RecruitView: A Multimodal Dataset for Predicting Personality and Interview Performance for Human Resources Applications

📝 Original Info

- Title: RecruitView: A Multimodal Dataset for Predicting Personality and Interview Performance for Human Resources Applications

- ArXiv ID: 2512.00450

- Date: 2025-11-29

- Authors: Amit Kumar Gupta, Farhan Sheth, Hammad Shaikh, Dheeraj Kumar, Angkul Puniya, Deepak Panwar, Sandeep Chaurasia, Priya Mathur

📝 Abstract

Automated personality and soft skill assessment from multimodal behavioral data remains challenging due to limited datasets and methods that fail to capture geometric structure inherent in human traits. We introduce RE-CRUITVIEW, a dataset of 2,011 naturalistic video interview clips from 300+ participants with 27,000 pairwise comparative judgments across 12 dimensions: Big Five personality traits, overall personality score, and six interview performance metrics. To leverage this data, we propose Cross-Modal Regression with Manifold Fusion (CRMF), a geometric deep learning framework that explicitly models behavioral representations across hyperbolic, spherical, and Euclidean manifolds. CRMF employs geometryspecific expert networks to capture hierarchical trait structures, directional behavioral patterns, and continuous performance variations simultaneously. An adaptive routing mechanism dynamically weights expert contributions based on input characteristics. Through principled tangent space fusion, CRMF achieves superior performance while training 40-50% fewer trainable parameters than large multimodal models. Extensive experiments demonstrate that CRMF substantially outperforms the selected baselines, achieving up to 11.4% improvement in Spearman correlation and 6.0% in concordance index. Our RECRUITVIEW dataset is publicly available at https : / / huggingface . co / datasets / AI4A-lab/RecruitView.📄 Full Content

General-purpose LMMs (MiniCPM-o [1], VideoL-LaMA2 [2], Qwen2.5-Omni [3]) offer breadth but are not tuned for fine-grained social inference. Conventional fusion maps all modalities to a single Euclidean latent via concatenation or vanilla attention, ignoring modality-specific geometry. A single latent geometry limits representational adequacy.

Progress is also constrained by supervision: existing datasets are noisy, weakly controlled, and often not domain-specific; they typically lack multi-trait personality and interview-related metrics, instead relying on direct scalar ratings that are sensitive to scale use and inter-rater variability. To address this, we introduce RECRUITVIEW-Recorded Evaluations of Candidate Responses for Understanding Individual Traits-a multimodal interview corpus of 2,011 clips from more than 300 sessions, each aligned to one of 76 questions. Clinical psychologists provided about 27,000 pairwise comparisons between answers to the same prompt, which we convert into continuous scores for 12 targets, namely the Big Five traits [4], an overall personality score, and six interview performance metrics, using a nuclear-norm-regularized multinomial logit model. This protocol reduces rater calibration biases and yields reliable regression labels.

We propose Cross-Modal Regression with Manifold Fusion (CRMF), a geometry-aware framework that projects fused multimodal features to hyperbolic, spherical, and Euclidean spaces, processes each with a geometry-specific expert, and aggregates them through input-adaptive routing with geometry-aware attention and tangent-space fusion. This design preserves manifold consistency while enabling input-conditioned combination for multi-target regression. The contribution of this work is fourfold: (i) RE-CRUITVIEW, a multimodal interview dataset with psychometrically grounded labels derived from pairwise judgments mapped to continuous scores, covering 12 targets across personality and performance; (ii) CRMF, a principled geometry-aware fusion framework that learns in hyperbolic, spherical, and Euclidean spaces; (iii) an adaptive routing and geometry-aware attention mechanism with tangent-space fusion for input-conditioned combination of geometric experts; and (iv) a comprehensive evaluation demonstrating consistent gains over recent LMM baselines on all metrics.

Automated personality and performance assessment has relied on datasets such as ChaLearn [5] and POM [6], which advanced the field but remain limited by controlled settings and narrow labeling scopes. Later efforts like YouTube Personality [7] and Interview2Personality [8] moved toward more naturalistic or interview-style data yet still suffer from smaller scale, scripted responses, and subjective absolute ratings. However, RECRUITVIEW is an in-the-wild interview dataset, where labels are obtained via pairwise comparisons, yielding consistent continuous scores. Beyond the Big Five and an overall personality index, RECRUITVIEW annotates performance dimensions (e.g., confidence, communication), enabling joint modeling of personality and interview behavior.

Multimodal fusion has been extensively studied for affective computing and personality recognition. Early work focused on feature-level concatenation [9] or attentionbased aggregation [10,11]. Transformer-based architectures have recently dominated this space, with methods like MULT [10] employing cross-modal attention for temporal alignment. However, these approaches operate entirely in Euclidean space, potentially missing important geometric structure in behavioral data.

Recent large multimodal models have shown remarkable zero-shot and few-shot capabilities.

MiniCPMo [1] employs an end-to-end training paradigm with modality-adaptive modules, while VideoLLaMA2 [2] introduces spatial-temporal visual token compression for efficient video understanding. Qwen2.5-Omni [3] extends text-centric LLMs with native audio-visual understanding through cross-attention fusion. Despite their generalpurpose success, these models lack task-specific inductive biases for personality assessment and are not optimized for capturing the geometric properties of behavioral traits.

Geometric deep learning extends neural networks to non-Euclidean domains. Hyperbolic neural networks [12,13] leverage the exponentially growing capacity of hyperbolic space to model hierarchical data, showing benefits for treestructured tasks and knowledge graph reasoning. Spherical networks [14,15] operate on the unit sphere, naturally suited for directional data and rotational equivariance. Recent work has explored mixed-curvature spaces [16,17] that combine multiple geometries, though primarily for representation learning rather than multimodal fusion.

