A Review of Autonomous Driving Current Practices and Emerging Technologies

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: A Survey of Autonomous Driving Common Practices and Emerging Technologies- ArXiv ID: 1906.05113

- Date: 2020-04-06

- Authors: Ekim Yurtsever, Jacob Lambert, Alexander Carballo, Kazuya Takeda

📝 Abstract

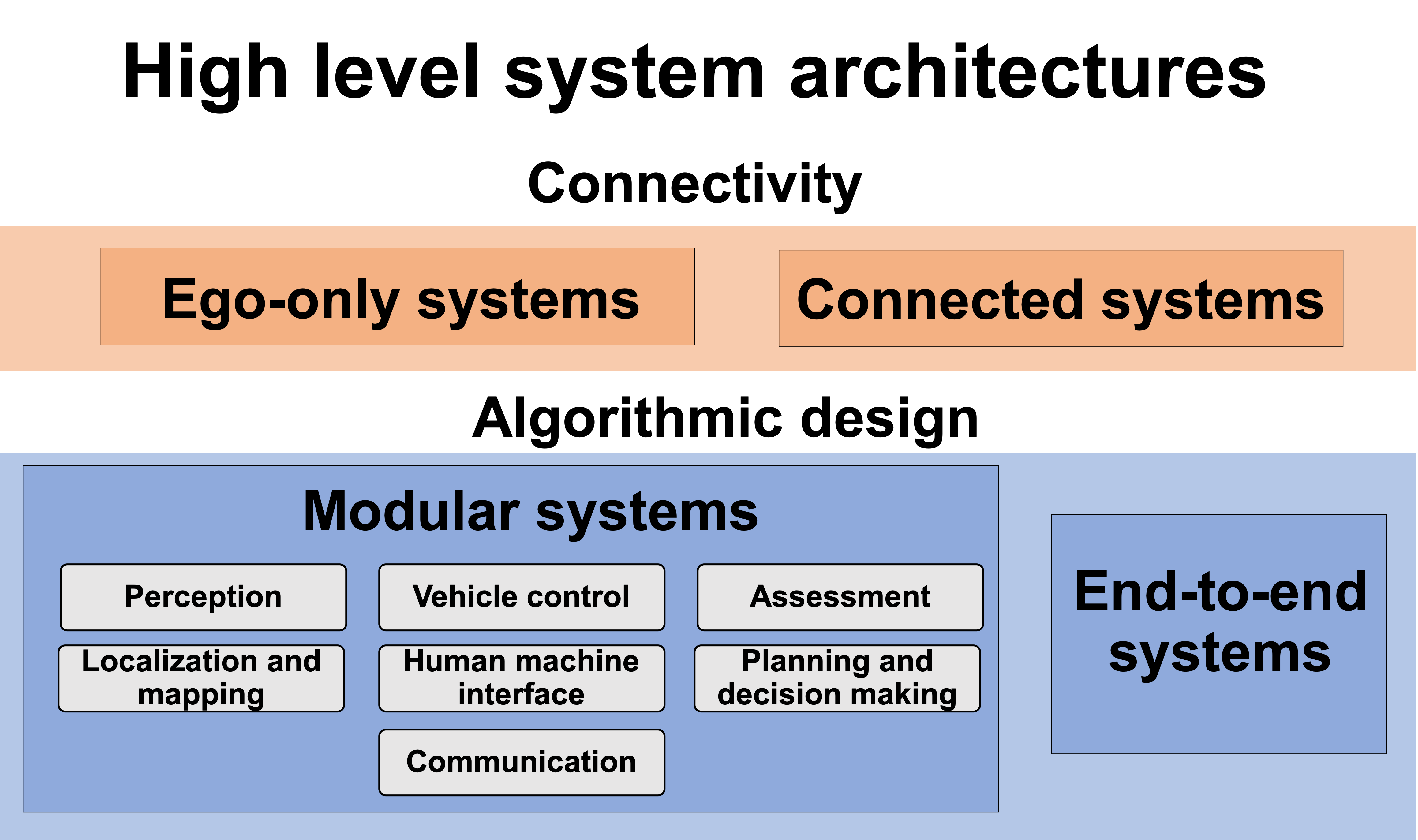

Automated driving systems (ADSs) promise a safe, comfortable and efficient driving experience. However, fatalities involving vehicles equipped with ADSs are on the rise. The full potential of ADSs cannot be realized unless the robustness of state-of-the-art improved further. This paper discusses unsolved problems and surveys the technical aspect of automated driving. Studies regarding present challenges, high-level system architectures, emerging methodologies and core functions: localization, mapping, perception, planning, and human machine interface, were thoroughly reviewed. Furthermore, the state-of-the-art was implemented on our own platform and various algorithms were compared in a real-world driving setting. The paper concludes with an overview of available datasets and tools for ADS development.💡 Summary & Analysis

This paper explores the technical aspects and unresolved issues of autonomous driving systems (ADS). The research focuses on improving robustness in ADS, which is crucial for achieving safe and efficient automated driving. Key functionalities such as localization, mapping, perception, planning, and human-machine interface are analyzed in detail. Through a thorough review of current challenges, high-level system architectures, emerging methodologies, and core functions, the paper aims to provide comprehensive insights into the state-of-the-art ADS technologies.The primary goal is to identify gaps in research and propose solutions by comparing various algorithms in real-world driving scenarios. The findings suggest that interdisciplinary collaboration between scientific disciplines and new technologies can address remaining challenges, paving the way for safer roads in the near future.

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

In this survey on automated driving systems, we outlined some of the key innovations as well as existing systems. While the promise of automated driving is enticing and already marketed to consumers, this survey has shown there remains clear gaps in the research. Several architecture models have been proposed, from fully modular to completely end-to-end, each with their own shortcomings. The optimal sensing modality for localization, mapping and perception is still disagreed upon, algorithms still lack accuracy and efficiency, and the need for a proper online assessment has become apparent. Less than ideal road conditions are still an open problem, as well as dealing with intemperate weather. Vehicle-to-vehicle communication is still in its infancy, while centralized, cloud-based information management has yet to be implemented due to the complex infrastructure required. Human-machine interaction is an under-researched field with many open problems.

The development of automated driving systems relies on the advancements of both scientific disciplines and new technologies. As such, we discussed the recent research developments which are likely to have a significant impact on automated driving technology, either by overcoming the weakness of previous methods or by proposing an alternative. This survey has shown that through inter-disciplinary academic collaboration and support from industries and the general public, the remaining challenges can be addressed. With directed efforts towards ensuring robustness at all levels of automated driving systems, safe and efficient roads are just beyond the horizon.

