- Title: Bridging Information Security and Environmental Criminology Research to Better Mitigate Cybercrime

- Authors: Colin C. Ife, Toby Davies, Steven J. Murdoch, and Gianluca Stringhini

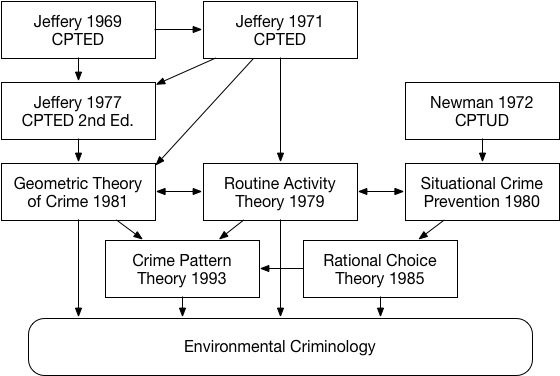

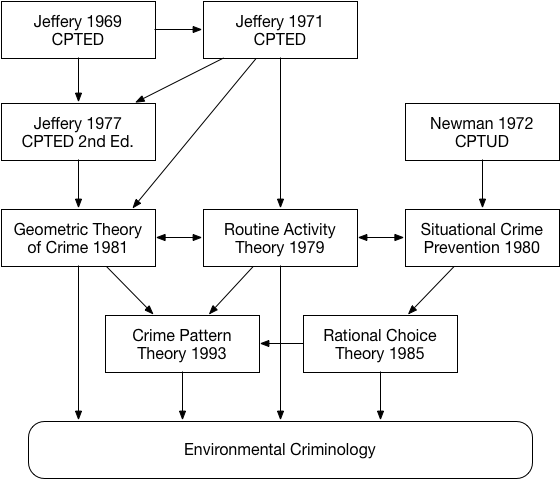

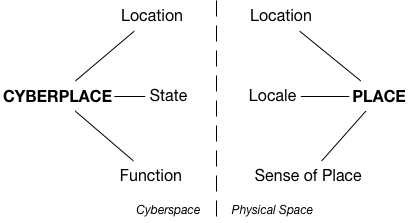

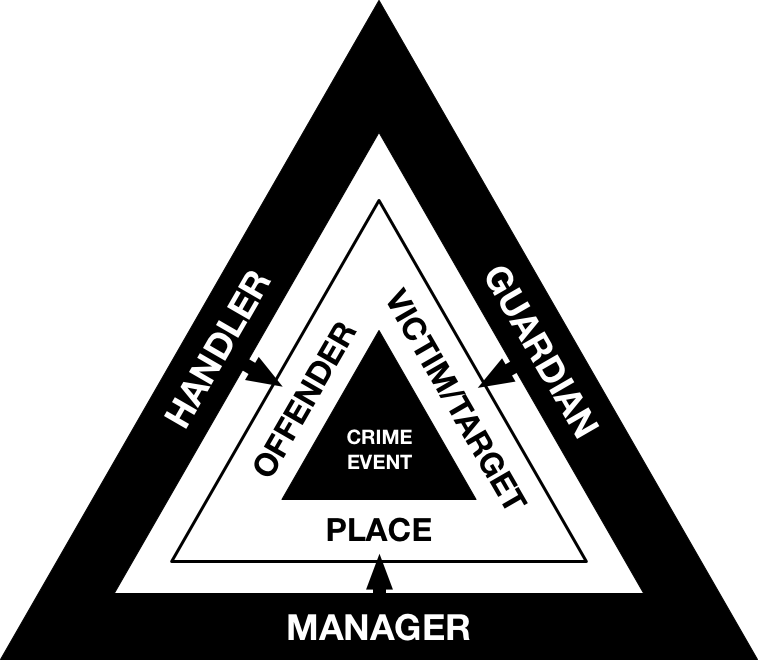

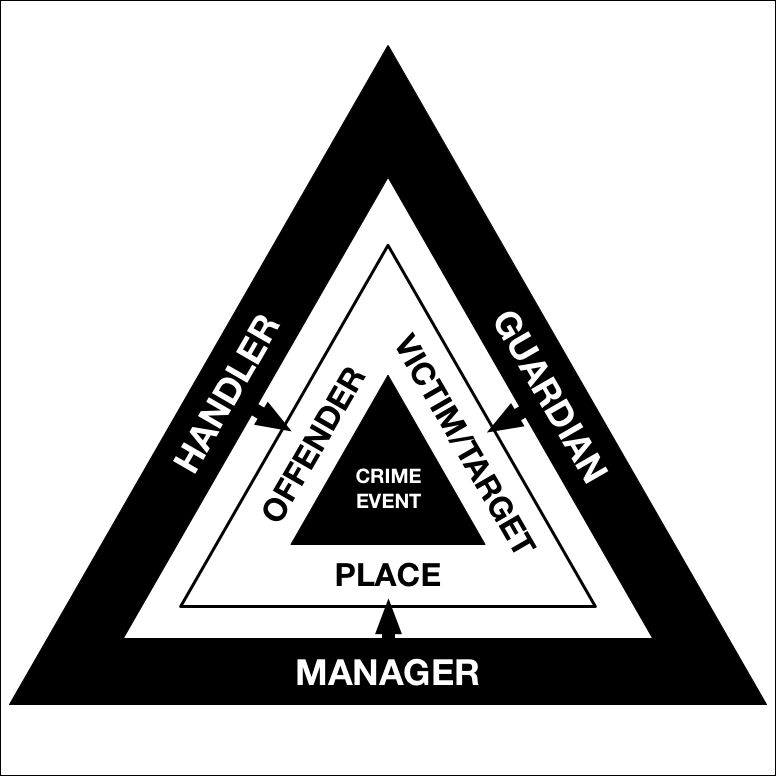

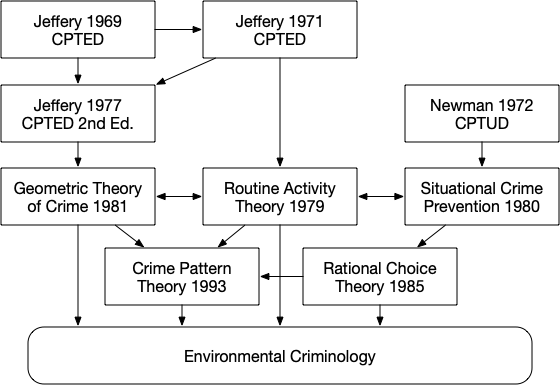

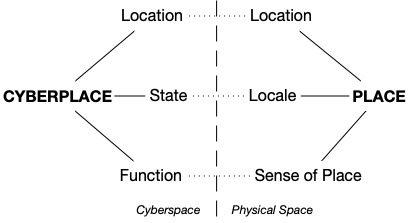

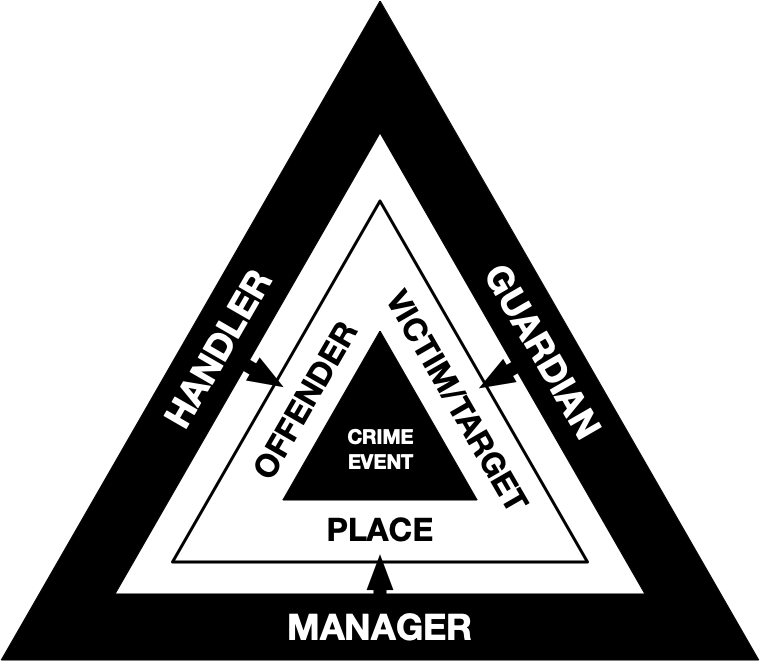

Cybercrime is a complex phenomenon that spans both technical and human aspects. As such, two disjoint areas have been studying the problem from separate angles: the information security community and the environmental criminology one. Despite the large body of work produced by these communities in the past years, the two research efforts have largely remained disjoint, with researchers on one side not benefitting from the advancements proposed by the other. In this paper, we argue that it would be beneficial for the information security community to look at the theories and systematic frameworks developed in environmental criminology to develop better mitigations against cybercrime. To this end, we provide an overview of the research from environmental criminology and how it has been applied to cybercrime. We then survey some of the research proposed in the information security domain, drawing explicit parallels between the proposed mitigations and environmental criminology theories, and presenting some examples of new mitigations against cybercrime. Finally, we discuss the concept of cyberplaces and propose a framework in order to define them. We discuss this as a potential research direction, taking into account both fields of research, in the hope of broadening interdisciplinary efforts in cybercrime research.