Manifold-valued neural networks [18,19] perform operations directly on Riemannian manifolds, ensuring geometric consistency. However, these methods have seen limited application in behavioral analysis. Our work is the first to systematically leverage multiple geometric manifolds for multimodal behavioral assessment with learned adaptive fusion.

Mixture-of-experts (MoE) models [20,21] decompose complex tasks into specialized sub-networks selected by a gating function. Traditional MoE aims for sparse activation to increase model capacity efficiently. Recent work has extended MoE to multimodal settings [22,23] and to geometric spaces [19]. However, existing geometric MoE methods typically focus on sparsity for computational efficiency rather than complementary geometric reasoning. Our routing mechanism differs fundamentally: rather than encouraging specialization, we promote diversity to leverage complementary geometric views of behavioral data, with all experts contributing to the final prediction through learned weighting.

To satisfy the critical necessity of a psychometrically robust dataset to analyze multimodal interview performance and personality, we introduce RECRUITVIEW. This novel dataset comprises 2,011 video segments sampled from 331 distinct interview sessions. Specifically developed to facilitate training and testing on demanding, human-centered traits, it provides robust, continuous labels on 12 distinct targets. The dataset’s key contribution is in the form of an annotation method through pairwise ratings by clinical psychologists to mitigate rater bias and provide robust, continuous scores. The following sections describe the deliberate process of developing it in stages from stimulus creation to final form of data.

The creation of RECRUITVIEW followed a two-phase approach: creation of a broad-based question repository to be used as a prompter, and the procurement of video replies by a diverse group of respondents.

Our dataset has as its base a specially selected pool of queries crafted to elicit responses suitable to human resources evaluation and personality rating. For this purpose, we carried out an exhaustive compilation exercise from a variety of sources. We went through public domain material on interview preparation by market leaders, analyzed frequently posed queries on professional networking platforms, and closely interacted with clinical psychologists. This made the queries relevant not only in the context of professional hiring but also well suited to exploring the underlying Big Five personality dimensions.

This procedure gave rise to 76 standard interview questions (the full list of questions is available in Appendix A.1). The questions were then systematically and in a balanced manner sorted into 15 individual sets for convenience in the collection of data. There were five individual questions in each set and a typical opening question (“Introduce yourself” or “Tell me about yourself”), thereby establishing a comparable baseline in the majority of interviews but facilitating greater query variety within the dataset.

Participants were students from various Manipal universities, who responded via a custom web platform and were randomly assigned to one of 15 question sets. Interviews were recorded in diverse in-the-wild settings (e.g., classrooms, private residences). Implementation details of the platform are provided in Appendix A.2. Data collection and use followed institutional ethical approval processes; detailed ethics, consent, and riskmitigation discussion is provided in Appendix B.

To ensure consistency and psychometric reliability in subjective evaluations, we employed a pairwise comparison protocol inspired by prior multimodal labeling frameworks such as the ChaLearn dataset [5,24]. Instead of assigning absolute scores, clinical psychologists were presented with two clips responding to the same interview question and asked to identify which participant better demonstrated a target attribute, for example, “Who appears more confident?” Annotators could also indicate a tie when both clips were judged equivalent. This comparative design mini-mizes calibration bias, reduces inter-rater variability, and enhances reliability in perceptual assessments [25]. The protocol was applied across twelve target dimensions covering the Big Five personality traits (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism), Overall Personality, and six interview or performancerelated metrics: Interview Score, Answer Score, Speaking Skills, Confidence Score, Facial Expression, and Overall Performance. In total, approximately 27,310 pairwise judgments were collected, forming the basis for deriving continuous and psychometrically grounded labels.

We evaluated several frameworks for converting pairwise judgments into continuous labels, including Elo rating [26], Bradley-Terry-Luce (BTL) [27,28], TrueSkill [29], and Glicko-2 [30]. While these models are widely used in ranking applications, they either assume strong independence across traits or lack convex formulations with clear identifiability guarantees. After empirical comparison (results in Appendix A.3), we selected the Multinomial Logit (MNL) [31] model with nuclear norm regularization, which offered both strong theoretical grounding and robust empirical performance on our dataset. Each video j is associated with a latent utility θ j ∈ R. For a comparison between clips j 1 and j 2 , the MNL model defines the probability that j 1 is preferred as

Letting X (i) denote the design matrix for comparison i and y i ∈ {0, 1} its observed outcome, the normalized loglikelihood across n comparisons is

(2) where Θ ∈ R N ×T is the matrix of utilities across N videos and T = 12 targets.

Recovering utilities requires regularization to address limited sampling and correlations across traits. We therefore estimate Θ by solving the convex program

where ∥ • ∥ * denotes the nuclear norm [32], L is the Laplacian of the comparison graph, and Ω constrains identifiability (e.g., centering utilities). The Laplacian-induced nuclear norm encourages low-rank structure while respecting the blockwise nature of the pairwise comparisons (samequestion groups).

We solve this convex program using first-order proximal methods with singular value shrinkage [33], implemented in cvxpy1 with an SCS2 solver. Step sizes are adapted with the Barzilai-Borwein [34] rule to accelerate convergence. The resulting Θ provides continuous, psychometrically grounded labels for all 12 target dimensions.

