From Compound Figures to Composite Understanding: Developing a Multi-Modal LLM from Biomedical Literature with Medical Multiple-Image Benchmarking and Validation

📝 Original Info

- Title: From Compound Figures to Composite Understanding: Developing a Multi-Modal LLM from Biomedical Literature with Medical Multiple-Image Benchmarking and Validation

- ArXiv ID: 2511.22232

- Date: 2025-11-27

- Authors: Zhen Chen, Yihang Fu, Gabriel Madera, Mauro Giuffre, Serina Applebaum, Hyunjae Kim, Hua Xu, Qingyu Chen

📝 Abstract

Multi-modal large language models (MLLMs) have shown tremendous promise in advancing healthcare. However, most existing models remain confined to single-image understanding, which greatly limits their applicability in real-world clinical workflows. In practice, medical diagnosis and disease progression assessment often require synthesizing information across multiple images from different modalities or time points. The development of medical MLLMs capable of such multi-image understanding has been hindered by the lack of large-scale, high-quality annotated training data. To address this limitation, we propose a novel framework that leverages license-permissive compound images, widely available in biomedical literature, as a rich yet underutilized data source for training medical MLLMs in multi-image analysis. Specifically, we design a five-stage, context-aware instruction generation paradigm underpinned by a divide-and-conquer strategy that systematically transforms compound figures and their accompanying expert text into high-quality training instructions. By decomposing the complex task of multi-image analysis into manageable sub-tasks, this paradigm empowers MLLMs to move beyond single-panel analysis and provide a composite understanding by learning the complex spatial, temporal, and cross-modal relationships inherent in these compound figures. By parsing over 237,000 compound figures and their contextual text for instruction generation, we develop M 3 LLM, a medical multi-image multi-modal large language model. For comprehensive benchmarking, we construct PMC-MI-Bench for composite understanding, manually validated by medical experts. Extensive experiments show that M 3 LLM significantly outperforms both general-purpose and specialized medical MLLMs across multiimage, single-image, text-only, and multi-choice scenarios. Notably, M 3 LLM exhibits strong generalization to real-world clinical settings, achieving superior performance on longitudinal chest X-ray analysis using the MIMIC dataset. This work establishes a scalable and efficient paradigm for developing next-generation medical MLLMs, capable of composite reasoning across complex multi-image scenarios, bridging the gap between biomedical literature and real-world clinical applications.📄 Full Content

Compared to single-image tasks, multi-image tasks hold greater practical significance in real-world clinical workflows [17][18][19] . For example, longitudinal monitoring requires comparing multiple images collected across different time points to track disease progression, while clinical diagnosis often integrates medical images from different modalities to provide a comprehensive understanding of a medical case 20,21 . For instance, oncologists routinely analyze Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans for tumor morphology, Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans for metabolic activity, and histopathology slides collectively to formulate a comprehensive diagnostic picture 20 , while cardiologists and neurologists similarly combine modalities like echocardiography, Computed Tomography (CT), and functional MRI to evaluate heart disease and brain disorders 22,23 . These multiple-image scenarios, which constitute a substantial portion of clinical workflows, demand the composite understanding capabilities that synthesize information across multiple medical images. However, existing MLLMs [5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12] fail to adequately address these, severely limiting the applicability and adoption. The scarcity of multiple-image MLLMs stems largely from a fundamental data challenge. Medical imaging data is inherently difficult to collect due to privacy and ethical constraints 13,24 , and the complexity increases substantially for multiple-image datasets that require curated collections of related images across modalities and time points.

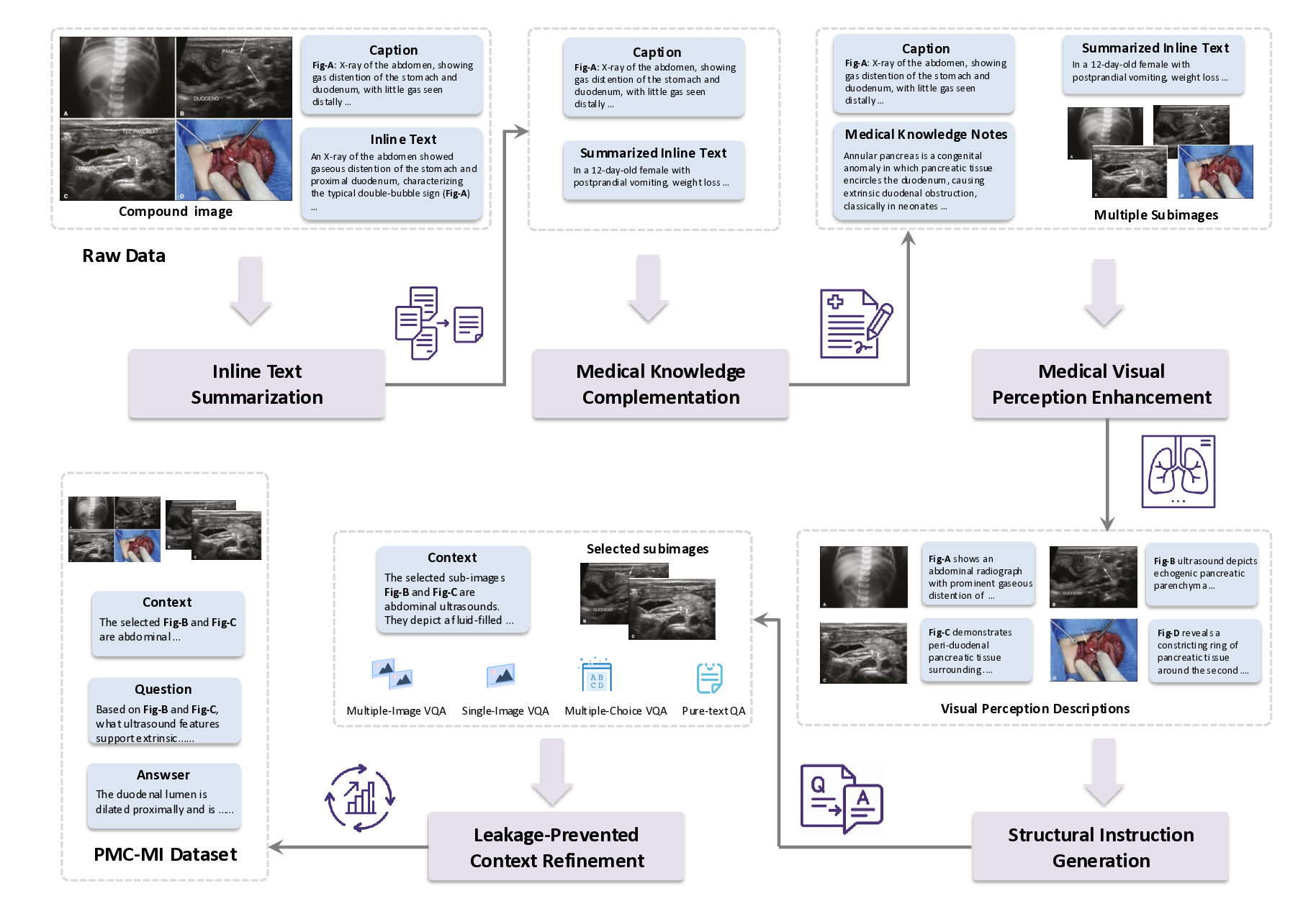

To overcome the critical bottleneck of data scarcity, we turn to compound figures from license-permissive biomedical literature, i.e., multi-panel figures that integrate multiple sub-images within a single structured layout, where each panel typically represents a distinct but related aspect of the same medical case. Their significance lies not just in their public availability, but in their nature as a rich proxy for real-world clinical scenarios. As exemplified in Fig. 1, the compound figure exhibits the diverse inter-image complexities, including spatial arrangements highlighting anatomical correspondence, cross-modal combinations integrating complementary diagnostic information from CT and histopathology images, and temporal sequences showing disease evolution with postoperative examination. These complex relationships demand fundamentally more advanced reasoning capabilities compared to single-image understanding. As such, traditional instruction generation methods 5,9 , primarily designed for single-image scenarios with straightforward image-text pairing, fail to capture the multi-dimensional dependencies inherent in compound figures, thus presenting a significant methodological challenge for composite understanding.

To address these challenges, we present the first systematic MLLM framework specifically designed for medical multiple-image understanding, by leveraging the compound figure data derived from biomedical literature. Our primary contribution is a novel five-stage, context-aware instruction generation paradigm underpinned by a divide-and-conquer strategy. This paradigm decomposes the complex challenge of compound figure understanding into a sequence of manageable, specialized tasks, ranging from medical knowledge complementation to visual perception enhancement, to transform raw compound figures and their associated textual content into Figure 1: Illustration of a compound figure example in PMC literature. This example, derived from PMC7029651, features a compound figure composed of multiple sub-images. The example highlights longitudinal patient records with radiology and histopathology images for a case of insulinoma located in the neck of the pancreas. It integrates the accompanying image caption, which describes the visual contents, along with inline text from the manuscript that references the compound figure. To fully understand this medical compound figure, it is essential to comprehend the rich visual content and associated textual information. This includes analyzing the spatial, cross-modal, and longitudinal relationships of the sub-images, particularly concerning the first CT scan.

clinically rich and relevant training instructions. Unlike traditional methods 5,6,9 that rely on simple image-text pairing, this paradigm constructs comprehensive learning scenarios that emulate real-world clinical reasoning processes, enabling MLLMs to effectively process and analyze the complex interrelationships inherent in medical compound figures. Then, using this paradigm on a large-scale dataset of over 237,000 compound figures, we develop and train M 3 LLM, a medical multi-image multi-modal large language model, to understand and reason over complex visual and textual information in clinical contexts. Furthermore, to facilitate rigorous benchmarking for this domain, we curate and release the PMC-MI-Bench, an expert-validated benchmark with comprehensive multi-image understanding tasks. Systematic evaluations demonstrate that M 3 LLM significantly outperforms state-of-the-art general-purpose and specialized medical MLLMs in multi-image, single-image, text-only, and multi-choice scenarios. Notably, the capabilities of M 3 LLM successfully generalize to clinical practice, as shown by its substantial improvements in a longitudinal patient analysis task using chest X-ray images from the MIMIC database 18,19 , such as disease diagnosis and progression monitoring. To promote transparency and further advancements, we release the weights of our M 3 LLM, the training dataset, and our benchmark to the research community.

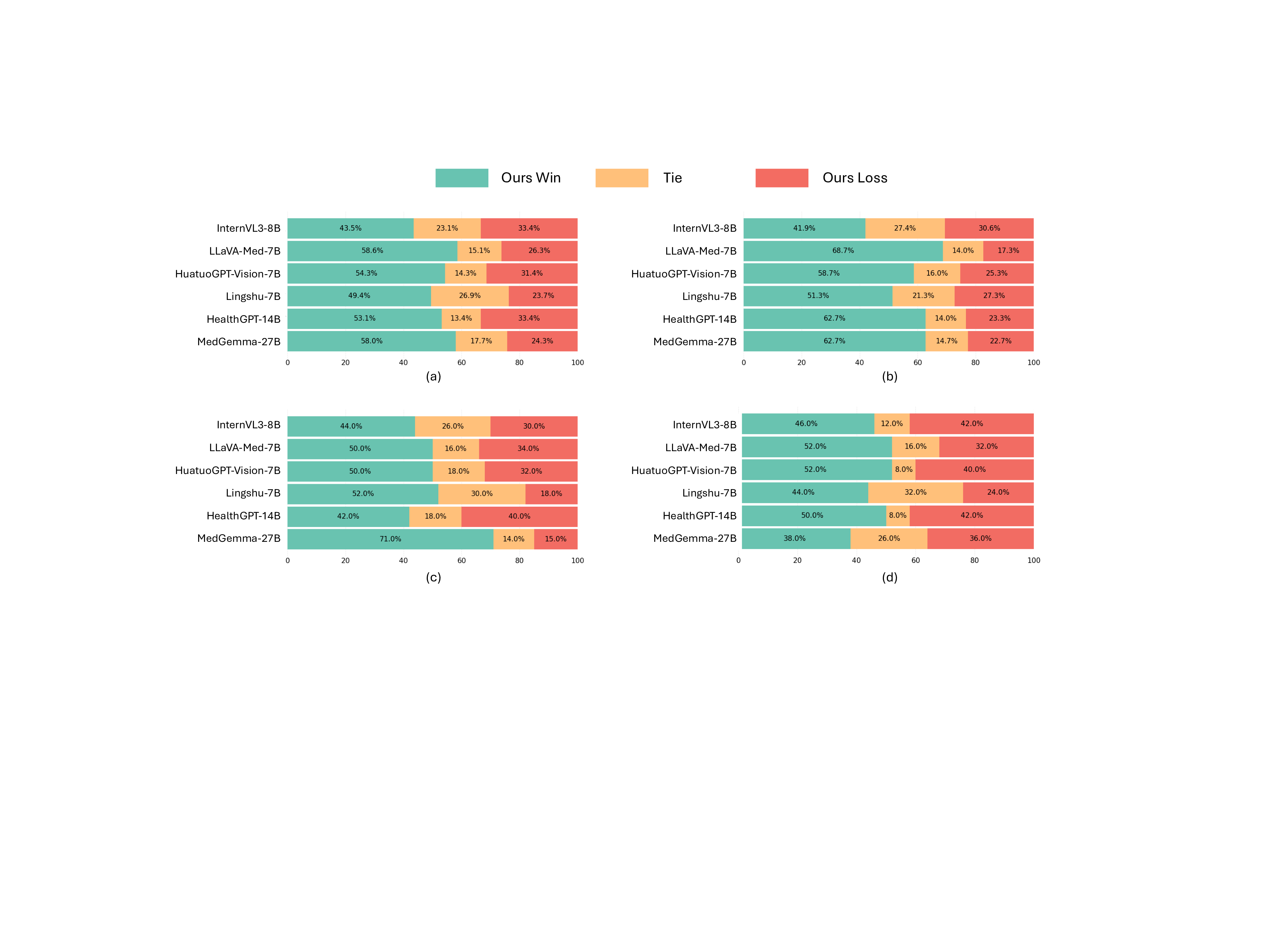

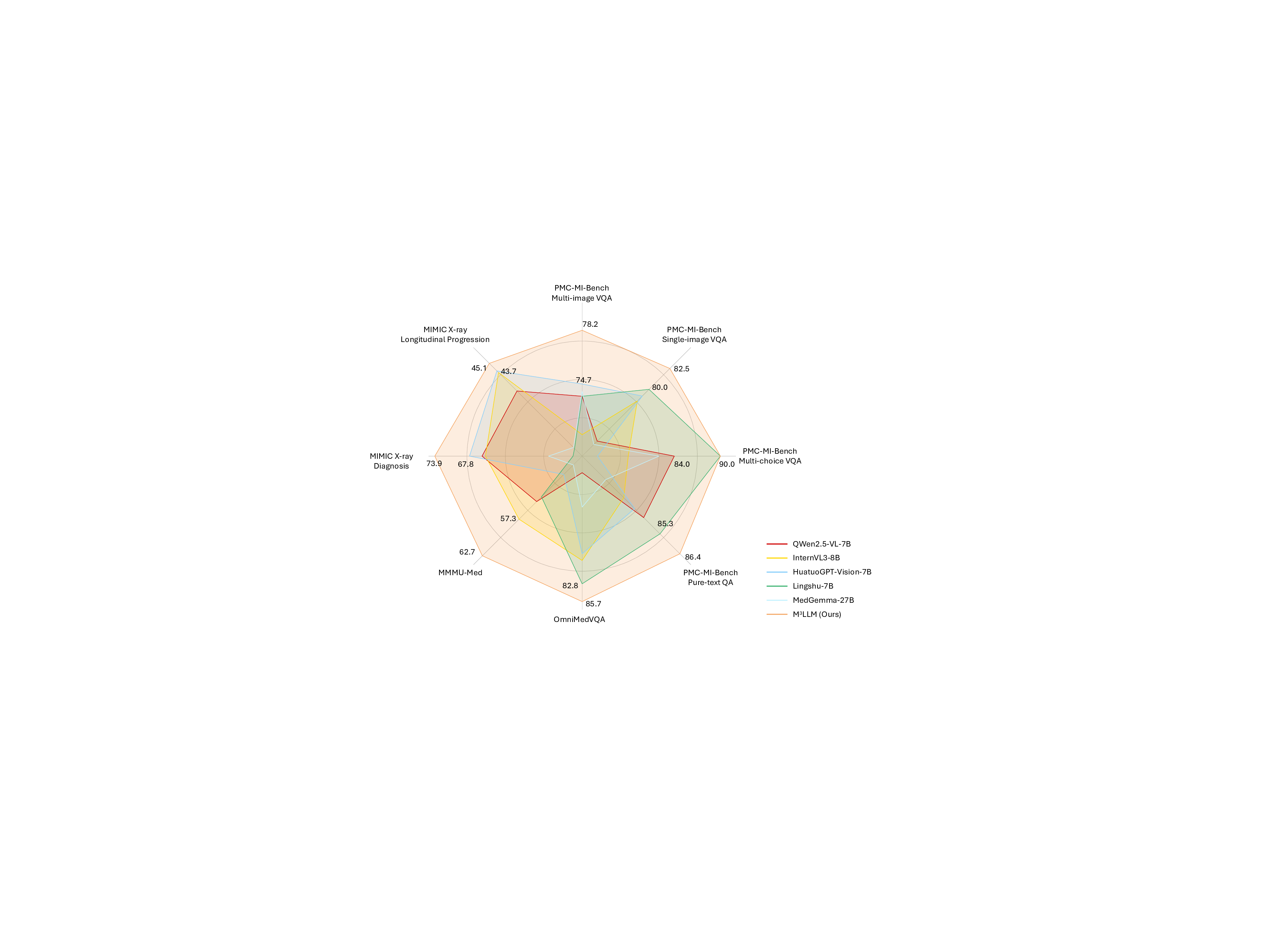

We conduct extensive benchmarking and validation to assess the performance of our proposed M 3 LLM against state-of-the-art general-purpose MLLMs (e.g., LLaVA-7B 1 , LLaVA-NeXT-7B 25 , QWen2.5-VL-7B 2 , and InternVL3-8B 3 ) and medical-specific ones (e.g., LLaVA-Med-7B 5 , HuatuoGPT-Vision-7B 9 , Lingshu-7B 26 , HealthGPT-14B 12 , and MedGemma-27B 27 ). To ensure a comprehensive and diverse evaluation, our experiments assess performance across several key dimensions. We utilize a wide range of datasets, including our newly curated PMC-MI-Bench, public OmniMedVQA 28 and MMMU-Med 29 benchmarks, and a real-world clinical validation task using MIMIC longitudinal X-rays 18,19 . The evaluation spans multiple task types, including multi-image VQA, single-image VQA, text-only QA, and multi-choice VQA. We employ a robust suite of evaluation metrics, ranging from accuracy for classification tasks to semantic metrics, including BLEU@4, ROUGE-L, BERTScore, and Semantic Textual Similarity (STS), and LLM-as-a-judge using GPT-4o for open- 3 LLM processes medical compound figures and paired texts. The core architecture of M 3 LLM includes a Vision Transformer (ViT), a connector module for visual-to-text alignment, and a large language model (LLM) for clinical reasoning. On this basis, the context-aware instruction tuning enables efficient and accurate multi-image comprehension. Extensive evaluation is conducted on the curated PMC-MI-Bench, public benchmarks, and MIMIC clinical cases. ended generation. A holistic visualization of these comparisons in Fig. 3 concisely demonstrates that M 3 LLM achieves superior and well-rounded capabilities across this diverse suite of tasks. In this section, we detail these findings, followed by comprehensive ablation studies and a manual quality assessment of our generated PMC-MI dataset for training.

