Putting Probabilities First How Hilbert Space Generates and Constrains Them

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Putting probabilities first. How Hilbert space generates and constrains them- ArXiv ID: 1910.10688

- Date: 2021-08-10

- Authors: Michael Janas and Michael E. Cuffaro and Michel Janssen

📝 Abstract

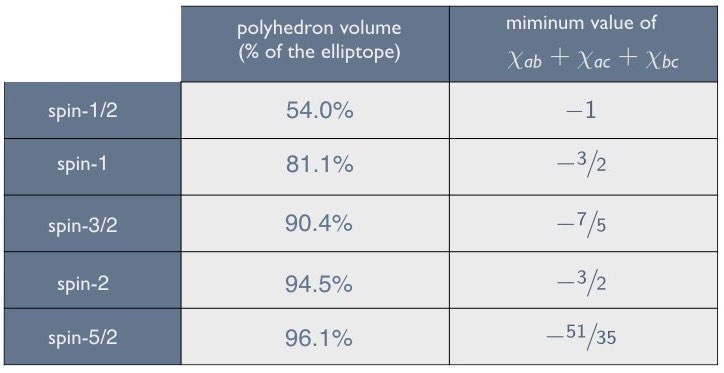

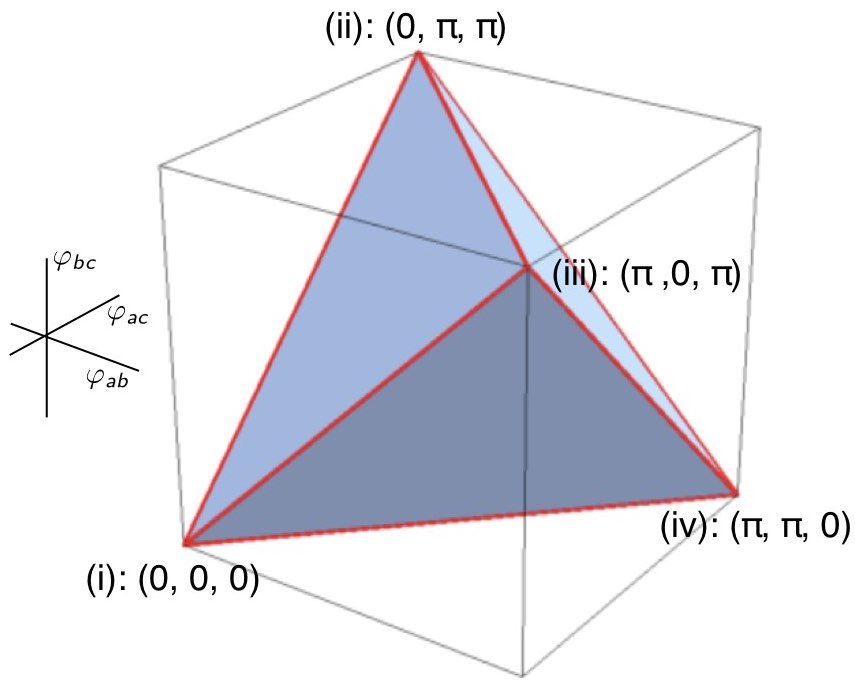

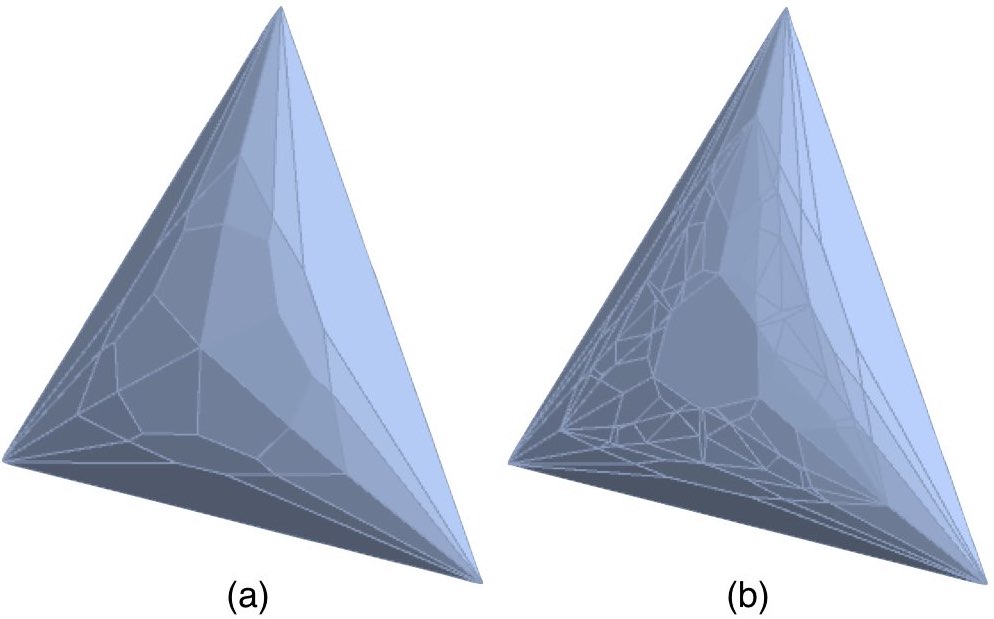

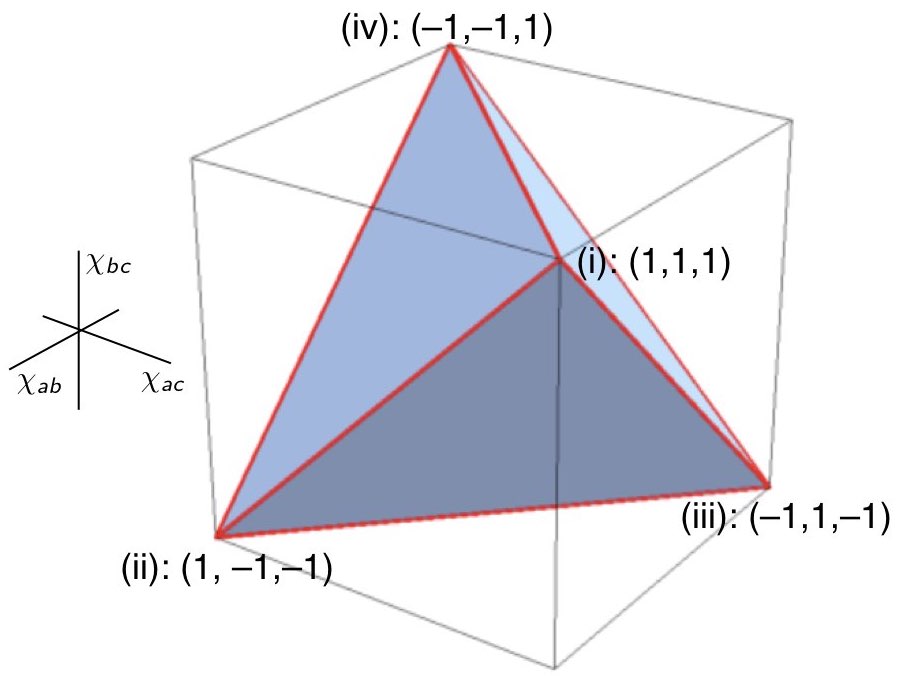

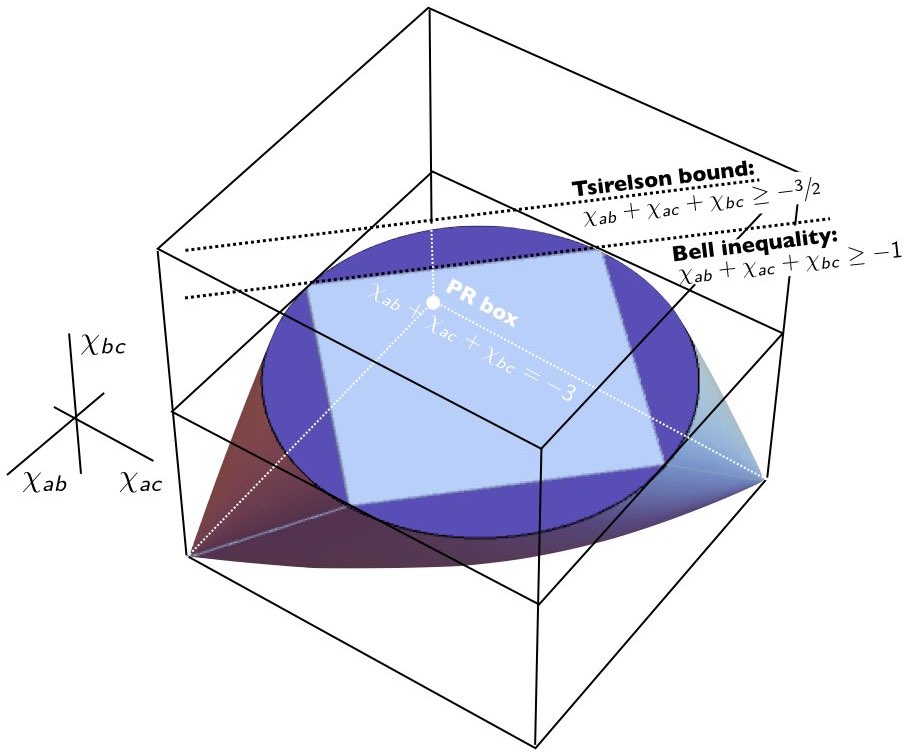

We use Bub's (2016) correlation arrays and Pitowksy's (1989b) correlation polytopes to analyze an experimental setup due to Mermin (1981) for measurements on the singlet state of a pair of spin-$\frac12$ particles. The class of correlations allowed by quantum mechanics in this setup is represented by an elliptope inscribed in a non-signaling cube. The class of correlations allowed by local hidden-variable theories is represented by a tetrahedron inscribed in this elliptope. We extend this analysis to pairs of particles of arbitrary spin. The class of correlations allowed by quantum mechanics is still represented by the elliptope; the subclass of those allowed by local hidden-variable theories by polyhedra with increasing numbers of vertices and facets that get closer and closer to the elliptope. We use these results to advocate for an interpretation of quantum mechanics like Bub's. Probabilities and expectation values are primary in this interpretation. They are determined by inner products of vectors in Hilbert space. Such vectors do not themselves represent what is real in the quantum world. They encode families of probability distributions over values of different sets of observables. As in classical theory, these values ultimately represent what is real in the quantum world. Hilbert space puts constraints on possible combinations of such values, just as Minkowski space-time puts constraints on possible spatio-temporal constellations of events. Illustrating how generic such constraints are, the equation for the elliptope derived in this paper is a general constraint on correlation coefficients that can be found in older literature on statistics and probability theory. Yule (1896) already stated the constraint. De Finetti (1937) already gave it a geometrical interpretation.💡 Summary & Analysis

This paper explores the fundamental differences between quantum mechanics and classical theories through a detailed analysis of correlation structures using Bub's correlation arrays and Pitowsky's correlation polytopes. The study focuses on Mermin’s experimental setup for measurements on pairs of spin-$\frac{1}{2}$ particles in their singlet state. Quantum mechanical correlations are represented by an elliptope within a non-signaling cube, while classical local hidden-variable theories correspond to a tetrahedron inscribed within this elliptope.The authors extend the analysis to arbitrary spins and find that quantum mechanics continues to be described by the same elliptope, whereas the polyhedra representing local hidden-variable theories grow more complex but increasingly approximate the elliptope. This work supports an interpretation of quantum mechanics where probabilities and expectation values are primary, determined by inner products in Hilbert space.

The key insight is that while classical probability spaces require joint distributions for all variables to be defined, quantum mechanics can assign values to sums of observables without specifying individual values, allowing it to saturate the volume of the elliptope. This highlights a fundamental kinematical difference between quantum and classical theories, rooted in how they handle probabilities and correlations.

