FMA-Net++: Motion- and Exposure-Aware Real-World Joint Video Super-Resolution and Deblurring

📝 Original Info

- Title: FMA-Net++: Motion- and Exposure-Aware Real-World Joint Video Super-Resolution and Deblurring

- ArXiv ID: 2512.04390

- Date: 2025-12-04

- Authors: Geunhyuk Youk, Jihyong Oh, Munchurl Kim

📝 Abstract

a) Qualitative comparison on challenging real-world videos. (b) Quantitative comparison on the GoPro [33] dataset. Figure 1. FMA-Net++ outperforms state-of-the-art methods in real-world qualitative results and quantitative benchmarks for VSRDB.📄 Full Content

While significant progress has been made in various video restoration [5,29,37,54], most existing methods assume a fixed exposure time. This assumption severely limits their robustness, as they struggle to handle the dynamically changing blur severity arising from real-world exposure variations. For instance, VSR [3,5,17,26,31] and video deblurring [25,[57][58][59]61] approaches may produce artifacts or inconsistent results when faced with exposure shifts. Even methods designed for unknown degradations, such as Blind VSR [1,24,37], typically assume spatiallyinvariant kernels and fail to model the physical process coupling motion and varying exposure. Furthermore, recent VSRDB approaches like FMA-Net [54], despite handling motion-dependent degradation, remained constrained by its fixed-exposure assumption. Thus, VSRDB methods explicitly addressing dynamic exposure are critically needed.

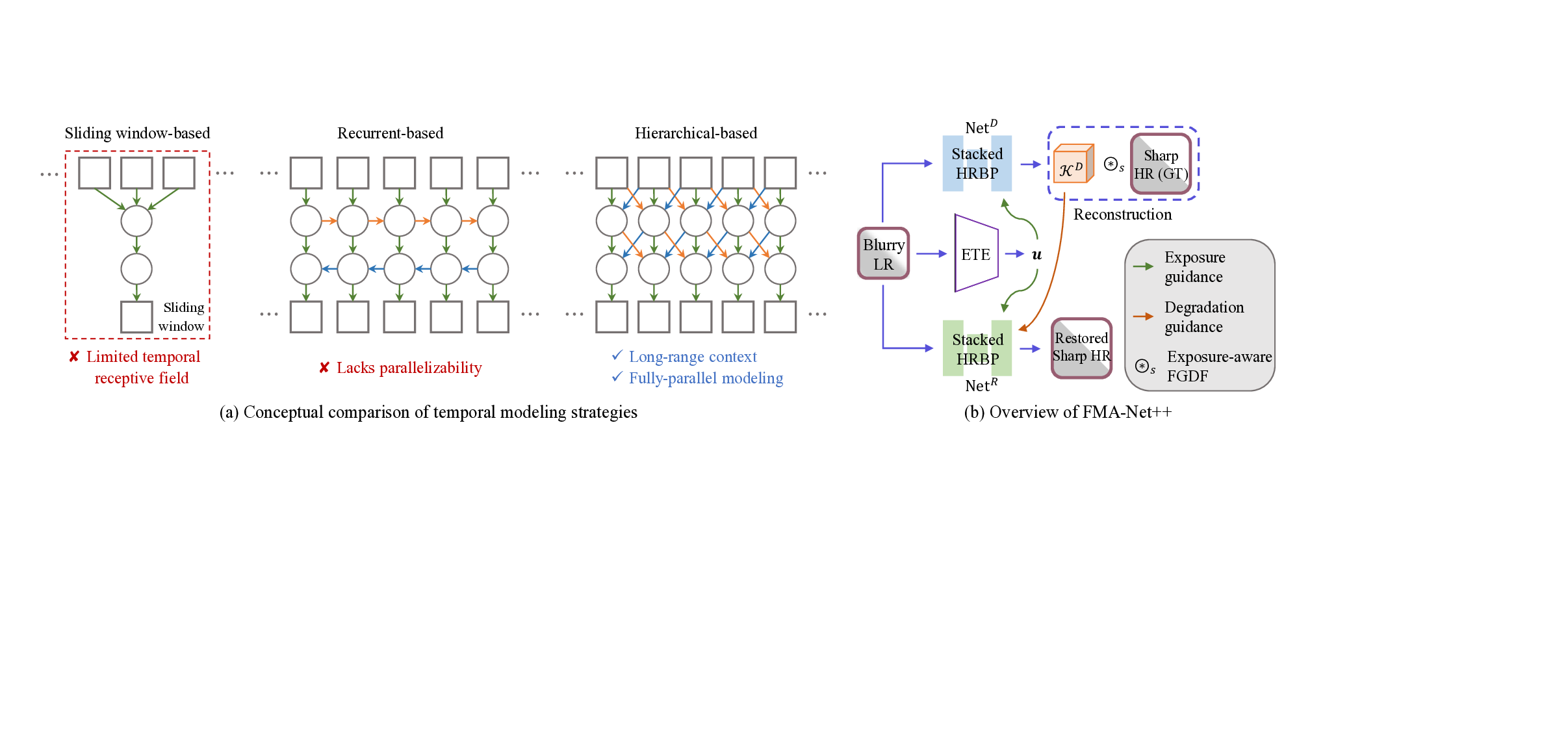

Furthermore, beyond the exposure issue, prevailing temporal modeling strategies face inherent limitations: Slidingwindow architectures [17,26,43,46] tend to suffer from limited temporal receptive fields, while recurrent propagation [3,5,12,30,31] lacks parallelizability, as conceptually compared in Fig. 2(a). To overcome these limits and address the aforementioned exposure issue, we introduce FMA-Net++, a sequence-level framework that explicitly models motion-exposure coupling to guide restoration.

The core architectural unit of FMA-Net++ is the Hierarchical Refinement with Bidirectional Propagation (HRBP) block. Instead of relying on restrictive sliding windows, such as those in FMA-Net [54], or inherently sequential recurrent structures [3,5,31], stacking HRBP blocks enables sequence-level parallelization and hierarchically expands the temporal receptive field to capture long-range dependencies. To handle dynamic exposure for which other methods [5,18,53,54,58] fail, each HRBP block includes an Exposure Time-aware Modulation (ETM) layer that conditions features on per-frame exposure, producing rich representations in temporal context and exposure information. Leveraging these representations, an exposure-aware Flow-Guided Dynamic Filtering (FGDF) module estimates physically grounded, motion-and exposure-aware joint degradation kernels. Architecturally, we decouple degradation learning from restoration: the former predicts these rich priors, and the latter utilizes them to restore sharp HR frames efficiently, as illustrated in Fig. 2(b).

To enable realistic and comprehensive evaluation, we construct two new benchmarks, REDS-ME (multiexposure) and REDS-RE (random-exposure). Trained solely on synthetic data, FMA-Net++ achieves state-ofthe-art (SOTA) accuracy and temporal consistency on our new benchmarks and the GoPro [33] dataset, outperforming recent methods in both restoration quality and inference speed, and showing strong generalization to challenging real-world videos (see Fig. 1).

The main contributions of this work are as follows: or video deblurring [25,29,58,59,64] have advanced, applying them sequentially often amplifies artifacts [36,54]. However, specific methods tackling this joint VSRDB challenge remain scarce, as the field has received relatively little attention until recently. HOFFR [11], an early deep learning approach, showed promise but struggled with spatially variant blur due to standard CNN limitations. Although FMA-Net [54] introduced Flow-Guided Dynamic Filtering (FGDF) to handle motion-dependent degradation, it remained constrained by a sliding-window design with an inherently limited temporal receptive field and a fixedexposure assumption, making our approach conceptually distinct in both architecture and problem formulation. More recently, Ev-DeblurVSR [18] attempted to enhance VS-RDB by incorporating auxiliary data from event streams (either simulated or captured by event cameras), proposing modules to fuse event signals for deblurring and alignment. However, this approach requires event data unavailable in standard videos and still assumes a known and fixed exposure time, a limitation explicitly discussed in [18], failing to address the challenges of dynamic exposure variations. These gaps motivate a sequence-level, exposure-aware approach for robust VSRDB using only standard RGB inputs.

Effectively modeling long-range temporal dependencies is crucial for video restoration tasks like VSR. However, prevailing strategies face inherent architectural trade-offs.

Sliding-window approaches [17,26,41,50,54] operate on fixed local neighborhoods, constraining input flexibility and limiting the capture of long-range context. Conversely, recurrent methods [3,5,29,31] propagate information sequentially, enabling longer temporal aggregation but remaining inherently sequential (hence less parallelizable) and potentially prone to vanishing gradients over long sequences [8,31]. Transformer variants [2,26,28] alleviate some issues but are often still applied within a slidingwindow context or incur significant computational complexity. Furthermore, most of these works target sharp inputs, lacking robustness to complex real-world degradations. This landscape motivates the need for sequencelevel backbones that hierarchically expand temporal receptive fields while enabling efficient parallel processing.

