Efficient Evaluation of Knowledge Graph Accuracy

📝 Original Paper Info

- Title: Efficient Knowledge Graph Accuracy Evaluation- ArXiv ID: 1907.09657

- Date: 2019-07-24

- Authors: Junyang Gao, Xian Li, Yifan Ethan Xu, Bunyamin Sisman, Xin Luna Dong, Jun Yang

📝 Abstract

Estimation of the accuracy of a large-scale knowledge graph (KG) often requires humans to annotate samples from the graph. How to obtain statistically meaningful estimates for accuracy evaluation while keeping human annotation costs low is a problem critical to the development cycle of a KG and its practical applications. Surprisingly, this challenging problem has largely been ignored in prior research. To address the problem, this paper proposes an efficient sampling and evaluation framework, which aims to provide quality accuracy evaluation with strong statistical guarantee while minimizing human efforts. Motivated by the properties of the annotation cost function observed in practice, we propose the use of cluster sampling to reduce the overall cost. We further apply weighted and two-stage sampling as well as stratification for better sampling designs. We also extend our framework to enable efficient incremental evaluation on evolving KG, introducing two solutions based on stratified sampling and a weighted variant of reservoir sampling. Extensive experiments on real-world datasets demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of our proposed solution. Compared to baseline approaches, our best solutions can provide up to 60% cost reduction on static KG evaluation and up to 80% cost reduction on evolving KG evaluation, without loss of evaluation quality.💡 Summary & Analysis

This paper tackles the challenge of efficiently and accurately evaluating large-scale knowledge graphs (KGs). Traditional methods for assessing KG accuracy often require substantial human annotation efforts, which can be prohibitively expensive. The authors propose an efficient sampling and evaluation framework that significantly reduces these costs while maintaining high-quality accuracy evaluations with strong statistical consistency.Core Summary: The paper presents a method to efficiently evaluate the accuracy of large-scale knowledge graphs (KGs) through effective sampling techniques and minimal human annotation efforts, ensuring both quality and efficiency in the evaluation process.

Problem Statement: Knowledge Graphs can contain numerous erroneous facts. Evaluating their accuracy typically requires extensive human annotation, which is time-consuming and costly. Additionally, as KGs evolve over time with new information being added, re-evaluating their accuracy becomes a significant challenge.

Solutions (Core Techniques): The paper introduces an iterative evaluation framework that utilizes cluster sampling, weighted sampling, and stratified sampling to reduce overall annotation costs. By focusing on specific clusters within the KG, the approach minimizes redundant identification efforts for entities and streamlines the evaluation process.

Key Results: Compared to baseline methods, this framework achieves up to 60% cost reduction in static KG evaluations and up to 80% cost reduction in evolving KGs without compromising accuracy or quality of the evaluations. The iterative nature ensures that only necessary samples are evaluated until a satisfactory level of precision is achieved.

Significance and Applications: This research provides a practical solution for maintaining the integrity and reliability of large-scale KGs, enabling more efficient use of human resources in their continuous evaluation and improvement. It supports both static and evolving KG environments, making it valuable for various applications that rely on up-to-date and accurate data.

📄 Full Paper Content (ArXiv Source)

Over the past few years, we have seen an increasing number of large-scale KGs with millions of relational facts in the format of RDF triples (subject,predicate,object). Examples include DBPedia , YAGO , NELL , Knowledge-Vault , etc. However, the KG construction processes are far from perfect, so these KGs may contain many incorrect facts. Knowing the accuracy of the KG is crucial for improving its construction process (e.g., better understanding the ingested data quality and defects in various processing steps), and informing the downstream applications and helping them cope with any uncertainty in data quality. Despite its importance, the problem of efficiently and reliably evaluating KG accuracy has been largely ignored by prior academic research.

KG accuracy can be defined as the percentage of triples in the KG being correct. Here, we consider a triple being correct if the corresponding relationship is consistent with the real-life fact. Typically, we rely on human judgments on the correctness of triples. Manual evaluation at the scale of modern KGs is prohibitively expensive. Therefore, the most common practice is to carry out manual annotations on a (relatively small) sample of KG and compute an estimation of KG accuracy based on the sample. A naive and popular approach is to randomly sample triples from the KG to annotate manually. A small sample set translates to lower manual annotation costs, but it can potentially deviate from the real accuracy. In order to obtain a statistically meaningful estimation, one has to sample a large “enough” number of triples, so increasing cost of annotation. Another practical challenge is that KG evolves over time—as new facts are extracted and added to the KG, its accuracy changes accordingly. Assuming we have already evaluated a previous version of the KG, we would like to incrementally evaluate the accuracy of the new KG without starting from scratch.

| Task1 | Task2 |

|---|---|

| (Michael Jordan, graduatedFrom, UNC) | (Michael Jordan, wasBornIn, LA) |

| (Vanessa Williams, performedIn, Soul Food) | (Michael Jordan, birthDate, February 17, 1963) |

| (Twilight, releaseDate, 2008) | (Michael Jordan, performedIn, Space Jam) |

| (Friends, directedBy, Lewis Gilbert) | (Michael Jordan, graduatedFrom, UNC) |

| (The Walking Dead, duration, 1h 6min) | (Michael Jordan, hasChild, Marcus Jordan) |

To motivate our solution, let us examine in some detail how the manual annotation process works. We use two annotation tasks shown in Table [fig:motivating-example] as examples.

Mentions of real-life entities can be ambiguous. For example, the first triple in Task1, the name “Michael Jordan” could refer to different people — Michael Jordan the hall-of-fame basketball player or Michael Jordan the distinguished computer scientist? The former was born in New York, while the latter was born in Los Angeles. Before we verify the relationship between subject and object, the first task is to identify each entity.1 If we assess a new triple on an entity that we have already identified, the total evaluation cost will be lower compared to assessing a new triple from unseen entities. For example, in Task2, all triples are about the same entity of Michael Jordan. Once we identify this Michael Jordan as the basketball player, annotators could easily evaluate correctness of these triples without further identifications on the subject. On the contrary, in Task1, five different triples are about five different entities. Each triple’s annotation process is independent, and annotators need to spend extra efforts first identifying possible ambiguous entities for each of them, i.e., Friends the TV series or Friends the movie? Twilight the movie in 2008 or Twilight the movie in 1998? Apparently, given the same number of triples for annotations, Task2 takes less time. In addition, validating triples regarding the same entity would also be an easier task. For example, a WiKi page about an actor/actress contains most of the person’s information or an IMDb page about a movie lists its comprehensive features. Annotators could verify a group of triples regarding the same entity all at once in a single (or limited number) source(s) instead of searching and navigating among multiple sources just to verify an individual fact.

Hence, generally speaking, auditing on triples about the same entity (as Task2) can be of lower cost than on triples about different entities (as Task1). Unfortunately, given the million- or even billion-scale of the KG size, selecting individual triples is more likely to produce an evaluation task as Task1.

As motivated in the above example, when designing a sampling scheme for large KG, the number of sampled triples is no longer a good indicator of the annotation cost—instead, we should be mindful of the actual properties of the manual annotation cost function in our sampling design. Our contributions are four-fold:

-

We provide an iterative evaluation framework that is guaranteed to provide high-quality accuracy estimation with strong statistical consistency. Users can specify an error bound on the estimation result, and our framework iteratively samples and estimates. It stops as soon as the error of estimation is lower than user required threshold without oversampling and unnecessary manual evaluations.

-

Exploiting the properties of the annotation cost, we propose to apply cluster sampling with unequal probability theory that enables efficient manual evaluations. We quantitatively derive the optimal sampling unit size in KGs by associating it with approximate evaluation cost.

-

The proposed evaluation framework and sampling technique can be extended to enable incremental evaluation over evolving KGs. We introduce two efficient incremental evaluation solutions based on stratified sampling and a weighted variant of reservoir sampling respectively. They both enable us to reuse evaluation results from previous evaluation processes, thus significantly improving the evaluation efficiency.

-

Extensive experiments on various real-life KGs, involving both ground-truth labels and synthetic labels, demonstrate the efficiency of our solution over existing baselines. For evaluation tasks on static KG, our best solution cuts the annotation cost up to 60%. For evaluation tasks on evolving KG, incremental evaluation based on stratified sampling provides up to 80% cost reduction.

To the best of our knowledge, this work is among the first to propose a practical evaluation framework that provides efficient, unbiased, and high-quality KG accuracy estimation for both static and evolving KGs.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 16 reviews the key concepts of KG accuracy evaluation and formally defines the problem. Section 9 proposes an evaluation model and analyzes human annotator’s performances over different evaluation tasks that motivate our solution. Section 13 experimentally evaluates our solutions. Finally, we review related work on KG accuracy evaluation in Section 14 and conclude in Section 15.

