Grounded Multilingual Medical Reasoning for Question Answering with Large Language Models

📝 Original Info

- Title: Grounded Multilingual Medical Reasoning for Question Answering with Large Language Models

- ArXiv ID: 2512.05658

- Date: 2025-12-05

- Authors: Pietro Ferrazzi, Aitor Soroa, Rodrigo Agerri

📝 Abstract

Large Language Models (LLMs) with reasoning capabilities have recently demonstrated strong potential in medical Question Answering (QA). Existing approaches are largely English-focused and primarily rely on distillation from general-purpose LLMs, raising concerns about the reliability of their medical knowledge. In this work, we present a method to generate multilingual reasoning traces grounded in factual medical knowledge. We produce 500k traces in English, Italian, and Spanish, using a retrievalaugmented generation approach over medical information from Wikipedia. The traces are generated to solve medical questions drawn from MedQA and MedMCQA, which we extend to Italian and Spanish. We test our pipeline in both in-domain and outof-domain settings across Medical QA benchmarks, and demonstrate that our reasoning traces improve performance both when utilized via in-context learning (few-shot) and supervised fine-tuning, yielding state-of-the-art results among 8B-parameter LLMs. We believe that these resources can support the development of safer, more transparent clinical decision-support tools in multilingual settings. We release the full suite of resources: reasoning traces, translated QA datasets, Medical-Wikipedia, and fine-tuned models.📄 Full Content

• We present the first dataset of medical reasoning traces for Italian, Spanish and English, grounded on manually revised factual knowledge1 from medical text, with the potential to be extended to any language in Wikipedia.

• Comprehensive experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of applying our reasoning traces to multilingual, multiplechoice medical QA via in-context learning and supervised fine-tuning.

• We release a multilingual reasoning model that achieves state-of-the-art results in Italian, English, and Spanish2 .

In addition, we release two other datasets. First, a collection of all Wikipedia pages related to medicine in English, Italian and Spanish (Medical-Wikipedia 3 ). Second, a translated ver-Figure 1: Schema of our proposed pipeline to generate reasoning traces for multilingual multiple-choice medical question answering (QA). First, we create a Knowledge Base (KB) of medical information for each language. We extract relevant chunks from the KB for each pair of Question-Options (QO pair) in the source QA datasets, which we automatically port from English into Italian and Spanish. We prompt an LLM with the retrieved chunks and the QO pair for context rearrangement. Finally, we utilize the rearranged context, the question, the options and the correct answer to generate a reasoning trace that answers the question itself. Answers that lead to the wrong conclusion are dropped, while the remaining form our reasoning traces dataset. sion of two common, English-based medical question answering datasets (MedMCQA and MedQA) in Italian and Spanish4 that we use to guide and test the reasoning traces generation pipeline.

In this section, we review recent advances in reasoning capabilities for LLMs, starting with the development of foundational reasoning models like and their open-source counterparts, and then examining how these capabilities have been adapted for the medical domain, where reasoning-enhanced models combine domain-specific knowledge with multi-step inference processes. We survey approaches ranging from distillationbased methods to knowledge-grounded training, highlighting the main trends in medical reasoning research.

Reasoning with LLMs. In the context of Large Language Models, reasoning refers to the ability to answer questions by complex, multi-step processes with intermediate steps (Zhang et al., 2025a), producing a long chain of thought before providing the actual answer to the user. The first model explicitly designed for this purpose was OpenAI’s GPT-o1 (OpenAI et al., 2024c), which was trained with reinforcement learning to refine thinking process capabilities, and whose development process remains mostly undisclosed. Extensive work has been done on understanding and replicating GPT-o1 training phases and performances (Qin et al., 2024;Huang et al., 2024;Zeng et al., 2024). As a result of such efforts, DeepSeek’s R1 (Guo et al., 2025) was among the first open source models to address the same objective, similarly to QwQ (Team, 2025), marco-o1 (Zhao et al., 2024), and skywork-o1 (He et al., 2024). By achieving high performance in several benchmarks, these models have opened a line of research focused on investigating the impact of reasoning capabilities in several domains, including math (Ahn et al., 2024), physics (Xu et al., 2025), and biology (Liu et al., 2025b).

Reasoning for the medical domain. Previous work showed how medical-oriented tuning of foundational LLMs can lead to major improvements (Luo et al., 2022;Wu et al., 2024), even surpassing human experts on some benchmarks (Singhal et al., 2025). These results highlighted that domain-specific alignment can be beneficial for medical tasks. More recently, these findings have led to the integration of domain-shift and reasoning capabilities.

Chen et al. ( 2025) proposed Huatuo, among the first works to investigate the generation of reasoning traces for medical QA. Huatuo relies on automatic generation of verifiable problems from multiple-choice medical QA datasets. The generated traces, distilled from closed-source LLMs, are used to train models via supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and reinforcement learning (RL) in both Chinese and English. The authors found that models trained on those traces outperform their base counterparts on medical QA, even if the sole source of medical knowledge is a closed-source LLM. Wu et al. (2025) edge is derived from PrimeKG (Chandak et al., 2023), a knowledge graph of 17k diseases designed for medicine analysis in English. The model trained on those traces (MedReason) achieves slightly better performance than Huatuo, highlighting that medically grounded data can enhance reasoning capabilities for the English language. Huang et al. (2025) further advanced the field focusing on the effect of test-time-scaling (Muennighoff et al., 2025). The authors train a model on a few thousand examples generated via distillation, highlighting that the quality of the data is what matters. Other recent works follow the approach of generating traces and training on them via SFT or RL. Sun et al. (2025) build on distillation approaches with architectural adjustments for trace generation, while Yu et al. (2025) construct hundreds of thousands of synthetic medical instructions derived from Common Crawl. While innovative, this method relies heavily on LLMgenerated content with limited human validation and uncertain underlying medical quality. Liu et al. (2025a) explore eliciting reasoning capabilities from models without distillation and avoiding intensive use of resources, similarly to Thapa et al. (2025), who present a method to optimize the use of existing traces. Finally, Wang et al. (2025) provide a comprehensive review of recent advances.

