Figure 1: A comparison of isolated vs. context-aware summarization. (Red) An isolated summary describes a file's low-level implementation details. (Green) Our context-aware approach, primed with a repository-level "seed context," produces a summary that explains the file's architectural role and purpose, which is more effective for bug localization.

Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly applied to complex software engineering tasks like bug localization. However, current methods, which primarily rely on Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) over raw source code, face significant challenges in large-scale, industrial settings. These systems often struggle with three key limitations. First, they must bridge the semantic gap, where the natural language of a user's bug report often lacks semantic overlap with the technical terms in the code. Second, they are constrained by the LLM's finite context window, which prevents them from comprehending an entire codebase holistically. Third, they are often designed with an implicit single-repository assumption. This makes them ineffective for large-scale software projects composed of many interacting microservices, as they lack a mechanism to first route a bug report to the correct repository (codebase) before localization can begin.

In this work, we explore an alternative paradigm. As illustrated in Figure 2, most current methods move down the abstraction ladder, transforming source code (PL) into lowlevel vector embeddings for similarity search. We hypothesize that for complex bug localization, it is more effective to move up the ladder. By representing code at a higher level of abstraction-natural language (NL) summaries-we reframe the problem. This shift from a cross-modal retrieval task to a unified NL-to-NL reasoning task is designed to directly leverage the powerful semantic understanding of modern LLMs.

We present a methodology to realize this approach. To manage the scale of enterprise systems, we first transform the source code across all repositories within a project into a compact, hierarchical NL knowledge base. This is achieved through context-aware summarization, which creates semantically rich descriptions that capture the architectural purpose of each component. This compact representation helps mitigate the LLM’s context window limitations. The knowledge base is then navigated using a scalable, two-phase hierarchical search that first identifies the most probable repository before performing a targeted, top-down search for the faulty file.

Our primary contributions are:

• A methodology for transforming a multi-repository software project into a hierarchical NL knowledge base,

To address the challenges of scale, context, and architectural complexity outlined in Section 1, our methodology is designed as a two-stage process. First, we transform the entire multirepository codebase into a compact and semantically rich NL Knowledge Base. Second, we employ a Two-Phase Search to efficiently navigate this knowledge base and pinpoint the source of a bug. This approach systematically converts a cross-modal search problem into a more effective NL-to-NL reasoning task.

The primary obstacle to applying LLMs on enterprise-scale systems is the finite context window. To overcome this, we construct a hierarchical representation of the codebase that is both compact and information-rich. This offline process involves two key steps.

Repository-Level Seed Context. The process begins by generating a high-quality, repository-level summary for each microservice, which serves as a “seed context.” This holistic summary ensures that lower-level descriptions understand their architectural role, a critical distinction shown in Figure 1. To generate this seed context, we prompt an LLM with a comprehensive set of artifacts, a process detailed in Figure 3:

• The Repository Tree: The directory and file structure.

• Source Code: A linearized version of the codebase (code snippets). • Processed Attachments: Project documentation, including READMEs and descriptive text extracted from diagrams (e.g., UML, ER) using a multi-modal OCR and Vision-Language Model (VLM) pipeline.