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

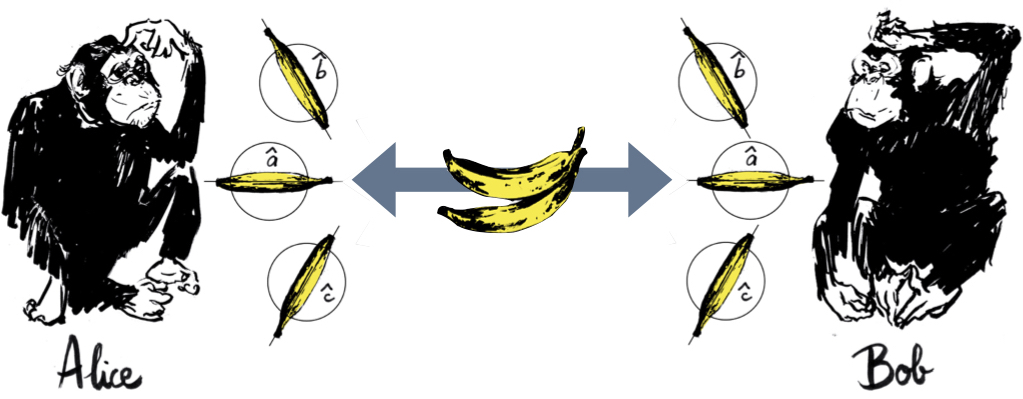

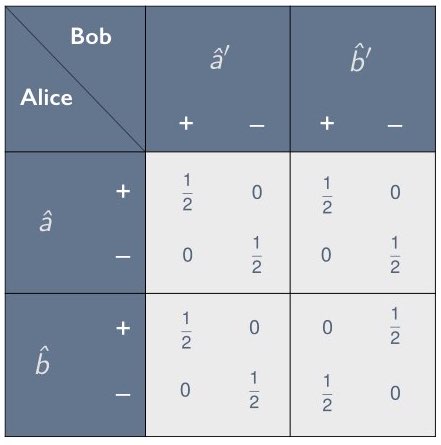

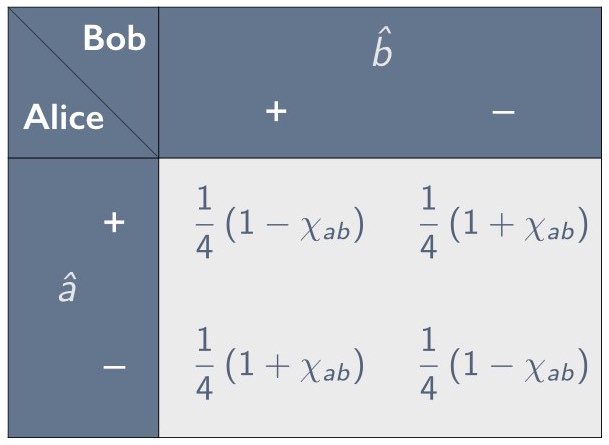

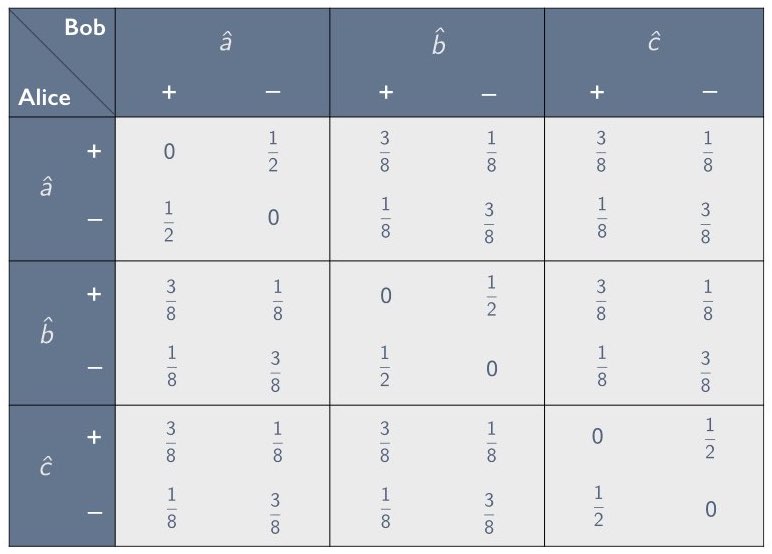

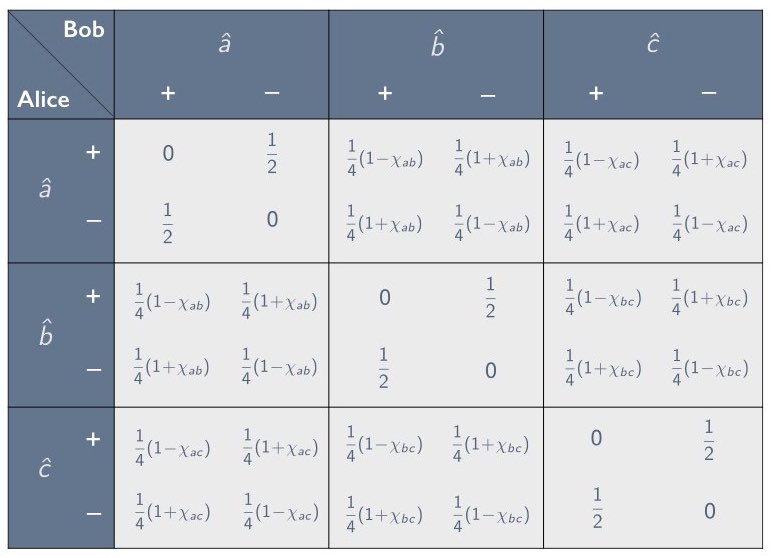

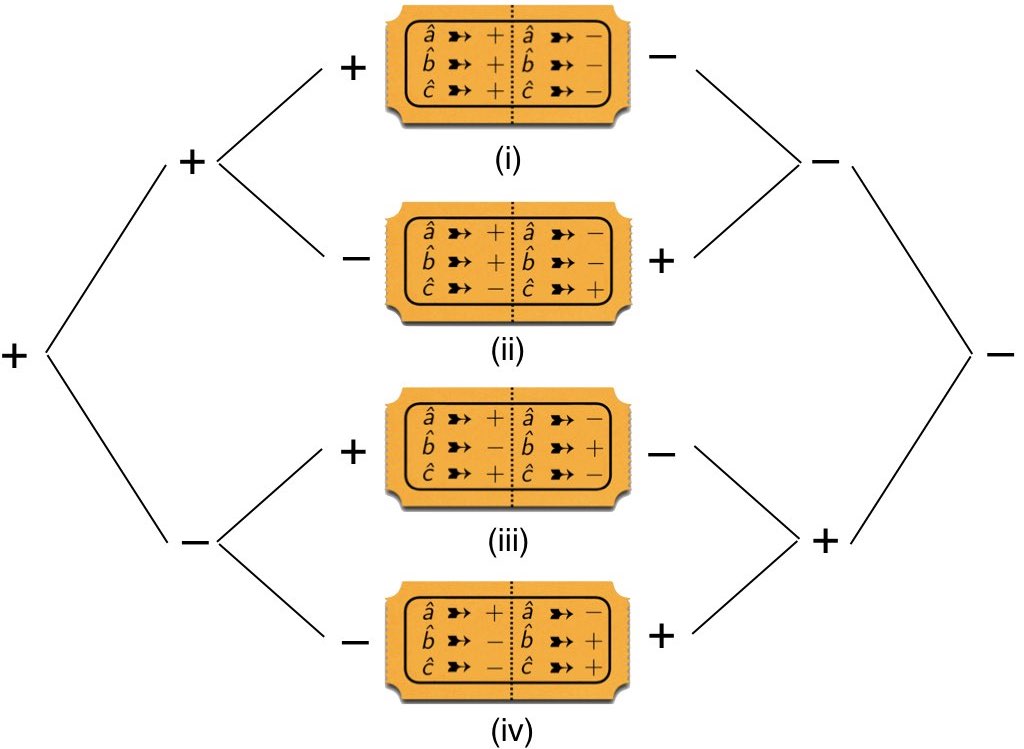

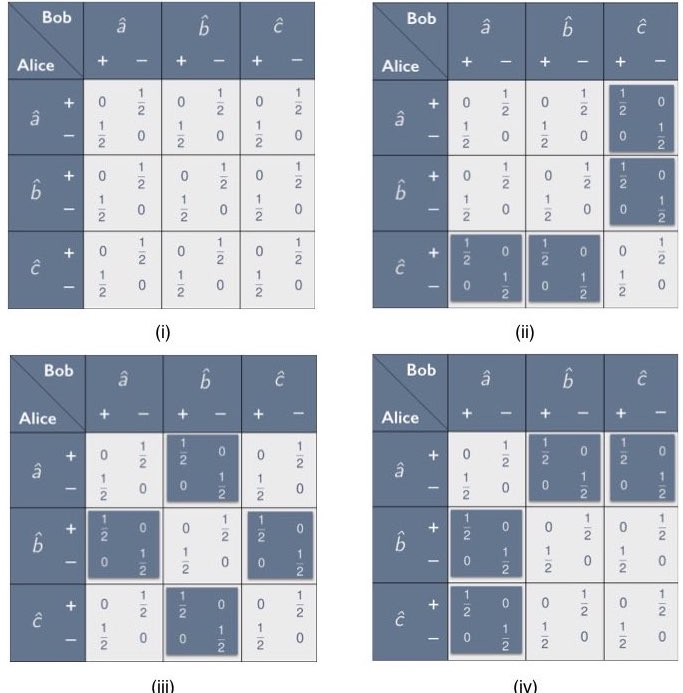

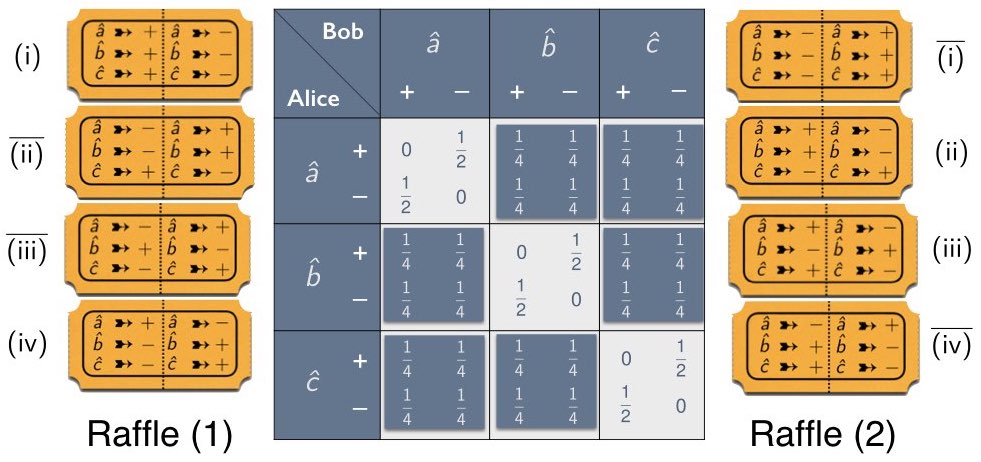

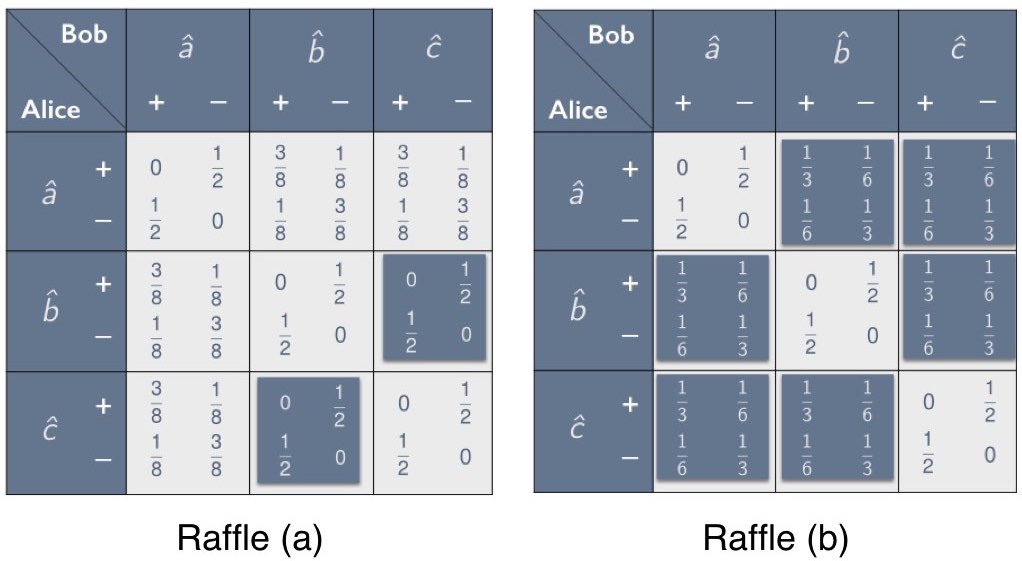

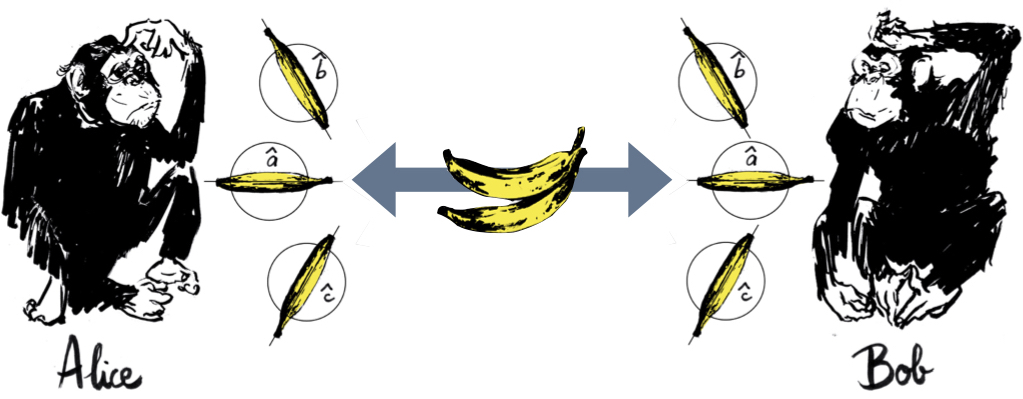

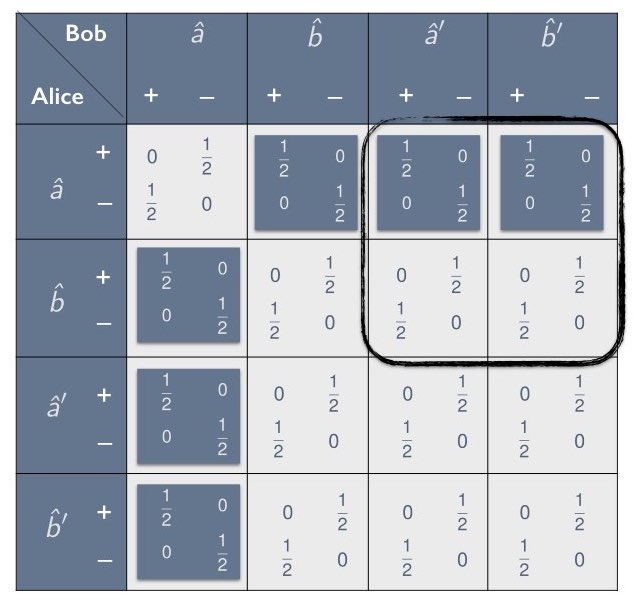

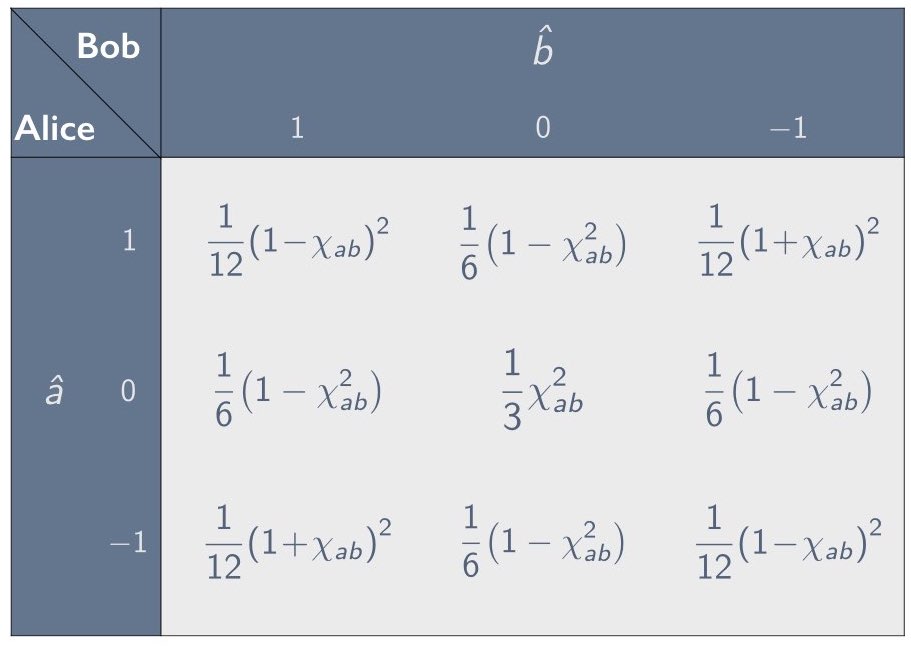

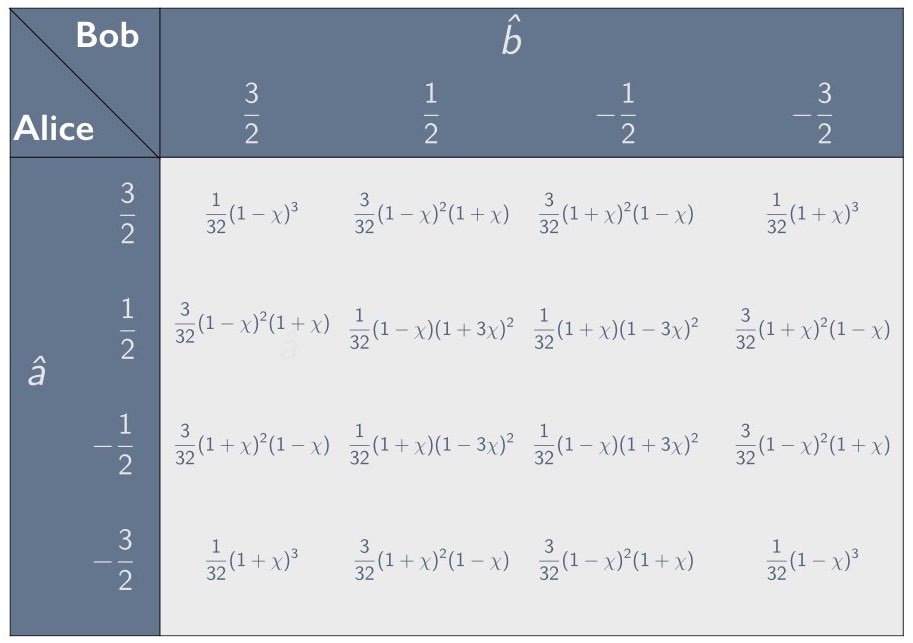

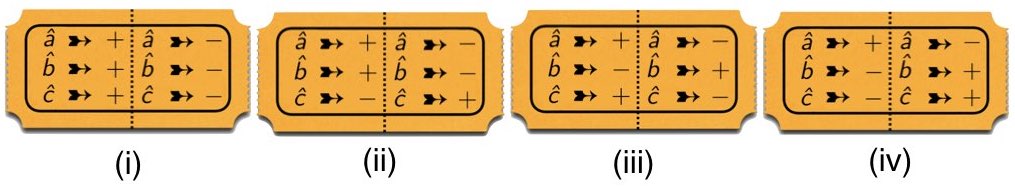

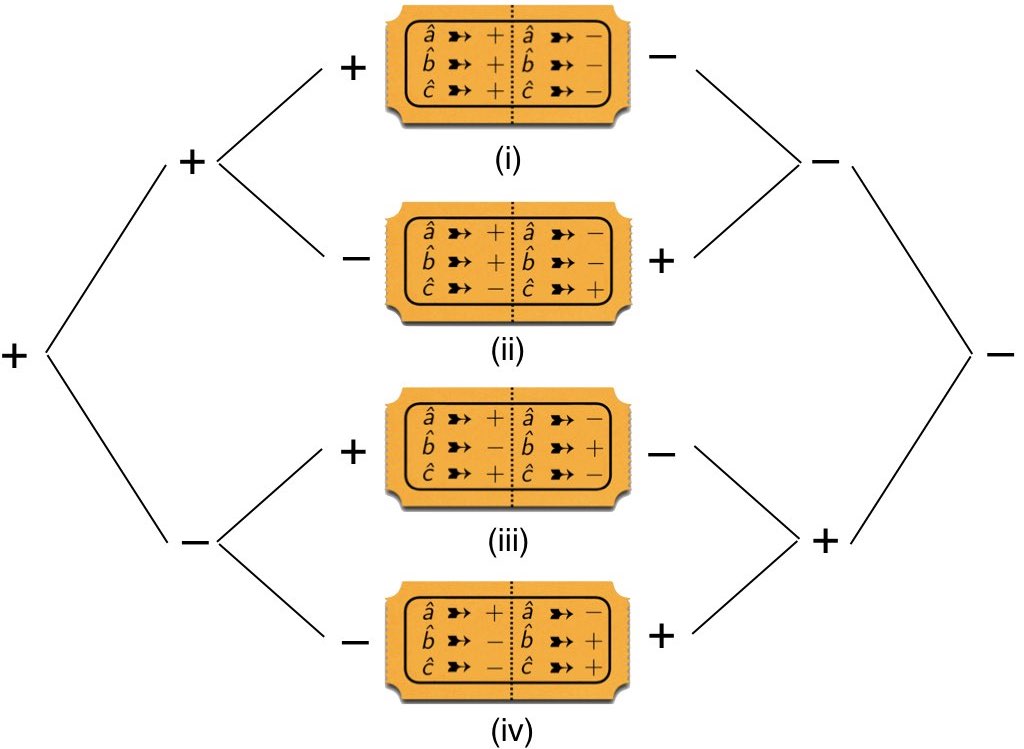

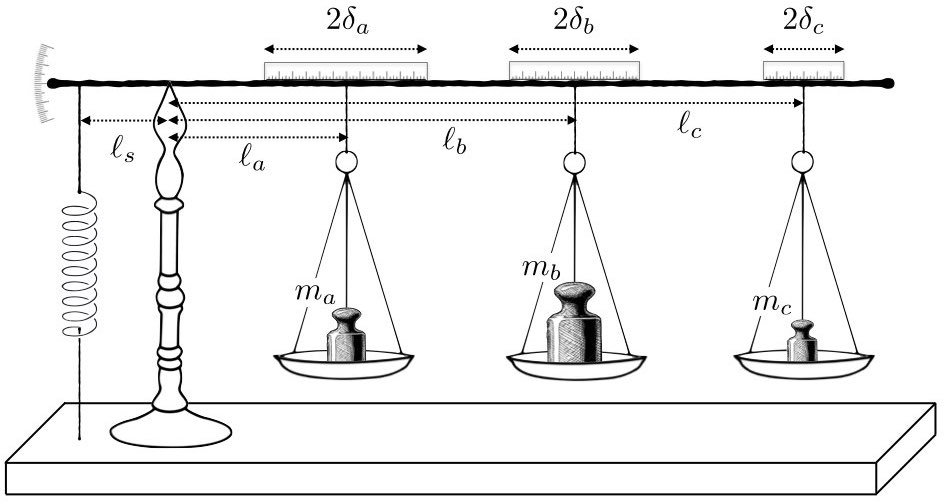

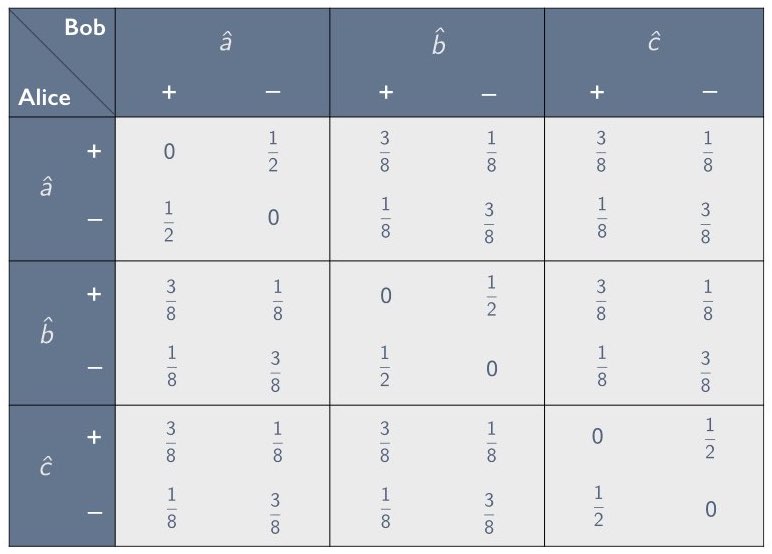

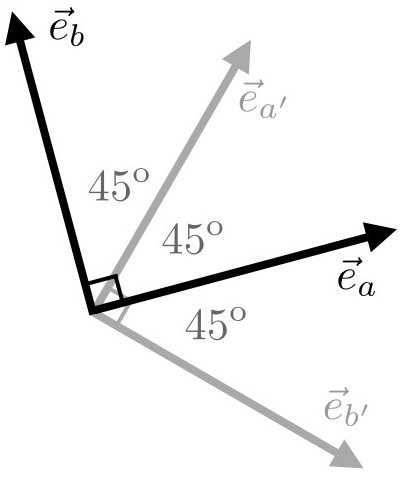

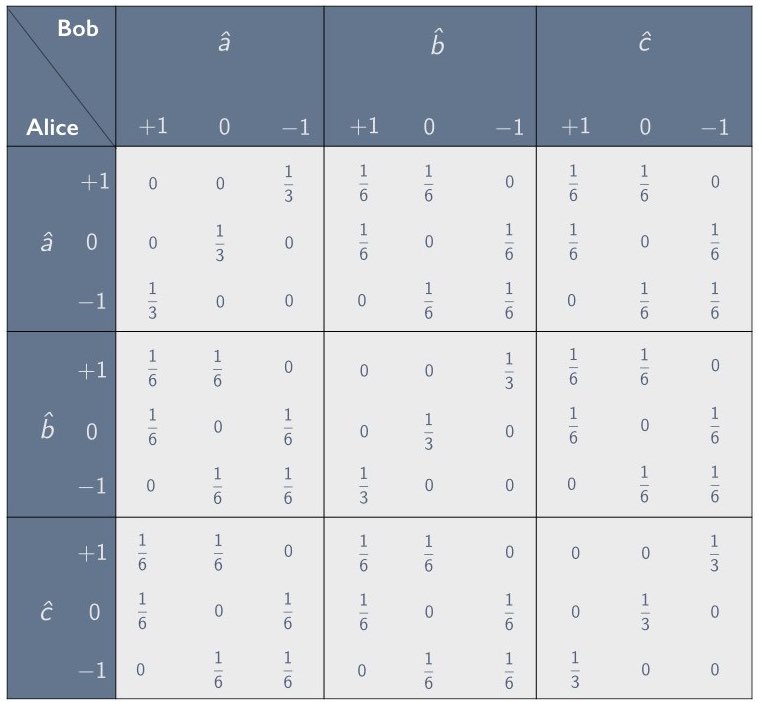

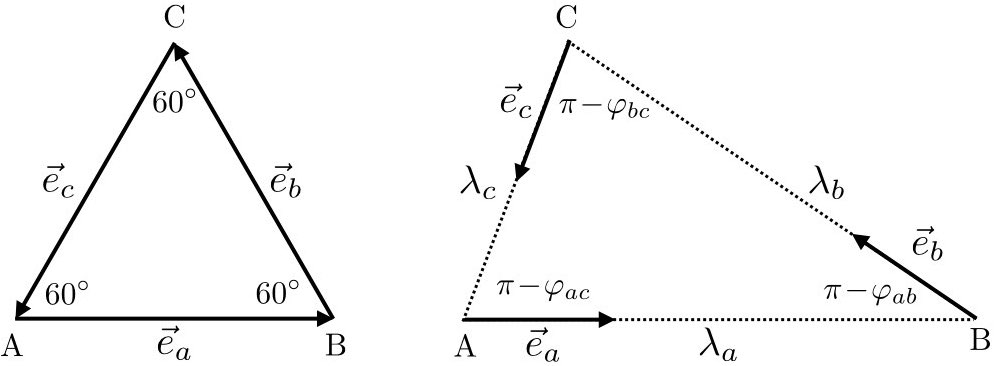

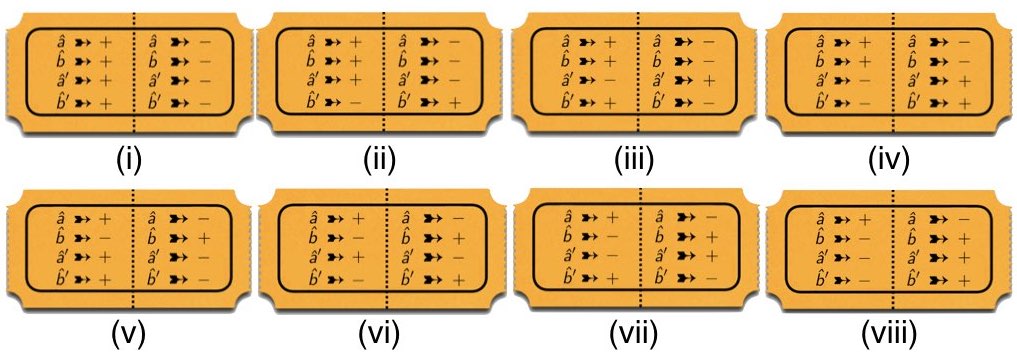

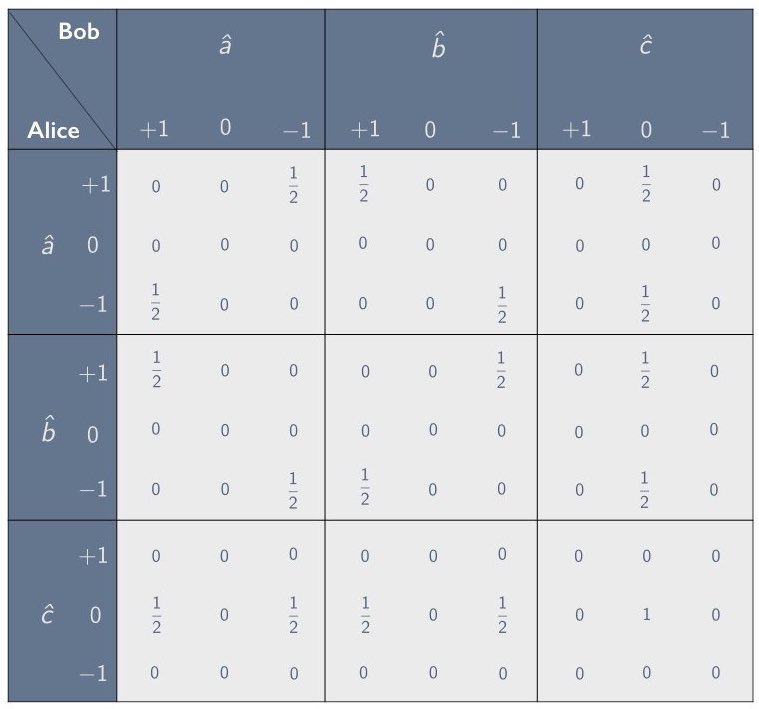

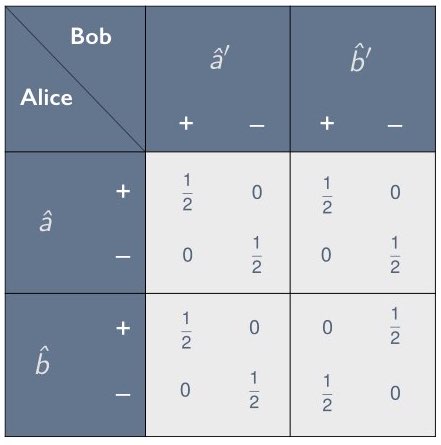

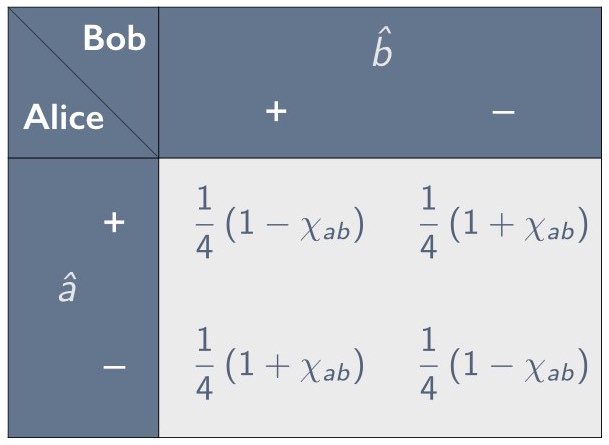

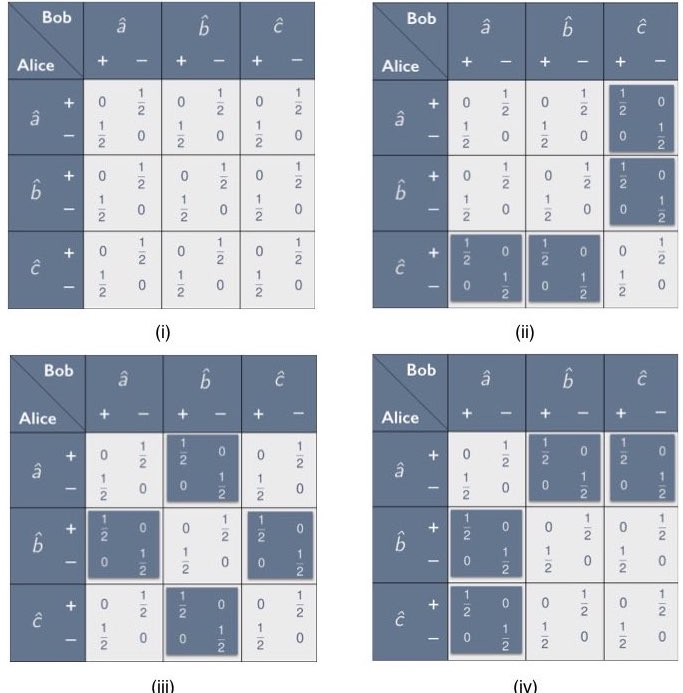

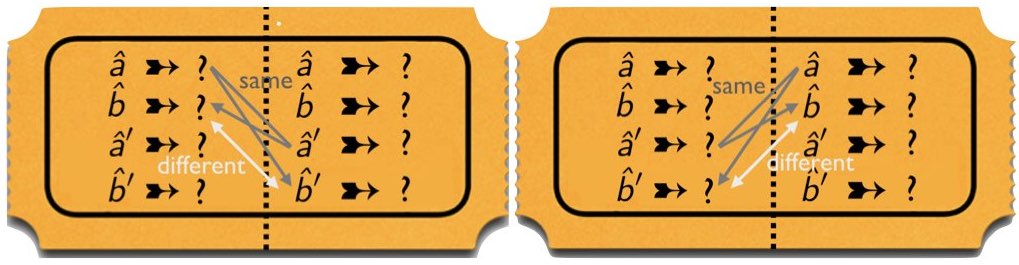

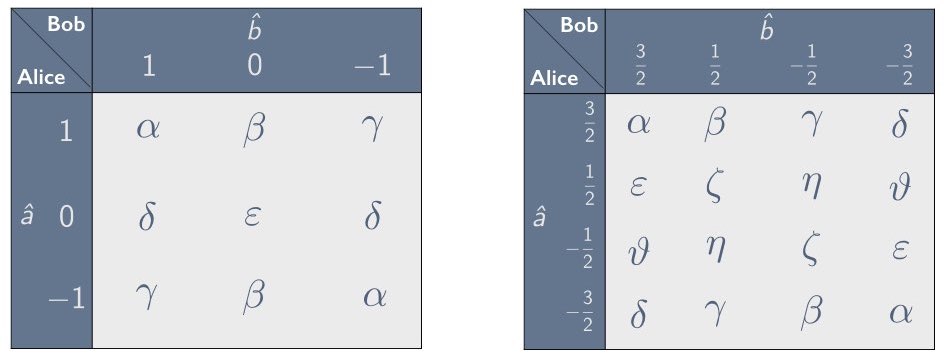

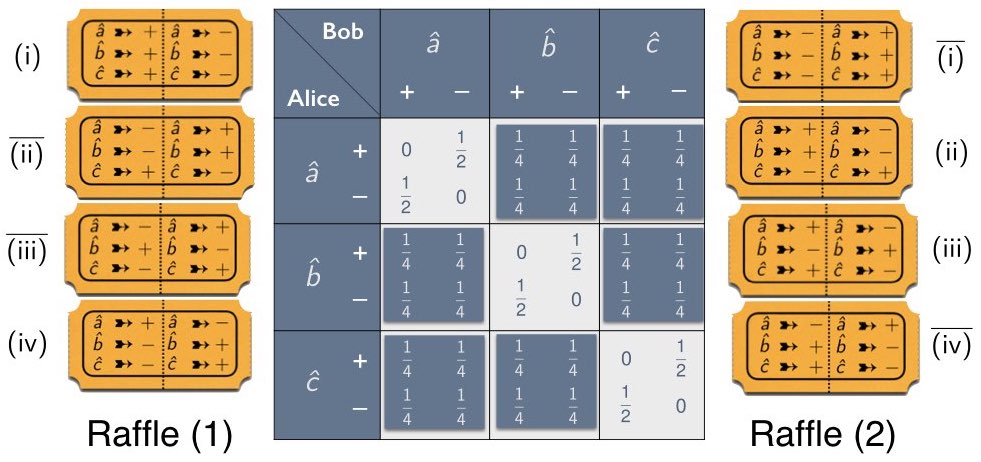

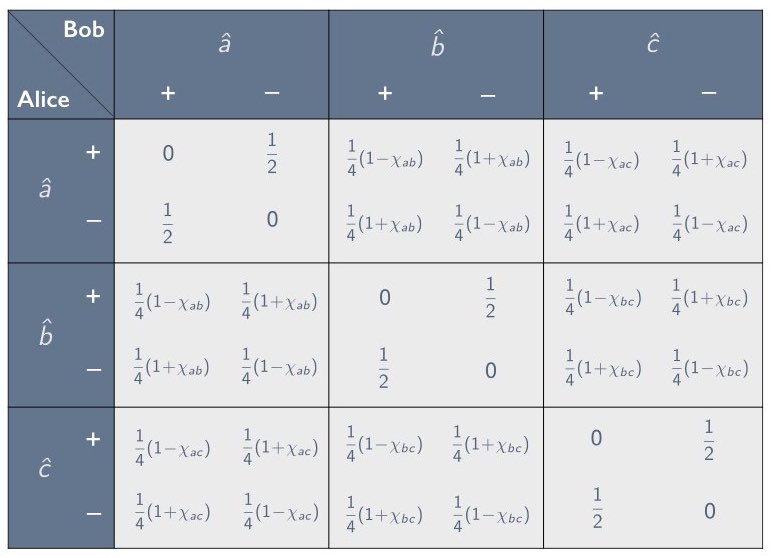

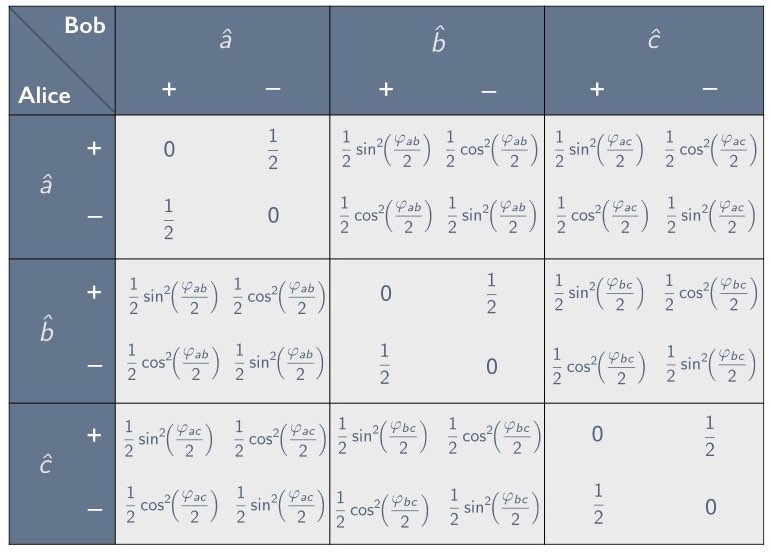