We introduce a novel methodology for distilling reasoning traces that are explicitly grounded in reliable medical knowledge. The process involves four main stages: i) selecting the medical questions to handle, ii) constructing a curated Knowledge Base (KB) of reliable medical texts, iii) enriching each medical question with evidence retrieved from the KB using retrieval-augmented generation (Lewis et al., 2020), and iv) leveraging a large, high-capacity language model to generate a stepby-step reasoning trace that leads to the correct answer among the given options.

The first step of the pipeline involves identifying the medical questions on which to base the answer reasoning traces. We select those questions from existing datasets in the field.

Datasets. The MultiMedQA benchmark introduced in the Med-PaLM paper (Singhal et al., 2023), including MedMCQA (Pal et al., 2022), MedQA (Jin et al., 2021), PubMedQA (Jin et al., 2019), and MMLU clinical (Hendrycks et al., 2021) is the main attempt to standardize multiple-choice medical QA datasets. Following prior work (Wu et al., 2025;Chen et al., 2025), we focus our approach on MedMCQA and MedQA, which are constructed using medical exams from India and the USA, respectively. Additionally, we include MedExpQA (Alonso et al., 2024), as it is currently the only manually validated multiplechoice medical QA dataset available for Italian, Spanish, and English. A summary of the selected datasets is provided in Table 2. Dataset translation. MedMCQA and MedQA are originally English datasets. Given the multilingual objective of our work, we translated each Question-Options pair into Italian and Spanish using Qwen-2.5-72B (Qwen et al., 2025), prompted with a 5-shot example setup. To assess the quality of these translations and ensure that evaluation on the translated datasets is meaningful, we employ back-translation: the non-English items are translated back into English and compared against the original. Prior work has demonstrated that back-translation scores can serve as a useful proxy for translation quality and correlate with human judgments (Rapp, 2009;Zhuo et al., 2023). Furthermore, the widespread use of back-translation as a data augmentation and validation technique (Sennrich et al., 2016;Bourgeade et al., 2024;Sugiyama and Yoshinaga, 2019) supports our use of it for assessing translation quality in Italian and Spanish. We compared the original and back-translated question-answer pairs by means of COMET, CHRF (Popović, 2015), CHRF++ (Popović, 2017), and BERTScore (Zhang et al., 2020) metrics.

As shown in Table 1, the back-translation quality is consistently high across both Italian and Spanish, with strong semantic similarity indicated by BERTscore and COMET scores (0.89/0.97). The chrF and chrF++ values likewise show robust similarity, confirming that the translated datasets remain faithful to the original English content. Fine-grained results are reported in Appendix A.2. Nevertheless, since automatic metrics may not fully reflect translation inaccuracies, we use the native multilingual MedExpQA dataset solely for testing, ensuring that our out-of-domain evaluation is performed with human-validated data.

Our goal is to generate reasoning traces grounded in factual medical knowledge across three languages: English, Italian, and Spanish. To achieve this, we require reliable source material that comprehensively covers the range of medical specialties. Moreover, to ensure a fair comparison of results across languages, the underlying knowledge must be aligned across all three of them. Without such alignment, it would be hard to disentangle whether downstream performance differences arise from linguistic characteristics or from discrepancies in the knowledge sources. Accordingly, the requirements for the KB are: i) reliability and diversity of the medical texts Smith (2020), and ii) parallel information availability across the three languages. To satisfy these conditions, and taking advantage of its open collaborative editing model and of WikiProject Medicine, we considered Wikipedia as our primary source of knowledge.

Medical-Wikipedia creation. The construction of our medical knowledge base builds upon WikiProject Medicine, a Wikipedia project that aims to collect all pages related to the medical domain. First, we collected links to all the English relevant pages5 . For each page, we extracted the main text, infobox content, and interlanguage links. Using the links, we retrieved the corresponding pages in Italian and Spanish. This procedure resulted in a multilingual Medical-Wikipedia dataset in English, Italian, and Spanish, suitable for a variety of use cases beyond medical question answering, which we release publicly for the research community.

From Medical-Wikipedia to Knowledge Base. We employed the constructed dataset to build language-specific knowledge bases that could be queried to retrieve context to support answering medical questions. To ensure a meaningful cross-lingual comparison of medical reasoning, we enforced consistency across the three knowledge bases by retaining only pages available in all three languages. While this filtering step significantly reduced the dataset size, particularly for English, it resulted in a nearly parallel multilingual corpus. Since we rely on a project originating from the English Wikipedia, pages without an English counterpart are not included; however, given the extensive coverage in English, this omission is unlikely to be significant.

Although we cannot guarantee perfect alignment in page content and information density across languages, the resulting knowledge bases remain sufficiently comparable, ensuring that the same medical topics are present in all three languages.

We segmented the collected pages into chunks to construct the target knowledge bases. Each section of a page is treated as a chunk. Sections exceeding 5,000 words were discarded, while sections containing fewer than 250 words were merged with the preceding ones. We filtered out irrelevant sections, such as “Bibliography” and “External links” (a comprehensive list is provided in the Appendix). An overview of the outcome of each step is presented in Table 3.

Once the knowledge base is constructed, we enriched each medical question from MedQA and MedMCQA with the most Table 3: Number of pages extracted from the Wikipedia Project for the three languages (Source). De-duplication combines medical topics repeated in multiple links. Finally, the KB is restricted to pages available in all three languages (All 3 lang), the number of which can slightly vary as certain concepts are split across multiple pages in one language but merged into a single page in another.

relevant contextual information. Following the paradigm of Retrieval-Augmented Generation, we pre-pended the retrieved passages to the model input prior to prompting. More specifically, we pre-compute the embedding of each chunk in the KB, calculating its cosine similarity with each Question-Options pair.