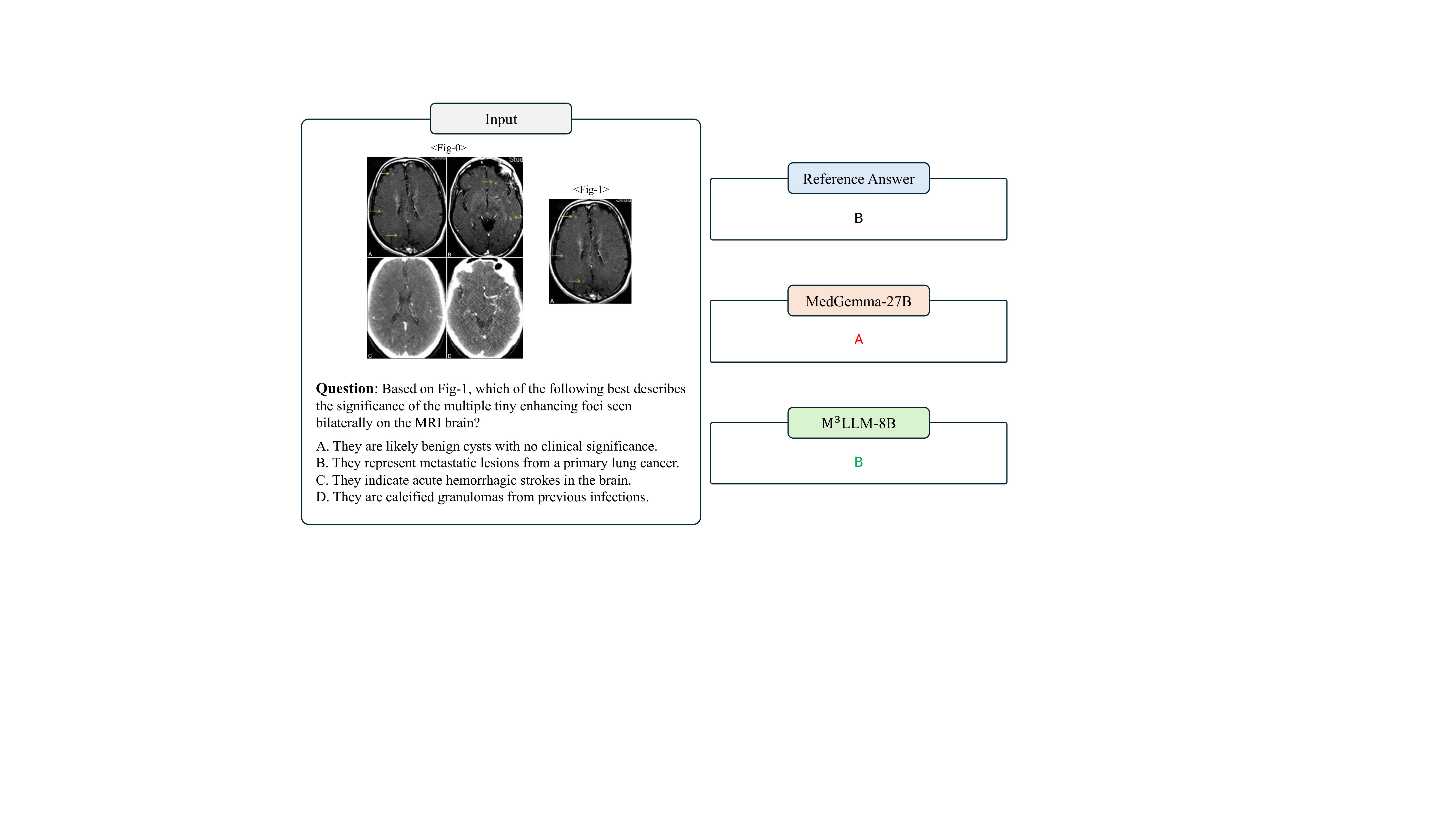

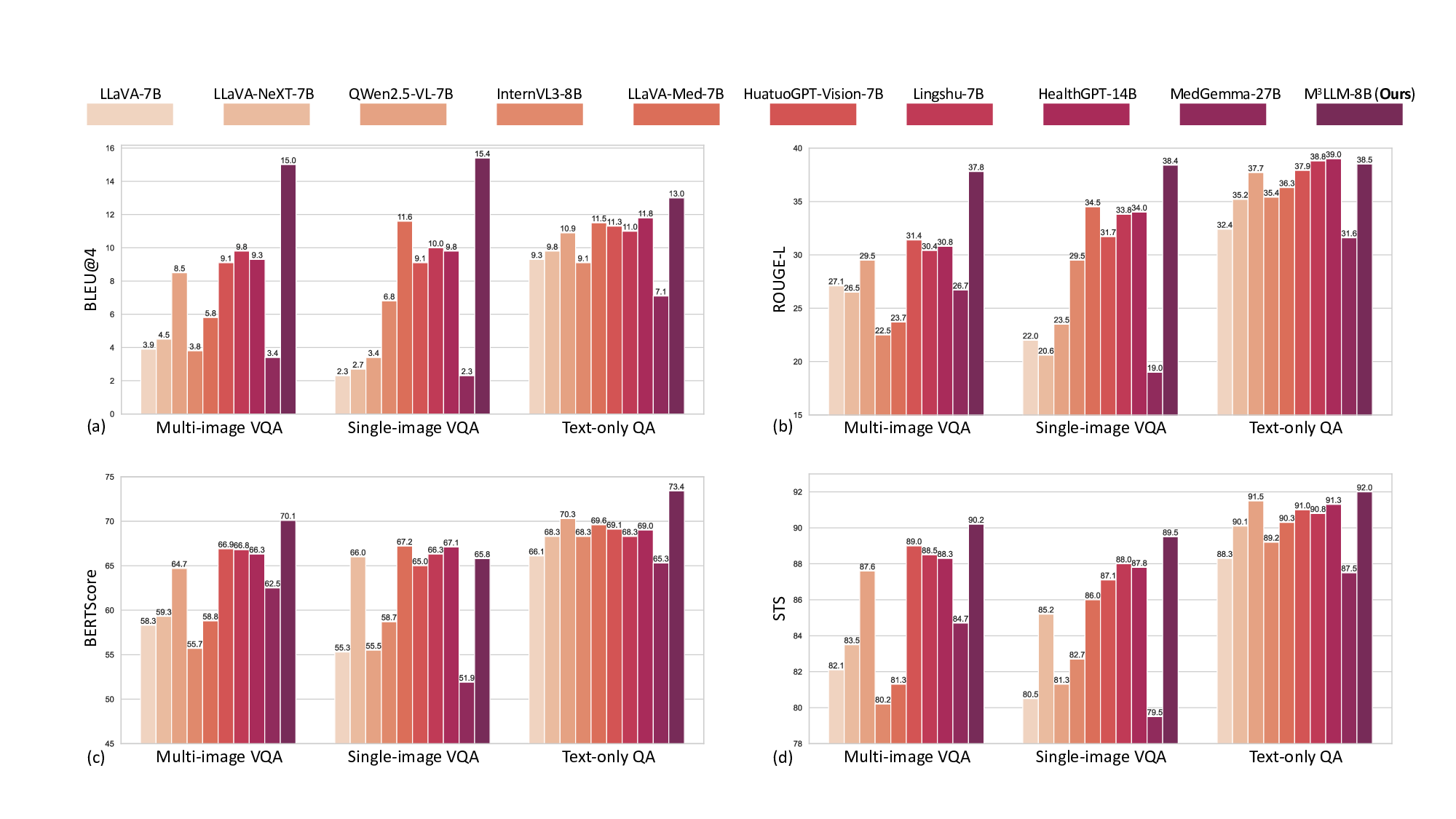

We conduct comprehensive comparisons with state-of-the-art MLLMs across four instruction types of the curated PMC-MI-Bench, including the multi-image VQA, single-image VQA, text-only QA and multi-choice VQA. As elaborated in Table 1, 2, 3, and 4, our M 3 LLM achieves significant improvements across all QA settings, substantially outperforming existing MLLMs 1-3, 5, 9, 12, 25-27 . These results demonstrate the effectiveness of our five-stage, context-aware instruction generation paradigm in creating clinically relevant training data that enables sophisticated medical reasoning with multi-image, single-image and text-only settings, as shown in Fig. 4.

In the multi-image VQA, our M 3 LLM demonstrates exceptional capability to synthesize information across multiple sub-images for comprehensive medical queries in Table 1, achieving 15.0 BLEU@4, 37.8 ROUGE-L, 70.1 BERTScore, and 78.2 Semantic Textual Similarity (STS) compared to the second-best performance of 9.8 BLEU@4 (Lingshu-7B 26 ), and 31.4 ROGUE-L, 66.9 BERTScore, and 74.7 STS (HuatuoGPT-Vision-7B 9 ). The LLM-as-a-judge evaluation in Fig. 5 (a) further confirms superior quality across semantic reasoning tasks, with our M 3 LLM achieving 58.0% win and 17.7% tie compared to MedGemma-27B 27 . This substantial improvement directly demonstrates the effectiveness of our context-aware instruction generation paradigm, which systematically integrates diverse medical findings across multiple imaging perspectives.

For the single-image VQA and text-only QA, our M 3 LLM also achieves superior performance in metrics of BLEU@4, ROUGE-L, Semantic Textual Similarity (STS), and the LLM-as-a-judge, compared with state-ofthe-art general-purpose and medical MLLMs in Table 2 and 3 and Fig. 5 (b) and (c). It is noteworthy that LLaVA-Med-7B 5 shows relatively strong performance on automatic text generation metrics like BLEU@4 and ROUGE-L. This can be attributed to its pretraining strategy, which is specifically optimized for medical caption generation. While this focus enhances its ability to produce linguistically aligned outputs, it does not translate as effectively to tasks demanding deeper clinical reasoning. This is highlighted by its significantly lower accuracy of 46.0% on the multi-choice VQA task (Table 4), where semantic correctness is paramount. In contrast, our M 3 LLM achieves the highest accuracy of 90.0% in Table 4, outperforming the medical MLLM MedGemma-27B 27 with the accuracy of 82.0% and HealthGPT-14B 12 with the accuracy of 88.0%.

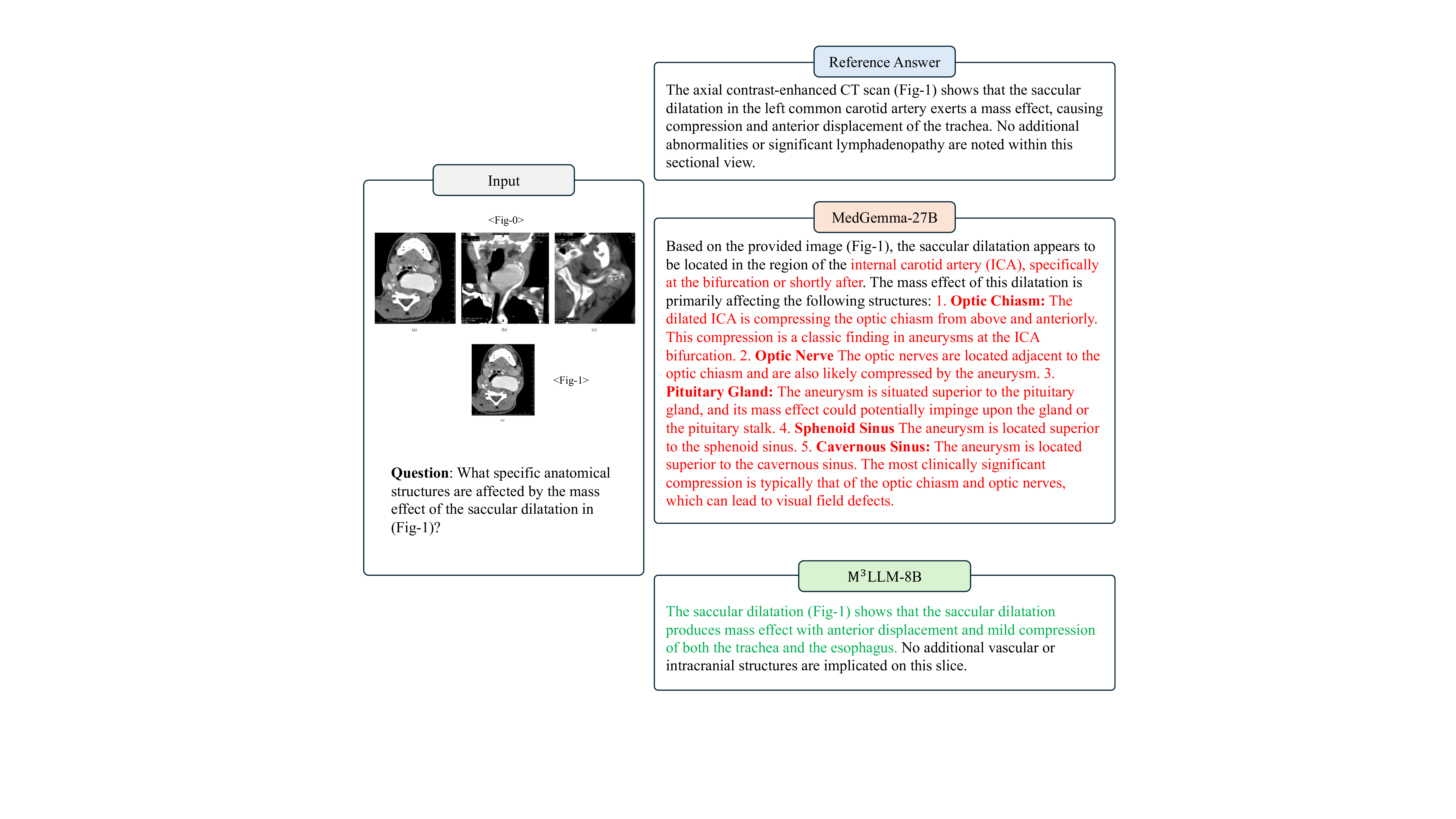

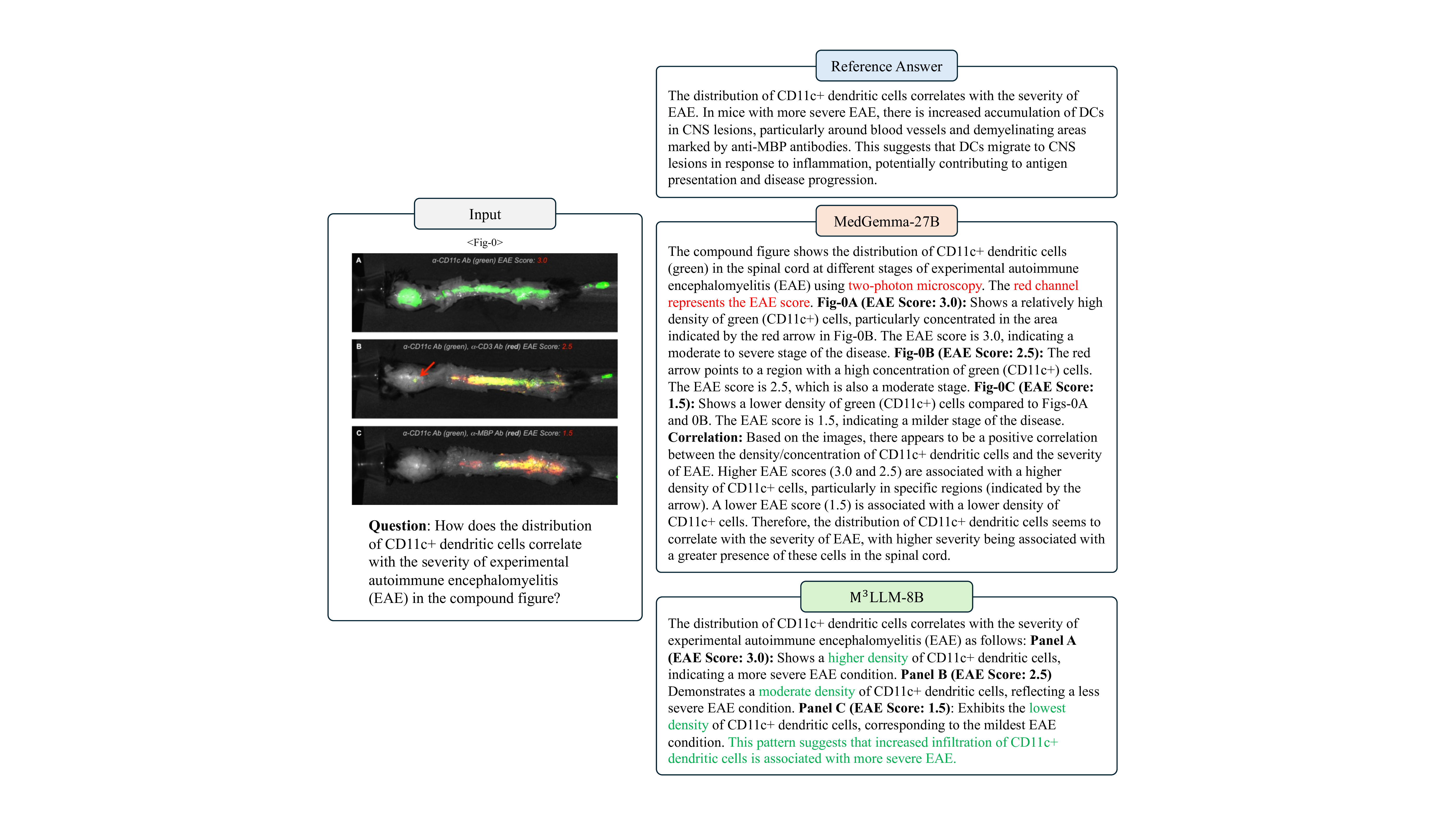

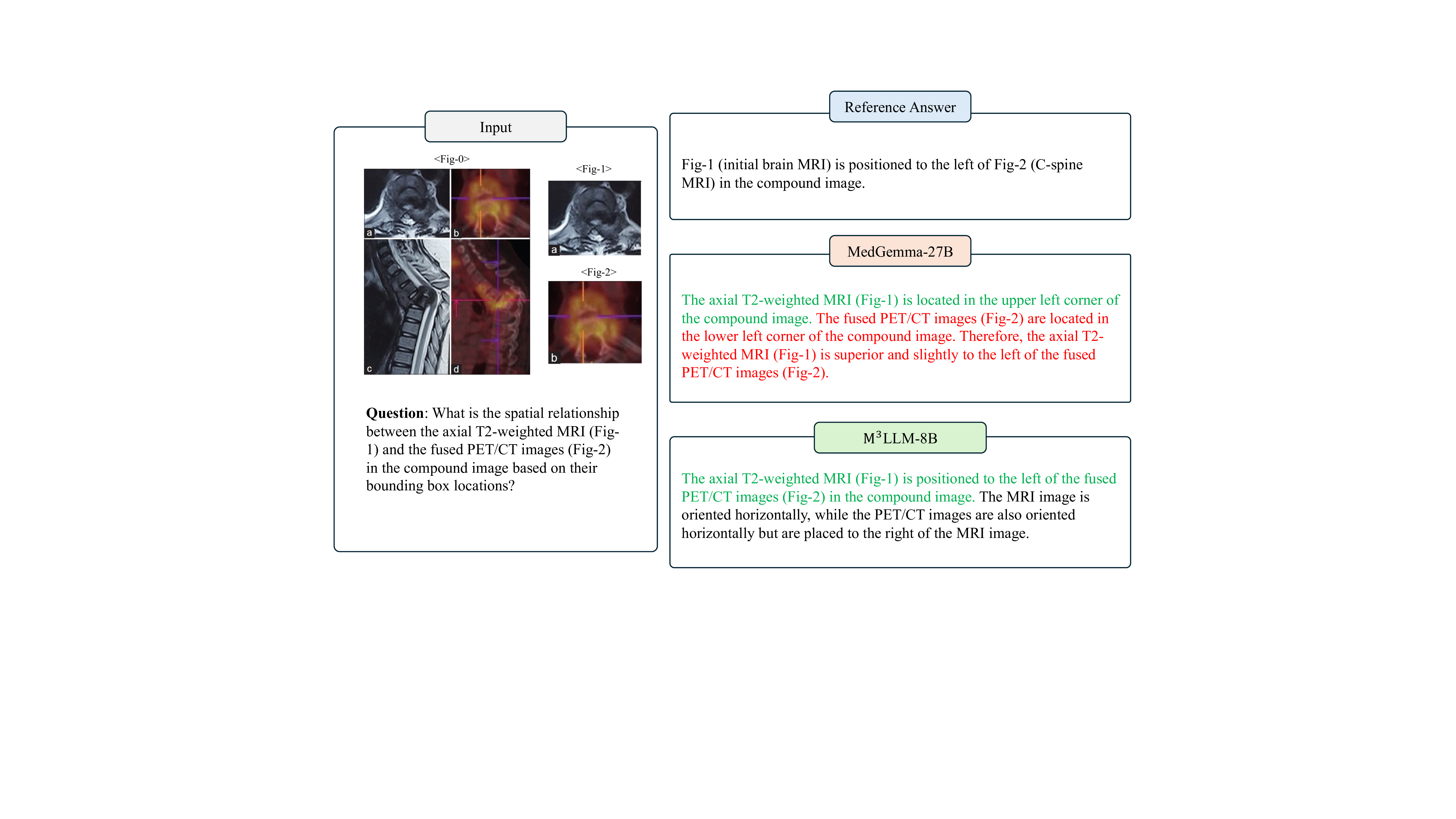

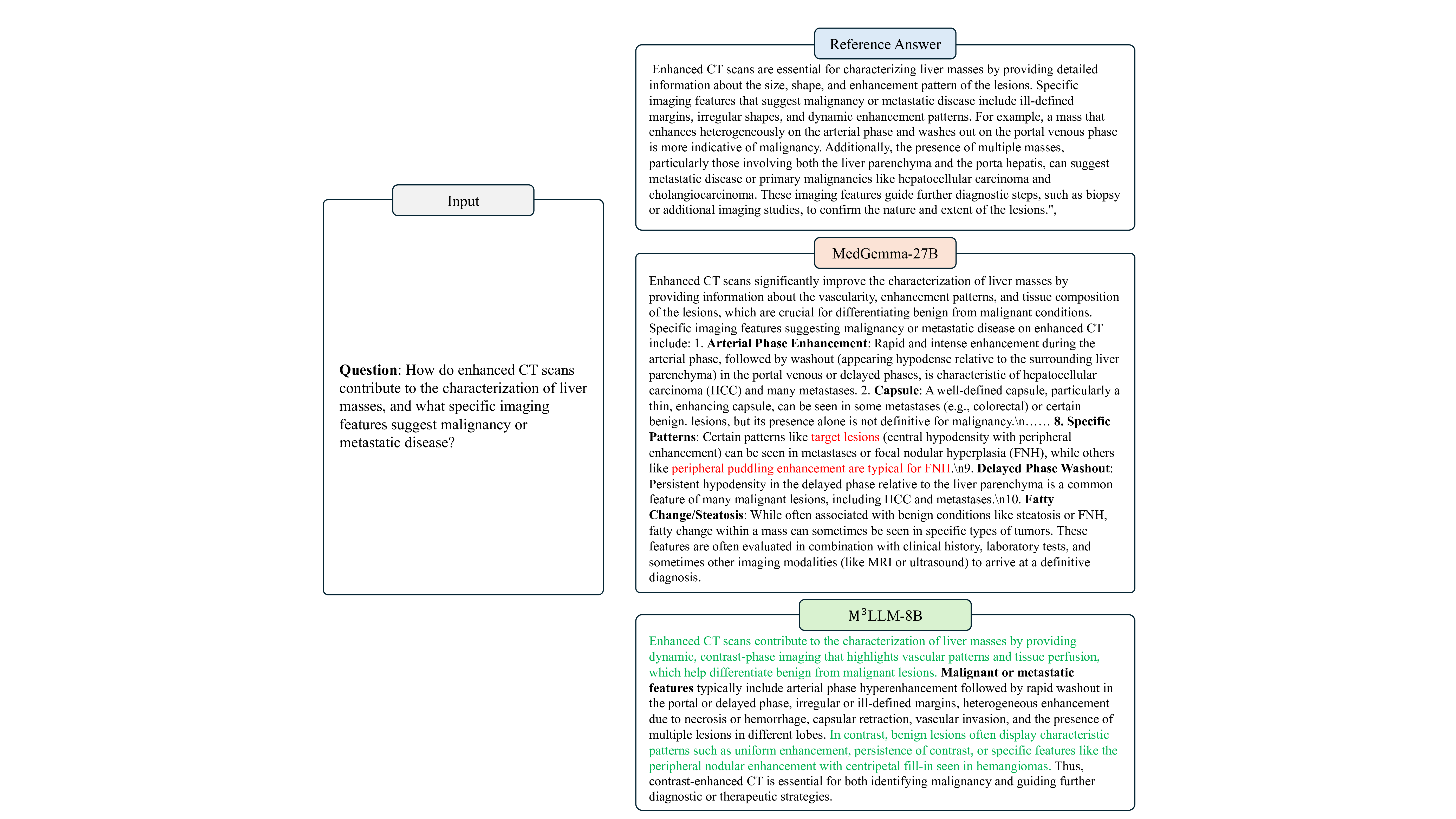

Furthermore, we present the qualitative comparison of our M 3 LLM and MedGemma-27B 27 in Fig. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14 in terms of diverse tasks. These consistent performance advantages fully demonstrate that our M 3 LLM not only has significant advantages in multi-image scenarios, but also can learn effective medical knowledge from context-aware instruction tuning in the single-image VQA and text-only QA tasks, as well as the multi-choice VQA that existing research focuses on, thereby achieving better prediction answers on multiple tasks and metrics.