Related Work

As discussed earlier, SRS is a simple but prevalent method for KG accuracy evaluation. Beyond SRS, Ojha et al. were the first to systematically tackle the problem of efficient accuracy evaluation of large-scale KGs. One key observation is that, by exploring dependencies (i.e., type consistency, Horn-clause coupling constraints and positive/negative rules ) among triples in KG, one can propagate the correctness of evaluated triples to other non-evaluated triples. The main idea of their solution is to select a set of triples such that knowing the correctness of these triples could infer correctness for the largest part of KG. Then, KG accuracy is estimated using all labelled triples. Their inference mechanism based on Probabilistic Soft Logic could significantly save manual efforts on evaluating triples’ correctness. However, there are some issues in applying their approach to our setting. First, the inference process is probabilistic and might lead to erroneous propagations of true/false labels. Therefore, it is difficult to assess the bias introduced by this process into the accuracy estimation. Second, KGEval relies on expensive2 (machine time) inference mechanism, which does not scale well on large-scale KGs. Finally, they do not address accuracy evaluation for evolving KGs. We summarize the comparison between these existing approaches in Table 1.

Accuracy evaluation on KGs is also closely related to error detection and fact validation on KGs or “Linked Data” . Related work includes numerical error detection , error detection through crowdsourcing , matchings among multiple KGs , fact validation through web-search , etc. However, previous work mentioned above all have their own limitations, and have so far not been exploited for efficient KG accuracy evaluation.

Another line of related work lies in data cleaning , where sampling-based methods with groundings in statistical theory are used to improve efficiency. In , the authors designed a novel sequential sampler and a corresponding estimator to provide efficient evaluations (F-measure, precision and recall) on the task of entity resolution . The sampling framework sequentially draws samples (and asks for labelling) from a biased instrumental distribution and updates the distribution on-the-fly as more samples are collected, in order to quickly focus on unlabelled items providing more information. Wang et al. considered combining sampling-based approximate query processing with data cleaning, and proposed a sample-and-clean framework to enable fast aggregate queries on dirty data. Their solution takes the best of both worlds and provides accurate query answers with fast query time. However, the work mentioned above did not take advantage of the properties of the annotation cost function that arise in practice in our setting—they focused on reducing the number of records to be labelled or cleaned by human workers, but ignored opportunities of using clustering to improve efficiency.

| SRS | KGEval | Ours | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unbiased Evaluation | |||

| Efficient Evaluation | |||

| on Evolving KG |

Summary of existing work on KG accuracy evaluation.

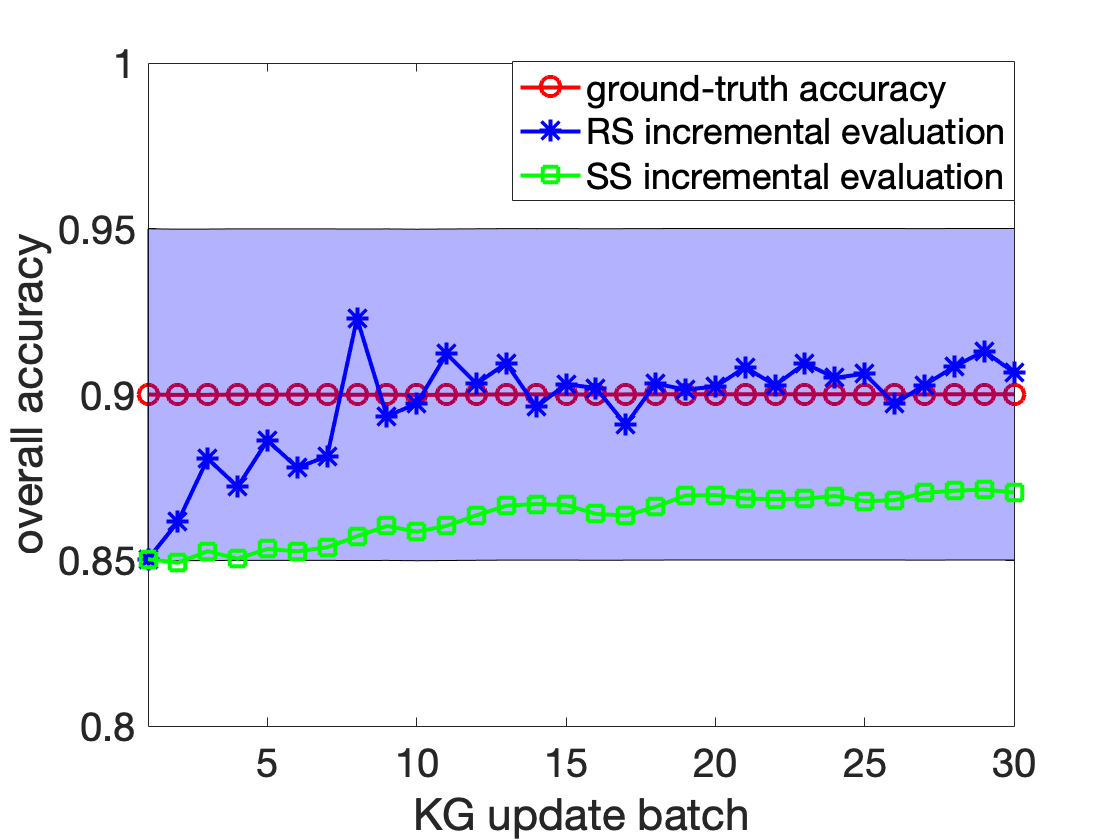

Evaluation on Evolving KG

We discuss two methods to reduce the annotation cost in estimating $`\acc(G+\Delta)`$ as a KG evolves from $`G`$ to $`G+\Delta`$, one based on reservoir sampling and the other based on stratified sampling.

Reservoir Incremental Evaluation

Reservoir Incremental Evaluation (RS) is based on the reservoir sampling scheme, which stochastically updates samples in a fixed size reservoir as the population grows. To apply reservoir sampling on evolving KG to obtain a sample for TWCS, We introduce the reservoir incremental evalution procedure as follows.

For any batch of insertions $`\Delta_e \in \Delta`$ to an entity $`e`$, we treat $`\Delta_e`$ as a new and independent cluster, despite the fact that $`e`$ may already exist in the KG. This is to ensure weights of clusters stay constant. Though we may break an entity cluster into several disjoint sub-clusters over time, it does not change the properties of weighted reservoir sampling or TWCS, since these sampling techniques work independently on the definition of clusters.

The Reservoir Incremental Evaluation procedure based on TWCS reservoir sampling is described in Algorithm [algo:reservoir].

$`G \leftarrow G \cup \Delta_e`$;

Find the smallest reservoir key value in $`K`$ as $`k_j`$;

Compute update key value $`k_e=[\mathrm{Rand}(0, 1)]^{1/|\Delta_e|}`$ ;

$`R`$

Two properties of RS make it preferable for dynamic evaluation on evolving KGs. First, as $`G`$ evolves, RS allows an efficient one-pass scan over the insertion sequence to generate samples. Secondly, compared to re-sampling over $`G+\Delta`$, RS retains a large portion of annotated triples in the new sample, thus significantly reduces annotation costs.

After incremental sample update using Algorithm [algo:reservoir], it happens that the MoE of estimation becomes larger than the required threshold $`\epsilon`$. In this case, we again run Static Evaluation process on $`G+\Delta`$ to draw more batches of cluster samples from the the current state of KG iteratively until MoE is no more than $`\epsilon`$.

Cost Analysis

As KG evolves from $`G`$ to $`G + \Delta`$, Algorithm [algo:reservoir] incrementally updates the random sample $`G'`$ to $`(G+\Delta)'`$, which avoids a fresh round of manual annotation. Our estimation process only needs an incremental evaluation on these (potentially small) newly sampled entities/triples. Also in , the authors pointed out that the expected number of insertions into the reservoir (without the initial insertions into an empty reservoir) is

\begin{align}

\begin{split}

\text{\# of insertions} &= \sum_{i=N_i}^{N_j} \Pr[\text{cluster $i$ is inserted into reservoir}] \\

&= O\bigg(\card{R} \cdot \log{\bigg(\frac{N_j}{N_i}}\bigg)\bigg),

\end{split}

\end{align}where $`\card{R}`$ is the size of reservoir, and $`N_i,N_j`$ is the total number of clusters in $`G, G+\Delta`$, respectively.

The incremental evaluations

on new samples incurred by weighted sample update on evolving KG is at

most

$`O\bigg(\card{R} \cdot \log{\big(\frac{N_j}{N_i}}\big)\bigg)`$, where

$`R`$ is the origin sample pool, and $`N_i, N_j`$ is the total number of

clusters in the origin KG and the evolved KG, respectively.

