We present the surprising finding that a language model's reasoning capabilities can be improved by training on synthetic datasets of chain-of-thought (CoT) traces from more capable models, even when all of those traces lead to an incorrect final answer. Our experiments show this approach can yield better performance on reasoning tasks than training on human-annotated datasets. We hypothesize that two key factors explain this phenomenon: first, the distribution of synthetic data is inherently closer to the language model's own distribution, making it more amenable to learning. Second, these `incorrect' traces are often only partially flawed and contain valid reasoning steps from which the model can learn. To further test the first hypothesis, we use a language model to paraphrase human-annotated traces -- shifting their distribution closer to the model's own distribution -- and show that this improves performance. For the second hypothesis, we introduce increasingly flawed CoT traces and study to what extent models are tolerant to these flaws. We demonstrate our findings across various reasoning domains like math, algorithmic reasoning and code generation using MATH, GSM8K, Countdown and MBPP datasets on various language models ranging from 1.5B to 9B across Qwen, Llama, and Gemma models. Our study shows that curating datasets that are closer to the model's distribution is a critical aspect to consider. We also show that a correct final answer is not always a reliable indicator of a faithful reasoning process.

Large language models (LLMs) have made rapid progress on reasoning tasks, often using supervised fine-tuning on chain-of-thought (CoT) traces (Guo et al., 2025a;Bercovich et al., 2025;Ye et al., 2025). A common assumption in this line of research is that correctness is the primary determinant of data quality: the more correct a dataset is, the better it should be for training (Ye et al., 2025;Muennighoff et al., 2025). This assumption has guided the construction of widely used reasoning datasets, which typically rely on heavy human annotation (Hendrycks et al., 2021a;Cobbe et al., 2021) or filtering of model outputs with rule-based verifiers, that validate the CoT traces via final-answer checking (Guo et al., 2025b;Zelikman et al., 2022).

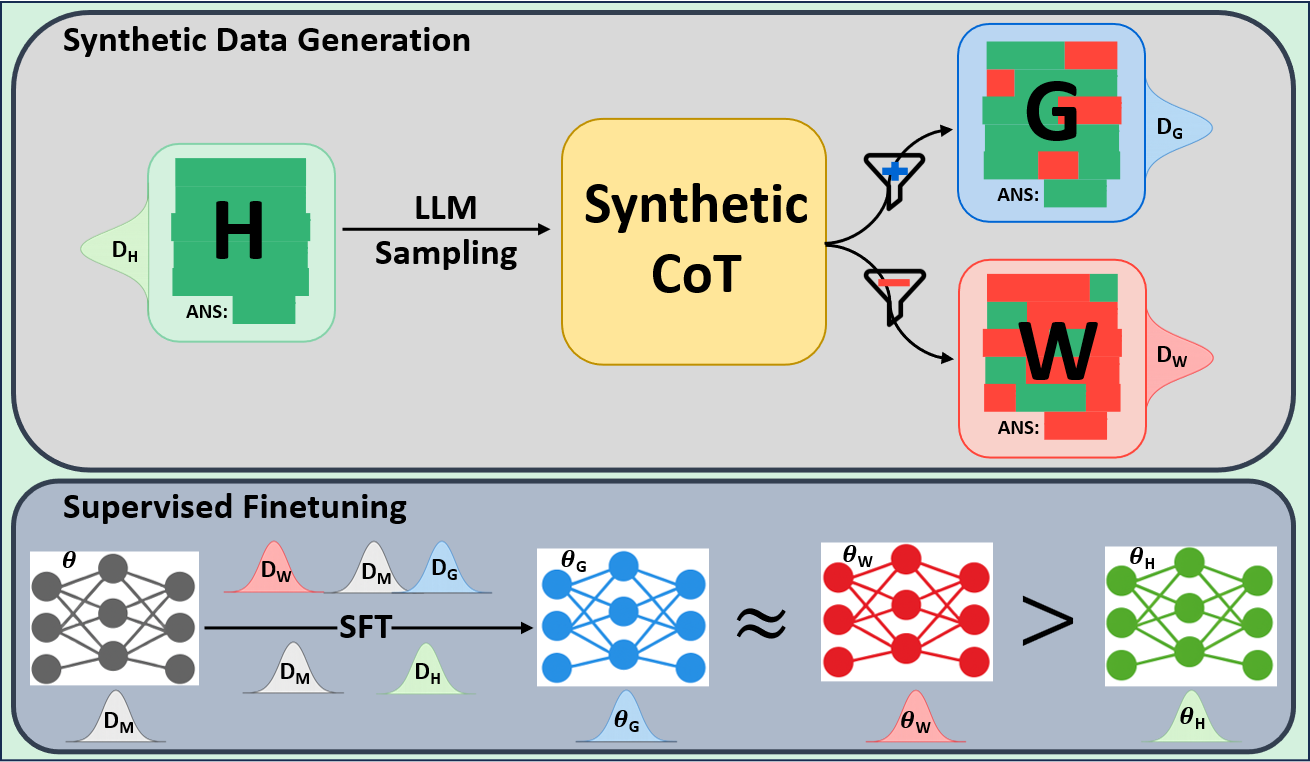

In this work we consider three broad categories of reasoning datasets that could be used to finetune a model: (1) Human-annotated and written traces -fully correct and carefully verified. These are treated as the gold standard. However, these traces may be far from the model’s distribution. (2) Synthetic traces generated from more capable models, typically from the same family, leading to correct answers -often filtered using rule-based verifiers that check only the final solution. These traces are closer to the distribution of the model being finetuned, but their reasoning steps may still be partially flawed. (3) Synthetic traces generated from more capable models, typically from the same family, leading to incorrect answers -generally discarded in existing pipelines. Yet these Categories (1) and ( 2) are consistently favored in prior work Ye et al. (2025); Guo et al. (2025b); Zelikman et al. (2022). Human-annotated data is trusted for correctness, while model-generated correct-answer traces provide scale. Category (3), however, is largely ignored under the assumption that incorrect answers imply poor reasoning. Works such as (Setlur et al., 2024;Aygün et al., 2021) propose to utilize incorrect traces for training better models in a contrastive setting or to train better verifiers. However, whether these traces can directly be useful for improving math reasoning has not been thoroughly tested.

