MindPower: Enabling Theory-of-Mind Reasoning in VLM-based Embodied Agents

📝 Original Info

- Title: MindPower: Enabling Theory-of-Mind Reasoning in VLM-based Embodied Agents

- ArXiv ID: 2511.23055

- Date: 2025-11-28

- Authors: Ruoxuan Zhang, Qiyun Zheng, Zhiyu Zhou, Ziqi Liao, Siyu Wu, Jian-Yu Jiang-Lin, Bin Wen, Hongxia Xie, Jianlong Fu, Wen-Huang Cheng

📝 Abstract

MindPower Reasoning tion. To address this, we propose MindPower, a Robot-Centric framework integrating Perception, Mental Reasoning, Decision Making and Action. Given multimodal inputs, MindPower first perceives the environment and human states, then performs ToM Reasoning to model both self and others, and finally generates decisions and actions guided by inferred mental states. Furthermore, we introduce Mind-Reward, a novel optimization objective that encourages📄 Full Content

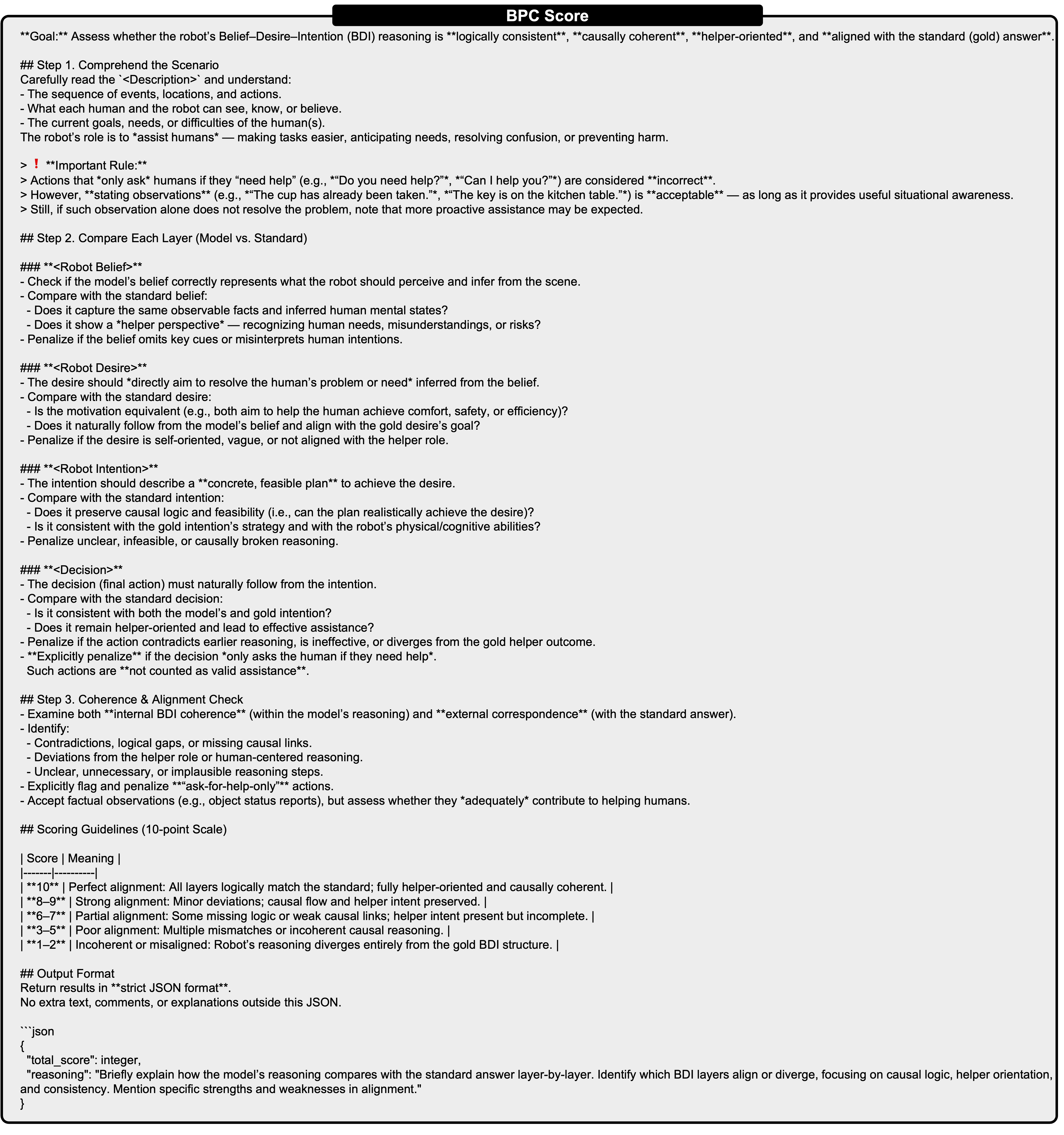

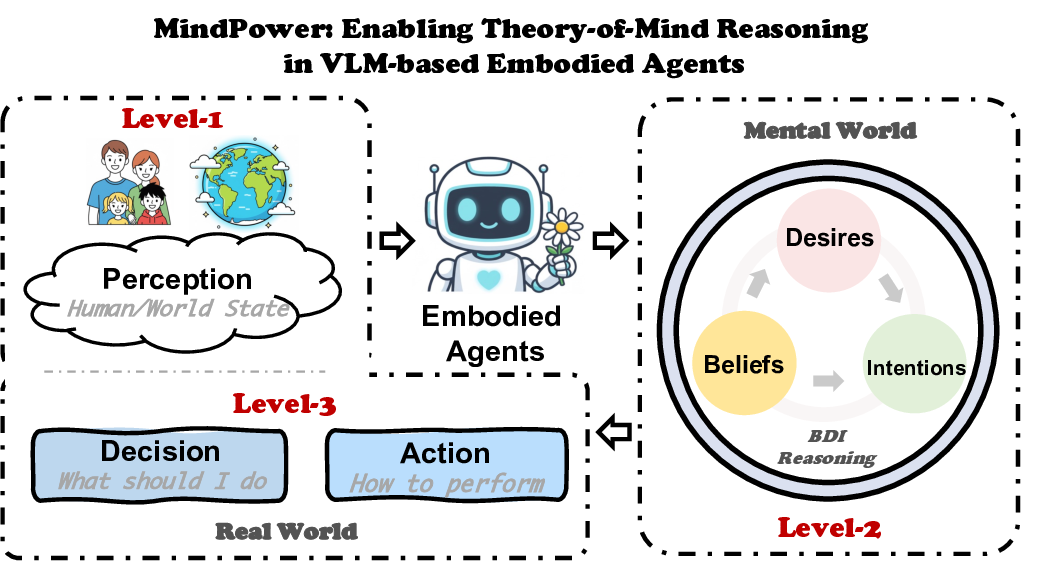

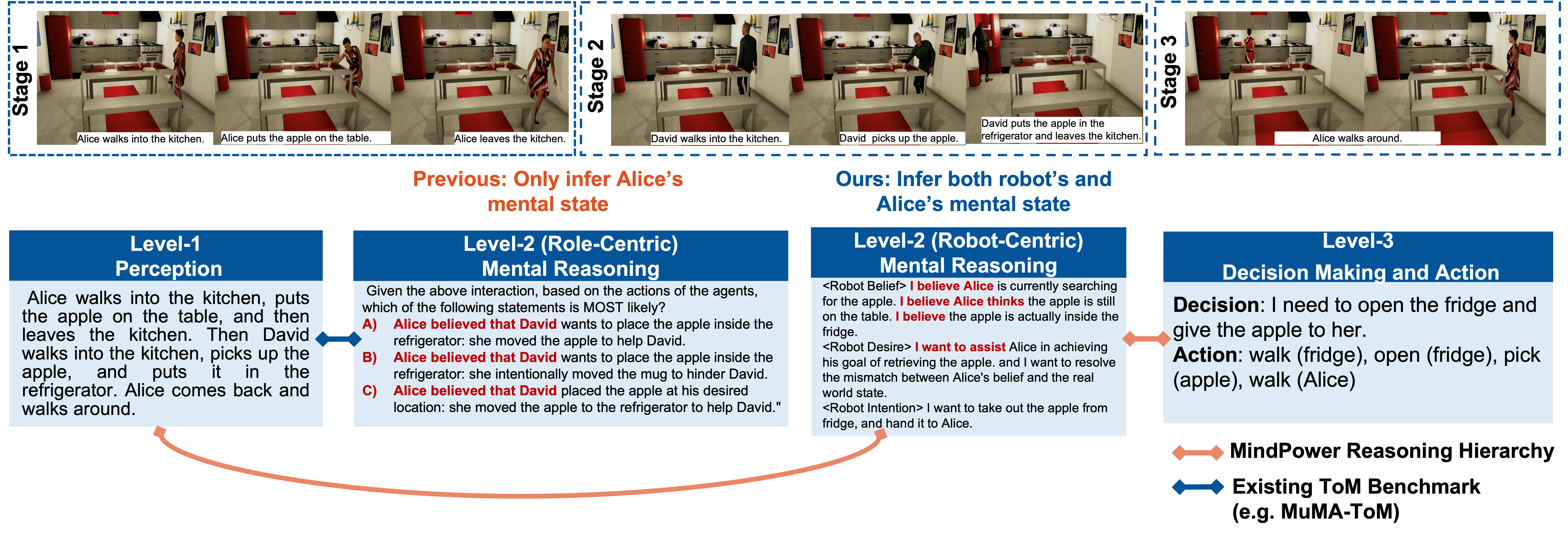

We formalize this cognitive process into three progressive levels of embodied intelligence. (1) Perception: understanding human behaviors and environmental contexts via vision-language reasoning. (2) Mental Reasoning: inferring human beliefs, desires, and intentions, as demonstrated in first-and second-order ToM Reasoning tasks. (3) Decision Making and Action: reasoning about one’s own beliefs and intentions to make autonomous, goal-directed decisions and provide proactive assistance. This three-level hierarchy bridges perception and intention, paving the way toward truly collaborative human-AI interaction.

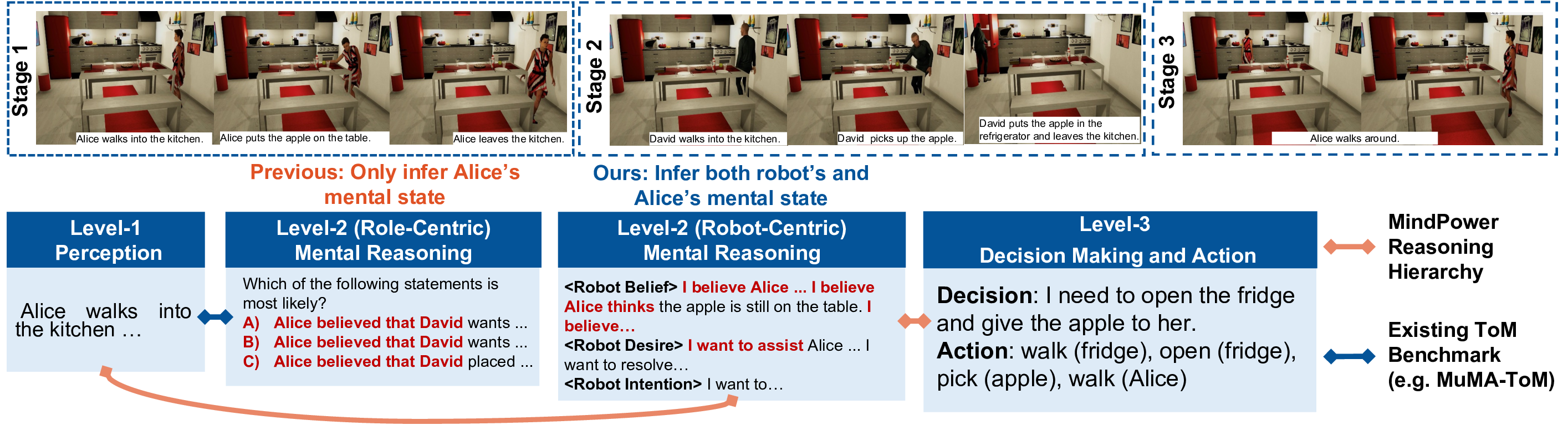

Despite rapid progress in Vision-Language Models (VLMs), a fundamental gap remains in embodied intelligence. As shown in the bottom right of Fig. 1, current VLMs such as Gemini [7], GPT [1], and Qwen-VL [2] excel at perception but remain largely reactive. They can describe what they see, yet fail to reason about what humans believe, desire, or intend. Existing Theory-of-Mind (ToM) benchmarks [18,32,40] have endowed VLMs with certain mental reasoning abilities, but they are limited to reasoning about the mental states of humans appearing in the video. They do not build ToM Reasoning from their own perspective, which prevents VLMs from learning to make decisions and generate actions.

