Probing Scientific General Intelligence of LLMs with Scientist-Aligned Workflows

📝 Original Info

- Title: Probing Scientific General Intelligence of LLMs with Scientist-Aligned Workflows

- ArXiv ID: 2512.16969

- Date: 2025-12-18

- Authors: Wanghan Xu, Yuhao Zhou, Yifan Zhou, Qinglong Cao, Shuo Li, Jia Bu, Bo Liu, Yixin Chen, Xuming He, Xiangyu Zhao, Xiang Zhuang, Fengxiang Wang, Zhiwang Zhou, Qiantai Feng, Wenxuan Huang, Jiaqi Wei, Hao Wu, Yuejin Yang, Guangshuai Wang, Sheng Xu, Ziyan Huang, Xinyao Liu, Jiyao Liu, Cheng Tang, Wei Li, Ying Chen, Junzhi Ning, Pengfei Jiang, Chenglong Ma, Ye Du, Changkai Ji, Huihui Xu, Ming Hu, Jiangbin Zheng, Xin Chen, Yucheng Wu, Feifei Jiang, Xi Chen, Xiangru Tang, Yuchen Fu, Yingzhou Lu, Yuanyuan Zhang, Lihao Sun, Chengbo Li, Jinzhe Ma, Wanhao Liu, Yating Liu, Kuo-Cheng Wu, Shengdu Chai, Yizhou Wang, Ouwen Zhangjin, Chen Tang, Shufei Zhang, Wenbo Cao, Junjie Ren, Taoyong Cui, Zhouheng Yao, Juntao Deng, Yijie Sun, Feng Liu, Wangxu Wei, Jingyi Xu, Zhangrui Li, Junchao Gong, Zijie Guo, Zhiyu Yao, Zaoyu Chen, Tianhao Peng, Fangchen Yu, Bo Zhang, Dongzhan Zhou, Shixiang Tang, Jiaheng Liu, Fenghua Ling, Yan Lu, Yuchen Ren, Ben Fei, Zhen Zhao, Xinyu Gu, Rui Su, Xiao-Ming Wu, Weikang Si, Yang Liu, Hao Chen, Xiangchao Yan, Xue Yang, Junchi Yan, Jiamin Wu, Qihao Zheng, Chenhui Li, Zhiqiang Gao, Hao Kong, Junjun He, Mao Su, Tianfan Fu, Peng Ye, Chunfeng Song, Nanqing Dong, Yuqiang Li, Huazhu Fu, Siqi Sun, Lijing Cheng, Jintai Lin, Wanli Ouyang, Bowen Zhou, Wenlong Zhang, Lei Bai

📝 Abstract

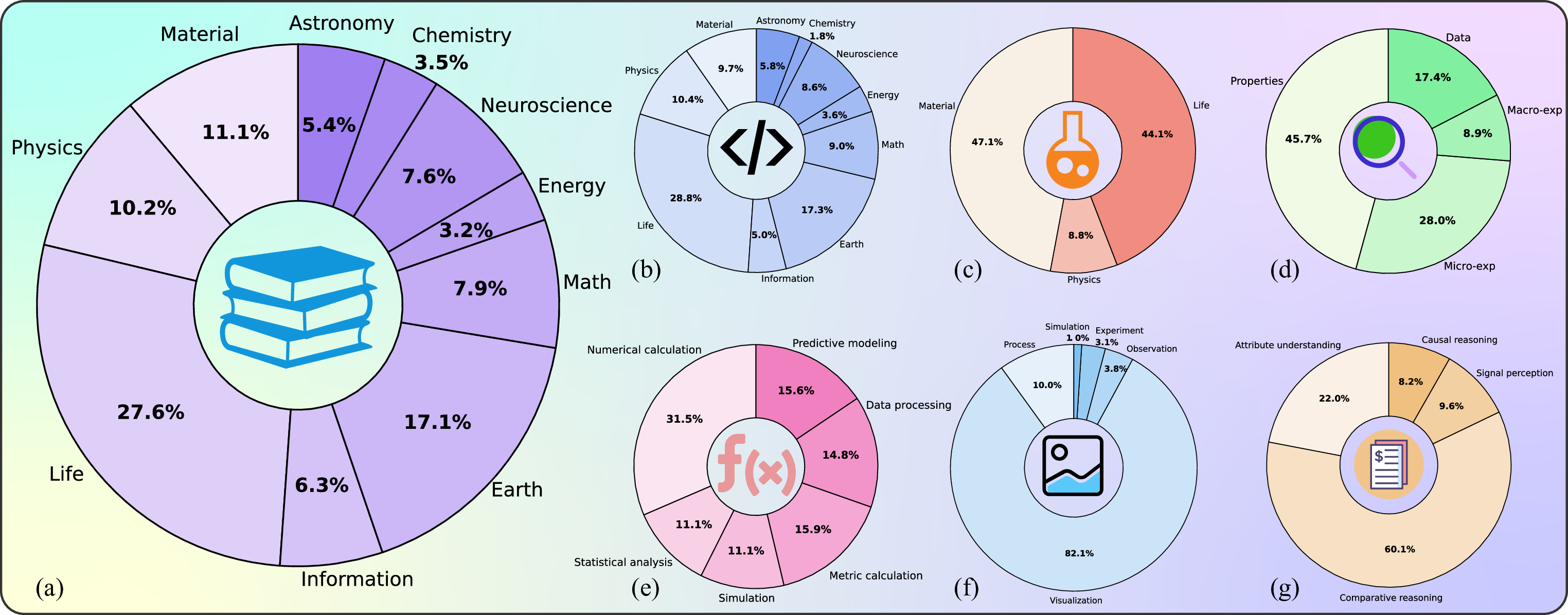

Despite advances in scientific AI, a coherent framework for Scientific General Intelligence (SGI)-the ability to autonomously conceive, investigate, and reason across scientific domains-remains lacking. We present an operational SGI definition grounded in the Practical Inquiry Model (PIM: Deliberation, Conception, Action, Perception) and operationalize it via four scientist-aligned tasks: deep research, idea generation, dry/wet experiments, and experimental reasoning. SGI-Bench comprises over 1,000 expert-curated, cross-disciplinary samples inspired by Science's 125 Big Questions, enabling systematic evaluation of state-of-the-art LLMs. Results reveal gaps: low exact match (10-20%) in deep research despite step-level alignment; ideas lacking feasibility and detail; high code executability but low execution result accuracy in dry experiments; low sequence fidelity in wet protocols; and persistent multimodal comparative-reasoning challenges. We further introduce Test-Time Reinforcement Learning (TTRL), which optimizes retrieval-augmented novelty rewards at inference, enhancing hypothesis novelty without reference answer. Together, our PIM-grounded definition, workflow-centric benchmark, and empirical insights establish a foundation for AI systems that genuinely participate in scientific discovery.📄 Full Content

Figure 1 | Scientific General Intelligence (SGI) We define SGI as an AI that can autonomously navigate the complete, iterative cycle of scientific inquiry with the versatility and proficiency of a human scientist. The teaser illustrates the Practical Inquiry Model’s four quadrants-Deliberation (synthesis and critical evaluation of knowledge), Conception (idea generation), Action (experimental execution), and Perception (interpretation)-and how SGI-Bench operationalizes them through four task categories and an agent-based evaluation paradigm, together providing a principle-grounded, measurable framework for assessing scientific intelligence.

Large language models (LLMs) [1,2,3,4,5] are achieving and even exceeding human-level performance on a diverse array of tasks, spanning multidisciplinary knowledge understanding, mathematical reasoning, and programming. This rapid progress has ignited a vibrant debate: some view these models as early signals of artificial general intelligence (AGI) [6,7], whereas others dismiss them as mere “stochastic parrots [8],” fundamentally constrained by their training data. As these models evolve, the frontier of AGI research is shifting towards the most complex and structured of human endeavors: scientific inquiry [9]. We argue that demonstrating genuine scientific general intelligence (SGI) represents a critical leap toward AGI, serving as a definitive testbed for advanced reasoning, planning, and knowledge creation capabilities. However, much like AGI, the concept of SGI remains frustratingly nebulous, often acting as a moving goalpost that hinders clear evaluation and progress.

This paper aims to provide a comprehensive, quantifiable framework to cut through this ambiguity, starting with a concrete definition grounded in established theory:

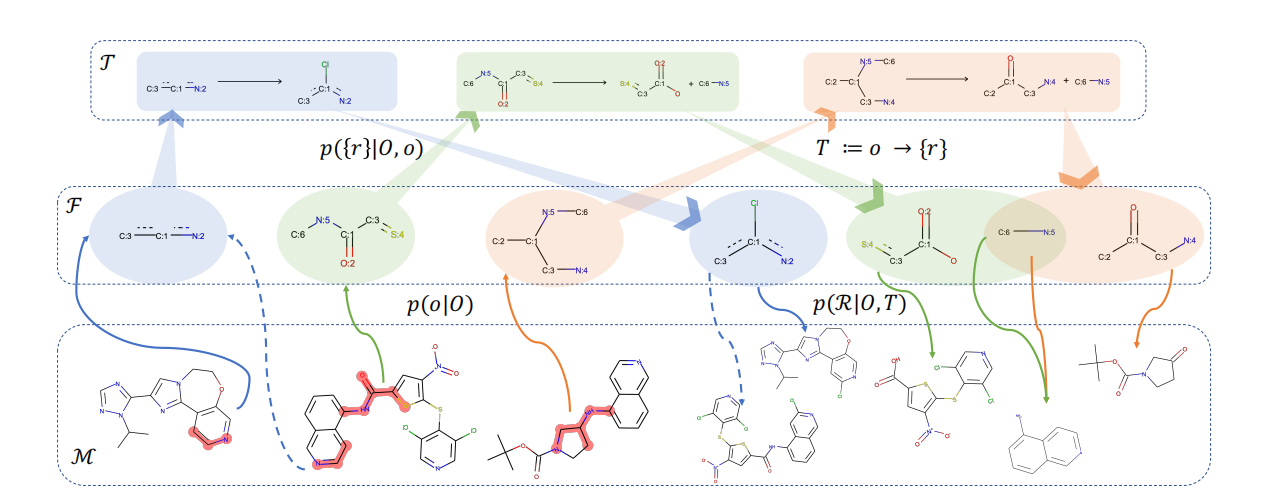

To operationalize this definition, we ground our approach in the Practical Inquiry Model [10,11], a theoretical framework that deconstructs the scientific process into a cycle of four core cognitive activities. This model provides a taxonomic map of scientific cognition through four distinct, interdependent quadrants (Figure 1): Deliberation (the search, synthesis, and critical evaluation of knowledge), Conception (the generation of ideas), Action (the practical implementation via experiments), and Perception (the awareness and interpretation of results). An AI exhibiting true SGI must possess robust capabilities across this entire spectrum. This four-quadrant framework provides a conceptual taxonomy of scientific cognition and forms the foundation for an operational definition of SGI-one that specifies what kinds of planning, knowledge creation and reasoning an AI must demonstrate to qualify as scientifically intelligent. Translating this operational definition into measurable criteria requires examining how current evaluations of AI intelligence align with, or deviate from, this framework. Identifying these gaps is essential for clarifying what existing assessments capture and what they overlook in defining Scientific General Intelligence.

Grounded in this four-quadrant definition of SGI, we examine how existing benchmarks operationalize scientific reasoning. Most current evaluations capture only fragments of the SGI spectrum. For instance, MMLU [12] and SuperGPQA [13] focus on multidisciplinary knowledge understanding-corresponding mainly to the Deliberation quadrant-while GAIA [14] emphasizes procedural tool use aligned with Action. HLE [15] further raises difficulty through complex reasoning, yet still isolates inquiry stages without integrating the practical or interpretive cycles that characterize real scientific investigation. Collectively, these benchmarks present a fragmented view of scientific intelligence. Their disciplinary scope remains narrow, their challenges seldom reach expert-level reasoning, and-most crucially-they frame inquiry as a static, closed-domain question-answering task. This abstraction neglects the creative, procedural, and self-corrective dimensions central to SGI, meaning that what is currently measured as “scientific ability” reflects only a limited slice of true Scientific General Intelligence.

Thus, to concretize the proposed definition of Scientific General Intelligence (SGI), we develop SGI-Bench: A Scientific Intelligence Benchmark for LLMs via Scientist-Aligned Workflows. Rather than serving as yet another performance benchmark, SGI-Bench functions as an operational instantiation of the SGI framework, quantitatively evaluating LLMs across the full spectrum of scientific cognition defined by the Practical Inquiry Model. By design, SGI-Bench is comprehensive in its disciplinary breadth, challenging in its difficulty, and unique in its explicit coverage of all four capabilities central to our definition of SGI. The benchmark structure is therefore organized into four corresponding task categories:

• Building upon our theoretical framework, the construction of SGI-Bench operationalizes the proposed definition of Scientific General Intelligence (SGI). We began with foundational topics drawn from Science’s 125 Big Questions for the 21st Century [16], spanning ten major disciplinary areas. Through multi-round collaborations with domain experts, we identified high-impact research problems and curated raw source materials from leading journals such as Nature, Science, and Cell. Together with PhD-level researchers, we implemented a multi-stage quality control pipeline involving human annotation, model-based verification, and rule-based consistency checks. The resulting benchmark comprises over 1,000 expert-curated samples that concretely instantiate the reasoning, creativity, and experimental competencies central to our definition of SGI.

To evaluate performance across these four dimensions, we found that conventional “LLM-as-ajudge” [17] paradigms are insufficient to handle the diverse and specialized metrics required by SGI assessment. To address this, we developed an agent-based evaluation framework following an Agent-as-a-judge [18] paradigm. Equipped with tools such as a web search interface, Python interpreter, file reader, PDF parser, and discipline-specific metric functions, this framework ensures rigor, scalability, and transparency. It operates through four interdependent stages-Question Selection, Metric Customization, Prediction & Evaluation, and Report Generation-each coordinated by specialized agents aligned with different aspects of scientific inquiry.

Applying SGI-Bench to a wide spectrum of state-of-the-art LLMs reveals a unified picture: while modern models achieve pockets of success, they fall far short of the integrated reasoning required for scientific intelligence.

• In deep scientific research, models can retrieve relevant knowledge but struggle to perform quantitative reasoning or integrate multi-source evidence; exact-match accuracy remains below 20% and often collapses on numerical or mechanistic inference. • In idea generation, models show substantial deficits in realization. This manifests in underspecified implementation steps and frequent proposals that lack actionable detail or fail basic feasibility checks. • In dry experiments, even strong models fail on numerical integration, simulation fidelity, and scientific code correctness, revealing a gap between syntactic code fluency and scientific computational reasoning. • In wet experiments, workflow planning shows low sequence similarity and error-prone parameter selection, with models frequently omitting steps, misordering actions, or collapsing multi-branch experimental logic. • In multimodal experimental reasoning, models perform better on causal and perceptual reasoning but remain weak in comparative reasoning and across domains such as materials science and earth systems. • Across tasks, closed-source models demonstrate only a marginal performance advantage over open-source models. Even the best closed-source system achieves an SGI-Score of around 30/100, reflecting that current AI models possess relatively low capability in multi-task scientific research workflows, and remain far from proficient for integrated, real-world scientific inquiry.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that current LLMs instantiate only isolated fragments of scientific cognition. They remain constrained by their linguistic priors, lacking the numerical robustness, procedural discipline, multimodal grounding, and self-corrective reasoning loops essential for scientific discovery.

Because genuine scientific inquiry is inherently open-ended and adaptive, we further explore how SGI may emerge under test-time learning dynamics. Preliminary experiments using test-time scaling [19] and reinforcement learning [20] suggest that models can enhance hypothesis formation and reasoning through minimal unlabeled feedback. This adaptive improvement provides empirical support for viewing Scientific General Intelligence not as a static property, but as a dynamic capacity that can evolve through iterative, self-reflective reasoning cycles.

