Process-Centric Analysis of Agentic Software Systems

📝 Original Info

- Title: Process-Centric Analysis of Agentic Software Systems

- ArXiv ID: 2512.02393

- Date: 2025-12-02

- Authors: Shuyang Liu, Yang Chen, Rahul Krishna, Saurabh Sinha, Jatin Ganhotra, Reyhan Jabbarvand

📝 Abstract

Agentic systems are modern software systems: they consist of orchestrated modules, expose interfaces, and are deployed in software pipelines. Unlike conventional programs, their execution, i.e., trajectories, is inherently stochastic and adaptive to the problem they are solving. Evaluation of such systems is often outcome-centric, i.e., judging their performance based on success or failure at the final step. This narrow focus overlooks detailed insights about such systems, failing to explain how agents reason, plan, act, or change their strategies over time. Inspired by the structured representation of conventional software systems as graphs, we introduce Graphectory to systematically encode the temporal and semantic relations in such software systems. Graphectory facilitates the design of process-centric metrics and analyses to assess the quality of agentic workflows independent of final success. Using Graphectory, we analyze 4000 trajectories of two dominant agentic programming workflows, namely SWE-agent and OpenHands, with a combination of four backbone Large Language Models (LLMs), attempting to resolve SWE-bench Verified issues. Our fully automated analyses reveal that: (1) agents using richer prompts or stronger LLMs exhibit more complex Graphectory, reflecting deeper exploration, broader context gathering, and more thorough validation before patch submission; (2) agents' problem-solving strategies vary with both problem difficulty and the underlying LLM-for resolved issues, the strategies often follow coherent localization-patching-validation steps, while unresolved ones exhibit chaotic, repetitive, or backtracking behaviors; (3) even when successful, agentic programming systems often display inefficient processes, leading to unnecessarily prolonged trajectories.📄 Full Content

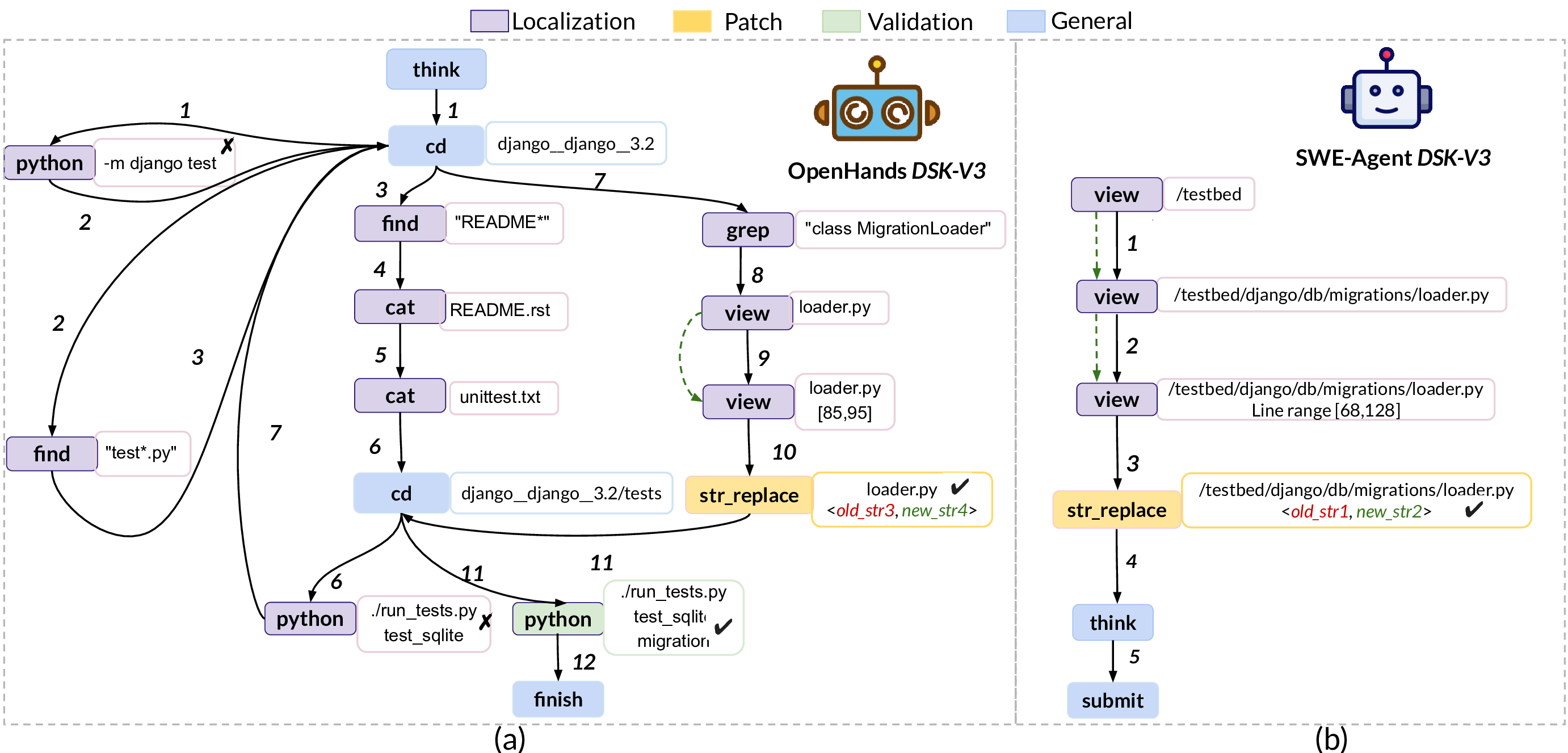

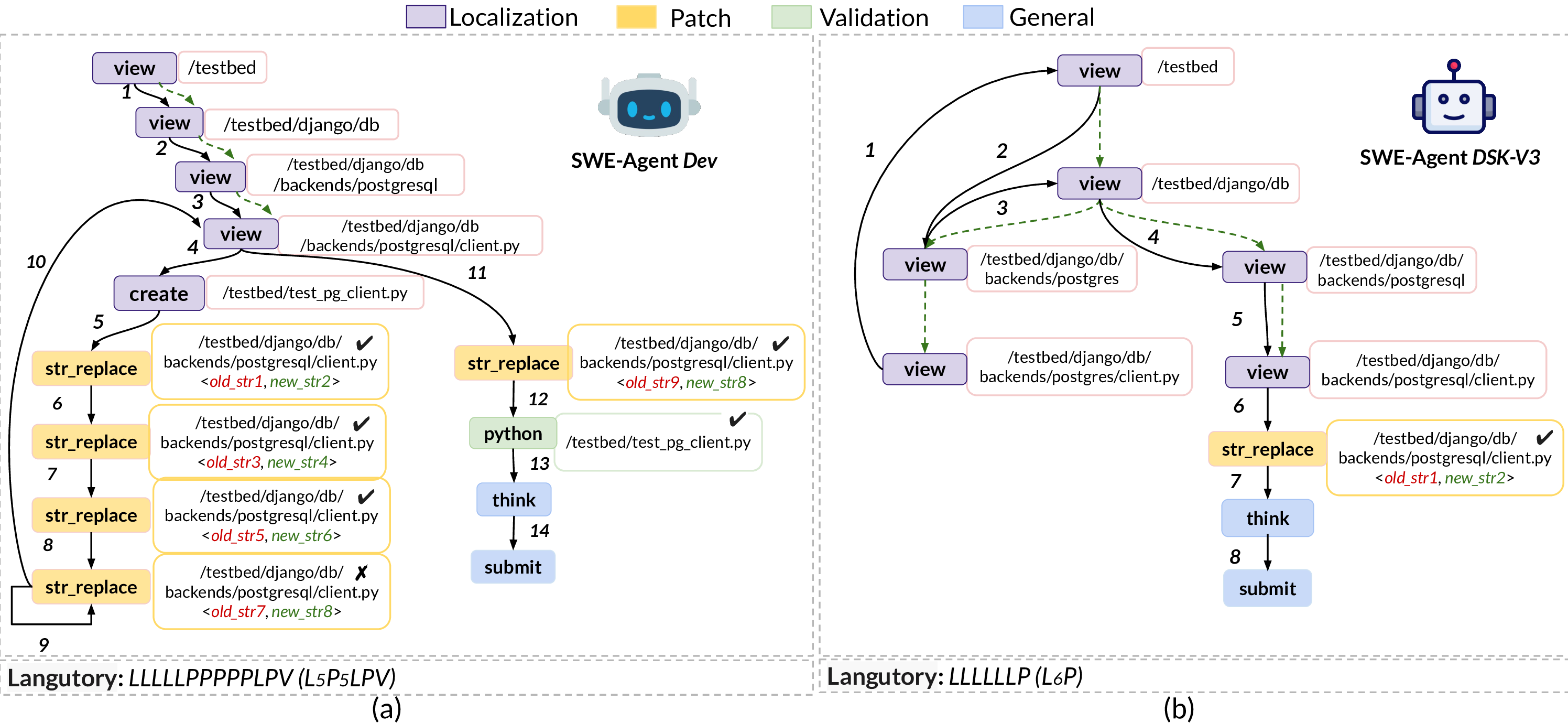

An outcome-centric evaluation overlooks the intermediate steps that lead there, masking recurrent inefficiencies and preventing us from understanding whether success came from systematic reasoning or by chance. For example, consider the trajectory traces of SWE-agent [54] with Devstral-Small (Figure 1-a) and DeepSeek-V3 (Figure 1-b) for repairing the issue django-10973 in SWE-bench [22]. From an outcome-centric perspective, both agents, SWE-agent Dev and SWE-agent thought: we should replace this with subprocess.run and pass PGPASSWORD directly in the environment. i.e., the sequence of reasoning about how to solve the problem and taking the appropriate actions, are different: SWE-agent Dev starts by localizing the bug to client.py file (steps 1-4), creating a reproduction test (step 5), and editing multiple locations of the client.py (steps 6-8). After two additional repetitive failed edits (step 9-10), it re-views and edits a different block of client.py file (steps 11 and 12), executes the previously created reproduction test (step 13) to validate the patch, and concludes with patch submission (steps 14-15). SWE-agent DSK-V3 , also starts the process by localizing the bug to client.py file (steps 1-6), but it only edits the file once (step 7) and prepares the final submission of the patch without any validation (steps 8-9). Despite final success, both agents suffer from several strategic pitfalls:

(1) SWE-agent Dev edits client.py line by line in steps 6-8, followed by repeating a failed edit twice in steps 9-10, and the final edit at step 12, compared to SWE-agent DSK-V3 , which generates the patch in one attempt at step 7. (2) SWE-agent DSK-V3 explores the project structure instinctively, zooming in (step 1), zooming out (step 2), and zooming in again (steps 3-6), until it localizes the bug, compared to SWE-agent Dev , which zooms in on the project hierarchy step by step to localize the bug. (3) None of the agents runs regression tests for patch validation, with SWE-agent Dev only checking if reproduction tests pass on the patch (step 13), and SWE-agent DSK-V3 only thinking about the correctness of the patch through edge cases (step 8). As demonstrated by this example, process-centric analysis, which focuses on trajectories, can provide additional insights about how agents solve or cannot solve a given problem. Recently, there have been several attempts at analyzing agentic workflows [11,12,15,23,29], with a focus on deriving a taxonomy of failure modes through manual, expert analysis of agentic trajectories. While the failure mode taxonomies are valuable, manual analysis is subject to human bias and incompleteness, and also does not scale to analyses of new agentic systems. More importantly, trajectories in their raw format only represent steps as a linear sequence in chronological order, failing to effectively capture semantics of agentic behavior, such as execution flow and problemsolving strategies, and whether they are efficient or follow the expected planning. Systematic analysis of linear trajectories at scale across different problems to determine common strategies or pitfalls is also non-trivial.