In real-world videos, auto-exposure mechanisms often vary the exposure time across frames, yielding spatio-temporally variant blur that fixed-exposure models cannot faithfully capture [21,38,52]. While most video restoration methods commonly assume a fixed exposure [3,5,17,26,28,29,43], recent efforts in related tasks (e.g., video deblurring [21,38] and frame interpolation [38,52,60]) estimate exposure or exploit auxiliary sensing (events) to guide restoration. However, they do not explicitly model the joint effects of motion and exposure within the VSRDB setting, and event-dependent designs limit practicality for standard RGB videos. We instead introduce an Exposure Timeaware Modulation (ETM) layer that injects per-frame exposure information into temporal features and conditions the learning of degradation priors. In particular, we extend Flow-Guided Dynamic Filtering (FGDF) [54] to incorporate these exposure-aware features, yielding jointly position-, motion-, and exposure-dependent kernels that are physically grounded by the capture process, denoted as exposure-aware FGDF. This design enables exposure-aware VSRDB using only conventional RGB inputs and integrates seamlessly with our sequence-level backbone.

We address joint VSRDB under frame-wise varying exposure, where the per-frame exposure time ∆t e,i is unknown at test time. Given the blurry LR video X = {X i } T i=1 ∈ R T ×H×W ×3 , our goal is to restore the corresponding sharp

, where s denotes an upscaling factor. The blur in X i arises physically from integrating a latent sharp signal over the exposure interval ∆t e,i while the scene moves [33,38]. We approximate this complex process using a discrete, learnable formulation with a spatio-temporally variant, position-dependent degradation kernel K i :

where * s denotes a filtering operation with stride s, and

. . , Y i+k } is a short temporal neighborhood of sharp HR frames for a small temporal radius k. Conceptually, the kernel K i captures the joint effects of the exposure time ∆t e,i and the local motion field, which together determine the effective spatio-temporal receptive field integrated by each LR pixel.

Our framework is designed to solve the corresponding inverse problem in two steps: first, estimate the exposureand motion-aware degradation priors (including the perframe kernels {K i } T i=1 and associated motion information) directly from the input X; second, use these estimated priors to guide the restoration of Ŷ . Detailed physics-based derivations are provided in Sec. 7.1 of Suppl.