We therefore pose two questions: (1) Can model-generated CoT traces that lead to incorrect final answers still directly help models learn to reason better -and if so, why? (2) Should we prioritize fully correct human-written traces that may lie further from the model’s output distribution, or model-generated traces that are closer to this distribution -even if they are imperfect?

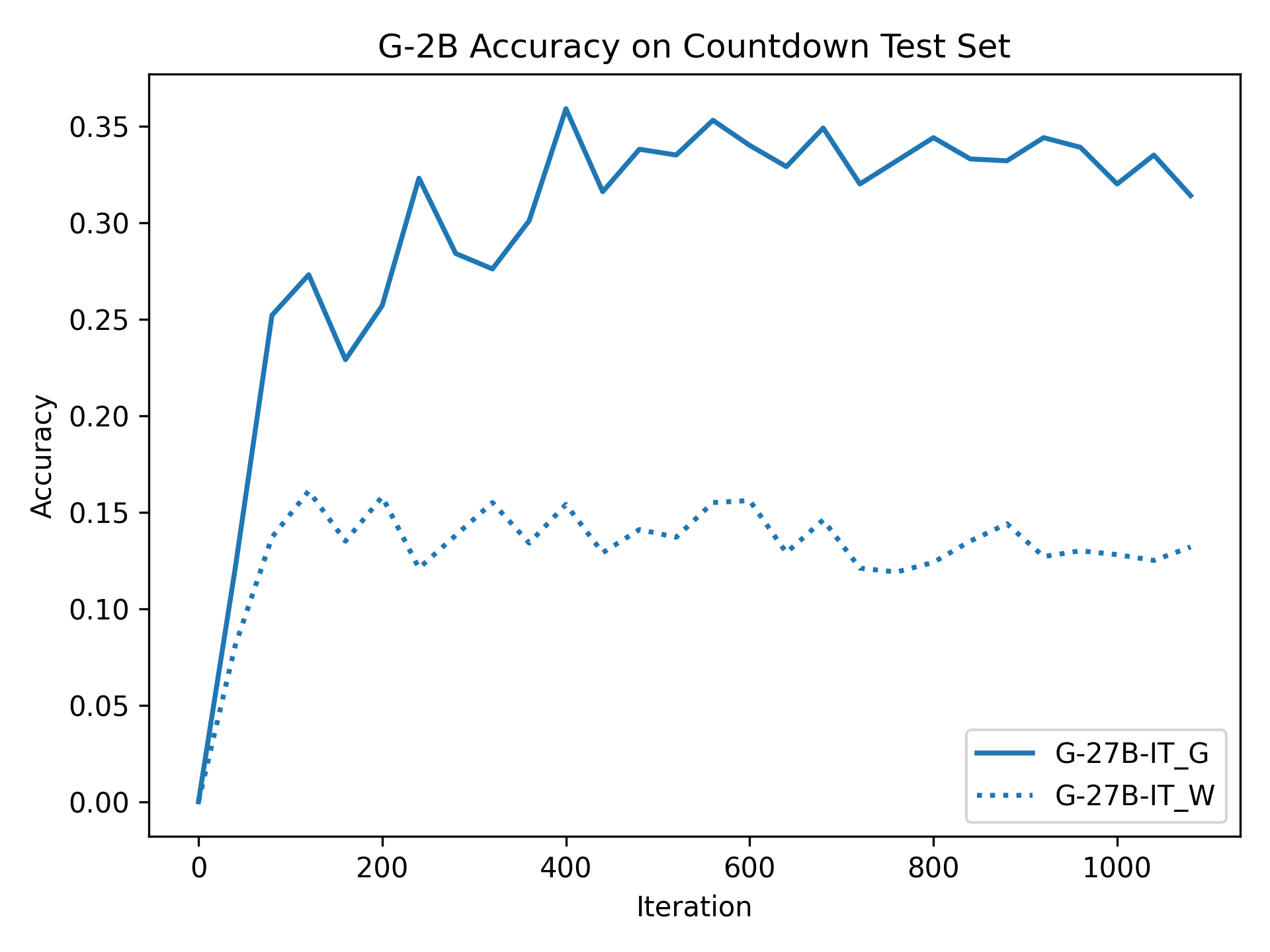

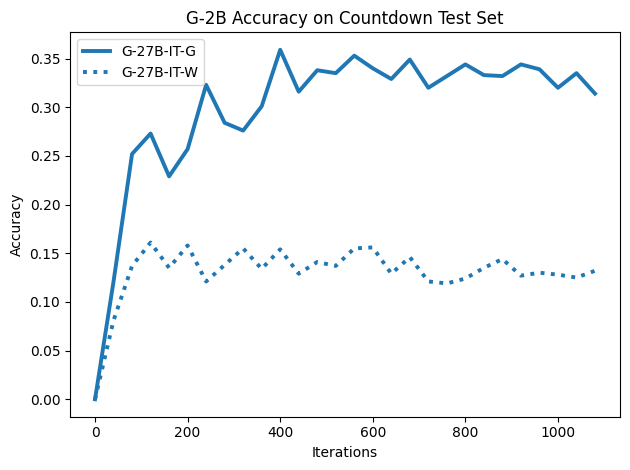

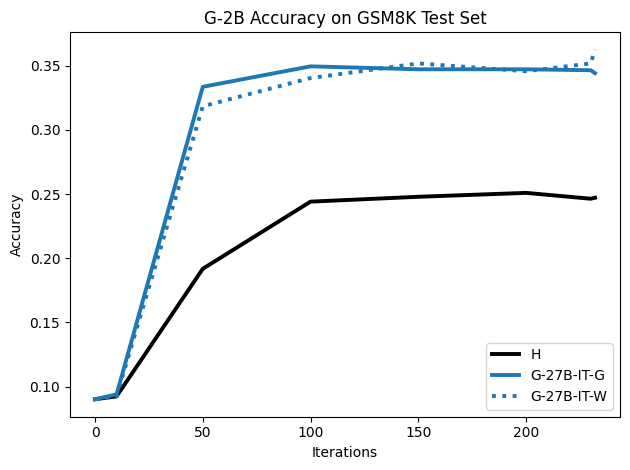

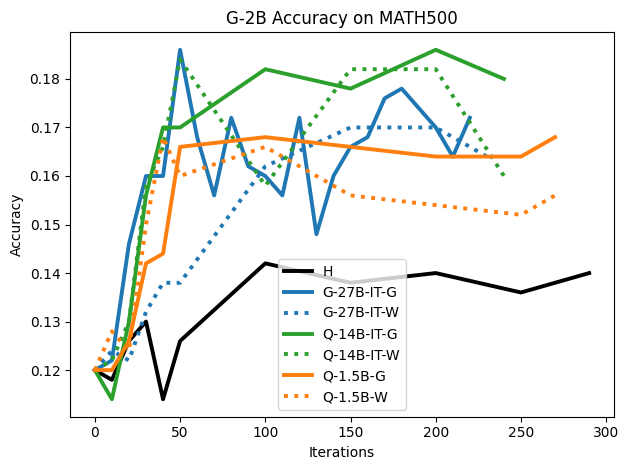

