The Loss Landscape of Powder X-Ray Diffraction-Based Structure Optimization Is Too Rough for Gradient Descent

📝 Original Info

- Title: The Loss Landscape of Powder X-Ray Diffraction-Based Structure Optimization Is Too Rough for Gradient Descent

- ArXiv ID: 2512.04036

- Date: 2025-12-03

- Authors: Nofit Segal, Akshay Subramanian, Mingda Li, Benjamin Kurt Miller, Rafael Gomez-Bombarelli

📝 Abstract

Solving crystal structures from powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) is a central challenge in materials characterization. In this work, we study the powder XRDto-structure mapping using gradient descent optimization, with the goal of recovering the correct structure from moderately distorted initial states based solely on XRD similarity. We show that commonly used XRD similarity metrics result in a highly non-convex landscape, complicating direct optimization. Constraining the optimization to the ground-truth crystal family significantly improves recovery, yielding higher match rates and increased mutual information and correlation scores between structural similarity and XRD similarity. Nevertheless, the landscape may remain non-convex along certain symmetry axes. These findings suggest that symmetry-aware inductive biases could play a meaningful role in helping learning models navigate the inverse mapping from diffraction to structure.📄 Full Content

Experimental phenomena such as preferred orientation, peak overlap, crystal twinning, and instrumental noise further complicate structural determination from powder XRD patterns [9][10][11]. Moreover, many minerals and metallic alloys exhibit solid solution ranges with very slight lattice shifts, which result in ranges of stoichiometries with nearly the same diffraction pattern [4,Chapter 10.3.2][ [12][13][14], making XRD-to-structure mapping a one-to-many problem. Consequently, accurate structure reconstruction typically requires refinement model fitting and domain-specific prior knowledge.

From a computational perspective, structural ambiguity remains even under idealized conditions. Two structures with different compositions can exhibit highly correlated XRD patterns if they share similar symmetry [15][16][17]. Moreover, even when stoichiometry is fixed, structures with close though distinct space groups can yield highly similar XRD patterns [2]. Notably, small distortions in lattice parameters or atomic coordinates can cause discontinuous changes in the diffraction pattern, such as the appearance or disappearance of peaks due to shifting Bragg conditions [4,Chapter 9]. This introduces a highly non-smooth relationship between structure and XRD signal.

Recently, there has been a surge of interest in crystal structure determination from XRD patterns using generative modeling [18][19][20][21][22][23]. A growing body of work applies gradient-based optimization approaches that leverage differentiable physics to refine generated or otherwise-obtained crystal structures by minimizing the difference between simulated and target XRD patterns. For example, Riesel et al. [19] generate crystals conditioned on a given XRD pattern and post-process them using a differentiable XRD simulator to update lattice parameters via gradient descent (GD). Parackal et al. [24] systematically enumerate candidate crystals given composition and space group inputs, and restricts the GD optimization to atomic positions along Wyckoff degrees of freedom. Lee et al. [25] create candidate crystals using an evolutionary algorithm, followed by crystals morphing by maximizing the cosine similarity between the XRD patterns. Outside the powder diffraction setting, GD has further been applied to determine lattice parameters from single-crystal diffraction patterns [26].

As gradient-based refinement relies on comparing simulated and target diffraction patterns, recent work has also focused on developing more robust XRD-similarity metrics. Otero-de-la Roza [27] introduced a cross-correlation-based metric that captures equivalence between diffraction patterns while remaining invariant to lattice distortions. Building on this work, Racioppi et al. [28] applied the metric to crystal structure prediction from XRD data, jointly optimizing the structure by minimizing both this similarity metric and the structure’s enthalpy. Hernández-Rivera et al. [29] systematically analyzed the sensitivity of different families of similarity metrics under isotropic lattice strain. Li et al. [30] proposed an entropy-based similarity measure for spectra and demonstrated its utility for molecular database retrieval from mass spectrometry data.

In this work, we explore the powder XRD-to-structure mapping through the lens of GD optimization. The goal is to recover correct structures based solely on XRD similarity from moderately deviated states. We ask whether the XRD landscape is locally smooth enough for GD to guide us back to the correct configuration. Inspired by experimentally observed symmetry-breaking effects such as thermal expansion from lattice vibrations and thermal fluctuations, we introduce two types of distortions: random lattice distortions and uncorrelated atomic displacements [8,[31][32][33]. These distortions resemble crystal structures predicted by generative models, which often produce nearly correct geometries but with imperfect symmetry [34][35][36]. Through this study, we examine the challenge of “the last mile” in structure elucidation from XRD.

We find that mapping XRD patterns to crystal structures is challenging because high diffraction agreement, as currently measured in literature, does not ensure structural accuracy. We show that commonly used XRD similarity measures, such as cosine similarity, mean squared error (MSE), and entropy similarity, are sensitive to both lattice and coordinate noise distortions, and optimization between distorted structures and ground-truth XRD diffraction can become trapped in local minima. We explore an alternative strategy that enforces lattice constraints, highlighting the role of symmetry in connecting XRD to the crystal structure.

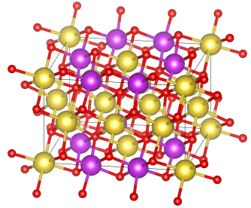

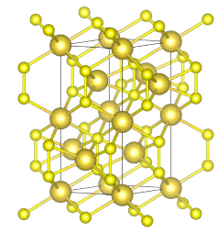

We selected 10 structures from the MP20 dataset [37], a collection of small, inorganic, thermodynamically (meta)stable structures from the Materials Project [38]. We selected the structures according to the most common space groups (see Figure S1), which span a range of crystal symmetries: P 6/mmm, P n 3m, I 4, Cm, I 4 /mmm, F m 3m, C2/m, P 6 3 /mmc, P m 3m, P m.

For each structure, we generated 50 distorted versions using two noise models:

Random lattice distortions were applied via strain tensors [11]. These modifications alter the cell while keeping fractional atomic coordinates fixed. Each distorted structure was generated by randomly sampling the entries of a strain tensor and applying it to the ground-truth lattice matrix. Let L ∈ R 3×3 be the ground-truth lattice matrix (columns are the lattice vectors). We noise the lattice by a random deformation matrix with no change to the atomic fractional coordinates. For a noise level σ l > 0, the entries of S are sampled as

Thus, diagonal entries produce uniaxial expansion/compression, whereas off-diagonal entries induce shear. By construction, these distortions do not preserve crystal symmetry and can introduce diverse deformation modes. If f denotes a fractional coordinate, then the Cartesian position changes from x = Lf to x = Lf with f unchanged.

Independent, uncorrelated positional perturbations were applied to each atom by adding Gaussian-distributed noise to its fractional coordinates. Let x (n)

i ∈ [0, 1) 3 be the fractional coordinates of atom n. For a noise scale σ c > 0, we draw i.i.d. perturbations

and set the noisy fractional coordinates to

where ⌊u⌋ applies the floor function componentwise. Equivalently, x

i + ε n (mod 1) (elementwise), i.e., on the 3-torus T 3 = R 3 /Z 3 .

After applying noise, we attempted to recover the ground-truth structure via gradient-based optimization using StructSnap, a differentiable XRD simulator [19]. We compute diffraction patterns from the structure factor contributions of each atomic site, following Bragg’s law and the kinematic scattering model. The resulting pattern is a 2D tensor of 2θ angles and intensities.

We refine either the lattice parameters or atomic coordinates in accordance with the noise applied. The structure is passed through a differentiable diffraction pipeline to produce a simulated pattern, which is then compared to the ground-truth pattern using a chosen loss function. Given distorted-state XRD x and ground-truth XRD x (see S1.2), we minimize the negative cosine similarity, MSE loss, or negative entropy similarity [30], which are defined respectively:

where S denotes the Shannon entropy. Gradients of the loss are backpropagated to update structural parameters using PyTorch’s autograd.

We examine the effect of symmetry-based constraints in the lattice-noise case by enforcing the ground-truth crystal family during optimization. At inference time, the ground truth information will not be available. However, previous works have shown strong performance in predicting the crystal family [39][40][41][42][43], as well as lattice parameters [44][45][46] and space groups [43,47,48] from XRD patterns.

Using projected optimization, each gradient step is followed by projection onto the constrained values.

Let θ = (a, b, c, α, β, γ) be the lattice parameters. Simple constrained gradient descent on a proposed crystal X using user-selected loss L ∈ {L cos , L MSE , L entropy } and symmetry projection operator P would be:

with the iterations repeating until some convergence criterion is satisfied. Note that θ init are initial lattice parameters from our prediction, model, or, in this case, distorted ground-truth; X (θ k ) is the representation of our proposed crystal structure, which depends on current lattice parameters θ k ; xrd is a map from crystal to computed powder x-ray diffraction pattern; xrd 0 is the xrd pattern of the reference we aim to recover. The projection operator P is defined by relevant crystal family, e.g.,

