Foundation models often generate unreliable answers, while heuristic uncertainty estimators fail to fully distinguish correct from incorrect outputs, causing users to accept erroneous answers without statistical guarantees. We address this through the lens of false discovery rate (FDR) control, ensuring that among all accepted predictions, the proportion of errors does not exceed a target risk level. To this end, we propose LEC, a principled framework that reframes selective prediction as a decision problem governed by a linear expectation constraint over selection and error indicators. Under this formulation, we derive a finite-sample sufficient condition that relies only on a held-out set of exchangeable calibration data, enabling the computation of an FDR-constrained, retention-maximizing threshold. Furthermore, we extend LEC to two-model routing systems: if the primary model's uncertainty exceeds its calibrated threshold, the input is delegated to a subsequent model, while maintaining system-level FDR control. Experiments on both closed-ended and open-ended question answering (QA) and vision question answering (VQA) demonstrate that LEC achieves tighter FDR control and substantially improves sample retention compared to prior approaches.

Foundation models, like large language models (LLMs) and large vision-language models (LVLMs), are increasingly being integrated into real-world decision-making pipelines (Xiaolan et al., 2025;Brady et al., 2025;Singhal et al., 2025), where it is crucial to evaluate the reliability of their outputs and determine whether to trust them. Uncertainty quantifi- cation (UQ) is a promising approach to estimate the uncertainty of model predictions, with the uncertainty score serving as an indicator of whether the model's output is likely to be incorrect (Zhang et al., 2024;Wang et al., 2025d;Duan et al., 2024;2025). In practice, when the model shows high uncertainty, its predictions should be clarified or abstained from to prevent the propagation of incorrect information.

However, when the model generates hallucinations or exhibits overconfidence in its erroneous predictions (Shorinwa et al., 2025;Atf et al., 2025), uncertainty scores derived from model logits or consistency measures may remain low, leading users to accept incorrect answers without task-specific risk guarantees (Angelopoulos et al., 2024). Split conformal prediction (SCP) can convert any heuristic uncertainty to a rigorous one (Angelopoulos & Bates, 2021;Campos et al., 2024a). Assuming data exchangeability, SCP produces prediction sets that include ground-truth answers with at least a user-defined probability. Nonetheless, set-valued predictions often contain unreliable candidates, leading to biased decision-making in downstream tasks (Wang et al., 2025a;Cresswell et al., 2025). In this paper, we investigate point prediction with certain provable finite-sample guarantees.

Although uncertainty scores cannot perfectly separate correct from incorrect predictions, selective prediction allows us to enforce a risk level (e.g., α): a prediction is accepted if and only if its associated uncertainty score falls below a calibrated threshold, ensuring the false discovery rate (FDR) among accepted predictions does not exceed α. To achieve this principally, we introduce LEC, which reframes selective prediction not as an uncertainty-ranking problem, but as a decision problem governed by a statistical constraint. The central idea is to express FDR control as a constraint on the expectation of a linear functional involving two binary indicators: one capturing whether a prediction is selected and the other indicating whether it is incorrect. This formulation enables us to establish a finite-sample sufficient condition utilizing calibration uncertainty scores and error labels that, if satisfied, guarantees FDR control for unseen test samples. Since this condition depends only on the empirical quantities from the calibration set, it yields a calibrated threshold that maximizes coverage subject to the FDR constraint.

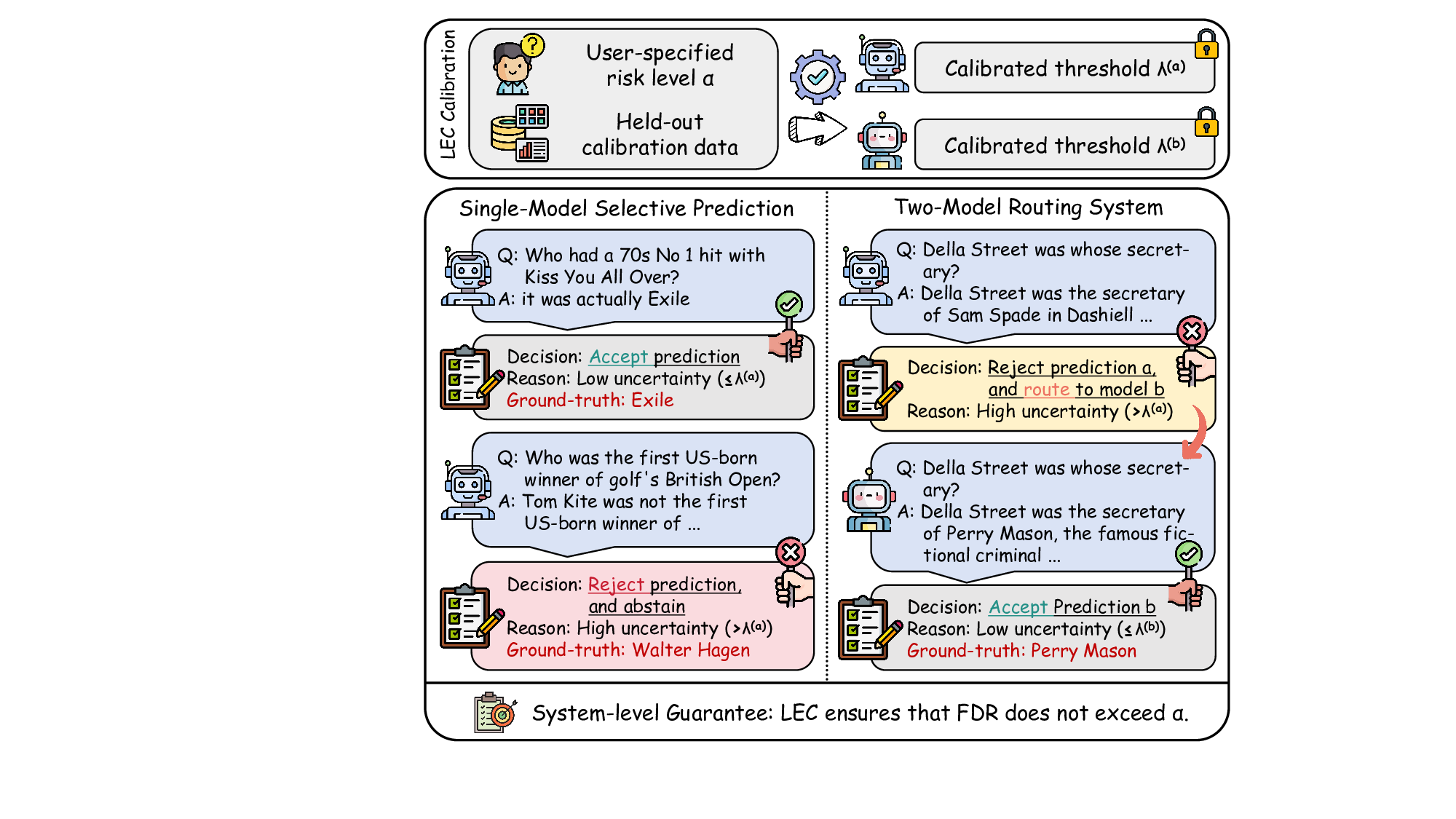

We further extend LEC to a two-model routing framework. For each input, the system accepts the current model’s prediction if its uncertainty falls below a calibrated threshold; otherwise, the input is routed to the subsequent model. If neither model satisfies its acceptance criterion, the system abstains. To preserve statistical guarantees, we impose a linear expectation constraint on the system-level selection and error indicators, which enables joint calibration of modelspecific thresholds with unified FDR control. Figure 1 illustrates examples of selective prediction in single-model and two-model routing systems, where uncertainty serves as the decision signal for accepting, routing, or abstaining.