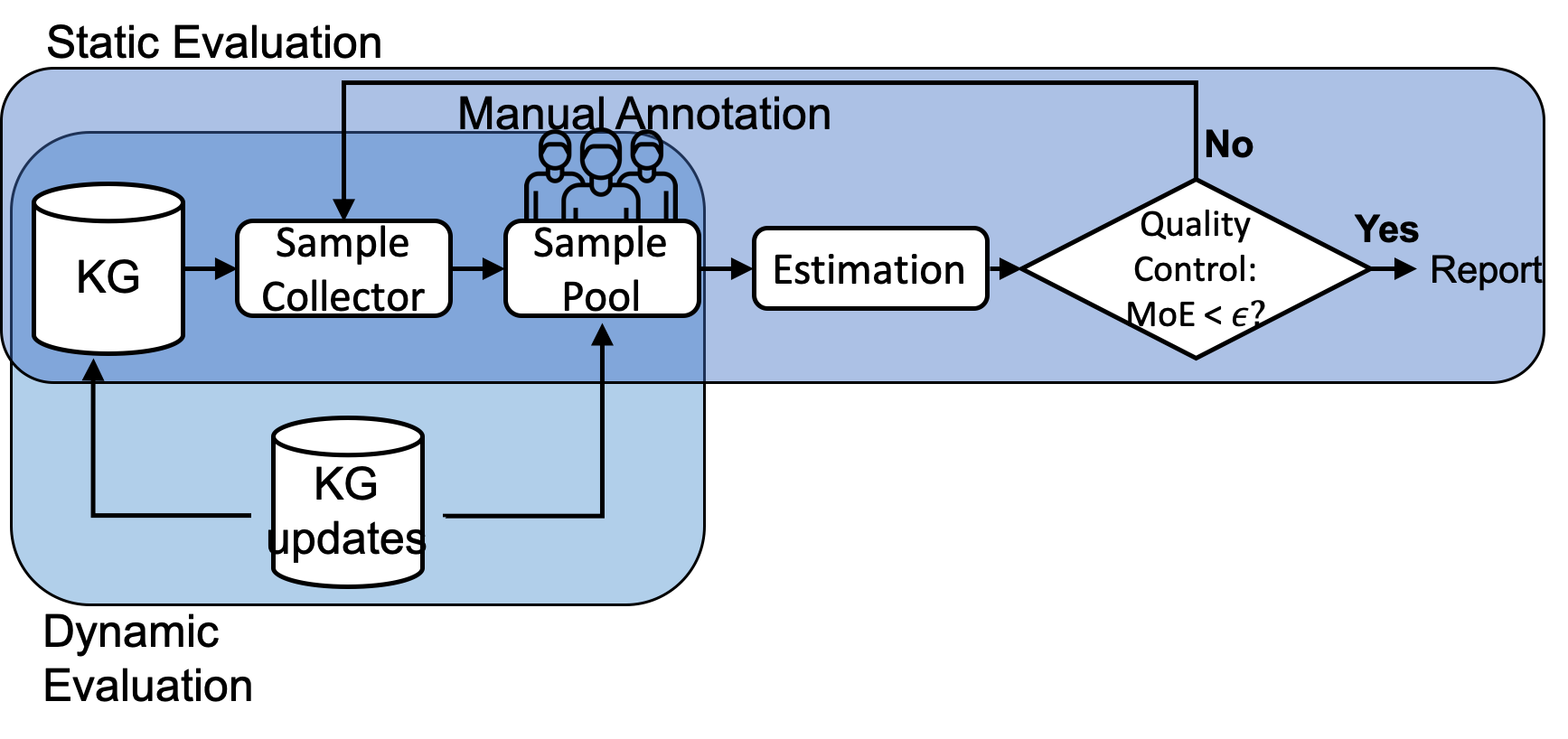

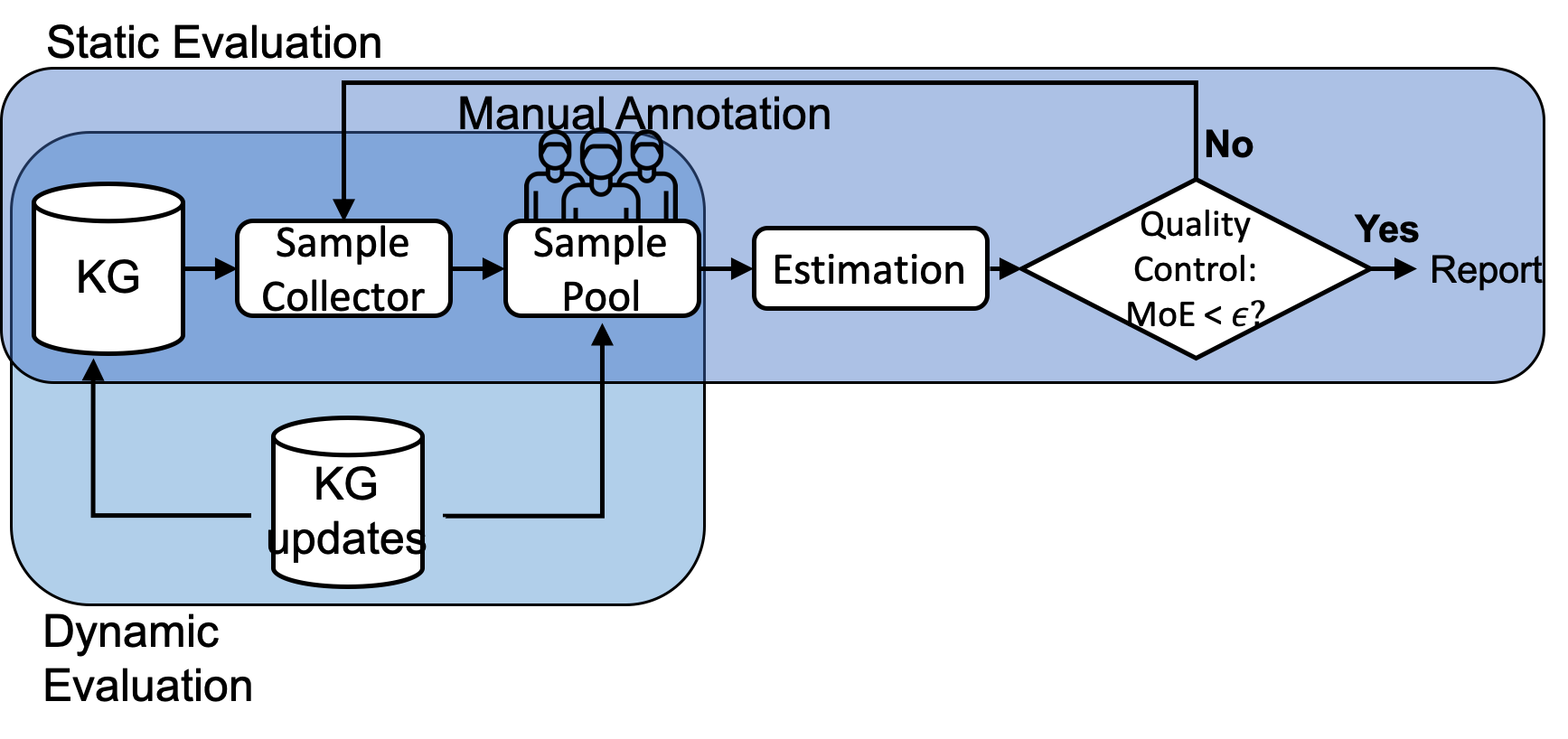

Evaluation Framework

In a nutshell, our evaluation framework is shown in Fig 1. There are two evaluation procedures.

Static Evaluation conducts efficient and high-quality accuracy evaluation on static KGs. It works as the following iterative procedure, sharing the same spirit as in Online Aggregation :

-

Step 1: Sample Collector selects a small batch of samples from KG using a specific sampling design $`\mathcal{D}`$. Section 17 discusses and compares various sampling designs.

-

Step 2: Sample Pool contains all samples drawn so far and asks for manual annotations when new samples are available.

-

Step 3: Given accumulated human annotations and the sampling design $`\mathcal{D}`$, the Estimation component computes an unbiased estimation of KG accuracy and its associated MoE.

-

Step 4: Quality Control checks whether the evaluation result satisfies the user required confidence interval and MoE. If yes, stop and report; otherwise, loop back to Step 1.

Dynamic Evaluation enables efficient incremental evaluation on evolving KGs. We propose two evaluation procedures. One is based on reservoir sampling, and the other is based on stratified sampling. Section 12 introduces the detailed implementations.

The proposed framework has the following advantages. (1) The framework selects and estimates iteratively through a sequence of small batches of samples from KG, and stops as soon as the estimation quality satisfies the threshold (specified by MoE) as user required. It avoids oversampling and unnecessary manual annotations and always reports an accuracy evaluation with strong statistical guarantee. (2) The framework works efficiently both on static KGs and evolving KGs with append-only changes.

Experiments

In this section, we comprehensively and quantitatively evaluate the performance of all proposed methods. Section 13.1 elaborates the experiment setup. Section 13.2 focuses on the accuracy evaluation on static KGs. We compare the evaluation efficiency and estimation quality of various methods on different static KGs with different data characteristics. Section 13.3 evaluates the performance of the proposed incremental evaluation methods on evolving KGs. We simulate several typical scenarios of evolving KG evaluations in practice, and demonstrate the efficiency and effectiveness of our proposed incremental evaluation solutions.

Experiment Setup

| NELL | YAGO | MOVIE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 817 | 822 | 288,770 | ||

| 1,860 | 1,386 | 2,653,870 | ||

| 2.3 | 1.7 | 9.2 | ||

| Gold Accuracy | 91% | 99% | 90% (MoE: 5%) |

Data characteristics of various KGs.

Dataset Description

NELL & YAGO are small sample sets drawn from the original knowledge graph NELL-Sports and YAGO2 , respectively. Ojha and Talukdar collected manual annotated labels (true/false), evaluated by recognized workers on Amazon Mechanical Turk, for each fact in NELL and YAGO. We use these labels as gold standard. The ground-truth accuracies of NELL and YAGO are 91% and 99%, respectively.

