Due to the restricted resources, efficient scheduling in vertiports has received much more attention in the field of Urban Air Mobility (UAM). For the scheduling problem, we utilize a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP), which is often formulated in a resourcerestricted project scheduling problem (RCPSP). In this paper, we show our approach to handle both dynamic operation requirements and vague rescheduling requests from humans. Particularly, we utilize a three-valued logic for interpreting ambiguous user intents and a decision tree, proposing a newly integrated system that combines Answer Set Programming (ASP) and MILP. This integrated framework optimizes schedules and supports human inputs transparently. With this system, we provide a robust structure for explainable, adaptive UAM scheduling.

Urban Air Mobility (UAM) introduces a new traffic paradigm that requires efficient management of vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) resources. In this context, scheduling is formulated in a resource-constrained project scheduling problem (RCPSP), which is often solved through a mixed integer linear programming (MILP) approach. The dynamic nature of UAM, however, also requires human operators to fluidly control the schedules in order to meet the real-time requirements. is because misunderstanding the intent is able to affect the efficiency and the trust negatively. To address this, we propose a system that combines a MILP-based scheduler with an Answer Set Programming (ASP) module for intent interpretation. This module uniquely uses three-valued logic and decision trees to resolve ambiguity.

In order to make it easy to understand the reasoning process of the system under the schedule revision, we utilize a declarative approach of ASP. This can cover both explicit and vague inputs and reason on its proper handling, keeping the interpretability. This improves the system’s reactivity, building user trust and meeting the explainable HRI rules.

We previously studied human interaction in Urban Air Traffic Management (UATM) systems [1,2,3,4]. These studies mainly focused on handling route changes and reactive event processing (such as detours and vertiport closures) using knowledge representation and reasoning. Extending this direction, we recently studied the vertiport resource scheduling problem. Particularly, we utilized ASP in order to meet the constraints of various stakeholders within RCPSP formulations [5]. This paper, based on the study, focuses on vertiport rescheduling, handling the issues of interpreting ambiguous requests from human operators in dynamic operational settings.

The contributions of this paper are threefold: firstly, we formulate UAM scheduling as an RCPSP for the purpose of utilizing the MILP solver to compute the schedule, secondly, we introduce an ASP-based intent recognition mechanism that utilizes three-valued logic, and lastly, we propose an explainable system that integrates human intent and automated scheduling. In the following sections, we cover related works, approaches, experiments, and conclusions in detail.

Vertiports play the role of hubs that are built for operating eVTOLs in urban settings. Research in [6,7,8] shows that the efficacy of UAM largely depends on the proper scheduling. Essentially, authors in [9,10] provided that scheduling these jobs is complex due to limited resources, integration with urban systems, and safety constraints . This problem, therefore, is formulated as an RCPSP. This problem is in the NP-hard class, which is to optimize the makespan while keeping the resource and precedence constraints (refer to [11,12]). In such constraints, MILP has been broadly utilized [13,14] even though it requires a high computational cost in order to derive optimal schedules in various domains [15]. In addition, meta-heuristics and various optimization strategies have been developed in order to handle uncertainties [16,17,18,19,20].

The research in [21,22,23] indicates that it becomes more challenging to accurately recognize the users’ intent in coordination when integrating human operators into an automated scheduling system. Particularly, resolving the ambiguity is the key issue when human inputs are unclear or not properly defined. Research in [24,25,26] proves that methodologies utilizing multi-valued logic systems and decision trees show some potential to manage the uncertainties in decision-making contexts.

The declarative programming paradigm enables the resolution of complex problems within a systematic and verifiable framework. The effectiveness of ASP, in particular, has been demonstrated in the domain of knowledge representation and reasoning. [27,28,29,30] showed its ex-pressiveness, enabling us to model complex problems such as scheduling and decision-making under uncertainty. This transparency aligns with the objectives of explainable AI (XAI) pursuits in the human-robot interaction domain. Providing a clear explanation for the system’s decision-making process can build user trust, guarantee accountability, and lead to effective human-AI collaboration (refer to [31,32,33,34,35]). This research implements an explainable UAM scheduling system that is responsive to human intent, following ambiguity resolution rules through ASP.

