- Title: Frequency Stability Using MPC-based Inverter Power Control in Low-Inertia Power Systems

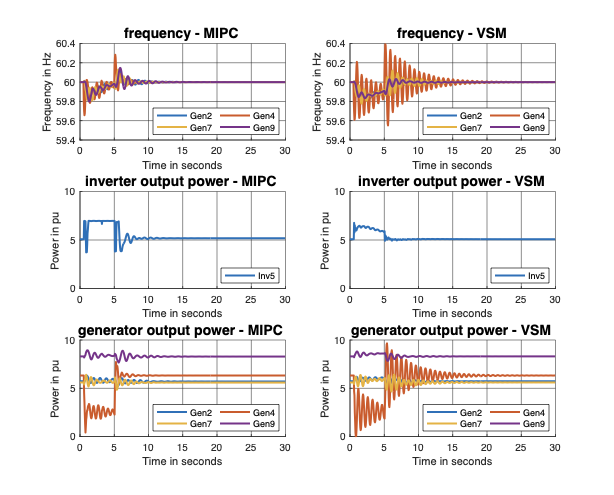

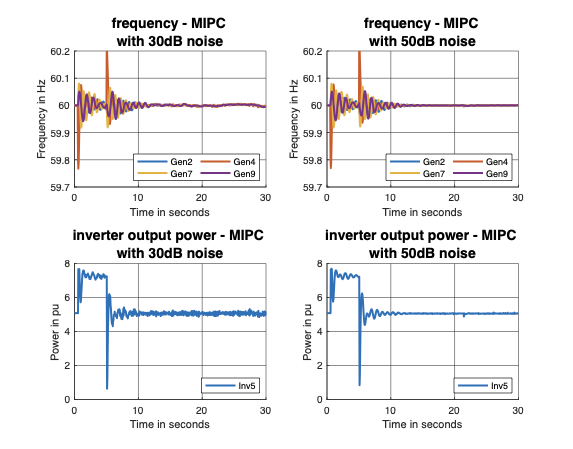

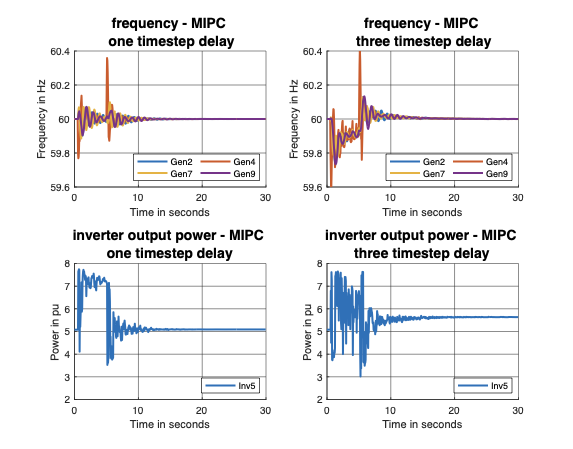

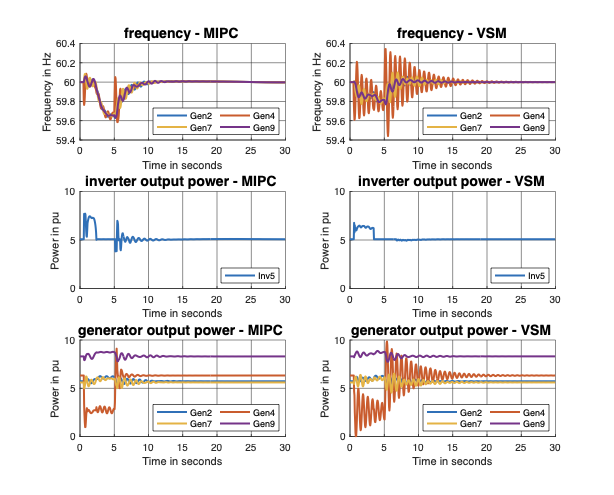

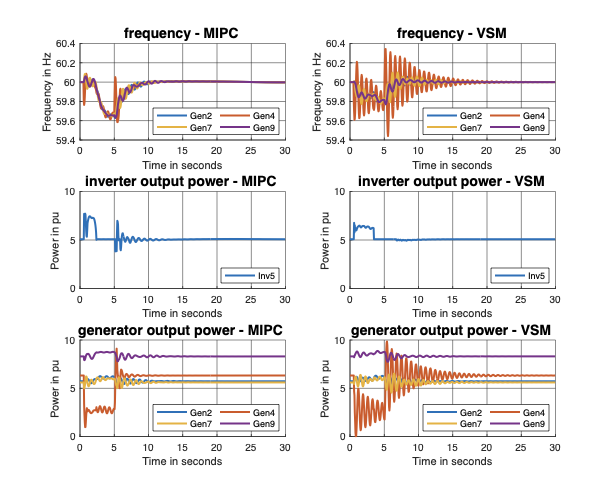

The electrical grid is evolving from a network consisting of mostly synchronous machines to a mixture of synchronous machines and inverter-based resources such as wind, solar, and energy storage. This transformation has led to a decrease in mechanical inertia, which necessitate a need for the new resources to provide frequency responses through their inverter interfaces. In this paper we proposed a new strategy based on model predictive control to determine the optimal active-power set-point for inverters in the event of a disturbance in the system. Our framework explicitly takes the hard constraints in power and energy into account, and we show that it is robust to measurement noise, limited communications and delay by using an observer to estimate the model mismatches in real-time. We demonstrate the proposed controller significantly outperforms an optimally tuned virtual synchronous machine on a standard 39-bus system under a number of scenarios. In turn, this implies optimized inverter-based resources can provide better frequency responses compared to conventional synchronous machines.

This paper introduces a new methodology for controlling the active power of inverters in low-inertia power systems using Model Predictive Control (MPC). The electric grid is transitioning from a network dominated by synchronous machines to one that includes both synchronous machines and inverter-based resources such as wind, solar, and energy storage. This shift has led to reduced mechanical inertia, necessitating the need for new resources to provide frequency responses through their inverter interfaces.