MOVIE, based on IMDb3 and WiKiData , is a knowledge base It contains more than 2 million factual triples. To estimate the overall accuracy of MOVIE, we randomly sampled and manually evaluated 174 triples. The unbiased estimated accuracy is 88% within a 5% margin of error at the 95% confidence level.

Synthetic Label Generation

Collecting human annotated labels is expensive. We generate a set of synthetic labels for MOVIE in order to perform in-depth comparison of different methods. MOVIE-SYN refers to a set of synthetic KGs with different label distributions. We introduce two synthetic label generation models as follows.

Random Error Model

The probability that a triple in the KG is correct is a fixed error rate $`r_{\epsilon} \in [0,1]`$. This random error model (REM) is simple, but only has limited control over different error distributions and can not properly simulate real-life KG situations.

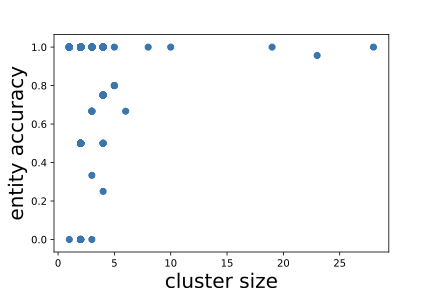

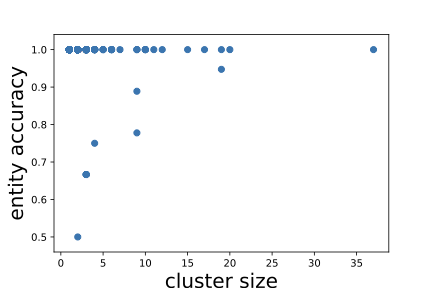

Binomial Mixture Model

Recall in Figure [fig:correlation], we find that larger entities in the KG are more likely to have higher entity accuracy. Based on this observation, we synthetically generate labels that better approximate such distribution of triple correctness. First, we assume that the number of correct triples from the $`i`$-th entity cluster follows a binomial distribution parameterized by the entity cluster size $`M_i`$ and a probability $`\hat{p}_i \in [0,1]`$; that is, $`f(t) \sim \mathrm{B}(M_i, \hat{p}_i)`$. Then, to simulate real-life situations, we assume a relationship between $`M_i`$ and $`\hat{p}_i`$ specified by the following sigmoid-like function:

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:synthetic}

\hat{p}_i =

\begin{cases}

0.5 + \epsilon, & \text{if}~M_i < k \\

\frac{1}{1 + e^{-c(M_i - k)}} + \epsilon, & \text{if}~M_i \ge k

\end{cases}

\end{equation}where $`\epsilon`$ is a small error term from a normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation $`\sigma`$, and $`c\ge 0`$ scales the influence of cluster size on entity accuracy. $`\epsilon`$ and $`c`$ together control the correlation between $`M_i`$ and $`\hat{p}_i`$.

Tuning $`c, \epsilon`$ and $`k`$, the Binomial Mixture Model (BMM) allows us to experiment with different data characteristics without the burden of repeating manual annotations. For our experiment, we use $`k=3`$ by default, and vary $`c`$ from 0.00001 to 0.5 and $`\sigma`$ (in $`\epsilon`$) from 0.1 to 1 for various experiment setting; A larger $`\sigma`$ and a smaller $`c`$ lead to a weaker correlation between the size of a cluster and its accuracy. By default, $`c=0.01`$ and $`\sigma=0.1`$.

Cost Function

| SRS | TWCS ($`m=10`$) | |

|---|---|---|

| Annotation task | ||

| / 174 triples | ||

| / 178 triples | ||

| Annotation time | 3.53 | 1.4 |

| Estimation | 88% (MoE: 4.85%) | 90% (MoE: 4.97%) |

Manual evaluation cost (in hours) on MOVIE.