This paper explores how research in information security and environmental criminology can be integrated to develop more effective countermeasures against cybercrime. The two fields have traditionally worked independently, leading to a lack of cross-pollination between advancements made by each community. By examining the theories and systematic frameworks developed within environmental criminology, the paper aims to bridge these gaps, providing an overview of how these theories can be applied in the context of cybercrime.

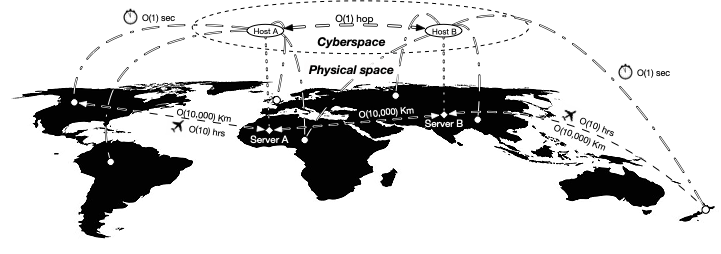

The study highlights that both information security experts and criminologists have been developing mitigation strategies for various aspects of cybercrime. However, by merging insights from both fields, new methodologies and frameworks can emerge to better understand and mitigate cyber threats. The paper presents a concept called “cyberplaces,” which defines the immediate environments where cybercrimes occur, thus offering a structured approach to analyze these crimes.

The significance lies in demonstrating that interdisciplinary collaboration between information security and environmental criminology can yield innovative solutions for preventing and managing cybercrime more effectively. This work encourages researchers to build upon this concept of “cyberplaces” to create systematic frameworks that guide practitioners in applying a wide range of preventive techniques.

We would like to thank all those who reviewed this work. Colin C. Ife is

supported by the Dawes Centre for Future Crimes, and EPSRC under grant

EP/M507970/1. Steven J. Murdoch is supported by The Royal Society under

grant UF160505.

The field of environmental criminology has been, for the most part,

primarily focused on crimes perpetrated in the physical world. On the

other hand, the information security community has been studying the

different facets of cybercrime for decades. Surprisingly, the parallel

between the mitigations proposed by the information security communities

and environmental criminology research was never made explicit. The

purposes of this section are threefold: (i) to give a general overview

