MimiCAT: Mimic with Correspondence-Aware Cascade-Transformer for Category-Free 3D Pose Transfer

📝 Original Info

- Title: MimiCAT: Mimic with Correspondence-Aware Cascade-Transformer for Category-Free 3D Pose Transfer

- ArXiv ID: 2511.18370

- Date: 2025-11-23

- Authors: Zenghao Chai, Chen Tang, Yongkang Wong, Xulei Yang, Mohan Kankanhalli

📝 Abstract

3D pose transfer aims to transfer the pose-style of a source mesh to a target character while preserving both the target's geometry and the source's pose characteristic. Existing methods are largely restricted to characters with similar structures and fail to generalize to category-free settings (e.g., transferring a humanoid's pose to a quadruped). The key challenge lies in the structural and transformation diversity inherent in distinct character types, which often leads to mismatched regions and poor transfer quality. To address these issues, we first construct a million-scale pose dataset across hundreds of distinct characters. We further propose MimiCAT, a cascade-transformer model designed for category-free 3D pose transfer. Instead of relying on strict one-to-one correspondence mappings, Mimi-CAT leverages semantic keypoint labels to learn a novel soft correspondence that enables flexible many-to-many matching across characters. The pose transfer is then formulated as a conditional generation process, in which the source transformations are first projected onto the target through soft correspondence matching and subsequently refined using shape-conditioned representations. Extensive qualitative and quantitative experiments demonstrate that Mimi-CAT transfers plausible poses across different characters, significantly outperforming prior methods that are limited to narrow category transfer (e.g., humanoid-to-humanoid).📄 Full Content

Category-free 3D Pose Transfer becomes highly desirable. The objective is to apply a reference pose from a source character to a target character while simultaneously preserving the unique characteristics of the target and the fidelity of the source pose. However, transferring poses across different characters is highly non-trivial. Compared to humanoids, many characters possess distinct body structures and proportions, making reproducing similar behaviors challenging. The task is often dependent on experienced 3D artists, making it both expensive and slow. While early works [8,9,60,61] have shown promising results for pose transfer between characters with similar morphology (e.g., from a human to a robot) by learning keypoint-or vertex-level correspondences, they struggle to generalize across arbitrary character categories (e.g., transferring bird poses to humanoids). A key limitation is their reliance on one-to-one mappings to establish correspondences. Such mappings are often inadequate for modeling complex many-to-many relationships-for example, shall four limbs of a humanoid correspond to the two wings of a bird? This mismatch leads to significant transfer artifacts when dealing with characters of fundamentally different topologies. Moreover, existing approaches typically learn pose priors from human motion datasets [1,21,37,64], making them prone to out-of-distribution failures (e.g., unnatural artifacts). For instance, transferring human poses to birds can yield degraded results due to the lack of knowledge about bird-specific motion patterns. These challenges arise because different characters exhibit highly diverse and complex structures (e.g., keypoints, skinning weights, and topologies), and their keypoints exhibit distinct rotation patterns conditioned on each character’s morphology and rigging design. These factors collectively make cross-category 3D pose transfer a highly challenging problem. To address the above challenges, we first construct a large-scale pose dataset containing ∼4.4 million pose samples across hundreds of diverse character categories (see Tab. 1). Using this dataset, we pretrain a shape-aware distribution model that captures the joint distribution of keypointwise rotations [40,50,70] for characters with varying skeletal structures. This pretrained distribution model serves as a regularization for pose transfer and prevents degenerate transformations. Following this, we introduce MimiCAT, a transformer-based [59] framework for category-free 3D pose transfer. MimiCAT features two cascaded transformer modules, which undergo two-stage training. In the first stage, a correspondence transformer learns a similarity matrix between two sets of keypoints with varying lengths. Rather than relying on rigid one-to-one mappings, we incorporate semantic skeleton labels (i.e., keypoint names) to establish flexible many-to-many soft correspondences between structurally distinct characters. In the second stage, the estimated soft correspondences map initial transformations from the source to the target. Conditioned on pretrained shape encoders [81], we formulate pose transfer as a conditional generation problem and employ a pose transfer transformer to generate realistic target poses. This stage employs a self-supervised cycle-consistency loss, eliminating the need for paired cross-category ground-truth.

To evaluate the transfer quality for category-free pose transfer, we establish a new benchmark based on crosstransfer cycle consistency. In addition, following previous works [31,60,61], we also include humanoid-tohumanoid evaluations for comprehensive comparisons. We conduct both qualitative and quantitative experiments to demonstrate that MimiCAT can effectively transfer poses across 3D characters with significantly different morphologies, outperforming existing methods that are restricted to structual-similar characters. Once trained, our model seamlessly supports several downstream tasks, such as text-toany-character motion generation.

In summary, our main contributions are as follows: 1. We extend the 3D pose transfer task to a broader and more challenging setting, namely category-free pose transfer, and construct a novel benchmark based on cycle-consistency evaluation to assess transfer quality. 2. We build a large-scale dataset containing millions of character poses across diverse categories, which enables learning 3D pose transfer models under more practical and generalizable conditions. 3. We design a novel cascade-transformer architecture, MimiCAT, that learns many-to-many soft correspondences between keypoints, enabling effective 3D pose transfer across characters with distinct structures. 4. We achieve state-of-the-art pose transfer quality and demonstrate the strong potential of our framework for downstream applications. Code and dataset will be made publicly available for research purposes.

Automatic 3D Object Rigging. 3D Rigging, the task of predicting skeletons and skin weights for a 3D mesh, is a fundamental problem in computer graphics [41,57,68,76,78]. Driven by the accessibility of open-source datasets, learning-based methods have outperformed traditional manual rigging. However, most public datasets either focus on static meshes [16,54,67,68], or provide animations restricted to narrow categories such as humanoids [1,33,35] or quadrupeds [30,65]. Building upon these datasets, automatic rigging methods [16,32,41,45,54,68] aim to predict skeletons and skin weights directly from geometry. To enable animating previously static characters through predicted skeletons, such methods often remain dependent on handcrafted correspondences or manually curated motions.

Correspondence learning constitutes a fundamental challenge in vision and graphics [17,62,63,66,79], and is particularly crucial for pose transfer. However, establishing reliable mappings between non-rigid meshes remains highly challenging. Dense correspondence methods [36,44,52] predict per-vertex mappings by optimizing complex energies, but are computationally expensive, unstable, and generalize poorly beyond limited categories.

Recent works [2,12,31,39,42,71] instead consider sparse correspondences at the vertex or keypoint level, often using self-supervised learning to avoid the need for ground-truth dense annotations. These approaches are more flexible and can leverage existing rigging datasets [30,68], but typically assume one-to-one mappings and remain restricted to intracategories, struggling to handle cross-category correspondences (e.g., between humanoids and quadrupeds).