The RECRUITVIEW dataset comprises 2,011 multimodal samples, each representing a candidate’s response to one of 76 interview questions. Each sample is structured to facilitate comprehensive multimodal analysis through three primary components:

• Video: High-resolution recordings stored in compressed MP4 format at 30 FPS. The dataset’s average video duration is approximately 30 seconds. • Audio: High-fidelity audio tracks extracted from videos (mono channel). • Transcript: Verbatim speech-to-text transcriptions automatically generated using Whisper-large-v33 [35].

Metadata and Annotations: All annotations and metadata are organized in a structured JSON format. Each entry contains a unique identifier, video filename, interview question, quality indicators (video quality, duration category), user number and the 12 continuous target scores derived from the pairwise comparison protocol (see Appendix A.8 for a complete sample entry). This unified structure ensures seamless integration across modalities while maintaining data privacy and facilitating reproducible research workflows.

The primary task enabled by the RECRUITVIEW dataset is multimodal regression. Given a video clip of a candidate’s response, the goal is to predict the 12 continuous scores corresponding to their personality traits and interview performance. Models leverage the modalities available from the data: visual (video frames), auditory (speech acoustics), and linguistic (transcribed text).

The RECRUITVIEW corpus comprises 2,011 video segments, sourced from over 300 unique participants responding to a bank of 76 curated interview questions. The dataset’s foundation is a set of approximately 27,000 pairwise judgments provided by clinical psychologists. A key design characteristic is its “in-the-wild” data collection via a custom-built web-based platform. This methodology encouraged participation in naturalistic settings, resulting in significant variability in lighting conditions, background environments, and audio quality. This inherent diversity ensures high ecological validity, a critical feature for developing robust models that can generalize beyond controlled laboratory conditions. Figure 1 provides a summary of the video duration and quality categories, illustrating the distribution of these factors across the corpus.

To provide a more granular view of the dataset’s temporal and linguistic composition, Figure 2 illustrates the distributions for video segment duration and the corresponding transcript word counts. The video durations (Figure 2, left) follow a right-skewed distribution, with a primary mode

To understand the relationships among the 12 target dimensions in RECRUITVIEW, we computed Spearman rank correlations across all 2,011 video clips.

Personality Trait Metrics. Figure 3a shows positive correlations between Overall Performance and Openness (ρ = 0.70), Conscientiousness (ρ = 0.74), Extraversion (ρ = 0.65), with Agreeableness strongest (ρ = 0.80); Neuroticism is negative (ρ = -0.39). This pattern aligns with theory: interpersonal warmth (Agreeableness) is most salient, while organization and intellectual engagement (Conscientiousness, Openness) also contribute.

Performance Metrics. Figure 3b shows moderate-strong positive correlations across all metrics. Confidence has the strongest association (ρ = 0.83), followed by Answer Score (ρ = 0.82) and Interview Score (ρ = 0.76). Facial Expressions and Speaking Skills are also substantial (ρ = 0.69, ρ = 0.71). Overall, stronger perceived personality aligns with higher confidence, more expressive nonverbal behavior, and better-structured, well-delivered responses.

The complete 12 × 12 Spearman correlation matrix with all pairwise relationships is provided in Appendix A.5 for comprehensive reference.

We analyzed the statistical properties of the 12 continuous target labels derived from the MNL model. The distributions are all normalized with near-zero means. A complete, detailed statistical analysis of all 12 metrics, including their implications, is provided in Appendix A.6. Most metrics exhibit significant leptokurtosis (heavy tails) and asymmetric skew. For instance, Speaking Skills (ρ ≈ -0.86) and Overall Performance (ρ ≈ -0.75) are negatively skewed, while Answer Score (ρ ≈ 0.35) is positively skewed. This prevalence of outliers and non-normality strongly motivates our methodological choices: (1) the use of a robust Huber loss for training to mitigate the influence of extreme outliers, and (2) the prioritization of rank-based correlation metrics (e.g., Spearman’s ρ) for evaluation, which are insensitive to this skew. Outlier Treatment via Soft Winsorization. To address extreme outliers while preserving data structure, we apply mild soft winsorization. Values within ±1.5σ pass through unchanged, while values beyond this threshold are smoothly compressed toward ±3σ using tanh-based soft clipping: clip(x) = sign(x) • (θ + s • tanh((|x| -θ)/s)) for |x| > θ, where θ = 1.5 and s = 1.5. This smooth transition prevents extreme values from dominating gradient updates while maintaining differentiability and rank ordering, improving convergence without discarding informative variance.

We address the problem of predicting multiple continuous attributes from multimodal behavioral data. Given a video clip containing visual frames V ∈ R T ×H×W ×3 , audio waveform A ∈ R L , and transcript text T, our goal is to predict a vector of target attributes y ∈ R K representing personality traits and performance scores. Formally, we learn a function f : (V, A, T) → y that captures the complex relationships between multimodal behavioral cues and target attributes.

Traditional approaches assume all representations reside in Euclidean space, employing linear transformations and standard neural operations. However, behavioral data exhibits diverse geometric properties: personality traits form hierarchical taxonomies (Big Five domains comprising specific facets), behavioral cues show directional relationships (facial expressions oriented in specific directions), and performance metrics often vary continuously. To capture this rich structure, we propose explicitly modeling representations across multiple geometric manifolds, each encoding different relational properties of the data.

The CRMF framework consists of six core components:

(1) modality-specific encoders that extract representations from each input channel, (2) a pre-fusion module that performs early cross-modal integration, (3) manifold projection layers that map features to three geometric spaces, (4) geometry-specific expert networks that process each manifold representation, (5) an adaptive routing mechanism that learns optimal geometric combination strategies, and (6) a geometric fusion module that integrates multi-geometry representations for final prediction. Figure 4 illustrates the complete architecture.