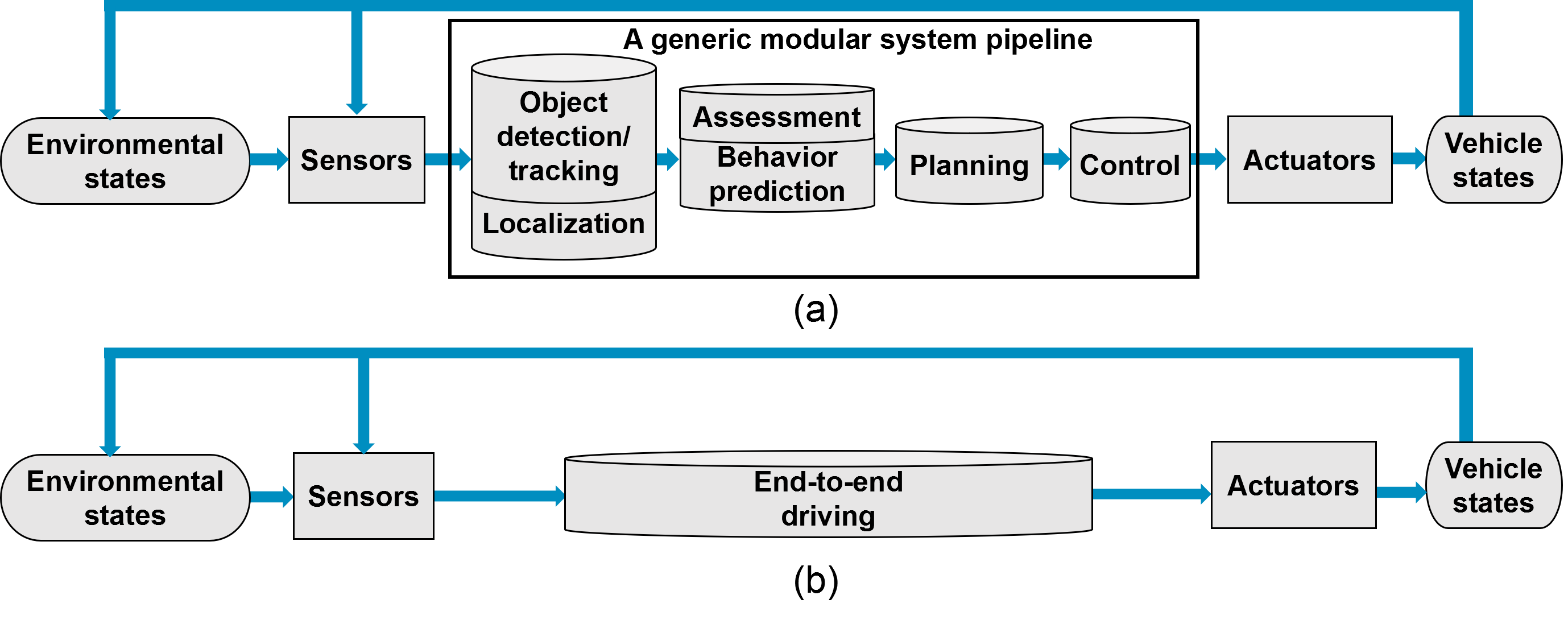

Perception

Perceiving the surrounding environment and extracting information which may be critical for safe navigation is a critical objective for ADS. A variety of tasks, using different sensing modalities, fall under the category of perception. Building on decades of computer vision research, cameras are the most commonly used sensor for perception, with 3D vision becoming a strong alternative/supplement.

The reminder of this section is divided into core perception tasks. We discuss image-based object detection in 7.1.1, semantic segmentation in 7.1.2, 3D object detection in 7.1.3, road and lane detection in 7.3 and object tracking in 7.2.

Detection

Image-based Object Detection

| Architecture | Num. Params | Num. | ImageNet1K | ||

| ($`\times 10^6`$) | Layers | Top 5 Error % | |||

| Incept.ResNet v2 | 30 | 95 | 4.9 | ||

| Inception v4 | 41 | 75 | 5 | ||

| ResNet101 | 45 | 100 | 6.05 | ||

| DenseNet201 | 18 | 200 | 6.34 | ||

| YOLOv3-608 | 63 | 53+1 | 6.2 | ||

| ResNet50 | 26 | 49 | 6.7 | ||

| GoogLeNet | 6 | 22 | 6.7 | ||

| VGGNet16 | 134 | 13+2 | 6.8 | ||

| AlexNet | 57 | 5+2 | 15.3 | ||

Comparison of 2D bounding box estimation architectures on the test set of ImageNet1K, ordered by Top 5% error. Number of parameters (Num. Params) and number of layers (Num. Layers), hints at the computational cost of the algorithm.

Object detection refers to identifying the location and size of objects of interest. Both static objects, from traffic lights and signs to road crossings, and dynamic objects such as other vehicles, pedestrians or cyclists are of concern to ADSs. Generalized object detection has a long-standing history as a central problem in computer vision, where the goal is to determine if objects of specific classes are present in an image, then to determine their size via a rectangular bounding box. This section mainly discusses state-of-the-art object detection methods, as they represent the starting point of several other tasks in an ADS pipe, such as object tracking and scene understanding.

Object recognition research started more than 50 years ago, but only recently, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, has algorithm performance reached a level of relevance for driving automation. In 2012, the deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) AlexNet shattered the ImageNet image recognition challenge. This resulted in a near complete shift of focus to supervised learning and in particular deep learning for object detection. There exists a number of extensive surveys on general image-based object detection. Here, the focus is on the state-of-the-art methods that could be applied to ADS.

While state-of-the-art methods all rely on DCNNs, there currently exist a clear distinction between them:

-

Single stage detection frameworks use a single network to produce object detection locations and class prediction simultaneously.

-

Region proposal detection frameworks use two distinct stages, where general regions of interest are first proposed, then categorized by separate classifier networks.

Region proposal methods are currently leading detection benchmarks, but at the cost requiring high computation power, and generally being difficult to implement, train and fine-tune. Meanwhile, single stage detection algorithms tend to have fast inference time and low memory cost, which is well-suited for real-time driving automation. YOLO (You Only Look Once) is a popular single stage detector, which has been improved continuously. Their network uses a DCNN to extract image features on a coarse grid, significantly reducing the resolution of the input image. A fully-connected neural network then predicts class probabilities and bounding box parameters for each grid cell and class. This design makes YOLO very fast, the full model operating at 45 FPS and a smaller model operating at 155 FPS for a small accuracy trade-off. More recent versions of this method, YOLOv2, YOLO9000 and YOLOv3 briefly took over the PASCAL VOC and MS COCO benchmarks while maintaining low computation and memory cost. Another widely used algorithm, even faster than YOLO, is the Single Shot Detector (SSD), which uses standard DCNN architectures such as VGG to achieve competitive results on public benchmarks. SSD performs detection on a coarse grid similar to YOLO, but also uses higher resolution features obtained early in the DCNN to improve detection and localization of small objects.

Considering both accuracy and computational cost is essential for detection in ADS; the detection needs to be reliable, but also operate better than real-time, to allow as much time as possible for the planning and control modules to react to those objects. As such, single stage detectors are often the detection algorithms of choice for ADSs. However, as shown in 1, region proposal networks (RPN), used in two-stage detection frameworks, have proven to be unmatched in terms of object recognition and localization accuracy, and computational cost has improved greatly in recent years. They are also better suited for other tasks related to detection, such as semantic segmentation as discussed in 7.1.2. Through transfer learning, RPNs achieving multiple perception tasks simultaneously are become increasingly feasible for online applications. RPNs can replace single stage detection networks for ADS applications in the near future.

Omnidirectional and event camera-based perception: 360 degree vision, or at least panoramic vision, is necessary for higher levels of automation. This can be achieved through camera arrays, though precise extrinsic calibration between each camera is then necessary to make image stitching possible. Alternatively, omnidirectional cameras can be used, or a smaller array of cameras with very wide angle fisheye lenses. These are however difficult to intrinsically calibrate; the spherical images are highly distorted and the camera model used must account for mirror reflections or fisheye lens distortions, depending on the camera model producing the panoramic images. The accuracy of the model and calibration dictates the quality of undistorted images produced, on which the aforementioned 2D vision algorithms are used. An example of fisheye lenses producing two spherical images then combined into one panoramic image is shown in [fig:ricoh]. Some distortions inevitably remain, but despite these challenges in calibration, omnidirectional cameras have been used for many applications such as SLAM and 3D reconstruction .

