Improved Training Mechanism for Reinforcement Learning via Online Model Selection

📝 Original Info

- Title: Improved Training Mechanism for Reinforcement Learning via Online Model Selection

- ArXiv ID: 2512.02214

- Date: 2025-12-01

- Authors: Aida Afshar, Aldo Pacchiano

📝 Abstract

We study the problem of online model selection in reinforcement learning, where the selector has access to a class of reinforcement learning agents and learns to adaptively select the agent with the right configuration. Our goal is to establish the improved efficiency and performance gains achieved by integrating online model selection methods into reinforcement learning training procedures. We examine the theoretical characterizations that are effective for identifying the right configuration in practice, and address three practical criteria from a theoretical perspective: 1) Efficient resource allocation, 2) Adaptation under non-stationary dynamics, and 3) Training stability across different seeds. Our theoretical results are accompanied by empirical evidence from various model selection tasks in reinforcement learning, including neural architecture selection, step-size selection, and self model selection. While theoretical model selection guarantees have been established across various sequential decisionmaking problems [📄 Full Content

Model Selection offers a remedy to the theory-practice mismatch that arises from misspecification. Given access to a set of base agents, the model selection algorithm, which we will refer to as the selector, interacts with an environment and learns to select the right model for the problem at hand. The algorithmic goal of model selection is to guarantee that the meta-learning algorithm for the selector has performance comparable to the best solo base agent, without knowing a priori which agent is best suited for the problem at hand.

We consider episodic reinforcement learning with a finite horizon H, which is formalized as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) ⟨S, A, R, P, ρ⟩. Here, S denotes the state space, A is the action space, R : S × A → R is the reward function, P : S × A → [0, 1] is the environment transition probabilities, and lastly ρ : S → [0, 1] is the initial state distribution. Denote π : S → ∆(A) as the policy of the agent. The agent interacts with the MDP according to the following procedure: At each step h ∈ [H], the agent takes action a h ∼ π(s h ), observes r h ∼ R(s h , a h ) and move to state s h+1 ∼ P(s h , a h ). The value of the policy is defined as,

Here, the expectation is with respect to the stochasticity of the interaction procedure. The goal of the agent is to learn an optimal policy defined as,

where Π denotes the policy class. The policy class is commonly parameterized as Π = {π θ : θ ∈ Θ}, where π * = π(θ * ). The state value function V : S → R and state-action value function Q : S × A → R with respect to policy π are defined as,

From the algorithmic perspective, the agent does not try to directly solve the optimization problem in 2, as it can be computationally expensive, and in certain cases intractable. Instead, RL algorithm iteratively update the parameter θ to optimize the state-value function V π (s) or the state-action value function Q π (s, a). Much of RL is devoted to designing algorithms with effective and sample-efficient update rules. But the most prominent themes are optimizing the Algorithm 1: Selector (D 3 RB)

through the policy gradient method [Williams, 1992, Schulman et al., 2017], or optimizing the state-action value function by temporal difference methods [Watkins andDayan, 1992, Mnih et al., 2015], which we include in Appendix C.2. The details of the RL algorithm is not the focus this work, as we will show later that online model selection methods can be integrated into any RL training procedure.

We consider the online model selection problem where the selector has access to a set of M base agents,

, the selector picks base agent i t ∈ [M ] according to its selection strategy. The selector rolls out the policy of the base agent π it t for one episode and collects the trajectory, τ = {(s h , a h , r h )} H h=1 according to the procedure explained in 2.1. The selector then uses this trajectory to update its selection policy, and forwards it to the base agents so that it can update its internal policy π i t . Notation:

as the number of rounds that base agent B i has been selected up to round t ∈

, where r l is the episodic reward at round l ∈ [T ], and ūi t =

where v * = max π∈Π v(π). The total regret of the selector after T rounds is,

The selector has access to base agents as sub-routines, and sequentially picks them in a meta-learning structure.

Online Model Selection in Reinforcement Learning deals with the problem of selecting over a set of evolving policies. In this section, we characterize how the selector keeps track of the performance of base agents over time, and what is the right measure for that purpose. Importantly, we use this measure to specify the algorithmic objective of model selection.

as the regret coefficient of the well-specified base agent. The total regret incurred by the metaalgorithm should satisfy,

with high probability.