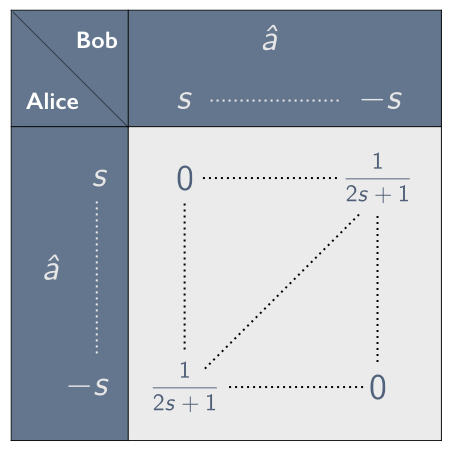

In Section 2 we introduced the concept of a correlation array—a concise representation of the statistical correlations between separated parties in the context of a given experimental setup. We focused primarily on setups involving two parties, Alice and Bob, who are each given one of two correlated systems and are asked to measure them using one of the three settings $`\hat{a}`$, $`\hat{b}`$ and $`\hat{c}`$. Such a setup can be characterized using a 3$`\times`$3 correlation array in which each cell corresponds to one of the nine possible combinations for Alice’s and Bob’s setting choices. In Section 2.3 we showed how to parameterize the cells in such a correlation array by means of an anti-correlation coefficient, defined as the negative of the expectation value of the product of Alice’s and Bob’s random variables, divided by the product of their standard deviations (see Eq. [chi as corr coef]). For example, when there are two possible outcomes per measurement, a symmetric 3$`\times`$3 correlation array with zeroes along the diagonal can be parameterized using three anti-correlation coefficients $`\chi_{ab}`$, $`\chi_{ac}`$ and $`\chi_{bc}`$, as depicted in Figure 7. One of the correlation arrays describable in this way is the correlation array for the Mermin setup given in Figure 6.