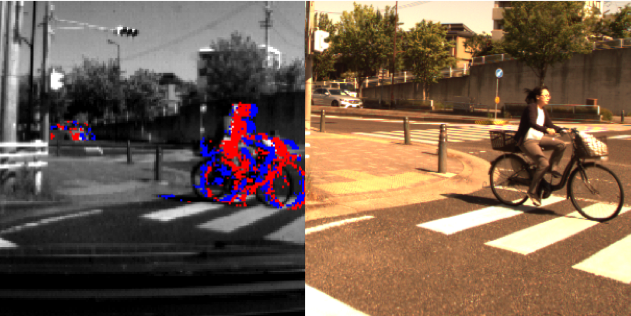

Event cameras are a fairly new modality which output asynchronous events usually caused by movement in the observed scene, as shown in [fig:event]. This makes the sensing modality interesting for dynamic object detection. The other appealing factor is their response time on the order of microseconds, as frame rate is a significant limitation for high-speed driving. The sensor resolution remains an issue, but new models are rapidly improving. They have been used for a variety of applications closely related to ADS. A recent survey outlines progress in pose estimation and SLAM, visual-inertial odometry and 3D reconstruction, as well as other applications. Most notably, a dataset for end-to-end driving with event cameras was recently published, with preliminary experiments showing that the output of an event camera can, to some extent, be used to predict car steering angle .

Poor Illumination and Changing Appearance: The main drawback with using camera is that changes in lighting conditions can significantly affect their performance. Low light conditions are inherently difficult to deal with, while changes in illumination due to shifting shadows, intemperate weather, or seasonal changes, can cause algorithms to fail, in particular supervised learning methods. For example, snow drastically alters the appearance of scenes and hides potentially key features such as lane markings. An easy alternative is to use an alternate sensing modalities for perception, but lidar also has difficulties with some weather conditions like fog and snow, and radars lack the necessary resolution for many perception tasks. A sensor fusion strategy is often employed to avoid any single point of failure.

Thermal imaging through infrared sensors are also used for object detection in low light conditions, which is particularly effective for pedestrian detection. Camera-only methods which attempt to deal with dynamic lighting conditions directly have also been developed. Both attempting to extract lighting invariant features and assessing the quality of features have been proposed. Pre-processed, illumination invariant images have applied to ADS and were shown to improve localization, mapping and scene classification capabilities over long periods of time. Still, dealing with the unpredictable conditions brought forth by inadequate or changing illumination remains a central challenge preventing the widespread implementation of ADS.

Semantic Segmentation

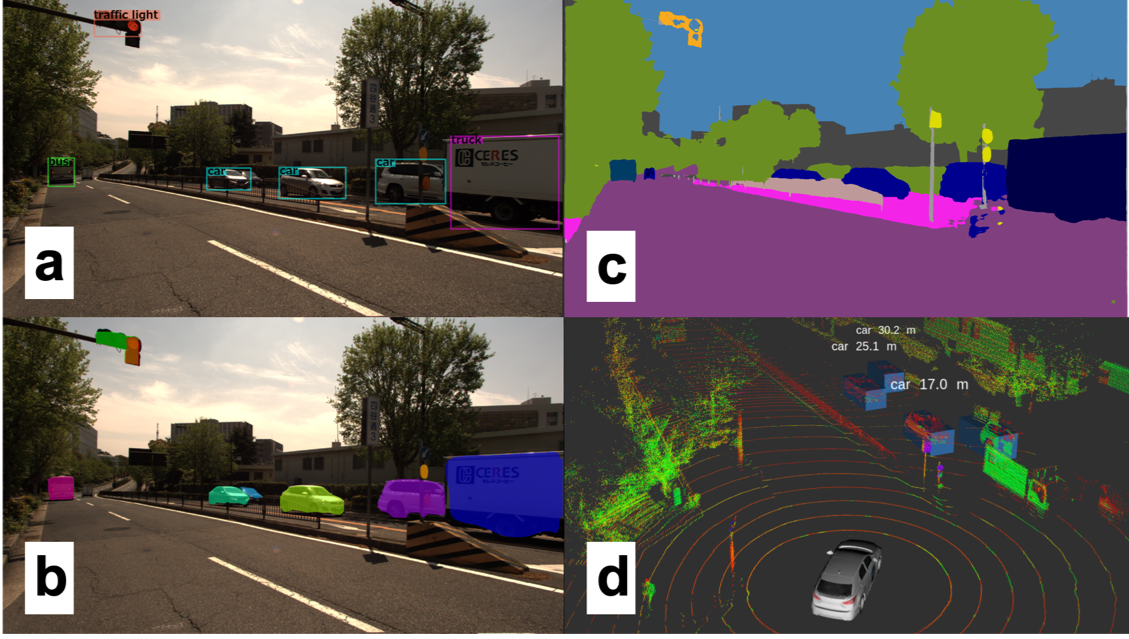

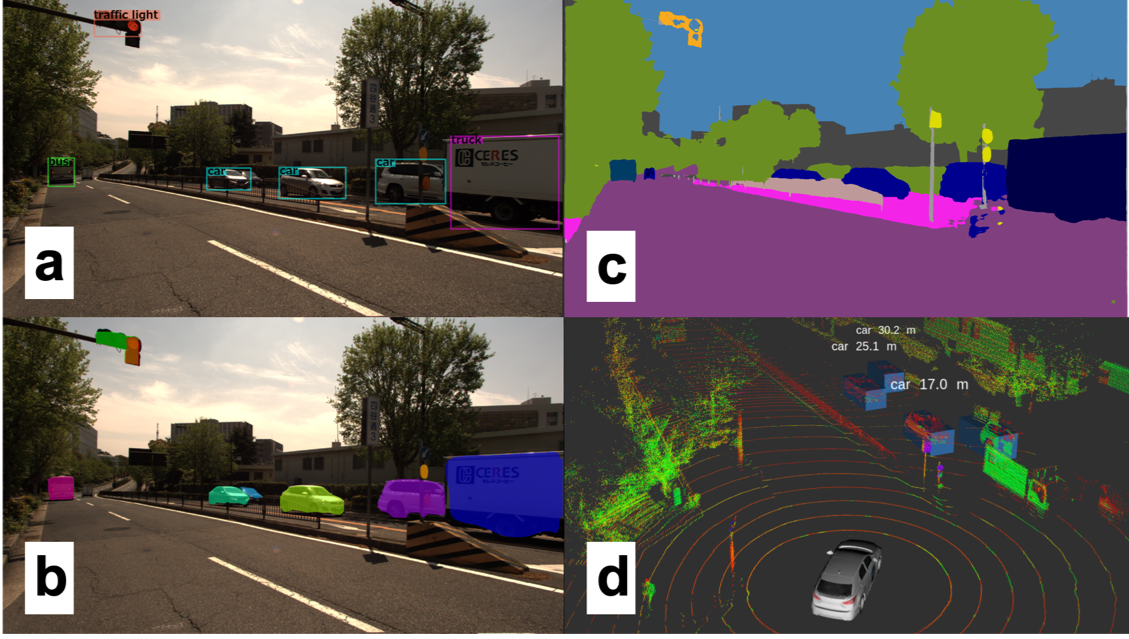

Beyond image classification and object detection, computer vision research has also tackled the task of image segmentation. This consists of classifying each pixel of an image with a class label. This task is of particular importance to driving automation as some objects of interest are poorly defined by bounding boxes, in particular roads, traffic lines, sidewalks and buildings. A segmented scene in an urban area can be seen in 1. As opposed to semantic segmentation, which labels pixels based on a class, instance segmentation algorithms further separates instances of the same class, which is important in the context of driving automation. In other words, objects which may have different trajectories and behaviors must be differentiated from each other. We used the COCO dataset to train the instance segmentation algorithm Mask R-CNN with the sample result shown in 1.