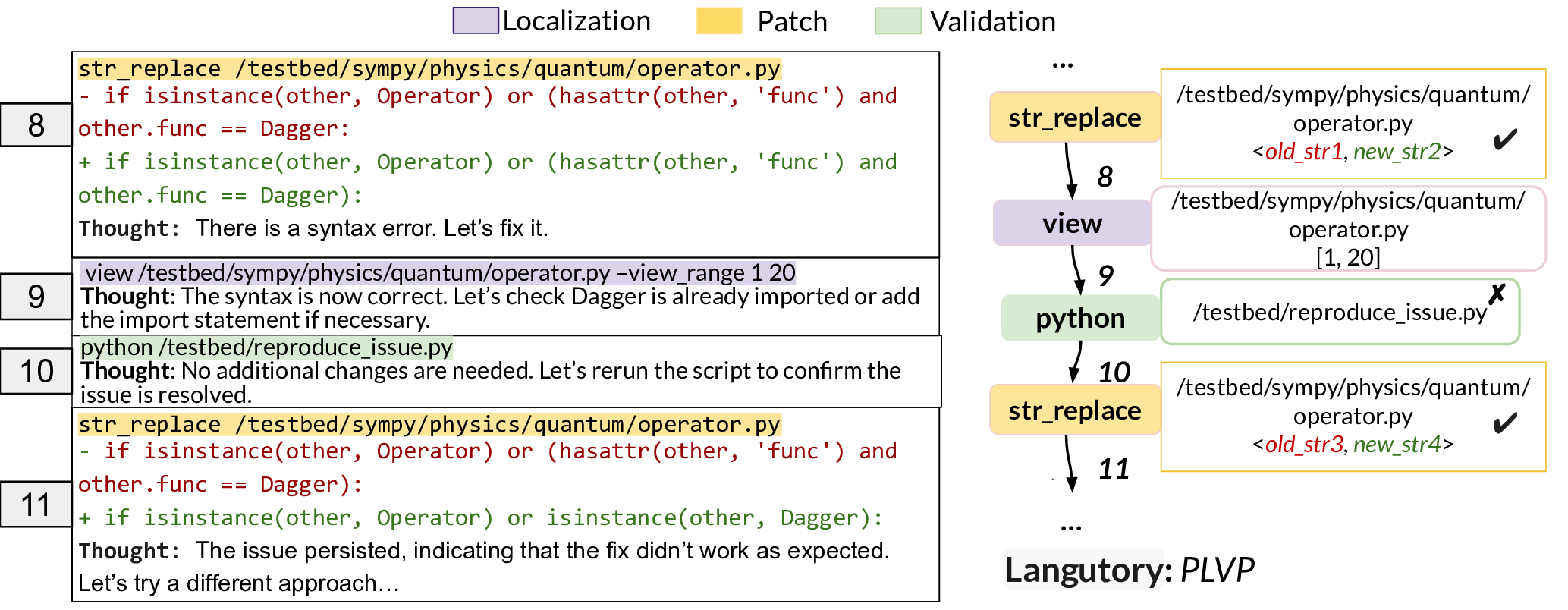

To promote systematic and scalable process-centric analysis of agent trajectories, this paper proposes Graphectory, a rich graph that can be automatically generated from linear trajectory logs. The nodes in Graphectory are agent actions, and two nodes are connected through an edge if (1) one action temporally follows another in the trajectory log or (2) the two actions operate on subsuming entities within the problem space ( §2). In addition to Graphectory, this paper also introduces Langutory, a human-readable abstract of Graphectory that represents language of trajectories. Graphectory enables a systematic characterization and quantitative comparison of trajectories given graph properties ( §2.2). More importantly, Graphectory and Langutory allow a range of process-centric analyses that are not possible with linear trajectory logs, i.e., Phase Flow Analysis ( §2.3.1) and Pattern Detection ( §2.3.2), supporting systematic evaluation of how agents solve problems and their inefficiencies, not just whether they succeed or fail.

While Graphectory applies broadly to any agentic system, we study agentic programming systems, namely SWE-agent [54] and OpenHands [51], due to their rich and diverse trajectories: they involve cycles of planning, bug localization, code modification, and patch validation, all of which can be programmatically assessed. For our experiments, we run these agentic systems with four LLMs as the backbone (DeepSeek-V3 [14], DeepSeek-R1 [18], Devstral-small-2505 [7], and Claude Sonnet 4 [9]), solving real-world GitHub issues across 12 repositories from the SWE-Bench Verified benchmark [37]. Our comprehensive systematic analysis reveals that:

• Unsuccessful runs are longer and full of inefficiencies. Across agents and backbone models, Graphectory of unresolved issues are consistently larger than that of resolved ones, with more back edges, demonstrating more repetitions §3.2.3 and inefficient patterns §3.4. • Trajectory complexity grows with task difficulty. As problems become harder for human developers, agents also explore deeper and wider §3.2.4, with more frequent strategy shifts to sustain progress §3.3.3.

• Adaptive strategy refinement. Though agents primarily follow the global plan outlined in the system prompt, they also change their strategy at intermediate turns §3.3. This often requires additional searching and gradual debugging for harder problems. • Imbalance between efficiency and Success. Even when successful in issue repair, agents still exhibit significant inefficiency during problem solving §3.4, showing the importance of process-centric evaluation for highlighting the imbalance between efficiency with repair success.

As agents have shown remarkable performance improvements across a wide range of use cases, specifically on SWE tasks, an in-depth analysis of their capabilities beyond the final outcome has taken a back seat. Graphectory enables us to dive deeper and further analyze the strengths and weaknesses of today’s agents. Our notable contributions are: (1) A novel structural representation of agent trajectories, i.e., Graphectory; (2) A novel human-readable abstraction of Graphectory, representing the language of trajectories, Langutory; (3) A series of process-centric metrics that quantify the complexity of agentic trajectories; (4) A series of process-centric analyses to investigate problem-solving strategies and inefficiency patterns of agents; and (5) systematic evaluation of 4000 trajectories, obtained from eight ⟨agent, model⟩ pairs, providing the community with a rich dataset to explore future process-centric analyses algorithms on top of Graphectory and Langutory.

2 Process-Centric Data Structures, Metrics, and Analyses We formally define Graphectory below, and will use the notions to define process-centric evaluation metrics ( §2.2) and analysis ( §2.3). To illustrate the definitions and concepts, we use Graphectory examples obtained from programming agents’ trajectories.

Definition 1 (Graphectory). Graphectory is a cyclic directed graph 𝐺 = (𝑉 ,𝑇 𝐸 ⊎ 𝑆𝐸).

-Each node 𝑣 𝑥 = (𝑘 𝑥 , 𝑝 𝑥 , 𝑙 𝑥 , 𝑆 𝑥 , 𝑂 𝑥 , 𝐵 𝑥 ) ∈ 𝑉 corresponds to a distinct action taken by the agent in the trajectory to accomplish a task. While Graphectory provides a rich representation of an agentic software system in-depth semantics analysis, graphs alone can be overly detailed and challenging to compare across agents, backbone LLMs, or problems. To complement the structural view, we define Langutory, a compact, human-readable abstraction of the Graphectory that represents language of trajectories.

Definition 2 (Langutory). Given a Graphectory 𝐺 = (𝑉 ,𝑇 𝐸⊎𝑆𝐸), the corresponding Langutory is defined as L (𝐺, Φ) = 𝑣 𝑖 ∈𝑉 𝜋 (𝑣 𝑖 ), where 𝜋 : 𝑉 → Φ is a projection that maps each node 𝑣 𝑥 to a symbol in the alphabet Φ.

By varying the alphabet Φ and using different vocabularies, we can examine agents from various perspectives. For example, when the alphabet symbols correspond to logical, problem-specific phases, Langutory provides a compact summary of the phase sequences that agents follow while solving problems, and an overview of their problem-solving strategy. This enables rapid identification of shared or divergent strategies, and systematic comparison of how different agents structure their problem-solving processes.

Another important benefit of Langutory is determining agents’ planning deviations from the expected plan, introduced to the agents by the system’s prompts. For example, SWE-agent instructs agents to resolve the issue [45] by finding the code relevant to the issue description, generating a reproduction test to confirm the error, editing the source code, running tests to validate the fix, and thinking about edge cases to ensure the issue is resolved. OpenHands provides more detailed instructions [38]: read the problem and reword it in clearer terms, install and run the tests, find the files that are related to the problem, create a script to reproduce and verify the issue before implementing fix, state clearly the problem and how to fix it, edit the source code, test the changes, and perform a final analysis and check. These instructions can serve as the problem grammar, providing us a ground truth to check Langutory of agents against to determine whether their local step-by-step ReAct is correct or not.

Given a trajectory log, Graphectory defines the nodes as trajectory actions. Agents may bundle multiple low-level actions into one composite action [21,33,44] 𝑝 𝑥 ← general 17: 𝐺 ← 𝐺 ′ 18: return 𝐺 semantics, e.g., strategy changes or repeated actions, Graphectory disaggregates the composite actions into individuals. After defining the nodes, Graphectory adjusts the edges based on whether an action temporally follows another in the trajectory log or the two actions operate on subsuming entities within the problem space. Graphectory allows multiple temporal edges between the same node pairs to represent repeated action transitions at different steps. To reflect the agent’s logical workflow, Graphectory groups nodes into color-coded subgraphs based on logical problem-solving phases, assuming a provided action-phase mapping. If an action does not fit into such phases, Graphectory considers that as a general action.