In contrast, we construct a dataset spanning diverse categories and character-level animations, and leverage semantic keypoint annotations to supervise many-to-many soft correspondences. This allows correspondence learning across characters with length-variant keypoints, providing a stronger foundation for cross-category pose transfer. 3D Pose Transfer. Deformation transfer, i.e., the process of retargeting and transferring 3D poses across characters, is essential for animation, simulation, and virtual content creation. [7,22,28,53,64,69,72,80]. Early works [4,5,20,56] formulate deformation transfer as an optimization problem, but require handcrafted correspondences (e.g., point-or pose-wise) that are costly and nonscalable. Recent motion transfer methods [13,29] suffer from a reliance on exemplar motions from the target character, which constraints their applicability when such data is unavailable. Skeleton-or handle-based models [12,31] predict relative transformations between keypoints, but typically assume one-to-one correspondences and are trained on pose datasets with limited human characters [1,30,37]. As a result, they struggle to generalize across categories with inherently different skeletal structures. To bypass explicit correspondence supervision, recent works adopt implicit deformation fields [3], adversarial learning [8,11], cycle-consistency training [18,82], or conditional normalization layers [10,60]. Nevertheless, these methods remain restricted to structurally similar characters and fail on stylized or cross-species transfers.

Recent novel large-scale articulation datasets [15,16,54] have enabled learning high-quality geometric features and reliable skeleton predictions [54] across diverse species. Drawing on these insights, we leverage pretrained shape encoders alongside a novel dataset of diverse animations to propose a cascade-transformer framework that extends pose transfer beyond humanoids to a broad range of characters.

Task Definition. Given a source character in canonical pose Vsrc ∈ R N src ×3 , its posed instance V src with pose parameters p, and a target character in canonical pose Vtgt ∈ R N tgt ×3 , the objective of pose transfer is to generate the posed target mesh Vtgt . Formally, we seek a mapping f (V src , Vsrc , Vtgt ) → Vtgt , where Vtgt retains the target’s geometry while transferring the pose p from the source.

Character Articulation Formulation. We follow [12,31] to represent character deformations via keypoints and skin weights. The keypoints C ∈ R K×3 together with pervertex skin weights W ∈ R N ×K are estimated by pretrained model [68]. The number of keypoints K may vary across characters (denoted as K 1 and K 2 for source and target characters). The deformation of a character is achieved by assigning per-keypoint transformation T ∈ R K×7 , and applying linear blend skinning (LBS) [24] to deform the mesh from canonical space to posed space:

where ck ∈ C denotes the canonical keypoints. For the posed character, the corresponding keypoints c k are approximated by the weighted average of the deformed vertices.

Geometry Priors. We utilize a pretrained 3D shape encoder E [81] to extract geometry features f E ∈ R l E ×d from a given character mesh, where l E denotes the number of query tokens. We extract geometry features for the canonical source (f Vsrc ), posed source (f V src ), and canonical target characters (f Vtgt ). In addition, we define the residual geometry feature of the source character as δ f = f V src -f Vsrc , which captures the deformation difference between the posed and canonical source meshes in latent space.

Challenges. Humans possess the cognitive flexibility to imagine how animals imitate human behaviors and vice versa. In contrast, most existing pose transfer approaches remain restricted to narrow settings (e.g., humanoid-tohumanoid). A more general and practical goal is categoryfree pose transfer across diverse characters. However, it is substantially more challenging, with two key obstacles: 1. Diverse skeletons and geometries. Characters differ drastically in skeletal structure, geometric topology, and mesh density. Directly estimating per-vertex correspondences across such variations is infeasible. A common workaround is to employ intermediate representations such as keypoints. Yet, existing works assume a fixed set of keypoints across categories, overlooks the inherent variation in anatomical structures (e.g., bones, limbs, and wings). This mismatch makes one-to-one keypoint mapping unreliable and often degrades transfer quality. 2. Scarcity of paired data. Datasets with diverse characters and artist-designed poses are extremely limited. As a result, most existing pose transfer methods rely on reference poses from large-scale humanoid datasets with only a few animal samples, which prevents them from generalizing to non-human characters. Moreover, the absence of ground-truth keypoint correspondences makes it difficult for models to learn accurate mappings in a purely self-supervised manner. Creating such correspondences manually is prohibitively costly and labor-intensive.

Overview. To tackle these challenges, we collect a new dataset of high-quality skeletons and diverse character motions spanning humanoids, quadrupeds, birds, and more.

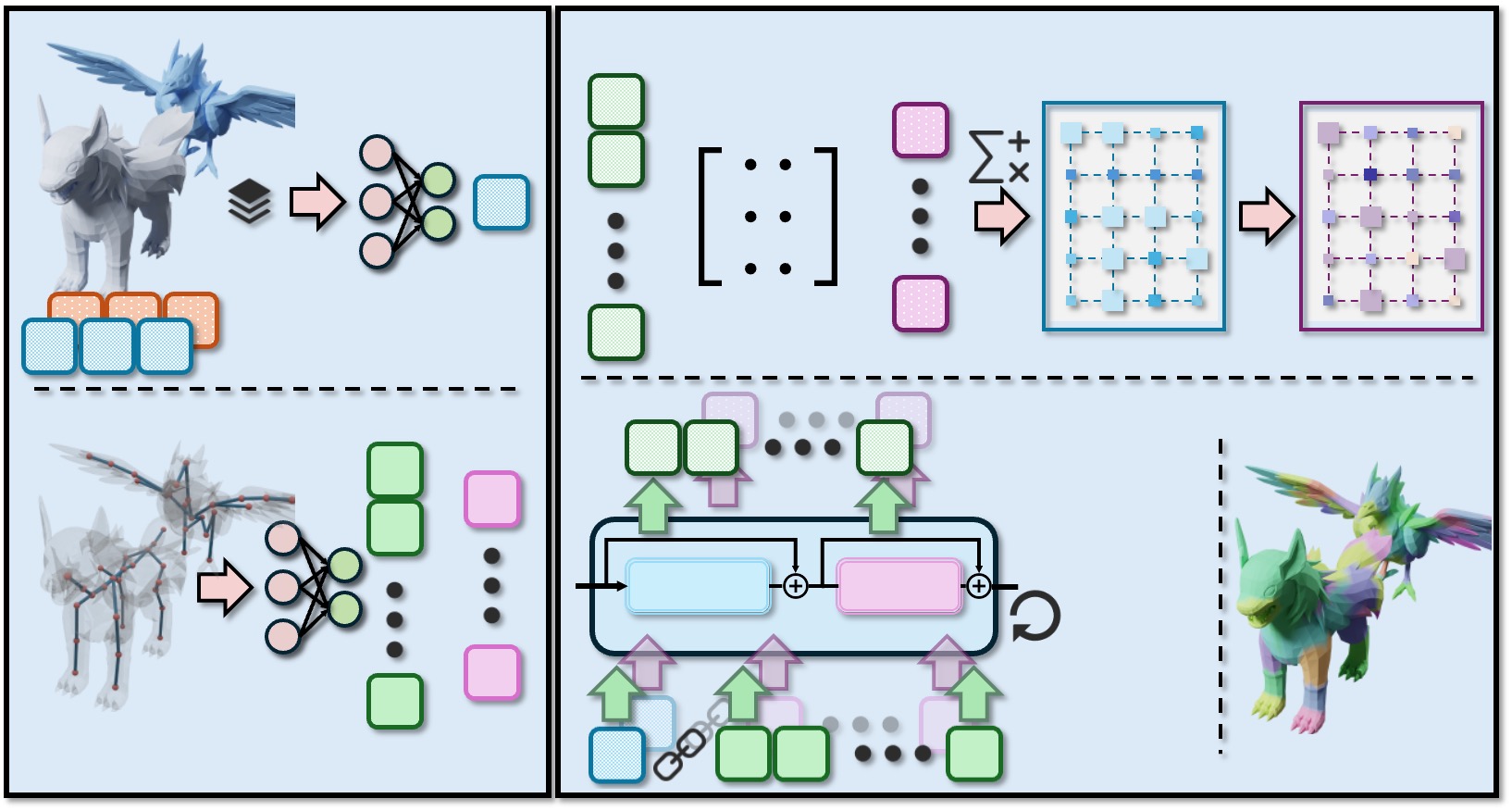

Building on this, we introduce MimiCAT, a cascadetransformer architecture designed for category-free pose transfer. MimiCAT learns soft correspondences across keypoints of different meshes and transfers poses accordingly. An overview of our framework is illustrated in Fig. 2, and the following sections detail our technical contributions.