The Resource Constrained Project Schedule Problem (RCPSP) aims to find a schedule for tasks J = {0..n + 1} that minimizes the project completion time (deadline). This schedule is constrained by a priority constraint S 0 between tasks and a set of available renewable resources R = {1..m}. The limit C r of resources R = {1..m} must be observed. Each job j has a duration p j and requires a resource r of unit u 0 jr while the job is active. Jobs 0 and n + 1 are dummy start and end jobs.

The general MILP formulation uses binary variables x jt where x jt = 1 if task j starts at time t and 0 otherwise. The objective is to minimize the start time of the final task:

s.t.

∑ t tx st -∑ t tx jt ≥ p j ∀( j,s) ∈ S 0 (1d)

Constraints ensure each task starts exactly once (1b), resource capacities are not exceeded (1c), and precedence relations are met (1d). An example RCPSP instance is provided in Table 1. Figure 2b is a visual representation of the schedule that corresponds to the related schedule.

A categorization of typical rescheduling strategies is provided in Table 2, which is based on the literature reviewed by [36]. Our framework is centered on the following options that are highlighted: Partial Rescheduling and Resource Reallocation, more precisely the application of alterations to the start time of a single job or the quantity of resources that are required.

UAMs require frequent and quick rescheduling to maintain operations. Our system utilizes an explainable answer set programming (ASP), integrating MILP-based RCPSP scheduling to effectively handle these changes. Here explainability plays an important role in human-robot interactions within UAM because it helps build trust by providing transparent reasoning for system decisions. [31,32].

Our approach is “intent-driven”: it interprets the user’s underlying goal when requesting a schedule change. By analyzing the request type (start time or resource adjustment) and potentially ambiguous user input, the ASP module determines the appropriate rescheduling action and explains its reasoning.

Scope: The single task rescheduling within the UAM operation is the main focus of this study and is performed through partial rescheduling or resource reallocation. In this scope, we consider two requirement options: making adjustments to the start time of a specific job and the resources that are required. An important aspect of this coverage is to decide whether the task’s original precedence constraints should be kept or if they should be removed in order to allow for independent optimization throughout the adjustment.

Exclusions: The scope does not cover global schedule reoptimization, reordering multiple tasks, or major structural changes involving adding/removing multiple tasks.

This section specifies in detail the process of extracting user intent from potentially ambiguous rescheduling requests and formulates the corresponding rescheduling problem.

We consider that an initial rescheduling request Q for a specific task t * may contain ambiguities. This request is represented as follows:

where:

• δ ∈ {unknown, 0, 1} is to express the type of optimization for a time change request. 0 is to respect start times of other tasks, only allowing local change; 1 is to optimize globally; and ‘unknown’ represents ambiguity.

• ρ ∈ {unknown, 0, 1} is to express the type of relationship to be maintained for a time change request. 0 is to relax precedence constraints for t * ; 1 is to maintain the precedence relation; and ‘unknown’ represents ambiguity.

• η ∈ {unknown, 0, 1} is to express the type of optimization for a resource amount change request. 0 is to respect start times of other tasks, only allowing local change; 1 is to optimize globally; and ‘unknown’ represents ambiguity.

• θ ∈ {unknown, 0, 1} is to express the type of relationship to be maintained for a resource amount change request. 0 is to relax precedence constraints for t * ; 1 is to maintain the precedence relation; and ‘unknown’ represents ambiguity.

• τ * ∈ Z ≥0 is the desired start time for task t * .

• R * ∈ Z m ≥0 is the desired resource requirement vector for task t * , where m is the number of resource types.

