CARL: Focusing Agentic Reinforcement Learning on Critical Actions

📝 Original Info

- Title: CARL: Focusing Agentic Reinforcement Learning on Critical Actions

- ArXiv ID: 2512.04949

- Date: 2025-12-04

- Authors: Leyang Shen, Yang Zhang, Chun Kai Ling, Xiaoyan Zhao, Tat-Seng Chua

📝 Abstract

Agents capable of accomplishing complex tasks through multiple interactions with the environment have emerged as a popular research direction. However, in such multi-step settings, the conventional group-level policy optimization algorithm becomes suboptimal because of its underlying assumption that each action holds equal contribution, which deviates significantly from reality. Our analysis reveals that only a small fraction of actions are critical in determining the final outcome. Building on this insight, we propose CARL, a critical-action-focused reinforcement learning algorithm tailored for long-horizon agentic reasoning. CARL leverages entropy as a heuristic proxy for action criticality and achieves focused training by assigning rewards to highcriticality actions while excluding low-criticality actions from model updates, avoiding noisy credit assignment and redundant computation. Extensive experiments demonstrate that CARL achieves both stronger performance and higher efficiency across diverse evaluation settings. The source code will be publicly available.📄 Full Content

Reinforcement learning (RL) plays a crucial role in enhancing multi-turn search agents, as it enables them to selfimprove without relying on human supervision. However, most of the existing attempts on search agent RL (Jin et al., 2025;Gao et al., 2025;Song et al., 2025) simply leverage the group-level policy optimization (GRPO) (Shao et al., 2024) algorithm without examining its suitability. GRPO assumes that each part in a trajectory contributes equally to the outcome (Tan et al., 2025) and repeatedly rolls out full trajectories from scratch, suffering from noisy credit assignment and redundant computation. These issues become particularly pronounced in long-horizon agentic tasks (Gao et al., 2025), where trajectories span multiple steps yet only a small fraction of actions are decisive.

Our preliminary study confirms this, showing that actions at different steps play different roles and have varying impacts on the final outcome. Specifically, when resampling individual actions, over half of the actions induce near-zero changes in the final reward, whereas only a small subset could cause sharp reward changes. These findings suggest that actions differ in their criticality.

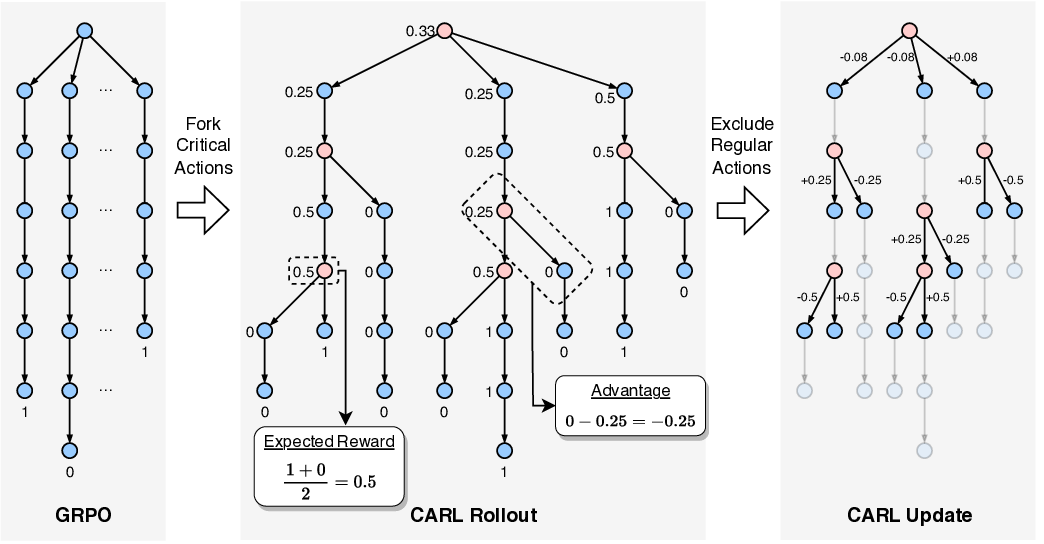

In light of this, we argue that RL for agents should fo-cus on high-criticality actions, and accordingly propose the Critical-Action-Focused Reinforcement Learning (CARL) algorithm that enjoys both high performance and training efficiency. CARL leverages action entropy as a proxy for criticality, concentrating rollouts and optimization efforts on high-criticality actions rather than distributing resources uniformly. As illustrated in Fig. 1, CARL initiates rollouts only from states preceding high-criticality actions and assigns action-level rewards based on expected reward gains, while excluding low-criticality actions from gradient updates. This targeted focus effectively mitigates noisy credit assignment and redundant computation inherent in GRPO.