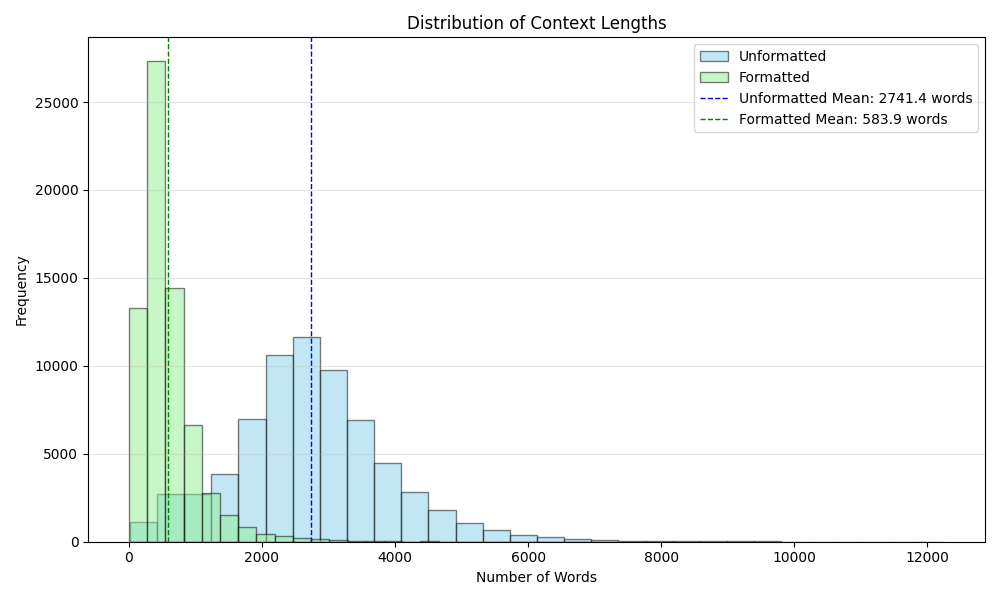

We select the top five most similar chunks as context. Embeddings are computed using the top-performing model from the MTEB leaderboard (Enevoldsen et al., 2025) retrieval task at the time of writing (Qwen3-Embedding-8B by Zhang et al. (2025b)). To address the issue of potential redundancy and inclusion of irrelevant information in the context highlighted by (Wang et al., 2024), we prompt an LLM (Qwen3-32B, Yang et al. ( 2025)) to rewrite the retrieved chunks. This step ensures consistency within the retrieved chunks, enhancing conciseness and avoiding duplication. The prompt template and more details on the results of this step are presented in Appendix A.1.

We prompt an open-source reasoning model, Qwen3-32B, to generate reasoning traces, providing an input composed by four parts, each placed to enhance the quality of the generated traces: i) the formatted contextual information retrieved from the KB, to provide factual knowledge on the medical topic; ii) the medical question that defines the problem iii) the answer options that constrain the space of reasoning paths; iv) the correct answer to guide the model toward selecting the most appropriate path. We enforce the use of the correct answer, motivated by our goal of generating the most accurate and informative traces possible. To prevent the model from collapsing into simply stating the correct answer, we design the prompt to encourage exploration of a space of potential answers before reaching the conclusion. The system prompt, with a structure based on the findings of Wu et al. (2025), is described in Appendix A.1.

We verify the traces’ conclusions by extracting the answer identifier via regular expression matching and discarding the incorrect ones, as suggested by the “philosophy of verifiability” in Chen et al. (2025). Notably, this resulted in discarding less than 5% of the traces, meaning that our pipeline produces answers that usually lead to correct answers.

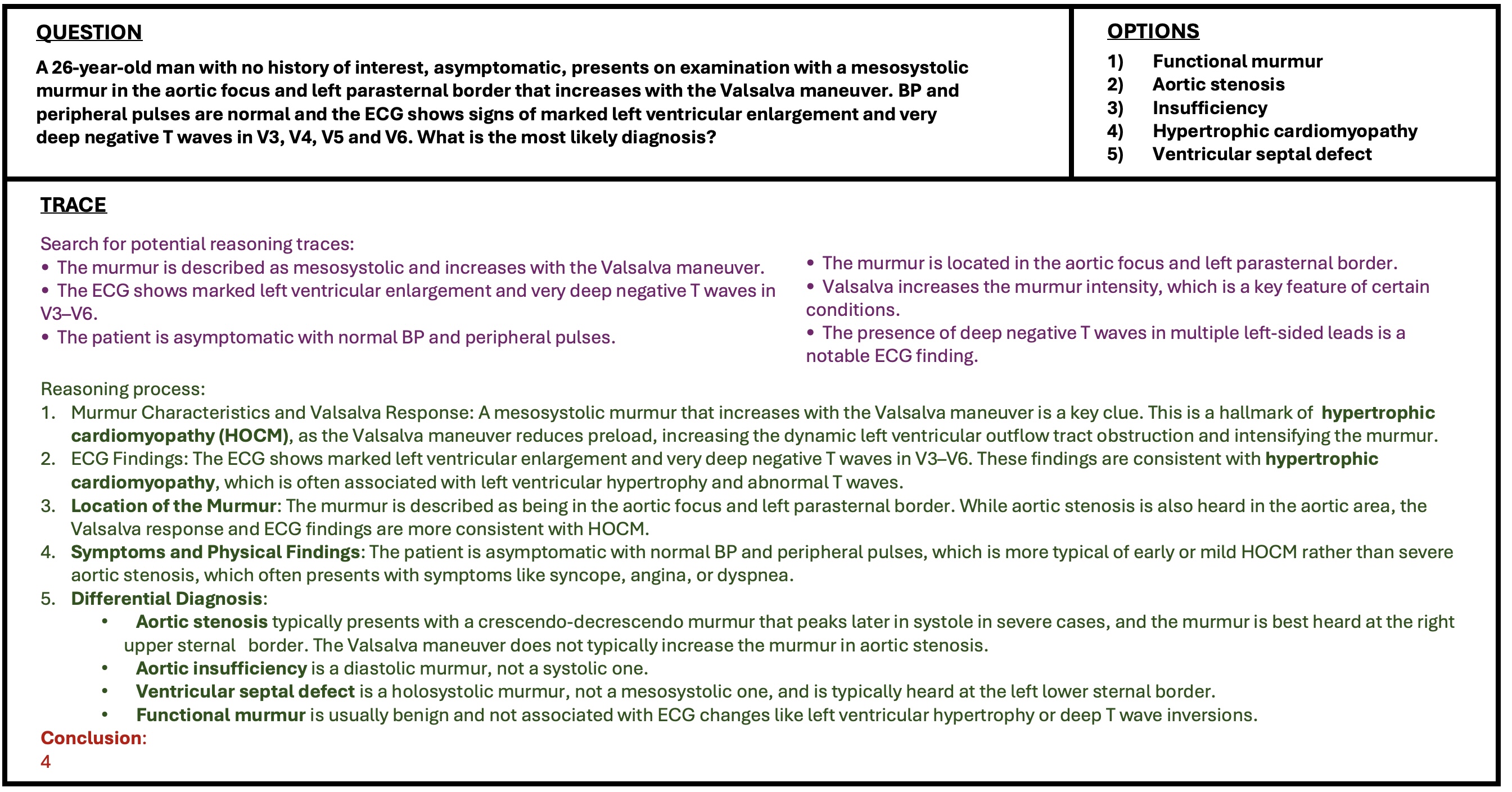

We obtain a dataset of more than 500k reasoning traces, each answering a different medical question given the options in one of the three languages. The Italian split consists of 166.257 traces from MedMCQA, 9.468 from MedQA; the Spanish split of 168.771 from MedMCQA, 9.584 from MedQA; the English split of 169.098 from MedMCQA, 9.520 from MedQA. An example of a generated trace can be seen in Figure 2.