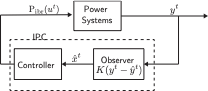

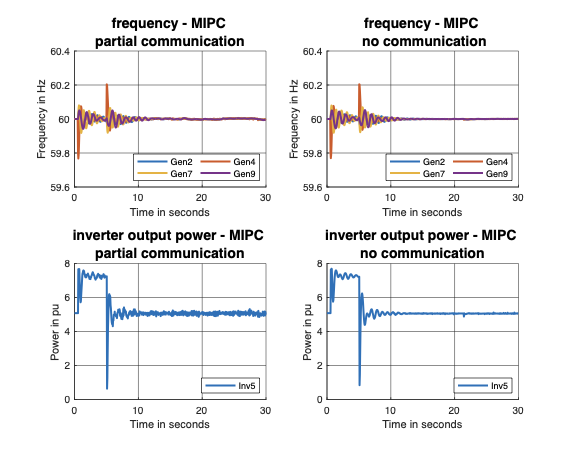

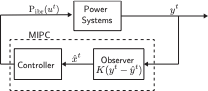

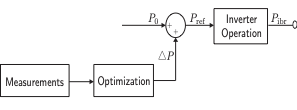

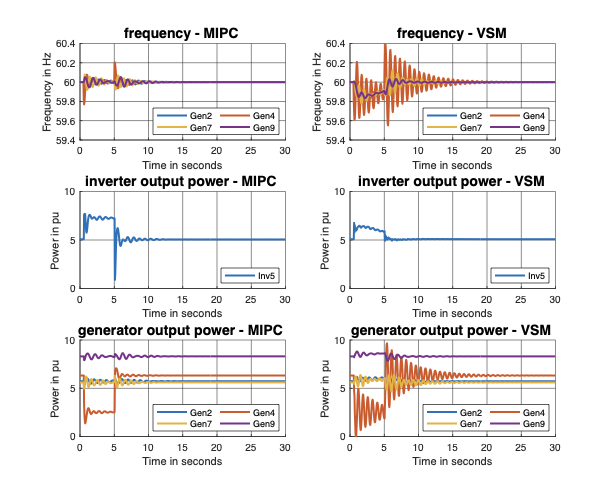

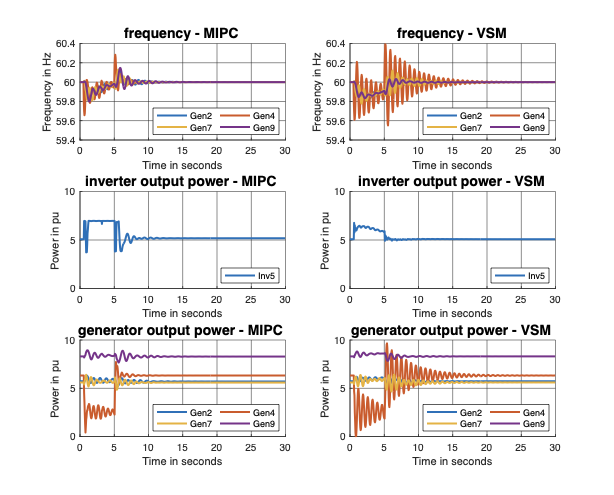

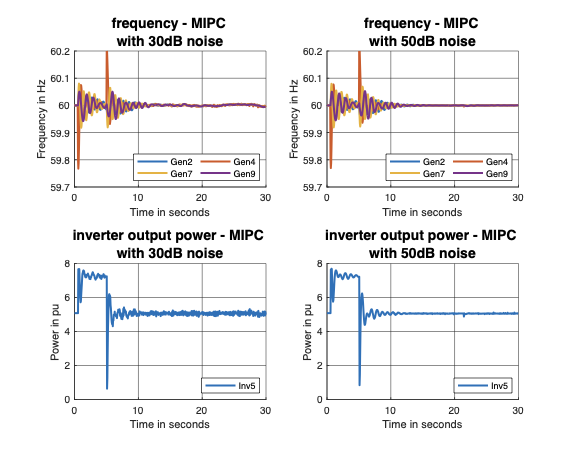

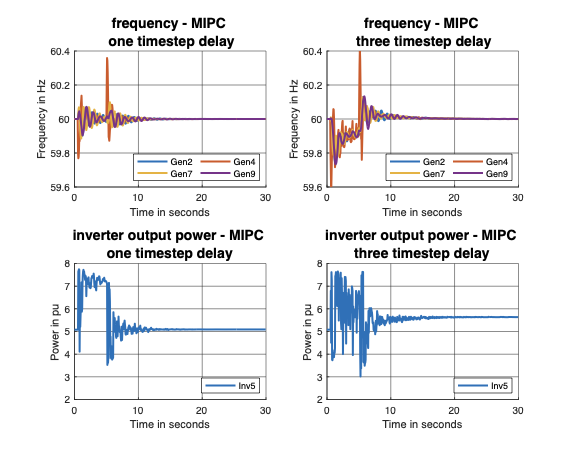

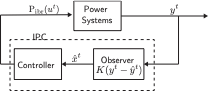

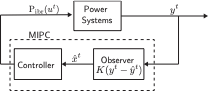

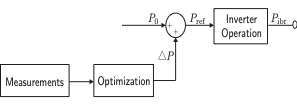

The authors propose an MPC-based approach called MPC-Based Inverter Power Control (MIPC). MIPC aims to determine the optimal active power set-point of inverters during disturbances by simulating system dynamics over a finite horizon and optimizing these set-points. This method explicitly includes hard constraints on power and energy, providing robustness against measurement noise and communication delays.

The results demonstrate that the proposed MIPC significantly outperforms optimally tuned Virtual Synchronous Machines (VSMs) in various scenarios across a standard 39-bus system, even under limited communications