The key insight behind CRMF is that different aspects of behavioral assessment benefit from different geometric inductive biases. Hyperbolic geometry naturally encodes hierarchical trait structures, spherical geometry captures directional behavioral patterns, and Euclidean geometry models continuous performance variations. By processing features through all three geometries and learning to combine them adaptively, CRMF can capture the full complexity of behavioral data. A detailed description of the CRMF framework’s formulation and architecture is provided in Appendix D.

We employ pretrained encoders for each modality:

DeBERTa-v3-base [36] for text, Wav2Vec2 [37]/HuBERT [38] for audio, and Video-MAE [39]/TimeSformer [40] for video. We fine-tune the last few layers of each encoder while keeping earlier layers frozen for parameter efficiency. For video, we apply a sophisticated temporal modeling pipeline consisting of BiLSTM, multi-head attention, and 1D convolution to capture rich temporal dynamics before pre-fusion. All modality encoders output representations with unified dimension d model = 768. Full details are provided in the Appendix D.1.

The pre-fusion module performs early integration of multimodal features through cross-modal attention. We concatenate encoded features from all modalities and add learnable modality embeddings:

where E mod ∈ R 3×d contains unique embeddings for text, audio, and video. A multi-layer transformer encoder processes the concatenated sequence, enabling rich crossmodal interactions. We employ learned attention pooling to obtain a fixed-dimensional clip-level representation z pre ∈ R d .

We project the fused representation z pre onto three geometric manifolds using learned linear projections followed by geometry-specific mappings: Hyperbolic Space: We use the Poincaré ball model B d c with curvature c = 1.0. Points are mapped via exponential map:

Euclidean Space: Standard linear projection:

Each manifold representation is processed by a specialized expert network designed to respect the underlying geometry. The hyperbolic expert uses Möbius transformations in gyrovector space, the spherical expert operates via tangent space mappings with exponential/logarithmic maps, and the Euclidean expert uses standard feed-forward layers. All experts have multiple layers and residual connections. Detailed formulations are available in the Appendix D.3.

To further refine expert outputs, we apply intra-manifold attention that respects geometric structure. For each geometry, we compute attention in its respective tangent space, which is Euclidean and enables standard multi-head attention operations. The attended representations are then mapped back to their respective manifolds.

The router learns to weight expert outputs based on input characteristics. Given z pre , a lightweight MLP predicts routing weights: where r ∈ ∆ K-1 contains weights for the K = 3 experts. To encourage diverse geometry utilization, we apply entropy regularization: L entropy = -λ ent K i=1 r i log r i . A negative value encourages high entropy, promoting complementary geometric views.

The fusion module combines expert outputs from different manifolds by first mapping all to a shared tangent space. For hyperbolic and spherical outputs, we use logarithmic maps; Euclidean output requires no conversion. The fusion operates via routing-weighted average:

followed by a refinement network producing z ref ined . This strategy is equivalent to first-order Fréchet mean approximation on the product manifold.

The prediction head maps the fused representation to target attributes using a shared MLP backbone followed by lightweight task-specific adaptation layers for each of the K = 12 targets. This parameter-efficient design balances expressiveness and efficiency.

Our training objective combines multiple loss components through adaptive balancing:

where components include Huber regression loss (δ = 1.0), correlation boosting loss, covariance alignment loss, and auxiliary routing regularization losses. The weights β i are learned adaptively using inverse variance weighting combined with learned parameters. Full details are in the Appendix D.8.

We train CRMF using AdamW [41]

We compare against three recent large multimodal models: MiniCPM-o 2.6 (8B) [1], VideoLLaMA2.1-AV (7B) [2], and Qwen2.5-Omni (7B) [3], all fine-tuned on our task. We evaluate using Spearman’s ρ, Kendall’s τ -b, Concordance Index (C-Index), Pearson’s r, and MSE. Metrics are computed per-target and macro-averaged for overall performance.

- Results Comparing encoder choices, VideoMAE generally outperforms TimeSformer, suggesting that masked autoencoding provides better video representations for this task. For audio, Wav2Vec2 and HuBERT show comparable performance, with Wav2Vec2 having a slight edge on correlation metrics.

Per-trait personality assessment results (Table 8 in Appendix) show CRMF demonstrates strong performance across all Big Five dimensions. Openness shows the strongest CRMF performance (ρ = 0.6384), representing a 13.4% improvement over the best baseline. Conscientiousness, Extraversion, and Agreeableness exhibit moderate but consistent improvements (8-13% gains). Neuroticism presents the most challenging prediction task, though CRMF still improves upon baselines by 24.5%.

Per-dimension performance assessment results ( and Confidence Score achieve moderate but consistent improvements (10-16% gains). Overall Performance benefits most from CRMF (ρ = 0.6521), with 9.1% improvement. Using only a single geometric space consistently underperforms: Hyperbolic-only achieves ρ = 0.5080 (10.6% drop), Spherical-only ρ = 0.5338 (6.1% drop), and Euclidean-only ρ = 0.5284 (7.0% drop). No single geometry matches the full model, confirming that different geometric spaces capture complementary information.

Removing the router and using uniform weights (ρ = 0.5209) causes substantial degradation (8.3% drop), confirming that adaptive weighting based on input characteristics is crucial.

Single modality analysis reveals video provides the strongest unimodal signal (ρ = 0.4516), followed by text (ρ = 0.4247) and audio (ρ = 0.3792). Crucially, even the best unimodal result is substantially lower than any multimodal configuration. The leap from video-only to full CRMF represents a 25.8% improvement, underscoring that behavioral traits are expressed through complex interplay of cues across modalities.