If one of δ , ρ, η, θ has ‘unknown’ as its value, an interactive process is required in order to clarify the user’s true intent.

We resolve the ambiguity the initial request Q has through interactions with the user. We utilize the concept of interaction history in order to implement this interaction process. We denote this history as H . H consists of a sequence of tuples, and each tuple captures an interaction.

H = [(q (0) , a (0) ), (q (1) , a (1) ), . . . , (q (T ) , a (T ) )]

Here, q (t) indicates the inquiry the system asks the user to clarify the ambiguity at step t, and a (t) is the corresponding response from the user. Every interaction step is appended as a new (q, a) tuple to H .

The system uses the interaction mapping function I to determine the user’s fully clarified intent by utilizing the initial request Q and the accumulated history H :

The output is an intent vector, which is fully clarified as follows:

where: This vector b * clearly defines conditions for the following rescheduling process.

We define a rescheduling process as applying a transition operator R to the baseline schedule S 0 , given a request Q for a task t * . R : (S 0 ,t * , Q) → (S, E)

where:

• Input:

-

S 0 is the current baseline schedule.

-

t * ∈ J is the target rescheduling task.

-

Q is a tuple that contains a potentially ambiguous rescheduling request.

• Process:

2 ) through I (Q, H ). • Output:

-S: The new, updated schedule.

-E: An explanation of the rescheduling action.

2 specify scope (1) and precedence (2) handling for start-time (s) and resource (r) requests. For conciseness, when the request type is clear (start-time or resource), we will simplify this to b 1 (scope) and b 2 (precedence).

Problem 1 Given a baseline schedule S 0 and a (potentially ambiguous) reschedule request Q for a task t * , compute a new schedule S and a corresponding explanation E by first interactively clarifying the user’s intent b * from Q via H , and then executing the intent-driven rescheduling process R.