and large measurement noises. This study highlights the potential for optimized inverter-based resources to offer superior frequency regulation compared to conventional synchronous machines.

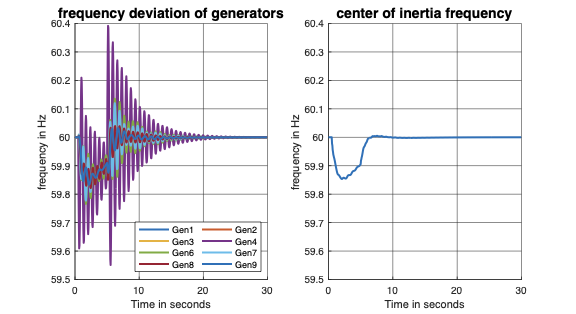

The electric grid has been undergoing a transition from a network with

dynamics fully governed by synchronous machines to a mixed-source

network with dynamics governed by both synchronous machines and

inverter-based resources (IBRs). This transition is marked by a

reduction in the amount of mechanical inertia in the system, which has

led to more pronounced frequency responses to disturbances and faults in

the grid . At the same time, by the virtue of the speed of power

electronic circuits, IBRs such as solar, wind and energy storage have

the capability to respond to frequency changes in the grid at a much

faster rate than traditional generators with rotating masses. The

challenge of how to best utilize these new capabilities has spurred much

research interest in the last few years (e.g., see and the references

within).