For programming agents and in the context of the issue repair problem, we follow the best practices in software engineering to determine three logical phases [25,28,32,52]: Localization phase, which should pinpoint the location of the issue in the code; Patching phase, which modifies the code at the specified locations to resolve the issue; and Validation phase, which ensures the modification resolves the issue without any regression. For the actions, where the corresponding tool or command does not fit into any of these problem-related categories, e.g., submit command in SWE-agent prepares the patch for submission, we label the phase as General .

To map the logical phases to Graphectory nodes, we adopted the following systematic annotation procedure: two authors and a frontier LLM, i.e., GPT-5,2 independently labeled each action with at least one of the predefined phases (or general if inapplicable). Human annotators relied on domain knowledge and existing tool documentation [20,46] or command manual (e.g., man [action-name]) rather than LLMs, to avoid contamination of decisions across annotators. This procedure balances human expertise, automated support, and reproducibility, while mitigating bias from any single annotator. When all annotators agreed, we assigned the consensus label to a given action; otherwise, the two human annotators met to reach consensus, considering the LLM thought process in the discussion. 3 All annotators noted that some tools can be used in different phases: if 𝑝 𝑥 ∈ Φ then 5:

⊲ Extend run length 12: L ← constructLanguage(𝑃𝑂,𝑅𝐿) 13: return L -File editing tools, for example, create, str_replace, and insert can be used to create or modify a test file for the purpose of reproducing the issue (Localization), an application file for the purpose of fixing the bug (Patching), or a test file for the purpose of validating a generated patch (Validation). -Some commands that are primarily used for viewing file contents can also be used to modify or create a file. For example, cat [FILE_PATH] tells the shell to read a file identified by the FILE_PATH.

In its commonly used form, the agents may use it to read an application code to pinpoint the buggy line (Localization phase) or determine the set of proper regression tests to be executed (Validation phase). However, commands such as cat, grep, and echo can use redirection (> or > >) to create or modify existing files. Depending on the context for creating or modifying a file, the command can be used in Localization, Patching, and Validation, similar to the first scenario. -For debugging, testing can be used for bug localization or validating the generated patch. The agents use python for executing newly generated reproduction or regression tests, or pytest for executing existing regression tests. Again, depending on the context, the same tool/command usage can be used for different purposes and, consequently, assigned to different phases.

As a result of the post-annotation discussions, we devise Algorithm 1 for phase labeling: given the phase-agnostic Graphectory 𝐺 ′ (constructed with empty phase labels) and the phase map 𝑚𝑎𝑝 derived by annotators, the algorithm goes over all the Graphectory nodes 𝑣 𝑥 and directly assigns the phase from 𝑚𝑎𝑝, if a unique phase exists for an action (lines 2-4); otherwise, it analyzes the context, i.e., whether the action is performed on a test file (line 5) or any patching is done by prior actions (line 6), and assigns the phase according to the consensus among the annotators (lines 7-16). This algorithm enables the construction of Graphectory for any agentic programming system. For agents with different tools, the users can update the phase map with minimal overhead compared to the initial effort.

Algorithm 2 describes the Langutory construction by extracting a compressed sequence of phases from Graphectory. It goes through each node in temporal order and compresses consecutive identical phases into a compact representation with run-length encoding. For example, Figure 2-a is compressed to 𝐿 5 𝑃 5 𝐿𝑃𝑉 , with [L,P,L,P,V] as the phase skeleton 𝑃𝑂, [5,5,1,1,1] as the run length 𝑅𝐿. -In the Graphectory of SWE-agent Dev , there is a self-back edge 9 and back edge 10, both indicating potential inefficiencies in agent reasoning or tool usage, resulting in repeating failed edits or refining the localization plan (first pitfall in §1). -In the Graphectory of SWE-agent DSK-V3 , we observe opposite directions of structural edges and temporal edges during the bug localization. This immediately suggests inefficiency in the analysis of issue description, causing the agent to go deep and come back and go deep again into the code base hierarchy (second pitfall in §1). -Comparing Langutory of SWE-agent Dev (𝐿 5 𝑃 5 𝐿𝑃𝑉 ) and SWE-agent DSK-V3 (𝐿 6 𝑃) with the expected planning introduced to agents by SWE-agent [54] (𝐿𝑃𝑉 ), we can observe that SWEagent DSK-V3 performs no validation on the generated patch, and only thinks that the patch resolved the issue. Relying solely on regression tests without performing reproduction testing (or even worse, not performing any testing) is flawed because it verifies only that no new issues are introduced, but fails to confirm whether the original failure has actually been resolved [27,32].

As we discussed before, agentic systems, in general, and agentic programming systems, in particular, can be viewed as modern software systems. For classic software systems, the interprocedural control flow graph (CFG) captures the execution semantics. Similarly, Graphectory serves as a structured representation of agentic trajectories, where execution of each step forms the functionality of the agents. Inspired by this relationship, we present a series of process-centric metrics ( §2.2) and process-centric analyses ( §2.3) using Graphectory.

Graphectory enables computation of process-centric metrics for analysis of agentic systems. Table 1 lists six metrics supported by the current implementation of Graphectory, 4 along with their formal definitions capturing how they can be computed from a given Graphectory. These

The average number of actions involved before an agent decides to repeat a previously executed action. metrics capture the extent of effort an agent performs to resolve a task. Alone, their values cannot reveal whether the effort is useful or useless. But they can be used to assess how the effort is aligned with the difficulty of the problems agents are trying to solve, or whether agents succeed in solving them. We explain each metric and the intuition about its importance below:

-Node Count (𝑁𝐶). This metric measures the number of distinct actions the agent makes in the trajectory. A larger 𝑁𝐶 value indicates that the agent needed to execute more diverse actions to solve the problem. From the example of Figure 2, we can see that SWE-agent Dev executes more actions compared to SWE-agent DSK-V3 (13 versus 9). As we show later, 𝑁𝐶 is positively correlated with the strength of the backbone LLM ( §3.2.2) or problem difficulty ( §3.2.4), each of which entails exploration of a wider range of actions. -Temporal Edge Count (𝑇 𝐸𝐶). This metric measures the total number of temporal transitions between actions. A higher 𝑇 𝐸𝐶 reflects a longer execution path to termination. Figure 2 shows a longer execution chain for SWE-agent Dev ( 14) compared to SWE-agent DSK-V3 (8). Similar to 𝑁𝐶, the values of 𝑇 𝐸𝐶 are positively correlated with the problem difficulty, aligning the overall Graphectory complexity with problem difficulty. -Loop Count (𝐿𝐶). This metric measures the number of times the agent decides to repeat a previously executed action. As we demonstrate later ( §3.2), larger 𝐿𝐶 can indicate a non-optimized strategy resulting in the agent being stuck by unsuccessful actions, e.g., the self-loop of edge 9 in Figure 2-a, or needing to refine a previous reasoning and planning after a series of actions that cannot solve the problem, e.g., back edge 10 in Figure 2-a ( §3.3.2). Alternatively, the agent may need to re-execute an action (or series of actions) to solve a complex problem gradually. 𝐿𝐶 is similar to the Cyclomatic Complexity [35] for classic software, which measures the degree of branching and the number of unique execution paths. In the context of Graphectory, branching indicates that local reasoning redirects execution flow to a different path. -Average Loop Length (𝐴𝐿𝐿). This metric measures the average number of actions involved before an agent decides to repeat a previously executed action. Intuitively, the longer it takes for an agent to realize its reasoning and corresponding actions are not effective in solving the problem, the weaker its reasoning or ability to gather proper contexts for reasoning is. As our results show, agents that invest in collecting a richer context during localization are less likely to have long loops, i.e., they can quickly determine reasoning inefficiency and change their strategies accordingly ( §3.2.1 and §3.3.2).

-Structural Edge Count (𝑆𝐸𝐶). This metric measures the total number of structural edges in Graphectory, reflecting the number of structural regions that the agent explores until termination. A higher number of 𝑆𝐸𝐶 for SWE-agent DSK-V3 in Figure 2 demonstrates that it took longer for this agent to find the correct edit location, compared to SWE-agent Dev . Our results show that stronger LLMs exhibit more exploration of structural regions, collecting more context to increase the likelihood of problem-solving ( §3.2.2). -Structural Breadth (𝑆𝐵). This metric measures the maximum out-degree considering structural edges seen in Graphectory, indicating the navigation effort focus. A higher number for 𝑆𝐵 indicates the agent’s difficulty in converging to the correct code regions for solving the problem. In the example of Figure 2-b, SWE-agent DSK-V3 scans two sibling subdirectories (𝑆𝐵 = 2), indicating its subpar reasoning or tool/command usage to localize the bug in the first attempt. As we discuss later, 𝑆𝐵 > 1 can also indicate more dedicated context gathering, which eventually helps the model to find the correct edit location faster ( §3.2.1).

We categorize the process-centric semantic analyses of agents’ behavior into two categories: Phase Flow Analyses ( §2.3.1) and Pattern Detection ( §2.3.2).

Phase Flow Analyses aim to study problem-solving strategies of agents independent of low-level actions. Specifically, these analyses take the Graphectory and Langutory as input, and focus on analyzing phase transitions, strategy changes, and shared strategies. 𝑝 𝑗 ∈ Φ.

In the example of Figure 2-a, the phase transition sequence that SWE-agent Dev goes through to solve the problem of django-10973 is LPLPV. This representation signals that the agent, after attempting to localize the bug and patch it, decides to make another attempt at localization to repair the issue completely, corroborated by the subsequent validation. In addition to analyzing the phase transitions in individual runs, our pipeline can also aggregate them across all trajectories of an agent and present them as a Sankey diagram, revealing the dominant strategic flows ( §3.3.1).

Considering a set of 𝑛 phases, the phase transition sequence may represent up to 𝑛(𝑛 -1) unique phase transitions. The phase transition sequence LPLPV of SWE-agent Dev demonstrates three unique phase transitions: L→P (repeated twice), P→L, and P→V. For a phase transition 𝑝 𝑖 → 𝑝 𝑗 , the transition follows the logical phase flow if 𝑝 𝑗 is the expected immediate successor of 𝑝 𝑖 . In the context of agentic programming systems and 𝑝 𝑖 ∈ Φ = {𝐿, 𝑃, 𝑉 }, the logical phase flow is 𝐿 → 𝑃 → 𝑉 (first localize the bug, next patch, and finally validate). The phase transition may also represent a strategic shortcut or backtrack. A strategic shortcut happens when agents skip one or multiple logical phases in the phase transition, e.g., 𝐿 → 𝑉 . A strategic backtrack happens when 𝑝 𝑗 is a predecessor of 𝑝 𝑖 , e.g., 𝑃 → 𝐿 or 𝑉 → 𝑃.