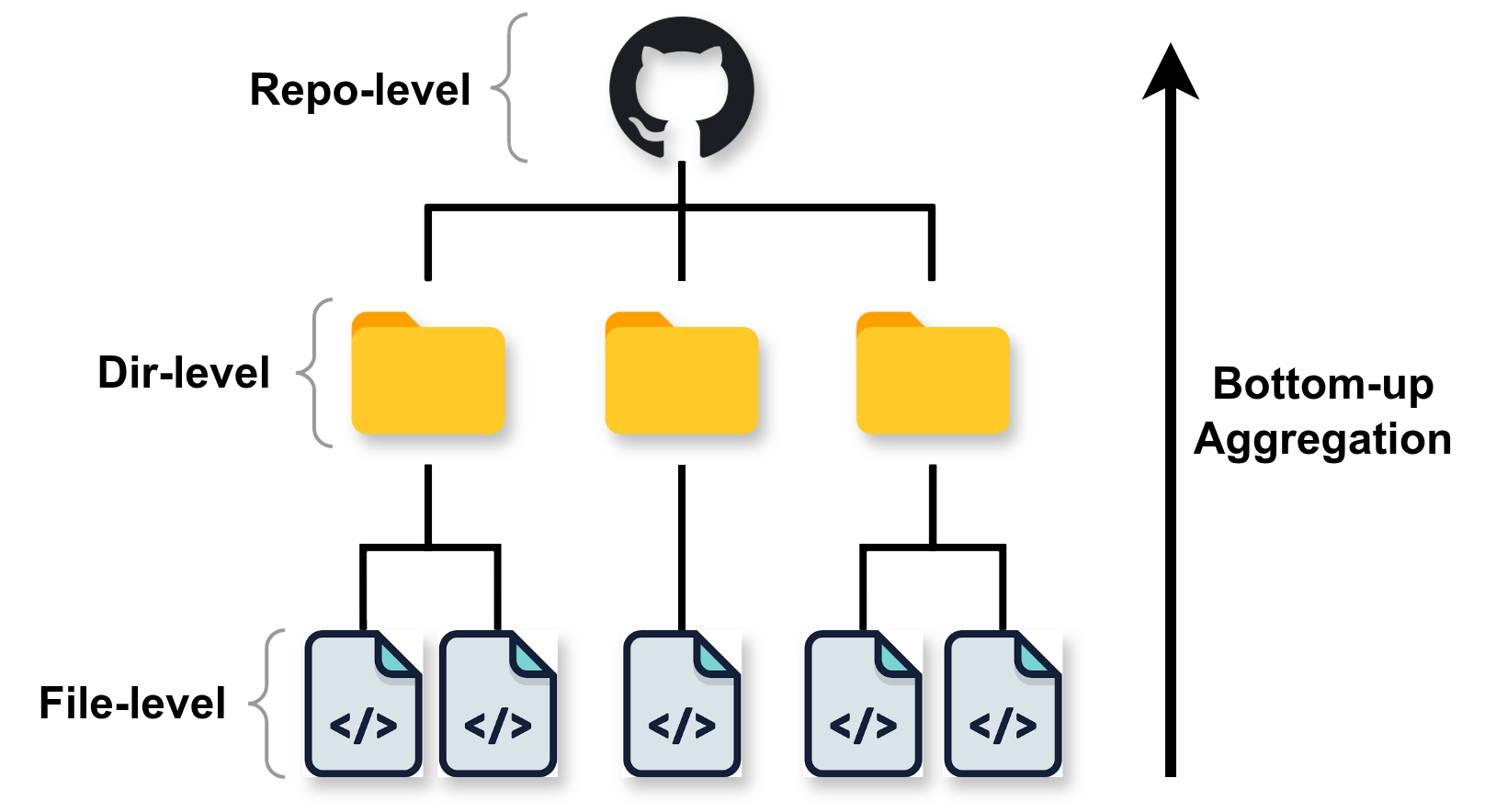

Bottom-Up Aggregation. With the seed context established, we then construct the knowledge tree in a bottom-up fashion (Figure 4). For each source file, an LLM is prompted with its raw code and the repository’s seed context to generate a concise, context-aware summary. These file-level summaries (the leaves of our tree) are then aggregated at the directory level. For each major directory (e.g., /service, /controller), its constituent file summaries are provided to the LLM to generate a coherent directory-level summary, forming the intermediate nodes of the knowledge tree.

During inference, we leverage the NL knowledge base to perform an efficient top-down search. This process is explicitly designed to handle the multi-repository nature of microservice architectures.

Phase 1: Search Space Routing. Given a bug report, the first challenge is to identify the correct microservice (repository). As illustrated in Figure 5, our framework routes the query by prompting an LLM to compare the bug report against the high-level, repository-level summaries of all microservices. This produces a ranked list of candidate repositories, ensuring the subsequent search is focused only on relevant code repositories.

Phase 2: Top-Down Bug Localization. Within each candidate repository, we perform a two-step hierarchical search to find the specific buggy file (Figure 6). First, the LLM performs Directory-Level Filtering by comparing the bug report against all directory-level summaries to identify the top-𝑘 most relevant directories. Second, the search space is narrowed to the files within these directories for a final File-Level Ranking. The LLM performs a detailed analysis of these filtered file summaries to produce the final ranked list of files most likely to be the source of the bug.

This structured repository → directory → file search path provides an inherently transparent and auditable reasoning process. 1 By decomposing the localization task into a series of explicit, verifiable steps, our method addresses the “black box” nature of many end-to-end systems, contributing to the goal of Explainable AI in developer tools.