In summary, this work provides a principle-grounded definition of Scientific General Intelligence (SGI) and a corresponding framework for its empirical study. By formalizing the cognitive cycle of scientific inquiry and operationalizing it through SGI-Bench, we clarify what it means for an AI to exhibit scientific intelligence in both theory and practice. While not a final answer, this definition establishes a concrete path for future research-linking conceptual understanding with measurable progress toward AI systems capable of genuine scientific reasoning and discovery.

Scientific General Intelligence (SGI) refers to an AI system capable of engaging in the full cycle of scientific inquiry with autonomy, versatility, and methodological rigor. Unlike systems that excel at isolated reasoning tasks, an SGI-capable model must integrate knowledge retrieval, idea formation, action execution, and evidence-based interpretation into a coherent, iterative workflow.

To formalize this notion, we characterize scientific cognition through four interdependent stages: Deliberation (evidence search, synthesis, and critical assessment), Conception (generation of hypotheses and ideas), Action (implementation of experiments or simulations), and Perception (interpretation of empirical results).

Grounded in this framework, we provide an operational definition: an AI system exhibits SGI if it can (1) retrieve, synthesize, and critically evaluate knowledge; (2) generate scientifically grounded and novel ideas; (3) plan and execute experimental procedures; (4) interpret empirical outcomes with causal and contextual awareness.

This definition highlights a central limitation in existing benchmarks [12,13,14,15]: most evaluate factual recall or single-step reasoning, but few examine the structured, long-horizon workflows that constitute real scientific inquiry.

Building on the operational definition of SGI established in the previous section, we introduce SGI-Bench (Scientific Intelligence Benchmark for LLMs via Scientist-Aligned Workflows) -a benchmark designed to empirically evaluate the extent to which large language models (LLMs), vision-language models (VLMs), and agent-based systems exhibit the cognitive and procedural abilities required for scientific discovery. SGI-Bench systematically measures AI performance across 10 core scientific domains -astronomy, chemistry, earth science, energy, information science, life science, materials science, neuroscience, physics and math -providing a panoramic view of how AI systems engage with scientific reasoning across disciplines. Its task design draws inspiration from the seminal article 125 Questions: Exploration and Discovery [16] published in Science, ensuring both disciplinary breadth and societal relevance.

At the heart of SGI-Bench lies the principle of scientist alignment-the commitment to evaluating models under conditions that authentically mirror real scientific workflows. This concept manifests in several ways:

• The task designs closely mirror the real-world research scenarios encountered by scientists in their work, ensuring that each task is intrinsically tied to the scientific discovery process. • The raw materials used in task construction are sourced directly from scientists, ensuring the authenticity and relevance of the content. • Scientists have been closely involved in the process of constructing the benchmark, with a scientist-in-the-loop approach, ensuring the tasks reflect the nuances of actual scientific workflows. • The final evaluation scores are aligned with the checklist based on the needs of real scientific research scenarios from scientists, which ensures that the assessments genuinely reflect the scientific utility of the models.

SGI-Bench departs from conventional benchmarks that emphasize factual recall or single-turn reasoning. Instead, it operationalizes the long-horizon workflow of scientific discovery into four interdependent stages: literature review(Deliberation), methodology design(conception), experiment implementation(Action), and experimental analysis(Perception). These stages correspond to fundamental capabilities required of AI systems: information integration and understanding(Scientific Deep Research), design and planning(Idea Generation), experimental execution(Dry/Wet Experiment), and reasoning-based interpretation(Experimental Reasoning). Together, they form a unified framework that measures not only what models know but how they think, plan, and adapt in pursuit of new knowledge.

Scientific deep research refers to a thorough and comprehensive investigation of a specific scientific topic, combining elements of both AI-driven deep research [21,22,23] and scientific meta-analysis [24,25]. This task typically involves multi-step reasoning, web searches, document retrieval, and data analysis [26,27,28]. Drawing inspiration from AI’s deep research, which often relies on multihop searches to gather diverse information across multiple sources [29], it also incorporates the methodology of meta-analysis from the scientific community. Meta-analysis, a rigorous form of scientific research, synthesizes existing literature to derive precise, data-driven conclusions and extract quantitative insights from a large body of studies. Unlike general deep research, which may focus on qualitative understanding, meta-analysis centers on aggregating and analyzing data to produce statistically significant results. By combining the multi-hop search nature of AI’s deep research with the systematic, evidence-based approach of meta-analysis, this task ensures results that are both scientifically precise and meaningful. The ability to perform scientific deep research is crucial for advancing scientific knowledge, as it enables AI models to replicate the process of reviewing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research to formulate new, data-driven hypotheses. [30,31] Deep Research comprises multiple forms including literature inquiry [32], report-style reasoning [33] and so on. In this benchmark, we focus on literature-inquiry-centric deep research, where the model identifies and integrates relevant scientific knowledge from provided sources. This process often involves unit verification, quantitative interpretation, and causal assessment-abilities fundamental to scientific reasoning and still challenging for current AI systems. By constraining the task to literature Table 1 | Scientific Deep Research Types: Four representative categories of inquiry targets and their roles in the scientific workflow.

Data Focused on retrieving or analyzing structured datasets, such as event counts, statistical summaries, or dataset-specific attributes.

Supports quantitative literature review and provides a foundation for identifying trends or anomalies.

Concerned with identifying or inferring material, molecular, or system properties, often requiring interpretation of experimental results or theoretical knowledge.

Bridges literature review with methodology design by clarifying key parameters.

Micro-experiment Small-scale controlled experiments, often involving chemical reactions, physical transformations, or laboratory processes under specific conditions.

Provides simulated reasoning over experimental procedures and outcomes.

Macro-experiment Large-scale or natural experiments, such as astronomical events, climate observations, or geophysical phenomena.

Extends literature review to global or long-term observations, anchoring hypotheses in real-world contexts.

• Background (B): A detailed background of the research topic, including the scientific field and subfields, to avoid ambiguities in terminology. • Constraints (C): Constraints such as experimental settings, scientific assumptions, and data sources that frame the problem appropriately. • Data (D): Any experimental or empirical data directly mentioned in the task, which might be either explicitly provided or inferred. • Question (Q): A specific, focused question that the task aims to address, such as determining a particular quantity or its variation over time. • Response Requirements (R): Specifications for the answer, including the required units and whether the answer should be an integer or a decimal with a specified number of decimal places.

• Steps (S): A detailed, step-by-step approach that the system uses to retrieve and process data or perform reasoning. • Answer (A): A precise numerical or string-based response, such as a specific value or a phrase.

S, A = LLM/Agent(B, C, D, Q, R)

Figure 3 | Scientific Deep Research Task: Inputs, outputs, and formulation for literature-driven quantitative inquiry combining multi-step reasoning and meta-analysis.

Idea generation is a critical component of the scientific process, corresponding to the stage of research methodology design. At this stage, researchers synthesize existing knowledge, engage in associative and creative thinking, and propose new approaches to address current challenges. It embodies the creative essence of scientific inquiry and shapes the direction and potential impact of subsequent research.

In real-world scientific workflows, idea generation typically occurs after researchers have completed a thorough literature review. They integrate prior findings, identify limitations or knowledge gaps, and use creative reasoning to formulate new hypotheses, methods, or frameworks aimed at overcoming these shortcomings. In this sense, idea generation serves as the crucial link between literature understanding and methodological innovation.

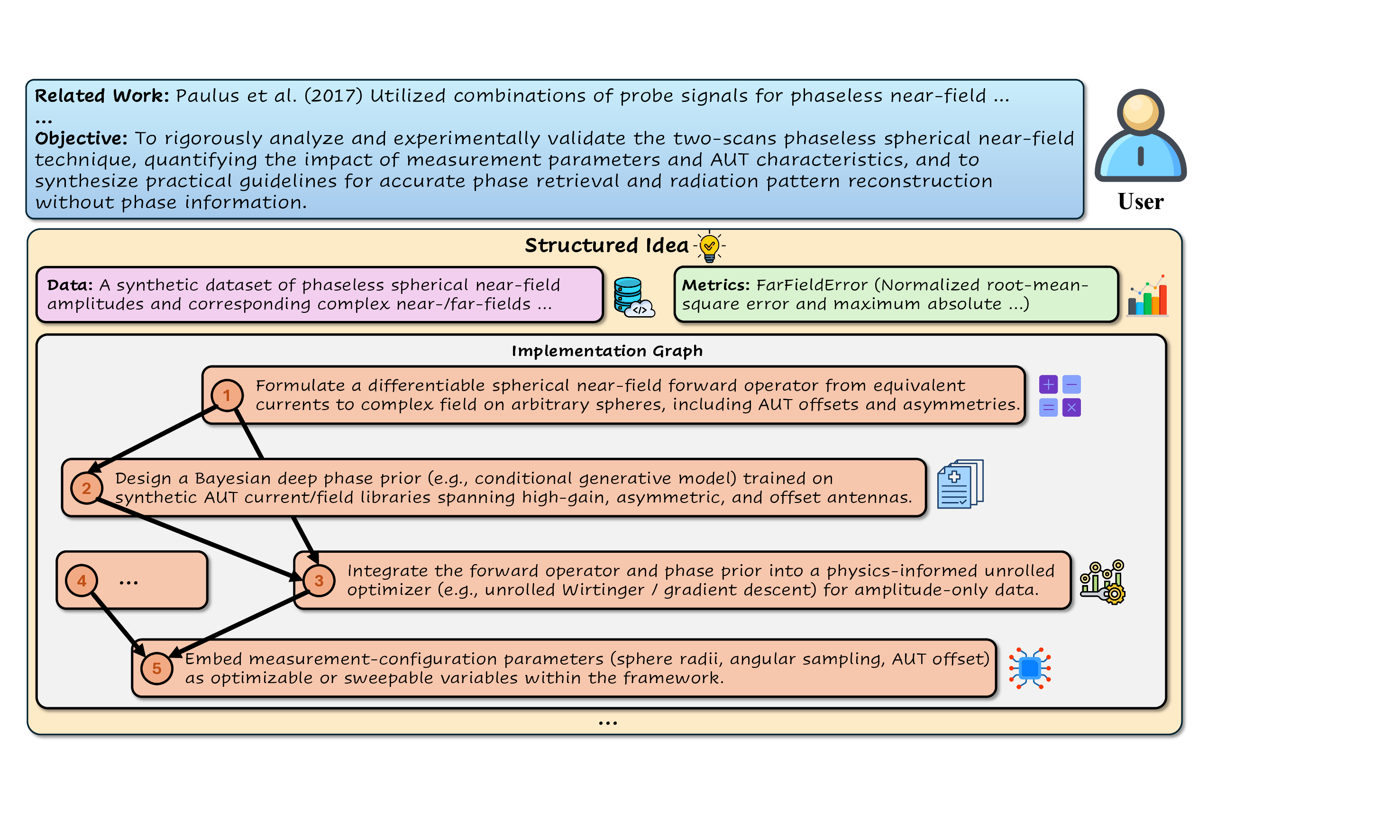

However, because idea generation is an open-ended and highly creative task, its evaluation is inherently challenging. In principle, scientific ideas span a wide spectrum from high-level hypotheses to fully specified methodological plans [34,35,36]. Evaluating the quality of open-ended hypotheses-those with substantial conceptual freedom and without explicit implementation structure-requires extensive human expert review to achieve even a modest degree of inter-rater reliability and public defensibility. Such large-scale expert adjudication is beyond the practical scope of this version of the benchmark.

Consequently, our current Idea Generation evaluation focuses on the methodological-design component of an idea-i.e., how a proposed approach is operationalized through data usage, step-by-step procedures, evaluation protocols, and expected outcomes. This component offers a more constrained structure that enables measurable, partially automatable assessment while still reflecting an essential aspect of scientific ideation. We view this as a pragmatic starting point, and future versions of the benchmark may incorporate broader hypothesis-level evaluation once sufficiently robust expert-sourced ground truth becomes feasible.

To make the assessment more systematic and tractable, we decompose an originally holistic idea into several interrelated components, forming a structured representation of the idea. This decomposition enables more fine-grained evaluation along dimensions such as effectiveness, novelty, level of detail, and feasibility [37].

Task Input

• Related Work (RW): A summary of existing research relevant to a certain research direction, providing context for new ideas. • Challenge (C): The current challenges in the field and the limitations of existing solutions. • Limitation (L): Specific shortcomings or constraints of current research that new ideas need to address. • Motivation (M): The perspective and motivation of addressing the limitations in this research direction. • Task Objective (TO): The primary goal of the task, such as generating ideas that solve identified challenges or improve existing solutions.

• Existing Solutions (ES): A description of the current approaches or solutions available in the field.

• Core Idea (CI): The central novel idea or concept generated to address the research challenge. • Implementation Steps (IS): The steps or procedures required to implement the core idea. • Implementation Order (IO) : The sequence in which the implementation steps should be executed. • Data (D) : The data that will be used to implement the idea or evaluate its effectiveness.

• Evaluation Metrics (EM): The criteria for assessing the success or relevance of the generated idea. • Expected Outcome (EO): The anticipated result or contribution the idea is expected to achieve.

CI, IS, IO, D, EM, EO = LLM/Agent(RW, C, L, M, TO, ES)

Figure 4 | Idea Generation Task: Inputs, outputs, and formulation for methodology design, integrating evaluation metrics and structured implementation planning.

