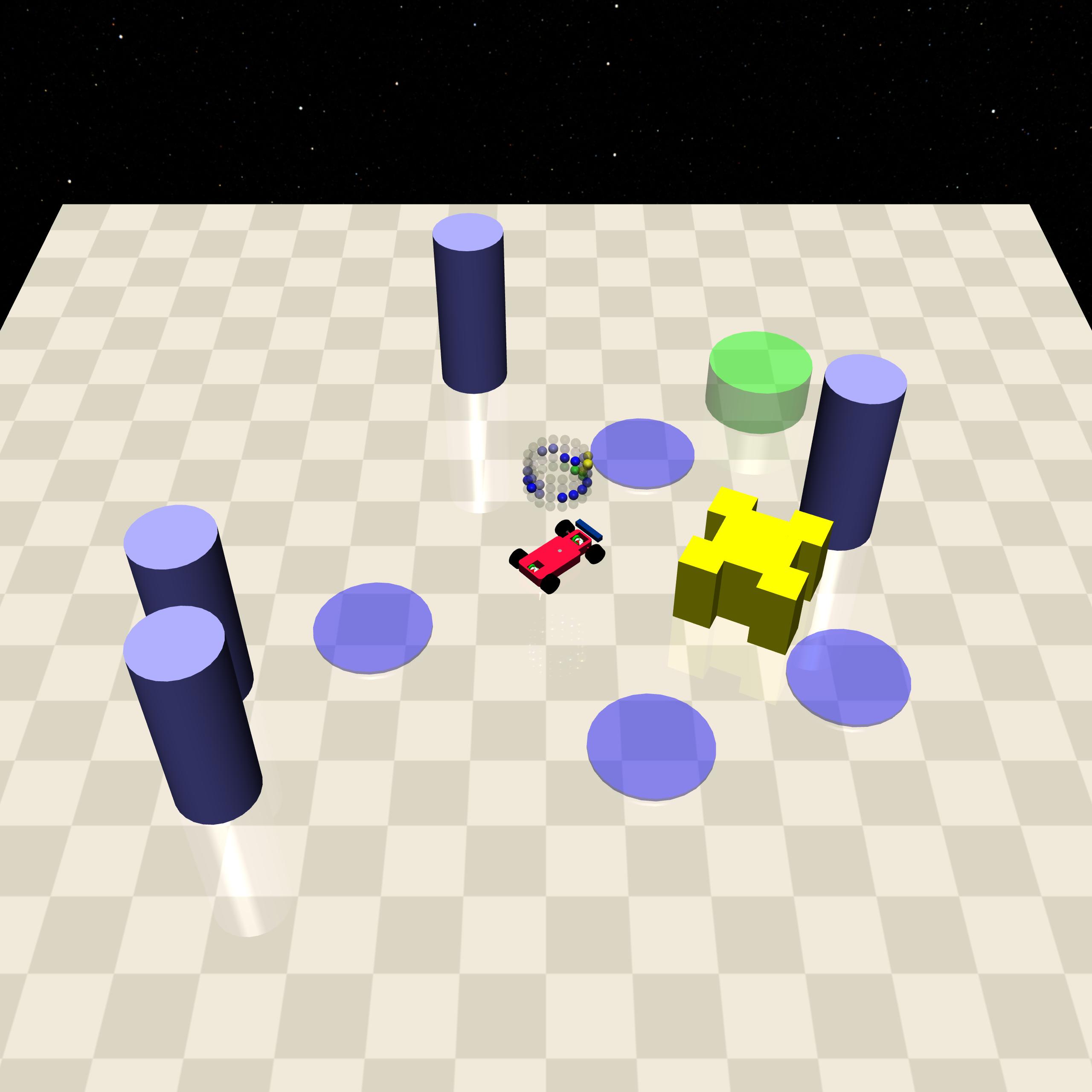

Benchmarks. Safety Gymnasium provides a broad suite of environments for benchmarking safe RL algorithms. Originally introduced by OpenAI (Ray et al., 2019), it has since been maintained and extended by (Ji et al., 2023), who also developed SafePO, a library of safe RL algorithms. 2We focus on two classes of environments: Safe Navigation and Safe Velocity. In Safe Navigation, a robot equipped with LIDAR sensors must complete tasks while avoiding unsafe hazards scattered throughout the environment. We use the Point and Car robots on four tasks -Push, Button, Circle, and Goal -at level 2, which is most challenging due to the greatest number of hazards. In contrast, Safe Velocity environments test adherence to velocity limits rather than obstacle avoidance, and we use the Hopper and Swimmer robots adapted from the MuJoCo locomotion suite (Todorov et al., 2012). The state spaces are up to 88-dimensional; see Section C.1.1 for more details and visualisations.

Safety Gymnasium uses reward shaping to provide the agent with auxiliary guidance signals that facilitate more efficient policy optimisation. In the Goal tasks of Safe Navigation environments, for example, the agent receives dense rewards based on its movement relative to the goal, supplementing the sparse task completion reward, so that the cumulative reward can be negative if the agent moves significantly away from the goal. A cost is also computed to quantify constraint violations, with scales that are task dependent. In our selected tasks, these violations include contact with hazards, displacement of hazards, and leaving safe regions in Safe Navigation, and exceeding velocity limits in Safe Velocity.

Implementation Details. Following the default setup in SafePO, we use a homoscedastic Gaussian policy with stateindependent variance, the mean of which is parameterised by a feedforward network with two hidden layers of 64 units.

Besides, we use the default SafePO settings for existing hyperparameter (cf. Section C.1.2), and the same safetybias β = 0.75 across all tasks (see also Section 5.4 for an ablation study).

In our implementation of SB-TRPO, we eschew critics both to reduce computational cost and to avoid potential harm from inevitable inaccuracies in critic estimates (see Section 5.4). Instead, we rely on Monte Carlo estimates, which provide a practical and sufficiently accurate means of enforcing constraints while maximising reward. By contrast, all baseline methods retain their standard critic-based advantage estimation, as this is considered integral.