Algorithm 1-left shows the Doubling Data Driven Regret Balancing algorithm (D 3 RB) [Dann et al., 2024] that is the selector of interest in this paper. Algorithm 1-right is the training mechanism, that shows how to integrate a selector into the RL training loop. The training mechanism is analogous to the standard agent-environment interaction protocol in RL with minimum interventions from the selector. As a result, this framework can be integrated into any RL algorithm. The choice of selector is also not limited to D 3 RB, and other model selection algorithm can be used as long as they follow a similar interface to Algorithm 1-left. With that being said, the choice of selector matters in the performance and efficiency of the training mechanism. We choose D 3 RB that satisfies the following high probability model selection guarantee, Theorem 2 ( [Dann et al., 2024]). Denote the event E,

for a parameter δ and universal constant c. Under event E, the total regret incurred by data-driven regret balancing (D 3 RB) after T rounds satisfies,

With probability 1 -δ.

This bound implies that D 3 RB is optimal as it matches the lower bound of online model selection in [Marinov andZimmert, 2021, Pacchiano et al., 2020c].

. This potential function estimates a data-adaptive upper bound on the realized regret. Here, di t is an active estimate of the true regret coefficient d i t . At each round t ∈ [T ], the selector picks the base agent with minimum balancing potential i t = arg min i∈[M ] ϕ i t . It acts according to the policy of the selected base agent π it t for one episode, collects the trajectory τ = {(a h , s h , r h )} H h=1 , and updates policy π it t according to the update rule of the RL algorithm. The selector updates the statistics of the selected base agent, n it t , and u it t , and doubles dit t if the agent is misspecified.

We provide a detailed explanation in appendix A.1 on why this test can determine misspecification of a base agent. In the following sections, we analyze the properties of the D 3 RB+RL training mechanism in theory and demonstrate the effectiveness in experiments. The policy in deep RL is parametrized by a neural network, which serves as an expressive function approximator, enabling decision making in high-dimensional state spaces that was otherwise not possible by linear function approximation or tabular RL. The choice of network architecture highly affects the agent’s performance as it determines the representational capacity of the agent.

To validate the practical efficiency of our mechanism, we run experiments for the neural architecture selection task in DQN agents for 4 different Atari environments Mnih et al. [2015]. We pair the D 3 RB selector with three base agents that are identified with their unique Q-network architecture. Figure 2 and 3 depict the results of the neural architecture selection task and the Q-network architecture of each base agent respectively. To better see the progressive performance of the selector, we also included the independent execution of base agents. We observe that the performance of base agents varies drastically depending on the architectural choice, as base agent B 3 is failing in almost all of the environments, B 1 has sub-optimal performance, and B 2 is the oracle-best. Importantly, the reward curve of the model selection approach shows that the D 3 RB selector is able to reach the performance of the oracle-best base agent, confirming the theoretical objective of model selection 9 in practice. In the following theorem, we derive the relationship between the allocated compute and regret coefficient of each base learner under Data-Driven Model Selection. Theorem 4. Denote α i t as the fraction of time that base agent B i ∈ B has been selected up to round t, and d i t as the regret coefficient 1 of B i at time t,

then, data-driven model selection (D 3 RB) satisfies,

Proof. Appendix A.2

In this section, we consider the step size selection task in RL, where we are interested in adaptively selecting the right step-size for a given RL problem. We use this task to answer why bandit algorithms are insufficient to perform model selection for RL agents and compare data-driven model selection methods with other baselines.

As an algorithmic counterpart to online model selection, consider the problem of Multi-Armed Bandits (MAB) [Lattimore and Szepesvári, 2020] where the learner interacts with a finite set of arms. One can consider to use a MAB algorithm for the model selection problem, where each arm is a base learner and the MAB algorithm acts as a selector. We argue that standard Bandit algorithms with regret-minimization objective are insufficient to perform model selection for RL agents. We observe that UCB is overcommitting to a base agent that was optimal at the initial stage of training, but fails to remain explorative and adapt to new step sizes that are optimal towards the end. We include the selection statistics of all algorithms in Appendix B.1. We further analyze the results of the Classic algorithm and the effect of misspecification test in Appendix 2.1.