We follow the setting of ASearcher (Gao et al., 2025) and evaluate CARL on knowledge-intensive question-answering (QA) tasks. As shown in Fig. 1, CARL achieves superior accuracy while requiring policy updates on 72% fewer actions than GRPO. These results demonstrate that CARL is an effective RL algorithm for agentic reasoning that delivers both performance and training efficiency advantages.

Our main contributions are summarized as follows:

• We provide the first comprehensive analysis of the multiturn search agent pipelines, revealing that only a small subset of actions has high impact on the final outcome, which motivates focusing optimization on critical actions.

• We design CARL, a reinforcement learning framework tailored to agentic reasoning. This framework performs focused training on actions with high criticality, yielding both high performance and efficiency.

• We conduct comprehensive experiments on multi-turn search agents across different model sizes and both reasoning and non-reasoning models, demonstrating consistent improvements on multiple knowledge QA benchmarks.

In this section, we discuss recent research advances in two related fields: search agents and improving RL for LLM through credit assignment.

With the rapid advancement of LLMs’ core capabilities (Yang et al., 2025a;Guo et al., 2025), search agents (Yao et al., 2022) have emerged by equipping LLMs with internet access and custom workflows. These agents can proactively search and browse the web to gather information before responding. As task complexity increases, static prompt engineering (Li et al., 2025;Xinjie et al., 2025) and dataset construction method (Yu et al., 2024) quickly reach their limits in improving performance. In contrast, reinforcement learning offers greater potential by enabling agents to self-improve through interaction with the environment.

Inspired by the success of GRPO (Shao et al., 2024) on math reasoning (Hendrycks et al., 2021;He et al., 2024), recent studies have attempted to extend it to search agents (Song et al., 2025;Jin et al., 2025;Zheng et al., 2025;Gao et al., 2025), with a primary focus on data synthesis and framework construction. ARPO (Dong et al., 2025) takes an initial step toward RL algorithmic refinement by shifting the rollout granularity from trajectory to step level, based on the observation that token entropy often rises after tool calls. However, these methods still treat all steps uniformly without examining their individual contributions, leading to noisy credit assignment and redundant computation. In this work, we discover that agent outcomes are determined by a small subset of high-criticality actions, and accordingly structure RL to focus on these actions.

Many recent works (Wang et al., 2023;Luo et al., 2024;Setlur et al., 2025;Wang et al., 2025) enhance RL for LLM through finer-grained credit assignment, as step-wise rewards can accelerate convergence and improve learning outcomes (Lightman et al., 2023). Among these, rewardmodel-free methods (Kazemnejad et al., 2024;Fei et al., 2025) stand out for their stability and efficiency.

A natural structure for providing fine-grained, step-level rewards is a tree1 , enabling controlled comparisons among intermediate steps (Tran et al., 2025). Prior studies have explored this structure on math reasoning tasks. For example, TreeRPO (Yang et al., 2025b) samples a full n-ary tree and groups sibling nodes for GRPO updates. TreeRL (Hou et al., 2025) further removes the group constraint and directly estimates each step’s advantage by evaluating its impact on expected rewards. In agentic RL (Gao et al., 2025), reward sparsity becomes more critical due to long-horizon multistep execution, as demonstrated by ReasonRAG (Zhang et al., 2025), rendering step-level reward modeling increasingly necessary. In this work, we address this and propose assigning rewards exclusively to high-criticality actions that truly determine the outcome.

Multi-turn search agents (Gao et al., 2025) are equipped with a search engine and a web browser. They are designed to answer knowledge-intensive questions through interacting with these tools several times for information gathering.

