Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly applied to scientific research, yet prevailing science benchmarks probe decontextualized knowledge and overlook the iterative reasoning, hypothesis generation, and observation interpretation that drive scientific discovery. We introduce a scenariogrounded benchmark that evaluates LLMs across biology, chemistry, materials, and physics, where domain experts define research projects of genuine interest and decompose them into modular research scenarios from which vetted questions are sampled. The framework assesses models at two levels: (i) question-level accuracy on scenario-tied items and (ii) project-level performance, where models must propose testable hypotheses, design simulations or experiments, and interpret results. Applying this two-phase scientific discovery evaluation (SDE) framework to state-of-the-art LLMs reveals a consistent performance gap relative to general science benchmarks, diminishing return of scaling up model sizes and reasoning, and systematic weaknesses shared across top-tier models from different providers. Large performance variation in research scenarios leads to changing choices of the best performing model on scientific discovery projects evaluated, suggesting all current LLMs are distant to general scientific "superintelligence". Nevertheless, LLMs already demonstrate promise in a great variety of scientific discovery projects, including cases where constituent scenario scores are low, highlighting the role of guided exploration and serendipity in discovery. This SDE framework offers a reproducible benchmark for discovery-relevant evaluation of LLMs and charts practical paths to advance their development toward scientific discovery. This tight connection among questions, scenarios, and projects built in SDE reveals the true capability of LLMs in scientific discovery. Beyond per-question evaluation as in conventional science benchmarks, we also evaluate LLMs' performance at the level of open-ended scientific discovery projects. In this setting, LLMs are put into the loop of scientific discovery, where they are required to autonomously propose testable hypotheses, run simulations or experiments, and interpret the results to refine their original hypotheses, imitating an end-to-end scientific discovery process, where their discovery-orientated outcomes (e.g., polarisability of proposed transition metal complexes) are evaluated. This project-level evaluation reveals capability gaps and failure modes across the research pipeline. Applying this multi-level evaluation framework to state-of-the-art LLMs released over time yields a longitudinal, fine-grained benchmark that reveals where current models succeed, where they fail, and why. The resulting analysis suggests actionable avenues, spanning targeted training on problem formulation, diversifying data sources, baking in computational tool use in training, and designing reinforcement learning strategies in scientific reasoning, for steering LLM development toward scientific discovery.

Results

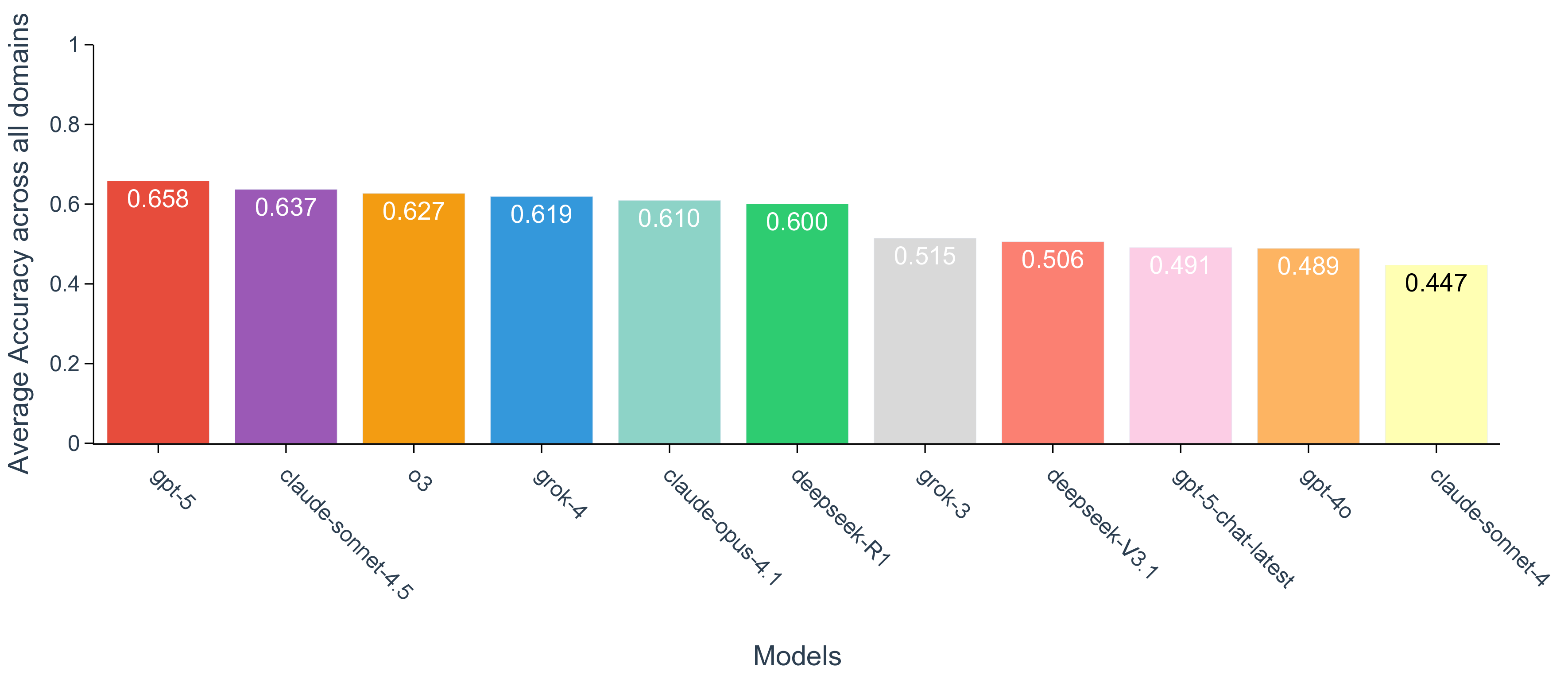

Question-level evaluations Performance gap in quiz-and discovery-type questions. To go beyond the conventional science Q&A benchmark where questions are sometimes assembled opportunistically, questions in SDE are collected in a completely different routine (Fig. 1c ). In each domain, a multi-member expert panel defined roughly ten common research scenarios where LLMs could plausibly help their ongoing projects. These scenarios span a broad spectrum, from those human experts are proficient (e.g., making decisions from specific experimental observations) to those effectively intractable to human experts without the assistance of tools (e.g., inferring oxidation and spin states solely from a transition metal complex structure). When feasible, questions were generated semi-automatically by sampling and templating from open datasets, 46 with NMR spectra to molecular structure mapping as an example. Otherwise, especially for experiment-related scenarios, questions were drafted manually by an expert. Every question underwent panel review, with inclusion contingent on consensus about the validity and correctness, resulting in 1,125 questions in the SDE benchmark (see Methods section, Research scenario and question collection). This design ties every question to a research scenario, ensuring that its correctness reflects progress on a practical scientific discovery project rather than decontextualized trivia, which also allows comparisons across LLMs at the same level of granularity. With the goal of understanding how the performance of popular coding, math, and expression benchmarks translates to scientific discovery, top-tier models from various providers (i.e., OpenAI, Anthropic, Grok, and DeepSeek) are evaluated through an adapted version of lm-evaluation-harness framework, which supports flexible evaluation through a claude-sonnet-4.5 deepseek-V3.1 deepseek-R1 gpt-4o gpt-5-chat gpt-5 grok-3 grok-4 b c d e deepseek-V3.1 deepseek-R1 Accuracy Accuracy Accuracy Accuracy Model S D E -b io lo g y S D E -c h e m is tr y S D E -m a te ri a ls S D E -p h y s ic s G P Q A -D ia m o n d M M M U A IM E -2 0 2 5 S W E -b e n c h V e ri fi e d 0.75 0.75 0.94 0.84 0.86 0.60 g p t -5 g r o k -4 d e e p s e e k -R 1 c l a u d es o n n e t -4 . 5 g p t -5 g r o k -4 d e e p s e e k -R 1 c l a u d es o n n e t -4 . 5 g p t -5 g r o k -4 d e e p s e e k -R 1 c l a u d es o n n e t -4 . 5 e 0 2 4 6 8

