Recent advances in mechanistic interpretability suggest that intermediate attention layers encode token-level hypotheses that are iteratively refined toward the final output. In this work, we exploit this property to generate adversarial examples directly from attention-layer token distributions. Unlike prompt-based or gradientbased attacks, our approach leverages modelinternal token predictions, producing perturbations that are both plausible and internally consistent with the model's own generation process. We evaluate whether tokens extracted from intermediate layers can serve as effective adversarial perturbations for downstream evaluation tasks. We conduct experiments on argument quality assessment using the ArgQuality dataset, with LLaMA-3.1-Instruct-8B serving as both the generator and evaluator. Our results show that attention-based adversarial examples lead to measurable drops in evaluation performance while remaining semantically similar to the original inputs. However, we also observe that substitutions drawn from certain layers and token positions can introduce grammatical degradation, limiting their practical effectiveness. Overall, our findings highlight both the promise and current limitations of using intermediate-layer representations as a principled source of adversarial examples for stress-testing LLM-based evaluation pipelines.

Recent efforts in mechanistic interpretability have highlighted the wealth of information encoded within the layers of large language models (LLMs) (Meng et al., 2022;Sharkey et al., 2025). These layers, which are often overlooked in favor of the final outputs, have been shown to act as iterative predictors of the eventual response (Jastrzebski et al., 2018;nostalgebraist, 2020), providing insights into the model's generation process. While most of these techniques have heavily focused on interpretability, we argue that they could potentially be adapted to generate paraphrastic and adversarial examples for evaluation tasks -which generally operate over model generated data.

Probing the attention layers has multiple advantages -First, since the layers act as both iterative indicators of the final output (Belrose et al., 2023), and store related entities (Meng et al., 2022;Hernandez et al., 2024), they can provide natural language variations by potentially treating LLMs as knowledge bases. Second, these generations, can be obtained early on without necessitating running over all the layers (Din et al., 2024;Pal et al., 2023). Third, these generations might provide cues for model hallucinations (Yuksekgonul et al., 2024) as gradual deviations from the original token are obtained from the model itself. From an adversarial point of view, tokens from intermediate layers are valuable as they can act as perturbations to the original input. Specifically, the outputs are iteratively refined, since as the activations move towards the last layer they tend to move towards the direction of the negative gradient (Jastrzebski et al., 2018) or each successive layer achieving lower perplexity (Belrose et al., 2023). This is also precisely how adversarial examples are constructed -perturbing towards the direction of the positive gradient of the loss (Goodfellow et al., 2015).

Hence, in this study, we explore whether such fine-grained information extracted from the attention layers of large language models (LLMs) can be leveraged to generate adversarial examples on downstream natural language tasks, particularly critical tasks such as evaluation.

Specifically, in this work, we introduce two attention-based adversarial generation methods: attention-based token substitution and attentionbased conditional generation, both of which leverage intermediate-layer token predictions to construct plausible yet adversarial inputs.

Our paper is organized as follows: §2 first discusses related work in interpretability and genera-tion evaluation. §3 and §4 defines and implements the two approaches for generating examples. §5 finally discusses the results and analysis.

We now discuss some of the related work in mechanistic interpretability and LLM based evaluation to place our work in context.

Recent interpretability studies have explored the information encoded within the internal layers of large language models (LLMs) to better understand how models generate subsequent tokens. For instance, LogitLens and TunedLens (nostalgebraist, 2020;Belrose et al., 2023) demonstrate that intermediate layers can be made to predict tokens similar to those generated in the final layer, by attaching a trained or untrained unembedding matrix to them. Methods such as ROME (Meng et al., 2022) highlight the role of specific components, like MLP layers, in acting as key-value stores (Geva et al., 2021) that retain critical entities related to the input, such as associating “Seattle” with “Space Needle.” Besides, LLMs assign greater attention to constraint tokens when their outputs are factual vis-à-vis when they are hallucinating (Yuksekgonul et al., 2024). These findings underscore the utility of the attention layers beyond interpretability but also as knowledge probes (Alain and Bengio, 2016), to extract inherent knowledge. Hence, in this work, we explore if the information from these layers can act as a resource for generating adversarial examples.