We formulate this execution process as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), defined by the tuple ⟨S, A, P, R⟩, where S The agent is represented by a policy π θ (a | s), which is defined by a probability distribution over actions given a state. For each question, the agent will continuously generate a t for s t until reaching a termination state s T with an “answer” or reaching the maximum step limit T max . The whole execution process can be recorded as a trajectory τ = {(s t , a t )} T t=1 . The objective of RL is to maximize the outcome reward, which can be expressed as

(1) GRPO (Shao et al., 2024) follows the widely-adopted online RL algorithm, PPO (Schulman et al., 2017), to setup loss function J (θ):

where A i is the advantage of token i, which indicates the direction and scale the model should update on it. The ratio r i (θ) measures the policy shift between the updated policy π θ and the old policy π θold , and is clipped by ϵ for stability.

GRPO measures the advantage of each trajectory τ by comparing it with the group average:

where mean(R(τ )) and std(R(τ )) are computed over all trajectories of the same question. This trajectory-level advantage is then assigned to all tokens within the trajectory under the assumption that every token contributes equally.

GRPO’s assumption of equal token contribution becomes problematic in agentic reasoning, where trajectories consist of clearly separated steps that play different roles and with varying criticality. We analyze the reasoning pipeline through a preliminary experiment to characterize this variation in action criticality, informing our algorithm design.

Case Study. In Table 1, we present an example of how a multi-turn search agent solves a problem. The agent’s actions can be categorized into search, access, read, and answer. In the search action, the agent generates search keywords and gets results from a search engine. In the access action, it accesses a specific website by URL. After each of them, the agent performs read actions to extract and summarize useful information from the often lengthy search results or webpage content. Once sufficient evidence is collected, the agent executes the answer action, terminating the pipeline with a final response. Intuitively, these actions play different roles and contribute differently to the outcome.

Action Criticality Distribution. To validate this intuition, we conduct an experiment to observe the distribution of action criticalities. We define the criticality of an action2 , denoted C π θ (a t ), as the degree to which its decision influences the final outcome. Formally, we quantify criticality as the standard deviation in outcome reward when stochasticity is isolated to that single action:

where s t denotes the state preceding action a t , and τ st,a ′ denotes the trajectory taking action a ′ at state s t followed by greedy decoding thereafter (i.e., temperature=0).

We test the search agent on 70 tasks randomly sampled from 7 knowledge-intensive question-answering datasets, resulting in 294 actions, and estimate C π θ (a t ) for each action. As shown in Fig. 2(a), we can observe substantial disparity in action criticality. Most actions exhibit extremely low variance in reward: over 50% of actions have almost no impact on the outcome when resampled, indicating that the majority of actions are of low criticality. In contrast, around 10% of actions exhibit a reward standard deviation greater than 0.4, representing a minority of high-criticality actions.

This suggests that uniform treatment of all actions, as done by GRPO, is suboptimal. Instead, we should take the criticality of actions into account: assigning rewards more precisely to high-criticality actions and concentrating computational resources on them.

Inspired by the study, we propose the Critical-Actionfocused RL (CARL) algorithm. As illustrated in Fig. 3, CARL prioritizes high-criticality action exploration with entropy-guided progressive rollout, and provides actionlevel update signals using action-level advantage formulation. Then, it performs selective updates on high-criticality actions, excluding low-criticality ones.

Critical Actions Identification. Before we can focus on critical actions, we need a practical method to identify them, as the sampling-based estimation in Eq. 5 incurs a high computational cost. To achieve this, we analyze the characteristics of high-criticality actions to find an intrinsic metric.

High-criticality actions are intuitively non-trivial decision points where multiple candidates appear plausible, making it difficult to identify the optimal choice. This difficulty can be reflected in the model’s action distribution: when the model cannot confidently make decisions, it assigns similar probabilities to multiple candidates, resulting in a more uniform distribution. We adopt entropy to measure this quantitatively, termed action entropy, which captures the degree to which probability mass is dispersed across possible actions. A higher action entropy at state s t indicates greater uncertainty in selecting among competing actions a t , suggesting that actions taken from s t are of higher criticality.