of the cybercrime landscape and current mitigations; (ii) to draw

parallels between the mitigations proposed by the information security

community and the theoretical models of environmental criminology; and,

finally, (iii) to present some examples of new, potential mitigations by

applying environmental criminology

(Tables [table:new_mitigations]

and [table:new_malware_mitigations]),

which are at the end of this section.

Anonymous Marketplaces

With the ongoing rise in malware distribution, widespread data breaches,

and the unethical collection and use of personal data by various

corporations and governments, there has been widespread attention and

development towards privacy-enhancing technologies and regulations. One

such technology that has become prominent is the Tor anonymous

communication network. This encrypted network is resistant to common

Internet tracking methods and enables users (who utilise it correctly)

to effectively remain anonymous from all but the most technically

capable adversaries. There are legitimate purposes for such a

technology: users reading about sensitive topics, those with suppressed

rights to freedom of expression, journalism, whistleblowing, or those

who object to targeted advertising. Unfortunately, however, this

anonymity has also been exploited to hide criminal activities, such as

the trafficking of drugs, child sexual abuse images, violent

pornography, and weapons. Even worse, underground forums and anonymous

marketplaces (Silk Road) have arisen, enabling the convenient trade of

such illicit products and services. Researchers have also observed the

rise of ‘crimeware-as-a-service’ (CaaS) models along with these

“underground markets”. These criminal business models help to make

cybercriminal operations (spam delivery, malware distribution, drug

trafficking, money laundering) much more organised, automated, and

accessible, especially for criminals with limited technical skills .