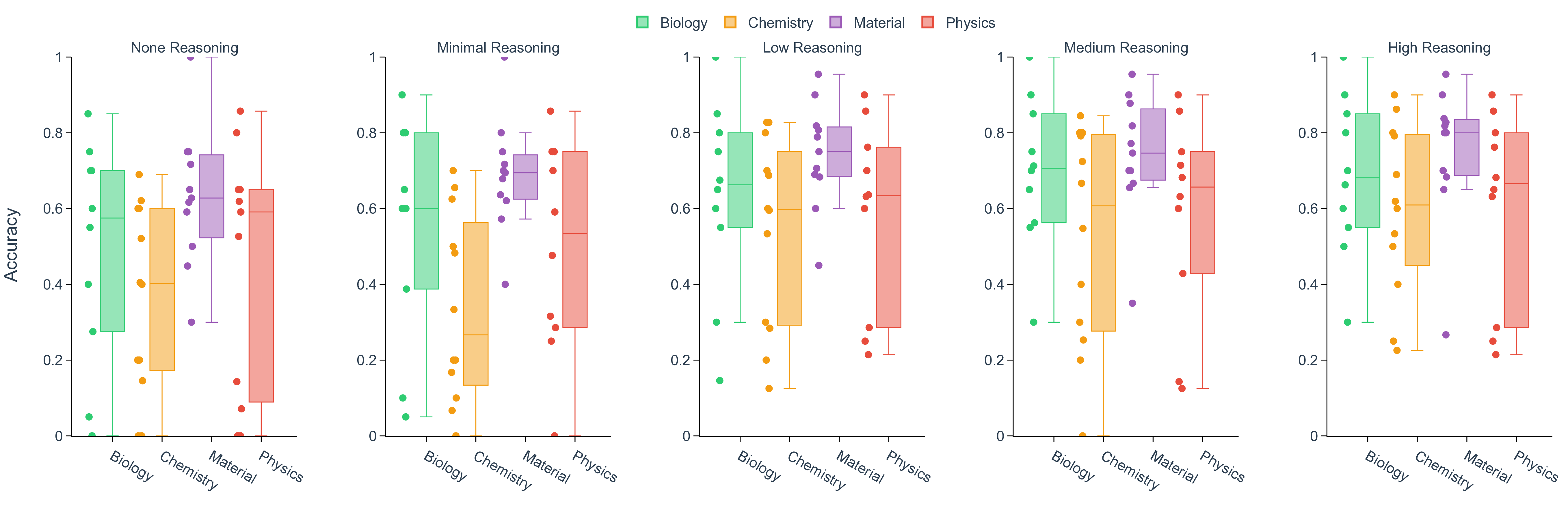

Large language models (LLMs) are beginning to accelerate core stages of scientific discovery, from literature triage and hypothesis generation to computational simulation, code synthesis, and even autonomous experimentation. [1][2][3][4][5][6][7] Starting as surrogates for structure-property prediction and simple question-answering, [8][9][10][11] LLMs, especially with recent reasoning capability emerged from reinforcement learning and test-time compute, further extend their roles in scientific discovery by having the potential to provide intuitions and insights. [12][13][14][15][16][17] Illustrative successes include ChemCrow, 18 autonomous "co-scientists", [19][20][21] and the Virtual Lab for nanobody design 22 that have begun to plan, execute, and interpret experiments by coupling language reasoning to domain tools, laboratory automation, and even embodied systems (e.g., LabOS 23 ). Together, these examples suggest that LLMs can already assist scientists in a "human-in-the-loop" scientific discovery. [24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35] In contrast, evaluation has lagged behind this end-to-end reality in scientific discovery. 36 Benchmarks in coding (e.g., SWE-bench verified 37 ), mathematics (e.g., AIME 38 ), writing and expression (e.g., Arena-hard 39 ), and tool use (e.g., Tau2-bench 40 ) have matured into comparatively stable tests with clear ground truth and strong predictive validity for capability gains (Fig. 1a). Widely used science benchmarks (e.g., GPQA, 41 ScienceQA, 42 MMMU, 43 Humanity's Last Exam 44 ), however, remain largely decontextualized, perception-heavy question and answering (Q&A), with items loosely connected to specific research domains and susceptible to label noise (Fig. 1b). Mastery of static, decontextualized questions, even if perfect, does not guarantee readiness to discovery, just as earning straight A's in coursework does not indicate a great researcher. [45][46][47] As LLMs become more deeply integrated into scientific research and discovery workflows, proper evaluation must measure a model's ability of understanding the specific Existing benchmarks often contain questions that are less relevant to scientific discovery or incorrect answers as ground-truth. c. The SDE framework anchors assessment to projects and realistic research scenarios within each scientific domain, producing tightly coupled questions, enabling more faithful evaluation of LLMs for scientific discovery. LLMs are evaluated on both question and project levels. A project of discovering new pathways for artemisinin synthesis is shown as an example, which comprises multiple scenarios, such as forward reaction prediction and structure elucidation from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra, where the question sets are finally collected. context of research, reasoning under imperfect evidence and iteratively refining hypotheses, not just answering isolated questions. 48 We introduce a systematic evaluation of LLMs grounded in real-world research scenarios for scientific discovery (named Scientific Discovery Evaluation, or SDE, Fig. 1c). Across four domains (biology, chemistry, materials, and physics), we start with concrete research projects of genuine interest to domain experts and decompose each into modular research scenarios, which are scientifically grounded and reusable across multiple applications. Within each scenario, we construct expert-vetted questions, formatted in line with conventional LLM benchmarks (multiple choice or exact match), such that their evaluation constitutes measurable progress toward in-context scientific discovery. deepseek-V3.1 accuracy deepseek-R1 accuracy Fig. 2 | Comparative performance of frontier language models across scientific domains. a. Distribution of per-domain accuracies for ten models on biology, chemistry, materials and physics. Box plots summaries aggregate scenario-level performance, where each scenario is represented as a dot. Mean and median accuracy are shown by diamond and solid line, respectively. The models are colored as the following: light purple for claude-opus-4.1 and claude-sonnet-4.5, coral red for deepseek-V3.1 and deepseek-R1, light blue for gpt-4o, gpt-5-chat, gpt-o3, and gpt-5, teal green for grok-3 and grok-4), with higher opacity for more recent release. b. Mean accuracy of gpt-5 on four domains of questions in SDE in comparison to select conventional benchmarks (GPQA-Diamond, MMMU, AIME-2025, SWE-bench Verified). c. Domain-averaged accuracy for deepseek-V3.1 and deepseek-R1 with biology in purple, chemistry in green, materials in orange, and physics in gray. d. Scenario-wise comparison of deepseek-R1 (y-axis) versus deepseek-V3.1 (x-axis). The dashed diagonal line denotes parity, with points above the line indicating scenarios where deepseek-R1 outperforms deepseek-V3.1. e. Accuracies for deepseek-V3.1 (red) and deepseek-R1 (indego) categorized by domains and scenarios. The horizontal line is colored as indigo when deepseek-R1 outperforms deepseek-V3.1, otherwise as red.

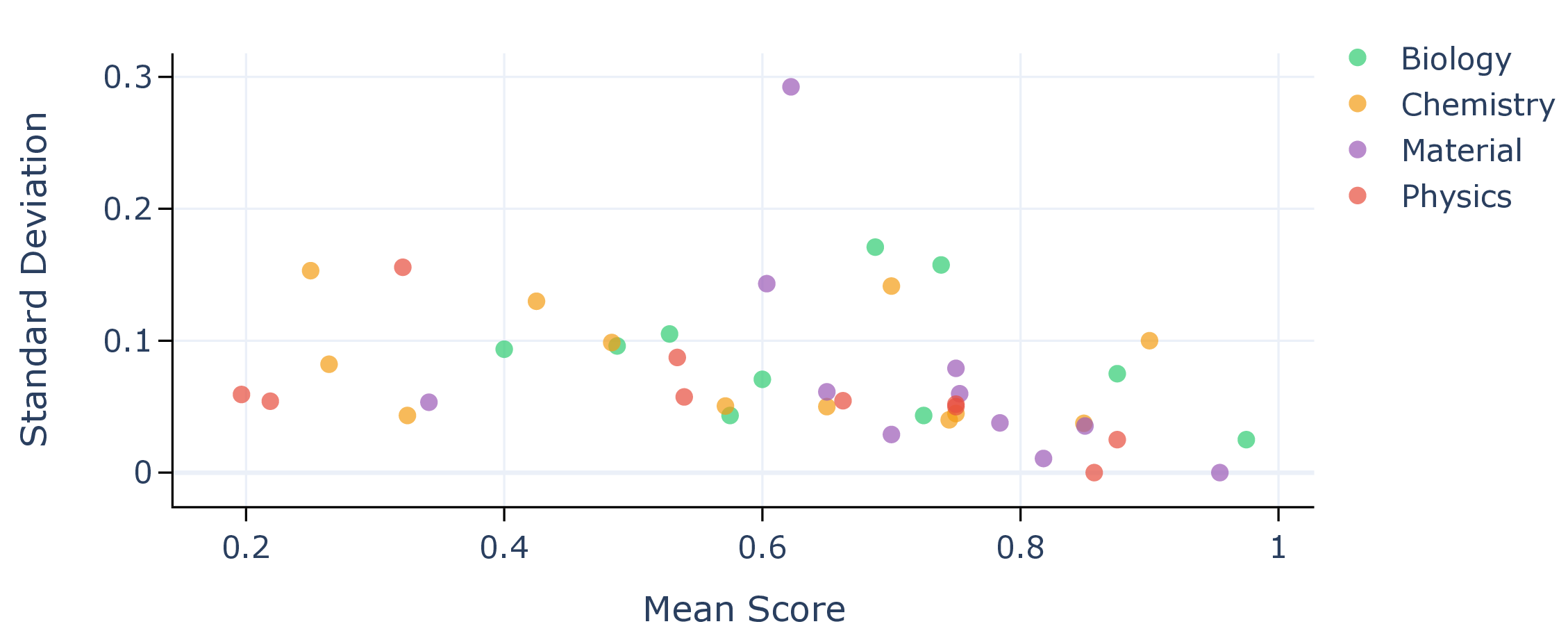

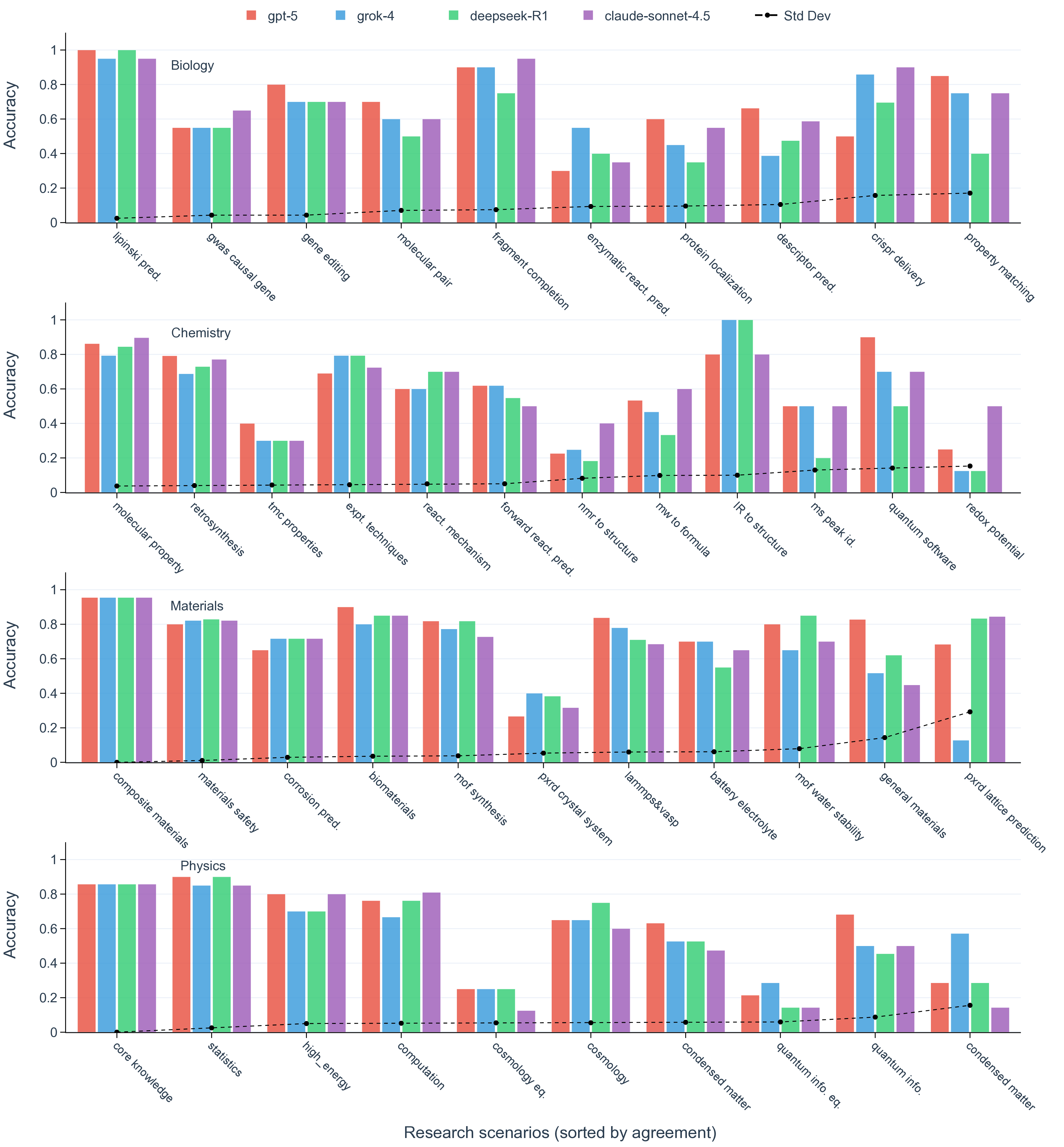

API on various task types 49 (see Methods section, Model evaluation). Among all LLMs, only deepseek-V3.1 and deepseek-R1 are fully open-weight. 15 Scores at each scenario, defined as percentages of questions that a model answered correctly, are aggregated per domain for all models evaluated (Fig. 2a). The performance varies drastically across different models, while in all domains with the latest flagship LLM from a commercial provider ranks the highest (Supplementary Fig. 1). To situate these results, we compare model performance on our discovery-grounded questions with widely used general-science Q&A benchmarks. On our SDE benchmark, state-of-the-art models reach a score of 0.71 in biology (claude-4.1-opus), 0.60 in chemistry (claude-4.5-sonnet), 0.75 in materials (gpt-5), and 0.60 in physics (gpt-5). By contrast, the same class of models attains 0.84 on MMMU-Pro and 0.86 on GPQA-Diamond (gpt-5), illustrating a consistent gap between decontextualized Q&A and scenario-grounded scientific discovery questions (Fig. 2b). In spite of the corpus-language effect that recent scientific literature is predominantly written in English, we find that deepseek-R1, as the representative of the strongest open-weight models, starts to approach the performance of top-tier closed-source LLMs, narrowing gaps that were pronounced only a few releases ago. This observation underscores the pace of community catching up on iterative improvement of training data, methodology, and infrastructure, thanks to the efforts in open source. 15,50 The performance of a model varies significantly across research scenarios (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 2). For example, gpt-5 achieves impressive performance in retrosynthesis planning (score of 0.85) while struggling with NMR structure elucidation (score of 0.23). This observation, as exemplified by the wide spectrum of accuracy in each domain, holds for all LLMs evaluated, reinforcing the fact that conventional science benchmarks that only categorize questions into domains or subdomains are insufficient to detail the fields of mastery and improvement for LLMs. This finer-grained assessment is important, as scientific discovery is often blocked by misinformation and incorrect decisions rooted in the weakest scenario. With the SDE benchmark, we establish a look-up table that assesses LLMs’ capability in specific research scenarios when people consider applying LLMs in their research workflows.

Reasoning and scaling plateau. On established coding and mathematics benchmarks, state-of-the-art performance typically progresses with model releases. Reasoning is a major driver of those gains, which matters no less in scientific discovery. 51,52 In the head-to-head comparisons of otherwise comparable models, variants with explicit test-time reasoning consistently outperform their non-reasoning counterparts on the SDE problems, best exemplified by the enhanced performance of deepseek-R1 compared to deepseek-V3.1, both sharing the same base model 15 (Fig. 2c). The effect holds across biology, chemistry, materials, and physics and across most of the scenarios, indicating that improvements in reasoning corresponding to multi-step derivation and evidence integration translate directly into higher accuracy in discovery-oriented settings (Fig. 2d). One salient example is to let LLMs judge whether an organic molecule satisfies Lipinski’s rule of five, a famous guideline for predicting the oral bioavailability of a drug candidate, where reasoning is expected to be vital (Fig. 2e). There, the accuracy boosts from 0.65 to 1.00 by turning on reasoning capability in DeepSeek models.