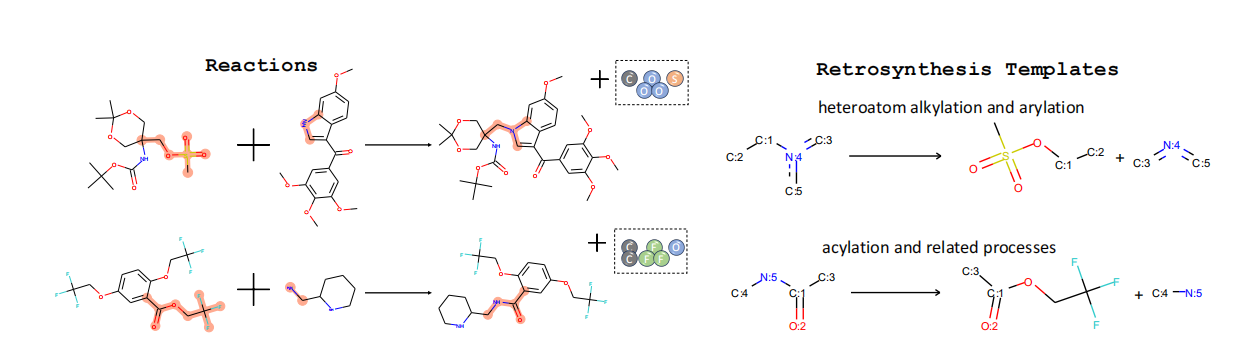

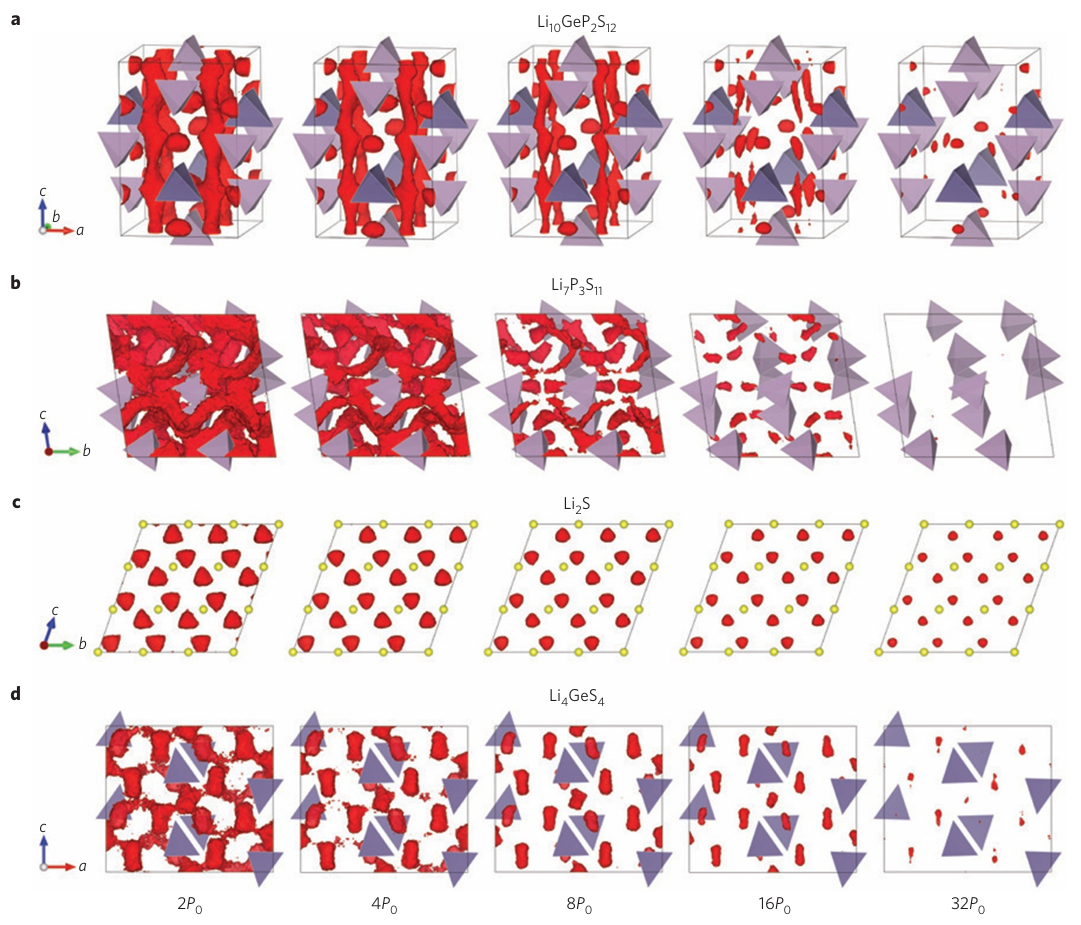

Scientific experimentation represents the core of the discovery process, bridging theoretical formulation and empirical validation [30]. Within SGI-Bench, we formalize this process into two complementary categories: dry and wet experiments. Dry experiments capture computational and simulation-based studies-where AI assists in generating, refining, or executing scientific code that models physical phenomena. [38,39] Wet experiments, by contrast, simulate laboratory-based workflows, requiring the model to plan and reason about sequences of actions involving physical instruments, reagents, and procedural parameters [40,41]. Together, these two categories span the continuum from theoretical abstraction to empirical realization, offering a holistic evaluation of how AI can assist scientists in both virtual and physical experimentation.

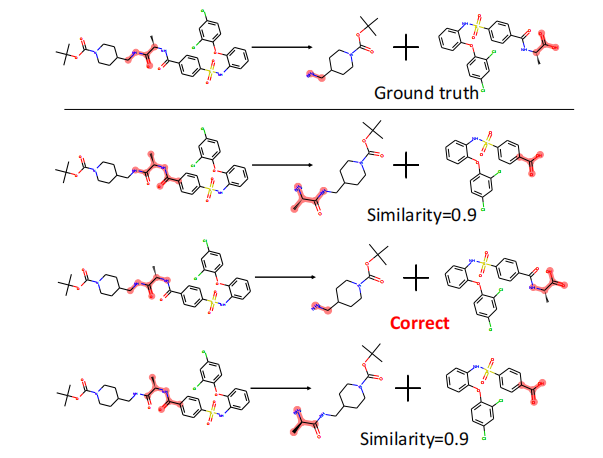

Computational and laboratory experiments take many forms in real scientific practice. For dry experiments, possible tasks range from full pipeline construction to simulation design and multimodule scientific computing; in this benchmark, we adopt a code-completion-based formulation [42], where the model fills in missing components of an existing scientific script rather than generating an entire project from scratch. For wet experiments, laboratory workflows span diverse operational activities, yet we focus on the protocol-design aspect [43], where the model composes a sequence of experimental actions and parameters from a predefined action space.

By constraining dry and wet experiments to code completion and protocol design respectively, we retain core aspects of computational and laboratory reasoning while ensuring reproducibility, controlled variability, and reliable evaluation across models.

Dry experiments emphasize computational problem-solving, reflecting the growing role of AI in automating simulation-driven science. Each task presents the model with incomplete or masked scientific code that encapsulates domain-specific computations, such as molecular dynamics, climate modeling, or numerical solvers in physics [44]. The model must infer the missing logic, reconstruct executable code, and ensure that the resulting program produces correct and efficient outcomes. This task thus evaluates a model’s ability to integrate scientific understanding with code synthesis-testing not only syntactic correctness but also conceptual fidelity to the underlying scientific problem [42].

To better characterize the scope of dry experiments, we categorize representative computational functions commonly encountered across disciplines, including numerical calculation, statistical analysis, simulation, metric calculation, data processing, and predictive modeling, as shown in Table 2. The completion or generation of these functions offers a rigorous measure of how well AI systems can operationalize scientific intent into executable form.

Table 2 | Dry Experiment Function Types: Representative computational functions and their roles across scientific code-completion tasks.

Numerical Calculation Basic mathematical computations required to support physical or chemical modeling.

Processing experimental data using descriptive or inferential statistics to identify trends and distributions.

Running computational simulations (e.g., molecular dynamics, finite element analysis) and filtering results for relevant conditions.

Computing evaluation metrics such as accuracy, error, or performance indicators for validating experiments.

Handling raw data before and after experiments, including normalization, cleaning, and feature extraction.

Applying machine learning methods to categorize, predict, or group experimental results.

In real scientific workflows, dry experiments correspond to the stage of experimental design in computational and simulation-based studies. Following hypothesis formulation, researchers employ virtual experiments to anticipate and evaluate potential outcomes prior to empirical validation, enabling a cost-efficient and theoretically grounded pre-assessment of experimental feasibility.

• Background (B): Information from relevant scientific code, providing context for the dry experiment. • Data Code (D): The data used in the experiment, including any code snippets or predefined inputs. • Main Code (M): The core experimental code where some functions may be masked or missing.

• Functions (F): The missing functions in the main code 𝑀, which the system is tasked with generating or completing.

Task Formulation F = LLM/Agent(B, D, M)

Figure 5 | Dry Experiment Task: Inputs, outputs, and formulation for code-completion based computational studies with masked functions.

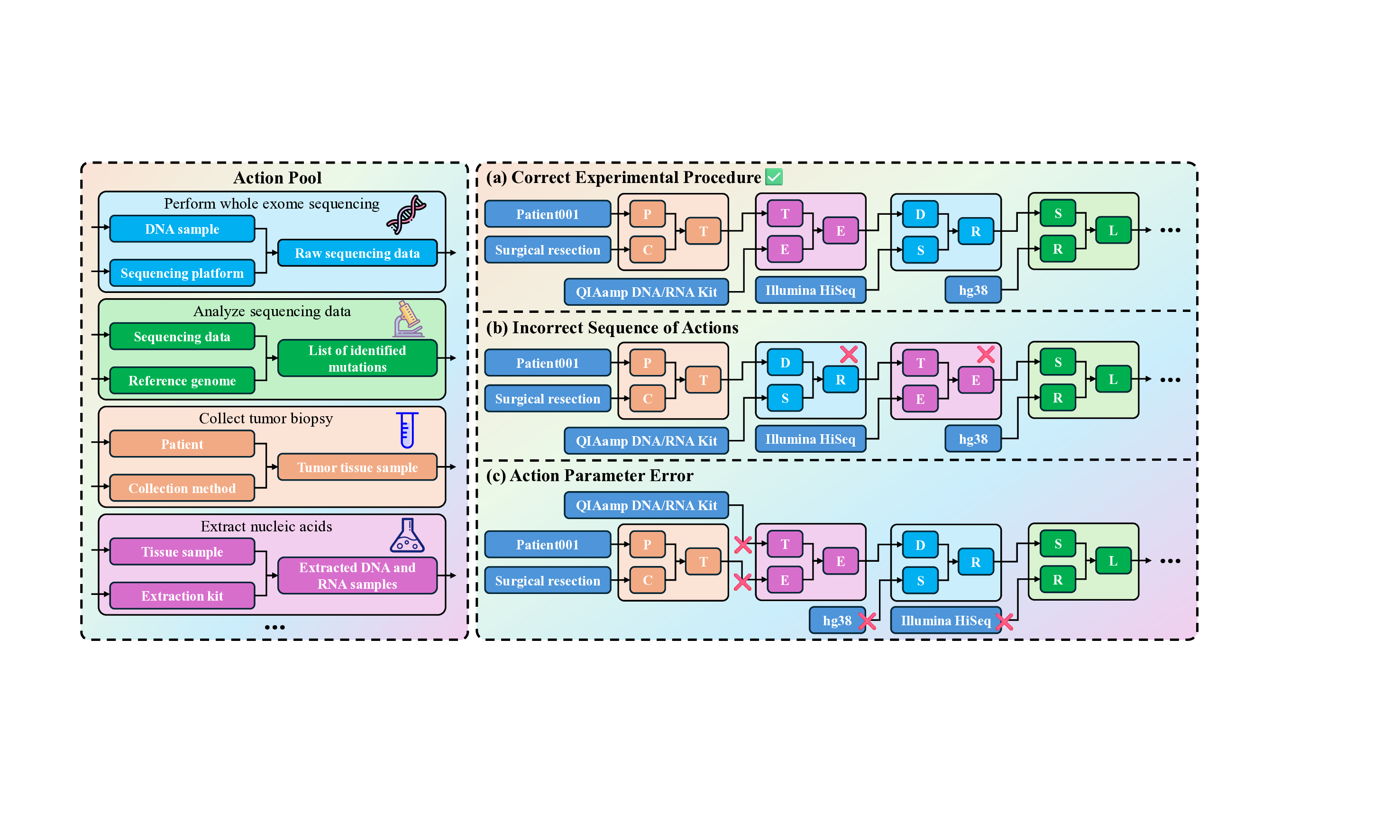

Wet Experiment Wet experiments represent the physical realization of scientific inquiry, encompassing laboratory and field-based procedures that transform theoretical designs into empirical evidence. These tasks simulate the execution phase of real-world experiments, where models are required to plan, organize, and reason through sequences of atomic actions involving materials, instruments, and procedural parameters. Given inputs describing experimental objectives, configurations, and available tools, the model must generate structured, executable protocols that are both accurate and practically feasible. Evaluation considers not only the correctness of individual steps but also their procedural coherence and alignment with established laboratory conventions.

In real scientific workflows, wet experiments correspond to the execution and validation stages of discovery. This is where hypotheses are tested against the physical world, data are collected, and evidence is generated to confirm, refine, or refute prior assumptions. By assessing how effectively AI systems can design and reason through these embodied experimental processes, this task provides a window into their capacity to bridge symbolic understanding with real-world scientific practice.

• Background (B): Information from relevant experimental procedure.

• Action Pool (AP): A predefined set of atomic actions that can be used in the experiment, along with explanations and corresponding input/output definitions.

• Atomic Action Order (AAO): The order in which atomic actions should be executed. • Atomic Action Parameters (AAP): The parameters associated with each atomic action (e.g., reagents, temperature).

AAO, AAP = LLM/Agent(B, AP)

Figure 6 | Wet Experiment Task: Inputs, outputs, and formulation for laboratory protocol planning via atomic actions and parameters.

Experimental reasoning refers to the process of interpreting scientific observations and data to reach justified conclusions. In this benchmark, we focus on data-analysis-oriented reasoning [45], where the model must extract relevant visual or numerical cues from multi-modal sources [46], compare conditions, and identify causal or descriptive patterns. This formulation emphasizes analytical interpretation rather than open-form scientific narrative, enabling reliable assessment while capturing an essential part of empirical scientific reasoning.

We consider five representative modalities as shown in Table 3: a) process images that integrate symbolic and textual information to depict workflows or variable relationships; b) observation images representing raw data captured by instruments such as telescopes, satellites, or microscopes; c) experiment images documenting laboratory setups and procedures; d) simulation images generated by computational models to visualize physical or chemical processes; and e) visualization images such as plots or charts that reveal patterns within structured datasets. Collectively, these modalities reflect the multi-faceted and evidence-driven nature of scientific inquiry. Identifying patterns in telescope images or microscope slides.

Attribute Understanding Requires disciplinary background to interpret key features and scientific attributes.

Recognizing crystalline structures in materials science images.

Comparative Reasoning Integrates and contrasts information across multiple images, often crossdomain.

Comparing climate model simulations with satellite observations.

Goes beyond correlation to infer mechanisms or propose hypotheses.

Inferring causal pathways in gene expression from multi-modal experimental data.

requires reasoning or analysis.

• Reasoning (R): The specific steps in the reasoning process, including calculation, thinking, analysis, etc.. • Answer (A): The conclusion drawn from analyzing the experimental data, answering the specified question or hypothesis.

R, A = LLM/Agent(MEI, Q)

Figure 7 | Experimental Reasoning Task: Inputs, outputs, and formulation for multi-modal analysis with step-by-step reasoning and final answers.

To align with the scientific characteristics of each task, we have designed multi-dimensional evaluation metrics for every task. This approach avoids a one-size-fits-all binary judgment and instead provides a more fine-grained assessment.

The Scientific Deep Research task draws inspiration from AI’s deep research paradigms [47,48,49,50,51] while incorporating methodologies from meta-analysis in the scientific domain. The former emphasizes multi-step reasoning, where solving a problem often requires iterative searches, calculations, and inferences; the correctness of each step directly impacts the accuracy of the final answer. The latter focuses on systematically extracting and synthesizing data from literature, requiring highly precise results. Accordingly, our metrics capture both step-by-step reasoning fidelity and final answer accuracy.

Exact Match (EM): Since the Scientific Deep Research tasks are designed to have short, unique, and easily verifiable answers, we use exact match as a hard metric to assess whether the model’s final answer is correct. The model receives a score of 1 if the output exactly matches the reference answer, and 0 otherwise.

Step-Level Accuracy (SLA): Models are required to produce step-by-step solutions. We employ an LLM-based judge to compare each model-generated step against the reference solution steps. For each step, the judge determines whether it is correct and provides reasoning. This fine-grained evaluation avoids binary correctness judgments for the entire solution, allowing precise assessment of reasoning accuracy at each inference step. The metric is computed as the proportion of steps correctly solved relative to the total number of steps. The score is calculated as SLA = Number of correct reasoning steps Total number of reasoning steps .

To evaluate the open-ended nature of idea generation, we adopt a hybrid framework that integrates both subjective and objective metrics. We assess each idea along four dimensions-effectiveness, novelty, detailedness, and feasibility-which together characterize an idea’s scientific quality, creativity, and executability [37,52].

Subjective Evaluation via LLM Judges. For subjective scoring, we perform pairwise comparisons between model-generated ideas and expert-written reference ideas. For each of the four dimensions, an LLM judge selects which idea is superior. To ensure fairness and robustness, we employ three different LLM judges, each casting two independent votes, resulting in a total of six votes per dimension. The pairwise win rate against the reference idea is then used as the subjective component of the score for each dimension.