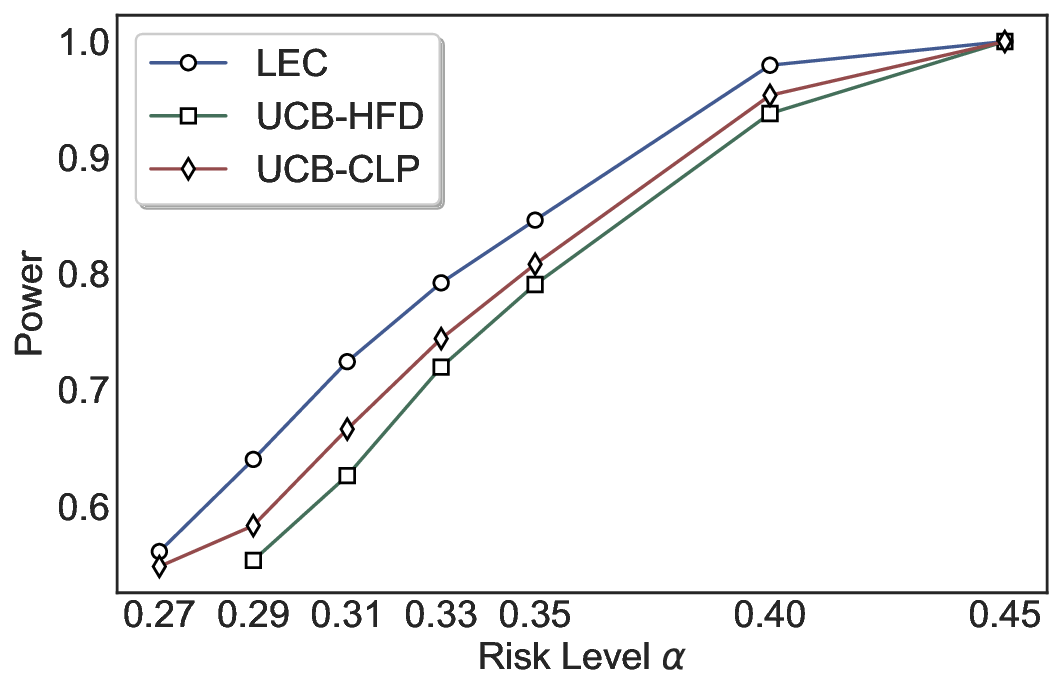

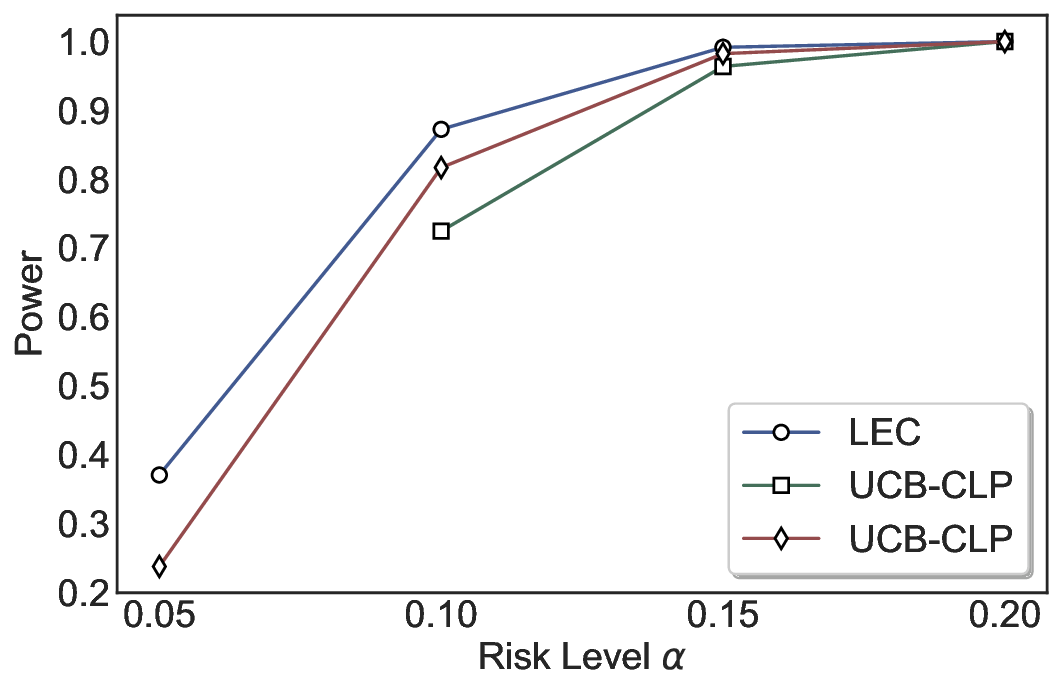

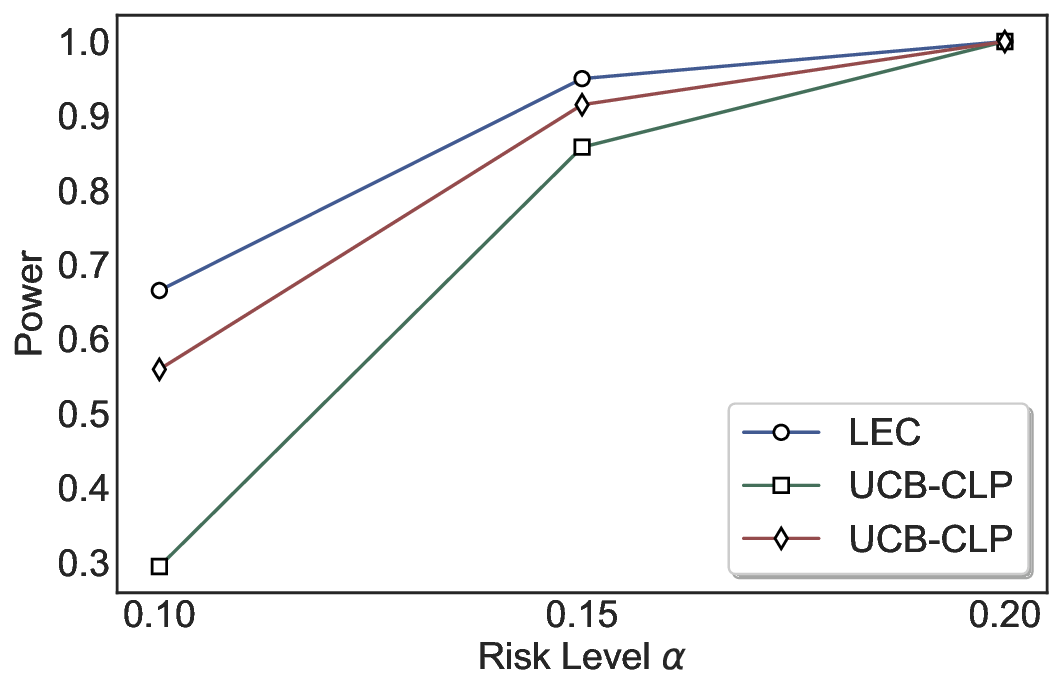

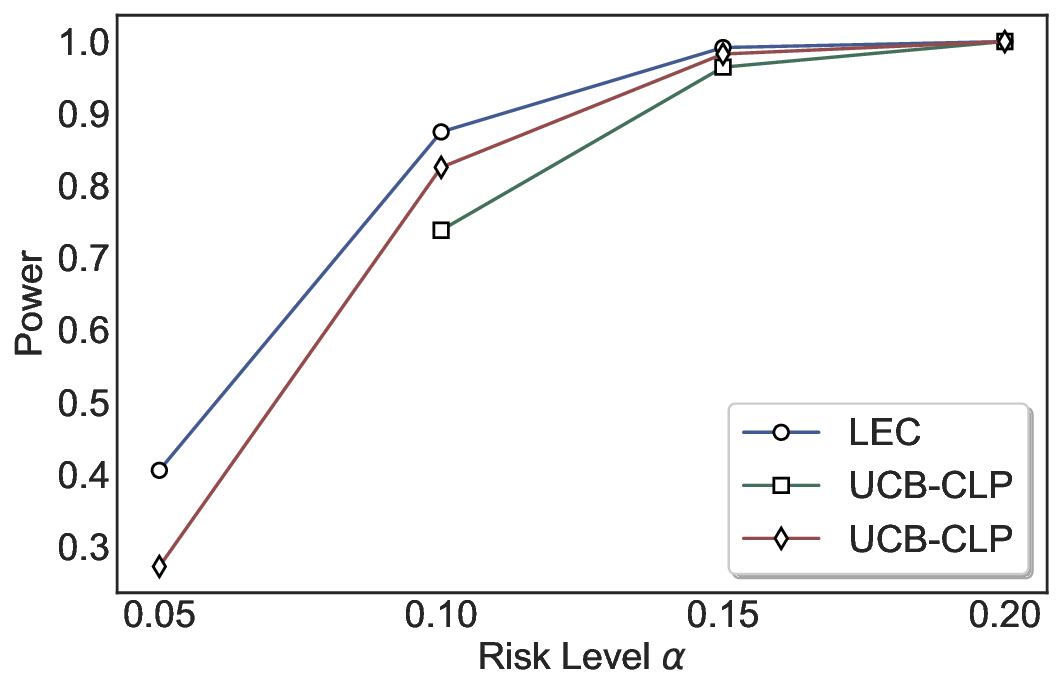

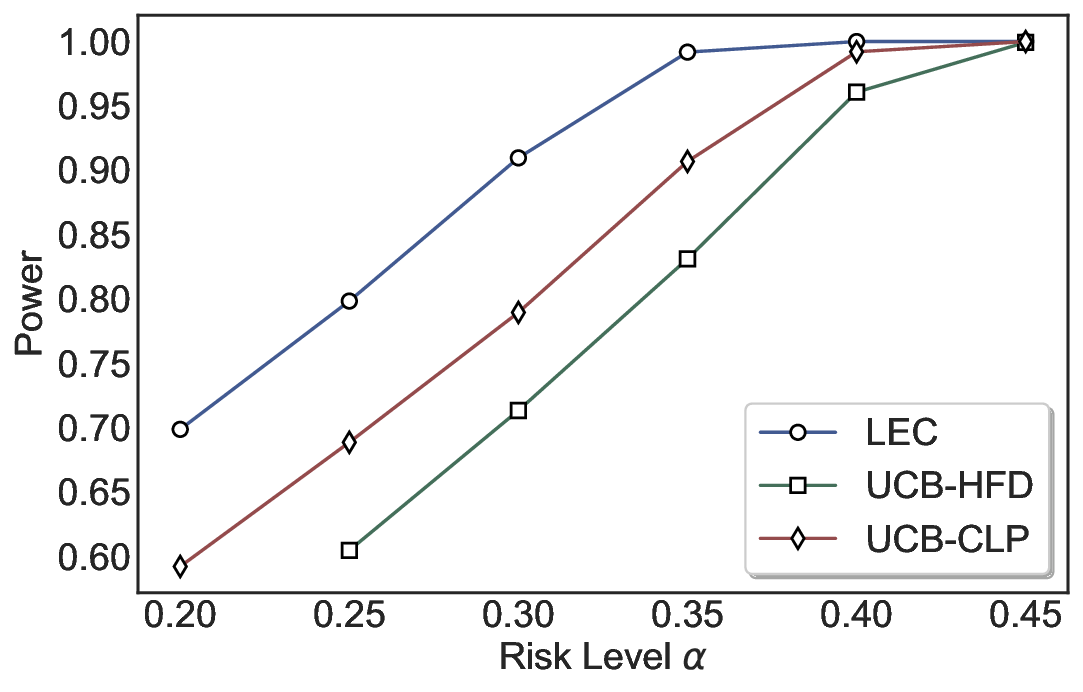

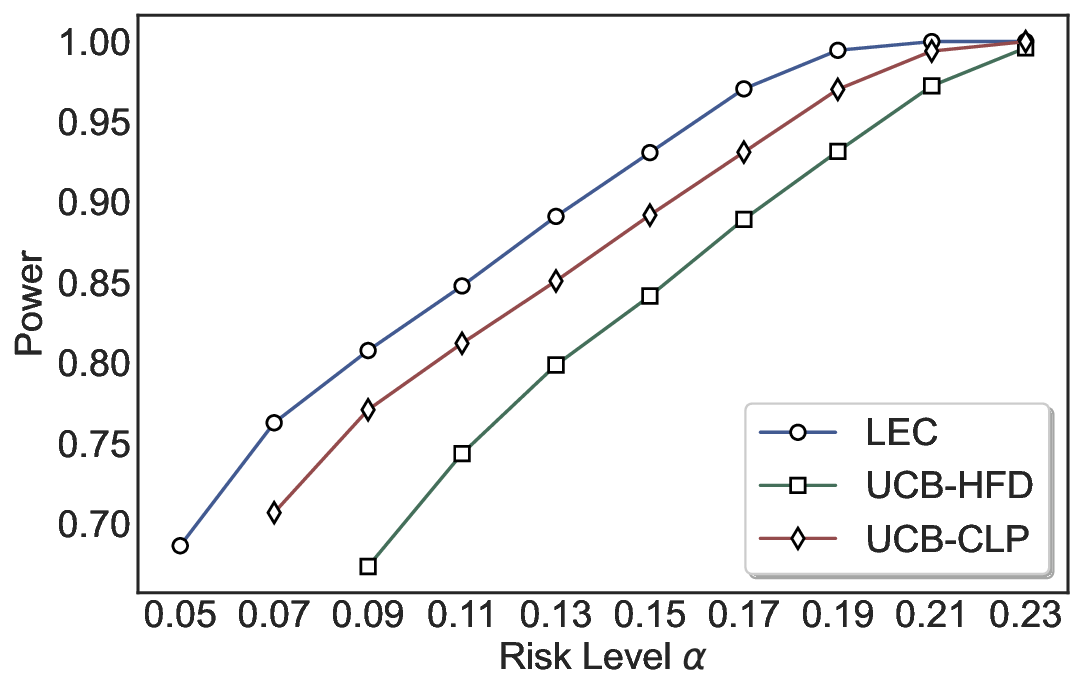

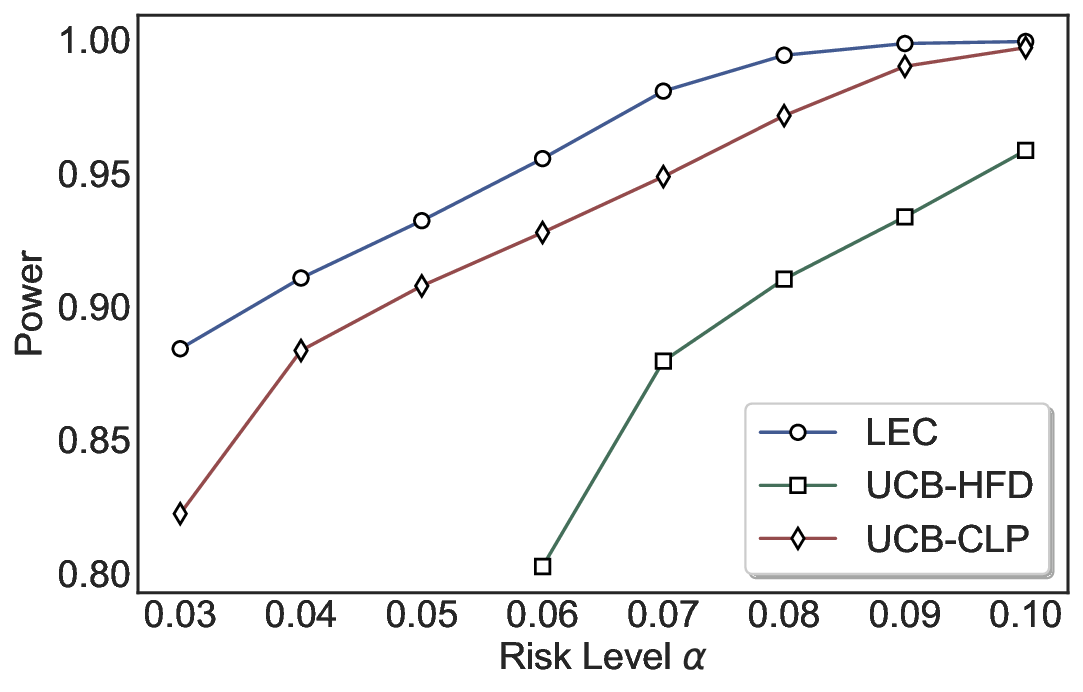

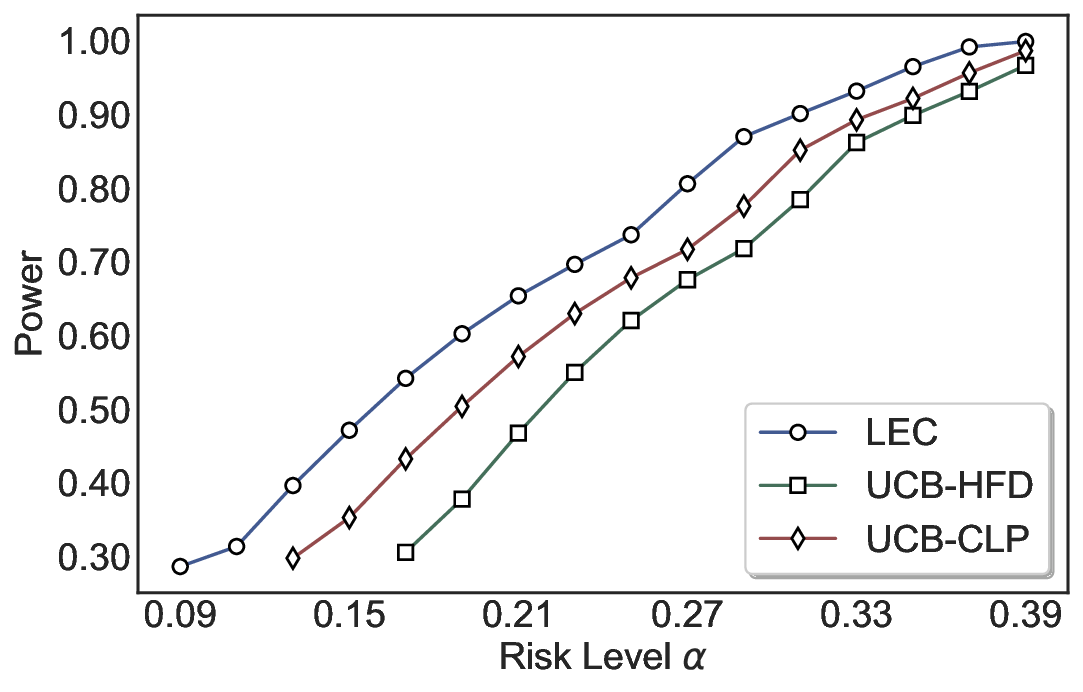

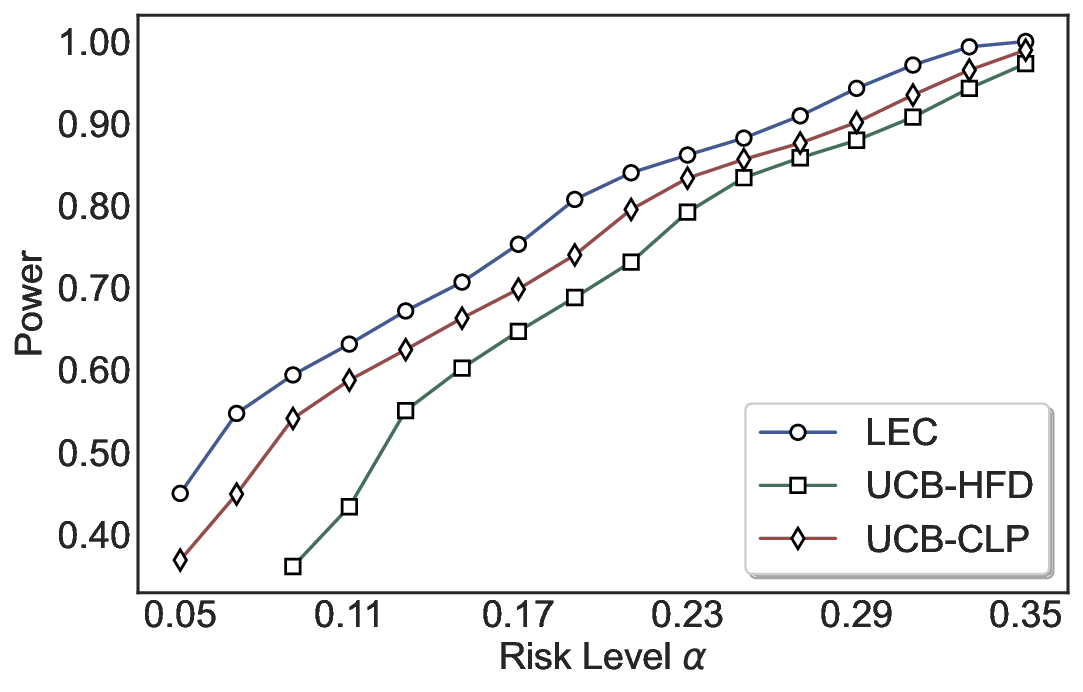

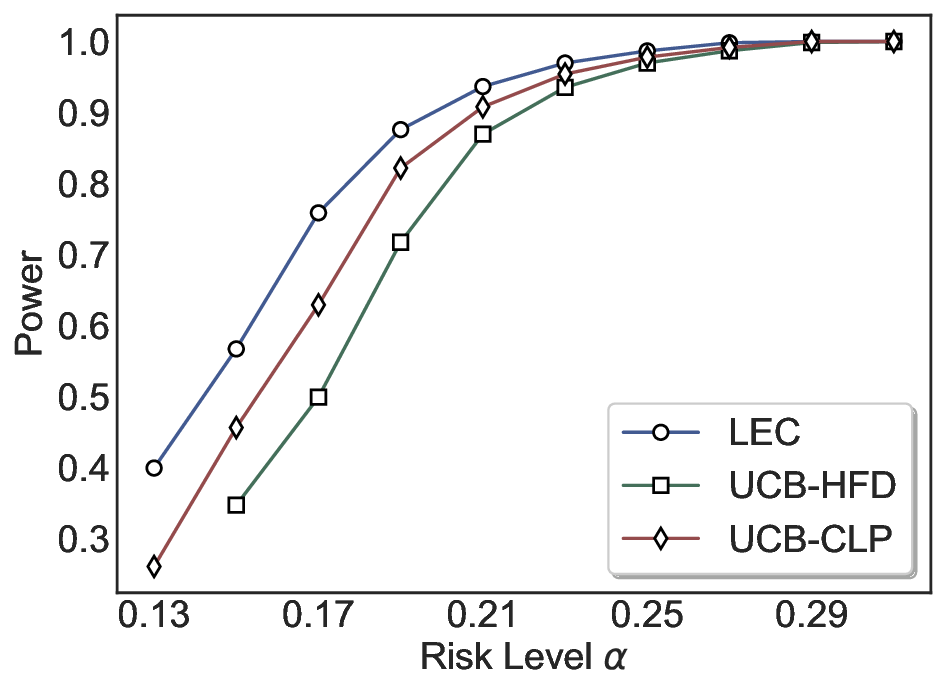

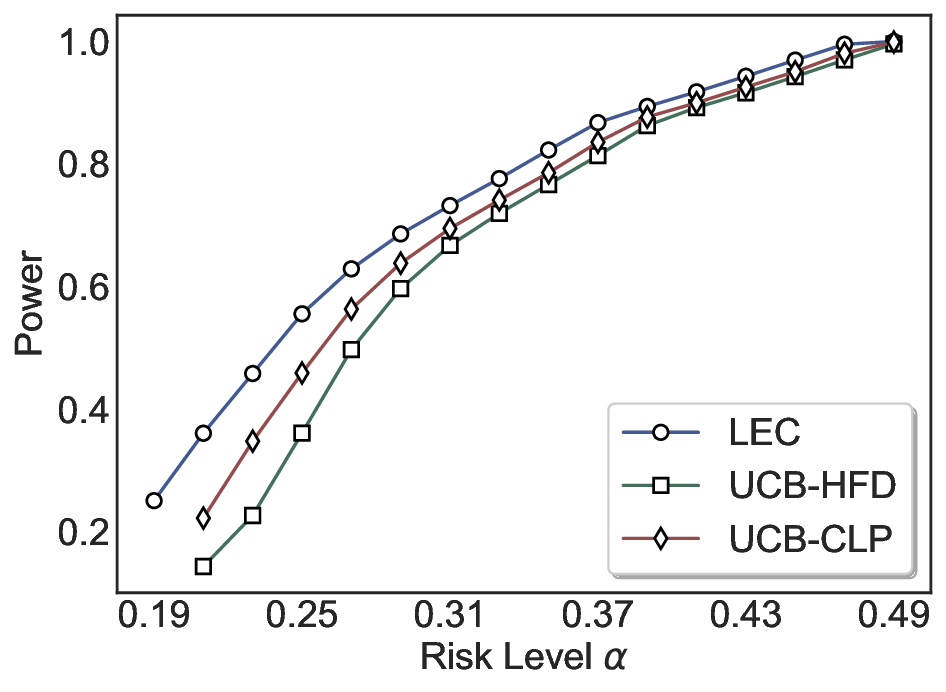

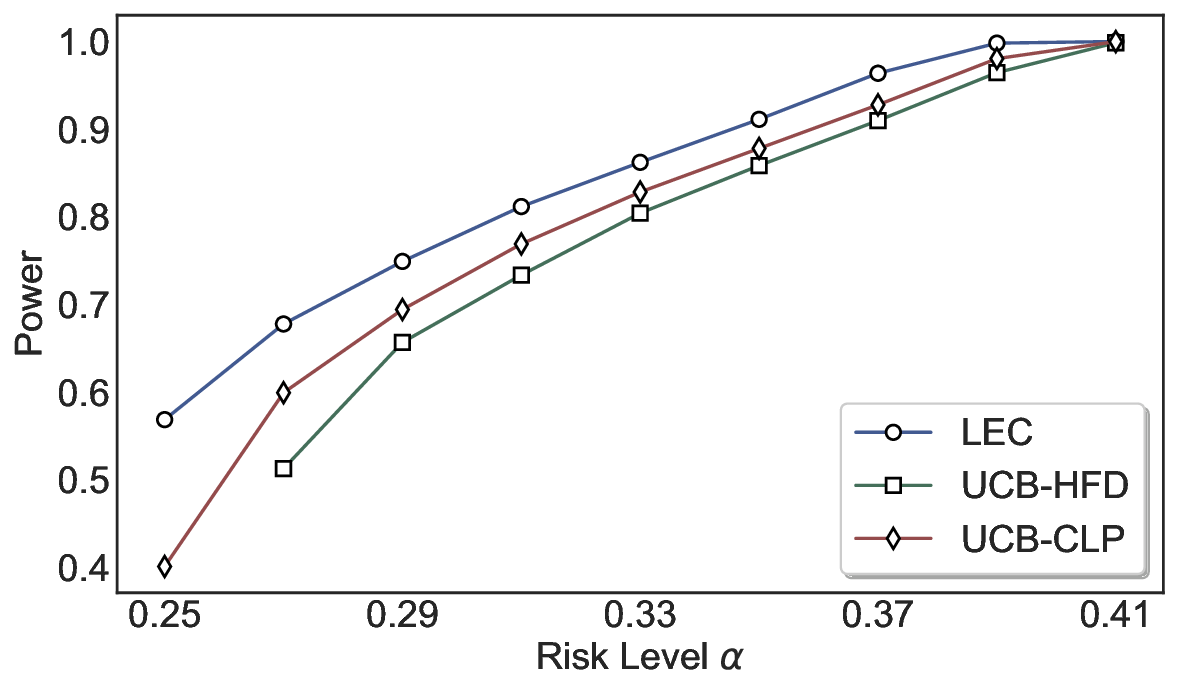

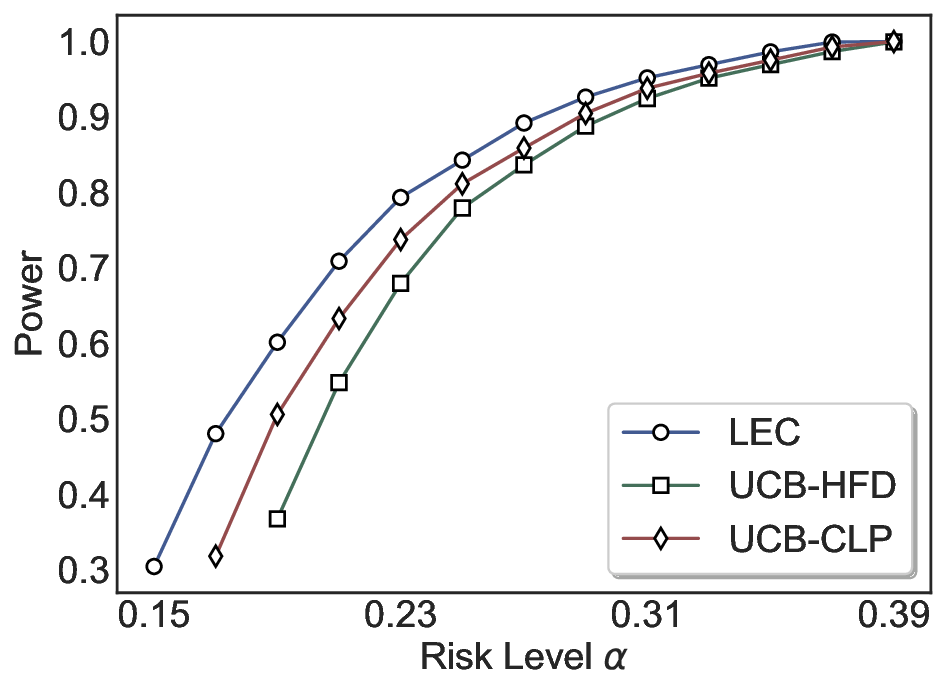

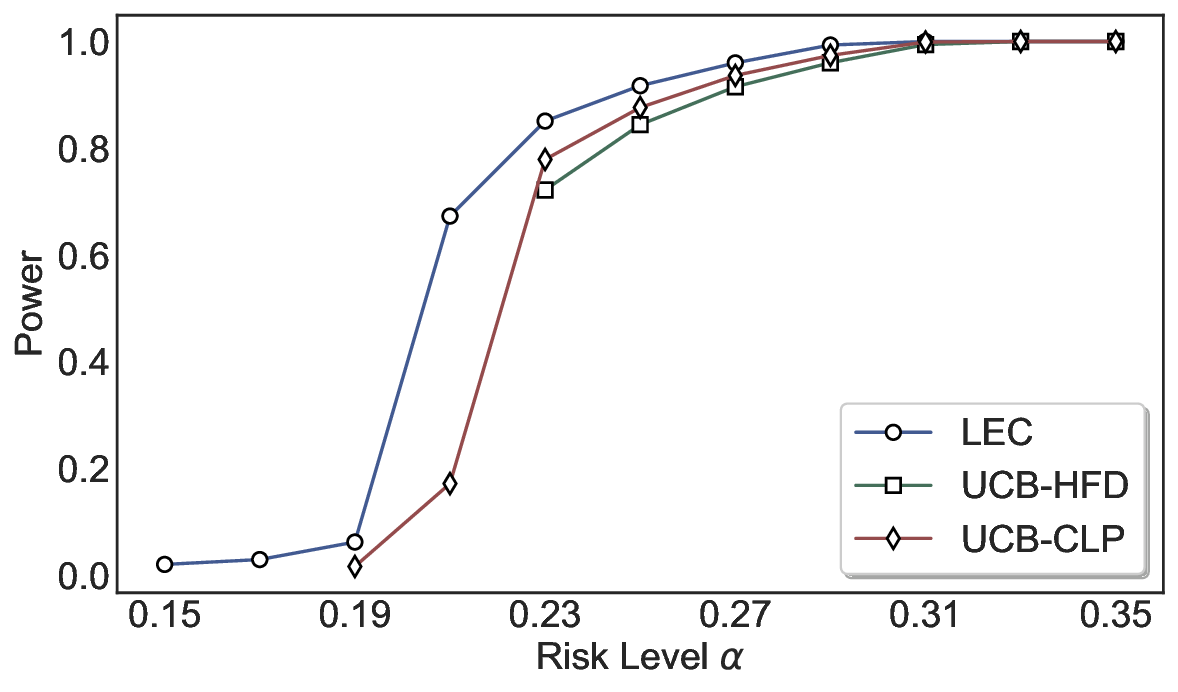

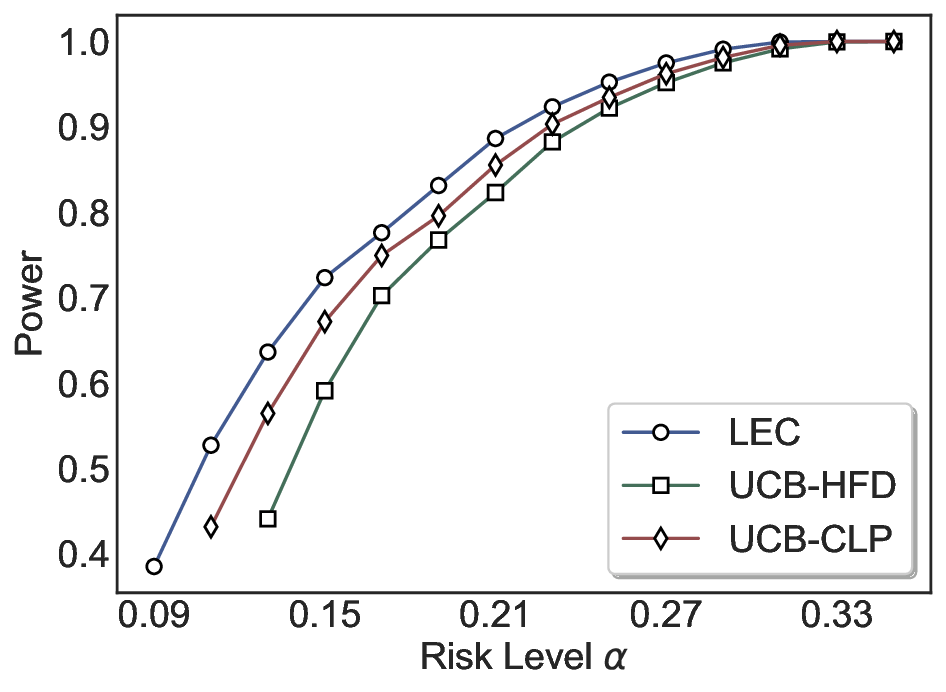

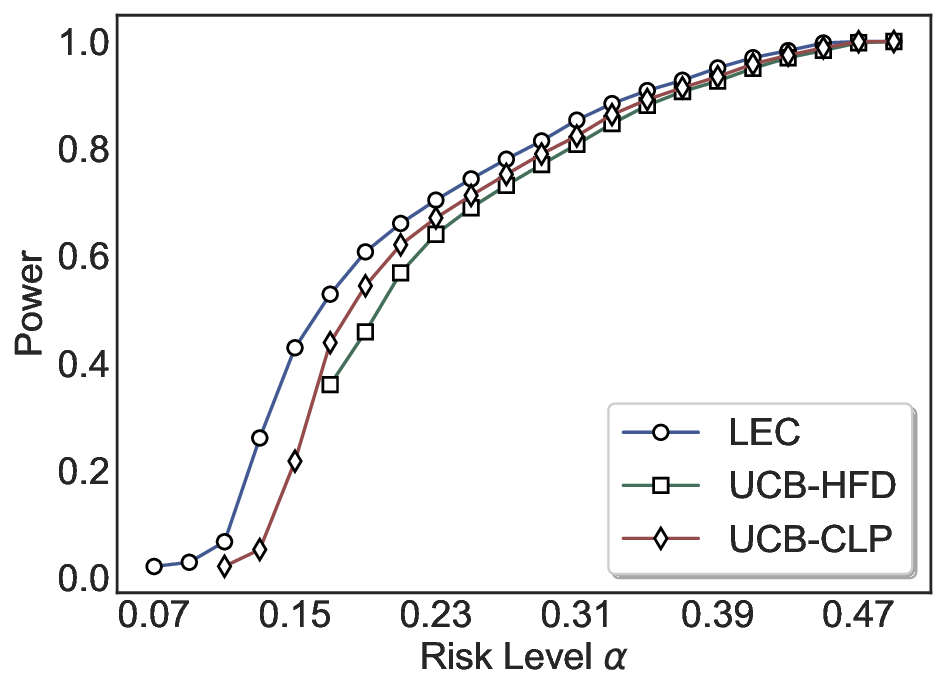

We evaluate LEC on four benchmarks across closed-ended and open-ended generation settings. In selective prediction of both single-model and two-model routing systems, LEC rigorously controls test-time FDR at various feasible risk levels. Compared to confidence interval-based methods (Wang et al., 2025c;Jung et al., 2025), LEC establishes a tighter risk bound while accepting more admissible samples (e.g., +9% on TriviaQA). Furthermore, across different UQ methods, admission functions, calibration-test split ratios, and sampling sizes under black-box scenarios, LEC maintains statistical rigor while consistently achieving higher power than the best baseline. These results highlight the practical effectiveness and generality of LEC, motivating its integration into real-world uncertainty-aware agentic systems.

SCP in LLMs. SCP provides statistical guarantees of coverage for correct answers (Campos et al., 2024b). It evaluates the nonconformity (or residual) between model prediction and ground-truth on a calibration set, and then computes a rigorously calibrated threshold, which is applied to construct prediction/conformal sets at test time. Under exchangeability (Angelopoulos et al., 2023), these sets contain admissible answers with at least a user-specified probability. However, previous research predominantly focuses on set-valued predictions (Quach et al., 2024;Kaur et al., 2024;Wang et al., 2024b;2025b;a), which are not inherently actionable due to unreliable candidates, and can cause disparate impact (Cresswell et al., 2024;2025). Our work targets FDR control over accepted point predictions, rather than conformal coverage.

FDR Control in Selective Prediction. Several frameworks grounded in significance testing (Jin & Candès, 2023;2025) and confidence intervals (Bates et al., 2021) have been introduced for FDR control on accepted answers. For instance, conformal alignment (Gui et al., 2024) and labeling (Huang et al., 2025) calculate conformal p-values and control Type I error (i.e., FDR) in multiple hypothesis testing. To retain more admissible answers and accelerate test-time inference, COIN (Wang et al., 2025c) constructs an upper confidence bound (UCB) for the system risk on calibration data and computes a rigorous threshold for test-time selection, achieving PAC-style FDR control (Park et al., 2020). Furthermore, Trust of Escalate (Jung et al., 2025) guarantees human agreement of cascaded LLM judges through Clopper-Pearsonstyle UCB (UCB-CLP) computation (Clopper & Pearson, 1934). In contrast to UCB-based methods that implicitly enforce worst-case tail control, LEC directly constrains the expectation of a linear functional of selection and error indicators, yielding tighter yet still statistically valid solutions.

Let G (a) : X → Y denote a pretrained model that maps an input prompt to a textual output. For a given prompt x ∈ X with an unknown ground-truth answer y * ∈ Y, the model produces a prediction ŷ(a) = G (a) (x) ∈ Y. We quantify the model’s uncertainty for x as u (a) = U(x; G (a) ), where U(•) denotes a scalar uncertainty function. Intuitively, small u (a) indicates high trustworthiness in ŷ(a) . For a specified threshold λ (a) , the prediction ŷ(a) is deemed admissible and accepted if u (a) ≤ λ (a) . Let the admission function be

However, prior uncertainty methods are inherently imperfect and cannot fully separate correct from incorrect outputs (Liu et al., 2025). Thus, applying a fixed λ (a) at test time may admit some erroneous predictions. To mitigate this issue, our goal is to derive a statistically rigorous threshold λ(a) that ensures the probability of accepting incorrect predictions (i.e., the FDR) does not exceed a target risk level α.

Formally, we define the selection indicator as S (a) λ (a) = 1 u (a) ≤ λ (a) , and the corresponding error indicator as err (a) = 1 A(y * , ŷ(a) ) = 0 . Our objective is to calibrate a statistically valid threshold λ(a) such that

- Two-Model Routing with FDR Control Under a specific uncertainty function U(•), the uncertainty scores of model G (a) on test data may cluster too tightly in a low range, making it impossible to achieve small target risk levels. Moreover, when G (a) has limited predictive ability (e.g., low accuracy), many challenging or critical prompts may be abstained from, leading to reduced system efficiency.

To alleviate these issues, we develop a collaborative routing mechanism that dynamically delegates uncertain samples to another model with stronger accuracy or a more discriminative uncertainty profile, while controlling the system FDR.

Formally, we define the alternative model as G (b) : X → Y.

For a given prompt x, when the estimated uncertainty u (a) exceeds λ (a) , we route the prompt to G (b) . We denote the prediction of b) , we trust ŷ(b) ; otherwise, the two-model routing system abstains from the prompt x. We define the selection indicator of model G (b) as b) , and the error indicator as err

The two-model routing system G integrates G (a) and G (b) , with the system-level selection indicator

and the error indicator conditioned on selecting either output

When S(λ (a) , λ (b) ) = 1, the prediction from either G (a) or G (b) is accepted. We aim to jointly calibrate (λ (a) , λ (b) ) and obtain statistically rigorous thresholds ( λ(a) , λ(b) ) such that

This guarantees that the overall two-model routing system performs selective prediction at test time with FDR control.

We begin by describing how to calibrate a statistically valid threshold λ(a) for G (a) . Following the standard split calibration protocol (Papadopoulos et al., 2002), the dataset is partitioned into a calibration set and a test set. The threshold is learned solely from the calibration data for a user-specified risk level α, and is then fixed during test-time evaluation.

From FDR control to linear expectation constraint. For a fixed threshold λ (a) , recall the selection and error indicators S (a) (λ (a) ) and err (a) . We further define the joint indicator as Z (a) (λ (a) ) = S (a) (λ (a) ) • err (a) , which equals 1 if and only if we accept the prediction and the model errs. The FDR can then be reformulated as

.

(3)

As long as E[S (a) (λ (a) )] > 0, FDR (a) (λ (a) ) ≤ α is equivalent to a constraint on the expectation of a linear functional of random variables (over selection and error indicators)

Intuitively, the random variable Z (a) -αS (a) measures error count minus α times selection count on a single example; if its expectation is non-positive, then the conditional error rate among accepted predictions (i.e., FDR) does not exceed α.

Finite-sample sufficient condition. To enforce the population constraint in Eq. ( 4) using only the calibration data, we then derive a finite-sample condition. Let the calibration set be

i , err

(n) denote the calibration uncertainty scores sorted in ascending order, with corresponding error indicators err (a) (j) . For a candidate threshold λ (a) , we define

as the number of calibration data points that would be accepted at the threshold of λ (a) . Then, a standard “+1” correction, which ensures validity under exchangeability and avoids degeneracy when all accepted examples happen to be correct, yields the following finite-sample sufficient condition (see Appendix A.1 for complete derivation):

(5)

We then define the feasible set of thresholds at level α as

Calibrated Coverage-Maximizing Threshold. Among all thresholds in set Λ (a)

α , we choose the largest feasible one to maximize the acceptance coverage: a) :

α is empty, we declare the target risk level α infeasible for G (a) and abstain from all samples at this level. Theorem 3.1 (Single-model FDR control). Assume that calibration and test examples are exchangeable (Angelopoulos et al., 2023). Let λ(a) be defined by Eq. (7) using D cal . Then, for a new test sample (x n+1 , y * n+1 ) with (u

Pr err

n+1 ≤ λ(a) ≤ α, where the probability is taken over the joint randomness of the calibration set and the test sample (marginal guarantee).

A complete proof of Theorem 3.1 is given in Appendix A. n+1 ≤ λ(a) ; otherwise, we abstain.

We now extend the above calibration procedure to the twomodel routing system G. For each example i, we observe uncertainties (u a) , λ (b) ) ∈ {0, 1}, and the error indicator conditioned on accepting either output is

, which remains binary because routing selects at most one prediction. We also define the system-level joint indicator as

From system-level FDR control to expectation constraint.

The system FDR at thresholds (λ (a) , λ (b) ) is

.

Whenever E[S(λ (a) , λ (b) )] > 0, FDR(λ (a) , λ (b) ) ≤ α is also equivalent to a linear expectation inequality

This condition generalizes the single-model constraint to the routing system and again captures the difference between the system-level error count and α-fraction of accepted samples.

Finite-sample sufficient condition. To enforce Eq. ( 8) from calibration points, we also construct an empirical sufficient condition. Let D sys cal = {(u

i , err

i )} n i=1 denote the calibration set for the two-model routing system. By applying the same “+1 smoothing” argument to the pair (Z i , S i ), we establish the finite-sample sufficient condition

We then obtain the feasible set of two-model threshold pairs

Calibrated coverage-maximizing thresholds. Among all pairs (λ (a) , λ (b) ) ∈ Λ (a,b) α , we choose those that maximize the empirical acceptance coverage of the routing system:

is empty, the risk level α is infeasible for the twomodel routing system, and the system abstains on all inputs. Theorem 3.2 (FDR control for the two-model routing system). Assume calibration and test examples are exchangeable. Let ( λ(a) , λ(b) ) be any solution of Eq. (11). Then the two-model routing system satisfies

where the probability is taken over the joint randomness of calibration and test samples (marginal guarantee). n+1 ≤ λ(b) . If neither condition is satisfied, the system abstains. Our analysis highlights that FDR control is preserved as long as the routing policy is deterministic and each example is routed to at most one model. The statistical guarantees arise from the linear decomposition, rather than any model-specific assumptions.

The above two-model calibration can readily be extended to routing systems with more than two models. In Appendix B, we outline how LEC extends to general multi-model routing systems, offering a principled mechanism for unified FDR control across routing policies of arbitrary depth; exploring this broader setting empirically is left for future work.

Benchmarks and Models. (1) QA: We evaluate LEC on the CommonsenseQA (closed-ended) (Talmor et al., 2019) and TriviaQA (open-ended) (Joshi et al., 2017) datasets using eight LLMs, including LLaMA (Touvron et al., 2023), Qwen (Bai et al., 2023), Vicuna (Zheng et al., 2023), and OpenChat (Wang et al., 2024a) families. (2) VQA: We also consider the ScienceQA (closed-ended) (Lu et al., 2022) and MM-Vet v2 (open-ended) (Yu et al., 2024) benchmarks, using four LVLMs, including LLaVA1.5 (Liu et al., 2023), LLaVA-NeXT (Liu et al., 2024), and InternVL2 (Chen et al., 2024) groups. We omit suffixes such as “hf” and “Instruct”.

Evaluation Metrics. Following previous work (Jung et al., 2025;Wang et al., 2025c), we evaluate the statistical validity of LEC by verifying that test-time FDR does not exceed the target risk level. We further assess its power, defined as the proportion of admissible test samples it accepts among all admissible samples. In two-model routing, we also evaluated the proportion of samples accepted by the two models.

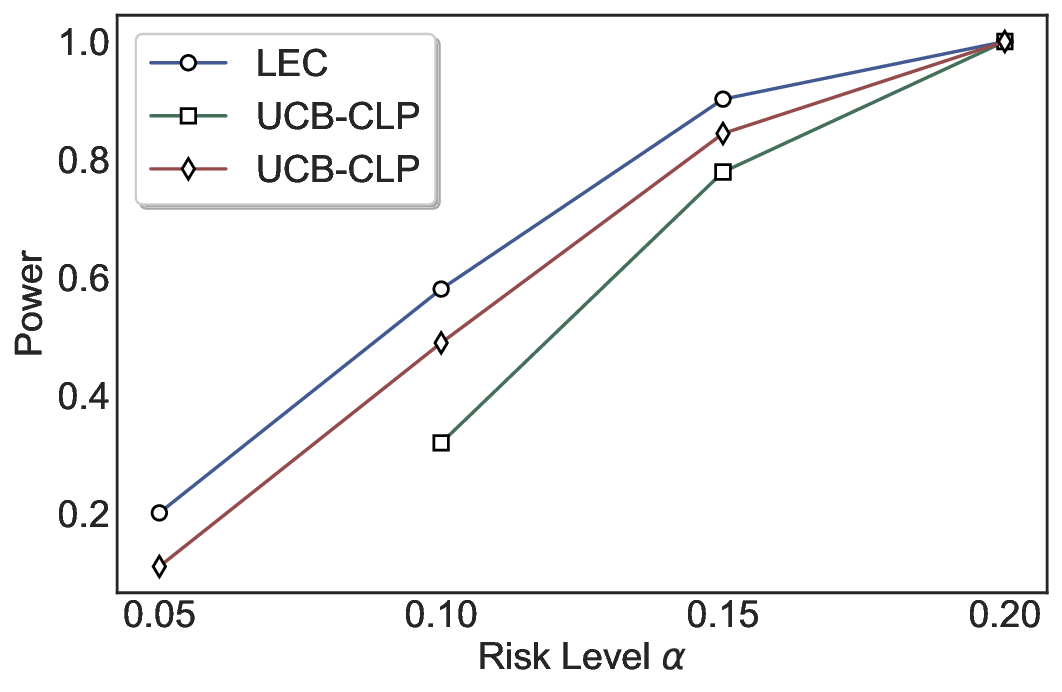

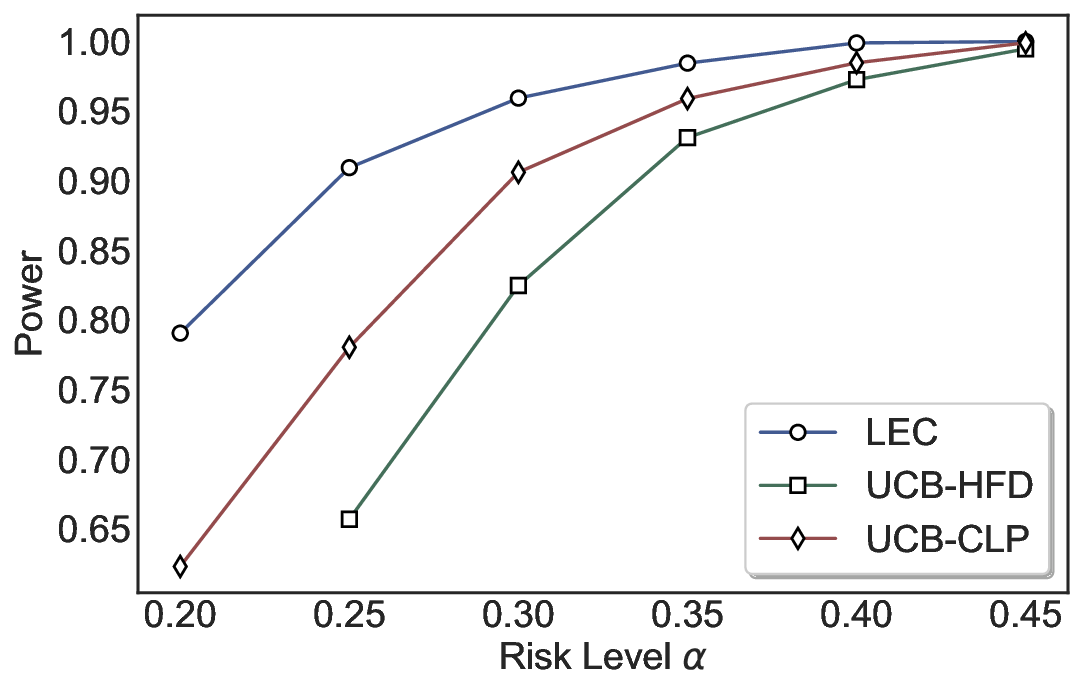

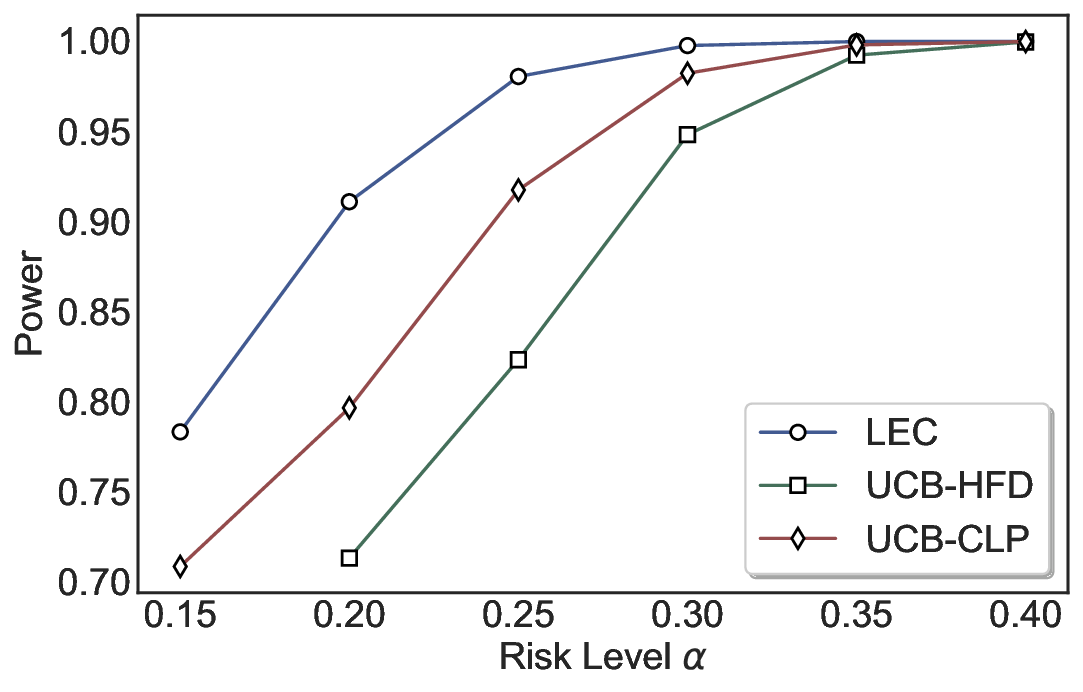

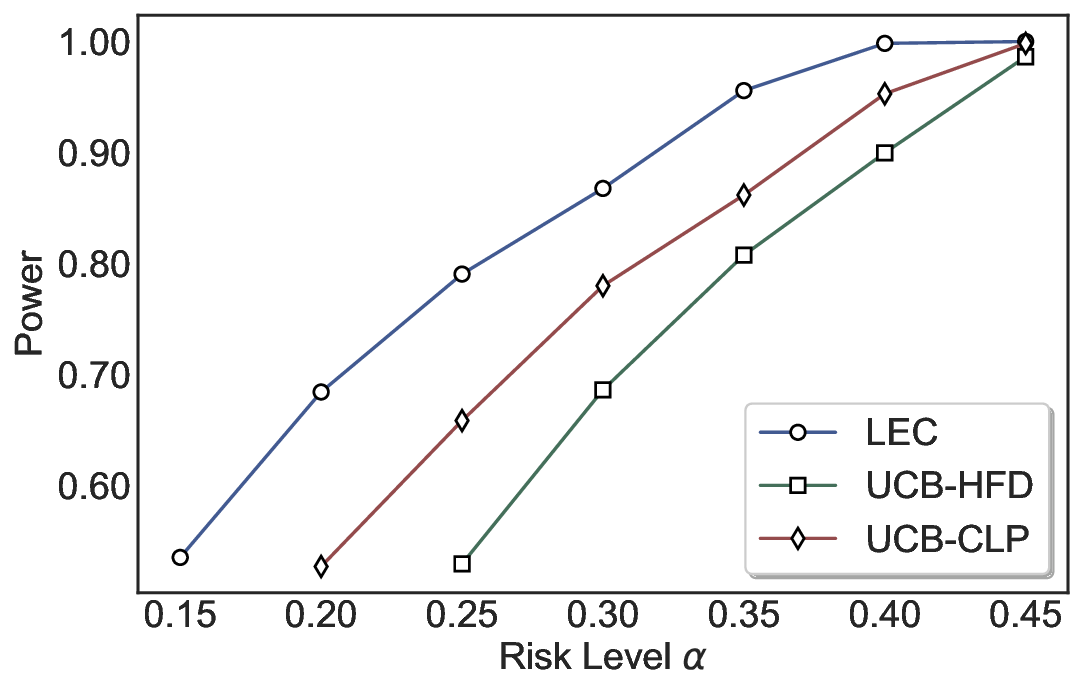

Baselines. 1) Single-model: We consider UCB-based methods that control FDR by computing UCBs on the system risk from calibration data. Specifically, we implement two variants: UCB-HFD, which derives the UCB using Hoeffding’s inequality (Hoeffding, 1963), and UCB-CLP, which adopts the exact Clopper-Pearson interval. These two vari-ants abstract the core FDR control mechanism used in prior single-model methods such as COIN (Wang et al., 2025c). 2) Two-model routing: We extend the UCB-based approach to the routing setting by applying the same confidence-boundbased risk control to the system-level selection and error indicators. We consider UCB-CLP-Routing, corresponding to the cascaded judge in Jung et al. (2025), as well as UCB-HFD-Routing, which replaces the Clopper-Pearson bound with Hoeffding’s inequality for a distribution-free variant. We do not consider routing with more than two models, as it only increases the number of threshold parameters and leads to nested threshold searches during calibration, without altering the formulation or its statistical guarantees.