Unlike token-level entropy, which can be calculated precisely by enumerating over a finite vocabulary, action entropy involves an infinite space of possible actions and thus requires estimation. We estimate the action entropy at state s t via Monte Carlo sampling (Robert & Casella, 2004):

where Y i denotes an action sampled by policy π θ at state s t , and N denotes the total sampling number. Each sampled action Y i is a sequence of tokens, Y i = [y 1 , . . . , y |Y | ], with |Y | denoting the length. We follow Wu et al. (2016) and adopt a length-normalized sequence log-probability:

This entropy-based criticality measure aligns with intuition: we typically feel uncertain when facing decisions that significantly affect outcomes, hesitating among multiple plausible options rather than acting reflexively. Our empirical results confirm this: as shown in Fig. 2(b), states preceding highcriticality actions exhibit clearly higher action entropy than states preceding low-criticality actions. This finding validates action entropy as an effective proxy for criticality, eliminating the need for costly outcome-based sampling.

Action-Level Advantage Formulation. To provide precise update signals for the identified high-criticality actions, CARL assigns rewards to them with an action-level advantage formulation. We move beyond the group-based RL paradigm of GRPO and reformulate the credit assignment question from “How good is this trajectory compared to group average?” to “How much reward improvement does this action provide?”. Specifically, we organize sampled trajectories into a tree structure, where nodes represent states and directed edges represent actions, as shown in Fig. 3. We first compute the expected reward of each state via a recursive Bellman-style estimator over this tree and then calculate the advantage of each action through tree differencing, which measures the expected reward gain contributed by taking that action. Formally, the expected reward E[R(u)] of a state u is defined as the expected outcome reward obtained by following the policy π θ starting from the state u:

This can be recursively computed by averaging its child nodes In the rollout phase, CARL progressively forks the state with the lowest action density. Then, it assigns action-level credits to critical actions through an expected-reward-gain formulation: the expected reward of each state is estimated by averaging its successor states, and the advantage of an action is computed as the difference between the terminal and initial state. In the model update phase, low-criticality actions are excluded (grayed out) to reduce redundant computation.

For each action, represented by edge e = (u, v) connecting parent node u and child node v, the advantage is defined as

Intuitively, A(e) measures how much taking action e improves the expected outcome compared to state u. This action-level advantage formulation provides an unbiased estimation of action-level reward regardless of tree structure. This unbiasedness does not require a full n-ary tree, requiring only that child nodes are sampled independently from π θ (• | u). This property distinguishes CARL from prior tree-based methods such as ARPO (Dong et al., 2025) and TreeRL (Hou et al., 2025), as analyzed in Appendix A.1.

Entropy-Guided Progressive Rollout. We leverage the flexibility brought by unbiasedness to dynamically allocate rollout budget in proportion to each state’s action entropy ( Eq. ( 6)), thereby maximizing the criticality of collected actions. Specifically, we define the action density to measure the extent to which each state has been explored relative to its entropy:

where n(s t ) denotes the number of children already sampled from s t . At each expansion step, CARL greedily selects the node with the lowest action density to start with, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

In practice, we set an initial sample size N 0 , a hyperparameter, to control how many trajectories should be generated from scratch before the forking algorithm. This design improves stability by ensuring a basic set of candidates to start with. We present the progressive rollout algorithm in Appendix C.1.

Selective Update on High-Criticality Actions. As a result of entropy-guided rollout, the collected tree-structured trajectory D roll comprises high-criticality actions with siblings and low-criticality actions without siblings. Each training sample is a tuple of state s t , action a t , and advantage A t . As low-criticality actions have little impact on the final results, we exclude their data from model update to further improve efficiency and avoid incorrect learning. The resulting updating sample set D upd is

(13) For each action, we follow the setting of GRPO to assign the action-level reward to all tokens within the action. The model is then updated on D upd using the PPO loss (Eq. 2).

Efficiency Analysis. CARL improves efficiency by reducing computing resource consumption for both phases of RL: trajectory collection and model update. For trajectory collection, we reuse the prefix of existing sequences without repeatedly rolling out from scratch. Under the condition that the number of leaf nodes N remains unchanged, the total number of actions required is significantly reduced. Assume each trajectory contains T actions and the probability of an action being critical is uniformly distributed. The expected resource consumption as a proportion of the baseline equals

When N 0 and N are set to 1 and 16 respectively in our default setting, CARL saves 44% of resources. When we increase N 0 to 8 in our best performance setting, CARL keeps the same rollout resource consumption as GRPO.