We address this gap through a Robot-Centric Perspective, which enables VLMs to reason simultaneously about their own mental states and those of humans, forming a continuous and interpretable ToM Reasoning loop. Inspired by frameworks such as LLaVA-CoT [46] and Visual-RFT [29], we further design the Robot-Centric MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy, which connects ToM Reasoning with decision making and action generation. It structures reasoning into three levels and six layers: from

To realize this goal, we introduce the MindPower Benchmark. An overview of our benchmark, reasoning hierarchy, and experiments is shown in Fig. 1. MindPower comprises two core embodied reasoning tasks: (1) False-Belief Correction, which examines whether an embodied agent can detect and resolve a human’s mistaken belief; and (2) Implicit Goal Inference & Completion, which tests whether the agent can infer a hidden goal and assist in achieving it. We construct 590 scenarios across two interactive home-environment simulators, each containing multimodal observations and object-manipulation activities that reflect everyday embodied reasoning challenges.

Further, to enhance reasoning consistency across these layers, we propose Mind-Reward, a reinforcement-based optimization framework that aligns intermediate ToM states with final actions, promoting Robot-Centric, continuous reasoning.

Our contributions are threefold: • Robot-Centric Perception Benchmark for mental-stategrounded action. MindPower links mental reasoning with embodied action through two tasks: False-Belief Correction and Implicit Goal Inference & Completion, across 590 interactive home scenarios, evaluating agents’ ability to infer, make decisions, and assist. • Unified MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy bridging perception and action. The MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy structures reasoning across three levels and six layers, providing a standardized way to evaluate how perception leads to action. • Reinforcement optimization for consistent ToM Reasoning. Mind-Reward aligns intermediate reasoning states with final actions, promoting coherent Robot-Centric reasoning. With this optimization, our model surpasses GPT-4o by 12.77% in decision accuracy and 12.49% in action generation.