Segmentation has recently become feasible for real-time applications. Generally, developments in this field progress in parallel with image-based object detection. The aforementioned Mask R-CNN is a generalization of Faster R-CNN. The multi-task R-CNN network can achieve accurate bounding box estimation and instance segmentation simultaneously and can also be generalized to other tasks like pedestrian pose estimation with minimal domain knowledge. Running at 5 fps means it is approaching the area of real-time use for ADS.

Unlike Mask-RCNN’s architecture which is more akin to those used for object detection through its use of region proposal networks, segmentation networks usually employ a combination of convolutions for feature extraction. Those are followed by deconvolutions, also called transposed convolutions, to obtain pixel resolution labels. Feature pyramid networks are also commonly used, for example in PSPNet , which also introduced dilated convolutions for segmentation. This idea of sparse convolutions was then used to develop DeepLab, with the most recent version being the current state-of-the-art for object segmentation. We employed DeepLab with our ADS and a segmented frame is shown in 1.

While most segmentation networks are as of yet too slow and computationally expensive to be used in ADS, it is important to notice that many of these segmentations networks are initially trained for different tasks, such as bounding box estimation, then generalized to segmentation networks. Furthermore, these networks were shown to learn universal feature representations of images, and can be generalized for many tasks. This suggests the possibility that single, generalized perception networks may be able to tackle all perception tasks required for an ADS.

3D Object Detection

Given their affordability, availability and widespread research, cameras are used by nearly all algorithms presented so far as the primary perception modality. However, cameras have limitations that are critical to ADS. Aside from illumination which was previously discussed, camera-based object detection occurs in the projected image space and therefore the scale of the scene is unknown. To make use of this information for dynamic driving tasks like obstacle avoidance, it is necessary to bridge the gap from 2D image-based detection to the 3D, metric space. Depth estimation is therefore necessary, which is in fact possible with a single camera though stereo or multi-view systems are more robust. These algorithms necessarily need to solve an expensive image matching problem, which adds a significant amount of processing cost to an already complex perception pipeline.