Training Details. We train the policies for 2 × 10 7 time steps (103 epochs), running 2 × 10 4 steps per epoch with 20 vectorised environments per seed. All results are reported as averages over 5 seeded parameter initialisations, with standard deviations indicating variability across seeds. Training is performed on a server with an NVIDIA H200 GPU.

Metrics. We compare our performance with the baselines using the standard metrics of rewards and costs, averaged over the past 50 episodes during training. End-of-training values provide a quantitative comparison, while full training curves reveal the asymptotic behaviour of reward and cost as training approaches the budgeted limit.

To capture safety and task performance under hard constraints (as formalised in (Problem 1)), we introduce two additional metrics: safety probability is the fraction of episodes completed without any safety violation, i.e. with zero cost; safe reward is the average return over all episodes, with returns from episodes with any safety violation set to 0:

where R i and C i are the total return and cost of episode i.

The results are reported in Table 1. Our method consistently achieves the best performance in safe reward (among methods with at least 50% safety probability) or safety probability (among methods with positive safe reward), demonstrating its ability to attain both high safety and meaningful task performance. When another method attains a higher safe reward, it typically comes at the expense of a substantial reduction in safety; conversely, methods with higher safety probabilities generally achieve significantly lower safe reward. These trends also manifest for raw rewards and costs.

On the other hand, PPO-Lagrangian often collapses to poor reward, poor safety, or both. Baselines such as TRPO-Lagrangian, CPO or C-TRPO can achieve better safety on some harder tasks (e.g. Point Button), but their rewards are very low -mostly negative -yielding minimal task completion and still falling far short of almost-sure safety. CUP and FOCOPS generally have larger constraint violations.

Beyond final performance, our approach also exhibits robustness in practice: temporary increases in cost are typically corrected quickly whilst improving rewards overall (see Figure 2). Moreover, longer training can continue to improve both reward and feasibility for our method, while the baselines plateau (cf. Figures 6 and7 in Section C.2).

Finally, by eschewing critics, we beat baselines by at least a factor of 10 in computational cost per epoch (see Table 5 in Section C.2).

In summary, our approach is the only one to consistently achieve the best practical balance of safety and meaningful task completion.