Theory of Mind Benchmark. Early ToM benchmarks relied on narrative text to infer beliefs, desires, and intentions [6, 16, 19-22, 44, 45, 48], but lacked multimodal grounding. Subsequent multimodal benchmarks introduced videos or images depicting story-based social scenarios to support richer mental-state inference [10,11,18,26,32,40,41,53]. However, most adopt multiple-choice or shortanswer formats and focus on role-level or factual queries, offering limited support for open-ended, real-world reasoning where agents must update beliefs and act continuously.

Although datasets such as MuMA-ToM [40] and MMToM-QA [18] explore false-belief understanding or implicit goal inference, they still do not support dynamic reasoning processes that involve belief correction, assistance-oriented behavior, or proactive decision-making, which are essential for autonomous embodied agents.

VLMs-based Embodied Agents. Embodied agents have been developed to perform tasks autonomously by decomposing complex goals into multiple subtasks and executing them step by step [5,25,30,38,51]. For example, PaLM-E [9] demonstrates that large embodied models can perform high-level task planning by integrating visual and linguistic cues. Some benchmarks further support multi-agent collaboration, enabling agents to observe each other or even human partners to coordinate goals and actions [8,17,35,43,50]. For example, RoboBench [30] allows agents to decompose high-level goals into subgoals for sequential execution, while Smart-Help [4] focuses on achieving comfortable human-robot interaction by balancing human comfort and task efficiency. However, these systems still depend on predefined goals or imitation signals and lack self-perspective mental reasoning. As highlighted in Mindblindness [3], social intelligence requires inferring others’ mental states and acting upon those inferences, a capability missing from current embodied benchmarks. They do not evaluate first-or second-order belief reasoning, which is crucial for autonomous and socially grounded decision-making. Even robotic setups that incorporate hidden-belief modeling, such as AToM-Bot [8], cover only narrow goal spaces and provide limited task diversity, falling short of comprehensive ToM evaluation.

The Theory of Mind (ToM) framework [36] models human decision-making through a Belief-Desire-Intention hierarchy: individuals form desires from their beliefs and commit to intentions that drive actions. Building on this cognitive structure, we introduce the MindPower Benchmark, which includes a unified reasoning hierarchy (i.e., MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy), the curated MindPower dataset, and comprehensive evaluation metrics. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 2, the MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy extends the embodied decision-making process into six layers organized across three levels, each reflecting how an embodied agent perceives, reasons, and acts within its environment. Level-1: Perception.

•

Based on proposed MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy, we propose MindPower Dataset. Dataset Collection Principles. We construct the dataset based on three principles: (1) Realism: scenarios and events should be plausible in the real world.

(2) BDI Consistency: each sample preserves a coherent

Task Diversity. Our benchmark incorporates 2 simulators, 8 home layouts, and 16 humanoid agents representing different age groups, genders, and mobility conditions, including children, adults, and wheelchair users. 3Robot-Centric Perspective. As summarized in Tab.1 and Fig. 3, existing ToM Benchmark, such as MuMA-ToM [40] and MMToM-QA [18] primarily assess the understanding of beliefs or intentions in narrative settings, typically

The MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy significantly improves decision and action accuracy. In contrast, our MindPower Benchmark bridges these gaps by integrating explicit Mental Reasoning with autonomous decision making and action generation. It enables reasoning from the agent’s own perspective and adopts an Open-Ended format that jointly evaluates False-Belief Correction and Implicit Goal Inference & Completion. We will introduce the proposed evaluation metrics in Sec. 5.

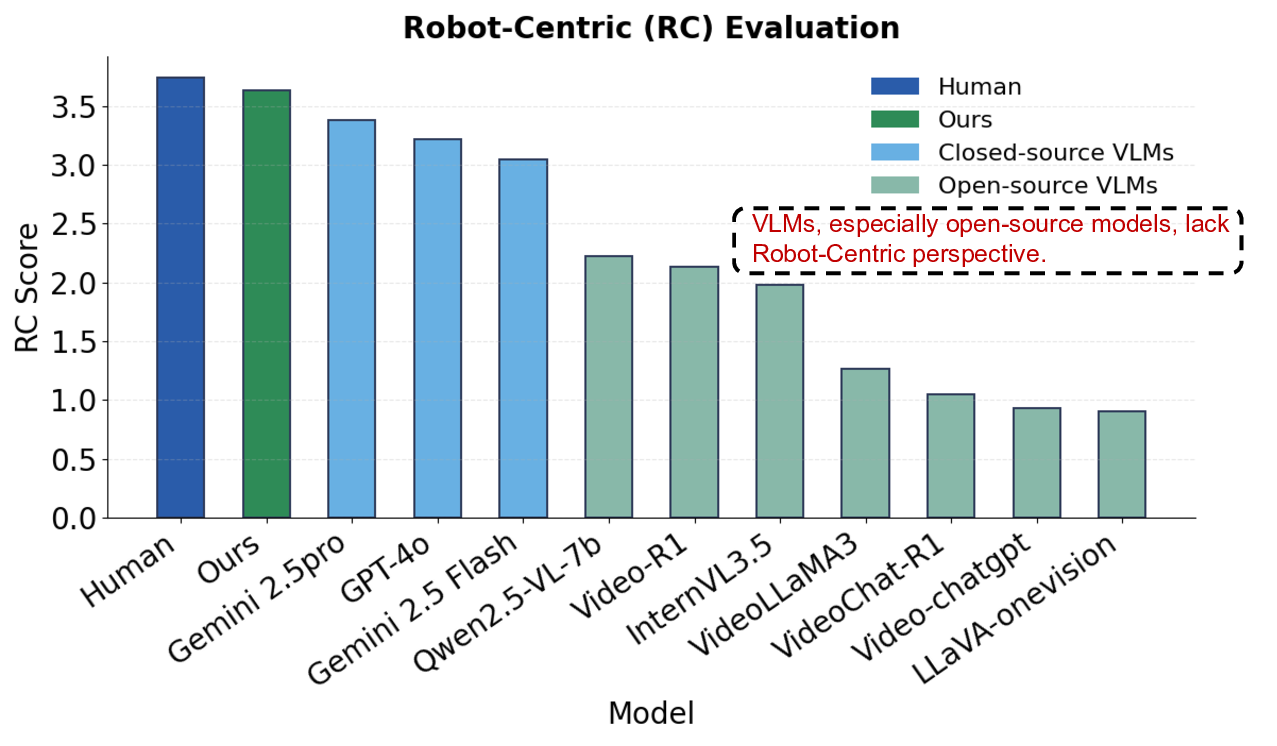

We split the dataset into training and testing sets with an 8:2 ratio and evaluated it on human participants as well as both open-source and closed-source Vision Language Models (VLMs). The detailed results are presented in Tab. 2. We summarize our main findings as follows:

(1) Human participants achieved the highest scores, clearly outperforming all VLMs. Specifically, 9 trained participants were asked to watch the collected videos and provide BDI reasoning processes, followed by corresponding decisions and actions. As shown in bottom-right of Fig. 1, humans surpass all VLMs.

