Pianist Transformer: Towards Expressive Piano Performance Rendering via Scalable Self-Supervised Pre-Training

📝 Original Info

- Title: Pianist Transformer: Towards Expressive Piano Performance Rendering via Scalable Self-Supervised Pre-Training

- ArXiv ID: 2512.02652

- Date: 2025-12-02

- Authors: Hong-Jie You, Jie-Jing Shao, Xiao-Wen Yang, Lin-Han Jia, Lan-Zhe Guo, Yu-Feng Li

📝 Abstract

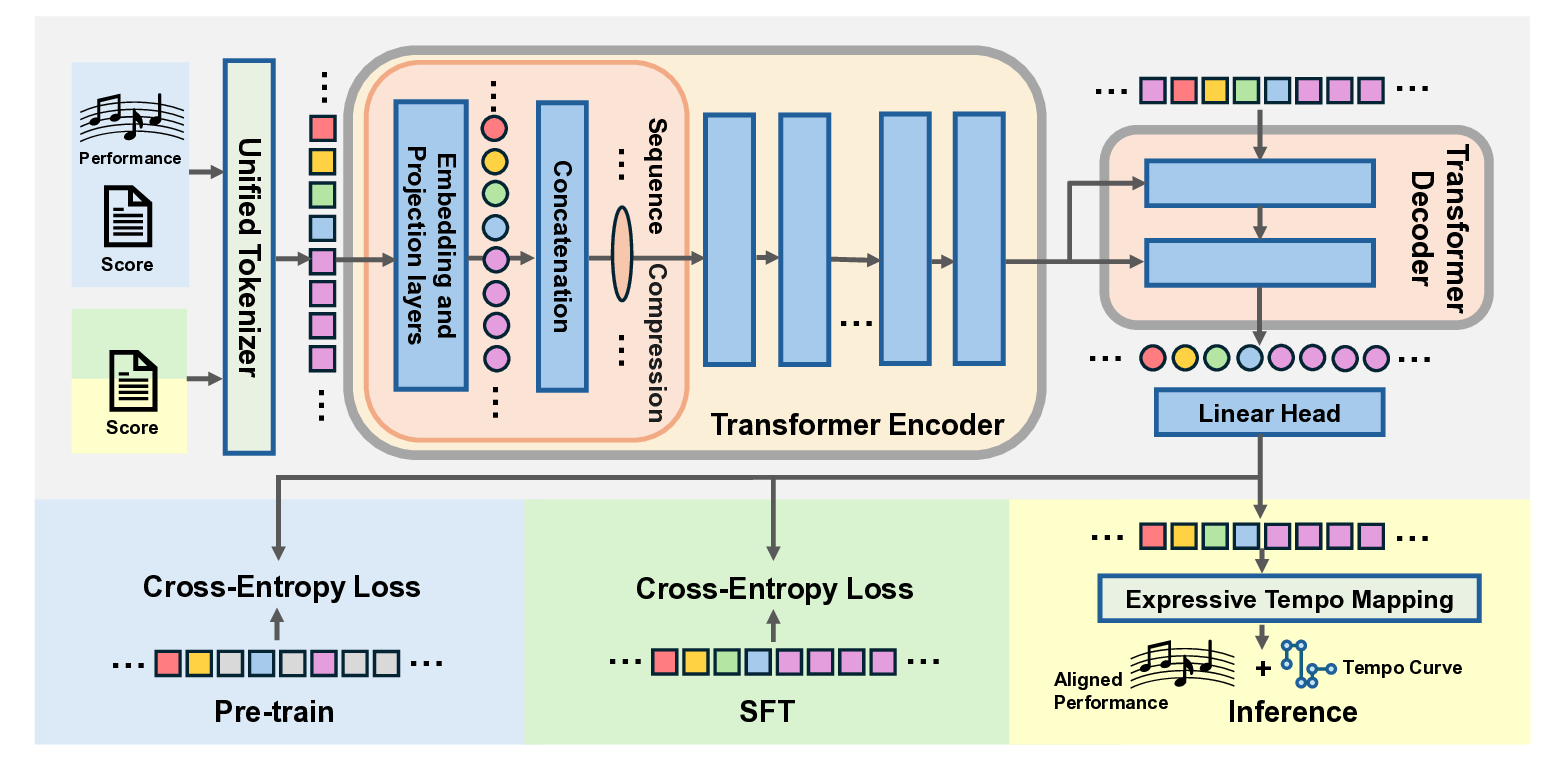

Existing methods for expressive music performance rendering rely on supervised learning over small labeled datasets, which limits scaling of both data volume and model size, despite the availability of vast unlabeled music, as in vision and language. To address this gap, we introduce Pianist Transformer, with four key contributions: 1) a unified Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) data representation for learning the shared principles of musical structure and expression without explicit annotation; 2) an efficient asymmetric architecture, enabling longer contexts and faster inference without sacrificing rendering quality; 3) a self-supervised pre-training pipeline with 10B tokens and 135M-parameter model, unlocking data and model scaling advantages for expressive performance rendering; 4) a state-of-the-art performance model, which achieves strong objective metrics and human-level subjective ratings. Overall, Pianist Transformer establishes a scalable path toward human-like performance synthesis in the music domain.📄 Full Content

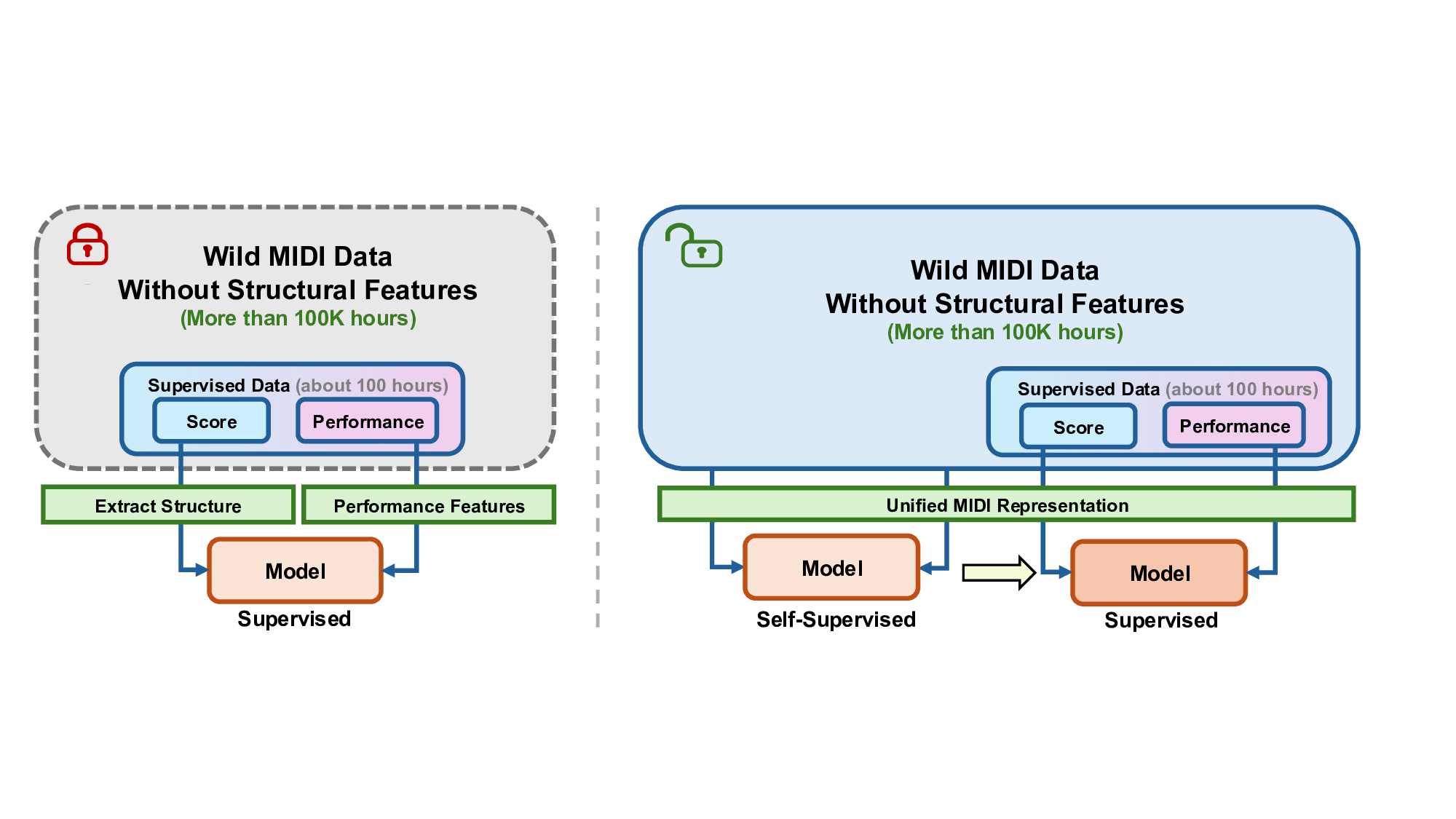

To maximize the utilization of the limited dataset, existing works often adopt asymmetric, specialized representations, injecting rich structural descriptors on the score side (e.g., measures, meter) (Jeong et al., 2019b;Maezawa et al., 2019;Borovik & Viro, 2023). This improves label efficiency because each labeled example delivers explicit structural cues rather than forcing the model to infer them. However, these descriptors require a notated score and a score-performance alignment. In contrast, performance MIDI is typically captured from digital-piano recordings or produced by AI transcription and thus consists of a stream of note events without explicit measures, meter, or a usable tempo map. As a result, such methods cannot compute their required structural features for the vast, unaligned corpora of performance-only MIDI, making them ill-suited for leveraging unsupervised data at scale (Figure 1, Existing systems operate under a strictly supervised pipeline that depends on scarce aligned datasets (≈ 100 hours) and cannot exploit the vast in-the-wild MIDI corpus (> 100K hours). This reliance on explicit structural features fundamentally limits scalability. (Right) Our Scalable Self-Supervised Paradigm: Pianist Transformer shifts the paradigm by making large-scale self-supervised learning feasible for expressive piano performance rendering. Through the unified MIDI representation, the model can pre-train on over 100K hours of unaligned MIDI to acquire rich musical priors, and then generalize effectively through supervised fine-tuning. left). Renault et al. (2023) explores an adversarial, cycle-consistent architecture that disentangles score content from performance style, and a score-to-audio generator learns to render expressive piano audio from unaligned data against a realism discriminator. Nevertheless, adversarial training is challenging to scale due to complex training dynamics, and the resulting generation quality has so far been limited. A more stable and scalable paradigm is desirable to truly harness the potential of the vast, unaligned corpora of in-the-wild MIDI performances that remain largely untapped (Figure 1, right).

In this paper, we present Pianist Transformer, a model for expressive performance rendering trained with large-scale unlabeled MIDI corpus. Our main contributions are as follows:

Unified Data Representation: We introduce a single, fine-grained MIDI tokenization that encodes notated scores and expressive performances in the same discrete event vocabulary. By closing the representation gap between these modalities, this shared formulation makes unaligned, performance-only MIDI directly usable for pre-training, scaling to 10B MIDI tokens without explicit score-performance alignment, while preserving data diversity. In this unified space, the model can learn not only the “grammar” of music but also the statistical links between score-level structure and expressive controls (timing, dynamics, articulation, and pedaling).

We design an asymmetric encoder-decoder architecture with note-level sequence compression that merges the fixed per-note event bundle into one token, reducing encoder self-attention cost by 64×. This concentrates compute in a single parallel pass, alleviates the decoding bottleneck, and yields longer context coverage and faster inference with strong rendering quality. Compared with a symmetric architecture, it delivers 2.1× faster inference, meeting low-latency requirements for real-world use without sacrificing expressive quality.