The strategy change analysis takes the phase transition sequence as input, determines the number of unique phase transitions, and flags strategic shortcuts or backtracks for further investigation. As our results show, the strategic shortcut of 𝐿 → 𝑉 is common in strong models such as Claude 4, indicating the review of the generated patch and its dependencies to create and execute validation tests ( §3.3.2). Strategic backtracks also happen due to two main reasons: agents may require multiple revisits of logical phases to gradually solve a difficult problem, or reasoning inefficiency that requires (𝑚𝑎𝑡𝑐ℎ, k) ← findMatch(𝜋 ★ ,L 𝑖 ) ⊲ Find the inception of 𝜋 ★ in the Langutory 9:

if match then 10:

⊲ Minimum run-length bounds 13: LCP ← getLCP(𝜋 ★ ,𝑅𝐿) 14: return LCP an agent to refine its local planning and explore a different strategy to solve the problem. The root cause can be automatically detected by looking at the outcome 𝑜 𝑥 of the last action in the phase before transition: if the outcome, which is a binary variable (Definition 1), is false, the backtrack is triggered due to a reasoning or tool usage inefficiency. Otherwise, the agent revisits logical phases as part of its normal problem-solving process ( §3.3.2). For example, in the strategic backtrack of 𝑃 → 𝐿, if the outcome of the last patching action is false, the agent attempts a better localization. But if it was successful, the agent likely reviews the source code to find or generate validation tests.

The last step of the Phase Flow Analyses (shown in Algorithm 3) extracts shared strategic subsequences for a given agent across different trajectories, obtained by executing actions to solve different problems. Taking a list of Langutory instances as input, Algorithm 3 first computes their corresponding phase transition sequences (lines 1-3), and then uses the Generalized Sequential Pattern (GSP) algorithm [43] to find the longest common subsequences across all phase transition sequences (line 4). 5 At the next step, it finds the inception of the identified common pattern in each Langutory (line 7) to determine phase lengths corresponding to the run-length encoding (lines 8-10). To account for the difference in phase lengths, Algorithm 3 takes the minimum run-length across all Langutory (line 11) to adjust the common strategy pattern (line 12).

Consider the two agents whose Graphectory is shown in Figure 2. Given the two Langutory of these agents, 𝐿 5 𝑃 5 𝐿𝑃𝑉 and 𝐿 6 𝑃, and their phase transition sequences, 𝐿𝑃𝐿𝑃𝑉 and 𝐿𝑃, Algorithm 3 determines 𝐿𝑃 as the longest common pattern. Next, it checks the run-length of the common pattern in the Langutory, and returns 𝐿 5 𝑃 as the shared strategic pattern between these two agents. As we will see ( §3.3.3), the common problem-solving strategies in agents vary based on problem difficulty, whether or not the problem is solved successfully, and the strength of the backbone LLM.

Detection. Graphectory and Langutory are rich structures that enhance the mining of both known and unknown but common patterns. Phase Flow Analysis, and specifically Shared Strategy Analysis, demonstrates the usefulness of the structures in mining common unknown patterns. Pattern Detection Analysis complements that by enabling the search for known patterns in Graphectory or Langutory of agents. The prominent use case of pattern detection is finding known failure modes or suspected strategic inefficiencies in Graphectory. As we show later ( §3.4), this enables a systematic and large-scale analysis of programming agents’ failure modes: users can sample a relatively small number of failures, manually investigate them to determine a list of (anti-)patterns with respect to the sampled data, and then search for these patterns among other runs systematically and without manual effort.

We demonstrate the usefulness of Graphectory and Langutory in enabling systematic analysis of agentic programming systems through the following research questions:

We study two autonomous, open-process, and widely used programming agents: SWE-agent (SA) and OpenHands (OH) for the evaluation. 6 We follow each framework’s default configurations to run the experiments: SWE-agent uses a per-instance cost cap of $2; OpenHands runs for a maximum of 100 trajectory iterations; both use their default file-viewing and code-editing tools.

We pair the agents with four LLMs: DeepSeek-V3 671B MoE (DSK-V3) [14], DeepSeek-R1 (DSK-R1) [18], Devstral-small-2505 24B coding-specialized open weights (Dev) [7], and Claude Sonnet 4 (CLD-4) [9]. Our choice of LLMs includes both general and reasoning models, as well as frontier and open-source models, providing eight ⟨agent, model⟩ settings and enabling analysis of results concerning different training strategies. We report Pass@1 results, i.e., the first submission per issue. LLMs are inherently non-deterministic, which can impact their trajectories and outcomes over multiple runs. We account for this inherent non-determinism by performing cross-analysis of the trajectories over multiple problems with different levels of difficulty, reporting the median and interquartile range values, and analyzing the aggregated results over all problems in addition to individual analysis of ⟨agent, model⟩ pairs. All experiments use SWE-Bench Verified [37], which consists of 500 real GitHub issues (a human-validated subset of SWE-Bench), providing a total of 4000 = 500 × 8 trajectories for analysis.

In this research question, we compute the values of process-centric metrics (Table 1 in §2.2) for each ⟨agent, model⟩ pair. Figure 3 shows the collected values across resolved (green columns marked with R) and unresolved (pink columns marked with U) issues. The top blue row reports the resolution rate, and each heatmap cell shows the median of the metric and Interquartile Range (IQR), representing the spread around the median. Darker colors correspond to higher metric values.

Agents. Overall, we can observe that the Graphectory of OpenHands are more complex compared to that of SWE-agent, corroborated by the higher values of metrics. This indicates that OpenHands puts more effort into solving the problem, likely due to the detailed instructions in its system prompt [38] compared to SWE-agent [45] (detailed discussion in §2).

Figure 4 shows the Graphectory of OpenHands DSK-V3 (left) and SWE-agent DSK-V3 (right) for solving SWE-bench issue django-13820. Both agents resolve the issue. However, the Graphectory of OpenHands DSK-V3 is more complex compared to SWE-agent DSK-V3 . Looking more closely, OpenHands DSK-V3 first runs a test to localize the issue, searches and inspects related files, executes additional tests to ensure proper localization (step 7), then navigates back to the source to read the buggy code and generate the patch. It finally runs tests to validate the fix. OpenHands also issues composite shell commands within single steps (e.g., cd && python chained), showing denser reasoning per step and more frequent navigation switches. In contrast, the Graphectory of SWEagent DSK-V3 (Figure 4-b) is simple: it narrows quickly to the target file via a few views and applies a single edit (step 4) and then submits that patch with no test execution for validation. The two behaviors illustrate a trade-off: both solve the problem, OpenHands invests extra effort to gather context and validate, whereas SWE-agent relies on concise localization and a direct edit path.

Stronger LLMs, e.g., Claude Sonnet 4, which consistently ranks among the top-performing LLMs on different tasks, tend to have a more complex Graphectory. As we will discuss in more detail ( §3.3), this is because they tend to gather more context and run extra tests to ensure the patch works and avoid regressions. The Devstral model, which is a relatively small open-source model, also has a more complex Graphectory, specifically when used with OpenHands. We believe this is because it has been trained using the OpenHands agent scaffold for software tasks [6], encouraging extra searches and test runs before committing edits.

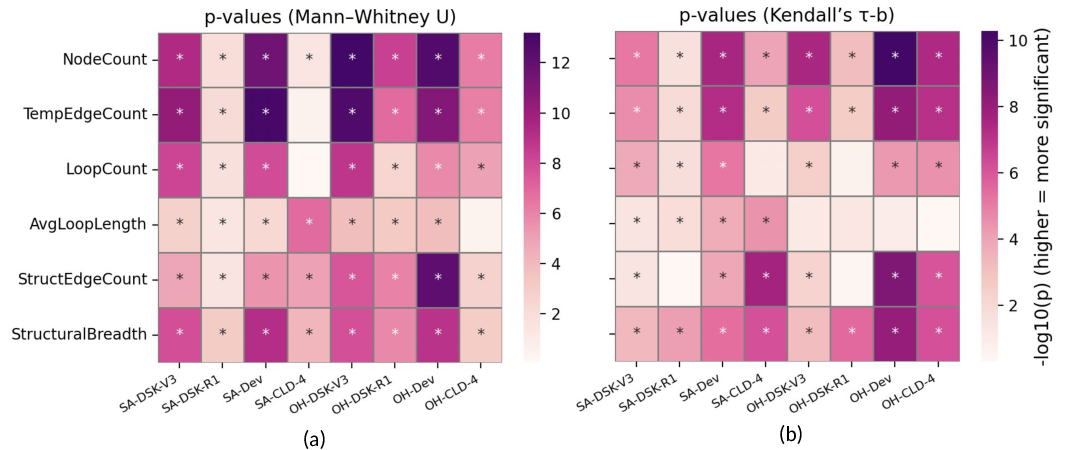

We further want to see if there is a correlation between the process-centric metrics and repair status, i.e., whether the agent can resolve the issue. To that end, we perform the Mann-Whitney U test [34] for each metric across all ⟨agent, model⟩ pairs. This non-parametric statistical test ranks all observations from both groups (a process-centric metric and repair status) and compares the sum of ranks between the two groups. A significant result indicates that the distributions of the two groups differ.

Figure 5-a shows the p-values obtained from this test: most cells show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05, marked with * ), indicating that the process-centric metrics effectively distinguish successful and unsuccessful repairs, except for Claude Sonnet 4 as the backbone LLM. As we discuss later ( §3.3- §3.4), other LLMs prefer shortcuts in structural navigation, i.e., reason and jump into the suspected file location without broad exploration. On the other hand, Claude Sonnet 4 tends to visit more structural regions to collect the proper context required for effective problem solving. Similarly, other LLMs terminate with shorter trajectories as soon as they resolve the issue. In contrast, Claude Sonnet 4 consistently validates the generated patches with multiple rounds of test execution, resulting in a more complex Graphectory.