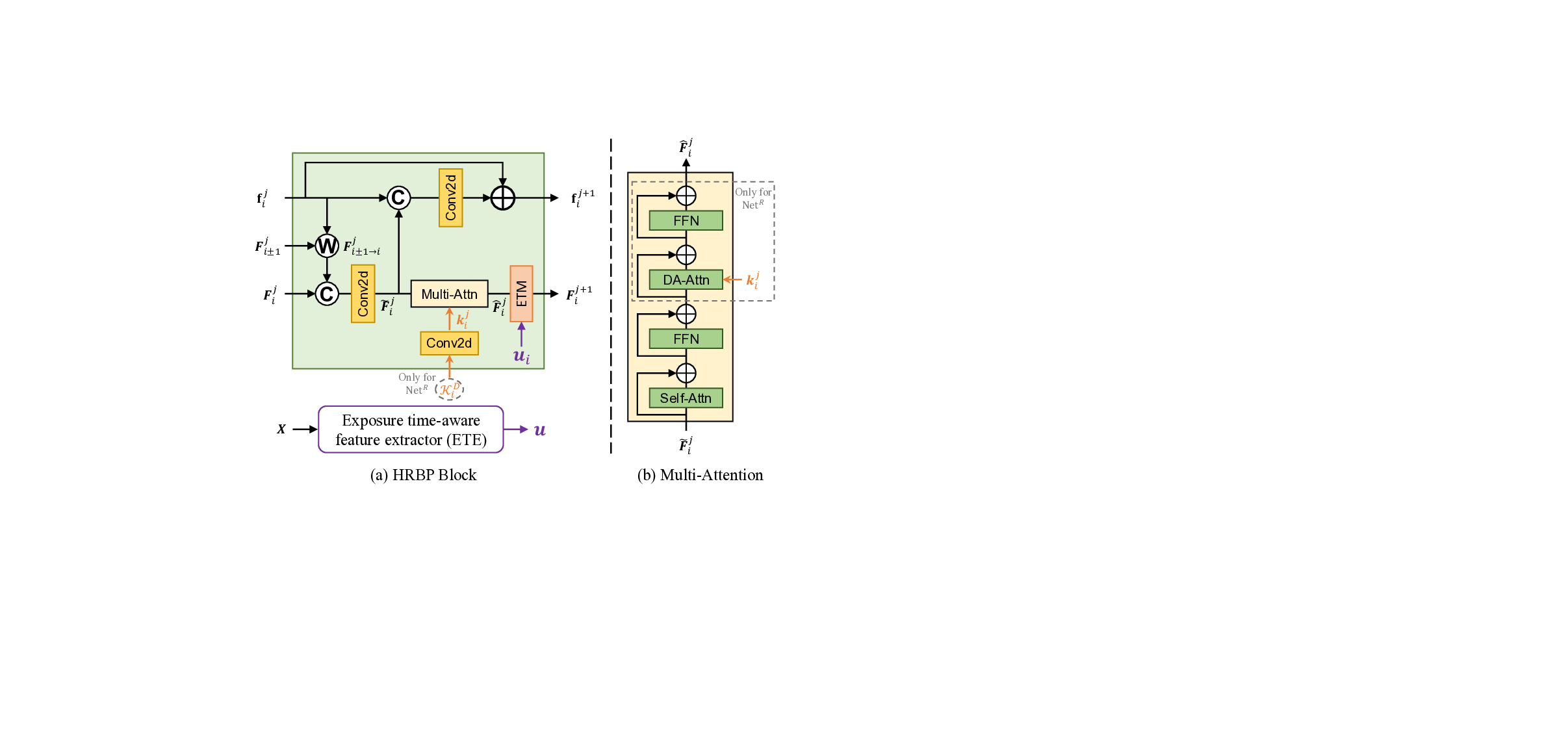

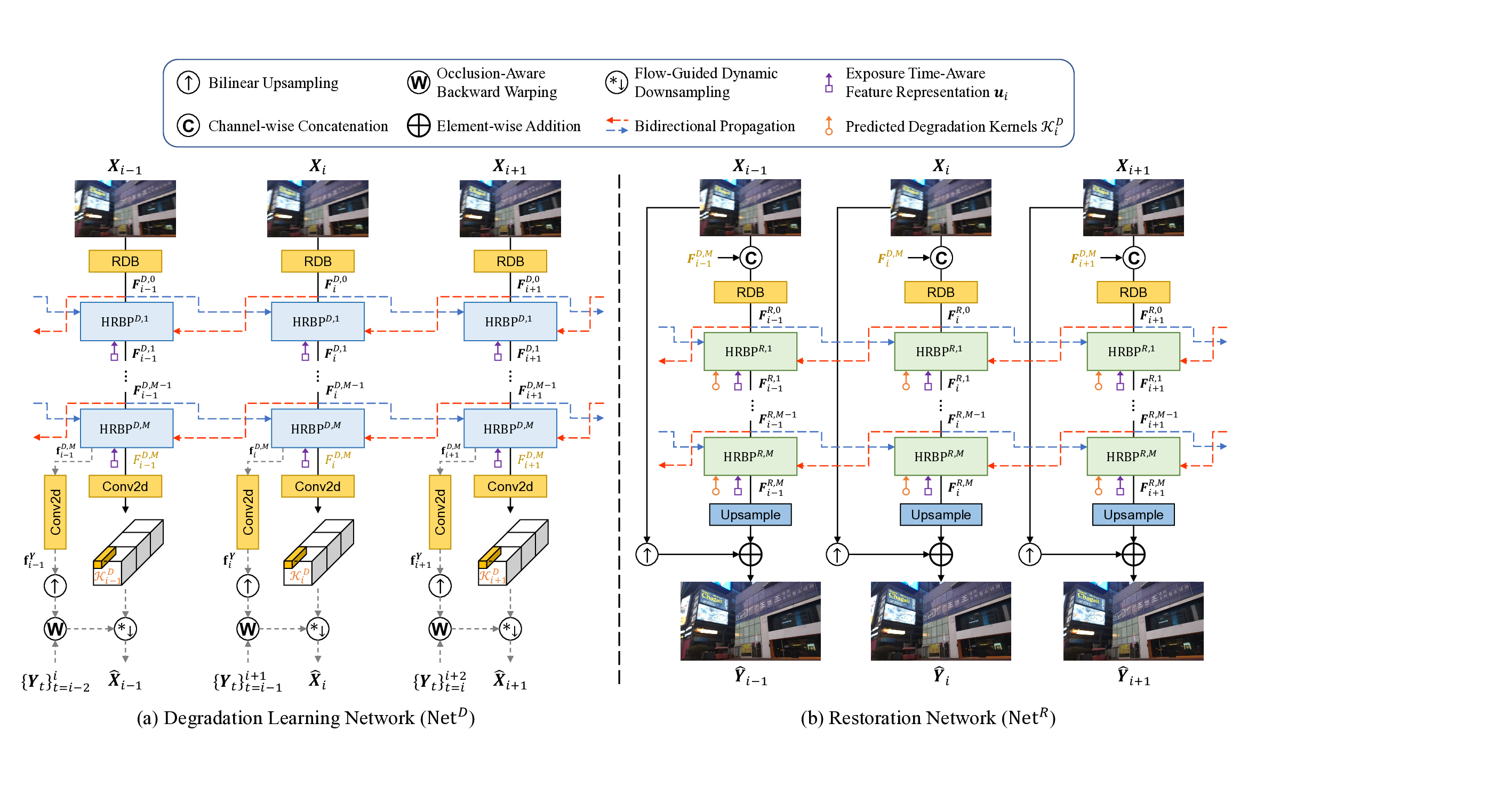

FMA-Net++ consists of two main networks: a Degradation Learning Network (Net D ) and a Restoration Network (Net R ), both guided by a pretrained Exposure Timeaware Feature Extractor (ETE). As illustrated in Fig. 3, both Net D and Net R are built upon stacks of HRBP blocks, which enable sequence-level parallel processing while hierarchically expanding the temporal receptive field.

Given an input blurry LR sequence X, Net D first estimates degradation priors through the combination of HRBP, ETM, and the exposure-aware FGDF module, explicitly modeling spatio-temporally variant degradations. Net R then restores the sharp HR video Ŷ guided by these priors, also incorporating ETM to ensure exposure-aware feature adaptation during restoration. This decoupled design separates degradation learning from restoration, improving both accuracy and efficiency.

As the core architectural unit shared by both Net D and Net R , the HRBP block overcomes the fundamental tradeoffs faced by prior temporal modeling strategies (Sec. 2.2): namely, limited temporal receptive fields in sliding-window methods [50,54] and the lack of parallelizability in sequential recurrent approaches [5,29]. By stacking HRBP blocks, our architecture enables sequence-level parallel processing.

At each refinement level, information from increasingly distant past and future frames is aggregated bidirectionally, thus hierarchically expanding the temporal receptive field to effectively capture long-range dependencies.

As shown in Fig. 4(a), each HRBP block iteratively refines the feature map F j i ∈ R H×W ×C and a set of multiflow-mask pairs f j i ∈ R 2×H×W ×(2+1)n for a given frame i at refinement step j + 1. Specifically, f j i is defined as:

where n is the number of multi-flow-mask pairs, each containing an optical flow f and corresponding occlusion mask o representing motion towards neighbors i ± 1. Keeping multiple motion hypotheses (n > 1) enhances robustness under severe blur by providing one-to-many correspondences [4,14]. The refinement process first computes intermediate features F j i via occlusion-aware warping [15,36] of neighboring features F j i±1 using f j i , followed by fusion using concatenation and convolution. The multi-flow-mask pairs are then updated residually, f j+1 i = f j i + ∆f j i , where the residual ∆f j i is predicted based on F j i and f j i . The intermediate feature F j i is further enhanced through two crucial modules before producing the final output F j+1 i . Multi-Attention. As shown in Fig. 4(b), the multi-attention module employs self-attention [45] to capture spatial dependencies and integrate the propagated hierarchical temporal context. Within Net R , it subsequently applies Degradation-Aware (DA) attention. This cross-attention mechanism uses query Q derived from the estimated exposure-and motionaware degradation kernel K D i (predicted by Net D ), while key K and value V are projected from the self-attention output. This allows Net R features to adapt specifically to the estimated degradation characteristics of each frame. Exposure Time-aware Modulation (ETM). To handle frame-wise exposure variation, every HRBP block applies ETM via a lightweight SFT layer [47]. Conditioned on a per-frame exposure embedding u i ∈ R 1×C from the pretrained ETE, it predicts affine parameters (α, β) = M(u i ) via a shallow network M and modulates the attention output F j i as

This injects essential exposure information into all refinement stages with negligible overhead, enabling adaptation to dynamic exposure variations (see detailed formulations in Sec. 7.2 of Suppl).

In summary, compared to sliding windows [17,26,41,50,54], HRBP accesses long-range context via hierarchical propagation. Compared to recurrent schemes [3,5,29,31], it avoids sequential dependencies, enabling efficient parallelization and stable training on long sequences.

Conventional dynamic filtering [16] struggles with motion blur due to its fixed local neighborhood. FGDF [54] addresses this by performing filtering along motion trajectories. Instead of fixed neighbors, FGDF uses estimated optical flow to dynamically guide sampling locations for compact, position-dependent filter weights W p . Formally, for a reference frame r, the output y r (p) at a pixel position p is computed as:

where N (r) denotes the temporal neighborhood of r, x t→r is the neighbor feature warped to r using the estimated flow and occlusion masks, W p t are the predicted weights at p for neighbor t, and p k indexes the m × m spatial offsets. This formulation generalizes the original FGDF [54] (which focused on the center frame) to arbitrary reference frames.

In FMA-Net++, we crucially extend this FGDF mechanism specifically for modeling exposure-varying degradations. Leveraging the exposure-aware features produced by the HRBP blocks (Sec. 3.3), the FGDF module within Net D operates on features already infused with exposure information by the ETM layer. Consequently, the predicted filter weights W p t become jointly motion-aware (via flow guidance) and exposure-aware (conditioned on ETM features), enabling more physically grounded degradation modeling that captures the coupled effects of motion and exposure. Aligning with our decoupled design for efficiency, this exposure-aware FGDF is employed exclusively within Net D for prior estimation, while Net R uses a simpler upsampling strategy (Sec. 3.5).

As outlined in Sec. 3.2 and illustrated in Fig. 3, our framework comprises two main networks leveraging the HRBP backbone to solve the inverse problem defined in Sec. 3.1. Degradation Learning Network (Net D ). Net D aims to estimate degradation priors from the input blurry LR sequence X. It processes X through a stack of HRBP blocks with integrated ETM layers, producing refined features F D,M and multi-flow-mask pairs f D,M . From these outputs, Net D predicts two key priors for each frame

, representing motion between the sharp HR frame Y i and its neighbors, and (ii) jointly exposure-and motion-aware degradation kernels

, predicted via the exposureaware FGDF module (Sec. 3.4). This kernel formulation, representing the degradation from three consecutive sharp HR frames {Y i-1 , Y i , Y i+1 } to the blurry LR frame X i , follows the design principle of [54] as it offers a robust trade-off between performance and computational cost. The shape of K D i explicitly reflects its spatio-temporally variant and position-dependent nature, providing a physically meaningful parameterization essential for modeling complex real-world degradations.

To ensure accurate prior estimation, Net D is trained with a reconstruction objective: the predicted priors must reconstruct the blurry LR frame Xi from the ground-truth (GT) sharp HR frames Y as:

where ⊛ s denotes exposure-aware FGDF operation (Eq. 3) with stride s, and warped HR frame Y t→i is defined as:

where W denotes the occlusion-aware backward warping.

Restoration Network (Net R ). Net R performs the final restoration, taking the blurry LR sequence X along with the rich priors predicted by Net D (F D,M , f D,M , and K D ) as input. It first generates initial features by combining X and the context feature F D,M using concatenation and an RDB [49]. These features are then refined through another stack of HRBP blocks, initializing the multi-flowmask pairs with f D,M from Net D to leverage the motion prior. Crucially, within each HRBP block in Net R , the DA attention utilizes the estimated kernel K D i as its query, after which ETM continues to provide exposure conditioning, enabling degradation-and exposure-adaptive restoration. Finally, the refined features F R,M pass through an upsampling block to predict a high-frequency residual Ŷ res i . The final sharp HR frame is obtained by adding this residual to the bilinearly upsampled blurry LR input:

where ↑ s denotes the ×s bilinear upsampling.