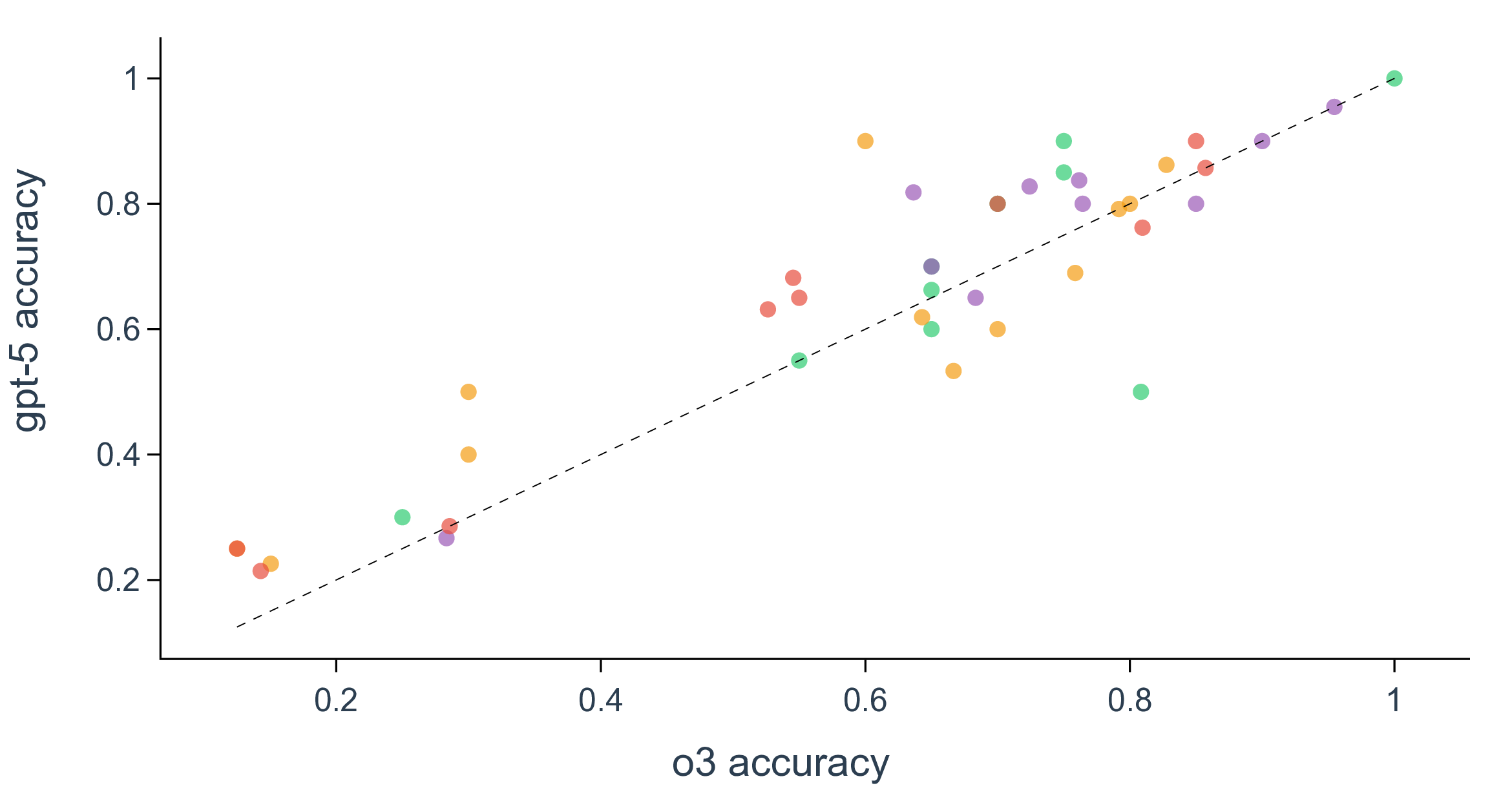

Yet, despite the clear benefits of reasoning, overall performance starts to saturate on our SDE benchmark when tracked across various reasoning efforts for gpt-5, where the gains become modest and often fall within statistically negligible margins, even when the corresponding models set new records on coding or math (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). For example, the accuracy barely improves between reasoning efforts of medium and high (0.70 vs. 0.69 in biology, 0.53 vs. 0.60 in chemistry, 0.74 vs 0.75 in materials, and 0.58 vs 0.60 in physics), indicating diminishing returns from the prevailing roadmap of increasing test-time compute for the purpose of scientific discovery (Supplementary Fig. 7). Besides reasoning, scaling up model sizes is considered as a huge contribution in the current success of LLMs. We indeed observe monotonic improvement in model accuracy as gpt-5 scales from nano to mini and to its default large size (Fig. 3b). However, the scaling effect may also have slowed down during the past year, as indicated by the marginal performance gain of gpt-5 over o3, even with 8 scenarios having significantly (i.e., with >0.075 accuracy difference) worse performance (Fig. 3c). Similarly, when the factor of reasoning being isolated, the performance improvement from gpt-4o to gpt-5 is also negligible, which indicates a seemingly converged behavior in discovery tasks for pretrained base foundation LLMs in the past 18 months. The implication of reasoning and scaling analysis is not that progress has stalled, but that scientific discovery stresses different competencies than generic scientific Q&A, such as problem formulation, hypothesis refinement, and interpretation of imperfect evidence.