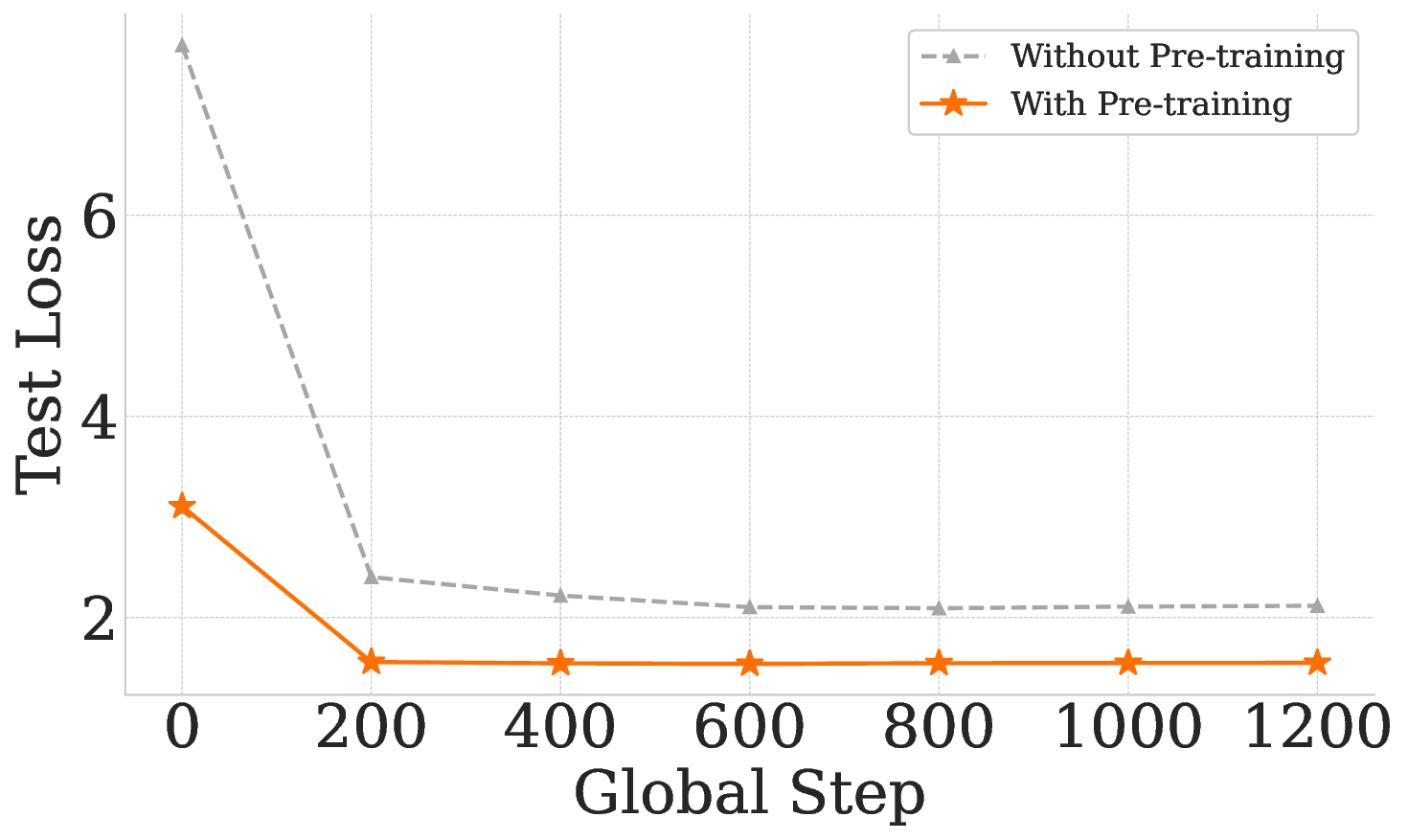

We adopt a self-supervised pre-training scheme that furnishes the model with an initialization, internalizing common musical regularities and expressive patterns. Consequently, during downstream supervised fine-tuning the model starts from a stronger representation, converges faster and to a substantially lower loss than an otherwise identical model trained from scratch, and achieves stronger objective metrics. In particular, a scratch model tends to plateau at a higher loss and produces weaker expressive distributions, whereas the pre-trained model begins from a superior foundation and continues to improve throughout fine-tuning. To bridge model generation and practical music-production workflows, we introduce Expressive Tempo Mapping, a post-processing algorithm that converts model outputs into editable tempo maps. This produces an editable format suitable for real-world use while preserving expressive timing.

The overall training recipe yields a state-of-the-art expressive performance model. On objective metrics, it outperforms strong baselines. In a comprehensive listening study, its outputs are statistically indistinguishable from a human pianist and are more preferred.

Piano Performance Rendering. The goal of performance rendering is to synthesize an expressive, human-like performance from a symbolic score. The field has evolved from early rule-based (Sundberg et al., 1983) and statistical models (Teramura et al., 2008;Flossmann et al., 2013;Kim et al., 2013) to deep learning architectures based on RNNs (Cancino-Chacón & Grachten, 2016), variational autoencoders (Maezawa et al., 2019), graph neural networks (Jeong et al., 2019b), and Transformers. For instance, recent work such as ScorePerformer (Borovik & Viro, 2023) has focused on fine-grained stylistic control, a goal complementary to our focus on scalable pre-training. Despite these architectural innovations, progress has been bottlenecked by the supervised learning paradigm; the small, costly aligned datasets it requires are insufficient for models to learn the complex mapping from musical structure to expressive nuance. This reliance limits model scalability and generalization. While recent work has explored adversarial training on unpaired data to bypass alignment (Renault et al., 2023), challenges with training stability and quality remain. This underscores the need for a robust paradigm that can effectively leverage vast, unaligned data, which we propose through large-scale self-supervised pre-training.

Self-Supervised Learning in Music. Self-supervised pre-training, a dominant paradigm in NLP (Devlin et al., 2019;Brown et al., 2020) and computer vision (Chen et al., 2020;He et al., 2022), has also been adapted for music. In the symbolic domain, early efforts like MusicBERT (Zeng et al., 2021) applied masked language modeling to MIDI for understanding tasks. This approach has recently been scaled up significantly: Bradshaw et al. (2025) pre-trained on large piano corpora for tasks like melody continuation, while foundation models like Moonbeam (Guo & Dixon, 2025) have been trained on billions of tokens for diverse conditional generation. Parallel efforts also exist for raw audio using contrastive or reconstruction objectives (Spijkervet & Burgoyne, 2021;Hawthorne et al., 2022). However, the application of self-supervised pre-training to the specific task of expressive performance rendering is largely unexplored. While existing self-supervised models excel at learning high-level musical semantics for tasks like generation or classification, performance rendering is a distinct, fine-grained challenge centered on modeling subtle expressive details. Whether the benefits of large-scale selfsupervised pre-training can successfully transfer to this nuanced, performance-level domain is an open question that motivates our work.

Our goal is to develop a powerful piano performance rendering system that can leverage large-scale, unlabeled data through a self-supervised pre-training paradigm. This section details our approach, beginning with the core of our methodology: a unified data representation that enables large-scale pre-training. We then describe the Transformer-based architecture and the two-stage training strategy built upon this representation. Finally, we introduce a novel post-processing step that ensures the model’s output is practical for musicians.

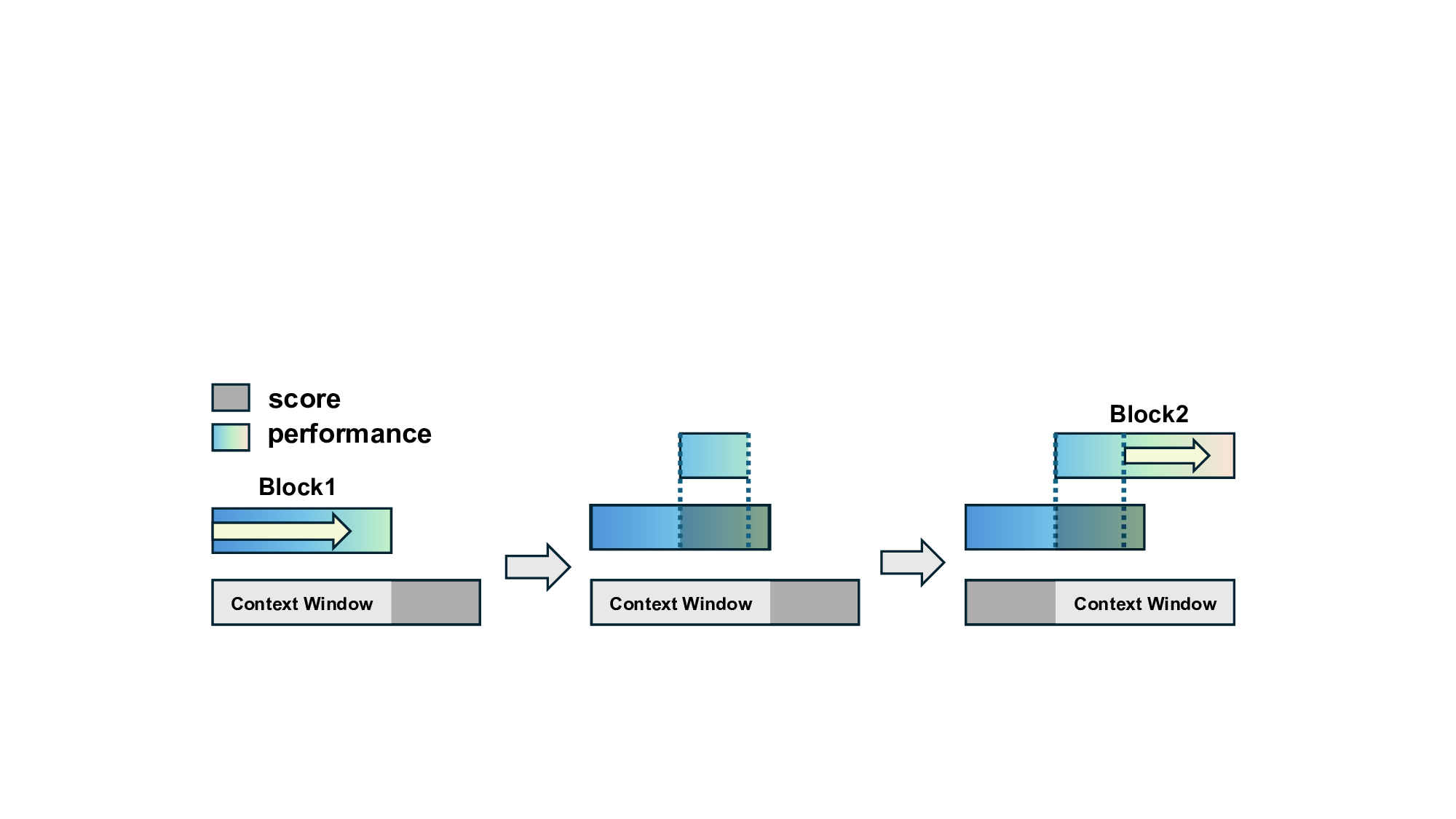

A fundamental challenge in applying self-supervised learning to performance rendering is the disparity between structured score data and expressive performance data. Specifically, scores represent music with symbolic, metrical timing (e.g., quarter notes, eighth notes) and categorical dynamics (e.g., p, mf, f), while performances are captured as streams of events with absolute timing in milliseconds and continuous velocity values. To overcome this, we propose a unified, event-based token representation (2) SFT: Supervised Fine-Tuning adapts the model to map musical context to expressive nuances using aligned score-performance pairs, where it takes the score tokens as input and predicts the corresponding performance tokens.

(3) Inference:

The model takes a score input and then generates a performance, which is then made editable for DAWs by our Expressive Tempo Mapping algorithm.

that treats both formats identically, enabling them to be mixed in a single, massive pre-training corpus.

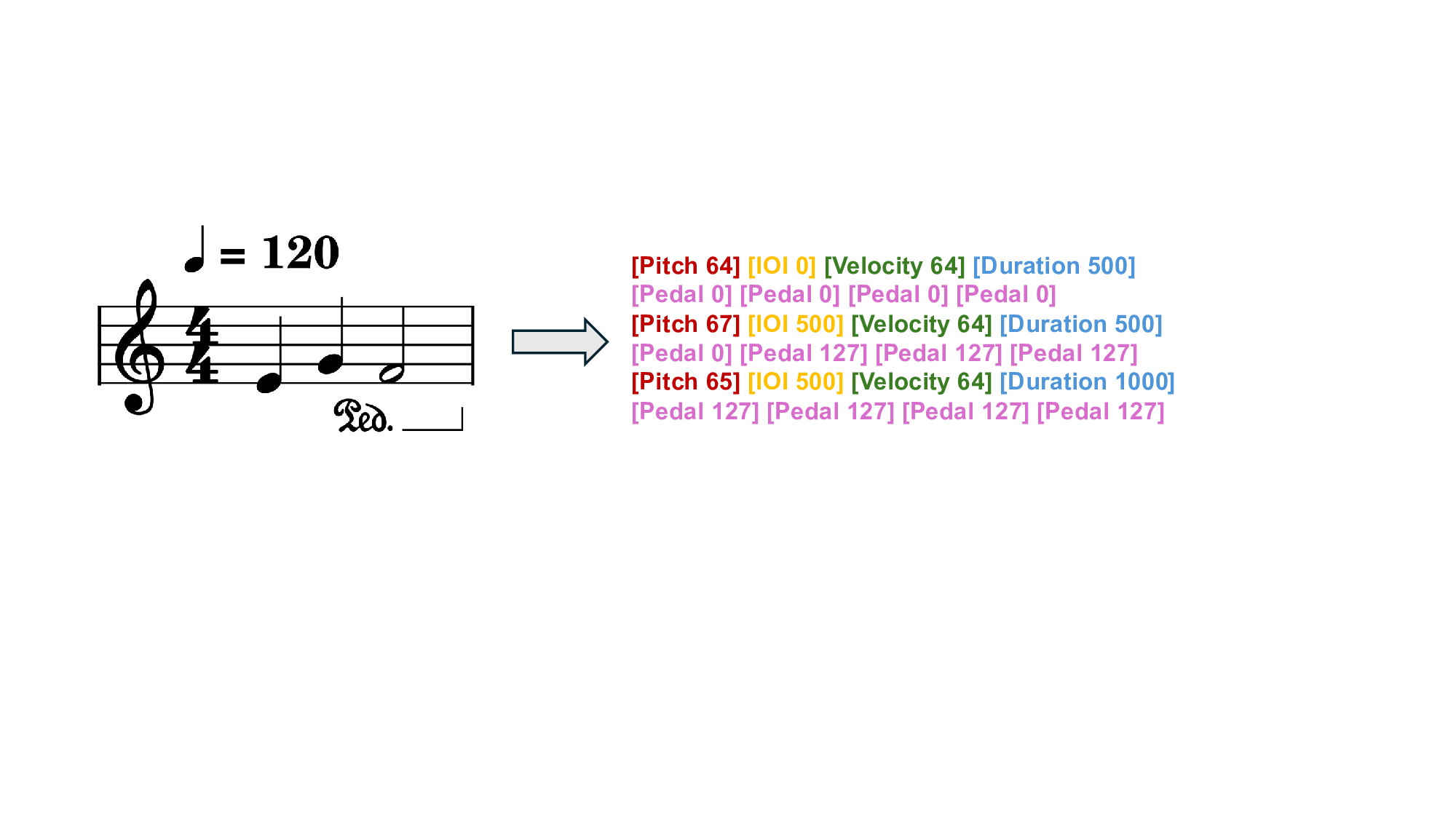

We represent each musical note as a sequence of eight tokens. This sequence captures the note’s Pitch, Velocity, Duration, and the Inter-Onset Interval (IOI) from the previous note, with timing information quantized from milliseconds. To model nuanced pedal control, we include four additional Pedal tokens, which represent the sustain pedal state at sampled points within the note’s IOI window.