Alignment Criteria. We use sentence similarity (Reimers & Gurevych, 2019b) with a 0.6 threshold to decide whether the model’s answer is aligned with the ground truth in the admission function A by default. We also use bi-entailment (Kuhn et al., 2023) and LLM-as-a-Judge (Zhang et al., 2024). 5LVN/HYHO )‘5

(e) Vicuna-13B-V1.5.

(e) Vicuna-13B-V1.5. Table 1. Power comparison on the TriviaQA dataset (mean).

Uncertainty Estimator U. In closed-ended QA and VQA, we estimate uncertainty scores by computing the predictive entropy (PE) (Kadavath et al., 2022). We use the softmax output of model logits by default. We also generate multiple answers per input and employ sampling frequency as the generative probability (Wang et al., 2025e). In open-ended QA and VQA, we compute the black-box semantic entropy (SE) (Farquhar et al., 2024) by default. Moreover, we use the sum of eigenvalues of the graph laplacian (EigV), degree matrix (Deg), and eccentricity (Ecc) (Lin et al., 2024). We also consider the length-normalized PE (Malinin & Gales, 2021) of the model’s output itself (SELF).

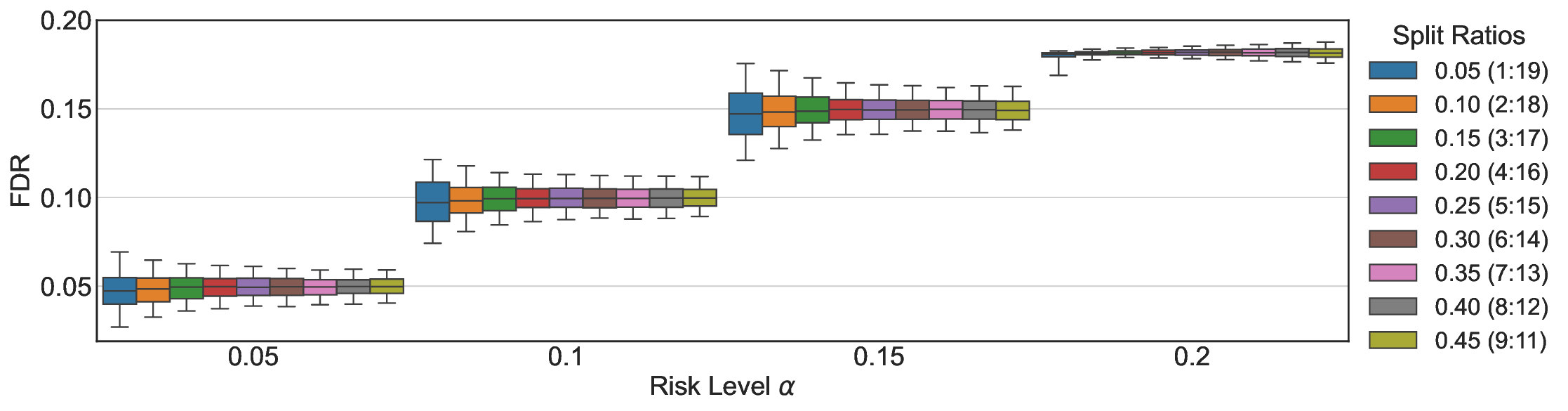

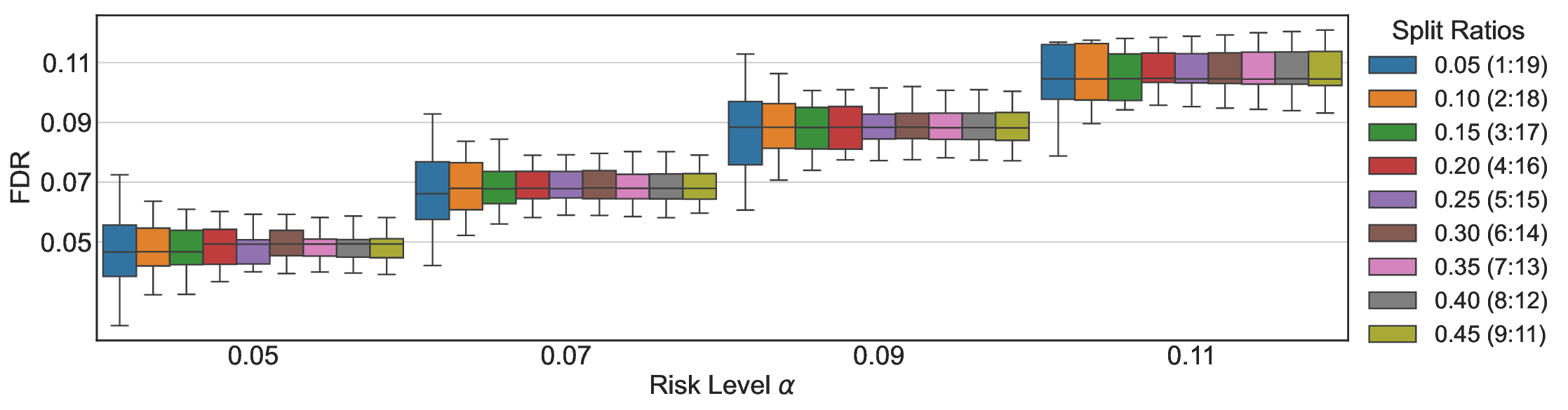

Hyperparameters. Following previous work (Wang et al., 2025c), we employ beam search (num beams=5) to obtain the most likely generation as the model output. By default, for open-domain QA, we sample 10 answers per input for UQ. In addition, we fix the calibration-test split ratio to 0.5.

We provide the details of additional experimental settings in Appendix C. Following prior research (Quach et al., 2024), we randomly split the calibration and test samples 500 times and report the mean and standard deviation (mean±std). We annotate this information alongside the subsequent results.