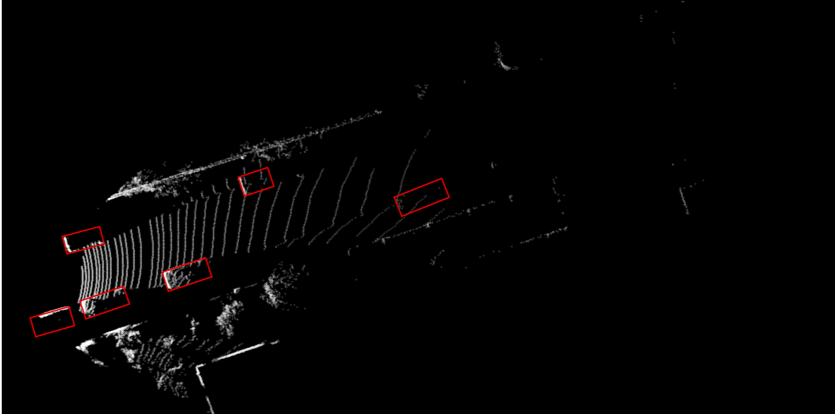

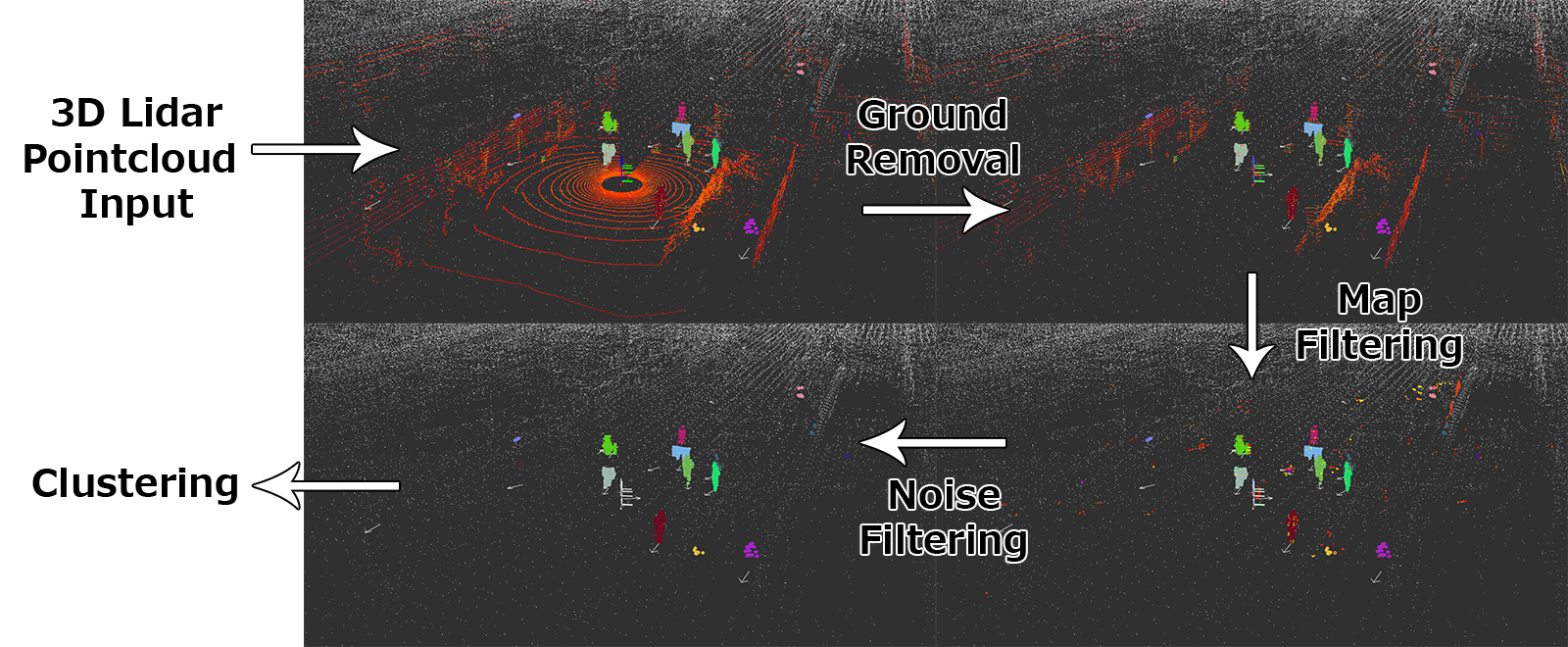

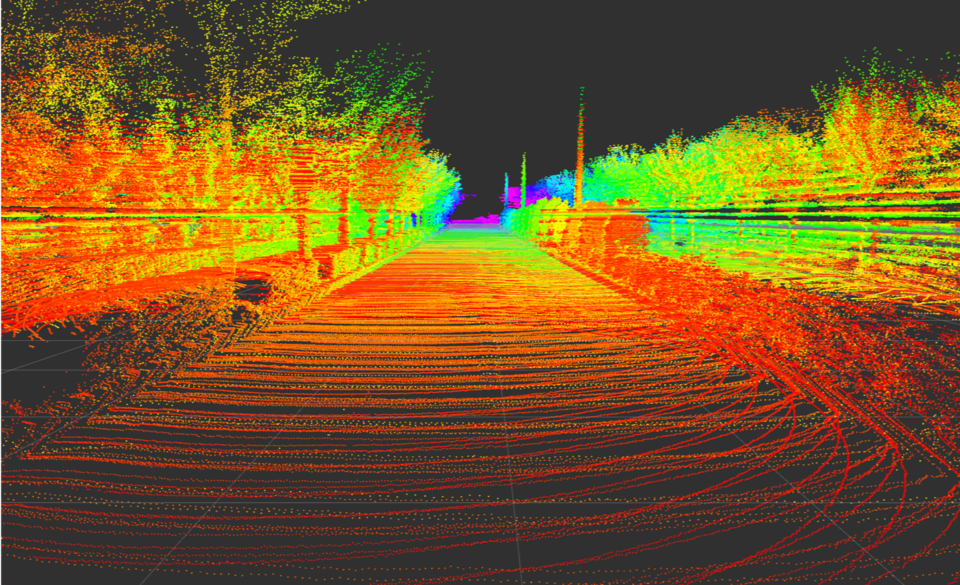

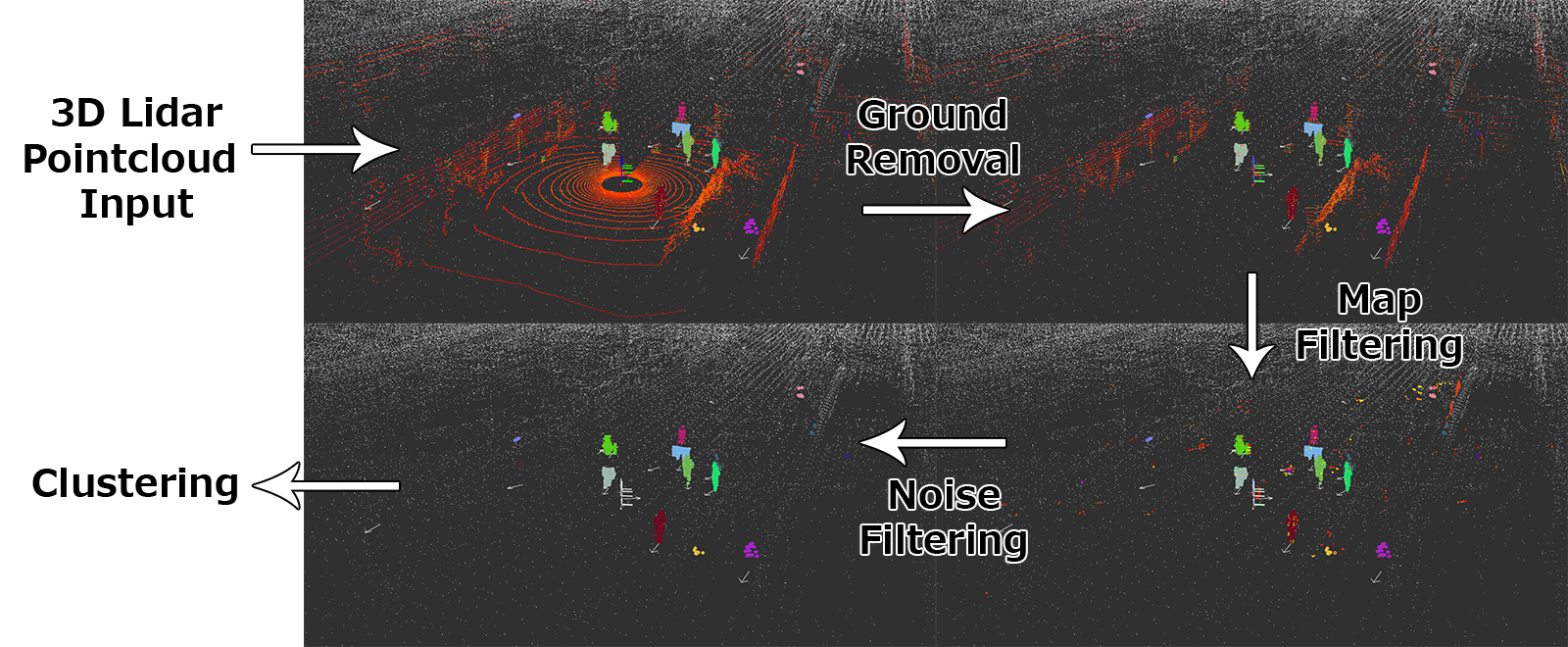

A relatively new sensing modality, the 3D lidar, offers an alternative for 3D perception. The 3D data collected inherently solves the scale problem, and since they have their own emission source, they are far less dependable on lighting condition, and less susceptible to intemperate weather. The sensing modality collects sparse 3D points representing the surfaces of the scene, as shown in 2, which are challenging to use for object detection and classification. The appearance of objects change with range, and after some distance, very few data points per objects are available to detect an object. This poses some challenges for detection, but since the data is a direct representation of the world, it is more easily separable. Traditional methods often use euclidean clustering or region-growing methods for grouping points into objects. This approach has been made much more robust through various filtering techniques, such as ground filtering and map-based filtering. We implemented a 3D object detection pipeline to get clustered objects from raw point cloud input. An example of this process is shown in 2.

As with image-based methods, machine learning has also recently taken over 3D detection methods. These methods have also notably been applied to RGB-D, which produce similar, but colored, point clouds; with their limited range and unreliability outdoors, RGB-D have not been used for ADS applications. A 3D representation of point data, through a 3D occupancy grid called voxel grids, was first applied for object detection in RGB-D data. Shortly thereafter, a similar approach was used on point clouds created by lidars . Inspired by image-based methods, 3D CNNs are used, despite being computationally very expensive.

The first convincing results for point cloud-only 3D bounding box estimation were produced by VoxelNet. Instead of hand-crafting input features computed during the discretization process, VoxelNet learned an encoding from raw point cloud data to voxel grid. Their voxel feature encoder (VFE) uses a fully connected neural network to convert the variable number of points in each occupied voxel to a feature vector of fixed size. The voxel grid encoded with feature vectors was then used as input to an aforementioned RPN for multi-class object detection. This work was then improved both in terms of accuracy and computational efficiency by SECOND by exploiting the natural sparsity of lidar data. We employed SECOND and a sample result is shown in 1. Several algorithms have been produced recently, with accuracy constantly improving as shown in 2, yet the computational complexity of 3D convolutions remains an issue for real-time use.