Some techniques have been explored to probe intermediate layers to reveal token predictions (Belrose et al., 2023) for interpretability and early exiting to improve inference time (Geva et al., 2021).

ResNets (Jastrzebski et al., 2018) have been shown to perform iterative feature refinement (where each block improves slightly but keeps the semantics of the representation of the previous layer)).

On the other hand, evaluation of LLM-generated outputs has become increasingly important as models are deployed in high-stakes settings. LLMs-asjudges have emerged as a common paradigm for evaluating generated text, either through prompting or via reward models trained on human preferences. In retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) systems, LLM-based evaluators are frequently used to assess dimensions such as answer quality, groundedness, and context relevance (Dhole, 2025(Dhole, , 2024)). Recent work has also begun to examine the robustness of such evaluators, demonstrating that groundedness and factuality judgments can be manipulated through adversarial perturbations (Dhole et al., 2025). These findings motivate a closer examination of whether adversarial examples derived from model internals pose additional risks to LLMbased evaluation frameworks.

Prompt-based methods generate adversarial examples by instructing an LLM to rewrite or manipulate a given input according to a natural language directive (Dhole et al., 2024;Dhole and Agichtein, 2024). Typically, the prompt includes a task description, an example instance, and its associated label, followed by an instruction to generate an adversarial or misleading variant. While such methods are flexible and easy to apply in black-box settings, the generated examples may not correspond to naturally occurring model mistakes. As a result, prompt-based adversaries may diverge substantially from the original input distribution and fail to reflect the kinds of errors that arise organically during model generation. For this reason, we focus our study on attention-based methods that exploit the model’s own intermediate token predictions.

In this section, we discuss our two methods of generating examples and how we use them for evaluation. Both the methods start by substituting a token t x from a given text sequence.