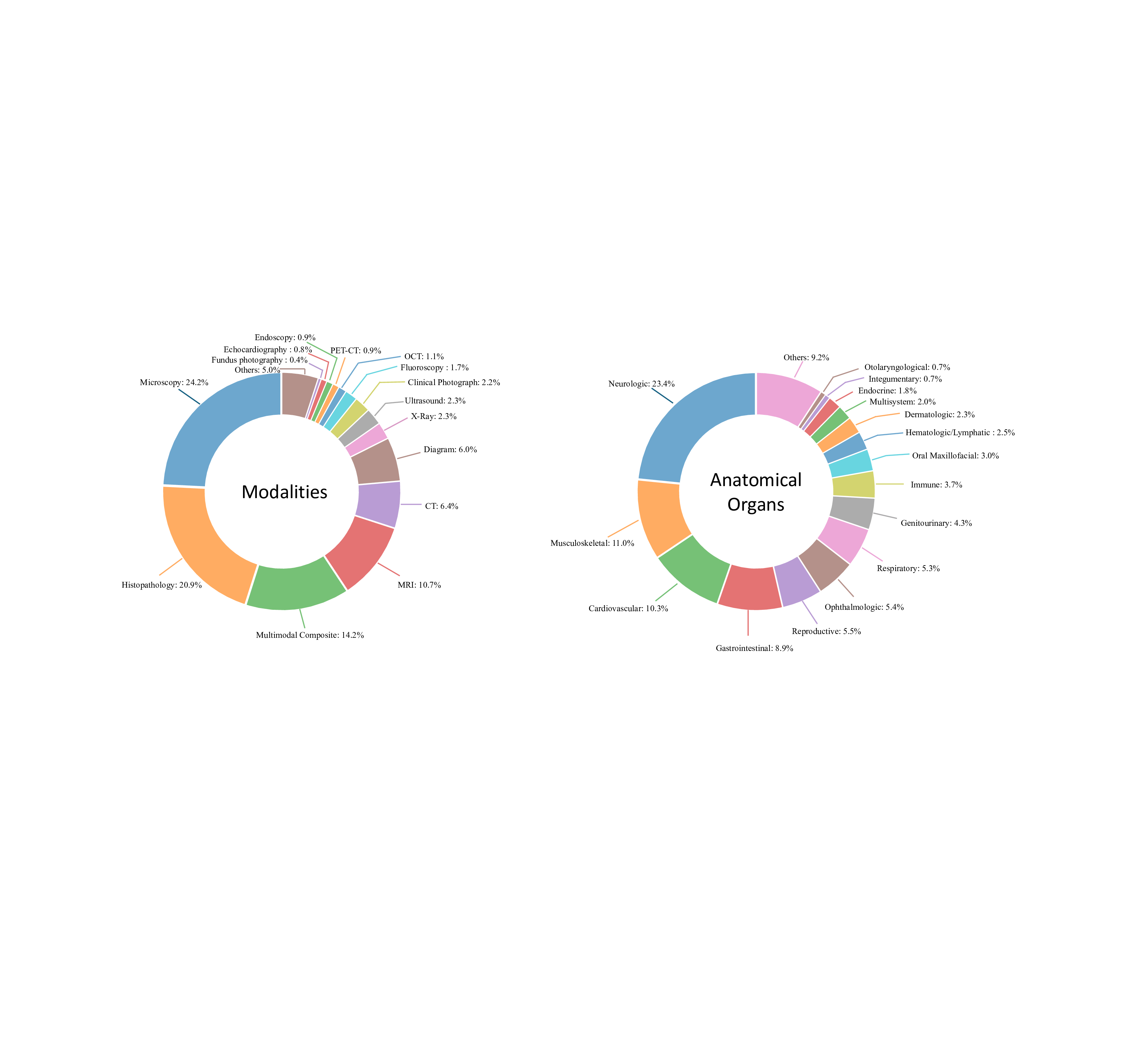

We further compare our M 3 LLM with state-of-the-art MLLMs on public single-image medical benchmarks, including OmniMedVQA 28 and MMMU-Med 29 . Extensive evaluation validates that our comprehensive instruction generation paradigm yields substantial improvements beyond multi-image scenarios, confirming the positive transfer effects of systematic medical knowledge integration achieved through our five-stage, contextaware instruction generation paradigm. On the OmniMedVQA benchmark (in Table 5), our M 3 LLM achieves 85.7% average accuracy across all imaging modalities, substantially outperforming both specialized medical MLLMs (e.g., HuatuoGPT-Vision-7B 9 : 77.9%) and general-purpose models (InternVL3-8B , where our systematic instruction generation captures complex visual-clinical relationships essential for radiological diagnosis. X-Ray analysis shows consistent improvement (88.7% vs. 87.3% of InternVL3-8B 3 ), while microscopy imaging demonstrates substantial gains (83.6% vs. 82.7% of Lingshu-7B 26 ), confirming that our multi-image instruction generation paradigm enhances understanding across diverse medical imaging modalities. It is noteworthy that the performance of our M 3 LLM is not the best in all modalities, particularly Ultrasound (US), Fundus Photography (FP), and Dermoscopy (Der). This directly correlates with the modality distribution of training data (Fig. 7), where these modalities are significantly underrepresented (e.g., Ultrasound samples account for 2.3% and Fundus Photography samples account for 0.4%). The modest performance on these specific tasks highlights the impact of training data diversity and suggests a clear path for future improvement. In general, the exceptional performance of M 3 LLM in major radiological modalities secures its significant advantage in overall average accuracy, confirming the overall effectiveness of our methodology. Furthermore, MMMU Health & Medicine evaluation in Table 6 confirms consistent superiority across medical specialties, with our M 3 LLM achieving 62.7% average accuracy compared to the best baseline model (InternVL3-8B 3 : 57.3%). In particular, the Basic Medical Science (BMS) performance shows particularly strong improvement (63.3% vs. 56.7% of QWen2.5-VL-7B 2 ), directly reflecting the clinical reasoning capabilities developed through our comprehensive instruction generation approach. The Clinical Medicine (CM) reaches 70.0% versus 66.7% of the baseline QWen2.5-VL-7B 2 and InternVL3-8B 3 , demonstrating the enhanced diagnostic reasoning that results from systematic medical knowledge integration. The Public Health (PH) (73.3% vs. 63.3% of InternVL3-8B 3 ) shows consistent improvements, confirming broad medical knowledge enhancement achieved through our proposed instruction generation paradigm.

We investigate the performance of our M 3 LLM to validate the contributions of diverse instructions to substantial performance gains on the PMC-MI-Bench, OmniMedVQA 28 , and MMMU-Med 29 datasets. Specifically, we conduct a detailed ablation study across four types of instructions, including the multi-image VQA, singleimage VQA, multi-choice VQA, and text-only QA, by leveraging or removing one of these four instruction types in the training set. These experiments demonstrate the effects of our comprehensive instruction generation approach and identify the relative importance of each instruction category.

As illustrated in Table 7, compared to the baseline without instruction tuning (Line 1), we observe that different types of instructions bring significant improvements in Semantic Textual Similarity (STS). On the one hand, by adding each type of PMC-MI instructions to the training set, the MLLM can be improved on the same type of samples on the PMC-MI-Bench. In particular, the instructions of multi-image VQA bring a 3.8% STS performance improvement on the same type of the PMC-MI-Bench (Line 2), the instructions of singleimage VQA bring a 1.0% STS performance improvement (Line 3), and the instructions for multi-choice VQA (Line 4) and text-only QA (Line 5) bring a 2.0% STS performance and 4.0% accuracy improvement, respectively. On the other hand, these instructions further improve the performance of other tasks, for example, the multi-image VQA instructions can improve the performance of single-image VQA with a STS increase of 1.9%. This confirms that the generated instructions can provide sufficient medical knowledge to facilitate the model to better complete various types of downstream tasks. Moreover, by leveraging these diverse types of training instructions, the tuned models reveal an impressive advantage over the baseline model on the public single-image benchmarks, with an accuracy increase from 79.0% to 85.7% for OmniMedVQA 28 and from 59.3% to 62.7% for MMMU-Med 29 . These results demonstrate the effectiveness of our designs in the training instruction dataset.

To validate the positive transfer effects across different types of training instructions, we further perform the instruction tuning by excluding one type of instruction samples from the training set (Line 6-9 in Table 7). By comparing the M 3 LLM with all types involved (Line 10), the ablative models confirm that these training data can further promote the performance on different tasks based on other training data, including four tasks on PMC-MI-Bench, as well as OmniMedVQA 28 and MMMU-Med 29 . In particular, single-image VQA can further improve the performance of the model on MMMU-Med by 2.7%. It is worth noting that in the training instructions, multi-choice VQA has a significant performance gain on the public OmniMedVQA and MMMU-Med benchmarks, which shows that the positive transfer of medical knowledge of the same task type is effective. Finally, by comprehensively utilizing the four types of instruction samples in the training set, our M 3 LLM achieves the best performance among these downstream tasks, achieving an increase of 6.8%, 3.9%, 3.1%, and 8.0% in multi-image VQA, single-image VQA, multi-choice VQA, and text-only QA over the baseline (Line 1) on the PMC-MI-Bench, respectively.

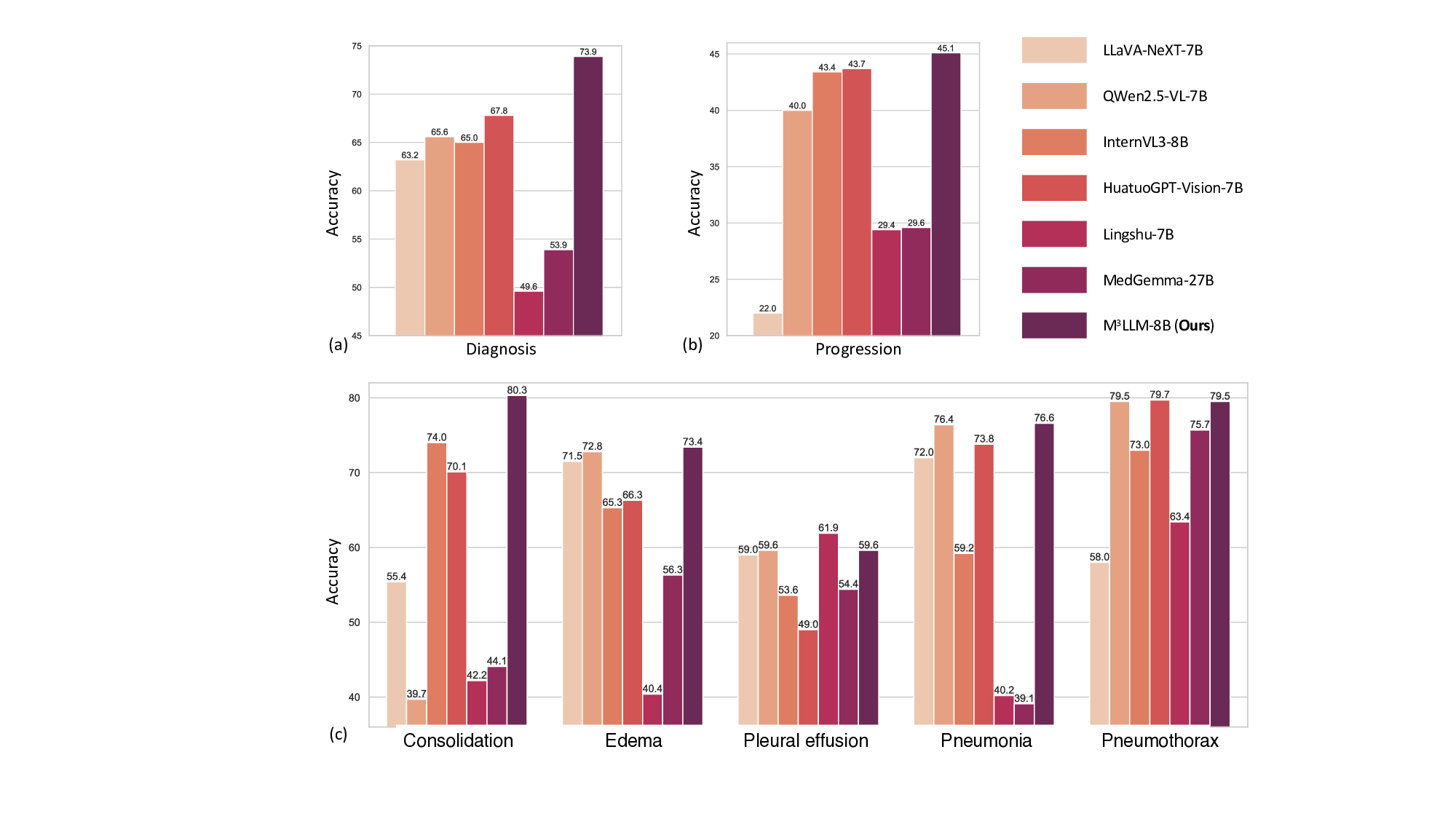

To evaluate the performance of our M 3 LLM in clinical scenarios requiring longitudinal reasoning, we conduct experiments using the MIMIC chest X-ray dataset, as shown in Fig. 6. The dataset is divided at the patient level into a training set and a validation set in a 1:1 ratio, ensuring no patient overlap between the two. The training set is used for fine-tuning all MLLMs, while the validation set is employed for performance evaluation. Each data record in the dataset contains two chest X-ray images from different examinations of the same patient. For the disease diagnosis task, the first examination image is used as input to predict whether the patient has a specific disease. For the progression prediction task, both X-ray images are used to determine the progression of a specific disease, categorizing it as improvement, deterioration, or stability. Furthermore, we calculate the accuracy for cases where both disease diagnosis and progression prediction are correct, offering a comprehensive effectiveness measure of the MLLMs in longitudinal reasoning.

The results, summarized in Fig. 6 (a) and (b), demonstrate that M 3 LLM outperforms all compared MLLMs across both tasks. Specifically, M scores its robustness and clinical applicability. To assess the model’s ability to handle different disease types, we analyze its performance across five conditions: consolidation, edema, pleural effusion, pneumonia, and pneumothorax, as presented in Fig. 6 (c). M 3 LLM achieves the highest accuracy in three out of five disease categories, including consolidation (80.3%), edema (73.4%), and pneumonia (76.6%), and competitive performance on pneumothorax (79.5% vs. the best 79.7%) and pleural effusion (59.6% vs. the best 61.9%). This analysis confirms the model’s capacity to generalize across various diseases and accurately recognize subtle radiological changes associated with each condition. The substantial improvements in disease diagnosis, particularly for diseases like consolidation and pneumonia, underscore the model’s ability to provide timely and precise predictions, which are critical for effective clinical intervention.

Despite the challenges inherent in progression prediction, such as the subtlety and complexity of longitudinal changes, M 3 LLM consistently outperforms the state-of-the-art MLLMs, reflecting the strength of its spatiotemporal reasoning capabilities. The ability to detect nuanced changes in disease progression, whether indicative of improvement, deterioration, or stability, is vital for longitudinal patient care. The accuracy of MLLMs on the chest X-ray dataset, which requires simultaneous success in both disease diagnosis and progression prediction, further underscores its comprehensive understanding of longitudinal medical imaging. The superior performance of M 3 LLM can be attributed to its systematic instruction generation paradigm, which trains the model to effectively capture progression patterns and spatial-temporal relationships. These results demonstrate the potential of M 3 LLM to improve clinical decision-making in real-world longitudinal patient care.

We further conduct the systematic evaluation of M 3 LLM performance across varying training data scales on PMC-MI-Bench, as well as public OmniMedVQA 28 and MMMU-Med 29 benchmarks. These results in Table 9 demonstrate the relationship between instruction data scale and medical multi-image understanding capabilities, confirming the quality of our instruction generation paradigm and providing insights for optimal deployment strategies. Specifically, the InternVL-3-8B 3 without context-aware instruction tuning serves as the baseline and achieves the accuracy of 79.0% and 59.3% on the OmniMedVQA and MMMU-Med, respectively. On this basis, we increase the ratio of the training set from 0% to 100%. We observe that the M 3 LLM obtains an accuracy increase of 3.1% and 1.4% on OmniMedVQA and MMMU-Med with only 5% of the PMC-MI training set. Further increasing the number of training samples will continue to improve model performance, but the rate of increase will slow significantly. For example, when the number of training samples reaches 30%, the performance of M 3 LLM reaches 83.6% on OmniMedVQA. As we continue to increase the number of training samples, the performance increase remains relatively stable until the full training dataset achieves 85.7% performance. These experimental results show that our instruction data can effectively bring medical knowledge to M 3 LLM. The effect is obvious on a small amount of data, while more data leads to better performance on downstream tasks.

We further conduct the professional medical assessment on the randomly sampled instructions of the PMC-MI dataset to confirm high-quality instruction generation across all stages, as well as substantial inter-annotator agreement supporting reliable quality assessment. In our implementation, we randomly select 140 training samples from five stages, where five samples are selected from each of the six types in each stage, except that spatial relationship and multi-choice VQA instructions do not need to go through the fifth stage of context improvement. Each training sample is evaluated by two medical professionals from the perspectives of correctness, completeness, and clarity. Each item is scored on a 1, 3, or 5 basis, where 5 means the entire sample, including context, question, and answer, is satisfactory, with no error or hallucination, 3 means the sample is generally satisfactory, with one or two minor flaws and no significant error, and 1 means the sample is unsatisfactory, with significant errors. As illustrated in Table 10, our training samples have generally received satisfactory evaluation results, with average scores for correctness, completeness, and clarity exceeding 4 across different stages. During the data preparation phase, our paradigm performs particularly well in the second stage of Medical Knowledge Complementation, achieving an average score of 4.8, indicating that it accurately provides effective and relevant medical knowledge. In contrast, the third stage of Medical Visual Perception Enhancement, proved to be more challenging, with a score of 4.4. This highlights the limitations of current medical MLLMs. Notably, the instructions generated in the fourth stage achieved an average score of 4.6, which was further improved to 4.9 after the fifth stage of Context Refinement. This improvement clearly demonstrates that our pipeline is effective in enhancing the context within the instructions, thereby further improving the overall quality of the instructions.