Crucially, this representation, avoiding reliance on high-level musical concepts like measures or beats, unlocks large-scale pre-training on unaligned MIDI and empowers the model to uncover musical principles, from melodic contours to harmonic progressions, through statistical regularities.

We employ an Encoder-Decoder Transformer, but its standard O(N 2 ) self-attention complexity presents a critical bottleneck for long musical sequences, which often exceed thousands of tokens. To enable efficient rendering, we introduce two synergistic architectural modifications: Encoder Sequence Compression and an Asymmetric Layer Allocation.

Leveraging the fixed 8-token structure of each note, we compress the encoder’s input sequence. Instead of processing raw token embeddings, we first project and then aggregate the eight embeddings of a single note into one consolidated vector. This note-level aggregation reduces the sequence length by a factor of 8, which in turn leads to a 64-fold reduction in the self-attention computational cost from O(N 2 ) to O((N/8) 2 ). As a result, the encoder can efficiently process much longer sequence, capturing the global context essential for rendering.

Asymmetric Encoder-Decoder Architecture. We employ a deliberately asymmetric architecture with a deep 10-layer encoder with a lightweight 2-layer decoder (henceforth, 10-2) to maximize efficiency. This design, synergistic with our sequence compression, concentrates the majority of computation into a single, highly parallelizable encoding pass. This significantly accelerates training speed and reduces memory overhead for both training and inference. During generation, the shallow decoder, which is the primary bottleneck for autoregressive tasks, operates with minimal latency and memory footprint while being conditioned on the encoder’s powerful representation. This architecture represents a conscious trade-off between computational efficiency and model performance, a balance which we quantitatively analyze in our ablation studies in Section 4.5.

Our training paradigm directly addresses the core challenge of expressive rendering: modeling the complex dependency between a score’s musical structure and the nuances of human performance. To achieve this, our training proceeds in two stages: first, learning to comprehend musical context, and second, learning to translate that context into an expressive performance.

The initial pre-training stage builds an understanding of the implicit context guiding human expression.

We employ a self-supervised masked denoising objective on our massive, unlabeled MIDI corpus. By learning to reconstruct the original music pieces from their corrupted context, the model is compelled to internalize the deep structural cues such as harmonic function and melodic direction that inform performance choices.

The objective is to minimize the negative log-likelihood of the original tokens at the masked positions:

where M is the set of indices of the masked tokens, and p(x i |X corr , X <i ) is the probability of predicting the original token x i given the corrupted input and the ground-truth prefix X <i .

With a model that comprehends musical context, we then perform Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) to teach it how to translate this understanding into a performance. This stage learns the explicit mapping from the latent structural cues to the subtle, continuous parameters of human expression.

The SFT is framed as a sequence-to-sequence learning task on aligned score-performance pairs. The encoder processes the score’s token sequence, while the decoder is trained to autoregressively generate the corresponding performance sequence by minimizing a standard cross-entropy loss. This fine-tuning stage grounds the model’s expressive decisions, such as variations in timing and dynamics, in the deep musical understanding it acquired during pre-training.

A key challenge for practical application is that raw model outputs, with timings in absolute milliseconds, lack compatibility with standard music software. These performances do not align with the metrical grid of a Digital Audio Workstation (DAW), hindering editability. To bridge this gap between AI generation and modern music production workflows, we introduce a novel post-processing algorithm, Expressive Tempo Mapping.

This algorithm, detailed in Appendix B, intelligently translates the performance’s expressive timing deviations into a dynamic tempo map. It then realigns all note and pedal events to a musical grid governed by this new tempo curve. The process preserves the sonic nuance of the generated performance while restoring the structural alignment essential for editing and integration. The final output is a MIDI file that is both musically expressive and fully editable in any standard DAW.

We conduct a comprehensive set of experiments to evaluate our proposed Pianist Transformer. Our evaluation is guided by three central questions. First, to what extent does large-scale self-supervised pre-training contribute to the final performance of a rendering model? Second, how does Pianist Transformer perform against existing methods when judged by both objective metrics and subjective human evaluation? And third, what architectural choices influence the model’s effectiveness, and how robust is its performance across diverse musical contexts? The following sections are structured to address each of these questions in turn.

We pre-train our model on a massive 10-billion-token corpus aggregated from several public MIDI datasets. For supervised fine-tuning and evaluation, we use the ASAP dataset (Foscarin et al., 2020) with a strict piece-wise split. Our Pianist Transformer is compared against strong baselines, including VirtuosoNet-HAN (Jeong et al., 2019a), VirtuosoNet-ISGN (Jeong et al., 2019b) and ScorePerformer (Borovik & Viro, 2023), as well as the unexpressive Score MIDI and ground-truth Human performances.

We evaluate all models using a suite of objective and subjective measures. Objectively, we assess distributional similarity to human performances using Jensen-Shannon (JS) Divergence and Intersection Area across four key expressive dimensions: Velocity, Duration, IOI and Pedal. Subjectively, we conduct a comprehensive listening study to evaluate human-likeness and overall preference. Comprehensive details regarding the datasets, baseline implementations, and evaluation protocols are provided in Appendix A and Appendix C.

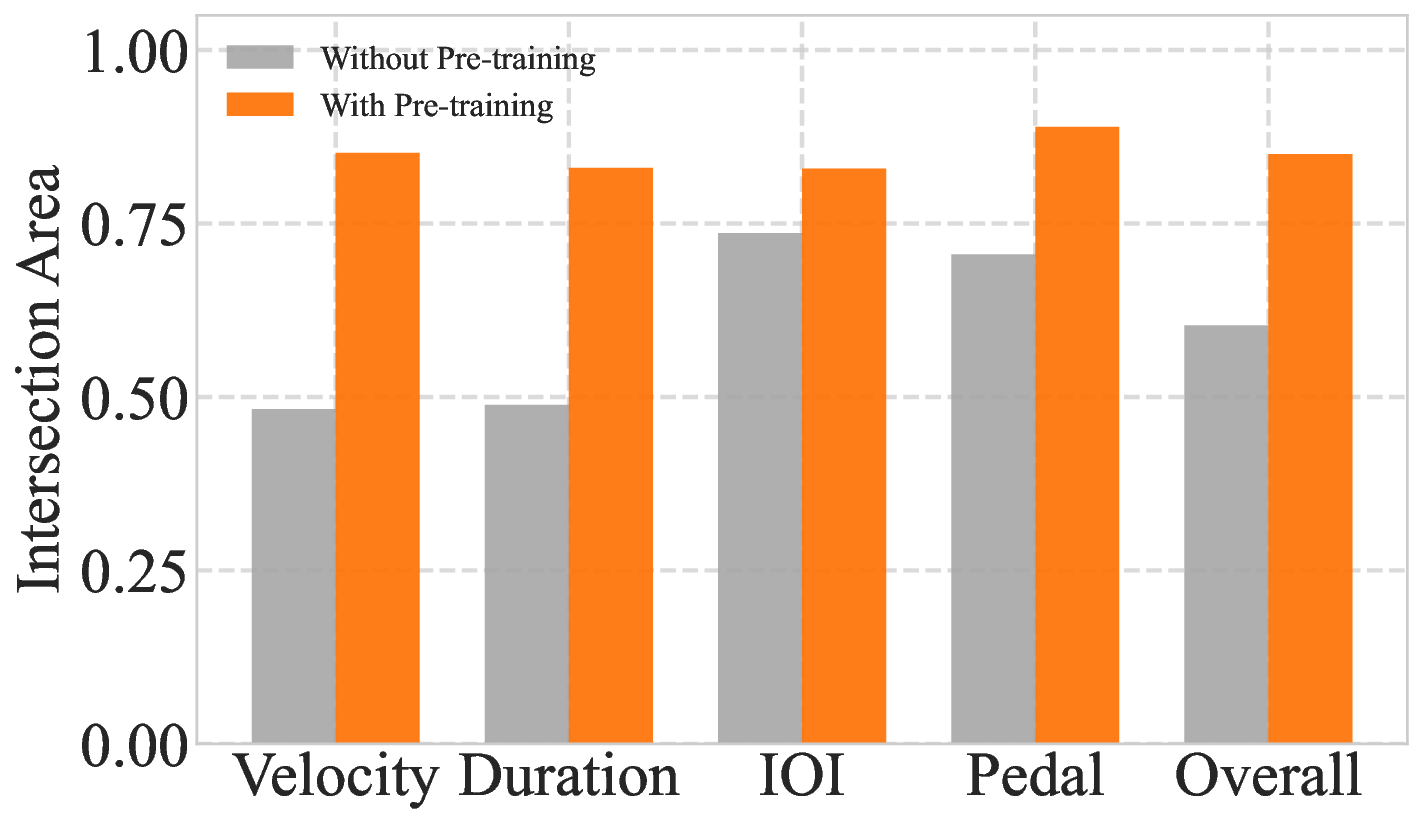

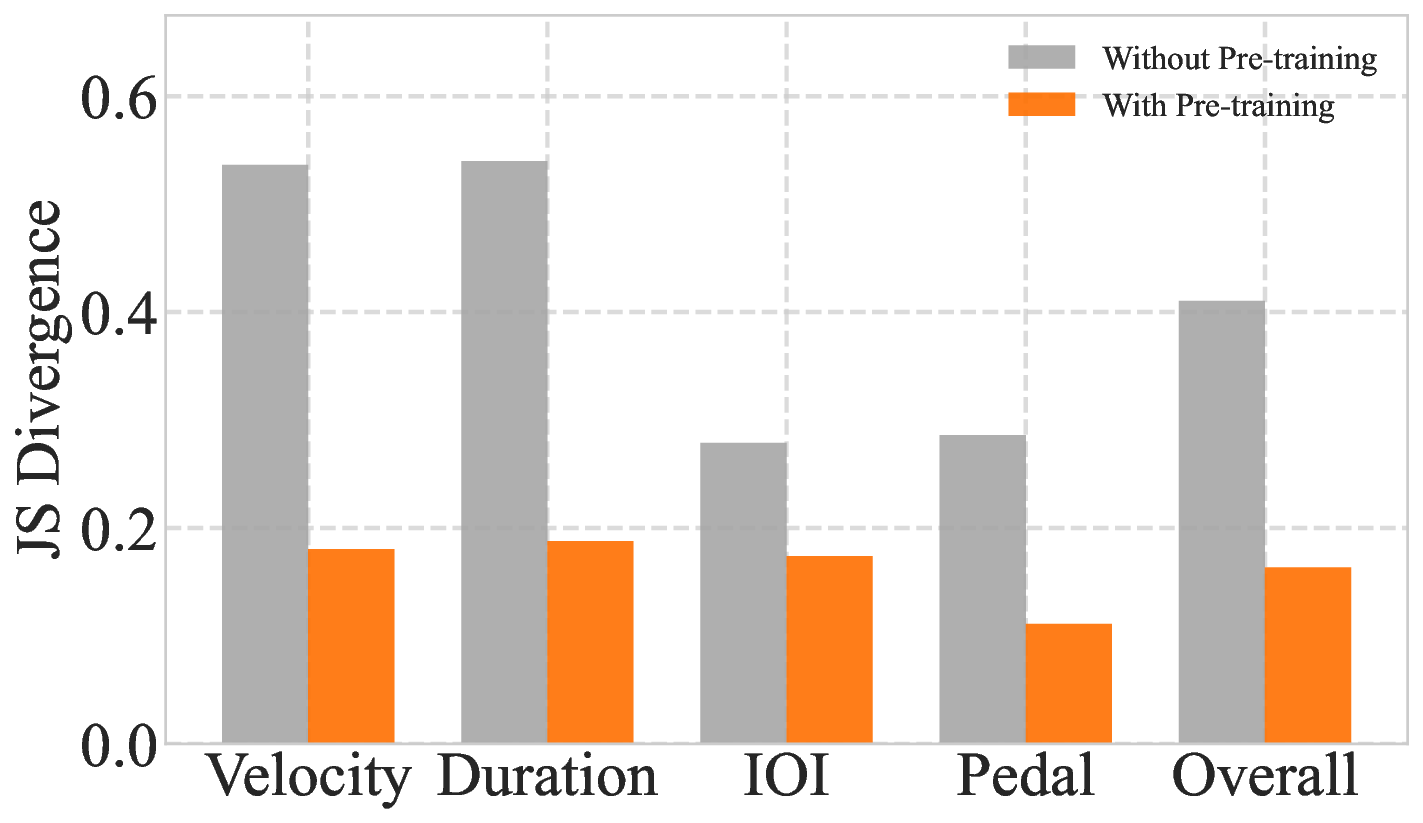

To quantify the impact of large-scale self-supervised pre-training, we perform a controlled ablation comparing our full Pianist Transformer with an identical model trained from scratch (w/o PT). This setup isolates the effect of pre-training and reveals its crucial role in expressive performance modeling. As shown in Figure 3, pre-training yields substantial improvements across both objective metrics and learning dynamics. Pre-training dramatically reduces JS Divergence and increases Intersection Area across all expressive dimensions (Figure 3a, 3b), indicating a significantly closer match to human performance distributions. The fine-tuning curves further reveal that the pre-trained model converges faster and reaches a much lower supervised loss, highlighting a superior initialization (Figure 3c). on limited supervised data struggles to capture the complex, high-variance distributions of human musicianship.