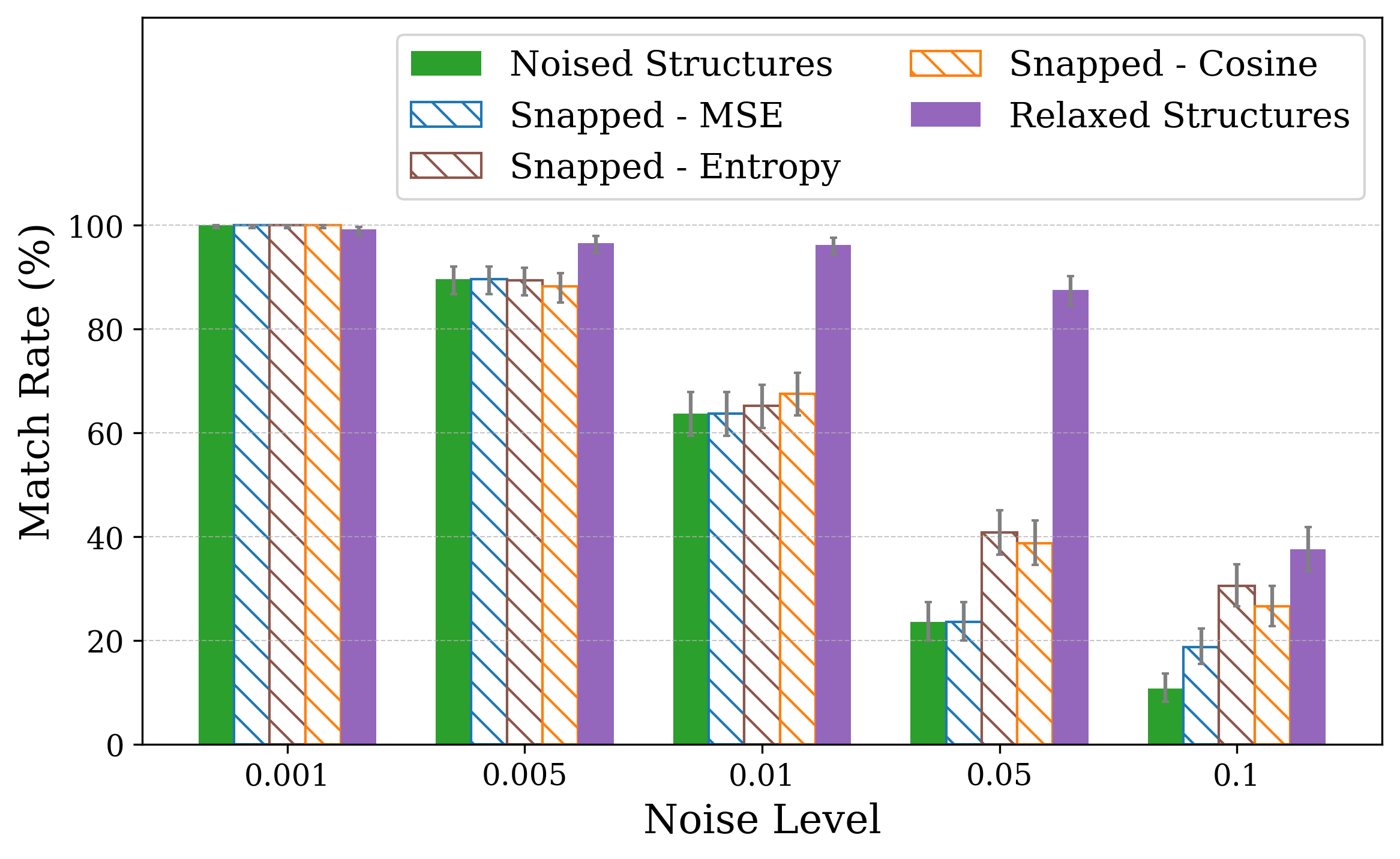

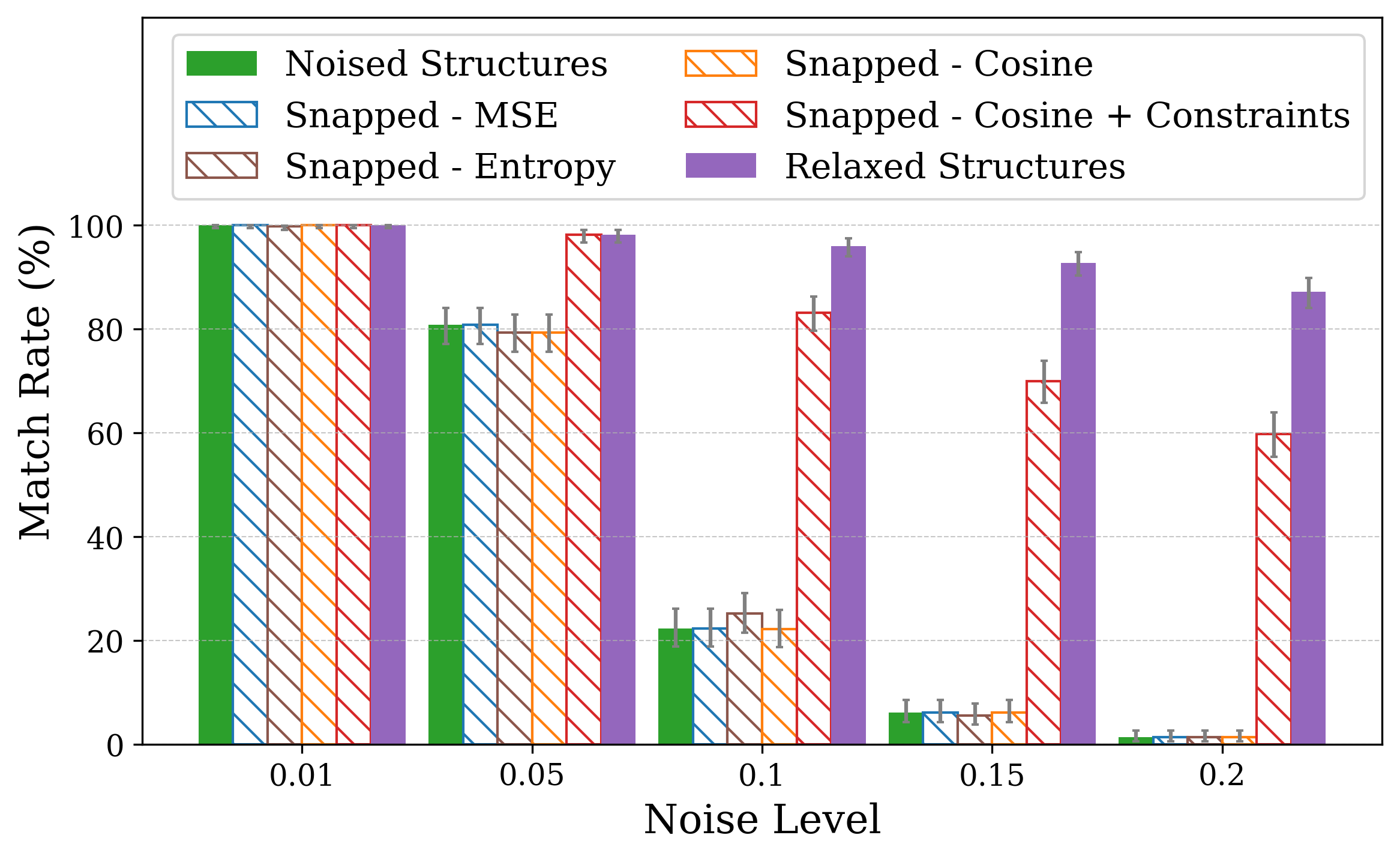

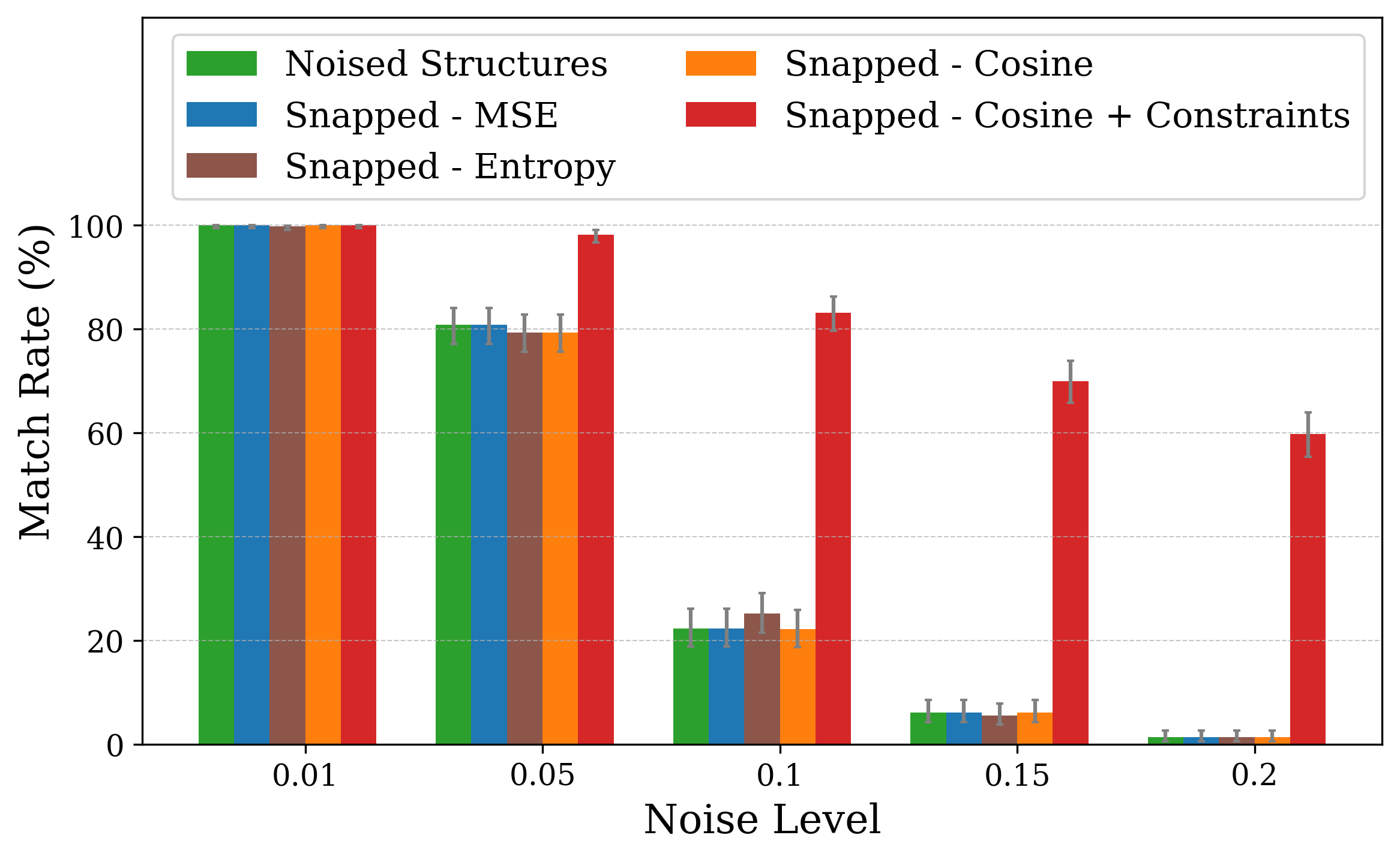

Thus, a, b, and c are first updated independently according to their gradients, then set to the mean value ā, while angles are fixed to 90 • . Similar projectors are defined for the remaining crystal families (see S1.3). Recovery performance is assessed primarily using Match Rate, the fraction of optimized structures that are identified as structurally equivalent to the ground-truth by StructureMatcher [49], considering lattice, atomic positions, and symmetry. The tolerances used are 0.1 for lattice, 0.2 for atomic site positions, and 5 degrees for angles. Additionally, we assess recovery using the Average Minimum Distance (AMD), which serves as a complementary metric for quantifying structural similarity between periodic crystals [50]. While match rate provides a binary classification of whether two Crystal structures were optimized with respect to XRD similarity metrics using the snap method [19], which struggles to recover the correct structure under both lattice and coordinate perturbations. The plots show match rates computed with StructureMatcher (ltol = 0.1, stol = 0.2, angle tol = 5 • ) under random lattice (a) and coordinate (b) perturbations. Error bars represent 95% Jeffreys binomial credible intervals [51]. For lattice distortions, incorporating symmetry constraints significantly improves robustness, even at high noise levels.

structures are equivalent within a given tolerance, AMD offers a continuous measure that compares the distributions of interatomic distances.

We performed optimization on distorted crystal structures across a range of noise types and levels. For each condition, 50 distorted versions were generated for each of 10 ground truth structures, yielding 500 distorted inputs per noise setting. The 50 variations per structure enable a statistical view. We report the match rate of the optimized structures to the ground truth in Figure 1.

Figure 1 illustrates match rates obtained through crystal structure optimization w.r.t XRD similarity metrics. In particular, for lattice distortions, the largest drop occurs between noise levels of 0.05 and 0.1. While 0.1 is the lattice tolerance threshold for matching (see Section 2), the noise level defines the maximum possible strain sampled, so lattice lengths remain within the tolerable range. Using either cosine similarity or MSE as the similarity objective makes little to no difference in performance.

Incorporating symmetry-based constraints during XRD-based optimization notably improves robustness to lattice noise for many structures in this study, as shown in Figure 1a by the higher match rates achieved when constraints are applied. Our constraints (see subsection 2.4) project updates back into the correct crystal family at each optimization step, thereby guiding the search along a reduced-dimensionality symmetry-consistent path and helping the optimizer avoid local minima unrelated to the desired symmetry.