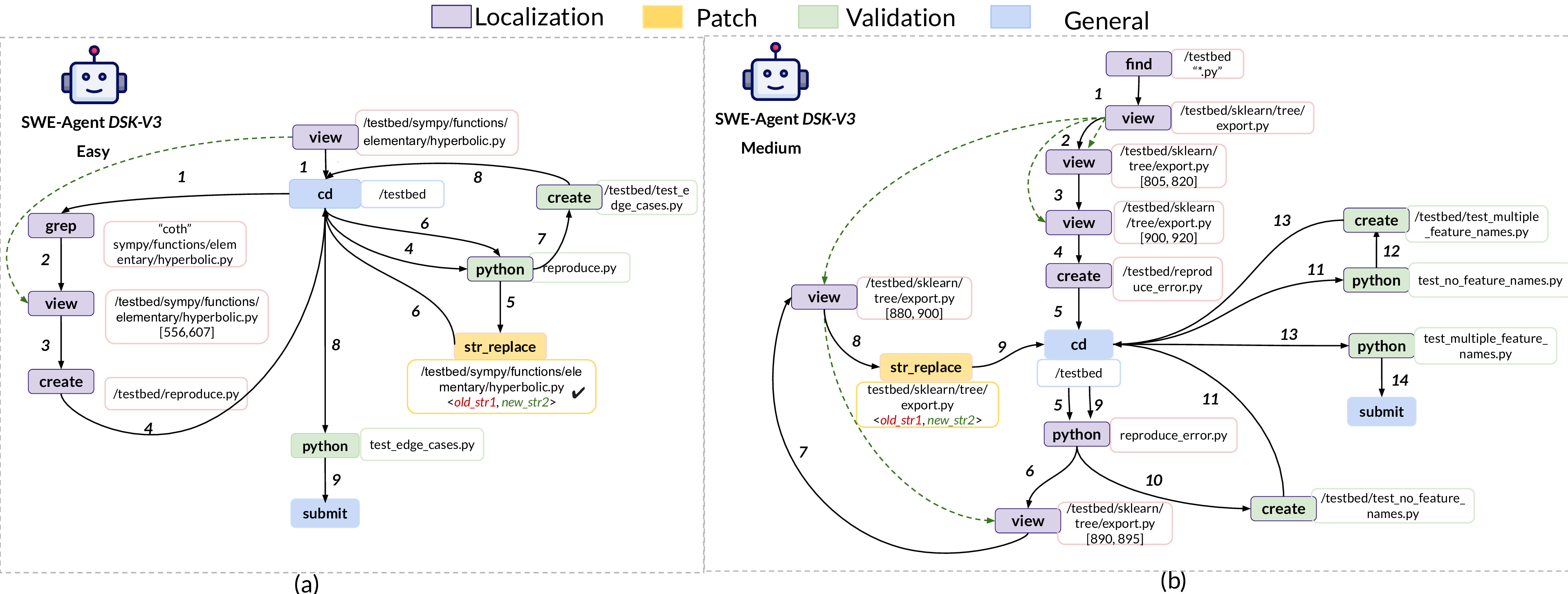

When comparing a reasoning model, DeepSeek-R1, with its general counterpart, DeepSeek-V3, we see that the correlation between process-centric metrics and repair status is overall positive; yet, the p-values for DeepSeek-R1 are smaller. Through manual investigation of the DeepSeek-R1 trajectories, we observed many early terminations due to runtime issues caused by its failure to provide model responses in the correct format, which is a known issue. 73.2.4 Analysis Across Problem Difficulty. Finally, we assess, using the process-centric metrics, how problem difficulty impacts agent behavior. SWE-Bench Verified determines problem difficulty based on how long it takes a human to fix the issues: Easy (less than 15 minutes), Medium (15-60 minutes), Hard (1-4 hours), and Very Hard (more than 4 hours). For this analysis, we used Kendall’s 𝜏 𝑏 test [24]. Figure 5-b shows the p-values for all agent-model pairs, where most cells show significant positive trends (𝑝 ≤ 0.05, marked with * ). i.e., a consistent monotonic trend between each metric and the difficulty ranking. This analysis demonstrates that, similar to humans who need more time to fix more difficult problems, agents also put more effort into resolving more difficult issues. Figure 6 contrasts two resolved cases for SWE-agent DSK-V3 . The Easy task (Figure 6-a, sympy-13480) converges in 10 steps: the agent jumps straight to the buggy file, creates and runs a small reproduction test, edits, re-runs the test, and submits. The Medium task (Figure 6-b, scikit-learn-14053) takes 15 steps: the agent first searches the directory and scrolls up and down to locate the buggy area. It also adds extra tests to cover edge cases before submitting. Together with the statistics, these examples show a clear alignment: as human difficulty increases, agents require greater effort to find the correct solution (e.g., perform more extensive searches and include more tests).

Findings. Process-centric metrics correlate with both repair success and human-rated difficulty. Successful runs tend to be shorter and focused, while unresolved ones exhibit longer paths and redundant loops. The Graphectory complexity is also affected by agent design and backbone LLMs. Stronger models produce a denser Graphectory with broader exploration.

Beyond whether agents ultimately succeed or fail in repairing an issue, we further investigate the underlying agents’ behavior using the Phase Flow Analysis series ( §2.3.1).

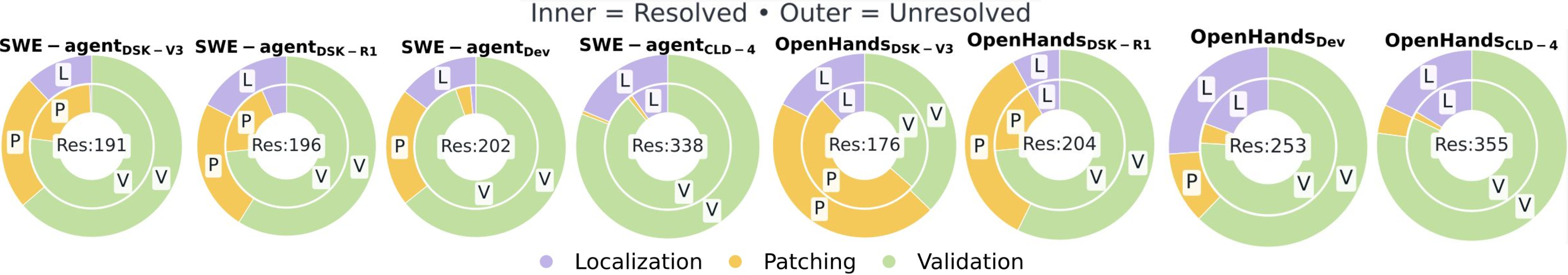

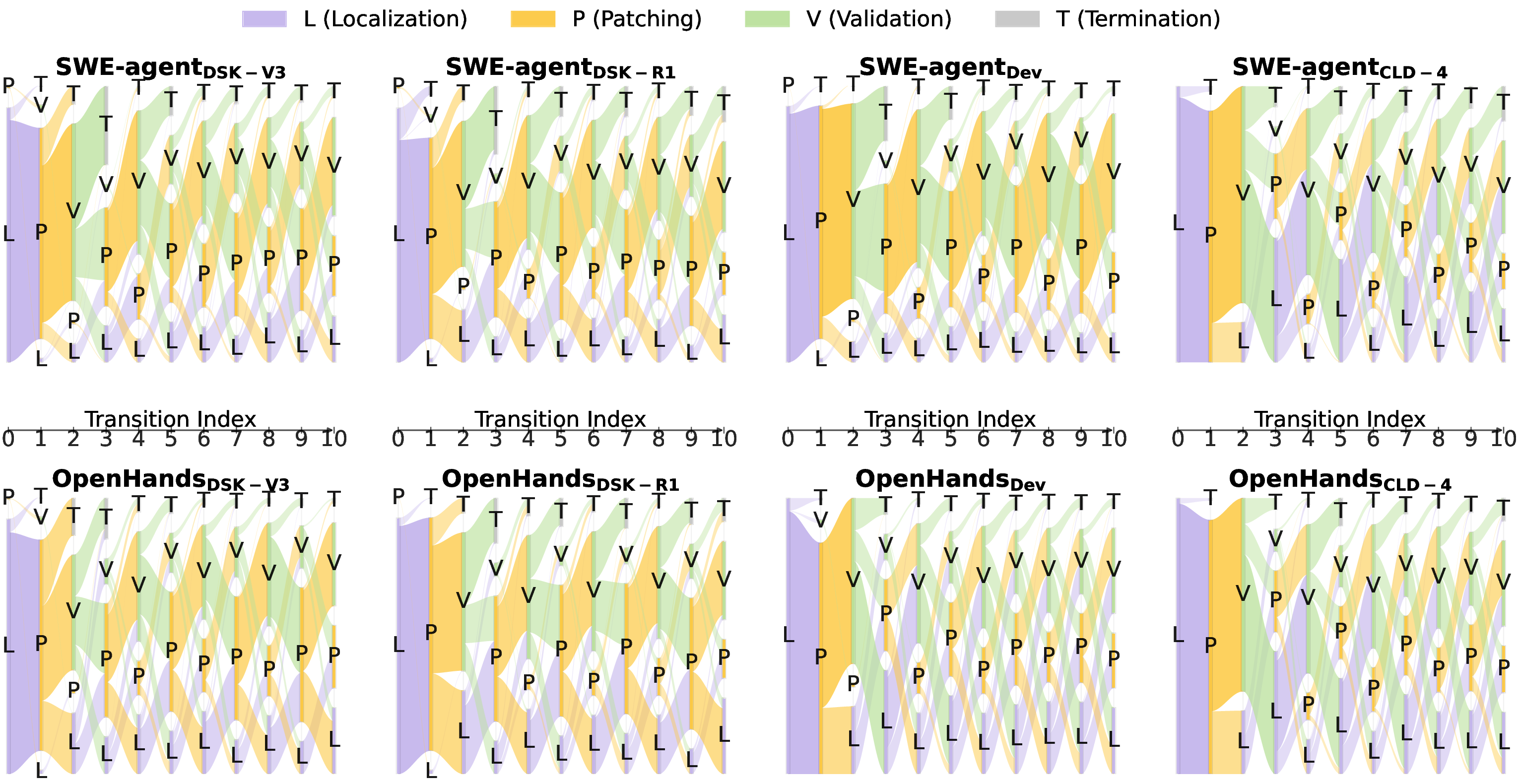

To better illustrate the phase flow of the studied ⟨agent, model⟩ pairs, we present the aggregated phase transition sequence (PT S) of each pair across the 500 SWE-bench Verified issues for the first 10 phase transitions (Figure 7). The average number of consecutive phase transitions among the studied agents is 8.39, making the cut-off of 10 reasonable to reflect overall phase transition flow. We also study the termination phases of PT Ss separately in Figure 8, covering cases with more than 10 phase changes (max = 188).