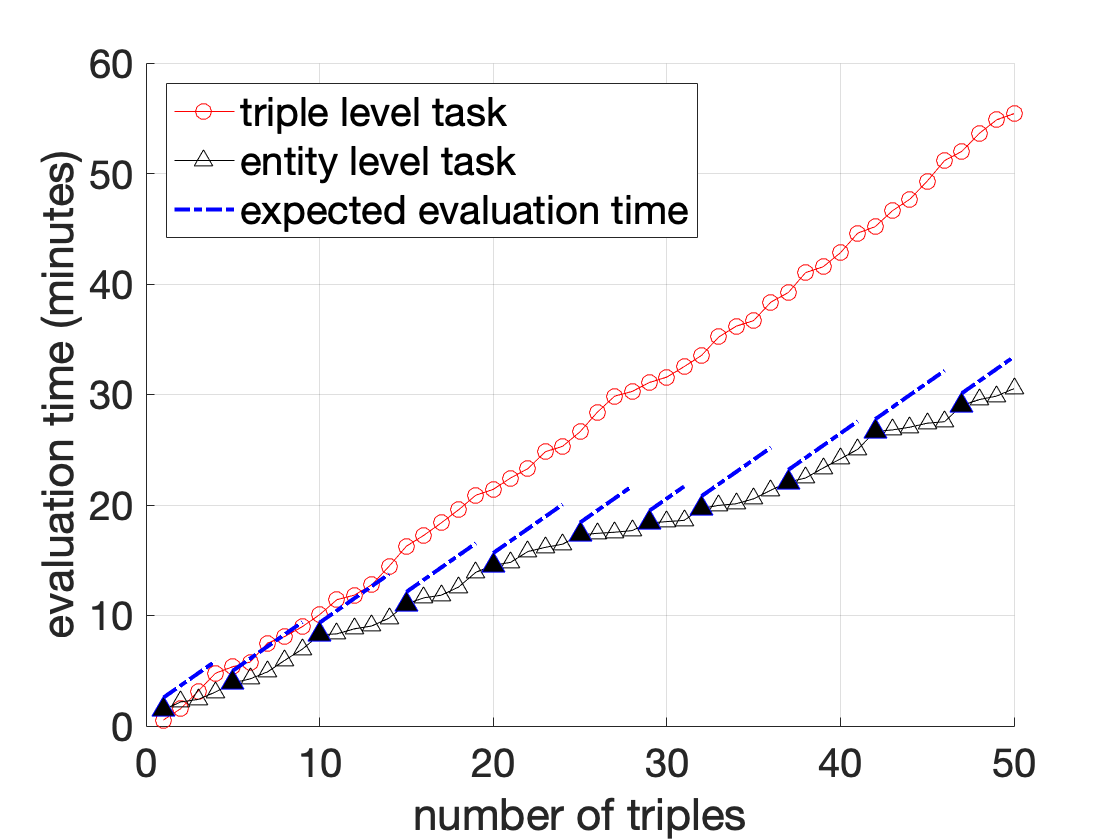

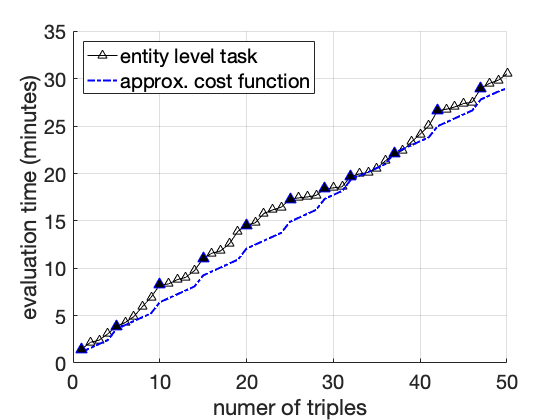

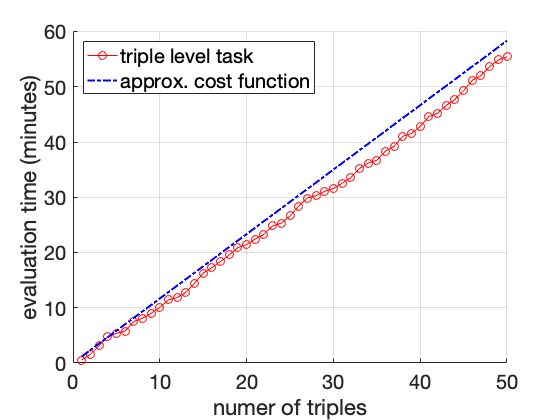

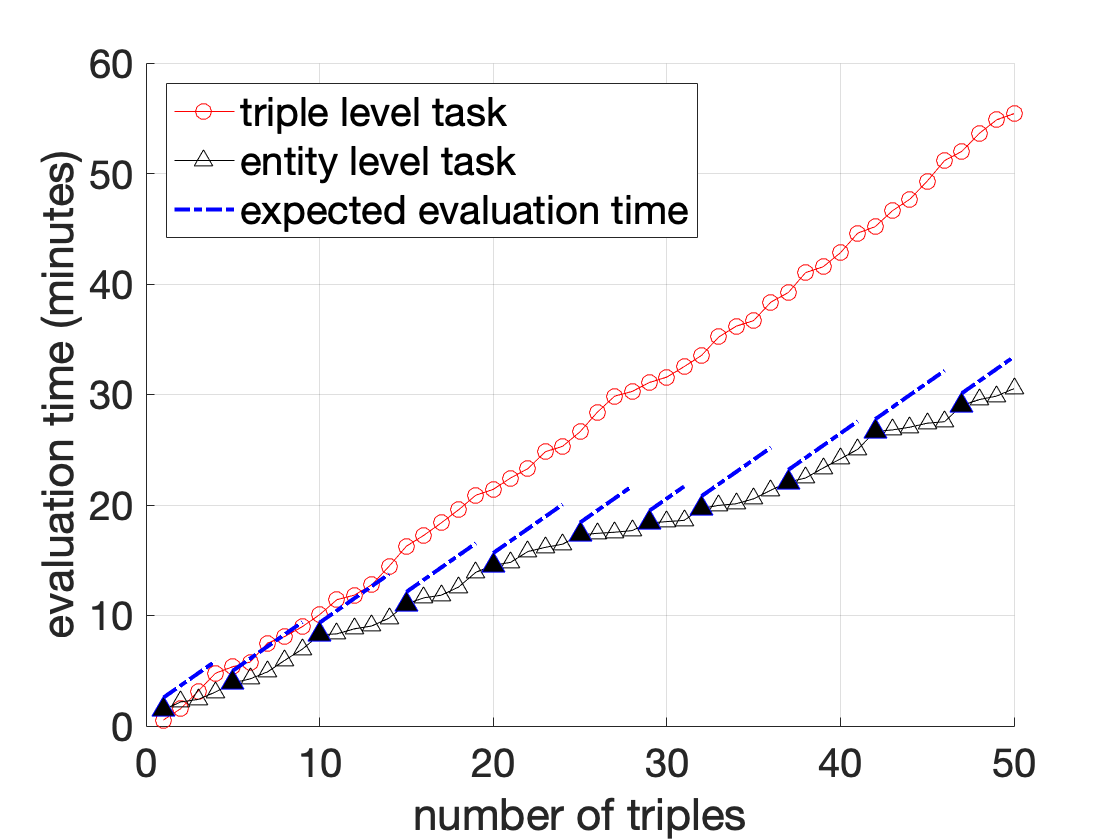

Recall in Section 9, we introduce an annotation model to simulate the actual manual annotation process on triple correctness, and a corresponding cost function as Eq ([eq:simplified-cost]). We asked human annotators to do manual annotations on small portion of MOVIE selected by our proposed evaluation framework, and measured their total time usage. Results are summarized in Table 3. Then, we fit our cost function given all the data points reported in Table 3 and Figure 8, and compute the best parameter settings as $`c_1 = 45`$(second) and $`c_2 = 25`$(second). As shown in Figure 2, our fitted cost function can closely approximate the actual annotation time under different types of annotation tasks. Also, for annotation tasks in Table 3, the approximate cost is $`174\times(45+25)/3600 \approx 3.86`$ (hours) and $`(24\times45 + 178\times25)/3600 \approx 1.54`$ (hours), respectively, which is close to the ground-truth time usage.

Together with the synthetic label generation introduced in Section 13.1.2, we can effortlessly experiment and compare various sampling and evaluation methods on KGs with different data characteristics, both in terms of the evaluation quality (compared to synthetic gold standards) and efficiency (based on cost function that approximates the actual manual annotation cost). The annotation time reported in Table 3 and Table [tab:overall-cost] on MOVIE is the actual evaluation time usage as we measured human annotators’ performance. All other evaluation time reported in later tables or figures are approximated by the Eq ([eq:simplified-cost]) according to the samples we draw.

Implementations

For evaluation on static KGs, we implement the Sample Collector component in our framework with SRS (Section 17.1), RCS (Section 17.2.1), WCS (Section 17.2.2) and TWCS (Section 17.2.3). TWCS is further parameterized by the second-stage sample unit size $`m`$. If $`m`$ is not specified, we run TWCS with the optimal choice of $`m`$. We also implement TWCS with two stratification strategies (Section 17.3). Size Stratification method first stratifies the clusters by their size using the Cumulative Square root of Frequency (Cumulative $`\sqrt{F}`$) , and then applies the iterative stratified TWCS as introduced in Section 17.3. Since we have the ground-truth labels for YAGO, NELL and MOVIE-SYN, Oracle Stratification method directly stratifies the clusters by their entity accuracy, which is the perfect stratification but not possible in practice though. The evaluation time reported by oracle stratification can be seen as the lower bound of cost, showing the potential improvement of TWCS with stratification.

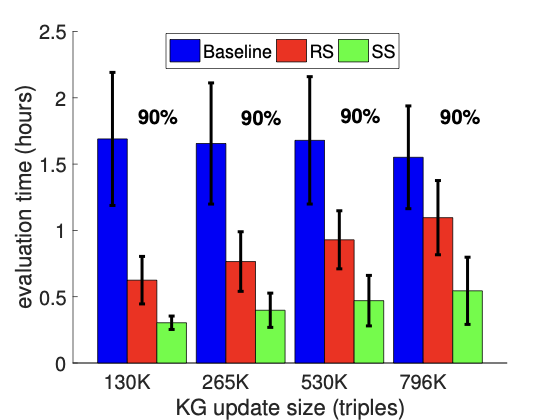

For evaluation on evolving KGs, since there are no well established baseline solutions, we consider a simple Baseline of independently applying TWCS on each snapshot of evolving KGs. Besides that, we implement RS, incremental evaluation based on Reservoir Sampling (Section 12.1), and

All methods were implemented in Python3, and all experiments were performed on a Linux machine with two Intel Xeon E5-2640 v4 2.4GHz processor with 256GB of memory.

Performance Evaluation Metric

Performance of various methods are evaluated using the following two metrics: sample size (number of triples/entities in the sample) and manual annotation time. By default, all evaluation tasks (on static KGs and evolving KGs) are configured as MoE less than 5% with 95% confidence level ($`\alpha=5\%`$). Considering the uncertainty of sampling approaches, we repeat each method 1000 times and report the average sample size/evaluation time usage with standard deviation.

|c|c|c|c|c|c|c| & & &

& & & & & &

SRS & 3.53 & & 2.3$`\pm`$0.45 & &0.45$`\pm`$0.17 &

RCS & $`>5`$ & & 8.25$`\pm`$2.55 & & 10$`\pm`$0.56 &

WCS & $`>5`$ & & 1.92$`\pm`$0.62 & & 0.49$`\pm`$0.04 &

TWCS & 1.4 & & 1.85$`\pm`$0.6 & & 0.44$`\pm`$0.07 &

Actual manual evaluation cost; other costs are estimated using Eq([eq:simplified-cost]) and averaged over 1000 random runs.

For economic considerations, we stop manual annotation process at 5 hours for RCS and WCS. Note that estimations in these two cases (95% and 93%) do not satisfy the 5% MoE with 95% confidence level.

|c|c|c|c|c| & &

& & & &

& & & &

& & $`<`$1 second & & $`<`$1 second

& 140 & $`149\pm 47`$ & 204 & 32$`\pm`$5

& 2.3 & 1.85$`\pm`$0.6 & 3.17 & 0.44$`\pm`$0.07

& & & &

For the highly accurate KG YAGO, we report empirical confidence interval instead of mean and standard deviation. Since accuracy is always capped at 100%, empirical confidence interval can better represent the data distribution in this case.

Evaluation on Static KG

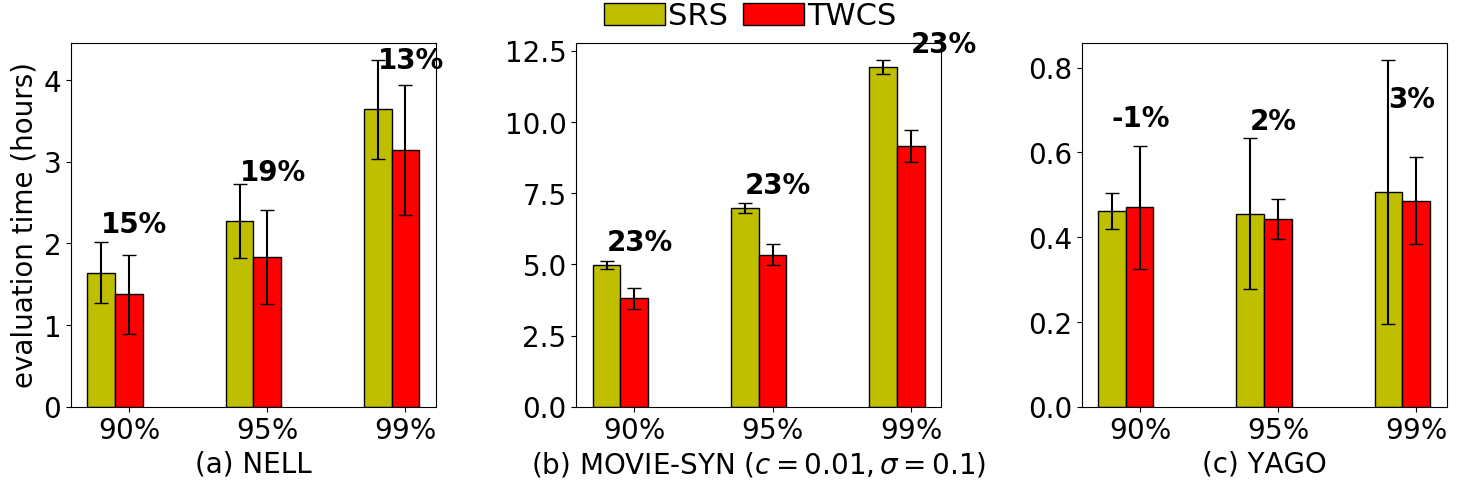

In this section, we compare five methods for evaluation on static KGs: SRS, RCS, WCS, TWCS and KGEval .