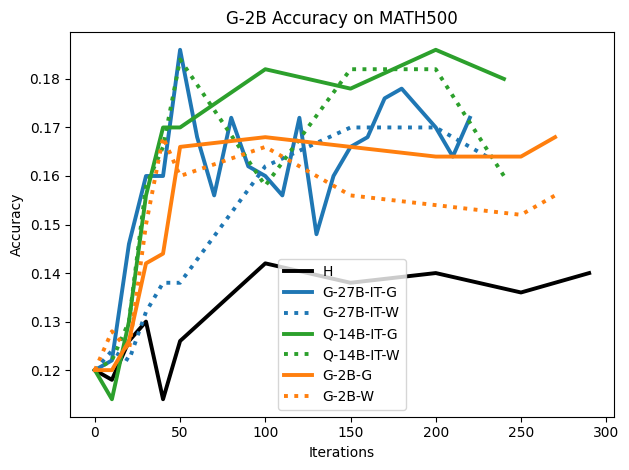

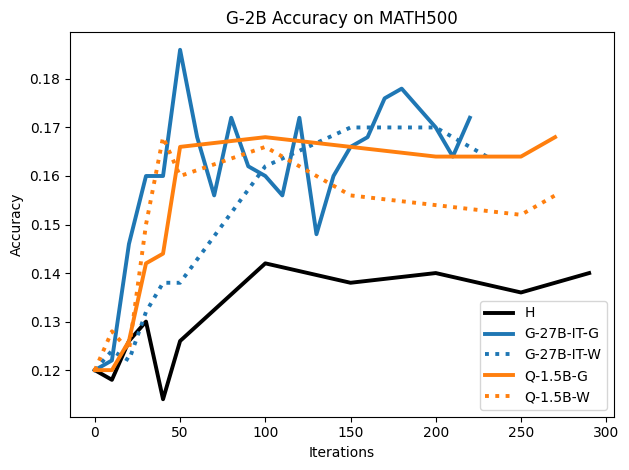

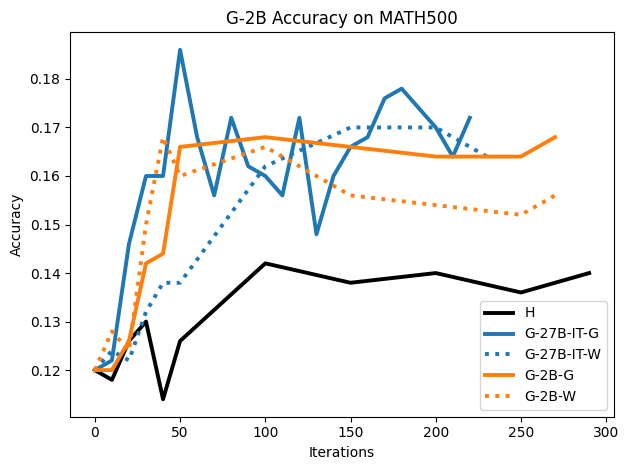

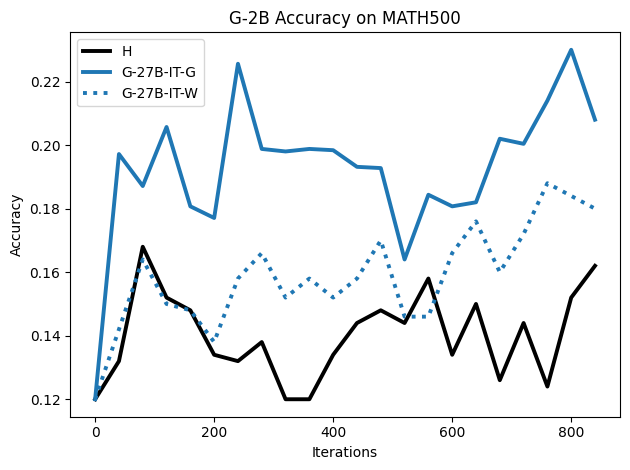

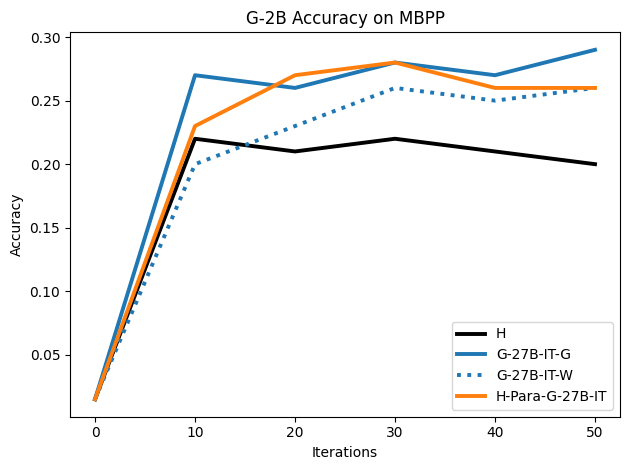

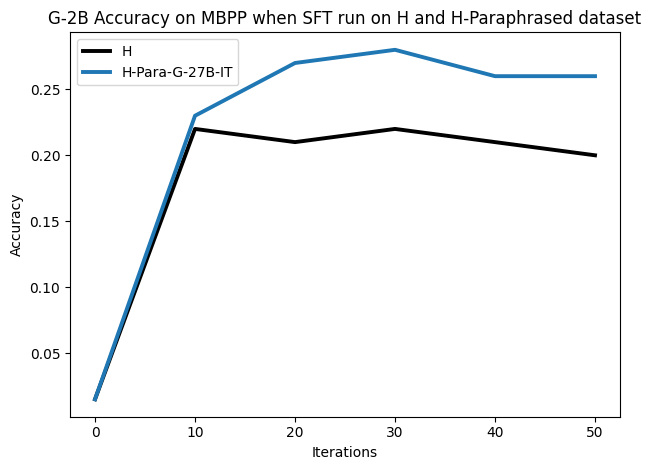

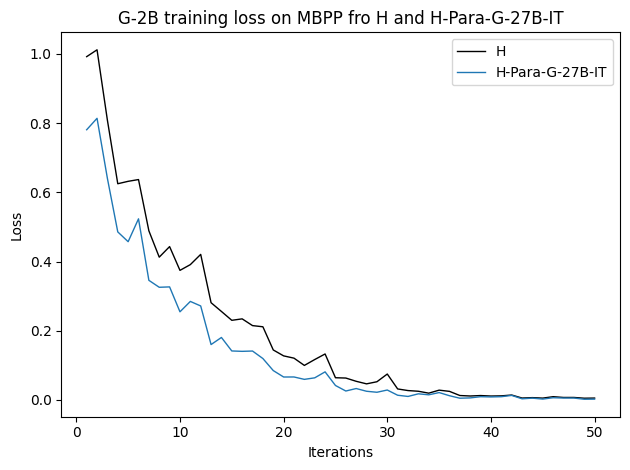