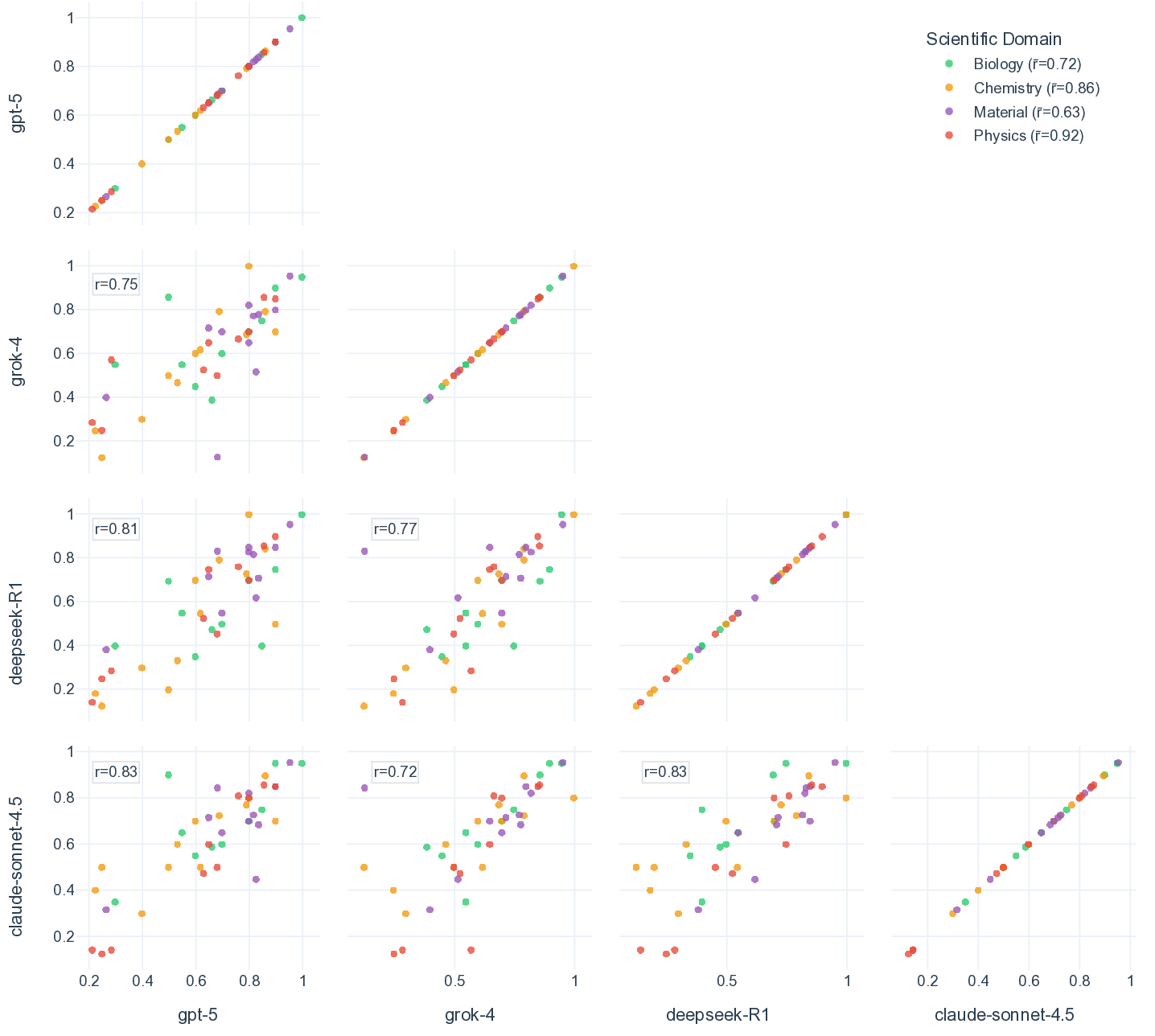

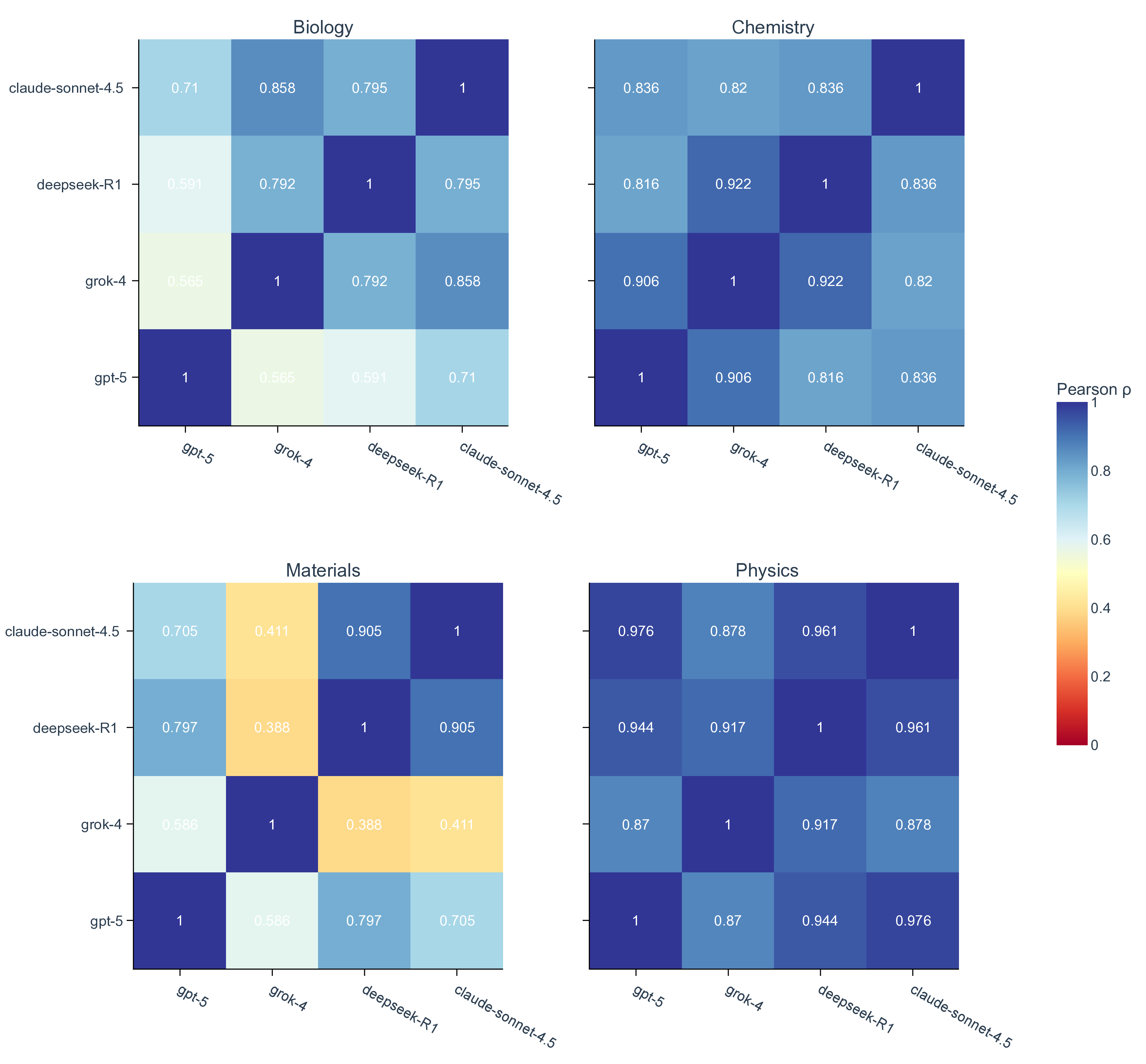

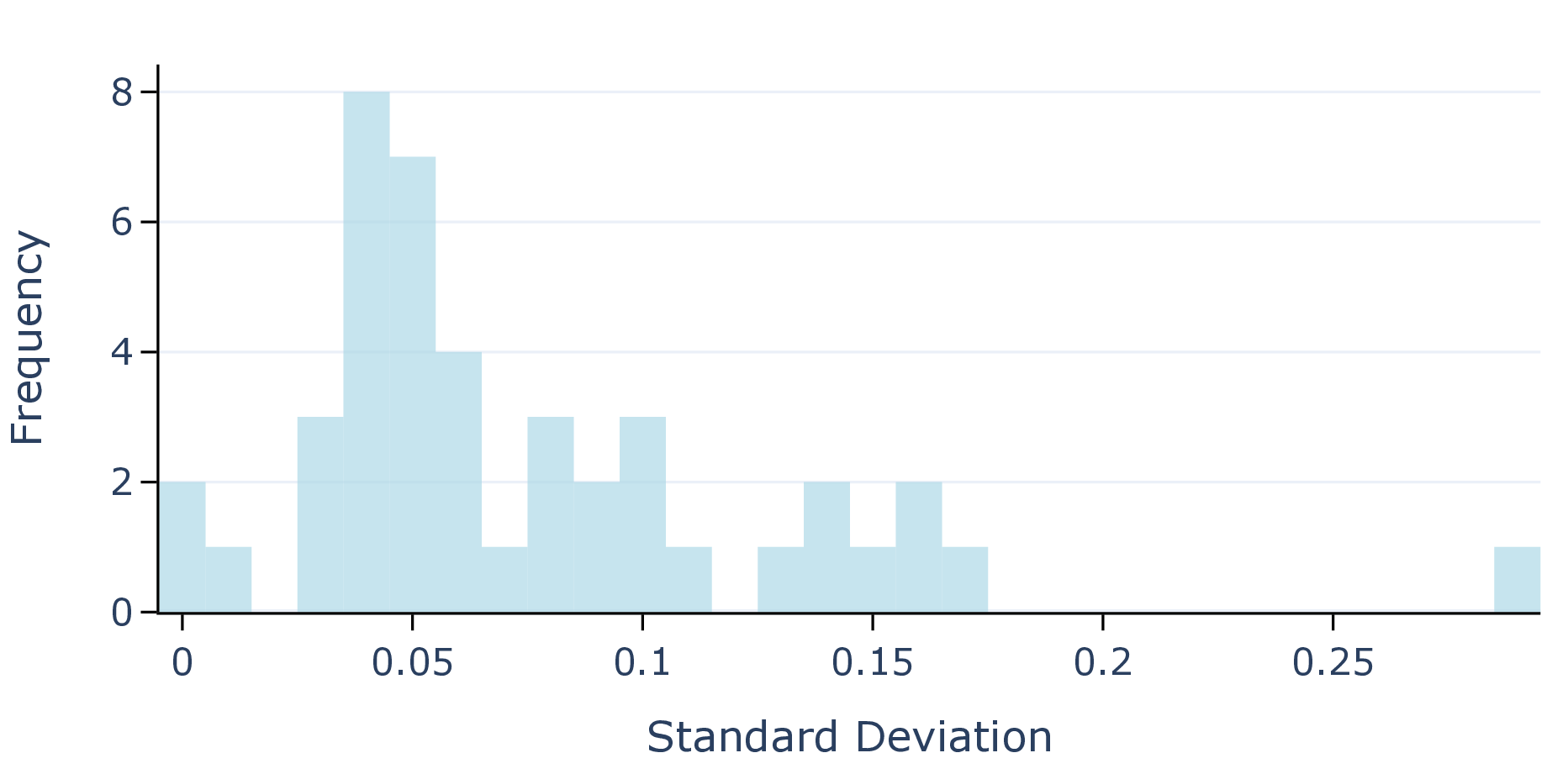

Shared failure modes among top-performing LLMs. When comparing the top performers across different providers (i.e., gpt-5, grok-4, deepseek-R1, and claude-sonnet-4.5), we observe that their accuracy profiles are highly correlated, which tend to rise and fall on the same scenarios (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. 5). This correlation is most prominent in chemistry and physics, where all pairwise Spearman’s r and Pearson’s r among the four top-performing models are greater than 0.8 (Supplementary Fig. 8). Moreover, top-performing LLMs frequently converge on the same incorrect set of most difficult questions, even when their overall accuracies differ (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 6). For example, despite a relatively high accuracy on MOF synthesis questions, the four models make the same mistake on four out of 22 total questions. This alignment of errors indicates that frontier LLMs mostly share common strengths as well as common systematic weaknesses, plausibly inherited from similar pre-training data and objectives rather than from their distinctive architecture and implementation details. 53 Practically, this means that naive ensemble strategies (e.g., majority voting across providers) may deliver limited improvement on scenarios and questions that are inherently difficult to current LLMs (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Fig. 9). Our scenario-grounded design makes these correlations visible and reproducible, which not only reveals where models overall succeed, but also in a finer-grained where and why they fail on discovery-oriented tasks, exposing shared failure modes across research pipelines (Supplementary Fig. 10).

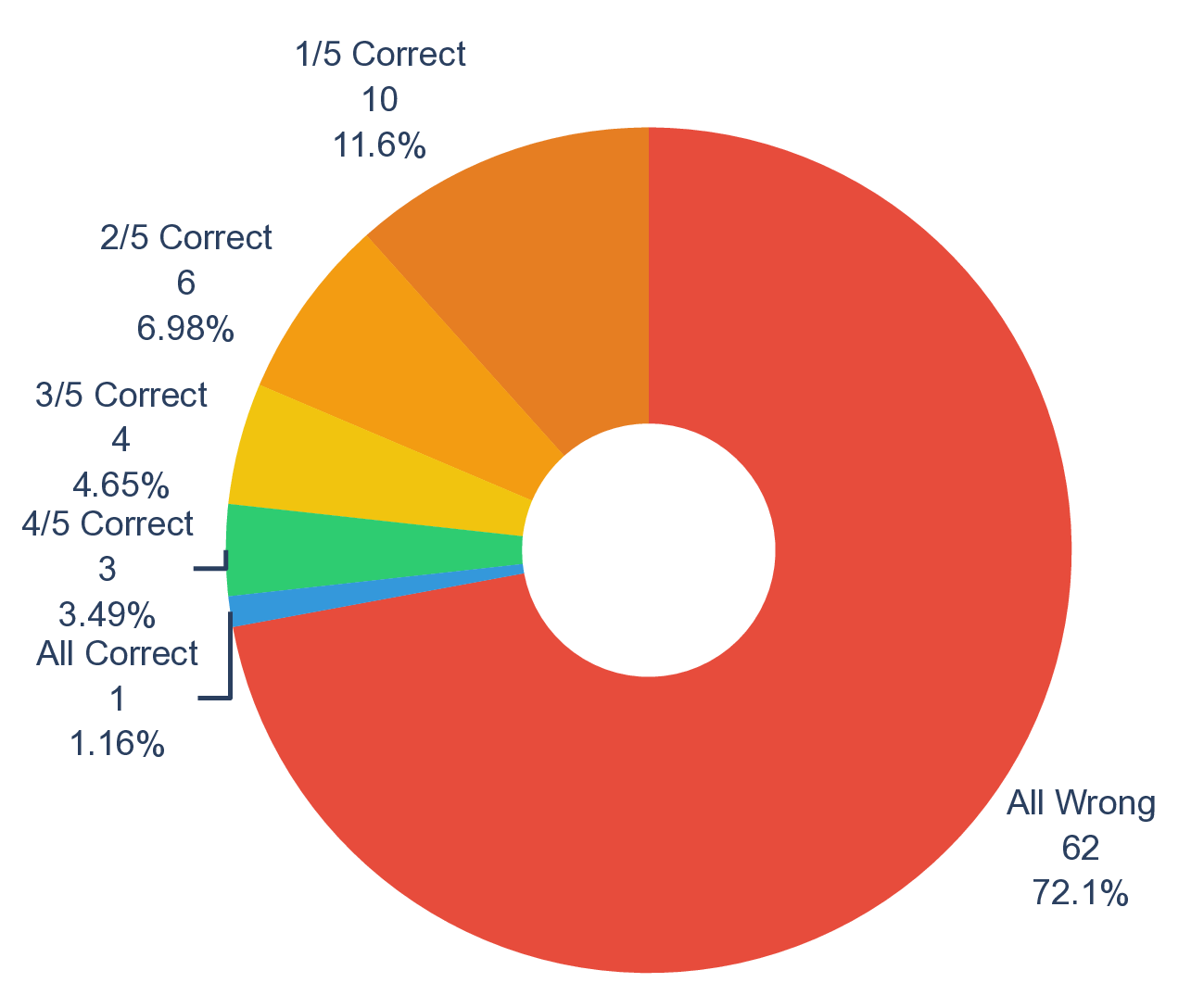

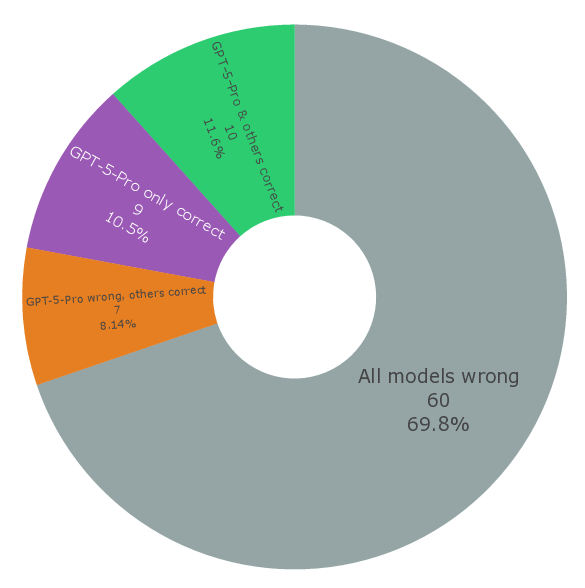

Seeing this consensus failing behavior on most difficult questions, we further collected 86 questions, 2 in each research scenario where the top-performing LLMs make most mistakes on, as a subset called SDE-hard (Fig. 3f).

All LLMs score less than 0.12 on these most difficult scientific discovery questions (Supplementary Fig. 11 and Fig. 12). Surprisingly, gpt-5-pro improves by a significant margin compared to gpt-5 and flagship models from other right). Each question is marked by its correctness (green dots for correct and red dots for incorrect), together with a doughnut plot for analysis of model consensus (bottom). f. Construction of sde-hard (top) and its corresponding model performance (bottom). For gpt-5-pro, the accuracy that considers seven questions with “no response” as incorrect is shown in solid and as correct in transparent.

providers. Despite its impeding (i.e., 12x higher) cost, gpt-5-pro gives correct response on 9 questions where all other models are incorrect (Supplementary Fig. 13). This observation suggests its competitive advantage on most difficult questions that require extended reasoning, which is characteristic in scientific discovery. This accuracy, however, still leaves much room to improve, which makes SDE-hard a great test suite for LLMs with high inference costs that would be released in the future.