Together, these results validate that large-scale self-supervised pre-training is essential, as it provides the broad musical priors that limited supervised data alone cannot supply.

We now compare our full Pianist Transformer against prior state-of-the-art models. As shown in Table 1, our model demonstrates superior performance across the board.

Our model achieves the best scores among all generative models on 6 out of 8 metrics and on both overall average scores. Notably, Pianist Transformer significantly narrows the gap to the Human ground truth. For instance, its overall JS Divergence of 0.1634 represents a substantial improvement over the best baseline, VirtuosoNet-ISGN (0.2791). This indicates that the distributions of velocity, duration, and timing generated by our model are substantially more human-like than those from previous methods.

A closer look at the per-dimension results reveals our model’s strengths in modeling musical time. The most significant gains are in Duration and IOI, which govern the rhythmic and temporal feel of the music. Our model’s JS Divergence scores for these dimensions (0.1879 and 0.1740 respectively) are markedly lower than the best baseline scores. This suggests that large-scale pre-training endows the model with a sophisticated understanding of musical timing and phrasing, likely learned from the deep structural context in the data.

It is worth noting that VirtuosoNet-ISGN achieves a better score on the Pedal metrics, which may be attributed to its specialized architecture. However, our model still produces high-quality pedaling. Its JS Divergence of 0.1111 is competitive with the state-of-the-art (0.0829) and outperforms other baselines. This demonstrates that while not optimal in this specific dimension, our general-purpose pre-training approach yields strong all-around performance.

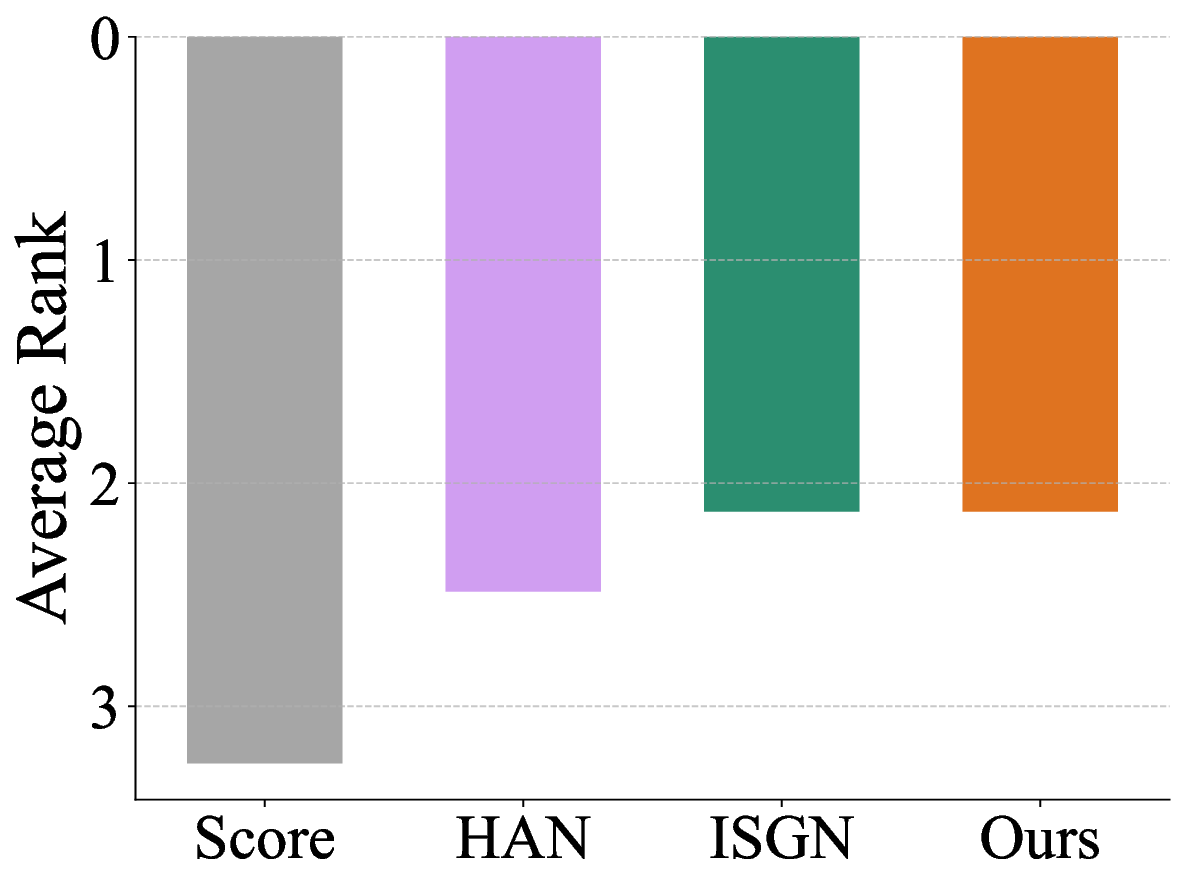

While objective metrics quantify statistical similarity, they often fail to capture the holistic qualities of a truly musical experience. We therefore conducted a comprehensive subjective listening study to perform a definitive, human-centric evaluation.

We designed a rigorous subjective listening study to ensure the reliability and impartiality of our findings. We recruited 57 participants from diverse musical backgrounds and retained 39 highquality responses after a stringent screening process based on attention checks and completion time.