We conduct an empirical study to evaluate our proposed architecture for LLM-based bug localization. Our evaluation aims to answer two primary questions: (1) How effectively does our NL-to-NL approach perform against state-of-the-art baselines on a complex, multi-repository benchmark? (2) How critical is the hierarchical search component to the method’s accuracy and efficiency?

Dataset. Our evaluation is performed on DNext [7], a proprietary, industrial-scale microservice system for the telecommunications sector. Its scale (see Table 1) and use of realworld, often noisy, bug reports provide a challenging benchmark that standard academic datasets cannot replicate. The ground truth for each bug ticket is the set of files modified in the pull request that resolved the issue. Baselines. We compare our method against two strong categories of baselines. For all LLM-based methods, including our own, we use the gpt-4.1 model to ensure a fair comparison of reasoning capabilities.

• Flat Retrieval: We use traditional IR baselines, UniXcoder [10] and GraphCodeBERT [11], to retrieve the most similar code files based on cosine similarity between embeddings. • Agentic RAG: We evaluate against state-of-the-art, repository-aware code assistants that operate on source code via RAG. We use two leading commercial systems: GitHub Copilot [9] and Cursor [4].

Metrics. We evaluate performance using standard metrics: Pass@k and Recall@k. Pass@k measures the proportion of bug reports where at least one correct file is found in the top-𝑘 results. Recall@k measures the fraction of all correct files for a given bug that are successfully retrieved within the top-𝑘 results. Given that the maximum number of modified files for any bug in our dataset is 10 (average 7.2), we set 𝑘 = 10 as a fair and comprehensive threshold that covers the full scope of a typical fix without artificially inflating scores with a large retrieval window. For the preliminary search space routing phase, we use a tighter 𝑘 = 3.

Search Space Routing Performance. Table 2 shows our method’s effectiveness at the critical first step: routing a bug to the correct microservice. Our summary-based router outperforms the Agentic RAG baselines on coverage metrics (Pass@3 and Recall@3). This is a crucial advantage for ambiguous bugs that may span multiple services, as our method is more likely to include all relevant repositories in the initial search space. Bug Localization Performance. Table 3 shows the end-toend file localization performance. Our hierarchical approach achieves the highest Pass@10 and MRR, indicating it is both more likely to find a correct file and to rank the first correct file higher than any baseline. It also matches the best-performing baseline (Cursor) on Recall@10, the metric most sensitive to multi-file bugs. These results validate our central hypothesis: a structured search over an NL knowledge base can be a more accurate and effective paradigm than retrieving from raw source code in some use cases.

To validate our claim that the hierarchical search is a critical component for both accuracy and efficiency, we conduct an ablation study. We compare our full method against an ablated version, which omits the directory-level filtering step. In this version, after routing to the correct repository, the LLM is prompted with the bug report and the summaries of all files within that repository to produce a final ranking directly. 0.23

The results of our ablation study, presented in Table 4, powerfully validate our central architectural claim. Removing the directory-level filtering step forces the LLM to solve a classic “needle-in-a-haystack” problem, searching for a few relevant files within the noisy context of an entire repository’s summaries. This leads to a catastrophic drop in performance across all metrics, with MRR plummeting by 54% and Recall@10 falling by 37%. In contrast, our hierarchical method acts as a cognitive scaffold, breaking the complex localization task into manageable steps to focus the LLM’s reasoning. This approach is not only substantially more accurate but also more scalable, as the ablated version requires a 44% increase in prompt tokens, making it prohibitively expensive and proving that our hierarchical design is critical for both performance and cost-effectiveness.

To understand why our NL-to-NL approach succeeds where retrieval fails, we present two case studies in Figure 7. These examples show how reasoning over the conceptual purpose of code, rather than just its keywords, allows our method to solve complex bugs.

Our work is situated at the intersection of code retrieval, LLM-based bug localization, and code summarization.

NL-to-PL Code Retrieval. The foundational challenge in bug localization is bridging the cross-modal gap between natural language (NL) and programming language (PL). Foundational models like CodeBERT [8], UniXcoder [10], and GraphCodeBERT [11] established the viability of joint NL-PL embeddings by incorporating code structure. While subsequent work has sought to mitigate the persistent vocabulary mismatch through techniques like dynamic execution features [18] or NL-augmented retrieval [3], these methods still operate on the difficult cross-modal boundary our NLto-NL approach is designed to circumvent.