Collecting Diverse Character Motions. To overcome the above challenges and enable generalization across character categories, we curate a new dataset, PokeAnimDB, from the web consisting of high-quality, artist-designed motions for a wide range of characters. These motions span various actions, such as running, sleeping, eating, and fighting.

For efficient training, we follow prior works [16,31,68] to resample each character mesh into 5,000 faces and recompute skinning weights via barycentric interpolation based on the artist-provided per-vertex weights. We additionally record bone names for each character, which provide structural cues in the text domain and enable connections across categories (e.g., the label “limbs” can correspond to “arms” for humanoids and “wings” for birds). All meshes are unified into .obj format, while skeletal animations are stored in .bvh format for consistency.

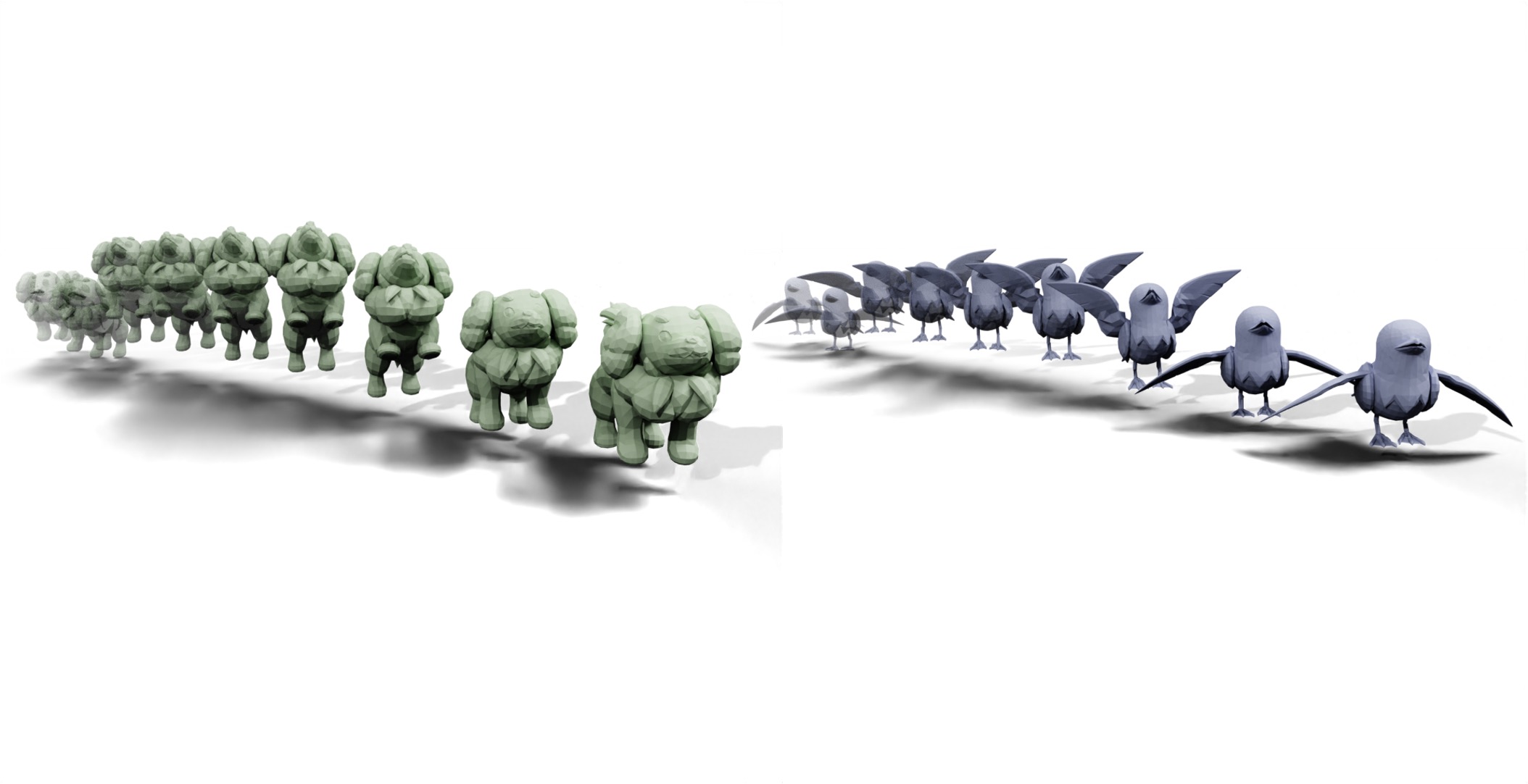

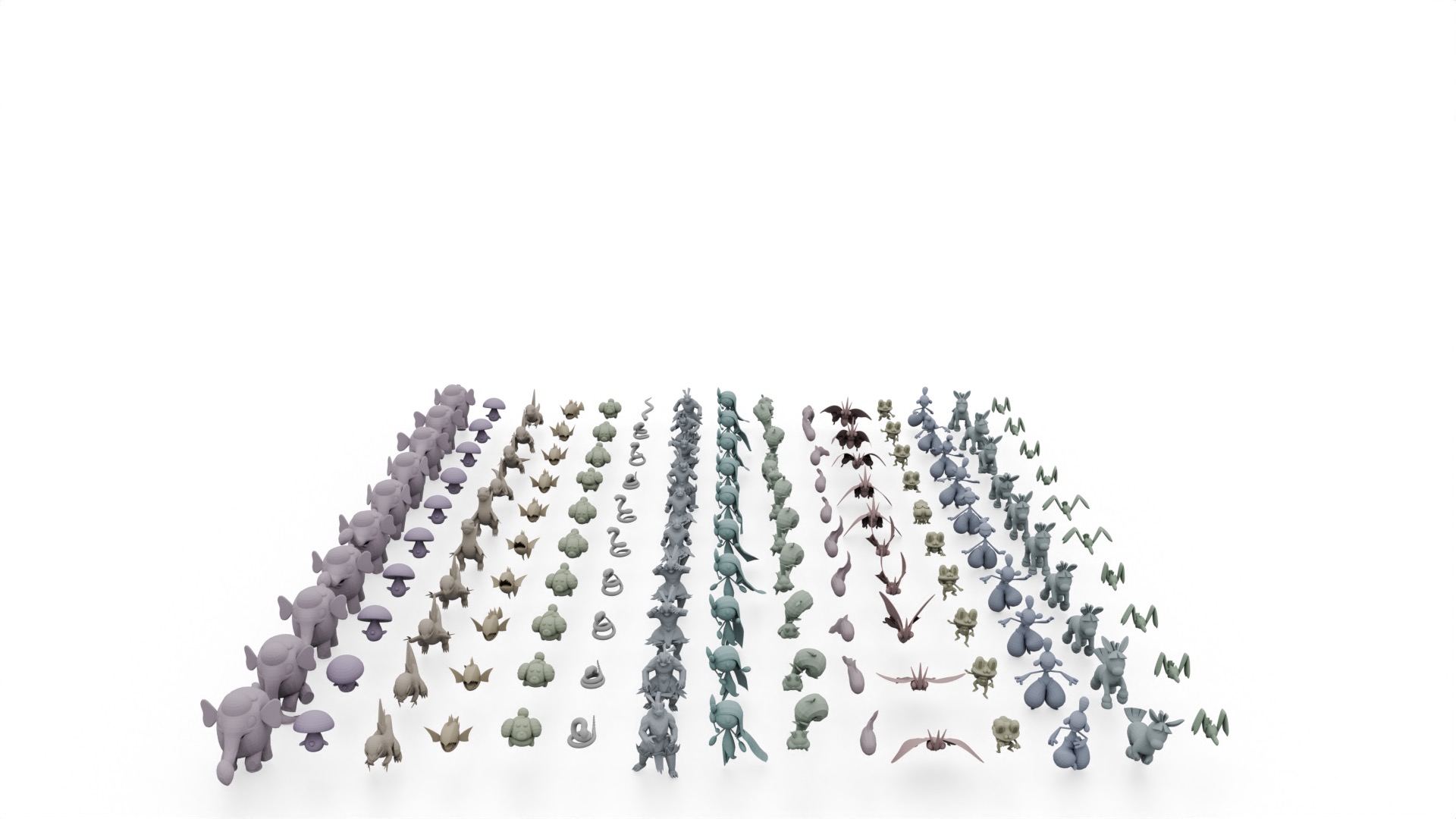

Dataset Statistics. Tab. 1 summarizes PokeAnimDB in comparison with existing publicly available animation datasets. Unlike prior collections, our dataset comprises 975 characters spanning a broad spectrum of species and morphologies, including humanoids, quadrupeds, birds, reptiles, fishes, and insects. The number of skeletal joints ranges from 11 to 241, with an average of 83. Each character is paired with artist-designed skeletal animations, resulting in a total of 28,809 motions and 4,473,481 frames, which is comparable in scale to the widely-used human motion datasets [37]. Examples that highlight the diversity and quality of our dataset are illustrated in Fig. 3.

To achieve category-free pose transfer, we propose a cascade-transformer model, MimiCAT, that learns soft keypoint correspondences for shape-aware deformations and is trained with a two-stage scheme.

Shape-aware Keypoint Correspondence. We design a correspondence transformer G that integrates shape conditioning to estimate soft correspondences between keypoint pairs of varying lengths. Given canonical keypoints Csrc and Ctgt from the source and target characters, respectively, G predicts a similarity matrix S ∈ R K1×K2 and its normalized counterpart, a doubly-stochastic matrix M, representing the probabilistic correspondence between keypoints. An overview of the G architecture is shown in Fig. 4.

In contrast to GNN-based models [62,63] that rely on skeletal connectivity priors and may not generalize well to characters with diverse hierarchical structure, we directly encode spatial coordinates of keypoints using MLP layers to obtain keypoint tokens g C ∈ R K×dc . To enhance discrim- ination between correlated body parts, we further incorporate shape features f Vsrc and f Vtgt extracted from pretrained models [81]. These features are concatenated and processed by MLP layers to produce high-dimensional shape tokens g M ∈ R l E ×dc . The shape tokens are then combined with the keypoint tokens to form [g M , g C ], which are fed into transformer blocks to learn shape-aware latent representations g src and g tgt for the source and target keypoints.

The pairwise similarity matrix S between the source and target latent features is computed using a learnable affinity matrix A. The resulting similarity scores are exponentiated and normalized into a doubly stochastic correspondence matrix M via the Sinkhorn algorithm [51], where each entry M i,j represents the soft matching probability between a source and a target keypoint:

Correspondence-aware Transformation Initialization. Given the canonical and posed meshes, keypoints, and skin weights of the source character, we first follow [6,31] to estimate per-keypoint transformations

, where each transformation T src i includes a rotation quaternion q i and a translation vector t i .

Using the correspondence matrix M from Eq. 2, the initial transformations of the target character are obtained by aggregating the source transformations according to the matching probabilities. For each target keypoint c j ∈ C tgt , its translation tj and associated query position cj in the source character are calculated as weighted averages:

Directly averaging quaternions, however, is invalid because it neither guarantees unit-norm rotations nor resolves the inherent 2 : 1 ambiguity of quaternions-often leading to inconsistent or flipped orientations (see Fig. 9). Instead, we compute the weighted average rotation by minimizing the Frobenius norm between attitude matrices:

where A(q) ∈ SO(3) denotes the attitude matrix of quaternion q. Following [38,43], the solution qj is given by the eigenvector corresponding to the largest eigenvalue of the weighted covariance matrix, i.e., K1 i=1 M i,j q i q ⊤ i .

Shape-aware Pose Transfer. Given the initialized transformations, our goal is to refine them into the final target transformations while incorporating geometric conditions.