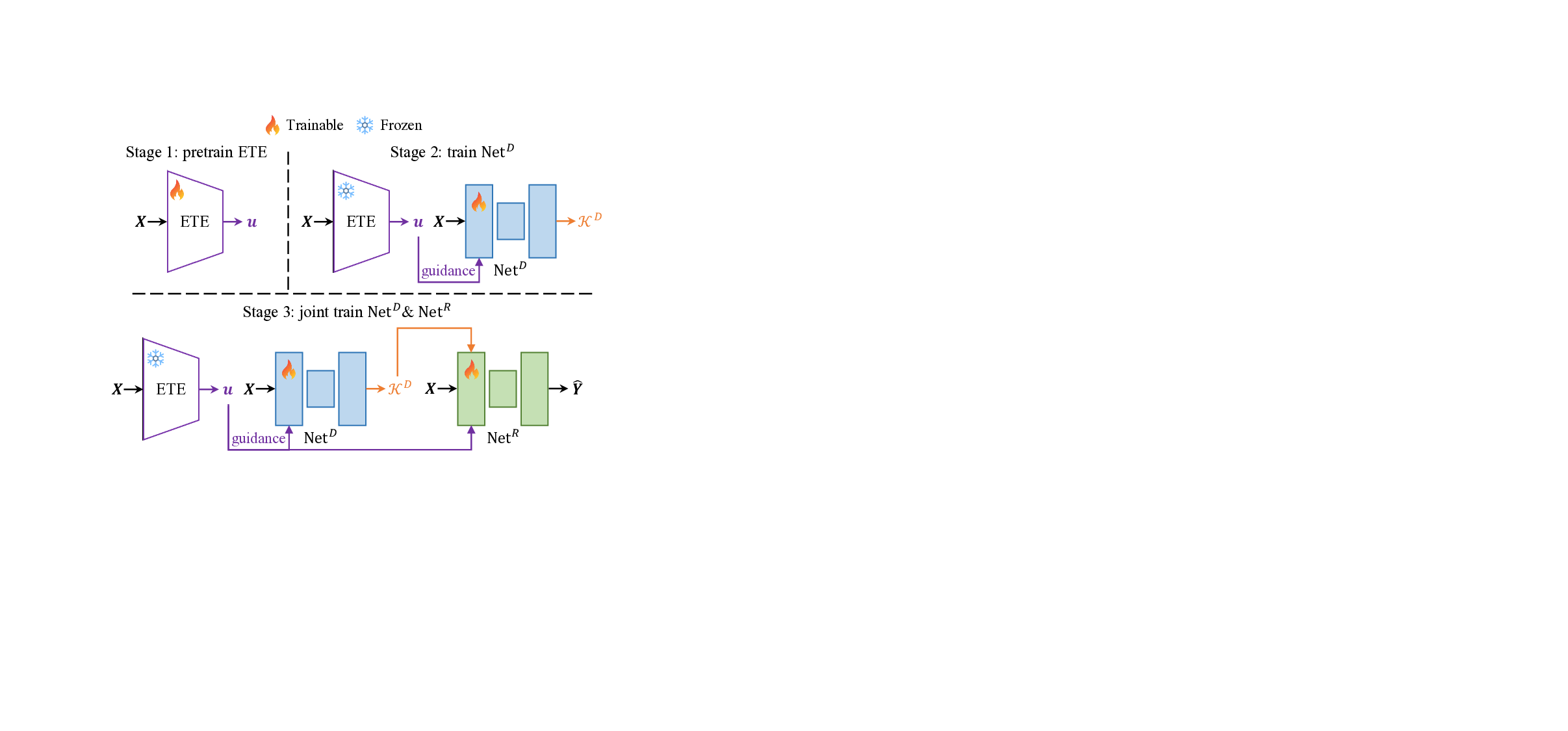

We adopt a three-stage training strategy to effectively optimize FMA-Net++. First, the ETE is pretrained using a supervised contrastive loss [20] on exposure labels to provide reliable guidance features, after which it is frozen. Second, guided by the pretrained ETE, Net D is trained to predict physically plausible degradation priors using reconstruction and motion prior losses. Finally, the entire FMA-Net++ framework (Net D and Net R ) is jointly trained endto-end using restoration loss on the final sharp HR output. Detailed loss formulations and hyperparameter settings are provided in Sec. 7.3 and Sec. 8.1 of Suppl.

Datasets. We train FMA-Net++ on the proposed REDS-ME dataset, derived from REDS [34], utilizing all five synthesized exposure levels (from 5 : 1 to 5 : 5). The data generation process follows standard protocol [33,34] and is detailed in Sec. 8.2 of Suppl. To evaluate, we use the most challenging levels (5 : 4, 5 : 5) of REDS4-ME (derived from the REDS4 test set). We also employ our proposed REDS-RE benchmark, which is derived from REDS4-ME by temporally mixing frames across all five exposure levels to assess robustness to dynamic exposure variations, along with the GoPro dataset [33] for generalization and challenging real-world videos. Evaluation Metrics. We evaluate restoration quality using PSNR and SSIM [51]. Temporal consistency is measured by tOF [9]. For real-world videos where GT is unavailable, we report no-reference metrics such as NIQE [32] and MUSIQ [19]. We also compare model efficiency in terms of the number of parameters and the runtime. Implementation Details. All implementation details, including network configurations, loss functions, etc., are provided in Sec. 8.1 of Suppl. for reproducibility.

We compare FMA-Net++ against SOTA methods across relevant categories: single-image SR (SwinIR [27], HAT [7]), single-image deblurring (Restormer [55], FFTformer [23]), VSR (BasicVSR++ [5], IART [53]), video deblurring (RVRT [29], BSSTNet [58]), Blind VSR (DBVSR [37]), and joint VSRDB (FMA-Net [54], Ev-DeblurVSR [18]). For a fair comparison in the joint VS-RDB setting under dynamic exposure conditions, relevant SOTA methods were adapted and retrained on our REDS-ME training set, denoted by * in Tables 1 and2.

Quantitative Results. Table 1 presents the performance on REDS4-ME across two challenging exposure levels (5 : 4 It achieves remarkably higher performance while being significantly faster (over 5.2× speedup). This efficiency primarily arises from our parallelizable HRBP architecture.

Combined with the high accuracy, this highlights the effectiveness of our overall design. The benefits of our upsampling choice are analyzed in the ablation study (Sec. 5.3). Table 2 evaluates robustness to dynamic exposure (REDS-RE) and generalization ability to an unseen dataset (GoPro [33]). On REDS-RE, featuring dynamic exposure transitions within sequences, the performance advantage of FMA-Net++ over other methods widens considerably compared to REDS-ME. This result strongly validates the effectiveness of our explicit exposure-aware modeling (ETM) in adapting to realistic varying exposure conditions where fixed-exposure assumptions struggle. On the unseen GoPro dataset, which exhibits different motion and scene characteristics from REDS-ME, FMA-Net++ again achieves the best performance across all metrics, indicating a strong generalization ability beyond the training domain.

Qualitative Results. Fig. 5 presents visual comparisons on synthetic benchmarks (REDS4-ME-5 : 5 and GoPro) that contain severe motion blur, while Fig. 1(a) shows results on challenging real-world videos captured with a smartphone. On both synthetic and real-world data, FMA-Net++ consistently restores sharper details, cleaner edges, and more legible text with fewer artifacts, achieving the best perceptual quality (NIQE/MUSIQ). We omit multi-modal methods such as Ev-DeblurVSR [18] from the real-world comparison, as they are fundamentally not applicable to standard RGB videos that lack the required event data. This highlights the strong practicality and generalization of our approach, which achieves these results using only conventional RGB inputs despite being trained solely on synthetic data. Further qualitative results are provided in Sec. 10 of Suppl.

We present ablation studies validating our key design choices. Further ablation studies and detailed analyses can be found in Sec. 9 of Suppl.

To validate the advantages of our proposed hierarchical temporal architecture, which is conceptually compared with other temporal modeling strategies in Fig. 2(a), we quantitatively verify its effectiveness by comparing the full FMA-Net++ against two variants built upon its core components but employing different temporal modeling strategies: (i) a sliding-window version processing three frames at a time, similar to [54], and (ii) a recurrent version where the hierarchical refinement is adapted for sequential propagation.

All variants maintain the same number of HRBP blocks and utilize identical ETM and multi-attention mechanisms. Table 3 presents the comparison results on REDS4-ME-5 : 5. Our hierarchical FMA-Net++ demonstrates substantial improvements over both variants. Compared to the slidingwindow variant, it yields markedly better results across all metrics, effectively overcoming the limitations imposed by a fixed temporal receptive field. Compared to the recurrent variant, it still achieves superior performance in both PSNR and tOF. The noticeable gain in temporal consistency might stem from its non-recurrent hierarchical structure, which mitigates gradient-vanishing issues that can affect sequential propagation over long sequences. We also empirically observe that this design achieves the most stable training dynamics among the compared variants. Furthermore, in terms of efficiency, the hierarchical design also demonstrates a modest speed advantage over the recurrent approach. Overall, these results validate that our hierarchical strategy serves as a highly effective backbone for highquality and temporally consistent video restoration.