Inter-annotator agreement analysis. To rigorously quantify the consensus of three medical professionals, we conduct the pilot test to assess the instructions for correctness, completeness, and clarity, and calculate the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) among their assessments on 78 randomly-sampled cases, and the overall ICC of 0.816 for all rated aspects indicates excellent reliability. Dimension-specific analyses further confirmed this strong agreement, with an ICC of 0.867 for correctness, 0.751 for completeness, and 0.720 for clarity. This robust statistical consensus is underscored by a high rate of exact agreement (74.8%) and near-perfect agreement within one-score difference (98.3%), confirming a consistent quality assessment across the independent medical professionals. A detailed analysis of the rare disagreements reveals that conflicts primarily involve nuanced edge cases in clinical interpretation rather than fundamental accuracy issues. Most disagreements concern completeness assessments where evaluators differed on the optimal level of detail required for a specific clinical scenario. Correctness disagreements typically arise in cases involving rare pathological conditions or emerging diagnostic criteria, while clarity disagreements focus on the accessibility of technical terminology for different medical specialties.

To ensure comprehensive evaluation across diverse medical scenarios, we analyze the M 3 LLM with dataset characteristics by randomly sampling 1,000 cases from the PMC-MI dataset. Each case is analyzed using GPT-4o to extract key textual information, including image modality and the anatomical system involved.

The dataset encompasses a wide variety of imaging modalities, as depicted in Fig. 7 (a). The most represented categories are microscopy (24.2%) and histopathology (20.9%), reflecting the critical role of detailed cellular and tissue-level imaging in medical diagnostics. Multimodal composite images, which require integration across multiple imaging types, make up 14.2% of the dataset, highlighting the increasing complexity of modern medical imaging scenarios. Advanced radiological modalities, including MRI (10.7%), CT (6.4%), and PET-CT (0.9%), ensure sufficient coverage of cross-sectional imaging commonly used in clinical practice. Other modalities, such as ultrasound (2.3%), X-ray (2.3%), and clinical photography (2.2%), provide additional diversity, ensuring the dataset captures a broad spectrum of real-world medical imaging scenarios.

For the anatomical systems, neurological imaging accounts for the largest proportion (23.4%) as shown in Fig. 7 (b), reflecting the high prevalence of brain and nervous system studies in clinical and research settings.

Musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems are also well-represented, contributing 11.0% and 10.3%, respectively, while gastrointestinal (8.9%) and respiratory (5.3%) systems further ensure diversity. Ophthalmology (5.4%), reproductive systems (5.5%), and dermatology (2.3%) are included as specialized areas, ensuring the evaluation extends to less common but clinically significant domains.

The diversity of the PMC-MI dataset, both in imaging modalities and anatomical systems, ensures that the proposed M 3 LLM is equipped to handle a wide range of real-world medical applications. It enables the model to excel in single-and multi-image scenarios, integrate information across varied imaging types, and effectively reason about complex longitudinal changes. The inclusion of medical multi-modal multiple-image further guides the model to synthesize information from diverse sources, a critical requirement for addressing complex diagnostic challenges. Together, these attributes make the dataset an invaluable resource for driving advancements in medical image understanding and improving the robustness of AI models in clinical practice.

This study introduces M 3 LLM, a multi-modal LLM tailored to address the unique challenges of medical multiimage understanding. Through its five-stage, context-ware instruction generation paradigm, M 3 LLM demonstrates superior performance in multi-image understanding, single-image understanding, and longitudinal clinical analysis. By leveraging the training on over 237,000 compound figures, M 3 LLM bridges the gap between complex visual biomedical research and real-world clinical applications.

The M 3 LLM represents a significant advancement in handling medical multi-image data, a crucial yet underexplored aspect of medical AI. It excels by integrating information across multiple sub-images to capture complex spatial, contextual, and diagnostic relationships, unlike existing models (e.g., LLaVA-Med 5 , Med-Flamingo 6 , HuatuoGPT-Vision 9 and HealthGPT 12 ) primarily focus on single-image tasks [30][31][32] . This superior capability is evident in its performance on the PMC-MI-Bench for multi-image understanding, where M 3 LLM achieves a STS of 78.2, significantly outperforming HealthGPT (73.7) and LLaVA-Med (63.0) in Table 1. This effectiveness stems directly from our five-stage, context-aware instruction generation paradigm, whose core distinction lies in the explicit modeling and learning of composite reasoning. While advanced MLLMs like InternVL3 3 and QWen2.5-VL 2 possess the architectural capacity for multi-image input, their training lacks clinically meaningful fine-tuning specific to medical scenarios and, crucially, does not systematically enforce the synthesis of information across images. They may learn implicit associations when presented with multiple images, but they are not explicitly taught to analyze the spatial, temporal, or cross-modal relationships that define complex medical cases. Our paradigm directly addresses this gap by creating tasks that require the model to compare sub-images, track changes, or integrate findings from different modalities (e.g., CT and histopathology in Fig. 1). Through this process, we are fundamentally shaping the model’s reasoning capabilities to handle multi-dimensional dependencies explicitly, rather than just fine-tuning for medical content. This methodological advantage is the key driver of M 3 LLM’s superior performance in complex medical scenarios and ensures its alignment with real-world diagnostic workflows.

Complementing its explicit modeling capabilities, another key strength of M 3 LLM with multi-image input lies in its ability to perform longitudinal analysis, which is critical for tracking disease progression over time. On the basis of the MIMIC chest X-ray longitudinal dataset, M 3 LLM demonstrated substantial improvements in predicting disease progression and integrating temporal relationships across imaging studies. For example, M 3 LLM achieves higher accuracy in identifying both current pathological conditions and future disease trajec-tories, outperforming baseline models such as HuatuoGPT-Vision 9 and InternVL3 3 , which are limited in their ability to integrate sequential data. This capability reflects the benefits of M 3 LLM’s context-aware training design, which specifically incorporates spatial and temporal reasoning tasks. By enabling dynamic analysis of longitudinal imaging data, M 3 LLM provides a potential solution for chronic disease management, prognosis, and follow-ups.

Beyond these core advantages in multi-image reasoning, M 3 LLM further demonstrates the strength across diverse datasets, tasks, and input settings. By training on a large-scale dataset derived from the PubMed Central biomedical literature, M 3 LLM effectively leverages domain-specific knowledge to handle a wide range of benchmarks from various sources, including MIMIC 18,19 , OmniMedVQA 28 , and MMMU-Med 29 , covering tasks that span from radiology and pathology to clinical question answering. This showcases how biomedical knowledge embedded in PubMed Central data can be utilized to solve problems across distinct domains. Moreover, M 3 LLM also exhibits strong performance across diverse task types, including single-image VQA, text-only QA, and multi-choice VQA. On diverse benchmarks, M 3 LLM consistently achieved state-of-the-art results, demonstrating its flexibility in adapting to the requirements of different task formats. Unlike existing MLLMs that often struggle to generalize beyond single-image VQA, the comprehensive instruction tuning pipeline of M 3 LLM allows it to handle diverse settings effectively. These results highlight M 3 LLM’s ability to generalize its reasoning capabilities from biomedical literature to a variety of clinical scenarios and task types.

On the basis of technical achievements, the clinical implications of M 3 LLM underscore the potential to transform real-world healthcare workflows. In practical settings, M 3 LLM can assist clinicians in synthesizing complex findings from multi-panel imaging studies, such as integrating MRI, CT, and histopathology images to form a unified diagnostic conclusion. This capability reduces the cognitive burden on radiologists and supports faster, more accurate decision-making, particularly in time-sensitive scenarios like emergency care. Additionally, M 3 LLM’s reliance on routine clinical images and textual data makes it a cost-effective and accessible solution for low-resource healthcare settings, where access to advanced diagnostic tools is often limited. M 3 LLM is capable of processing free-text health records and dynamic imaging data, which positions it as a practical tool for diverse healthcare environments.

Despite its strengths, this study has limitations that highlight opportunities for further research. First, the performance of M 3 LLM relies on the diversity and scale of its training data. In scenarios where training data for specific tasks or rare clinical conditions is limited, the model’s performance may degrade accordingly, e.g., the underexplored fundus photography and ultrasound imaging as indicated in Table 5. Addressing this limitation will require curating more diverse datasets, particularly focusing on underrepresented populations, rare diseases, and specialized medical scenarios to ensure robust generalization across all use cases. Second, while M 3 LLM focuses on visual and textual data, integrating additional clinical modalities such as laboratory test results, patient histories, and treatment response data could further enhance its diagnostic capabilities and provide a more holistic understanding of patient conditions. Third, while traditional metrics like accuracy, BLEU, and ROUGE-L provide useful insights into performance, they may not fully capture the nuances of clinical reasoning and decision-making in clinical practice. Developing domain-specific evaluation benchmarks, validated by medical professionals, will be essential for accurately assessing the model’s utility in real-world clinical workflows. By addressing these limitations, future research can further expand the applicability and impact of M 3 LLM in diverse medical contexts.

In conclusion, M 3 LLM represents a significant step forward in medical AI, offering a robust solution for understanding and reasoning over medical multi-images. By addressing the challenges of multi-image analysis and integrating temporal reasoning, M MMMU-Med Benchmark. The MMMU-Med 29 , a specialized subset of the larger MMMU dataset, provides a focused evaluation benchmark specifically for assessing single-image understanding capabilities in the medical domain. For our evaluation, we utilize the labeled validation set, which consists of 150 closedended multiple-choice visual questions. These questions are evenly distributed across five distinct biomedical subjects, with 30 questions per subject. The subjects of MMMU-Med cover Basic Medical Science (BMS), Clinical Medicine (CM), Diagnostics and Laboratory Medicine (DLM), Pharmacy (P), and Public Health (PH).

MIMIC Longitudinal Chest X-ray Benchmark. For clinical longitudinal validation, we utilize chest Xray images sourced from the MIMIC database 18,19 , obtained under appropriate CITI approval and fully deidentified following HIPAA guidelines. The benchmark dataset comprises 1,326 pairs of sequential chest X-ray examinations from individual patients, each paired with ground-truth labels. It specifically focuses on assessing disease progression across five common radiological findings: Consolidation, Edema, Pleural effusion, Pneumonia, and Pneumothorax. For each finding, the progression between the two examinations is categorized into one of three states: Improving, Stable, or Worsening. To ensure a rigorous evaluation that prevents data leakage, the dataset is split into training and test sets at the patient level. This benchmark structure allows us to evaluate the model’s longitudinal reasoning capabilities in a setting that mirrors real-world diagnostic workflows where clinicians compare serial images to monitor patient status.

6 Methods

We construct a large-scale training corpus by harvesting the open-access subset of PubMed Central. As of June 18, 2024, the repository contained 6,106,189 papers. From this vast collection, we implement a rigorous three-step filtering pipeline to curate a high-quality dataset specifically for medical multi-image understanding.

Step 1: Preliminary Filtering. We first filter the papers to retain only those with licenses permitting research use, reducing the pool to 5,099,175 articles. To efficiently identify relevant content, we employ a fine-tuned PubmedBERT 33 to classify image-caption pairs based solely on their textual content. This textbased pre-screening allows us to rapidly identify 3.7 million potential medical image-text pairs from the 5.1 million papers. We employ a Vision Transformer (ViT) fine-tuned for compound figure detection to effectively distinguish compound figures from single-panel images and non-medical graphics. As a result, we identify 3,156,144 medical compound figures, excluding 643,401 non-compound or irrelevant images.

Step 2: Medical Content Screening. In the second step, we ensure the medical relevance of the images. We further refine this set to ensure high clinical relevance, and employ a specialized DenseNet-121 34 , pretrained on the ImageCLEF 35 , MedICaT 36 , and DocFigure 37 datasets, to distinguish genuine medical imagery from non-medical graphics such as charts and diagrams. As a result, this step retains compound figures only if medical sub-images constitute over 90% of their visual content.

Step 3: Textual Quality Control. In the third step, we apply textual quality controls by establishing minimum length thresholds to guarantee sufficient context for instruction generation. We require compound-level captions to exceed 50 words and individual sub-image captions (if available) to contain at least 10 words.

The application of these three-step criteria systematically refines the initial harvest, resulting in a final, highquality collection of 237,137 compound figures suitable for the subsequent instruction generation process, forming the basis for both the training dataset and the benchmark.

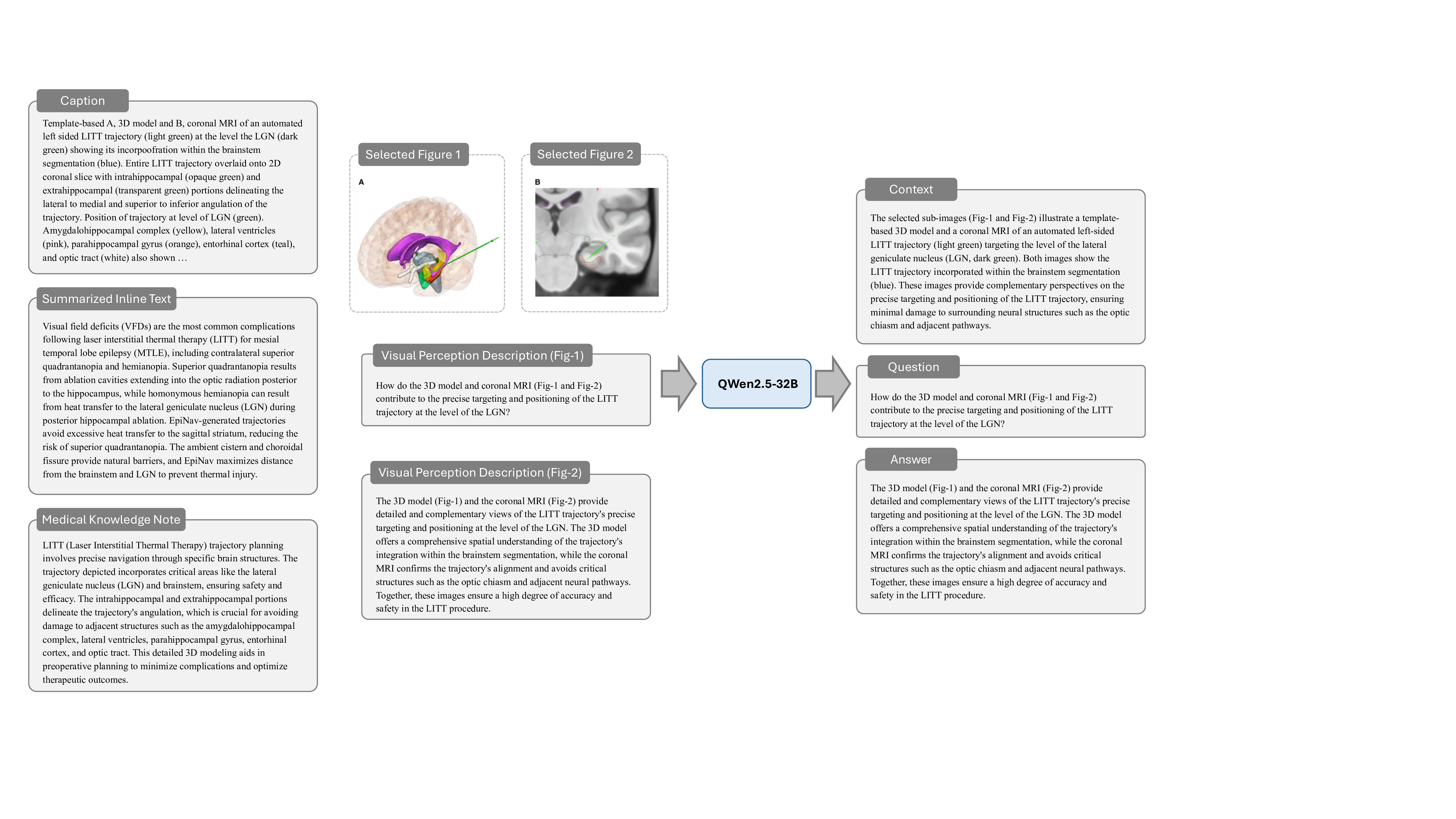

PMC-MI Dataset Generation. Our instruction generation paradigm comprises five interconnected stages designed to maximize information extraction from these filtered medical compound figures. We employ QWen2.5-32B 38 for automatic summarization of inline texts and medical terminology extraction, the advanced medical MLLM HuatuoGPT-Vision-34B 9 for sub-image analysis, and template-based generation combined with large language model creativity to produce four distinct question types covering comprehensive medical image understanding scenarios. The specific details of this five-stage paradigm are elaborated in Section 6.2.

PMC-MI-Bench Curation Process and Professional Examination. From the larger pool of processed data, we randomly select diverse samples across medical specialties and imaging modalities for benchmark construction. Each potential benchmark sample then undergoes a rigorous preliminary screening for medical relevance, complexity suitable for benchmarking, and educational value. This process prioritizes cases that exemplify different aspects of compound figure understanding (e.g., spatial, temporal, cross-modal analysis) while ensuring balanced representation across six defined question categories. Finally, these screened candidates undergo intensive professional validation distinct from the automated dataset generation process. Two board-certified medical professionals independently review each candidate, verifying information consistency between constructed contexts and original source materials, ensuring answer accuracy and completeness, and confirming diagnostic appropriateness. Inter-annotator agreement exceeds 85% across all evaluation criteria, with disagreements resolved through expert consultation. This multi-step process ensures PMC-MI-Bench maintains high quality, clinical relevance, and balanced distribution across question categories, medical specialties, and imaging complexity.

Quality Control Measures. Both the training dataset and benchmark employ automated filtering to remove questions with potential answer leakage, factual inconsistencies, or inadequate medical complexity. PMC-MI-Bench additionally undergoes manual verification of each test case to ensure benchmark reliability and clinical relevance.

We develop a five-stage, context-aware instruction generation paradigm designed to systematically transform medical compound figures and their associated textual descriptions into comprehensive training data. Cen-tral to our approach is a divide-and-conquer strategy that decomposes the complex challenge of multi-image context-aware instruction generation into a sequence of manageable, specialized sub-tasks. This instruction generation paradigm addresses the fundamental challenge of creating instruction data that captures not only visual content but also the complex clinical reasoning, medical knowledge integration, and multi-image relationship understanding required for effective medical compound figure analysis.