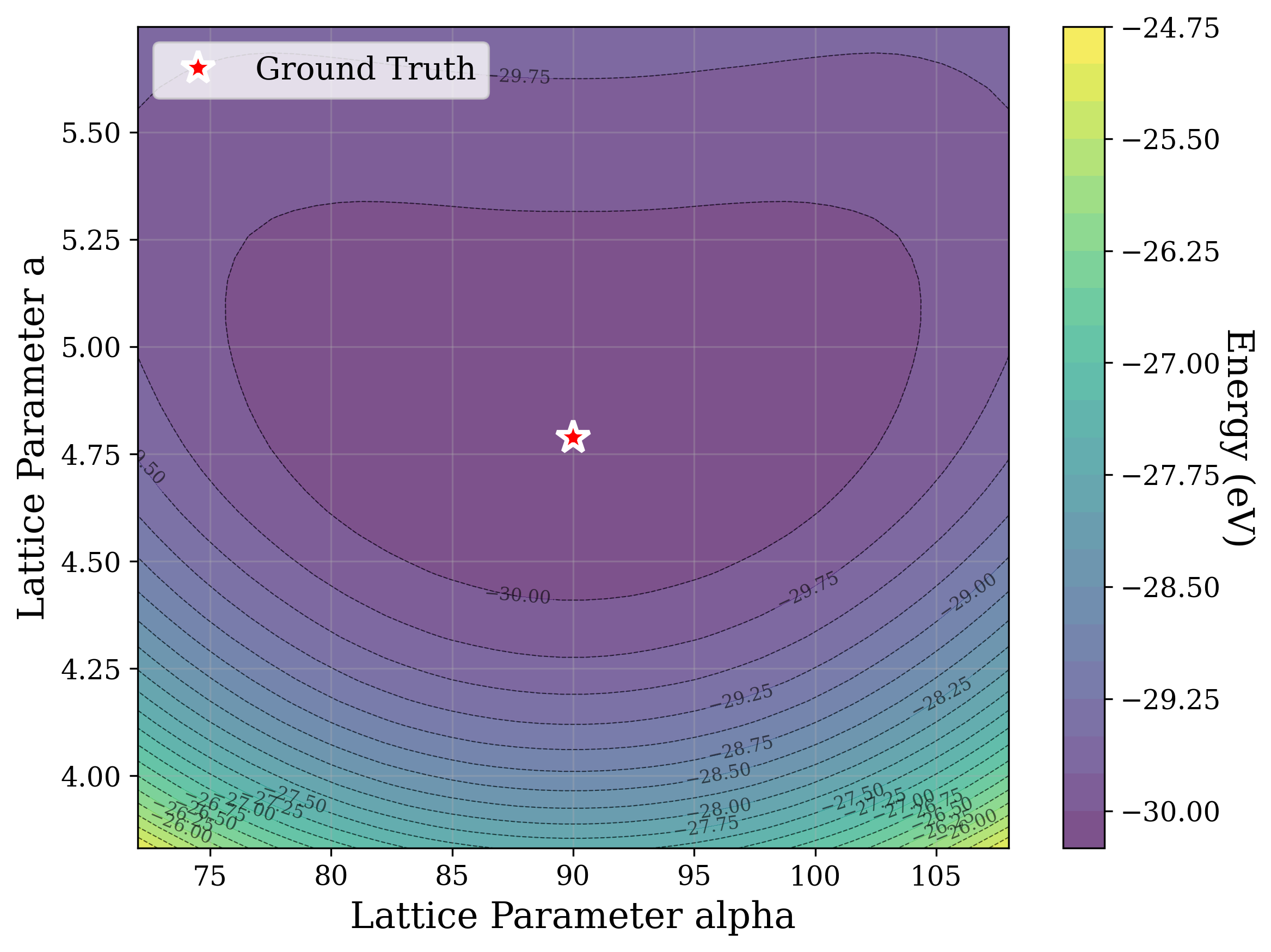

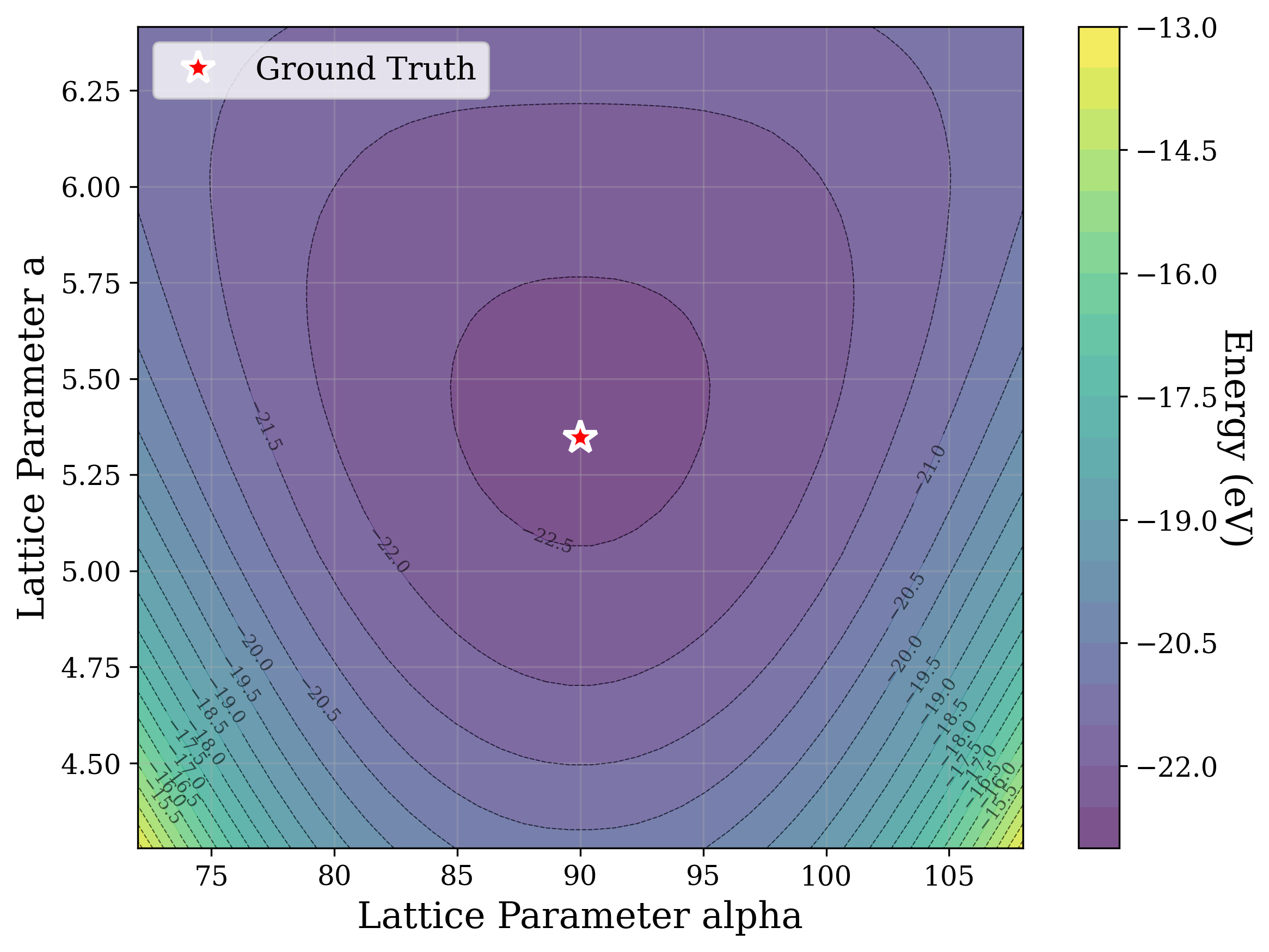

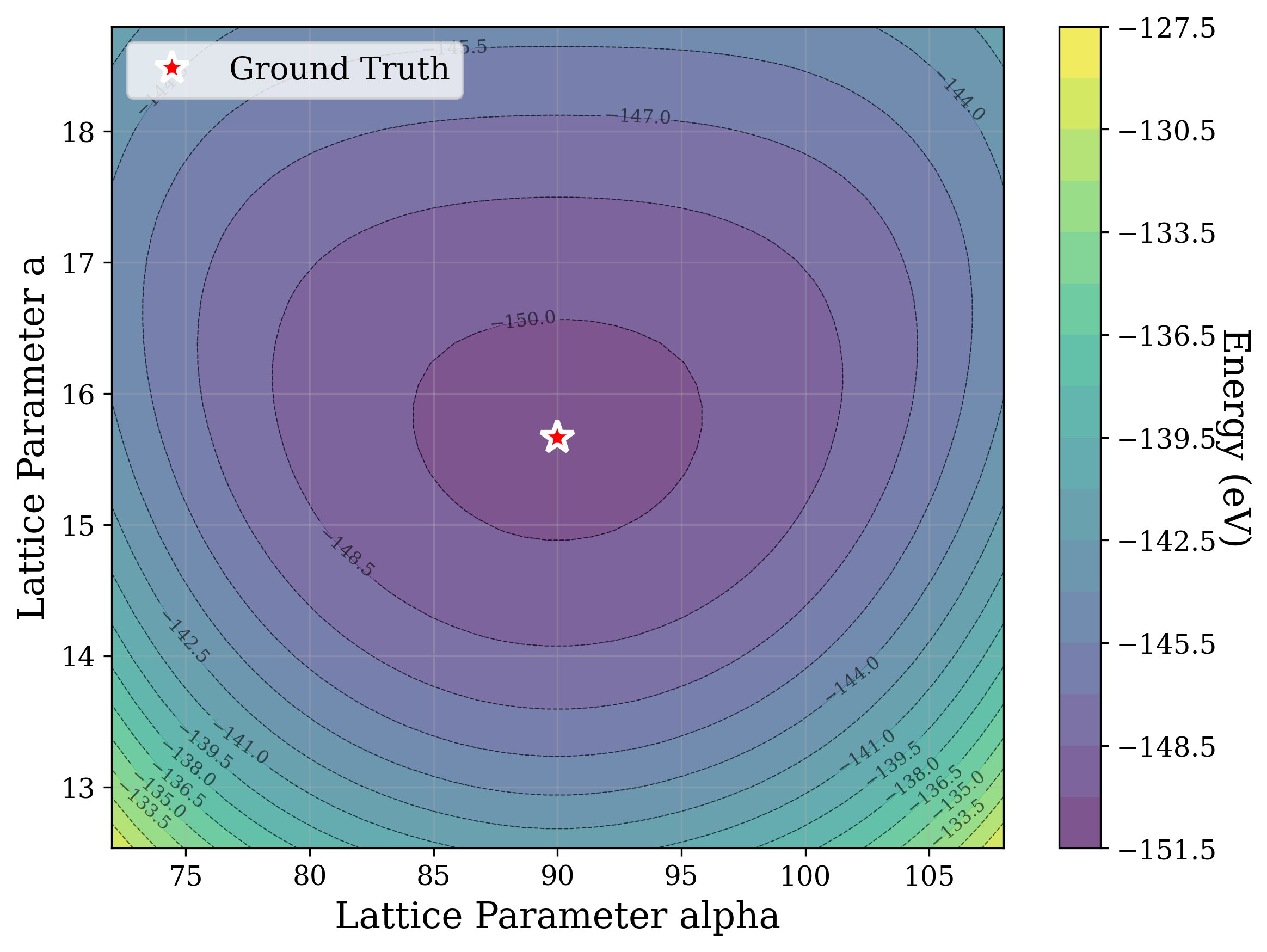

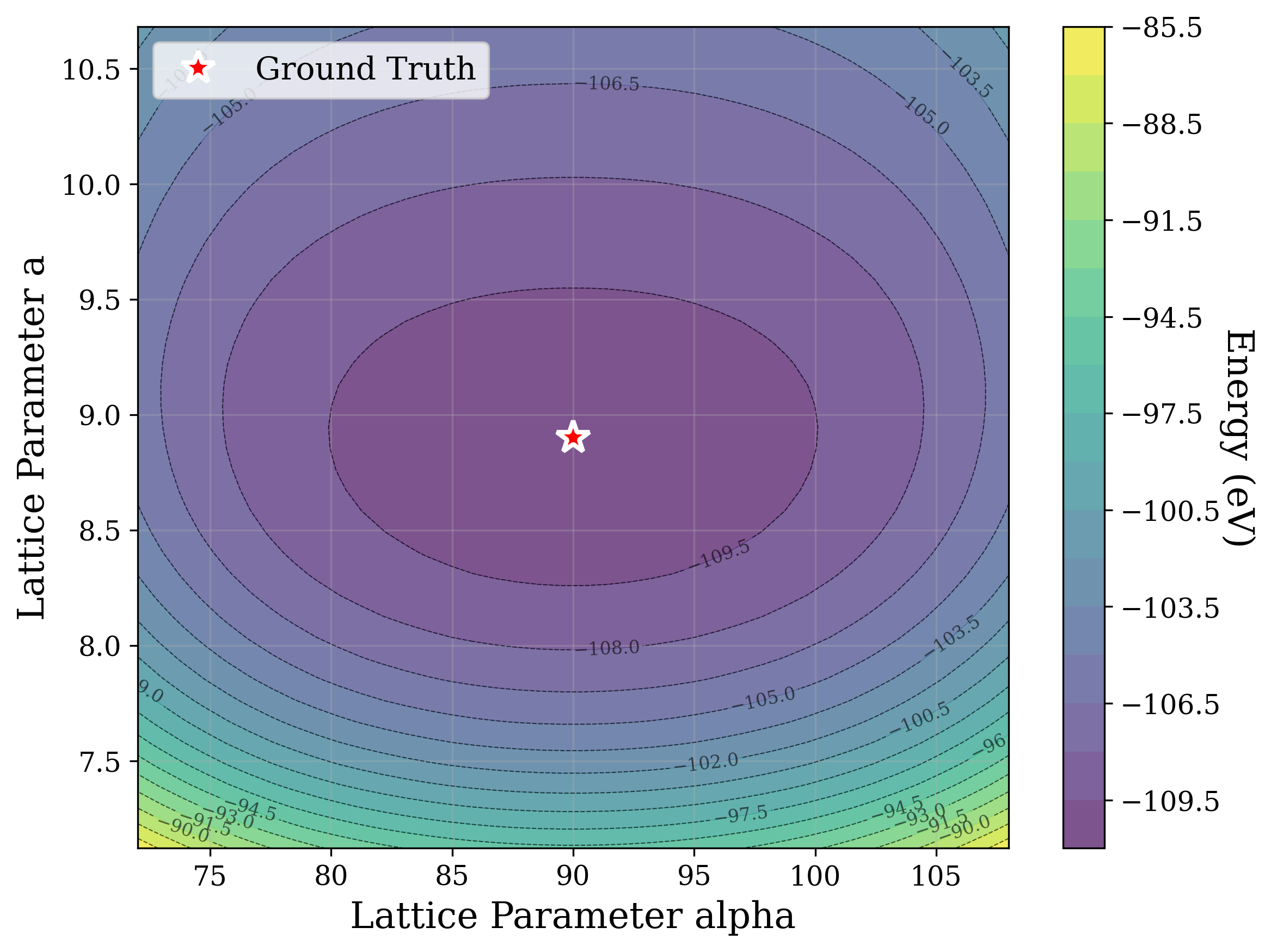

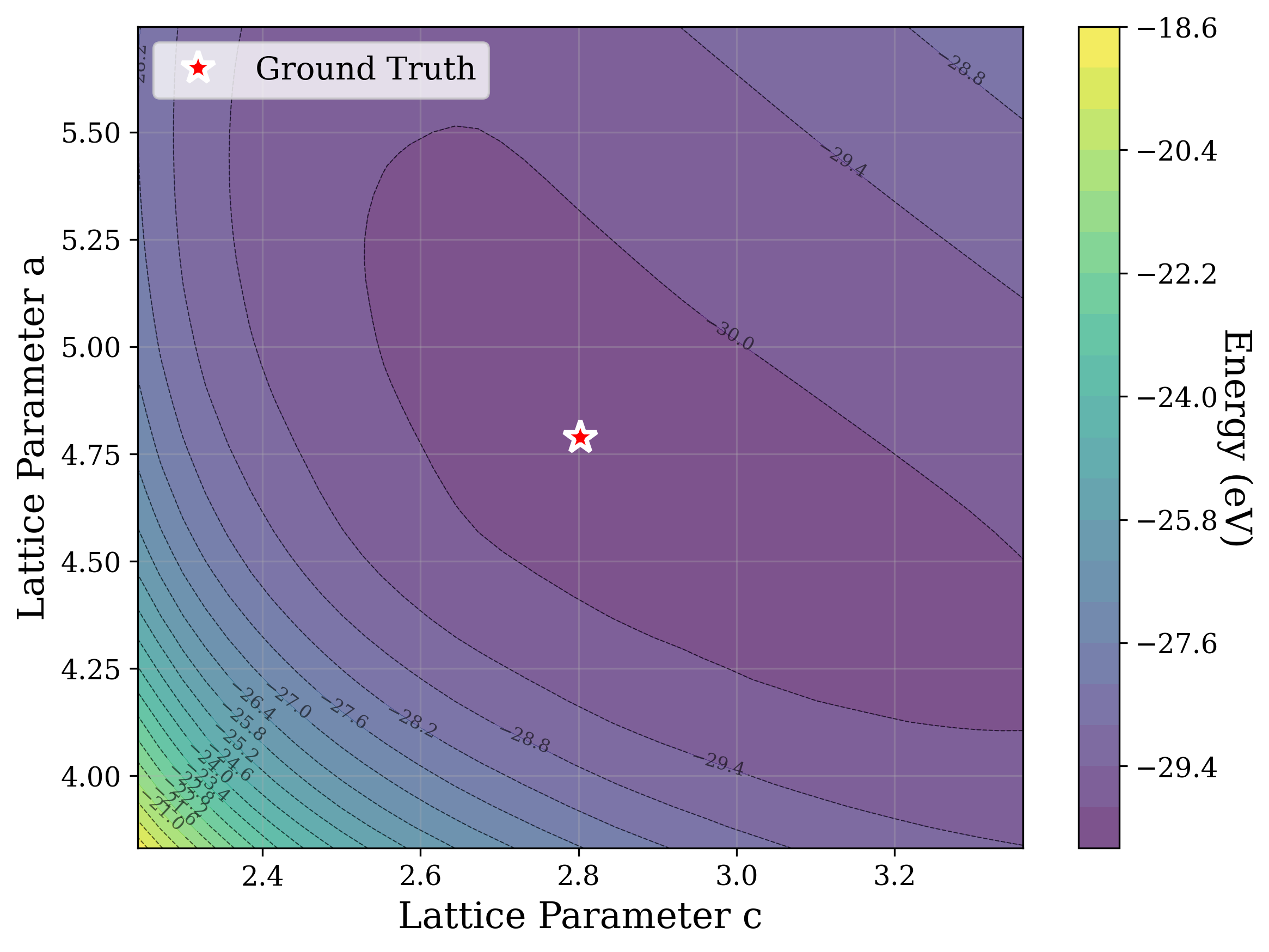

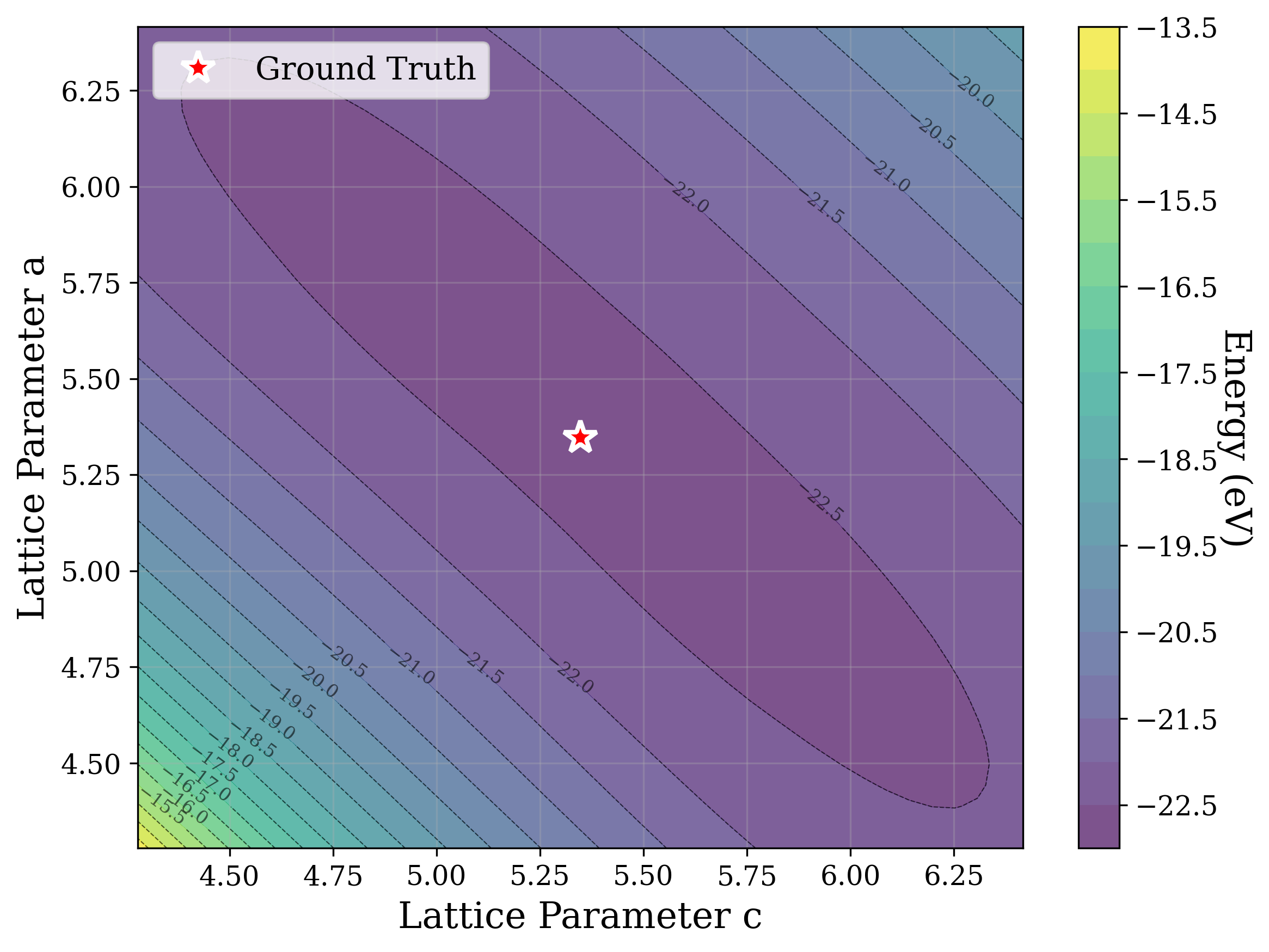

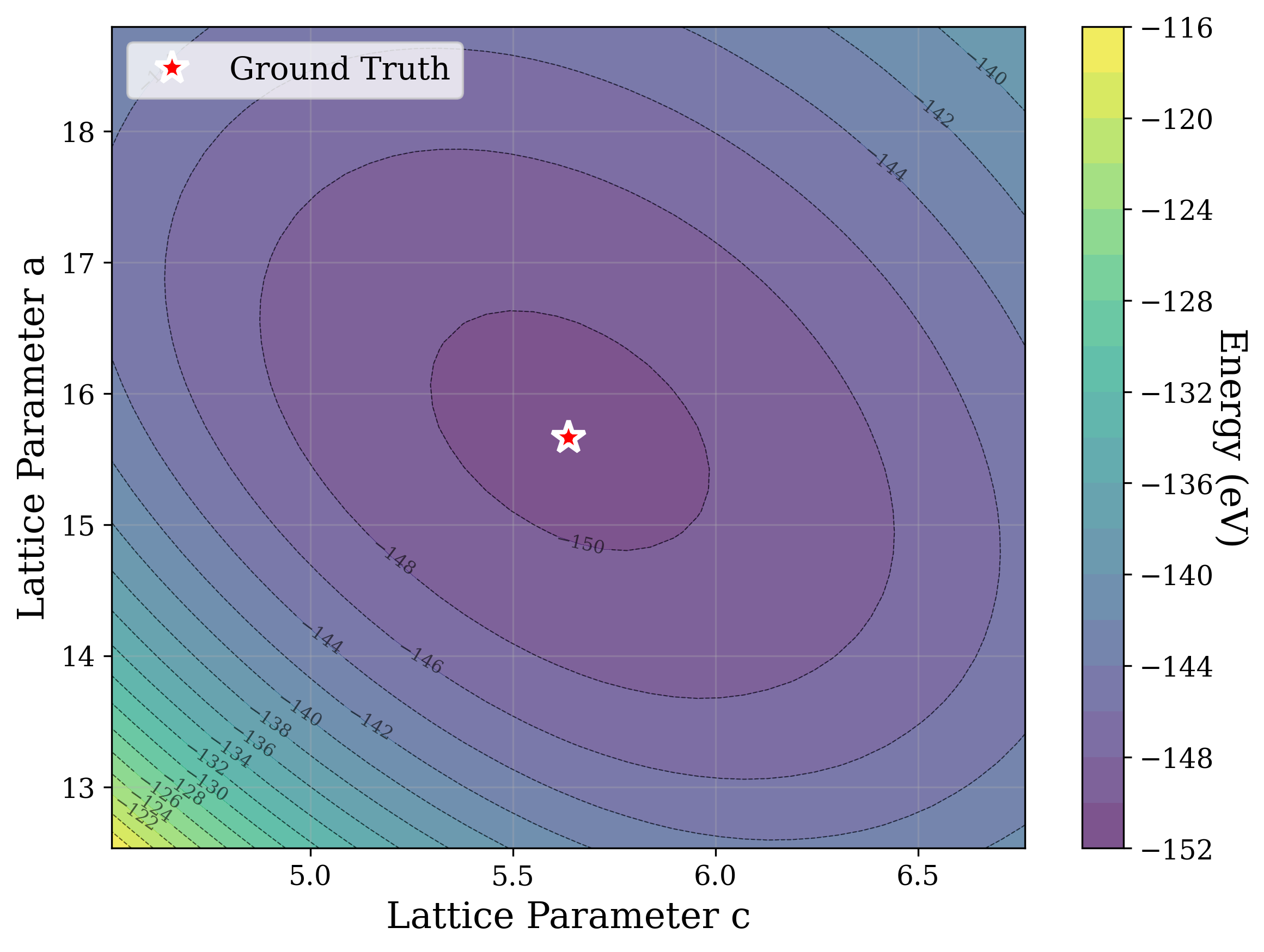

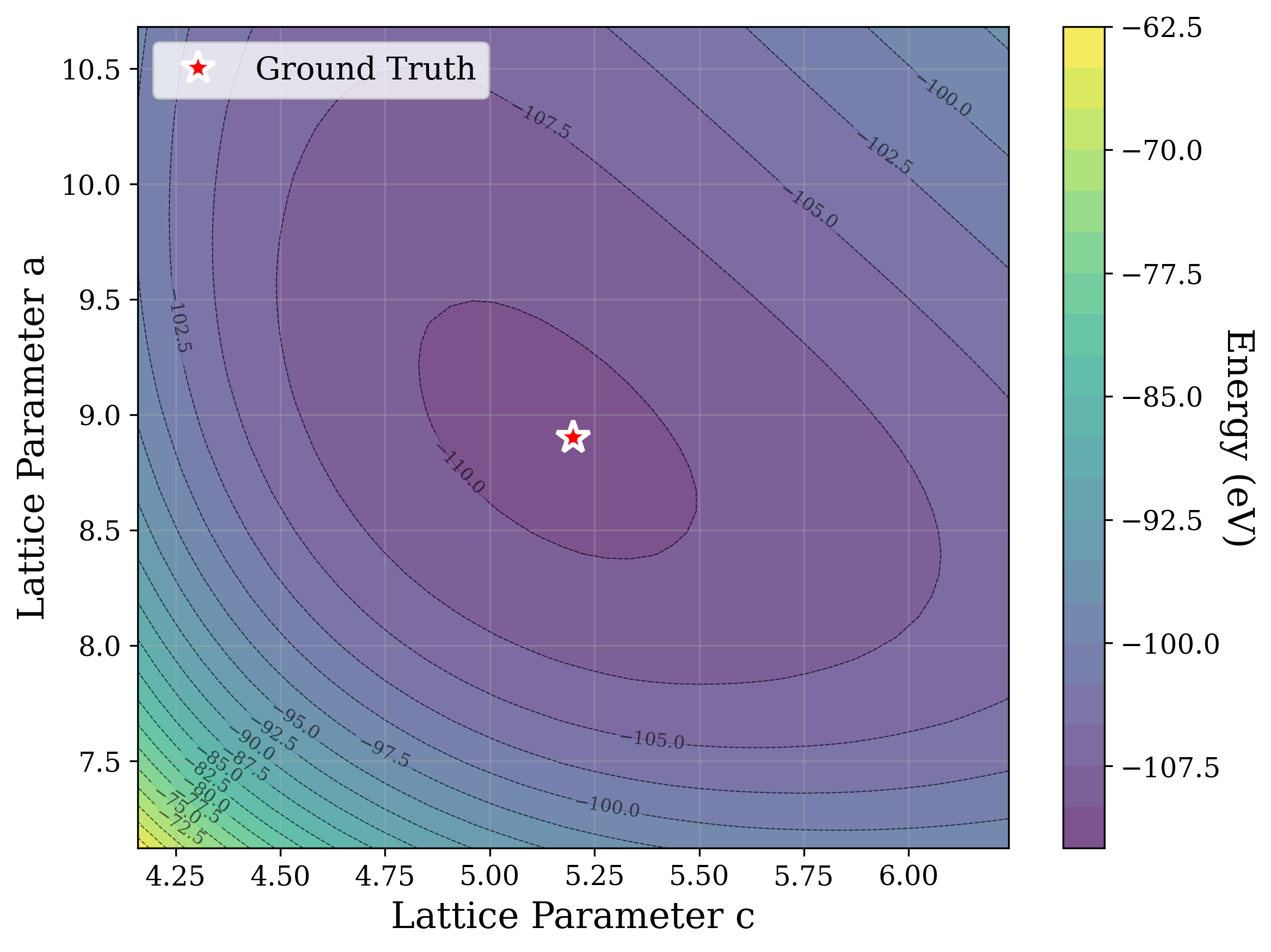

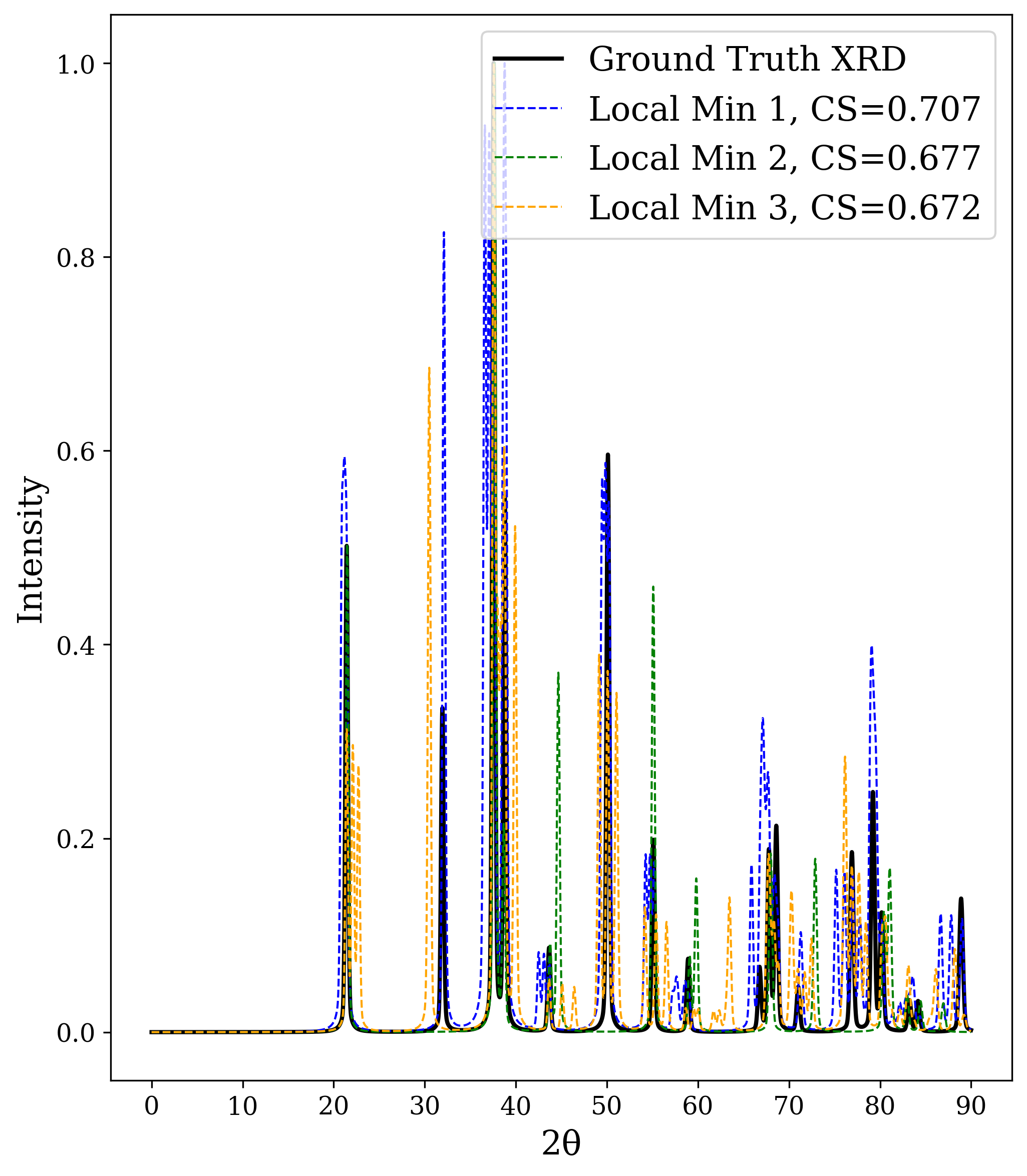

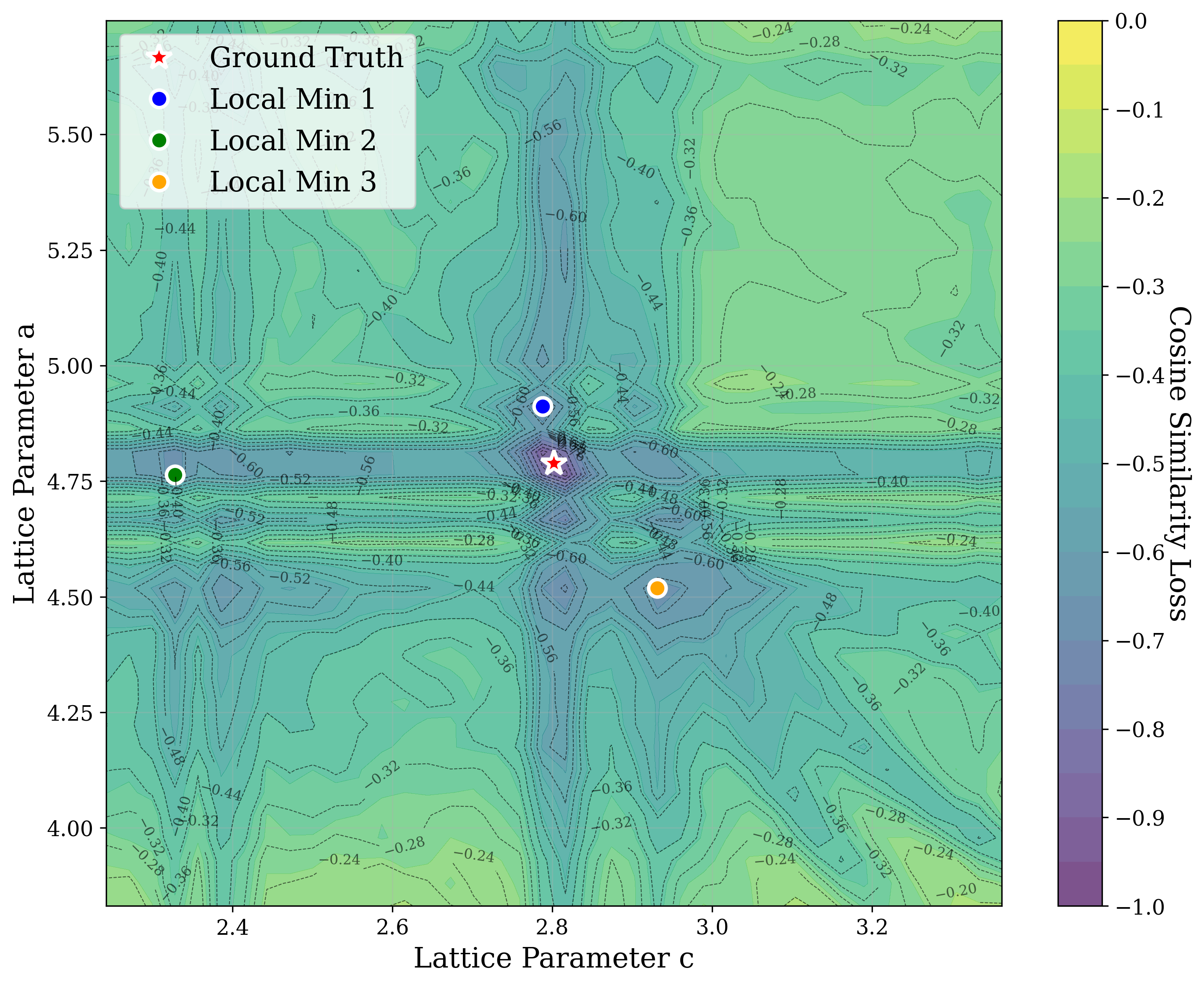