Evaluation Efficiency

TWCS vs. All

We start with an overview of performance comparison of various solutions on evaluation tasks on Static KGs. Results are summarized in Table [tab:overall-cost]. Best results in evaluation efficiency are colored in blue. We highlight the following observations. First, TWCS achieves the lowest evaluation cost across different KGs, speeding the evaluation process up to 60% (on MOVIE with actual human evaluation cost), without evaluation quality loss. TWCS combines the benefits of weighted cluster sampling and multi-stage sampling. It lowers entity identification costs by sampling triples in entity groups and applies the second-stage sampling to cap the per-cluster annotation cost. As expected, TWCS is the best choice for efficient KG accuracy evaluation overall.

TWCS vs. SRS

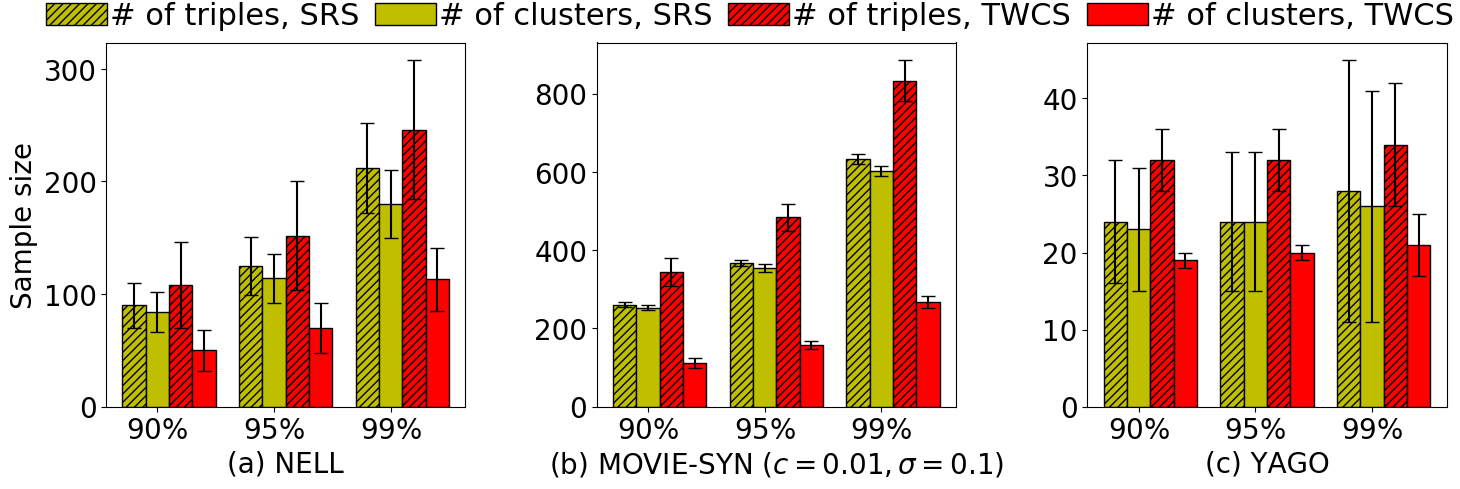

Since SRS is the only solution that has comparable performance to TWCS, we dive deeper into the comparison of SRS and TWCS. Figure 3 shows the comparison in terms of sample size and annotation cost on all three KGs with various evaluation tasks. We summarize the important observations as follows. First, in Figure 3-1, TWCS draws fewer entity clusters than SRS does, even though the number of triples annotated in total by TWCS is slightly higher than that of SRS. Considering that the dominant factor in annotation process is of entity identification, TWCS still saves a fair amount of annotation time. Second, Figure 3-2 quantifies the cost reduction ratio (shown on top of the bars) provided by TWCS. Simulation results suggest that TWCS outperforms SRS by a margin up to 20% on various evaluation tasks with different confidence level on estimation quality and across different KGs. Even on the highly accurate YAGO, TWCS still can save 3% of the time compare to SRS when the estimation confidence level is 99%.