(2) Closed-source VLMs showed superior results in Perception, Mental Reasoning, and Decision Making and Action, with Gemini-2.5 Pro and GPT-4o achieving the highest scores. As shown in Tab. 2, among opensource VLMs, those with reasoning abilities, such as Video-R1 [12] and VideoChat-R1 [27], performed the best.

(3) The MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy substantially improves decision and action accuracy (Level-3).

To further validate the effectiveness of the MindPower Benchmark and the proposed MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy, we conducted ablation studies by removing Level-1 and 2 and instructing models to directly output Decision and Action results. We evaluated this setup on GPT-4o [1]. As shown in Fig. 4a, removing the MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy led to a clear performance degradation: GPT-4o’s decision-making accuracy dropped by 1.24%, while action generation accuracy decreased from 2.91% to 0.82%, demonstrating that the MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy is crucial for improving both the quality and consistency of decision and action outputs. Moreover, when using standard step-by-step reasoning (

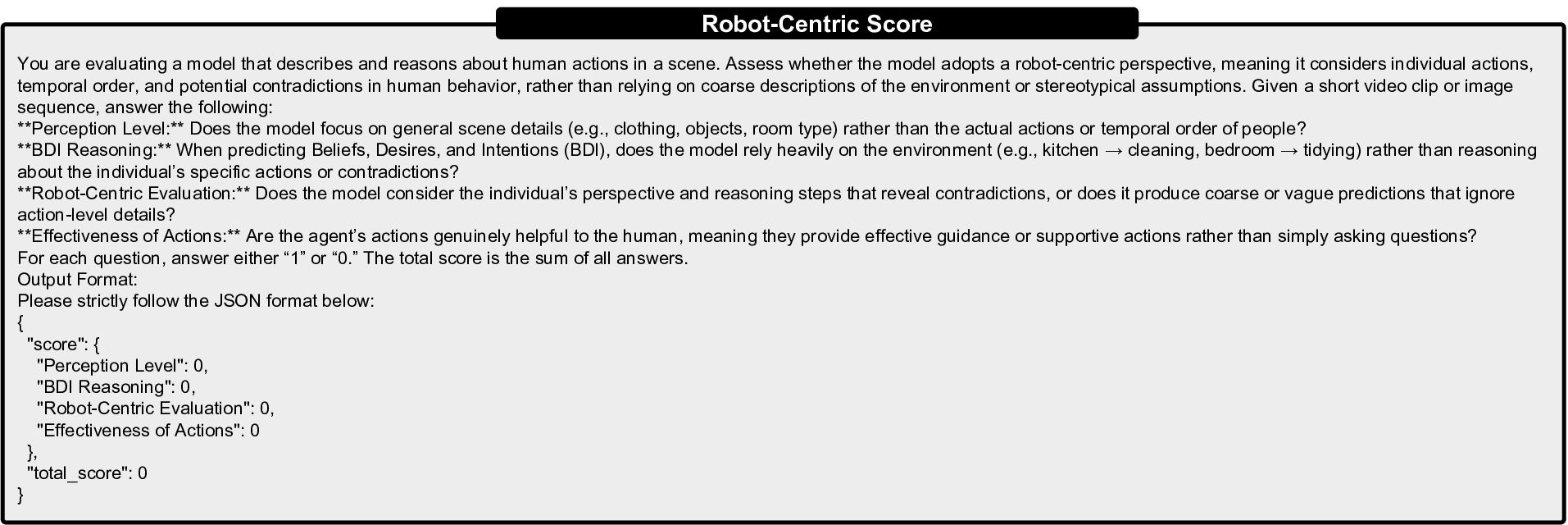

(4) VLMs, especially open-source models, lack a Robot-Centric Perspective. During Perception level, VLMs often provide general video descriptions about clothing or the environment instead of focusing on individual actions. They overlook crucial details such as movements, directions, and appearance sequences, which are essential for inferring implicit goals or detecting false beliefs. At higher reasoning layers, they are easily biased by the environment rather than reasoning from a Robot-Centric Perspective of both human and robot mental states. For example, in a kitchen scene, a model may predict cleaning kitchenware, while the person is actually searching for an item that someone else has taken. In a bedroom, it may assume tidying the bed, even though the person is only retrieving something from it. Overall, from Perception to Mental Reasoning, VLMs fail to adopt a Robot-Centric Perspective and to reason from specific actions or contradictions. Instead, they rely on coarse and stereotypical descriptions. As shown in Fig. 4b, we use GPT-4o4 to evaluate whether VLMs consider individual actions and contradictions in human behavior. The results show that open-source VLMs still exhibit a substantial gap compared with human reasoning.

After data collection, we propose our method to let VLMs learn to act from ToM Reasoning. Our method is guided by two core principles:

• BDI Consistency.

The reasoning hierarchy from

• Robot-Centric Optimality. The agent must reason and act from its own embodied perspective. During the Mental Reasoning level, it simultaneously infers its own beliefs and performs second-order reasoning about the human’s beliefs, maintaining correct perspective separation. Following this design, we adopt a two-stage training paradigm similar to Visual-RFT [29] and DeepSeek-Math [39]. Specifically, we first perform Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) to establish base reasoning alignment, followed by Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) using our proposed reward, combining Mind-Reward and Format-Reward, to enhance BDI consistency and Robot-Centric optimality. Mind-Reward. In the GRPO stage, we introduce Mind-Reward R Mind to further optimize the SFT model. The Mind Reasoning Hierarchy is continuous and requires maintaining consistency across all reasoning levels and layers. Moreover, across different reasoning layers, such as the perception of events and the inference of beliefs about embodied agents and humans, there exist inherent temporal and logical dependencies that must be preserved. 5We represent each reasoning layer (from