To further understand why SB-TRPO avoids the overconservatism of similar methods, we analyse the angles between policy updates and reward/cost gradients (Figures 4 and9). CPO and C-TRPO updates are largely at best orthogonal to the reward gradient (angles around or above 90 • ), indicating that these methods spend much of their time in the recovery phase. In contrast, SB-TRPO updates lie below 90 • , mostly around 60 • -70 • for Car Circle, confirming the performance improvement guarantee of Theorem 4.2 empirically. At the same time, angles relative to the cost gradient can be larger for SB-TRPO than for CPO/C-TRPO but well below 75 • , reflecting a measured approach to feasibility that balances safety with meaningful task progress.

We ablate key design choices to assess their impact on performance.

Safety Bias β. We evaluate the effect of the safety bias β over β ∈ [0.6, 0.9] on Point Button and Car Goal. Figure 3 shows that varying β shifts SB-TRPO policies along a nearly linear reward-safety probability Pareto frontier: higher values emphasise safety at the expense of reward, while lower values trade off some safety for greater reward. By contrast, the baselines typically underperform relative to this frontier (or achieve negative reward). This demonstrates that SB-TRPO is not overly sensitive to the choice of β, with β = 0.75 achieving excellent results throughout (see Table 1).

Eschewing Critics. To justify our design choice of omitting critics (see Section 5.1), we ablate the effect of adding a critic to SB-TRPO on Car Goal and Point Button (Table 2 and Figure 10). Adding a critic accelerates reward learn- ing but also increases incurred cost, exposing a trade-off between reward optimisation and safety under sparse, binary cost signals. In this regime, learning is dominated by relatively accurate reward critic information, whereas cost critics provide weak or delayed feedback for rare unsafe events, biasing updates towards riskier behaviour. We therefore omit critics in our main implementation, yielding more stable policies that better satisfy safety constraints while also substantially reducing computational cost (see Table 5).

For the most closely related baselines, CPO and C-TRPO, removing critics has no clear effect (Tables 6 and7).

Our empirical results show that framing policy updates as (Update 3)-dynamically balancing progress towards safety and task performance-prevents collapse into trivially safe but task-ineffective regions in the face of strict safety con-straints. Unlike CPO and related methods such as C-TRPO, which enforce feasibility at each step and switch to purely cost-driven recovery when constraints are violated with no guarantees for reward improvement, SB-TRPO has no separate recovery phase. This results in smoother learning dynamics and meaningful task progress throughout learning. Specifically, SB-TRPO’s updates align well with both reward and cost gradients, whereas CPO-style updates are often at best orthogonal to the reward gradient. Consistent with Theorem 4.2, steady improvement in both safety and task performance is observed empirically, rather than alternating phases of progress and feasibility recovery.

Lagrangian methods exhibit complementary limitations in hard-constraint regimes: under zero-cost thresholds, Lagrange multipliers grow monotonically and cannot decrease, making performance highly sensitive to initialisation: small values risk unsafe behaviour, while large values induce persistent over-conservatism.

In summary, SB-TRPO’s principled trustregion update enables steady reward accumulation and high safety, consistently outperforming state-of-the-art baselines across Safety Gymnasium tasks in balancing task performance with high safety.

Limitations. SB-TRPO targets hard constraints: it is not directly applicable to CMDPs with positive cost thresholds. 4 As with other policy optimisation methods (Schulman et al., 2015;Gu et al., 2024a), our performance guarantee (Theorem 4.2) assumes exact gradients and holds only approximately with estimates. Moreover, while our method achieves strong results in Safety Gymnasium, it does not guarantee almost-sure safety on the most challenging tasks.

This is foundational research on reinforcement learning with safety constraints, studied entirely in simulation. While our methods aim to reduce unsafe behaviour, they are not sufficient for direct deployment in safety-critical domains. We see no negative societal impacts and expect this work to contribute to safer foundations for future reinforcement learning systems.