We evaluate the usefulness of the reasoning traces we generate. Specifically, we aim to determine how well reasoning traces assist in performing the Medical QA task when applied in in-context learning (ICL) or supervised fine-tuning (SFT) settings. Our primary measure of interest is downstream accuracy, which directly reflects whether the traces fulfill their intended purpose.

For both ICL and SFT experiments, examples are drawn from the training splits of MedQA and MedMCQA. Evaluation is conducted on the combined train, validation, and test splits of MedExpQA, guaranteeing out-of-distribution testing on original multilingual data, as well as on the test set of MedQA and the validation set of MedMCQA6 (previously described in Table 2).

In addition to the main evaluation dimension, we also examine two further aspects: (i) the comparison of our approach against prior methods, and (ii) the impact of multilingualism.

Baselines. To determine if our traces are helpful, we need to define a baseline to compare against. We adopt a few-shot evaluation setting, where each prompt includes two example questions with their options and correct answers, followed by the test question. To ensure a fair and competitive baseline, the examples are selected through similarity search in an embedding space: for each test question, we retrieve the most similar training questions (along with their answers) to use as few-shot examples.

We aim to determine the impact of utilizing our traces via in-context learning. To do so, we test a variety of models by providing medical questions enriched with the 2 most similar examples of questions, options, reasoning trace and correct answer. The only difference with the baselines lies in the use of reasoning traces: baseline prompts include only questions, options, and answers, while our systems also include the corresponding reasoning traces. The retrieval strategy remains identical across both settings, ensuring that any observed improvements can be attributed to the inclusion of our traces.