Objective Evaluation via Computable Metrics. In addition to subjective judgments, we design dimension-specific computational metrics that capture structured properties of the ideas.

For each reference idea, human experts extract its 3-5 most essential keywords. We compute the hit rate of these keywords in the model-generated idea, allowing semantic matches to avoid underestimating effectiveness. The final effectiveness score is the average of the keyword hit rate and the LLM-judge win rate:

.

We measure novelty by computing the dissimilarity between the model-generated idea and prior related work. Lower similarity indicates that the model proposes ideas not present in existing literature and therefore exhibits higher creativity. .

For each research direction, domain experts provide a standardized implementation graph containing the essential nodes and their execution order. We extract an implementation graph from each model-generated idea and compute its similarity to the expert template. A low similarity indicates that the proposed idea does not align with accepted solution workflows and is therefore infeasible. The final feasibility score is:

Taken together, the hybrid subjective-objective design provides a robust, interpretable, and comprehensive assessment of LLMs’ scientific idea generation capabilities across creativity, structural clarity, and practical executability.

Dry Experiment Dry experiments focus on code generation task. Specifically, each problem includes background information, data code, and main code with certain functions masked. The model is tasked with completing the missing functions. Each problem contains 5 unit tests. Our metrics capture both correctness and execution behavior of the generated code [53]. the number of discordant pairs between the sequences. For sequences of length 𝑛, the score is computed as:

,

where 𝑛(𝑛-1)

is the maximum possible number of inversions. By definition, SS = 1 indicates that the sequences are identical, while SS = 0 indicates maximal disorder relative to the reference sequence.

Parameter Accuracy (PA): This metric measures the correctness of input parameters for each atomic action compared to the reference, including reagent types, concentrations, volumes, or other domain-specific parameters. The score is calculated as the proportion of correctly specified parameters across all actions: PA = Number of correctly specified parameters Total number of parameters .

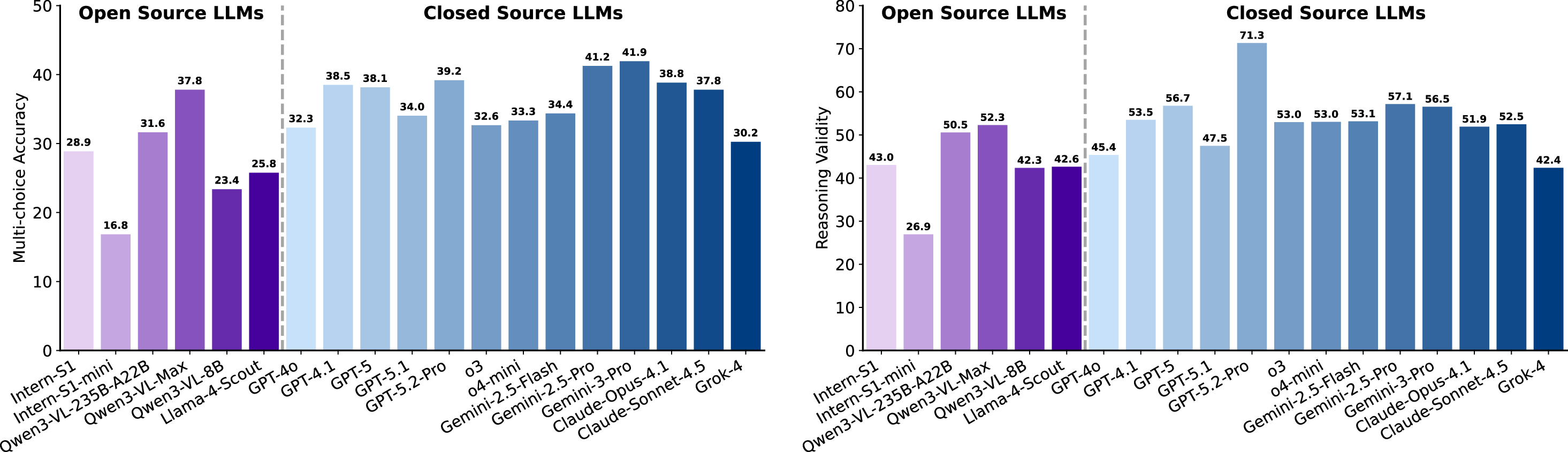

The Experimental Reasoning task assesses the multi-modal scientific reasoning capabilities of LLMs and agents. Specifically, given several images and a corresponding question, the model is required to select the correct option from no fewer than 10 candidates. For evaluation, the correctness of the final answer and the validity of intermediate reasoning are equally critical. Therefore, two evaluation metrics are adopted, as detailed below.

Multi-choice Accuracy (MCA): Given several options, the model receives a score of 1 if the selected option exactly matches the reference answer, and 0 otherwise. The final score of MCA is the average of all individual scores across all test samples. This metric directly quantifies the model’s ability to pinpoint the correct solution from a large candidate pool, serving as a foundational measure of its end-to-end scientific reasoning accuracy in the multi-modal task.

Reasoning Validity (RV): Models are required to generate step-by-step logical reasoning to justify their selected answers. An LLM-based judge is utilized to assess the model-generated reasoning against a reference reasoning. For each test sample, the LLM judge assigns a validity score ranging from 0 (completely invalid, contradictory, or irrelevant) to 10 (fully rigorous, logically coherent, and perfectly aligned with the reference reasoning), accompanied by justifications for the assigned score. This fine-grained scoring paradigm circumvents the limitations of binary correctness assessments, enabling precise quantification of reasoning quality, including the validity of premises, logical transitions, and alignment with scientific principles. The final RV score is computed as the mean of individual sample scores across the entire test set, reflecting the model’s overall capability to perform interpretable and reliable scientific reasoning.

Raw Corpus Collection In this stage, we conducted multiple discussions with experts from diverse scientific disciplines, drawing from both the 125 important scientific questions published in Science, and the prominent research directions in various disciplines with significant scientific impact. Ultimately, we curated 75 research directions spanning ten scientific domains, as shown in Figure 8. Please refer to Appendix A.2 for a complete list of research directions.

Subsequently, we collected raw data provided by experts and researchers, primarily consisting of scientific texts and images across the various disciplines. The texts mainly cover knowledge introduction, methodological design, experimental procedures, and data analysis. The images include experiment figures, data visualizations, and observational images, each accompanied by detailed descriptions.

In addition, these experts and researchers will provide seed questions and annotation requirements for annotation, which provide initial examples for the subsequent annotation process, as illustrated in Figure 2 (G).

After gathering the raw data, we recruited over 100 Master’s and PhD holders from different disciplines to construct benchmark questions according to the task definitions. Annotators first analyzed the collected texts and images, and then created questions according to annotation requirements and seed questions. Several rules were applied to ensure scientific validity and authenticity. Specifically, annotators were required to reference the original data source and paragraph for each question, ensuring traceability to scientist-provided data. Furthermore, all questions are constructed by at least two annotators, one of whom is responsible for generating complex draft questions, and the other is responsible for refining them, as shown in Figure 2 (G).

During question construction, experts continuously reviewed the generated questions. Each question was immediately submitted to the relevant expert for evaluation, who assessed its scientific value.

For instance, a question with an experiment configuration that lacks general applicability would be deemed scientifically invalid. Experts provided feedback to annotators, who then revised the questions accordingly, ensuring that the constructed questions remain aligned with the perspectives and standards of domain scientists.

Data Cleaning Once all questions were constructed, we applied three layers of data cleaning: 1.

Rule-based cleaning: Questions that did not meet task-specific criteria were removed. For example, for Scientific Deep Research, steps must be short sentences forming a list, each representing one step; for Wet Experiments, each action must exist in the predefined action pool. 2. Model-based cleaning: Large language models were used to detect and remove questions with semantic errors or potential logical inconsistencies. 3. Expert quality check: All questions were reviewed by the original data-providing scientists, removing incomplete questions, questions with non-unique answers, or questions whose research direction did not align with the source data. For Dry Experiments, Python environments were used to test all code snippets to ensure executability.

After data cleaning, we filtered questions based on difficulty using mainstream LLMs. We evaluated each question with six high-performance models (e.g., GPT-5 [54], Gemini-2.5-Pro [5], DeepSeek-R1 [55], Kimi-k2 [56]) under a setup allowing web search and deep-reasoning modes. Questions that more than half of the models could correctly answer were removed. This process ensures that the benchmark remains highly challenging.

Through these four steps, we guarantee that all benchmark questions are derived from authentic scientific data, aligned with domain scientists’ judgment of scientific value, and maintain both high quality and high challenge.

After the data construction process, we obtained the complete SGI- Simulation Images, and Visualization Images, summarized in Table 3 and visualized in Figure 9 (f). Moreover, based on the type of reasoning required, questions are further categorized into Signal Perception, Attribute Understanding, Comparative Reasoning, and Causal Reasoning, as detailed in Table 4, with distributions shown in Figure 9 (g).

These fine-grained categorizations by discipline and task type facilitate a detailed analysis of the limitations of evaluated LLMs and agents across scientific domains and research tasks. Such insights provide clear directions for advancing AI-assisted scientific discovery.

Given the inherent complexity of scientific discovery, evaluating the performance of LLMs and agents in this domain presents formidable challenges. Rather than merely employing LLMs as evaluators, we develope a comprehensive, agent-based evaluation framework augmented with diverse capabilities (e.g., web search, Python interpreter, file reader, PDF parser, metric-specific Python functions [57]) to ensure rigorous, accurate, and scalable evaluations. As illustrated in Figure 10, this framework is structured into four interconnected stages: Question Selection, Metric Customization, Predict & Eval, and Report Generation, each orchestrated by specialized agents to address distinct facets of the evaluation workflow.

The Question Selection stage is managed by a dedicated questioning agent, which interprets user queries to retrieve relevant questions from the SGI-Bench question bank. The agent filters questions according to multiple criteria, including disciplinary domain, task category, and evaluation intent specified in the input query. In scenarios where no user query is provided, the agent defaults to systematically selecting all questions from the SGI-Bench, thereby ensuring comprehensive coverage across all scientific tasks. This stage effectively defines the evaluation scope by specifying the precise set of problems that subsequent stages will assess.

• User Query (Q): Any content input by users for obtaining relevant information, which can be in various forms such as text, keywords, or questions. • SGI-Bench Data (D): All constructed datasets in SGI-Bench, each of which is associated with a specific discipline and corresponding research area. • K-value (K): A positive integer indicating the number of most relevant items to select from the SGI-Bench Data based on the User Query.

• Selected Indices (SI): The selected indices for locating and retrieving the target data.

In the metric customization stage, a metric customization agent first dynamically generates novel evaluation metrics based on user queries and selected questions. The agent parses the evaluation intent from user input to formalize customized metric instructions with advanced tools like web search and PDF parser, enabling flexible prioritization of metrics or integration of novel evaluation dimensions. Then, the customized metrics will be aggregated with predefined scientist-aligned metrics given different question types, as described in Section 2.2, to form the final metrics for evaluation. By synergizing pre-defined and user-customized metrics, this stage ensures the framework aligns with both standardized benchmarks and domain-specific demands.

• User Query (UQ): Any content input by users for obtaining relevant information, which can be in various forms such as text, keywords, or questions. • SGI-Bench Data (D): All constructed datasets in SGI-Bench, each of which is associated with a specific discipline and corresponding research area. • Selected Indices (SI): The selected indices for locating and retrieving the target data. • Tool Pool(T): A set of pre-configured tools for agents to call, including web search, PDF parser, Python Interpreter, etc. • Metric Pool(M): A set of pre-defined task-specific metrics presented in Section 2.2.

• Metrics for Evaluation (ME): Generated novel metrics based on the user query.

The predict & eval stage leverages a tool pool that includes utilities like web search, PDF parser, and Python interpreter to first execute inference for target LLMs or agents on the questions selected in the first stage. Subsequently, a dedicated Science Eval Agent (SGI-Bench Agent) applies the metrics finalized in the second stage to score the inference results. For each score, the agent generates a ratio-nale grounded in reference answers, question context, and supplementary information retrieved via tools if necessary, thereby ensuring transparency and reproducibility. By integrating tool-augmented inference with systematic, metric-driven scoring, this stage effectively addresses the multi-dimensional and complex nature of scientific reasoning assessment.

• SGI-Bench Data (D): All constructed datasets in SGI-Bench, each of which is associated with a specific discipline and corresponding research area. • Selected Indices (SI): The selected indices for locating and retrieving the target data. • Responses (R): Generated responses by the evaluation target in the Testbed.

• Tool Pool(T): A set of pre-configured tools for agents to call, including web search, PDF parser, Python Interpreter, etc. • Metrics for Evaluation (ME): Generated novel metrics based on the user query.

• Score (S): A single integer score from 0-10, where 10 means the response is fully correct compared to the answer. Higher scores indicate the Prediction is better, and lower scores indicate it is worse. • Rationale (RN): A brief explanation of why the response is correct or incorrect with respect to accuracy, completeness, clarity, and supporting evidence.

The report generation stage is orchestrated by a dedicated reporting agent, which aggregates the user evaluation intents, finalized metric specifications, and the results produced during the Predict & Eval stage. The agent then compiles a comprehensive report that both visualizes and quantifies the performance of different LLMs and agents across the selected questions and metrics. Beyond summarizing raw results, the report contextualizes the findings within the broader landscape of scientific discovery capabilities, thereby enabling users to extract actionable insights and make informed decisions efficiently.

• Score List(SL): A list of integers score from 0-10, where 10 means the response is fully correct compared to the answer. Higher scores indicate the Prediction is better, and lower scores indicate it is worse. • Rationale List(RNL): A list of explanations of why the response is correct or incorrect with respect to accuracy, completeness, clarity, and supporting evidence. • User-customized Metric (UM): Generated novel metrics based on the user query.

• Report (R): A comprehensive final evaluation report that demonstrates the scientific discovery capabilities of different LLMs and agents.

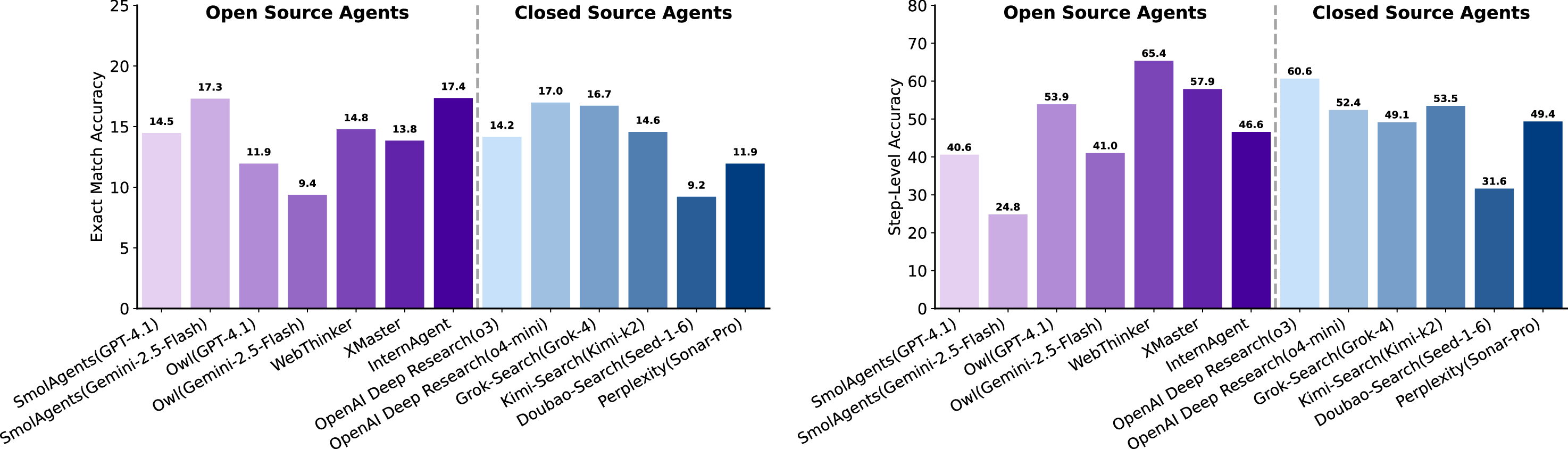

To comprehensively evaluate different models throughout the scientific discovery workflow, we performed quantitative assessments across diverse LLMs and agents using scientist-aligned metrics.