LLMs for more sophisticated reasoning. Strategies include augmenting the query or code before retrieval [13,16], combining retrieval with iterative codebase analysis [1], or leveraging structured context via external memory [25] and code graphs [17]. State-of-the-art agentic frameworks like OrcaLoca [26] and COSIL [14] demonstrate impressive navigation, and hierarchical approaches like BugCerberus [2] use specialized models at different granularities. However, BugCerberus focuses on vertical granularity (File → Statement) within a single repository context. Despite their power, these frameworks are architecturally constrained to single-repository settings. They fundamentally lack a mechanism for multi-repository routing, making them unsuitable for modern microservice architectures where identifying the correct repository is the critical first step. Our two-phase framework directly addresses this critical gap.

Automatic Code Summarization. The field of automatic code summarization [22] provides the foundation for our representation engineering. Research has shown that code search is significantly improved when code snippets are paired with NL descriptions [12]. Recent advances have moved beyond method-level summaries to tackle higher-level units using hierarchical [6,19,20,23] and context-aware [21] generation strategies. While our previous work [19] demonstrated the feasibility of hierarchical summarization for single-repository contexts, this paper extends that foundation into a comprehensive framework for multi-repository microservice architectures. We introduce the Search Space Router to solve the critical “missing link” of repository identification and enhance the summarization strategy with context-aware propagation.

The Challenge: A successful tool must understand the code’s conditional business logic-why one PATCH operation behaves differently from another-not just find files related to “Account”.

Baseline Failure: The Agentic RAG retrieved generic files, such as:

• controller/PartyAccountController.java • model/FinancialAccount.java Analysis: This approach completely missed the nuanced validation logic central to the bug. Our Method’s Success: Our method identified the crucial service classes and, most importantly, the specific validator governing the patch operation:

• service/FinancialAccountService.java • validation/PartyAccountJsonPatch…Validator.java Analysis: By understanding the file’s architectural role, it pinpointed the exact component responsible for the faulty logic.

Case Study 2: Referential Integrity Bug Bug Report: “There’s a data integrity issue in order management. The system is allowing us to create new service orders that refer to service specifications that don’t actually exist in the catalog…”

The Challenge: The bug is caused by a missing validation check between two different business domains. The tool must reason about the expected interaction, not just search for existing code.

Baseline Failure: The Agentic RAG identified the general topic (‘ServiceOrder’) but returned irrelevant mappers and high-level application files:

• controller/ServiceOrderController.java • mapper/ServiceOrderMapper.java Analysis: It found the right topic but could not diagnose the specific, missing integrity check. Our Method’s Success: Our method correctly identified the specialized validator classes where the missing logic should have been implemented:

• validators/OrderItemServiceSpec…PatchValidator.java • util/ServiceSpecificationExistenceValidatorHelper.java Analysis: It succeeded by reasoning about the required interaction between system components, even when the code for it was absent. Critically, retrieval over NL summaries has been shown to be a viable alternative to searching over code [24]. While this body of work typically treats summaries as a documentation end-product, our key contribution is to systematically engineer these summaries into a task-specific intermediate representation. By doing so, we transform bug localization from a difficult cross-modal retrieval problem into a more tractable NL-to-NL reasoning task optimized for scale and architectural complexity.

Positioning Our Work. Our contribution is therefore not a new summarization model, but rather a novel act of representation engineering. We systematically apply established summarization techniques to build a purpose-built NL knowledge base, an intermediate representation designed specifically for the task of bug localization (which is a re-usable asset for other use-cases as mentioned in Section 5). This architectural pattern is the key that unlocks two distinct advantages over existing methods: it provides the holistic context necessary to solve the critical multi-repository routing problem, and it reframes the task into a unified NL-to-NL reasoning challenge that better leverages the semantic power of LLMs. Consequently, our framework is not only more scalable for complex microservice environments but also inherently more interpretable, offering a non-black-box reasoning path that is critical for enterprise adoption where developer trust is paramount.

Our empirical results validate our central hypothesis: for bug localization in complex systems, an engineered natural language representation of source code can be sometimes more effective than the code itself. Our findings, including the ablation study, confirm that the hierarchical search over this representation is not only more accurate but also more cost-effective. This section discusses the broader implications of this architectural shift and acknowledges the limitations of our work.