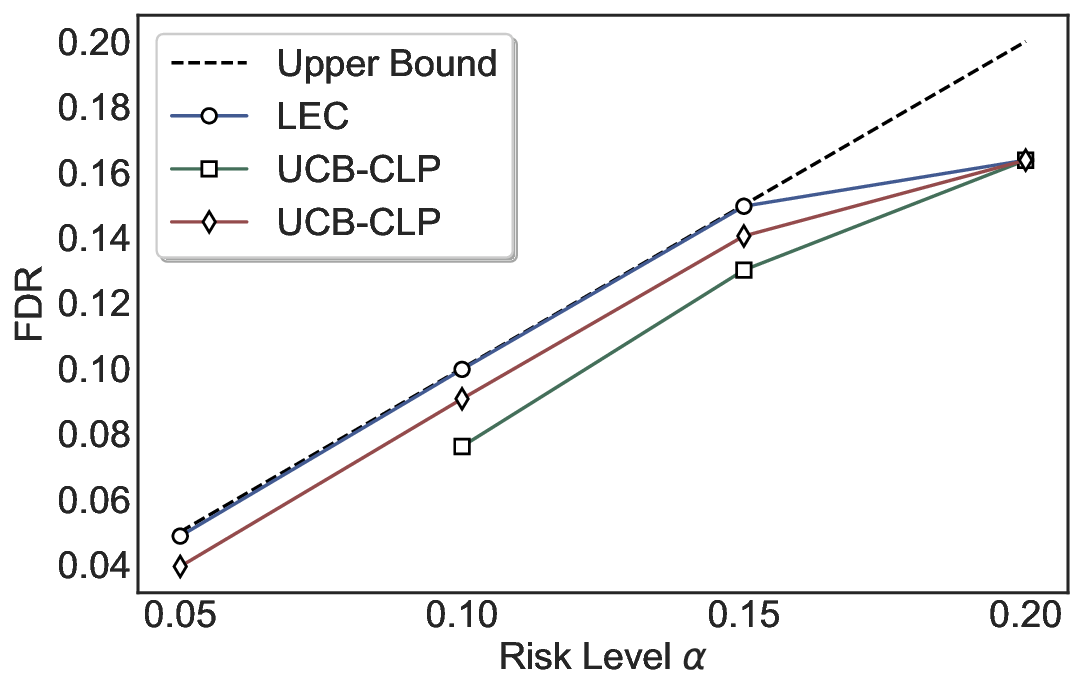

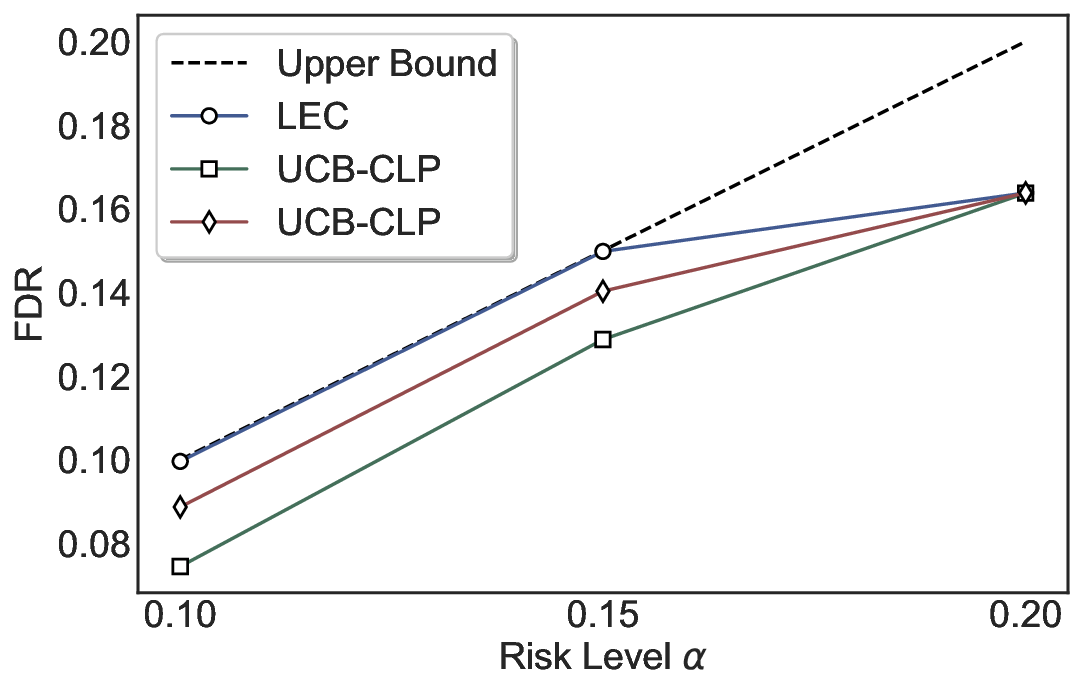

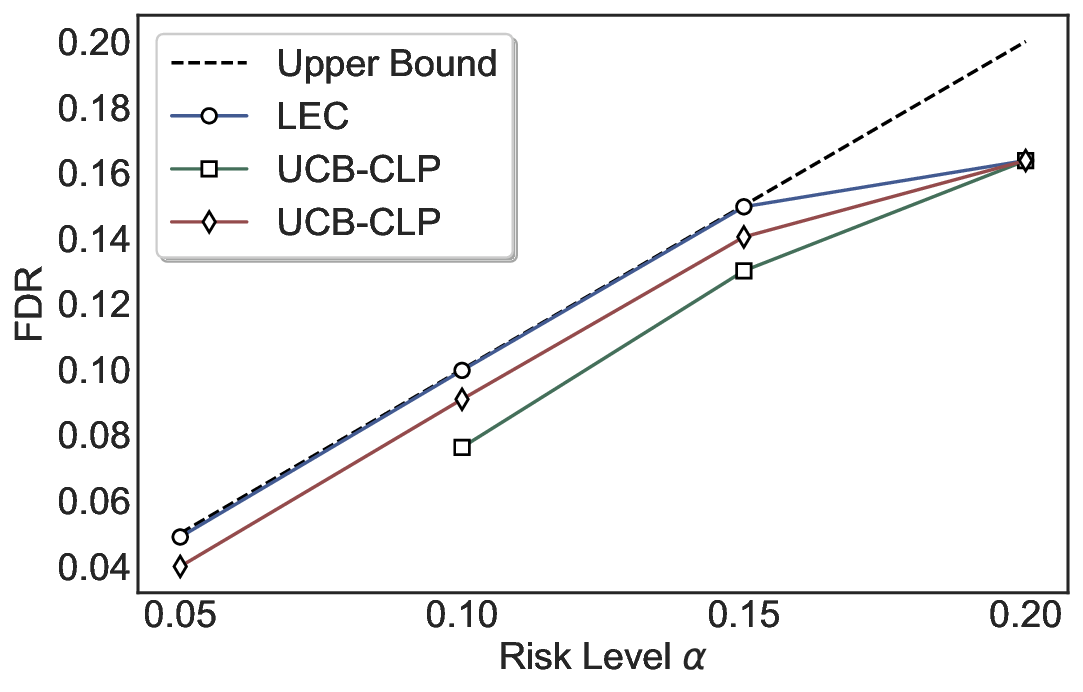

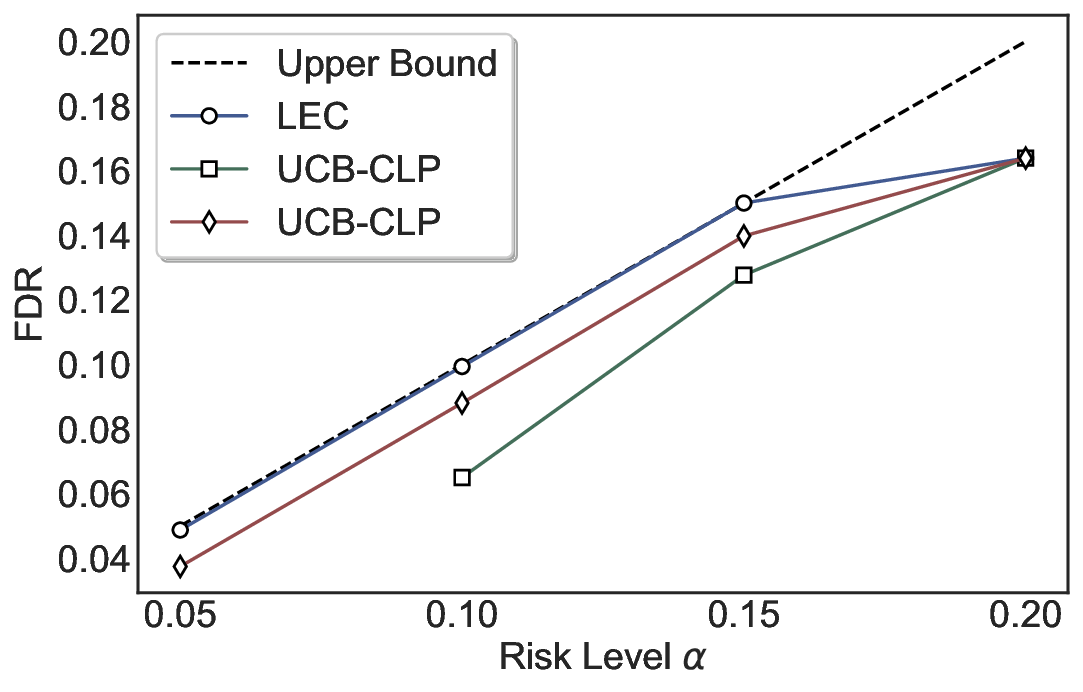

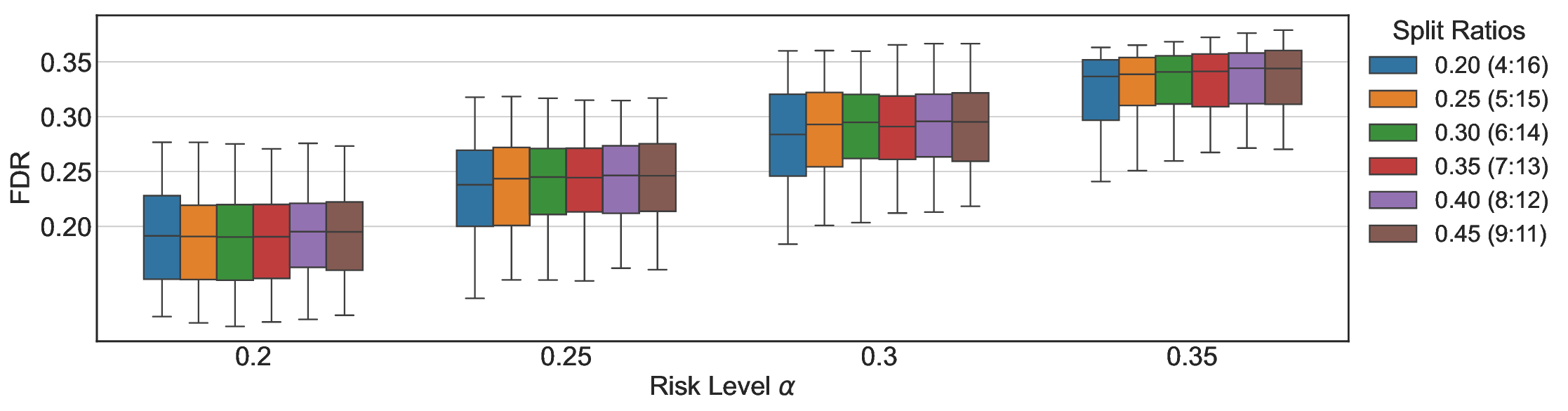

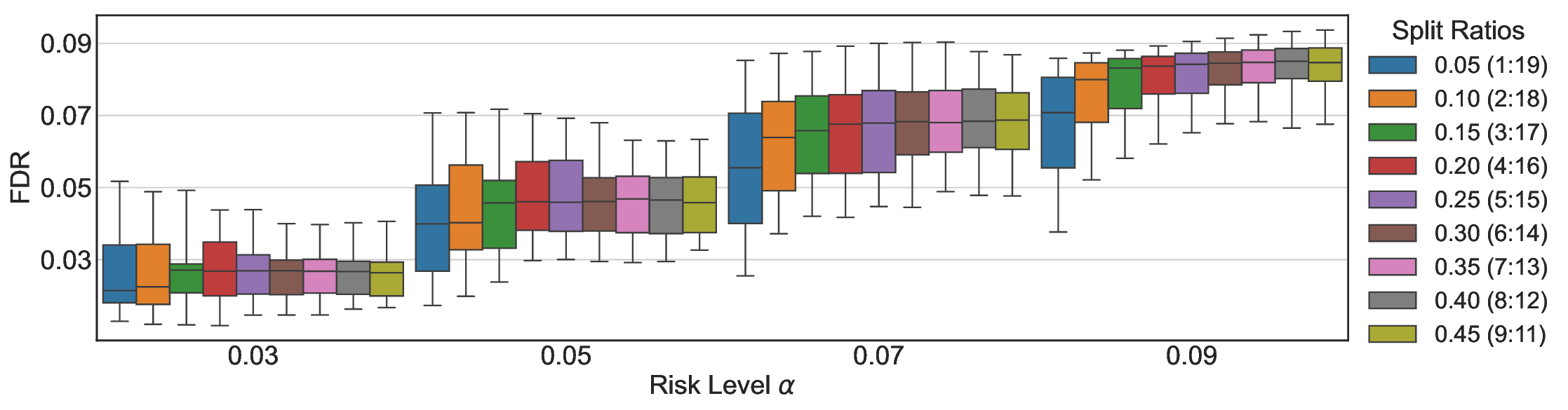

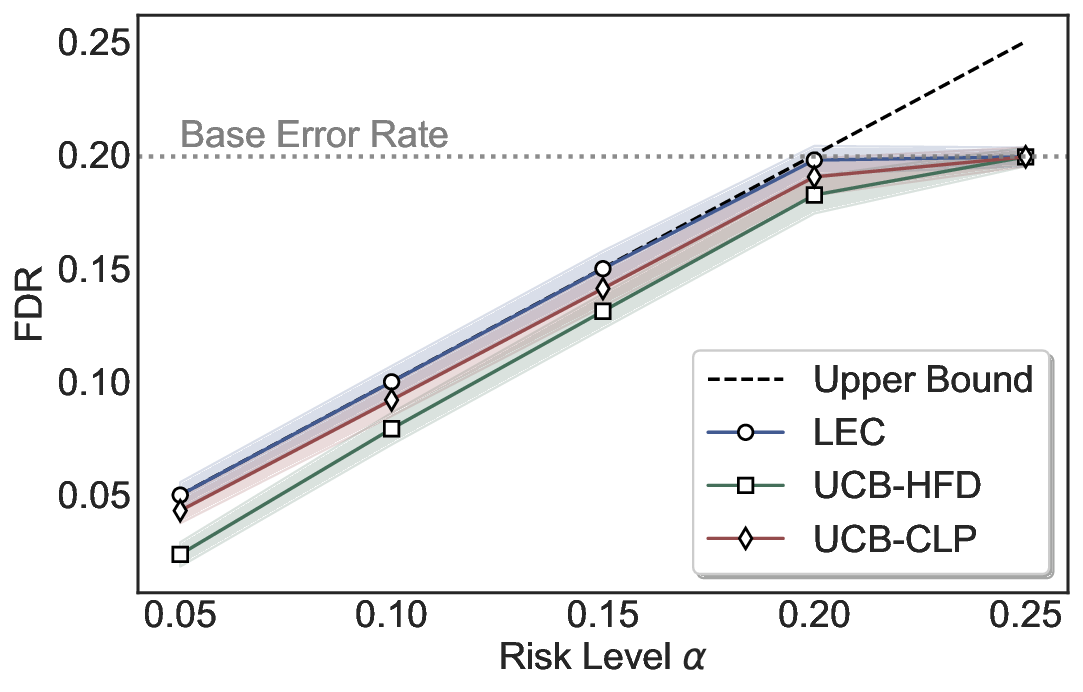

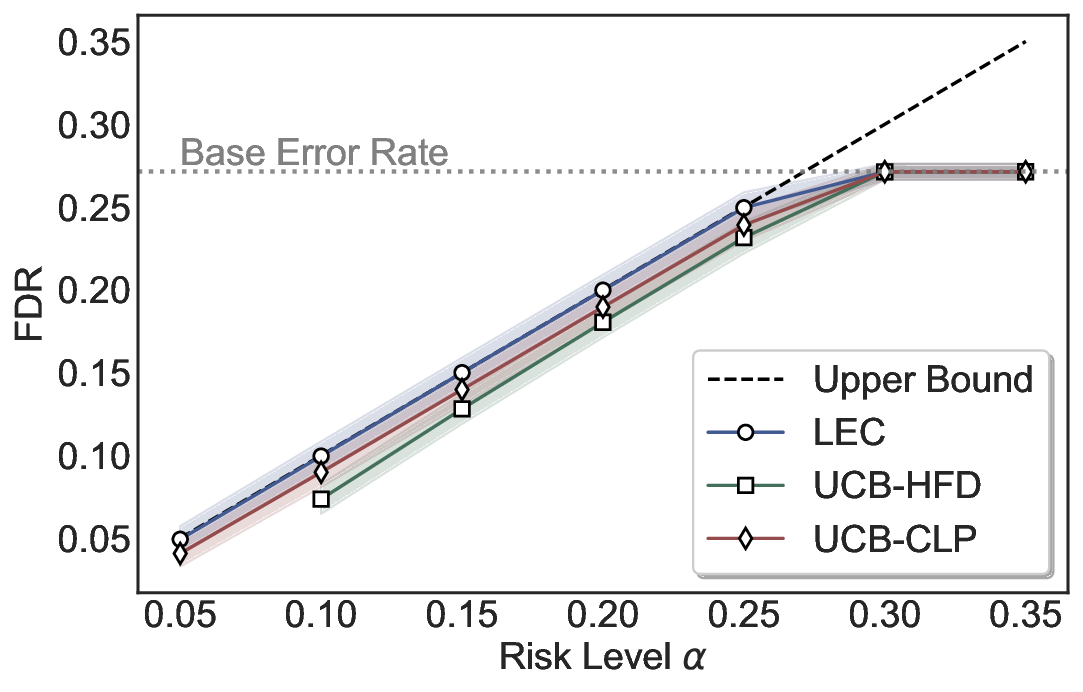

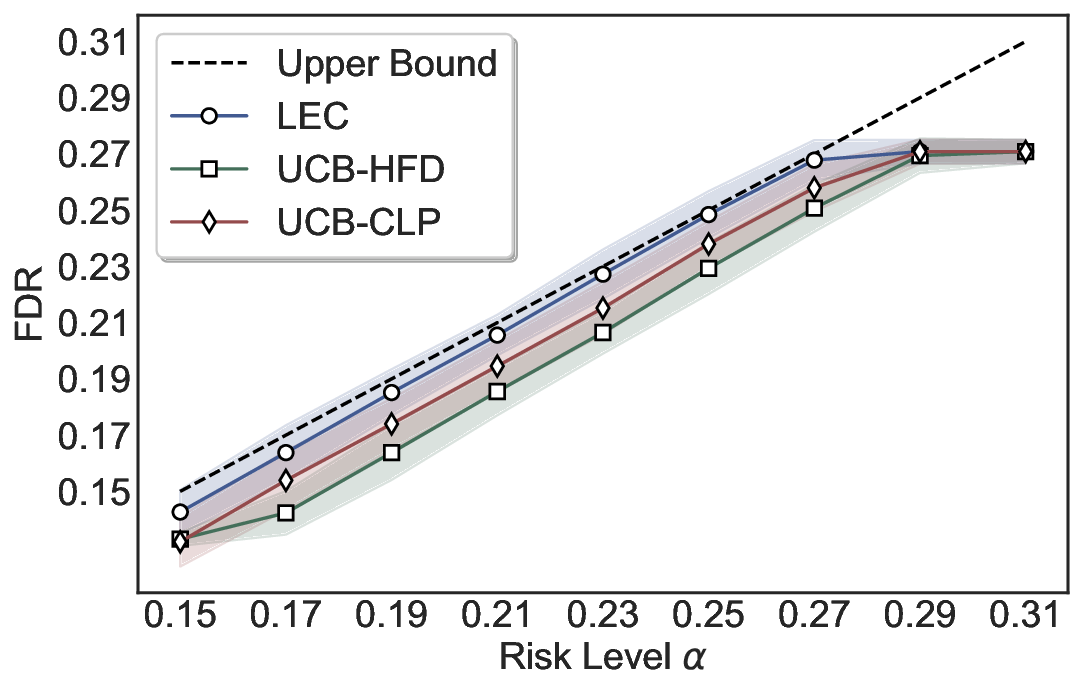

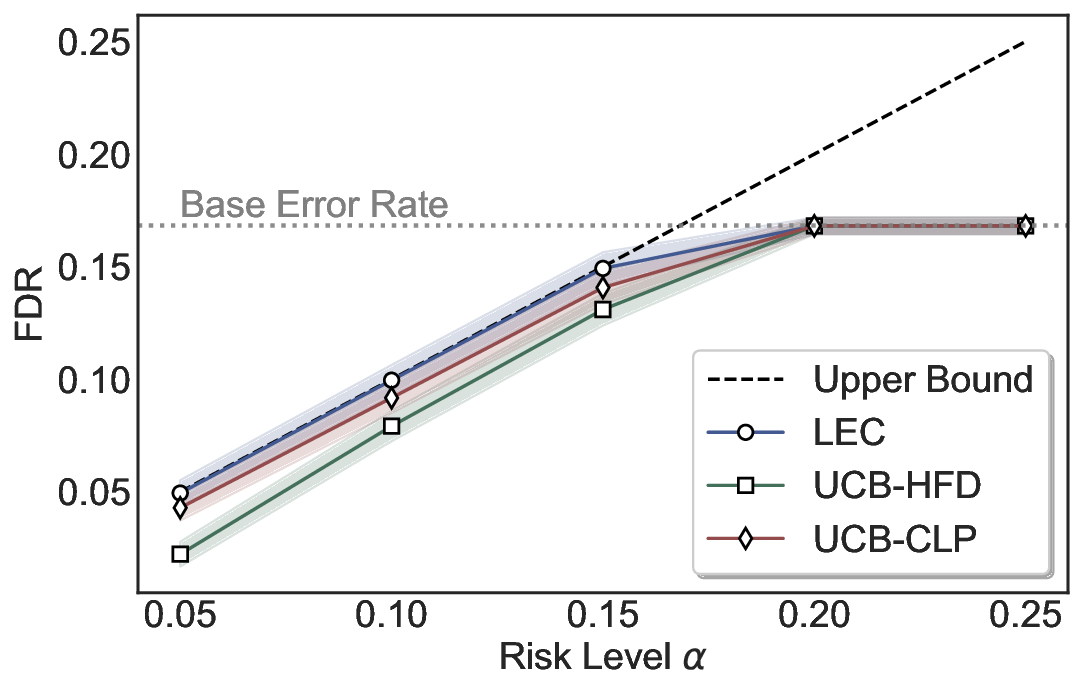

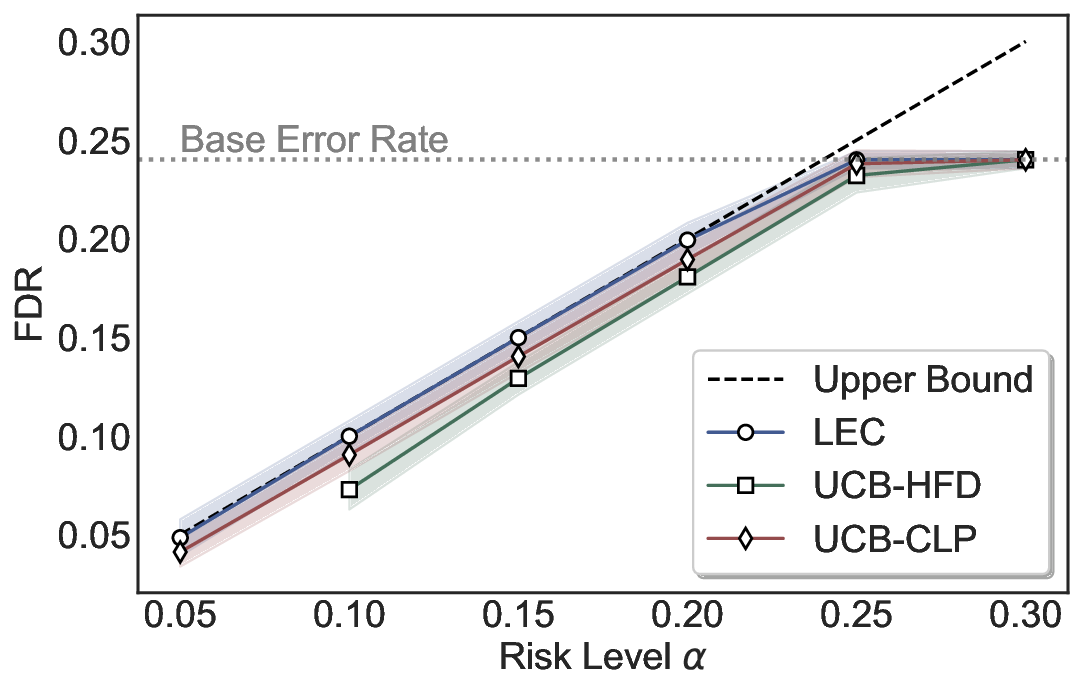

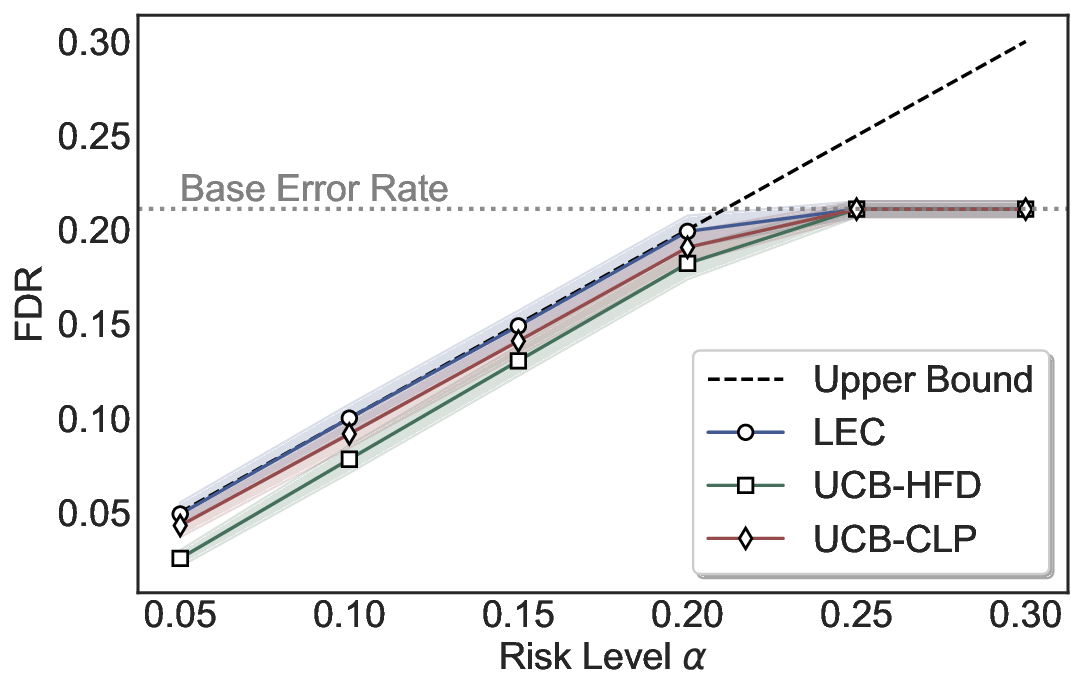

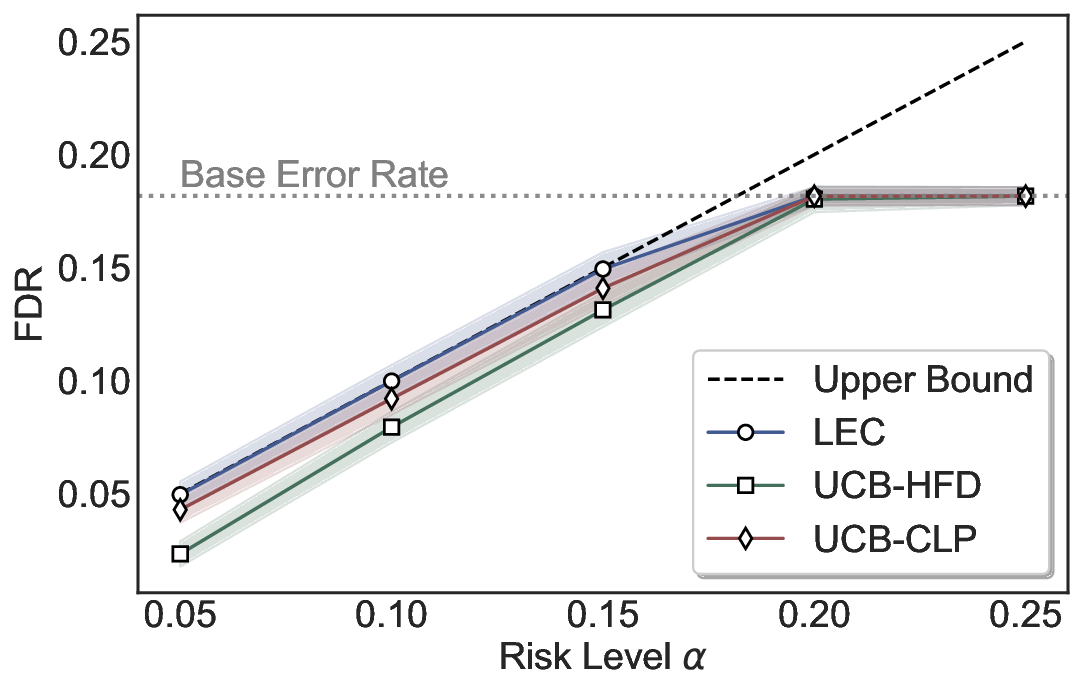

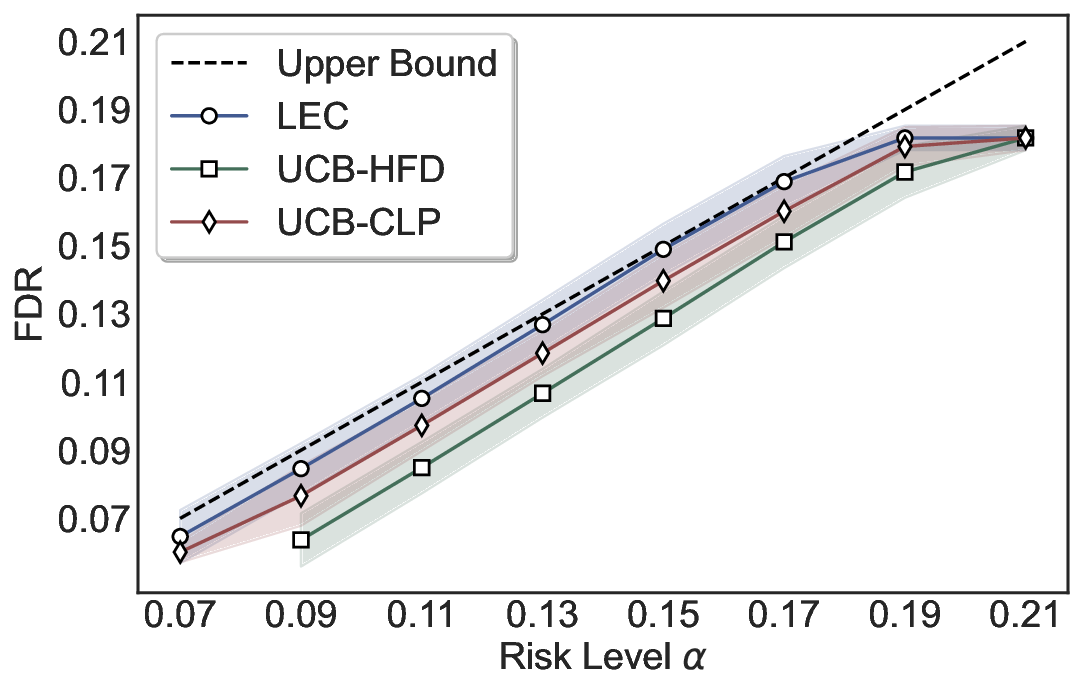

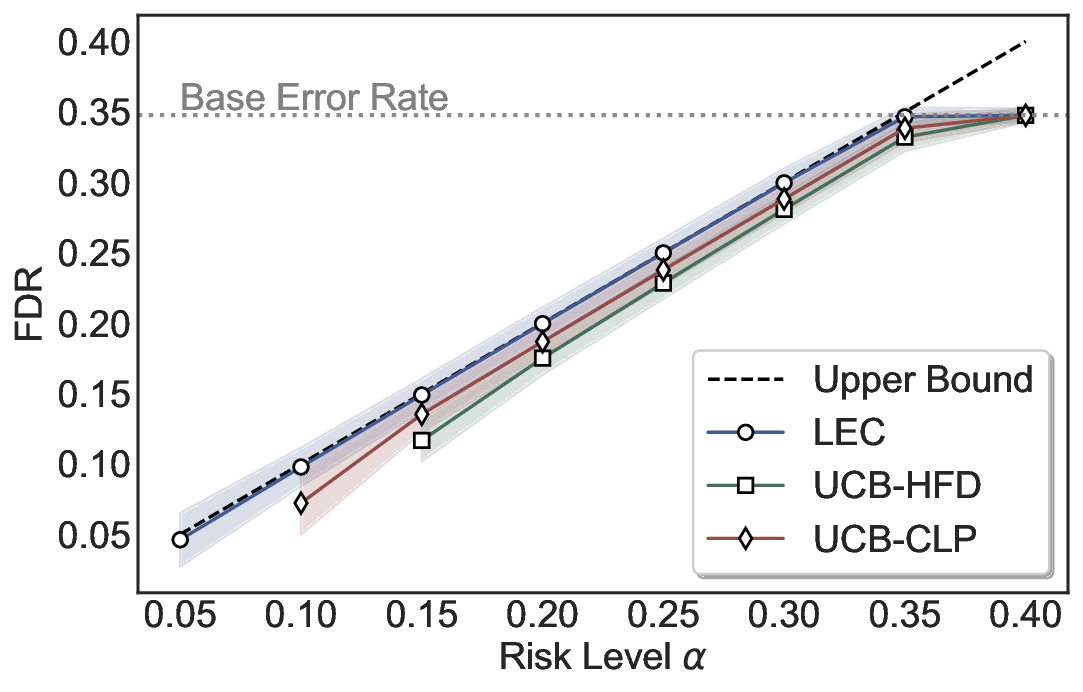

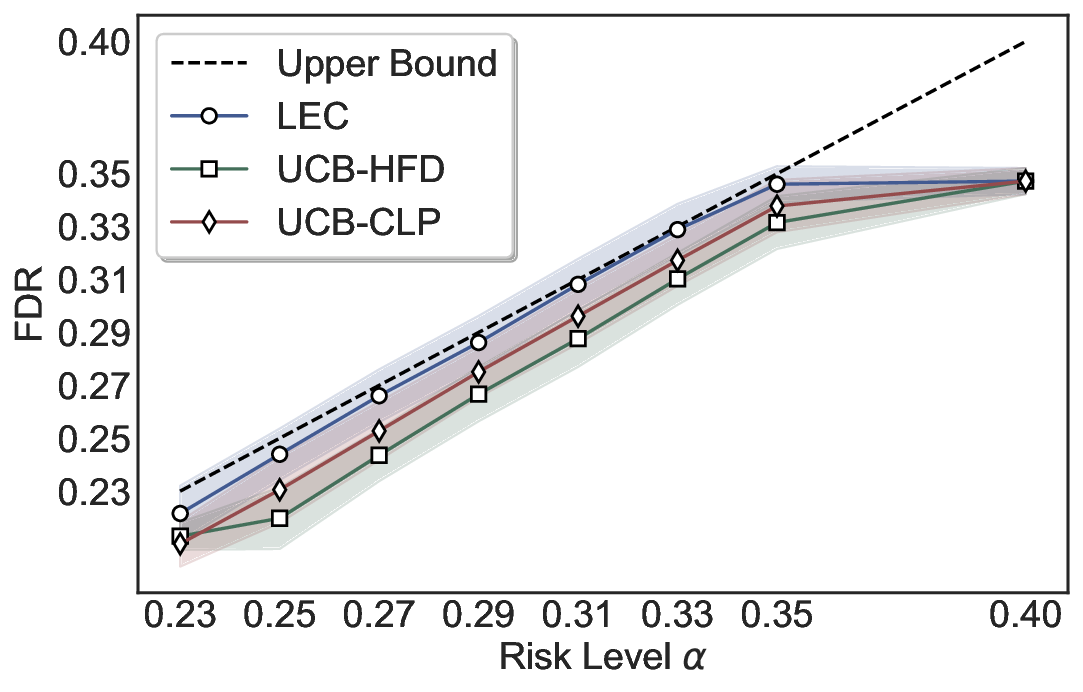

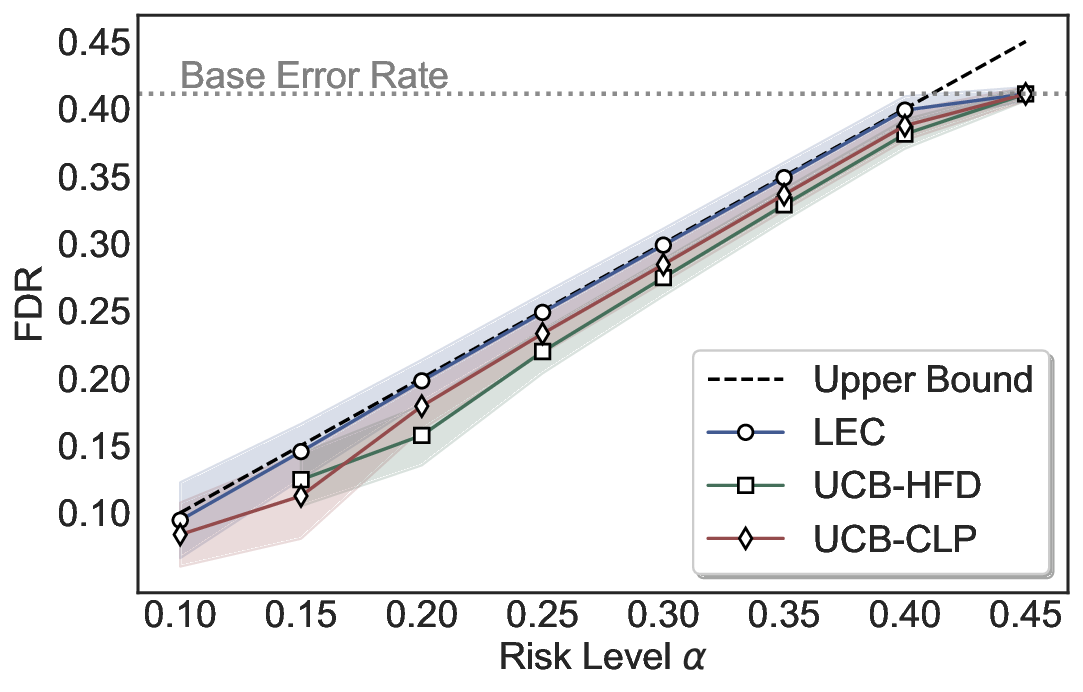

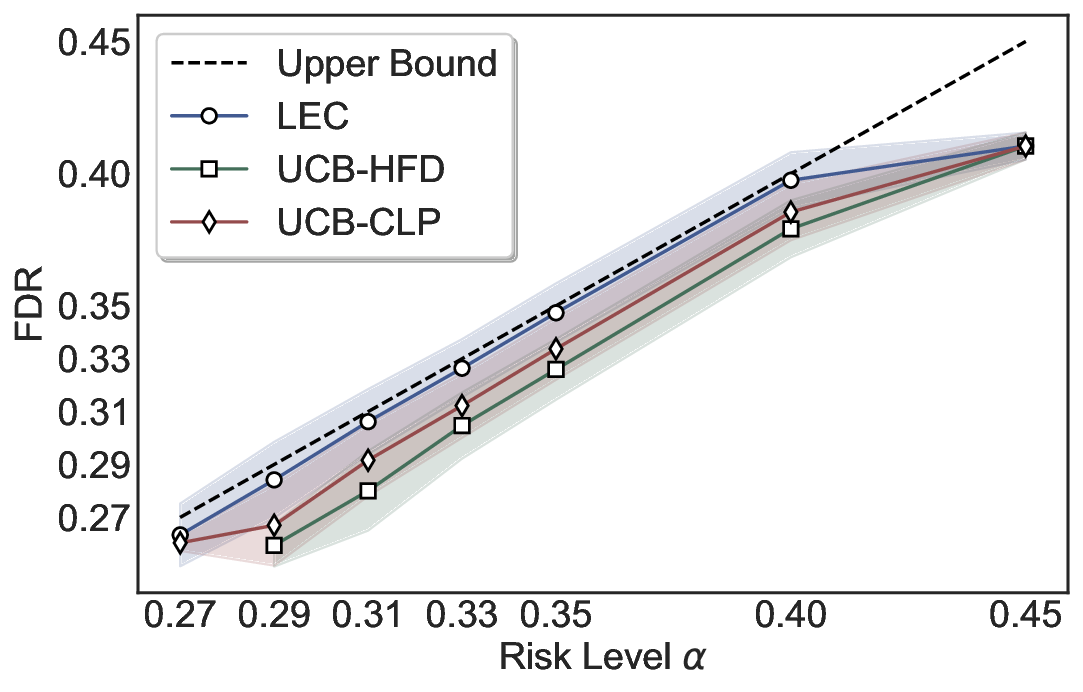

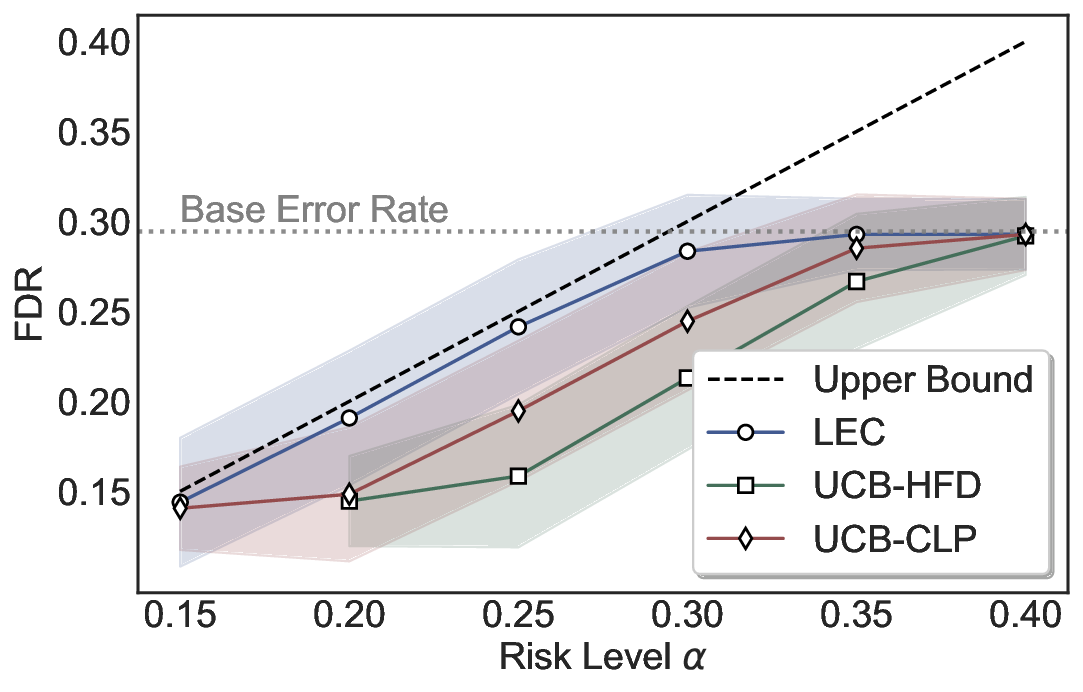

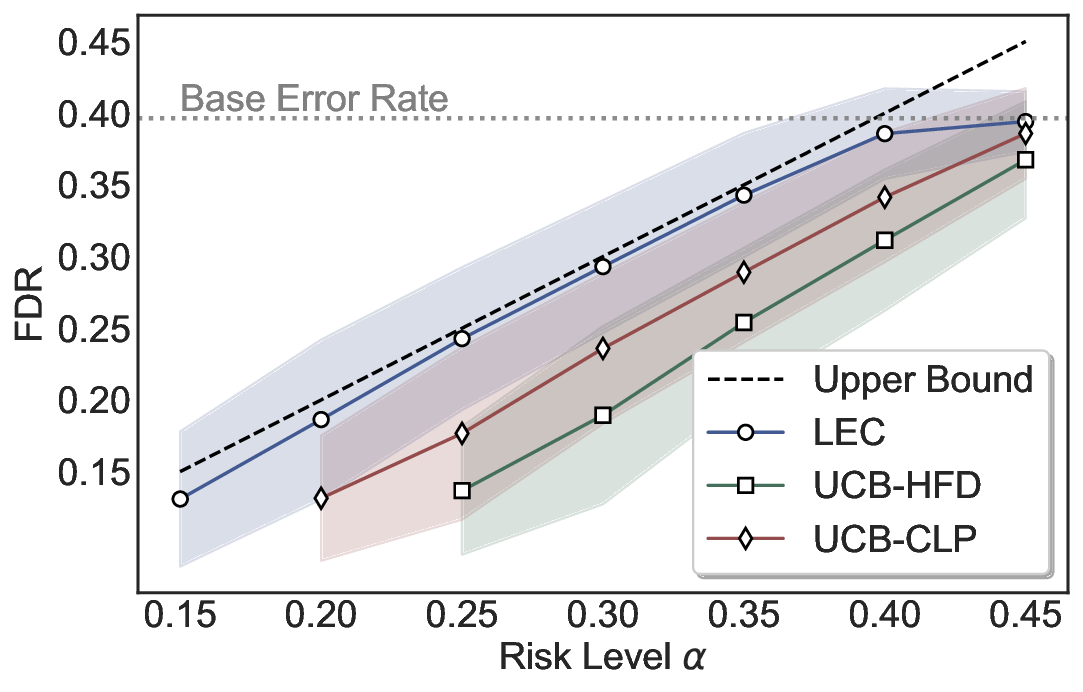

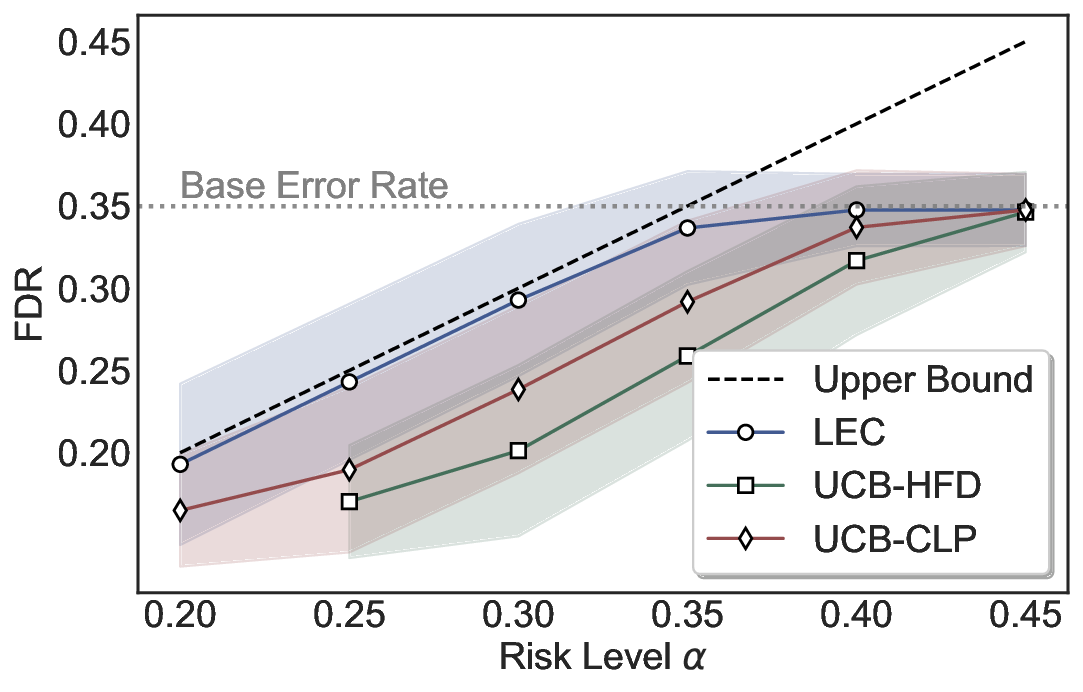

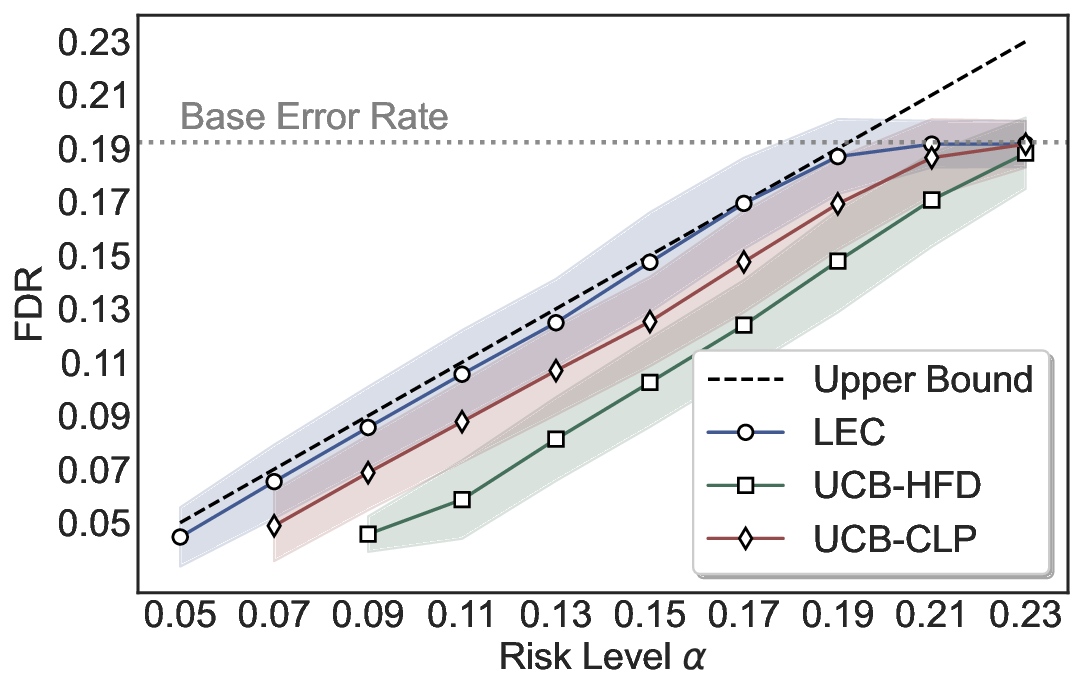

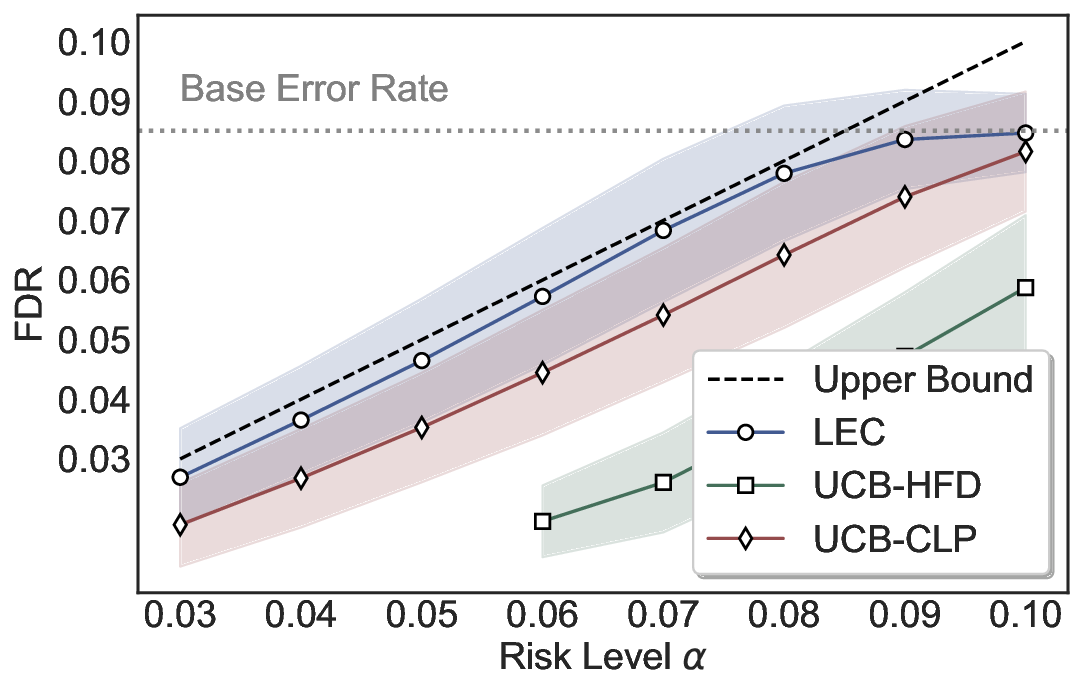

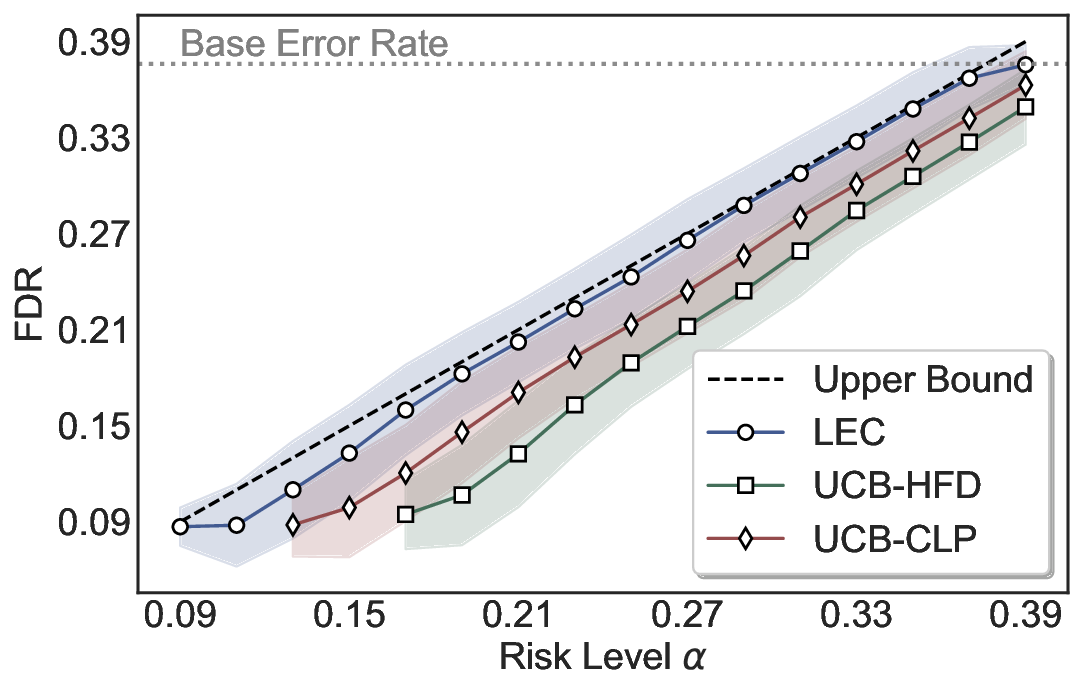

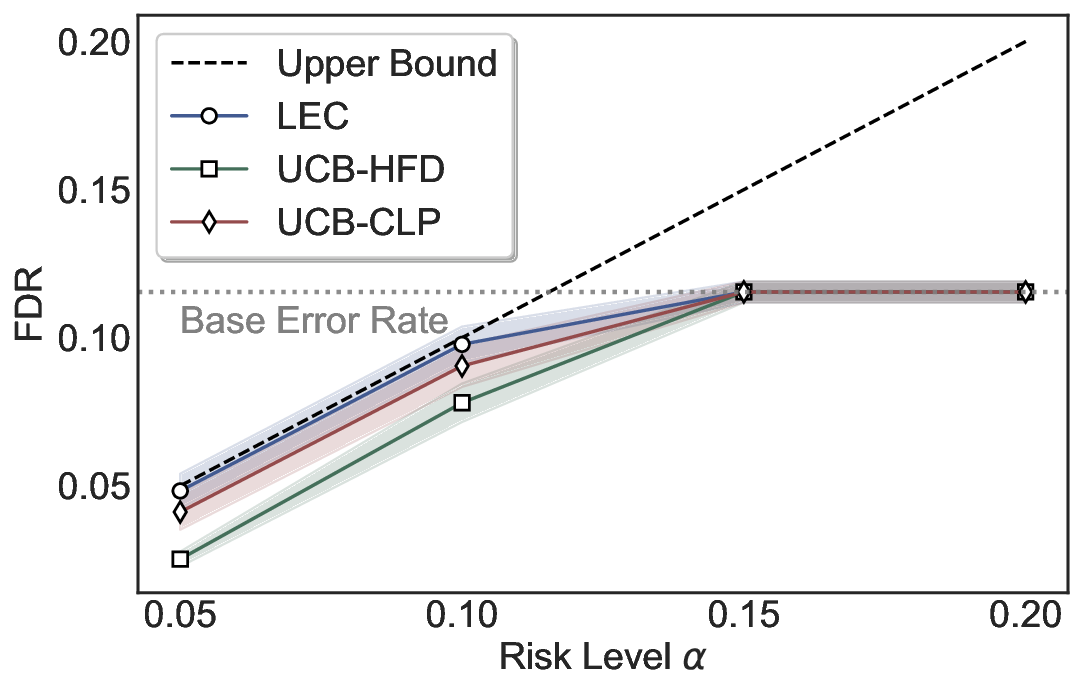

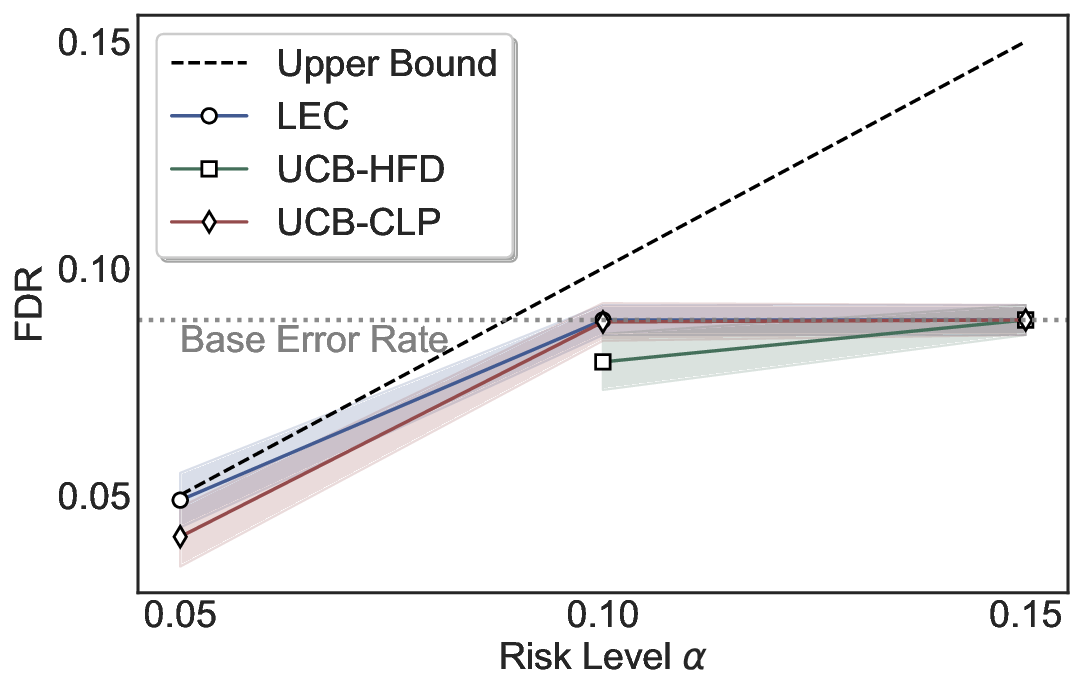

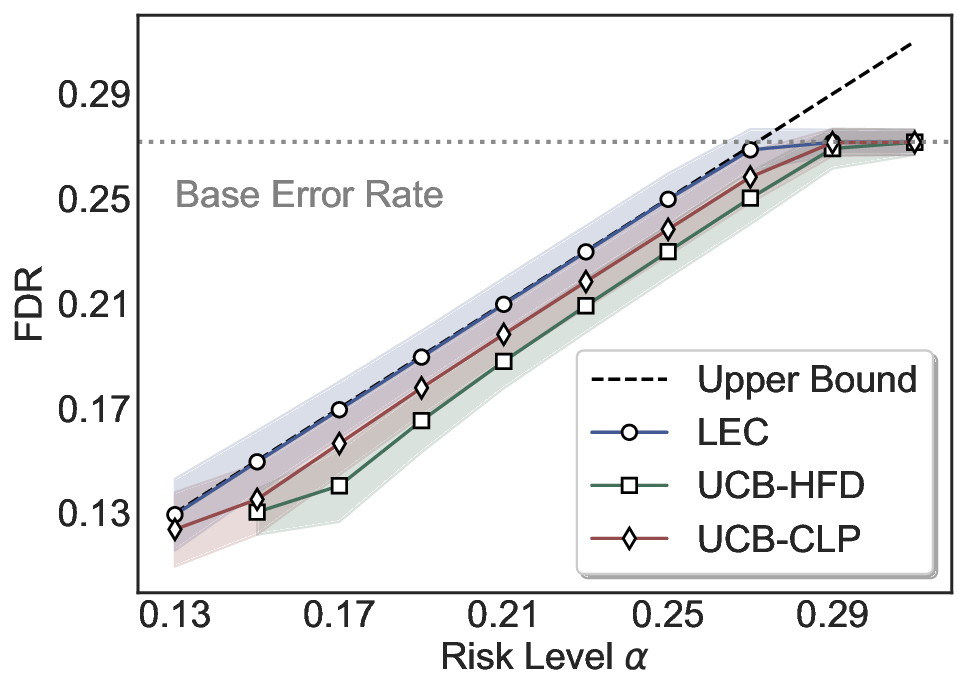

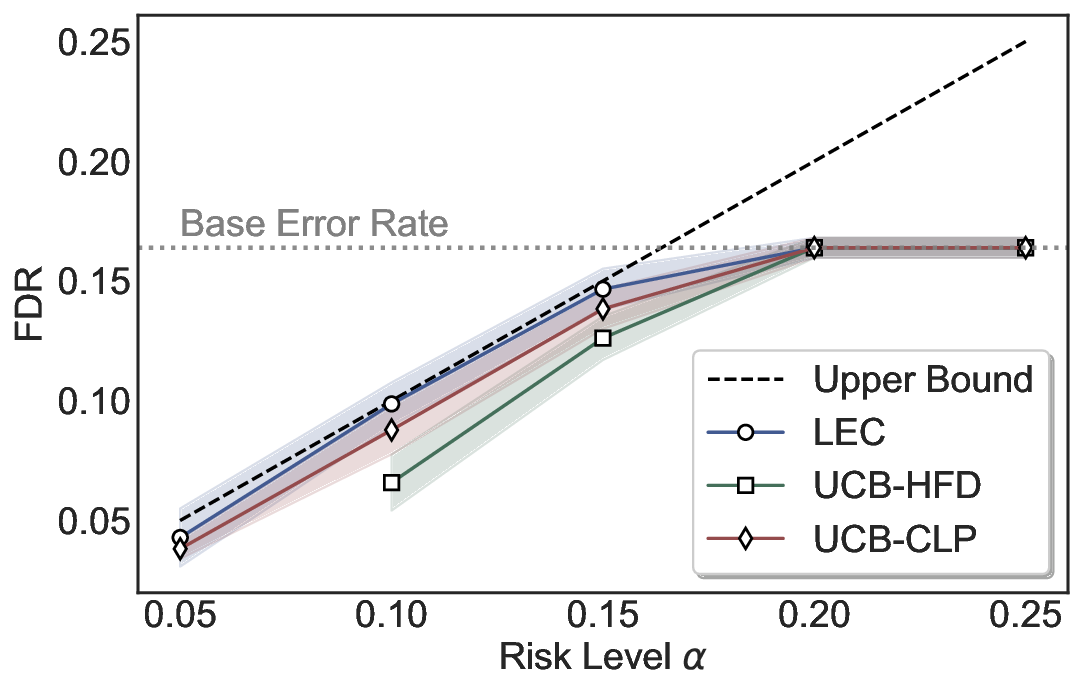

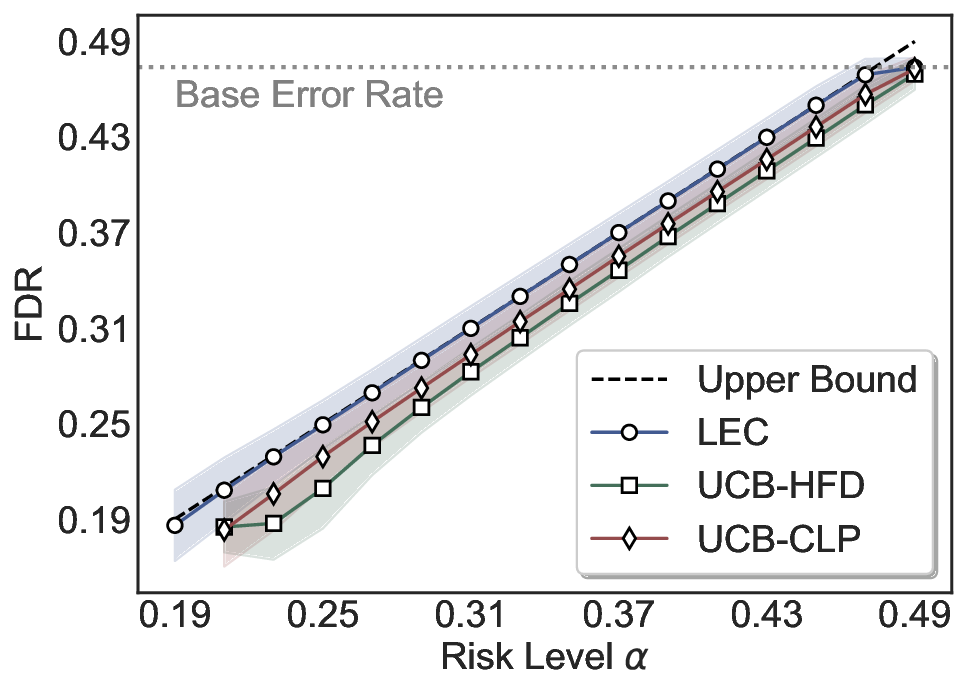

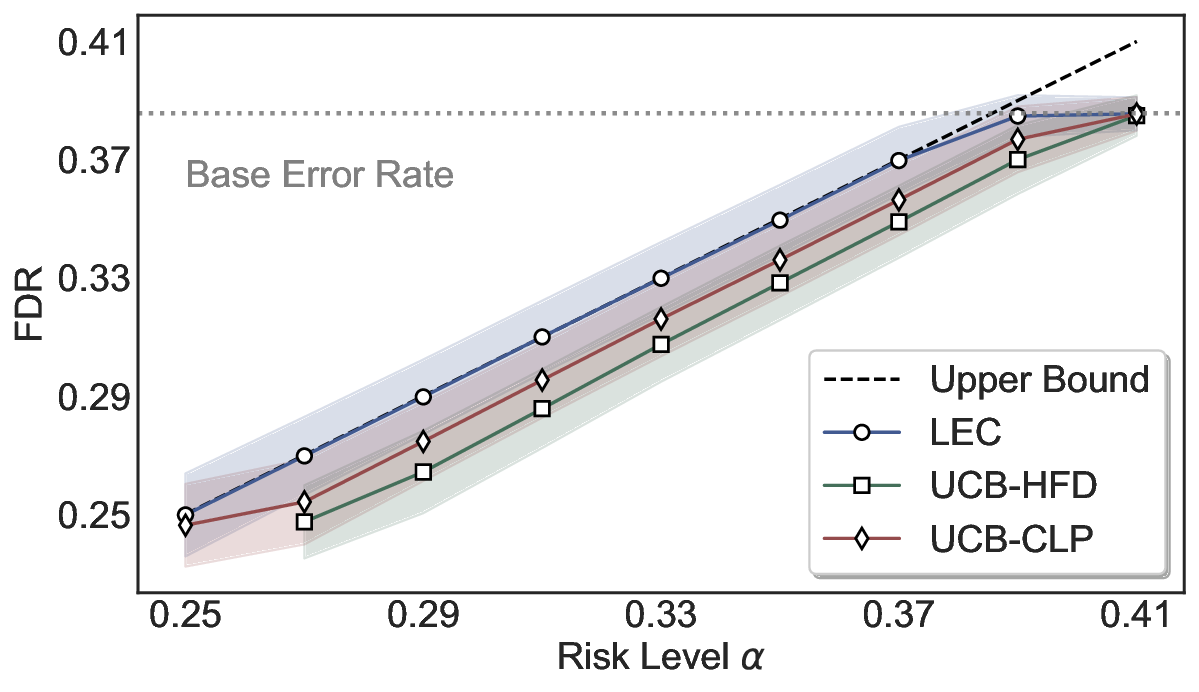

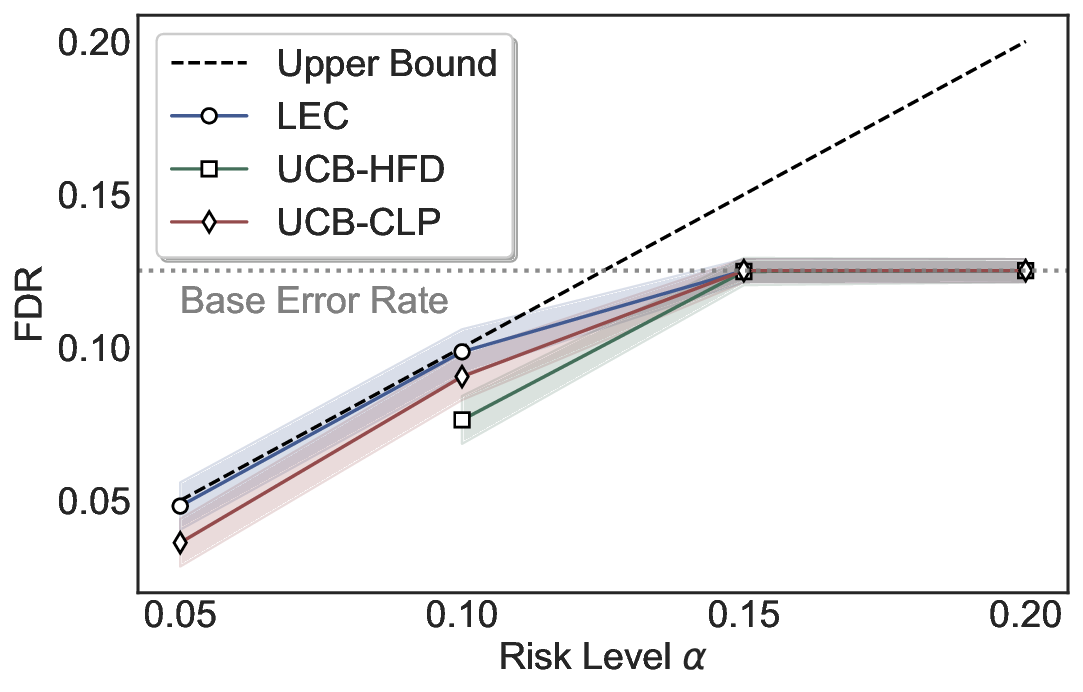

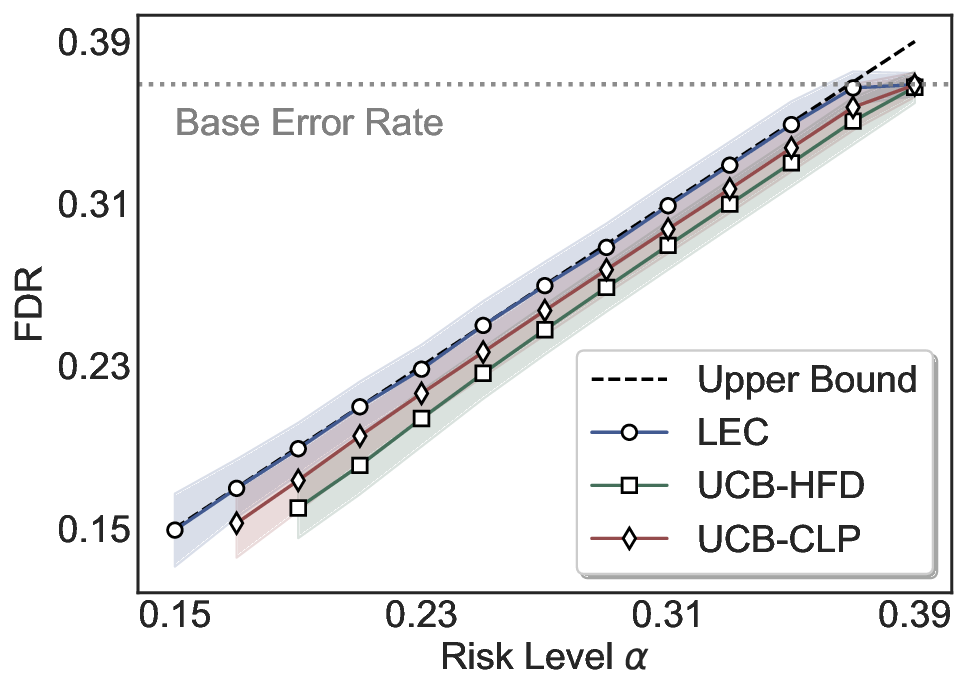