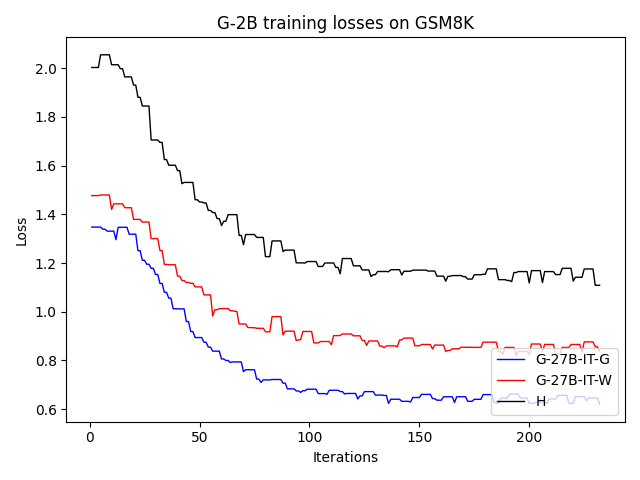

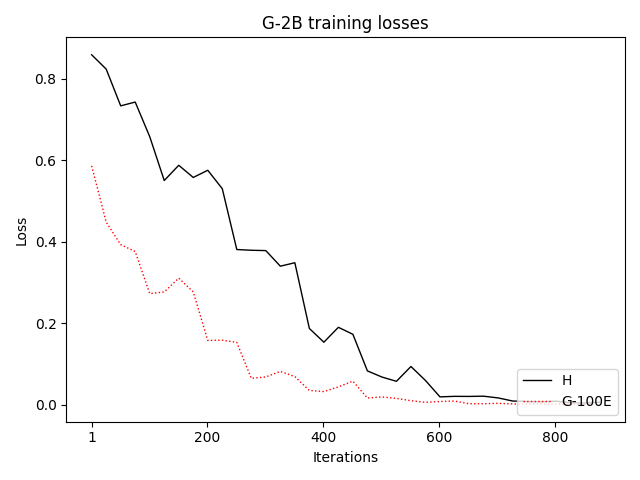

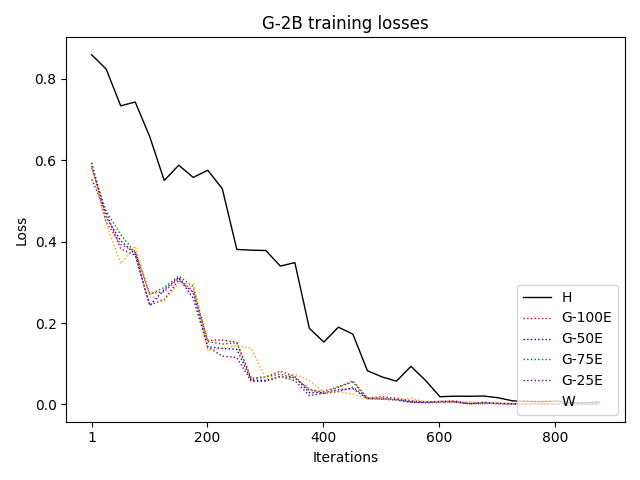

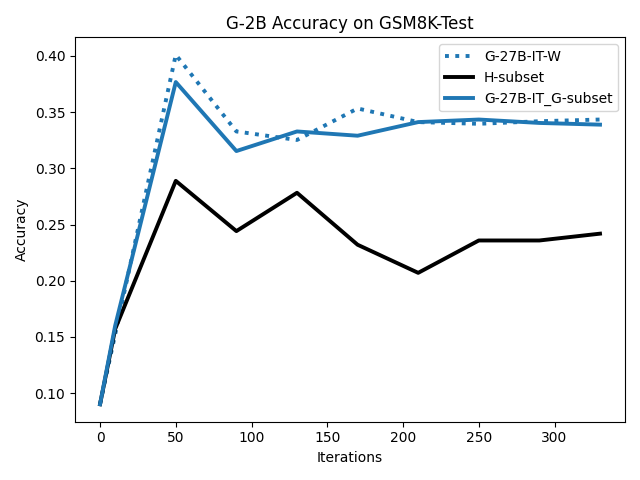

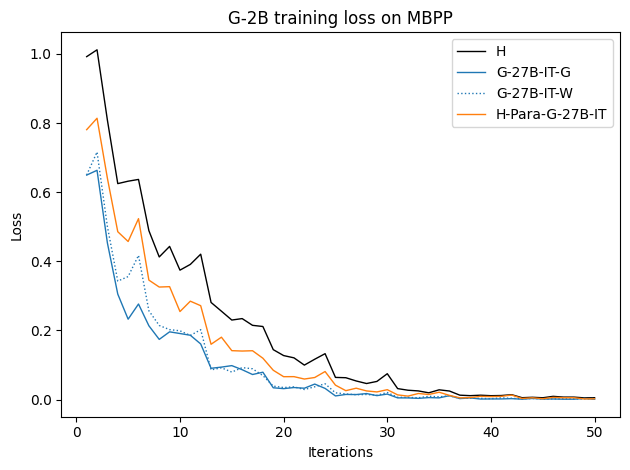

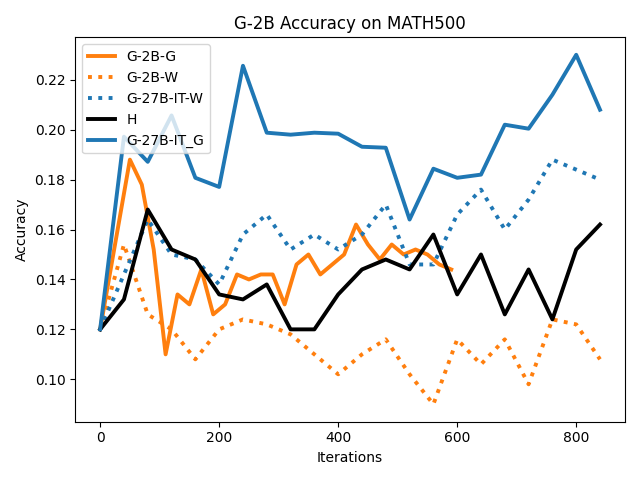

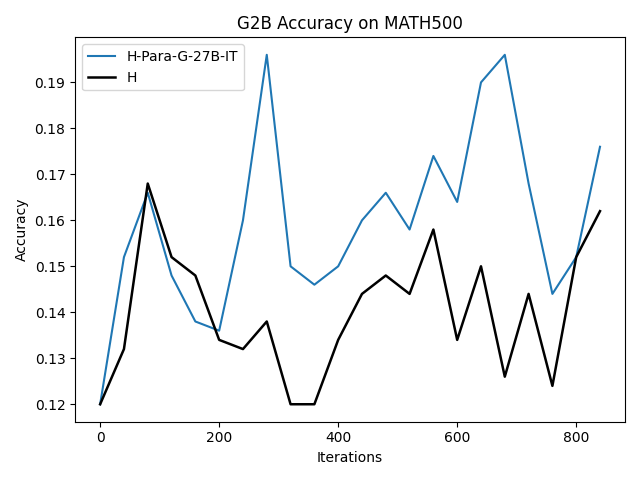