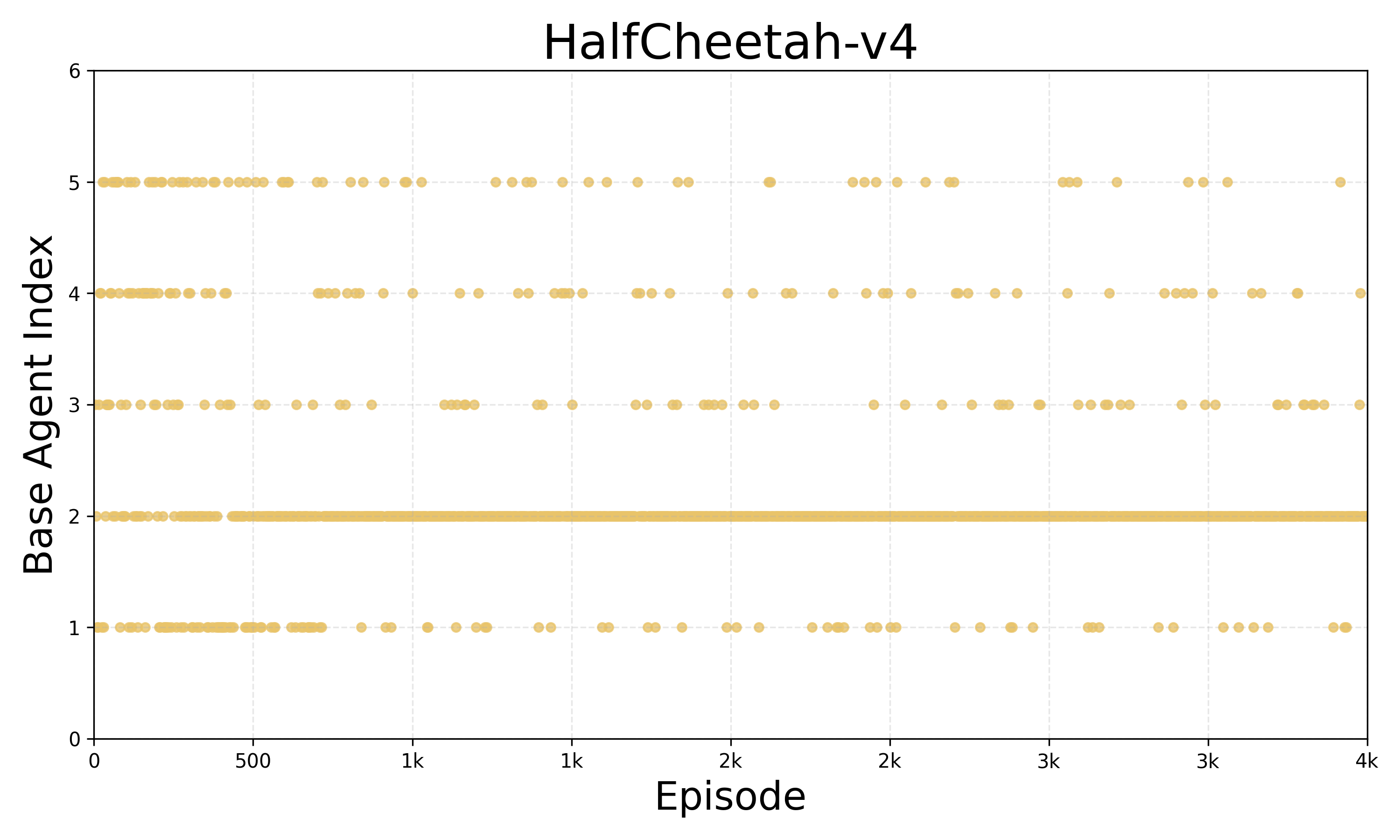

Self-model selection refers to the setting where base agents have identical configurations but are executed with different initial randomization (seed). This setting can stabilize the training of RL algorithms whose performance is highly sensitive to the seeding. We show that by combining certain number of base agents that each fail with a fixed probability, self model selection can capitalize on the successful runs and achieve its bound. The following theorem formalizes this property, Theorem 5. Let δ ∈ (0, 1), and R ⋆ (t, δ) : ([T ], (0, 1)) → R + be a function satisfying

Suppose a learning agent B satisfies,

for some γ(δ) ∈ (0, 1). Then, for M = ⌈ log(δ) log(γ(δ)) ⌉, D 3 RB achieves the bound,

with probability at least 1 -δ.

Proof. Appendix A.3

5 Discussion and Future Work

The theoretical guarantee 11 of data-driven model selection reflects that the regret of the selector grows linearly with the number of base agents M . This is a barrier for deploying these methods to large-scale model selection tasks and incentivizes designing methods with improved dependency on M . Prior work of [Kassraie et al., 2024] has studied this problem for the case of linear bandits, but the question remains open for RL.

One can consider a similar model selection framework to ours, where base agents can communicate or share data. From the algorithmic perspective, a natural idea is to use importance sampling to update the policy of one base agent with the trajectory collected by another base agent. We discuss this more in details in Appendix A.4, but we leave the theoretical analysis of this setup as future work.

Apart from the model selection tasks studied in this paper, prior work has studied online reward selection [Zhang et al., 2024] in policy optimization methods. One can consider other practical model selection tasks, such as selection of exploration strategy or selection of pretrained policy.