We evaluate the contribution of our explicit exposure-aware modeling pipeline by comparing the full FMA-Net++ with ETE guidance against a variant trained and tested without the ETE module. Table 4 summarizes the performance across multiple datasets.

Incorporating ETE consistently improves both PSNR and tOF across all test sets. While the improvements on the in-distribution test sets (REDS4-ME-5 : 4 and 5 : 5) are noticeable, the performance gains become considerably more pronounced on the out-of-distribution datasets. Specifically, on REDS-RE, which features dynamic exposure transitions, and on the unseen GoPro dataset with different degradation characteristics, the advantage of using ETE widens significantly. This highlights that explicitly conditioning the features via ETM, guided by the ETE, is crucial for enhancing the model’s robustness and generalization ability when facing dynamically changing or entirely novel exposure conditions encountered in real-world scenarios. See more analyses and visual results in Sec. 9.1 of Suppl.

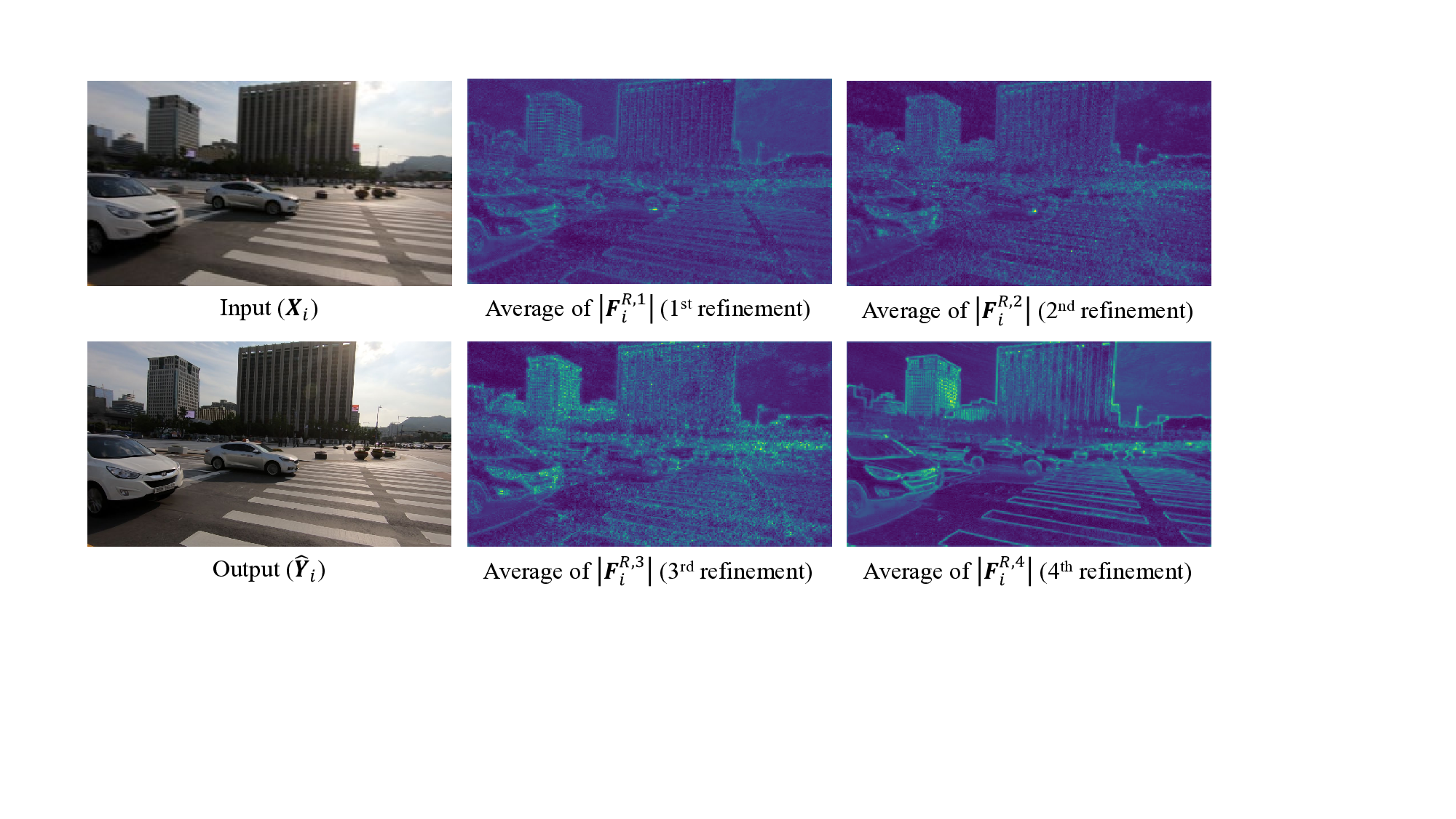

We conduct ablation studies to validate the key components and design choices of FMA-Net++, summarizing the main results in Table 5. First, we investigate the impact of our hierarchical refinement strategy by varying the number of stacked HRBP blocks (M ). As shown in Table 5(a, b, e), increasing M from 1 to 2 and finally to our full configuration (M = 4, row e) progressively improves both PSNR and tOF. This demonstrates the effectiveness of hierarchically expanding the temporal receptive field. As visualized in Fig. 11 of Suppl, features become progressively sharper and more structurally aligned through the stacked blocks, further validating our hierarchical design.

Next, we validate the effectiveness of the Degradation-Aware (DA) attention within Net R ’s multi-attention module. Replacing DA attention with a standard SFT layer [48] for modulation significantly degrades performance, confirming that explicitly leveraging the estimated degradation priors via DA attention is crucial for targeted restoration.

Finally, we analyze our asymmetric design choice for efficiency. Compared to a symmetric variant employing the complex FGDF for upsampling in Net R as well, our default approach (using bilinear upsampling plus residual) achieves comparable PSNR and tOF with approximately 1.1M fewer parameters and ∼15% faster inference. Given the marginal accuracy differences relative to the higher cost, we adopt the lightweight upsampling choice in our main model.

In this paper, we addressed the challenging problem of joint VSRDB under unknown and dynamically varying exposure conditions. To tackle this challenge, we introduced FMA-Net++, a novel framework built upon HRBP blocks that enables effective sequence-level temporal modeling with efficient parallel processing. Crucially, our proposed ETM layer injects per-frame exposure conditioning into the features. This allows our exposure-aware FGDF module to predict physically grounded degradation kernels that capture the coupled effects of motion and exposure. Extensive experiments on the proposed REDS-ME and REDS-RE benchmarks, as well as GoPro and real-world videos, demonstrate that FMA-Net++ achieves SOTA results, showcasing superior performance, efficiency, and robustness while generalizing effectively despite being trained solely on synthetic data.

In this Supplementary Materials, we first provide the detailed formulations of our method, including the physicsbased degradation model, full equations for our HRBP block, and detailed loss functions (Sec. 7). Subsequently, we detail the implementation and training setup, including network architectures and our new dataset generation pipeline (Sec. 8). Additionally, we present further ablation studies and visual analyses that validate our design choices (Sec. 9). We also provide additional qualitative comparisons on synthetic and real-world videos (Sec. 10). Finally, we discuss the limitations of our FMA-Net++ (Sec. 11).

As mentioned in Sec. 3.1 of the main paper, we address VSRDB under dynamically varying exposure. While most existing video restoration methods [3,5,29] have advanced temporal modeling, they typically assume a fixed exposure time and do not explicitly address the impact of frame-wise dynamic exposure on the degradation model. Physics-based Degradation Model. A foundational model in video deblurring [33] models blur formation as the temporal integration of a latent sharp scene over a fixed exposure interval ∆t e :

where B is the blurry frame and S(τ ) is the latent sensor signal at continuous time τ . While this captures the core idea of temporal integration, it simplifies the process by not explicitly accounting for the continuous motion field or dynamically varying exposure.

We generalize this physical model to incorporate these crucial real-world factors. The degradation process for the i-th blurry LR frame X i at position p is more accurately defined as:

where D s is the spatial downsampling operator, q is the HR coordinate corresponding to p, ∆t denotes the frame interval, ∆t e,i is the unknown, per-frame dynamic exposure time, and S(•, τ ) is the latent sensor signal displaced by the continuous motion field M (q, τ ). Learnable Degradation Kernel Formulation. Since directly inverting the continuous physical model (Eq. 8) is intractable, we approximate it with a discrete, learnable model, as shown in Eq. 1 of the main paper:

where

. . , Y i+k } is a short temporal neighborhood of sharp HR frames for a small temporal radius k.

To be rigorous, the ideal conceptual kernel K i at a position p is a complex function F of both the exposure time ∆t e,i and the local motion field M :

where Ω (p) denotes the spatial neighborhood of HR coordinates corresponding to the LR pixel p, and the range of τ defines the temporal integration interval. This formulation (Eq. 10) explicitly shows how exposure and motion jointly create the spatio-temporally variant blur.