• For open-weight LLMs, we evaluated DeepSeek-V3.2 [58], DeepSeek-R1 [55], Intern-S1 and Intern-S1-mini [59], Kimi-k2 [56], Qwen3-VL-235B-A22B [60], Qwen3-235B-A22B, Qwen3-Max, and Qwen3-8B [61], and Llama-4-Scout [62]. • For closed-weight LLMs, we assessed GPT-4o [63], GPT-4.1 [64], GPT-5 [54], GPT-5.1 [65], GPT-5.2-Pro [66], o3 and o4-mini [67], Gemini-2.5-Flash and Gemini-2.5-Pro [5], Gemini-3-Pro [68], Claude-Opus-4.1 [69], Claude-Sonnet-4.5 [70], Grok-3 [71], and Grok-4 [72]. • For open-source agents, we tested SmolAgents(GPT-4.1) and SmolAgents(Gemini-2.5-Flash) [57], Owl(GPT-4.1) and Owl(Gemini-2.5-Flash) [73], WebThinker [74], XMaster [75],

and InternAgent [76]. • For closed-source agents, we evaluated OpenAI DeepResearch(o3) and OpenAI DeepResearch(o4mini) [48], Kimi-Search(Kimi-k2) [50], Doubao-Search(Seed-1-6), Grok-Search(Grok-4) [51], and Perplexity(Sonar-Pro) [49].

For benchmarking consistency, we set the temperature of all configurable models to 0 to minimize randomness and used a standard zero-shot, task-specific prompt template across all tasks. Taken together, these patterns validate our SGI framing: contemporary models possess fragments of the Deliberation-Conception-Action-Perception cycle but fail to integrate them into a coherent, workflow-faithful intelligence-pointing to the need for meta-analytic retrieval with numerical rigor, planning-aware conception, and procedure-level consistency constraints.

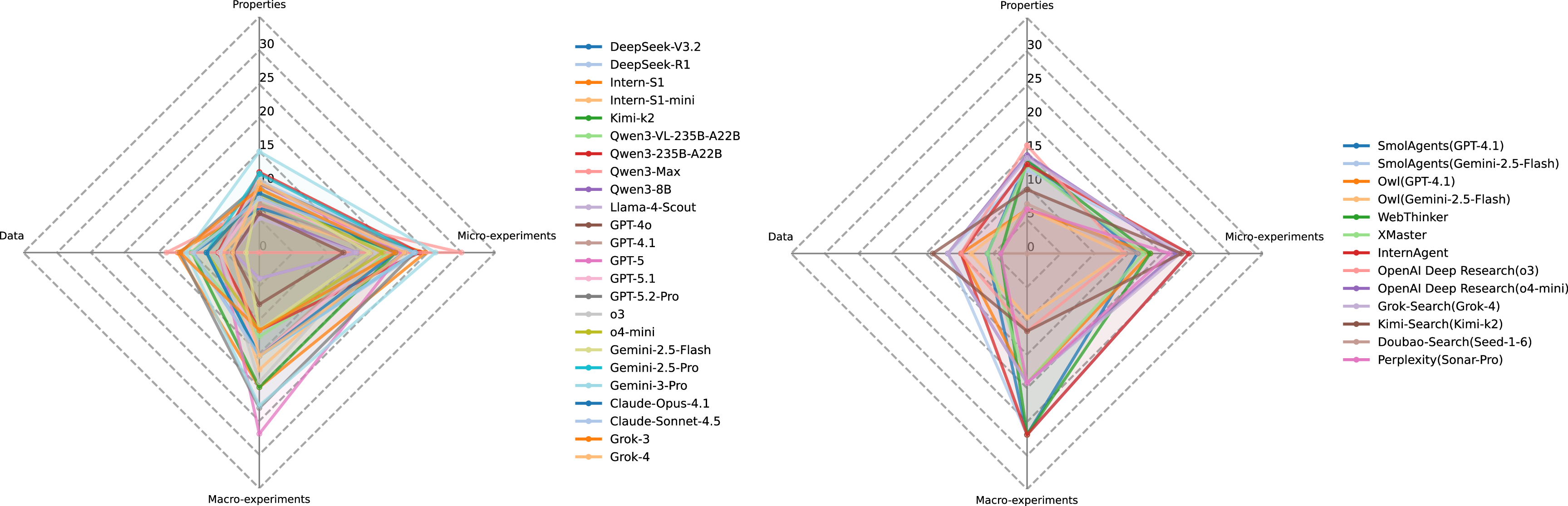

The results for LLMs and agents are presented in Figs. 12

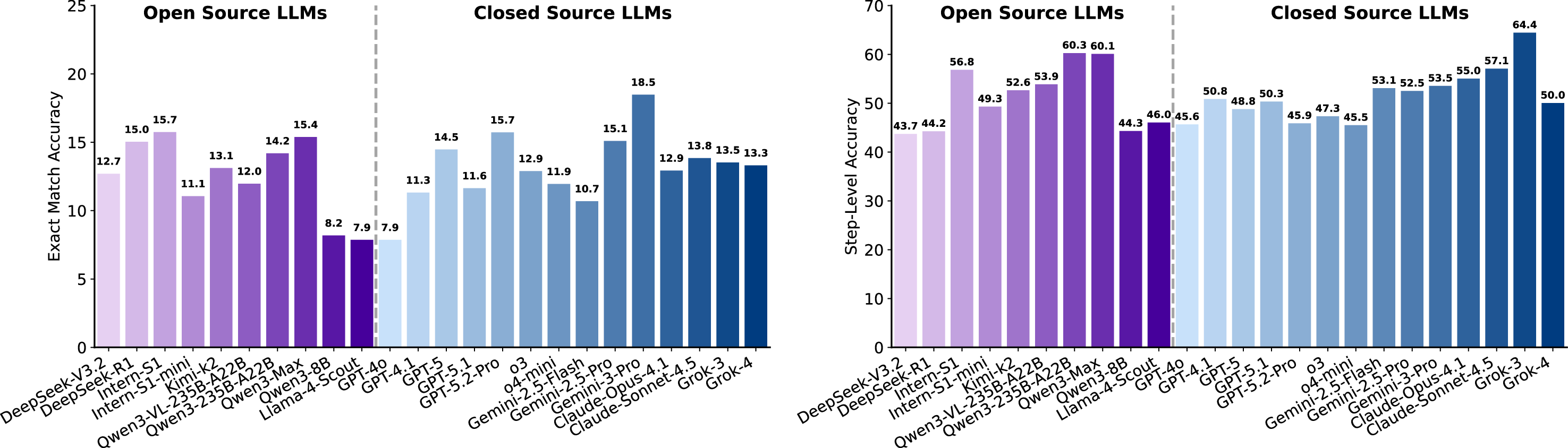

Grok-3 SLA substantially exceeds EM across nearly all systems. Multiple systems, including several agents-achieve SLA above 50%, with the best around 65%. This disparity suggests that models frequently produce partially correct or locally consistent reasoning steps but struggle to maintain coherence and correctness across the full reasoning chain. Such behavior underscores the intrinsic difficulty of end-to-end scientific reasoning and the importance of step-wise decomposition for improving task success.

Newer large-scale LLMs do not universally outperform predecessor models. For example, Grok-4 exhibits lower EM and SLA than Grok-3 on this benchmark, suggesting that large-scale training may introduce regressions or reduce retention of specialized scientific knowledge. These results collectively Question: The experimental methodology for studying chaotic hysteresis in Chua’s circuit is employs a precision Chua’s circuit setup with calibrated instrumentation to investigate chaotic hysteresis through step-by-step DC voltage variation and frequency-dependent triangular wave analysis, quantifying hysteresis loops and identifying critical frequency thresholds via phase space trajectory monitoring and time series bifurcation analysis. In the Chua circuit experiment, what are the calculated time constants (in μs) for the RC networks formed by a 10.2 nF capacitor C1 and the equivalent resistance, the peak-to-peak voltage (in V) range of the hysteresis loop at 0.01 Hz driving frequency, and the critical frequency (in Hz) where chaotic behavior ceases? Output the results in two decimal places, one decimal place, and integer format respectively, separated by commas.

/mnt/shared-storage-user/xuwanghan/projects/SuperSFE/SuperSFE/data/v7-3-深度搜索/ 物理/7_电路系统中的混沌行为/1/deep_research.json

Step 1: Find paper Experimental observation of chaotic hysteresis in Chua’s circuit driven by slow voltage forcing.

Step 2: Identify RC network components from experimental setup: C1=10.2 nF, R1=219Ω. Calculate time constant: τ=R1×C1=219×10.2×10-9=2.2338μs≈2.23μs.

Step 3: Voltage range determination: At 0.01 Hz triangular forcing, peak-to-peak voltage ΔV_T=3.2 V measured from hysteresis loop width in experimental phase portraits.

Step 4: Critical frequency identification: “For f>10Hz the hysteresis phenomenon practically disappears” confirmed through frequency sweep experiments showing ΔV_T reduction from 3.2V (0.01Hz) to 0V (10Hz).

Step 5: Validate measurement procedures: Hysteresis loops are measured by “changing DC voltage very slowly and step by step” while monitoring attractor transitions between single scroll and double scroll regimes.

Step 6: Confirm data analysis techniques: Phase portraits and time series analysis confirm chaotic behavior through “bifurcations and dynamic attractor folding”.

Step Most models exhibit substantially lower performance on the Data and Properties tasks, but somewhat better-though still modestly-on Micro-and Macro-experiment tasks. Based on the focus of each question, we categorize the tasks into four types: Data, Properties, Micro-experiments, and Macro-experiments (Table 1). Figure 14 summarizes the performance of LLMs and agents across these categories. Notably, performance across all four categories rarely exceeds 30% (with only a few Macro cases slightly above), underscoring the intrinsic difficulty of scientific deep research. This disparity can be attributed to the nature of the information required. Data-and property-related questions often rely on detailed numerical specifications or contextual descriptions scattered across disparate sources in the literature, demanding precise retrieval, cross-referencing, and aggregation. In contrast, Micro-and Macro-experiment tasks tend to provide more structured protocols or clearer experimental outcomes, enabling LLMs and agents to reason with fewer retrieval uncertainties.

In summary, the relatively stronger model performance on experiment-oriented tasks suggests that recent advances in LLM pretraining and instruction tuning have enhanced models’ abilities to process structured procedures and numerical patterns. Nevertheless, the consistently low scores across all categories indicate that contemporary LLMs, even when augmented with tool-based agents, remain far from mastering the breadth and depth of reasoning required for robust scientific deep research.

Figure 15 illustrates the evaluation pipeline for Idea Generation in SGI-Bench, and more experimental details can be found in the section 2.2.2. Table 6 shows the quantitative experimental results of idea generation, including effectiveness, novelty, detailedness, and feasibility. We could see that GPT-5 achieves the best average performance, and achieves the best performance in three aspects only excluding the feasibility. Moreover, across models, a clear pattern emerges: Novelty is generally high, especially among closed-source systems (e.g., o3 73.74, GPT-5 76.08). This indicates that modern LLMs possess a robust capacity for generating conceptually novel scientific ideas. Such behavior aligns with the growing empirical use of LLMs as inspiration engines for scientific hypothesis generation and exploratory research.

To rigorously analyze and experimentally validate the two-scans phaseless spherical near-field technique, quantifying the impact of measurement parameters and AUT characteristics, and to synthesize practical guidelines for accurate phase retrieval and radiation pattern reconstruction without phase information.

Formulate a differentiable spherical near-field forward operator from equivalent currents to complex field on arbitrary spheres, including AUT offsets and asymmetries.

1

Integrate the forward operator and phase prior into a physics-informed unrolled optimizer (e.g., unrolled Wirtinger / gradient descent) for amplitude-only data.

Embed measurement-configuration parameters (sphere radii, angular sampling, AUT offset) as optimizable or sweepable variables within the framework.

Design a Bayesian deep phase prior (e.g., conditional generative model) trained on synthetic AUT current/field libraries spanning high-gain, asymmetric, and offset antennas. Mechanistically, this strength likely stems from their broad pretraining over heterogeneous scientific corpora, which enables them to recombine distant concepts across domains, as well as their ability to internalize high-level research patterns (problem-method-evaluation triples

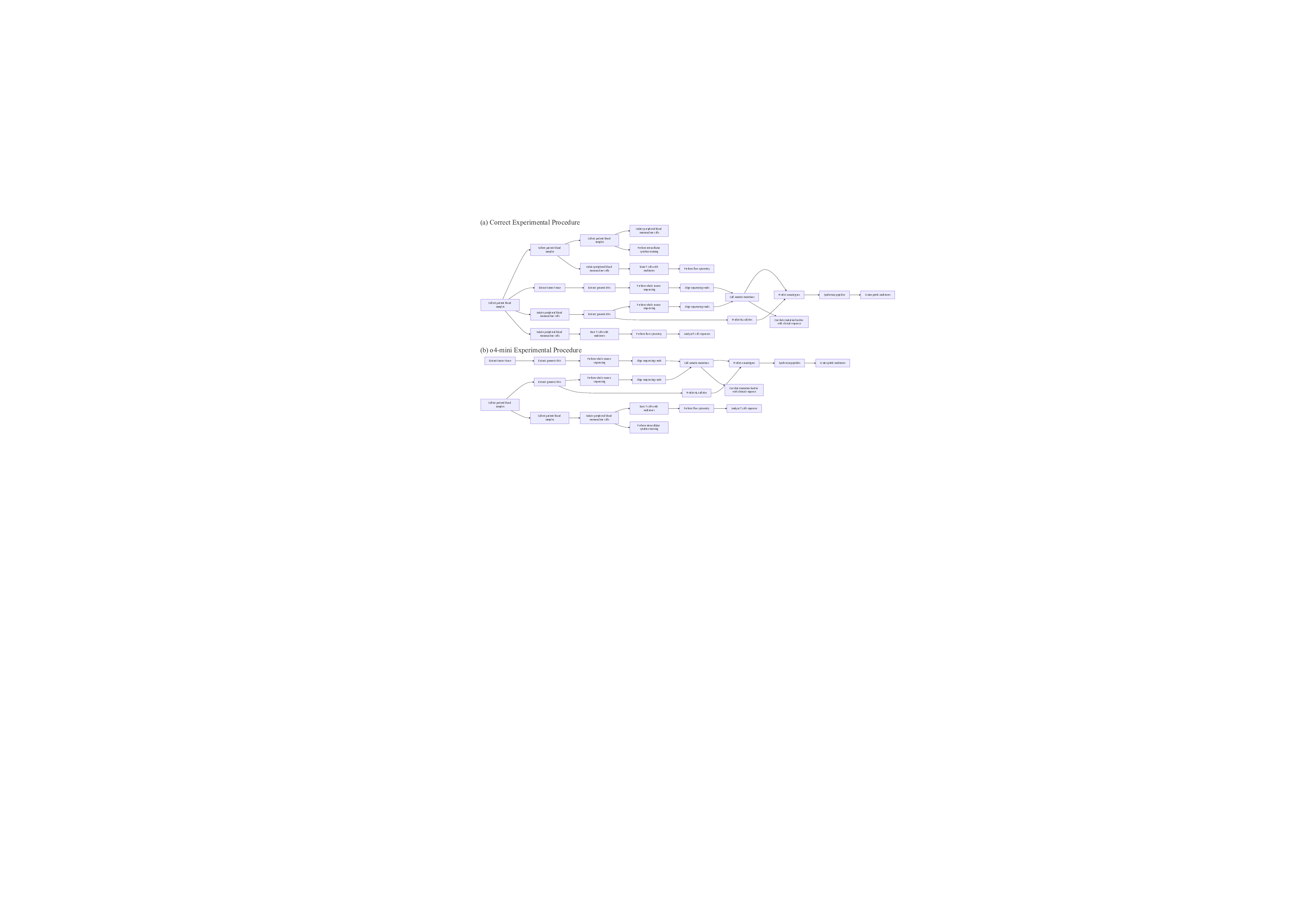

Experiments form the critical bridge between idea generation and scientific reasoning, providing the most direct avenue for validating hypotheses and uncovering new phenomena. Within SGI-Bench, we evaluate two complementary forms of experiments: dry experiments, which involve computational analyses or simulations, and wet experiments, which require laboratory procedures and operational planning. Across both categories, current AI models exhibit substantial limitations, revealing a persistent gap between linguistic fluency and experimentally actionable competence.