Various control strategies that utilizes the IBRs in providing frequency

regulation services has been proposed. The goal of these strategies is

to design the active power response of the IBRs to changes in frequency,

such that some frequency response objective is minimized. For example,

standard objectives of interests are the magnitude of the frequency

deviation, the rate of change of frequency (ROCOF) and the settling

time. A unique challenge in the control of IBRs is that they tend to

face much tighter limits than conventional machines. For example, solar

and wind resources cannot increase their power output beyond the maximum

power tracking point, which introduces a hard (and asymmetrical)

constraint on the action of the inverters. For a storage unit, it has

only a limited amount of energy that can be used to respond to a

disturbance.

Of the varying control strategies proposed for IBRs, Droop Control and

Virtual Synchronous Machines (VSMs) are the most popular as they

function by mimicking the frequency-power dynamic response of a

synchronous machine. As suggested by their names, droop control

injects/absorbs an amount of active power in proportion to the frequency

deviation, and VSM, in its basic configuration, acts as a second order

oscillator to provide inertia and damping to the grid. The parameters

(droop slope, inertia and damping constants) used in these strategies

can be optimized using a number of techniques .

The structural simplicity of VSMs also leads to a fundamental

limitation . Since there are only two parameters to tune (inertia and

damping) in the basic VSM configuration, there is an inherent trade-off

between different objectives and there is no choice of parameters that

will make the frequency deviation, ROCOF, and settling time small at the

same time . While the performance of the VSM can be enhanced by

incorporating virtual governors, virtual exciters and other power

systems controllers in their virtual form , it difficult to tune the

multiple parameters of the combined virtual controller simultaneously,

since the performance of one might negatively affect the other. In

addition, it is also difficult to include hard constraints, since simply

thresholding the output once the constraints are reached tend to lead to

very poor performances . Adaptive rules can be used to alleviate this

drawback somewhat, and works in change the parameter based on the

measured frequency deviation and ROCOF values. However, it is difficult

to find an optimal rule to update these parameters in real-time.

In this work, we propose a novel control strategy, based on model

predictive control (MPC), called the MPC-based Inverter Power Control

(MIPC). We explicitly formulate the problem of finding the optimal

active power set-point of an IBR to minimize the frequency deviation and

the ROCOF. It turns out that this formulation also implicitly minimizes

the systems settling time. More specifically, at any timestep, we

simulate the dynamics of the systems for a finite horizon, then find the

best set-points that optimizes the objective over that horizon. The

first action is then adopted for the current timestep, and the process

repeats. Our approach is similar in spirit to the ones in since an

objective is optimized in an online fashion. However, instead of

optimizing the parameters, we directly find the best power set-points.

This approach turns out to provide both an easier optimization problem

and better control performances. Namely, the hard constraints on the

IBRs are explicitly included in the optimization process.

A requirement of MPC is that the IBR must have a model of the system to

be optimized. If wide-area measurements are available, then the system

states can be obtained from these measurements . In some systems, only a

limited buses are equipped with these measurement devices (e.g. PMUs).

We show that our proposed MIPC framework is still applicable to these

systems by building an observer to estimate unmeasured disturbances and

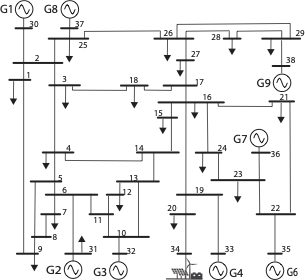

states. Through simulation studies, we show that the MIPC strictly

outperforms optimally tuned VSMs for the IEEE 39-bus system, even under

limited communication and large measurement noises.