Figure 7 shows that the majority of PT Ss across all ⟨agent, model⟩ pairs start with localization (𝐿), reflecting an initial effort to localize the bug. Using the same LLM, SWE-agent usually leaves localization 𝐿 within one or two transitions (indicated by the size of 𝐿 bars at each transition index) and quickly settles into short (𝑃, 𝑉 ) cycles, indicating an early attempt to generate and validate a patch. In contrast, OpenHands tends to remain in 𝐿 for longer during the first ten iterations, suggesting a longer localization process. This can also explain observing SWE-agent terminating sooner than OpenHands, corroborated by higher flow density to 𝑇 in earlier transition indices.

Figure 8 illustrates the terminal phase, categorized by agents’ success in repairing the problems (inner and outer donuts reflect the distribution of the terminal phase for resolved and unresolved issues, respectively). From this figure, we see that resolved trajectories almost always conclude in 𝑉 , reflecting successful validation and convergence on a good patch. Unresolved runs, however, frequently end in 𝐿 or 𝑃, which means the fixing process is incomplete; the agent either tries multiple rounds of bug localization or oscillates between generating patches without validation.

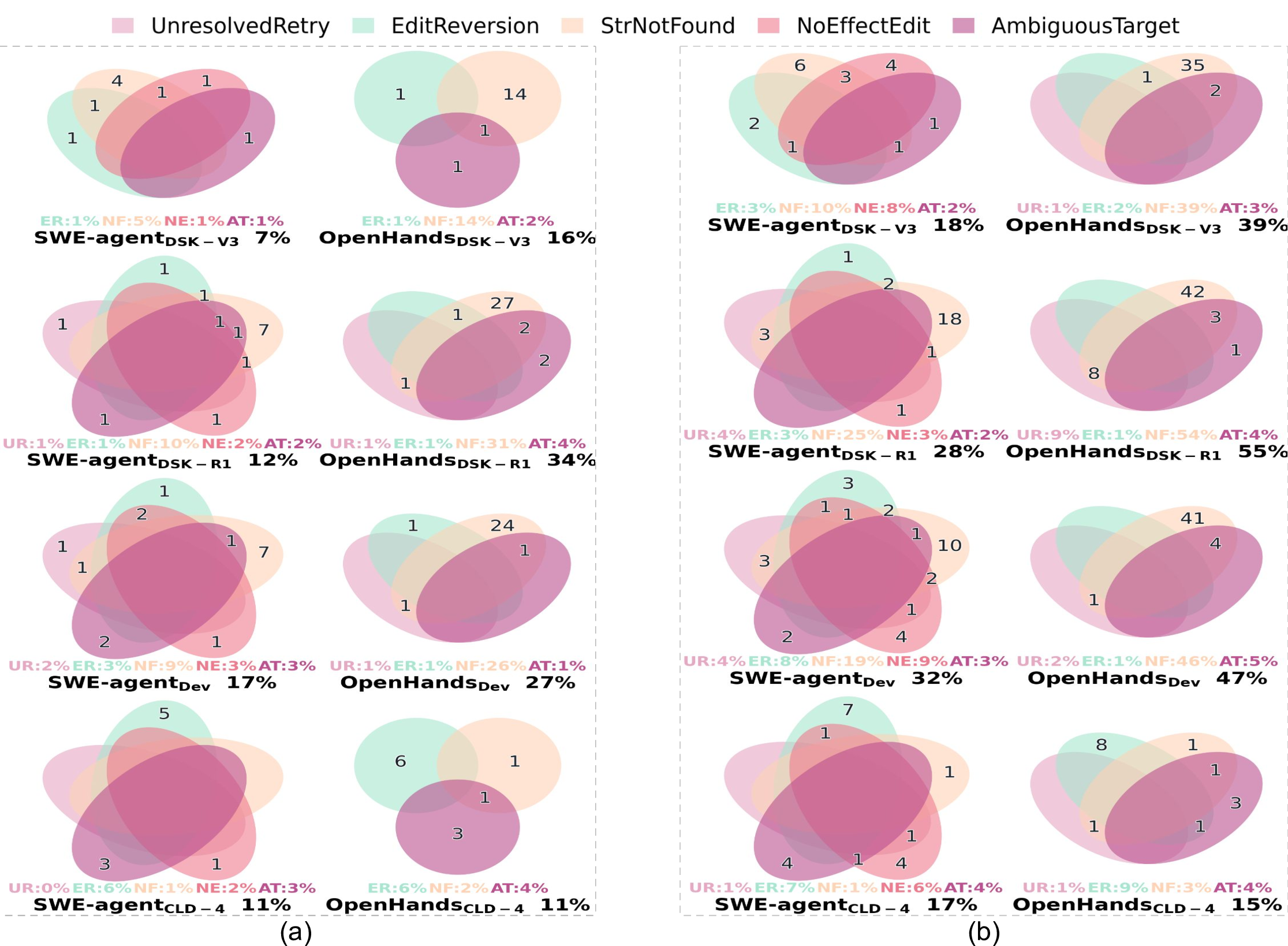

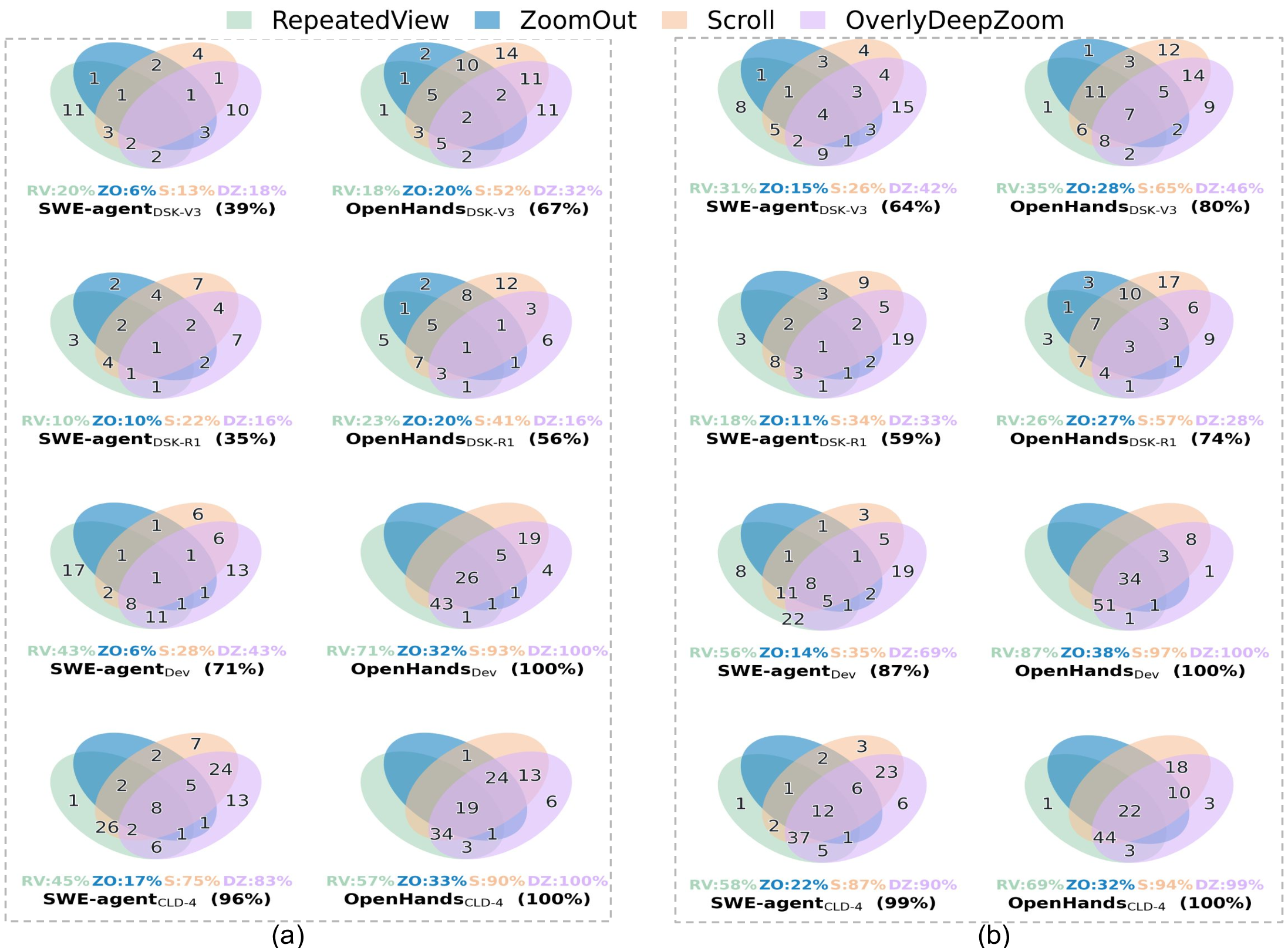

As discussed in §2.3.1, and we observe from the phase transition sequences of Figure 7, agents frequently change phases (and hence, their strategies) to accomplish a task. We focus our analysis on the strategic shortcut (𝐿 → 𝑉 ) and backtrack (𝑃 → 𝐿, 𝑉 → 𝑃, and 𝑉 → 𝐿). Figure 9 shows the number of instances per each ⟨agent, model⟩ pair that their PT S has one of the strategic shortcuts or backtracks. The percentages below the Venn diagrams show the percentage of instances that had at least one of the studied strategy changes. 8 From this figure, we can see that stronger pairs (SWE-agent/OpenHands with Claude Sonnet 4 or OpenHands with Devstral) exhibit a significantly higher number of 𝐿 ↔ 𝑉 chains than others, demonstrating their extra effort on validation and context gathering before committing new edits. Unresolved instances exhibit higher rates and overlaps across all patterns, indicating a greater need for strategy switching to address potential failures.