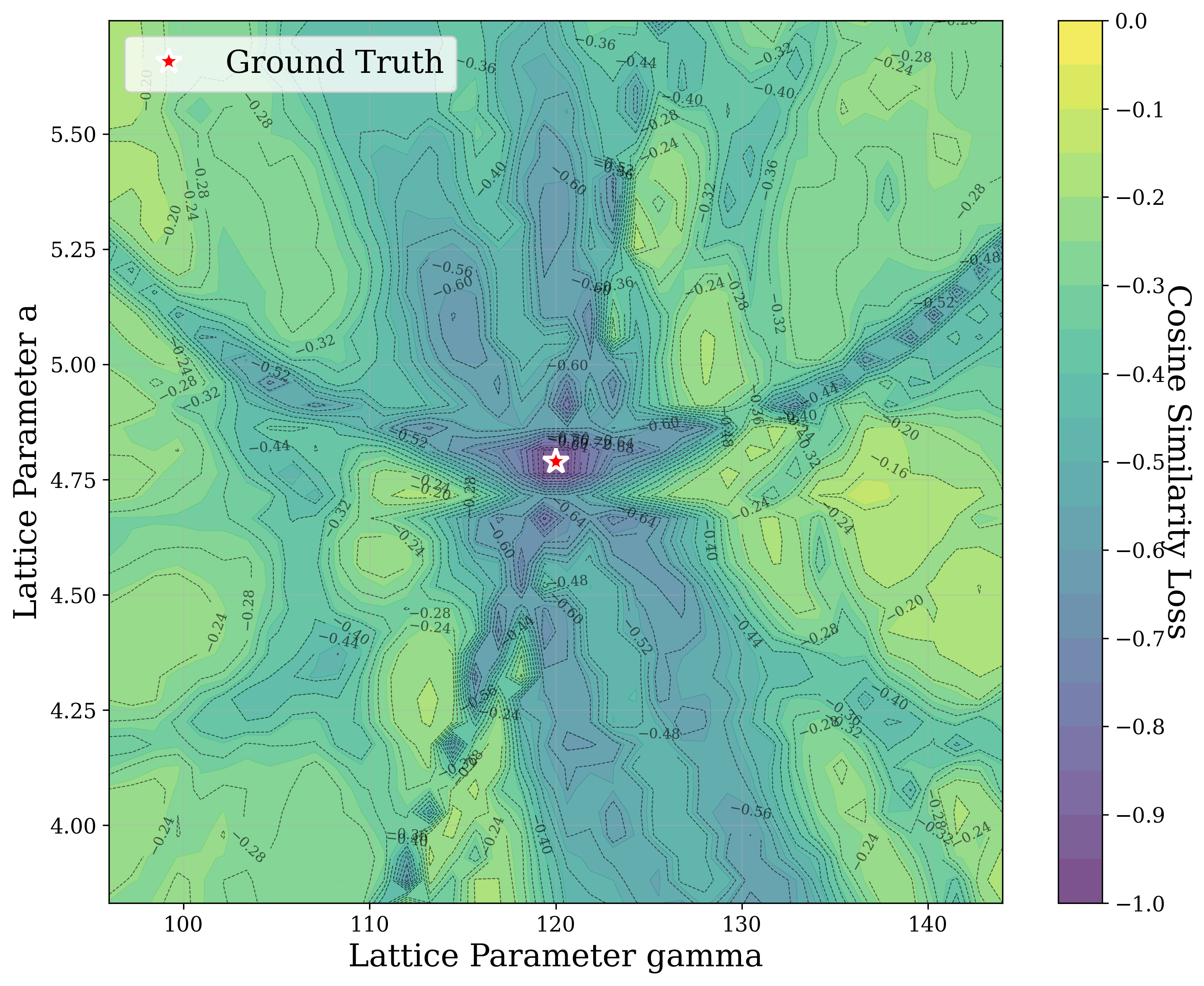

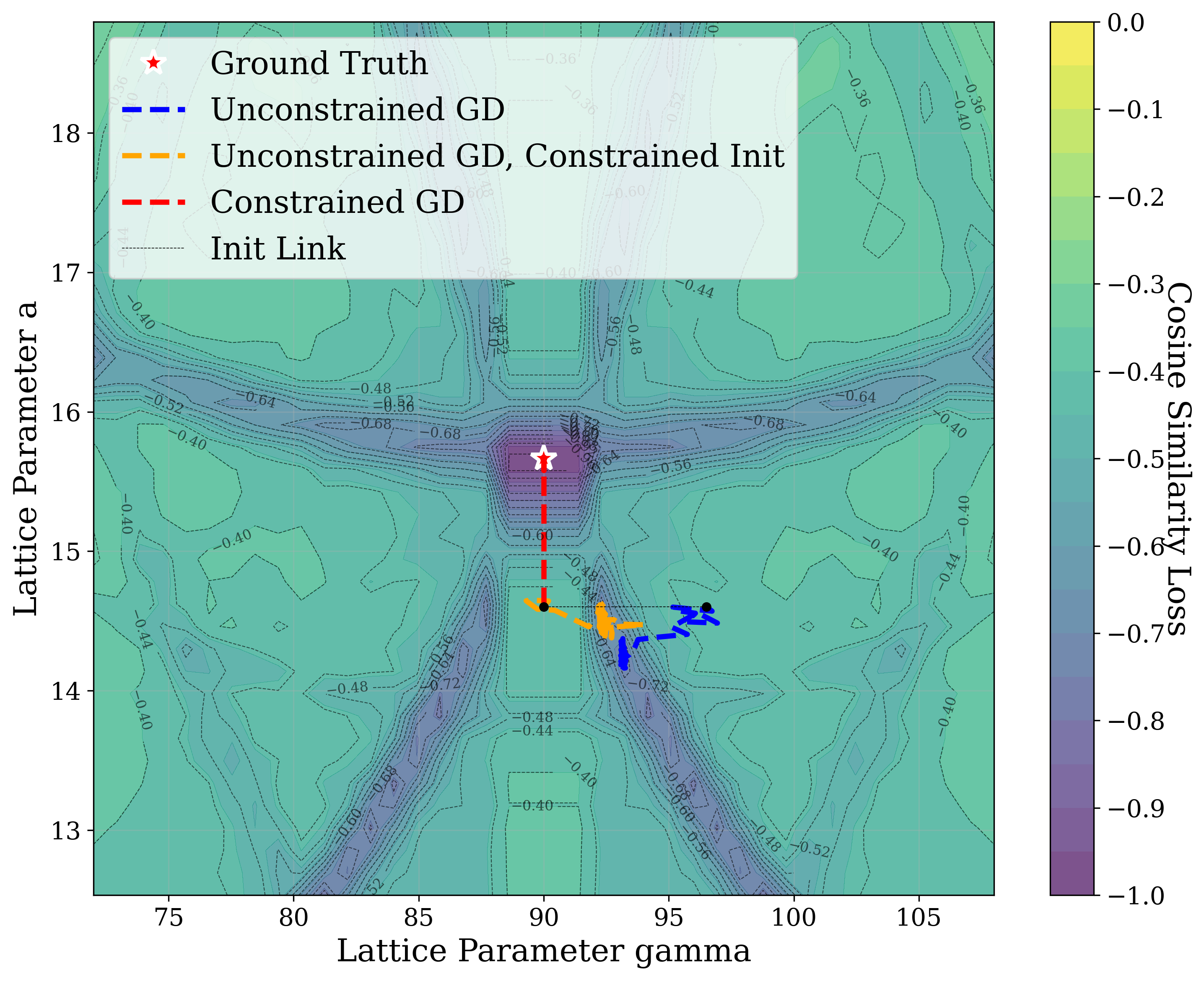

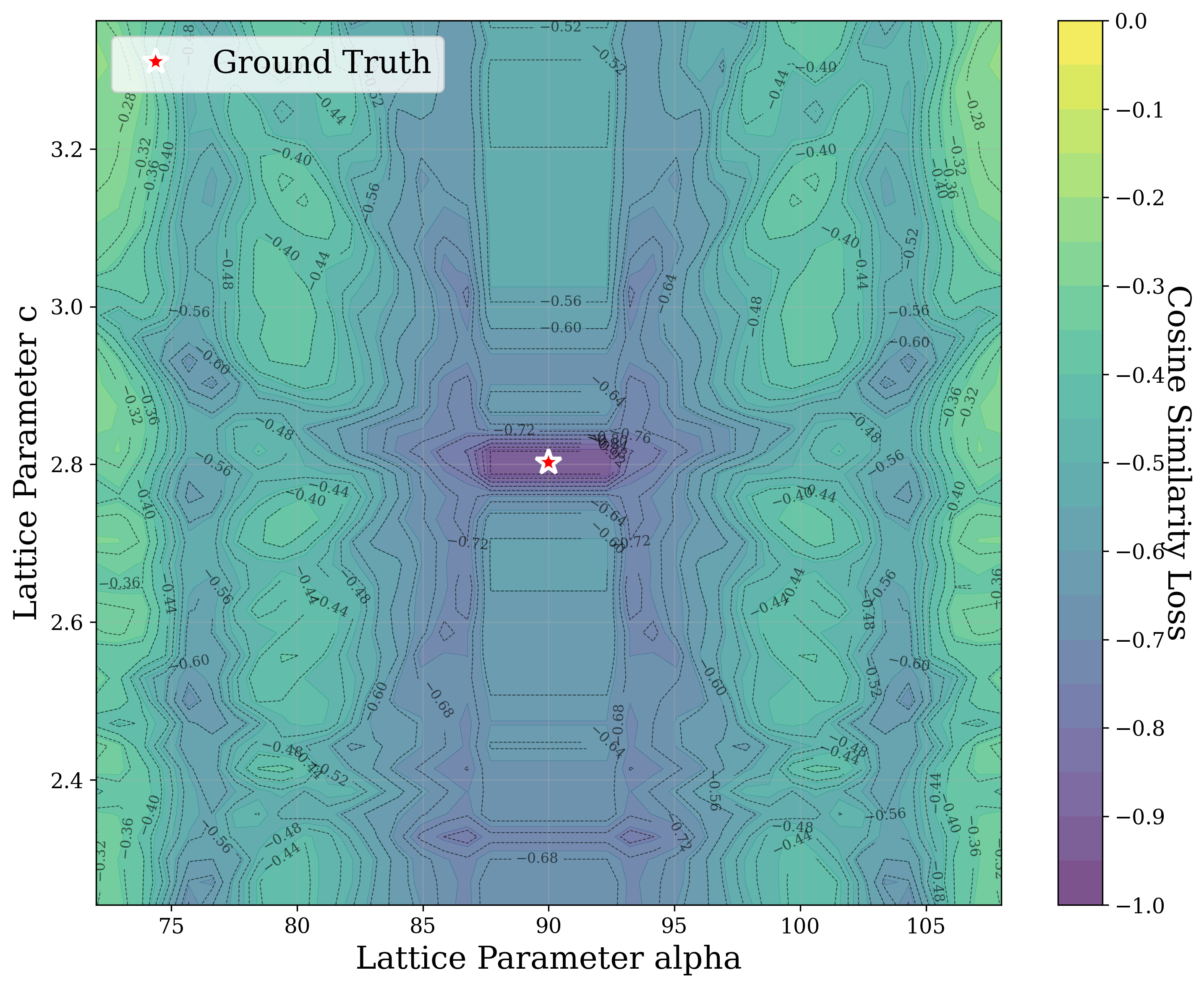

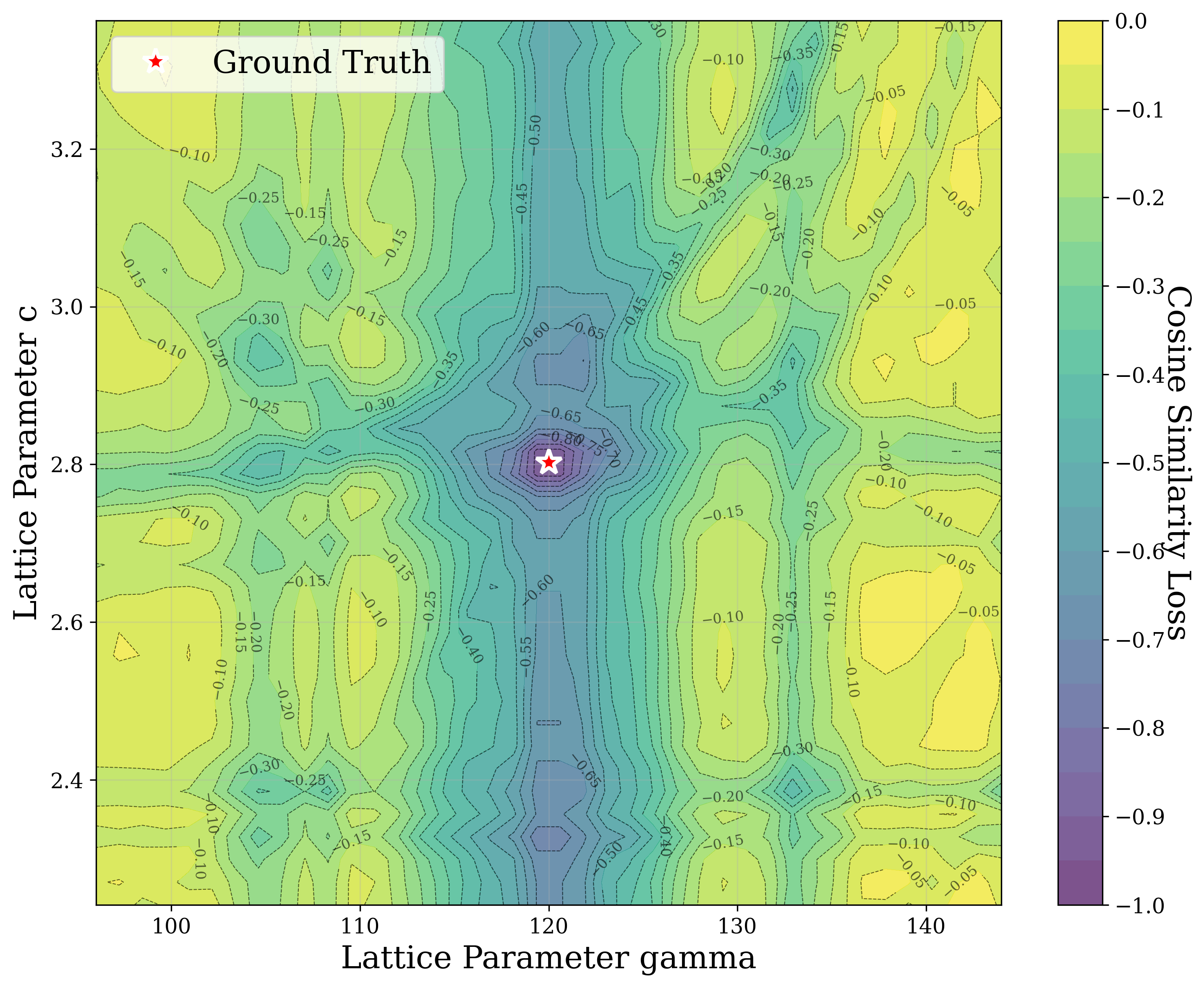

Figures 2,3, and S2 illustrate the non-convex nature of the XRD-based loss landscape with respect to the lattice parameters, shown through 2D cross-sections of the optimization surface. These plots represent simplified views of the underlying optimization process, which, in the case of a distorted lattice, occurs in a six-dimensional space corresponding to the six lattice parameters.

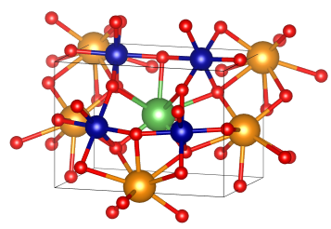

In Figure 2, we distort the lattice parameters a and c of U 2 Ti, a hexagonal structure of space group P6/mmm (No. 191), and compute the cosine similarity loss between distorted structures’ spectra and the ground truth. The resulting contour map reveals multiple deep local minima, indicating the optimizer’s potential to get trapped in suboptimal solutions. The three most prominent local minima are highlighted, and their corresponding XRD patterns are shown in the right panel. Despite their structural deviation from the true lattice parameters, the patterns show high cosine similarity to the ground truth due to subtle shifts and peak splittings that preserve the overall spectral profile.