Additional ablation results for two-geometry combinations, pre-fusion variants, prediction head architectures, and loss functions are provided in the Appendix (Table 10).

We introduced RECRUITVIEW, a multimodal corpus for personality and interview analysis with continuous, psychometrically grounded labels derived from pairwise judgments. Building on this resource, we proposed CRMF, a geometry-aware regression framework that fuses audio, video, and text using manifold-specific attention and adaptive routing. On RECRUITVIEW, CRMF surpasses strong multimodal baselines, raising macro Spearman correlation to 0.568 and concordance index to 0.718, while using fewer trainable parameters. Ablations validate the benefits of multi-geometry fusion and routing, and show clear gaps between multimodal and unimodal variants. Limitations include moderate dataset scale, short clips, potential residual annotator bias and label noise despite calibration, and limited demographic diversity, which may constrain external validity. Future work will broaden populations and conditions, extend to longer multi-turn interactions, and integrate stronger self-supervised priors, target-wise manifold selection, and causal analyses, alongside real-time inference and human-in-the-loop calibration.

The full list of the 76 unique interview questions used as prompts in the data collection is provided in Table 3. These questions were curated from professional open-source resources, networking platforms, and consultations to elicit responses rich in both professional content and personality indicators.

To ensure standardized data acquisition and annotation, we developed two custom web-based platforms. The first, QAVideoShare 4 , is an online interview platform designed to collect video responses. Participants were presented with questions and recorded unscripted answers directly through the browser interface, ensuring uniform question presentation and automated video storage. The participant’s workflow, from authentication to recording, is shown in Figure 5.

The second platform, QA-Labeler5 , was developed for data labeling and evaluation. This tool allowed clinical psychologists (annotators) to view recorded videos and provide comparative assessments across various behavioral and performance criteria. The comparative judgment interface, featuring a side-by-side player and scoring form, is detailed in Figure 6. Both platforms support browser-based, multi-user operation, enabling a scalable and consistent data processing pipeline.

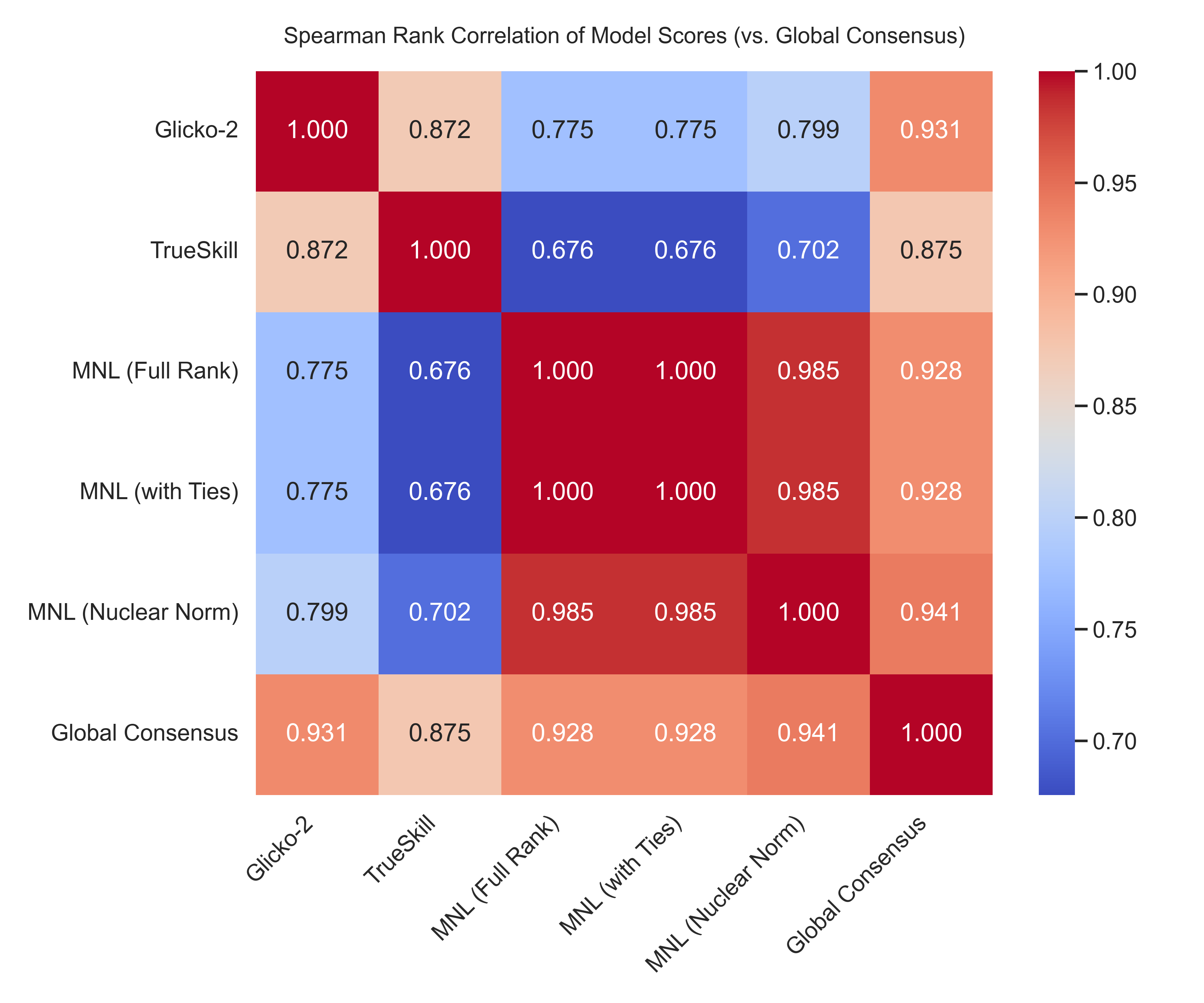

To ensure that the conversion of pairwise judgments into continuous rankings was both consistent and interpretable, we evaluated five independent label-conversion frameworks: Glicko-2, TrueSkill, Full-Rank MNL, MNLwith-Ties, and the Nuclear-Norm-Regularized MNL. Each method produced a scalar ranking score representing the latent position of each video across all pairwise comparisons. All models were trained on identical data.