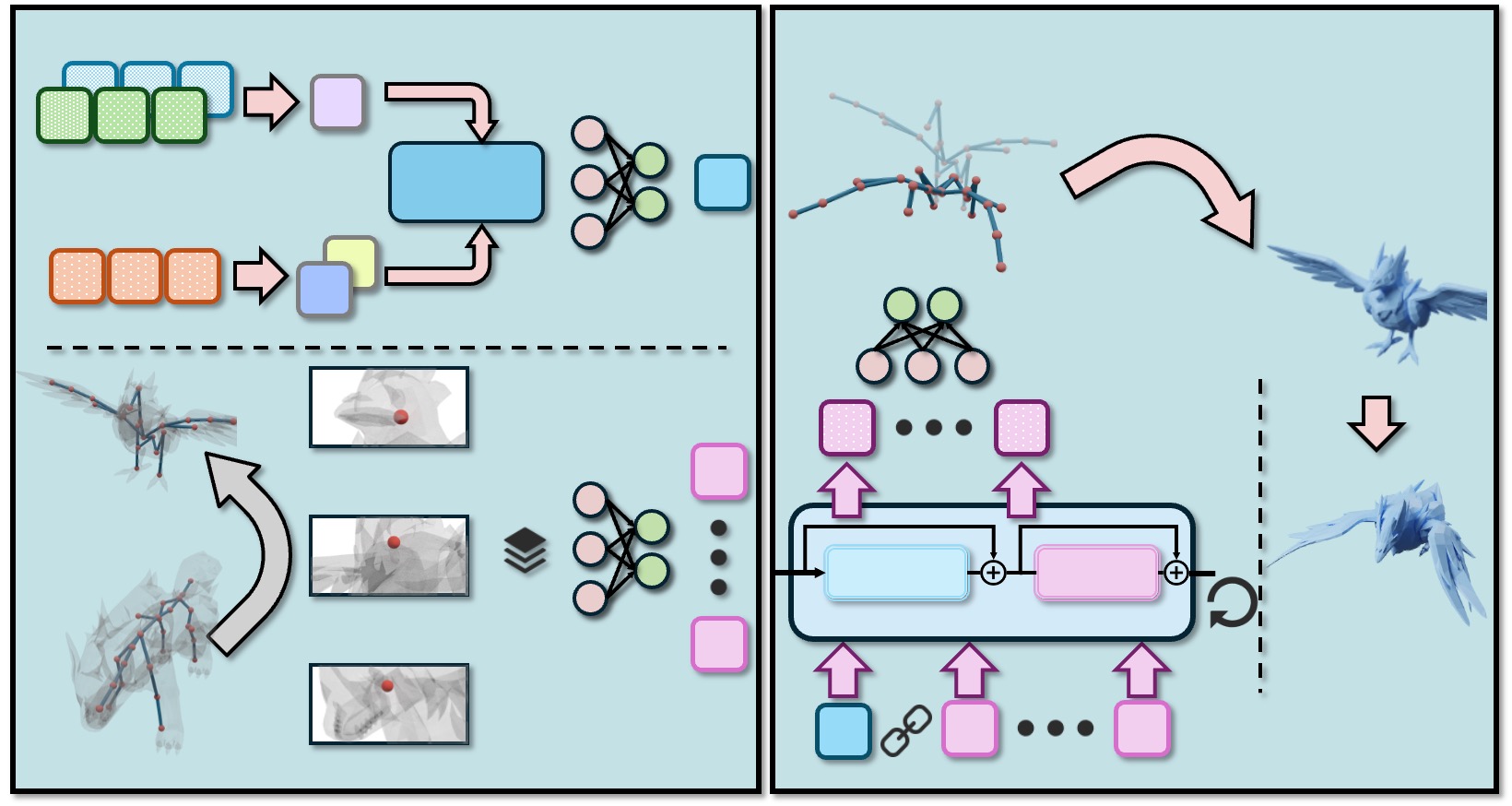

To achieve this, we design a pose transfer transformer H that maps shape and keypoint features to per-keypoint transformations of the target character, as illustrated in Fig. 5. We extract geometry features f Vsrc , f V src , f Vtgt from the canonical and posed source meshes and the canonical target mesh, respectively. These features are fused through crossattention layers to inject the residual source deformation cues δ f into the target representation, producing geometrycondition tokens h M . For the keypoint representation, each target keypoint c j is paired with its query position cj and initialized transformation tj , qj . The concatenated vector [c j , cj , tj , qj ] is then projected through MLP layers to form high-dimensional keypoint tokens h C ∈ R K2×dc .

Finally, the geometry tokens h M and keypoint tokens h C are concatenated to form [h M , h C ] and fed into transformer blocks, producing shape-aware latent features. MLP layers decode these features into per-keypoint transformations

, which are applied to deform the canonical target mesh into final posed mesh Vtgt via Eq. 1.

Text-Guided Ground-truth Correspondence. A key prerequisite for correspondence learning is access to reliable “ground-truth” matches. However, manually annotating either keypoint-or vertex-level correspondences for largescale pairs is highly non-trivial and labor-intensive.

Fortunately, the artist-designed characters themselves furnish semantic keypoint names. For example, the arms of humanoids and the wings of birds are both labeled as “limbs”, which aligns with human perception of their functional similarity. Drawing from this observation, we bypass handcrafting correspondences or designing sophisticated algorithms [66,74]. Instead, we use CLIP E CLIP [49] to encode the textual labels of keypoints c k into latent space, yielding f k . We compute the similarity matrix S cos ∈ R K1×K2 via cosine similarity, each element s i,j given by:

where s i,j measures the similarity between source and target characters c i ∈ C src and c j ∈ C tgt . Finally, we normalize S cos using the Hungarian algorithm [26] to obtain ground-truth one-hot correspondence M hung . Fig. 6 showcase examples of our text-based ground-truth v.s. hierarchical correspondence [74].

Two-Stage Training. We train MimiCAT using two-stage process. In the first stage, we train the correspondence transformer G. We note that multiple keypoints from the source character may correspond to a single keypoint in the target, and vice versa. Therefore, in addition to the hard one-to-one mapping M hung obtained via the Hungarian algorithm, we introduce a soft-matching matrix M sink = Sinkhorn(S cos ), which captures many-to-many correlations between source and target keypoints. We then use the Frobenius norm to jointly encourage the predicted affinity matrix S to align with the text-based cosine similarity matrix S cos , while maintaining consistency between the predicted correspondence M, the soft Sinkhorn mapping M sink , and the hard assignment M hung :

2 . (6) In the second stage, we freeze the correspondence transformer G and train the pose transfer transformer H using a cycle-consistency objective. Since ground-truth targets are unavailable for cross-category pairs, we adopt a selfsupervised strategy that reconstructs the source character from its transferred pose. Specifically, we first transfer the pose from the source to the target, and then back from the predicted target to the source. The reconstruction loss encourages the recovered source mesh to match the given one: where Vtgt = f (V src , Vsrc , Vtgt ) and Vsrc = f ( Vtgt , Vtgt , Vsrc ).

To further regularize rotations, we employ the pretrained pose prior model F. Given the ground-truth posed character V src , we use F to estimate the pose distribution parameters F of each keypoints. Then, if the predicted rotation qk for k-th keypoint is reasonable, we assume it shows the max log-likelihood given the distribution parameters based on V src . Hence, we enforce the estimated rotation to preserve minimal negative log-likelihood (NLL) properties [40,50].

where Fk denotes the predicted distribution parameters for the k-th keypoint, c( Fk ) is the normalization constant w.r.t. the distribution parameters Fk . Additionally, we encourage the reconstructed meshes in the cycle process to preserve consistent high-level geometric features with their original posed counterparts by enforcing feature-space consistency,

Inference Stage. During inference, given the canonical poses of both the source and target characters, we first apply the pretrained skeleton prediction model [68] to obtain their corresponding skin weights and skeleton structures. MimiCAT then deforms the source pose into the target character according to the learned soft correspondences and transformation mappings. Finally, following prior works [31,77], we perform test-time refinement using an as-rigid-as-possible (ARAP) [55] optimization to en-Target NPT [60] CGT [9] SFPT [31] TapMo [77] Ours hance mesh smoothness and preserve local geometric details in the final deformed results.

We implement MimiCAT using PyTorch framework [46] and train it with the AdamW optimizer [34], starting with an initial learning rate of 1e-4 for both stages. Our training corpus combines Mixamo [1], AMASS [37], and our newly collected PokeAnimDB, covering diverse and complex shapes and poses. The dataset is split into training, validation, and test sets. In the first stage, we train the correspondence transformer with 384k source-target pairs using a mini-batch size of 128 for 60 epochs. In the second stage, we train the pose transfer transformer for 200 epochs with a mini-batch size of 100, sampling 100k random poses per epoch. All experiments are conducted on 8 NVIDIA A100 GPUs. More details are provided in the Appendix.