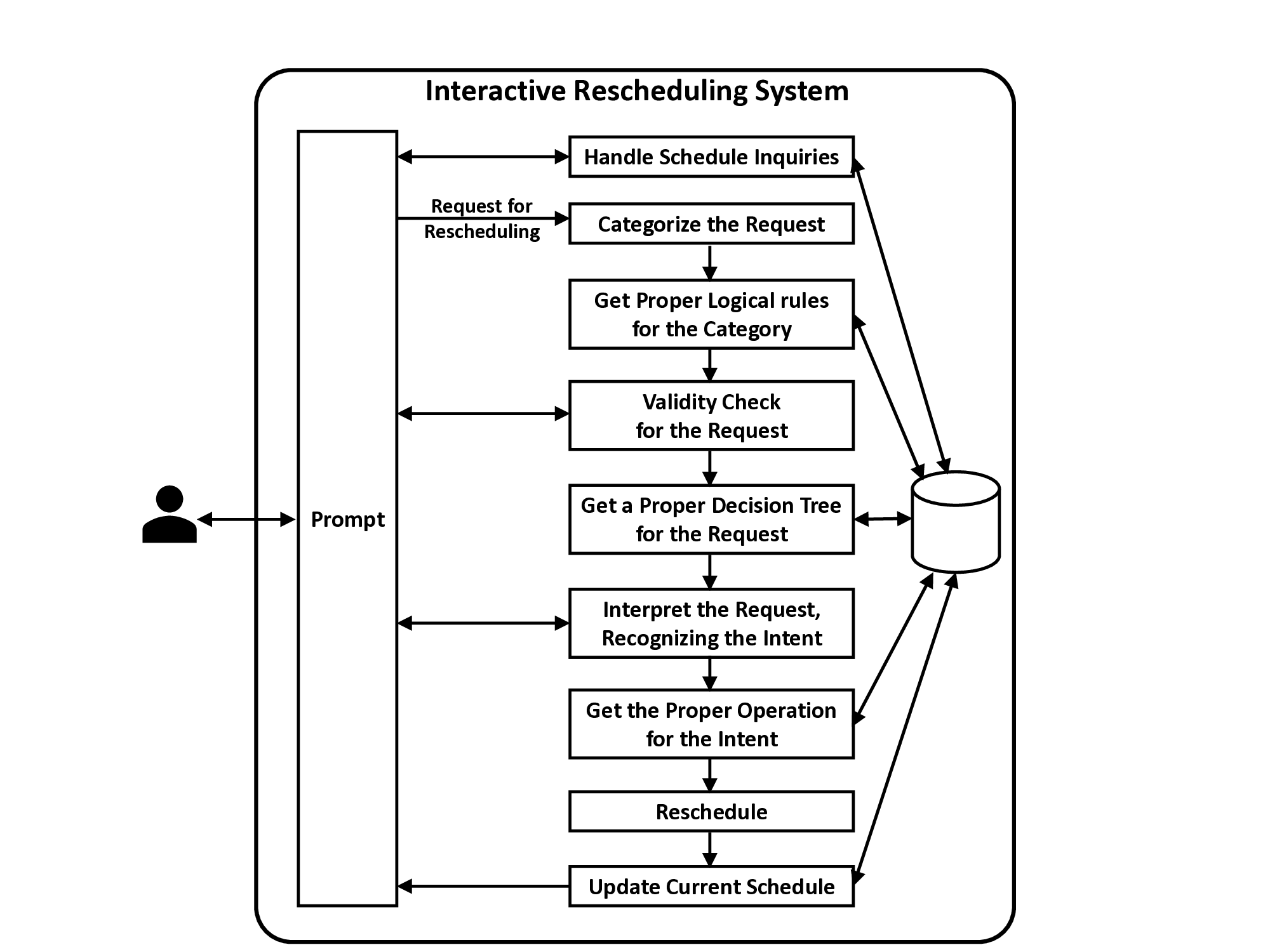

Figure 1 depicts the system’s process. A user prompt starts it. Rescheduling requests are categorized and validated using logic. After interpreting the request, a decision tree can interact with the user via prompts to resolve ambiguity and determine the user’s intent b * . This intent identifies and performs the right rescheduling operation (parameter/constraint modifications) to solve the RCPSP. Updated schedule S and explanation E are returned. A central database maintains rules, trees, and schedules.

This section describes the method for extracting user intent from potentially ambiguous requests and the subsequent rescheduling process.

The process begins by validating the user request and then interpreting the underlying intention using ASP and an interactive decision tree approach.

ASP rules check if the request parameters (task ID, desired time/resource) are valid within the problem constraints.

The listing below shows the validity check for a start time change request.

request(n, i).

(

valid_task ←request(N, I),task(N).

(

valid_time ←request(N, I), I ≤ I2, step(I), total_dur(I2).

result(valid_request) ←valid_task, valid_time.

result(invalid_task) ←¬valid_task, valid_time.

result(invalid_time) ←¬valid_time, valid_task.

The listing below shows the validity check for a resource amount change request.

request(n, r, a).

resource(R) ←rsreq(N, R, A). ( 9)

valid_resource ←request(N, R, A), resource(R).

valid_amount ←request(N, R, A1), A1 ≤ A2, limit(R, A2). ( 13)

result(invalid_task) ←¬valid_task. (15) result(invalid_resource) ←¬valid_resource. ( 16)

ASP combined with three-valued logic (⊤, ⊥, ℧ for true, false, unknown) and external atoms (#external sym/2) models a decision tree for clarifying intent. The system queries the user (query/1) when information is unknown (℧).

The listing below shows the generic decision tree generation logic in ASP for n boolean decision points.

#external sym(S,V ) : symbol(S), value(V ). ( 18)

value("⊤"; “⊥”). ( 20) 1{⊤(S); ⊥(S); ℧(S)} ←symbol(S), value(V ).

℧(S) ←¬sym(S, “⊤”), ¬sym(S, “⊥”), symbol(S). ( 22) contradiction(S) ←sym(S, “⊤”), sym(S, “⊥”), symbol(S).