We adopt a leave-one-out consensus evaluation. When evaluating a given model, its output is compared against a ground-truth defined as the mean of the standardized (Zscored) scores from all other models. This avoids selfevaluation, ensures symmetric treatment of all frameworks, and controls for scale or range mismatches. For models such as Nuclear-Norm MNL which inherently output normalized scores, further standardization was not applied.

Evaluation was performed using Spearman’s ρ, Kendall’s τ , RMSE, MAE, and Precision/Recall@10%, computed on continuous ranking outputs. These metrics were chosen for their compatibility with ordinal data, as our objective is to evaluate relative ordering fidelity rather than categorical correctness. Figure 7 shows the Spearman rank-correlation structure across models. Here, higher correlation is desirable because label-conversion methods are not supposed to invent disagreement; divergence between methods would indicate instability or method-specific distortion rather than genuine latent behavioral differences. Figure 8 further reinforces this observation, showing all five models plotted against the consensus reference for direct visual comparison.

Although all frameworks produced broadly compatible rankings, Full-Rank MNL achieved slightly higher peak correlations on isolated traits, while the Nuclear-Norm MNL exhibited greater overall stability with low variance across random drop-model trials (ρ = 0.905 ± 0.04). The low-rank constraint enforces smoother coupling across correlated personality traits, yielding more stable global rankings; this behavior is further reflected in the robustness summary (Table 4).

A secondary verification was conducted through a ratiobased test: a manually selected subset of pairwise comparisons was converted into empirical win-loss ratios, which serve as a local ordinal reference. The Nuclear-Norm MNL produced the closest match, accurately preserving both relative order and proportional differences. A small leaderboard test confirmed that local chains (A > B > C) remained globally consistent (A > C) and aligned with human expectations. In qualitative inspection, videos ranked higher by this model displayed clearer articulation, stronger confidence, and more natural expressiveness. Accordingly, we adopt the Nuclear-Norm formulation as the final label-conversion framework for RECRUITVIEW. Its low-rank structure offered smoother scaling across correlated targets, and its predictions were the most consistent with manual verification.

Table 5 presents comprehensive summary statistics for the 2,011 video segments in RECRUITVIEW. The clips have a mean duration of 29.66 seconds (σ = 16.40), with a minimum of 0.60 seconds and a maximum of 92.34 seconds. This temporal range ensures models are exposed to both brief “thin-slice” judgments and longer-form analyses. The transcripts are similarly diverse, with a mean word count of 81.90 (σ = 51.15) and a maximum of 266 words, providing

Avg These structured dependencies highlight the interconnected nature of personality perception and observable interview behaviors, providing insights into which combinations of traits and performance indicators are most strongly linked in evaluative contexts. (50% row in Table 7), and the modal mass of each histogram is concentrated around the origin (Figure 10), indicating a near-symmetric core for most variables. This implies that N is intrinsically less variable across our population relative to other psychological or performance attributes. Conversely, Interview-adjacent outcomes (Int., Ans., Spk., Conf., Fac., Perf.) show broadly comparable dispersion (≈ 1.1-1.28), desirable for multi-task optimization with shared heads. The extrema reveal long tails for several metrics (e.g., Ans.: min = -10.20; O: max = 9.34), which are far beyond ±3σ and thus consti-tute influential observations for any squared-loss estimator. Asymmetry (skewness). Skewness in Table 7 uncovers systematic asymmetries:

• Negative skew for C, Spk, Conf, and Perf (-0.57, -0.86, -0.64, -0.75) indicates heavier left tails and a rightshifted bulk. Practically, a larger fraction of samples achieve above-average performance on speaking, confidence, and overall performance, with relatively fewer but more extreme low outliers. • Positive skew for A, Pers., Int., and Fac. (0.40-0.66) suggests the opposite: mass slightly left of zero with occasional high outliers. Openness and Extraversion show mild asymmetry (0.03 and -0.22), while Neuroticism is modestly negative (-0.25), again consistent with its compressed variance. These asymmetries imply that symmetric error models may under-or over-penalize different tails across tasks; model selection should therefore consider robust losses and rankbased metrics. Tail heaviness (kurtosis). All targets except Neuroticism show pronounced leptokurtosis (excess kurtosis ≈ 8.8-13.4), confirming heavy tails and a high concentration near the center (Table 7). Neuroticism (1.14) is notably closer to mesokurtic behavior relative to the other metrics. Combined with the extreme minima/maxima, this indicates that a small subset of clips carry disproportionately informative deviations-a regime where (i) Huber/quantile losses and (ii) clipping or winsorization, materially improve stability and interpretability. Quartiles and central mass. Interquartile ranges are tightly packed around zero (25%-75% roughly ±0.55-0.62 for most metrics), reinforcing that the majority of ratings occupy a narrow band. The practical upshot is twofold: (a) small absolute errors around the origin correspond to meaningful rank changes, and (b) evaluation should prioritize monotonicity (Spearman ρ, Kendall τ , or concordance index) in addition to pointwise deviations.