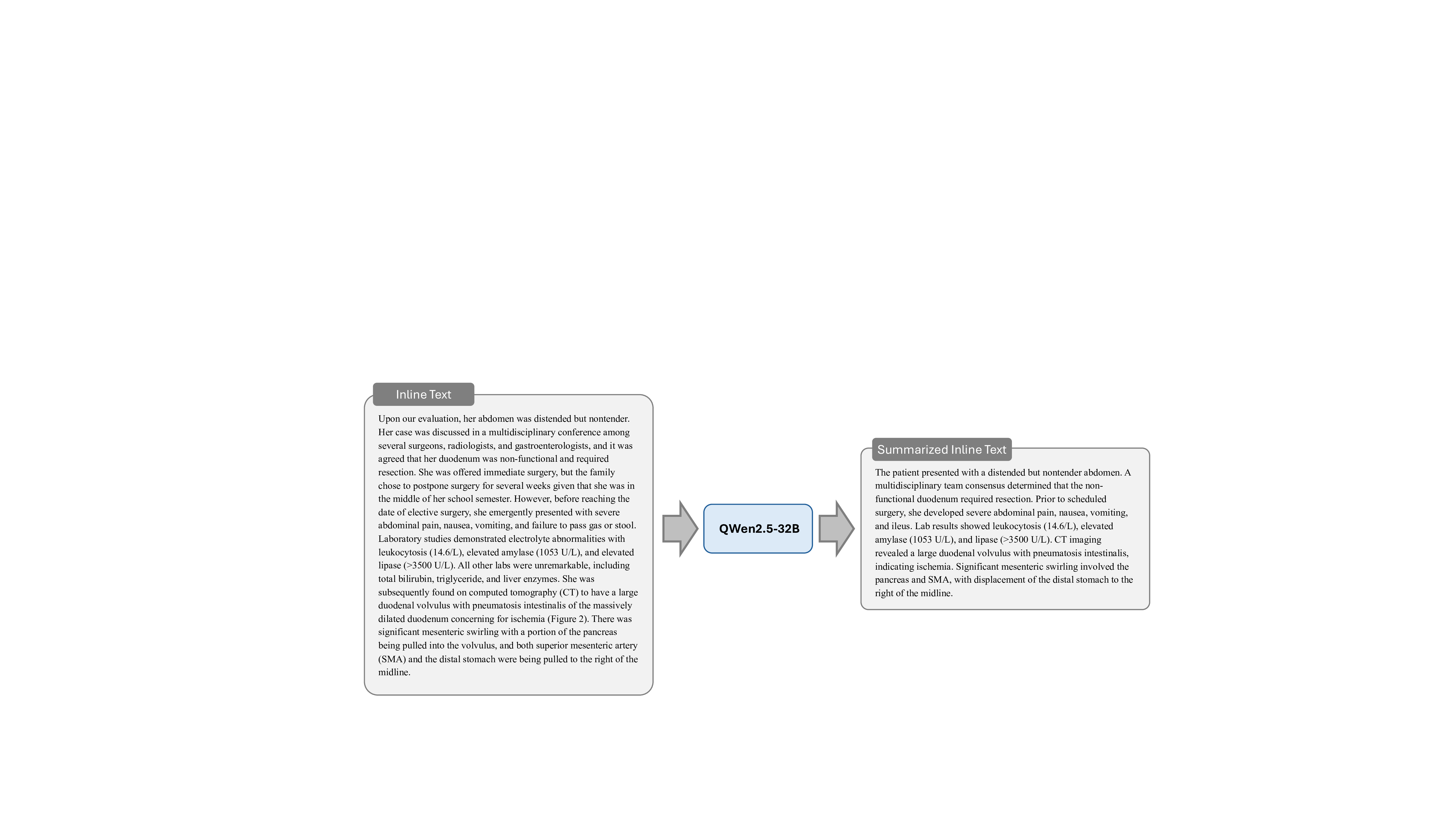

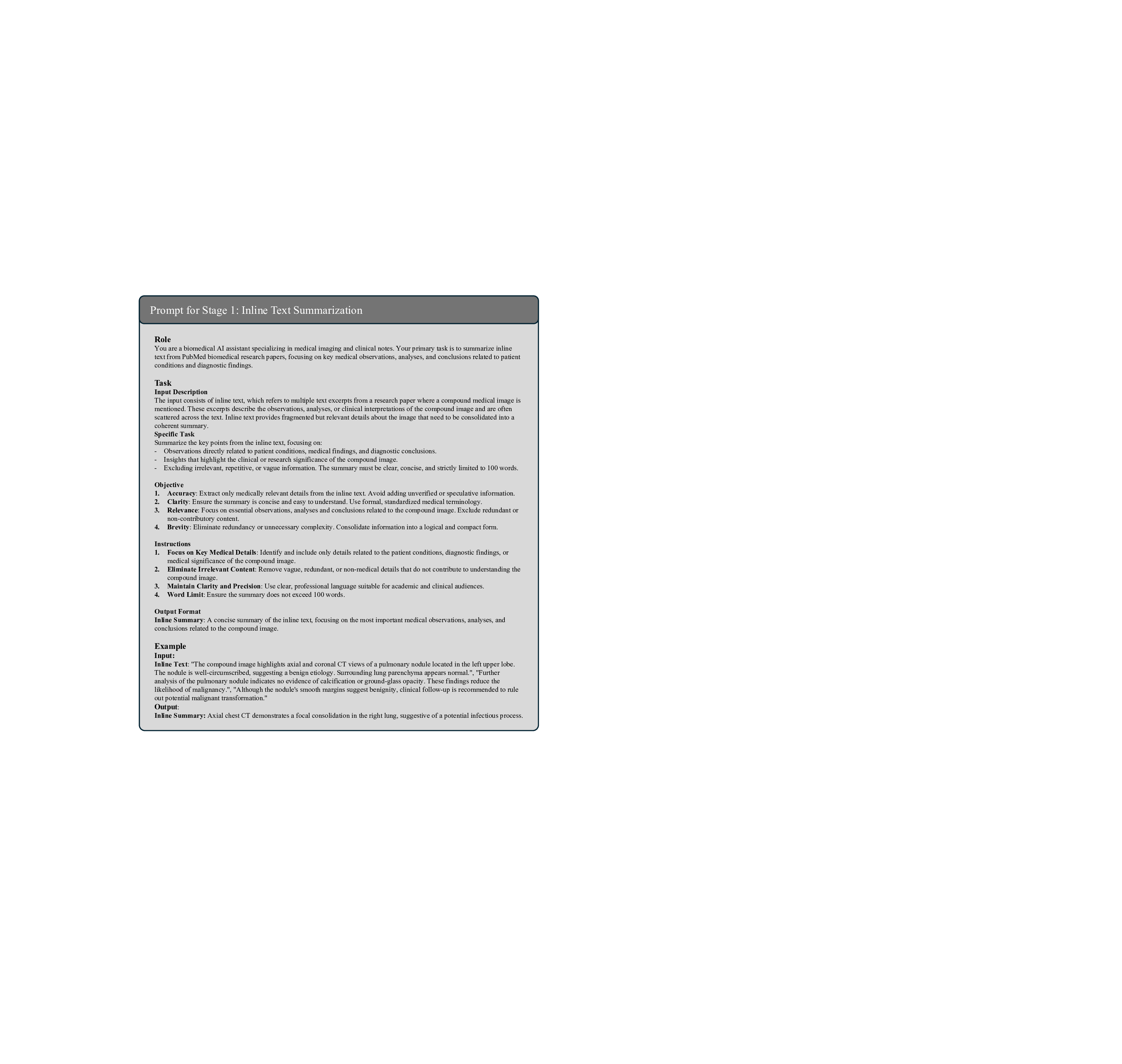

Stage 1: Inline Text Summarization. To address the challenges posed by the often lengthy and verbose inline text from biomedical literature, we employ the QWen2.5-32B 38 to systematically analyze and process the inline text regarding each compound figure. Inline texts in biomedical literature often contain essential clinical insights relevant to compound figure analysis and patient diagnosis, yet their verbosity can hinder the learning and understanding processes of MLLMs. To overcome this, our summarization stage goes beyond simple text extraction by condensing and reorganizing these inline references into concise and coherent clinical narratives. This process focuses on highlighting key information directly related to compound figures and patient diagnosis, such as pathological findings, diagnostic workflows, and treatment outcomes, while removing extraneous details. The resulting summarized texts not only preserve medical accuracy but also streamline complex technical descriptions into accessible formats, laying a foundational clinical context for the subsequent instruction generation paradigm. The prompt of this stage is illustrated in Fig. 15, and an example is elaborated in Fig. 26.

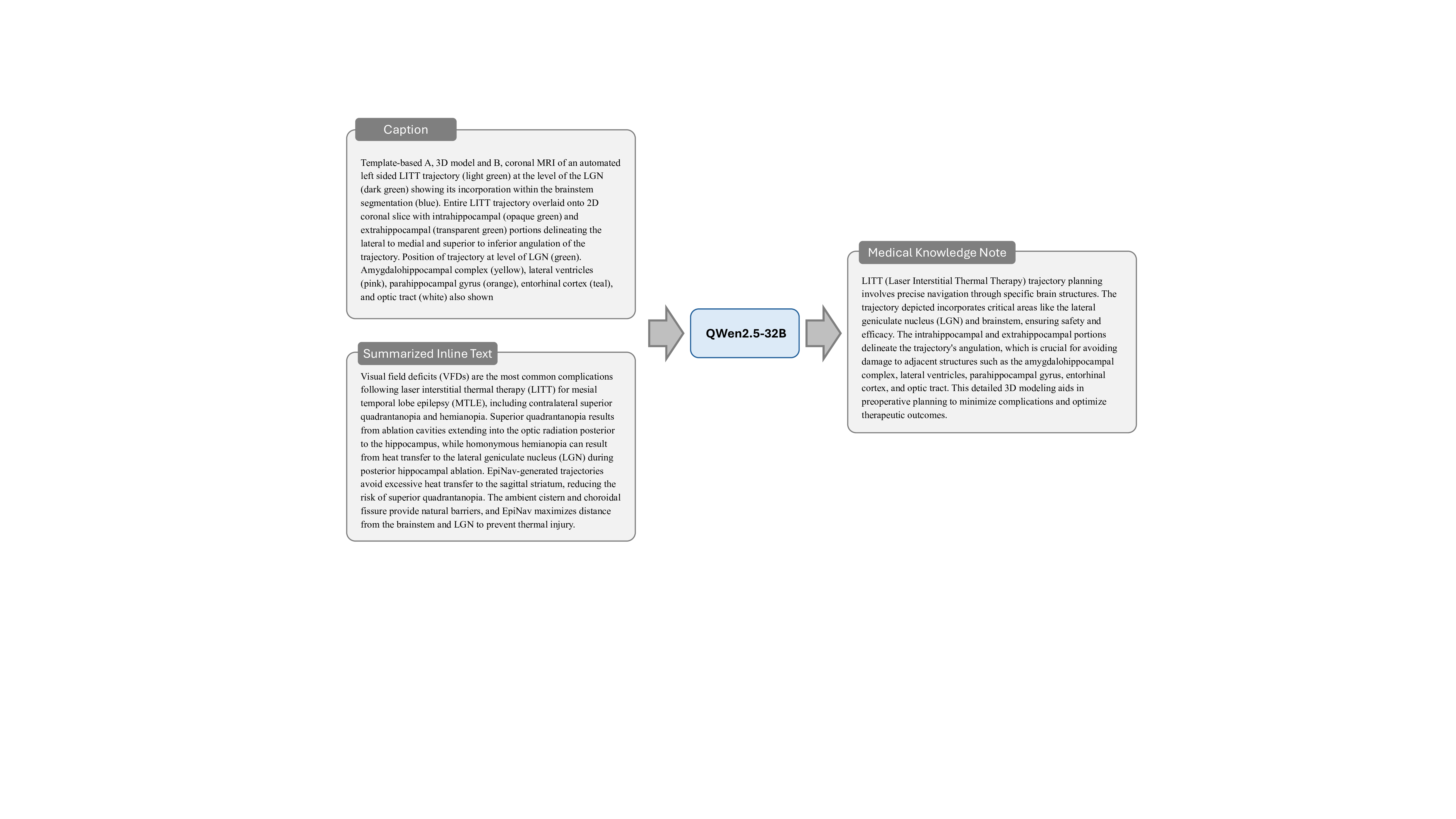

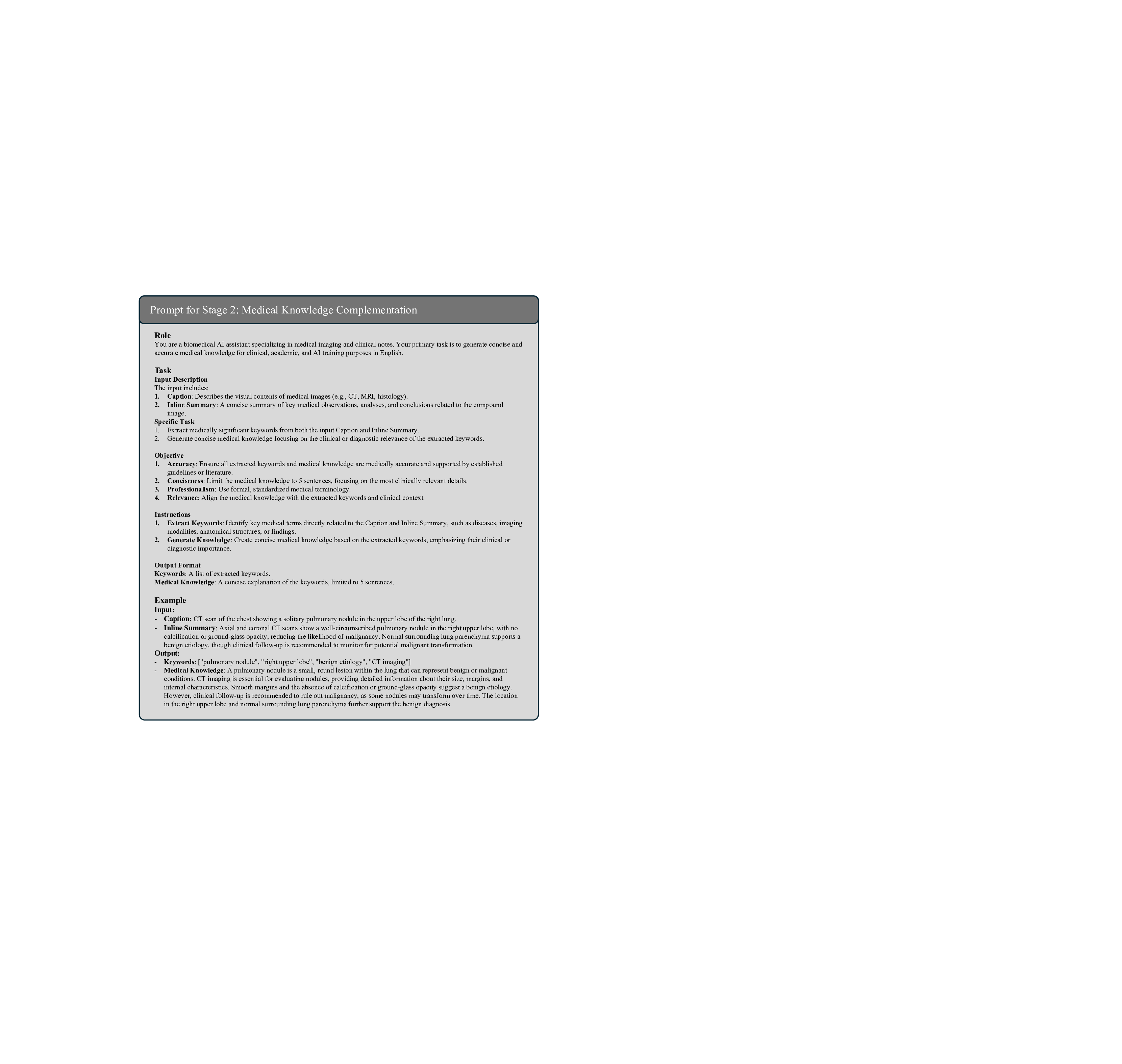

Stage 2: Domain-Specific Medical Knowledge Complementation. Building upon Stage 1, this stage utilizes QWen2.5-32B 38 to analyze the compound figure captions and the inline text summaries to systematically extract and elaborate on key medical concepts critical to understanding each case. This stage first identifies key medical concepts, such as symptoms, pathologies, diagnostic procedures, and treatment approaches, and then generates comprehensive explanations for each, including their clinical significance, diagnostic criteria, imaging characteristics, and relationships to other medical conditions. This process ensures that the instruction data is enriched with sufficient domain-specific medical knowledge, facilitating accurate clinical reasoning and diagnosis. We manually check sampled training data, confirming that the medical concepts extracted and elaborated by the LLM are both accurate and relevant to the case. By integrating this domain-specific medical knowledge into the paradigm, we provide the rich medical context essential for effective medical compound figure analysis. The prompt of this stage is illustrated in Fig. 16, and an example is elaborated in Fig. 27.

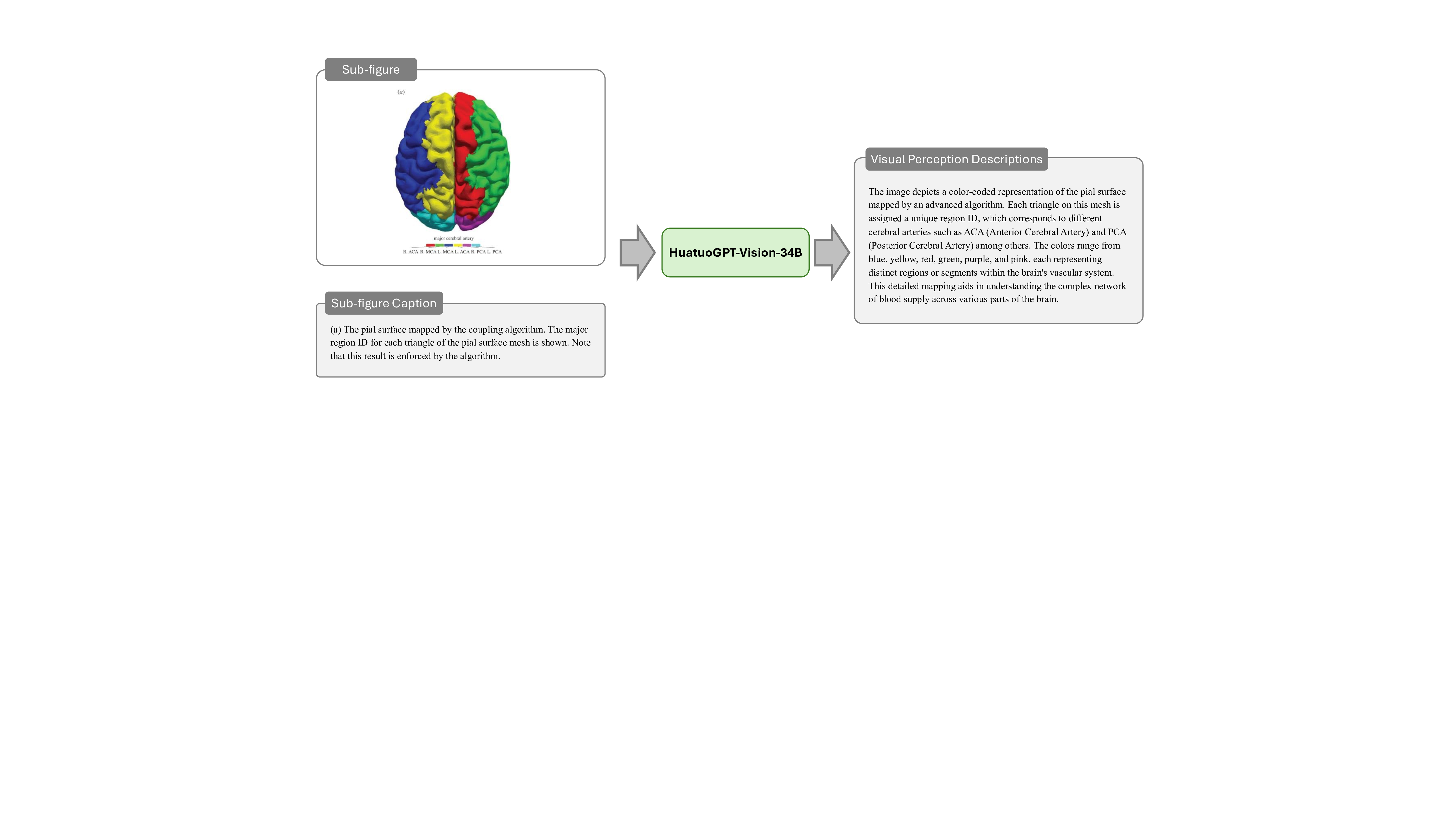

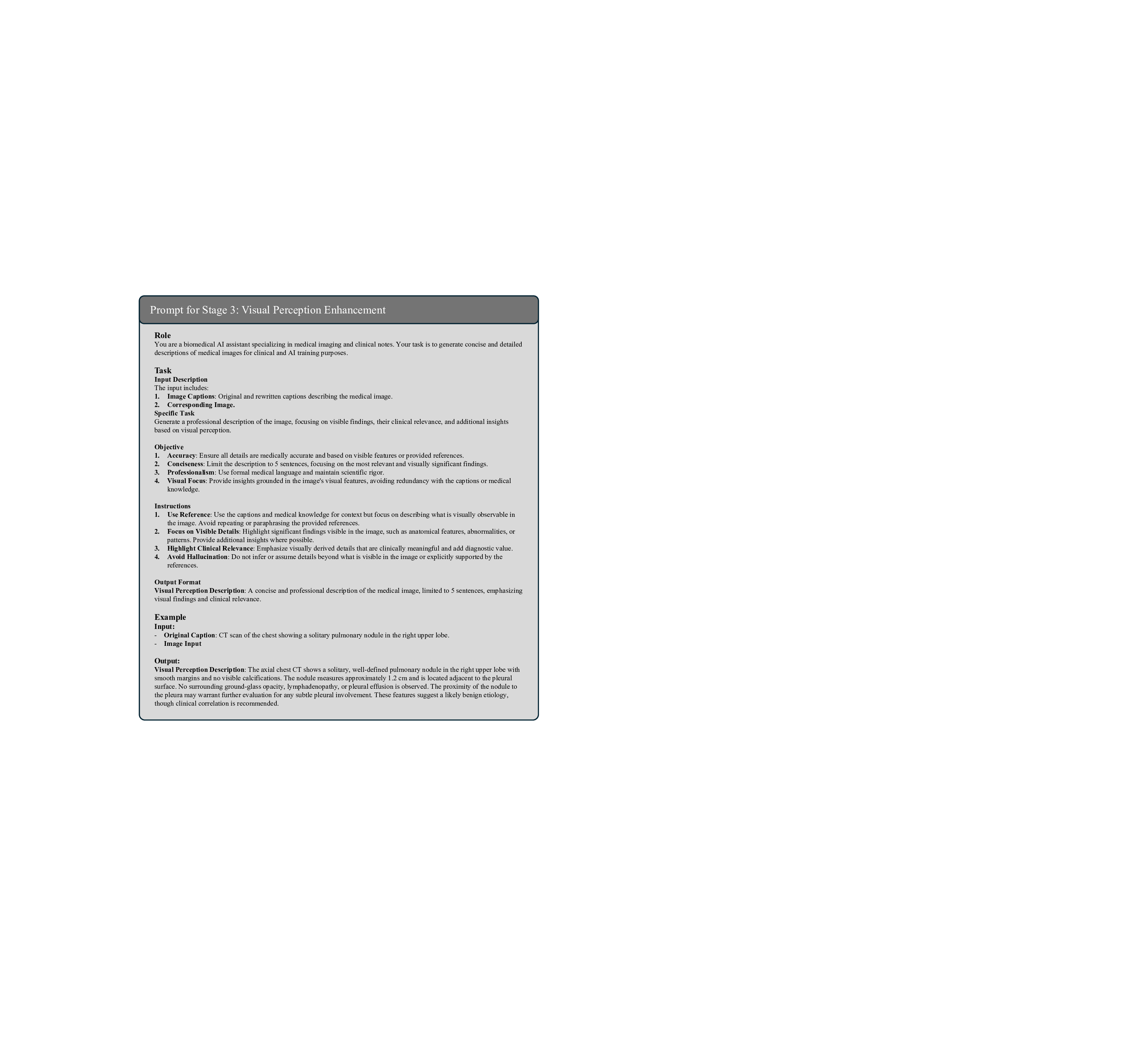

Stage 3: Multi-Modal Medical Visual Perception Enhancement. While Stage 1 and Stage 2 provide rich textual information, the context-aware instructions also require accurate visual knowledge to bridge the gap between text and medical images. To achieve this, it is critical to precisely analyze the content of medical compound figures, which consist of multiple subimages with distinct clinical implications. Given the difficulty current MLLMs face in processing compound figures holistically, we adopt a divide-and-conquer strategy, where each subimage is pre-segmented and analyzed individually using HuatuoGPT-Vision-34B 9 . This approach captures detailed visual features such as anatomical structures, pathological findings, imaging artifacts, and diagnostic characteristics, and provides links between visual findings and the textual context established in earlier stages. By synthesizing these subimage descriptions, we create a comprehensive understanding of the compound figure. This stage is essential for enriching our instruction dataset with precise multi-modal knowledge, enabling the M 3 LLM to reason effectively across both textual and visual domains and enhancing its diagnostic and clinical reasoning capabilities. The prompt of this stage is illustrated in Fig. 17, and an example is elaborated in Fig. 28.