Such business models have been made possible because cybercriminals can

network with each other on these underground services and exploit

various outsourcing opportunities.

Mitigations: The primary methods of intervention towards illegal

anonymous markets are server takedowns and arresting its operators.

These approaches were seen in law enforcement’s takedown of the infamous

Silk Road marketplace in 2013, which, at the time, was nearly a

monopoly. However, researchers have found that many more and diverse

anonymous marketplaces have come to prominence since the takedown of

Silk Road, with some (Silk Road 2.0) arising in less than a month. There

is evidence of adaptation by these new marketplaces and their patrons,

such as the increased use of encryption and decentralised escrow

services , and the diversification or specialisation in the types of

products and services offered . These changes mirror the well-known

criminological mechanisms of crime displacement (the net movement of

crime elsewhere as a result of an intervention) and crime adaption

(cybercriminals altering their operations in order to bypass an

intervention), which are potential, undesirable side effects of some

interventions.

Cryptocurrencies

Decentralised cryptocurrencies have gained significant traction over the

past decade, with Bitcoin being the first and most widely used

cryptocurrency. Bitcoin offers pseudonymity to its users, where accounts

are not necessarily linked to real-world identities, but transaction

details are publicly available in the distributed ledger. Other

cryptocurrencies, such as Zcash, are designed for full anonymity . Such

properties are attractive to cybercriminals , making cryptocurrencies

popular for illegal activities, like purchasing illicit goods and

services , and enabling ransomware extortion , digital theft , and

cryptocurrency laundering . Kamps and Kleinberg identified that

cybercriminals take advantage of the unregulated nature of some

cryptocurrencies to engage in “pump-and-dump” schemes. This scheme is a

type of fraud that involves three stages: accumulating a specific

cryptocurrency coin, increasing its perceived value through

misinformation (pumping), then selling it off to unsuspecting buyers at

a premium price (dumping).

Mitigations: Researchers such as Meiklejohn and Harlev have

devised techniques that can, to some extent, de-anonymise the operators

of Bitcoin transactions. Such techniques are especially useful for crime

investigation and are similar to geographic profiling , which involves

connecting locations in a series of crimes by an offender in order to

locate their “anchor point” (their home). These are also practical

implementations of the ‘reducing anonymity’ situational crime

prevention (SCP) technique, which increases the risks for cybercriminals

by exposing their identities. With regards to pump-and-dump schemes,

Kamps and Kleinberg devise an anomaly detection technique in order to

identify these schemes within time-series data of the trading prices and

volumes of different cryptocurrencies. However, with an ever-increasing

number of cryptocurrencies coming to the fore, and some that enable

greater anonymity, it is clear that new approaches are needed to detect

and discourage these sorts of criminal activities.

Cyberbullying and Online Abuse

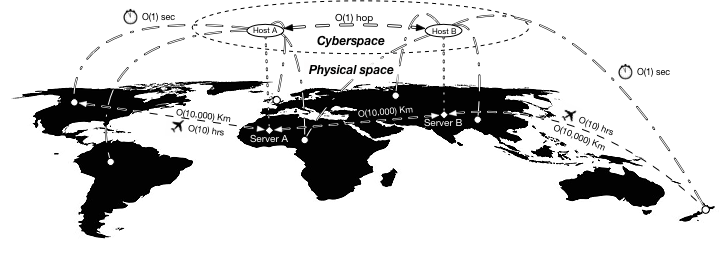

With the advent of computer and networked technologies, the rapid

adoption of the Internet has enhanced the abilities of end-users to

perform their daily interactions – communicating, purchasing and selling

products, exchanging information, working, and engaging in leisurely

activities – without the limiting restrictions of time and space.

Likewise, there has also been an increase in criminal opportunity

through such technologies, thus enabling and (potentially) multiplying

crimes that traditionally relied on physical, human-to-human

interaction.

Studies have followed the physical-digital transition of such

interpersonal crimes and antisocial behaviour, like cyberbullying ,

cyberstalking and cyberharassment , online hate speech , and online

child sexual exploitation and sexual harassment . These are only a few

types of the crimes that have gained traction from such shifts in

technology and society.