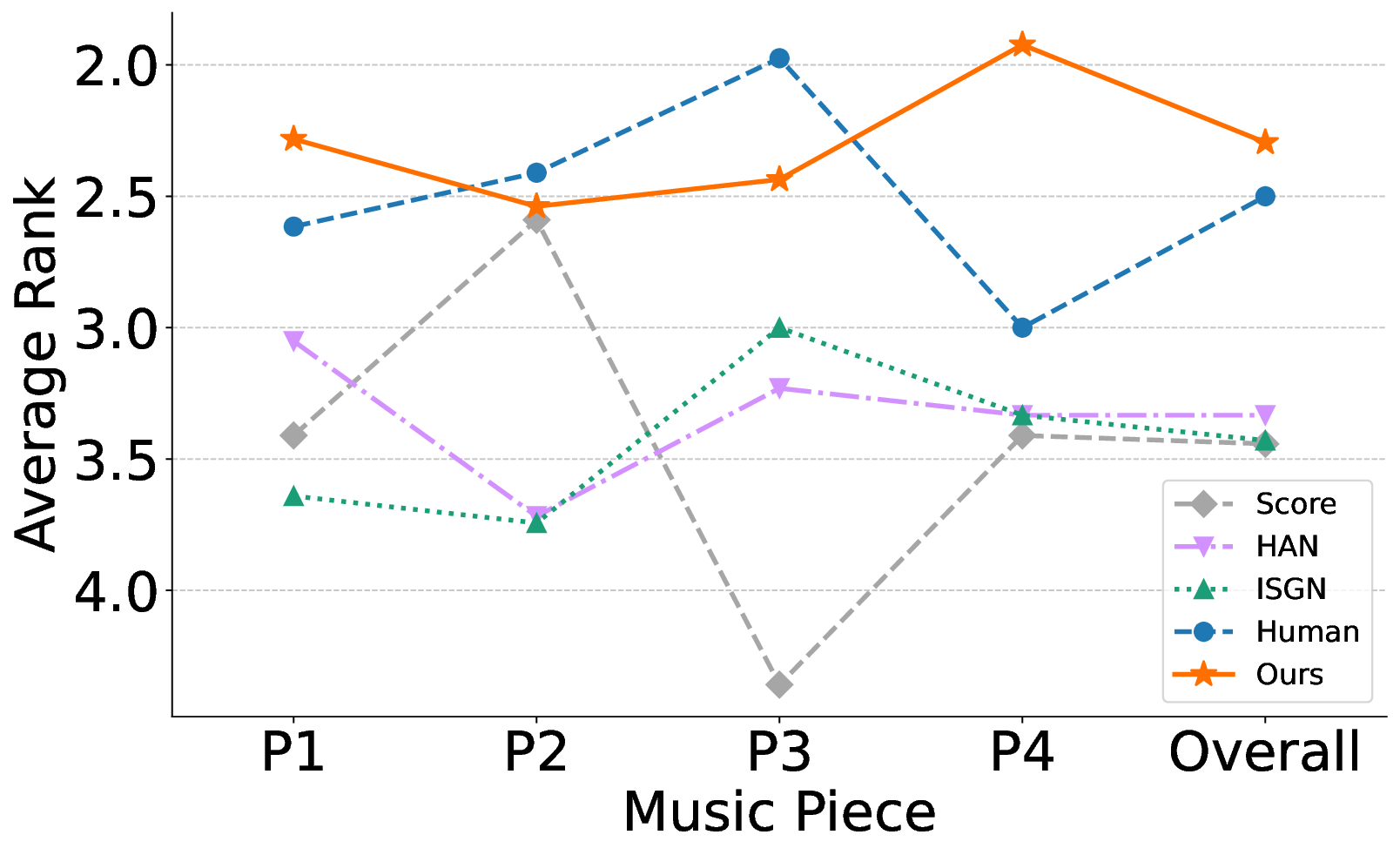

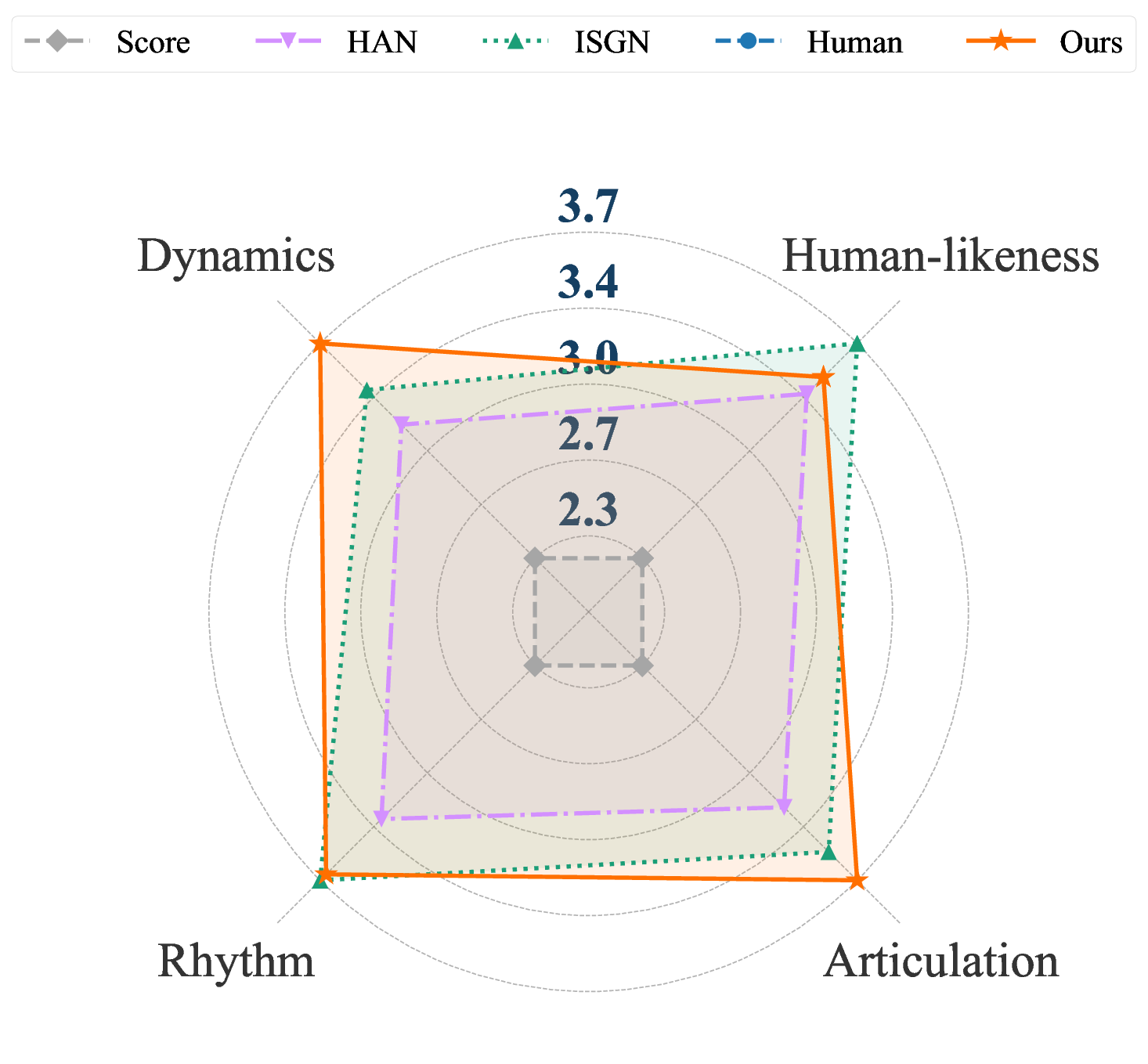

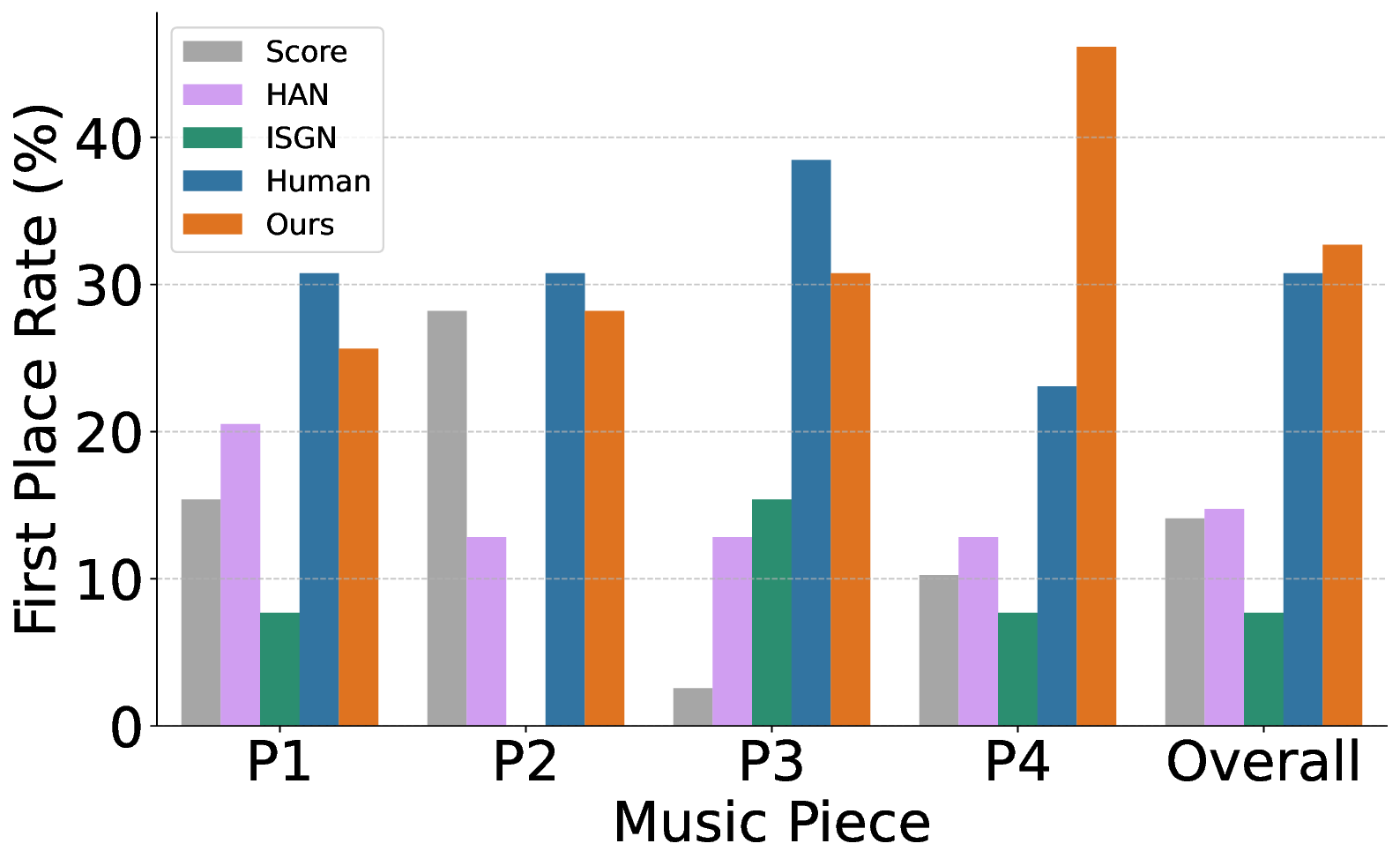

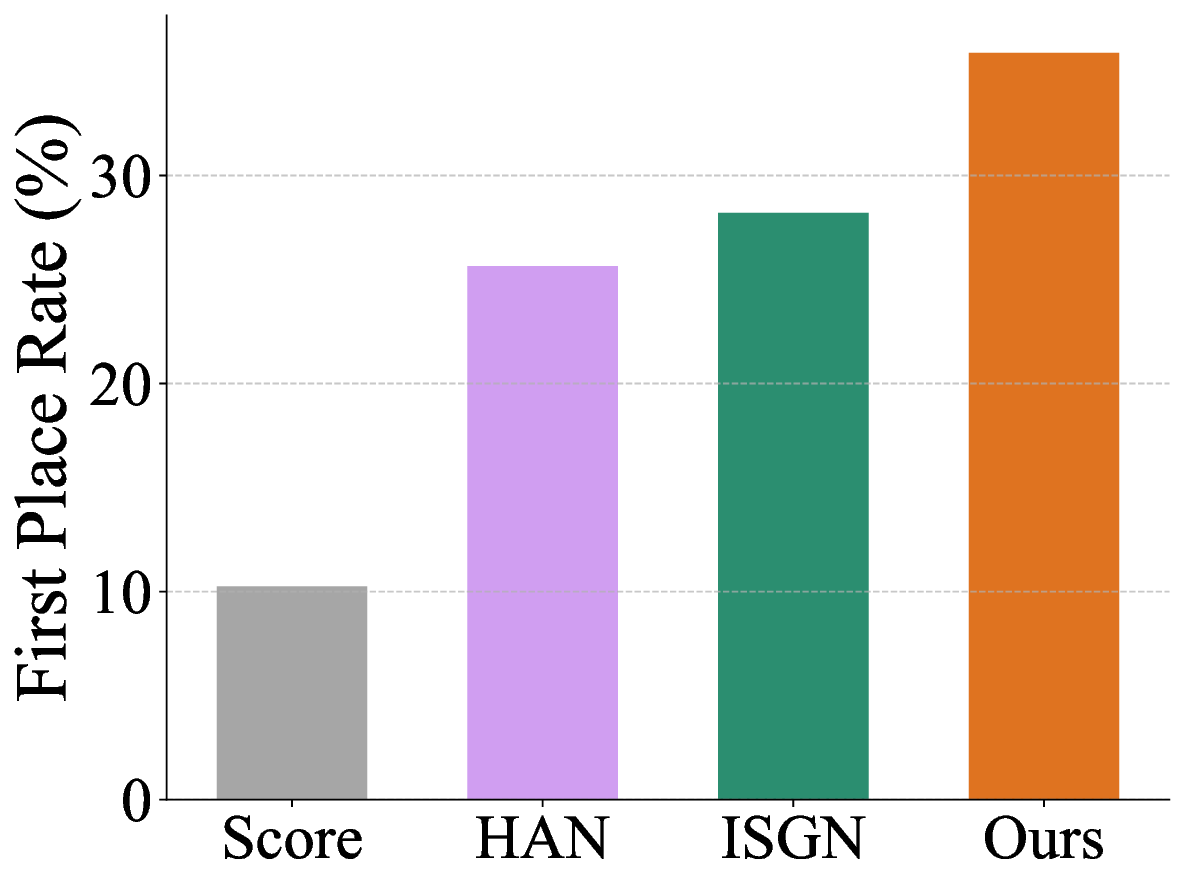

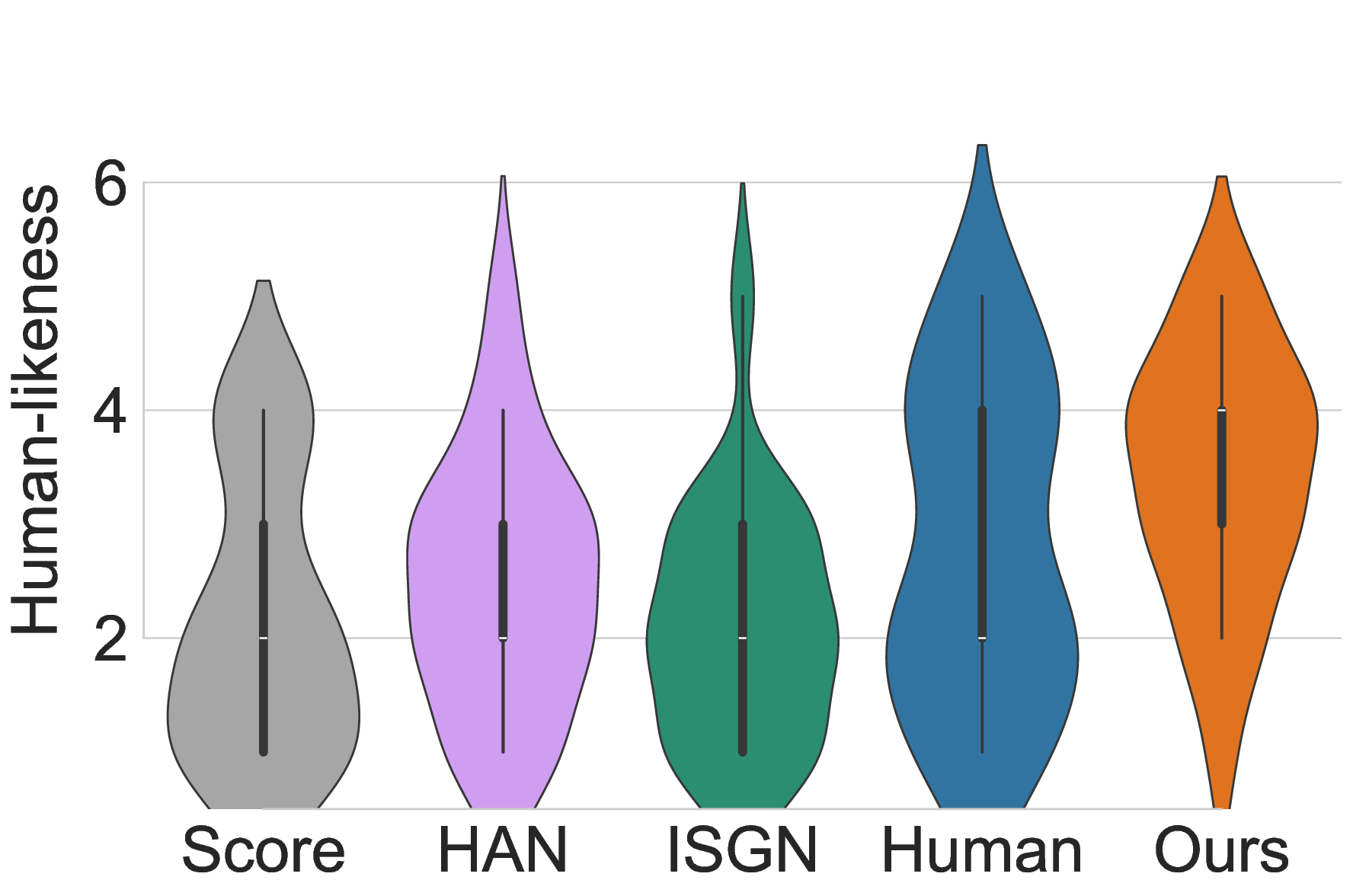

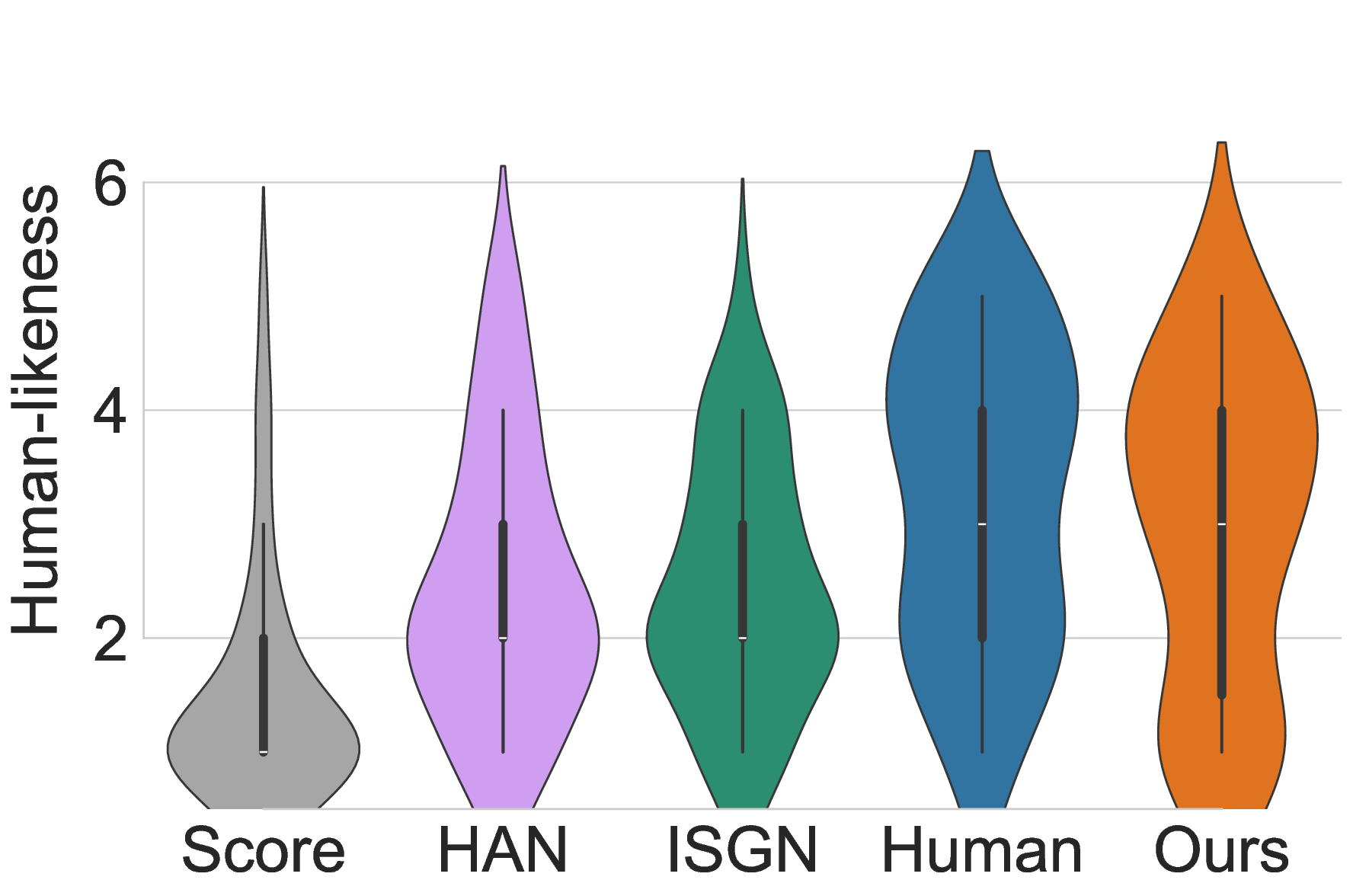

Participants rated and ranked five anonymized performance versions (our model, two baselines, Score, and Human) for six 15-second musical excerpts spanning Baroque to modern Pop styles. To mitigate bias, the presentation order of all performances was fully randomized for each participant. The listening study results, summarized in Figure 4, reveal a clear and consistent preference for Pianist Transformer. The most direct measure of quality is listener preference, and our model was consistently ranked as the best among all generative systems.

As shown in Figure 4b, the first-place vote rate for Pianist Transformer (32.7%) was not only substantially higher than that of the baselines (7.7% and 14.7%) but was even marginally higher than the human pianist’s (30.8%). This suggests that its renderings are not only realistic but also highly appealing to listeners. This trend is corroborated by the average ranking results (Figure 4a). Pianist Transformer achieved the best overall average rank (2.29), outperforming the human performance (2.50). To rigorously assess these differences, we conducted a series of two-sided paired t-tests. The results confirm that our model is rated significantly better than VirtuosoNet-ISGN (p < 0.001), VirtuosoNet-Han (p < 0.001), and the Score baseline (p < 0.001). While the observed advantage of our model over the Human performance was not found to be statistically significant (p = 0.21), this result provides strong evidence that our model has reached a level of quality that is not only on par with but also highly competitive against human artists.