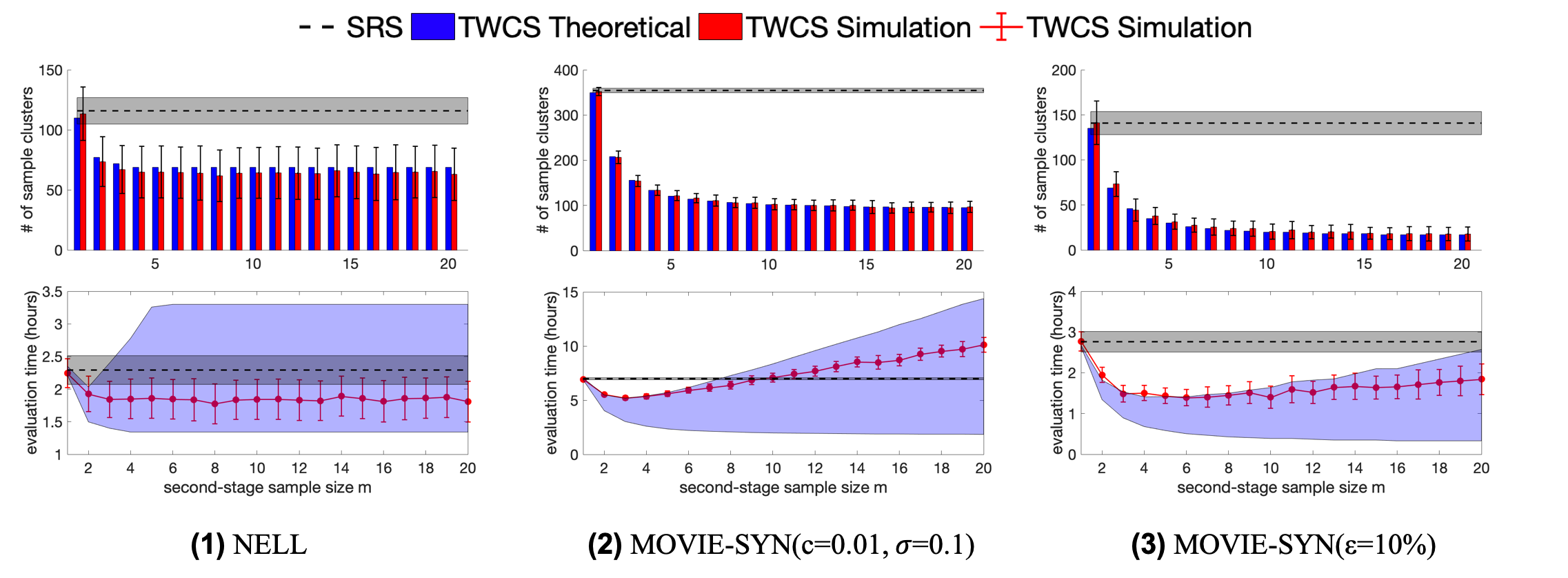

Optimal Sampling Unit Size of TWCS

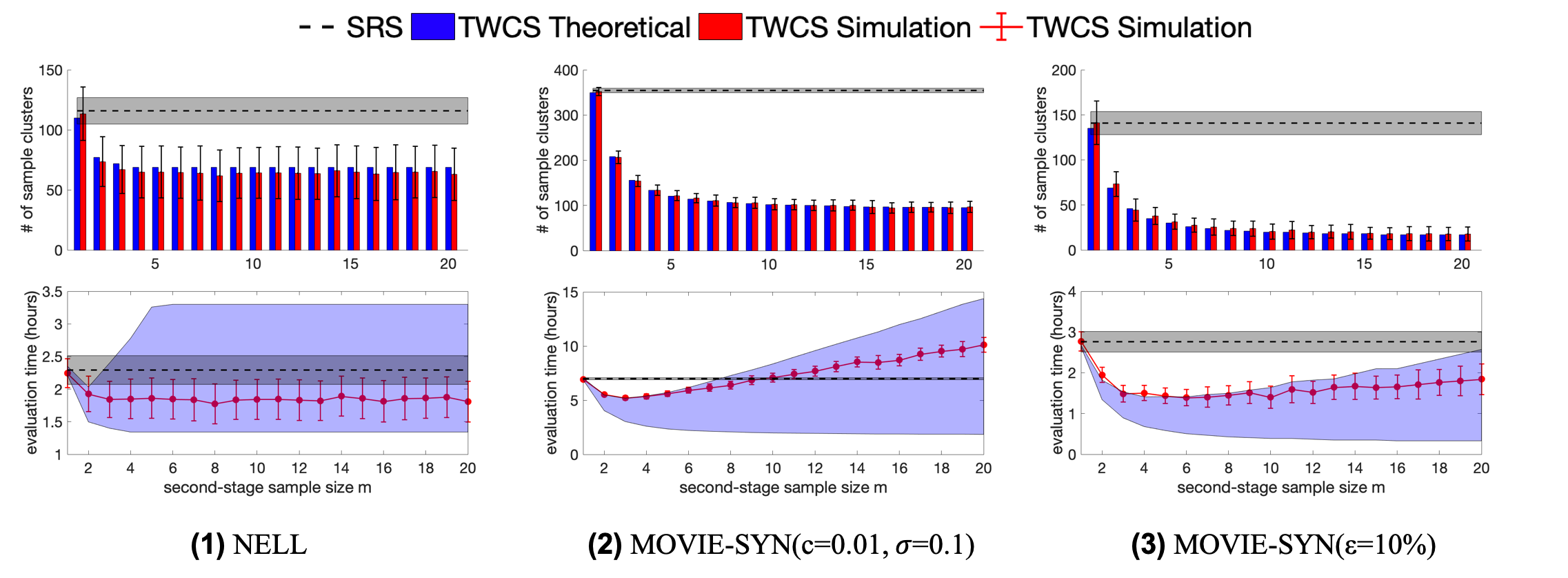

So far, we run experiments using TWCS with the best choice of second-stage sample size $`m`$. In this section, we discuss the optimal value of $`m`$ for TWCS and provide some guidelines on how to choose the (near-) optimal $`m`$ in practice. We present the performance of TWCS on NELL and two instances of MOVIE-SYN as the second-stage sampling size $`m`$ varies from 1 to 20 in Figure 4, using SRS as a reference. For each setting, numbers are reported averaging over 1K random runs.

For sample size comparison: First, when $`m=1`$, TWCS is equivalent to SRS (recall Proposition [lemma:wcs-to-srs]), so the sample size (and evaluation time) reported by TWCS is very close to SRS. Second, as $`m`$ increases, the sample cluster size would first drop significantly and then quickly hit the plateau, showing that a large value of $`m`$ does not help to further decrease the number of sample clusters.

Again, when $`m=1`$, the evaluation cost of SRS and TWCS are roughly the same. Then, on two instances of MOVIE-SYN (Figure 4-2 and Figure 4-3), the annotation time decreases as $`m`$ increases from 1 to around 5 and then starts to go up, which could be even higher than SRS when $`m\geq10`$ (see Figure 4-2). A larger value of $`m`$ potentially leads to more triples to be annotated, as it can not further reduce the number of sample clusters but we are expected to choose more triples from each selected cluster. On NELL, things are little different: the annotation time drops as $`m`$ increases from 1 to around 5 but then roughly stays the same. That is because NELL has a very skewed long-tail distribution on cluster size - more than 98% of the clusters have size smaller than 5. Hence, when $`m`$ becomes larger than 5 and no matter how large the $`m`$ will be, the total number of triples we evaluated is roughly a constant and it is not affected by $`m`$ anymore.

In sum, there is an obvious trade-off between $`m`$ and evaluation cost, as observed in all plots Figure 4. The optimal choices on $`m`$ across KGs (with different data characteristics and accuracy distributions) seems all fall into a narrow range between 3 to 5. However, entity accuracy distributions influence the relative performance of TWCS compared to SRS. For instance, on MOVIE-SYN with $`\epsilon=10\%`$, the synthetic label generations make the cluster accuracy among entities more similar (less variance among accuracy of entity clusters), so we can see TWCS beats SRS by a wide margin up to 50%. In contrast, for other label distributions, the cost reductions provided by TWCS are less than 50%. Considering all results shown in Figure 4, TWCS, by carefully choosing the second-stage sample size $`m`$, always outperforms SRS.

To conclude this section, the optimal choice of $`m`$ and the performance of TWCS depend both on cluster size distribution and cluster accuracy distribution of the KG. In practice, we do not have all such information beforehand. However, as a practical guideline, we suggest that $`m`$ should not be too large. We find a small range of $`m`$ from roughly 3-5 to give the (near-) minimum evaluation cost of TWCS for all KGs considered in our experiments.

TWCS with Stratification

|c|c|c|c|c|c|c| & & &

& & & & & &

SRS & 2.3$`\pm`$0.45 & & 6.99$`\pm`$0.1 & & 3.53 &

TWCS & 1.85$`\pm`$0.6 & & 5.25$`\pm`$0.46 & & 1.4 &

TWCS w/ Size Stratification & 1.90$`\pm`$0.53 & &

3.97$`\pm`$0.5 & & 1.3 &

TWCS w/ Oracle Stratification & 1.04$`\pm`$0.06 & &

2.87$`\pm`$0.3 & & &

Actual manual evaluation cost; other evaluation costs are estimated using Eq([eq:simplified-cost]) and averaged over 1000 random runs.

Since we do not collect manually evaluated labels for all triples in MOVIE, oracle stratification is not applicable here.

Previous sections already demonstrate the efficiency of TWCS. Now, we further show that our evaluation framework could achieve even lower cost with proper stratification over entity clusters in KG. Recall that size stratification partitions clusters by the size while oracle stratification stratifies clusters using the entity accuracy. Table [tab:stratified-sampling] lists and compares the evaluation cost of different methods on NELL, MOVIE-SYN ( $`c=0.01,\sigma=0.1`$) and MOVIE.

On MOVIE-SYN, we observe that TWCS with stratification over entity clusters could further significantly reduce the annotation time. Compared to SRS, size stratification speeds up the evaluation process up to 40% (20% reduction compared to TWCS without stratification) and oracle stratification can make the annotation time less than 3 hours. Recall that MOVIE-SYN has synthetic labels generated by BMM introduced in Section 13.1.2. We explicitly correlate entity accuracy with entity cluster size using Eq ([eq:synthetic]). Hence, a simple strategy as size stratification could already do a great job to group clusters with similar entity accuracies, reduce overall variance and boost the efficiency of basic TWCS.

However, on NELL and MOVIE, we observe that applying stratification on TWCS does not help too much and it might be even slightly worse than the basic TWCS (as on NELL). This is because, in practice, cluster size may serve as a good signal indicating similarities among entity accuracies for large clusters but not for those small ones, and the overall variance is not reduced as we expected. However, the oracle stratification tells us that the cost can potentially be as low as about an hour on NELL. If we use good stratification strategies in term of grouping clusters with similar entity accuracy together, we are expected to achieve lower cost that close to the oracle evaluation cost. .