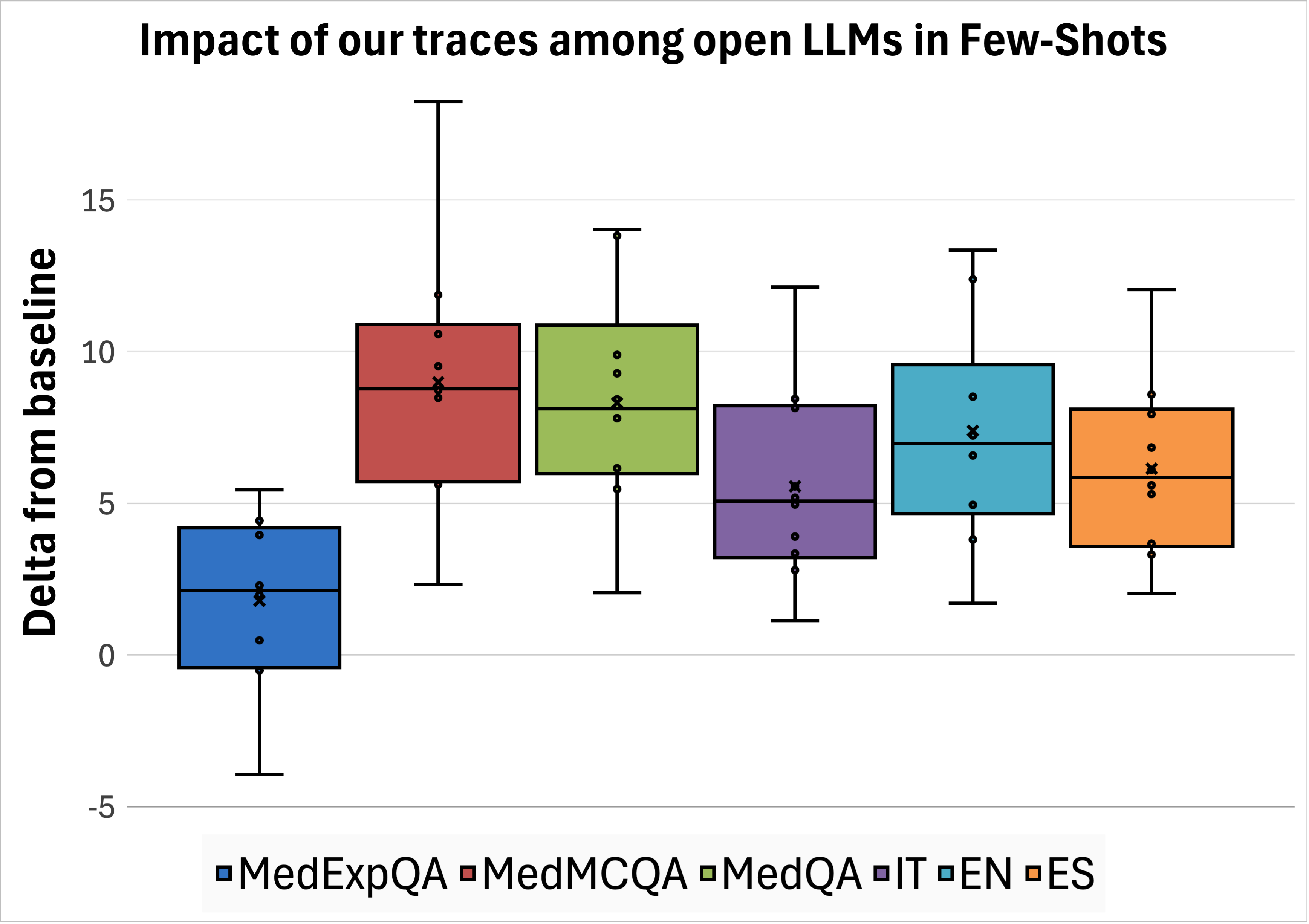

To ensure our evaluation represents a diverse set of models, we tested several families using vLLM7 : Qwen 3 (Yang et al., 2025) (1.7B, 8B, 32B), Llama 3 (Grattafiori et al., 2024) (1B, 8B, 70B), Gemma 3 (Team et al., 2025) (1B, 4B, 27B), MedGemma 3 (Sellergren et al., 2025) (4B, 27B) in their instructed versions, and GPT-4o (OpenAI et al., 2024a). Results. We observed that our traces enable all open-source models to generate more accurate answers compared to the baseline, as reported in Table 4. The average effect of our traces among datasets and languages is shown in Figure 3. For medical questions in MedMCQA and MedQA, we observe an average increase in accuracy of +7 to +10 points across all languages. The out-of-distribution dataset (MedExpQA) is the one that benefits the least, with the case of Gemma-3-27B and Qwen-3-32B not getting any benefit at all. Nevertheless, the overall impact among models on this dataset is positive, with an average increase in accuracy of +1.8 points. To verify the hypothesis of such a positive impact being significant, we employ the t-test on the deltas between model performances with and without our traces, resulting in a p-value of 0.02.

In the case of GPT-4o, the overall performance increase due to exposing the model to our transcripts via in-context learning is +0.5 across datasets and languages. We test the significance of this impact by means of the t-test, resulting in a p-value of 0.2. This lack of significance is mainly due to the negative impact on MedMCQA and the null impact on Italian.

To measure how our reasoning traces influence model learning, we fine-tuned models in a supervised setting. Due to com-putational constraints, we restricted our experiments to Llama-3-8B and Qwen3-8B. We trained each model on examples formatted as {question}

We refined the training data by distinguishing between “reasoningintensive” and “knowledge-intensive” questions, following the classification method proposed by Thapa et al. (2025). Their work demonstrated that prioritizing reasoning-intensive examples during training yields better downstream QA performance than using a random sample. We also experimented with using the full dataset, but observed worse results. Consistent with the findings of Liu et al. (2025a), which suggest prioritizing MedQA sampling ratio as training source over MedM-CQA, our final fine-tuning dataset comprises 5,837 traces from MedMCQA and 5,594 from MedQA per language, for a total of 34,293 examples across English, Italian, and Spanish.

We fine-tuned the models by tuning all parameters for 3 epochs on two H200 GPUs, with a per-device batch size of 32, using AdamW optimiser with a learning rate of 5e -6, a cosine scheduler, and a warm-up ratio of 0.1. Training on these settings took 1.5 hours per model.

. We observed that training on our traces benefits both Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct and Qwen3-8B, yielding an average accuracy improvement of 3.9 points (Table 5). Interest- ingly, the gains are smaller than those seen in the few-shot setting. We attribute this to the nature of the traces: they are highly informative, and when provided directly as few-shot examples, they act as strong, targeted guidance for the test question to instructed models that are highly capable of handling long prompts. In contrast, fine-tuning aims to generalize such knowledge, which turns out to be less effective than delivering the exact relevant information at inference time. We further analyse this behaviour in the next section, showing that combining fine-tuned models with our traces in few-shot prompts leads to the best overall performance.

As described in Section 2, the main previous efforts on generating reasoning traces for medical question answering are Huatuo (Chen et al., 2025), MedReason (Wu et al., 2025), and m1-m23k (Huang et al., 2025). They generated and released traces of 19.704, 32.682, and 23.493 question-trace pairs, respectively, on which they trained models using supervised finetuning and reinforcement learning techniques. We aim to compare our traces against those from previous work. We do so in three steps. First, we evaluate their effect in (i) few-shot prompting and (ii) supervised fine-tuning. Finally, (iii) we evaluate each method under its strongest reported configuration. This final step goes beyond a trace-level comparison, highlighting overall effectiveness and demonstrating that our best model consistently outperforms any other alternatives.