℧(S) ←contradiction(S), symbol(S).

←¬⊤(S), sym(S, “⊤”), symbol(S).

←¬⊥(S), sym(S, “⊥”), symbol(S). ( 26)

observed(S,V ) ←sym(S,V ), symbol(S), value(V ).

assumed(S, “¬⊥”) ←observed(S, “⊤”), ¬sym(S, “⊥”),

assumed(S, “¬⊤”) ←observed(S, “⊥”), ¬sym(S, “⊤”),

known(S, “⊤”) ←observed(S, “⊤”), assumed(S, “¬⊥”),

known(S, “⊥”) ←observed(S, “⊥”), assumed(S, “¬⊤”), symbol(S).

←known(S, “⊤”), known(S, “⊥”), symbol(S).

We assume a default symbol order:

Intentions are defined based on the final known states. For n = 2:

intent(“op_00”) ←known(2, “⊥”), known(1, “⊥”). (35) intent(“op_01”) ←known(2, “⊥”), known(1, “⊤”). (36) intent(“op_10”) ←known(2, “⊤”), known(1, “⊥”). (37) intent(“op_11”) ←known(2, “⊤”), known(1, “⊤”).

(38)

Algorithm 1 details the interactive intention interpretation process. It categorizes and validates the request, then iteratively uses the ASP decision tree logic, potentially querying the user via interaction history H , until the intent b * (represented by known/2 facts) is fully resolved or a timeout occurs. It returns the final intent b * , request type γ, and an explanation E.

Input : A baseline schedule S 0 , a task t * , and an initial request Q Output: An intention b * , a request type γ, and explanation E 1 Categorize the request type γ with given inputs ; 2 Check the validity for Q and γ with Eq.( 2)- (7) or Eq.( 8)-( 17 Algorithm 2 prepares the problem for a standard RCPSP solver based on the interpreted intent (γ, b 1 , b 2 ), desired start time τ * , and resources R * for task t * . It modifies the baseline resource requirements (u 0 → u ′ ) and precedence relations (S 0 → S ′ ) according to the intent flags. Crucially, it determines the set of tasks T f that must be fixed at specific start times τ f . This always includes t * at τ * . If b 1 = 0 (local scope), it attempts to fix predecessors of t * at their baseline times (S 0 ), but only if they don’t conflict with t * or each other and are not required to be flexible due to conflicts propagated from t * . Feasibility checks ensure the requested placement of t * respects precedence and that the final set of fixed tasks T f is resource-feasible. The output is a modified problem instance ( S ′ , u ′ , T f , τ f ) suitable for the solver, or an infeasibility status.

The algorithm uses helper functions:

• CheckTotalConflicts: Identifies baseline tasks conflicting resource-wise with t * at τ * .

• PropagateFlexibility: Finds all tasks (conflicting ones and their successors) that cannot be fixed at baseline times.

• CheckResourceFeasibility: Verifies if a given set of fixed tasks (T f , τ f ) is resource-feasible.

• BuildSuccessorMap: Creates a lookup map for task successors based on S ′ .

Algorithm 2: Pre-process

Input :

• Request Data: Target task t * , desired time τ * , desired resources R * , request type γ, intention b 1 and b 2 ;

• Baseline Data: Tasks T , Resources R, Durations p, Precedences S 0 , Resource Function u 0 , Capacity C, Horizon H, Baseline schedule S 0 ;

return Infeasible: Final fixed set T f violates resources 27 return S ′ , u ′ , T f , τ f

The overall rescheduling process is managed by a dispatcher mechanism. After INTERPRETINTEN-TION (Alg. 1) determines the request type γ and intent flags (b 1 , b 2 ), the dispatcher selects the appropriate logic flow. This involves calling the PRE-PROCESS function (Alg. 2) with the specific intent flags. If preprocessing is successful and returns a feasible modified instance (⟨S ′ , u ′ , T f , τ f ⟩), the dispatcher formulates this as an RCPSP problem with fixed tasks and passes it to a standard RCPSP solver. If preprocessing fails or the solver returns infeasible, the dispatcher reports the failure and the reason derived from the preprocessing or solving stage. Otherwise, the final schedule returned by the solver is the output. This structure allows different combinations of user intentions to be handled by the same core preprocessing and solving steps, varying only the parameters passed to PRE-PROCESS.