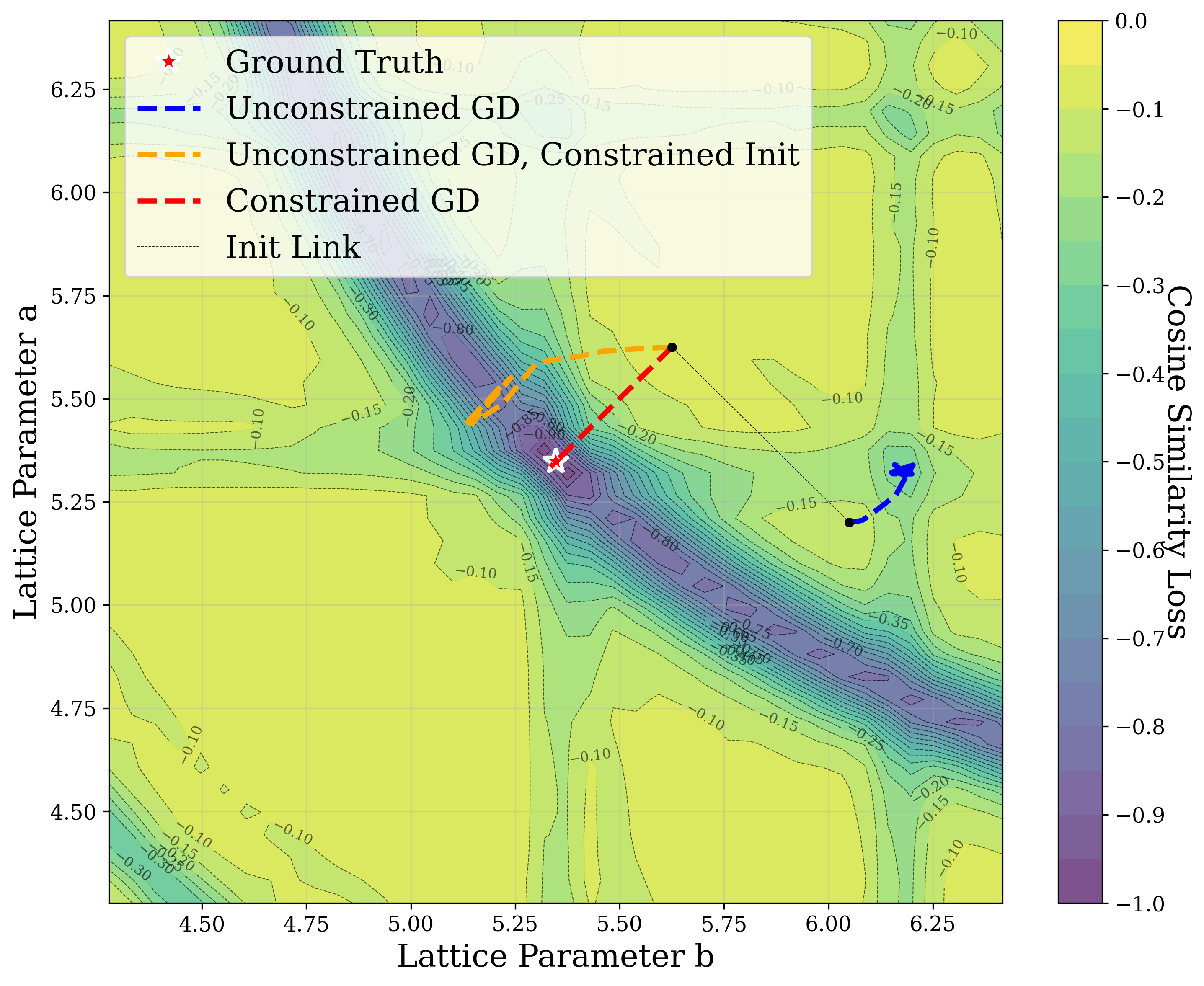

Figure 3 provides two illustrative examples demonstrating how symmetry constraints can facilitate correct structure reconstruction. In these cases, only a twodimensional slice of the optimization landscape is visualized for clarity. This is a simplification of the full optimization process, which, for the distorted lattice case, occurs in a six-dimensional space. We show simulated GD trajectories for two representative structures under three settings: (i) unconstrained GD, (ii) unconstrained GD initialized at a constrained point, and (iii) fully constrained GD.

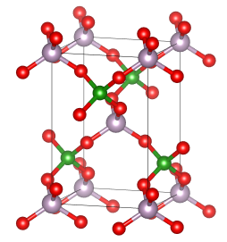

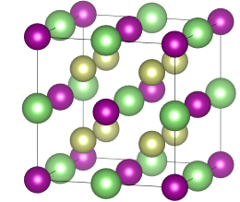

In Figure 3a, we perturb the lattice parameters a and α of Au 2 S, a cubic structure with space group Pn 3m (No. 224). The unconstrained GD trajectory converges to a distant local minimum, whereas unconstrained GD with constrained initialization at a = b reaches a nearby local minimum. By contrast, the fully constrained GD trajectory successfully recovers the ground truth. In Figure 3b, we distort the lattice parameters a and γ of Na 3 MnCoNiO 6 , a monoclinic structure with space group Cm (No. 8). Similarly, the unconstrained GD trajectory, even when initialized at a constrained point with γ = 90 • , converges to a local minimum, while the constrained GD trajectory, which enforces γ = 90 • throughout optimization, reaches the ground truth.

The initialization points for both cases were chosen for illustration, though points for multiple regions would yield similar behavior. These visualizations demonstrate how symmetry-constrained XRD-based optimization can better reach the correct phase, yielding higher match rates than its unconstrained counterpart (Figure 1). This highlights the value of incorporating symmetry constraints into learning schemes that navigate the structure-to-XRD mapping.

Notably, in Figure S2, we observe fluctuations that pose challenges for symmetryconstrained GD along symmetry axes such as a = b and α = 90 • . While fluctuations along a = b are pronounced, those along α = 90 • are comparatively shallow and may be mitigated through techniques such as momentum [52] or regularization, which were not studied in this work. Although symmetry constraints generally improve refinement performance, the landscape visualized here highlights that XRD-based GD may remain sensitive to initialization and prone to local minima in some cases.

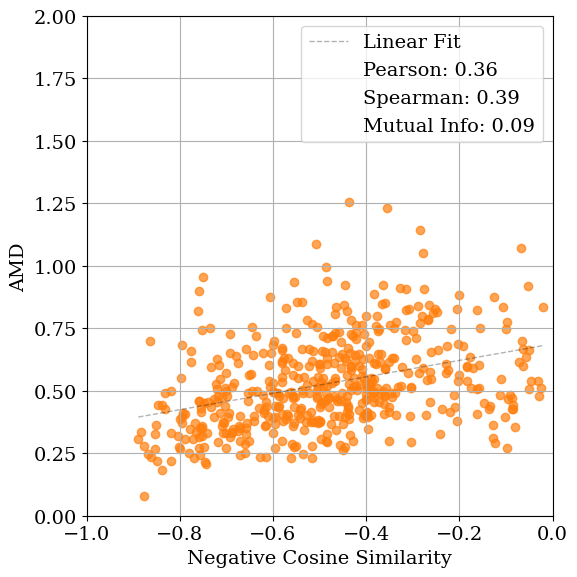

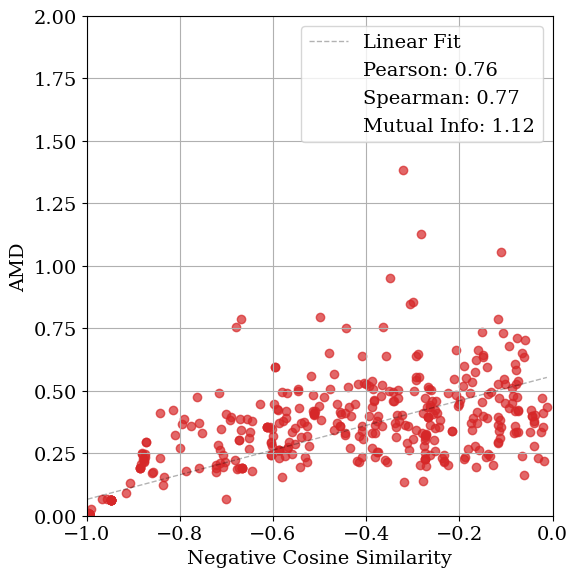

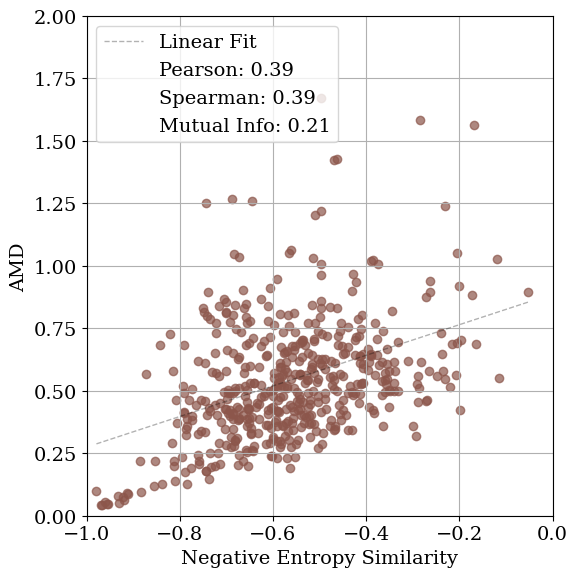

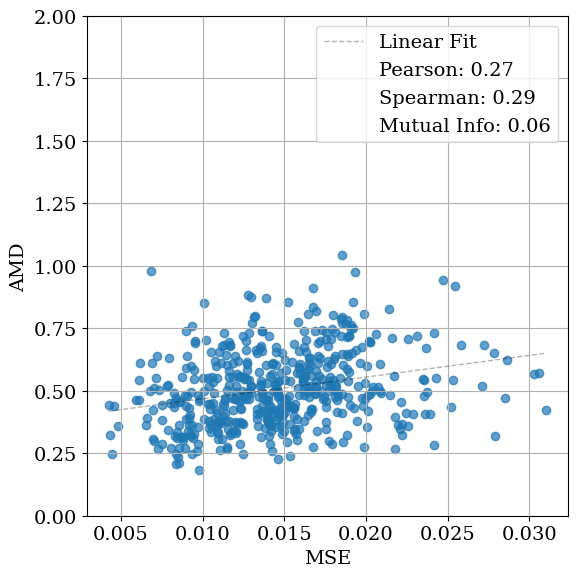

To assess how effectively diffraction-based similarity metrics capture underlying structural similarity, we compare each XRD similarity measure with the Average Minimum Distance (AMD) metric [50]. AMD provides a continuous, geometry-based measure of similarity between periodic structures by computing the Earth Mover’s Distance between the atomic pointwise distance distributions of the ground-truth and optimized structures. For each structure pair, we compare its AMD with the corresponding XRD similarity score and quantify their relationship using Mutual Information (MI), Pearson correlation, and Spearman correlation.

Ideally, higher XRD similarity should correspond to lower AMD, indicating that diffraction-space similarity aligns with structural similarity. MI captures overall statistical dependence between the two quantities, while Pearson and Spearman correlations describe linear and monotonic relationships, respectively.

As shown in Table 1, the relationship between structural and diffraction-based similarity is not uniform across metrics or noise levels. For lattice distortions, cosine similarity yields the highest mutual information (MI) at low noise (1.09), whereas entropy similarity performs best at moderate noise levels (0.53 and 0.21). At higher noise levels, all metrics exhibit similarly low MI, indicating a loss of structural correspondence. A comparable pattern is observed for coordinate distortions. In contrast, when symmetry constraints are enforced during optimization, MI increases substantially across all lattice noise levels, underscoring the benefit of restricting the search space to symmetry-consistent configurations.

The correlation results reported in Tables S1 andS2 exhibit similar trends. For lattice distortions, no single XRD similarity metric consistently correlates with AMD in the unconstrained setting, whereas enforcing symmetry constraints improves both Pearson and Spearman correlations. For coordinate distortions, cosine and entropy similarity metrics show negative correlations with AMD, while the MSE-based metric yields a positive and relatively high Spearman correlation. This behavior can be attributed to the fact that MSE more strongly penalizes differences in peak intensities. Since low-level coordinate noise mainly affects peak heights through modifications to the structure factors rather than shifting peak positions, MSE captures these subtle structural perturbations more effectively.

Figure 4 visualizes these relationships. MSE exhibits the weakest correlation with AMD (low Pearson and Spearman coefficients), while cosine and entropy similarities show comparable correlations. Entropy similarity achieves slightly higher MI (0.20 vs. 0.09 for cosine), indicating a modestly stronger dependence between diffraction and geometric similarity under these conditions. Nevertheless, the data remain broadly scattered, revealing that all tested similarity metrics struggle to consistently distinguish structurally distinct configurations. When symmetry constraints are enforced (Fig. 4d), the correspondence between AMD and cosine similarity improves substantially, both in MI (1.12) and correlation coefficients. In this case, using entropy similarity as the optimization objective yields higher mutual information (MI) than cosine similarity or MSE. However, this trend is not consistent across all noise types and levels (see Table 1). Applying symmetry constraints improves MI as well as linear and Spearman correlations.