We use stratified random sampling to create training (70%, 1404 samples), validation (15%, 290 samples), and test (15%, 317 samples) splits. Stratification is performed on the anonymized user number (i.e., ID) to prevent identity leakage across data splits. The same splits are used for all experiments to enable fair comparison.

Each entry in the RECRUITVIEW metadata file follows the structure shown below. Note that personally identifiable information (user name) has been anonymized.

“id”: “0001”, 3

“video_id”: “vid_0001”, 4

“video_filename”: “vid_0001.mp4”, 5

“duration”: “long”, 6

“question_id”: “1”, 7

“question”: “Introduce yourself”, 8

“video_quality”: “High”, 9

“user_no”: “147”, 10 “Openness (O)”: -0.653, 11 “Conscientiousness (C)”: -0.049, 12 “Extraversion (E)”: -0.691, 13 “Agreeableness (A)”: -0.293, 14 “Neuroticism (N)”: 0.190, 15

“overall_personality”: -0.029, 16

“interview_score”: -0.923, 17

“answer_score”: -0.803, 18

“speaking_skills”: -0.769, 19

“confidence_score”: -0.362, 20

“facial_expression”: -0.817, 21

“overall_performance”: -0.456, 22

“transcript”: “[00:01 -00:11] Hello everyone, this is …”

The twelve continuous scores are normalized and represent relative performance across the dataset, derived from the nuclear-norm regularized MNL model described in Section 3.3.

All data collection procedures for the RECRUITVIEW dataset were conducted under institutional ethical approval and followed human research standards consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were fully briefed about the study’s purpose and provided written informed consent prior to participation. The consent form explicitly covered the recording of interview videos, data usage for academic research, and the voluntary nature of participation. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw their data at any point before public release of the dataset used in this study, without consequence. No personally identifiable information (PII) was stored alongside the recordings. All metadata were anonymized, and the participant entries are linked only to an anonymized user number.

Participants were recruited through voluntary university outreach programs and online calls for participation. The pool consisted primarily of adult volunteers, with no inclusion of vulnerable populations.

Annotations were performed by clinical psychologists familiar with behavioral and personality assessment protocols. A pairwise comparison framework was adopted instead of absolute rating to reduce inter-rater calibration bias and to ensure consistency across annotators. Comparative judgments were aggregated using a nuclear-norm regularized multinomial logit model to derive continuous, psychometrically consistent target scores. Annotators were compensated fairly for their professional effort. All annotator identities remain confidential.

The dataset’s participant pool exhibits diversity in gender, accent, and educational background, but full demographic uniformity is not available. As such, models trained on this dataset may not generalize equally across other population subgroups. We explicitly acknowledge this limitation and encourage future fairness audits. The RECRUITVIEW dataset and the associated CRMF model are intended solely for research on multimodal behavioral and personality assessment. They are not validated for real-world deployment, hiring processes, or psychological diagnostics. Any attempt to use this work for employment screening, psychological profiling, or commercial analytics constitutes misuse. Although care was taken to minimize annotation bias and maintain fairness, all data-driven systems may still inherit spurious correlations; future work will include comprehensive fairness and subgroup analyses.

We emphasize transparency regarding dataset scope and limitations, including moderate dataset size and short interview durations. The dataset and code are released for non-commercial academic research to enable independent verification, benchmarking, and fairness assessment by the broader community.

Access to the RECRUITVIEW dataset is managed through a secure request portal. Applicants must submit an access request and sign a data usage agreement confirming (1) exclusive non-commercial academic use, (2) adherence to participant anonymity, and (3) compliance with the ethical guidelines outlined in this paper. The agreement prohibits using the dataset or models for employment decisions, identity profiling, or any commercial product development. Each access request is manually reviewed, and credentials are issued only upon approval and formal consent acknowledgment. Access logs are maintained, and the authors reserve the right to revoke access in cases of misuse.

The dataset is released under the license CC BY-NC 4.0 restricting commercial use.

All data management and access mechanisms comply with institutional data-protection policies and relevant data privacy regulations (e.g., GDPR).

While the RECRUITVIEW dataset contributes valuable insights into multimodal human behavior, we acknowledge potential societal risks. Automated evaluation models trained on human behavioral data could be misinterpreted as objective assessment tools. To mitigate such risks, we provide explicit usage guidelines, controlled data access, and emphasize the need for human oversight in any interpretive use. Continuous monitoring of dataset access and transparency in documentation are maintained to minimize misuse and promote ethical research practice. We employ DeBERTa-v3-base [36] as our text encoder, which has shown strong performance on natural language understanding tasks. Given tokenized input T tok ∈ Z Nt with attention mask M t ∈ {0, 1} Nt , the encoder produces contextualized token representations:

where d = 768 is the hidden dimension. We fine-tune the last few layers of DeBERTa while keeping earlier layers frozen to balance expressiveness and parameter efficiency.

A learned linear projection maps the output to our unified representation space of dimension d model = 768.

For audio processing, we explore two self-supervised speech representations: Wav2Vec2 [37] and HuBERT [38]. Given raw audio waveform A ∈ R L sampled at 16kHz, the encoder produces frame-level representations:

Both Wav2Vec2 and HuBERT learn rich acoustic representations through contrastive predictive coding and masked prediction objectives, respectively. We fine-tune the last few transformer layers while keeping the convolutional feature extractor fixed. The output is projected to d model dimensions.