Benchmarks. We evaluate category-free pose transfer under two settings. (1) Intra-category transfer: We select the widely-use Mixamo [1] to assess pose transfer among humanoid characters. Since all Mixamo characters share the same skeleton structure, the ground-truth targets are generated by directly applying the source transformations. We construct 100 character pairs, each with 20 random test poses, resulting in a total of 2,000 evaluation cases. ( 2) Cross-category transfer: To assess generalization beyond specific categories, where ground-truth poses are unavailable, we adopt a cycle-consistency evaluation, where each method performs pose transfer in both directions, and the consistency between the source and reposed character is measured to quantify transfer quality. We randomly sample 300 character pairs from our dataset and Mixamo, covering both humanoid-to-any and any-to-humanoid settings, with 10 poses per pair, resulting in 3,000 evaluation cases.

Evaluation Metrics & Baselines. Following previous works [31,61,71], we adopt two metrics for quantitative evaluation: Point-wise Mesh Euclidean Distance (PMD), which measures pose similarity between the predicted and ground-truth deformations, and Edge Length Score (ELS), which evaluates edge consistency after deformation to assess the overall mesh smoothness. We compare MimiCAT against 4 state-of-the-art pose transfer methods [9,31,60,77]. As MimiCAT is among the first to address categoryfree pose transfer, previous work was originally trained within specific domains. For fair comparison, we re-train or fine-tune their publicly available implementations using the same mixed-character training data described in Sec. 4.1.