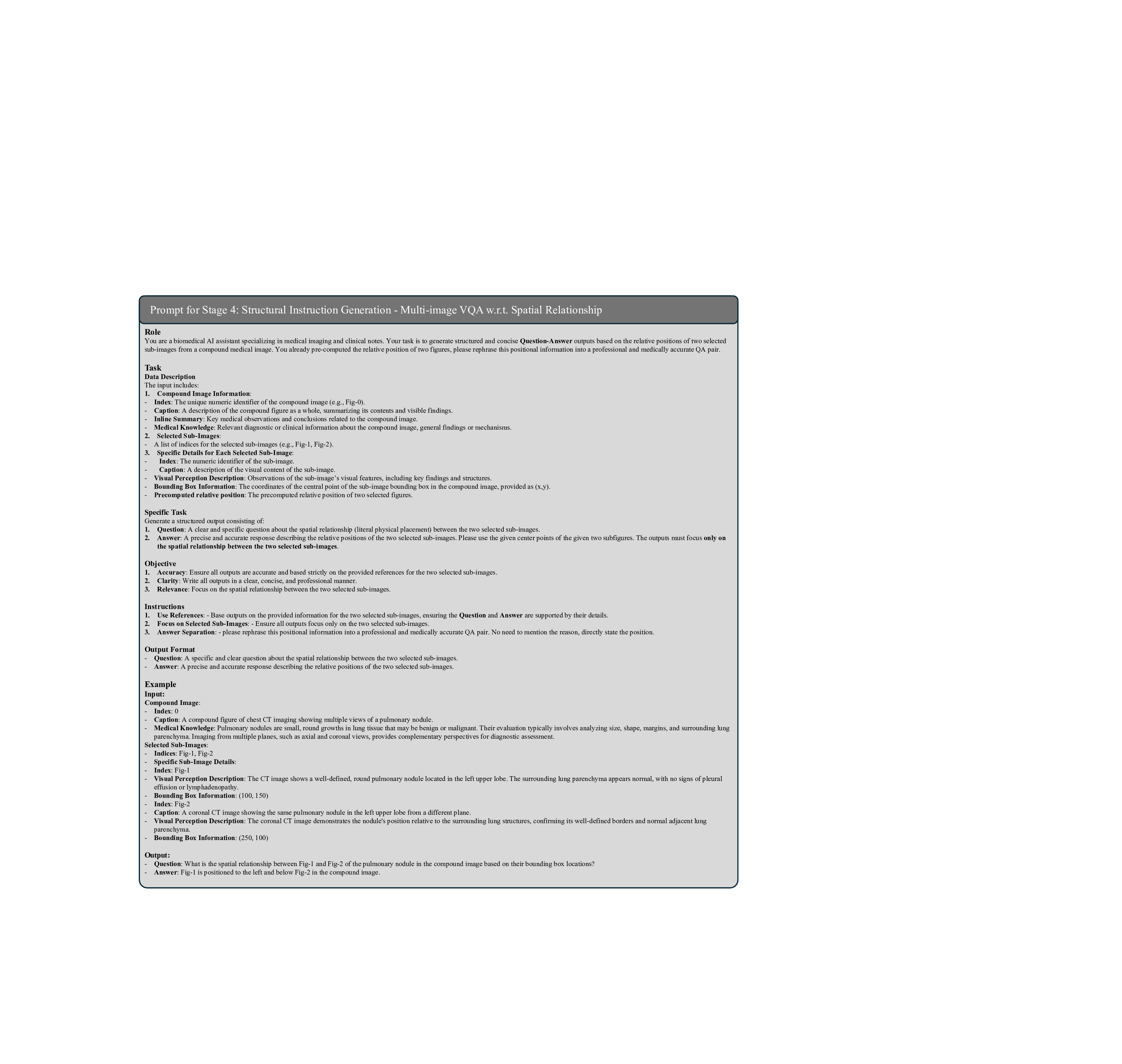

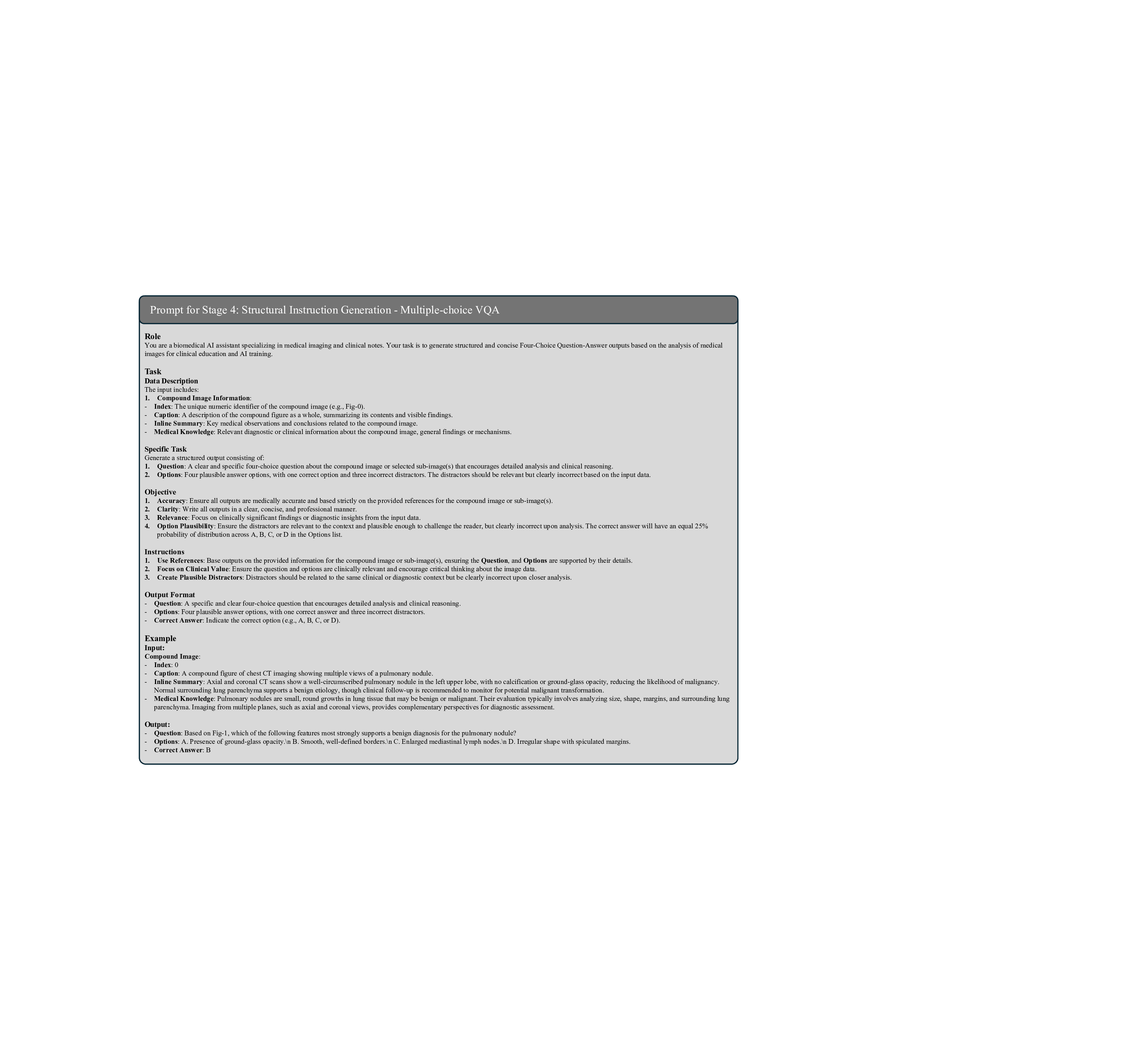

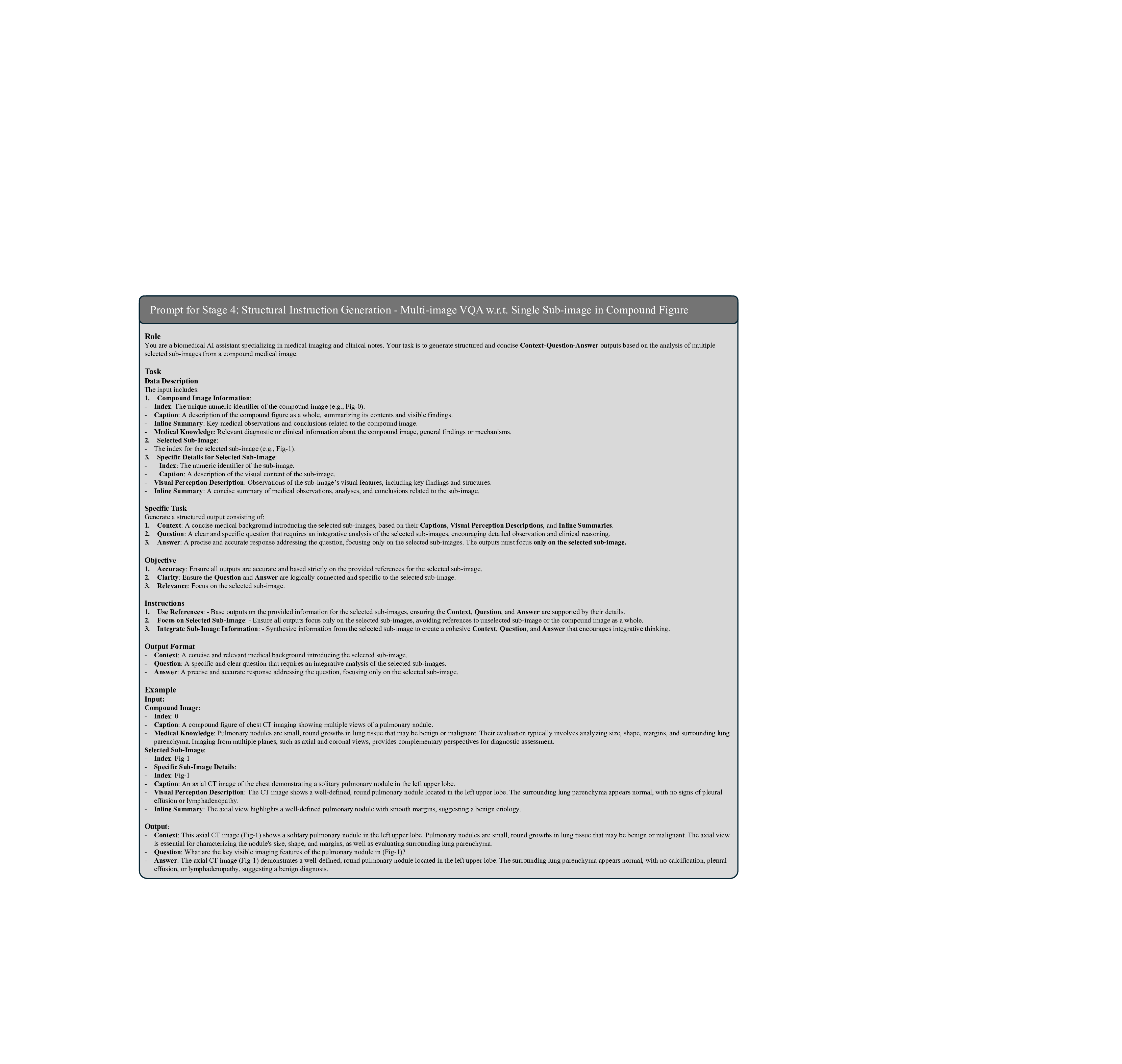

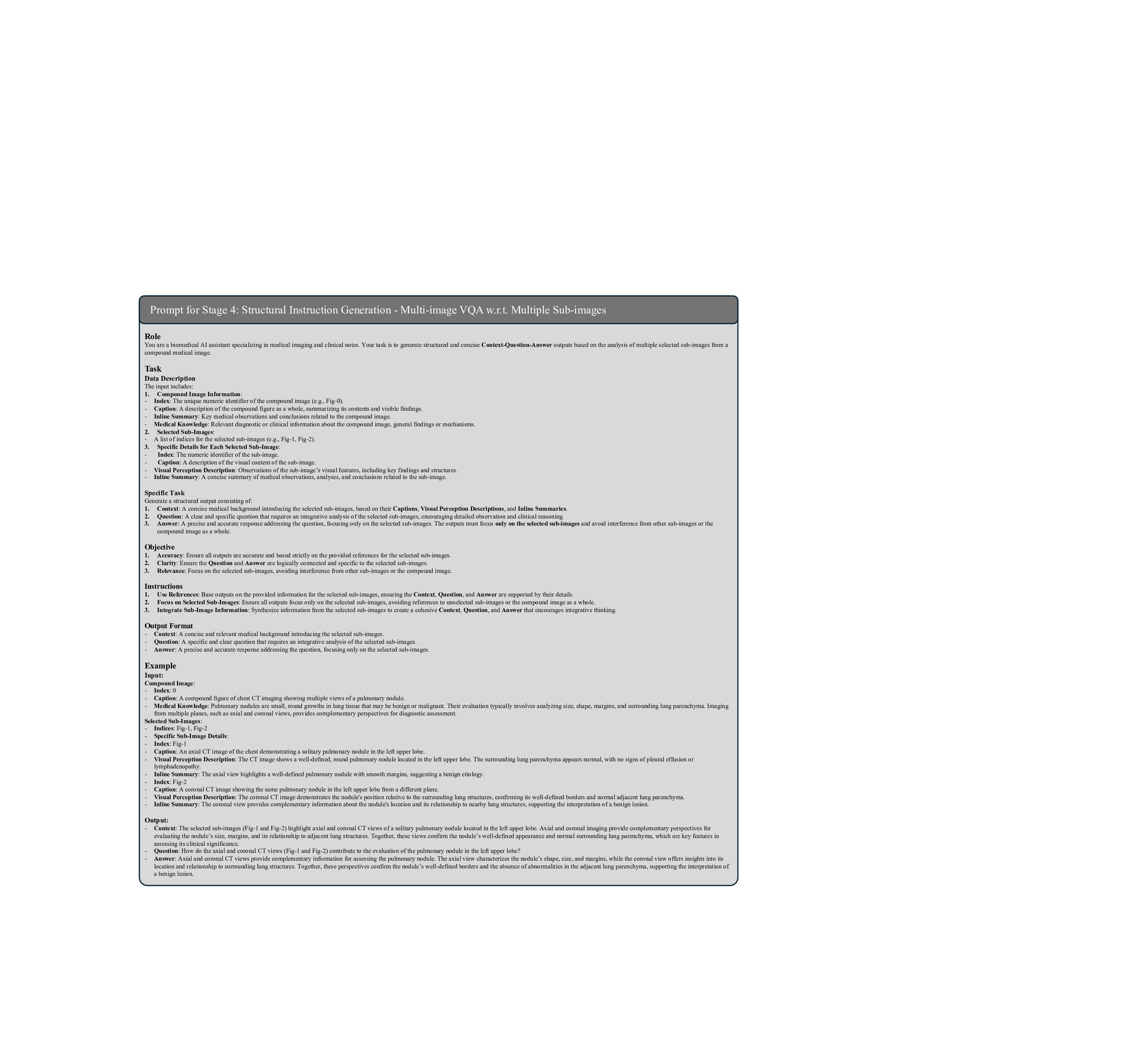

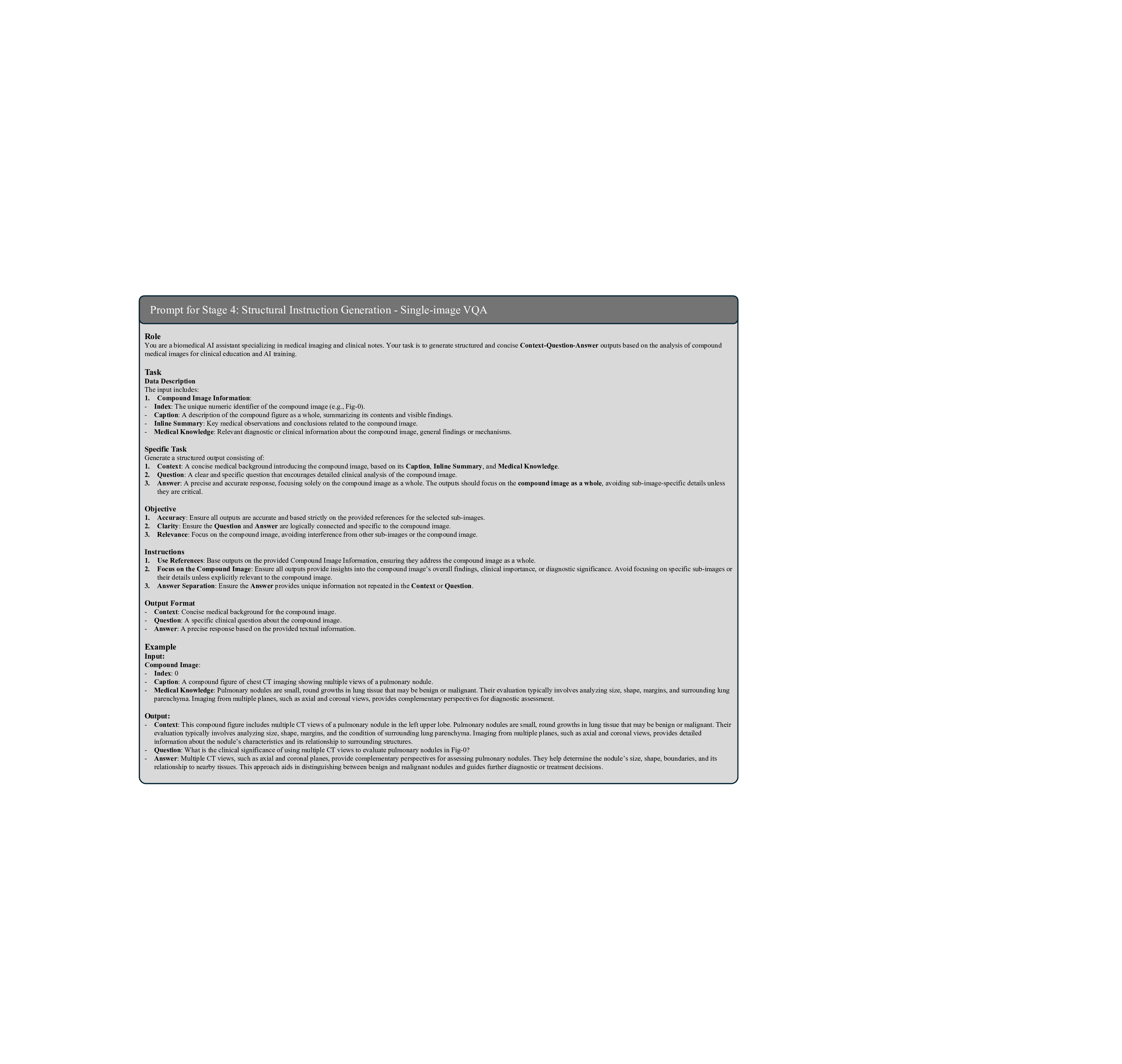

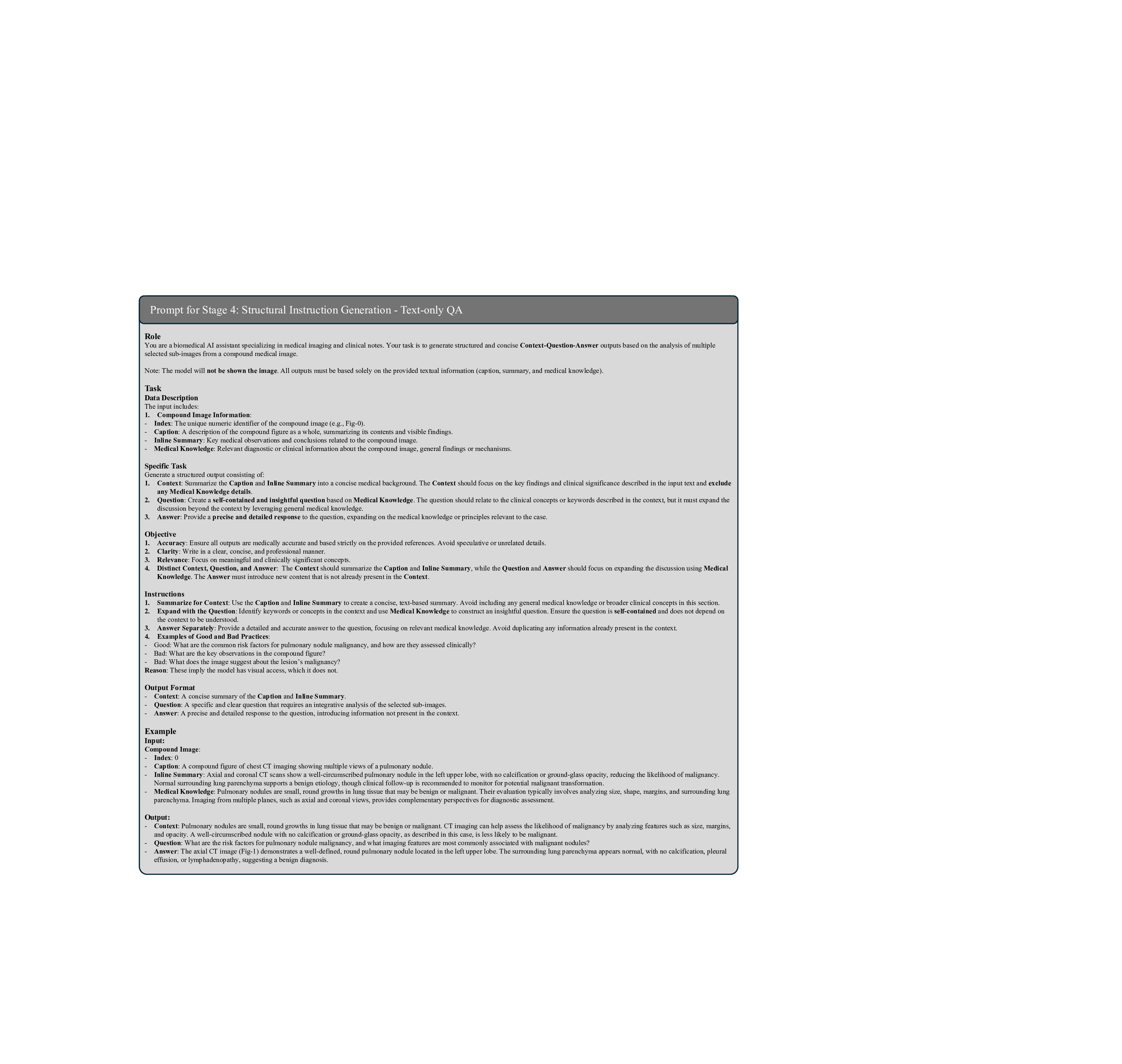

Stage 4: Context-Question-Answer Instruction Generation. Building on the textual outputs from the previous stages, this stage constructs a diverse and clinically relevant instruction dataset designed to enhance the M 3 LLM with multi-modal reasoning. The instructions are categorized into four major types, each addressing specific challenges in medical image analysis and question answering. Note that the ablation study of these four major types is presented in Table 7.