Our framework learns to approximate this ideal kernel. The kernel predicted by our network, K D i , is a practical, learnable approximation of K i . Our Net D achieves this by using the pretrained ETE to estimate the properties of ∆t e,i and using learned optical flow to approximate the continuous motion field M . The FGDF module is then explicitly conditioned on both estimated parameters to predict K D i , ensuring it is a physically-plausible representation of the real-world degradation.

We provide the detailed update equations for the Hierarchical Refinement with Bidirectional Propagation (HRBP) block, expanding upon Sec. 3.3 of the main paper. Feature Refinement. As shown in Fig. 4(a) of the main paper, the intermediate refined feature F j i and the updated multi-flow-mask pairs f j+1 i are computed as:

where W denotes the occlusion-aware backward warping [15,36,39]. Multi-Attention. As shown in Fig. 4(b) of the main paper, the Degradation-Aware (DA) attention in Net R uses a query derived from the predicted degradation kernel K D i . This degradation feature k j i is computed as: The final DA attention output is then computed using standard attention [10,45]:

where Q is projected from k j i , and K, V are projected from the self-attention output. Exposure Time-aware Modulation (ETM). The ETE module, which extracts the guidance signal u i ∈ R 1×C from the input frame X i , consists of a ResNet-18 [13] backbone. It is pretrained to distinguish exposure settings using supervised contrastive learning [20]. The shallow network M j predicting the affine parameters (α, β) for the SFT layer [47] is implemented using simple convolutional layers. The modulation is applied as:

where F j i is the feature map from the multi-attention module.

We adopt a three-stage training strategy to effectively and stably train the components of FMA-Net++. This progressive approach ensures that each specialized module is welloptimized before being integrated into the full framework. Fig. 6 provides a schematic overview of this strategy.

We first pretrain the ETE to provide a reliable guidance signal. This staged approach is adopted for two critical reasons. First, supervised contrastive learning [20] necessitates large batch sizes to learn discriminative representations, which is computationally infeasible when training the full framework end-to-end due to memory constraints. Second, and more importantly, we freeze the ETE after this pretraining stage. This design choice provides a stable and invariant exposure reference space for the feature modulation in Net D and Net R . We empirically observed that co-optimizing the ETE with a restoration objective can lead to representation drift, where the embedding tends to encode scene content rather than distinct exposure conditions. By freezing the ETE, we structurally prevent this feature entanglement, ensuring the embedding functions as a decoupled sensor prior. This stable anchoring encourages the network to more faithfully model the physics of motion-exposure coupling, thereby enhancing training stability. Consequently, the framework achieves robust outof-distribution generalization, as validated in Table 4 of the main paper. The ETE is thus trained alone using the following contrastive loss:

where q denotes the anchor, P contains positive samples with the same exposure label as the anchor, B is the minibatch, and α is a temperature parameter.

In the second stage, guided by the pretrained ETE, we train Net D to predict physically-plausible degradation priors. To ensure the predicted priors are accurate, we use a composite loss function L D as:

The first term is the reconstruction loss, ensuring the predicted priors can reconstruct the original blurry LR input X. The second term is a warping loss, where Y i±1→i represents the sharp HR neighboring frames warped into the current frame i using the predicted image flow-mask pairs f Y i . This loss ensures the predicted motion priors are accurate. The third term provides additional, direct supervision to the optical flow component, f Y , within these pairs using pseudo-GT flows generated by a pretrained RAFT model [42], which helps Net D produce physically meaningful motion estimations.

In the final stage, we jointly train the entire FMA-Net++ framework with Net D and Net R . The total loss is defined as:

where Ŷ is the final restored HR sequence from Net R . The first term is the primary restoration loss, and the second term finetunes the pretrained Net D during joint training.

We provide the implementation details omitted from Sec. 4 of the main paper.

We train FMA-Net++ using the Adam optimizer [22] with the default setting on 4 NVIDIA A6000 GPUs. In the first training stage, the ETE is trained with a mini-batch size of 128, a learning rate of 0.01, and α = 0.5 in Eq. 15. In the second stage, Net D is trained with a mini-batch size of 8, using an initial learning rate of 2 × 10 -4 that is reduced by half at 70%, 85%, and 95% of the total 280K iterations.

One significant challenge in VSRDB under dynamic exposures is the lack of benchmarks for performance evaluation.

To address this, we construct two new benchmarks, REDS-ME (Multi-Exposure) and REDS-RE (Random-Exposure).

Both REDS-ME and REDS-RE are derived from the REDS dataset [34], as described in the main paper. The data generation process follows the physical degradation formulation in Eq. 8, serving as its discrete, practical approximation. We follow a widely adopted pipeline [33-35, 40, 62]: (1) the original 120 fps REDS videos are first interpolated to 1920 fps using EMA-VFI [56] to obtain sufficient intermediate frames for realistic motion blur simula-tion; (2) to simulate temporal integration, we average consecutive high-framerate frames, and the resulting blurry HR videos are then spatially downsampled using bicubic interpolation. We adopt this blur-then-downsample order as it better reflects real-world image formation and mitigates aliasing through temporal averaging [33,34]. This yields realistic blurry LR videos suitable for robust VSRDB evaluation.

To construct REDS-ME, we synthesize five variants of blurry videos by averaging different numbers of consecutive high-framerate frames, resulting in five exposure levels denoted by ratios from 5 : 1 (shortest exposure with minimal motion blur) to 5 : 5 (longest exposure with severe motion blur). This five-level configuration is motivated by the original REDS dataset’s temporal sampling strategy, where 120 fps source videos are converted to 24 fps sequences, covering a temporal span equivalent to five consecutive source frames. Hence, our exposure ratios 5 : 1-5 : 5 align naturally with this structure while providing a systematic range of motion-blur intensities. These levels also serve as pseudolabels for pretraining our ETE module. Fig. 7 shows example frames from our REDS-ME dataset.

For training, we utilize all five exposure variations from the REDS-ME training set. For evaluation, we adopt the two most challenging exposure levels, 5 : 4 and 5 : 5, from REDS4-ME, which exhibit the most severe motion blur. REDS4-ME is derived from the REDS4 subset1 , a commonly used test set in prior works [26,31,50,54].