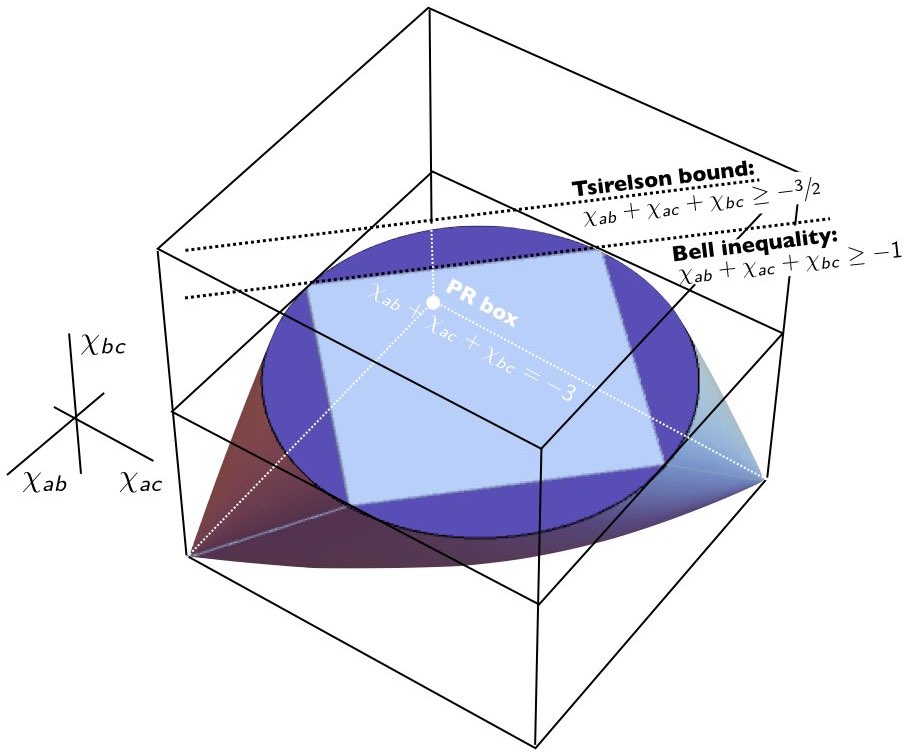

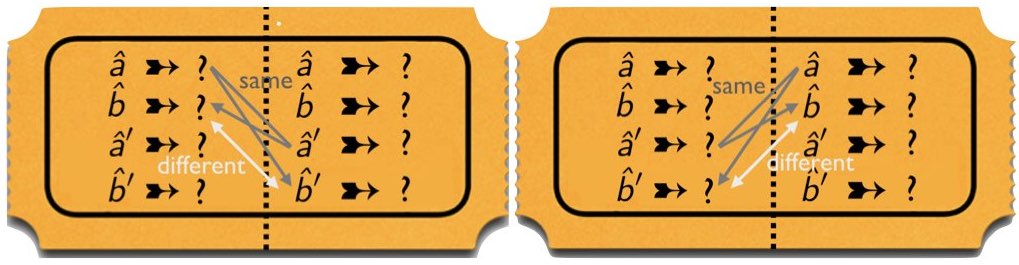

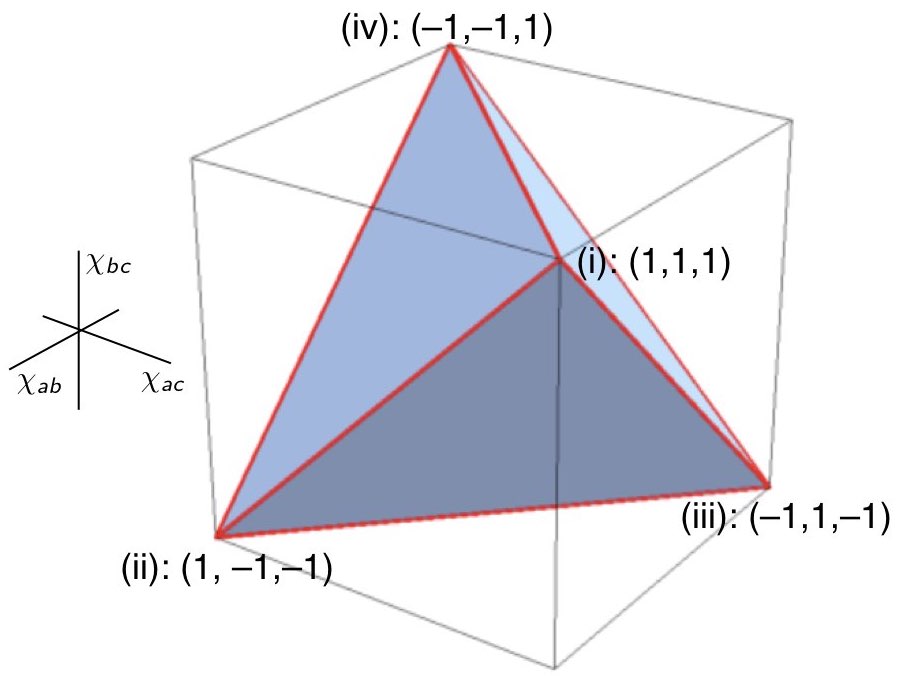

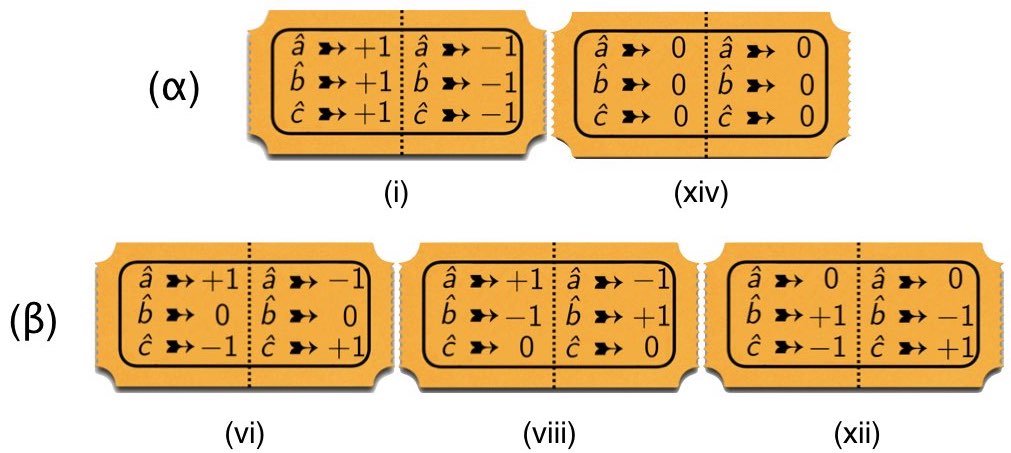

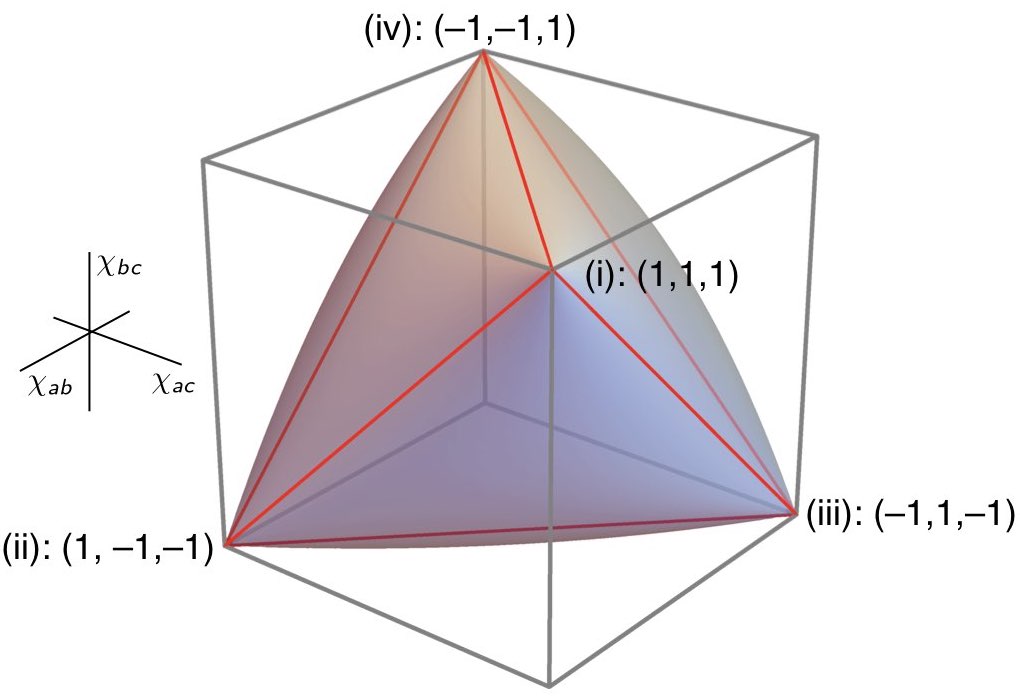

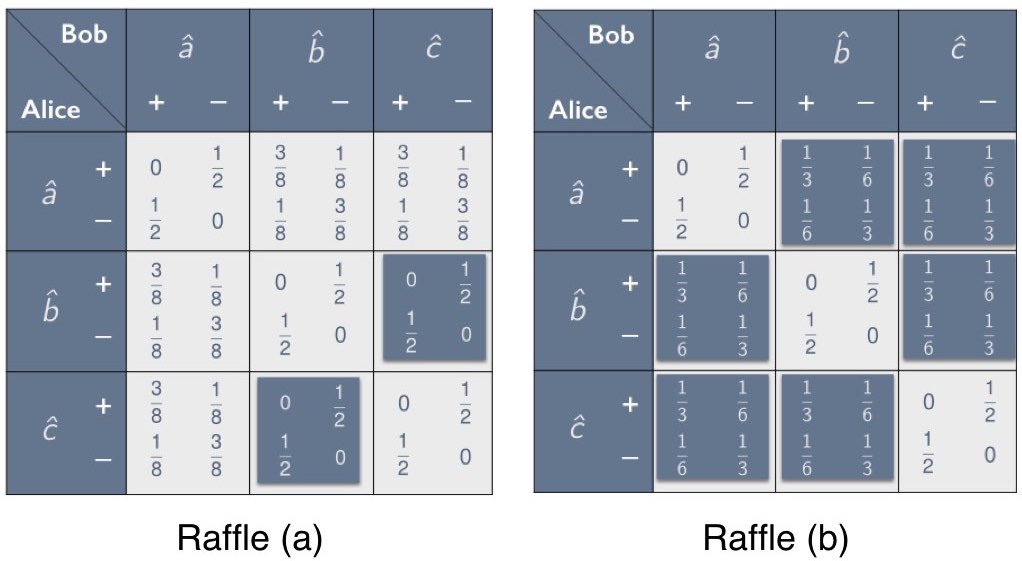

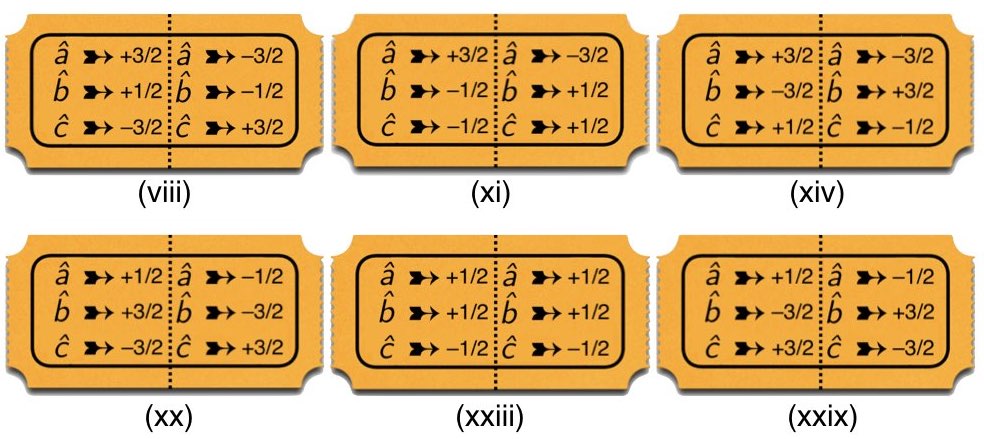

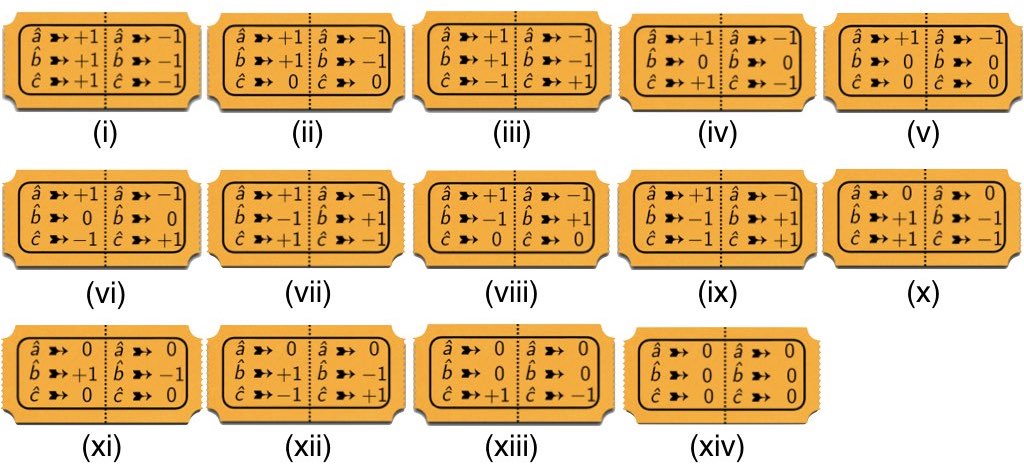

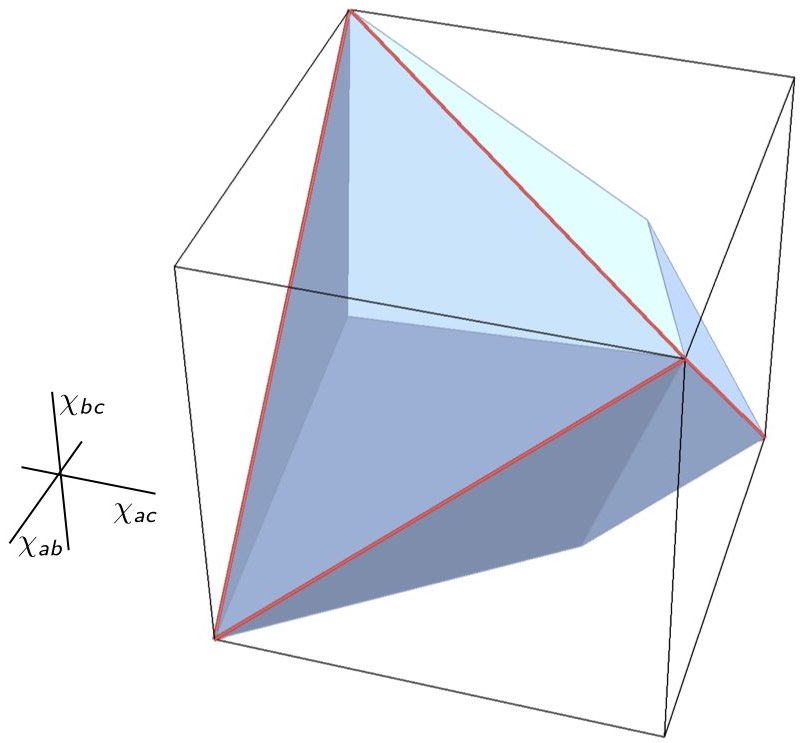

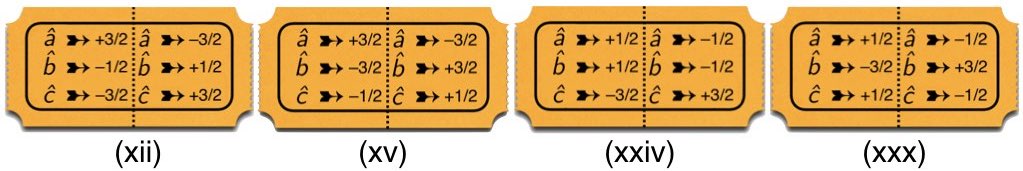

We considered local-hidden variable models for 3$`\times`$3 correlation arrays of this kind in Section 2.4. We imagined, in particular, modeling such arrays with mixtures of raffle tickets like the ones in Figure 10, and for such models we derived the following constraints on the anti-correlation coefficients $`\chi_{ab}`$, $`\chi_{ac}`$ and $`\chi_{bc}`$:1

\begin{align}

\label{repeatInequalities1}

-1 \leq \chi_{ab} + \chi_{ac} + \chi_{bc} \leq 3, \\[.3cm]

\label{repeatInequalities2}

-1 \leq \chi_{ab} - \chi_{ac} - \chi_{bc} \leq 3, \\[.3cm]

\label{repeatInequalities3}

-1 \leq \chi_{ab} + \chi_{ac} - \chi_{bc} \leq 3, \\[.3cm]

\label{repeatInequalities4}

-1 \leq \chi_{ab} - \chi_{ac} + \chi_{bc} \leq 3.