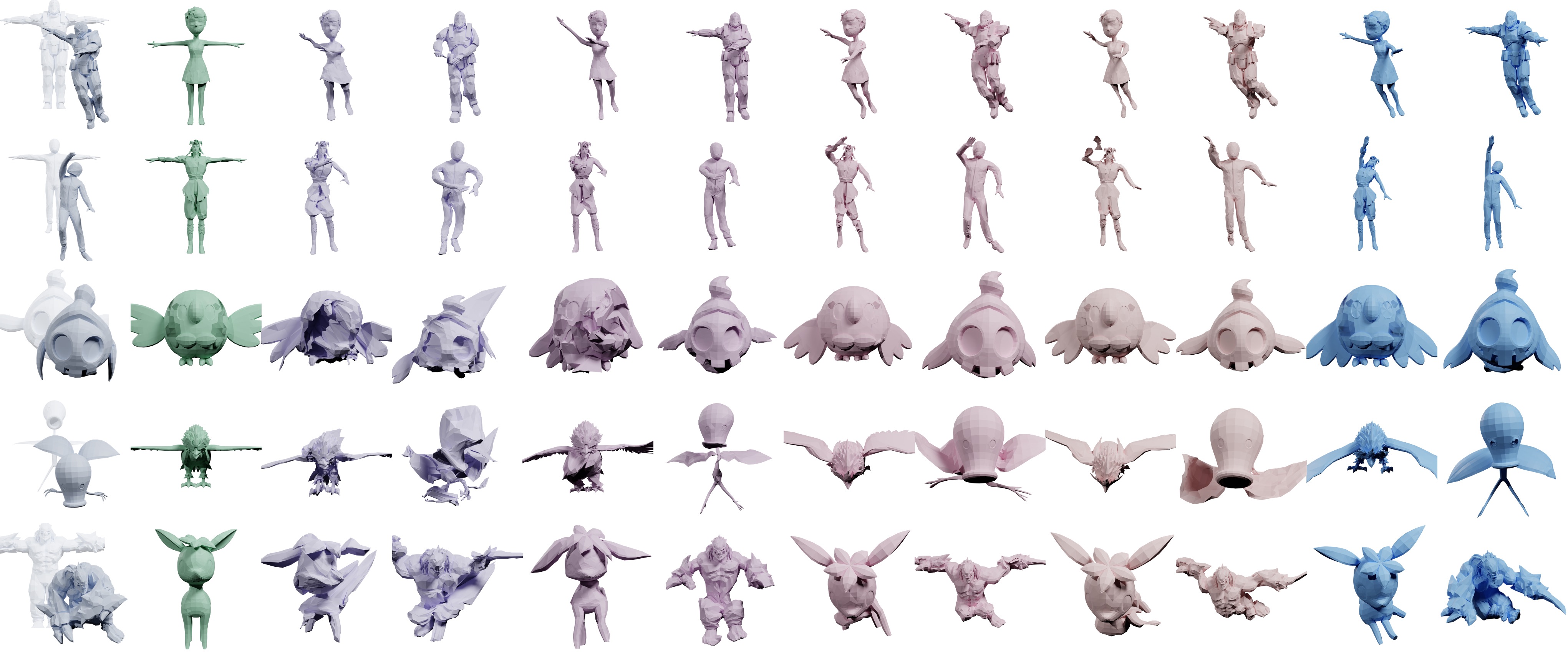

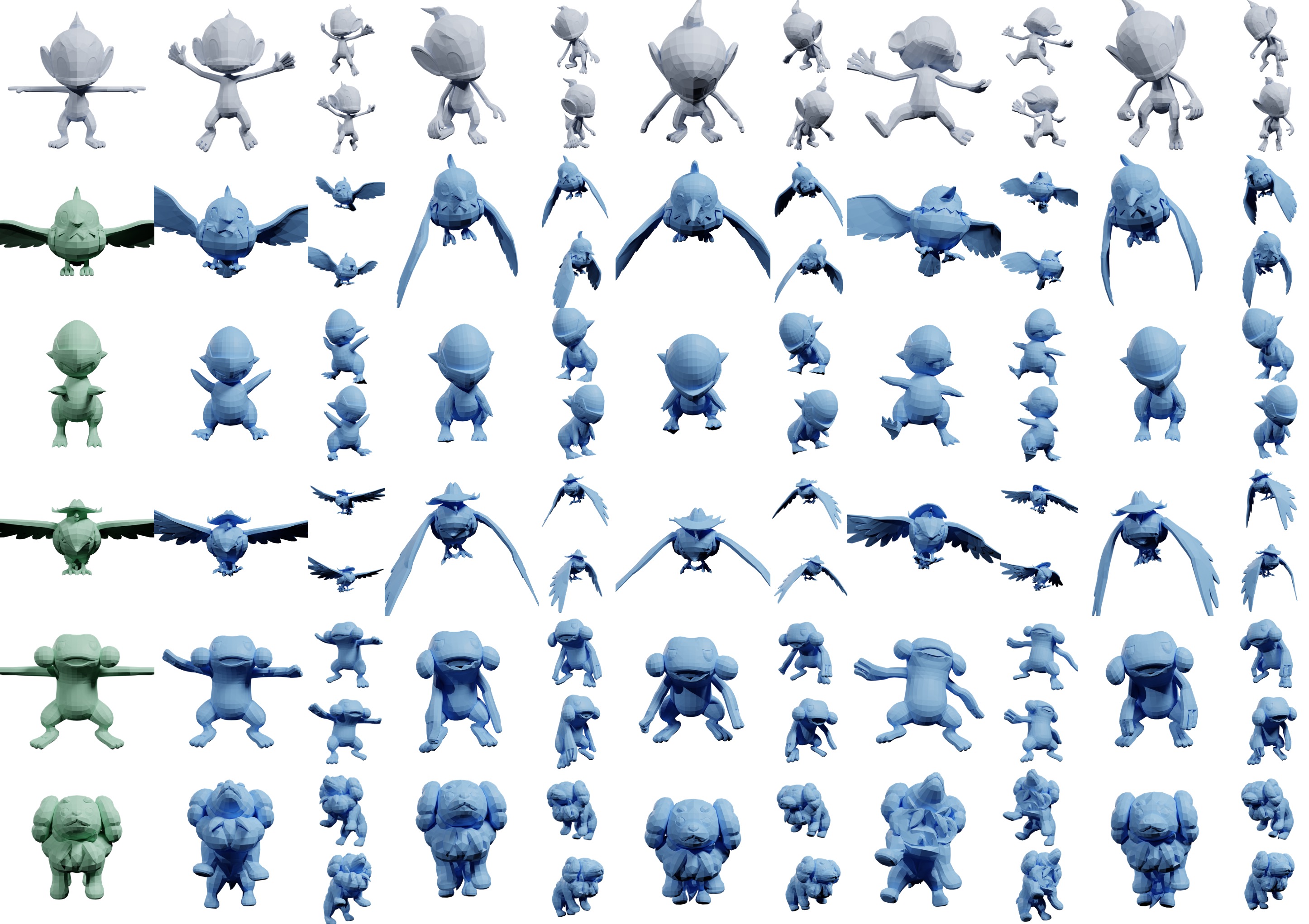

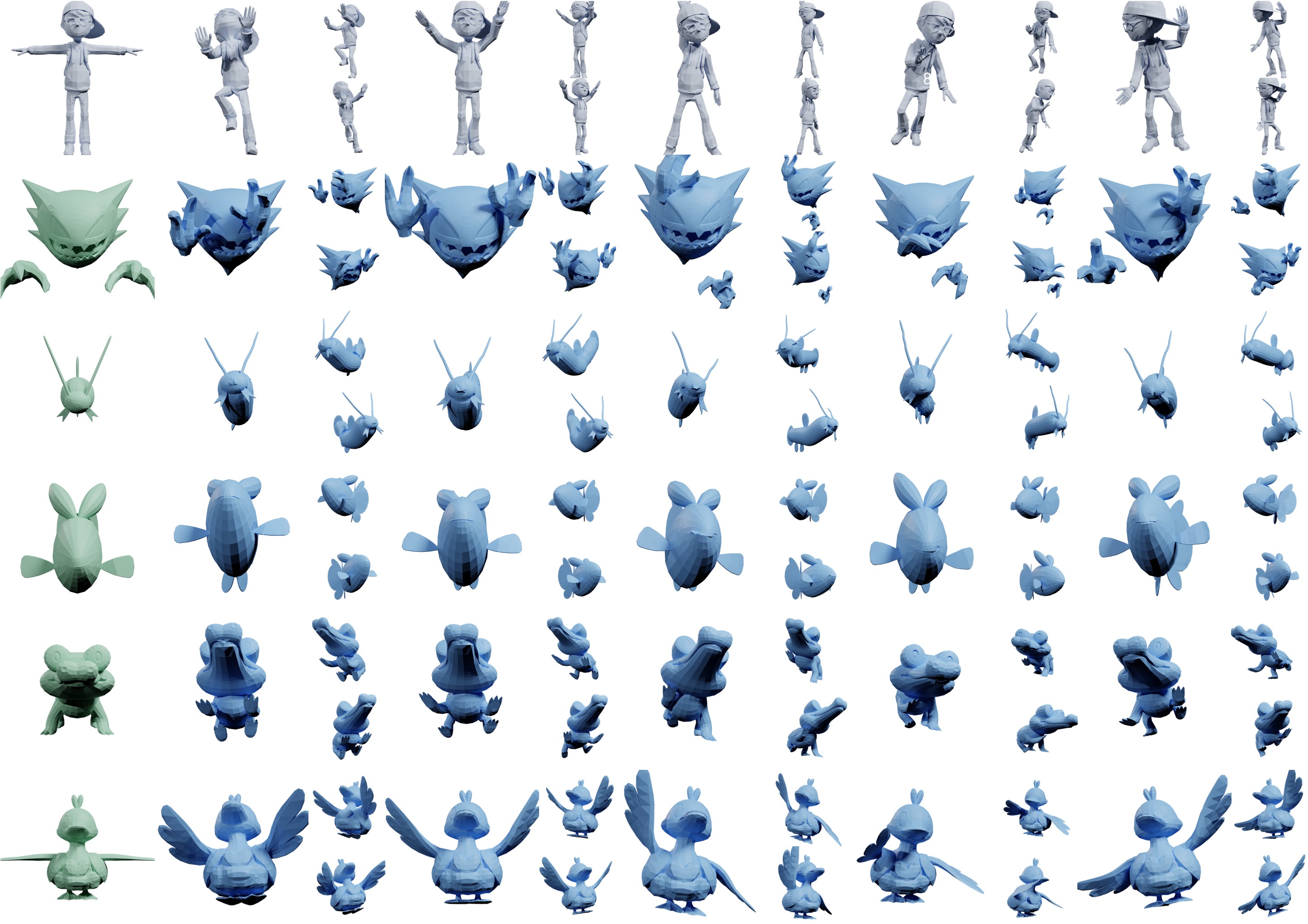

In Fig. 7, we present qualitative results for category-free pose transfer across diverse character types, including humanoids, fishes, quadrupeds, and birds, demonstrating the robustness of MimiCAT compared to prior methods. Previous approaches (e.g., NPT [60] and CGT [9]) rely on self-supervised learning within paired data of similar characters, limiting their ability to generalize to unseen categories. SFPT [31] and TapMo [77] depend on a fixed number of handle points for deformation, which restricts them to one-to-one mappings and leads to artifacts or twisted poses when transferring across topologically different char- acters. In contrast, the proposed MimiCAT leverages soft keypoint correspondences for flexible many-to-many mappings, enabling natural and semantically consistent pose transfer across morphologically diverse characters. For instance, in the third row, a human pose with arms fully extended is vividly transferred to a bird spreading its wings, while maintaining structural consistency such as the alignment between the human thighs and bird claws.

Quantitative results are shown in Tab. 2, with the best results bolded. NPT [60] and CGT [9] are designed for transferring poses with same topology, therefore their performance degrades noticeably in cross-category scenarios. SFPT [31] and TapMo [77] show improved generalization in categoryfree scenarios but remain constrained by their one-to-one correspondence assumption. In contrast, MimiCAT consistently achieves the best results across both settings, which demonstrate that our model effectively captures and transfers pose characteristics even across characters with distinct structures and topologies. These gains stem from our shapeaware transformer design, which leverages geometric priors and flexible, length-variant keypoint correspondences to enable robust and accurate pose transfer.

The category-free nature of MimiCAT enables it to serve as a plug-and-play module for text-to-any-character motion generation, greatly expanding the applicability of existing T2M systems. As shown in Fig. 8, we take motions produced by off-the-shelf T2M models [14,23]-originally defined on SMPL skeletons [33,47]-and use MimiCAT to transfer them frame-by-frame into a wide variety of target characters, yielding diverse and visually compelling animations. This demonstrates the potential of MimiCAT as a general-purpose motion adapter for downstream tasks.