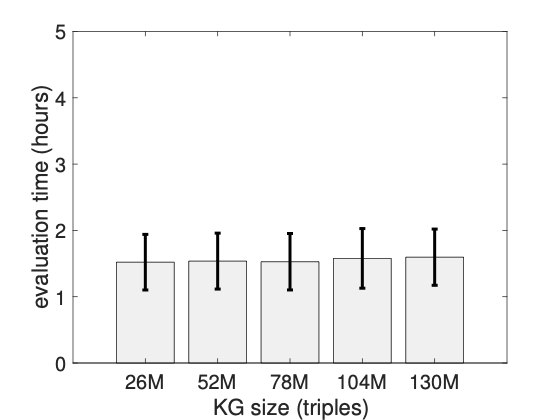

Scalability of TWCS

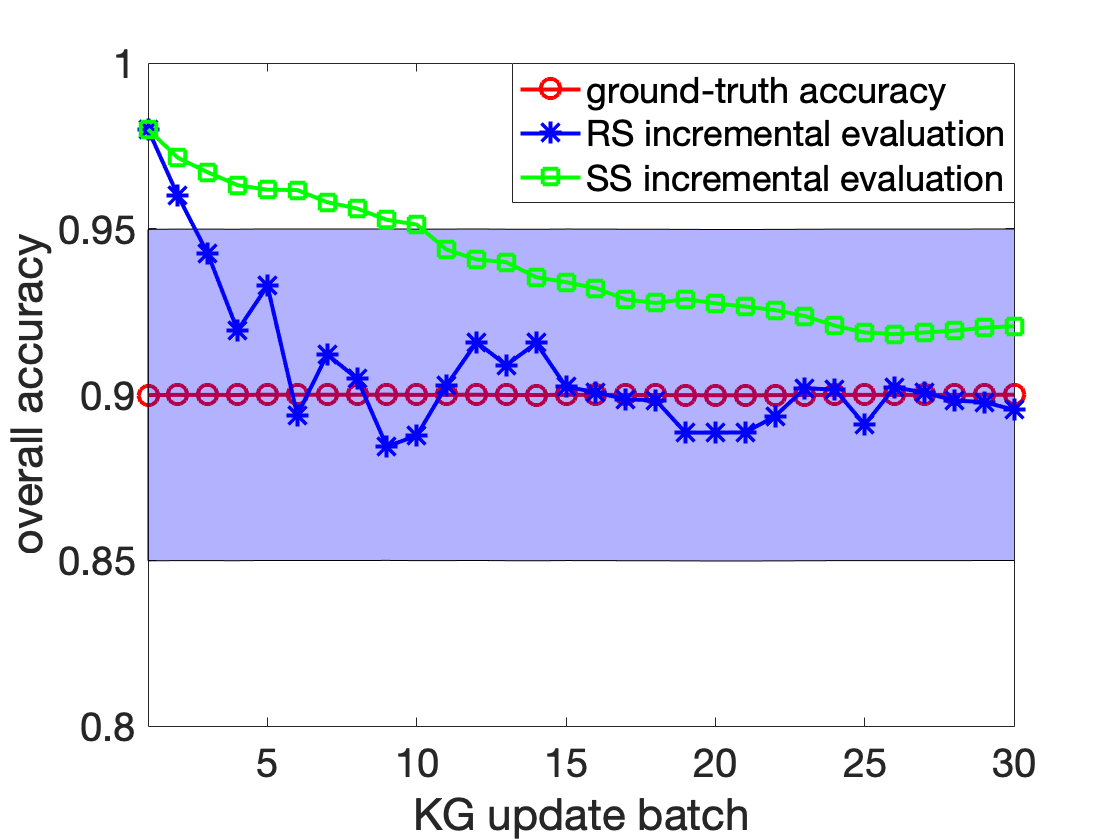

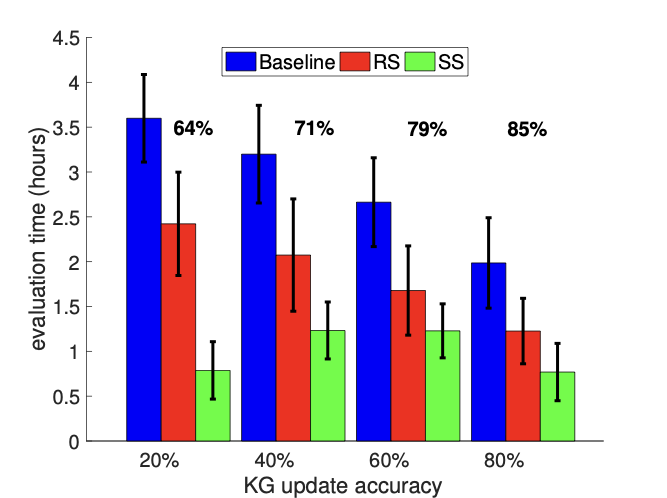

Incremental Evaluation on Evolving KG

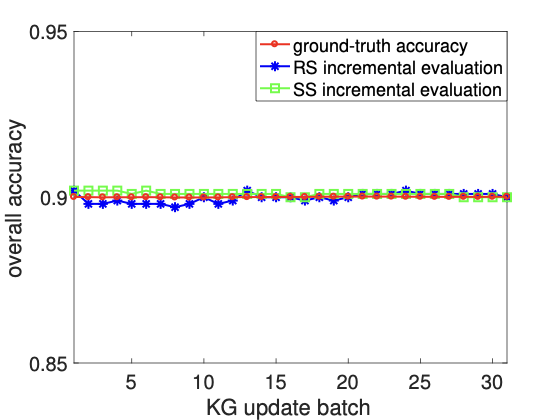

In this section, we present an in-depth investigation on evolving KG evaluations. First, we set the base KG to be a 50% subset randomly selected from MOVIE. Then, we draw multiple batches of random sets from MOVIE-FULL as KG updates. This setting better approximates the evolving KG behavior in real-life applications, as KG updates consist of both introducing new entities and enriching existing entities. Our evaluation framework can handle both cases. Since the gold accuracy of MOVIE is about 90%, we synthetically generate labels for the base KG using REM with $`r_\epsilon = 0.1`$, which also gives an overall accuracy around 90%.

Single Batch of Update

We start with a single update batch to the base KG to understand comparison of the proposed solutions.

In the first experiment, we fix the update accuracy at 90%, and vary the update size (number of triples) from 130K ($`\sim10\%`$ of base KG) to 796K ($`\sim50\%`$ of base KG). Figure 6-1 shows the comparison of annotation time of three solutions. The Baseline performs the worst because it discards the annotation results collected from previous round of evaluation and applies static evaluation from scratch. For RS, recall from Proposition [lemma:incremental-cost-bound] that the expected number of new triples replacing annotated triples in the reservoir would increase as the size of update grows; hence, the corresponding evaluation cost also goes up as applying larger KG update.

In the second experiment, we fix the update size at 796K triples, and vary the update accuracy from 20% to 80%. Note in this case, after applying the update, the overall accuracy also changes accordingly. Evaluation costs of all three methods are shown in Figure 6-2. It is not surprising to see that Baseline performs better as KG update is more accurate (or more precisely, the overall KG accuracy after applying update is more accurate). RS also performs better when update is more accurate. Even though we fix the update size, which makes the number of new triples inserted into the reservoir roughly remains the same, as overall KG is more accurate, we still can expect to annotate less additional triples to reduce the variance of estimation after sample update.

To conclude this section, incremental evaluation methods, RS and SS, are more efficient on evolving KGs. RS depends both on update size and overall accuracy, while

Sequence of Updates

Evaluation Cost Model

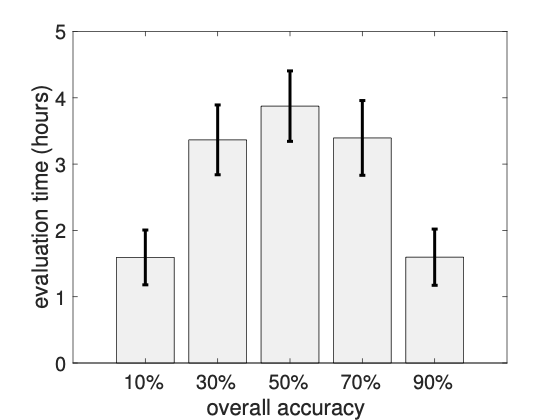

Prior research typically ignores the evaluation time needed by manual annotations. In this section, we study human annotators’ performance on different evaluation tasks and propose a cost function that approximates the manual annotation time. Analytically and empirically, we argue that annotating triples in groups of entities is more efficient than triple-level annotation.

Evaluation Model

Recall that subject or non-atomic object in the KG is represented by an id, which refers to a unique real-life entity. When manually annotating a $`(s,p,o)`$ triple, a connection between the id and the entity to which it refers must be first established. We name this process as Entity Identification. The next step is to collect evidence and verify the facts stated by the triple, which is referred to as Relationship Validation. In this paper, we consider the following general evaluation instructions for human annotators:

-

Entity Identification: Besides assigning annotators an Evaluation Task to audit, we also provide a small set of related information regarding to the subject of this Task. Annotators are required to use the provided information to construct a clear one-to-one connection between the subject and an entity using their best judgement, especially when there is ambiguity; that is, different entities share the same name or some attributes.

-

Relationship Validation: This step asks annotators for a cross-source verification; that is, searching for evidence of subject-object relationship from multiple sources (if possible) and making sure the information regarding the fact is correct and consistent. Once we have a clear context on the Evaluation Task from the first step of Entity Identification, relationship validation would be a straightforward yes or no judgement.

We ask one human annotator to perform several annotation tasks on the MOVIE KG,4 and track the cumulative time spent after annotating each triple. In the first task (which we call “triple level”), we draw 50 triples randomly from the KG, and ensure that all have distinct subject ids. In the second task (which we call “entity level”), we select entity clusters at random, and from each selected cluster draw at most 5 triples at random; the total number of triples is still 50, but they come from only 11 entity clusters. The cumulative evaluation time is reported in Figure 8.

The time required by evaluating triple-level task increases approximately linearly in the number of triples, and is significantly longer than the time required for entity-level task, as we expected. If we take a closer look at the plot for the entity-level task, it is not difficult to see that the evaluation cost on subsequent triples from an identified entity cluster is much lower on average compared to independently evaluating a triple (straight dotted lines).

Cost Function

We define a cost function based on the proposed evaluation model.

Given a sampled subset $`G'`$ from KG, the approximate evaluation cost is defined as

\begin{equation}

\label{eq:simplified-cost}

\cost(G') = \card{E'}\cdot c_1 + \card{G'}\cdot c_2,

\end{equation}where $`E'`$ is the set of distinct ids from $`G'`$. $`c_1, c_2`$ are the average cost of entity identification and relationship validation, respectively.

Average costs $`c_1`$ and $`c_2`$ are calculated from empirical evaluation costs by human annotators over multiple evaluation tasks. In reality, the cost of evaluating triples vary by different human annotators, but in practice we found taking averages is adequate for the purpose of optimization because they still capture the essential characteristics of the cost function. More details on the annotation cost study can be found in the experiment section.

📊 논문 시각자료 (Figures)

A Note of Gratitude

The copyright of this content belongs to the respective researchers. We deeply appreciate their hard work and contribution to the advancement of human civilization.-

In an actual annotation task, each triple is associated with some context information. Annotators need to spend time first identifying the subject, the object or both. ↩︎

-

According to , it takes more than 5 minutes to find the next triple to be manually evaluated, even on the tiny KGs with less than 2,000 triples. ↩︎

-

IMDb terms of service: https://www.imdb.com/conditions ↩︎

-

MOVIE is a knowledge graph constructed from IMDb and WiKiData. More detailed information can be found in Section 13.1.1. ↩︎