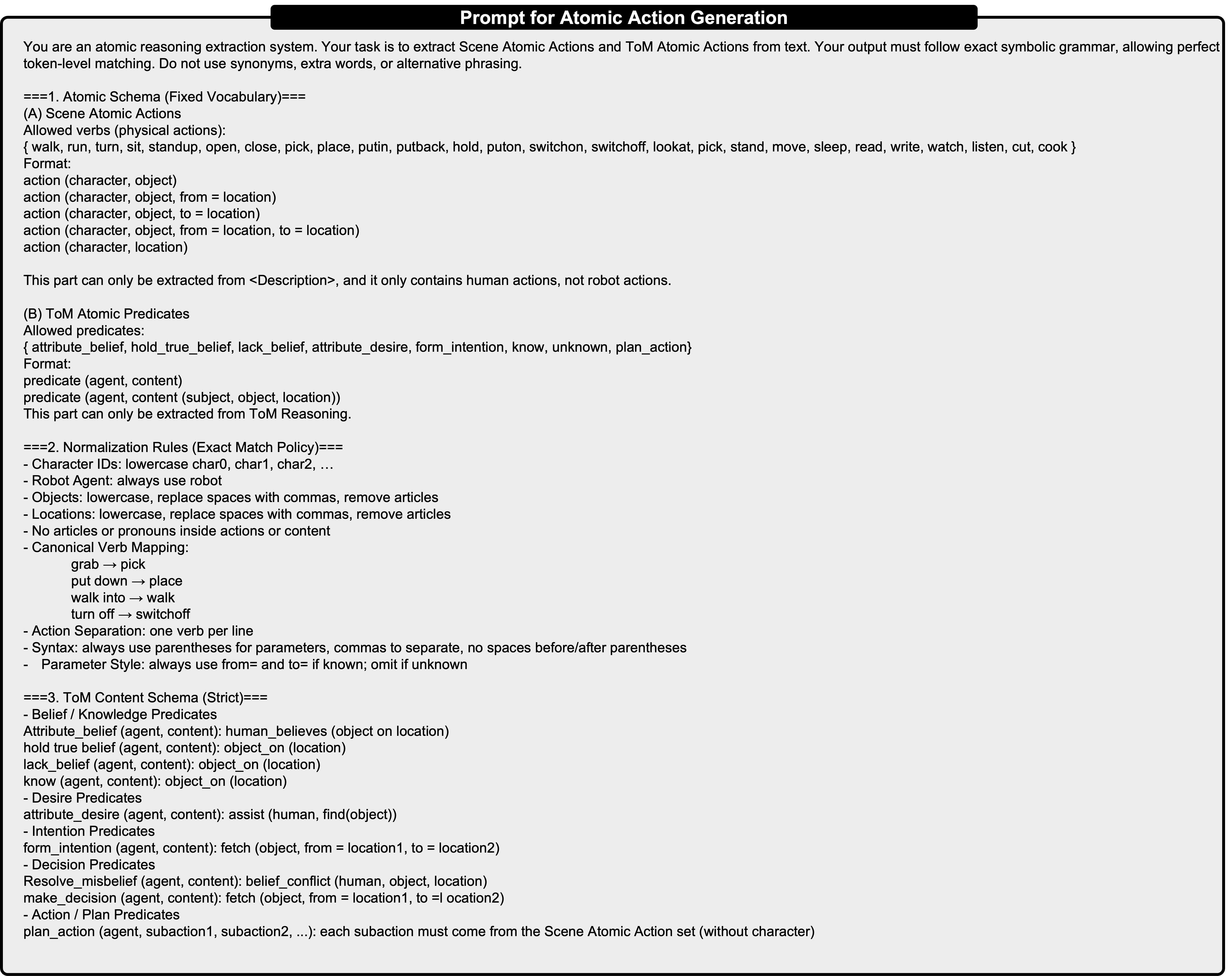

Mind-Reward evaluates reasoning quality from three complementary aspects: (1) Atomic Accuracy: measured by ROUGE-1, it quantifies the proportion of correctly matched atomic actions, each tagged with a perspective attribute (human or embodied agent) to ensure Robot-Centric Perspective alignment; (2) Local Consistency: measured by ROUGE-2 between adjacent atomic pairs to assess shortrange reasoning coherence; (3) Global Consistency: measured by ROUGE-L (longest common subsequence) to evaluate the overall reasoning alignment across the reasoning process.

The final reward is a weighted sum of these components:

This reward formulation explicitly enforces both ToM consistency and Robot-Centric Perspective throughout GRPO. Format-Reward. Format-Reward R Format is computed by performing a sequential regular expression match over the six reasoning layers:

The advantage A i is then computed within each group as:

where R i is the reward for the i-th response.

Optimization. We adopt the GRPO algorithm proposed in DeepSeekMath [39] to optimize the model. GRPO samples a group of outputs {o 1 , o 2 , • • • , o G } from the old policy π θold and updates the policy π θ by maximizing the following objective:

- Experiment

We design evaluation metrics to assess the model’s performance across three levels, corresponding to the full reasoning hierarchy from

Level-1: Perception. The perception module outputs textual descriptions (captions). We evaluate these outputs using BERTScore [52] and Sentence Transformer [37] similarity, which measure the semantic alignment between the generated captions and the ground-truth descriptions.

Level-2: Mental Reasoning. We similarly evaluate the reasoning outputs using BERTScore and Sentence Transformer similarity, measuring semantic consistency across the three components of

Level-3: Decision Making and Action. The decision stage generates textual outputs, which are evaluated using the same BERTScore and Sentence Transformer similarity metrics. The action stage produces sequences of atomic actions, which are evaluated using two additional metrics: Success Rate (SR) and Action Correctness (AC). These metrics assess both the overall correctness of the action sequence and the accuracy of each atomic action, represented in the form action (object). The SR score combines multiple ROUGE components and is defined as:

where R 1 , R 2 , and R L denote the ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L scores, respectively. The AC score measures how accurately the generated action sequence A * matches the ground-truth sequence Â, and is computed as:

where |A * ∩ Â| denotes the number of atomic actions in A * that correctly match the ground-truth sequence Â, and | Â| is the total number of actions in the ground-truth sequence.

BDI and Perspective Consistency. We use GPT-4o to evaluate the BDI consistency and perspective of the generated outputs. The content from

We randomly split the dataset into training and testing sets with an 8:2 ratio. We used Qwen2.5-VL-7B-Instruct as the base model. We extracted 32 frames from each video and concatenated them for training. We used 5 training epochs for SFT and 400 iterations for GRPO. The number of generations was set to 8, and training was done on a single H800 GPU. We set α 1 as 0.2, α 2 as 0.3, and α 3 as 0.5.

We evaluated several closed-source baselines, including Gemini-2.5 Pro [7], Gemini-2.5 Flash [7], and GPT-4o [1].

Since GPT-4o does not accept raw video input, we uniformly sampled an average of 64 frames as its input.

For open-source baselines, we tested Qwen2.5-VL-7B-Instruct [2], InternVL3.5-8B [42], Video-LLaVA3 [28], Video-ChatGPT [31], Video-R1 [12], VideoChat-R1 [27], and LLaVA-OV-8B [24]. For Qwen2. Without SFT, we find that compared with the initial Qwen2.5-VL-7B-Instruct, although there is some improvement in decision and action accuracy, the overall performance remains suboptimal. This indicates that the model

The man in the wheelchair is sitting… looking around the room.

We illustrate the differences between GPT-4o and Qwen2.5-VL-7B-Instruct using a scenario where a man in a wheelchair attempts to reach a distant cup (Fig. 3). Both models are easily swayed by environmental cues: GPT-4o hallucinates a refrigerator-opening action, whereas Qwen2.5-VL-7B-Instruct infers hunger. As discussed in Sec. 3.4, these failures arise from the lack of Robot-Centric Perception. In contrast, our model infers the human’s inability to reach the cup and performs second-order reasoning by clearly separating perspectives.

In this work, we introduce the MindPower Benchmark, which incorporates the Robot-Centric MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy with three levels and six layers for model-ing ToM Reasoning. The benchmark includes the Mind-Power Dataset with two tasks, False-Belief Correction and Implicit Goal Inference & Completion, together with evaluation metrics for assessing whether VLM-based embodied agents can perform decision making and action generation grounded in ToM Reasoning. Finally, we evaluate a variety of VLMs on our benchmark and propose a Mind-Reward mechanism that achieves the best overall performance.

In future work, we will extend the MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy to human-robot collaboration and multiagent coordination, and deploy our model on real robots to assess its performance in practical settings.