Mitigations: The default mechanisms for dealing with online abuse

(in its many forms) typically involve reporting abusive or offensive

content (and their authors) to the relevant service moderators (or

utilising place managers from an SCP perspective). In extreme cases,

such as the commission of violent threats, online sexual harassment, or

child sexual abuse images, one may report such behaviours to the police.

Although such actions can be useful, they are inherently reactive and

often vulnerable to reporter biases (opinions of inappropriacy, cultural

differences) or false reporting, and are probably less effective in

preventing future occurrences . Researchers such as Ioannou , advocate

the need for a proactive and multidisciplinary approach to dealing with

online abuse. Even automated filters, which ought to blacklist hate

speech and offensive language, are limited, as in they rely on

predefined dictionaries of words. Such dictionaries are also inherently

reactive and are inflexible towards misspellings and evolving language .

Consequently, researchers have developed some proactive techniques for

mitigating these crimes.

Mariconti develop a supervised machine learning approach to

automatically determine whether a YouTube video is likely to be

“raided”, to receive sudden bursts of hateful comments. Serra propose

a text classification algorithm using class-based prediction errors in

order to more effectively detect evolving and misspelt hate speech.

Chatzakou develop a system that automatically detects bullying and

aggressive behaviour on Twitter, using text, user, and network-based

attributes. Founta present a holistic approach to automated abuse

detection by supplying deep learning architectures with text and

metadata-based inputs. Yiallourou devise a methodological approach

that can be used to support the automated detection of images containing

child-pornographic material. The successes of such surveillance

strengthening techniques, which are indeed subsets of risk-increasing

SCP techniques, are likely to increase the risk of getting caught for

offenders and are just some of the multidisciplinary ways to deal with

such problems. Of course, other forms of countermeasures exist. For

example, the impersonation of minors by law enforcement has been shown

to be effective in apprehending offenders, while automated chatbots are

being developed to profile potential offenders . There is also the

arrest and prosecution of the worst offenders . Educating minors and

Internet users to avoid online abuse victimisation is also an important,

long-term initiative .

Cyber Fraud

Fiancial crime and fraud have also made a paradigm shift into the cyber

world. The phenomenon of advance-fee fraud, or “419” scams

(cybercriminals reaching out to potential victims with grandiose

promises of wealth in exchange for advanced payments from them) have

been well-documented by researchers . Recent works have found such scams

are more of a universal issue than once thought , rather than being one

that only involves less economically developed countries. Cybercriminals

have also been known to target other services for fraudulent activities,

depending on their demographics of interest. For example, “419” scams

are likely to be delivered en masse through spam e-mail communications,

where gullible recipients would self-identify themselves by responding

to these e-mails . Romance scammers are likely to operate on dating

websites in order to manipulate emotionally vulnerable users . Consumer

fraudsters are likely to target large online marketplaces to commit

buyer or seller fraud . Various forms of identity fraud, facilitated

through Internet-enabled theft of personally identifiably information

(PII) (names, addresses, e-mail addresses) or account credentials for

common services (e-mail, banking, social media) are also problems that

the information security community closely monitor. Researchers have

recognised that phishing e-mails and malware are common precursors to

identity fraud , and they have monitored the illegal activities that

subsequently ensue with such credentials .

Mitigations: The effective prosecution of scammers is necessary but

often difficult due to the transnational nature of these operations and

the relatively small amounts of money involved per fraud. Some

engineering countermeasures are in use, such as the use of spam or

phishing filters to prevent malicious messages reaching recipients, or

blacklists that raise alerts or block known phishing websites. However,

the maintenance of such measures is a continual arms race, as

cybercriminals are always adapting these spam messages or compromising

new websites to avoid these blockers. It is possible for services to

automatically detect scammer profiles, such as by their reuse of profile

descriptions or profile photos . On the other hand, perpetrators could

also adapt to such countermeasures with ease. Arguably, the most

effective countermeasures could be to reduce the profitability, or

increase the required effort, for such crimes. An economic strategy,

such as increasing the transaction fees or the necessary background

checks for money transfer services, could be a set of mitigations that

attack the profitability of such crimes. Awareness campaigns could also

help to reduce the opportunity for victimisation, but perhaps more so if

these campaigns are directed towards the most vulnerable, as identified

by their personality types and victimisation statistics . With regards

to environmental criminology, these are recognised as market

disrupting and target removing SCP techniques, which involve reducing

the rewards of crime by denying criminals the ability to steal, sell, or

access a target.