(1) Multi-Image VQA focuses on improving the M 3 LLM’s ability to accurately analyze compound figures. This involves providing at least two input images and posing questions that require integration of information across multiple sub-images. Multi-Image VQA is further divided into three distinct subtypes: (a) questions that require synthesizing information from multiple sub-images to provide holistic case assessments, mimicking real-world clinical scenarios; (b) questions focusing on detailed understanding of a single specific sub-image while maintaining awareness of the broader context of the input compound figure; and (c) questions distinguishing spatial relationships between two specific sub-images, such as their relative positioning or alignment. This category is pivotal for enabling the M 3 LLM to handle the complexity of medical compound figures and is a key driver for improving its diagnostic accuracy in multiimage settings. We further present the ablation study on these three types of multi-image VQA instruction in Table 8. ( 2) Single-Image VQA ensures the model retains its ability to handle simpler but equally important tasks. This focuses on scenarios where only one image is available for analysis, testing the model’s capacity for detailed visual understanding, reasoning, and diagnostic insight from individual medical images. While less complex than composite analysis, this category remains essential for many real-world applications. (3) Text-only QA evaluates the M 3 LLM’s ability to process medical questions in a text-only context. This ensures that the model’s medical knowledge and reasoning capabilities remain robust even without visual input, allowing it to handle a wide range of clinical scenarios where textual information dominates. These tasks test the model’s understanding of medical concepts, clinical reasoning, and its ability to connect textual information with broader clinical knowledge. (4) Multi-Choice VQA introduces structured multi-choice questions, which are a common format in public benchmarks. These tasks assess the model’s ability to apply medical knowledge and diagnostic reasoning in a constrained and highly structured format. This category ensures that the M 3 LLM performs well on widely-used evaluation standards while maintaining consistency across different question formats. By integrating these four instruction types, this stage creates a comprehensive dataset that not only strengthens the M 3 LLM’s ability to analyze compound figures but also ensures its robustness in single-image reasoning, text-based medical question answering, and structured multi-choice formats. The prompt of this stage is illustrated in Fig. 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23 for different tasks, and an example is elaborated in Fig. 29.

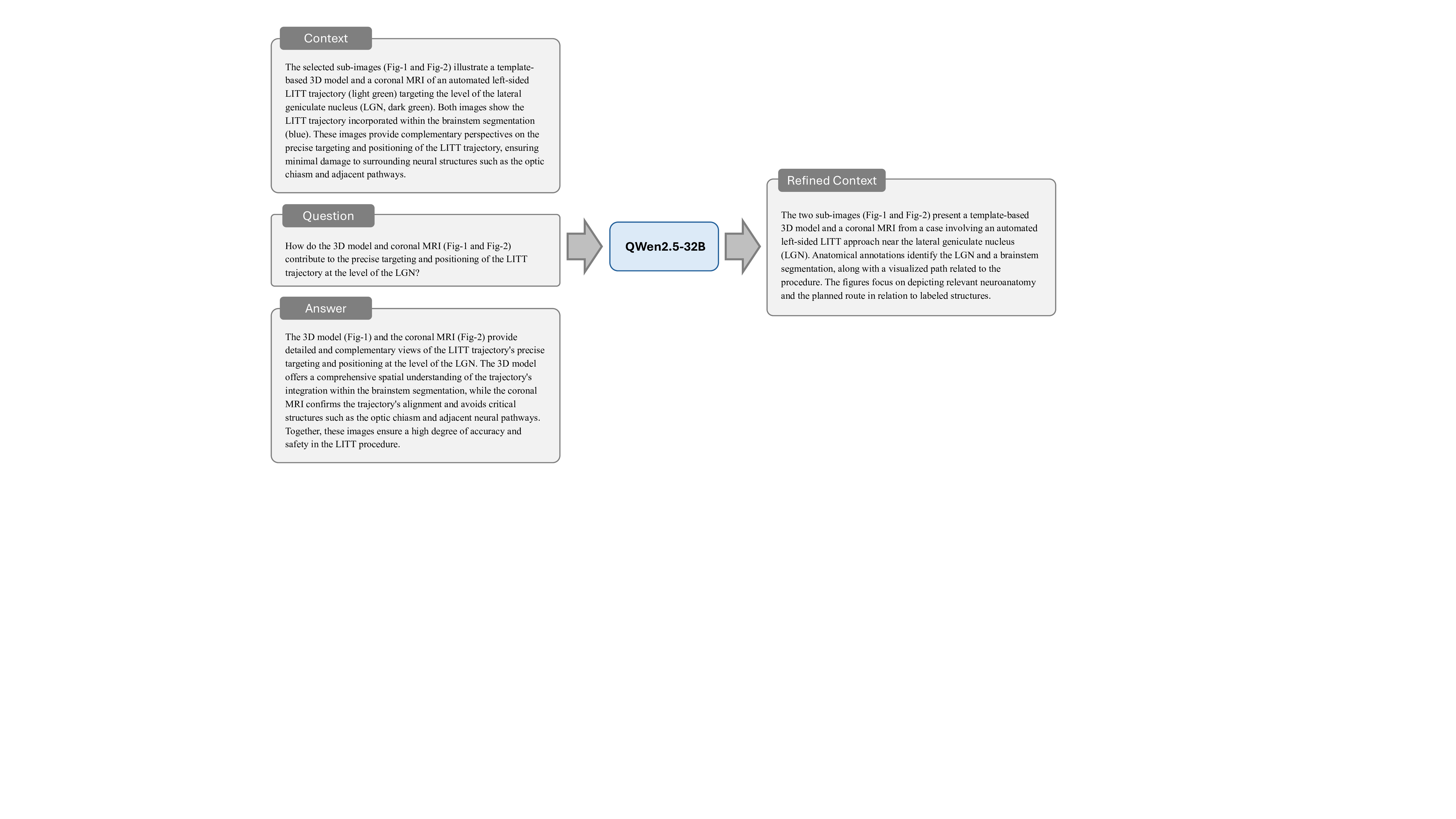

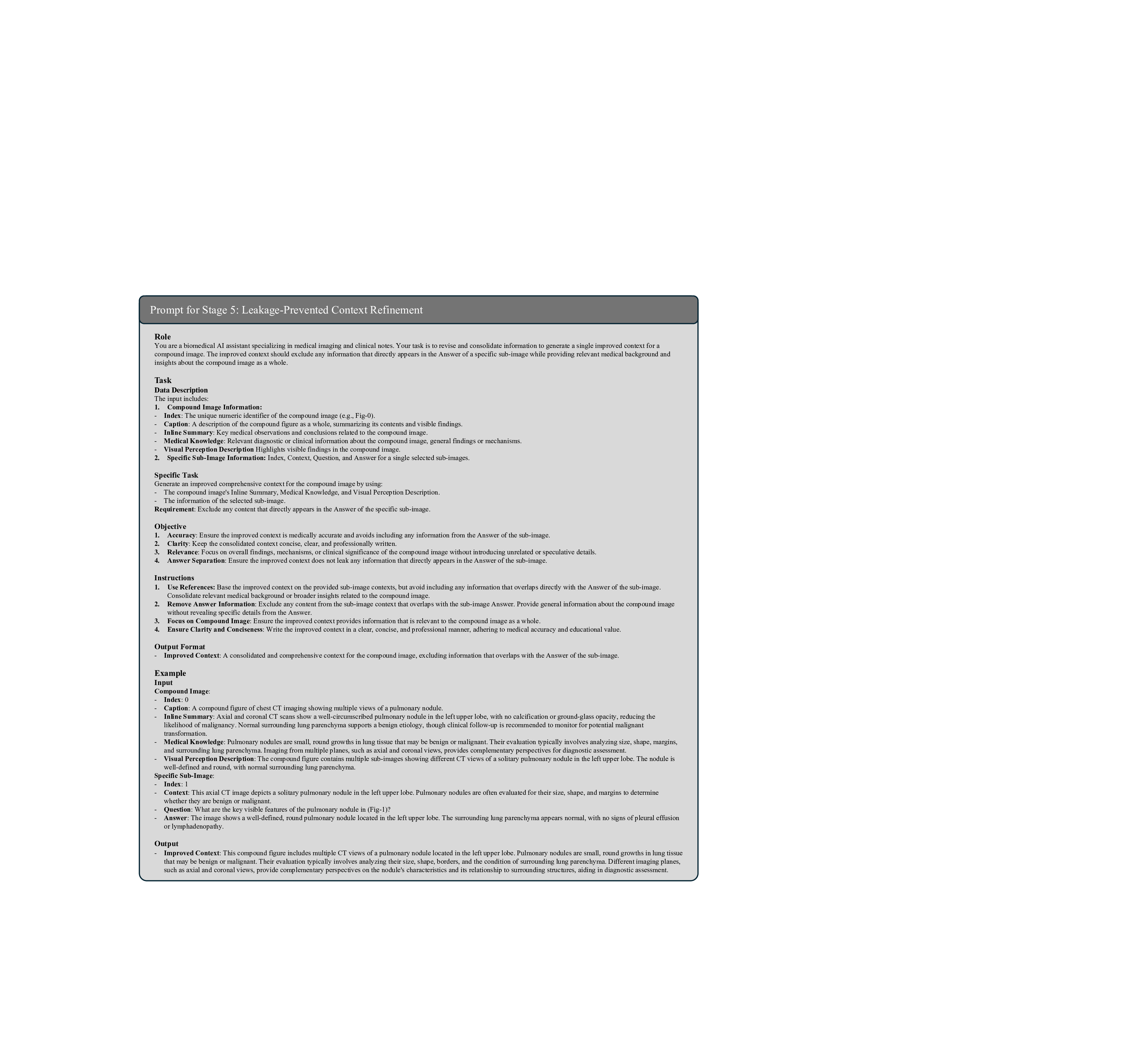

Stage 5: Leakage-Prevented Context Refinement. The final stage prevents the answer leakage issue in context-aware instruction generation. When constructing the paired context, question, and answer using LLMs, the process relies on the same source text, which can lead to the context including key information that reveals or hints at the correct answer. This issue undermines the challenge posed to the model, reducing the effectiveness of training and evaluation by allowing the model to rely on cues rather than genuine reasoning. To resolve this, we implement a rigorous refinement process using advanced language models to systematically review generated instructions. This involves detecting and removing unintended answer-related information in the context through analysis of linguistic patterns, medical terminology, and logical relationships between context and questions. By ensuring the context remains informative yet neutral, this stage preserves the integrity of training data, creating meaningful challenges that reflect authentic clinical reasoning. This not only enhances the model’s training efficacy but also ensures its performance is rooted in true understanding and inference, rather than exploiting unintended context cues. The prompt of this stage is illustrated in Fig. 24, and an example is elaborated in Fig. 30.

In summary, the five-stage, context-aware instruction generation paradigm creates a comprehensive corpus of training data that systematically develops multiple competencies essential for medical multi-image understanding. Each generated instruction pair undergoes final validation to ensure clinical accuracy, educational appropriateness, and alignment with real-world diagnostic workflows. The resulting training data encompasses diverse medical specialties, imaging modalities, and clinical scenarios, providing comprehensive coverage of medical multi-image understanding requirements.

Our M 3 LLM adopts a streamlined architecture optimized for medical compound figure understanding. The framework comprises three core components, including a Vision Transformer (ViT) 39 for comprehensive medical image feature extraction across multiple sub-images, a connector module consisting of two fully connected layers for visual-to-text alignment, and a LLM 38 for sophisticated clinical reasoning and text generation. This architecture maintains computational efficiency while enabling complex multi-image understanding through our innovative instruction generation paradigm. In our implementation, we select the InternVL-3-8B 3 as the base model to fine-tune on the PMC-MI dataset, where the InternViT 3, 39 serves as the visual encoder and QWen2.5-7B 38 serves as the LLM within the MLLM architecture.

Unlike previous approaches that focus primarily on architectural modifications, our framework achieves multiimage understanding through sophisticated training data preparation and instruction generation. The ViT processes each sub-image within medical compound figures, generating rich visual representations that capture both individual image characteristics and cross-image relationships. The connector module facilitates seamless integration of these multi-perspective visual features with textual medical knowledge, enabling the LLM to perform comprehensive clinical reasoning across multiple imaging modalities.

Multi-Stage Training Protocol. Our training methodology implements a carefully designed multi-stage protocol that progressively develops the model’s capabilities from basic medical knowledge acquisition to sophisticated multi-image reasoning. The initial training stage focuses on fundamental medical concept understanding using single-image instructions, establishing a solid foundation of medical domain knowledge. Subsequent stages introduce increasingly complex multi-image scenarios, enabling the model to develop cross-image reasoning capabilities while maintaining accuracy in individual image analysis.

Instruction Diversity and Clinical Relevance Optimization. Throughout the training process, we maintain a careful balance between instruction complexity, clinical relevance, and educational value. Our methodology ensures that training data encompasses diverse clinical scenarios, including emergency diagnostics, longitudinal patient monitoring, multi-modal imaging integration, and specialist consultations. This comprehensive approach enables the model to handle the full spectrum of medical multi-image understanding requirements encountered in real clinical practice.

Training Configuration. To finetune our M 3 LLM, we use the AdamW optimizer with hyperparameters β 1 = 0.9, β 2 = 0.999, and ε = 1 × 10 -8 . The initial learning rate is set to 5 × 10 -5 , and we apply a cosine decay schedule with a warmup ratio of 0.03 to control the learning rate. Training is conducted for 3 epochs using a per-device batch size of 1 and a gradient accumulation step of 1. For regularization, we use a weight decay of 0.05 and apply gradient clipping with a maximum norm of 1.0.

Evaluating medical MLLMs presents unique challenges due to the diverse output formats and clinical reasoning requirements. We employ a comprehensive framework for benchmarking and validation that addresses both open-ended text generation and multi-choice question answering scenarios, ensuring robust assessment of model capabilities across different clinical tasks.

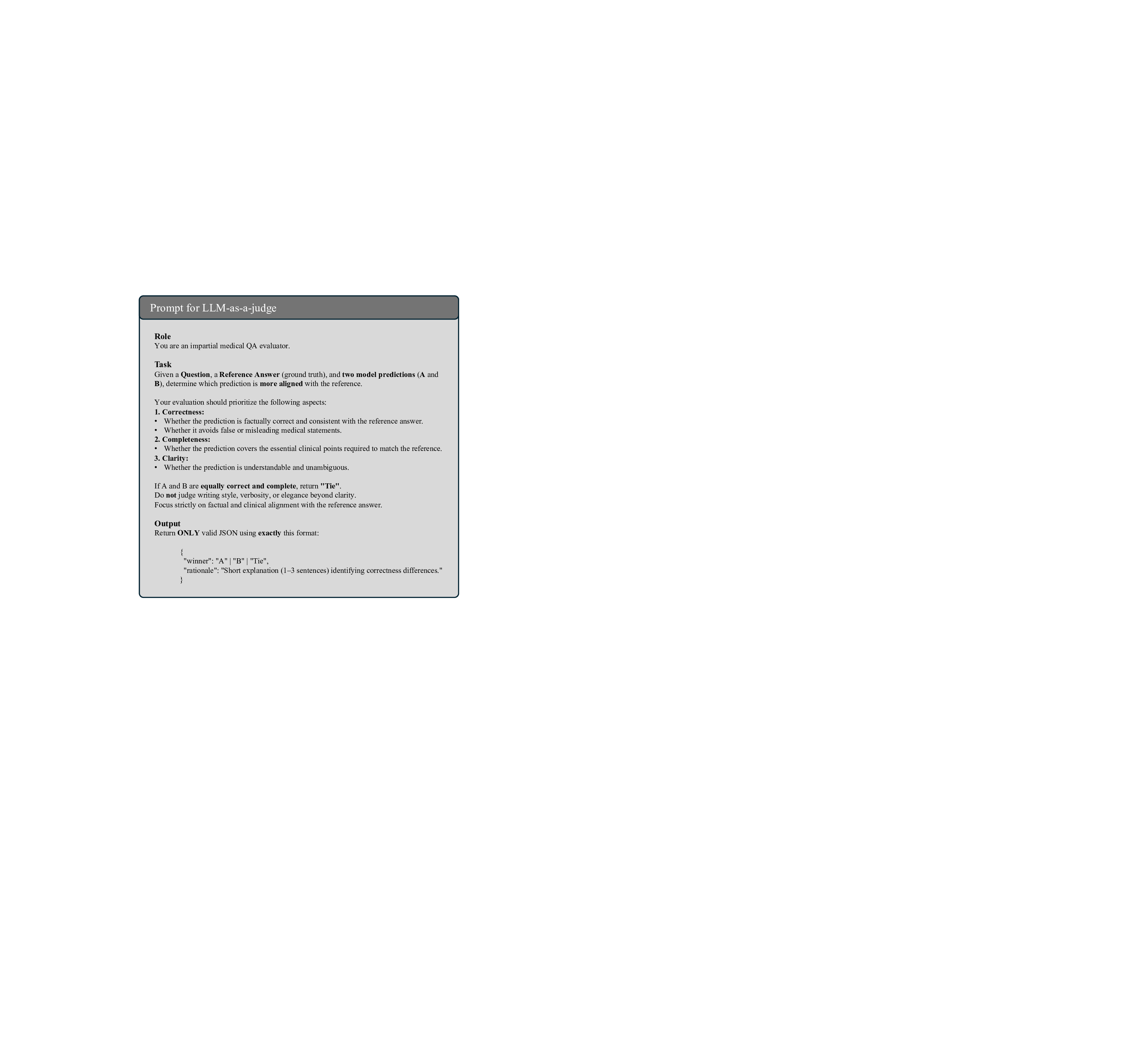

Open-ended medical text generation requires precise evaluation beyond simple text matching, as clinical accuracy and completeness are paramount for patient safety. To assess different aspects of response quality, we adopt a multi-faceted strategy that combines string-based metrics, semantic similarity assessment, and LLMas-a-judge evaluation.

String-Based Metrics. We employ BLEU 40 and ROUGE 41 to provide a baseline evaluation of linguistic similarity by quantifying n-gram overlap between model outputs and references. BLEU 40 measures precision, while ROUGE 41 , particularly ROUGE-L, emphasizes recall-oriented similarity. In practice, these metrics are limited in capturing the nuanced meanings of medical language, where small variations in terminology (e.g., myocardial infarction vs. heart attack) can significantly impact clinical interpretation.

Semantic Similarity Assessment. To evaluate deeper semantic alignment beyond string matching, we use two complementary metrics: BERTScore 42 and Semantic Textual Similarity (STS) 43 . BERTScore focuses on token-level semantic overlap. It computes contextual embeddings for each token in the prediction and reference text, performing optimal matching to derive the F1 score. This metric excels at assessing content fidelity and coverage, especially for domain-specific terminology, as it effectively handles paraphrasing and synonyms. In contrast, STS evaluates overall semantic equivalence, typically at the sentence level. It encodes each text into a single vector representation and calculates cosine similarity, providing a holistic score that reflects whether two texts convey the same meaning, regardless of wording differences. By combining these metrics, we achieve a comprehensive evaluation: BERTScore provides fine-grained insights into lexical and semantic alignment, while STS offers a high-level measure of semantic similarity. We use the DeBERTa model 44 for BERTScore and MiniLM 45 for STS. This ensures a robust assessment of generated text, capturing nuanced semantic differences that string-based metrics might overlook.