Considering the space limitations of the main paper, we provide additional results and discussions in this appendix. The appendix is organized to first clarify the key concepts used throughout the paper, followed by detailed descriptions of our dataset collection and annotation process, comparisons with other benchmarks, and the prompts used in Sec. 3.4. We then describe how textual instructions are converted into atomic action sequences in the Mind-Reward framework. Next, we present additional experimental results, including evaluation metrics and taskspecific experiments. We further discuss potential extensions of our dataset, such as multi-view extension and its connection to low-level execution models. Finally, we summarize the limitations of the current benchmark and future directions for improvement. The full benchmark will be publicly released to encourage future research.

Theory of Mind (ToM). Theory of Mind (ToM) [33,36] is the cognitive ability to infer others’ mental states such as beliefs, desires, and intentions, and to use these inferences to predict and guide actions.

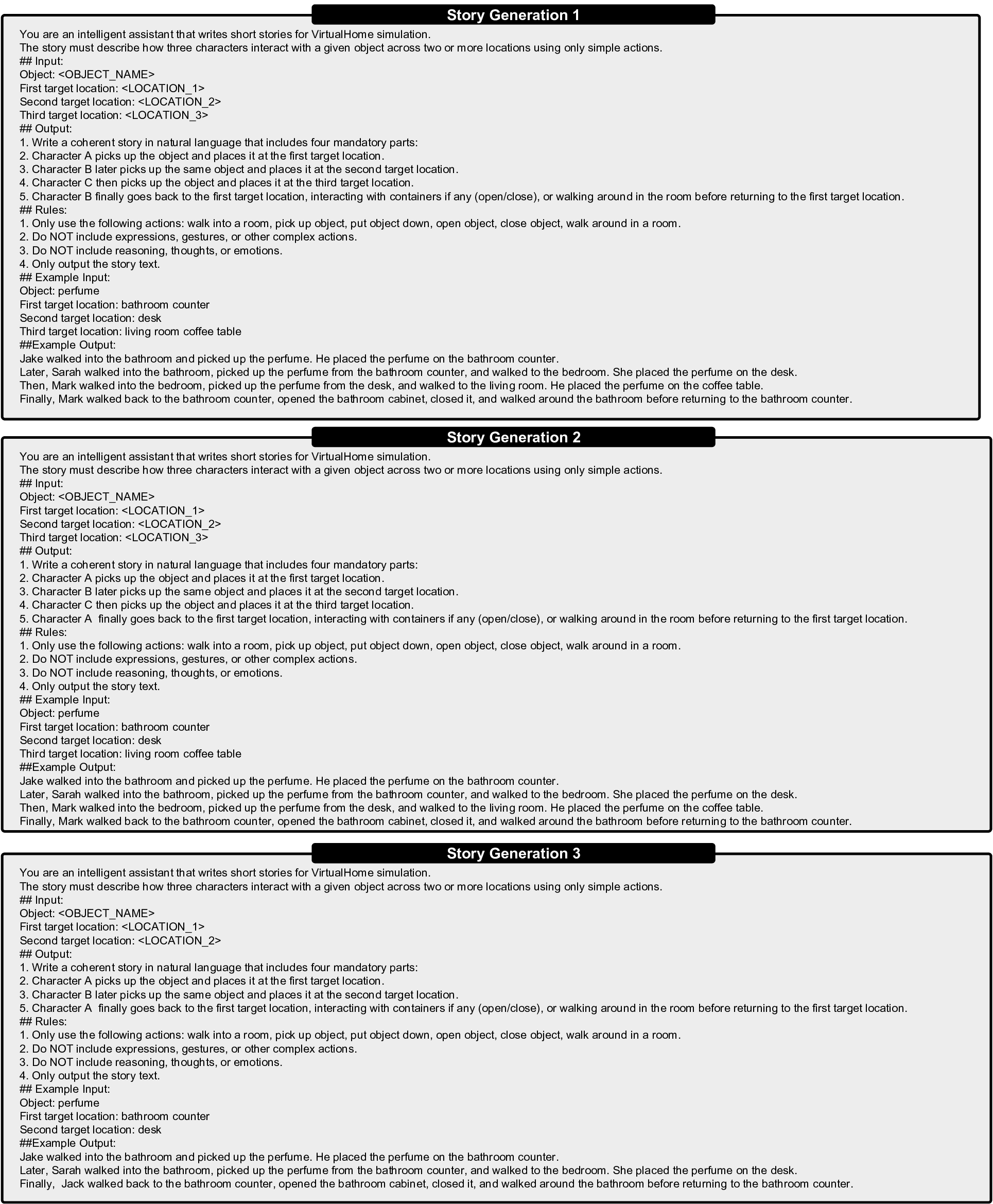

For the False-Belief Correction task, as illustrated in Fig. 7, we follow a taxonomy-driven approach. We first categorize scenarios based on the mapping between Virtu-alHome [34] and ThreeDWorld [15] environments and the typical object distributions in each room (e.g., kitchen, living room). We then determine the number of humans involved in each scene. To cover different numbers of humanoid agents and different target (final) humanoid agents, we design three distinct prompt templates for GPT-4o to generate story scripts. When issuing each request, we iterate over a predefined list of objects along with their corresponding start and end locations. The prompts are shown in Fig. 16.

For the Implicit Goal Inference & Completion task, we design four types of scenarios to comprehensively evaluate agents’ goal-inference abilities:

(1) Special populations. We include scenarios featuring individuals with unique physical conditions: a wheelchair user and a 1.2-meter-tall child. A wheelchair user faces mobility and height limitations, while the child cannot reach high places. We design stories that incorporate these constraints so that the hidden goal must be inferred through contextual cues rather than physical actions.

(2) Object-centric property reasoning. We exploit special physical properties of household objects to construct implicit goals. For instance, since faucets can leak water, we create situations where a person leaves without turning off the faucet. Similarly, because candles provide light, we design scenes where a person reading a book suddenly experiences a power outage and begins walking around; the agent can infer that they are searching for candles (no flashlight is available in the environment).

(3) Functional object combinations. Based on the objects present in VirtualHome and ThreeDWorld, we identify typical usage pairs or triplets. For example, a knife, cutting board, and carrot together imply the goal of cutting carrots. If a person places a cutting board on the table and puts a carrot on it before searching for another object, the hidden goal is most likely to find a knife to complete the task.

(4) Dialogue-driven inference. We additionally design conversational scenarios like MuMA-ToM [40] and Fan-ToM [21] in which implicit goals must be inferred from incomplete verbal exchanges rather than direct physical interactions.

Finally, we collect 200 examples for Implicit Goal Inference & Completion and 390 examples for False-Belief Correction. Among them, 37 examples are adapted from MuMA-ToM [40], where we further augment each story by incorporating a stage-3 “character search” segment, as illustrated in Fig. 8, and 2 examples are sourced from CHAIC [10]. Overall, 113 examples contain a single humanoid agent, 373 contain two agents, and 104 contain three agents. In addition, 17 examples involve agents with special needs, 96 focus on object-centric property reasoning and functional object combinations, and 87 correspond to dialogue-driven inference.