Malware and Botnet Operations

One area of focus in the information security community is the study of

malicious software – malware. The issue of malware came into prominence

in the 1980s, but in recent times, it has become a massive underground

economy. In short, financial motivations (above others) have become a

cornerstone to the design and proliferation of modern malware.

Researchers have identified that modern strains typically carry a myriad

of functions, no doubt for the purposes of monetisation. Malware

families, such as Zeus , for example, can steal banking and financial

credentials on compromised machines, log keystrokes and extract

documents, or to encrypt victim computers to be held for ransom. Even

worse, some malware families are designed to retain control of

compromised devices in order to assimilate them into larger networks of

infected machines, or botnets. These botnets may be used (or rented

as-a-service) to facilitate distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks

against a target, to send spam e-mails , or to mine cryptocurrencies.

Malware distribution has been refined to infect as many viable victims

as possible. Initially, there was a heavy reliance on human activity and

manipulation, such as the need for victims to open spam e-mail messages

or to be social engineered into activating a malicious file . Nowadays,

cybercriminals have developed distribution mechanisms to completely cut

out the need for human interaction, such as delivering malware directly

through automated browser-based attacks (or drive-by download attacks)

via compromised websites or malvertisements . To ease the lives of

malware operators, the cybercrime ecosystem proceeded to come up with

exploit kits – software packages that deliver a wide variety of exploits

for different computer configurations . This innovation, ultimately,

increases the probability of a victim’s system becoming compromised. In

a further attempt to streamline malware delivery and lower the entry bar

for cybercriminals, pay-per-install (PPI) schemes have also arisen in

the cybercrime ecosystem . These services are specialised botnets of

infected devices that enable the distribution and download of new

malware onto these already compromised machines. PPIs are set up and

managed by a service provider, whom customers pay in order to infect

machines with their own proprietary malware.

The disruption of the malware distribution economy is an ongoing

challenge. Cybercriminals increasingly implement new and numerous

techniques in order to prevent their malware and botnets from being

detected and disabled. Researchers have found that malware often

obfuscates their outgoing communications, undergo polymorphism to

“change their appearances”, remain “silent” whenever they detect a

possible malware analysis environment, copy themselves to multiple

locations on a compromised machine, or distribute themselves over

multiple devices on a network . Botnet operators have also been found to

employ various tactics to avoid detection and takedown attempts of their

infrastructures, such as implementing fast-flux techniques (the rapid

rotation of IP addresses) , or domain generation algorithm techniques

(the constant changing of domain names) , to hide the locations of their

command and control servers.

Mitigations: The challenges of malware and botnet infrastructures

are as complex as their operations. First, there is the issue of

preventing malware infection and spread. Signature-based antivirus

programs have long been the major defence in detecting and removing

malware, along with intrusion detection systems and content filters.

However, they struggle with the extensive manner of forms that malware

now appears (polymorphic, metamorphic, compressed, encrypted, ).

Antivirus programs that use heuristic methods for malware removal are

now much more common (detection is based on abnormal program

behaviours). Notwithstanding, malware removal is still a reactive

strategy, so proactive measures have also been developed. One such is

the use of antimalware tools, which attempt to prevent malware attacks

in the first instance through methods such as malware sandboxing,

raising browser alerts on suspicious websites, and preventing the spread

of malware if a device is infected. Another proactive approach is

vulnerability assessment and management, which deals with providing

regular system updates in order to remove known vulnerabilities. Such

updates would reduce the success of drive-by download attacks, for

example, thus minimising one’s attack surface for malicious actors to

exploit. Both of these techniques are akin to target hardening that is

applied in SCP and CPTE/UD frameworks, which aim to increase the

difficulty of an attacker gaining access to their target. Although

malware delivery is not completely dependent on human error, this role

is still substantial. Educating users to keep their systems up-to-date

and on how to avoid social engineering attacks are some non-technical

approaches that are also applied, such as with Action Fraud and their

#UrbanFraudMyths.