Justification that ν > 0. The objective is linear in ∆ and g r ̸ = 0, so it is unbounded in the direction of g r without the quadratic constraint. The linear constraint ⟨g c , ∆⟩ ≤ -ϵ defines a half-space. In the non-degenerate case g c ̸ ∥ g r , this half-space alone cannot bound the linear objective. Therefore, the quadratic constraint must be active at the solution, which by complementary slackness implies ν > 0.

Form of KKT candidates. Substituting ∆ into the quadratic constraint

Hence all KKT candidates satisfy

using the above definitions of a, b and c, so that

Complementary slackness for the linear constraint. Either λ = 0 (linear constraint inactive) or λ > 0 with equality ⟨g c , ∆(λ)⟩ = -ϵ.

Case λ > 0. Solving ⟨g c , ∆(λ)⟩ = -ϵ and squaring both sides gives the quadratic equation Aλ 2 + Bλ + C = 0 displayed in the proposition. The unique positive root λ * yields the optimal step ∆ * = ∆(λ * ).

Summary. In the non-degenerate case, the quadratic constraint is active (ν > 0) to ensure a finite optimum. The linear constraint determines λ * , and ∆ * follows directly.

For M > 0, let B M (θ) be the M -ball around θ.

Lemma B.5. Assume J r and J c are L-Lipschitz smooth on B M (θ) and ∥∆ r ∥, ∥∆ c ∥ ≤ M for some M > 0. Then for all η ∈ [0, 1],

Proof. First, note that g r = ∇J r (θ) and g c = ∇J c (θ). Therefore, by assumption and Taylor’s theorem, for every η ∈ [0, 1], python sb-trpo.py –task SafetyPointGoal2-v0 –seed 2000 –beta 0.65

Additional options can be found in utils/config.py under single agent args.

For large-scale benchmarking, multiple algorithms can be launched in parallel with a single command:

python benchmark.py –tasks SafetyHopperVelocity-v1 SafetySwimmerVelocity-v1 –algo ppo_lag trpo_lag cpo cup sb-trpo –workers 25 –num-envs 20 –steps-per-epoch 20000 –total-steps 20000000 –num-seeds 5 –cost-limit 0 –beta 0.75

This command runs all baselines considered in the paper at a cost limit of 0, alongside our method with β = 0.7, using 25 training processes in parallel with 20 vectorized environments per process and 5 random seeds. Further options are documented in benchmark.py.

Finally, our ablations are implemented as sb-trpo rcritic (including a reward critic) and sb-trpo critic (including both reward and cost critics).

C.2. Supplementary Materials for Section 5.2

The training curves, which are smoothed with averaging over the past 20 epochs, are presented in Figure 6.

Additionally, we train longer on Point Button to confirm further feasibility and reward improvements. This is presented in Figure 7. As anticipated, the improvements are non-diminishing even for a 125% longer training run.

We compare the compute costs of our approach with the baselines w.r.t. the update times per epoch on a single, nonparallelized training run in Table 5. This demonstrates that training critics is expensive across all critic-integrated approaches.

We compare the qualitative behaviours of policies obtained from our approach with the baselines using recorded videos (provided in the supplementary material) across four benchmark tasks: Point Button, Car Circle, Car Goal, and Swimmer Velocity. The results in Table 1 are strongly corroborated by the behaviours observed in these videos.

Point Button. Most approaches exhibit low reward affinity and consequently engage in overconservative behaviours, such as moving away from interactive regions in the environment. Among the baselines, CUP, PPO-Lag, and SB-TRPO show visible reward-seeking behaviours, in decreasing order of intensity. CUP sometimes ignores obstacles entirely and is confused by moving obstacles (Gremlins). PPO-Lag avoids Gremlins more intelligently but is not particularly creative in approaching the target button. In contrast, SB-TRPO exhibits a creative strategy: it slowly circles the interactive region, navigating around moving obstacles to reach the target button.

Car Circle. CPO and C-TRPO fail to fully associate circling movement with reward acquisition, resulting in back-and-forth movements near the circle’s centre and partial rewards. Consequently, these policies rarely violate constraints. C3PO learns to circle in a very small radius to acquire rewards, but its circling behaviour is intermittent. P3O, CUP, and PPO-Lag learn to circle effectively but struggle to remain within boundaries, incurring costs. TRPO-Lag and SB-TRPO achieve both effective circling and boundary adherence.