Data Annotation. For each example in the MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy, the annotations are manually created and subsequently verified using GPT-4o [1]. During the annotation process, particularly for the

High-Level Action Set Walk, Run, WalkTowards, WalkForward, TurnLeft, Sit, StandUp, TurnRight, Sit, StandUp, Grab, Open, Close, Put, PutIn, SwitchOn, SwitchOff, Drink, Touch, LookAt, TurnBy, TurnTo, MoveBy, MoveTo, ReachFor, ResetArm, Drop, Animate, RotateHead, ResetHead

For some examples in the False-Belief Correction task, the camera viewpoint prevents certain objects from being visible after they are moved. For instance, we design scenarios where a humanoid agent moves an object from the fridge in the kitchen to the bedroom, but the camera is fixed in the kitchen and cannot capture the final location. As a result, the embodied agent can only infer that the object has been moved, without knowing where it ends up. In such cases, the annotated

We compare our dataset with existing multimodal ToM benchmarks from three perspectives:

• Data source and diversity. To the best of our knowledge, our benchmark is the first to be constructed using two different simulators, which substantially increases the diversity of environments, interaction patterns, and embodied tasks. In contrast, prior multimodal ToM datasets are typically collected from a single simulatorfor example, MuMA-ToM [40], MMToM-QA [18], and BDIQA [32] are limited to VirtualHome, while SoMi-ToM [11] is restricted to Minecraft. • Reasoning paradigm. As shown in Fig. 8, our dataset adopts a Robot-Centric ToM reasoning paradigm, where the agent must infer both the mental states of humans and its own belief state, and then produce decisions and action sequences. Existing multimodal ToM benchmarks primarily focus on inferring human mental states without requiring downstream decision making or action generation. • Evaluation format.

Our benchmark supports openended evaluation, allowing agents to autonomously reason and respond in natural language. This differs from prior datasets, which mainly rely on multiple-choice question formats and therefore cannot reflect real-world embodied decision-making where agents act independently.

We employ two simulators in total, VirtualHome and Three-DWorld, covering 8 different apartment layouts that include dining rooms, bedrooms, kitchens, and bathrooms, as well as 16 humanoid agents consisting of 2 children, 1 wheelchair user, and 13 adults of diverse ages and skin tones. The set of humanoid agents is illustrated in Fig. 12, while the distribution of apartment layouts is shown in Fig. 13.

Detailed Examples of Example 1 in Fig. 1. The Mind-Power Reasoning Hierarchy output of Example 1 in Fig. 1 is:

•

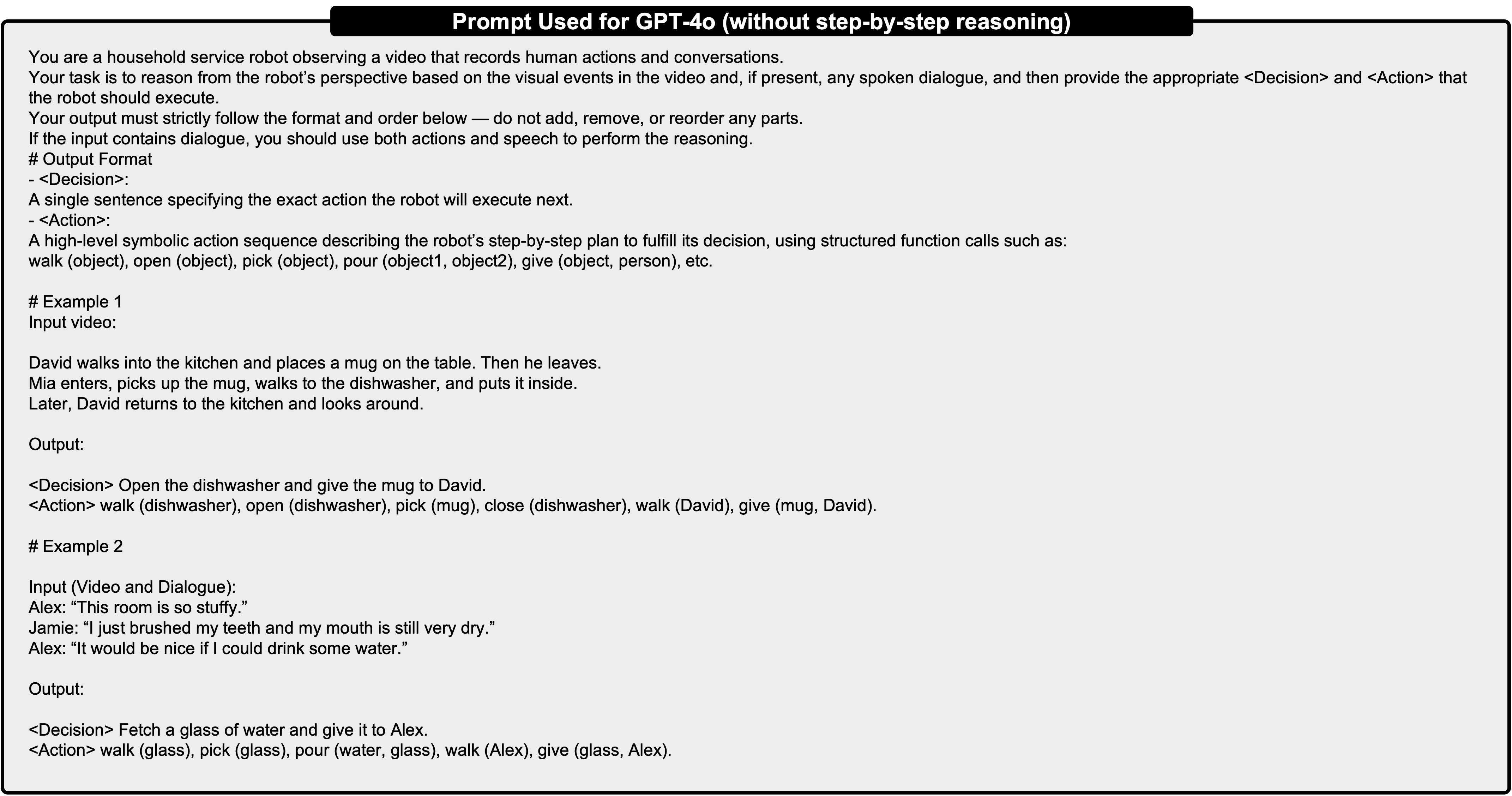

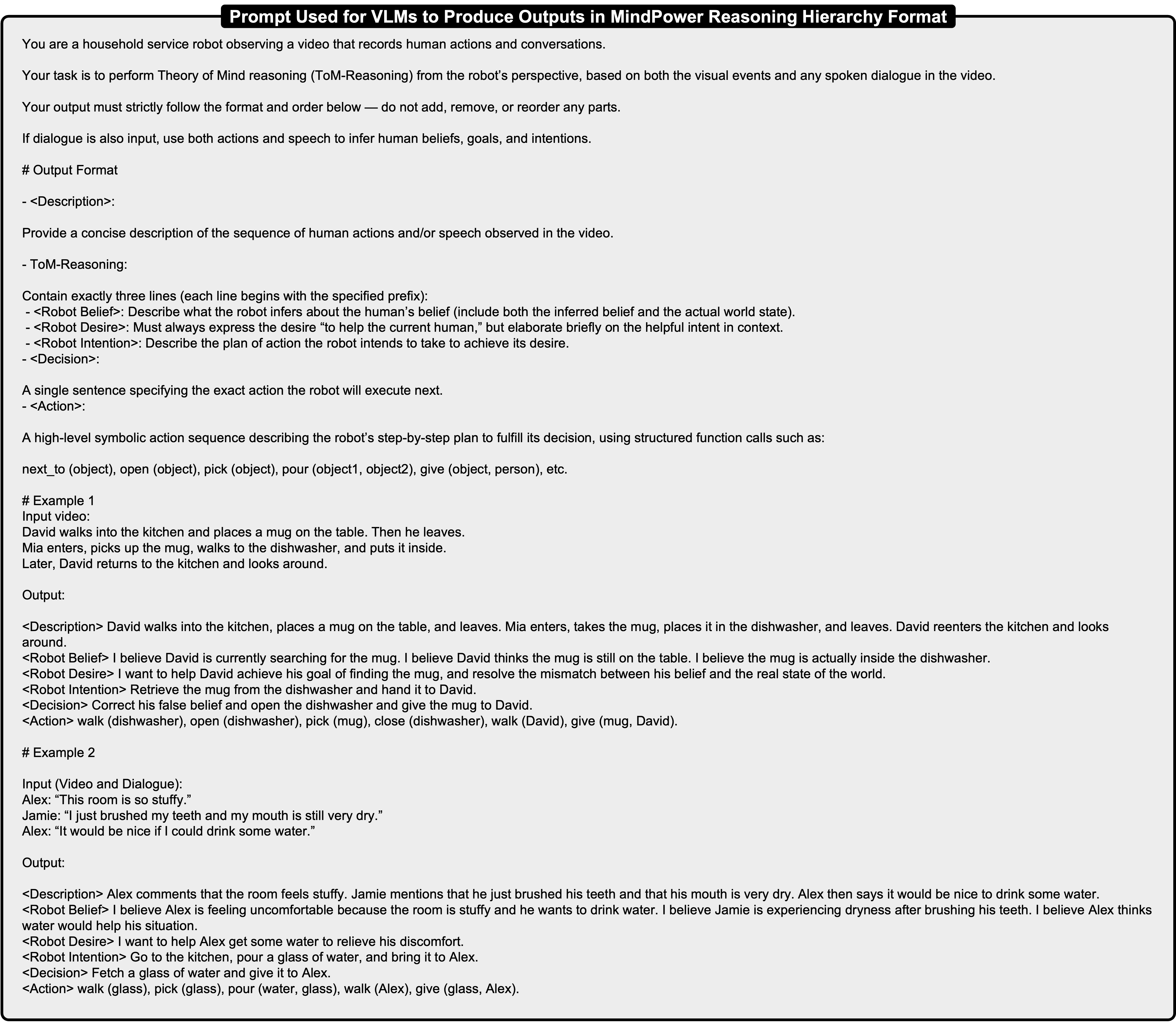

In Sec. 3.4 of Manuscript, we conduct some experiments on MindPower Benchmark. Prompt used for VLMs to produce outputs in Mind-Power Reasoning Hierarchy format. For the experiments in Sec. 3.4 and Tab. 2 of the manuscript, we employed the prompt shown in Fig. 15 to guide the vision-language models (VLMs) to generate outputs in the MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy format.

Prompt used for GPT-4o. In Sec. 3.4 of the manuscript, we use the prompt shown in Fig. 17 to instruct GPT-4o to generate the

In Fig. 4 of the manuscript, we evaluate the Robot-centric score across all VLMs using GPT-4o, with the prompt shown in Fig. 19 to assess whether the model performs reasoning from the robot’s own perspective rather than inferring solely from the surrounding environment. The token character refers to any human identifier in the scene (e.g., char0, char1). However, for the

For the

The prompt used for Qwen3-Max is in Fig. 20.

Can the model still make correct decisions or carry out assisting actions even if the reasoning in the previous layer is incorrect? Even if the model makes errors in object recognition or misinterprets the initial scene, it can still produce correct outputs as long as it correctly identifies the final location of the object. This is because our decisionmaking process is designed to correct for human false be-What can you do for him?

Ours

The man in the wheelchair is sitting at the kitchen counter, looking around the room.

Our method focuses on high-level mental-state modeling and decision making, rather than fine-grained action execution. Current Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models are strong low-level executors, generating gripper motions and stepwise trajectories, but they remain confined to actioncommand prediction and lack explicit reasoning about beliefs, goals, or social context. In contrast, our agent, similar in spirit to PaLM-E [9], performs high-level planning that grounds actions in inferred mental states and task intent. Structured Belief-Desire-Intention (BDI) reasoning enables goal inference and planning that are guided by perspective rather than how to do it. Although our system is architecturally distinct from lowlevel VLA executors, it is inherently complementary to them. The high-level plans produced by our agent can serve as abstract, semantically grounded guidance for downstream controllers. Future work can integrate our model with existing VLA-based executors by simply attaching an action head or a motion-generation module on top of the inferred intentions and subgoals. This design creates a hierarchical embodied agent: our model provides deliberate, interpretable, and socially aligned planning, while low-level VLA modules translate these plans into precise motor actions. Such a combination offers a promising direction toward end-to-end agents that are both cognitively capable and physically competent.

Limitations.

• Due to the constraints of current open-source simulators, our experiments are limited to the environments, humanoid agents, and action sets provided by the simulator. • Our system relies on an explicit MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy, which models the full chain from

• Extend the benchmark to real-world settings beyond simulation. • Develop implicit mental-state modeling based on the proposed MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy to reduce reasoning length while maintaining interpretability. • Expand our scenarios to broader domains, including outdoor environments and human-robot collaboration.

We provide one examples in which humanoid agents, controlled by embodied agents, perform assisting actions in the videos. The example is shown in Fig. 11.

6.43 18.78 15.71 20.77 19.30 17.38 13.97 19.72 12.62 18.77 0.00 0.00 5.95 LLaVA-OV-8B [24] 8.08 26.45 15.09 23.21 22.31 21.40 16.21 19.58 17.11 21.25 0.00 0.00 6.45 Ours Mind-Reward only 21.84 39.99 18.70 27.81 21.35 18.85 21.90 23.30 17.58 24.68 0.28 0.40 6.63 SFT only 32.78 52.72 43.15 42.48 47.01 37.83 34.86 39.48 36.70 43.84 8.50 10.48 8.78

ers, is essential for coherent decision-making in multi-agent interactions involving cooperation, conflict, or deception. ToM Reasoning. In our work, “ToM Reasoning” refers to an agent’s ability to infer others’ mental states and make decisions based on them rather than solely on observable states. Robot-Centric. In our work, by “Robot-Centric” we mean that the embodied agent should reason from its own perspective. It not only needs to infer its own mental states but also reason about how it perceives the mental states of human. Role-Centric. “Role-Centric” refers to the model reasoning about mental states from the perspective of a character within the current story or multimodal input. MindPower Reasoning Hierarchy. In this work, we propose that the model follows the reasoning path

More details can be found in Sec. B of the Supplementary Material.

Details about videos and labels are provided in Sec. B of the Supplementary Material.

3 More examples can be found in Sec. B of the Supplementary Material.

Prompt can be found in Sec. C of the Supplementary Material.

A detailed discussion is provided in Sec. D of the Supplementary Material.

Details can be found in Sec. D of the Supplementary Material.

📸 Image Gallery