Implications for AI-Powered Developer Tools. This work has several practical implications for the design of future SE tools:

• A Scalable Architecture for Microservices: The singlerepository assumption of most current tools is a critical architectural limitation. Our two-phase framework offers a concrete, scalable solution for applying LLMbased reasoning to enterprise-scale, multi-repository systems-a ubiquitous industrial paradigm. • A New Paradigm via Reusable Knowledge Bases: The hierarchical NL knowledge base is a reusable asset.

Beyond bug localization, it can power a new class of developer tools for tasks like conceptual code search, automated onboarding of new engineers, and architectural analysis, similar to tools such as DeepWiki [5].

Our system is also capable of integrating with current code agents, allowing them to collaborate in identifying the location of the bugs and then resolving them. • Enhancing Trust through Interpretability: The “black box” nature of many AI tools is a barrier to enterprise adoption. Our method’s transparent reasoning path (repository → directory → file) is auditable by developers, fostering the trust required for effective human-AI collaboration in high-stakes environments, as discussed by [15].

Limitations and Future Work. Our study has two primary limitations. First, the initial generation of the knowledge base is computationally intensive. As detailed in Appendix D, while the initial construction of the hierarchical NL knowledge base is a one-time offline process, it introduces a non-negligible computational cost (≈$80 for DNext). In our industrial integration, this process is performed after each major release rather than after every commit. This scheduling choice is motivated by the nature of the generated summaries: since they capture the high-level purpose and architectural role of files rather than their exact implementation details, rapid implementation changes rarely invalidate them. However, as projects scale, both the cost and the maintenance scheduling algorithm for updating these summaries should be addressed in future work to improve efficiency and sustainability.

Second, our evaluation, while substantial, was conducted on a single large-scale industrial Java project. Validating the approach on projects in other languages (e.g., Python, Go) and architectural patterns (e.g., monolithic architectures) is an important next step for assessing generalizability.

Bug localization in modern, multi-repository software systems is a critical bottleneck where existing RAG-based tools fail due to architectural and context limitations. In this paper, we introduced a novel framework that reframes this challenge as a tractable NL-to-NL reasoning task. By systematically engineering source code into a hierarchical NL knowledge base and navigating it with a scalable, two-phase search, our approach improves upon strong RAG and retrieval baselines on a large-scale industrial benchmark. Ultimately, this work demonstrates the power of representation engineering in software engineering. By shifting the paradigm from retrieving over raw code to reasoning over a curated, human-understandable knowledge base, we open a promising new direction for AI-powered developer tools that are more scalable, accurate, and trustworthy.

Setup: The target microservice (repository) is opened as the root folder in the IDE (VS Code with GitHub Copilot / Cursor). The agent’s context is therefore limited to that single repository.

Prompt: You are a bug localizer. Given the bug description below, rank the top-10 files that likely cause the bug. Rank them in order of relevance. Setup: All 46 microservice repositories are opened together in a single workspace from their shared root directory. This allows the agent to see all folders simultaneously.

Prompt: You are a multi-repository bug localizer, selecting a search space within a large microservice architecture. Each microservice is represented as a folder in workspace. Given the bug description below, rank the top-3 microservices (folders) that likely cause the bug. Rank them in order of relevance.

To ensure a fair and reproducible comparison against the Agentic RAG baselines (GitHub Copilot and Cursor), we followed a standardized prompting procedure. Figures 8 and9 detail the exact setup and prompt templates used for both the multi-repository routing and file-level localization tasks.

All interactions with the Agentic RAG baselines were conducted using their respective interactive “Chat” or “Ask” modes to ensure the full reasoning capabilities of the underlying models were engaged. The specific versions used in our experiments were:

• GitHub Copilot: We utilized version v1.104 (release date: August 29, 2025) of the VS Code extension.

To provide further insight into our methodology, this section contains the core prompt templates used for both the offline knowledge base generation and the online bug localization phases. Figure 10 illustrates the six key prompts that power our framework. These templates are simplified for clarity but represent the essential structure and inputs provided to the LLM at each stage of the process.

To summarize the entire project and generate the hierarchical NL knowledge base, we used gpt-4.1-mini. The total cost for summarizing all repositories was approximately $80 (USD). While this is a manageable one-time cost in our industrial setting, it highlights the need for future research on scheduling algorithms to incrementally update and maintain summaries in a cost-efficient manner.

To enhance the quality of reasoning at each stage, all prompts used during the inference process explicitly leverage Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting techniques.

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.