Tokens Predicted by Attention Layers In order to extract a novel token t ′

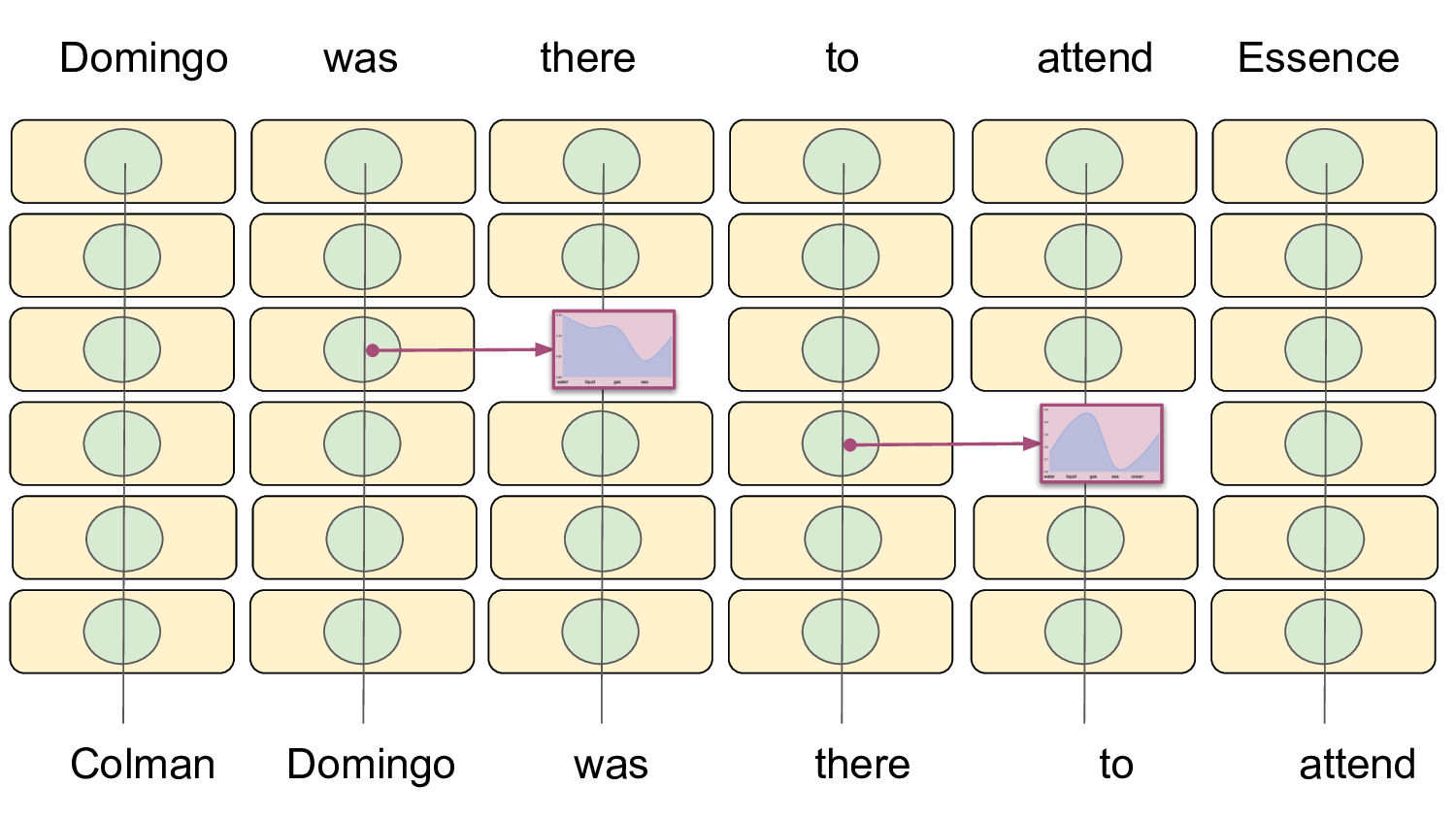

x , we first gather the token distributions of all the layers at all the positions. To do the same, we pass the input sequence through a LLaMA-3.1 instruct 8B (Dubey et al., 2024a) by first lens-tuning (Belrose et al., 2023) it over the final layer’s vocabulary. Lens-tuning, helps gauge the token distribution at each attention head and each layer as shown in Figure 1. Specifically, the token distribution is obtained by passing each attention layer’s outputs through a linear layer and an unembedding matrix. Lens-tuning involves training this layer to minimize the KL-divergence between the vocabulary distribution of the final layer and that of an intermediate layer. 1

This approach involves substituting a single token from an input sequence with a novel token estimated from the attention layers’ distribution. Formally, the transformation T for a given n-token sequence t 1∶n perturbed at position x ∈ [1,n] can be described as follows:

T ∶ (t 1 ,…,t x-1 ,t x ,t x+1 ,…) → (t 1 ,…,t x-1 ,t ′

x ,t x+1 ,…)

where t ′ x = A(l,x) is selected from the attention token distribution A at position x of an attention layer l, representing a plausible yet distinct alternative to the original token t x .

This method is lightweight and is likely to introduce minor semantic changes, allowing for efficient token-level editing with minimal disruption to the overall meaning.

We propose a second method to address the potential syntactic inconsistencies of the previous token substitution. In this approach, the substituted sequence until token x serves as input for autoregressively generating the remaining sequence tokens, ensuring coherence and fluency. The transformation is described as:

1 The tuned lens model is available on Hugging-Face (Wolf et al., 2020) at hf.co/kdhole/Llama-3.

In this case, the model autoregressively generates all tokens after position x viz., t ′ x+1 ,…,t ′ n by conditioning on the modified sequence t 1 ,…,t x-1 ,t ′ x , thereby aligning the entire sequence syntactically and semantically. The first token t ′ x = A(l,x) is obtained as earlier from the attention distribution.