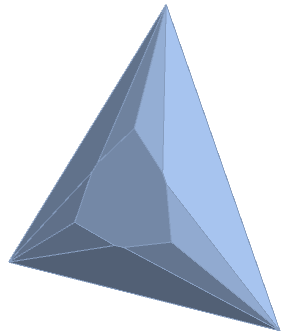

\end{align}Together these four linear inequalities are necessary and sufficient to characterize the space of possible statistical correlations realizable in any such model. This space can be visualized as the tetrahedron in Figure 14; i.e., for any given point $`(\chi_{ab}, \chi_{ac}, \chi_{bc})`$, it is contained in the convex set represented by the tetrahedron if and only if it satisfies all four of Eqs. ([repeatInequalities1]–[repeatInequalities4]). In Section 6.1 we showed that the convex set characterizing the allowable quantum correlations for 3$`\times`$3 setups of this kind is a superset of those allowed in a local-hidden variables model. It can be characterized by the non-linear inequality2

\begin{align}

\label{repeatElliptopeEqn}

1 - \chi^2_{ab} - \chi^2_{ac} - \chi^2_{bc} + 2\chi_{ab}\chi_{ac}\chi_{bc} \geq 0,

\end{align}whose associated inflated tetrahedron or elliptope is shown in Figure [elliptope].

Our work is both continuous with and extends that of Pitowsky. Pitowsky, in turn building on the work of George Boole , also considers the distinction between quantum and classical theory in light of the inequalities that characterize the possibility space of relative frequencies for a given classical event space. Pitowsky describes a general algorithm for determining these inequalities: Given the logically connected events $`E_1, \dots E_n`$, write down the propositional truth table corresponding to them and then take each row to represent a vector in an $`n`$-dimensional space. Their convex hull yields a polytope, and the sought-for inequalities characterize the facets of this polytope. Alternately, if we already know the inequalities we can then determine the polytope associated with them.

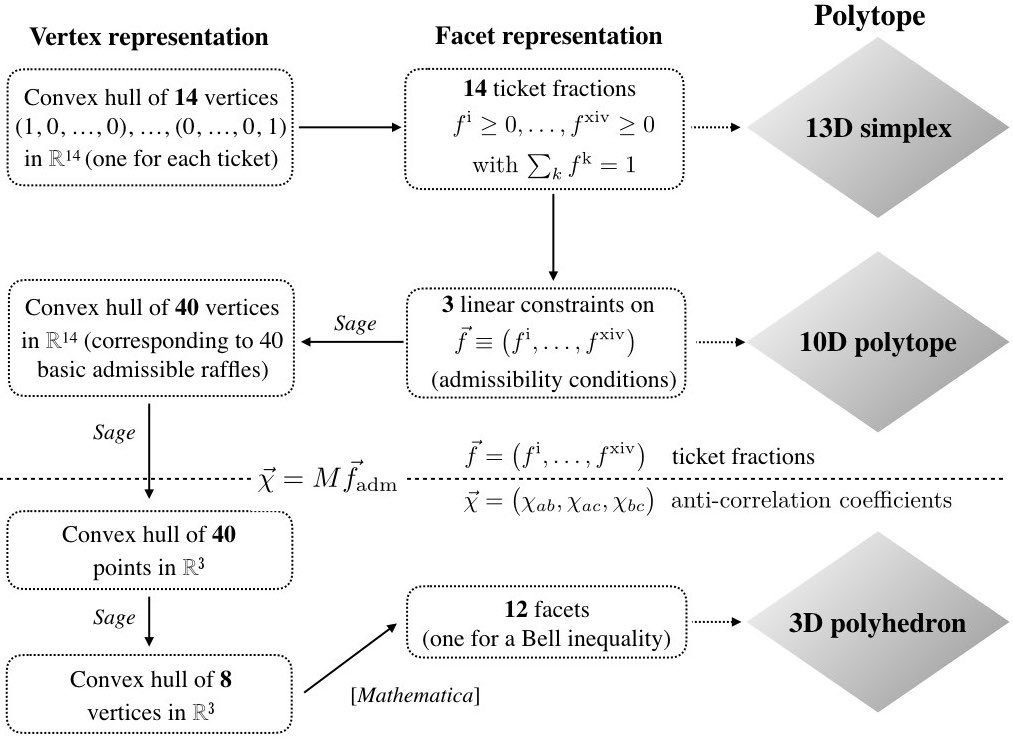

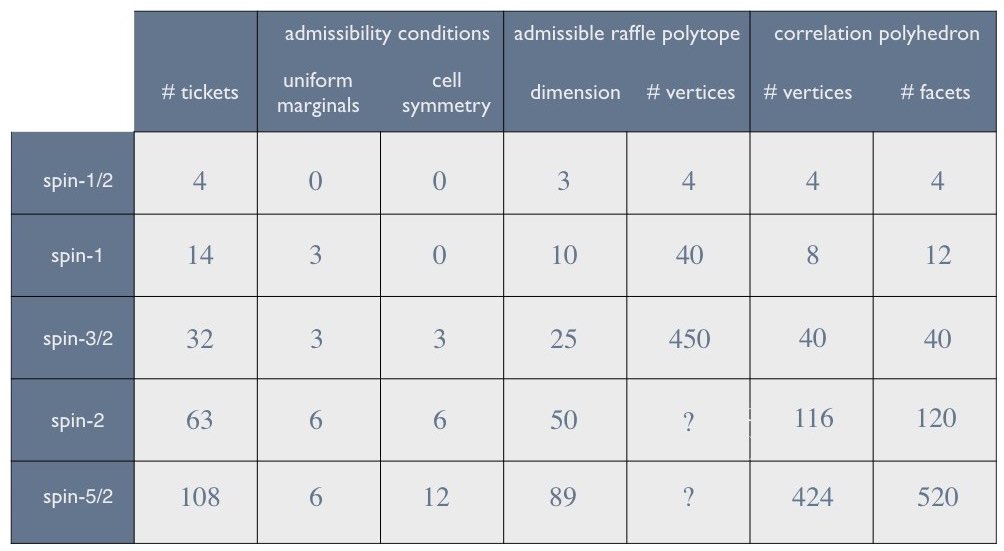

In our own case the event space associated with a 3$`\times`$3 correlation array for a setup involving two possible outcomes per measurement yields an easily visualisable three-dimensional representation of possible correlations between events for both a quantum and a local-hidden variables model. Moreover in the quantum case we showed that the resulting representation remains three-dimensional even when we transition to setups involving more than two outcomes—indeed we showed in Section 6.2.13 that it is in every case the very same elliptope as the one we derived in Section 6.1 for two outcomes (i.e., for spin-$`\frac12`$) and which we depicted in Figure [elliptope]. In the local-hidden variables case (where we model correlations with raffles) the local polytopes characterizing the space of possible correlations for setups with more than two possible outcomes per measurement are of much higher dimension than three. In part through considering only those raffles that have a hope of recovering the quantum set, we showed in Section 3.2 how to project these higher-dimensional polytopes down to three-dimensional anti-correlation polyhedra (see Figure [flowchart]).3 We showed that with increasing spin these polyhedra become further and further faceted and correspondingly more and more closely approximate the full quantum elliptope (see Figure [polytopevolume])—though actually computing these polyhedra becomes more and more intractable as the number of possible outcomes per setting increases. Finally, in addition to providing an easily visualisable representation in three dimensions of the quantum and local-hidden variable correlations associated with a 3$`\times`$3 Mermin-style setup, we showed how the correlation array formalism for this case can be straightforwardly extended so as to provide useful insight into the more familiar correlational space associated with CHSH-style setups, if the latter are characterized using 4$`\times`$4 correlation arrays and parameterized using six anti-correlation coefficients (see Section 4).

As Pitowsky observes ,4 linear inequalities such as those characterizing the facets of our polytopes have been an object of study for probability theorists since at least the 1930s. And although they were (re)discovered in a context far removed from these abstract mathematical investigations, the various versions of Bell’s inequality are all inequalities of just this kind. Non-linear inequalities like the one in Eq. [repeatElliptopeEqn], on the other hand, are not. Nevertheless, equations like this one have also been an object of study for probability theorists. Drawing directly on their work, we showed in Section 6.2.1 how one can derive an equation analogous to Eq. [repeatElliptopeEqn] characterizing the quantum elliptope from general statistical considerations concerning three balanced random variables $`X_a`$, $`X_b`$ and $`X_c`$ (for the meaning of balanced, see the definition numbered ([def balanced]) in Section 2.3). Specifically, we derived a constraint on the correlation coefficients $`\overline{\chi}_{ab}`$, $`\overline{\chi}_{ac}`$ and $`\overline{\chi}_{bc}`$ that is of exactly the same form as Eq. [repeatElliptopeEqn] (which, recall, constrains the anti-correlation coefficients $`\chi_{ab}`$, $`\chi_{ac}`$ and $`\chi_{bc}`$):5$`^,`$6

\begin{equation}

1 - \overline{\chi}_{ab}^2 - \overline{\chi}_{ac}^2 - \overline{\chi}_{bc}^2 + 2 \, \overline{\chi}_{ab} \, \overline{\chi}_{ac} \, \overline{\chi}_{bc} \ge 0.

\label{repeat inf the 5}

\end{equation}In Sections 6.2.2 and 6.2.3 we took up the questions, respectively, of how to model this general statistical constraint quantum-mechanically and in a local-hidden variables model, noting that the general derivation of Eq. [repeat inf the 5] relies essentially on the fact that we can consider a linear combination of the three random variables $`X_a`$, $`X_b`$ and $`X_c`$ in order to determine the expectation value of its square:7

\begin{equation}

\Big\langle \Big( v_a \frac{X_a}{\sigma_a} + v_b \frac{X_b}{\sigma_b} + v_c \frac{X_c}{\sigma_c} \Big)^{\!2} \Big\rangle \ge 0.

\label{repeat inf the 1}

\end{equation}To model such a relation with local-hidden variables, however, we require a joint probability distribution over $`X_a`$, $`X_b`$ and $`X_c`$. This in turn actually entails a tighter bound on the correlation coefficients than the one given by Eq. [repeat inf the 5]. Namely, it entails the analogue of the CHSH inequality for our setup, which should be unsurprising given the classical assumptions we began with. Thus, while the elliptope equation given by Eq. [repeat inf the 5] indeed constrains correlations between local-hidden variables in the setups we are considering, those correlations do not saturate that elliptope. In the case where there are only two possible values corresponding to each of the three random variables, the subset of the elliptope achievable is just the tetrahedron given in Figure 14. For more than two values per variable the situation is more complicated: When the number of possible values, $`n`$, per variable is odd, one can actually reach the Tsirelson bound for this setup—the minimum value of 0 in Eq. [repeat inf the 5]—while when the number of possible values, $`n`$, per variable is even, one reaches the bound only in the limit as $`n \to \infty`$ (see Eqs. ([Mermin CHSH half-integer spin]–[Mermin CHSH integer spin])). But in either case—whether one reaches the Tsirelson bound or not—it appears that one requires a number of possible values $`n \to \infty`$ per random variable in order to saturate the volume of the elliptope in its entirety.8

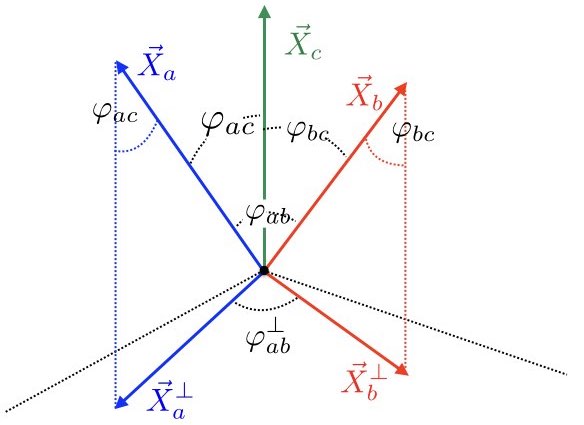

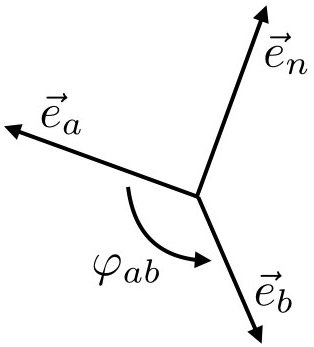

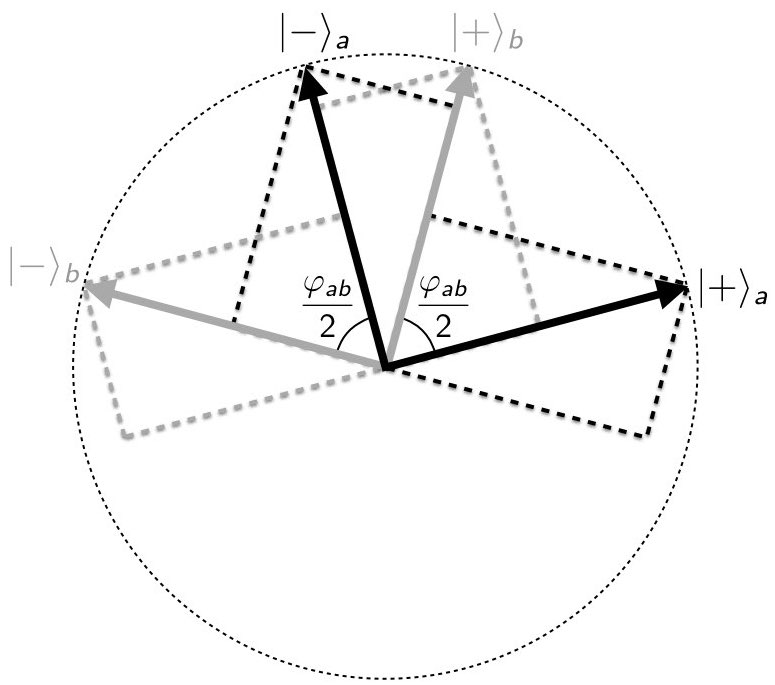

From a slightly different point of view we can understand this as follows. Think of an arbitrary linear combination of the variables $`X_a`$, $`X_b`$ and $`X_c`$ as a vector $`\mathbf{X}`$ in a vector space. (Note that it follows from this that each of the variables $`X_a`$, $`X_b`$, $`X_c`$ is itself trivially also a vector.) And let $`\varphi_{ab}`$, $`\varphi_{ac}`$ and $`\varphi_{bc}`$ represent the “angles” between such vectors . The correlation coefficient $`\overline{\chi}_{\alpha\beta}`$ may then be defined as the inner product of the vectors $`X_\alpha`$ and $`X_\beta`$, yielding (for instance) the natural property that two vectors are uncorrelated whenever they are orthogonal. As we explained in Section 6.2.4, from this point of view we can interpret Eq. [repeat inf the 5] geometrically as a constraint on the angles $`\varphi_{\alpha\beta}`$ between such vectors.

To express this mathematically is one thing. It is another to give a model for it. Note that such a model need not be classical. De Finetti’s own interpretation of the probability calculus, for instance, was not.9 Any underlying model for these correlations that is classical, however, presupposes the existence of a joint distribution over the individual random variables $`X_a`$, $`X_b`$ and $`X_c`$. From this it follows that the correlations realizable in such a model cannot saturate the full volume of the elliptope expressed by Eq. [repeat inf the 5] except in the limit as the number of possible values corresponding to each of the random variables goes to infinity.