This proposed controller finds practical application by enhancing the

capability of the IBRs to participate in providing frequency regulation

services. The additional power required can be obtained by running solar

below its maximum power point to create sufficient headroom, utilizing

the inertia from the decoupled rotating wind turbine and, leveraging on

the stored energy in a battery. By explicitly considering hard

constraints and costs on energy and power in the MPC formulation,

economic considerations can be accounted for.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section

12 defines the models used in this

paper. Section 13 presents the design and formulation

of the MIPC algorithm. Section

14 presents the state and disturbance

observer design. Section

15 compares the performances of

MIPC to VSMs in a standard test system.

Section 16 concludes the paper.

We denote the real line by $`\mathbb{R}`$, the cardinality of a set

$`\mathcal{S}`$ as $`\vert \mathcal{S} \vert`$, the $`n \times n`$

identity and zero matrices as $`\vect{I}_n`$ and $`\vect{0}_n`$,

respectively. Matrices and vectors are denoted by a bold-faced

variables.

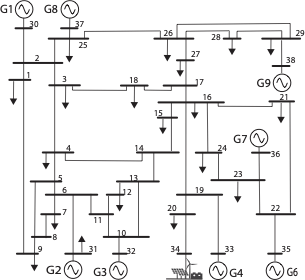

System Structure

Steady state conditions in a power systems are achieved when there is a

balance between the power produced by the generating sources and the

power consumed by loads and lossy components. For stability analysis,

the entire system can be reduced to an equivalent network via Kron

reduction . This eliminates passive and non-dynamic load buses and

leaves only buses with at least one generating source connected. With

this in place, frequency stability analysis can be carried out, with the

frequency dynamics governed by the reactions of buses to active power

imbalances in the system.

In this work, we assume the availability of state variables and network

information for control purposes. In a later section, we will relax this

assumption to partial availability of state variables from some

generators.

Because the generators and IBRs had different dynamics, we denote their

sets by $`\mathcal{G}`$ and $`\mathcal{I}`$, respectively. Note that the

total number of generating sources in the network is

$`\mathcal{N} := \mathcal{G} \cup \mathcal{I}`$.

Synchronous Machines

The rotor dynamics of each synchronous generator in a given power system

is governed by the well-known swing equation . Here we adopt a

discretized version of the equations, which in per unit (p.u.) system

is:

\begin{equation}

\label{eqn:swing_rotor_dis}

\begin{aligned}

\omega^{t+1}_i & = \omega^{t}_i + \frac{h}{m_i} \left(P_{\text{m},i}^t - P_{\text{e},i}^t - d_i \omega^{t}_i \right), \\

\delta^{t+1}_i & = \omega_{\text{b}} \left(\delta^{t}_i + h \ \omega^{t+1}_i\right),

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

Click to expand and view more

$`\forall i \in \mathcal{G}`$ where $`h`$ is the step size for the

discrete simulation, $`\delta_i`$ (rad) is the rotor angle,

$`\omega = \bar{\omega}_i - \omega_0`$ is the rotor speed deviation,

$`\omega_{\text{b}}`$ is the base speed of the system, $`m_i`$ is the

inertia constant, $`d_i`$ is the damping constant, $`P_{\text{m},i}`$ is

the mechanical input power and $`P_{\text{e},i}`$ is the electric power

output of the $`i^{th}`$ machine.

The electrical output power $`P_{\text{e},i}`$ is given by the AC power

flow equation in terms of the internal emf $`\vert E_i \vert`$ and rotor

angle $`\delta_i`$:

\begin{align}

\label{eqn:pf_dis}

P_{\text{e},i}^t = \sum_{i \sim j} \vert E_i E_j \vert [g_{ij} \cos(\delta_i^t - \delta_j^t) + b_{ij}\sin(\delta_i^t - \delta_j^t)],

\end{align}

Click to expand and view more

$`\forall i,j \in \mathcal{G}`$, where $`g_{ij} + j b_{ij}`$ is the

reduced admittance between nodes $`i`$ and $`j`$. We assume the internal

emf are constant because of the actions of the exciter systems.