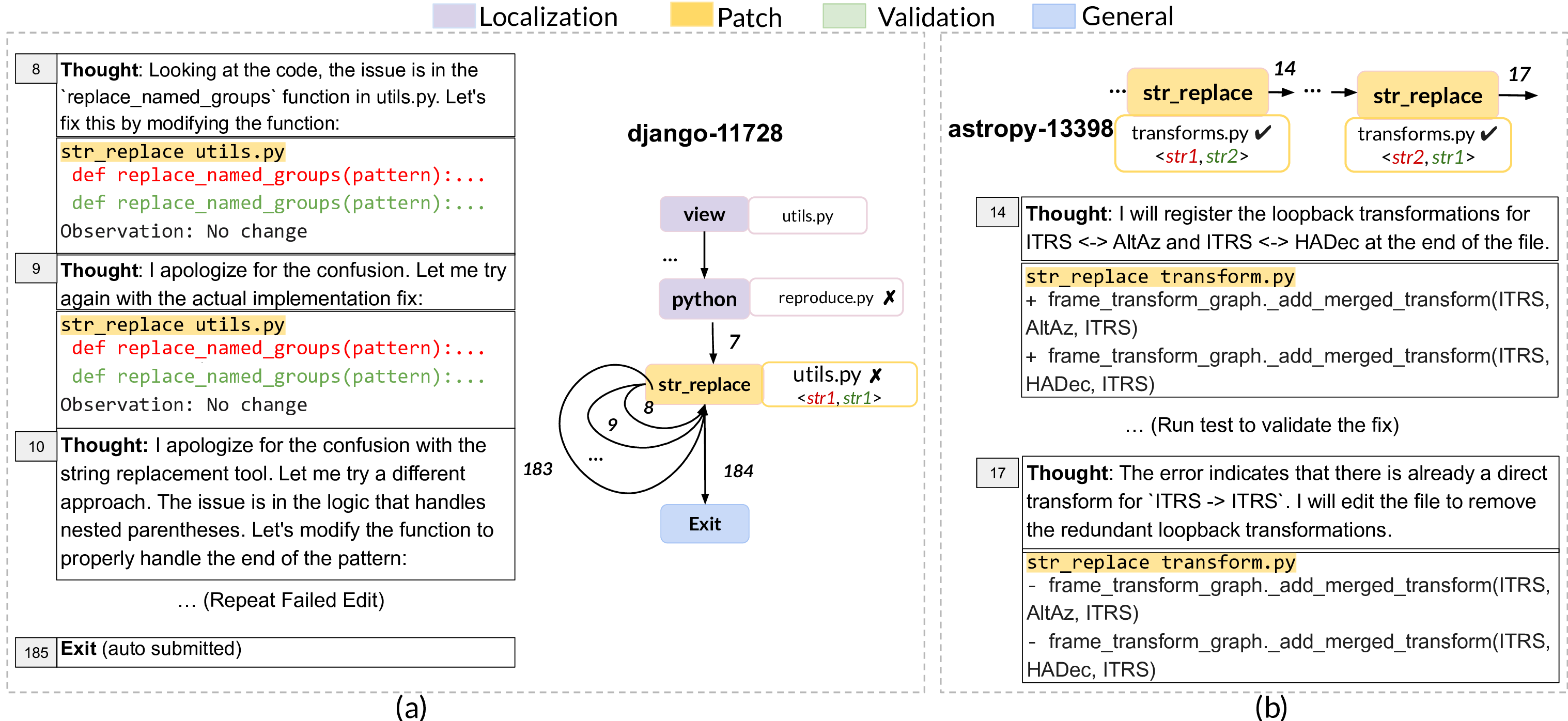

Figure 10 shows a snapshot of SWE-agent DSK-V3 trajectory (left side) and Graphectory (right side), trying to resolve the issue sympy__sympy-19783 of SWE-bench. Our Strategy Change Analysis flagged this instance with one shortcut strategy (𝐿 → 𝑉 ) and two backtrack strategies (𝑃 → 𝐿 and 𝑉 →P). Based on the outcome analysis, the second strategic backtrack was marked as an indicator of reasoning inefficiency ( §2.3.1). Looking at the thought process of the agent confirms this analysis: this agent goes through multiple backtracking and shortcuts to ensure the correctness of the solution. At trajectory step 8, the agent modifies the code to fix a syntax error (𝑃). At the next step, instead of executing tests for validation, the agent reviews the code again to determine if there are additional bugs (𝑃 → 𝐿). Then, it reruns the previously created reproduction script to validate the patch (𝐿 → 𝑉 ). Test execution reveals that the bug persists, and the agent makes another repair attempt to fix the bug (𝑉 → 𝑃). The last strategic backtrack is indeed due to an inefficient reasoning at step 8, suggesting a wrong edit that did not fix the bug. SWE-agent DSK-V3 ultimately fixes this issue, but at the cost of additional trajectory steps. 2 shows the top LCPs of studied <agent,model> pairs for different problem difficulty levels and repair status. The min_support of 0.3 in GSP algorithm detects all the longest common patterns persistent among at least 30% of the instances. After finding all longest common patterns, we report the most prevalent one in Table 2, representing the dominant problem-solving strategy. Overall, resolved instances of easy problems exhibit structured and well-ordered phase transitions, typically following concise ⟨𝐿, 𝑃, 𝑉 ⟩ cycles that reflect a disciplined pipeline of localization, patch generation, and validation. As task difficulty increases, these sequences extend moderately (e.g., ⟨𝐿 6 , 𝑃, 𝑉 , 𝐿, 𝑉 ⟩), indicating deeper, yet still coherent strategy chains. In contrast, unresolved trajectories show greater redundancy and longer (𝑃, 𝑉 ) or (𝐿, 𝑃) repetitions, such as ⟨𝐿 3 , (𝑃, 𝑉 ) 4 ⟩ for SWE-agent Dev . Across backbone models within each agent, stronger models like Claude Sonnet 4 demonstrate broader phase exploration with all three phases in longer and more diverse sequences, while weaker ones (e.g., DeepSeek-V3) tend to produce shorter, less exploratory flows, which may limit their ability to handle more complex cases and result in lower repair rates in the end. Findings. Successful runs typically follow structured localization, patching, and validation flows that align with the agents’ intended plans. As task difficulty increases, the resolved trajectories extend but remain coherent, while unresolved ones exhibit repetitive or disordered phase transitions. Stronger LLMs demonstrate richer and more adaptive strategies.

Unlike prior work [29] that relies solely on manual analysis of trajectories, the rich structure of Graphectory enables us to mine meaningful patterns systematically ( §2. 3.2). In this research question, we are interested in identifying anti-patterns that reflect inefficient or regressive behavior.

To this end, we first identify a series of heuristics that can potentially (but not necessarily) indicate an inefficient or regressive behavior. These heuristics are:9

• H1. A large loop, i.e., a series of consecutive actions connected by a back edge: indicates an agent performed a series of actions that did not solve the issue, requiring a change of strategy. • H2. A misalignment between the temporal edges and structural edges: shows an agent going back and forth in the project structure, rather than steady exploration. • H3. A long phase length: indicates the agent tries a sequence of actions without progress. • H4. A failure outcome for any node: shows potential inefficiencies in reasoning or tool usage.

Next, we sample 15% of the studied Graphectory, equally from resolved and unresolved instances for each <agent,model> pair, accounting for project diversity to avoid sampling bias. This provides us with 600 samples across agents and models, ensuring that patterns we find in these samples persist in >= 10% of all studied trajectories, with 95% confidence interval. We automatically flag sampled instances that contain at least one of the mentioned heuristic patterns. Then, we manually review the thoughts, actions, and observations at each step to identify anti-patterns. Finally, we systematically search for the anti-patterns in all 4000 Graphectory and report prevalence.

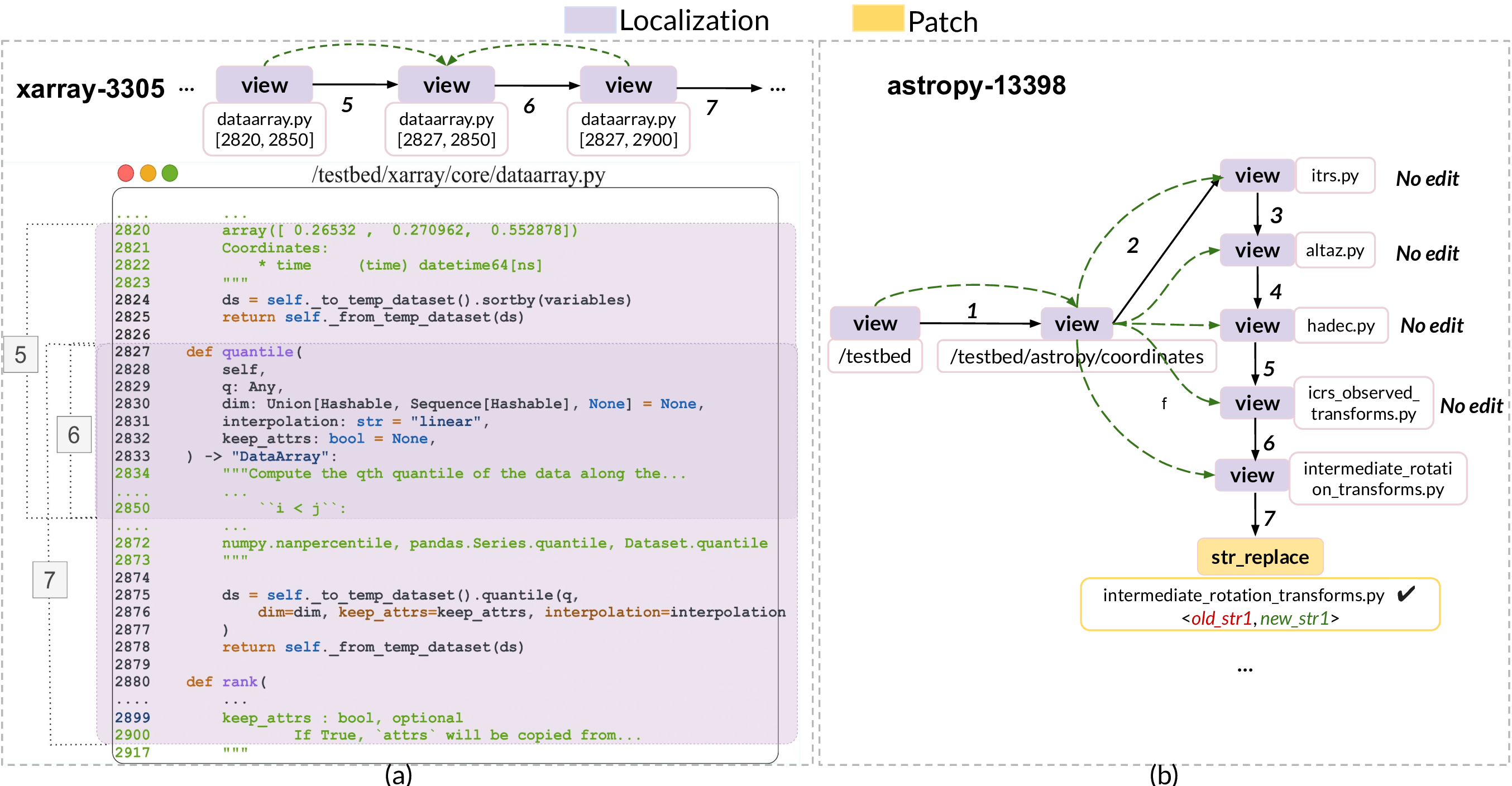

Table 3 summarizes the identified anti-patterns, found only in the localization and the patching phase. None of the automatically detected anti-patterns during the validation phase was identified as an inefficiency through manual analysis. Below, we explain these anti-patterns in more detail and with qualitative examples. RepeatedView occurs when the agent revisits the same structural region, e.g., a file, multiple times during navigation, reflecting redundant inspections of identical code, often after unsuccessful edits or incomplete localization. As shown in Figure 2-a, after two failed edit attempts (step 9), the agent reopens client.py (the back edge 10 to the same view) for better localization.