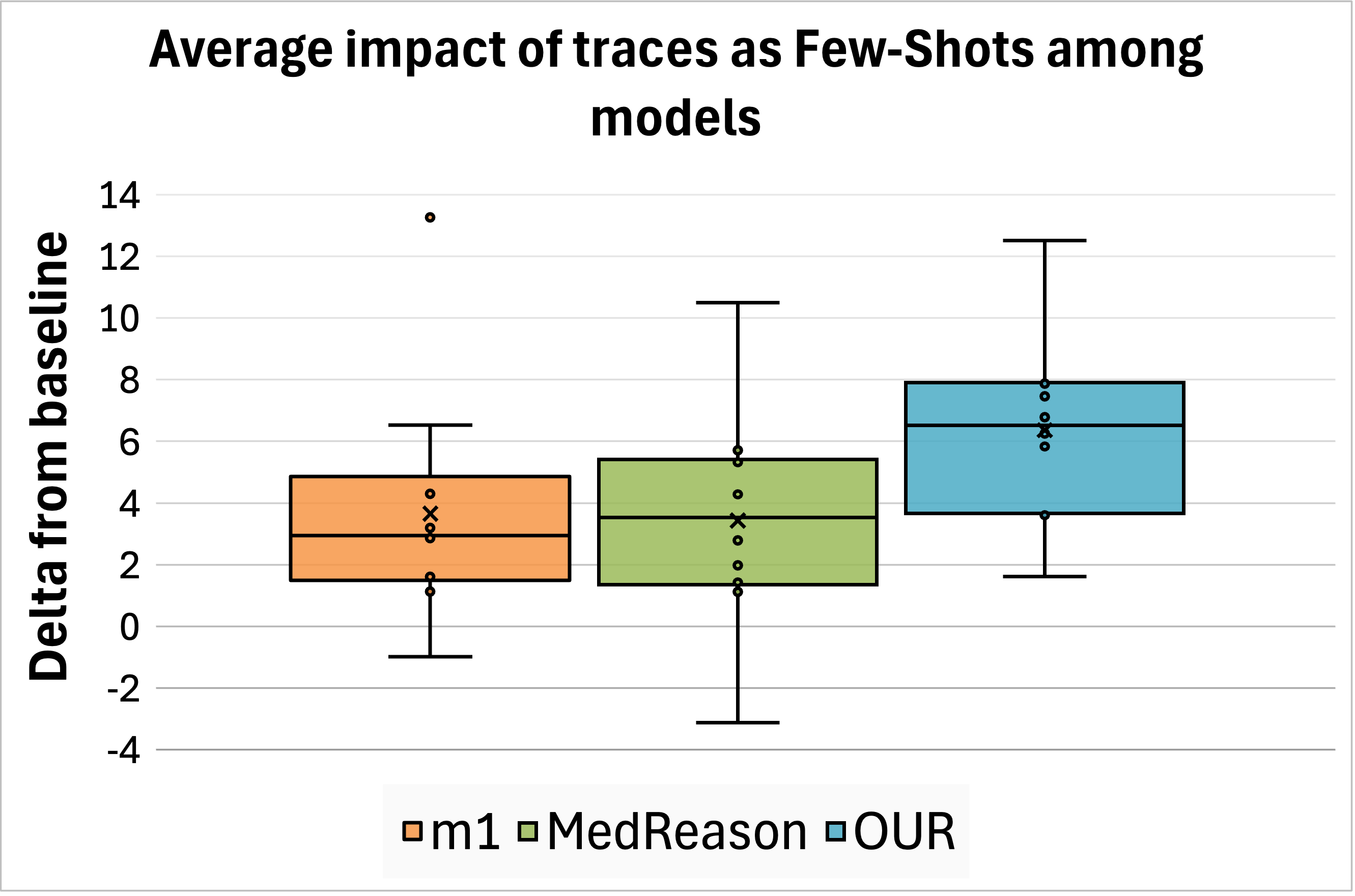

Few-Shot. We test the effect of MedReason and m1 traces at inference time on the same eleven models described in Section 4.1 and measuring accuracy improvements, directly comparing against our traces. Huatuo traces could not be evaluated in this setting because they are framed as open-ended questions without multiple-choice options or unique correct answers. We observed that our traces provide the greatest average improvement among datasets and languages. We report the overall impact in Figure 4 (top left); detailed results are presented in Appendix C.

Fine-Tuning. We fine-tuned Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct and Qwen3-8B using the reasoning traces and official codebases provided by MedReason, m1, and Huatuo. We retained the hyperparameters specified in each work, training on two H200 GPUs for a total of approximately 18 hours. The resulting models are evaluated in our multilingual setting. Since the evaluated trace types are English-only, models trained on them tend to produce reasoning in English at inference time. To mitigate this, we explicitly prompted them to generate responses in the target language of each question, as shown in Appendix A.1. Downstream accuracy demonstrates that our traces achieve superior performance across all datasets and languages compared to other models (Figure 4, top right; detailed results in Appendix C), with the sole exception of Huatuo traces applied to Qwen on MedMCQA and MedQA.

State-of-the-art performance. Finally, we compare the overall performance of the strongest models from prior work to our best fine-tuned model based on Qwen3-8B. The results aggregated by language and dataset are presented in Figure 4 (bottom left, “state-of-the-art performances”), while detailed results can be found in the Appendix, Table C.10. We find that our model in its basic configuration outperforms the best prior model, Huatuo, by an average of 3 points. In addition, improving our fine-tuned model with two of our traces as examples at inference time obtains the highest overall accuracy, surpassing Huatuo by 7 points. When considering only the English portion of the datasets, our enhanced model still outperforms Huatuo by a margin of +1.7 points.

Previous sections demonstrated that integrating multilingual data during fine-tuning leads to improved accuracy on downstream tasks. To further examine this phenomenon, this study analyzes cross-lingual transfer effects throughout model training.

More specifically, we trained Qwen3-8B using reasoning traces from individual languages as well as from all three languages put together, following the training protocol outlined in Section 4.2. The results indicate that multilingual training consistently matches or surpasses the performance of singlelanguage training. In contrast, models trained exclusively on one language exhibit worse accuracy when evaluated on other languages (see Figure 4, bottom-right). These findings underscore the positive impact of cross-lingual learning and emphasize the value of incorporating diverse languages into the training data.

To gain deeper insight into model errors, we conducted an error analysis on the highest-performing model in our study, Qwen3-8B. Quantitative analysis. We first analyzed questions that the model answered incorrectly in the 2-shot baseline but correctly after fine-tuning with our traces. On average, 45% of baseline errors were corrected. Correction rates showed minimal crosslinguistic variation (English: 46%, Italian: 44%, Spanish: 46%), indicating no language-specific advantage.

Comparing in-domain (46% correction rate) and out-of-domain (38%) datasets revealed a gap. This gap, yet modest, resulted in a statistically significant difference when tested via a twoproportion z-test (p-val of 0.05). While this difference reflects the expected benefit of domain-aligned training data, the relatively small magnitude suggests reasonable generalization of our traces across domains.

This quantitative analysis revealed minimal variation across languages and modest differences across datasets, providing limited insight into model behavior. To gain a deeper understanding, we conducted manual error analysis focusing on cases where the fine-tuned model continued to fail.

Qualitative analysis. Although aggregate accuracy metrics summarize model performance, they do not explain the underlying sources of error. To address this limitation, manual error analysis is used to identify systematic failure modes, including fac-tual inaccuracies, deficits in medical knowledge, and inconsistencies in reasoning.

We performed a manual analysis of a subset of 20 questions that our best-performing model (Qwen3-8B) trained on our traces answered incorrectly. We asked two medical doctors to determine which dimensions would be useful to analyse to help us understand the primary error sources. Based on this sample, they identified that issues were raised because of: (i) incomplete or incorrect use of information provided in the question, (ii) insufficient factual medical knowledge, and (iii) limitations in applying logical reasoning based on that knowledge. Based on these findings, we constructed three questions to guide further analysis:

• Does the answer take into account the useful elements present in the question?

• Does the answer report medical knowledge mistakes?

• Does the answer contain logical mistakes?

To quantify the contribution of each error source, we randomly sampled an additional 75 question-option-reasoning triplets and reviewed them with the support of eleven medical doctors selected to cover different linguistic areas8 . The physicians were asked to analyze triplets in their native language (English, Italian, or Spanish). For each triplet, we ask one doctor to analyse it in the light of the three defined questions. We carefully read the answers and found that the main performance bottleneck is the limited medical knowledge of the model, with the most apparent inconsistencies of reasoning arising from difficulties in integrating relevant clinical information rather than from reasoning alone. Furthermore, overlooked information from the question frequently related to the interactions between patient characteristics and underlying medical conditions.