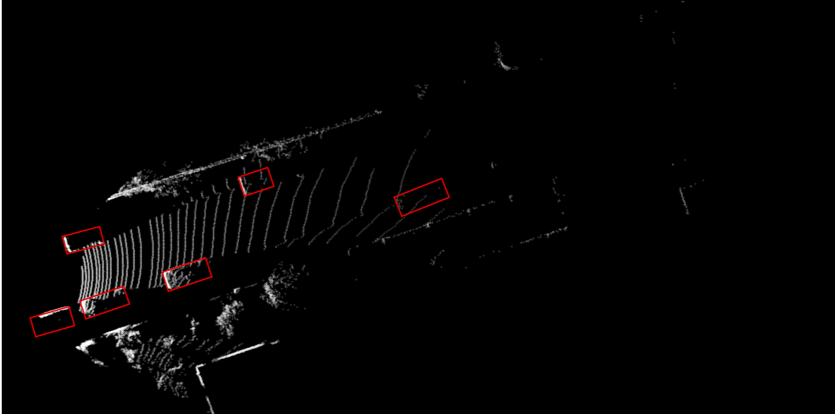

Another option for lidar-based perception is 2D projection of point cloud data. There are two main representations of point cloud data in 2D, the first being a so-called depth image shown in 3, largely inspired by camera-based methods that perform 3D object detection through depth estimation and methods that operate on RGB-D data . The VeloFCN network proposed to use single-channel depth image as input to a shallow, single-stage convolutional neural network which produced 3D vehicle proposals, with many other algorithms adopting this approach. Another use of depth image was shown for semantic classification of lidar points.

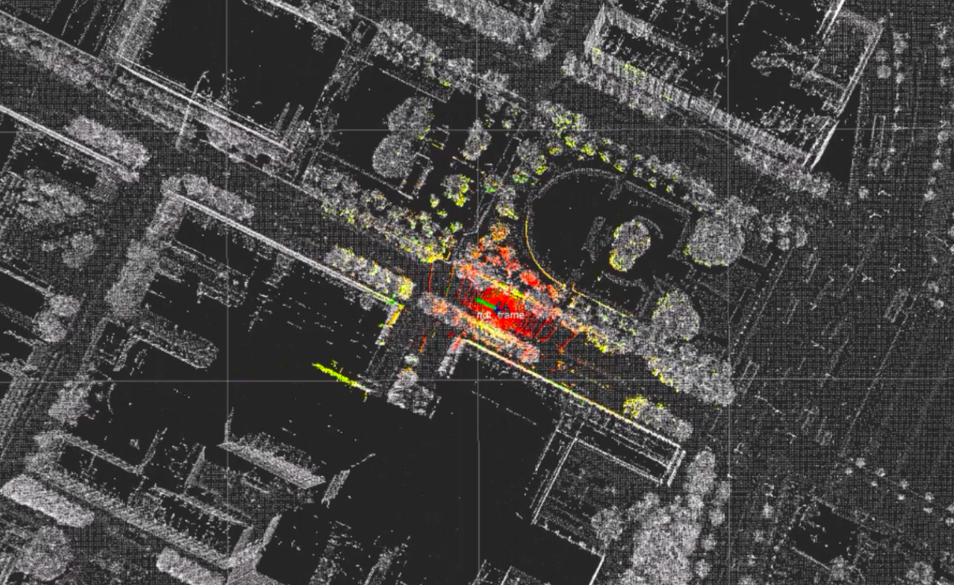

The other 2D projection that has seen increasing popularity, in part due to the new KITTI benchmark, is projection to bird’s eye view (BV) image. This is a top-view image of point clouds as shown in 4. Bird’s eye view images discretize space purely in 2D, so lidar points which vary in height alone occlude each other. The MV3D algorithm used camera images, depth images, as well as multi-channel BV images; each channel corresponding to a different range of heights, so as to minimize these occlusions. Several other works have reused camera-based algorithms and trained efficient networks for 3D object detection on 2D BV images. State-of-the-art algorithms are currently being evaluated on the KITTI dataset and nuScenes dataset as they offer labeled 3D scenes. 2 shows the leading methods on the KITTI benchmark, alongside detection times. 2D methods are far less computationally expensive, but recent methods that take point sparsity into account are real-time viable and rapidly approaching the accuracy necessary for integration in ADSs.

| Algorithm | T [s] | Easy | Moderate | Hard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PointRCNN | 0.10 | 85.9 | 75.8 | 68.3 |

| PointPillars | 0.02 | 79.1 | 75.0 | 68.3 |

| SECOND | 0.04 | 83.1 | 73.7 | 66.2 |

| IPOD | 0.20 | 82.1 | 72.6 | 66.3 |

| F-PointNet | 0.17 | 81.2 | 70.4 | 62.2 |

| VoxelNet (Lidar) | 0.23 | 77.5 | 65.1 | 57.7 |

| MV3D (Lidar) | 0.24 | 66.8 | 52.8 | 51.3 |

Average Precision (AP) in % on the KITTI 3D object detection test set car class, ordered based on moderate category accuracy. These algorithms only use pointcloud data.

Radar Radar sensors have already been used for various perception applications, in various types of vehicles, with different models operating at complementary ranges. While not as accurate as the lidar, it can detect at object at high range and estimate their velocity . The lack of precision for estimating shape of objects is a major drawback when it is used in perception systems, the resolution is simply too low. As such, it can be used for range estimation to large objects like vehicles, but it is challenging for pedestrians or static objects. Another issue is the very limited field of view of most radars, forcing a complicated array of radar sensors to cover the full field of view. Nevertheless, radar have seen widespread use as an ADAS component, for applications including proximity warning and adaptive cruise control. While radar and lidar are often seen as competing sensing modalities, they will likely be used in tandem in fully automated driving systems. Radars are very long range, have low cost and are robust to poor weather, while lidar offer precise object localization capabilities, as discussed in 6.

Another similar sensor to the radar are sonar devices, though their extremely short range of $`<2m`$ and poor angular resolution makes their use limited to very near obstacle detection .

Object Tracking

Object tracking is also often referred to as multiple object tracking (MOT) and detection and tracking of multiple objects (DATMO). For fully automated driving in complex and high speed scenarios, estimating location alone is insufficient. It is necessary to estimate dynamic objects’ heading and velocity so that a motion model can be applied to track the object over time and predict future trajectory to avoid collisions. These trajectories must be estimated in the vehicle frame to be used by planning, so range information must be obtained through multiple camera systems, lidars or radar sensors. 3D lidars are often used for their precise range information and large field of view, allowing tracking over longer periods of time. To better cope with the limitations and uncertainties of different sensing modalities, a sensor fusion strategy is often use for tracking.