For model update, the sample size is further reduced by excluding low-criticality actions. Since forking an action without siblings introduces two critical actions, while forking from an action with siblings introduces only one, the number of actions used for training is bounded by

In contrast, GRPO uses T N action samples per question, where statistics show E[T ] = 5. Therefore, CARL uses 60% fewer actions for model update, substantially improving training efficiency.

- Experiments

We follow the experimental settings of ASearcher (Gao et al., 2025), using a local retrieval server as search environment, which leverages the 2018 Wikipedia dump (Karpukhin et al., 2020) as information source and E5 (Wang et al., 2022) as the retriever. We evaluate on seven knowledge QA benchmarks, spanning single-hop (Natural Questions (Kwiatkowski et al., 2019), TriviaQA (Joshi et al., 2017), and PopQA (Mallen et al., 2022)) and multi-hop reasoning (HotpotQA (Yang et al., 2018), 2WikiMulti-HopQA (Ho et al., 2020), MuSiQue (Trivedi et al., 2022), and Bamboogle (Press et al., 2023)), reporting F1 and LLMas-Judge (LasJ) metrics consistent with Gao et al. (2025).

We provide implementation details in Appendix C.

In-Domain Evaluation. We first evaluate CARL under the same configuration as training on in-domain knowledge question-answering datasets, using a local retrieval server. For non-reasoning models, the 3B variant yields modest improvements due to the model’s limited capability -trajectories tend to be short, and action-level rewards consequently provide less benefit. In contrast, CARL achieves more pronounced gains on the 7B variant, improving both F1 and LasJ by over 2 points. With the 7B backbone’s stronger foundational capabilities, CARL’s precise credit assignment enables the model to sustain longer agentic pipelines, increasing the average number of actions per task by 75%.

Although rollout cost increases accordingly, the substantial reduction in update actions keeps the overall cost comparable, reflecting more rational resource allocation.

Considering the trade-off between performance and training cost, we conduct analytical experiments on the 4B reasoning model with a maximum of 10 actions. When the initial sample size is set to N 0 = 1, CARL-Lite achieves higher performance while using less than half the rollout cost and under 40% of the update samples. Increasing the initial sample size to N 0 = 8 further enhances stability and diversity, enabling CARL to surpass GRPO by 1.4 points on average while still maintaining superior efficiency. Extending the maximum actions to 32 further amplifies CARL’s advantage, with performance gains increasing to 2.2 points over GRPO.

These results demonstrate that CARL is a highly efficient RL algorithm for multi-turn search agents, achieving stronger performance through precise credit assignment while reducing training cost by eliminating redundant computation. Notably, the benefits amplify as models’ foundational capability gets stronger and trajectories get longer, suggesting increasing practical value on more complex tasks.

Baseline Comparison. To validate the effectiveness of CARL, we reproduce three related methods that improve GRPO from the rollout strategy perspective: TreeRPO (Yang et al., 2025b), TreeRL (Hou et al., 2025), and ARPO (Dong et al., 2025). Since these methods are originally designed for token-level tasks with different training configurations, we adapt them to multi-turn search tasks using the 4B reasoning backbone, ensuring an identical number of terminal states per group for fair comparison. Implementation details are provided in Appendix C.5. As shown in Table 2, all three baselines achieve efficiency gains over GRPO through tree-structured partial sampling. However, by focusing on critical actions, CARL-Lite achieves comparable performance with lower computational cost. When computing resource consumption is comparable, CARL exhibits superior performance.

Out of Domain Evaluations. We further evaluate the impact of CARL on the model’s out-of-distribution capability. We replace the local database with online search and website access tools and test agents on three more challenging benchmarks. Following ASearcher (Gao et al., 2025), we evaluate each model with 4 random seeds and report both mean and best-of-four results. As shown in Table 3, CARL achieves significant higher performance on GAIA (Mialon et al., 2023) and Frames (Krishna et al., 2025), and achieves comparable performance on xBench-DeepSearch (Chen et al., 2025). This demonstrates the advantage of CARL’s critical-action-focused learning strategy in enhancing decision-making and mitigating overfitting, leading to stronger generalization.

Here we provide a breakdown analysis of CARL by ablating its key components: action-level advantage formulation, entropy-guided progressive rollout, and selective update on high-criticality actions. Results are shown in Table 4.