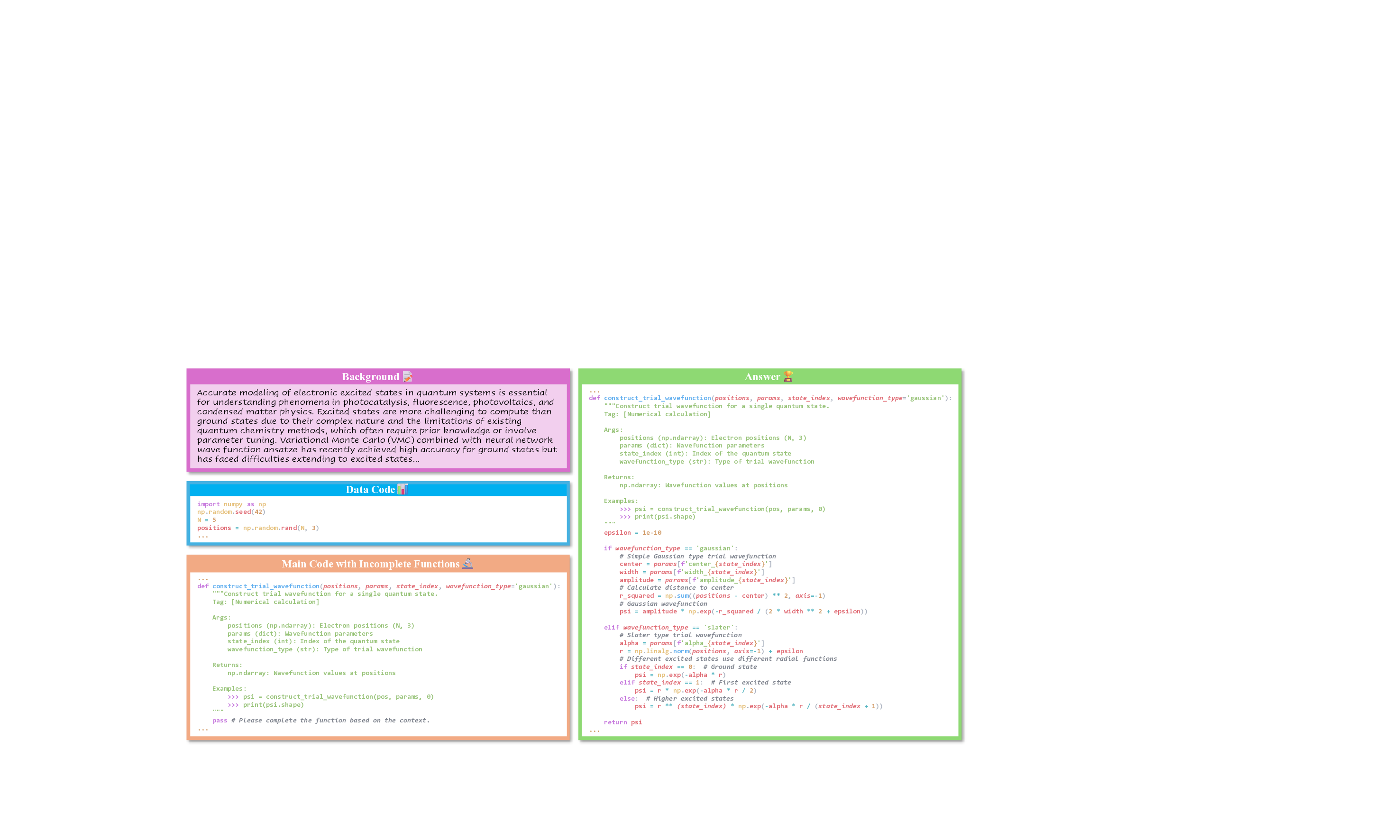

Accurate modeling of electronic excited states in quantum systems is essential for understanding phenomena in photocatalysis, fluorescence, photovoltaics, and condensed matter physics. Excited states are more challenging to compute than ground states due to their complex nature and the limitations of existing quantum chemistry methods, which often require prior knowledge or involve parameter tuning. Variational Monte Carlo (VMC) combined with neural network wave function ansatze has recently achieved high accuracy for ground states but has faced difficulties extending to excited states…

As introduced in Section 2.1.3, each dry experiment contains three components: a description of scientific background, a complete data-construction script, and an analysis script with masked functions. The model must infer and complete these missing functions using contextual understanding. For fairness and structural clarity, function headers, including names, signatures, and functional descriptions, are preserved, as shown in Figure 16. This setup isolates the model’s ability to infer algorithmic logic rather than boilerplate structure. Table 7 summarizes three metrics defined in Section 2.2.3: PassAll@k, Average Execution Time (AET), and Smooth Execution Rate (SER). Here, PassAll@k denotes passing at least 𝑘 out of five unit tests per problem. Under the lenient criterion (𝑘=1), the best models achieve a PassAll@1 score of 42.07%, whereas the strictest requirement (𝑘=5) reduces performance to 36.64%. These results underscore that scientific code completion remains a significant bottleneck, even for frontier LLMs. Notably, closed-source models generally achieve higher PassAll@k than leading open-source models, though the advantage is modest and distributions overlap, suggesting that scientific code synthesis in dry experiments remains underdeveloped across architectures.

High execution rates do not guarantee correctness. The SER metric captures whether the generated code executes without error, independent of correctness. While many top models achieve high SER values (>90%), performance varies widely across systems; several models are substantially below this threshold (e.g., Gemini-2.5-Flash/Pro, Qwen3-8B, Llama-4-Scout, GPT-5, GPT-4o), indicating nontrivial robustness gaps. This suggests that basic structural and API-level reasoning has matured for some models; however, the persistent gap between SER and accuracy metrics highlights that structural validity is far easier than algorithmic correctness in scientific contexts.

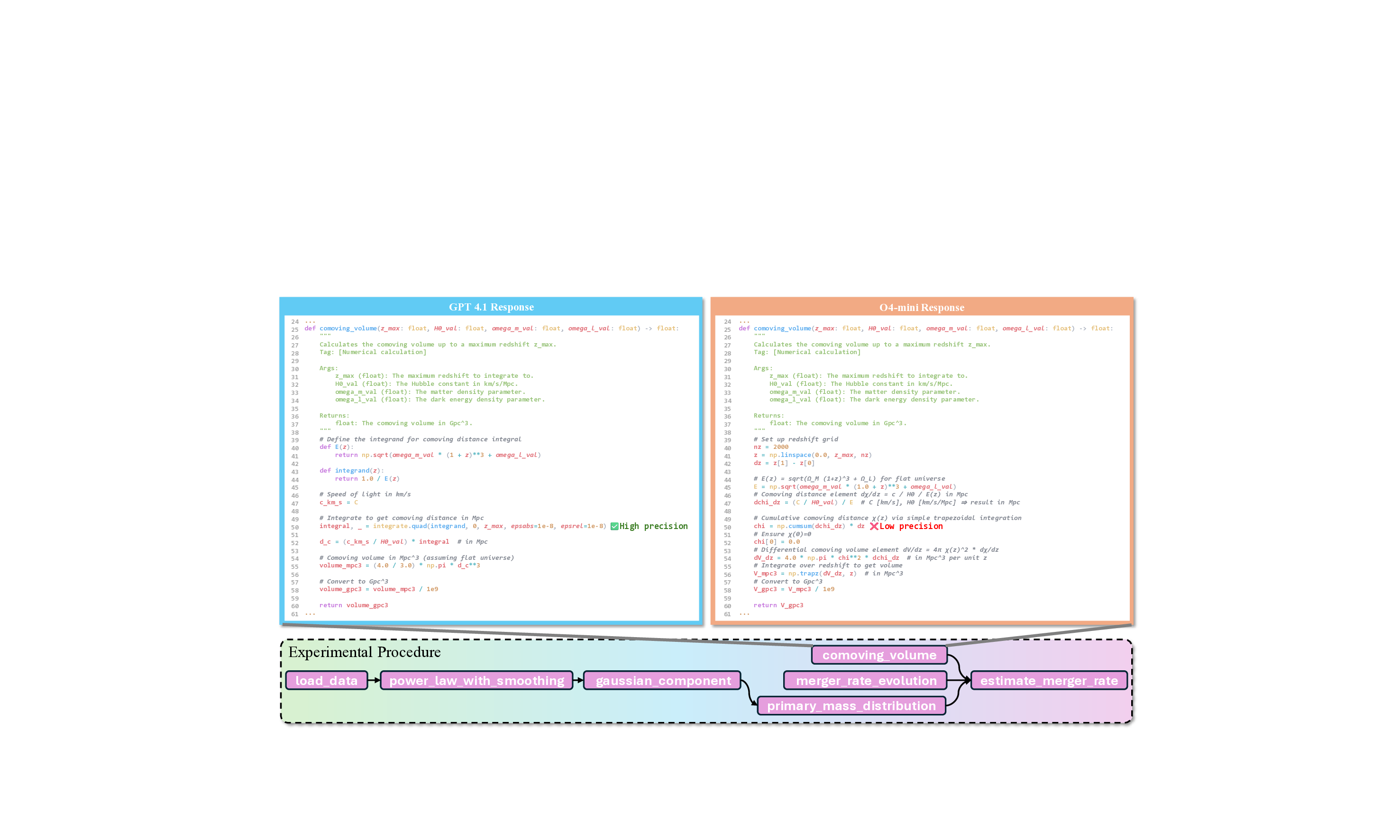

Numerical and simulation functions are the most challenging. Figure 17 breaks down PassAll@5 across functional types. Models perform relatively well on Data Processing and Predictive Modeling, where multiple valid implementations exist and errors are less amplified. In contrast, Numerical Calculation and simulation-oriented functions prove substantially more difficult. These tasks typically require precise numerical stability, accurate discretization, or careful handling of domain-specific Model PassAll@5(%)↑ PassAll@3(%)↑ PassAll@1(%)↑ AET(s)↓ SER(%)↑ constraints, all of which amplify small reasoning inconsistencies. This pattern reveals a striking asymmetry: models exhibit reasonable flexibility in tasks with diverse valid outputs but struggle with tasks requiring exact numerical fidelity.

Methodological choices critically affect outcomes. The case shown in Figure 18 illustrates this issue in an astronomical dry experiment involving the computation of gravitational-wave observables from LIGO/Virgo-like detectors. The o4-mini model employs a naïve numerical integration via np.cumsum, effectively using a forward Euler approximation for

which introduces substantial cumulative error when the discretization is coarse. In contrast, GPT-4.1 correctly adopts scipy.integrate.quad, leveraging adaptive integration schemes that preserve numerical precision. Because errors in 𝜒(𝑧) propagate directly to the comoving volume element

the flawed integration strategy in o4-mini leads to a significant deviation in the final volume estimate 𝑉 Gpc 3 . This example highlights a broader challenge: LLMs often fail to capture the numerical sensitivity and methodological nuance essential for scientific computation.

Overall, these findings reveal that while current models can generate syntactically valid code with high reliability, their deeper limitations stem from (i) incomplete numerical reasoning, (ii) superficial understanding of scientific algorithms, and (iii) the inability to select appropriate computational strategies under domain constraints. AI-assisted scientific experimentation thus remains a demanding frontier, requiring future models to incorporate domain-aware numerical reasoning, fine-grained algorithmic priors, and training signals beyond natural-language supervision.

For wet experiments, we provide models with an action pool containing standardized experimental operations and detailed descriptions. Given the experimental context, the model is required to synthesize a complete workflow, including both the selection and ordering of actions as well as all associated parameters (Figure 19). As illustrated in the figure, the model outputs typically exhibit two major categories of errors: (i) incorrect ordering of experimental steps and (ii) inaccurate or inconsistent parameter specification.

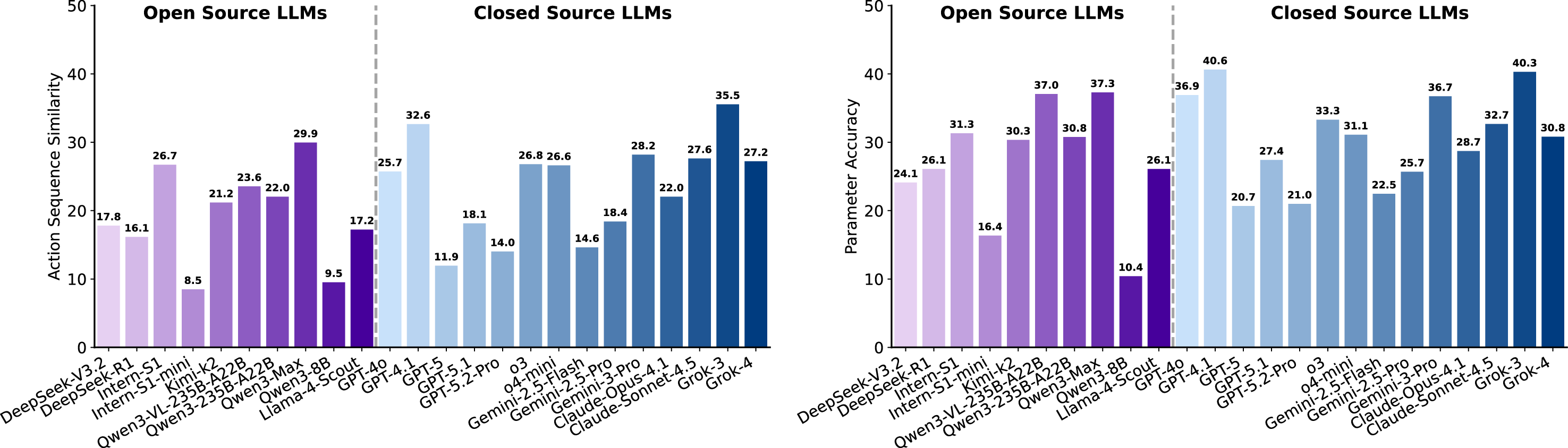

Collect tumor biopsy Wet experiments reasoning remains brittle. Figure 20 summarizes performance in terms of sequence similarity (SS) and parameter accuracy (PA). For SS, closed-source models in general achieve higher scores than open-source ones (with the best closed-source model around 35.5 versus the best open-source below 30), yet SS remains uniformly low across all systems. In contrast, PA exhibits a mixed pattern: although the top result is obtained by a closed-source model (around 40.6), several open-source models are competitive, and some closed-source models drop markedly (e.g., near 20.7). PA appears slightly more optimistic also since permutation-equivalent parameter groups are treated as identical (e.g., ⟨action 1⟩(𝐵, 𝐶) and ⟨action 1⟩(𝑋, 𝑌 ) are identical when 𝐵=𝑋 and 𝐶=𝑌 ), but both families still achieve only modest scores. Across outputs, errors recur in three patterns: insertion of unnecessary steps, omission of essential steps, and incorrect ordering of valid steps.