As we explained in Section 6.2.2, there are a number of challenges which need to be overcome in order to provide a quantum-mechanical model for the general statistical constraint expressed in Eq. [repeat inf the 5]. The most important of these is that in quantum mechanics one cannot consistently assume a joint probability distribution over incompatible observables, such as one would have to do in order to non-ambiguously define a vector $`\mathbf{X}`$ by taking a linear combination over the quantum analogues of $`X_a`$, $`X_b`$ and $`X_c`$. Since the sum of any two Hermitian operators is also Hermitian, however, then given three observables represented by, say, the operators $`\hat{S}_a`$, $`\hat{S}_b`$ and $`\hat{S}_c`$, one can always also consider the observable represented by the operator $`\hat{S} \equiv \hat{S}_a + \hat{S}_b + \hat{S}_c`$. As von Neumann observed already in 1927,10 quantum mechanics allows us to assign in this way a value to the sum of three variables without assigning values to all of them individually. From this it follows, not only that the elliptope equation constrains the possible correlations in the setups we are considering, but also that it tightly constrains them. The quantum-mechanical correlations in these setups, that is, saturate the full volume of the elliptope. Moreover we saw in Section 6.2.2 how, in virtue of certain other assumptions we needed to model the constraint quantum-mechanically, Eq. [repeat inf the 5]—the equation we derived from without—reduces to Eq. [repeatElliptopeEqn]—the equation we derived from within quantum mechanics.

The remainder of this section is devoted to the philosophical conclusions that can be drawn from the foregoing. Below, in Section 5.2 we will comment on the nature of our derivation of the space of quantum correlations for the setups we have considered. We will note that our derivation evinces aspects of both the principle-theoretic and the constructive approaches to physics, and that in our own derivation and generally in the practice of theoretical physics, both work together to yield understanding of the physical world. In Section 5.3 we will argue that the insight yielded by our own investigation is that the fundamental novelty of the quantum mode of description can be located in the kinematics rather than in the dynamics of the theory. This distinction—between the kinematical and dynamical parts of a theory—is one we take to be of far more significance than the distinction between principle-theoretic and constructive approaches that has been the object of so much recent attention. In Section 5.4 we consider examples, from the history of quantum theory, of puzzles solved as a direct result of the changes to the kinematical framework introduced by quantum mechanics. We close, in Section 5.5, with the topic of measurement. We conclude that there are yet philosophical puzzles to be resolved concerning the quantum-mechanical account of measurement, though we locate these puzzles elsewhere than is standardly done.

Before moving on to Section 5.2 we want to comment on the interpretation of the distinction between principle-theoretic and constructive approaches that figures prominently within it. The idea of such a distinction dates back to a popular article Einstein published in the London Times shortly after the Eddington-Dyson eclipse expeditions had (practically overnight) turned him into an international celebrity. The distinction Einstein drew there has since taken on a life of its own, both in the historical and in the foundational physics literature. The account of this distinction, which we give in the next section, is meant to more closely reflect the latter literature (especially the literature on quantum foundations). It is not meant to reflect what Einstein intended by the distinction either in 1919 or in his later career.11

The account that we give of the distinction is also different from certain others whose interpretations of quantum mechanics are close to ours on the phylogenetic tree we mentioned in Section 1. For instance, on our reading of him (based on his unpublished monograph), Bill Demopoulos uses the label “constructive” to refer to particular dynamical hypotheses concerning the micro-constituents of matter, and uses the label “principle-theoretic” to refer to the specific structural constraints that a theory imposes on the representations it allows. In contrast, our own way of using the label “constructive” is broader than this; a constructive characterization may involve the kinematical features of a theory , and a principle-theoretic characterization may include dynamical posits . In the next section we will be speaking about constructive and principle-theoretic derivations in particular. What is essential about the former kind of derivation is that it begins from an internal perspective—it is a derivation from within quantum theory of some aspect of the world that it describes, while what is essential about the latter kind of derivation is that it begins from an external perspective—it is a derivation from without (i.e., from a more general mathematical framework) of some aspect of the quantum world.

Jeff Bub and Itamar Pitowsky also distinguish principle-theoretic from constructive approaches in their paper. In their case it is actually not clear to us which of the two senses of the distinction given above is the one they really intend, and at various times they seem to be appealing to both (see especially Section 2 of their paper), although in fairness they appear to do so consistently. This slippage is in any case understandable: The idea that the kinematical core of a theory constrains all of its representations is easily mistaken for the idea that this core constitutes a characterizing principle for the theory. In our own discussion we will endeavor to be careful in distinguishing the former from the latter. But regardless of what one makes of the distinction between constructive and principle-theoretic approaches, we take this distinction to be of relatively minor importance. As we will see further below, the more important distinction to bear in mind when interpreting a physical theory, as one of us pointed out in the context of special relativity, is the distinction between the kinematics and the dynamics of that theory .

From within and from without

Our derivation of the space of possible quantum correlations in the 2-party, 3-parameter, Mermin-style setup illustrates the interplay between principle-theoretic and constructive approaches that is typical of the actual practice and methodology of theoretical physics . Our goal was to carve out the space of quantum correlations so as to gain insight into what distinguishes quantum from classical theory. Accordingly, guided by the work of probability theorists and statisticians like De Finetti, Fisher, Pearson and Yule, we associated vectors with random variables and derived a constraint on the angles between such vectors, Eq. [repeat inf the 5], which has the same form as the constraint on anti-correlation coefficients that characterizes the quantum correlational space of our Mermin-style setup. But it would be wrong to stop here. In and of itself Eq. [repeat inf the 5] is just an abstract equation; it neither explains the space of quantum correlations, nor what distinguishes that space from the corresponding classical space. To gain insight into these matters we needed to model the angle inequality both in quantum theory and in a local-hidden variables model.

In the case of a local-hidden variables model, the classical assumptions that underlie the vectors constrained by Eq. [repeat inf the 5] entail a tighter bound on the correlations between them than what is given by the inequality itself. Specifically, assigning a value to the sum of three variables classically requires that we assign a value to all three of them individually. And because of this, the correlations in a local-hidden variables model cannot saturate the full space described by Eq. [repeat inf the 5], unless the number $`n`$ of possible values for a random variable goes to infinity—unless, that is, the range of possible values for a random variable is actually continuous (see Section 6.2.5 for further discussion, as well as note [discrete and contextual]).

In quantum theory, in contrast, this classical presupposition regarding a sum of random variables does not apply. We can indeed still take a sum of three random variables in quantum theory, but we do not need to assign a value to each of them individually in order to do so. As a result, the constraint expressed by the quantum version of the inequality turns out to be tight—quantum correlations, that is, saturate the full volume of the elliptope—regardless of the number of possible values we can assign to the random variables in a particular setup. In this sense Eq. [repeatElliptopeEqn]—a constraint on expectation values—expresses an essential structural aspect of the quantum probability space. Moreover a visual comparison of the quantum elliptope with the various polyhedra we derived for local-hidden variable models vividly demonstrates the way that their respective probabilistic structures differ. This, finally, motivates us to think of quantum mechanics as a theory that is, at its core, about probabilities. But this should not be misunderstood. What is being expressed here is the thought that the conceptual novelty of quantum theory consists precisely in the way that it departs from the assumptions that underlie classical probability spaces.

One of the strengths of principle-theoretic approaches to physics is that they give us insight into the multi-faceted nature of the objects of a theory.12 A formal framework is set up, for example the $`C^*`$-algebraic framework of , one of the minimalist operationalist frameworks of states, transformations and effects discussed in , “general probabilistic” frameworks , “informational” and/or “computational” frameworks , “operator tensor” formulations and so on.13 Each such framework focuses on a particular aspect of quantum phenomena, for example on distant quantum correlations, quantum measurement statistics, quantum dynamics and so on. In the language of a given framework one then posits a principle (or a small set of them), e.g., “no signaling” , “no restriction” , “information causality” or what have you. These principles carve up the conceptual space of a given framework into those theories that satisfy them with respect to the phenomena considered, and those that do not. The correlations predicted by quantum theory, for instance, satisfy the information causality principle, but any theory that allows correlations above the Tsirelson bound corresponding to the CHSH inequality does not .

It may sometimes even be possible to uniquely characterize a theory in a given context—to fix the point in a framework’s conceptual space that is occupied by the theory—and if the principles from which such a unique characterization follows are sufficiently compelling in that context, then situating the theory within it adds to our understanding both of the theory and of the phenomena described by it .14 We are not, of course, claiming that this or that abstract characterizing principle exhausts all that there is to say about quantum theory. But by situating quantum theory within the abstract space provided by a formal framework we subject it to a kind of “theoretical experiment”. Just as with an actual experiment, which we set up to determine this or that property of a physical system, in the course of which we control (i.e., in our lab) parameters that we deem irrelevant to or that interfere with our determination of the particular property of interest, in our theoretical experiments we likewise abstract away from features of quantum theory that are irrelevant to or obfuscate our characterization of it as a theory of information processing of a particular sort, or as a particular kind of $`C^*`$ algebra, or as a theory of probabilities and so on. Quantum theory can be thought of as each of these things. Insofar as it occupies a particular position (or region) within the conceptual space of these respective frameworks, it can be characterized from each of these points of view. And within each perspective within which it can be so characterized, there are constraints on what a quantum system can be from that perspective. It is these constraints which our theoretical experiments set out to discover. And it is these constraints which convey to us information about what quantum theory is and how the systems it describes actually behave under that mode of description.

The value of the principle-theoretic approach is, moreover, not limited to this descriptive role. Principle-theoretic approaches are also instrumental for the purposes of theory development. For instance in the course of setting up a conceptual framework in which to situate quantum theory, we might consider it more natural to relax rather than maintain one or more of the principles that characterize quantum theory in that framework (cf. ). In this way we feel our way forward to new physics. Even, that is, if we do not expect that they themselves will constitute new physical theories, the formal frameworks we set up enable forward theoretical progress by helping us to grasp the descriptive limits of our existing theories and to get a sense of what we may find beyond them.

And yet, earlier we stated our conviction that, “at its core”, quantum mechanics is fundamentally about probabilities. How can this univocal statement be consistent with the claim we have just been making regarding the essentially perspectival nature of the insights obtainable through a principle-theoretic approach? In fact it would be wrong to describe the interpretation of quantum theory that we have been advancing in this paper as a principle-theoretic one.15 As we have described them above, principle-theoretic approaches offer perspectives on quantum theory (or on some aspect of it) that are essentially external: One first sets up a formal framework which in itself has little to do with quantum theory; next one seeks to motivate and define a principle or set of them with which to pinpoint quantum theory within that framework. But what does it mean to pinpoint quantum theory within a framework? Generally this means matching the set of phenomena circumscribed by the principle(s) with the set of phenomena predicted by quantum mechanics, i.e., with those obtained via a derivation from within. In this way one tests that the set of phenomena captured by a set of principles really is the one predicted by quantum mechanics, that these characterizing principles really do constitute a perspective on the theory. A principle-theoretic approach to understanding quantum theory, therefore, is not wholly external. But on the approach just outlined the internal perspective only becomes relevant at the end of the procedure, as a way to gauge the success of one’s theoretical experiment.

For us this latter step was very far from trivial. Indeed it was only through it that we were able to gain full insight into the aspect of quantum phenomena that we were seeking to understand. To recapitulate: We first set up a generalized framework for characterizing correlations and within this framework we considered the angle inequality relating correlation coefficients for linear combinations of random variables expressed by Eq. [repeat inf the 5]. We thus began our derivation from without. We then asked whether one could view this as an expression of the fundamental nature of the correlations between random variables in either a local-hidden variables model such as our raffles, or in a quantum model. That is, we asked whether the correlations in either case saturate the elliptope described by Eq. [repeat inf the 5]. To answer this question we then took a constructive step in both cases: We gave both a local-hidden variables and a quantum model for the general constraint expressed by Eq. [repeat inf the 5]. And by proceeding in this way from within both frameworks we were able to show that, as a consequence of the assumptions underlying the framework of classical probability theory, the angle inequality and its corresponding elliptope cannot be seen as a fundamental expression of the nature of correlations in a local-hidden variables model, for there are further constraints that need to be satisfied in such a model in order to saturate the elliptope. As for the mathematical framework of quantum theory, we saw how it is able to succeed, where a local-hidden variables model cannot, in entirely filling up the elliptope. Finally by considering how it is capable of doing this we are able to understand what the essential distinction between quantum and classical theory is.

The new kinematics of quantum theory

What, then, is the essential distinction between quantum and classical theory? In the end we saw that the key assumption we needed to derive the quantum version of the angle inequality is one which follows straightforwardly from the Hilbert space formalism of quantum mechanics. The Hilbert space formalism, however, applies universally to all quantum systems. Our case studies were limited to a relatively small number of particular experimental setups—the Mermin-inspired setups we considered in Sections 2 and 3 and the CHSH-like setup we considered in Section 4. They were also limited in terms of the quantum states measured in those setups. But we see now that the wider significance of our analyses of these case studies is not likewise limited. For the key feature of the quantum formalism that these special but informative case studies point us to is in fact a fully general one; it expresses quantum theory’s kinematical core .

As mentioned in Section 1, our interpretation of quantum theory owes much to the work of Jeff Bub, Bill Demopoulos, Itamar Pitowsky and others who have proceeded from similar motivations. In their paper, Bub and Pitowsky characterize their interpretation of quantum theory as both principle- and information-theoretic (pp. 445–446), arguing both that the Hilbert space structure of quantum theory is derivable on the basis of information-theoretic constraints, and that quantum theory should in this sense be thought of as being all about information . Interpreted as some sort of ontological claim, the latter is surely false. If, instead, one interprets this as a claim about where the conceptual novelty of quantum theory is located , namely in the structural features of its kinematical core, then we take this claim to be correct, even if we prefer to speak of probability rather than of information (see Section 1).

There is a common viewpoint on interpretation that holds that what it means to interpret a theory is to ask the question: “What would the world be like (in a representational sense) if the theory were literally true of it?” . We reject this as exhaustive of what it means to interpret a theory , and rather affirm that often the more interesting interpretational question is the one which asks what the world must be like (not necessarily in a representational sense) in order for a given theory to be of use to us; i.e., to be effective in describing and structuring our experience and in enabling us to speak objectively about it to one another. Note, on the one hand, the realist commitment implicit in this question. But note, on the other hand, that the question does not presuppose the literal or even the approximately literal truth of the theory being considered. For even classical mechanics, superseded as it has been by quantum mechanics, is of use to us in this sense. And it is a meaningful question to ask how this constrains our possible conceptions of the world.

Such a question can be answered in a number of ways. One might begin, for instance, by positing a priori constraints on what an underlying ontological picture of the world must be like in a general sense, e.g., that it must be some kind of particle ontology . The descriptive success of quantum mechanics (and, correspondingly, the descriptive failure of classical mechanics) would then entail a number of constraints on this general ontological picture, in particular that it must be fundamentally non-local. Alternately (i.e., rather than positing a general ontological picture of the world a priori) one might choose instead to focus more directly on the relation between the formalism of the theory and the phenomena it describes. What aspect of the formalism, one might ask from this point of view, is key to enabling quantum theory to be successful in describing phenomena and coordinating our experience, and what does that tell us about the world? A natural way of illuminating this question is to compare quantum with classical modes of description—to consider what is novel in the quantum as compared with the classical mode of description—and to consider how this allows quantum theory to succeed where classical theory cannot. We take the investigations in the prior sections of this paper to have shown that this novel content can be located in the kinematical core of quantum theory, in the structural constraints that quantum theory places on our representations of the physical systems it describes.

In classical mechanics, an observable $`A`$ is represented by a function on the phase space of a physical system: $`A = f(p, q)`$ where $`p`$ and $`q`$ are the system’s momentum and position coordinates within its phase space. Points in this space can be thought of as “truthmakers” for the occurrence or non-occurrence of events related to the system in the sense that specifying a particular $`p`$ and $`q`$ fixes the values assigned to every observable defined over the system in question. With each observable $`A`$ one can associate a Boolean algebra representing the possible yes or no questions that can be asked concerning that observable in relation to the system. And because one can simultaneously assign values to every observable given the state specification $`(\mathbf{q}, \mathbf{p}) \equiv ((x_i, y_i, z_i), (p_{x_i}, p_{y_i}, p_{z_i}))`$, one can embed the Boolean algebras corresponding to each of them within a global Boolean algebra that is the union of them all. In general there is no reason to think of observables as representing the properties of a physical system within this framework. But because we can fix the value of every observable associated with the system in advance given a specification of the system’s state—because the union of the Boolean algebras corresponding to these observables is itself representable as a Boolean algebra—it is in this case conceptually unproblematic to treat these observables as though they do represent the properties of the system, properties that are possessed by that system irrespective of how we interact (or not) with it.

In quantum mechanics an observable, $`A`$, is represented by a Hermitian operator, $`\hat{A}`$ (whose spectrum can be discrete, continuous or a combination of both) acting on the Hilbert space associated with a physical system, with the possible values for $`A`$ given by the eigenvalues of $`\hat{A}`$: $`\{a: \hat{A}| \psi \rangle = a| \psi \rangle\}`$. Unlike the case in classical mechanics, the quantum state specification for a physical system, $`| \psi \rangle`$, cannot be thought of as the truthmaker for the occurrence or non-occurrence of events related to it, for specifying the state of a system at given moment in time does not fix in advance the values taken on at that time by every observable associated with the system. First, the state specification of a system yields, in general, only the probability that a given observable associated with it will take on a particular value when selected. Second, and more importantly, the Boolean algebras corresponding to the observables associated with the system cannot be embedded into a larger Boolean algebra comprising them all. Thus one can only say that conditional upon the selection of the observable $`A`$, there will be a particular probability for that observable to take on a particular value. At the same time no one of the individual Boolean sub-algebras of this larger non-Boolean structure yields what would be regarded, from a classical point of view, as a complete characterization of the properties of the system in question. As we will see in Section 5.5, this does not preclude a different kind of completeness from being ascribed to the quantum description of a system. But because our characterization is not classically complete, it is no longer unproblematic to take the observable $`A`$ as a stand-in for one of the underlying properties of the system, even in the case where quantum mechanics predicts a particular value with certainty conditional upon a particular measurement.