The nonlinearity of the AC power flow in

[eqn:pf_dis] makes

[eqn:swing_rotor_dis] difficult

to use for control applications. Linearizing

[eqn:swing_rotor_dis] around

the nominal point and using the DC power flow approximation , the bus

dynamics become:

\begin{equation}

\label{eqn:swing_lin_dis}

\begin{aligned}

\bigtriangleup \omega^{t+1}_i & = \bigtriangleup \omega^{t}_i + \frac{h}{m_i} \left(\bigtriangleup P_{\text{m},i}^t - \bigtriangleup P_{\text{e},i}^t - d_i \bigtriangleup \omega^{t}_i \right), \\

\bigtriangleup \delta^{t+1}_i & = \omega_{\text{b}} \left(\bigtriangleup \delta^{t}_i + h \ \bigtriangleup \omega^{t+1}_i \right),

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

Click to expand and view more

where

$`\bigtriangleup P_{\text{e},i}^t = \sum_{i \sim j} b_{ij} \bigtriangleup \delta^t_{ij}`$

is the dc power flow between 2 buses. We model changes to the mechanical

input power $`\bigtriangleup P_{\text{m},i}^t`$ by a combination of

droop and automatic governor control (AGC) actions .

Virtual Synchronous Machine (VSM)

From the network point of view, the grid-connected IBR is seen as

producing a constant power according to its predetermined set-point and

fast dynamics governed by closed-loop controls actions . When configured

in the grid-following mode, these controls help maintain the output

power of the IBRs while remaining synchronized to the terminal voltage

set by the grid. For system analysis, the inverter can be modeled as a

voltage source behind a reactance, much like a synchronous machine.

In the event of a power imbalance in the network reflected by a

frequency deviation, an inverter does not have a “natural” response to

frequency deviation as synchronous machines does since they are made of

power electronics components and have no rotating mass. To elicit some

response, an additional control loop is therefore needed to enable the

inverters to participate in frequency control by changing the power

set-point of the inverter based on frequency measurements. The concept

of virtual synchronous machine (VSM) has been proposed in literature to

provide this additional control loop and it comes in different

configurations . The basic idea is to mimic the behavior of a

synchronous machine’s response to a frequency deviation by choosing

appropriate gains corresponding to the inertia and damping of the

machines and producing power proportional to the ROCOF and frequency

deviation. Since the response of the inverter is entirely digital, it

can be programmed with almost arbitrary functions.

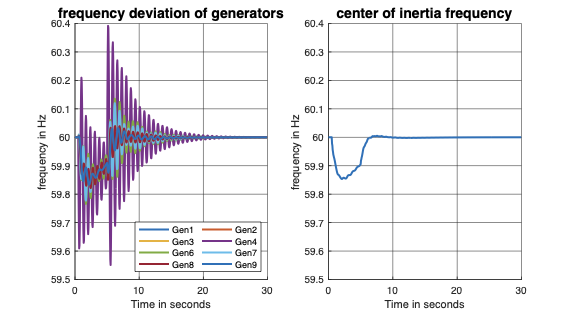

In this work, we adopt the VSM configuration in , where the additional

power required to combat a frequency deviation is computed using:

\begin{equation}

\label{eqn:p_add}

\begin{aligned}

\bigtriangleup P = \bigtriangleup P_{\text{km}} + \bigtriangleup P_{\text{kd}}= K_\text{m} \frac{d \bigtriangleup \omega_{\text{ibr}}}{dt} + K_\text{d} \bigtriangleup \omega_{\text{ibr}}.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

Click to expand and view more

The local frequency at the IBR node

$`\bigtriangleup \omega_{\text{ibr}}`$ is approximated by the center of

inertia (COI) frequency , which is an inertia-weighted average frequency

given by:

\begin{equation}

\label{eqn:local_freq}

\begin{aligned}

\bigtriangleup \omega_{ibr} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n m_i \bigtriangleup \omega_i}{\sum_{i=1}^n m_i}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

Click to expand and view more

where $`n = \vert \mathcal{G} \vert`$, $`\bigtriangleup \omega_i`$ is

the rotor speed deviation, and $`m_i`$ is the inertia constant of the

$`i^{th}`$ synchronous generators in the network. The gains

$`K_\text{m}`$ and $`K_\text{d}`$ in

[eqn:p_add] represent the virtual inertia

and damping constants respectively. In contrast to synchronous machines

where the constants are decided by the physical parameters, these

constants of the VSM can be optimized over .

In the next section, we fully leverage the flexibility of the power

electronic interfaces using a MPC framework.

The copyright of this content belongs to the respective researchers. We deeply appreciate their hard work and contribution to the advancement of human civilization.