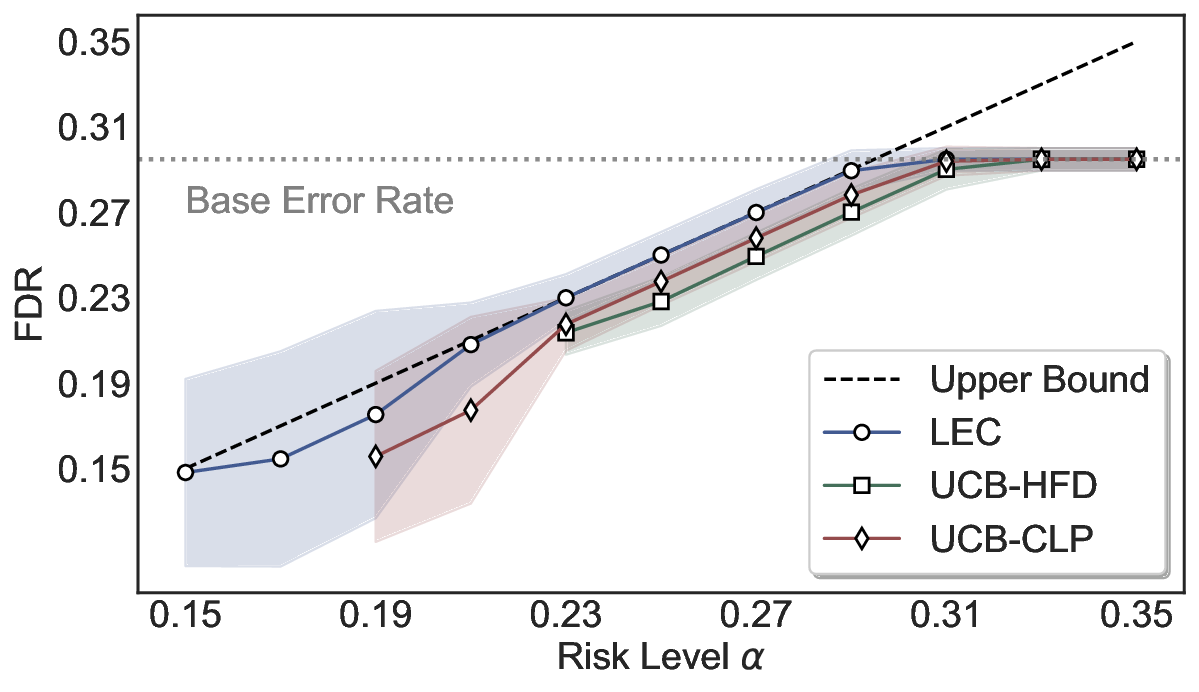

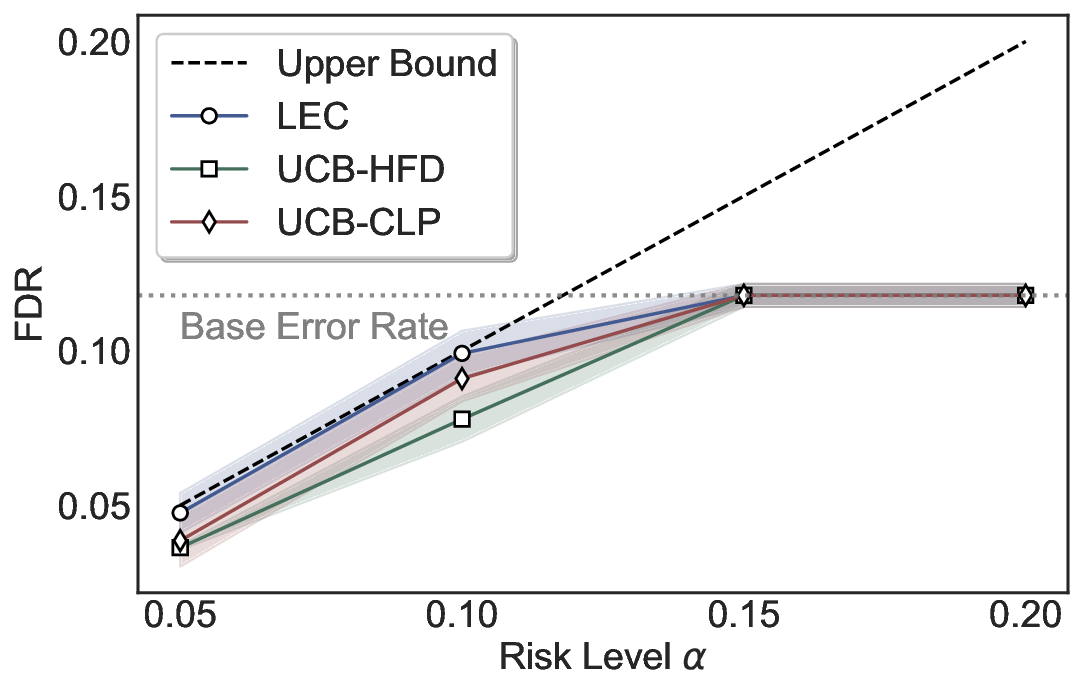

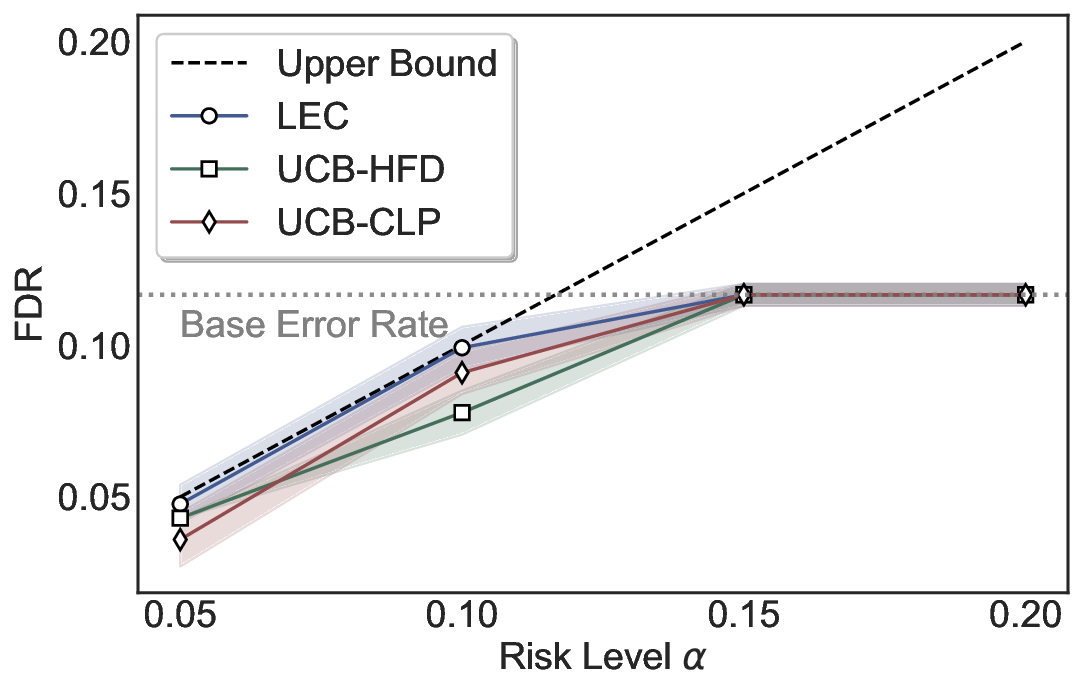

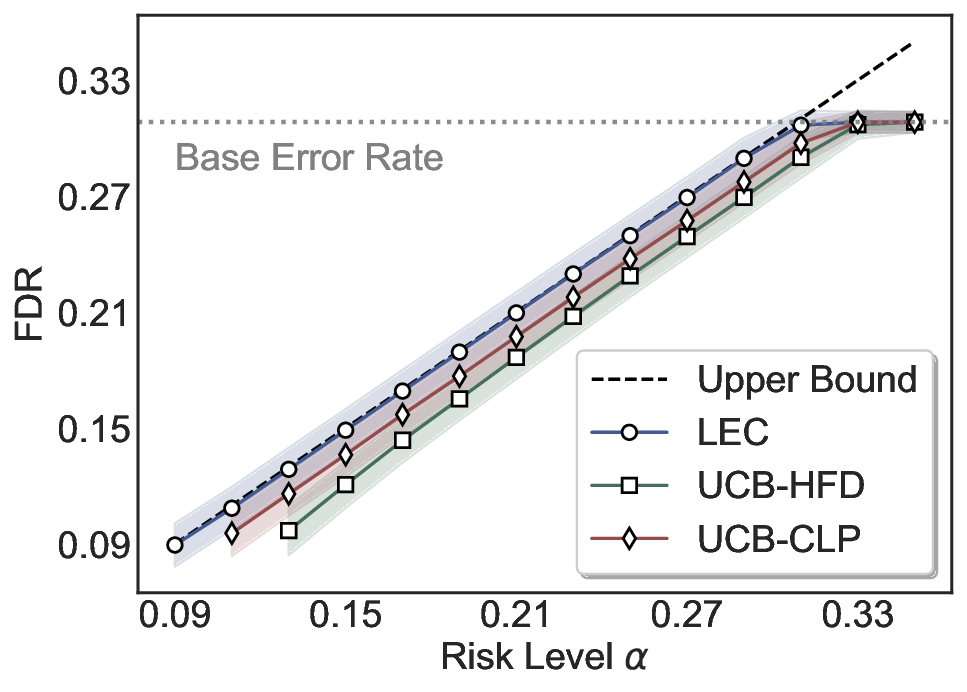

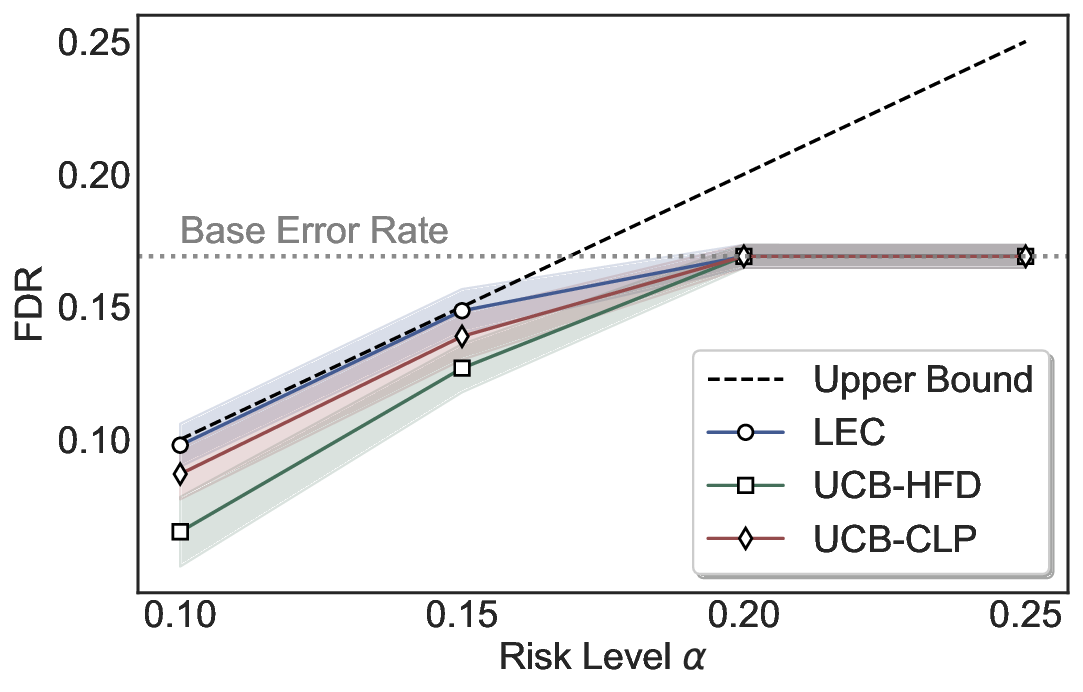

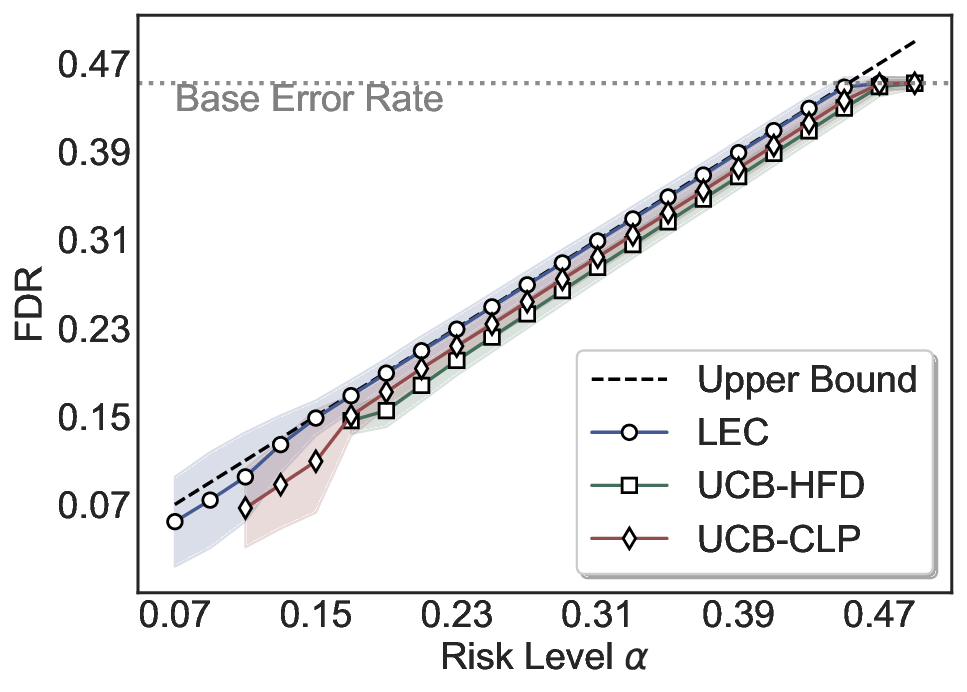

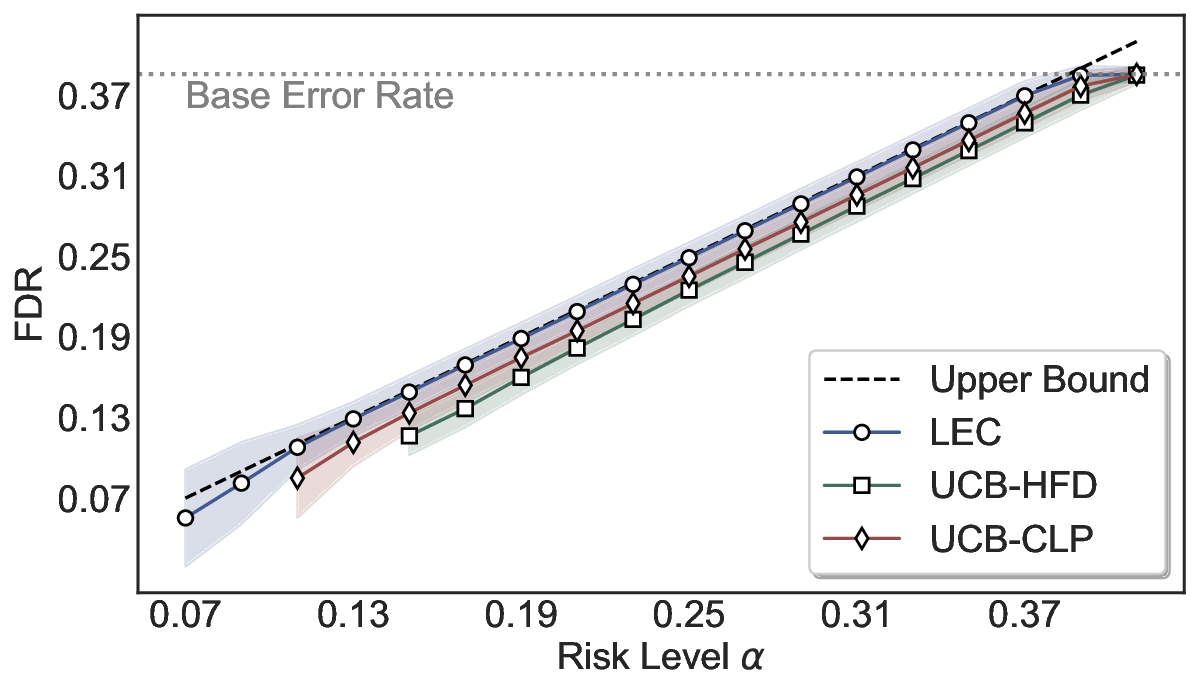

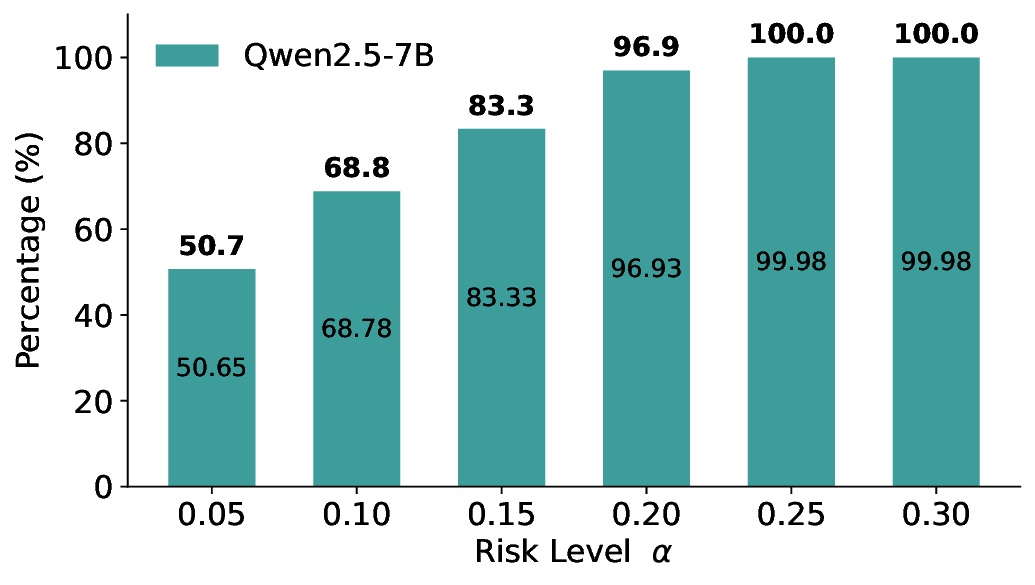

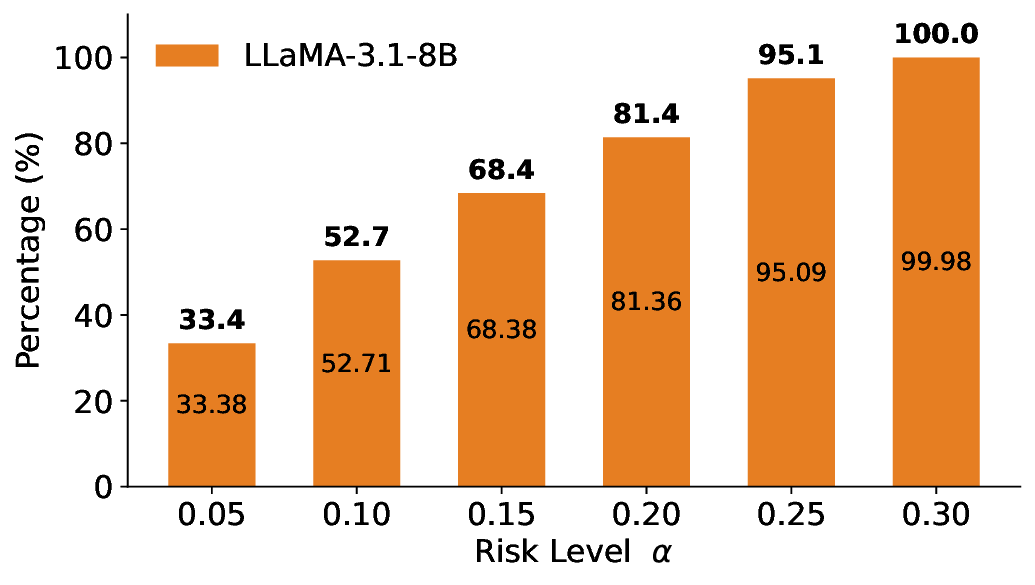

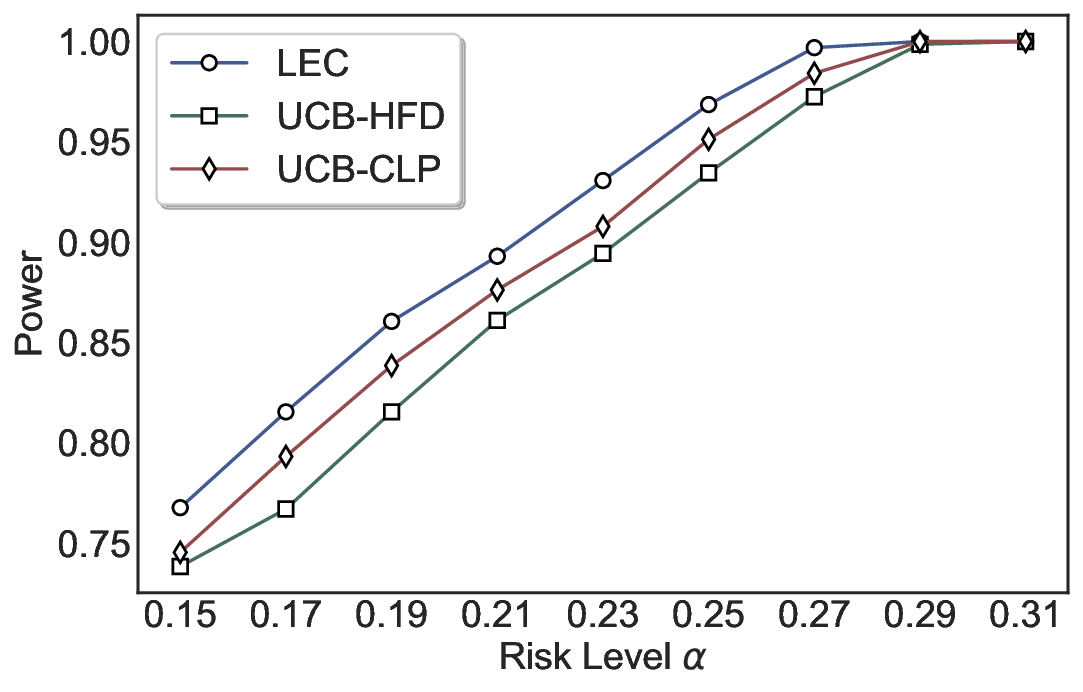

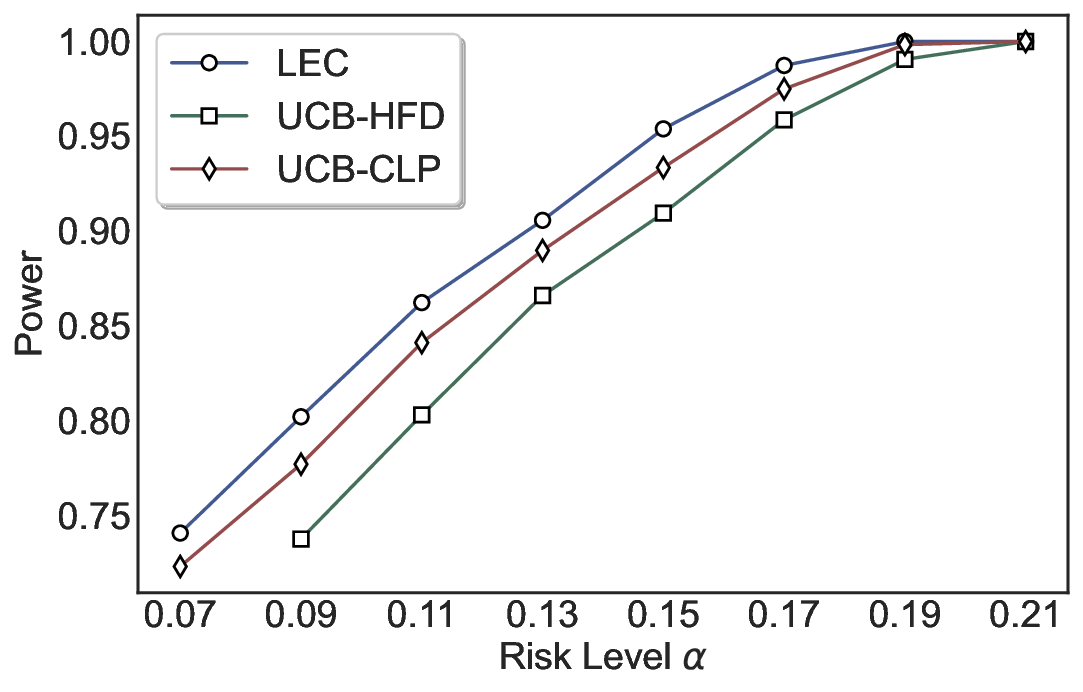

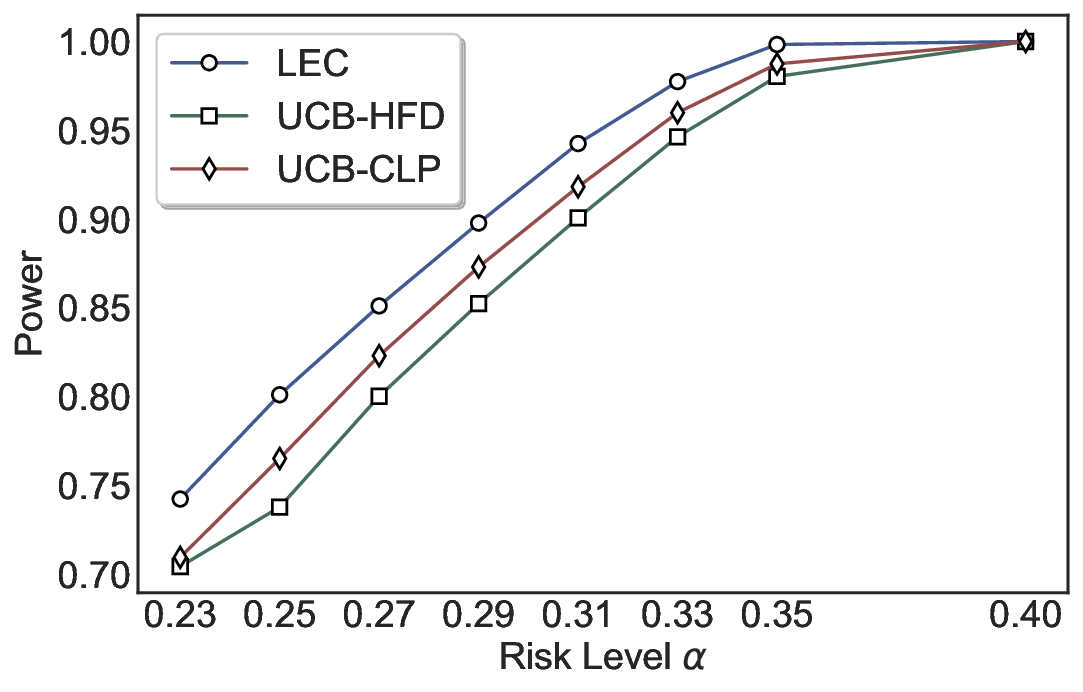

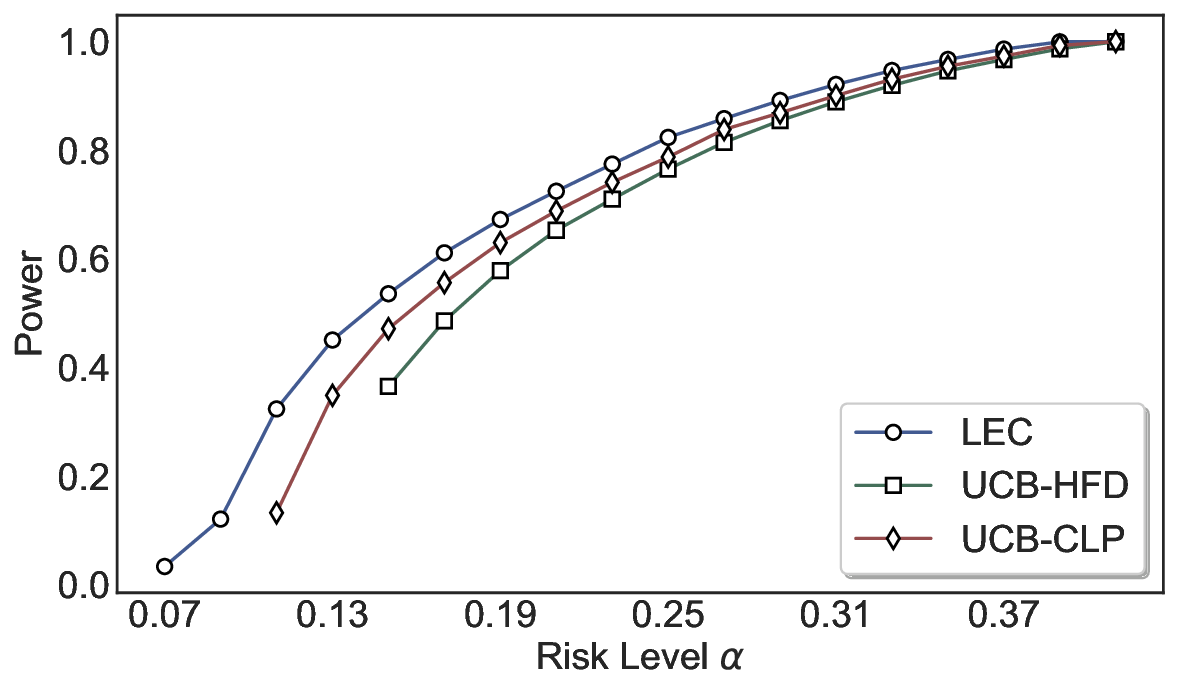

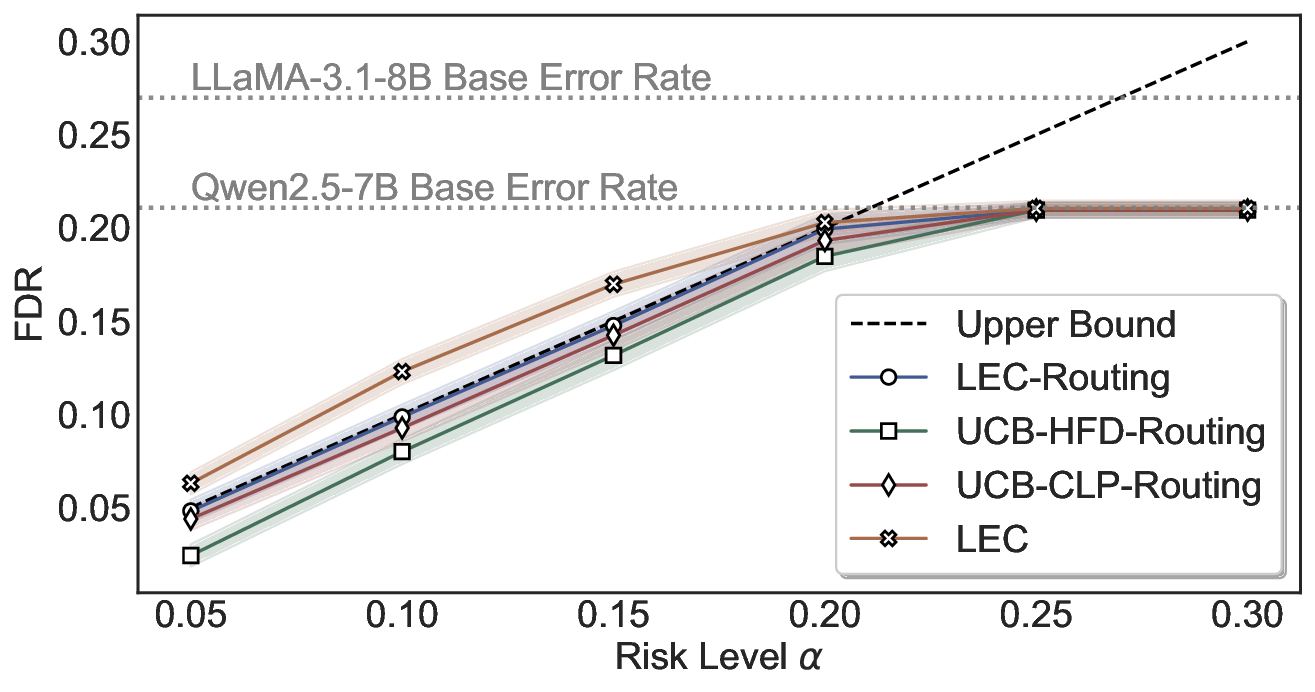

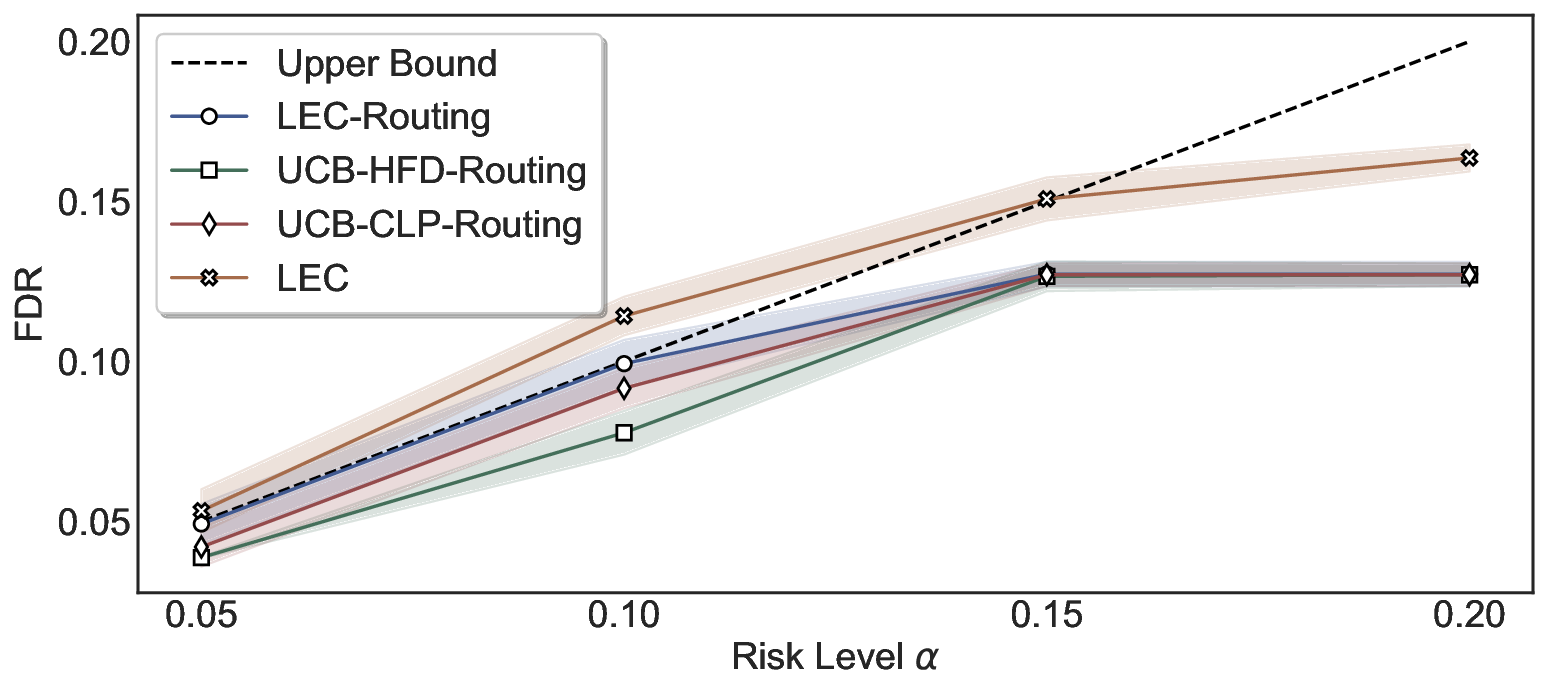

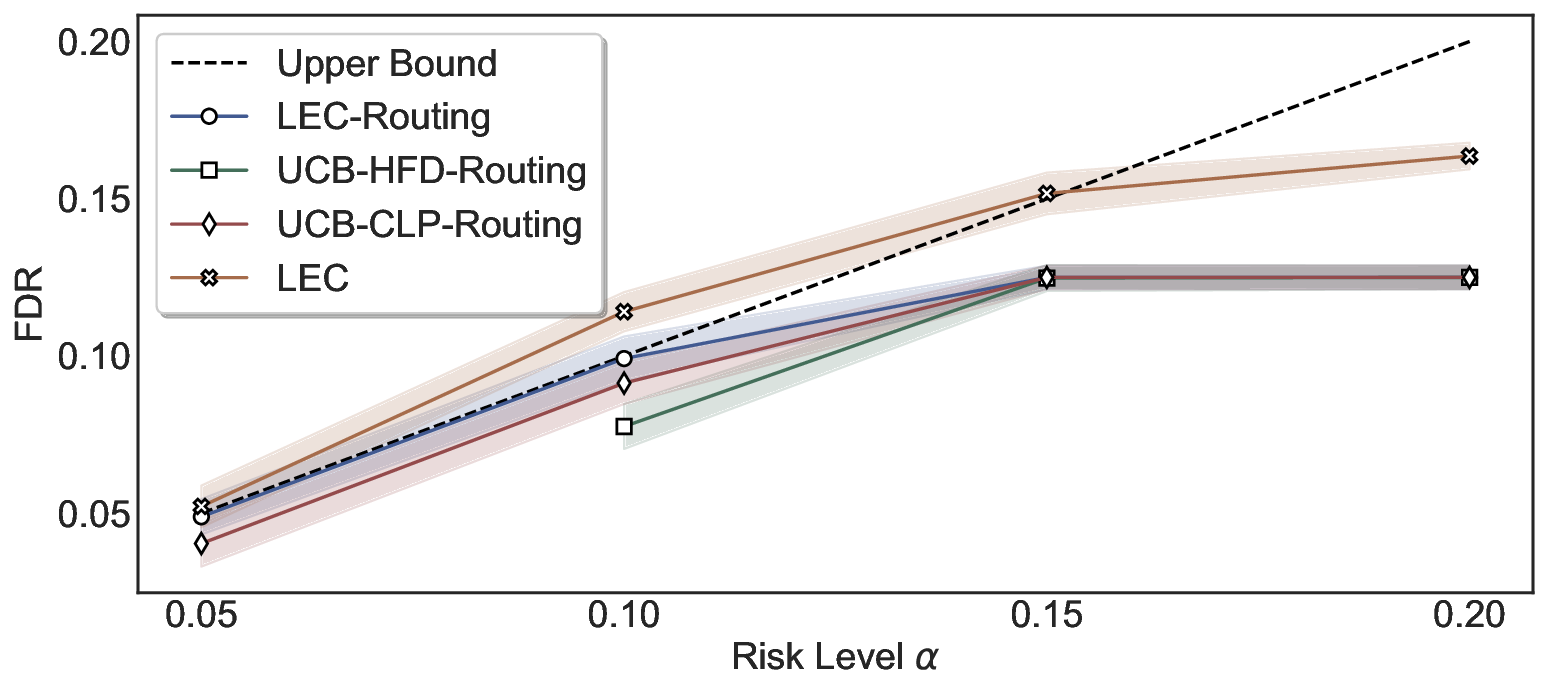

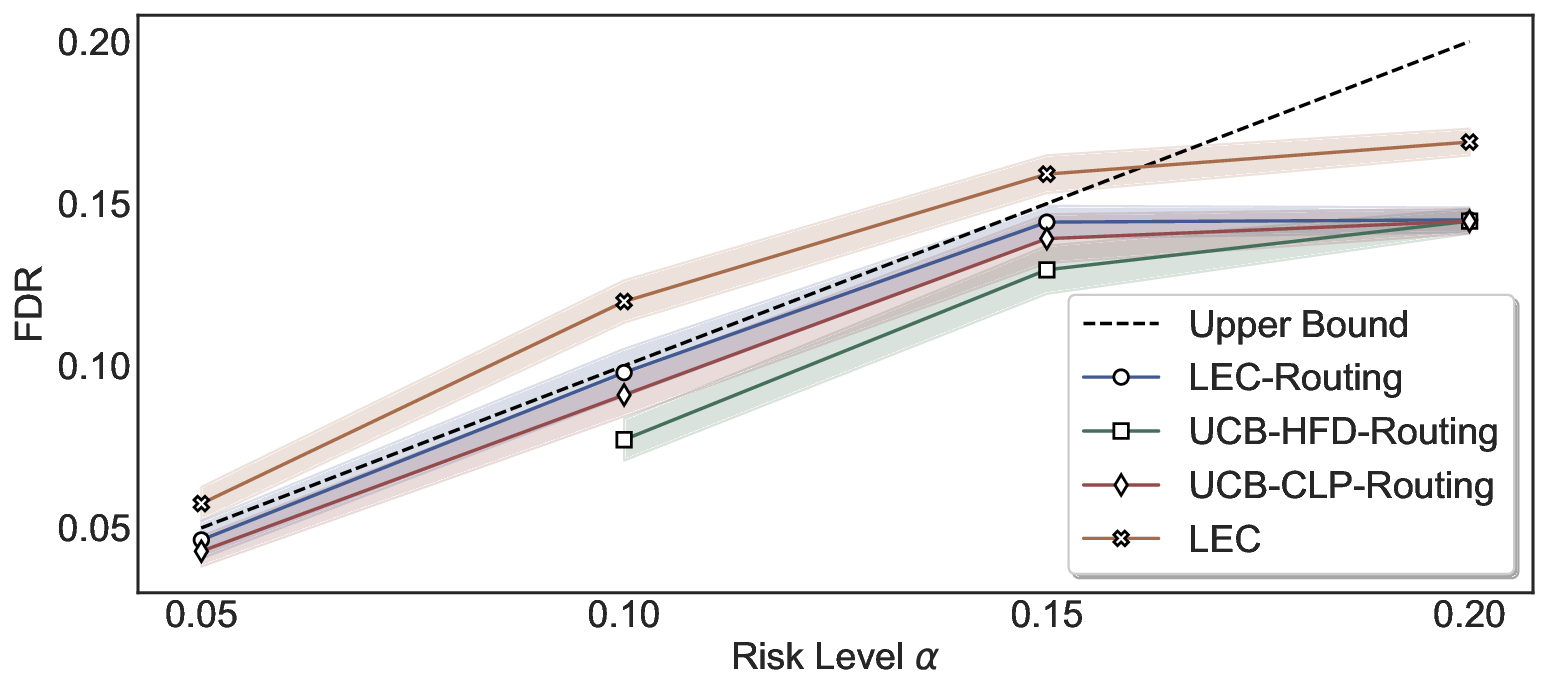

Statistical Validity. We first evaluate LEC in single-model selective prediction settings. As shown in Figures 2 and3, across both CommonsenseQA and TriviaQA datasets and eight LLMs, LEC consistently achieves valid FDR control: the test-time FDR, averaged over 500 random splits, does not exceed the target risk level. For example, on Common-senseQA with a risk level of 0.05, LEC achieves an average FDR of 0.0497 when applied to the OpenChat-3.5 model.

Beyond statistical validity, we examine how tightly different methods control the system-level risk under the same target FDR constraint. As presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3, across both datasets and all LLMs, LEC consistently operates near the target risk level, while UCB-based baselines, including those using exact Clopper-Pearson-style UCB, remain well below it, indicating more conservative behavior. For instance, on TriviaQA utilizing the Qwen2.5-3B model, LEC achieves an FDR of 0.0987, whereas UCB-CLP attains 0.0878, and UCB-HFD fails to identify feasible thresholds due to overly conservative UCB.

This tighter control allows LEC to retain substantially more samples without compromising the user-specified FDR con- straint. As illustrated in Table 1, this difference in tightness is further reflected in the power of each method. Across all evaluated LLMs and risk levels, LEC consistently achieves higher power than UCB-based baselines, indicating that it admits more valid predictions under the same statistical constraint. In contrast, the conservative nature of UCB-based methods, particularly those based on Hoeffding’s inequality, often leads to substantially reduced power, or even the absence of feasible thresholds at low risk levels. For example, at a risk level of 0.05 on TriviaQA with the Qwen2.5-14B model, LEC achieves a power of 0.7193, retaining 9.5% more admissible samples than UCB-CLP, while UCB-HFD fails to yield any feasible threshold at this level.