Action-Level Advantage Formulation. To isolate the effect of action-level advantage formulation, we design a variant (Exp. #1) that replaces action-level rewards with outcome rewards. This variant collects trajectories in the same manner as CARL. Differently, each root-to-leaf chain is treated as an independent trajectory, and the outcome reward is uniformly assigned to all critical actions within that trajectory. For those actions that appear in multiple root-toleaf chains, we include every corresponding instance in the update set, each paired with its respective outcome reward.

Compared with CARL (Exp. #4), this variant yields weaker performance due to the noisy credit assignment, demonstrating the advantage of action-level advantage formulation.

Entropy-Guided Progressive Rollout. To verify the necessity of entropy-guided progressive rollout, we design a variant (Exp. #2) by replacing CARL’s heuristic forking algorithm with random selection. Compared with entropyguided (Exp. #4), random selection leads to a performance drop of 2.2 points in F1 and 2.4 points in LasJ. This demonstrates that entropy-guided progressive rollout plays a crucial role in CARL, as it directs exploration toward critical actions rather than treating all equally.

Selective Update on High-Criticality Actions. To assess the impact of excluding low-criticality actions during model update, we design a variant that retains all actions. Since the parent of each low-criticality action has only one child, the advantage will be zero according to our formulation.

To avoid an uninformative zero advantage, we inherit the advantage value from the parent’s incoming edge:

where e parent denotes the incoming edge to node u. This means they contribute together to the expected reward gain.

Comparing the variant that keeps all actions (Exp. #3) against CARL (Exp. #4), we observe that CARL provides a clear performance gain of around 1 point for both metrics under the comparable computational cost. This indicates that CARL achieves better allocation of computational resources through focusing on critical actions.

In this section, we provide further analysis to investigate two research questions: RQ1: How does CARL achieve significant improvement on OOD benchmarks? RQ2: What are the characteristics of high-criticality actions?

Diversity Impact (RQ1). Recent works (Cheng et al., 2025;Cui et al., 2025;Yue et al., 2025) show that standard RL training will reduce model diversity and drive the policy to overly deterministic behavior. Diversity is important for agentic reasoning, as it enables the model to continuously reason and explore with the environment rather than jumping to conclusions prematurely.

Unlike GRPO, CARL selectively updates only critical actions instead of uniformly optimizing the entire trajectory. This conservative update scheme preserves model diversity.

As shown in Fig. 4(a), the policy entropy of CARL remains consistently higher than that of GRPO and continues to increase throughout training. In contrast, GRPO rapidly collapses to a lower-entropy regime and exhibits limited recovery, suggesting reduced exploration capacity as training proceeds. We also examine the entropy on unseen test datasets. As shown in Fig. 4(b), the entropy distribution of CARL is overall higher than that of GRPO, indicating that CARL maintains a higher-entropy policy and thereby has richer action diversity and stronger exploration potential. This explains CARL’s advantage on OOD benchmarks.

Further Action Criticality Analysis (RQ2). As shown in Fig. 5, we analyze action criticality across different action types and positions. Fig. 5(a) shows that search and access actions exhibit higher criticality than read and answer actions. This aligns with the intuition that selecting search keywords and URLs is more critical than summarizing information or generating answers. Also, in Fig. 5 (b), we can observe that the first few actions of the agent generally have a greater impact on the outcome than subsequent ones. However, the outcome is neither equally determined by all actions nor entirely determined by a single one, which verifies the necessity of dynamic critical action identification.

This paper analyzes the execution pipeline of multi-turn search agents and proposes CARL according to the discrepancy in action criticality. By focusing RL on critical actions, CARL effectively addresses two key limitations of GRPO: noisy credit assignment and redundant computation. As large reasoning models and long-horizon agentic reasoning tasks continue to gain prominence, the design philosophy of CARL, focusing on critical actions, offers a principled and efficient solution for RL in such settings. In future work, we plan to extend CARL to more challenging tasks involving ultra-long-horizon agentic reasoning and multi-agent systems, where the benefits of critical-action-focused learning are expected to be even more pronounced. The inequality holds whenever n 1 and n 2 are not identically distributed, which is clearly not guaranteed. Since the two biases arise from independent sources-batch composition and subtree sampling structure-they obviously cannot cancel, resulting in biased advantage estimates.