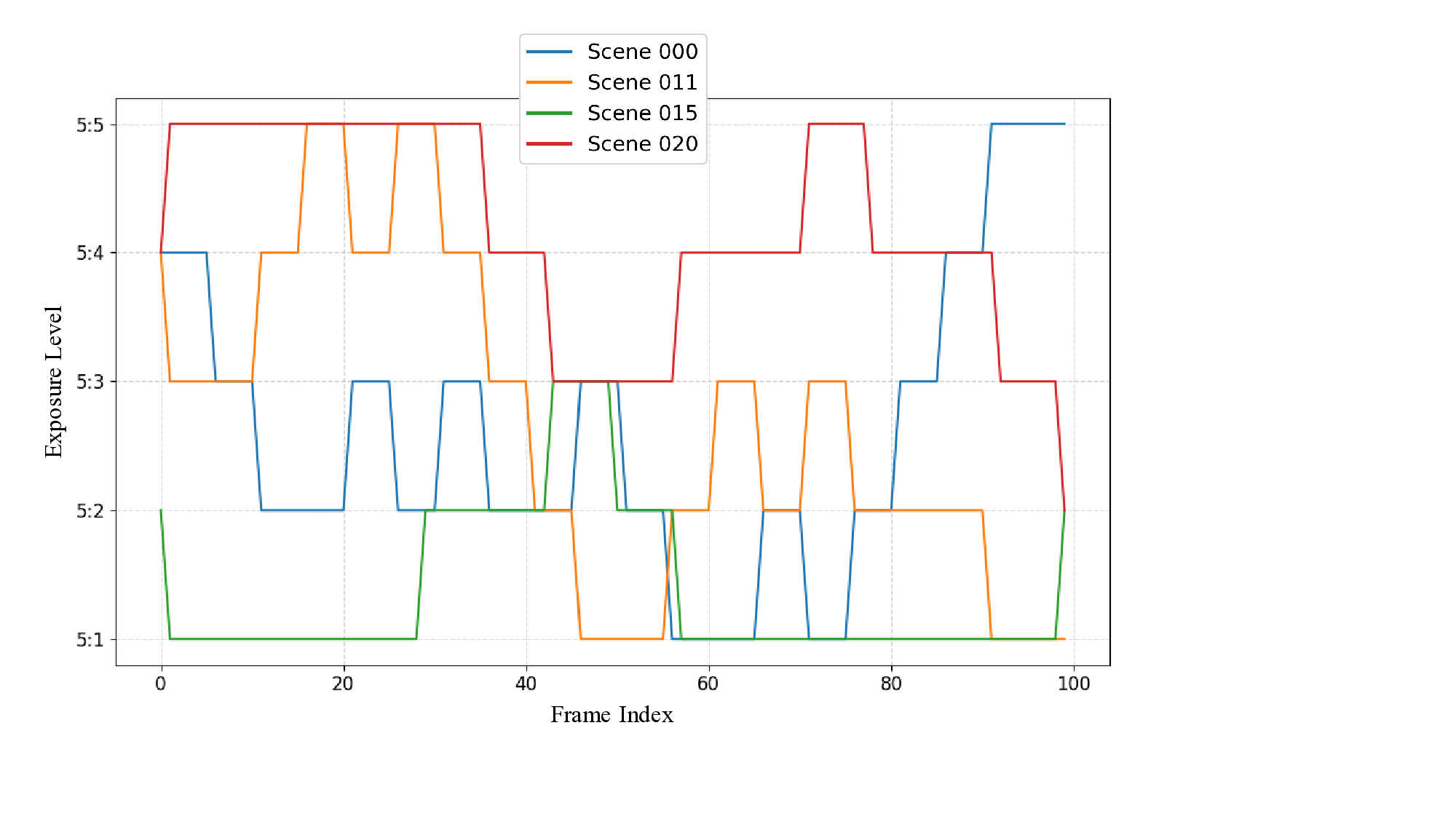

Furthermore, to explicitly evaluate robustness under dynamically varying exposure conditions, we construct the REDS-RE benchmark by temporally mixing frames from all five exposure levels within each REDS4-ME test scene. To simulate the temporal inertia and smoothness of realworld auto-exposure mechanisms, we employ a structured, interval-based random walk strategy rather than simple frame-wise randomization. Specifically, the exposure level is updated only at fixed intervals (every 5 or 7 frames). At each update step, the exposure level is uniformly sampled to increment, decrement, or remain constant, constrained within the range of available levels (5 : 1 to 5 : 5). As visualized in Fig. 12, this process yields diverse, step-wise exposure trajectories that effectively approximate realistic, smooth, yet non-stationary capture scenarios.

Additionally, we assess the generalization ability of our model using the standard GoPro dataset [33], which differs from REDS in motion patterns and exposure characteristics. Following standard VSRDB protocols [54], we apply bicubic downsampling to the blurry GoPro videos to generate the blurry LR inputs.

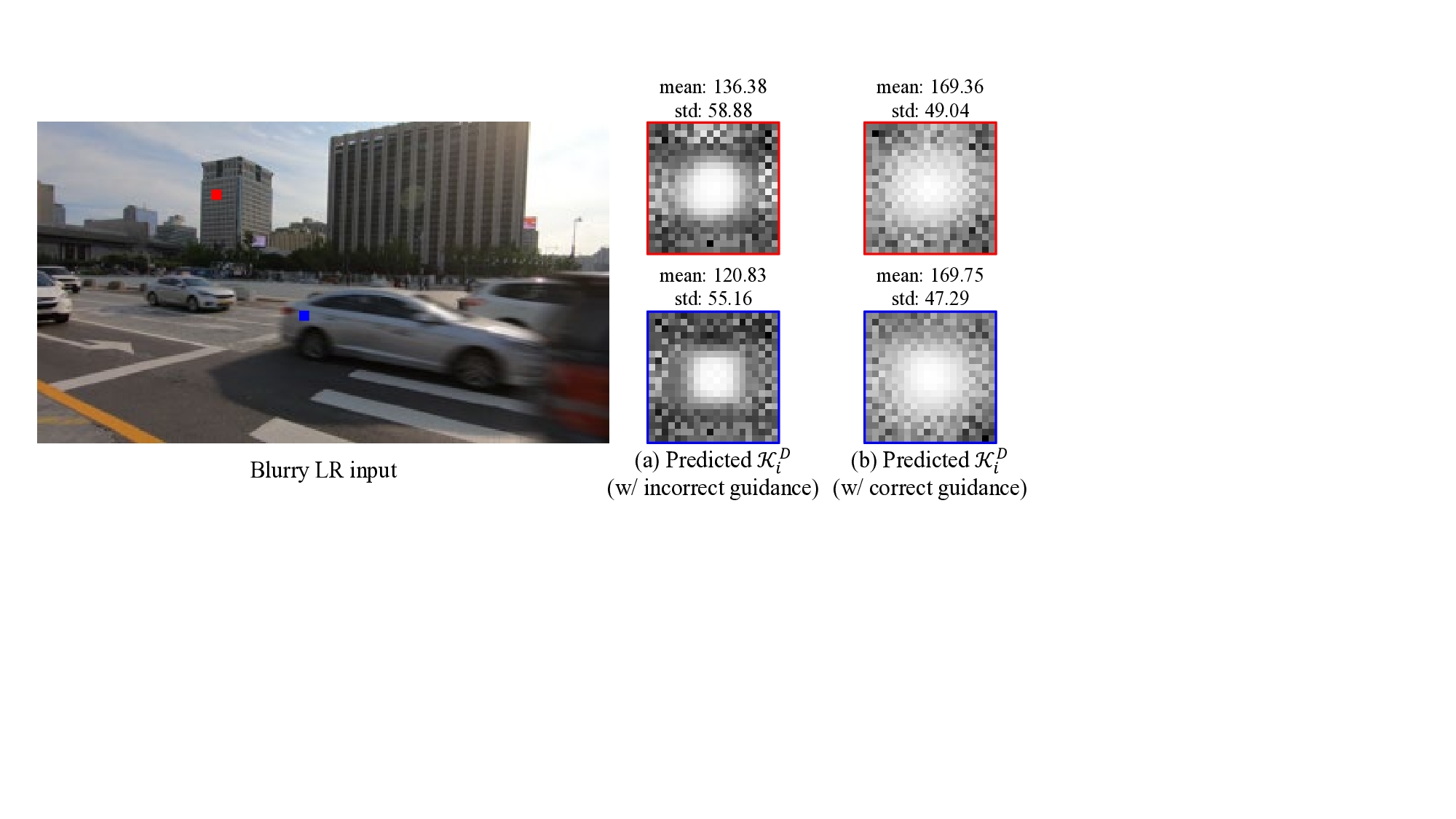

In this section, we provide further ablation studies and detailed visual analyses that were omitted from Sec. 5 of the main paper. We first present detailed quantitative and qualitative analyses of our core contributions, namely exposureaware modeling and architectural design. We then provide ablations for other key components, such as our filtering mechanism and loss functions. The Effect of ETE on Exposure-Aware Kernels. To visually demonstrate the synergy between our exposureaware modeling and other modules, we analyze how the guidance from ETE directly influences the degradation kernels predicted by FGDF. Fig. 9 illustrates this relationship. We take a severely blurred frame from REDS4-ME-5 : 5 and provide our trained Net D with two exposure-aware features u extracted from the same scene but under different exposure conditions: (i) correct guidance from the corresponding 5 : 5 frame, and (ii) incorrect guidance from the 5 : 1 frame of the same scene. When provided with the correct guidance, Net D predicts a spatially diffuse kernel that accurately models the motion blur, whereas incorrect exposure guidance yields a highly concentrated kernel, indicating that the model is misled into assuming a less severe blur. This confirms that FGDF is effectively and sensitively conditioned on the exposure information provided via ETM. Sensitivity to ETE Guidance. We further investigate how this sensitivity to guidance affects the final restoration performance. We evaluate our model on the REDS4-ME-5 : 5 input frames using exposure guidance features extracted from all five exposure levels (5 : 1 to 5 : 5), and present the results in Table 6. The results reveal an insightful characteristic of our framework. As expected, performance gradually degrades as the provided guidance deviates from the correct one, confirming that our model is indeed effectively leveraging the ETE guidance. However, the key observation is that performance does not severely fail even with the most incorrect guidance. This demonstrates a desirable robustness: FMA-Net++ does not blindly depend on the ETE predictions but can instead rely on the strong spatio-temporal context provided by its HRBP backbone to achieve a reasonable restoration, highlighting its robust design.