Temporal and branch-aware planning is often broken. Figure 21 presents an experiment examining how tumor mutational burden and neoantigen load influence the efficacy of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. The ground-truth workflow (Figure 21 a) features a deeply branched structure with precisely coordinated timing and sample-handling procedures. In contrast, the workflow generated by o4-mini is substantially simplified and deviates from several core principles of experimental design. First, the model collapses longitudinal sampling into a single blood draw and does not distinguish time windows, precluding any meaningful reconstruction of T-cell dynamics. Second, PBMC isolation is executed only once rather than per time point, causing misalignment with downstream staining and flow cytometry. Functional assays (e.g., intracellular cytokine staining) are performed on a single PBMC aliquot without branching by time point or antigenic stimulation, and flow cytometry is likewise conducted only once, failing to capture temporal variation. Finally, the blood-sample branch conflates genomic and immunophenotyping workflows: “Extract genomic DNA” is executed in parallel with PBMC isolation and downstream immunology, leading to duplicated and cross-purpose use of peripheral blood. These design flaws mirror the low sequence similarity and only moderate parameter accuracy observed in Figure 20, underscoring failures in temporal coordination, branchaware planning, and sample bookkeeping.

Overall, the deviations highlight a critical limitation of current AI models: while they can enumerate plausible wet experiment actions, they struggle to construct experimentally valid, temporally consistent, and branch-aware protocols. These limitations point to fundamental gaps in reasoning about experimental constraints, biological timing, and multi-sample coordination-elements essential for real-world scientific experimentation.

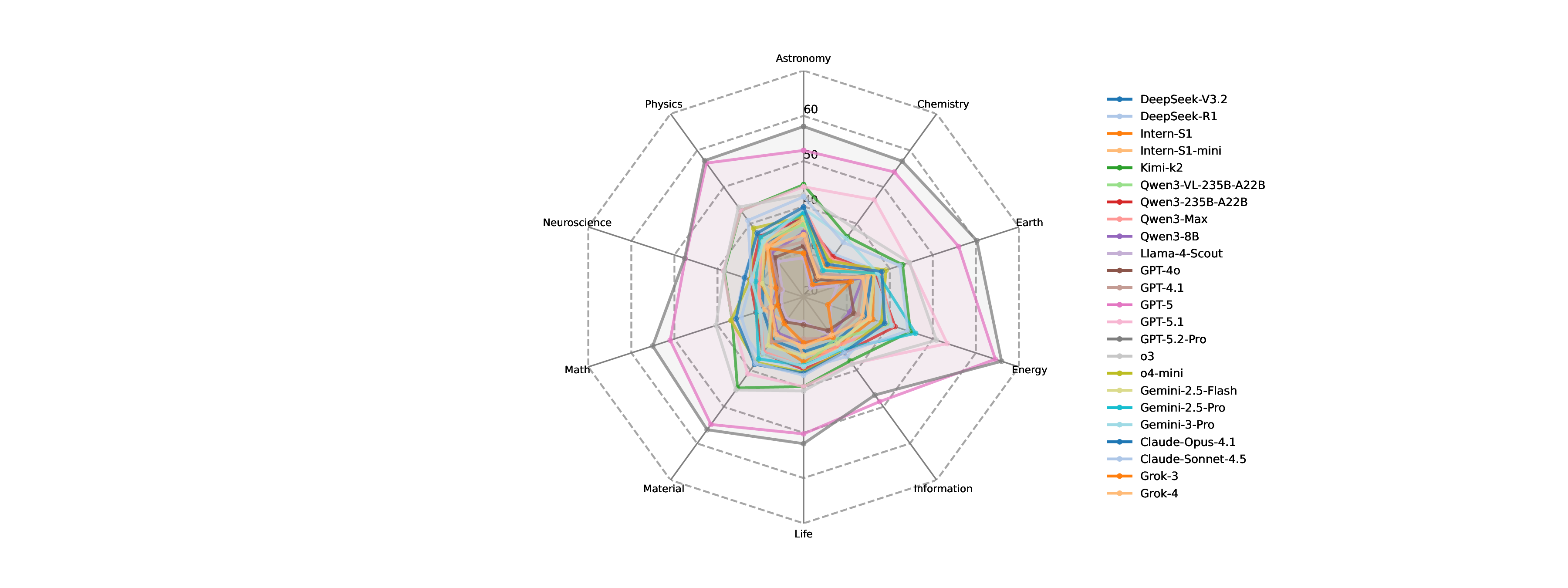

Experimental Reasoning evaluates the ability of multimodal LLMs to interpret experimental observations, integrate heterogeneous scientific evidence, and refine testable hypotheses. As illustrated in Figure 22, the visual inputs span five representative modalities in scientific practice-process diagrams, data visualizations, natural observations, numerical simulations, and laboratory experiments-reflecting the diversity of multimodal information that underpins real-world scientific inquiry.

In this task, models are provided with several images accompanied by a question and must select the correct answer from at least ten candidates (Figure 23). Solving these problems requires multistep inferential reasoning: identifying relevant variables, synthesizing multimodal cues, evaluating competing hypotheses, and ultimately validating consistency across the provided evidence. We therefore evaluate model performance using both Multi-choice Accuracy and Reasoning Validity, the latter assessing whether the model’s explanation follows logically from the scientific evidence.

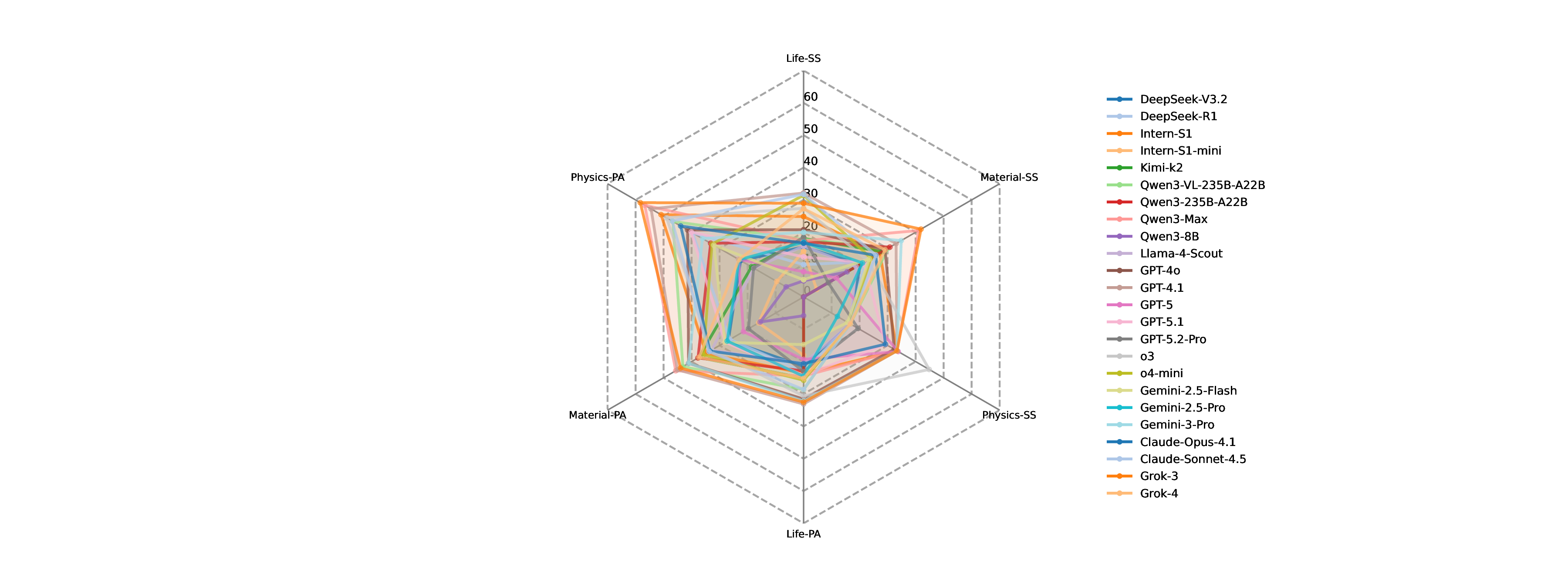

Reasoning validity often exceeds answer accuracy. As shown in Figure 24, closed-source LLMs generally outperform open-source counterparts on both metrics, with the best closed-source models achieving higher MCA (e.g., up to 41.9) and RV (e.g., up to 71.3) than the best open-source models (MCA 37.8, RV 52.3). However, several open-source models remain competitive with or exceed some closed-source systems in specific metrics (e.g., Qwen3-VL-235B-A22B RV 50.5 > GPT-4o RV 45.4), indicating nontrivial overlap. Most models score higher in Reasoning Validity than in Multi-choice Accuracy, suggesting that even when the final choice is incorrect, explanations often preserve partial logical coherence. Variance is moderate-particularly among closed-source models-while only a few models (e.g., Intern-S1-mini) show noticeably lower performance, pointing to the importance of scale for robust multimodal scientific reasoning.

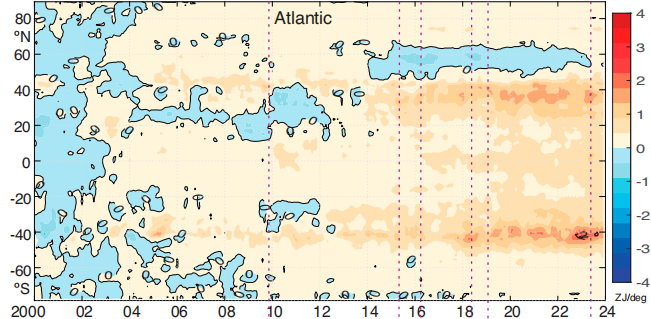

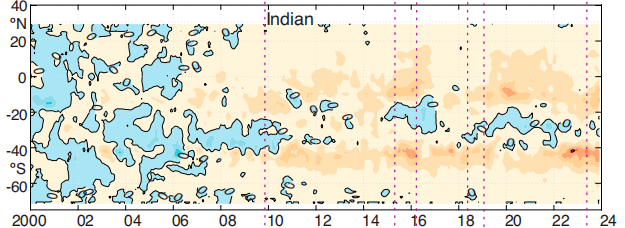

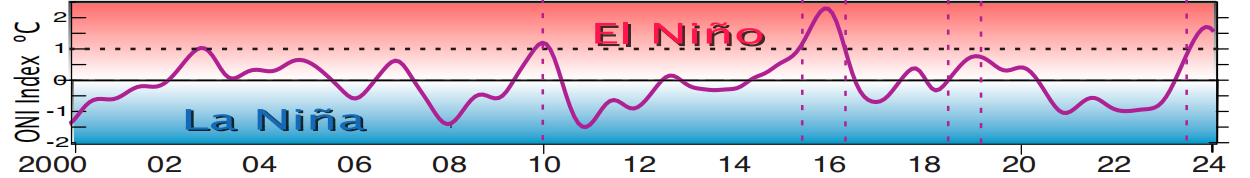

Comparative reasoning is the most challenging across domains. To further dissect these capabilities, we analyze performance across reasoning types and disciplinary domains (Figure 25). From the perspective of reasoning categories, including signal perception, attribute understanding, comparative reasoning, and causal reasoning, LLMs perform consistently well in causal reasoning and perceptual recognition. In contrast, comparative reasoning emerges as a persistent weakness. This indicates that models struggle when required to contrast subtle quantitative or qualitative differences, a cognitive operation fundamental to scientific evaluation and hypothesis discrimination. When examining performance across 10 scientific disciplines, an intriguing pattern emerges. Models achieve their highest accuracy in astronomy, followed by chemistry, energy science, and neuroscience. These domains often feature structured visual patterns or canonical experimental setups, which may align well with LLMs’ prior training data. Conversely, performance declines substantially in materials science, life sciences, and Earth sciences, where visual cues are more heterogeneous, context-dependent, or experimentally nuanced. This divergence suggests that domain-specific complexity and representation diversity strongly influence multimodal reasoning performance. Overall, these findings reveal that while current LLMs demonstrate encouraging abilities in integrating scientific evidence and conducting basic causal analyses, they still fall short in tasks requiring precise discrimination, cross-sample comparison, and nuanced interpretation of domain-specific observations. The relatively narrow performance gap among leading models underscores that scale alone is insufficient; advancing experimental reasoning will require improved multimodal grounding, finer-grained visual understanding, and training paradigms explicitly aligned with scientific inquiry.

Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in reasoning and problemsolving, primarily driven by supervised fine-tuning and reinforcement learning on extensive labeled datasets. However, applying these models to the frontier of scientific discovery, particularly in the task of scientific idea generation, presents a fundamental challenge: the inherent absence of ground truth. Unlike closed-domain tasks such as mathematical reasoning or code generation, where solutions can be verified against a correct answer, the generation of novel research ideas is an open-ended problem with no pre-existing “gold standard” labels. This limitation renders traditional offline training pipelines insufficient for adapting to dynamic and unexplored scientific territories.