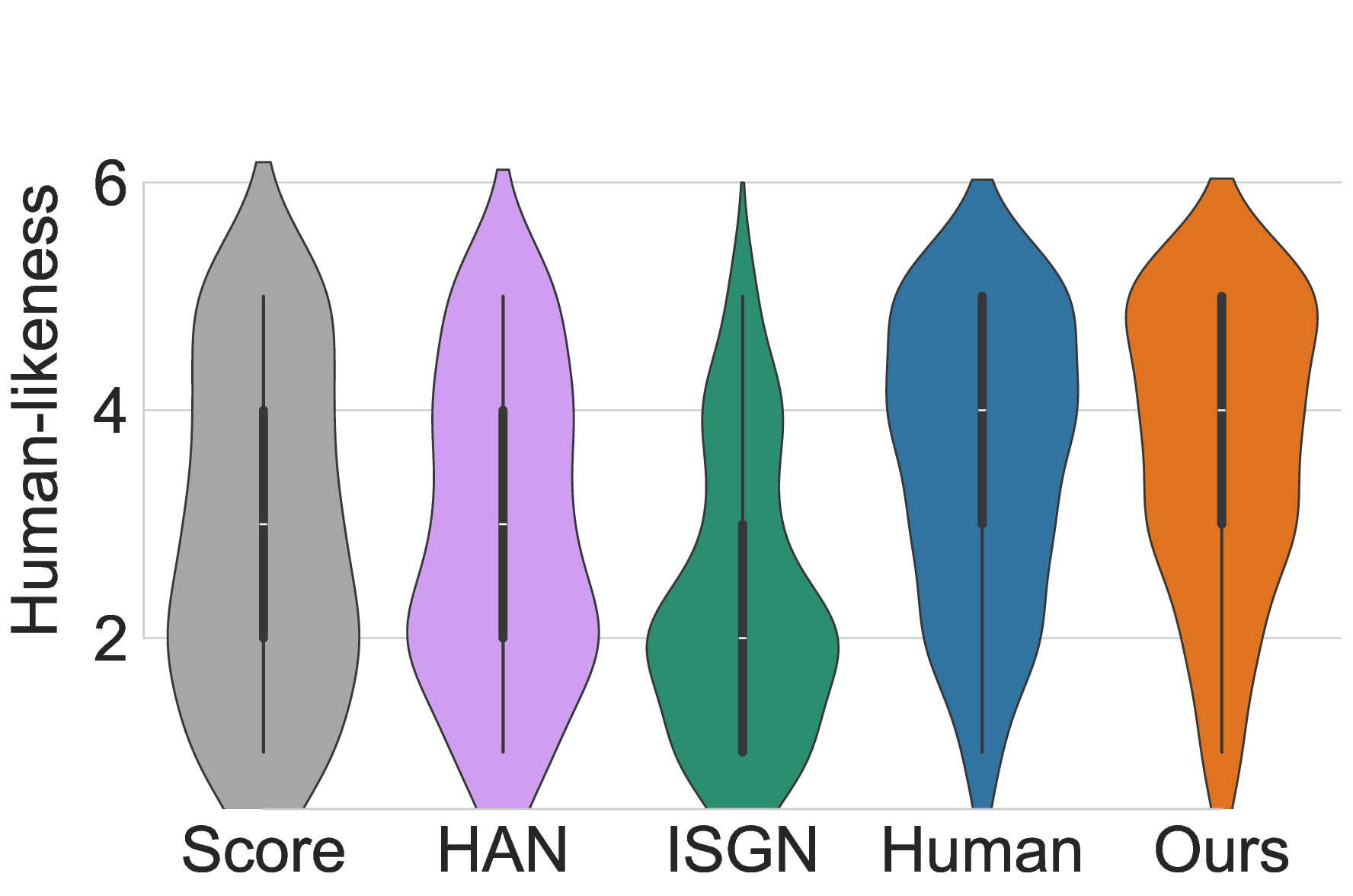

To understand the reasons behind this strong listener preference, we analyzed the multi-dimensional ratings and the model’s performance across different musical styles within our test pieces.

As visualized in the radar chart (Figure 5), the expressive profile of our Pianist Transformer closely mirrors that of the Human performance, indicating a well-balanced, high-quality rendering across all rated aspects. Quantitatively, our model’s average scores were rated higher than the human pianist’s not only in Rhythm & Timing (3.44 vs. 3.21) and Articulation (3.38 vs. 3.24), but also in the most critical global metric, . This remarkable result suggests our model generates performances that are perceived as human, perhaps even as idealized versions, free of the minor imperfections or idiosyncratic choices present in any single human recording. Furthermore, the benefits of pre-training are evident in the model’s stylistic robustness across historical periods, as shown in Figure 6. While baseline models exhibit a strong style dependency, with their performance degrading significantly for Baroque and Classical pieces, Pianist Transformer maintains a consistently high level of human-likeness across all styles, close to the human level. We attribute this robustness to the diverse musical knowledge acquired during large-scale pre-training, which prevents overfitting to the specific stylistic biases of the fine-tuning dataset. A case study on out-of-domain generalization to pop music is provided in Appendix C.3.