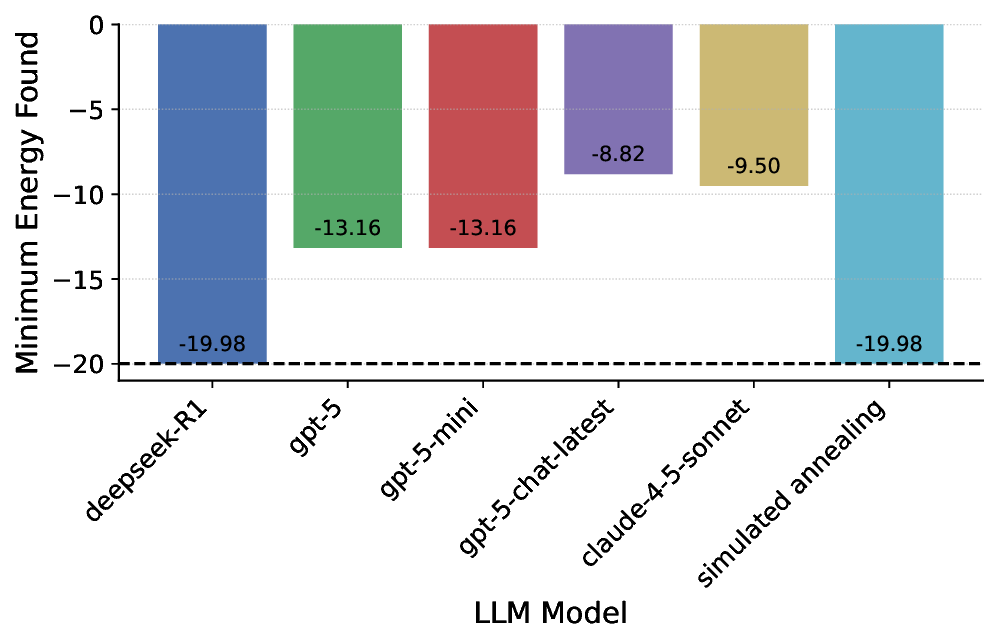

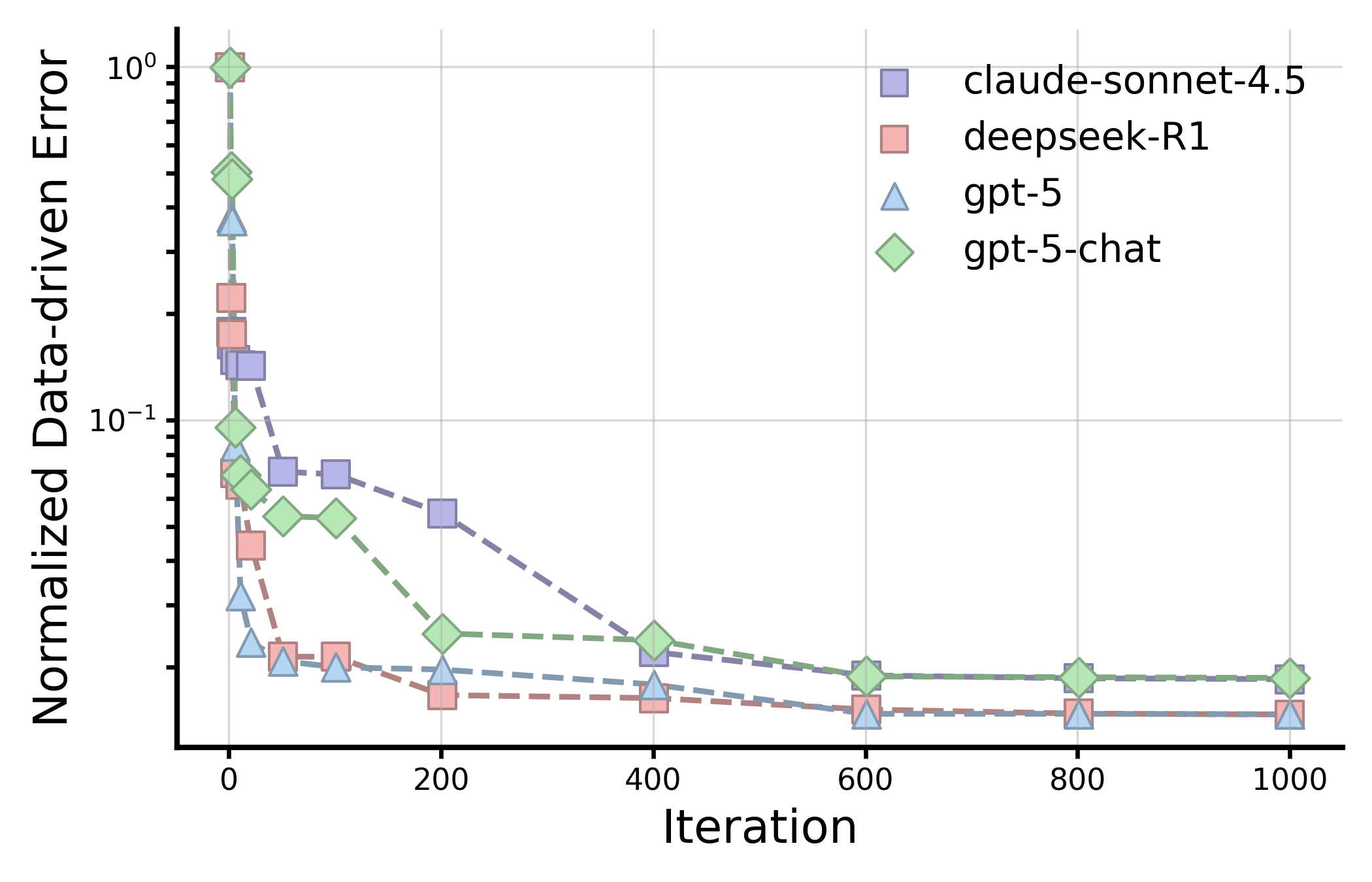

Establishing LLM evaluation on the scientific discovery loop. Conventional Q&A benchmarks typically evaluate models via single-turn interactions, scoring isolated responses to static queries. Scientific discovery, by contrast, advances through iterative cycles of hypothesis proposal, testing, interpretation, and refinement. 7 To mirror this process, we introduce sde-harness, a modular framework that formalizes the closed discovery loop of hypothesis, experiment, and observation, wherein the hypothesis is generated by an LLM rather than a human investigator (Fig. 4a and codified knowledge, such as protein design, transition metal complex (TMC) optimization, organic molecule optimization, crystal design, and symbolic regression, exhibit the most significant gains from LLM integration (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Text 3). In symbolic regression, for example, we evaluate LLMs on their ability to iteratively discover governing equations of nonlinear dynamical systems from data, a setting that requires both structured exploration of the hypothesis space and progressive refinement of symbolic forms. Across different LLMs, reasoning models exhibit more effective discovery dynamics (Fig. 4c ). In particular, deepseek-R1 and gpt-5 demonstrate faster convergence and consistently reach lower final errors than claude-sonnet-4.5 and gpt-5-chat-latest.

These models are able to make early progress in reducing error and continue to refine candidate equations over hundreds of iterations, indicating more reliable exploration-exploitation trade-offs in the symbolic hypothesis space (Supplementary Table 5). Although claude-sonnet-4.5 performs reasonably in-distribution, it exhibits slower convergence and higher residual errors, particularly in earlier stages of discovery. By comparison with PySR, 54 a widely used state-of-the-art baseline for symbolic regression, we observe a significant performance gap from LLM based approaches, where PySR achieves substantially lower accuracy and significantly higher NMSE, especially in the OOD regime (Supplementary Table 5). These results reflects LLM’s great capability in scenarios such as computation and statistics, and highlights a key advantage of LLM-guided discovery: the ability to propose based on knowledge, revise, and recombine symbolic structures in a globally informed and knowledgeable manner, rather than relying solely on pure local search over operators.

In the context of TMC optimization, gpt-5, deepseek-R1, and claude-sonnet-4.5 all demonstrate rapid convergence when asked to identify candidates with maximized polarisability. These models locate the optimal solution within 100 recommendations (fewer than 10 iterations) within a search space of 1.37M TMCs (Fig. 4b). Notably, claude-sonnet-4.5 exhibits superior convergence rates and robustness across varying initialization sets (Supplementary Text 3.3 and Figure 14). Regarding the exploration of the Pareto frontier defined by polarisability and the HOMO-LUMO gap, deepseek-R1 yields the most extensive and balanced distribution, effectively covering both the small-gap/high-polarisability and large-gap/low-polarisability regimes (Fig. 4b). In contrast, claude-sonnet-4.5 is significantly sensitive to the initial population, restricting its exploration primarily to the large-gap/high-polarisability region (Supplementary Fig. 15). In both scenarios, the non-reasoning model, gpt-5-chat-latest, exhibits suboptimal performance compared to its reasoning-enhanced counterparts, underscoring the critical role of derivation and multi-step inference in TMC optimization.

Connecting question-and project-level performance.

Performance on scenarios does not always translate to projects. A distinguishing feature of the SDE framework is its ability to bridge question-and project-level evaluations through well-defined research scenarios, enabling direct analysis of error propagation from Q&A to downstream discovery (Fig. 1c). Top-performing LLMs (e.g., gpt-5) excel at molecular property prediction, SMILES and gene manipulation, protein localization, and algebra. Consequently, they demonstrate strong performance in corresponding projects, including organic molecule optimization, gene editing, symbolic regression, and protein design (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Text 3). Although the ability of LLMs to generate three-dimensional crystal structures might be questioned given their lack of intrinsic SE(3)-equivariant architecture, we find that top-tier reasoning LLMs generate stable, unique, and novel materials that outperform many state-of-the-art diffusion models. This success mirrors their proficiency in related materials scenarios, such as PXRD lattice prediction (Supplementary Table 3). Conversely, unsatisfactory results across all models in quantum information and condensed matter theory translate directly to the project level: in solving the all-to-all Ising model, most models (with the exception of deepseek-R1) fail to surpass the evolutionary algorithm baseline (Supplementary Fig. 19).

Interestingly, we observe striking exceptions to the positive correlation between question-and project-level performance. For instance, while no model demonstrates high proficiency in TMC-related scenarios (e.g., predicting oxidation states, spin states, and redox potentials), gpt-5, deepseek-R1, and claude-sonnet-4.5 all yield excellent efficiency in proposing TMCs with high polarisability and exploring the Pareto frontier within a 1.37M

TMC space (Fig. 4b). This suggests that rigorous knowledge of explicit structure-property relationships is not a strict prerequisite for LLM-driven discovery. Rather, the capacity to discern optimization directions and facilitate serendipitous exploration appears more critical. Conversely, although top-performing LLMs score highly on questions regarding retrosynthesis, reaction mechanisms, and forward reaction prediction, they struggle to generate valid multi-step synthesis routes. Due to frequent failures in molecule or reaction validity checks, these models fail to outperform traditional retrosynthesis models on established benchmarks (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, gpt-4o, a relatively older model without test-time reasoning, achieves the best results in this project, surpassing both its direct successor (gpt-5-chat) and the reasoning-enhanced variant (gpt-5).

No single model wins on all projects. Across the eight projects, we observe no definitive hierarchy in model performance, where leadership rotates, with models excelling in certain projects while underperforming in others (Fig. 4a). This variability reflects the composite nature of scientific discovery, which integrates multiple interdependent research scenarios. Consequently, obtaining outstanding project-level performance requires, at least, proficiency across all constituent scenarios, as a deficit in any single component introduces compounding uncertainty. Moreover, the anticipated benefits of strong reasoning enhancements were notably absent in certain projects (such as retrosynthesis and protein design), where such capabilities were expected to be critical (Supplementary Text 3). This suggests that tailored post-training strategies are required to drive further improvements. Notably, the advantage of pre-training corpora appears less decisive in discovery projects than in static question-level evaluation. For instance, deepseek-R1, despite showing slightly weaker performance on question-level benchmarks, ranks within the top two across nearly all projects where reasoning is advantageous. Ultimately, all contemporary models remain distant from true scientific “superintelligence” as no single model excels in all eight (yet limited set of) projects on different themes of scientific discovery. To effectively orchestrate the loop of scientific discovery, future developments that prioritize balanced knowledge and learning capabilities across diverse scenarios over narrow specialization is desired.

The integration of large language models (LLMs) into scientific discovery necessitates an evaluation paradigm that transcends static knowledge retrieval. While conventional benchmarks have successfully tracked progress in answering general science questions, our results demonstrate that they are insufficient proxies for scientific discovery, which relies on iterative reasoning, hypothesis generation, and evidence interpretation. In the scientific discovery evaluation (SDE) framework, we bridge this gap by establishing a tight connection between all questions collected in the benchmark to modular research scenarios, which constitute building blocks in projects aimed for scientific discovery. There, models are not only evaluated on their ability to answer isolated questions, but also on their capacity to orchestrate the end-to-end research project. This dual-layered approach reveals critical insights into the readiness of current foundation LLMs for autonomous scientific inquiry.

Our question-level evaluation reveals that top-tier models, despite achieving high accuracy on decontextualized benchmarks (e.g., GPQA-Diamond), consistently score lower on SDE questions rooted in active research projects.

This divergence underscores that proficiency in standard examinations does not guarantee mastery of the nuanced, context-dependent reasoning required for scientific discovery. We observe that the gains from scaling model size and test-time compute, strategies that have driven recent breakthroughs in coding and mathematics, exhibit diminishing returns within the domain of scientific discovery. Furthermore, top-performing models from diverse providers exhibit high error correlations, frequently converging on identical incorrect answers for the most challenging questions. This shared failure mode suggests that current frontier models are approaching a performance plateau likely imposed by similar pre-training data distributions rather than distinct architectural limitations, thereby motivating the development of discovery-specific objectives and curated domain datasets. Project-level evaluation indicates that question-level patterns only partially predict discovery performance and that a model’s capacity to drive a research project relies on factors more complex than a simple linear correlation with its Q&A accuracy. This implies that precise knowledge of structure-property relationships may be less critical than the ability to navigate a hypothesis space effectively.

Specifically, discerning optimization directions and facilitating serendipitous exploration can compensate for imperfect granular knowledge. However, this capability is non-uniform: while LLMs excel at optimizing objectives involving well-structured data (e.g., TMC optimization), they struggle with endeavors requiring rigorous, long-horizon planning and strict validity checks, such as retrosynthesis. Collectively, these findings highlight the distinct competencies assessed at each evaluation level, underscoring the necessity of comprehensive, multi-scale benchmarking.

Based on these findings, we identify several directions for advancing the utility of LLMs in scientific discovery.