Second, there is the issue of disrupting botnet operations. One

important technique involves the infiltration of botnets by security

researchers . Such techniques allow researchers to collect intelligence

on cybercriminal operations, and identify weak points in their

communication protocols for disruption, or locating their C&C servers

for ISP takedowns. They may also be used to identify the owners of these

botnets, such that law enforcement may arrest and prosecute them.

However, with the estimates of Kaspersky Lab indicating there could be

hundreds of thousands of botnets in the wild, it is difficult to see the

scalability of these techniques. Alternatively, service providers may

provide some mitigations. For example, e-mail programs and social

networking sites usually employ spam filters, which may consequently

deter spam operations. However, these filters are often signature-based,

so minor adjustments in the spam messages may cause them to go

undetected. ISPs may use DNS sink-holing techniques and blacklists to

prevent their customers from accessing sites known to be malicious.

However, such techniques also come under the “arms race” issue of

keeping up with the cybercriminals. Other economic measures are

possible, such as pressuring ISP services to dissociate from

“bulletproof ISPs”, which resist law enforcement and typically harbour

these criminal activities, or pressuring financial institutions to

dissociate from rogue banks, which liaise with cybercriminals, in order

to effectively shut down their operations. Environmental criminology

recognises these as market disrupting techniques (SCP), which aim to

reduce the economic benefits of such operations until they are no longer

viable.

Using the SCP framework, a proof-of-concept matrix of potential

mitigations for disrupting malware operations is provided in

Table [table:new_malware_mitigations].

A Synergistic Approach

Though there are already clear parallels between the theoretical models

of environmental criminology and the mitigative techniques proposed by

information security, security researchers are yet to fully explore the

structured analytical and actionable processes that environmental

criminology has to offer. Firstly, past and current mitigations devised

by security researchers only seem to represent or consider a subset of

the full range of techniques that could be utilised, while lacking a

systematic approach to establish these. Secondly, little attention seems

to be directed towards the consideration, monitoring, and evaluation of

the actual effects of interventions by security researchers, both with

regards to the victims/targets and the malicious actors, and how they

respond. Ultimately, without considering the fulness of the crime

prevention process, mitigations are more likely to fail (to different

degrees) in the goal of controlling crime in both the short- and

long-term, as cybercriminals may quickly identify alternative targets,

crime types, or modus operandi.

Conclusion

In this paper, we conducted a literature review of cybercrime research

from the perspectives of information security and environmental

criminology. We presented an overview of how these two fields understand

and (could) deal with cybercrime, identifying connections between their

apparently disparate approaches. Upon review of a wide array of

literature and cybercrime contexts, we provide motivating evidence as to

why a new, complementary research approach should be pursued involving

these two fields. We initiate this process in earnest, first, by showing

how frameworks from environmental criminology could be used to devise

new cybercrime countermeasures; second, by proposing a conceptualisation

of the immediate environmental contexts (or cyberplaces) where

cybercrimes occur; and third, by providing some motivating examples of

how the concept of cyberplaces, together with environmental criminology,

could be used to better analyse and mitigate cybercrime. We hope that

this work will encourage the wider research community to build upon this

cyberplace concept and its implementation in the transfer of crime

prevention theories and frameworks between environmental criminology and

information security. Above all, we hope that such collaborations will

yield new and better approaches to cybercrime prevention and provide

systematic frameworks that inform practitioners on the full range of

techniques available.

Cybercrime is a complex phenomenon that spans both technical and human

aspects. As such, two disjoint areas have been studying the problem from

separate angles: the information security community and the

environmental criminology one. Despite the large body of work produced

by these communities in the past years, the two research efforts have

largely remained disjoint, with researchers on one side not benefitting

from the advancements proposed by the other. In this paper, we argue

that it would be beneficial for the information security community to

look at the theories and systematic frameworks developed in

environmental criminology to develop better mitigations against

cybercrime. To this end, we provide an overview of the research from

environmental criminology and how it has been applied to cybercrime. We

then survey some of the research proposed in the information security

domain, drawing explicit parallels between the proposed mitigations and

environmental criminology theories, and presenting some examples of new

mitigations against cybercrime. Finally, we discuss the concept of

cyberplaces and propose a framework in order to define them. We discuss

this as a potential research direction, taking into account both fields

of research, in the hope of broadening interdisciplinary efforts in

cybercrime research.

The copyright of this content belongs to the respective researchers. We deeply appreciate their hard work and contribution to the advancement of human civilization.