In order to build trust via human-automation interaction, we show the formal guarantees on the termination of the intent extraction process and its correctness. We here define the status of the user’s intent in the domain {⊤, ⊥, ℧} at step k as vector v k .

Theorem 1 (Convergence) Let S denote a set of n decision symbols required to completely specify the request. Assuming that the user always answers inquiries from the system in the given time, the InterpretIntention algorithm terminates in at most n steps of interaction.

Proof Let U k = {s ∈ S | value(s) = ℧} denote a set of undecided symbols at iteration k. Since initially U 0 = S , |U 0 | = n. This is executed iteratively. In the While loop in Alg. 1, the system identifies the symbol s * ∈ U k and generates an inquiry. When a response a ∈ {⊤, ⊥} (or the timeout) is returned, the ASP solver derives the predicate known(s * , a). Thus, the rule for the default negation of ℧ does not hold any longer as follows:

Then, the cardinality of the set becomes strictly decreasing until it reaches 0, which is the lower bound. When |U k | = 0, the set of all symbols turns to a known state. The ASP rule (Eq. 38) for intent requires the conjunction of every s ∈ S to be a known state. When |U k | = 0, this condition holds, and then it derives foundIntention, terminating the loop.

Theorem 2 (Correctness) The intent code b * derived from the system is exactly matched with the conjunction of the user’s sequence of answers.

Proof The decision tree ∆ is to implement the boolean function f : {0, 1} n → I , and here I is a set of intent labels. ASP encoding enforces that the observed history H is in a bijection relation between internal states. For an arbitrary input vector a = (a 1 , . . . , a n ), the interactive loop guarantees the assertion of a set of facts F = {known(i, a i ) | 1 ≤ i ≤ n}. The intent rules have the following form:

Since stable model semantics guarantees that the consequence is derived if and only if the bodies are satisfied, a unique intent label L that is corresponding to a is derived. The constraint contradiction/1 guarantees logical consistency by restricting a conflict state (for example, setting to ⊤ and ⊥ simultaneously) from occurring.

This research proposed an intention-aware rescheduling methodology in order to handle ambiguous human requests in UAM vertiport operations in RCPSP settings. For the proposed solution, we showed the integration of ASP-driven intent interpretation through three-valued logic and MILPdriven optimization. ASP provides transparency, builds trust, and enables an explainable rescheduling system.

Computational scalability, deeper intent modeling, and online, dynamic scheduling for realtime UAM should be addressed in the future. Practicality and user approval must be confirmed by thorough usability research.

16 Update b * 21 H ← H + ⟨i, / 0⟩ ; ▷ The symbol index i from query/1 22 Based on H , Ask the user and Wait for time κ. ; 23 Assign external sym/2 referring to the responded H ; 24 else ▷ For the case where the predicates is empty 25 Assign external sym/2 referring to the given inputs ; 26 Execute ∆ , Parse the result, and Update the predicates ; 27 K curr ← Get current time ; 28 if K curr -K base ≥ TIME_LIMIT then 29 foundIntention ← ⊤ ; 30 E ← {timeout/0} ; 31 return ⟨b * , γ, E⟩ 6.2 Pre-processing for RCPSP Solver

- ; 9 Remove (t * , j) from S ′ for all j ∈ S 0 t * ; 10 Add (i, j) to S * then 14 return Infeasible: τ * < earliest predecessor finish time 15 T f

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.