This work presents a principled mechanism to improve the efficiency of RL training procedure via online model selection. We studied data-driven model selection methods, how they characterize misspecification of base agents, and their theoretical guarantees. We showed, through theoretical analysis and empirical evaluation, that these methods 1) learn to adaptively direct more compute towards the base agents with better realized performance, 2) adapt to new optimal choices under non-stationary dynamics, and 3) enhance training stability. In addition, we validated these properties on a range of practical model selection tasks in deep reinforcement learning.

The misspecification test determines whether the bound di t n i t matches the realized performance of the agent in a principled manner. For any base agents j ∈

For a well-specified base agent i ∈ [M ] that satisfies its regret upper bound,

Therefore, a well-specified agent i should satisfy,

and otherwise the agent is misspecified, resulting in test 12. Triggering this misspecification test implies that the bound di t n i t is too small to bound the realized regret of the agent and hence he algorithm doubles the estimated regret coefficient di t .

We reuse the following lemmas from [Dann et al., 2024] to prove Theorem 4.

Lemma 6. In event E 10, for each base agent i ∈ [M ] , the regret multiplier di t in algorithm 1-left satisfies, di t ≤ 2d i t , ∀t ∈ N (15) Lemma 7. The potentials in Algorithm 1-(left) are balanced at all times up to a factor 3, that is for all t ∈ [T ],

Proof of Theorem 4 By Lemma 7, the potentials in algorithm satisfy,

Rearrange,

By lemma 6, we have di

For all t ∈ [T ] and a fixed j ∈ [M ],

Rearranging yields the final result in theorem 4,

A.3 Proof of Theorem 5

Proof of Theorem 5: Suppose agent B satisfies its theoretical upper bound with probability at least 1 -γ(δ),

Then, if we combine M independent base agents of type B, the probability of at least one of them succeeding is larger than 1 -γ(δ) M . Therefore, self-model selection requires M base agents to achieve its bound with probability 1 -δ,

A.4 Sharing data via Importance sampling Theorem 8. Consider the case of episodic RL, where we roll out policy π i , and collect a trajectory τ = (s 1 , a 1 , r 1 , . . . , s T , a T , r T ) ∼ P i (τ ). Here, P i (τ ) is the joint distribution over the trajectory τ under policy π i ,

Then,

is an unbiased estimate of the discounted episodic reward that we would’ve collected under π j .

Proof. By definition,

Proposition 9. For a given trajectory τ = {(s t , a t , r t )} T t=1 collected by policy π i ,

is the importance sampling ratio for the discounted episodic reward that we would have collected under policy π j .

Proof.

We consider the role of the misspecification test in the performance of model selection algorithms. We analyze and compare two of the algorithms, D 3 RB and Classic Balancing, that select base agents by performing a misspecification test.

Recall the set of base agents, B = {B 1 , . . . , B M } and suppose B i has a high-probability upper bound R i (t, δ),

Suppose B i is an instance of a sequential decision-making algorithm with high-probability regret guarantee R i (t, δ).

Using these theoretical regret bounds, we can perform a similar misspecification test to 12,

At round t, the Classic Balancing algorithm selects the base agent with minimum regret bound i t = arg min i∈[M ] R(t, δ), eliminating the base agents that are flagged as misspecified by test 26. Note that, the difference between tests 12 and 26 is that one is performed based on the theoretical bound, and the other is performed using the data-adaptive regret bound actively estimated by realized rewards. The drastic difference between the performance of D 3 RB and Classic Balancing selectors in figure 4 highlights the role of designing data-adaptive model selection algorithms versus selectors that perform upon theoretical bounds on the expected performance of the agent.

Here, we include the selection statistics plot for the rest of algorithms in experiment B.1. The following is the detailed architectural choice of three base agents in experiment. 4.1. The second architecture has the configuration with best realized performance. The first architecture, roughly shares the same number of parameters, but only has one convolutional layer, limiting the agents ability in tasks that require temporal reasoning. The third architecture shares that same number of layers to the second one, but has less parameters that limits the representational capacity of the agent.

B where D is the experience replay buffer and θ is a frozen parameter set named target parameter. Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) [Schulman et al., 2017] and Deep Q-Networks (DQN) [Mnih et al., 2015] follow the first and second approaches, respectively.

7 nn . ReLU () , 8 nn . Flatten () , 9 nn . Linear (3136 , 512) , 10 nn . ReLU () , 11 nn . Linear (512 , env . single_action_space . n ) , 7 nn . ReLU () , 8 nn . Flatten () , 9 nn . Linear (392 , 32) , 10 nn . ReLU () ,

📸 Image Gallery