First, shifting focus from indiscriminate scaling to targeted training on problem formulation and hypothesis generation could bridge current gaps in scientific methodology. Second, pronounced cross-model error correlations underscore the urgent need to diversify pre-training data sources and explore novel inductive biases to mitigate shared failure modes. Third, the integration of robust tool use in fine-tuning is essential, as many of the most challenging research scenarios necessitate a tight coupling between linguistic reasoning and domain-specific simulators, structure builders, and computational libraries. Consequently, training and evaluation paradigms must expand beyond textual accuracy to prioritize executable actions-specifically, the capacity to invoke tools, debug execution failures, and iteratively refine protocols in response to noisy feedback. Finally, given that reasoning enhancements optimized for coding and mathematics yielded negligible gains in many discovery-type projects, developing reinforcement learning strategies tailored specifically for scientific reasoning represents a promising frontier.

Current SDE encompasses four domains, eight research projects, and 43 scenarios curated by a finite cohort of experts. Consequently, the benchmark inherently reflects the specific research interests, geographic distributions, and methodological preferences of its contributors. While disciplines such as earth sciences, social sciences, and engineering are currently unrepresented, the modular architecture of our framework allows for their seamless integration. Furthermore, reliance on commercial API endpoints introduces unavoidable performance fluctuations due to provider-side A/B testing. To mitigate this reproducibility challenge, the only solution would be local deployment of open-source models as a critical baseline, enabling independent replication and rigorous ablation free from access constraints. Additionally, high computational costs limited our project-level evaluation to a subset of frontier models, assessed using a single evolutionary search strategy and prompting protocol. Future research should expand this scope to include alternative optimization algorithms and agentic frameworks, particularly as domain-specific reasoning and tool use are integrated into reinforcement fine-tuning pipelines. Lastly, we shall not overlook the safety risks posed by increasingly capable biological AI systems. Recent efforts, such as built-in safeguard proposals, broader biosecurity roadmaps, jailbreak/red-teaming/watermark techniques and analyses, highlight early steps toward understanding misuse pathways. 55 Despite these constraints, SDE delivers the first integrated assessment of LLM performance across the scientific discovery pipeline, providing a robust scaffold upon which the community can build increasingly complex and realistic evaluations.

Research scenario and question collection. We organized the collection of research scenarios and corresponding questions through a structured, hierarchical collaboration across four scientific domains: biology, chemistry, materials, and physics. Each domain was led by a designated group lead with expertise in both scientific field and LLM-based benchmarking (see Author Contribution section). Contributors were grouped by domain according to their research background.

Each domain group first identified research scenarios that capture recurring and foundational reasoning patterns in realistic scientific discovery workflows. These scenarios were drawn from ongoing or past research projects and reflect active scientific interests rather than textbook exercises. A “scenario” is defined as a modular, self-contained scientific reasoning unit (e.g., forward reaction prediction in chemistry) that can contribute toward solving one or more research projects. Once the domain coverage and key scenarios were defined, contributors were assigned to specific topics based on their expertise to develop concrete question sets under each scenario.

Question generation followed a hybrid strategy combining semi-automated and manual curation. When feasible, questions were derived semi-automatically by sampling from existing benchmark datasets (e.g., GPQA) or openaccess datasets (e.g., NIST) and converting structured entries into natural-language question-answer pairs using template scripts. In some cases, domain-specific computational pipelines were used to obtain reference answers. For instance, some molecular descriptors are computed with RDKit. 56 For scenarios lacking structured public records, such as experimental techniques, questions were manually written by domain experts using unified templates to ensure consistency with semi-automated questions. They were subsequently reviewed by the group leads for clarity and relevance.

To mitigate random variance, each scenario contained at least five validated questions. Question formats included multiple-choice and short-answer types, evaluated through exact-match accuracy, threshold-based tolerance, or similarity scoring to ensure compatibility with automated evaluation pipelines. In this way, ambiguity in scoring the final answers from LLMs is avoided.

The resulting dataset spans four domains with 43 distinct scenarios and 1,125 questions, as summarized below (the number of questions in each scenarios is in parenthesis):

• Chemistry (276): includes forward reaction prediction (42), retrosynthesis (48), molecular property estimation (58), experimental techniques (29), quantum chemistry software usage (10), NMR-based structure elucidation (31), IR-based structure elucidation (5), MS peak identification (10), reaction mechanism reasoning (10), transition-metal complex property prediction (10), redox potential estimation (8), and mass-to-formula conversion (15).

• Materials ( 486 • Physics (163): includes astrophysics and cosmology (28), quantum information science (36), condensed matter physics (26), high-energy physics (20), probability and statistics (25), computational physics (21), and core physics knowledge (7).

Detailed documentation of dataset sources, question templates, prompt formats and evaluation protocols for all scenarios are accessible in Data Availability section. Detailed curation procedures and representative example questions are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Research project collection. We curated eight research projects across biology, chemistry, materials, and physics, each involving multiple modular research scenarios (Supplementary Table 6). For example, a project for retrosynthesis path design would naturally involves scenarios of single-step retrosynthesis, reaction mechanism analysis, and forward reaction prediction, among many others. Each research project was formulated as a search or optimization problem following the scientific discovery loop, using LLMs as proposals over a hypothesis space (e.g., the space of all possible molecular structures, symbolic equations). These hypotheses were then examined by computational oracles to access the fitness, which were then fed into LLMs to refine their proposals. Without loss of generality, we chose evolutionary optimization as a simple yet efficient search approach. The evolutionary optimization for each project followed a general workflow: (1) initialization: the process was initialized with a set of hypotheses (cold-start generation from

LLMs or warm-up from a predefined set), ( 2 Project-level.-All evaluations for research projects in SDE were performed using sde-harness. 67 We aggregated the performance for each project into a single score, normalizing the scale of each sub-objectives, and averaged the performance across sub-objectives to obtain a single score (Fig. 4a). Considering the cost of evaluating projects is much higher than that of questions, all projects are only evaluated on gpt-5-chat-latest, gpt-5, claude-sonnet-4.5, and deepseek-R1, with both best non-reasoning and reasoning models tested. Details for each project are described in Supplementary Sec. 3.

• Question-level resources:

-Datasets.

This section describes the task-specific curation procedures for the chemistry domain in the SDE benchmark. The chemistry subset comprises 276 questions spanning twelve distinct task types, designed to reflect recurring reasoning patterns in both wet-lab and dry-lab chemical research. Question construction followed a hybrid strategy combining semi-automated generation from public resources with manual expert curation for scenarios lacking structured records. Representative example questions illustrating these task formats are provided in Representative example questions.

Forward reaction prediction (42) Questions for forward reaction prediction were sourced from two parts. A subset was adapted from existing benchmark-style questions (e.g., GPQA), while others were sampled from the USPTO reaction dataset covering diverse reaction classes. Reaction entries were filtered to retain single-step transformations with unambiguous reactant-product mappings. Structured reaction records were then converted into natural-language multiple-choice questions using standardized templates. Additional questions were manually curated based on real-world wet-lab scenarios to capture practical reaction reasoning beyond dataset distributions.

Retrosynthesis (48) Retrosynthesis questions were derived from both benchmark-style sources and template-based sampling from USPTO (USPTO_TPL 68 ). For the latter, we used known reaction templates as a reference for what constitutes a chemically reasonable retrosynthetic step. Given a target molecule, we identified which types of bond disconnections are consistent with known reaction pattern. We then formulated multiple-choice questions in which chemically reasonable disconnections served as correct answers, while implausible or poorly motivated disconnections-drawn from unrelated reaction patterns were used as distractors.

Molecular property estimation (58) Molecular property questions were constructed using a mixture of benchmarkderived examples and molecules sampled from the ZINC database. Molecules were represented using SMILES or IUPAC names. Reference properties-including logP, topological polar surface area (TPSA), number of rotatable bonds, ring counts, molecular weight, and Tanimoto similarity-were computed using RDKit. Questions were framed to require comparative or ordering-based reasoning (e.g., ranking molecules by a given property).

NMR-based structure elucidation (31) NMR structure elucidation questions were manually curated from real experimental scenarios and published supplementary information. Each question provides molecular formulae and multi-modal spectroscopic data (¹H NMR, ¹³C NMR, and occasionally MS), requiring models to infer the complete molecular structure. Reference answers are represented as SMILES strings. During evaluation, predicted and reference structures are canonicalized using RDKit and scored via Tanimoto similarity between Morgan fingerprints, allowing partial credit for near-correct structures.

Redox potential estimation ( 8) Redox potential questions were curated from published electrochemical studies. Given the three-dimensional structure of a photocatalyst or metal complex, models are asked to predict the reduction potential relative to a specified reference electrode. Answers are numeric and evaluated using a task-specific tolerance band (0.25) around the reference value, reflecting experimental uncertainty.

Experimental techniques (29)/Quantum chemistry software usage (10)/Reaction mechanism reasoning (10)/MS peak identification (10)/IR-based structure elucidation (5)/Transition-metal complex property prediction (10)/Mass-to-formula conversion (15) Questions were entirely manually curated by domain experts. These questions were inspired by real world wet-lab/dry-lab experimental procedures or literature. All questions are formulated as either short answers or multiple-choice problems, and answers were evaluated with exact match accuracy.

This section provides representative example questions for selected tasks described in previous sections, illustrating the diversity of question formats, reasoning requirements, and evaluation protocols used in SDE.

The LLM proposes a route following the desired data format. If the first step of the proposed route fails, the LLM is prompted to propose another route.

In the case that an LLM-proposed reaction template does not exist in the reaction database, a difference fingerprint (RDKit’s CreateDifferenceFingerprintForReaction) is created for the proposed reaction and similar reactions are retrieved from the reference USPTO database. These retrieved reactions are applied and the first one that results in valid reactants is selected. If no valid reaction is found, then a reaction template is selected based on Tanimoto similarity to the target molecules present in the USPTO database. Following the original work, 10 total initial valid routes are generated.

Mutation. The Mutation phase refines the population of initial routes. One parent route is selected and the nonpurchasable intermediate molecules are identified (e.g. molecules that are a result of applying a reaction template but are not commercially available so must be decomposed further). Using the same Tanimoto similarity comparison to the USPTO reference database, routes of similar targets are retrieved. The LLM is then tasked to propose a modified route given these reference routes and feedback on current problems in the parent route (which is one of the initial routes generated in the initialization phase). If the LLM successfully proposes valid steps in the synthesis route, these steps are appended to the parent route and the full route (so far). This “full” route may still have problems which can then be iterated on in the next mutation trial. All routes in the population are scored with a combination of the synthetic complexity (SC) 71 and synthetic accessibility (SA) 72 scores for the non-purchasable intermediates. The 10-best scoring routes are kept before beginning a new mutation round. The entire search process terminates when either a valid synthesis pathway is found or the LLM budget is exhausted (in this work, we allow 100 LLM queries), whichever occurs first. The evaluation runs the LLM framework on prescribed sets of target molecules and reports the number of molecules that return a valid synthesis route, within 100 LLM queries (i.e. the solve rate).

Results. Using the Pistachio Hard 73 benchmark set of 100 molecule targets, we evaluated the solve rate using multiple LLMs and compared to common methods spanning MCTS 74 and Retro* 57 search Table 1. Overall, the LLMs’ performance is competitive with baselines with an explicit search algorithm. The results show the feasibility of using the LLM itself for retrosynthetic planning, replacing the search algorithm. We note however, that the results were only run for one replicate due to computational cost (newer LLMs are notably more expensive than its predecessors). Interestingly, GPT-4o outperformed all newer models which empirically struggled more to generate valid routes. Specific failure modes include outputting routes that do not conform to the desired route data format and/or violating the molecule or reaction validity checks.

We evaluated the molecule optimization task targeting two objectives, jnk3 and gsk3β. Each experiment began with an initial population of 120 molecules sampled from the ZINC dataset. In each generation, two parent molecules were drawn from the current population with probability proportional to their fitness. For LLM-based methods, mutation and crossover were implemented by prompting the model with one or two parent molecules and asking it to propose a new molecule, either by mutating a single parent or recombining both. This procedure was repeated until 70 offspring were generated. All offspring were evaluated by the oracle, and the union of parents and offspring was re-ranked by fitness; the top-120 molecules were retained as the population for the next generation. We capped the total number of oracle calls at 10,000 and applied early stopping: if the mean fitness of the top-100 molecules failed to improve by at least 10 -3 over 5 consecutive generations, the run was terminated. Methods were compared using the area under the curve of the top-k average objective versus the number of oracle calls (AUC top-k ) with k = 10, which jointly captures optimization quality and sample efficiency.

The quantitative results for both objectives are reported in Table 2. For non-LLM baselines, Graph GA is consistently weaker than learning-based approaches, especially on jnk3, while REINVENT provides a strong and stable reference across tasks. This highlights the advantage of specialized molecular generative frameworks for property-driven optimization.