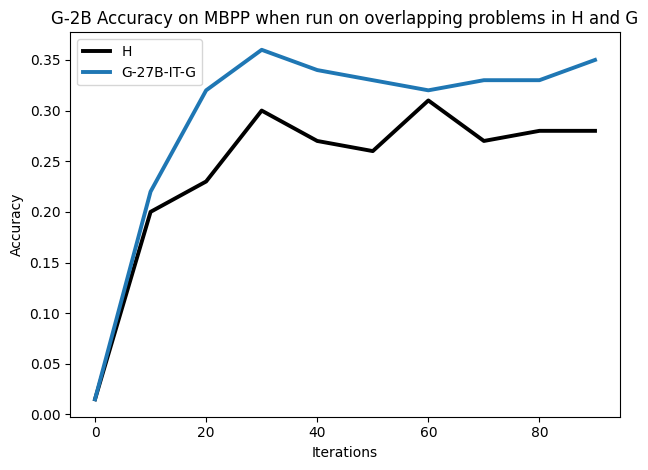

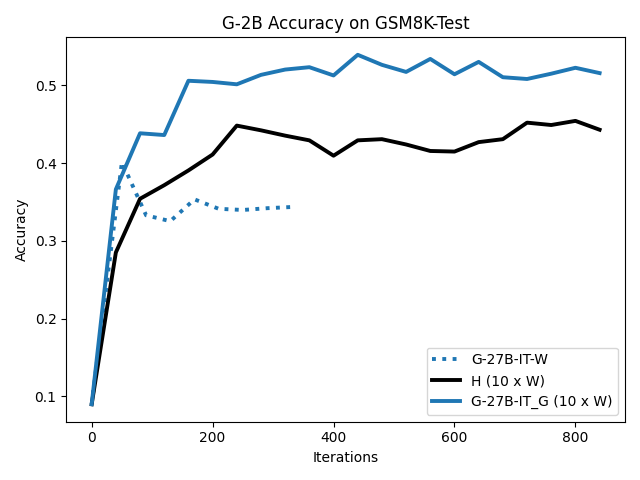

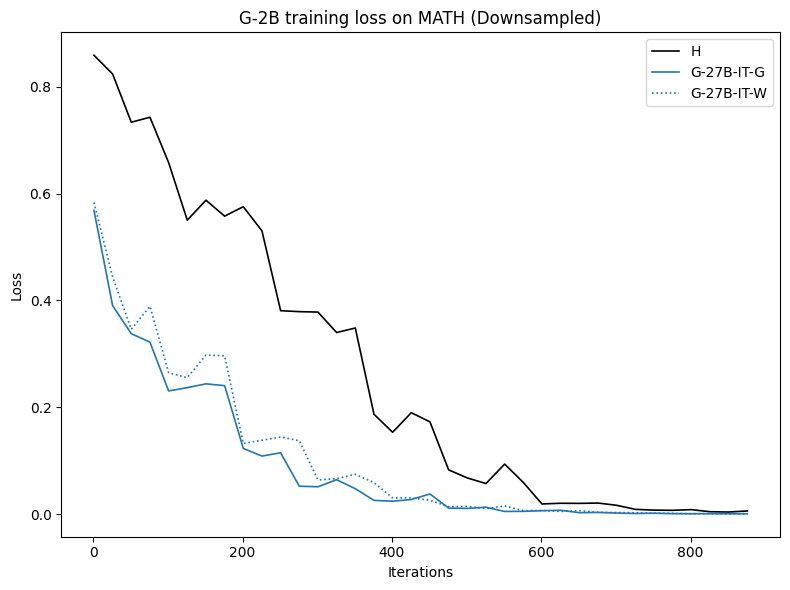

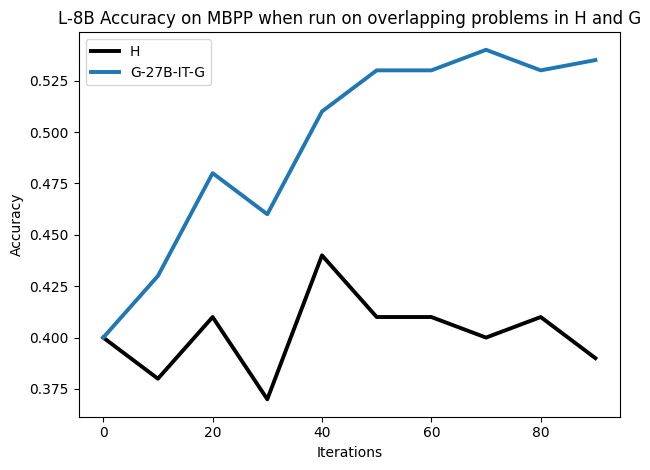

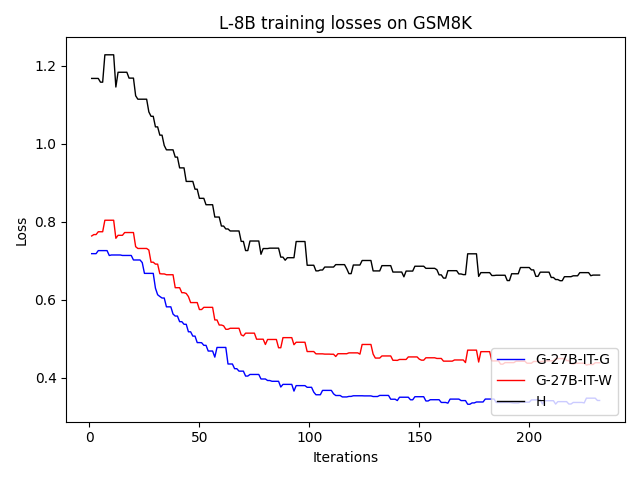

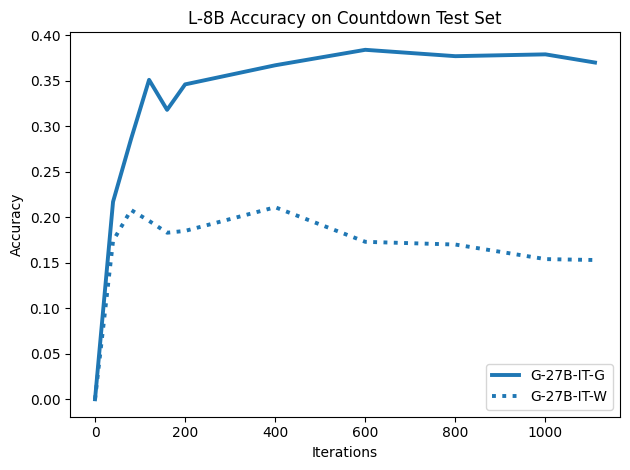

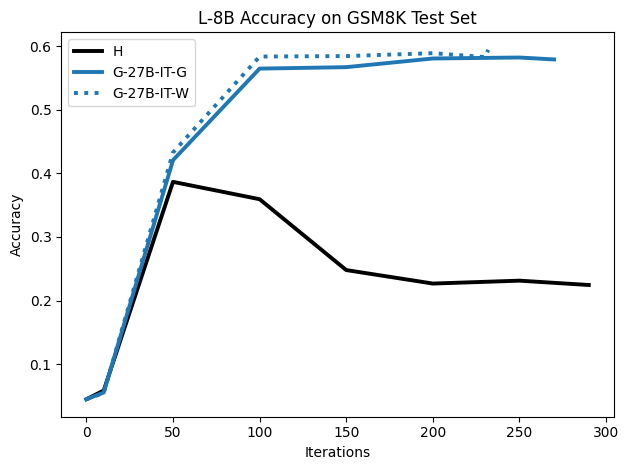