To put it a different way: Because classical-mechanical observables can be set down in advance, irrespective of the nature of the interaction with the system from which they result, they can straightforwardly be taken to represent “beables” with respect to a given state specification. Quantum-mechanical observables cannot be, or at any rate there can be no direct, unproblematic, inference from observable to beable within quantum theory—something more, some further argument must be given. As for us, we have yet to see a convincing argument to this effect. We rather take quantum theory to be telling us that there can be no ground in the classical sense of a fully determinate globally Boolean noncontextual assignment of values to all of the observables relevant to a given system .

In the context of space-time theories, Minkowski space-time encodes generic constraints on the space-time configurations allowed by any specific relativistic theory compatible with its kinematics. These constraints are satisfied as long as all of the observables are represented by mathematical objects that transform as tensors (or spinors) under Lorentz transformations. Analogously, in quantum mechanics, Hilbert space encodes generic constraints on the possible values of observables as well as on the correlations between such values that are allowed within any specific quantum theory compatible with its kinematics. These constraints are satisfied as long as all of the observables are represented by Hermitian operators acting on Hilbert space. In the case of Minkowski space-time, the determination of the particular tensor (or spinor) representative of a given transformation is the province of the dynamics, not the kinematics, of the specific relativistic theory in question. Likewise, determining the particular self-adjoint operator representative of a given action on a system is a province of the dynamics, not the kinematics, of the specific quantum theory in question.

Just as in special relativity, the kinematical part of quantum theory is a comparatively small one. The lion’s share (and more) of the practice of quantum theory is concerned with determining the dynamical aspects of particular systems of interest. And yet, conceptually, the kinematics of quantum theory may justifiably be regarded as its most important part; it constitutes the “operating system” upon which the dynamics of particular physical systems can be seen as “applications” being run .

Examples of problems solved by the new kinematics

As in the transition from 19th-century ether theory to special relativity , one can find examples in the transition from the old to the new quantum theory of puzzles solved as a direct result of changes in the basic kinematical framework. Unsurprisingly, given our characterization of the “big discoveries” of Heisenberg and Schrödinger in Section 1, these examples are easier to come by in the early history of matrix mechanics than in the early history of wave mechanics, but they can be found in both.

The basic idea of the paper with which laid the foundation of matrix mechanics was not to repeal the laws of classical mechanics but to reinterpret them . This is clearly expressed in the title of the paper: “Quantum-theoretical reinterpretation (Umdeutung) of kinematical and mechanical relations.” Heisenberg replaced the real numbers $`p`$ and $`q`$ by non-commuting arrays of numbers soon to be recognized as matrices and then as operators. These operators, $`\hat{p}`$ and $`\hat{q}`$, satisfy the same relations as $`p`$ and $`q`$ (e.g., the functional dependence of the Hamiltonian on these variables will remain the same) but they are subject to the commutation relation, $`[\hat{q} \, , \, \hat{p}] = i\hbar`$, the quantum analogue, as realized early on, of Poisson brackets in classical mechanics.

In the final section of the Dreimännerarbeit, the joint effort of Max Born, Werner Heisenberg and Pascual Jordan that consolidated matrix mechanics, the authors (or rather Jordan who was responsible for this part of the paper) showed that the new formalism automatically yields both terms of a famous formula for energy fluctuations in black-body radiation .16 had derived this formula from little more than the connection between entropy and probability expressed in the formula $`S = k \ln{W}`$ carved into Boltzmann’s tombstone and Planck’s law for black-body radiation. One of its two terms suggested waves, the other particles. Einstein had argued in 1909 that the latter called for a modification of Maxwell’s equations . He had contemplated such drastic measures before when faced with the tension between Maxwell’s equations and the relativity principle. The new kinematics of special relativity had resolved that tension. Jordan now showed that the tension between Maxwell’s equations and Einstein’s fluctuation formula could also be resolved by a change in the kinematics.

Instead of a cavity with electromagnetic waves obeying Maxwell’s equations, Jordan considered a simple model, due to Paul , of waves in a string fixed at both ends. This string can be replaced by an infinite number of uncoupled harmonic oscillators. Quantizing those oscillators, using the basic commutation relation $`[\hat{q} \, , \, \hat{p}] = i\hbar`$, and calculating the fluctuation of the energy in a small segment of the string in a narrow frequency interval, Jordan recovered both the wave and the particle term of Einstein’s formula. Using classical kinematics, one only finds the wave term. As Jordan concluded:

The reasons for the occurrence of a term not delivered by the classical theory are obviously closely related to the reasons for the occurrence of the zero-point energy [of the harmonic oscillator, which itself follows directly from the commutation relation for position and momentum]. In both cases, the basic difference between the theory attempted here and the one attempted so far [i.e., classical theory with the restrictions imposed on it in the old quantum theory] lies not in a disparity of the mechanical laws but in the kinematics characteristic for this theory. One could even see in [this fluctuation formula], into which no mechanical principles whatsoever even enter, one of the most striking examples of the difference between quantum-theoretical kinematics and the one used hitherto .

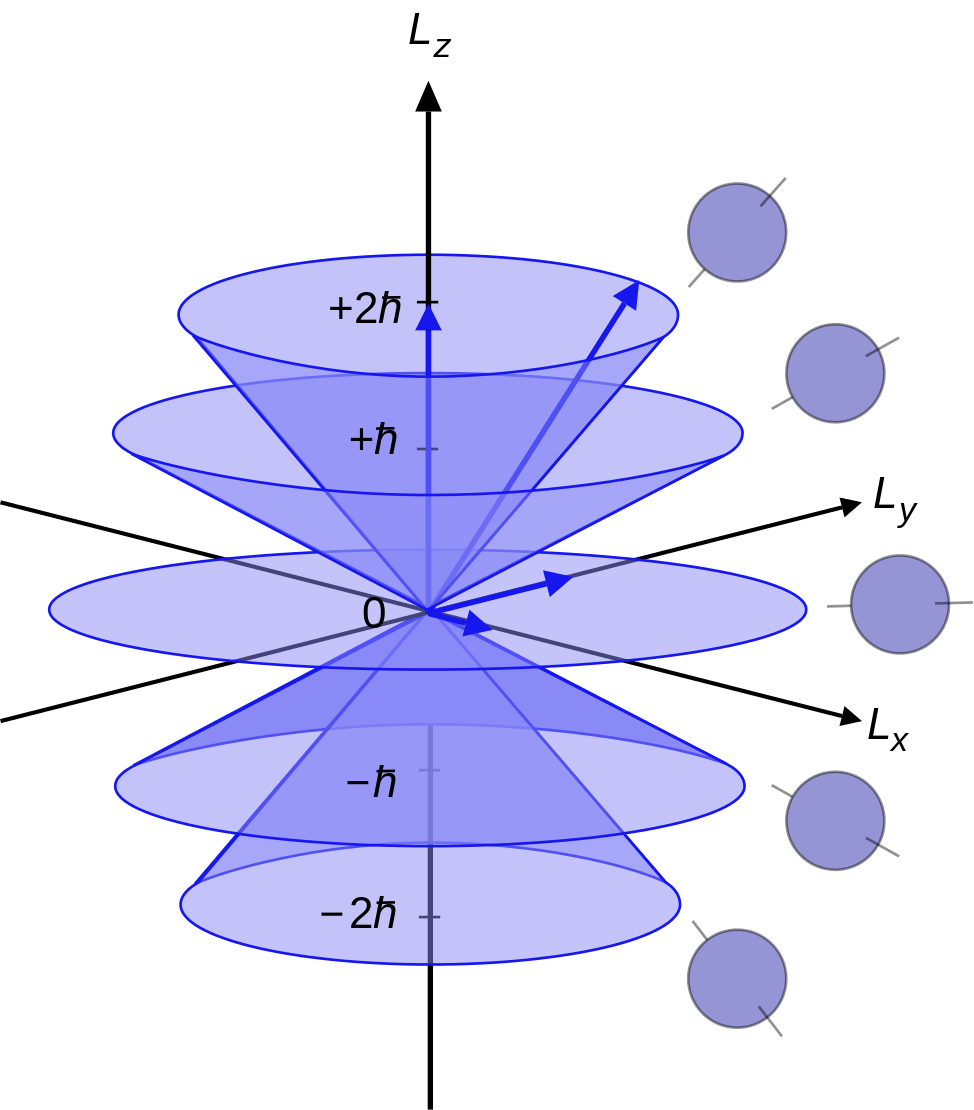

Our second example turns on the quantum-mechanical treatment of orbital angular momentum, which proceeds along the exact same lines as the treatment of intrinsic or spin angular momentum underlying the quantum-mechanical analysis of the experiments we have been studying in Sections 2–4. We already alluded to this example at the end of Section 6.2.2. It is the problem of the electric susceptibility of diatomic gases such as hydrogen chloride.17 One of the two terms in the so-called Langevin-Debye formula for this quantity comes from the alignment of the molecule’s permanent dipole with the external field. This term decreases with increasing temperature as the thermal motion of these dipoles frustrates their alignment. This makes it at least intuitively plausible that only the lowest energy states of the molecule contribute to the susceptibility. This is indeed what the classical theory predicts. In the old quantum theory, however, this feature was lost. This is a direct consequence of the way in which angular momentum was quantized. The length $`L`$ of the angular momentum vector could only take on values $`l \hbar`$ in the old quantum theory, where $`l`$ is an integer greater than 1. The value $`l=0`$ was ruled out for the same reason that it was ruled out for the hydrogen atom: an orbit with zero angular momentum would have to be a straight line going back and forth through the nucleus! Hence $`l \ge 1`$ for all states contributing to the susceptibility. This led to the strange situation, as noted in one of his early papers, that there are “only such orbits present that according to the classical theory do not give a sizable contribution to the electrical polarization” (emphasis in the original). Fortunately, the allowed orbits (or energy states) with $`l \ge 1`$ do give a sizable contribution. Unfortunately, this contribution is almost five times too large.

The quantization of angular momentum in the new quantum mechanics was worked out in the Dreimännerarbeit mentioned above . The upshot was that the correct quantization of angular momentum leads to the eigenvalues $`l(l+1)`$ for $`\hat{L}^2`$, where the allowed integer values of $`l`$ start at 0 rather than 1 (cf. Eq. [state dfn] in Section 3.1). This new quantization rule for angular momentum follows directly from the basic commutation relation for position and momentum.

Pauli and his former student Lucy Mensing showed how this new quantization rule solved the puzzle of the electric susceptibility of diatomic gases. As in classical theory, only the lowest ($`l=0`$) state contributes to the susceptibility, the contributions of all other terms sum to zero (and this depends delicately on the exact quantization rule). As noted with palpable relief: “Only the molecules in the lowest state will therefore give a contribution to the temperature-dependent part of the dielectric constant" (emphasis, once again, in the original). The new quantum theory thus reverted to the classical theory in this respect. In a note to Nature on the topic, Van Vleck made the same point: “The remarkable result is obtained that only molecules in the state of lowest rotational energy make a contribution to the polarisation. This corresponds very beautifully to the fact that in the classical theory only molecules with [the lowest energy] contribute to the polarisation" .

Van Vleck expanded on this comment when interviewed in 1963 by his former PhD student Thomas S. Kuhn for the Archive for History of Quantum Physics (AHQP):

I showed that [the Langevin-Debye formula for susceptibilities] got restored in quantum mechanics, whereas in the old quantum theory, it had all kinds of horrible oscillations … you got some wonderful nonsense, whereas it made sense with the new quantum mechanics. I think that was one of the strong arguments for quantum mechanics. One always thinks of its effect and successes in connection with spectroscopy, but I remember Niels Bohr saying that one of the great arguments for quantum mechanics was its success in these non-spectroscopic things such as magnetic and electric susceptibilities.18

Van Vleck was so taken with this result that it features prominently in his Nobel lecture in 1977 . The important point for our purpose is that this is another example of a problem that was solved by a change in the kinematics rather than the dynamics.

The two examples given so far both turned on the commutation relation $`[\hat{q} \, , \, \hat{p}] = i\hbar`$ at the heart of matrix mechanics. Our third and last example turns on a key feature of wave mechanics. As we noted in Section 1, Schrödinger, unlike Heisenberg, may not have emphasized that his new theory provided a new framework for doing physics but this is, of course, as true for wave mechanics as it is for matrix mechanics. An obvious example of a change in the basic framework for doing physics that emerged from the development of wave mechanics rather than matrix mechanics is the introduction of quantum statistics, especially Bose-Einstein statistics, which preceded the formulation of wave mechanics. We close this subsection with a less obvious but informative example.19

In the same year that saw the appearance of Bohr’s atomic model, Johannes discovered the effect named after him, the splitting of spectral lines due to an external electric field, the analogue to the effect discovered by Pieter Zeeman in 1896, the splitting of spectral lines due to a magnetic field. It was not until two key contributions—one by a physicist, Arnold Sommerfeld, in late 1915; one by an astronomer, Karl Schwarzschild, in early 1916—that there was any hope of accounting for the Stark effect on the basis of the old quantum theory, the extension, mainly due to Sommerfeld, of Bohr’s original ideas. Sommerfeld’s key contribution to the explanation of the Stark effect was to introduce (even though he did not call it that) degeneracy, the notion that the same energy level can be obtained with different combinations of quantum numbers. External fields will lift this degeneracy and result in a splitting of the spectral lines associated with transitions between these energy levels. Schwarzschild’s key contribution was to bring the advanced techniques developed in celestial mechanics to bear on the analysis of the miniature planetary systems representing atoms in the old quantum theory. Once those two ingredients were available, and Paul , an associate of Sommerfeld, quickly and virtually simultaneously derived formulas for the line splittings in the Stark effect in hydrogen that were in excellent agreement with the experimental data.

Even though some energy states and some transitions between them had to be ruled out rather arbitrarily and even though there was no convincing explanation for the polarizations and relative intensities of the components into which the Stark effect split the spectral lines, this was seen as a tremendous success for the old quantum theory. As Sommerfeld exulted in the conclusion of the first edition of Atombau und Spektrallinien (Atomic structure and spectral lines), which became known as the “the bible of atomic theory” : “the theory of the Zeeman effect and especially the theory of the Stark effect belong to the most impressive achievements of our field and form a beautiful capstone on the edifice of atomic physics” .

Even in the case of the Stark effect (to say nothing of the Zeeman effect), Sommerfeld’s jubilation would prove to be premature. In addition to the limitations mentioned above, there was a more subtle but insidious difficulty with Schwarzschild and Epstein’s result. To find the line splittings of the Stark effect, they had to solve the so-called Hamilton-Jacobi equation, familiar from celestial mechanics, for the motion of an electron around the nucleus of a hydrogen atom immersed in an external electric field. This could only be done in coordinates in which the Hamilton-Jacobi equation for this problem is separable, i.e., in coordinates in which the equation splits into three separate equations, one for each of the three degrees of freedom of the electron. Similar problems in celestial mechanics made it clear that they needed so-called parabolic coordinates for this purpose. These then also were the coordinates in which Schwarzschild and Epstein imposed the quantum conditions to select a subset of the orbits allowed classically. As long as there is no external electric field, it was much simpler to do the whole calculation in polar coordinates. Letting the strength of the external field go to zero, one would expect that the quantized orbits found in parabolic coordinates reduce to those found in polar coordinates. This turns out not to be the case. The energy levels are the same in both cases but the orbits are not. Both Sommerfeld and Epstein recognized that this is a problem (Schwarzschild died the day his paper appeared in the proceedings of the Berlin academy). As put it:

Even though this does not lead to any shifts in the line series, the notion that a preferred direction introduced by an external field, no matter how small, should drastically alter the form and orientation of stationary orbits seems to me to be unacceptable .

The old quantum theory simply did not have the resources to tackle this problem and nothing was done about it.

The Stark effect in hydrogen was one of the first applications of Schrödinger’s new wave mechanics. The calculation is actually very similar to the one in the old quantum theory. This is no coincidence. An important inspiration for Schrödinger’s wave mechanics was Hamilton’s optical-mechanical analogy . So it is not terribly surprising that Hamilton-Jacobi theory informed the formalism Schrödinger came up with. The time-independent Schrödinger equation was actually modeled on the Hamilton-Jacobi equation. The time-independent Schrödinger equation for an electron in a hydrogen atom in an external electric field is, once again, most easily solved in parabolic coordinates. Independently of one another, and did this calculation shortly after wave mechanics arrived on the scene. To first order in the strength of the electric field, this calculation yields the same splittings as the old quantum theory. However, as both Schrödinger and Epstein emphasized, no additional restrictions on states or transitions between states are necessary and the theory also correctly predicts the polarizations and intensities of the various Stark components. What Schrödinger and Epstein did not mention, however, was that wave mechanics also solves the problem of the non-uniqueness of orbits of the old quantum theory. Although physicists at the time lacked the mathematical tools to express this—and the problem, it seems, quickly got lost in the waves of excitement about the new theory20—the problematic non-uniqueness of orbits in the old quantum theory turns into the completely innocuous non-uniqueness of bases of wave functions in an instantiation of Hilbert space .