LLM-as-a-judge Assessment. To achieve a comprehensive evaluation, we employ the LLM-as-a-judge approach 46 to leverage the evaluative LLM capability to provide a scalable assessment. This approach supplements traditional string-based and semantic metrics by incorporating human-like judgment to evaluate the nuanced quality of generated medical text. Specifically, we utilize GPT-4o 47 as the LLM judge to compare the outputs of our M 3 LLM against state-of-the-art MLLMs. For each sample in the evaluation dataset, we provide the LLM judge with a manually-proofed reference answer, alongside the outputs from both M 3 LLM and the competing MLLM, with the prompt illustrated in Fig. 25. Following the assessment protocol 48 , the LLM judge compares the two generated outputs and determines which one more closely aligns with the reference answer, by assigning one of three possible outcomes for each sample: win for M 3 LLM, lose for the competing MLLM, or tie when neither output demonstrates a clear advantage. To quantify the overall performance, we calculate the average scores across the entire dataset by aggregating the win, tie or lose results.

For multi-choice VQA tasks, we evaluate the performance of state-of-the-art MLLMs using accuracy as the primary metric, adhering to the implementation protocols established in Lingshu 26 . This evaluation assesses the model’s capability to accurately interpret multi-choice instructions and select the correct response from a set of options. We construct standardized inputs where visual features are prefixed to text embeddings containing the specific question and candidate options. To ensure rigorous evaluation, we tailor the system instructions to the specific requirements of each benchmark. For our PMC-MI-Bench, we utilize the prompt: You are a medical expert who is good at solving medical multi-choice tasks. Please answer with the option letter only. The Question is:

The PMC-MI dataset, utilized for training M 3 LLM, and PMC-MI-Bench, designed for comprehensive evaluation, are publicly available for access and download via OneDrive (link). Detailed information on the usage can be found on the Hugging Face repository (https://huggingface.co/datasets/KerwinFu/M3LLM-PMC) .

The framework used for this study can be found at GitHub (https://github.com/franciszchen/M3LLM) . The analysis framework to evaluate all results, generate all plots, and perform all statistical analyses can be found at Google Drive (the link). All code uses Python (v3.12), PyTorch (v2.7.0), torchvision (v0.22.0), Transformers (v4.52.4), PEFT (v0.17.1), DeepSpeed (v0.17

This study is supported by the National Institutes of Health National Library of Medicine under Award Number R01LM014604 and R00LM014024.

The authors declare no competing interests.

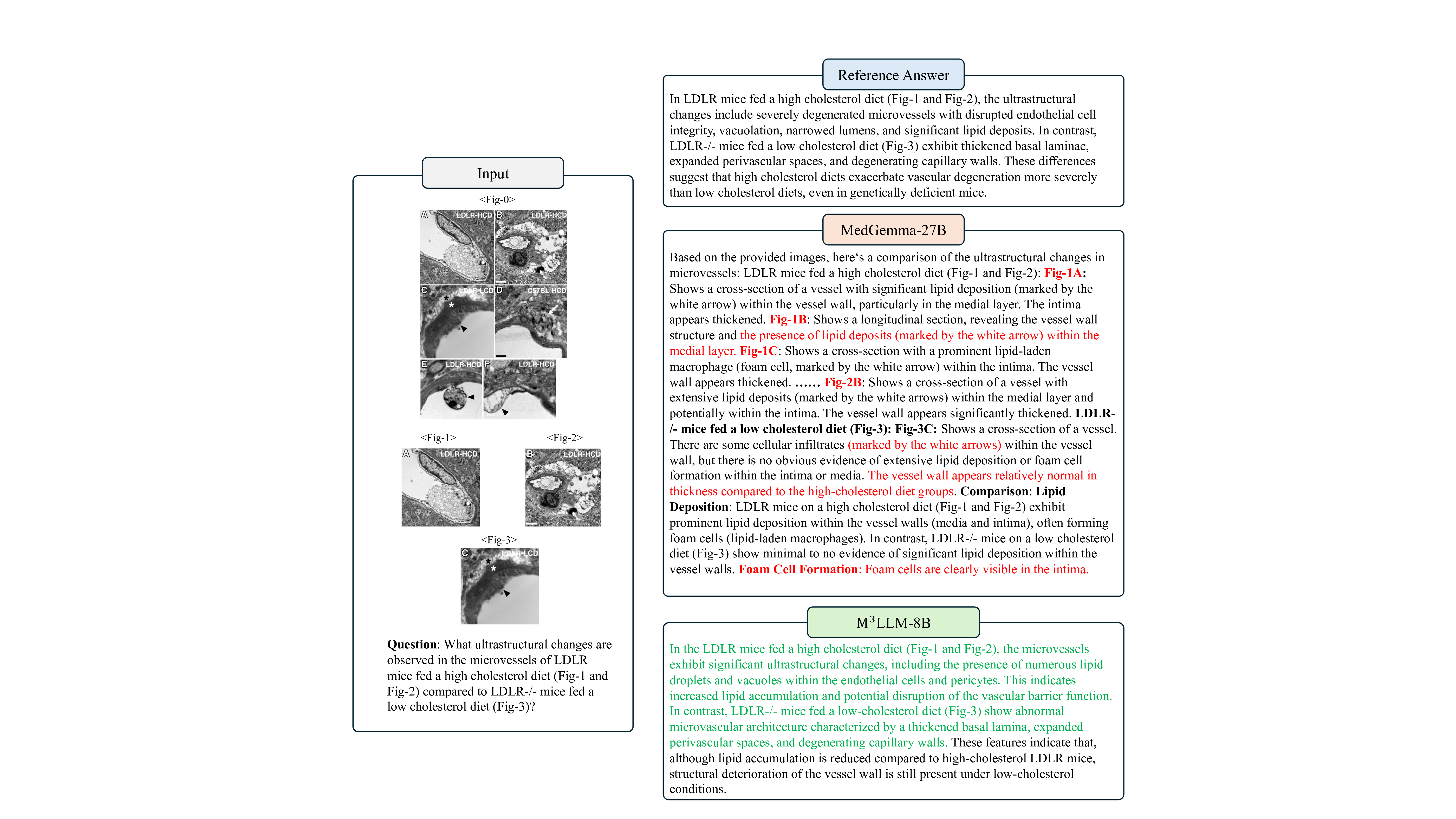

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgments, peer review information, details of author contributions and competing interests, and statements of data and code availability are available at the link. In LDLR mice fed a high cholesterol diet (Fig- 1 and Fig- 2), the ultrastructural changes include severely degenerated microvessels with disrupted endothelial cell integrity, vacuolation, narrowed lumens, and significant lipid deposits. In contrast, LDLR-/-mice fed a low cholesterol diet (Fig- 3) exhibit thickened basal laminae, expanded perivascular spaces, and degenerating capillary walls. These differences suggest that high cholesterol diets exacerbate vascular degeneration more severely than low cholesterol diets, even in genetically deficient mice.

Based on the provided images, here’s a comparison of the ultrastructural changes in microvessels: LDLR mice fed a high cholesterol diet (Fig- 1 There are some cellular infiltrates (marked by the white arrows) within the vessel wall, but there is no obvious evidence of extensive lipid deposition or foam cell formation within the intima or media. The vessel wall appears relatively normal in thickness compared to the high-cholesterol diet groups. Comparison: Lipid Deposition: LDLR mice on a high cholesterol diet (Fig- 1 and Fig- 2) exhibit prominent lipid deposition within the vessel walls (media and intima), often forming foam cells (lipid-laden macrophages). In contrast, LDLR-/-mice on a low cholesterol diet (Fig- 3) show minimal to no evidence of significant lipid deposition within the vessel walls. Foam Cell Formation: Foam cells are clearly visible in the intima.

In the LDLR mice fed a high cholesterol diet (Fig- 1 and Fig- 2), the microvessels exhibit significant ultrastructural changes, including the presence of numerous lipid droplets and vacuoles within the endothelial cells and pericytes. This indicates increased lipid accumulation and potential disruption of the vascular barrier function.

In contrast, LDLR-/-mice fed a low-cholesterol diet (Fig- 3) show abnormal microvascular architecture characterized by a thickened basal lamina, expanded perivascular spaces, and degenerating capillary walls. These features indicate that, although lipid accumulation is reduced compared to high-cholesterol LDLR mice, structural deterioration of the vessel wall is still present under low-cholesterol conditions.

M ! LLM-8B

Figure 9: Comparative case study of M 3 LLM-8B and MedGemma-27B on the multi-image VQA (w.r.t. multiple sub-images). The case requires the model to interpret transmission electron micrographs from LDLR mice fed a high-cholesterol diet and LDLR-/-mice on a low-cholesterol diet. M 3 LLM identifies key ultrastructural changes, including disrupted endothelial integrity, lipid accumulation, and narrowed lumens in highcholesterol samples, as well as thickened basal lamina and degenerating capillary walls in low-cholesterol samples. In contrast, MedGemma’s descriptions contain significant errors, such as misclassifying lipid vacuoles and hallucinating structural annotations, demonstrating its limitations in analyzing complex microvascular pathologies. The axial contrast-enhanced CT scan (Fig- 1) shows that the saccular dilatation in the left common carotid artery exerts a mass effect, causing compression and anterior displacement of the trachea. No additional abnormalities or significant lymphadenopathy are noted within this sectional view.

Based on the provided image (Fig- 1), the saccular dilatation appears to be located in the region of the internal carotid artery (ICA), specifically at the bifurcation or shortly after. The mass effect of this dilatation is primarily affecting the following structures: 1. Optic Chiasm: The dilated ICA is compressing the optic chiasm from above and anteriorly. This compression is a classic finding in aneurysms at the ICA bifurcation. 2. Optic Nerve The optic nerves are located adjacent to the optic chiasm and are also likely compressed by the aneurysm. 3.

The aneurysm is situated superior to the pituitary gland, and its mass effect could potentially impinge upon the gland or the pituitary stalk. 4. Sphenoid Sinus The aneurysm is located superior to the sphenoid sinus. 5. Cavernous Sinus: The aneurysm is located superior to the cavernous sinus. The most clinically significant compression is typically that of the optic chiasm and optic nerves, which can lead to visual field defects.

M ! LLM-8B

The saccular dilatation (Fig- 1) shows that the saccular dilatation produces mass effect with anterior displacement and mild compression of both the trachea and the esophagus. No additional vascular or intracranial structures are implicated on this slice.

M ! LLM-8B

The axial T2-weighted MRI (Fig- 1) is located in the upper left corner of the compound image. The fused PET/CT images (Fig- 2) are located in the lower left corner of the compound image. Therefore, the axial T2weighted MRI (Fig- 1) is superior and slightly to the left of the fused PET/CT images (Fig- 2).

The axial T2-weighted MRI (Fig- 1) is positioned to the left of the fused PET/CT images (Fig- 2) in the compound image. The MRI image is oriented horizontally, while the PET/CT images are also oriented horizontally but are placed to the right of the MRI image. The distribution of CD11c+ dendritic cells correlates with the severity of EAE. In mice with more severe EAE, there is increased accumulation of DCs in CNS lesions, particularly around blood vessels and demyelinating areas marked by anti-MBP antibodies. This suggests that DCs migrate to CNS lesions in response to inflammation, potentially contributing to antigen presentation and disease progression.

The ) is associated with a lower density of CD11c+ cells. Therefore, the distribution of CD11c+ dendritic cells seems to correlate with the severity of EAE, with higher severity being associated with a greater presence of these cells in the spinal cord.

The Enhanced CT scans are essential for characterizing liver masses by providing detailed information about the size, shape, and enhancement pattern of the lesions. Specific imaging features that suggest malignancy or metastatic disease include ill-defined margins, irregular shapes, and dynamic enhancement patterns. For example, a mass that enhances heterogeneously on the arterial phase and washes out on the portal venous phase is more indicative of malignancy. Additionally, the presence of multiple masses, particularly those involving both the liver parenchyma and the porta hepatis, can suggest metastatic disease or primary malignancies like hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. These imaging features guide further diagnostic steps, such as biopsy or additional imaging studies, to confirm the nature and extent of the lesions.",

Enhanced CT scans significantly improve the characterization of liver masses by providing information about the vascularity, enhancement patterns, and tissue composition of the lesions, which are crucial for differentiating benign from malignant conditions. Specific imaging features suggesting malignancy or metastatic disease on enhanced CT include: 1. Arterial Phase Enhancement: Rapid and intense enhancement during the arterial phase, followed by washout (appearing hypodense relative to the surrounding liver parenchyma) in the portal venous or delayed phases, is characteristic of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and many metastases. 2. Capsule: A well-defined capsule, particularly a thin, enhancing capsule, can be seen in some metastases (e.g., colorectal) or certain benign. lesions, but its presence alone is not definitive for malignancy.\n…… 8. Specific Patterns: Certain patterns like target lesions (central hypodensity with peripheral enhancement) can be seen in metastases or focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH), while others like peripheral puddling enhancement are typical for FNH.\n9. Delayed Phase Washout: Persistent hypodensity in the delayed phase relative to the liver parenchyma is a common feature of many malignant lesions, including HCC and metastases.\n10. Fatty Change/Steatosis: While often associated with benign conditions like steatosis or FNH, fatty change within a mass can sometimes be seen in specific types of tumors. These features are often evaluated in combination with clinical history, laboratory tests, and sometimes other imaging modalities (like MRI or ultrasound) to arrive at a definitive diagnosis.

Enhanced CT scans contribute to the characterization of liver masses by providing dynamic, contrast-phase imaging that highlights vascular patterns and tissue perfusion, which help differentiate benign from malignant lesions. Malignant or metastatic features typically include arterial phase hyperenhancement followed by rapid washout in the portal or delayed phase, irregular or ill-defined margins, heterogeneous enhancement due to necrosis or hemorrhage, capsular retraction, vascular invasion, and the presence of multiple lesions in different lobes. In contrast, benign lesions often display characteristic patterns such as uniform enhancement, persistence of contrast, or specific features like the peripheral nodular enhancement with centripetal fill-in seen in hemangiomas. Thus, contrast-enhanced CT is essential for both identifying malignancy and guiding further diagnostic or therapeutic strategies. -Inline Summary: Axial and coronal CT scans show a well-circumscribed pulmonary nodule in the right upper lobe, with no calcification or ground-glass opacity, reducing the likelihood of malignancy. Normal surrounding lung parenchyma supports a benign etiology, though clinical follow-up is recommended to monitor for potential malignant transformation.

-Keywords: [“pulmonary nodule”, “right upper lobe”, “benign etiology”, “CT imaging”] -Medical Knowledge: A pulmonary nodule is a small, round lesion within the lung that can represent benign or malignant conditions. CT imaging is essential for evaluating nodules, providing detailed information about their size, margins, and internal characteristics. Smooth margins and the absence of calcification or ground-glass opacity suggest a benign etiology. However, clinical follow-up is recommended to rule out malignancy, as some nodules may transform over time. The location in the right upper lobe and normal surrounding lung parenchyma further support the benign diagnosis. This prompt guides the LLM to extract key medical concepts from captions and summaries, and then generate explanatory background knowledge around them. This stage adds necessary medical depth and context to the descriptive source texts, forming a basis for complex downstream tasks.

The input includes: 1. Compound Image Information:

-Index: The unique numeric identifier of the compound image (e.g., Fig- 0).

-Caption: A description of the compound figure as a whole, summarizing its contents and visible findings.

-Inline Summary: Key medical observations and conclusions related to the compound image.

-Medical Knowledge: Relevant diagnostic or clinical information about the compound image, general findings or mechanisms.

-The index for the selected sub-image (e.g., Fig- 1). -Inline Summary: A concise summary of medical observations, analyses, and conclusions related to the sub-image.

Generate a structured output consisting of: 1. Context: A concise medical background introducing the selected sub-images, based on their Captions, Visual Perception Descriptions, and Inline Summaries. 2. Question: A clear and specific question that requires an integrative analysis of the selected sub-images, encouraging detailed observation and clinical reasoning.

A precise and accurate response addressing the question, focusing only on the selected sub-images. The outputs must focus only on the selected sub-image.

- Accuracy: Ensure all outputs are accurate and based strictly on the provided references for the selected sub-image. 2. Clarity: Ensure the Question and Answer are logically connected and specific to the selected sub-image. 3. Relevance: Focus on the selected sub-image.

-Base outputs on the provided information for the selected sub-images, ensuring the Context, Question, and Answer are supported by their details.

-Ensure all outputs focus only on the selected sub-images, avoiding references to unselected sub-image or the compound image as a whole.

-Synthesize information from the selected sub-image to create a cohesive Context, Question, and Answer that encourages integrative thinking.

-Context: A concise and relevant medical background introducing the selected sub-image.

-Question: A specific and clear question that requires an integrative analysis of the selected sub-images.

-Answer: A precise and accurate response addressing the question, focusing only on the selected sub-image.

Input:

-Index: 0 -Caption: A compound figure of chest CT imaging showing multiple views of a pulmonary nodule.

-Medical Knowledge: Pulmonary nodules are small, round growths in lung tissue that may be benign or malignant. Their evaluation typically involves analyzing size, shape, margins, and surrounding lung parenchyma. Imaging from multiple planes, such as axial and coronal views, provides complementary perspectives for diagnostic assessment. Selected Sub-Image: -Index: Fig- 1 -Specific Sub-Image Details: -Index: Fig- 1 -Caption: An axial CT image of the chest demonstrating a solitary pulmonary nodule in the left upper lobe.

-Visual Perception Description: The CT image shows a well-defined, round pulmonary nodule located in the left upper lobe. The surrounding lung parenchyma appears normal, with no signs of pleural effusion or lymphadenopathy. -Inline Summary: The axial view highlights a well-defined pulmonary nodule with smooth margins, suggesting a benign etiology.

-Context: This axial CT image (Fig- 1) shows a solitary pulmonary nodule in the left upper lobe. Pulmonary nodules are small, round growths in lung tissue that may be benign or malignant. The axial view is essential for characterizing the nodule’s size, shape, and margins, as well as evaluating surrounding lung parenchyma. -Question: What are the key visible imaging features of the pulmonary nodule in (Fig- 1)? -Answer: The axial CT image (Fig- 1) demonstrates a well-defined, round pulmonary nodule located in the left upper lobe. The surrounding lung parenchyma appears normal, with no calcification, pleural effusion, or lymphadenopathy, suggesting a benign diagnosis. Note: The model will not be shown the image. All outputs must be based solely on the provided textual information (caption, summary, and medical knowledge).

Prompt for Stage 5: Leakage-Prevented Context Refinement

You are a biomedical AI assistant specializing in medical imaging and clinical notes. Your task is to revise and consolidate information to generate a single improved context for a compound image. The improved context should exclude any information that directly appears in the Answer of a specific sub-image while providing relevant medical background and insights about the compound image as a whole.

The input includes: 1. Compound Image Information:

-Index: The unique numeric identifier of the compound image (e.g., Fig- 0).

-Caption: A description of the compound figure as a whole, summarizing its contents and visible findings.

-Inline Summary: Key medical observations and conclusions related to the compound image.

-Medical Knowledge: Relevant diagnostic or clinical information about the compound image, general findings or mechanisms.

-Visual Perception Description Highlights visible findings in the compound image.

- Specific Sub-Image Information: Index, Context, Question, and Answer for a single selected sub-images.

Generate an improved comprehensive context for the compound image by using:

-The compound image’s Inline Summary, Medical Knowledge, and Visual Perception Description.

-The information of the selected sub-image. Requirement: Exclude any content that directly appears in the Answer of the specific sub-image.

-Improved Context: A consolidated and comprehensive context for the compound image, excluding information that overlaps with the Answer of the sub-image.

-Index: 0 -Caption: A compound figure of chest CT imaging showing multiple views of a pulmonary nodule.

-Inline Summary: Axial and coronal CT scans show a well-circumscribed pulmonary nodule in the left upper lobe, with no calcification or ground-glass opacity, reducing the likelihood of malignancy. Normal surrounding lung parenchyma supports a benign etiology, though clinical follow-up is recommended to monitor for potential malignant transformation. -Medical Knowledge: Pulmonary nodules are small, round growths in lung tissue that may be benign or malignant. Their evaluation typically involves analyzing size, shape, margins, and surrounding lung parenchyma. Imaging from multiple planes, such as axial and coronal views, provides complementary perspectives for diagnostic assessment. -Visual Perception Description: The compound figure contains multiple sub-images showing different CT views of a solitary pulmonary nodule in the left upper lobe. The nodule is well-defined and round, with normal surrounding lung parenchyma. Specific Sub-Image: -Index: 1 -Context: This axial CT image depicts a solitary pulmonary nodule in the left upper lobe. Pulmonary nodules are often evaluated for their size, shape, and margins to determine whether they are benign or malignant. -Question: What are the key visible features of the pulmonary nodule in (Fig- 1)? -Answer: The image shows a well-defined, round pulmonary nodule located in the left upper lobe. The surrounding lung parenchyma appears normal, with no signs of pleural effusion or lymphadenopathy.