Settings. To assess the contribution of each key component in MimiCAT, we conduct ablation studies by removing or replacing individual modules while keeping other parts unchanged for fair comparison. Specifically, we evaluate: A1 (w/o Eq. 4): replacing our rotation initialization with a simple equal weighted sum instead of the blending scheme in Eq. 4; A2 (w/o Eq. 8): removing the pose prior regularization; and A3 (w/o Eq. 5): pretraining the correspondence module G using hierarchical correspondence algorithm [66,74] instead of text-based supervision.

Results. The qualitative and quantitative comparisons are shown in Fig. 9 and Tab. 2, respectively. Without the pose prior (A2), unnatural deformations such as joint twisting and self-intersections occur, showing that motion priors learned from large-scale motion datasets help constrain plausible transformations. Using naive rotation averaging (A1) introduces orientation ambiguity, often causing distorted poses (e.g., limbs and wings in target characters). Finally, replacing text-based supervision with heuristic correspondences (A3) leads to misaligned mappingse.g., a dog’s hind legs being incorrectly matched to the source’s arms-highlighting the necessity of semantic alignment in correspondence learning. Overall, the full Mimi-CAT achieves the best transfer quality, validating the complementary effects of each component in enabling robust and semantically consistent pose transfer.

This paper introduces MimiCAT, a cascade-transformer framework supported by a new large-scale motion dataset, PokeAnimDB, to advance 3D pose transfer toward a general, category-free setting. To the best of our knowledge, this is among the first works to enable pose transfer across structurally diverse characters. Benefit from the million-scale pose diversity of PokeAnimDB, MimiCAT learns flexible soft correspondences and shape-aware deformations, enabling plausible transfer across characters with drastically different geometries. We further demonstrate the versatility of MimiCAT in downstream applications such as animation and virtual content creation. We believe PokeAn-imDB will serve as a valuable resource for broader vision tasks and inspire future research within the community.

MimiCAT: Mimic with Correspondence-Aware Cascade-Transformer for Category-Free 3D Pose Transfer

This supplementary material provides additional technical details and presents further visualized results supporting the main paper. The content is organized as follows: First, the notations used throughout the paper is summarized in Section A1. Section A2 describes the details of our pose prior model. Section A3 presents further implementation details. Section A4 includes additional qualitative visualizations. Finally, Section A5 discusses the limitations of our method and outlines potential directions for future work.

For clarity and ease of reference, the key notations used throughout the paper are summarized in Tab. A1.

In this section, we provide technical details of the pose prior model, including how we address the challenges arising from varying keypoint lengths and diverse rotation behaviors across characters, as well as the training objectives.

We observe that without proper priors or regularization, the pose transfer model often suffers from severe degeneration such as collapse. However, directly learning unified rotation representations across characters with highly diverse geometries and skeletal structures is non-trivial. To address this, we leverage our motion dataset to train a probabilistic prior model that explicitly captures the likelihood of skeletal structures together with their associated rotations. Formally, the rotation of each keypoint is represented by a quaternion q ∈ S 3 [31]. One option is to parameterize this distribution using the Bingham distribution [19]. However, the Bingham distribution requires strong constraints on its parameters, which limits model expressiveness [50]. Instead, we follow previous works [40,50,70] to map quaternions to attitude matrices R = A(q) ∈ SO(3) and model them using the matrix-Fisher distribution, which defines a probability density over SO(3):

where F k ∈ R 3×3 is the distribution parameter of the k-th keypoint, and c(F k ) is the normalization constant. Similar to the cascade-transformer design of MimiCAT, to capture the joint distribution of rotations across all keypoints of arbitrary characters, we design a transformerbased pose prior model

, where C and C denote canonical and posed keypoints, and f V, f V are geometry features extracted from the corresponding meshes.

Specifically, we concatenate f V and f V and project them through the shape projector to obtain the shape tokens f M ∈ R l E ×dc . For the keypoints tokens, we concatenate the canonical and posed keypoint coordinates C and C, and map them into a d c -dimensional latent representation f C ∈ R K×dc via keypoint encoder. The concatenated tokens [f M , f C ] are then fed into transformer blocks, which applies attention mechanism to model interactions among keypoints while conditioning on global geometry. Finally, an MLP decoder maps the latent representations to a set of matrix-Fisher distribution parameters a linear layer, with hidden dimension of 1,024.

For F , G, and H, each module adopts a 6-layer stacked transformer encoder, where every layer comprises a multihead self-attention (MHSA) module (with 8 heads) followed by a 2-layer MLP. The MLP uses a hidden dimension of 2,048. The distribution decoder of F is a 2-layer MLP with a hidden dimension of 128 and nonlinear activation. For the correspondence module G, the learnable weights A is parameterized with a hidden dimension of 256. The transformation decoder of H is implemented as an MLP with a hidden dimension of 256.

For the AMASS dataset, we follow the standard protocol in prior works [31,82]

As stated in the main paper, PokeAnimDB provides character-level motion sequences, forming a large-scale corpus of diverse 3D character poses. Each character is associated with a set of predefined motion clips spanning various action categories. On average, a character contains approximately 30 actions, with the number ranging from 3 to 102. Fig. A1 further illustrates the diversity of poses and character types captured in our dataset.

Target NPT [60] CGT [9] SFPT [31] TapMo [77] Ours

As a supplement to our quantitative evaluation, we provide additional visual comparisons of pose transfer quality in Fig. A5. For each method, we show both the transferred target poses and the corresponding cycled-source reconstructions. The first two rows show examples of humanoid-tohumanoid transfer, where we also include cycle-consistency results for reference. The remaining three rows illustrate a variety of cross-category transfer cases, covering challenging scenarios with large geometric and topological discrepancies. These visualizations qualitatively confirm our quantitative findings: MimiCAT achieves the smallest PMD while preserving mesh smoothness (highest ELS), producing more plausible transfer results than prior baselines.

Although MimiCAT achieves state-of-the-art performance compared to existing baselines, it still has several limitations. In this section, we discuss the limitations of our work and outline several future research directions.

First, our framework relies on keypoints and skin weights predicted by pretrained models. Errors in this stage may propagate to the downstream pose transfer pipeline and negatively affect the final results. In the future, we plan to explore an optimization framework that jointly updates the skin weights, keypoints, and target transformations, such that they coherently contribute to the final transfer quality.

Second, as the exploration of efficient transformer architectures is beyond the scope of this work, MimiCAT adopts computationally expensive vanilla attention implementations. An important extension would be to incorporate more efficient attention mechanisms (e.g., linear or sparse attention) to reduce computational cost while maintaining-or potentially improving-the quality of pose transfer.

Finally, while we demonstrate that MimiCAT can serve as a plug-and-play module for zero-shot text-to-anycharacter motion generation, the current pipeline does not explicitly enforce temporal consistency across frames. Incorporating temporal modeling could significantly improve motion-level coherence and stability. In future work, we plan to leverage the dataset introduced in this paper to further advance 4D generation and general motion synthesis.

📸 Image Gallery