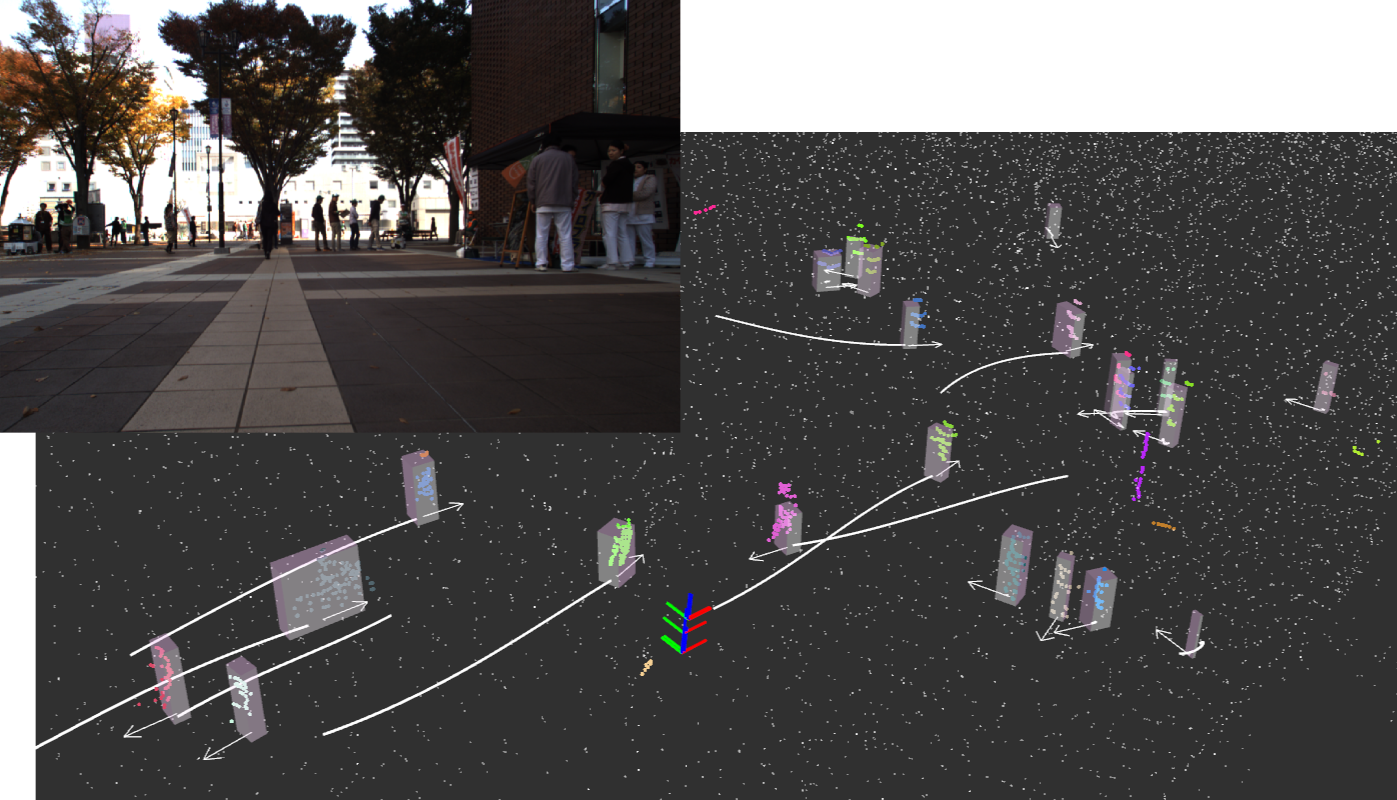

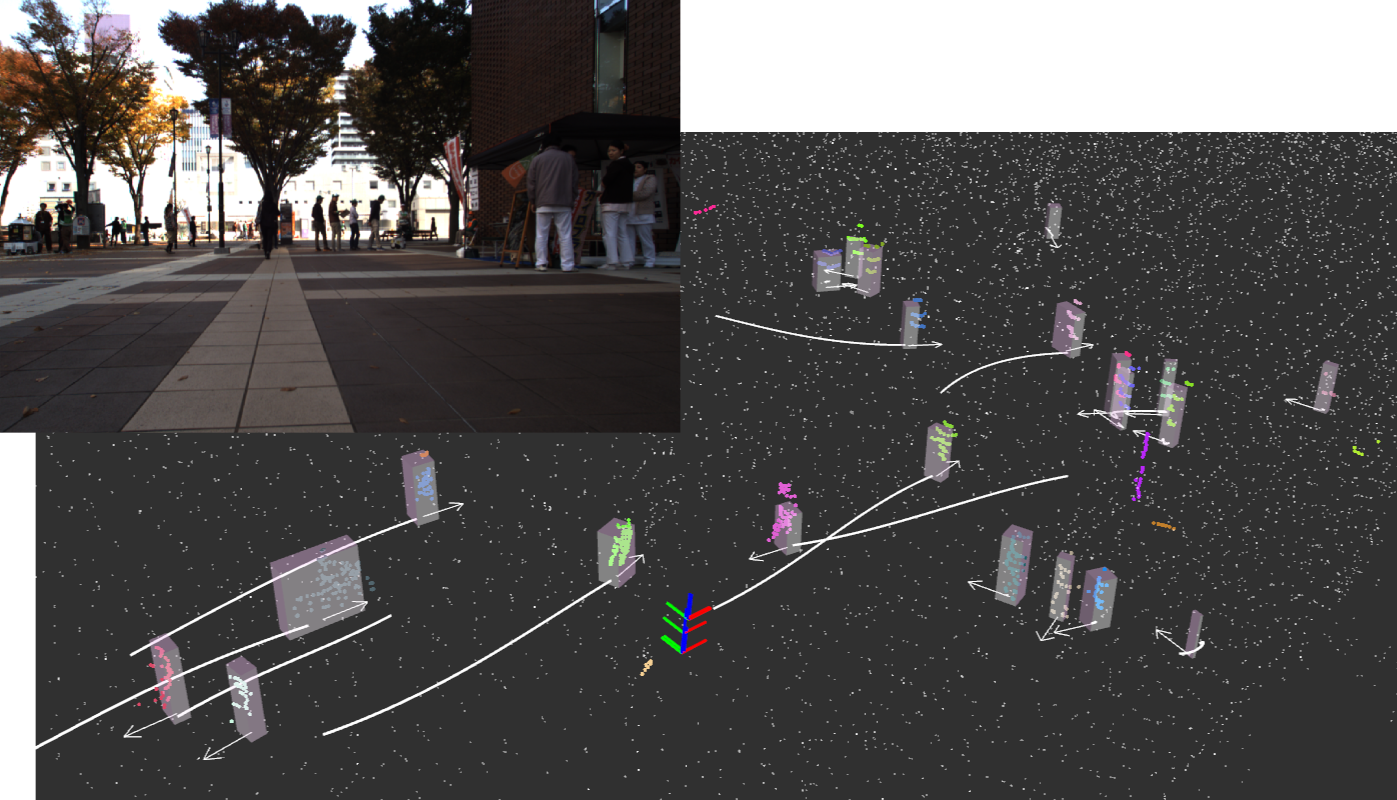

Commonly used object trackers rely on simple data association techniques followed by traditional filtering methods. When objects are tracked in 3D space at high frame rate, nearest neighbor methods are often sufficient for establishing associations between objects. Image-based methods, however, need to establish some appearance model, which may consider the use of color histograms, gradients and other features such as KLT to evaluate the similarity . Point cloud based methods may also use similarity metrics such as point density and Hausdorff distance. Since association errors are always a possibility, multiple hypothesis tracking algorithms are often employed, which ensures tracking algorithms can recover from poor data association at any single time step. Using occupancy maps as a frame for all sensors to contribute to and then doing data association in that frame is common, especially when using multiple sensors. To obtain smooth dynamics, the detection results are filtered by traditional Bayes filters. Kalman filtering is sufficient for simple linear models, while the extended and and unscented Kalman filters are used to handle nonlinear dynamic models. We implemented a basic particle filter based object-tracking algorithm, and an example of tracked pedestrians in contrasting camera and 3D lidar perspective is shown in 5.

Physical models for the object being tracked are also often used for more robust tracking. In that case, non-parametric methods such as particle filters are used, and physical parameters such as the size of the object are tracked alongside dynamics. More involved filtering methods such as Rao-Blackwellized particle filters have also been used to keep track of both dynamic variables and vehicle geometry variables for an L-shape vehicle model. Various models have been proposed for vehicles and pedestrians, while some models generalize to any dynamic object.