Overall, the model’s errors can be primarily attributed to the lack of medical knowledge. This includes failure to integrate the full patient history, instead overemphasizing isolated details (Appendix D,Figure D.8); difficulty in correctly applying stan-dard diagnostic protocols (Figure 5); and restricted capacity to exercise nuanced clinical judgment (Appendix D Figure D.7). Additional illustrative cases from the manual error analysis for each language are provided in Appendix D.

This paper introduces a new methodology for generating multilingual medical reasoning traces grounded in manually revised factual medical knowledge extracted from the WikiProject Medicine, addressing critical gaps in current LLM approaches for medical question answering. Our main contributions are threefold: First, we present the first dataset of medical reasoning traces for Italian, Spanish, and English, generated from answering medical questions from MedQA and MedMCQA. Second, we conduct comprehensive experiments demonstrating that training on these traces improves both in-context learning and supervised fine-tuning, consistently achieving state-of-theart performance in multilingual medical QA. Third, we release a multilingual reasoning model alongside two new resources: a multilingual collection of reasoning traces and translated versions of established medical QA benchmarks.

Our evaluation demonstrates that the traces we generate are consistently useful across model families applied via in-context learning as well as supervised fine-tuning, helping models to learn to answer medical questions more accurately.

Comparative evaluation against prior work confirms that our approach obtains better accuracy in multilingual, multiple-choice medical question answering, with marginal improvements observed even on English-specific benchmarks. Crucially, we establish that multilingual training confers significant performance advantages: models trained on reasoning traces from a single language consistently underperform relative to those trained jointly on all three languages.

Our work has some limitations. First, we focus on only three languages, namely, English, Italian, and Spanish, whereas multilingual medical reasoning could be extended to a much broader set of languages. Second, we rely on Wikipedia as our primary source of medical knowledge due to its cross-lingual parallelism, though more authoritative medical sources could further strengthen grounding. Furthermore, the English knowledge base is significantly larger than the others due to the nature of Wikipedia pages. Third, our fine-tuning experiments are restricted to 8B-parameter models because of computational constraints; scaling to larger models remains unexplored. Finally, we limit our study to multiple-choice medical question answering, leaving open-ended clinical reasoning tasks for future work. input: “Growth hormone has its effect on growth through?” output it: “L’ormone della crescita esercita il suo effetto sulla crescita attraverso?” output es: “La hormona del crecimiento tiene su efecto sobre el crecimiento a través de?” input: “What is the main function of the liver?” output it: “Qual è la funzione principale del fegato?” output es: “Cuál es la función principal del hígado?” input: “Thyroxine” output it: “Tiroxina” output es: “Tiroxina” input: “IG1-1” output it: “IG1-1” output es: “IG1-1” input: “Duodenal Switch” output it: “Duodenal Switch” output es: “Switch Duodenal” Prompt template for context rewriting.

You are a helpful assistant that rewrites medical text to be more clear and concise. Your task is to rearrange the text to improve its clarity and coherence. Return the rewritten text without saying anything else."

The formatting of the context produced the results reported in Figure A.6.

Prompt template for reasoning trace generation. System prompt:

You are a medical expert that reason about medical questions given some provided context.

-

Analyze and evaluate the

carefully, expanding on the most relevant ones to construct a logical, well-supported explanation. 3. Do not mention the existence of nor provided in your response. 4. Do not assume the given is correct. Instead, determine the answer solely based on your reasoning. 5. If your final conclusion contradicts the given , acknowledge potential discrepancies (e.g., “Wait, there might be something wrong) and refine your response accordingly. -

The answer should just report the answer’s number/identifier ### Output: Search for potential reasoning traces: (Find potentially useful reasoning traces. It must be a concise list of traces) Reasoning process: (Step-by-step reasoning process) Conclusion:

(The final answer resulting from your reasoning. Must be the identifier of the correct option, e.g. “1”, “2”, “3”, “4” o “5”.)

Prompt for 2-shot inference (Baseline). System prompt:

You are an {language} Al assistant that helps people find information.

You are an expert in the medical domain. Given a medical

Expert Comment. The model makes a critical medical knowledge error regarding Reiter’s syndrome. It incorrectly states that Reiter’s does not typically present with psoriasiform lesions or mucocutaneous erosions. In fact, these features are classic characteristics of the syndrome (known as keratoderma blennorrhagicum and circinate balanitis). This fundamental mis-take led the model to incorrectly rule out the correct diagnosis.

QUESTION: Un uomo di 30 anni è caduto in piedi da un’altezza di 2 metri. All’arrivo al Pronto Soccorso era supino e aveva cateterizzato la vescica con urine chiare. Presenta un gonfiore al tallone sinistro, un leggero formicolio alla parte anteriore della coscia destra e allo scroto e disestesia a entrambi i piedi. Il paziente saluta il barelliere con una stretta di mano e una contemporanea pacca sulla spalla. La rotazione del MMII sulla barella afferrata dalle caviglie è indolore e la compressione del bacino è asintomatica. Il prossimo: OPZIONI: ‘1’: ‘Il paziente viene fatto sedere sulla barella in modo da poter esplorare il rachide cervicale.’, ‘2’: ‘Fare riferimento alla Rx per lo studio degli arti inferiori.’, ‘3’: “Palpare l’addome e ruotarlo in blocco per palpare la colonna vertebrale toracolombare.”, ‘4’: ‘Il paziente verrà sottoposto a un collare cervicale e inviato in radiologia per la diagnostica per immagini del rachide cervicale e degli arti inferiori.’, ‘5’: “Verrà richiesta un’ecografia addominale.”