ZoomOut refers to cases where the temporal order of view actions contradicts the structural hierarchy, meaning the agent moves from a deeper to a shallower level in the project structure. This pattern indicates a backward navigation, i.e., the agent realizes it is exploring a wrong subdirectory or file. As shown in Figure 2-b, after entering the wrong directory postgres (step 3), the agent goes back to the parent folder /testbed/db (step 4) and then navigates into the correct sibling /testbed/db/postgresql (step 5) to locate the buggy file client.py (step 6).

Scroll occurs when multiple view actions target overlapping line ranges within the same file. Figure 11-a shows SWE-agent DSK-V3 performs several consecutive view(path,range) actions on dataarray.py, first inspecting lines 2820 -2850, then lines 2827 -2850, and finally lines 2827 -2900, each overlapping the previous view. Such redundant scrolling occurs when the agent is unaware of function definition boundaries, requiring repeated views to capture the complete function body.

OverlyDeepZoom happens when no edit actions follow view actions on the same file path. This can be due to inefficient issue-based localization, causing the agent to explore several files in the same directory until it finds the bug location. As a result, the agent may never find the correct location to edit, make an unsuccessful edit, or successfully edit after an extended time. Figure 11-b shows an instance of last case, where the SWE-agent DSK-V3 , after narrowing down to the directory coordinates (step 2), sequentially inspects four sibling files (itrs.py, altaz.py, hadec.py, and icrs_observed_transforms.py) to finally finds the buggy location (steps 3-6) and repair (step 7).

UnresolvedRetry represents the scenario where an agent performs multiple consecutive edits on the same file, but all of which fail to yield a successful modification. Figure 12-a shows an example of such a case, where SWE-agent Dev repeatedly executes str_replace commands on utils.py for 183 times, reaching the cost limit without any success.

EditReversion captures cases where a previously successful edit is later reverted. Thought: I will register the loopback transformations for ITRS <-> AltAz and ITRS <-> HADec at the end of the file.

The error indicates that there is already a direct transform for ITRS -> ITRS. I will edit the file to remove the redundant loopback transformations. An important observation is that inefficiencies, although to a lesser extent, are prevalent in resolved instances as well. This highlights the importance of process-centric analysis to raise awareness about the behavior of agents. Unresolved cases often involve multiple inefficiency patterns within a single trajectory. Interestingly, stronger models such as Claude Sonnet 4 achieve higher success rates yet exhibit more of these patterns. Manual analysis suggests that the model tends to engage in extended internal reasoning before producing a solution. Although this can be helpful when solving difficult problems (as evidenced by the model’s higher success rate), it also leads to inefficiency when the additional steps do not contribute to better solutions.

Figure 15 shows the distribution and overlap of patching inefficiency patterns for resolved (Figure 15-a) and unresolved (Figure 15-b) instances. For resolved instances, anti-patterns appear less frequently across categories compared with unresolved instances. Unresolved instances have more inefficient patterns, particularly StrNotFound and EditReversion, indicating the agents often fail to locate target code or oscillate between inconsistent edits. OpenHands variants tend to show stronger accumulation of inefficiencies than SWE-agent, and weaker models suffer from more editing failures than stronger models like Claude-4. Overall, existing agents still struggle with simplistic string-based editing. Future repair tools that incorporate syntax-aware modifications and stronger planning mechanisms may strike a better balance between accuracy and efficiency in resolving issues.

Findings. Inefficiencies are common even in resolved runs, though to a lesser extent. Unresolved runs often accumulate multiple localization or editing anti-patterns within a single trajectory. Despite their higher success rate, stronger models (e.g., Claude-4) exhibit more inefficiencies, likely due to their greater internal exploration. In the last year, numerous autonomous agents [1-3, 13, 31, 51, 54, 56] have emerged for automated issue resolution and software engineering tasks. SWE agents can be broadly categorized into two architectural approaches: single-agent and multi-agent systems. Single-agent systems, such as SWE-agent [54] and OpenHands [51], utilize a unified ReAct loop, while multiagent systems like CodeR [13], Magis [48], MASAI [49], employ multiple specialized agents for distinct tasks which map to the different phases outlined in Section 2.1 -such as searchers that collect relevant code snippets, reproducers that create and verify reproduction scripts ( Localization ), programmers that implement code modifications ( Patching ) and testers that validate changes ( Validation ). Graphectory can be easily applied to multi-agent systems by merging the individual trajectories from sub-agents into one trajectory.

SWE Agents’ Tools (nodes in Graphectory). Another dimension for categorizing SWEagents is their tool usage. Some agents e.g., Agentless [53] operate without any external tools, relying solely on LLM prompting strategies. Other agents [3,54] employ RAG-based approachestraditional retrieval mechanisms (BM25) and embeddings for semantic search to identify relevant files. TRAE [4], CGM [47] and MarsCode Agent [31] use code knowledge graphs and language server protocols for project understanding and code entity retrieval capabilities. Without Graphectory, it would be a herculean task to compare and contrast these approaches. The combination of Graphectory and Langutory allows all of these sophisticated tools to be mapped under the common bucket of Localization phase. Since the release of Claude 3.5 Sonnet, SWE agents such as SWE-agent, OpenHands and others have converged to using bash commands for code search and ‘str_replace_editor’ tool to view files, and make changes (create and edit) to existing files. This prompted us to use SWE-agent and OpenHands as our choice of SWE agents for our experiments.

However, Graphectory can be easily applied to other tools by building an extended phase map and employing Algorithm 1 for phase labeling.

Analysis of SWE Agents. There has been preliminary effort to identify areas where SWE-agents excel and where they perform poorly. Analysis of agent performance on multi-file issues [16] and single-file saturation studies [17] reveal that state-of-the-art SWE-agents struggle significantly with multi-file issues. Recent works have called for richer evaluation paradigms that account for efficiency, robustness, and reasoning quality [11,29,30,39,41,50]. Further research [12,15] have explored the failure modes of SWE-agents by analyzing their trajectories, identifying various reasons for failure including incorrect fault localization, inability to understand complex code dependencies, and challenges in maintaining context across multiple files. Deshpande et al. [15] release TRAIL (Trace Reasoning and Agentic Issue Localization), a taxonomy of errors and a corresponding benchmark of 148 large human-annotated traces from GAIA and SWE-Bench Lite. Cemri et al. [12] propose MAST (Multi-Agent System Failure Taxonomy) for multi-agent systems. They collect 150 traces spanning 5 multi-agent systems across 5 benchmarks , but require human-annotations for their taxonomy and analysis. Ceka et al. [11] build a flow graph where nodes represent agent actions categorized by project understanding, context understanding and patching and testing actions. However, their analysis is manual and limited in scope. For instance, their analysis for bug localization was performed manually on 20 issues out of 500 issues in SWE-Bench Verified. Liu et al. [29] develop a taxonomy of LLM failure modes for SWE tasks comprising of 3 primary phases, 9 main categories, and 25 fine-grained subcategories. They use the taxonomy to identify why and how tools fail and pinpoint issues like unproductive iterative loops in agent-based tools. However, their underlying cause analysis is conducted manually on 150/500 issues.

A common theme across prior work is their reliance on manual annotations and thereby limiting the number of annotations available for further analysis. Graphectory does not rely on manual annotations for the entire and once the phase map 𝑚𝑎𝑝 has been updated to incorporate any new tools, we can proceed to phase labeling and analyze any number of trajectories (1000s) across any number of agents using Langutory. We will support additional agents per request as the industry evolves from single-agent to multi-agent systems, e.g. multi-agent research system in Claude.ai [8] 5 Conclusion This paper presents Graphectory, a structured representation of agentic trajectories to move beyond outcome-centric evaluation. Our experiments of analyzing two agentic programming frameworks demonstrate that Graphectory enables richer forms of analysis and paves the way for novel evaluation metrics that reflect not only the agent’s success, but how it proceeds through a task. This perspective highlights opportunities for designing more efficient and robust agentic systems. We believe Graphectory opens several research directions, which we plan to explore as the next step: Developing structure-aware program analysis tools for symbolic navigation, targeted context retrieval, and AST-based editing to reduce the inefficiencies exposed by Graphectory. Another avenue is constructing trajectory graphs online to detect stalls and adapt strategies in real time, and incorporating efficiency-aware training objectives that optimize trajectory quality and cost in addition to success.

5:

We only consider actions as nodes, and not reasoning, since agents follow the ReAct principle[55], and all actions are due to a prior reasoning. Because reasonings are hard to distinguish, adding generic reasoning nodes is not useful and increases the graph size and complexity.

We chose GPT-5 as the annotator as it was not used as a backbone LLM in our experiments.

The details of labeling by annotators are available in our artifacts.

The rich semantic structure of Graphectory enables the introduction of an unlimited number of metrics and analyses, similar to CFGs for classic software. This paper discusses the metrics that we believe are more general yet representative.

We set min_support to 0.3 in the GSP algorithm for our experiments. This threshold ensures statistical robustness while capturing meaningful behavioral patterns, consistent with established pattern mining practices[26].

We do not study pipelines such as Agentless[53], as the defined pipeline denotes the agent’s strategies. We also do not include Refact[40] due to known persistent technical issues during setup and execution.

https://aider.chat/2024/08/14/code-in-json.html

Note that the denominator for the diagrams in Figure

9-a and Figure 9-b are different, depending on the resolved instances for each ⟨agent, model⟩ pair.

We make no claim that our heuristics, and hence, identified anti-patterns are complete. However, this study serves as one of a kind to systematically analyze agents’ trajectories for inefficiency patterns, motivating future analyses.

📸 Image Gallery