This method produces novel and diverse examples while ensuring syntactic correctness and coherence of the sequence. However, the newly generated tokens may introduce shifts in meaning, diverging from the original context. To minimize this effect, we choose token positions to substitute at the latter parts of the sequence so that there is a large overlap in the initial context used to dictate the rest of the tokens. The full procedure for adversarial example generation, including token and layer selection, is summarized in Algorithm 1.

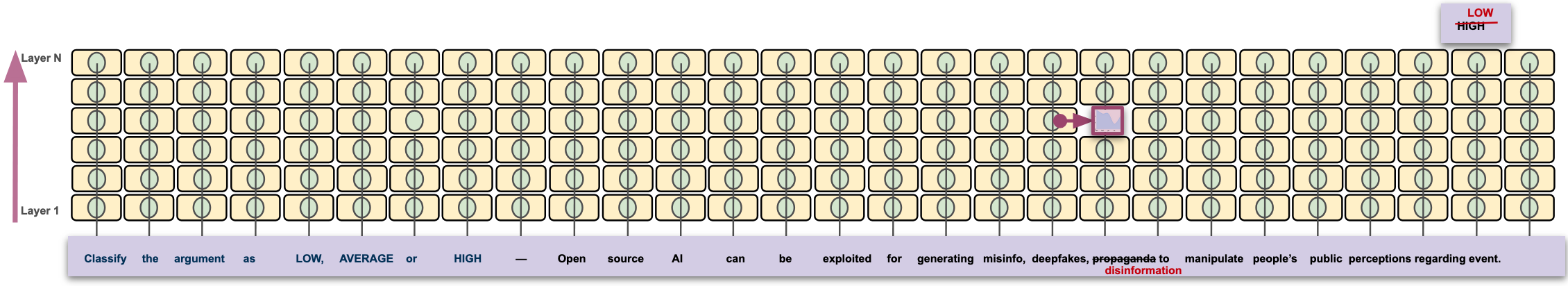

For evaluation, we use the LLaMA-3.1-Instruct-8B model (Dubey et al., 2024b). We focus exclusively on argument quality assessment using the ArgQuality corpus (Habernal and Gurevych, 2016), a task well-suited for token-level perturbations since small lexical changes can significantly alter perceived argument strength.

L\T 16 32 48 64 80 128 28 .423 .403 .389 .437 .479 .420 24 .408 .403 .417 .423 .471 .389 20 .451 .403 .366 .451 .429 .403 16 .408 .389 .394 .394 .389 .371 12 .408 .375 .451 .403 .366 .366 8 .479 .417 .389 .394 .389 .389 Table 1: Effect of Attention Token Substitution using adversarial tokens from different layers (L) and different token positions (T).

L\T 16 32 48 64 80 128 28 .280 .400 .480 .393 .333 .316 24 .330 .400 .370 .346 .400 .500 20 .300 .380 .430 .328 .263 .500 16 .320 .410 .360 .439 .471 .591 12 .280 .460 .380 .482 .526 .450 8 .250 .410 .400 .418 .350 .273 Table 2: Effect of Attention Token Conditioned Generation using adversarial tokens from different layers (L) and different token positions (T).

ArgQuality classifies arguments into three categories: low, average, and high quality. We construct evaluation instances in the form of (topic, stance, chosen argument, rejected argument) tuples and measure how often the model correctly prefers the higher-quality argument. This setting allows us to directly assess whether attention-based adversarial examples can degrade evaluation performance without substantially altering semantic content.

We first assess answer quality, by evaluating whether these examples are useful for testing the robustness capabilities of both trained and finetuned models. This was done by first evaluating the model’s performance on ArgQuality’s test set and the modified test set generated from the two methods discussed in §3. Our evaluation set consists of 75 test examples from the ArgQuality corpus which we transform in the form of (topic, stance, chosen argument, rejected argument) tuples.

We lenstune the LLaMA-3.1-Instruct-8B model so that we can display the tokens at each layer (Belrose et al., 2023) and use them for generating adversarial sequences. We specifically generate the adversarial counterparts for the chosen and rejected arguments in the same. In our experiments, we choose x = 10 and l = 18. For evaluation, we use a few-shot prompt displayed in Figure 3.