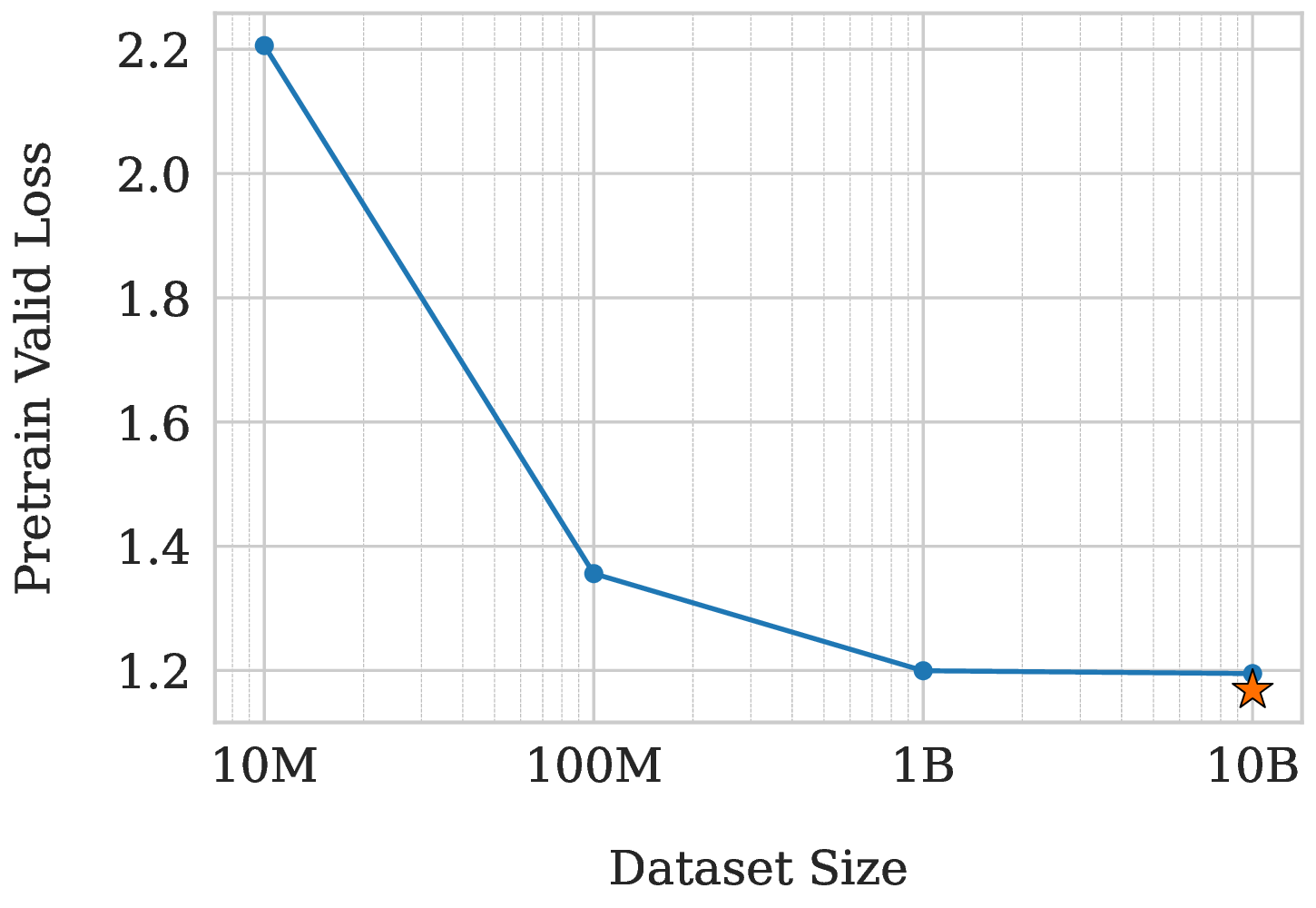

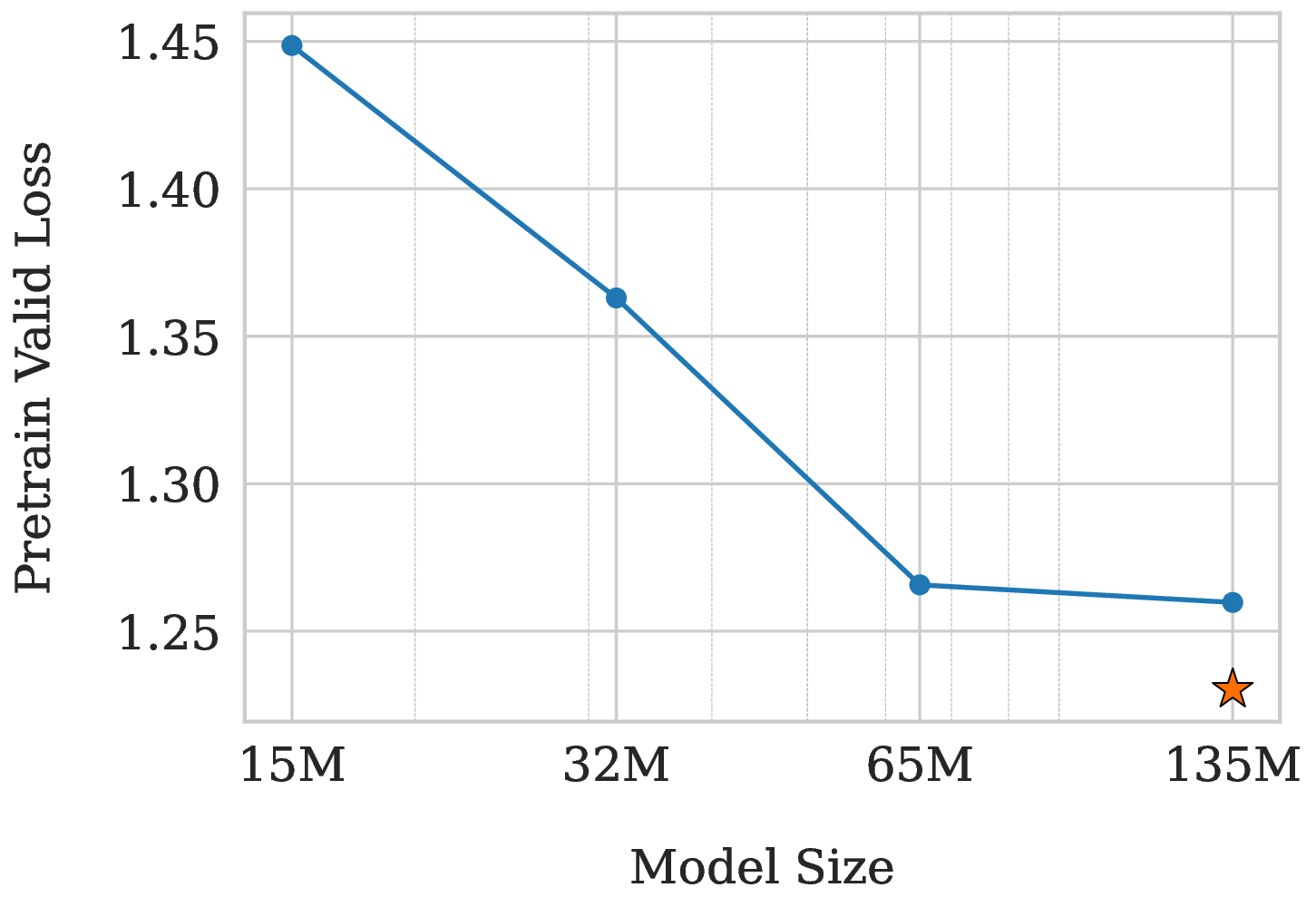

In our final analysis, we conduct a preliminary exploration of scaling effects to understand the relationship between performance, scale, and our architectural choices. The results, presented in Figure 7, validate that our framework is scalable while also revealing key bottlenecks that inform our design trade-offs.

We first analyze the effect of model size. As shown in Figure 7a, increasing model parameters from 15M to 65M yields substantial performance gains. However, the curve flattens significantly from 65M to 135M, indicating performance saturation. We hypothesized that this bottleneck stems from our lightweight 2-layer decoder. To test this, we trained a symmetric 6-layer encoder, 6-layer decoder (6-6) variant with a more powerful decoder (marked by a star). It achieved a notably lower loss of 1.230 compared to our 135M model’s 1.260, confirming that the shallow decoder is indeed the primary bottleneck for model capacity scaling. Data Scaling and Model Capacity Bottleneck. Next, we examine the impact of data scale. Figure 7b shows a dramatic drop in loss when scaling data up to 1B tokens. However, the performance again saturates when increasing the data tenfold to 10B (1.199 vs. 1.195). To determine if this was also a decoder issue, we leveraged our more powerful 6-6 model. Even with this stronger architecture, the loss on 10B data only marginally decreased to 1.168. This suggests that for a massive 10B-token dataset, the overall model capacity (around 135M parameters) itself becomes the primary bottleneck, regardless of the encoder-decoder layer allocation.

Architectural Trade-off. While the symmetric 6-6 model achieved a lower pre-training loss, confirming that the shallow decoder is a capacity bottleneck, our detailed evaluation in Appendix F reveals that this advantage did not translate to superior downstream performance. This suggests that fully capitalizing on the deeper decoder’s potential may require more extensive training or data scaling than currently employed. Consequently, we prioritized the asymmetric 10-2 architecture. As demonstrated in the efficiency analysis in Table 10, the 10-2 model delivers comparable rendering quality while being approximately 2.1x faster during CPU inference, representing a far more practical trade-off for real-world applications.

In this work, we introduced Pianist Transformer, establishing a new state-of-the-art in expressive piano performance rendering through large-scale self-supervised pre-training. By learning from a 10-billiontoken MIDI corpus with a unified representation, our model overcomes the data scarcity that has hindered prior methods from learning the complex mapping between musical structure and expression. Our experiments provide compelling evidence for this paradigm shift: Pianist Transformer not only excels on objective metrics but achieves a quality level statistically indistinguishable from human artists in subjective evaluations, where its renderings were sometimes preferred. Furthermore, our model demonstrates robust performance across diverse musical styles, a direct benefit of its pre-trained foundation. Ultimately, Pianist Transformer demonstrates that scaling self-supervised learning is a promising path toward generating music with genuine human-level artistry, establishing an effective and scalable paradigm for future research in computational music performance.

While Pianist Transformer demonstrates strong performance, it has several limitations that suggest future directions. First, our efficient lightweight decoder is a performance bottleneck for scaling, motivating research into more powerful yet efficient decoder architectures. Second, our focus on solo piano invites extending our self-supervised paradigm to multi-instrument and orchestral settings. Finally, moving beyond the limitation of score-based rendering to controllable generation from intuitive inputs like natural language remains a promising frontier.

The pre-training corpus is constructed from the following sources. We applied specific preprocessing steps to ensure data quality and diversity.

• Aria-MIDI (Bradshaw & Colton, 2025): A large collection of over 1.1 million MIDI files transcribed from solo piano recordings. To ensure high fidelity, we only included segments with a transcription quality score above 0.95. Due to the coarse quantization in the original transcriptions, we applied random augmentations to the Velocity, Duration, and IOI values of these files to better simulate performance nuances.

• GiantMIDI-Piano (Kong et al., 2022): A dataset of over 10,000 unique classical piano works transcribed from live human performances using a high-resolution system. These files retain fine-grained expressive details, including velocity, timing, and pedal events.

• PDMX (Long et al., 2025): A diverse dataset of over 250,000 musical scores, originally in MusicXML format. We used their MIDI conversions to provide our model with clean, score-based MIDI data.

To filter out overly simplistic or empty files, we only included MIDI files larger than 7 KB.

• POP909 (Wang et al., 2020): A dataset of 909 popular songs. We extracted the piano accompaniment tracks to include non-classical and accompaniment-style patterns.

• Pianist8 (Chou et al., 2021): A collection of 411 pieces from 8 distinct artists, consisting of audio recordings paired with machine-transcribed MIDI files.

For SFT and evaluation, we use the ASAP dataset (Foscarin et al., 2020), a collection of aligned score-performance pairs of classical piano music.

Before training, we first normalize all MIDI files so they can be tokenized under a consistent format. For multi-track scores, we merge all tracks into a single time-ordered event stream and remove duplicate notes created during merging. We also convert every file to a fixed tempo of 120 BPM and rescale all onset times and durations. After this processing, all MIDI files share the same temporal scale and event structure, allowing reliable and uniform tokenization across the entire corpus.

To ensure precise note-level correspondence between scores and performances, we refined the provided alignments. We first employed an HMM-based note alignment tool (Nakamura et al., 2017) to establish a direct mapping for each note. For localized mismatches where a few notes could not be paired, we applied an interpolation algorithm to infer the correct alignment based on the surrounding context. Finally, segments with large, contiguous blocks of unaligned notes were filtered out and excluded from our training and evaluation sets to maintain high data quality. We create a strict piece-wise split by randomly holding out 10% of the pieces for our test set. The remaining 90% are used for fine-tuning.

A.2.1. MODEL ARCHITECTURE Our Pianist Transformer employs an asymmetric encoder-decoder architecture based on the T5-Gemma framework (Zhang et al., 2025). The encoder is designed to be substantially deeper than the decoder, with 10 layers, to efficiently process long input sequences and build a rich contextual representation. The decoder, with only 2 layers, is lightweight to ensure fast and efficient autoregressive generation during inference. This design strikes a balance between expressive power and practical utility. Key hyperparameters for our 135M model are detailed in Table 2.

A.2.2. UNIFIED MIDI REPRESENTATION Central to our approach is a unified, event-based token representation that treats both score and performance MIDI identically. Each musical note is represented as a fixed-length sequence of eight tokens, capturing its core attributes and nuanced pedal information. The sequence order is: [Pitch, IOI, Velocity, Duration, Pedal1, Pedal2, Pedal3, Pedal4].

The vocabulary is structured as follows: • Pitch: MIDI pitch values are mapped directly to 128 tokens (range 0 to 127).

• Velocity: MIDI velocity values are mapped to 128 tokens (range 0 to 127).

• Timing (IOI & Duration): The Inter-Onset Interval (IOI) and Duration are quantized at a 1ms resolution and share a common vocabulary of 5000 tokens. The Duration can utilize the full range (0 to 4999), while the IOI is restricted to a slightly smaller range (0 to 4990) to avoid a known artifact in transcribed MIDI where durations frequently saturate at the maximum value.

• Pedal: Four pedal tokens represent the sustain pedal state sampled at four equidistant points within the interval leading to the next note. 3 provides a comparison between our MIDI representation and several prior tokenization schemes. The design of our representation is guided by the specific requirements of the expressive performance rendering task, particularly the need to leverage large-scale MIDI data without structural features.

The core advantages of our representation are as follows:

• Unlocks Self-Supervised Pre-training. By using time shift for temporal representation, our method does not require structural features like bars or beats. This is a crucial advantage because it allows us to pre-train on massive datasets of performance MIDI, which lack this structure and thus cannot be used by other methods. set. For Velocity, Duration, and IOI, we aggregate the tokens of each type from all generated pieces and compute their distributions, which we then compare with the corresponding human distributions using JS Divergence and Intersection Area. For Pedal, where the corpus mainly contains binary values, we binarize both model outputs and human data and evaluate the distribution of the 16 possible joint configurations formed by the four pedal tokens of each note.

To obtain a human baseline, for every piece, we treat one human performance as the candidate and use the remaining human performances as the reference set, applying the same distributional comparison. This provides a measure of the natural stylistic variation among human performers.

For VirtuosoNet-HAN and VirtuosoNet-ISGN, we used the official implementations and pre-trained weights, followed their recommended inference procedures, and selected the composer-style configurations that best matched the pieces in our test set.

ScorePerformer was evaluated under the same score-only setting. Since it is designed to operate with fine-grained style vectors derived from reference performances, which are not available in our setup, we adopted the unconditional generation mode recommended in the original paper, where style vectors are sampled from the prior distribution.

All generated MIDI files from all models were rendered to audio using the same high-quality piano soundfont to ensure a fair subjective listening study.

To make our model’s output compatible with standard music production software, we introduce the Expressive Tempo Mapping algorithm. This process converts the generated performance, which has timing in absolute milliseconds, into a standard MIDI file where expressive timing is encoded as a dynamic tempo map. This makes the performance fully editable within any DAW. The procedure is outlined in Algorithm 1. -pitch is from pitch of n score 9:

-velocity is from velocity of n per f 10:

-onset in ticks is converted from n per f ’s onset in milliseconds using T changes .

11:

-duration in ticks is converted from n per f ’s duration in milliseconds using T changes .

12:

Append n new to N aligned . 13: end for 14: for each control event cc in CC per f do 15: Convert cc’s timestamp from milliseconds to ticks using T changes to get t new .