Both Heisenberg and Schrödinger recognized the problematic nature of the old quantum theory’s electron orbits, which had been imported from celestial mechanics along with the mathematical machinery to analyze atomic structure and atomic spectra . An area in which the trouble with orbits had become glaringly obvious by the early 1920s was optical dispersion, the study of the dependence of the index of refraction on the frequency of the refracted light. Heisenberg’s Umdeutung paper builds on a paper he co-authored with Hans Kramers, Bohr’s right-hand man in Copenhagen, on Kramers’s new quantum theory of dispersion . Taking his cue from this theory, Heisenberg steered clear of orbits altogether in his Umdeutung paper and focused instead on observable quantities such as frequencies and intensities of spectral lines . The quantities with which he replaced position and momentum were not, in his original scheme, themselves observable. Instead they functioned as auxiliary quantities that allowed him to calculate the values of (indirectly) observable quantities such as energy levels and transition probabilities. Schrödinger did not get rid of orbits as radically as Heisenberg. His wave functions can be seen as a new way to characterize atomic orbits once we have come to recognize that they are the manifestation of an underlying wave phenomenon. Comparing these different responses to the trouble with orbits in the old quantum theory, we see the beginnings of the two main lineages of the genealogy we proposed in Section 1 to classify different interpretations of quantum mechanics.

Measurement

Consider a measurement device that has been set up to assess the spin state of an ensemble of electrons that has been prepared in a particular way. For instance, imagine we have prepared a uniform ensemble of electrons in the superposition state (cf. Section 6.1):

\begin{align}

\label{eqn:pm-superpos}

| \psi \rangle = \alpha | + \rangle_z \, + \, \beta | - \rangle_z.

\end{align}We direct the electrons one at a time toward the device, which we have prepared so that it will measure their spin in the $`z`$-direction. We observe the results of our experiment and see that in each case, the spin state of the electron is recorded as having a definite value of either up ($`+`$) or down ($`-`$) along the $`z`$-axis, and further that the distribution of results is such that an electron’s spin is recorded as up with a relative frequency that tends toward $`|\alpha|^2`$ and as down with a relative frequency that tends toward $`|\beta|^2`$. What is the explanation?

Here is an attempt. The quantum-mechanical state description assigns a probability to the outcome of a measurement that is given (in the case of a projective measurement in the $`z`$-basis) by:

\begin{align}

\label{eqn:outcome-prob}

\mathrm{Pr}(m|\hat{z}) = \, _{z\!}\langle \psi | \hat{P}_m | \psi \rangle_{\!z},

\end{align}where

\begin{align}

\label{eqn:projection}

\hat{P}_m \equiv |m\rangle_{\!z} \, _{z\!}\langle m|

\end{align}is the projection operator corresponding to the outcome $`m`$. For the current example involving a uniform ensemble of electrons in the state given by Eq. [eqn:pm-superpos] this entails that:

\begin{align}

\mathrm{Pr}(+| \hat{z}) & = \Big(\alpha^*\,_{z\!}\langle + | \,+\, \beta^*\,_{z\!}\langle - |\Big)\Big(| + \rangle_{\!z}\,_{z\!}\langle + | \Big) \Big(\alpha| + \rangle_{\!z} \,+\, \beta| - \rangle_{\!z}\Big) \nonumber \\[.3cm]

& = \alpha^*\,_{z\!}\langle + |\Big(\alpha| + \rangle_{\!z} \,+\, \beta| - \rangle_{\!z}\Big) = \alpha^*\alpha = |\alpha|^2,

\end{align}and similarly for $`\mathrm{Pr}(-| \hat{z})`$. This agrees with the statistics actually observed. In the more general case of a non-uniform ensemble described by the density operator21

\begin{align}

\label{eqn:densityop}

\hat{\rho} = \sum_i| \psi \rangle_{\!i} \, _{i\!}\langle \psi |,

\end{align}the probability of the outcome $`m`$, in the case of a projective measurement in the $`z`$-basis, is given by

\begin{align}

\label{eqn:probdensityop}

\mathrm{Pr}(m|\hat{z}) = \mbox{Tr}(\hat{\rho} \hat{P}_m).

\end{align}Gleason’s theorem tells us that quantum mechanics’ assignment of probabilities is complete in the sense that every probability measure on the Boolean sub-algebras associated with the observables of a system is representable by means of a density operator in the manner just described.22

The account of a quantum-mechanical measurement given above will be criticized. What has been given, it will be maintained, is merely a recipe for recovering the statistics associated with such a measurement. All we learn from this recipe is that, and how, the quantum formalism may be used to calculate the probabilities that will be observed upon interacting the system of interest with a device we set up to measure one of its dynamical parameters. No account has been given here of how the measurement interaction itself allows for this, however. And this is what is demanded by our objector.

Now consider again a measurement in the $`z`$-basis on an electron that is part of a uniform ensemble of systems prepared in the state described by Eq. [eqn:pm-superpos]. This state description is non-classical. However given such a measurement one knows—even before it has interacted with the measurement device—that conditional upon that measurement, we can consider each electron as a member, not of the uniform ensemble that has actually been prepared, but rather of a non-uniform ensemble whose relative proportion of systems in the states $`| + \rangle_{z}`$ and $`| - \rangle_{z}`$ is $`|\alpha|^2`$ and $`|\beta|^2`$, respectively. That is, conditional upon a $`z`$-basis measurement, the observed statistics will not be distinguishable from those that would be observed from a $`z`$-basis measurement on an ensemble characterized by the density operator for the mixed state

\begin{align}

\label{eqn:mixedstate}

\hat{\rho} = |\alpha|^2| + \rangle_{\!z} \, _{z\!}\langle + | ~+~ |\beta|^2| - \rangle_{\!z} \, _{z\!}\langle - |.

\end{align}Because of this we can simulate the observed statistics, conditional upon such a measurement, with a local-hidden variables model similar to the raffles we used in the previous sections of this paper. Unlike those raffles, the phenomena we are simulating here are not correlations, thus our tickets will not need to have two halves like the ones depicted in Figure 10. In the current scenario we can make do with a basket of raffle tickets inscribed with a single symbol, either “$`|+\rangle`$” or “$`|-\rangle`$”, whose relative proportions in the basket are $`|\alpha|^2`$ and $`|\beta|^2`$, respectively. Thus, we have here an account of how, through measuring a system in a given basis, our characterization of the system transitions from a quantum to an effectively classical description. Moreover if one repeats this procedure sufficiently many times, for measurements in the $`z`$ and possibly also in other measurement bases, one can convince oneself that the statistics yielded by these measurements accord with one’s expectations given the initial quantum-mechanical description of the ensemble, i.e., the description of it as a uniform ensemble of electrons in the state given by Eq. [eqn:pm-superpos].

Again this will be criticized. This explanation of the measurement process, it will be objected, is no explanation at all. Our measurement seems almost magical on the account just given, a black box whose inner workings we do not grasp. But it is a goal of physical inquiry to open all such boxes, and it will be demanded of us that we open this one as well.

In the present instance this demand is completely legitimate, for so far we have told you nothing of the details of the measurement interaction outlined above. Obviously, though, there are many good reasons to want to be informed of such details. If the measurement statistics do not accord with our expectations, for instance, we will want to examine the inner workings of the measurement device in more detail to see whether it is functioning properly. Even when we have full confidence in a particular device, we might still want information about its inner workings so that we can reproduce the experiment in another physical location with different equipment. Or maybe we simply want to understand its inner workings for understanding’s sake. These are all legitimate reasons to demand a deeper explanation of the measurement interaction described above. And within quantum theory it is always possible to give you such a description, i.e., to describe how a particular measurement device dynamically interacts with a given system of interest, gives rise to an entangled state of the system of interest and apparatus, and yields probabilities for the state of the measuring device that will be found upon its being assessed.

To come back to our running example: Rather than considering our system of interest to be a member of a uniform ensemble of electrons in the state given by Eq. [eqn:pm-superpos], one can instead describe our system of interest as a member of a uniform ensemble of composite systems, where the state of each member is describable by the entangled superposition:

\begin{align}

\label{eqn:compound}

\alpha |+ \rangle_{Mz} |+ \rangle_{Sz} \, + \; |- \rangle_{Mz} | - \rangle_{Sz}

\end{align}with $`| + \rangle_{Sz}`$, $`|- \rangle_{Sz}`$ (where $`S`$ stands for the system of interest) representing the two possible spin-$`z`$ states of the electron, and $`| + \rangle_{Mz}`$, $`| - \rangle_{Mz}`$ representing the corresponding two possible magnetic field orientations of the DuBois magnets used in the apparatus. In this way we move back “the cut” : the dividing line between, on the one hand, our quantum description of the system we are measuring, and on the other hand, our description of the instrument we are using to assess that system’s state. That part of the measurement phenomenon which, on our earlier analysis, was the instrument of measurement is now, on this more detailed analysis, part of the (quantum) system measured. But as before, if one considers measuring this system in (for instance) the basis

\begin{align}

\label{eqn:zzbasis}

\mathcal{B}_{zz} \equiv \{|+\rangle_{Mz}|+\rangle_{Sz},~ |+\rangle_{Mz}|-\rangle_{Sz},~ |-\rangle_{Mz}|+\rangle_{Sz},~ |-\rangle_{Mz}|-\rangle_{Sz}\},

\end{align}one can treat the expected statistics, conditional upon that choice of basis, as arising from measurements on a non-uniform ensemble of composite systems for which the proportion of such systems in the state $`| + \rangle_{Mz}| + \rangle_{Sz}`$ is $`|\alpha|^2`$ and the proportion of such systems in the state $`| - \rangle_{Mz}| - \rangle_{Sz}`$ is $`|\beta|^2`$. Similarly to before, one can simulate these statistics using a raffle with tickets marked as either “$`|+\rangle|+\rangle`$” or “$`|-\rangle|-\rangle`$”, with proportions $`|\alpha|^2`$ and $`|\beta|^2`$, respectively. In other words we see, in more detail now, how the measurement interaction gives rise to an effectively classical description of the statistics observed. Note, though, that in this particular case the more detailed analysis of the interaction yields the very same expected statistics as the less detailed analysis. In the scenario we are imagining, this is as it should be, for we were not looking for a different result but merely for a deeper understanding of the interaction between the electron and the measuring device.

It is not the case, however, that any cut we impose on a given phenomenon will be compatible with any other. Consider, for instance, two identically prepared ensembles of electrons, both in the state given by Eq. [eqn:pm-superpos]. Imagine that we subject the electrons in the first ensemble to a $`z`$-basis measurement while we subject the electrons in the second ensemble to an $`x`$-basis measurement. If we now examine the $`z`$-component of spin for the electrons in both ensembles (through a further measurement in the $`z`$-basis in both cases), we will see that the statistics yielded by the first ensemble are incompatible with the statistics yielded by the second. And similarly, if we take two identical ensembles of compound systems, each in the state given by Eq. [eqn:compound], and subject the first to a measurement in the basis

\begin{align}

\label{eqn:xzbasis}

\mathcal{B}_{xz} \equiv \{|+\rangle_{Mx}|+\rangle_{Sz},~ |+\rangle_{Mx}|-\rangle_{Sz},~ |-\rangle_{Mx}|+\rangle_{Sz},~ |-\rangle_{Mx}|-\rangle_{Sz}\},

\end{align}while we subject the second to a measurement in the basis $`\mathcal{B}_{zz}`$, then our statistics for $`| + \rangle_{Mz}| + \rangle_{Sz}`$ and $`| - \rangle_{Mz}| - \rangle_{Sz}`$ (which, again, we will have to determine through a further measurement in the basis $`\mathcal{B}_{zz}`$) will not be compatible with one another.

Corresponding to any particular cut that we impose on a particular phenomenon is a particular experimental arrangement, and with it a different physical interaction through which we assess the state of the system being probed .23 Corresponding to this new cut—to this new subdivision of the measurement phenomenon—is a different description which will in general be incompatible with the first (cf. and especially ’s response in Section 10.4 of the revised edition of Bananaworld). As we saw in Section 5.3, quantum theory presents us with a fundamentally non-Boolean kinematical structure of possibilities. Upon this structure, we impose a particular Boolean frame. We do this through the need to express our experience of the result of a particular measurement—an experience of events that either do or do not occur, and which together fit into a consistent picture of the phenomenon in the particular measurement context being considered .24 In this way we partition the quantum-theoretical description into a quantum (non-Boolean) part, and a classical (Boolean) part. The latter is what we leave out of the quantum description. But it is left out by stipulation. The cut is movable. It is something that we impose upon our description of nature. Importantly, however, along with every cut comes a particular measurement context, and a particular measurement interaction corresponding to that context. And yet there is something that we may call perspective-independent within quantum theory: This is its kinematical core, the fundamental structural constraints that quantum theory places on the possible representations of the physical systems it describes.

Our example of the measurement interaction given in Eq. [eqn:compound] could of course be given in even more detail. More of the components of the Stern-Gerlach device being used and of the dynamical interactions occurring between them and between them and the electron can be included in our description of the experiment—in fact one can include as many of these components as one likes. Moreover if there is an external system being used to assess the state of the Stern-Gerlach device after its interaction with the electron (your eyes, your ears, or even your nose, for instance), these can in principle be included in a dynamical description of the measurement as well. Indeed, quantum mechanics can be used to describe the interaction between any two systems, one of which is to be called the “system of interest”, the other the “measuring device”, irrespective of the level of internal complexity of either of them. This description will be of essentially the same form that it took in the simple examples given above. And in all cases the quantum description of an interaction will give us the answer to how, conditional upon it, the observed statistics can effectively be treated as classical.

What of the universe as a whole? There are areas of physics (notably cosmology) in which we aim to describe the universe in its totality as well as the dynamical evolution of that totality. Even putting cosmology to one side, is it not the goal of fundamental physics, generally speaking, to yield up a total description of whatever aspect of the world is being considered? In order to do that, however, one would seem to require, not an account of this or that particular measurement (however detailed it may be), but rather an account of the measurement process in in general. Second, if we are to provide a total description of reality, the scope of quantum description in the case of a measurement cannot be limited to the system of interest alone. Rather, the measurement apparatus itself should be included in one’s quantum description of the interaction. It is true that it has been shown above how to do this to some extent, yet on the account of a measurement interaction given it is still the case that the emergence of a particular probability distribution is always conditional upon the particular (classical) assessment that we make. No matter how far we push back the cut, some cut must always remain on this account. But this, it will be objected, is unacceptable; it cannot constitute a total description of reality.

The first demand—that an account of measurement must take the form of a general dynamical account —is a demand we reject. There is no dynamical process of measurement in general. There are only particular measurements. And in every particular case quantum mechanics provides, as we have illustrated, the general scheme through which a dynamical account of that measurement process can be given. Quantum mechanics provides, that is, the tools we need in order to give an account of how the particular measurement apparatus in question dynamically interacts with a particular system of interest so as to give rise to a combined system in an entangled superposition yielding probabilities for the state of the measuring device that will be found upon assessing it.

As for the second objection: This, we maintain, misunderstands the nature of the cut upon which the quantum-mechanical assignment of conditional probabilities is based. For asserting the necessity of such a cut does not amount to the claim that measurement necessarily involves an interaction with some “classical physical system”, where by this we imagine something large or heavy or both. Indeed, an atomic system can in many cases serve very well as a measuring apparatus . The claim being made here, rather, is a logical one. Specifically, the claim is that in order to represent the assessment of a system’s state, one needs to distinguish between that assessment and the system being assessed. This is true regardless of the measurement interaction in question, and indeed it is true even if the measurement scenario imagined is one in which it is the state of the entire universe being assessed, say, by a supreme being. It is still the case that this supreme being must distinguish, in its description of its measurement, its assessment of that measurement from the system it is measuring. And there is no reason to stop there; for there is nothing to stop one from considering the supreme being and the universe as together comprising a single physical system (supposing that the supreme being exists somehow in space and time); and in that case one still needs to distinguish one’s assessment of that larger system from the system being assessed. There is no “view from nowhere” within quantum mechanics with respect to its account of observation. Nor should there be.

Consider, by way of analogy, the claim one might make in the context of classical physics that one can measure the length of a given body with a rod, or the lifetime of a given particle with a clock. Now to conduct an accurate measurement, the rod must be rigid, the clock ideal. And a legitimate demand one might make in this instance is that the existence of such rigid rods and ideal clocks be substantiated. Einstein accepted this, and in his debate with Weyl over the issue, appealed to the identical spectral lines manifested by atoms of the same kind as compelling evidence for the existence of such ideal instruments . Now the further objection was not made, though it conceivably could have been, that in connecting the theory up with our experience in this way, it is still presupposed, in every particular case, that somehow a rod or a clock has been determined to be a suitable one, and to complete the theory we require an account of how such a determination can be possible. In the context of special relativity this objection is easily dismissed as an extra-physical, purely philosophical concern. And yet, the analogous question in the case of quantum mechanics is not so readily dismissed.25

The issue, it seems, is the intrinsic randomness of the theory. The dynamical account of a given measurement that is provided by quantum mechanics ultimately ends in probabilities; it does not end in definite outcomes. And yet when one assesses the state of a given system the result is in every case a definite outcome. What, one will ask, is to be made of the definite character of these particular outcomes as contrasted with the apparent indefiniteness we attach to the description of a quantum state, and how is it that the former can be seen as arising from the latter? For someone motivated by this worry, appealing to the quantum-mechanical account of the dynamics of a particular measurement, as we did above, is a non sequitur; the quantum-mechanical account of a measurement, no matter how deep or encompassing one makes it, in the end can only yield indefiniteness; it can in general only assign a probability to a particular measurement outcome. But it is an account of the mechanism through which a particular definite outcome emerges from this indefiniteness which is now being demanded.