For visual processing, we investigate two video understanding architectures: VideoMAE [39] and TimeSformer [40].

Given input video with variable frame count, we first apply 3D convolutional interpolation to adapt the temporal dimension to the encoder’s expected frame count (16 for VideoMAE, 8 for TimeSformer). For an input V ∈ R T ×3×224×224 , this yields V ′ ∈ R T ′ ×3×224×224 .

The encoder extracts patch-level features, which we re-shape into temporal-spatial structure. We apply spatial average pooling to obtain temporal features F v ∈ R T ′ ×d .

To capture rich temporal dynamics, we apply a multistage temporal modeling pipeline:

F attn = MultiHeadAttn(F lstm F lstm , F lstm ) ∈ R T ′ ×d (11)

H v = Proj(F lstm + F attn + F conv ) ∈ R T ′ ×d model (13) where BiLSTM captures sequential dependencies, multihead attention models long-range interactions, and depthwise convolution captures local temporal patterns. The multi-scale fusion combines all three views, and a final projection maps to d model dimensions. This produces a temporal sequence H v ∈ R 8×768 preserving fine-grained temporal information for subsequent pre-fusion processing. VideoMAE employs masked autoencoding with high masking ratios for efficient self-supervised learning, while TimeSformer uses divided space-time attention. We finetune the last few transformer blocks of each encoder while keeping earlier layers frozen for parameter efficiency.

The pre-fusion module performs early integration of multimodal features through cross-modal attention. We concate-nate encoded features from all modalities and add learnable modality embeddings to distinguish information sources:

where E mod ∈ R 3×d contains unique embeddings for text, audio, and video. A multi-layer transformer encoder with L pre layers processes the concatenated sequence:

enabling rich cross-modal interactions through selfattention.

To obtain a fixed-dimensional clip-level representation, we employ learned attention pooling rather than simple mean pooling:

where w ∈ R d is a learnable attention vector and h i denotes the i-th token in H f used . This pooling mechanism learns to emphasize tokens most relevant for behavioral assessment, producing z pre ∈ R d .

The hyperbolic expert performs operations in the gyrovector space framework [42], using Möbius transformations that preserve hyperbolic distances. For a L exp -layer network:

where ⊗ c denotes Möbius matrix-vector multiplication, ⊕ c is Möbius addition, and σ h is a Möbius pointwise nonlinearity. Specifically, Möbius addition is defined as:

The Möbius pointwise nonlinearity applies activation functions in tangent space: σ h (x) = exp c x (σ(log c x (x))), where log c

x and exp c x are the logarithmic and exponential maps at x.

After processing, residual connections using Möbius addition:

h . All operations preserve the hyperbolic geometry, ensuring outputs remain in the Poincaré ball.

Operations on the sphere are performed in tangent space via exponential and logarithmic maps. Given base point p (we use the north pole), the logarithmic map projects x s to the tangent space T p S d-1 : log p (x s ) = arccos(⟨p, x s ⟩)

1 -⟨p, x s ⟩ 2 (x s -⟨p, x s ⟩p)

In tangent space, standard linear transformations and activations apply:

where v (ℓ) ∈ T p S d-1 . The final tangent vector is mapped back to the sphere via exponential map:

Residual connections in tangent space combine the input and output: v out = v (L) + v (0) , followed by exponential map back to S d-1 .

The Euclidean expert uses standard feed-forward layers with residual connections:

x

To further refine expert outputs, we apply intra-manifold attention that respects geometric structure. For each geometry, we compute attention in its respective tangent space.

Given hyperbolic representations x out h , we map to tangent space at the origin:

Multi-head self-attention is applied in tangent space (which is Euclidean):

where

The attended representation is mapped back:

Similar procedures apply for spherical geometry using log p and exp p . For Euclidean space, attention is applied directly without manifold conversions. All attention modules use multiple heads with temperature scaling τ to sharpen attention distributions.

presents aggregate results averaged across all 12 target attributes. CRMF variants substantially outperform Model Spearman ρ Kendall τ -b C-index Pearson r

Parameter Efficiency: The performance gains are particularly remarkable given CRMF’s parameter efficiency. Our framework (VideoMAE + Wav2Vec2 configuration) contains 408M parameters total, with 172M trainable during fine-tuning. In contrast, baseline LMMs fine-tune substantially more parameters: MiniCPM-o (∼340M), VideoLLaMA2 (∼300M), Qwen2.5-Omni (∼320M). Despite training 40-50% fewer trainable parameters, CRMF achieves superior performance, demonstrating that taskspecific geometric inductive biases provide more effective learning signals than simply leveraging larger pretrained models.

presents key ablation results. Using only fusion (no CRMF framework), such as simple concatenation (ρ = 0.4441) or weighted averaging (ρ = 0.4664), causes severe degradation (21.8% and 17.9% drops), demonstrating that naive fusion strategies fail to capture complex multimodal relationships.

. ρ Std. Dev. Trials a rich linguistic substrate for multimodal analysis. The median (50th percentile) values for duration(27.27s) and word count (72.00) closely track their respective means, confirming the well-behaved nature of these distributions.

. ρ Std. Dev. Trials a rich linguistic substrate for multimodal analysis. The median (50th percentile) values for duration(27.27s

. ρ Std. Dev. Trials a rich linguistic substrate for multimodal analysis. The median (50th percentile) values for duration

presents the complete Spearman correlation matrix across all 12 target dimensions in RECRUITVIEW. This

https://huggingface.co/openai/whisper-large-v3

📸 Image Gallery