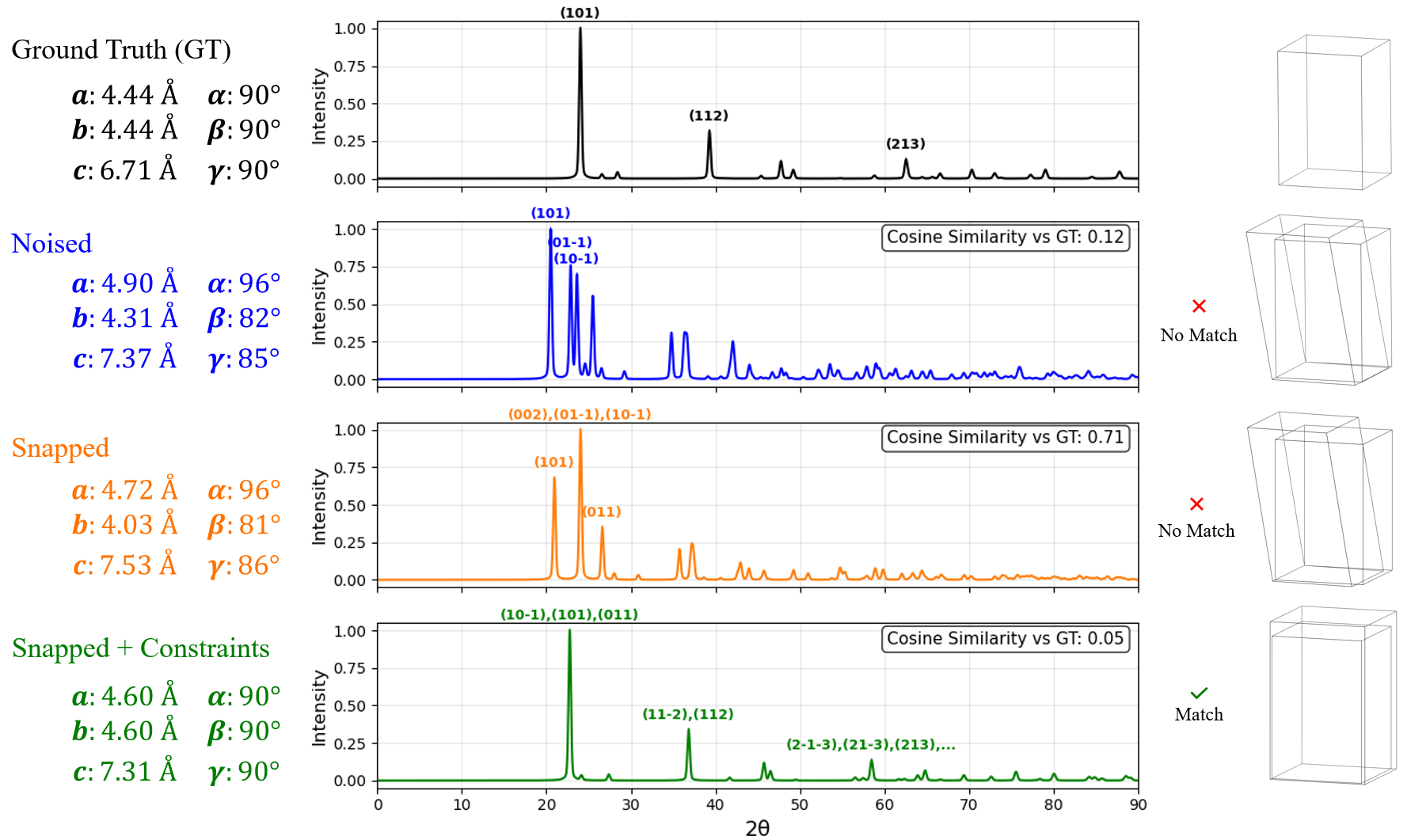

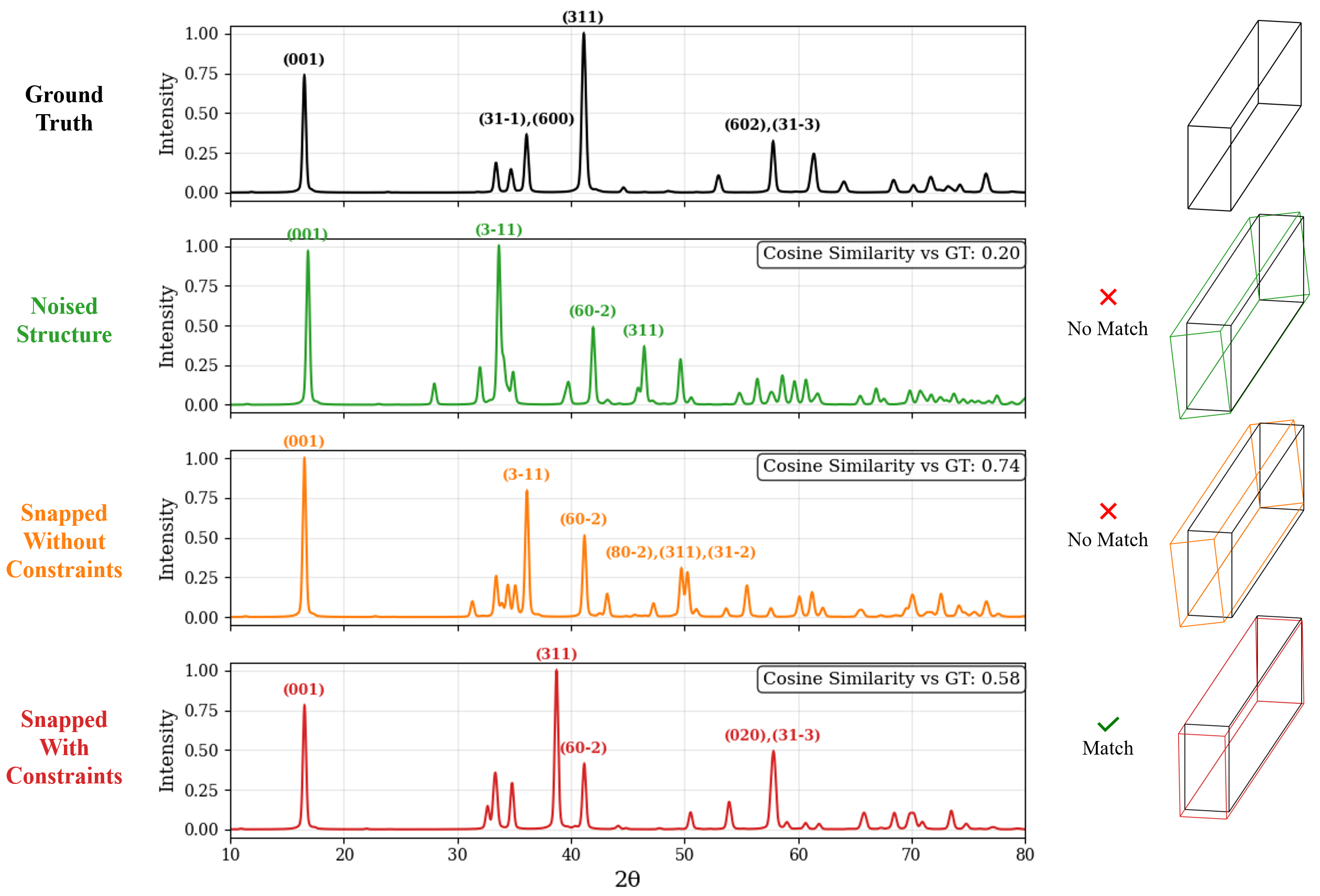

Figure 5 illustrates structure optimization results, with and without lattice constraints. After applying noise, the structure no longer matches the ground truth according to the StructureMatcher metric, with the diffraction pattern exhibiting peak shifts and new reflections. The unconstrained GD optimizer converges to a local minimum where a few peaks align, resulting in a significant increase in cosine similarity (from 0.2 to 0.74). When crystal-family constraints are imposed, the optimizer recovers a structure that matches the ground truth within StructureMatcher tolerance, and the cosine similarity between the patterns increases (from 0.2 to 0.57). However, even in the constrained solution, aligned peaks do not necessarily correspond to identical crystallographic planes, labeled by the Miller indices hkl. E.g., the ground truth 311 plane (top panel) appears slightly shifted in the constrained solution (bottom panel) but aligns with 60 2, thereby contributing to the similarity score. This discrepancy in interatomic distances seems to remain within the tolerance.

In Figure S3, the unconstrained GD optimizer converges to a distinct structure whose peaks overlap with those of the ground truth, achieving a deceptively high cosine similarity (0.71). In contrast, the symmetry-constrained optimization successfully recovers a matched structure, but the resulting diffraction pattern shows slightly shifted peaks, leading to a much lower cosine similarity (0.05). The convergence to this shallow minimum is likely driven by fluctuations along the symmetry axis, as elaborated in subsection 3.1.

This counterintuitive outcome highlights a key limitation of using XRD pattern similarity metrics such as cosine similarity, MSE, and entropy similarity as the sole reconstruction objective: similar structures can yield dissimilar patterns, and conversely, distinct structures may appear similar, under such metrics. Because these metrics are insensitive to whether aligned peaks arise from the same atomic geometry, distinct structures can yield high similarity scores, while small geometric deviations can produce low ones. This results in a highly non-convex optimization landscape prone to spurious minima.

This limitation suggests that purely signal-based metrics are unlikely to yield a well-behaved (e.g., convex) optimization landscape. In the absence of smoother metrics, enforcing symmetry-based constraints (see 2.4) on the optimizer remains an effective way to navigate otherwise rugged landscapes.

Structural relaxation through potential energy minimization is often used [53][54][55][56][57] to refine candidate structures. Figure 6a shows that the universal ML interatomic potential (MLIP) CHGNet [53] accurately recovers structures matching the ground truth from the distorted state alone, except for a high level (0.1) of coordinate noise (Figure 6b). In that case, it is plausible that these larger distortions displace the system into the basin of attraction of a different local minimum on the potential energy surface. These results suggest that the loss landscape of energy relaxation is much smoother than that of XRD similarity [58]. Cross-sections of the energy optimization landscape are shown in Figures 6b andS4, showcasing a smooth and convex behavior.

Energy relaxation and XRD-based optimization provide complementary signals: relaxation drives structures toward physically stable configurations, while XRD-based optimization attempts to match an observed pattern. Possible directions for future work can therefore include multi-objective optimization, which can combine the smoothness of the energy landscape with the structure-specific information captured by diffraction.

XRD provides a direct experimental link for generative crystal modeling, enabling the identification of novel phases. Our results highlight symmetry’s role in bridging XRD and structure, but also reveal that in some cases the XRD-to-structure landscape may remain non-convex even along symmetry axes, making post-hoc optimization difficult. We illustrate this with physically motivated random distortions, though generative models may introduce more complex biases. The observations in this work suggest that progress in inverse XRD can be made using new generative architectures that condition on XRD and embed symmetry as an inductive bias, with final refinements guided by energy relaxation.

We follow Riesel et al. [19] and compute diffraction patterns from the structure factor contributions of each atomic site, in a differentiable way. Lattice parameters are converted to a real-space cell, the reciprocal lattice is derived, and all allowed Miller indices within the maximum scattering vector are generated. For each (hkl), reciprocal distances and diffraction angles are calculated, elemental scattering factors are retrieved and weighted by site occupancies, and intensities are obtained by squaring the modulus of the summed structure factor with a Lorentz-polarization correction. We calculate XRD peak profiles using the Pseudo-Voigt approximation, which models the peak shape as a linear combination of Gaussian and Lorentzian components:

where G(x) is the Gaussian function, L(x) is the Lorentzian function, and η ∈ [0, 1] is the mixing parameter controlling the relative contributions.

For a peak centered at 2θ 0 , the Gaussian and Lorentzian components are given by:

where H G and H L are the full widths at half maximum (FWHM) for the Gaussian and Lorentzian profiles, respectively.

In practice, peak broadening in XRD is described by the Caglioti relation:

where U , V , and W are the Caglioti parameters. This equation gives the squared FWHM as a function of diffraction angle, and is applied separately for the Gaussian and Lorentzian widths, i.e., H G (2θ) and H L (2θ). The parameters account for instrumental and sample-dependent broadening effects.

We compute the total XRD pattern by summing pV (x) contributions from all Bragg reflections over 2θ ∈ [0 • , 90 • ], and then discretize the intensity into bins of width 0.01 • . We adopt Caglioti parameterss U = 0.1, V = 0.01, W = 0.1 and η = 0.1. This produces a fixed-length xrd vector, x, of size 9000 for each structure.

For each crystal family, the symmetry projector P maps the given lattice parameters (a, b, c, α, β, γ) to the symmetrized parameters consistent with the family:

Each optimization run was performed for a maximum of 30,000 iterations, with batch sizes of 16. For lattice distortions, the learning rates explored were between 0.0005 and 0.01. For coordinate distortions, the learning rates explored were between 1e-04 to 1e-06. The XRD parameters U , V , and W (see Appendix Section S1.2) were kept fixed at [0.1, 0.01, 0.1], the same values used for generating the ground truth XRD patterns used for reference. Optimization was terminated early if the convergence tolerance of 10 -4 in the loss function between 1000 steps was reached.

For lattice distorted structures, the lattice lengths and angles were optimized jointly while atomic coordinates were held fixed. For coordinate distortions, only coordinates were optimized. The loss functions considered included negative cosine similarity, negative entropy similarity, and mean squared error (MSE). In the MSE case, to ensure numerical stability, reflections were subject to physics-based clipping within Miller indices up to [h, k, l] max = 6.

For comparison with relaxation-based methods, structures were relaxed using CHGNet [53]. For distorted coordinates, relaxation was done with the BFGS optimizer. For the distorted lattice case, relaxation was done with the FrechetCellFilter and BFGS optimizer. The relaxation process was terminated once the maximum atomic force (f max ) fell below 0.02 eV/ Å.

📸 Image Gallery