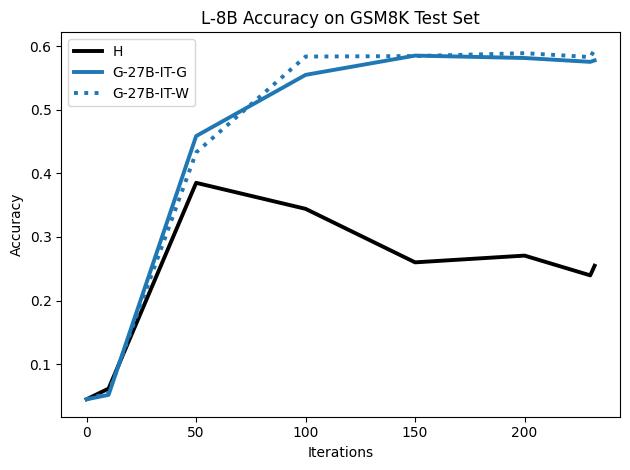

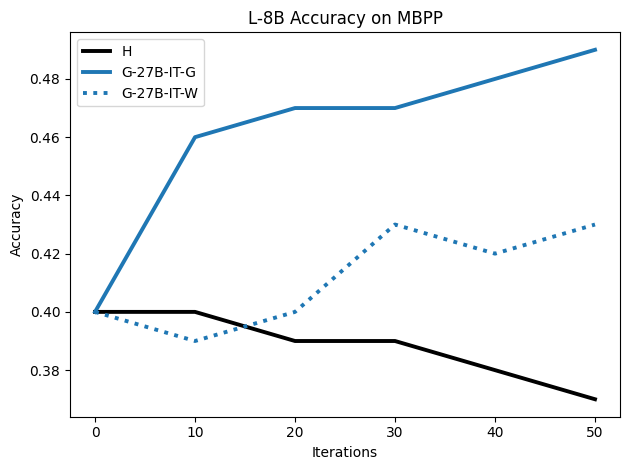

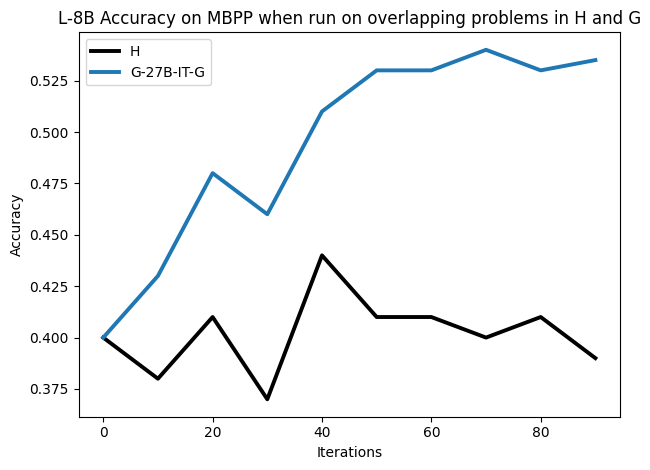

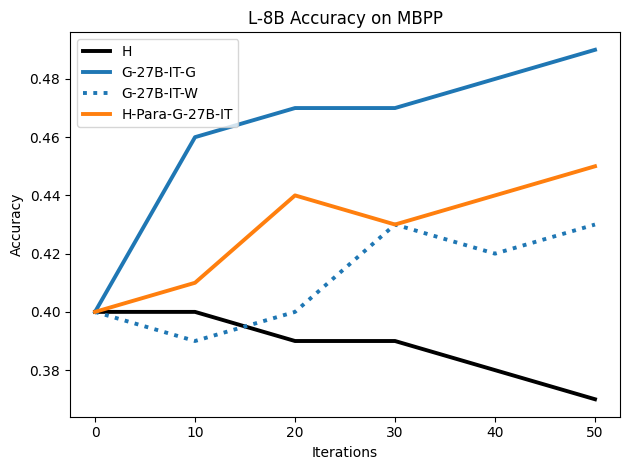

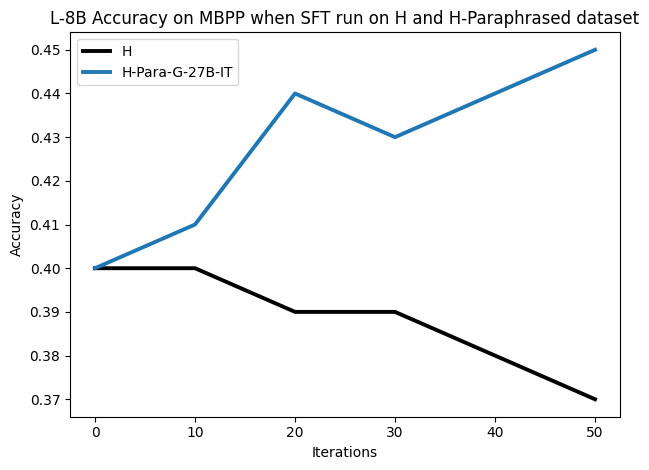

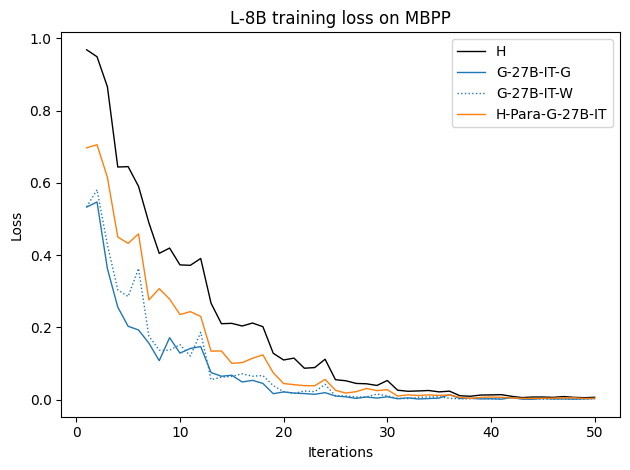