Among LLM-based methods, GPT-4o performs competitively on both objectives, matching REINVENT on jnk3 and remaining close on gsk3β. Claude Sonnet 4.5 achieves the best overall performance across both tasks, with the highest AUC Top 10 on jnk3 and a particularly strong result on gsk3β, suggesting that both optimization efficiency and final top-k quality benefit from strong generative priors and effective exploration. DeepSeek-R1 remains competitive but shows a larger gap on gsk3β in terms of Avg Top 10, indicating that maintaining high-quality top candidates may be more sensitive to model-specific generation behavior for this objective.

In contrast, GPT-5 and GPT-5-chat underperform on jnk3, showing noticeable drops in both AUC Top 10 and Avg Top 10. On gsk3β, they improve substantially (e.g., GPT-5 Avg Top 10 0.942), but still lag behind the best-performing models in sample efficiency. Consistent with our empirical observations, GPT-5 tends to propose molecules with a higher duplication rate, which reduces effective exploration of chemical space and can disproportionately hurt AUC-based metrics, even when the final top-k set is reasonably strong. This comparison is also affected by an unavoidable decoding mismatch: GPT-5 and GPT-5-chat can only be run with temperature = 1.0, whereas all other LLMs are evaluated with temperature = 0.8. As a result, the observed gaps may reflect a combination of model behavior and sampling differences, rather than the reasoning-oriented design of GPT-5 alone.

Table 2. Performance comparison of different models on molecule optimization tasks (jnk3, gsk3β). All LLM models were tested with temperature = 0.8 and max_tokens = 8192 except for GPT-5 and GPT-5-chat.

In each iteration, a prompt is meticulously crafted, comprising generic instructions alongside specific information, constraints, and objectives, and is then presented to an LLM to be evaluated. The reference data as the input into the model through carefully constructed prompts containing: (1) a pool of 50 ligands represented by their SMILES strings, IDs, charges, and connecting atom information; (2) 20 randomly sampled initial TMCs from a space of 1.37M possible Pd(II) square planar complexes, along with their pre-calculated properties (HOMO-LUMO gap and polarisability); and (3) natural language descriptions of the design objectives (e.g., maximizing HOMO-LUMO gap). The LLM subsequently proposes a new set of TMCs, which undergo a rigorous validation process including charge constraints (-1, 0, or +1), structure generation using molSimplify, 78 geometry optimization with GFN2-xTB, and connectivity validation to ensure no unintended bond rearrangements occur. Valid TMCs and their calculated properties are integrated into the prompt for the subsequent iteration, effectively completing the scientific discovery loop. Specifically, we start with 20 initial TMCs, with the LLM proposing 10 new TMCs at each iteration until a maximum iteration of 20 is reached. All TMCs explored during the optimization process, regardless of their fitness values, are included in the prompt for the next iteration. This mimics the human learning experience where one can learn from both good and bad examples. To prevent the LLM from overemphasizing specific records, the historical TMC data within the prompt is randomly shuffled before each iteration. To minimize bias from the initial TMC sampling, five random seeds are used to sample the initial known TMCs.

In the first task of proposing TMCs with maximized polarisability, gpt-5, deepseek-R1, and claude-sonnet-4.5 successfully finds the optimal solution in the space of 1.37M TMCs at all five random seeds (Fig. 14). On the contrary, gpt-5-chat-latest fails to do so in all five random seeds, showing the significance of reasoning capability in TMC optimization. Across three reasoning models, claude-sonnet-4.5 demonstrates quicker convergence through iteration compared to gpt-5 and deepseek-R1 consistently. A similar trend is observed when models are asked to expand the Pareto frontiers by proposing TMCs (Fig. 15). There, gpt-5-chat-latest still finds the most limited Pareto frontiers, hardly identifying TMCs with polarsability > 400 a.u. and HOMO-LUMO gap > 4 eV. Out of the three reasoning models, deepseek-R1 gives the most expanded and balanced Pareto frontiers. It should be noted that the influence of random seed is significant, which leads to different sets of TMCs found as Pareto frontiers. claude-sonnet-4.5 is impacted the most by random seeds, and only explore TMCs locally at seed 68, 86, and 1234. gpt-5, despite not yielding the best combined Pareto frontiers across all models, follows the instruction clearly and attempts a balanced exploration at all random seeds. gpt-5-chat-latest is colored in green, gpt-5 in blue, deepseek-R1 in red, and claude-sonnet-4.5 in purple, with reduced transparency as iteration number increases.

Each experiment began with an initial population of 100 groups of parents (100 × 2 = 200 parent structures), randomly seeded from the reference pool, which is composed with 5,000 known stable structures from MatBenchbandgapt 79 dataset with lowest deformation energy evaluated by CHGNet. 80 The mutation and crossover operations for LLMs were implemented by prompting the LLMs with two sampled parent structures based on their fitness values (minimizing E d ) and querying them to propose 5 new structures either through mutation of one structure or crossover of both structures. After generating new offspring in each generation, we evaluated the new offspring and merged their evaluations with the parent evaluations from the previous iteration. The merged pool of parents and children were then ranked by their fitness values (minimizing E d ), and the top-100 × 2 candidates were kept in the population as the pool for the next iteration. We evaluate generated structures through metrics that assess validity, diversity, novelty, and stability. Structural validity checks three-dimensional periodicity, positive lattice volume, and valid atomic positions. Composition validity verifies positive element counts and reasonable number of elements (≤ 10).

Structural diversity is computed by deduplicating the generated set using pymatgen’s StructureMatcher algorithm, then calculating the ratio of unique structures to total generated. Composition diversity measures the fraction of distinct chemical compositions. For novelty assessment, we compare generated structures against the initial reference pool.