Finally, deep learning has also been applied to the problem of tracking, particularly for images. Tracking in monocular images was achieved in real-time through a CNN-based method. Multi-task network which estimate object dynamics are also emerging which further suggests that generalized networks tackling multiple perception tasks may be the future of ADS perception.

Road and Lane Detection

Bounding box estimation methods previously covered are useful for defining some objects of interest but are inadequate for continuous surfaces like roads. Determining the drivable surface is critical for ADSs and has been specifically researched as a subset of the detection problem. While drivable surfaces can be determined through semantic segmentation, automated vehicles need to understand road semantics to properly negotiate the road. An understanding of lanes, and how they are connected through merges and intersections remains a challenge from the perspective of perception. In this section, we provide an overview of current methods used for road and lane detection, and refer the reader to in-depth surveys of traditional methods and the state-of-the-art methods.

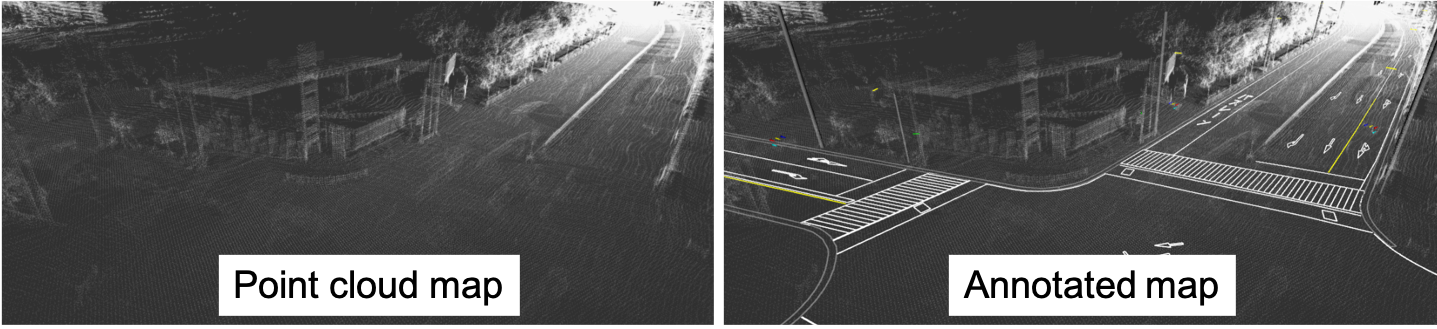

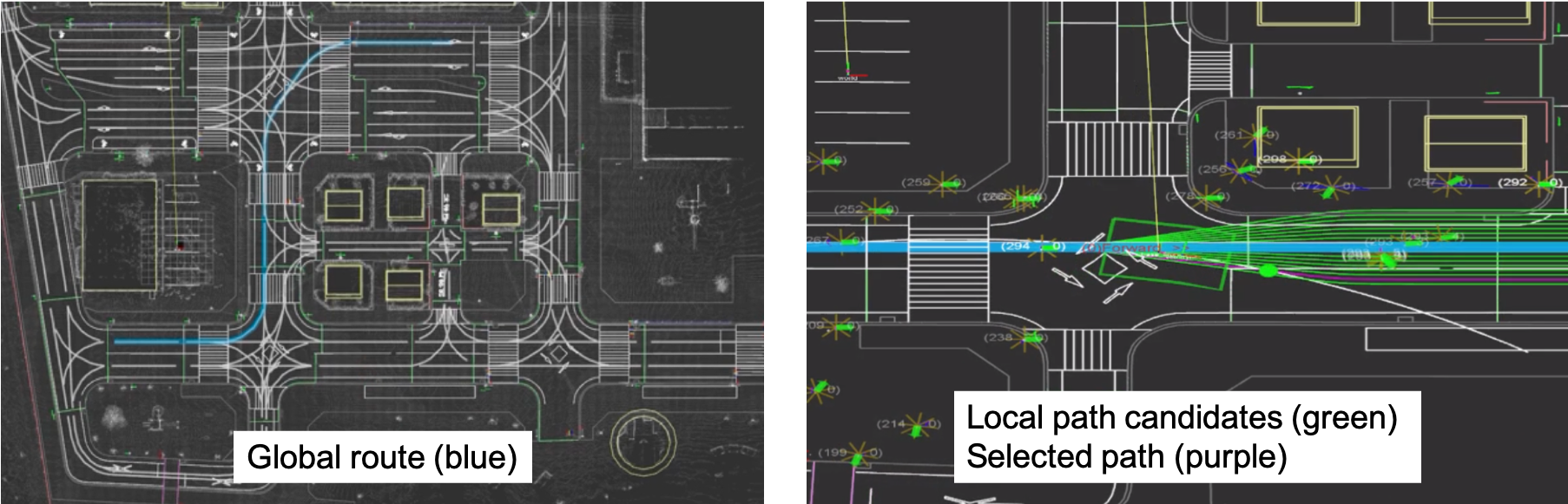

This problem is usually subdivided in several tasks, each unlocking some level of automation. The simplest is determining the drivable area from the perspective of the ego-vehicle. The road can then be divided into lanes, and the vehicles’ host lane can be determined. Host lane estimation over a reasonable distance allows ADAS technology such as lane departure warning, lane keeping and adaptive cruise control . Even more challenging is determining other lanes and their direction , and finally understanding complex semantics, as in their current and future direction, or merging and turning lanes . These ADAS or ADS technologies have different criteria both in terms of task, detection distance and reliability rates, but fully automated driving will require a complete, semantic understanding of road structures and the ability to detect several lanes at long ranges . Annotated maps as shown in 6 are extremely useful for understanding lane semantics.

Current methods on road understanding typically first rely on exteroceptive data preprocessing. When cameras are used, this usually means performing image color corrections to normalize lighting conditions. For lidar, several filtering methods can be used to reduce clutter in the data such as ground extraction or map-based filtering. For any sensing modality, identifying dynamic objects which conflicts with the static road scene is an important pre-processing step. Then, road and lane feature extraction is performed on the corrected data. Color statistics and intensity information, gradient information, and various other filters have been used to detect lane markings. Similar methods have been used for road estimation, where the usual uniformity of roads and elevation gap at the edge allows for region growing methods to be applied. Stereo camera systems, as well as 3D lidars, have been used determine the 3D structure of roads directly. More recently, machine learning-based methods which either fuse maps with vision or use fully appearance-based segmentation have been used.

Once surfaces are estimated, model fitting is used to establish the continuity of the road and lanes. Geometric fitting through parametric models such as lines and splines have been used, as well as non-parametric continuous models. Models that assume parallel lanes have been used, and more recently models integrating topological elements such as lane splitting and merging were proposed.

Temporal integration completes the road and lane segmentation pipeline. Here, vehicle dynamics are used in combination with a road tracking system to achieve smooth results. Dynamic information can also be used alongside Kalman filtering or particle filtering to achieve smoother results.

Road and lane estimation is a well-researched field and many methods have already been integrated successfully for lane keeping assistance systems. However, most methods remain riddled with assumptions and limitations, and truly general systems which can handle complex road topologies have yet to be developed. Through standardized road maps which encode topology and emerging machine learning-based road and lane classification methods, robust systems for driving automation are slowly taking shape.

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)