RISPOSTA CORRETTA: 3 RISPOSTA DEL MODELLO: Ricerca di potenziali tracce di ragionamento: -Il paziente ha subito una caduta da 2 metri in piedi, con impatto potenzialmente traumatico. -All’arrivo al Pronto Soccorso presenta sintomi neurologici: formicolio alla coscia destra, scroto e disestesia ai piedi. -La stretta di mano e la pacca sulla spalla suggeriscono una funzionalità motoria conservata, ma non esclude una lesione spinale. -Il gonfiore al tallone sinistro potrebbe indicare una frattura o una contusione, ma non spiega i sintomi neurologici. -La manovra di rotazione del MMII e la compressione del bacino sono asintomatiche, suggerendo una possibile assenza di lesione spinale a livello lombare o sacrale. -I sintomi neurologici (formicolio, disestesia) suggeriscono una possibile lesione spinale a livello toracico o cervicale. -La manovra di rotazione del MMII e la compressione del bacino non sono sufficienti per escludere una lesione spinale. -È necessario un esame neurologico più approfondito, iniziando con la valutazione del rachide cervicale.

Processo di ragionamento: 1. Il paziente ha subito una caduta da 2 metri in piedi, un evento che può causare lesioni spinali, specialmente se l’atterraggio non è stato attutito. 2. I sintomi neurologici (formicolio, disestesia) indicano una possibile lesione spinale, in particolare a livello toracico o cervicale. 3. La stretta di mano e la pacca sulla spalla suggeriscono una funzionalità motoria conservata, ma non escludono una lesione spinale. 4. La manovra di rotazione del MMII e la compressione del bacino sono asintomatiche, suggerendo una possibile assenza di lesione spinale a livello lombare o sacrale. 5. Per escludere una lesione spinale a livello cervicale, è necessario effettuare una valutazione neurologica iniziale, iniziando con la valutazione del rachide cervicale. 6. Il paziente deve essere posizionato in modo da permettere una valutazione neurologica completa, iniziando con il rachide cervicale. 7. L’opzione 1 propone di far sedere il paziente per esplorare il rachide cervicale, il che è coerente con la valutazione iniziale richiesta. 8. Le altre opzioni non sono appropriate per la valutazione iniziale di un paziente con sospetta lesione spinale.

Conclusione: 1

Expert Comment. Presenta alcuni errori di conoscenza medica: Concentra la valutazione sul rachiede cervicale senza senza valutare l’esame neurologico complessivo Contiene alcuni errori logici: Non considera la possibilità che la lesione spianale si aggravi facendo mettere seduto io paziente prima di aver controllato tutti i distretti Appendix D.3. Spanish PREGUNTA: En un paciente con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC) leve en fase estable se evidencia poliglobulia e insuficiencia respiratoria. En la radiografía de tórax no se aprecian alteraciones reseñables. ¿Cuál de los siguientes procedimientos consideraría realizar en primer lugar para descartar la coexistencia de otras enfermedades que puedan justificar los hallazgos descritos?: OPCIONES: ‘1’: ‘Poligrafía respiratoria.’, ‘2’: ‘Ecocardiograma.’, ‘3’: ‘Tomografía computarizada torácica.’, ‘4’: ‘Gammagrafía pulmonar.’, ‘5’: ‘Punción de médula ósea.’ RESPUESTA CORRECTA: 1 RESPUESTA DEL MODELO: Búsqueda de posibles muestras de razonamiento: -La poliglobulia en un paciente con EPOC puede deberse a hipoxia crónica, pero también puede ser secundaria a otras condiciones como mieloproliferativas o tumores. -La insuficiencia respiratoria en un paciente con EPOC leve sugiere que podría haber una causa subyacente no evaluada. -La radiografía de tórax no muestra alteraciones, lo cual no excluye patología pulmonar o sistémica. -La gammagrafía pulmonar puede ayudar a evaluar la perfusión y la ventilación pulmonar, lo cual es útil para descartar neumonía, embolia pulmonar o neoplasias. -La tomografía computarizada torácica es más sensible que la radiografía, pero no es el primer paso en un paciente con EPOC estable. -La ecocardiografía puede ser útil para evaluar hipertensión pulmonar, pero no es el primer procedimiento para descartar otras causas de poliglobulia.

-La poligrafía respiratoria es útil para evaluar la función pulmonar, pero no aporta información sobre causas sistémicas de poliglobulia. -La punción de médula ósea es invasiva y no es el primer paso para descartar causas no hematológicas de poliglobulia. Proceso de razonamiento: 1. El paciente tiene EPOC leve en fase estable, pero presenta poliglobulia e insuficiencia respiratoria, lo cual sugiere una causa subyacente no evaluada. 2. La poliglobulia puede deberse a hipoxia crónica, pero también puede ser secundaria a otras condiciones como mieloproliferativas, tumores o infecciones. 3. La gammagrafía pulmonar permite evaluar la perfusión y la ventilación pulmonar, lo cual es útil para descartar neoplasias, embolia pulmonar o neumonía. 4. La tomografía computarizada torácica es más sensible, pero no es el primer procedimiento a realizar en un paciente con EPOC estable. 5. La ecocardiografía puede ser útil para evaluar hipertensión pulmonar, pero no es el primer paso para descartar otras causas de poliglobulia. 6. La poligrafía respiratoria es útil para evaluar la función pulmonar, pero no aporta información sobre causas sistémicas de poliglobulia. 7. La punción de médula ósea es invasiva y no es el primer paso para descartar causas no hematológicas de poliglobulia. 8. Por lo tanto, la gammagrafía pulmonar es el procedimiento más adecuado para descartar otras enfermedades que puedan justificar los hallazgos descritos.

Conclusión: 4

Expert Comment. La respuesta no tiene en cuenta todos los elementos útiles: Información clínica del paciente, usualmente se repetiría el hemograma para ver si sigue teniendo policitemia.

Table C.10: Performance (accuracy) of best performing models on MedExpQA, MedMCQA, and MedQA in Italian, English and Spanish. Our proposed model achieves the best performances.

https://huggingface.co/datasets/NLP-FBK/ multilingual-medical-reasoning-traces

https://huggingface.co/NLP-FBK/Qwen3-8B-medical-reasoning

https://huggingface.co/collections/NLP-FBK/ medical-wikipedia

https://huggingface.co/collections/NLP-FBK/ medical-qa-translated-en-es-it

Pages are listed at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia : WikiProject_Medicine/Lists_of_pages/Articles

MedMCQA test labels are not released. We follow prior works and keep the validation set for testing purposes only.

https://github.com/vllm-project/vllm

Six from Italy for Italian; two from Peru and one from Spain for Spanish; one from Canada and one from Vietnam for English.

📸 Image Gallery