The unbiasedness of CARL’s estimator provides important practical benefits: it allows flexible adjustment of the sampling tree structure without introducing systematic errors in advantage estimation, which makes the uncertainty-guided progressive rollout algorithm possible. This decouples the exploration strategy from estimation correctness, enabling more efficient use of computational resources.

We measure the inference efficiency and summarize the results in Table 5. Across all settings, CARL-trained models achieve comparable or lower per-action token usage compared to GRPO, indicating that CARL does not introduce unnecessary verbosity. For larger backbones such as the 7B non-reasoning variant, CARL further demonstrates its ability to support extended multi-step execution, enabling significantly longer action sequences and yielding performance gains exceeding 2 points. These advantages stem from action-level reward modeling and critical-action-focused model update.

All of our experiments are conducted on 8×A100 GPUs. We provide a comparison of computational resource usage in Table 6. CARL-Lite achieves the lowest GPU hours (253.17) by significantly reducing both rollout and update costs, while still outperforming GRPO on both metrics. CARL, with a larger initial sample size, increases rollout cost to a level comparable to GRPO, delivering larger performance improvements while still requiring fewer computational resources. These results confirm CARL’s efficiency advantages.

We present an example of how CARL succeeds in accomplishing difficult tasks in Table 7. In this case, the GRPO-trained agent commits to an answer immediately after encountering a limited piece of evidence -“Crowell and Cash married in 1979”. In contrast, the CARL-trained agent exhibits a more cautious and plan-driven strategy, performing additional searches to explicitly verify the spouse information from multiple sources. Through this process, it found more comprehensive evidence -“Cash married her second husband, John Leventhal, in 1995” -and answers correctly. In this case, the third action is the most critical, as the decision of the model at this point determines whether it can obtain sufficient information for a correct answer.

Baseline Capability Requirement. CARL is built on the assumption that model uncertainty correlates with action criticality. If the model confidently makes an incorrect decision, CARL will be less effective than GRPO, as it will not explore alternative choices for that action. In other words, CARL yields a higher performance ceiling only when the model possesses sufficient baseline capability. Under this condition, uncertainty serves as a reliable signal for identifying critical actions, allowing CARL to selectively refine them and achieve stronger overall performance. This is empirically supported by our results in Table 2: CARL demonstrates larger improvements over GRPO on stronger base models (e.g., 7B vs. 3B non-reasoning models), where the model has greater foundational capacity to express more meaningful possibilities at key decision points.

Therefore, for more challenging tasks where agents exhibit low zero-shot performance, a cold-start phase via supervised finetuning (SFT) is necessary to establish basic competence before CARL can be applied for further unsupervised improvement.

Experiments. Due to limited computational resources, we have not yet extended CARL to larger reasoning models such as QwQ-32B, or evaluated it on more complex agentic benchmarks (Wei et al., 2025;Drouin et al., 2024) and multi-agent frameworks (Ye et al., 2025). We will validate our approach on them in future work.

C.1. Uncertainty-Guided Progressive Rollout Algorithm

Here we provide the implementation details of the uncertainty-guided progressive rollout algorithm. As described in Algorithm 1, the rollout process consists of two phases. In the first phase, we generate N 0 trajectories from scratch to establish a basic set of candidate nodes. Notably, actions in this phase are not included in training. In the second phase, we iteratively select the state with the lowest action density to fork from.

Algorithm 1 Uncertainty-Guided Progressive Forking Select ( ĥ, ŝ, n) with biggest ĥ/n from S // pick the state with the lowest action density 13: τ ← ROLLOUTFROM(ŝ; π θ )

roll |, |D upd |), where the latter captures the number of actions performed during rollout and the number of actions used for policy updates, respectively. Overall, CARL consistently outperforms GRPO across all settings with a significantly reduced number of update actions.

-of-Distribution Evaluation. We use a 4B reasoning model with a 32-action budget, reporting mean (Avg@4) and bestof-four (Pass@4) accuracy across 4 random seeds.

Figure 4. Comparison of Entropy between CARL and GRPO. CARL maintains consistently higher entropy than GRPO during training and evaluation, indicating stronger exploration capability.

Unlike Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS)(Browne et al.,

2012), which focuses on iteratively searching for complete successful paths, tree-based RL methods instead leverage tree structures for rollouts to estimate step-level relative advantages, without emphasis on successful paths.

Throughout this paper, an action refers to a specific action taken at a specific state.

📸 Image Gallery