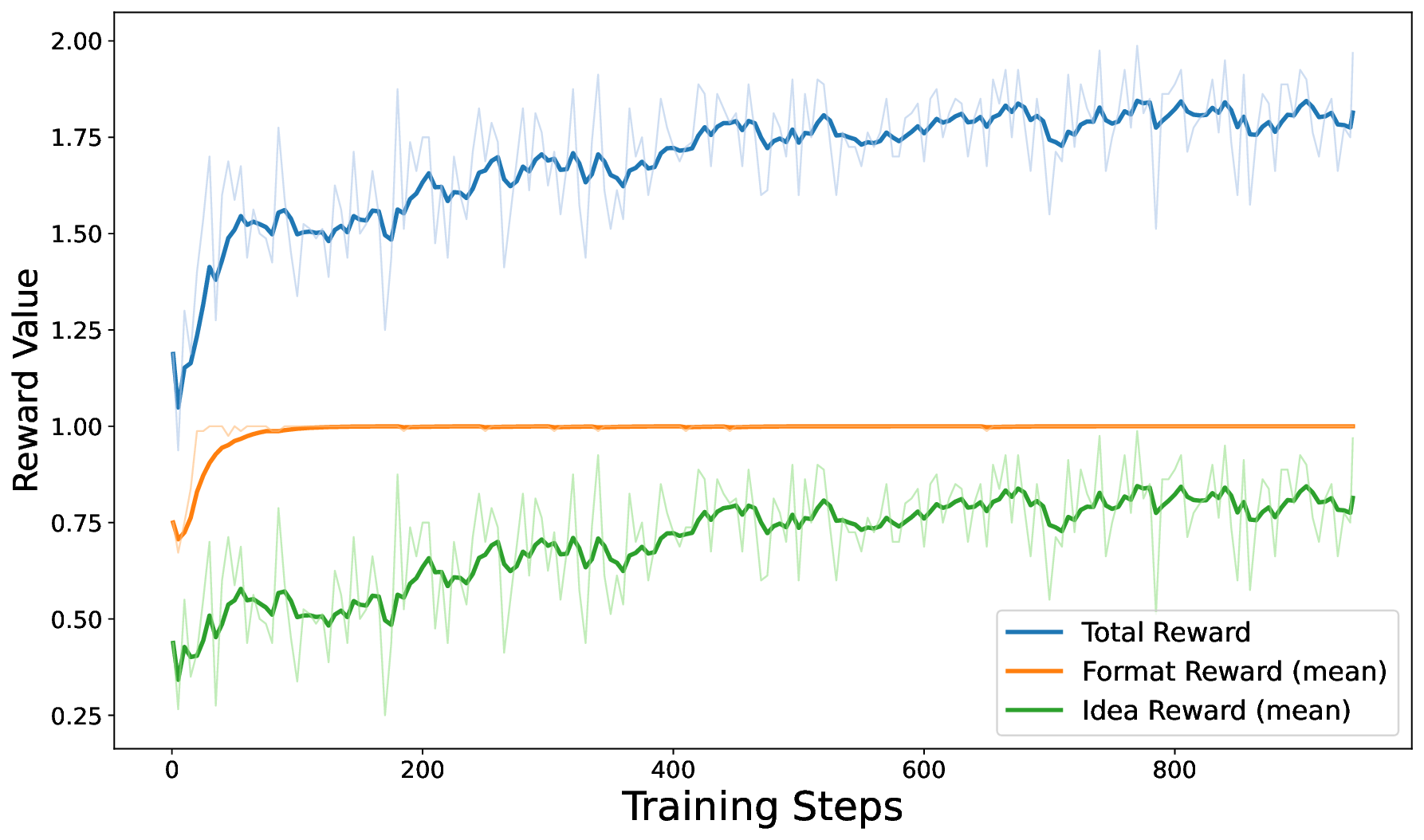

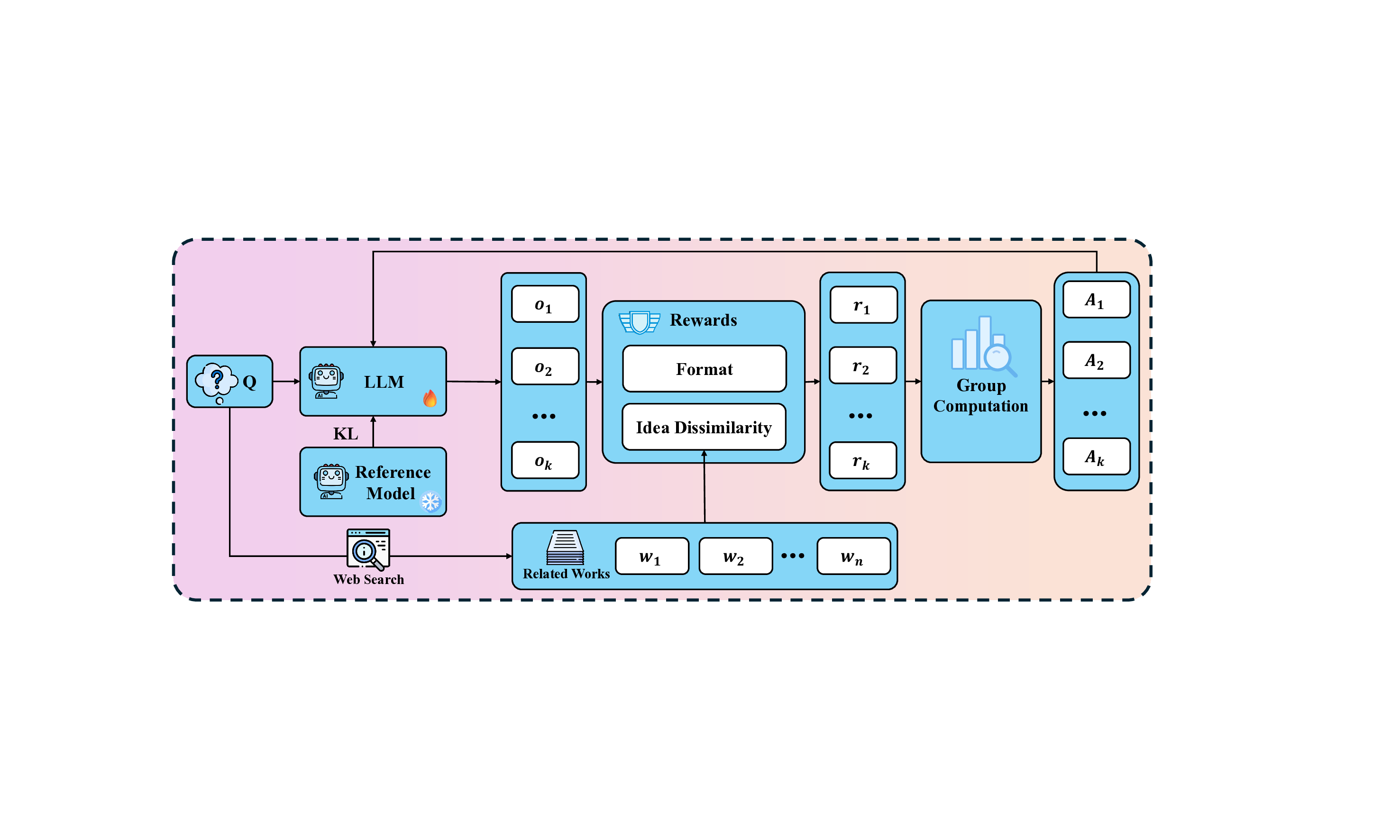

To address this, we adopt the paradigm of Test-Time Reinforcement Learning (TTRL) [20]. This framework enables models to self-evolve on unlabeled test data by optimizing policies against rule-based rewards derived from the model’s own outputs or environmental feedback. Distinct from the original implementation [20], which primarily leveraged consensus-based consistency as a reward mechanism for logical reasoning tasks, we establish novelty as our core optimization objective in the current context. Consequently, we introduce a TTRL framework where the reward signal is constructed based on the dissimilarity between generated ideas and retrieved related works, guiding the model to actively explore the solution space and maximize innovation at test time.

To address the absence of ground truth in scientific idea generation, we propose a generalizable reward mechanism based on online retrieval. Instead of relying on static labels, we utilize real-time search to fetch existing related works, serving as a dynamic baseline for comparison. This approach enables us to quantify novelty as the semantic dissimilarity between the model’s output and the retrieved context, effectively converting an open-ended exploration problem into a measurable optimization task. The overall training framework is illustrated in Figure 26.

We employ Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) [1] as our training backbone. For a given query 𝑄, the policy model 𝜋 𝜃 generates a group of 𝑘 outputs {𝑜 1 , . . . , 𝑜 𝑘 }. The optimization is guided by a composite reward function, defined as the unweighted sum of a format constraint and a novelty metric (labeled as Idea Dissimilarity in Figure 26):

where W = {𝑤 1 , . . . , 𝑤 𝑛 } denotes the set of related works obtained via online search.

To guarantee interpretable reasoning, we enforce a strict XML structure.

The model must encapsulate its chain of thought within

Novelty Reward (𝑅 novelty ). We quantify novelty by measuring the vector space dissimilarity between the generated idea and the retrieved literature. Let e idea be the embedding of the generated answer, and {e 𝑤 𝑗 } 𝑛 𝑗=1 be the embeddings of 𝑛 retrieved papers (denoted as 𝑤 1 , . . . , 𝑤 𝑛 in the figure). We compute the average cosine similarity 𝑆 avg :

An innovation score 𝑆 inn ∈ [0, 10] is then derived to reward divergence:

Using a gating threshold 𝜏 = 5, the final novelty reward is defined as:

This mechanism incentivizes the model to produce ideas that are semantically distinct from existing work.

We employ Qwen3-8B as the base model, trained using the GRPO algorithm within the ms-swift [77] framework. To facilitate diverse exploration, we utilize a high sampling temperature. Key hyperparameters are detailed in Table 8. Figure 27 | TTRL Training Dynamics: Format reward saturates quickly, followed by steady growth in idea novelty.

The training dynamics of our TTRL framework are illustrated in Figure 27. The curves demonstrate a clear two-phase optimization process. Initially, the Format Reward (orange line) rises rapidly and saturates near 1.0 within the first few steps, indicating that the model quickly adapts to the rigid XML structural constraints (

Quantitatively, this self-evolution process yields a significant improvement in the quality of generated ideas. The average novelty score of the model’s outputs increased from a baseline of 49.36 to 62.06.

It is important to emphasize that this performance gain was achieved entirely without ground-truth labels. The model improved solely by leveraging the online retrieval feedback loop, validating the hypothesis that LLMs can self-improve on open-ended scientific discovery tasks through test-time reinforcement learning.

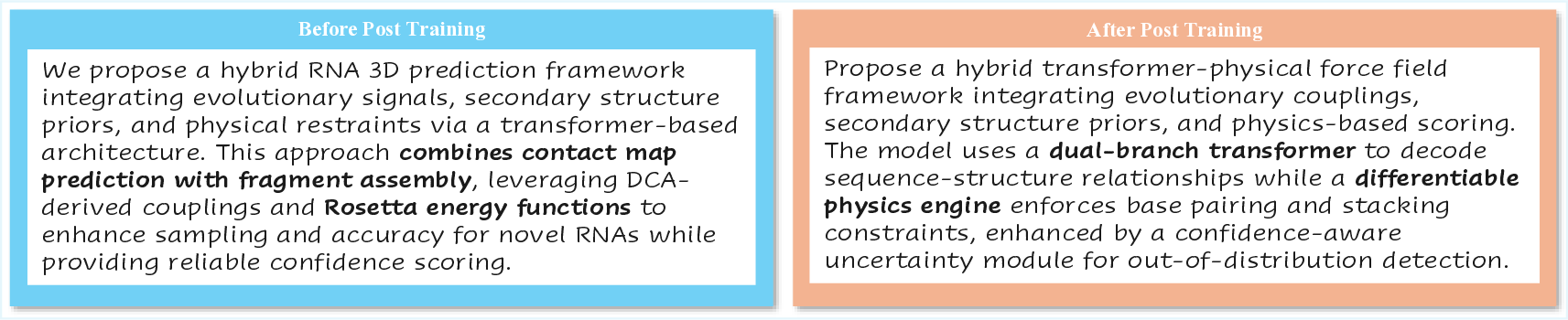

To visually demonstrate the impact of TTRL on scientific idea generation, we present a comparative case study in Figure 28. The task requires the model to propose a novel framework for RNA 3D structure prediction.

We propose a hybrid RNA 3D prediction framework integrating evolutionary signals, secondary structure priors, and physical restraints via a transformer-based architecture. This approach combines contact map prediction with fragment assembly, leveraging DCAderived couplings and Rosetta energy functions to enhance sampling and accuracy for novel RNAs while providing reliable confidence scoring.

Propose a hybrid transformer-physical force field framework integrating evolutionary couplings, secondary structure priors, and physics-based scoring.

The model uses a dual-branch transformer to decode sequence-structure relationships while a differentiable physics engine enforces base pairing and stacking constraints, enhanced by a confidence-aware uncertainty module for out-of-distribution detection.

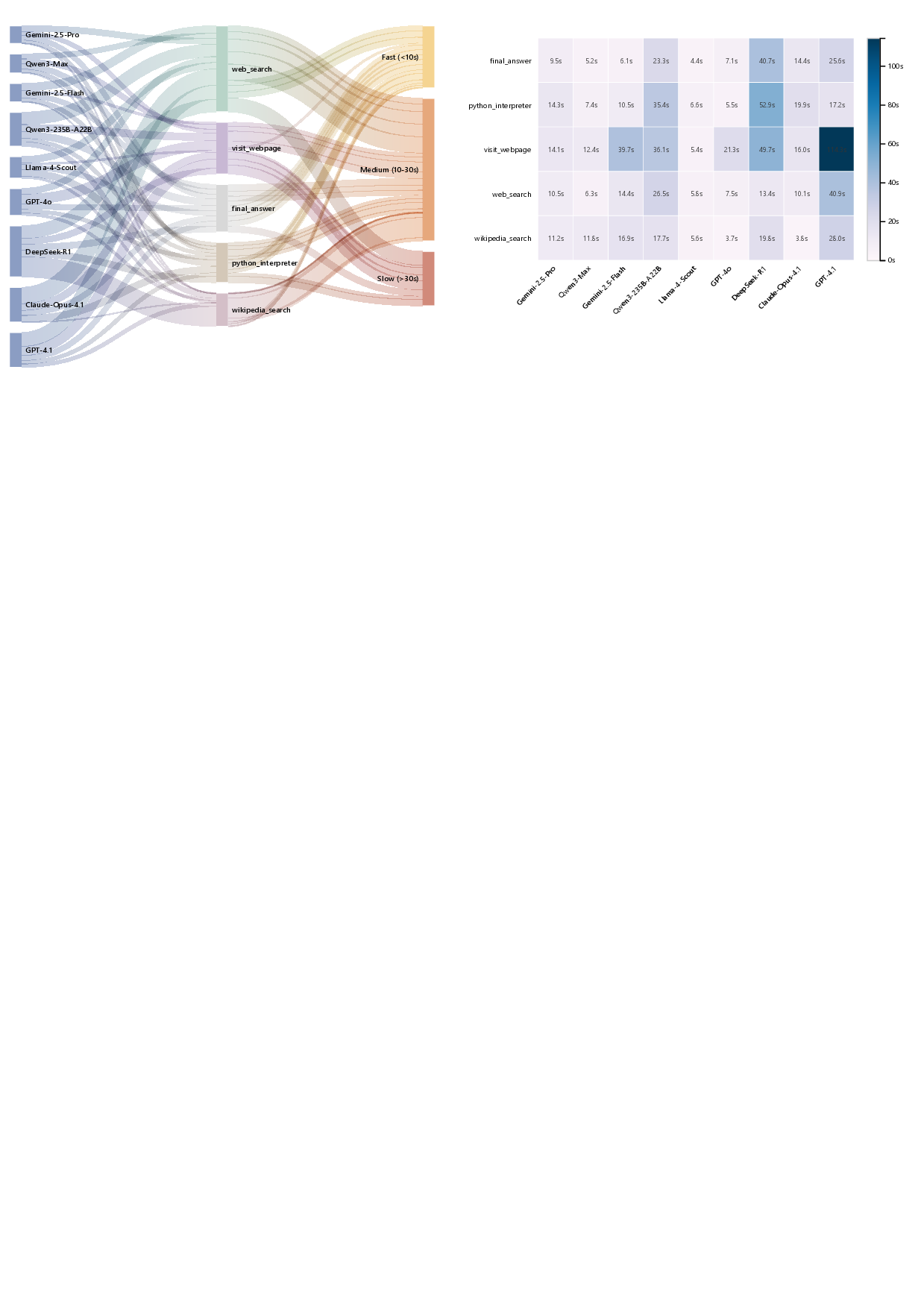

Tool-Integrated Reasoning (TIR) in real tasks unfolds as a dynamic, opportunistic process rather than a fixed linear chain [78]. As shown in Figure 29 (left), the model-to-tool flow concentrates heavily on retrieval actions: web_search is the most frequently invoked tool with 539 calls (33.98% of all), followed by visit_webpage (385, 24.27%), final_answer (358, 22.57%), python_interpreter (200, 12.61%), and wikipedia_search (104, 6.56%). This distribution indicates that an external “retrieve-then-browse” loop remains the dominant path for contemporary agentic systems, reflecting persistent limits in time-sensitive and domain-specific knowledge available to base LLMs. Importantly, models differ in how efficiently they traverse this loop: for example, GPT-4.1 issues large volumes of web_search (168) and visit_webpage (110) that frequently land in slow tiers, whereas Qwen3-Max completes comparable coverage with far fewer retrieval and browsing steps (61 and 59, respectively). Practically, this pattern implies that reducing redundant retrieval iterations-via better query formulation and higher-quality extraction on the first pass-has immediate leverage on end-to-end latency, often exceeding gains from marginal improvements to raw model inference.