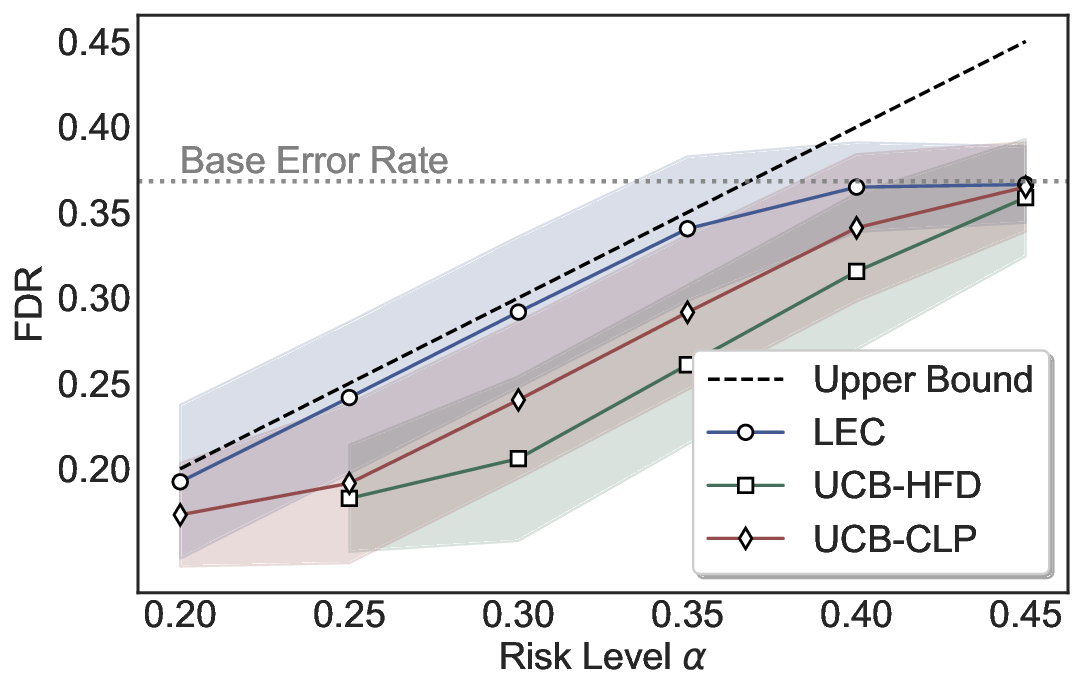

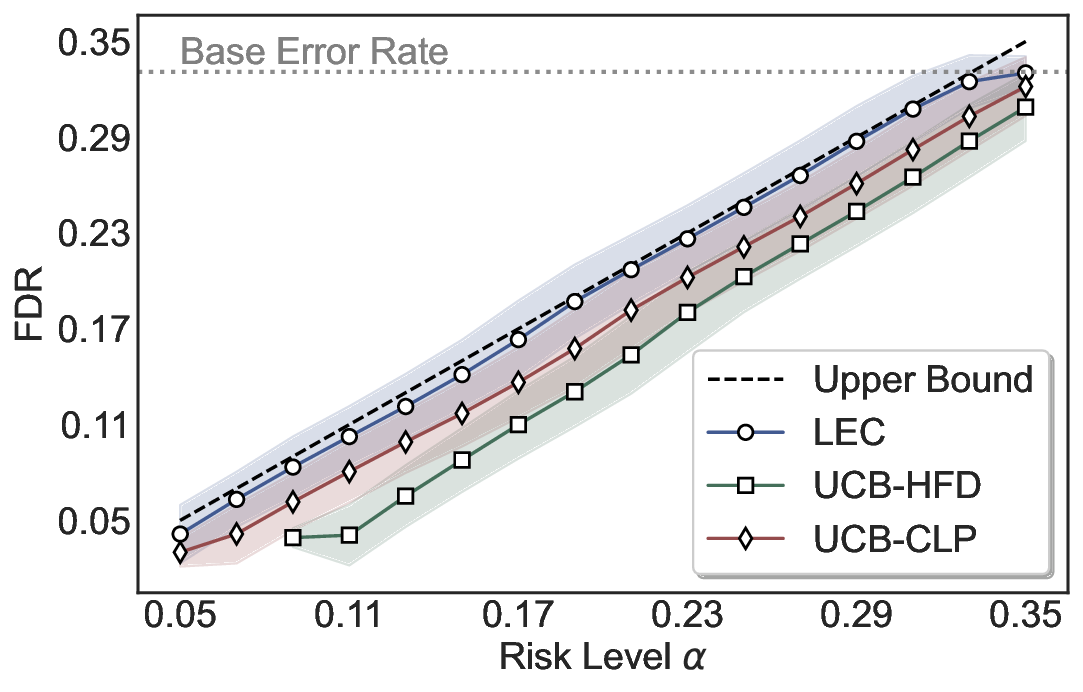

Robustness Across Evaluation Settings. We further examine whether the observed advantages of LEC are sensitive to specific evaluation settings. As shown in Figures 4 and5, across five LLMs and all tested risk levels, LEC consistently maintains tight FDR control and achieves higher power than UCB-based baselines under the same statistical constraints, with bi-entailment as the alignment criterion in function A.

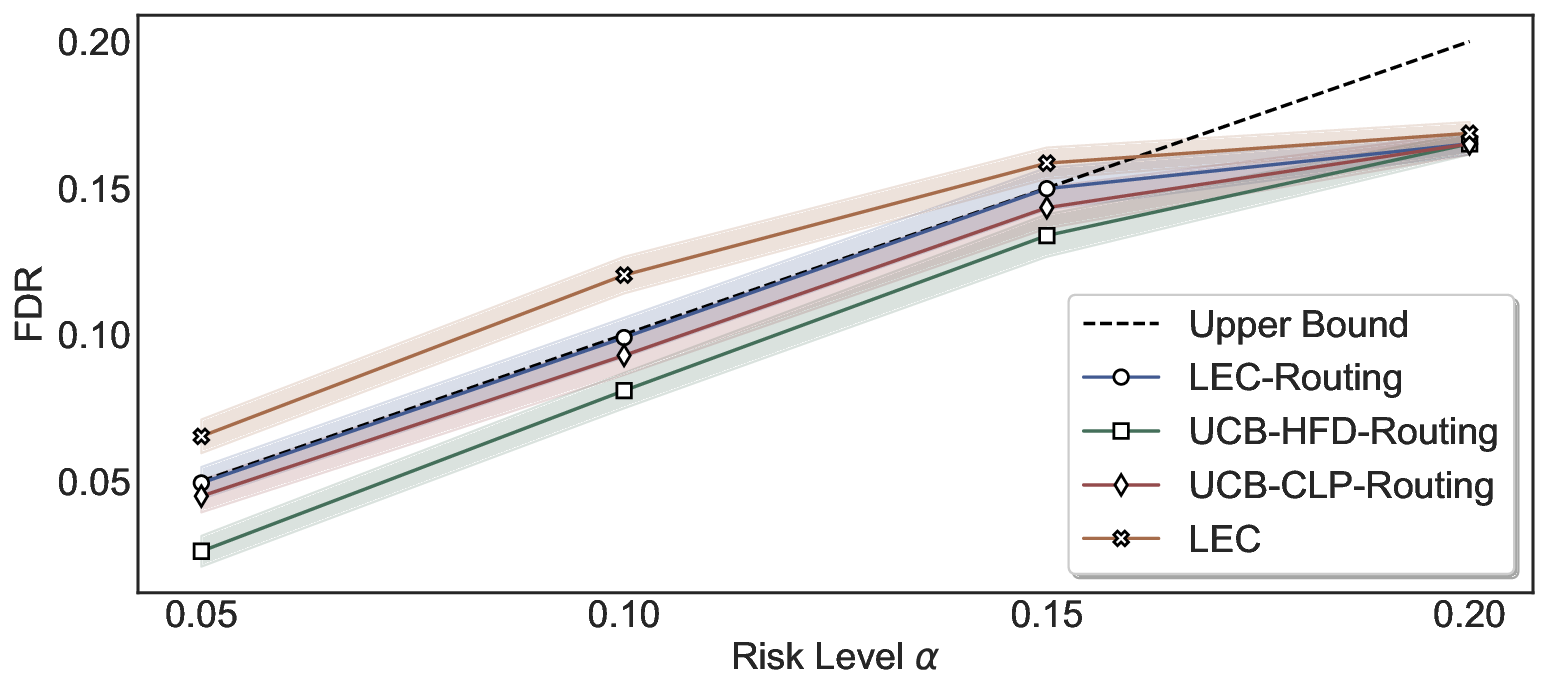

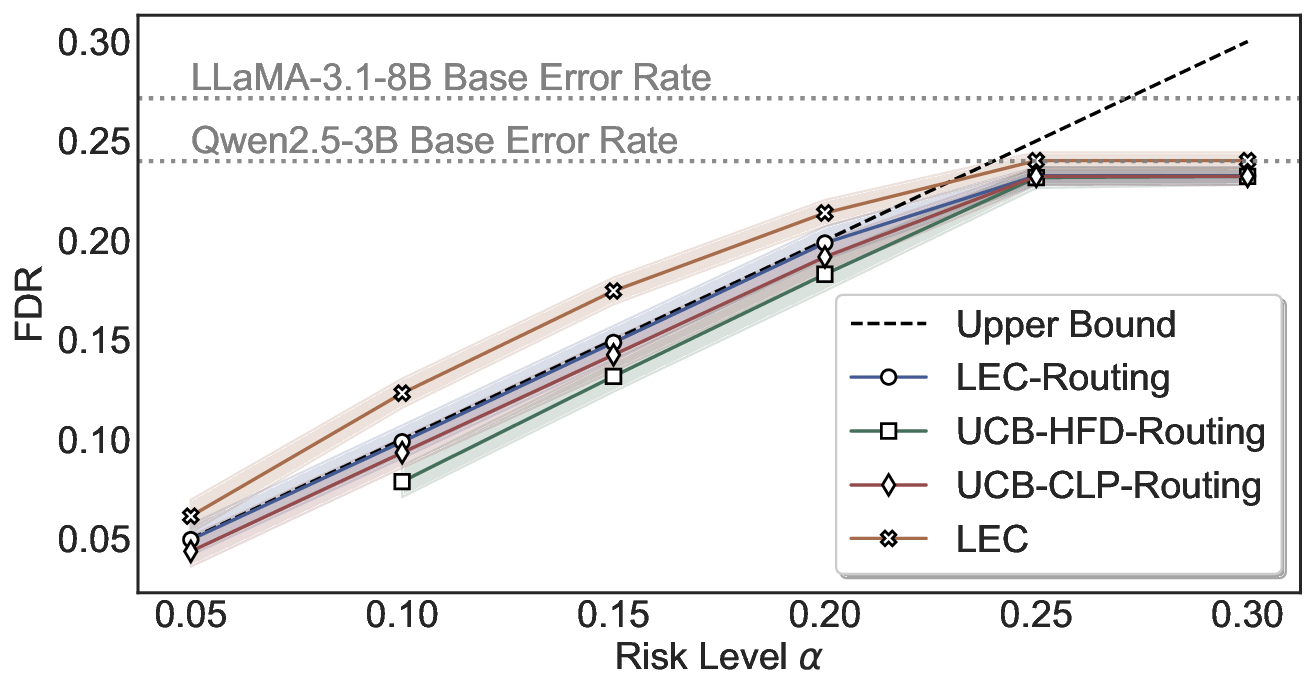

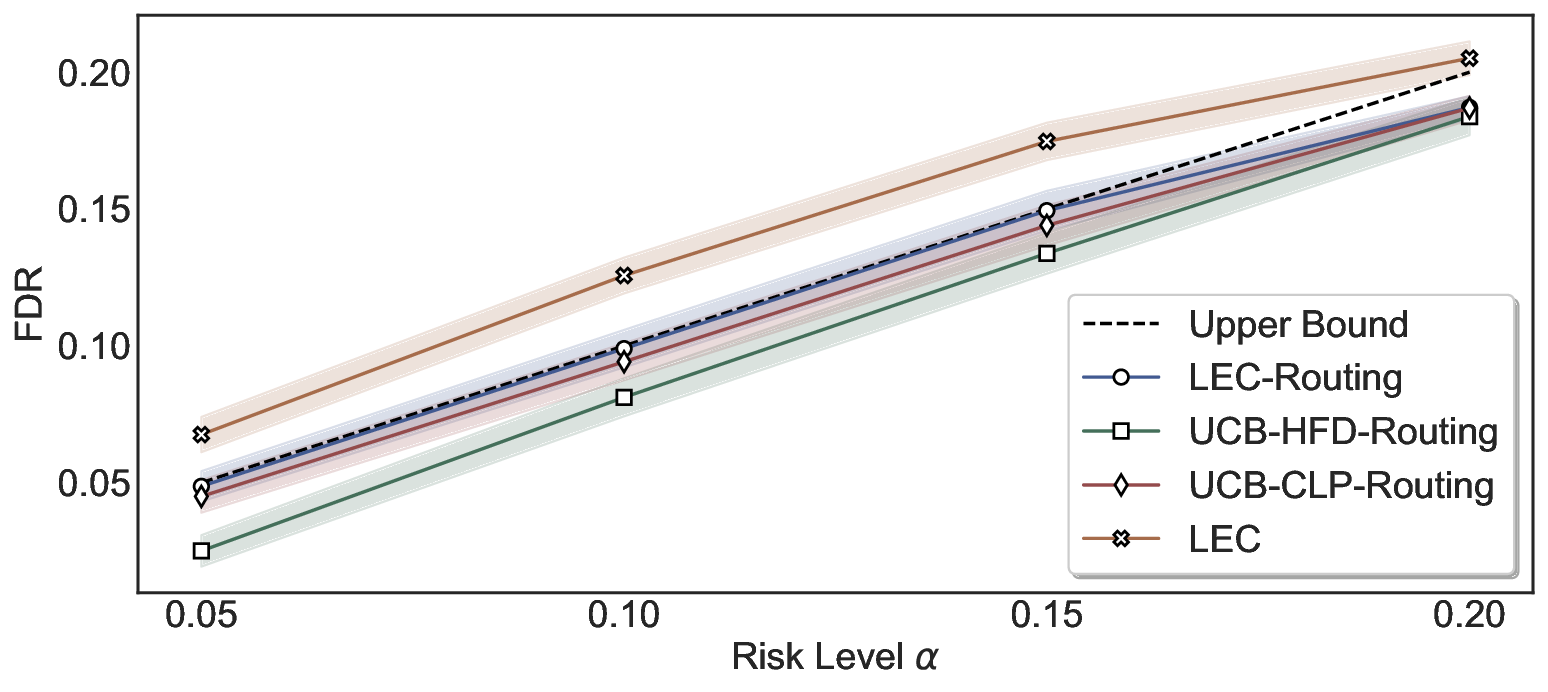

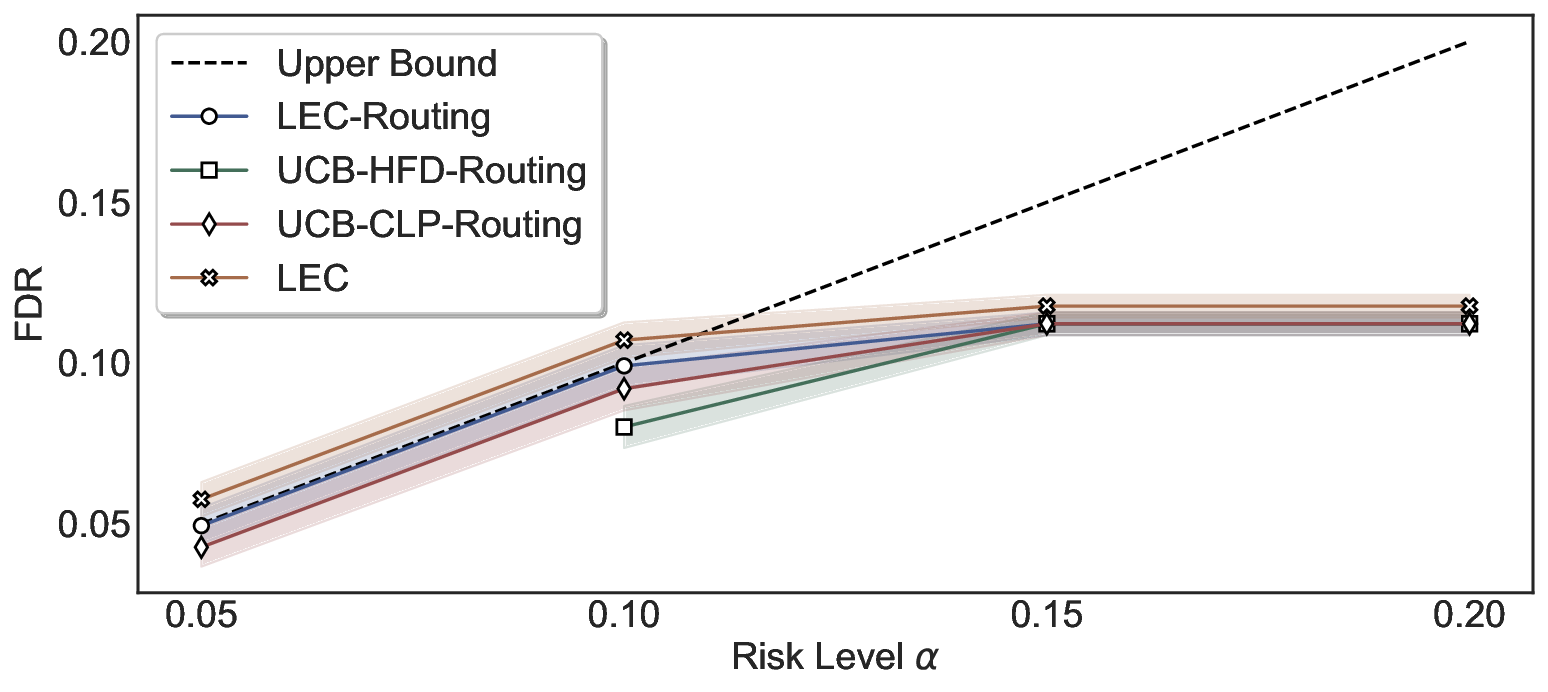

We denote by LEC-Routing the routing strategy obtained by applying the proposed linear expectation constraint to the two-model routing setting, where joint thresholds are calibrated over the system-level selection and error indicators to ensure FDR control across the entire routing pipeline.

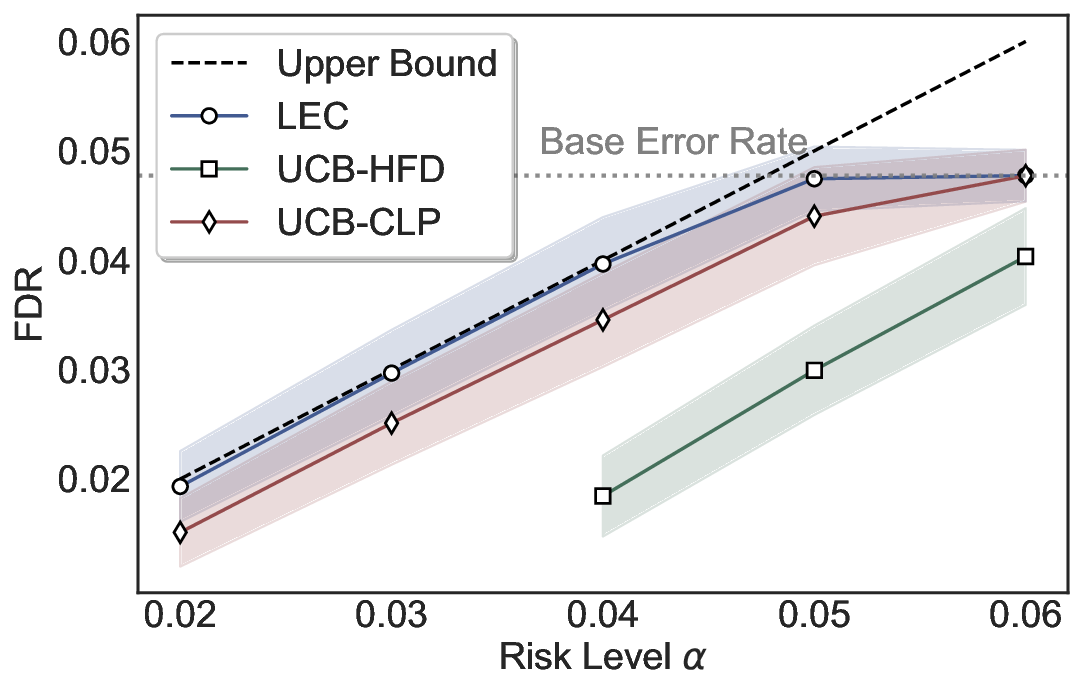

System-Level FDR Control. We compare LEC-Routing with UCB-based routing baselines (Jung et al., 2025), which extend confidence-bound risk control to the routing setting. Additionally, we consider a naive routing variant that calibrates thresholds for each model independently using LEC at the same target risk level, without joint threshold calibration. As shown in Figure 6, LEC-Routing consistently maintains valid and tight system-level FDR control on Common-senseQA by employing both Qwen2.5-3B and Qwen2.5-7B as primary models and selectively delegating inputs to the LLaMA-3.1-8B model, while UCB-HFD-Routing and UCB-CLP-Routing exhibit more conservative behavior. Notably, applying LEC without joint threshold calibration does not achieve valid system-level guarantees, which high- lights the necessity of joint threshold calibration for achieving reliable system-level FDR control in routing systems.

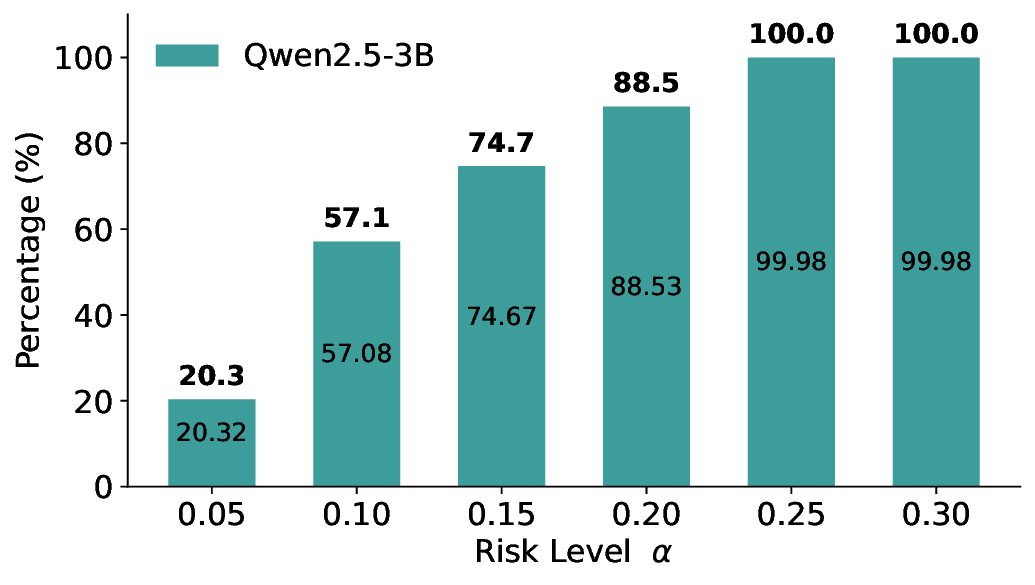

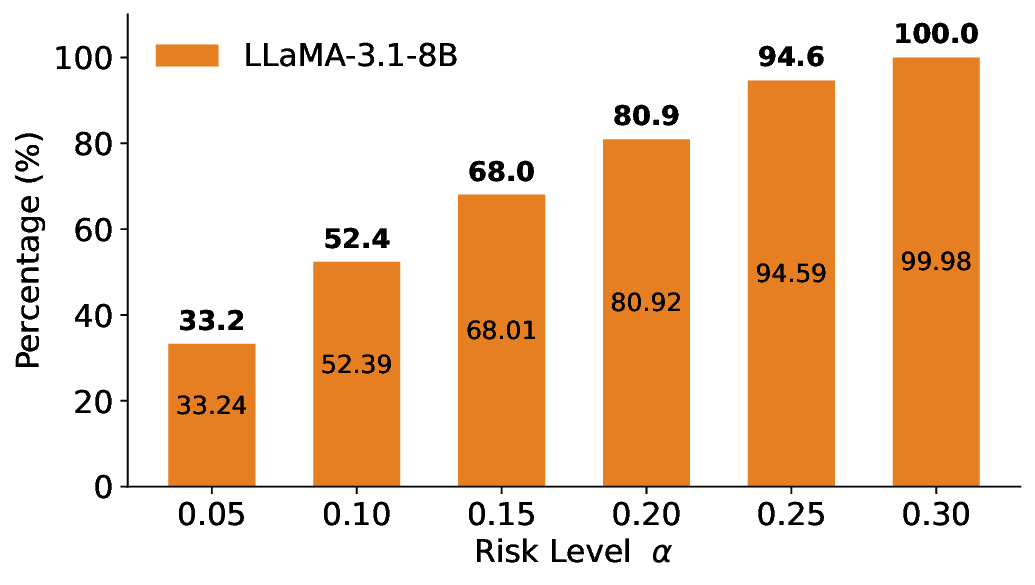

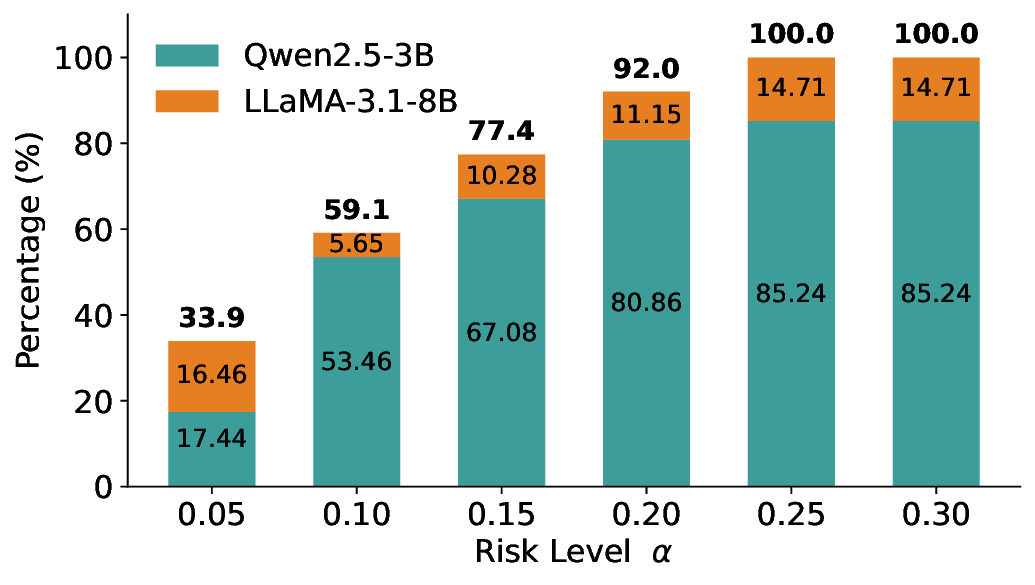

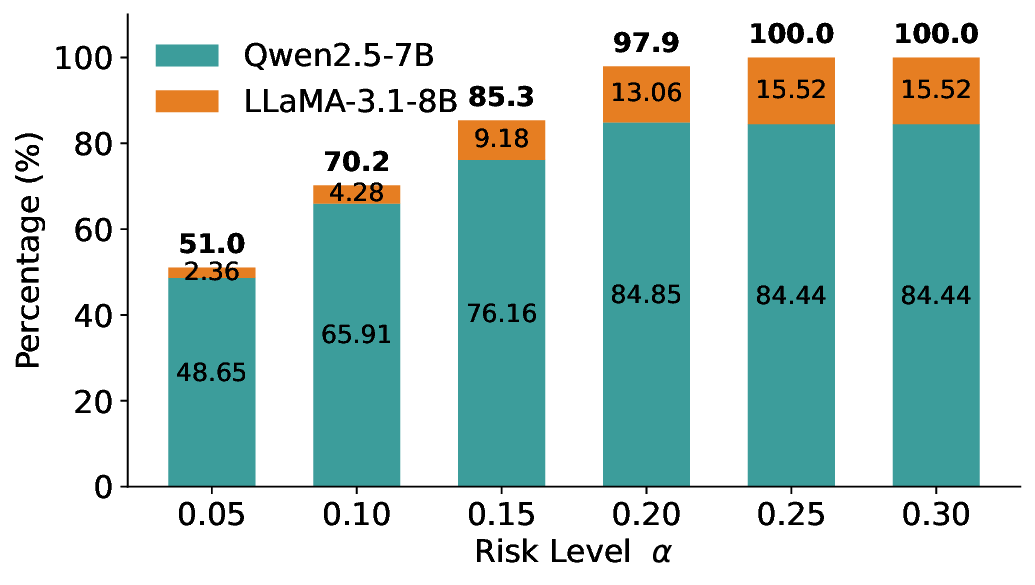

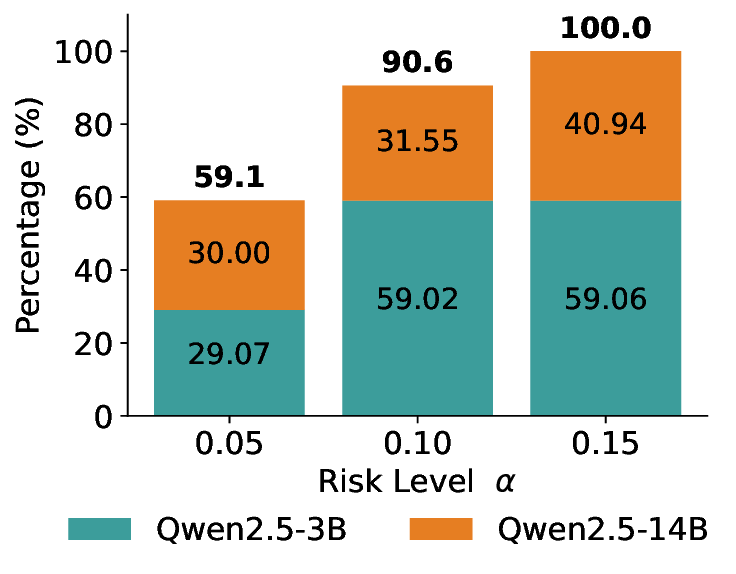

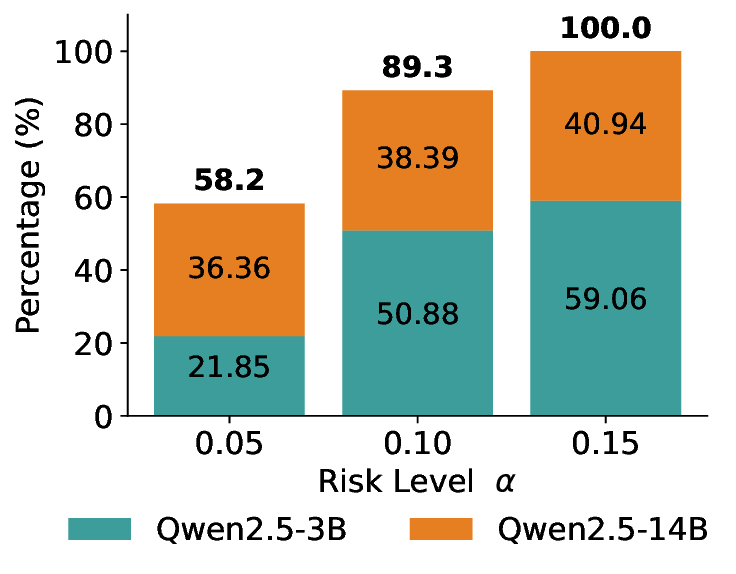

Routing Allocation. We further examine the allocation of accepted test samples under two-model routing. As shown in Figure 7, at different risk levels and model pairs, the distribution of accepted samples adapts to the risk budget and the uncertainty profiles of the models: the primary model handles a substantial portion of the accepted samples when its predictions are sufficiently reliable, while uncertain cases are selectively delegated to the secondary model. This adaptive allocation leads to both higher system-level coverage and improved cost-efficiency under FDR control. For example, at a risk level of α = 0.05, using Qwen2.5-3B alone accepts only 20.3% of the test samples. In contrast, under LEC-Routing with Qwen2.5-3B as the primary model and LLaMA-3.1-8B as the secondary model, the system accepts 33.9% of the samples in total, with 17.44% handled by Qwen2.5-3B and an additional 16.46% selectively routed to LLaMA-3.1-8B-representing a 13.6% absolute increase in accepted samples over using the primary model alone.

Importantly, routing does not trivially favor the secondary model. At the same risk level, Qwen2.5-7B alone accepts 50.7% of the samples, while LLaMA-3.1-8B alone accepts only 33.4%. In this case, LEC-Routing still achieves an acceptance rate of 51.0%, with the majority of samples (48.65%) processed by the more efficient primary model Qwen2.5-7B. This demonstrates that LEC-Routing dynamically balances model usage based on reliability and risk, rather than indiscriminately escalating samples. Overall, these results highlight a principled trade-off between efficiency and cost: depending on the risk level and model characteristics, LEC-Routing maximizes system-level utility by invoking the secondary models only when necessary, while preserving rigorous system-level FDR guarantees.