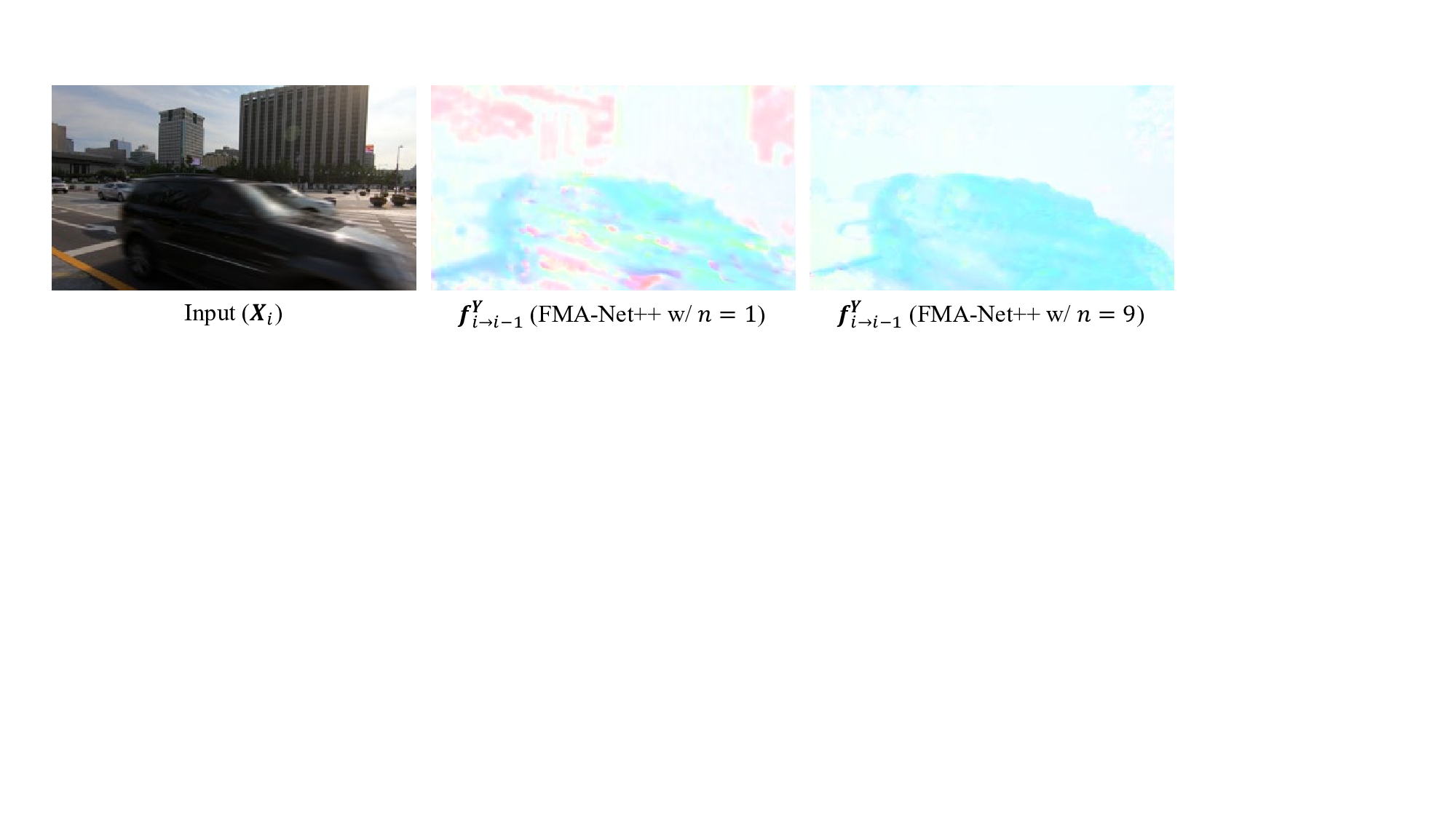

We provide further analyses on our architectural design to validate the choices discussed in the main paper (primarily Sec. 3.3 and Sec. 5.3). This section details the impact of multi-flow hypotheses, visualizes the hierarchical refinement process, and provides a direct qualitative comparison against the FMA-Net framework. Effect of the Number of Multi-Flow-Mask Pairs. We analyze how the number of multi-flow-mask pairs n affects performance and stability in motion estimation. As shown in Table 7, increasing n consistently improves restoration quality with negligible computational overhead. A larger number of pairs enables the model to establish more one-tomany correspondences, effectively leveraging multiple motion hypotheses, which is especially important under severe motion blur where a single flow estimation can be unreliable. Fig. 10 visualizes this effect. With only one pair (n = 1), the predicted optical flow is noisy and spatially distorted, failing to capture accurate motion boundaries. In contrast, using nine pairs (n = 9) produces much cleaner and sharper flow fields that align well with object motion. This confirms that the multi-flow mechanism remains effective for robust motion modeling under challenging degradation conditions. We thus retain this component and set n = 9 in our final configuration. Visualization of Hierarchical Feature Refinement. We visualize the intermediate representations of the refined feature F R,j i across four refinement stages in Fig. 11 to illustrate how the HRBP blocks progressively operate. As shown in the figure, the initial stage exhibits noisy and spatially diffuse activations, while later stages produce increasingly sharper and more structurally aligned features, with high-frequency details (e.g., building edges) becoming more prominent. This progressive sharpening provides strong evidence that our hierarchical refinement strategy iteratively enhances feature quality, leading to sharper and more temporally consistent outputs. Qualitative Comparison with FMA-Net. As shown in Tables 1 and2 of the main paper, our FMA-Net++ outperforms the retrained FMA-Net * (which uses a slidingwindow approach). To complement these quantitative results, we further provide a direct visual comparison between the two models in challenging scenes that contain strong motion blur and low spatial redundancy (e.g., human faces). As shown in Fig. 13, FMA-Net suffers from temporal misalignment and produces distorted facial structures, while our FMA-Net++ reconstructs sharper edges and more temporally consistent details. These results visually confirm that the proposed hierarchical refinement and exposure-aware modeling provide notable improvements over the FMA-Net framework.

FGDF was originally introduced in FMA-Net [54] to perform motion-aware filtering along optical-flow trajectories. In FMA-Net++, we enhance FGDF by conditioning the filtering weights on exposure-aware features (Sec. 3.4). To verify that this extension preserves its motion-aware advantage, we compare the exposure-aware FGDF with the conventional dynamic filtering (CDF) [16] on REDS4-ME-5 : 5. As shown in Table 8, the exposure-aware FGDF maintains a clear and significant performance advantage over CDF across all motion magnitudes. This result confirms that our exposure-aware conditioning effectively strengthens the underlying motion-aware degradation modeling, especially in challenging high-motion, long-exposure scenarios.

We validate the design of our composite loss function L D (Eq. 16), which guides the training of Net D . Specifically, we analyze the impact of the coefficients for the warping loss (λ 1 ) and the RAFT supervision loss (λ 2 ) on the REDS4-ME-5 : 5 test set. As summarized in Table 9, both loss terms are essential for achieving optimal performance. First, adjusting the weight (λ 1 ) of the warping loss term significantly affects the final restoration quality: an overly large weight interferes with the primary reconstruction objective, while a weight that is too small fails to enforce accurate alignment in the sharp HR space. Second, removing the RAFT supervision (λ 2 = 0) causes a notable drop in performance, confirming that pseudo-GT flow supervision is crucial for learning accurate motion priors. Our chosen coefficients (λ 1 = λ 2 = 10 -4 ) provide the best trade-off, yielding the highest performance across all metrics.

We provide additional qualitative comparisons complementing the results shown in the main paper (Fig. 1 11. Limitations

Our proposed benchmarks, REDS-ME and REDS-RE, are constructed by averaging high-framerate frames to simulate motion blur under varying exposure conditions. While this approach follows standard protocols in video deblurring and restoration [33,35,38,40,62], the linear averaging process may not fully capture the complex and nonlinear responses of real-world camera sensors. Moreover, our datasets do not account for other challenging factors such as spatiallyvarying lighting or sensor noise, which can be coupled with exposure changes. Nevertheless, this controlled setup provides a practical and systematic way to analyze exposureinduced degradation under varying conditions. The construction of new benchmarks that more faithfully model these intricate, real-world camera pipelines remains an important challenge for future research.

FMA-Net++ relies on 2D optical flow to model motion between frames. As with most flow-based video restoration approaches [3,5,53,54,58], this inherently limits reliability under large out-of-plane rotations or complex non-rigid motions, where 2D correspondences become ambiguous.

While our hierarchical refinement and exposure-aware design mitigate some of these issues in practice, fully addressing such 3D motion effects would require more advanced motion models (e.g., 3D motion fields or geometry-aware representations), which we leave as an interesting direction for future work.

-

(6.72 / 49.09) FMA-Net++ (5.80 / 56.39) RVRT * (7.31 / 32.69) BasicVSR++ * (7.26 / 36.74) DBVSR * (7.17 / 25.85) Restormer * (6.21 / 29.87) IART * (6.76 / 46.41) BSSTNet * (6.26 / 43.99) Blurry LR input (NIQE↓ / MUSIQ↑) • 10 2

study for the number of multi-flow-mask pairs (n) on REDS4-ME-5 : 5.

Clips 000, 011, 015, and 020 from the REDS training set.

📸 Image Gallery