Car Goal. CPO, C3PO, and C-TRPO display low reward affinity, leading to overconservative behaviours such as avoiding the interactive region. TRPO-Lag is unproductive and does not avoid hazards reliably. CUP and PPO-Lag are highly reward-driven but reckless with hazards. P3O begins to learn safe navigation around the interactive region, though occasional recklessness remains. SB-TRPO achieves productive behaviour while intelligently avoiding hazards, e.g., by slowly steering around obstacles or moving strategically within the interactive region.

Swimmer Velocity. CPO and C-TRPO sometimes move backward or remain unproductively in place. TRPO-Lag and PPO-Lag move forward but engage in unsafe behaviours. CUP and SB-TRPO are productive in moving forward while being less unsafe. C3PO and P3O are the most effective, moving forward consistently while exhibiting the fewest unsafe behaviours.

While our theoretical results (Theorem 4.2) guarantee consistent improvement in both reward and cost for sufficiently small steps, practical training exhibits deviations due to finite sample estimates and the sparsity of the cost signal in some tasks. We summarise task-specific observations:

• In Swimmer Velocity, some update steps may not immediately reduce incurred costs due to estimation noise, which explains delays in achieving perfect feasibility. • In Car Circle, policies that previously attained near-zero cost sometimes return temporarily to infeasible behaviour.

This arises because the update rule does not explicitly encode “distance” from infeasible regions within the feasible set. Nonetheless, policies eventually return to feasibility thanks to the guarantees of our approach. • In Hopper Velocity, after quickly achieving high reward, performance shows a slow decline accompanied by gradual improvements in cost. This reflects the prioritisation of feasibility improvement over reward during some updates, without drastically compromising either objective. • In navigation tasks, especially Button, Goal, and Push, the cost signal is sparse: a cost of 1 occurs only if a hazard is touched. This sparsity makes perfect safety more difficult to achieve, as most updates provide limited feedback about near-misses or almost-unsafe trajectories. Despite this, SB-TRPO steadily reduces unsafe visits and substantially outperforms baselines. Rewards ↑ -3.5 ± 0.9 -3.2 ± 1.2 -0.92 ± 0.33 -0.89 ± 0.27 -1.5 ± 0.5 -1.8 ± 0.7 Costs ↓ 6.1 ± 2.5 5.8 ± 2.8 9.2 ± 7.3 13 ± 8 9.3 ± 8.0 11 ± 8

Overall, these deviations are a natural consequence of finite sample estimates, quadratic approximations, and sparse cost signals. In spite of this, SB-TRPO consistently improves reward and safety together, achieving higher returns and lower violations than all considered baselines.

Angles between policy updates and cost gradients are plotted in Figure 9.

C.4. Supplementary Materials for Section 5.4

We present additional scatter plots for (raw) reward versus cost for our approach compared to selected baselines in Figure 8. SB-TRPO consistently achieves the best balance of performance and feasibility across all benchmark tasks, demonstrating robustness to the choice of β.

The values of metrics regarding the ablation study about the effect of critics are provided in Figure 10 and Tables 2 and5 to 7.

misaligned. Thus, reward improvement is guaranteed even before feasibility is achieved-something CPO and related methods such as C-TRPO do not guarantee during its feasibility recovery/attainment phase.

Moreover, compared to Lagrangian methods, which update via ∆ r + λ • ∆ c with λ that does not take the current reward and cost updates ∆ r and ∆ c into account and increases monotonically under zero-cost thresholds, these methods typically either over-or under-emphasise safety. By contrast, we dynamically weight ∆ r and ∆ c with µ defined in Equation ( 4), providing the aforementioned formal improvement guarantees for both reward and cost-something Lagrangian methods do not offer.

In summary, our contribution is not a basic penalty modification of TRPO but a principled, guaranteed-improvement update rule for hard-constrained CMDPs that subsumes CPO as a special case while avoiding its limitations, notably its collapse into over-conservatism.