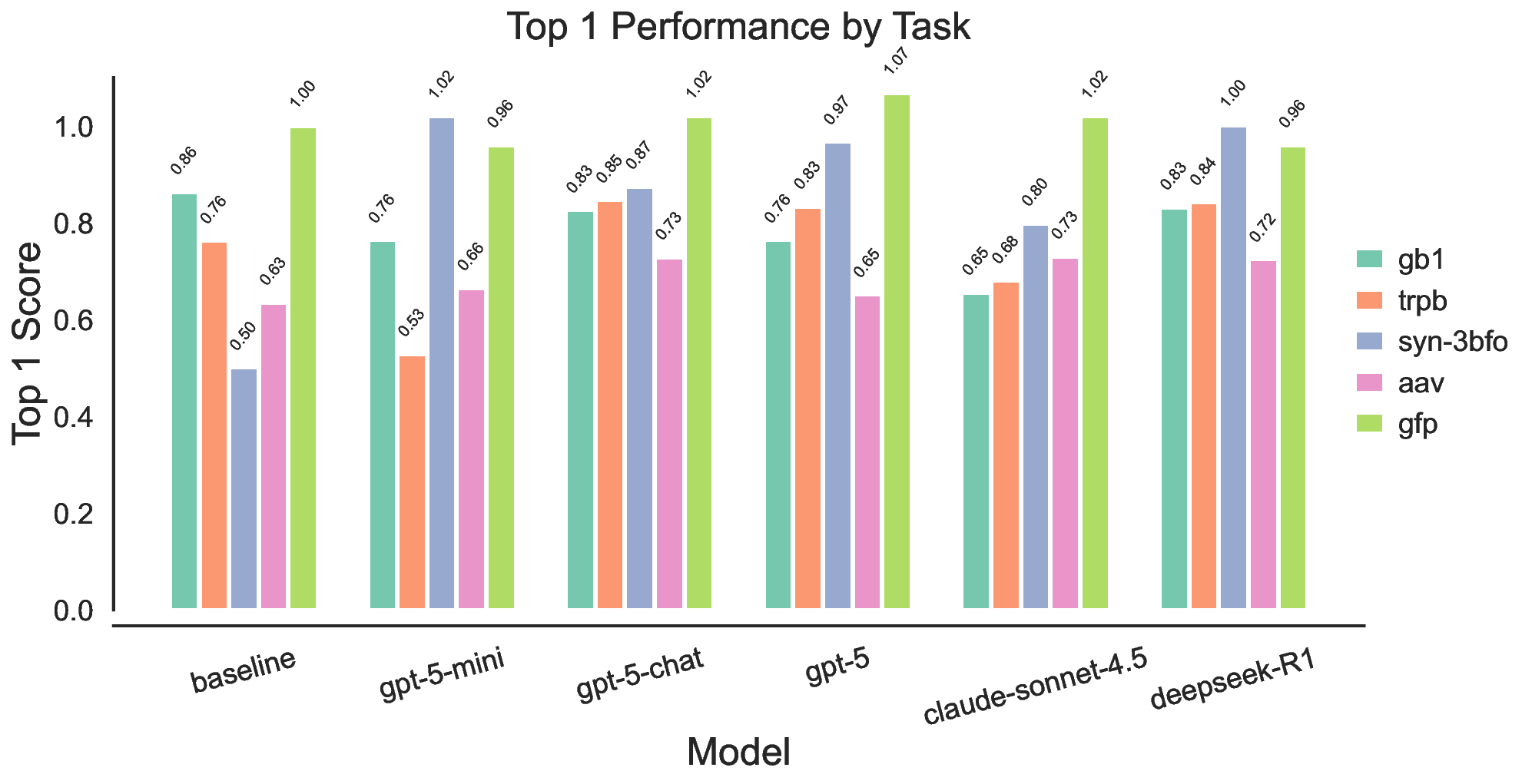

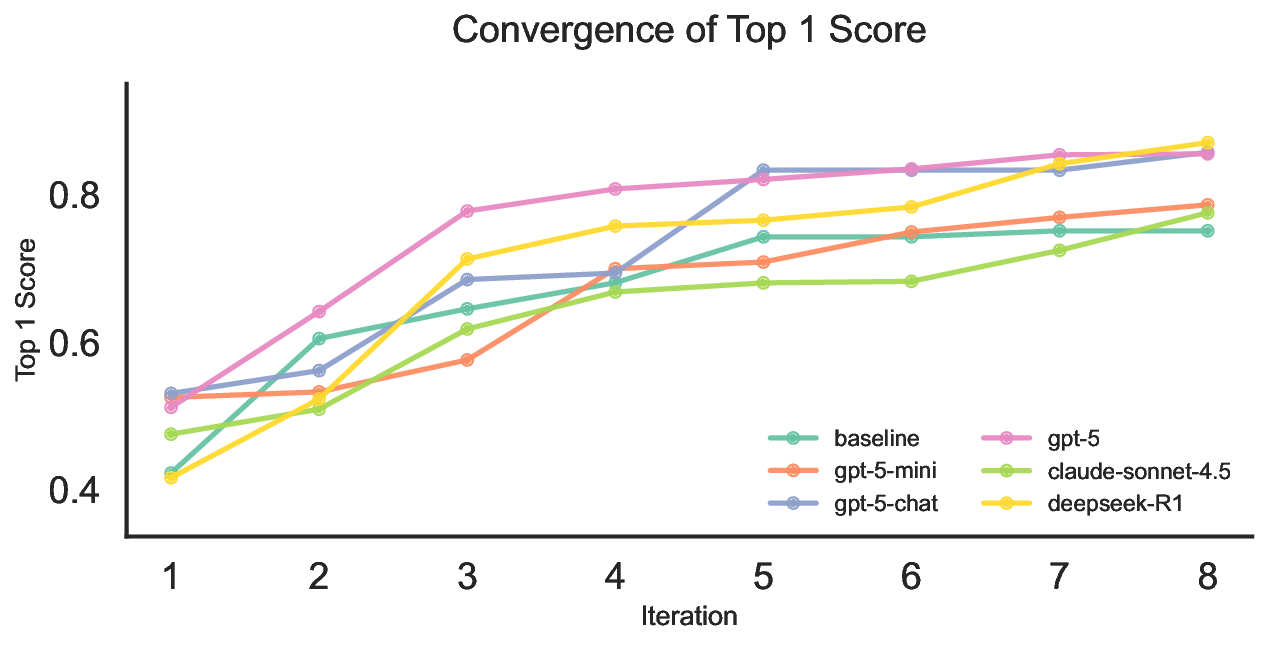

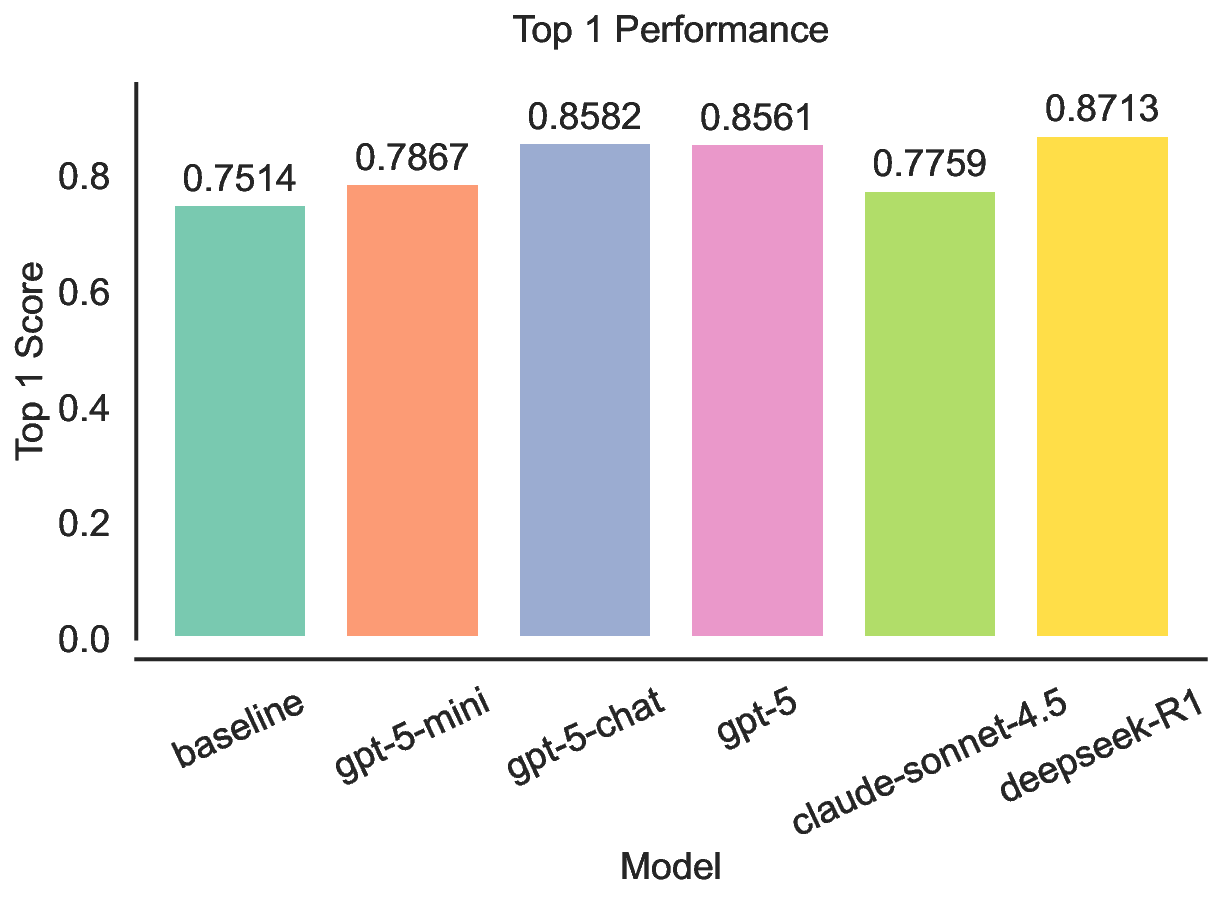

Each experiment began with an initial population of 200 sequences, seeded with one experimentally defined wild-type sequence and 199 additional variants generated by single-site random mutations of the wild type sequence. The mutation and crossover for LLMs were implemented by prompting the LLMs with two sampled parent sequences based on their fitness values and querying it to propose a new sequence either through mutation of one sequence or crossover of both sequences. When we turned fitness values into probabilities to sample parents, we first normalized the fitness values to ensure non-negativity and then divided by the sum to obtain probabilities. We also applied a small shift to ensure the pool was not dominated by one candidate. After generating 100 new offspring in each generation, the new pool including the offspring and the parents were re-ranked by the fitness values and the top-200 candidates were kept in the population as the pool for next iteration. This process was repeated for 8 iterations. We reported the fitness values of the top 1 candidates, normalized with their (min, max) score range specific to each dataset. For GB1 83 and TrpB, 84 the range was computed directly from the experimentally measured fitness values in their respective benchmark datasets. For the ML-based oracles (GFP 85 and AAV 86 ), the (min, max) values were taken from the corresponding oracle’s training data to maintain consistency with its predictive scale. 87 For the synthetic Potts-model landscape (Syn-3bfo), the range was fixed to the most frequent region (min, max) = (-3, 3). We validated and compared the performance of LLMs against a simple evolutionary algorithm with identical initial populations and hyperparameters. The mutation operator in the baseline was a single-site mutation with a fixed probability of 0.3. Once triggered, a mutation site was chosen at random and flipped to another random amino acid. The crossover operator in the baseline was implemented by selecting two parents based on their fitness values and a crossover site at random, then swapping the prefix and suffix of the two sequences. Beyond the aggregated ranking, the gains are concentrated on the more challenging landscape: on Syn-3bfo, all LLM-guided variants substantially exceed the baseline, with improvements ranging from 59.5% to 103.8%, suggesting that LLM-driven mutation and crossover better navigate fitness landscapes with strong interaction effects between mutation sites, leading to rugged regions where simple local operators struggle. In contrast, results on GB1 and GFP show limited and sometimes mixed gains. For GB1, the effective search space is small and the baseline already performs strongly, leaving little headroom and making the outcome sensitive to whether proposals preserve the few critical sites. For GFP, performance is near saturation for several methods, so differences tend to be smaller and can vary by model. Finally, the mid-tier models show reduced robustness across tasks, most notably gpt-5-mini, which performs competitively on some benchmarks yet drops sharply on TrpB, whereas gpt-5-chat exhibits the most consistent performance across tasks. Overall, these results suggest that LLM-based search is most valuable for harder search regimes, while robustness across diverse fitness landscapes remains an important consideration.

The convergence curves in Figure 16 show a common pattern across methods: rapid gains in the first few iterations followed by slower, diminishing improvements as the search concentrates around strong candidates. gpt-5 makes the largest early jump within the first three iterations, suggesting it proposes high-quality mutations or crossovers with fewer oracle evaluations. deepSeek-R1 improves more gradually but continues to climb in later iterations, which points to stronger stability during refinement rather than relying on a single early leap. gpt-5-chat displays a clear improvement around iterations 4 to 5, consistent with moving from initial exploration into a more effective search regime, and it ultimately approaches the top-performing methods. By contrast, gpt-5-mini and claude-sonnet-4.5 increase more slowly and level off earlier at lower scores, indicating less effective candidate proposals under the same evaluation budget. Overall, the curves suggest that differences arise from both final performance and optimization dynamics, including how quickly a model finds good regions and how reliably it improves thereafter. 62

We assess model performance using data from past genetic perturbation experiments. We simulate the perturbation of a gene g by retrieving the relevant observation of the perturbation-induced phenotype f(g) from this dataset. In every experimental round we perturb 128 genes at a single please, representing a reasonably sized small-scale biological screen. Five rounds of experiment are performed with all historical observation fed into the prompts for the next round. We use Interferon-γ (IFNG) dataset, which measures the changes in the production of a key cytokine involved in immune signaling in primary human T-cells. Across all models, gpt-5 and claude-sonnet-4.5 perform similarly well, reaching the same number of total hits with the only difference that gpt-5 sometimes generates invalid perturbations. Meanwhile, deepseek-R1 generates fewer hits compared to the two best models. gpt-5-chat, despite having much fewer total hits, reaches the best final efficiency as many of genes generated there are invalid and thus would not be tested explicitly in labs. leading evolutionary symbolic regression by leveraging global structural priors and iterative hypothesis refinement rather than relying solely on pure local search operators. Figure 17 further illustrates these trends through discovery curves, which track the best normalized data-driven error achieved as a function of iteration, averaged across datasets.

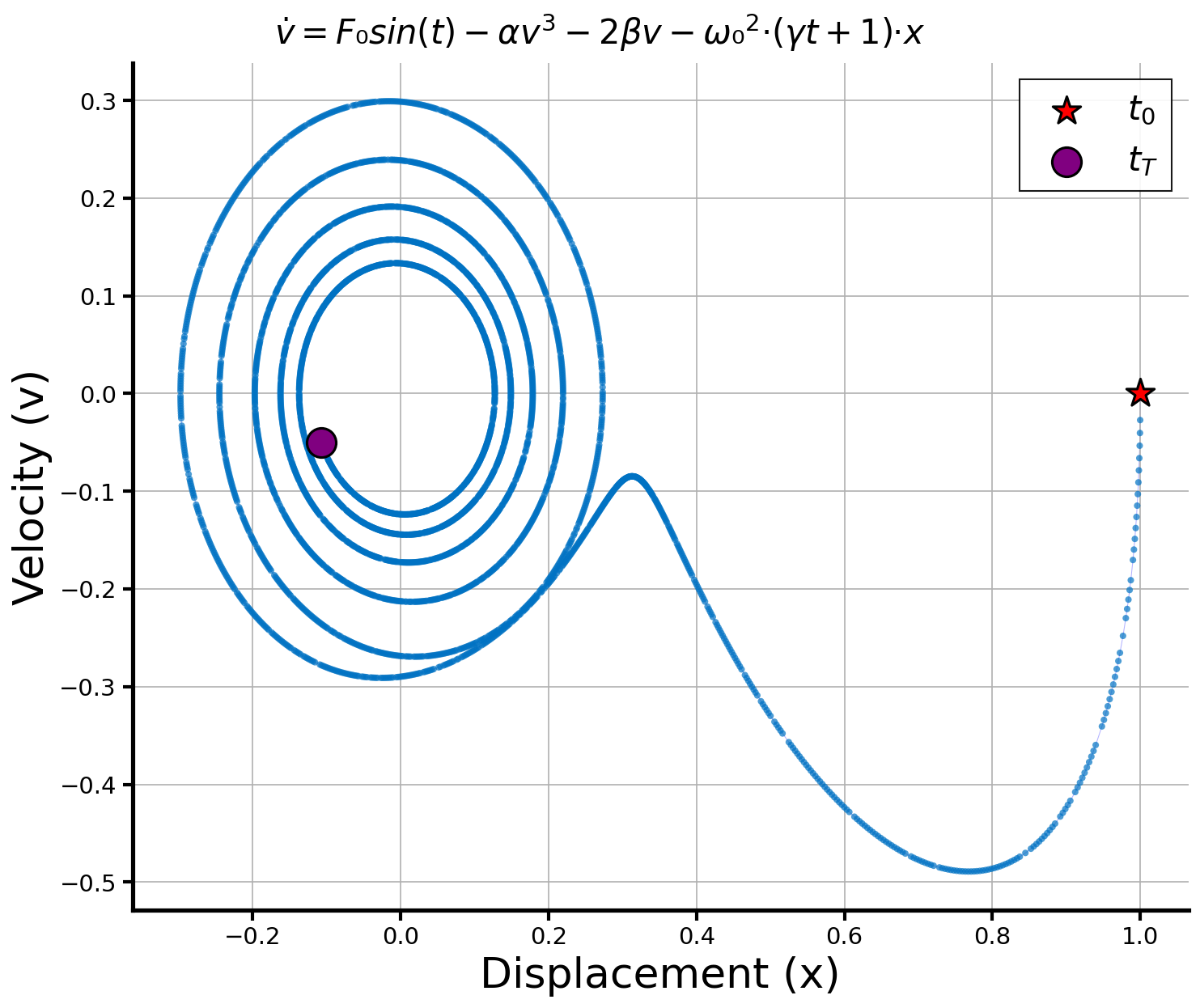

Beyond quantitative metrics, we examine the final symbolic programs discovered by each method. Qualitative inspection reveals that deepseek-R1 and gpt-5 show robustness in finding interpretable expressions faster in the process of discovery that closely match the true governing equations, often with minimal extraneous terms. claude-sonnet-4.5 also frequently identifies partially correct structures but mostly with redundant components that are more sensitive to problems and initial populations. Example of representative discovered programs for each method are provided below (example problem PO37), illustrating qualitative differences in symbolic structure, compactness, and physical interpretability. Table 5. Quantitative comparison results on symbolic regression. In-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) performance for symbolic regression, reporting accuracy to threshold 0.1 (Acc 0.1 , higher is better) and normalized mean squared error (NMSE, lower is better). Qualitative example for final discovered equation programs. We present a qualitative example for benchmark problem PO37. 65 Figure 18 shows the phase-space trajectory of the ground truth non-linear oscillator generated dynamics, alongside its ground-truth equation skeleton. # linear stiffness c = params [2] # linear damping beta = params [3] # cubic stiffness delta = params [4] # cubic damping F1 = params [5] # forcing amplitude 1 omega1 = params [6] # forcing frequency 1 phi1 = params [7] # forcing phase 1 F2 = params [8] # forcing amplitude 2 omega2 = params [9] # forcing frequency 2

Figure 3. Per-scenario accuracy for gpt-5 and o3. Scenarios in biology are colored in green, chemistry in orange, materials in purple, and physics in red. Parity is shown with a black dashed line.

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.