Create a new control event cc new with value from cc and time from t new . 17:

Append cc new to CC aligned . 18: end for 19: Assemble M DAW by combining T changes , N aligned , and CC aligned . 20: return M DAW The algorithm executes in three main stages:

-

Tempo Estimation (Line 4): First, we compare the timing of note onsets between the score MIDI (M score ) and the generated performance MIDI (M perf ). The differences in timing are used to calculate a local tempo (BPM) for each segment of the piece. This sequence of tempo changes forms a dynamic tempo curve, T changes , which captures all the expressive timing (rubato) of the performance.

-

Event Remapping (Lines 6-18): Next, we create a new set of notes and pedal events. Each new note uses the pitch from the original score and the velocity from the generated performance. The crucial step is converting the onset time and duration of every note and pedal event from absolute milliseconds into musical ticks. This conversion is done using the tempo curve T changes estimated in the previous step. This aligns all events to a musical grid while preserving their expressive timing.

Finally, the newly created tempo curve (T changes ), the remapped notes (N aligned ), and the remapped pedal events (CC aligned ) are combined into a single, standard MIDI file (M DAW ). The resulting file sounds identical to the original performance but is now fully editable in a DAW, with all timing nuances represented in the tempo track.

To conduct a definitive, human-centric evaluation of our model’s performance, we designed and carried out a comprehensive subjective listening study. This appendix provides a detailed account of the study’s design, participants, materials, and procedures.

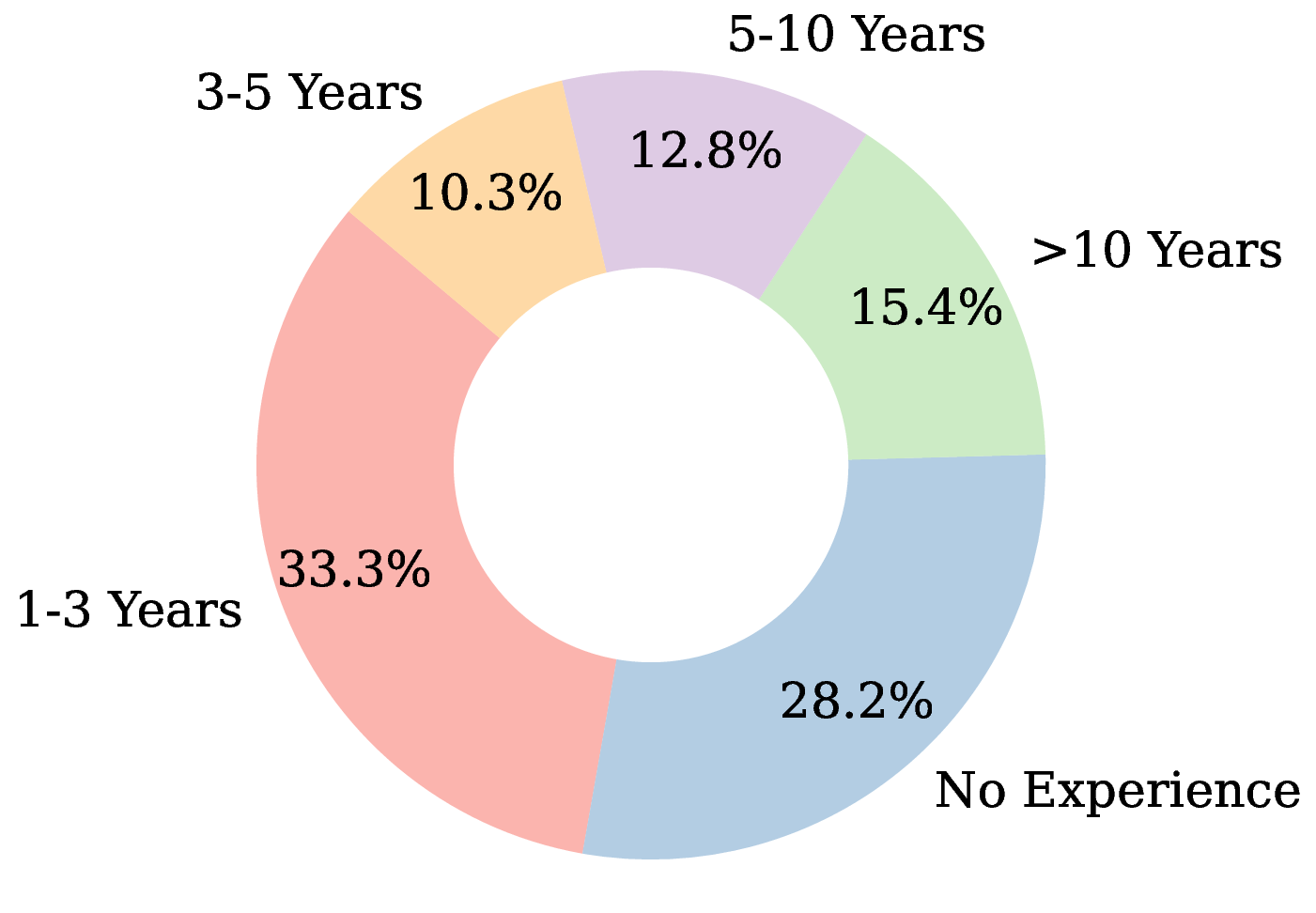

Our subjective listening study’s validity rests on the quality and diversity of its participant pool. We initially recruited 57 individuals; after a rigorous screening for attentiveness and completion quality, 39 responses were retained for the final analysis. This section details the demographic composition of this group, providing evidence for its suitability for the nuanced task of evaluating musical expression.

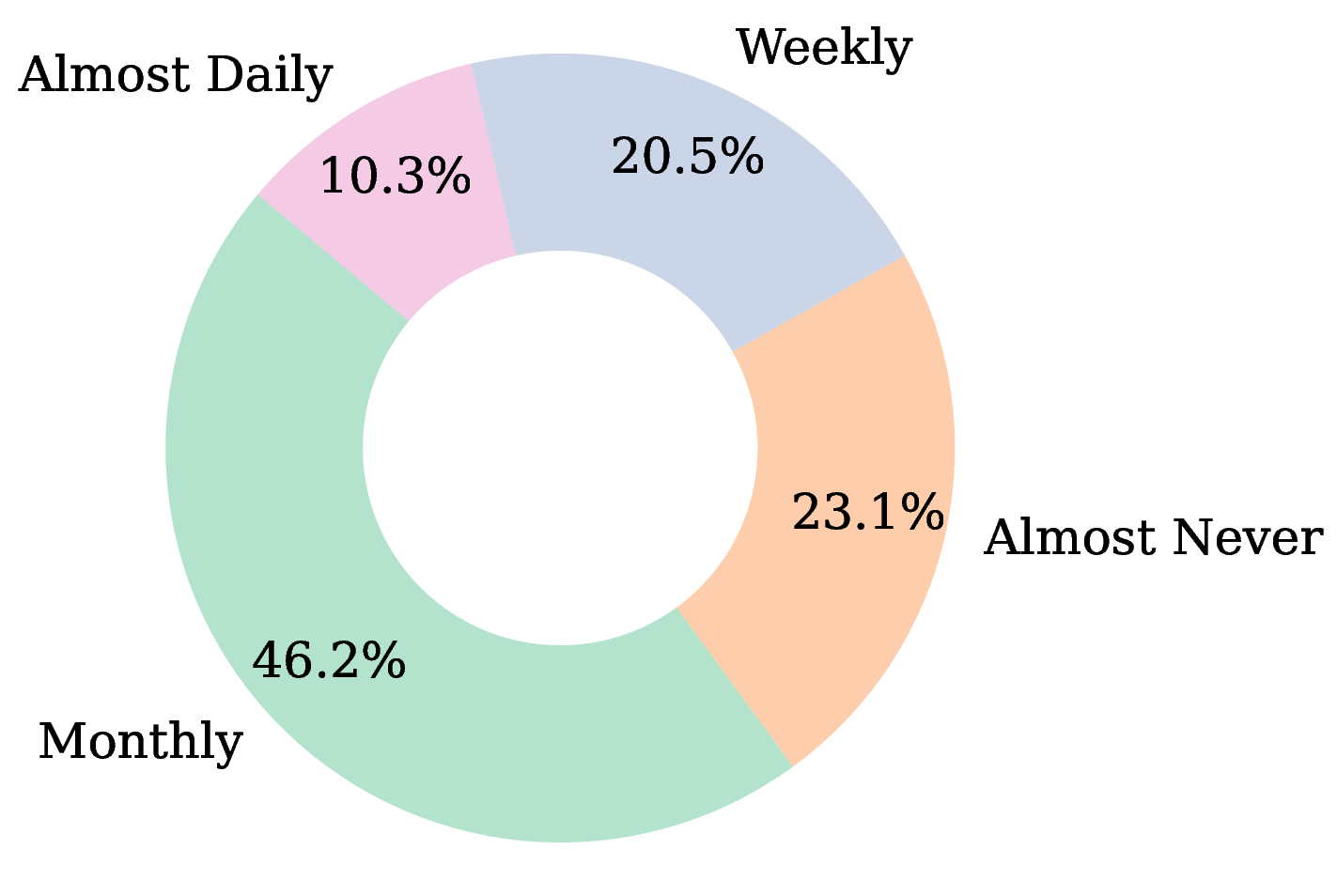

The detailed distributions of participants’ musical experience and listening habits are visualized in Figure 9. Several key characteristics of the group bolster the credibility of our findings:

Balanced Expertise Spectrum (Figure 9a). The participants’ formal music training is not skewed towards one extreme. The pool includes a substantial proportion of listeners with no formal training (28.2%), ensuring that our model’s appeal is not limited to musically educated ears. Concurrently, the presence of highly experienced individuals (15.4% with > 10 years of training) guarantees that subtle expressive details are also being critically evaluated. This heterogeneity mitigates potential bias and strengthens the generalizability of our preference results.

Representative Listening Habits (Figure 9b). The distribution of classical piano listening frequency reflects a general audience rather than a niche group of connoisseurs. The largest segment listens “Monthly” (46.2%), suggesting that the superior performance of Pianist Transformer is perceptible and appreciated even by those who are not deeply immersed in the genre daily.

Competent and Calibrated Self-Assessment (Figure 9c). The self-assessed ability to discern music quality is centered around “Moderate” (46.2%), with a healthy portion rating themselves as “High” (20.5%). This distribution suggests a group that is confident in their judgments without being overconfident, indicating that the participants were well-suited for the evaluation task.

In summary, the participant pool is intentionally diverse, comprising a mix of novices, enthusiasts, and experts. This composition ensures that our findings are robust, reliable, and reflective of a broad range of listener perceptions.

The results indicate that our main setting of 30% outperforms the 15% ratio, while the 45% ratio yields slightly better overall performance. This suggests that the optimal masking strategy for symbolic music may differ from common practices in NLP, an interesting direction for future work.

However, all three pre-trained models significantly outperform the supervised-only baselines, showing that the gains from self-supervised pre-training do not depend on any specific masking setting.

To investigate how our efficiency-related components influence the overall training efficiency, we conduct a detailed analysis of note-level sequence compression and the asymmetric architecture. Each component individually reduces computational cost, but their combination leads to a substantially larger improvement than using either one alone.

Table 8: Synergistic Efficiency Analysis of Sequence and the Asymmetric Architecture. We report relative metrics where the baseline (6-6, Uncompressed) is set to 1.00x. Lower is better for VRAM, higher is better for Speed. As shown in table 8, compression accelerates training by 1.81× on the 6-6 architecture, and the 10-2 architecture improves speed by 1.07× without compression. However, when both components are applied together, the overall training speed reaches 3.13×, substantially exceeding the product of their individual gains. A similar synergistic effect appears in VRAM reduction, where compression and architectural asymmetry jointly amplify memory savings.

These findings confirm that the proposed efficiency components are not merely additive but interact in a way that significantly amplifies their benefits, effectively achieving a “1 + 1 > 2” efficiency outcome.

We chose an asymmetric 10-2 architecture to balance performance and efficiency. To validate this choice, we compare it against a symmetric 6-6 baseline with a similar parameter count.

Table 9 shows the final rendering performance of both models after fine-tuning. While the symmetric 6-6 model achieves a slightly lower loss during pre-training, this does not translate to superior performance on the downstream rendering task. Our 10-2 model performs comparably to the 6-6 variant.

While the final rendering quality is highly comparable between the two architectures, the choice is justified by the significant gains in computational efficiency, detailed in In conclusion, our asymmetric 10-2 architecture provides a superior trade-off, delivering state-of-the-art rendering quality while being significantly more efficient for both training and deployment. This makes it a more practical solution.

During inference, our goal is to generate expressive performances that remain strictly matched to the input score. To preserve the note-level correspondence, we apply a hard pitch constraint: the model is free to sample expressive attributes but whenever a Pitch token is expected, we directly set it to the pitch from the input score instead of sampling. This enforces a one-to-one mapping between score notes and generated performance notes.

Table 1 further reinforce this gap. The overall Intersection Area improves from 0.6032 (scratch) to 0.8501 (pre-trained), representing a 40.9% relative gain. Pre-training also yields large reductions in JS Divergence for velocity (66.3%), duration (65.2%), IOI (37.6%), and pedal (61.2%). These consistent improvements across all expressive dimensions indicate that a model trained solely

1: Input:

📸 Image Gallery