Why CPO behaves poorly in hard-constraint settings. CPO attempts to maintain feasibility at every iteration. When constraints are violated, it prioritises cost reduction to restore feasibility. In hard-constraint regimes, this often drives the policy into trivially safe regions (e.g., corners without hazards), which are far from the states where reward can be obtained (e.g., far from goals in navigation tasks). Escaping such regions typically requires temporary constraint violations, which CPO forbids, leading to stagnation. Moreover, CPO and related methods such as C-TRPO do not provide reward-improvement guarantees during this feasibility-recovery phase.

Why our method behaves better. Because SB-TRPO is less greedy about attaining feasibility, it avoids collapsing into trivially safe but task-ineffective regions. Besides, by not switching between separate phases for reward improvement and feasibility recovery (as in CPO), our method exhibits markedly smoother learning dynamics.

Moreover, Figures 4 and9, show that SB-TRPO’s update directions align well with both the cost and reward gradients, whereas CPO’s updates are typically at best orthogonal to the reward gradient. This confirms empirically the performance improvement guarantee of Theorem 4.2, guaranteeing consistent progress in both safety and task performance.

In summary, SB-TRPO yields smoother learning, avoids collapse into conservative solutions, and enables steady reward accumulation over iterations. Empirically, this leads to substantially higher returns than CPO while still maintaining very low safety violations.

We continue with a more detailed comparison with C-TRPO (Milosevic et al., 2024).

Update Directions and Geometries. C-TRPO modifies the TRPO trust-region geometry by adding a barrier term that diverges near the feasible boundary. This yields a deformed divergence that increasingly penalises steps pointing towards constraint violation. When the constraint is violated, C-TRPO enters a dedicated recovery phase in which the update direction becomes the pure cost gradient; reward improvement is not pursued during this phase.

SB-TRPO keeps the standard TRPO geometry fixed and instead modifies the update direction itself: the step is the solution of a two-objective trust-region problem with a required fraction β of the optimal local cost decrease. This yields a dynamic convex combination of the optimal reward and cost directions. Unlike C-TRPO:

• there is no separate recovery phase,

• the update direction is always a mixture of (∆ r , ∆ c ) rather than switching geometries, and • reward improvement remains possible in every step whenever the reward and cost gradients are sufficiently aligned.

In short: C-TRPO mixes geometries (via a KL barrier that reshapes the trust region), while SB-TRPO dynamically mixes update directions. In particular, during recovery C-TRPO uses ∆ c , whereas SB-TRPO continues to use ∆, the solution of the trust-region problem considering both reward and cost; see Figure 1.

Finally, the safety-bias parameter β in SB-TRPO plays a role fundamentally different from the barrier coefficient in C-TRPO: β determines the minimum fraction of the optimal local cost decrease required from each step, while the barrier coefficient in C-TRPO controls the strength of the geometric repulsion from the boundary.

Connection to CPO. Both algorithms can be seen to generalise CPO in different ways:

↑ Safe Prob. ↑ Safe Rew. ↑ Safe Prob. ↑ Safe Rew. ↑ Safe Prob. ↑ Safe Rew. ↑ Safe Prob. ↑ Safe Rew. ↑ Safe Prob. ↑ Safe Rew. ↑ Safe Prob. ↑ Safe Rew. ↑ Safe Prob. ↑ Safe Rew. ↑ Safe Prob. ↑

The KL constraint corresponds to bounding the sampleaverage expected KL divergence under the current policy, as in TRPO, rather than the maximum KL across states.

Some studies customise the environments(Jayant & Bhatnagar, 2022;Yu et al., 2022), e.g. by providing more informative observations, making direct comparison of raw performance metrics across works impossible. To ensure fairness and facilitate future comparative studies, we report results only on the standard, unmodified Safety Gymnasium environments(Ji et al., 2023

).3 Code of reward-cost switching methods such as (P)CRPO(Xu et al., 2021; Gu et al., 2024a) and APPO(Dai et al., 2023) is not publicly available(Gu et al., 2024b).

We leave hybrid methods replacing conventional recovery phases (e.g. in CPO/C-TRPO) with our (Update 3) to future work.

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.