The results indicate that adversarial tokens extracted from a wide range of layers and token positions can negatively impact evaluation accuracy. However, we also observe that certain configurations-particularly substitutions at later token positions-can paradoxically improve performance. This suggests that not all intermediate-layer tokens act as effective adversarial perturbations, and that both layer depth and token position play a critical role in determining adversarial effectiveness. Tables 1 and 2 show that substitutions drawn from mid-to-late layers (e.g., layers 16-28) generally induce larger performance drops than those from earlier layers, particularly when applied at moderate token positions. However, very late token substitutions occasionally improve accuracy, likely by introducing clarifying or corrective lexical choices. Table 3 further confirms this trend at the aggregate level: evaluation accuracy drops from 0.42 to 0.34 in the few-shot setting and from 0.60 to 0.57 in the fine-tuned setting when adversarial examples generated via our attention-based methods are introduced. Together, these results indicate that attention-layer-derived perturbations can reliably degrade evaluator performance, though their impact is highly sensitive to where in the sequence and from which layer the token is extracted.

Evaluation tasks provide a natural test bed for attention-based adversarial example generation, as LLM-based judges routinely consume modelgenerated text that may already contain subtle inconsistencies or errors. In this work, we show that intermediate attention layers can be exploited to generate adversarial examples without requiring access to the model’s final layer or gradients.

While our results demonstrate consistent successful attacks, we also find that many intermediatelayer substitutions lead to grammatical degradation, limiting their effectiveness as practical adversaries.

In that regard, we introduce the attention token conditioned approach. Our preliminary study highlights the need for more selective token and layer “Rate the quality of the given argument among ’low’, ‘average’ and ‘high’. Just mention either of the options and do not provide an explanation. The argument should be rated high if it convinces the reader towards the expected stance for a controversial topic.\n” “\n\nThe topic is ‘Ban Plastic Water Bottles’.\nThe stance is ‘No bad for the economy’.\nHere is the argument: U.S. alone grew by over 13%. According to research and consulting done by the Beverage Marketing Corporation, the global bottled water industry has exploded to over $35 billion. Americans alone paid $7.7 billion for bottled water in 2002. In 2001, for example, globally bottled water companies produced over 130,000 million liters of water. This produced roughly 35,000 million dollars in revenue for the world’s thousands of bottled water companies in 2001.\nRating: ‘average’” “\n\nThe topic is ‘Is porn wrong’.\nThe stance is ‘Yes porn is wrong’.\nHere is the argument: Porn is definitely wrong. Porn is like an addiction to some people which is unhealthy and can lead to guilt and lust. An addiction to porn gives an unhealthy image of real sex. Porn promotes the fact that sex is totally based on pleasure, but it is actually based on love and affection also. Porn inspired numerous crimes that sometimes abuse the rights and virginity of many people.\nRating: ‘high’” “\n\nThe topic is ‘William Farquhar ought to be honoured as the rightful founder of Singapore’.\nThe stance is ‘Yes of course’.\nHere is the argument: Farquhar contributed significantly, even forking out his own money to start up the colony carved out of the jungle, by first offering money as an incentive for people to hunt and to exterminate rats and centipedes. Raffles did nothing of that sort.\nRating: ’low’” f"\n\nThe topic is {topic}.\nThe stance is {stance}.\nHere is the argument: {arg}\nRating:" selection mechanisms, and the potential to extract knowledge from intermediate layers gradually. Future work should explore principled criteria for identifying syntactically valid and semantically impactful substitutions, as well as extending these methods to domains where strict linguistic structure is less critical. For example, structured domains such as electronic health records, where substituting diagnosis or procedure codes may have significant downstream effects, present a promising direction for applying attention-based adversarial methods.

We focus on evaluation tasks rather than general classification, as evaluation models are especially likely to encounter generations influenced by near-final-layer representations. Overall, this study demonstrates that intermediate-layer representations offer a promising-but currently imperfect-source of adversarial examples for stresstesting LLM evaluation pipelines.

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.