Furthermore, we demonstrate that LEC-Routing has the potential to increase the effective set of correct predictions under system-level FDR control. Table 2 shows that twomodel routing under LEC-Routing consistently retains more correct samples than using either model alone across all risk levels. For instance, at a risk level of α = 0.05, routing Qwen2.5-3B with LLaMA-3.1-8B admits 1610 correct samples, compared to 965 and 1579 correct samples when using Qwen2.5-3B or LLaMA-3.1-8B alone, respectively. Finally, we illustrate a comparison of the routing behavior between LEC-Routing and UCB-CLP-Routing. As demonstrated in Figure 8, under the same target risk levels, LEC-Routing tends to prioritize the primary model more effectively, while retaining a larger set of accepted samples overall. By contrast, UCB-CLP-Routing exhibits a more conservative allocation pattern, with a higher reliance on the secondary model. These results further suggest that the tighter system-level risk control of our LEC framework can translate into more efficient routing decisions, although the extent of this advantage may vary across settings.

Additional experimental results for both single-model and two-model routing systems are reported in Appendix D.

In this paper, we introduce LEC, a principled formulation that frames selective prediction as a decision problem governed by a linear expectation constraint over selection and error indicators. By directly constraining the expected systemlevel risk, LEC departs from conventional UCB-based approaches that rely on worst-case tail bounds, and instead characterizes a tighter feasible region for admissible decisions. We demonstrate that our framework applies naturally to single-model selective prediction and two-model routing systems, where joint calibration over system-level indicators is essential for reliable risk control. Empirically, LEC consistently achieves valid and tighter test-time FDR control across various closed-ended and open-ended QA and VQA datasets. In routing settings, risk-aware calibration enables adaptive allocation of samples across models and can, in favorable regimes, increase the number of accepted correct predictions relative to single-model deployment, while supporting principled trade-offs between coverage, accuracy, and cost. Overall, LEC provides a general foundation for system-level risk control in selective prediction and routing. Future work may explore tighter characterizations of when routing yields maximal benefits, extend the framework to task-specific risk measures beyond FDR, and integrate LEC with more expressive routing architectures to support reliable decision-making in complex, multi-agent systems.

This work advances the reliable deployment of foundation models by introducing LEC, a novel principled framework for controlling system-level error rates in selective prediction and model routing mechanisms. Rather than treating risk control as a post-hoc statistical correction, LEC formulates selective decision-making as a linear expectationconstrained problem, enabling explicit and finite-sample control over the proportion of erroneous accepted outputs.

From a methodological perspective, LEC provides a unified and model-agnostic interface for risk control that does not depend on specific UQ methods, confidence intervals, or internal model probabilities, which allows risk guarantees to be preserved at the system level, even when individual components differ in architecture, scale, or modality. Therefore, the framework naturally extends from single-model selective prediction to multi-model routing systems without altering the underlying statistical guarantees. At the systems level, LEC supports principled trade-offs between reliability, coverage, and computational cost. By explicitly constraining the expected risk while maximizing accepted decisions, LEC enables systems to defer or escalate uncertain cases only when necessary, making it particularly suitable for cascaded or agentic architectures where multiple models interact. Such settings are increasingly prevalent in real-world applications, including decision support, automated reasoning, and tool-augmented language agents, where average accuracy alone is insufficient to characterize reliability.

More broadly, LEC offers a foundation for integrating foundation models into high-stakes scenarios that require transparent and auditable reliability guarantees. Relying solely on held-out calibration data and exchangeability assumptions, the framework remains applicable in black-box settings and across heterogeneous data sources. We believe this work opens avenues for future research on composable risk control, adaptive model coordination, and uncertainty-aware decision-making in increasingly complex agent systems. (

Since n calibration data points and the given test sample are exchangeable (Angelopoulos & Bates, 2021;Wang et al., 2025e;Angelopoulos et al., 2024), we have

We now make explicit how the calibration sum rewrites in terms of the sorted errors in Eq. ( 5). Recall that for a candidate threshold λ (a) S (a) i

Therefore, for any fixed λ (a) ,

(n) be the sorted calibration uncertainties and err

Rearranging gives

which is exactly

This completes the proof.

Condition on the calibrated threshold pair ( λ(a) , λ(b) ) that is obtained from the calibration set by solving Eq. ( 11). For the test sample (x n+1 , y * n+1 ), recall the system-level selection and error indicators Whenever E S n+1 ( λ(a) , λ(b) ) > 0, the system-level FDR at ( λ(a) , λ(b) ) can be written as

By the exchangeability among calibration and test samples at the level of joint model outputs, i.e., (u

i , err

By the definition of the feasible region Λ 1 Since the routing policy is deterministic and selects at most one model per input, the induced system-level indicators (Si, Zi) also satisfy exchangeability, which is sufficient for our finite-sample guarantees.

on the calibration set. Substituting this inequality into Eq. ( 22) yields Rearranging gives

) . Combining this inequality with Eq. ( 21) implies

If E[S n+1 ( λ(a) , λ(b) )] = 0, the system always abstains, and the inequality holds trivially. This completes the proof.

Suppose we have a collection of M foundation models {G (1) , . . . , G (M ) }, each equipped with an uncertainty score u (m) and threshold λ (m) . A routing policy defines, for each input x, either a unique index r(x) = arg min m∈{1,…,M }:u (m) ≤λ (m) m whose prediction is accepted, or abstention. For any fixed threshold vector λ = (λ (1) , . . . , λ (M ) ), the system induces a selection indicator S i (λ) = 1{sample i is accepted by any one model under λ}

and an error indicator conditioned on accepting any one output

, where ŷi = G (r(xi)) (x i ). Defining the joint indicator Z i (λ) = S i (λ) • err i (λ) = err i (λ), the system-level FDR and its linearization constraint remain

Following the same argument as before, the finite-sample sufficient condition becomes

We denote the feasible threshold region by

Among all feasible threshold vectors, we select the coverage-maximizing solution

which offer valid FDR control to the full routing system.

Our framework extends seamlessly to routing systems with an arbitrary number of models, as long as the routing policy deterministically maps uncertainty scores and thresholds to a unique accepted model output or abstention. The main algorithmic challenge is to search over the multi-dimensional thresholds λ efficiently2 . Through a similar linear expectation transformation, LEC can generalize naturally to a broad class of task-specific risk metrics that take a ratio form.

Details of Utilized Datasets and Models. For the closed-ended CommonsenseQA dataset, we employ both the full training split (9,741 samples) and the validation split (1,221 samples)3 . We remove a small number of samples containing non-ASCII characters in either the query or answer that cannot be encoded by the tokenizer. From the remaining data, we select one QA pair as a fixed one-shot demonstration, which is prepended to the prompt for all other samples. After filtering and prompt construction, we select 10,000 QA instances in total. An example of the complete prompt is presented as follows:

System: Make your best effort and select the correct answer for the following multiple-choice question. For the open-ended TriviaQA dataset, we randomly select 8,000 QA pairs from the validation split of the rc.nocontext subset4 . We also apply a one-shot prompt for each data point. An example of the complete prompt is presented as follows:

System: This is a bot that correctly answers questions. For the open-ended MM-Vet v2 dataset, we adopt the total test split (517 VQA samples)5 for evaluation. An example of the complete prompt is presented as follows:

What is x in the equation? NOTE: Provide only the final answer. Do not provide unrelated details.

For the closed-ended ScienceQA dataset, we utilize the test split (4,241 samples)6 . Due to missing visual inputs in a subset of the data, we retain 2,017 VQA samples for evaluation. An example of the complete prompt is presented as follows: (3) 8B: InternVL2-8B. We omit “-Instruct” and “-HF” when reporting the experimental results.

Due to imperfect instruction-following behavior in some models, a very small number of predictions may be invalid and thus removed during preprocessing. Specifically, in closed-ended tasks, a few model outputs do not strictly follow the prescribed option format, while in open-ended tasks, rare cases may result in empty responses after standard cleaning and post-processing. Consequently, the set of valid evaluation samples can differ slightly across models, although the number of excluded samples is negligible. In the two-model routing setting, we therefore restrict evaluation to the subset of samples that are shared by both models to ensure a fair and consistent comparison. As shown in Table 2, the set of evaluation samples shared between LLaMA-3.1-8B and the two Qwen primary models exhibits a minor discrepancy, stemming from a very small number of invalid predictions that are removed during preprocessing. This difference is negligible in scale and does not materially affect the evaluation or the conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Details of Alignment Criteria. In closed-ended QA or VQA tasks, we can directly determine whether the predicted option is consistent with the ground-truth option. In open-ended settings, following previous work (Duan et al., 2024;Wang et al., 2025c), we estimate the sentence similarity between two answers (ground truth, the most likely answer, or sampled answer) leveraging SentenceTransformers (Reimers & Gurevych, 2019a) with DistillRoBERTa (Sanh et al., 2019) as the backbone.

For bi-entailment (Kuhn et al., 2023;Farquhar et al., 2024;Wang et al., 2025d), we employ DeBERTa-v37 as the Natural Language Inference (NLI) classifier, which outputs logits over three semantic relation classes: entailment, neutral, and contradiction. Two answers are deemed semantically aligned if the classifier predicts entailment for both directions. In addition, we also adopt LLM-as-a-Judge by prompting the Qwen2.5-7B model with the following instruction:

You are an expert evaluator for open-ended QA correctness.

Given a question, a ground-truth answer, and a model’s answer, decide which option best describes the model’s answer: A. correct { semantically equivalent to the ground-truth answer. B. partial { related and contains some correct information but is incomplete or partially wrong. C. incorrect { not compatible with the ground-truth answer.

Respond by selecting exactly one of A, B, or C.

Question: Ground truth answer: Model answer: Answer:

We adopt the partial correctness criterion by default. Note that the statistical validity of our LEC framework is not affected by changes in the alignment criterion of admission function A.

Details of Uncertainty Estimators. In the closed-ended CommonsenseQA dataset, we compute the PE as o -p o log p o , where p o is the probability of the o-th option. In black-box settings, we sample additional 20 answers (i.e., options) and utilize the normalized frequency score as p o . We only compute black-box PE in the closed-ended ScienceQA (VQA) dataset.

In the open-ended TriviaQA (QA) and MM-Vet v2 (VQA) datasets, we sample additional 10 answers by default to compute black-box SE, EigV, Ecc, and Deg. In black-box SE, we perform semantic clustering via the bi-entailment criterion. See Farquhar et al. (2024) for more details of black-box SE. See Lin et al. (2024) for more details of EigV, Ecc, and Deg. For SELF, we compute the length-normalized sentence entropy of the most likely generation. See Duan et al. (2024) for details.

Details of Additional Hyperparameters. In black-box settings, we set the sampling temperature to 1.0 and top-p to 0.9. For both the CommonsenseQA and ScienceQA datasets, limit the model’s output to a single token, since only the option letter is required. For the TriviaQA dataset, we set the maximum output length to 36 tokens. For the MM-Vet v2 dataset, we set the maximum output length to 32 tokens.

As presented in Algorithms 1 and 2, we detail the threshold calibration procedures in single-model selective prediction for two UCB-based approaches and the proposed LEC. Algorithm 3 details LEC-Routing that follows naturally by reformulating the selection and joint indicators at the system level, without altering the overall calibration procedure. Moreover, in the two-model routing setting, rather than selecting the largest feasible threshold pair, we adopt the threshold pair that yields the maximum number of accepted samples. See Jung et al. (2025) for UCB-based routing.

Algorithm 1 UCB-based threshold calibration for single-model selective prediction with PAC-style FDR control

(1) , . . . , u if CHECK satisfies Eq. ( 5) then 11:

Update λ(a) ← λ;

12:

end if 13: end for 14: if λ(a) = NULL then 15:

Return “No feasible threshold for risk level α”; 16: else 17:

Return. λ(a) # Maximum threshold for the best coverage. 18: end if Algorithm 3 Joint threshold calibration via LEC-Routing for two-model routing systems with system-level FDR control

(N ) ) and define candidate set T (a) ← {u

(1) , . . . , u Obtain system-level selection indicator for all i ∈ [N ]:

Obtain system-level joint indicator for all i ∈ [N ]:

10:

Check the system-level finite-sample sufficient condition: CHECK { S i (λ (a) , λ (b) ), Z i (λ (a) , λ (b) ) } N j=1 , α ;

11:

if CHECK satisfies Eq. ( 9) then 12:

Add (λ (a) , λ (b) ) to Λ

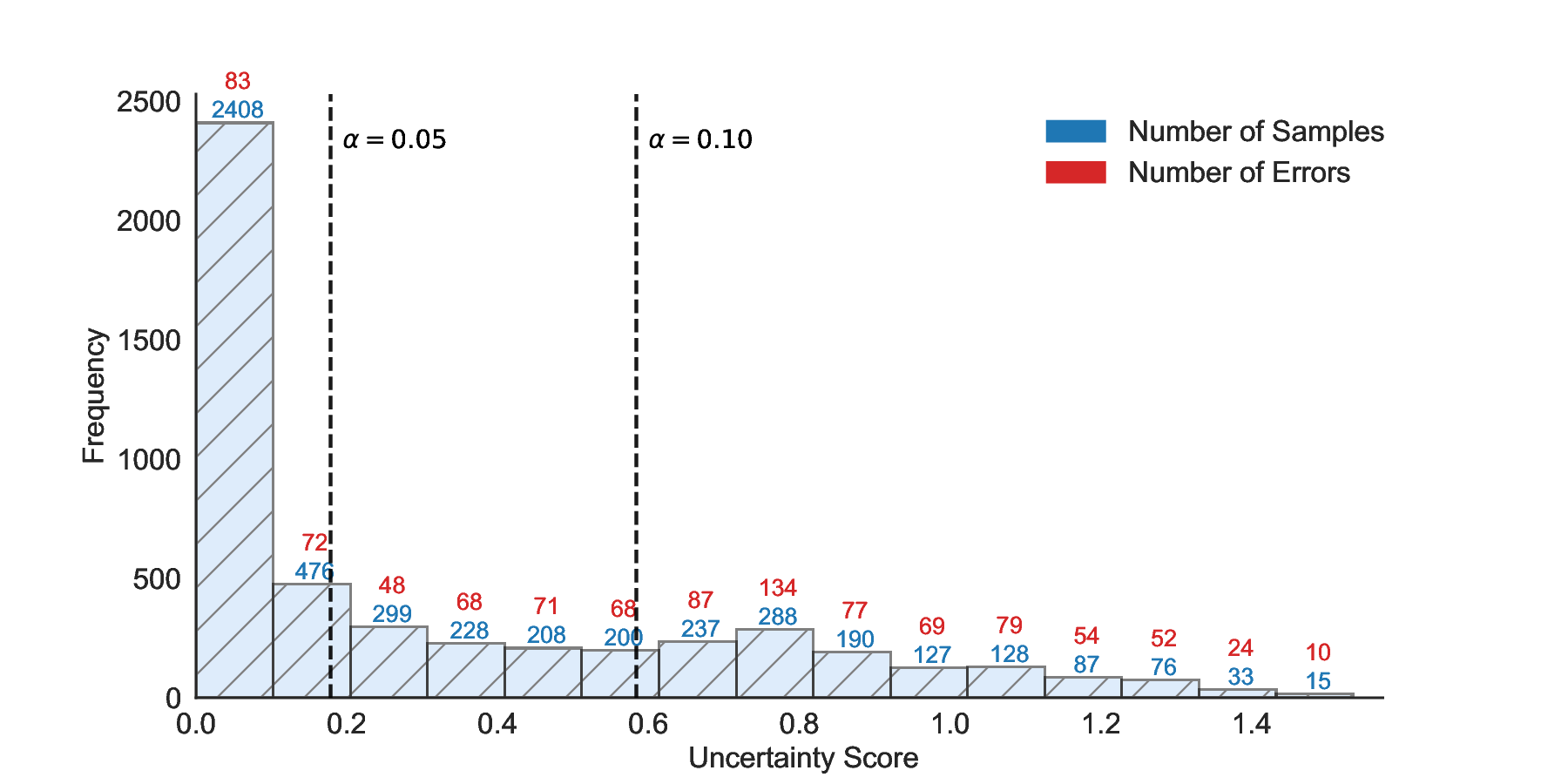

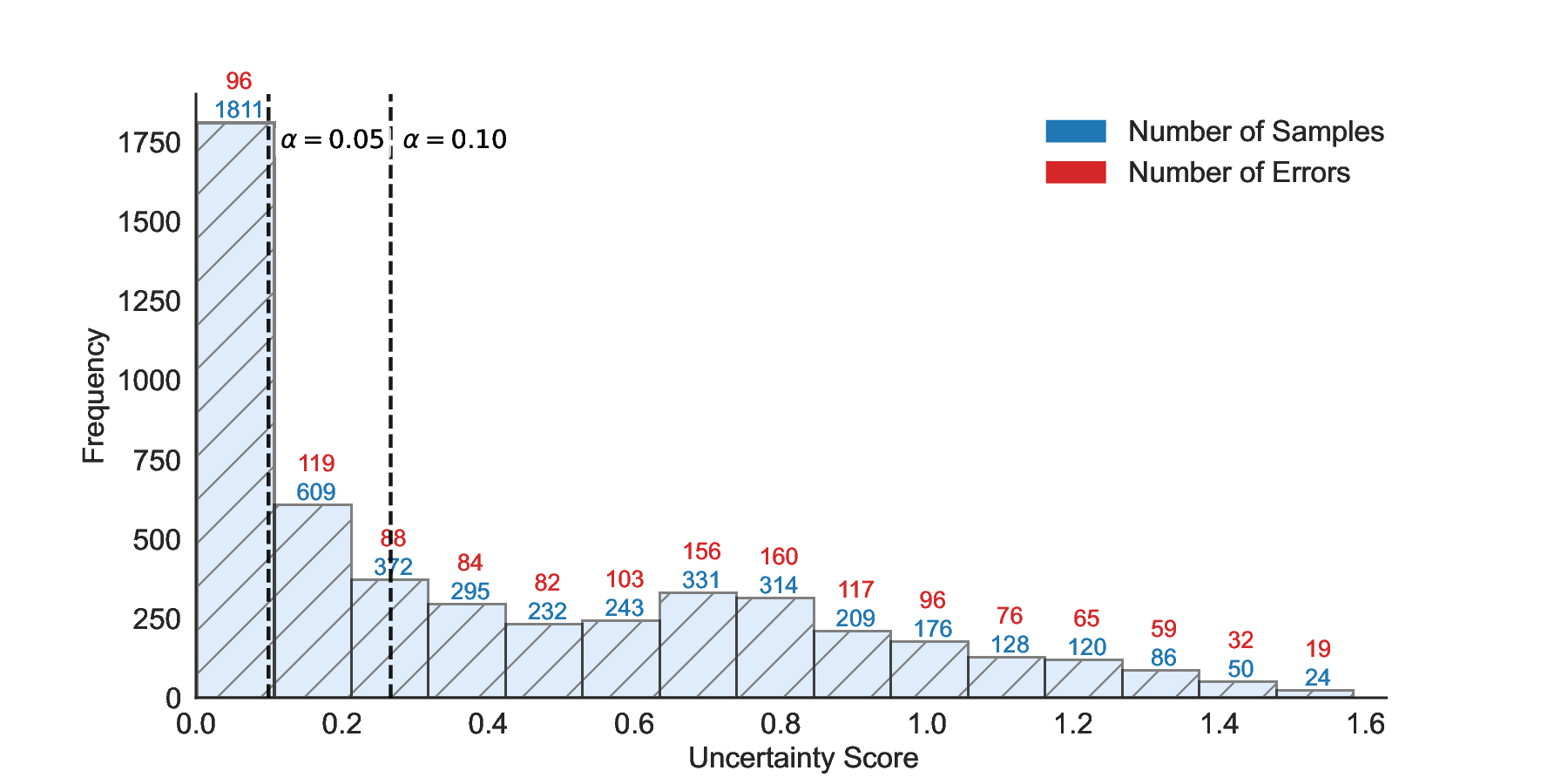

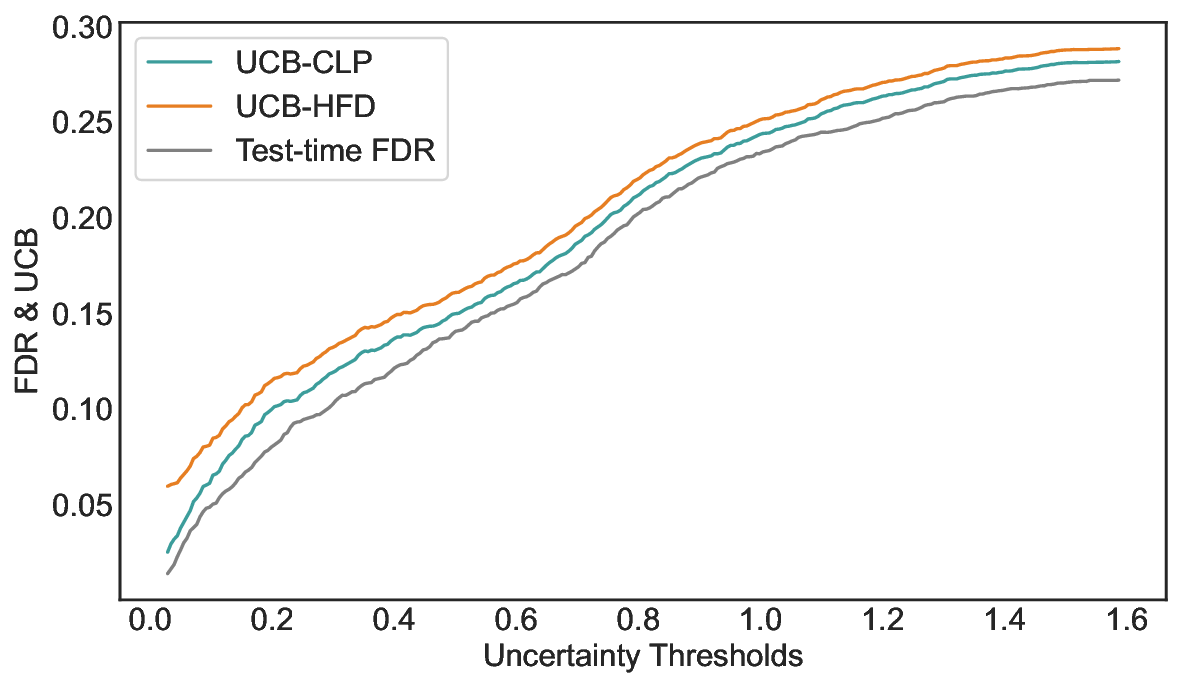

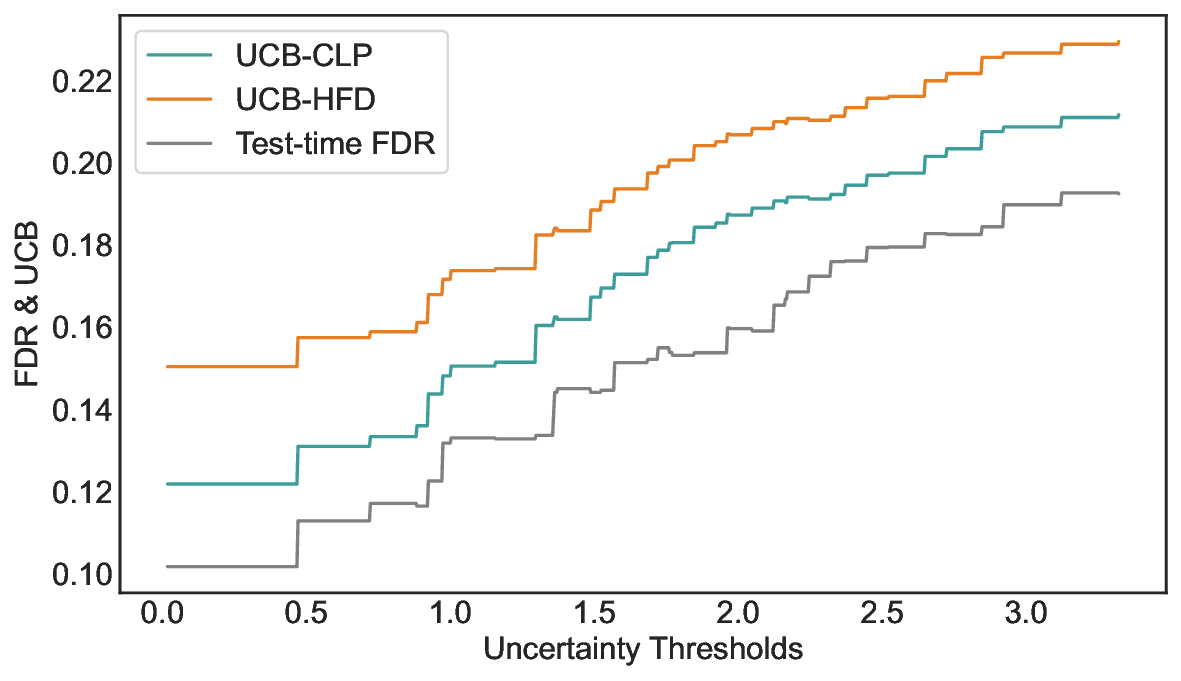

Inherent Conservation of Confidence Intervals. Figure 9 illustrates the gap between the test-time FDR and the UCBs computed on the calibration set across a range of uncertainty thresholds. Specifically, Figure 9 (a) reports results on TriviaQA using LLaMA-3.1-8B with white-box PE, while Figure 9 (b) shows results on CommonsenseQA using Qwen2.5-14B with SE. A key empirical observation is that, across almost all uncertainty thresholds, both Hoeffding-style UCBs and exact Clopper-Pearson UCBs systematically overestimate the corresponding test-time FDR, indicating that the conservativeness is not merely due to loose concentration inequalities, but rather reflects a more fundamental limitation of UCB-based calibration. This behavior can be attributed to the objective of UCB-based methods, which aim to control worst-case tail events with high probability. To satisfy this requirement, the UCB must remain valid even under rare but adversarial realizations of the calibration data, such as observing an unusually low empirical error rate despite a relatively high underlying risk. Power Analysis on CommonsenseQA. Table 3 reports a comprehensive comparison of power on CommonsenseQA across eight LLMs and various risk levels. Consistent with the main results, LEC uniformly achieves higher power than both UCB-based baselines under the same target FDR constraints. This trend holds across all evaluated models and becomes particularly pronounced at low to moderate risk levels, where conservative calibration has the largest impact on sample retention. Notably, for several models, including Vicuna-13B-V1.5, LEC remains feasible at substantially lower risk levels where UCB-based methods either yield significantly lower power or fail to identify valid thresholds. This further highlights the advantage of expectation-level risk control in retaining admissible samples under strict reliability requirements. Uncertainty-Correctness Distribution. Figure 11 visualizes the joint distribution of uncertainty scores and correctness on the test set for LLaMA-3.1-8B and LLaMA-3.1-70B. Each histogram bin reports the number of test samples within a given uncertainty range, along with the corresponding number of incorrect predictions. A key observation is that incorrect predictions are present across nearly all uncertainty intervals, rather than being confined to a small high-uncertainty region. This indicates that selective prediction inherently involves a trade-off between rejecting uncertain samples and retaining correct ones, and that no single uncertainty threshold can perfectly separate correct and incorrect predictions. Importantly, the two models exhibit markedly different uncertainty-correctness profiles. Compared to LLaMA-3.1-8B, LLaMA-3.1-70B assigns lower uncertainty scores to a larger fraction of correct predictions, while maintaining a comparable or lower error density in the low-uncertainty region. As a result, for the same target risk level, the larger model can accept a greater number of correct samples before violating the FDR constraint, leading to consistently higher power. These results reinforce that the performance gains of LEC are driven not only by tighter calibration, but also by its ability to adapt to model-specific uncertainty-correctness characteristics. By directly constraining expected system-level risk, LEC effectively leverages favorable uncertainty distributions to retain more admissible samples, while preserving rigorous statistical validity.

Robustness and Efficiency across UQ Methods and Sampling Sizes on TriviaQA. Figure 12 evaluates LEC on TriviaQA using four different uncertainty estimators (Deg, Ecc, EigV, and SELF). Across all uncertainty methods, LEC consistently achieves tighter FDR control and higher power than UCB-based baselines, demonstrating that the benefits of LEC are orthogonal to the specific choice of uncertainty estimator. Evaluation with LLM-as-a-Judge for Correctness Assessment. Figure 13 reports the test-time FDR and power on TriviaQA when correctness is evaluated using an LLM-as-a-Judge instead of exact string matching or similarity-based metrics. This setting introduces an additional layer of uncertainty, as the correctness labels themselves are noisy and may vary across prompts or judging criteria. Despite this increased label noise, LEC consistently maintains valid FDR control across all evaluated models, with the empirical test-time FDR closely tracking the target risk level and remaining below the theoretical upper bound. More importantly, LEC continues to achieve strictly higher power than both UCB-HFD and UCB-CLP across all models. The gap is especially pronounced for medium-sized models such as Qwen2.5-7B, where UCB-based methods suffer a sharp drop in power at low risk levels, while LEC is able to retain a substantial fraction of correct predictions. This behavior is consistent with the design of LEC: by enforcing a finite-sample linear constraint on the aggregate system behavior, LEC avoids overreacting to spurious or judge-induced errors that disproportionately inflate confidence bounds in UCB-style calibration. Overall, these results demonstrate that LEC remains robust under noisy and subjective correctness evaluation schemes. This robustness is particularly important for open-ended question answering tasks, where exact correctness is often ill-defined and LLM-as-a-Judge-style evaluation is increasingly adopted in practice. Accepted Correct Samples under Two-Model Routing. Table 5 further reports the allocation of accepted samples and the number of accepted correct predictions under two-model routing on the CommonsenseQA dataset. Compared to using either model alone, LEC-Routing consistently increases the number of accepted correct samples across model pairs and risk levels, while maintaining valid system-level FDR control, as demonstrated in Figure 21. At α = 0.05, for example, routing Qwen2.5-7B with LLaMA-3.1-70B under LEC-Routing increases the total acceptance rate from 50.69% (Qwen2.5-7B alone) and 55.57% (LLaMA-3.1-70B alone) to 57.09%, resulting in a higher number of accepted correct samples. Similar trends are observed at α = 0.10 and for the Qwen2.5-14B pairing, where routing yields both higher coverage and more correct acceptances than either individual model. Compared to UCB-based routing methods, LEC-Routing achieves a more favorable balance between allocation efficiency and correctness, reflecting its tighter feasible region under finite-sample guarantees. Overall, these results suggest that joint calibration under the LEC framework can effectively leverage complementary strengths of multiple models to retain more correct predictions than single-model deployment, without sacrificing statistical reliability.

Touvron, H., Lavril, T., Izacard, G., Martinet, X., Lachaux, M.-A., Lacroix, T., Rozière, B., Goyal, N., Hambro, E., Azhar, F., et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971, 2023. Wang, G., Cheng, S., Zhan, X., Li, X., Song, S., and Liu, Y. Openchat: Advancing open-source language models with mixed-quality data. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2024a. Wang, Z., Duan, J., Yuan, C., Chen, Q., Chen, T., Zhang, Y., Wang, R., Shi, X., and Xu, K. Word-sequence entropy: Towards uncertainty estimation in free-form medical question answering applications and beyond. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, 2025d. Zheng, L., Chiang, W.-L., Sheng, Y., Zhuang, S., Wu, Z., Zhuang, Y., Lin, Z., Li, Z., Li, D., Xing, E., et al. Judging llm-as-a-judge with mt-bench and chatbot arena. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2023. n+1 , uncertainty score u

University of Electronic Science and Technology of China

Technical University of Munich

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Shandong University

Tongji University

City

LEC formalizes selective prediction as a decision problem with a global risk constraint, where for each sample the system decides whether to accept, route (two or more models), or abstain from, while ensuring that the system-level FDR does not exceed the user-specified risk level α. To support this decision process, LEC employs an optimization step to determine the threshold(s): it searches for the value that maximizes the number of accepted samples on the calibration set, subject to the established finite-sample sufficient condition.

Source files of the CommonsenseQA dataset.

Source files of the TriviaQA dataset.

Source files of the MM-Vet v2 dataset.

Source files of the ScienceQA dataset.

We use DeBERTa-v3-large-mnli-fever-anli-ling-wanli. Different from DeBERTa-large(He et al., 2021) employed in previous research(Lin et al., 2024), the three dimensions of its output logits correspond to entailment, neutral, and contradiction, respectively.

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.