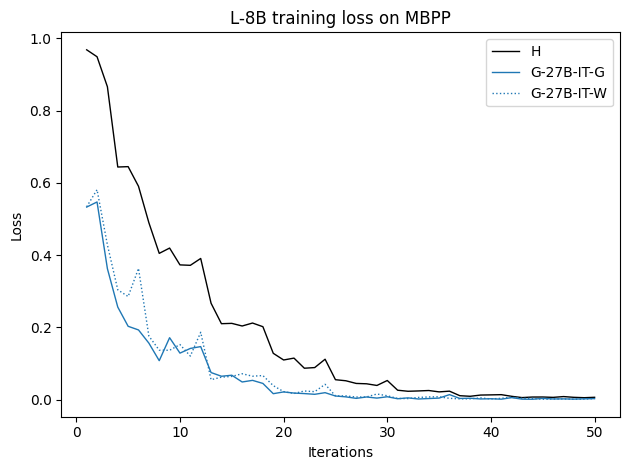

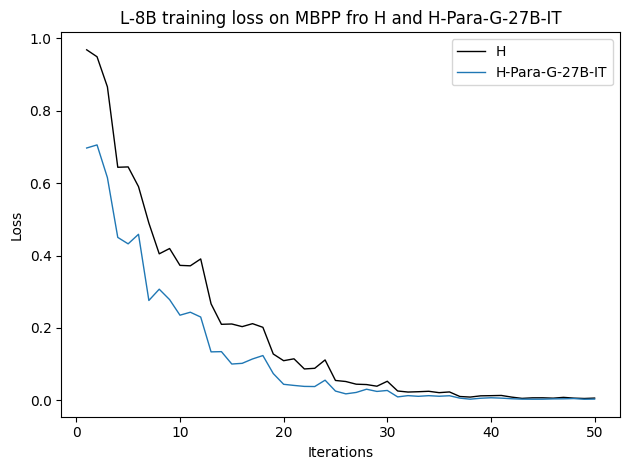

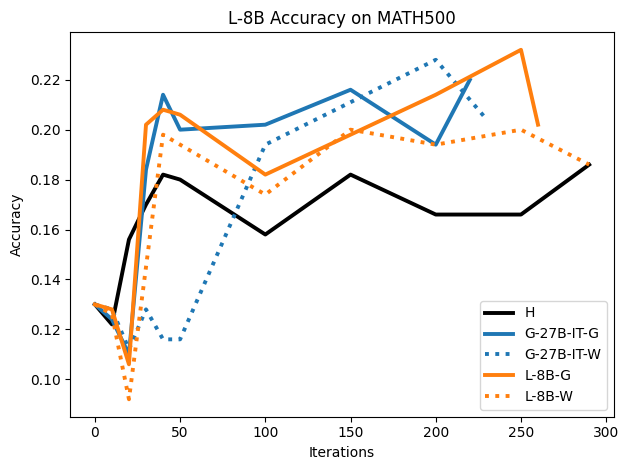

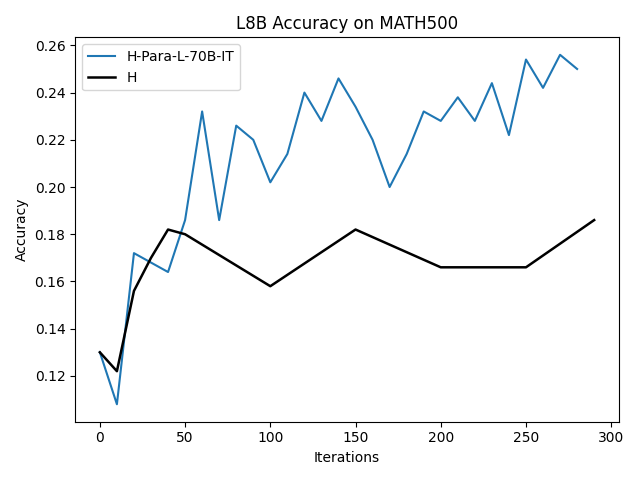

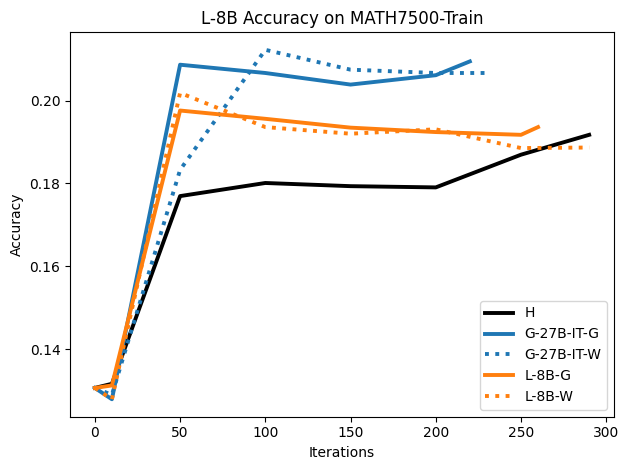

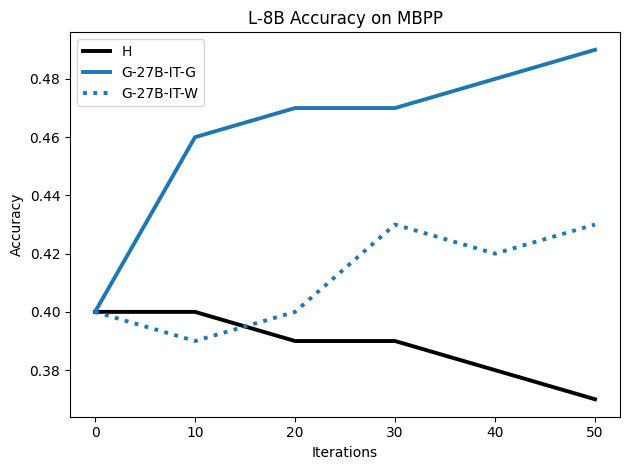

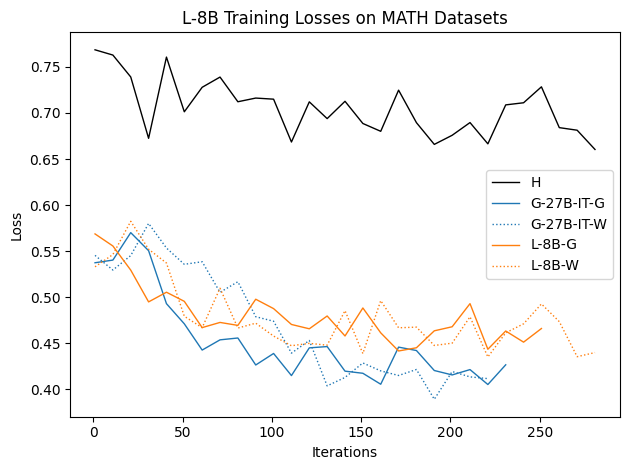

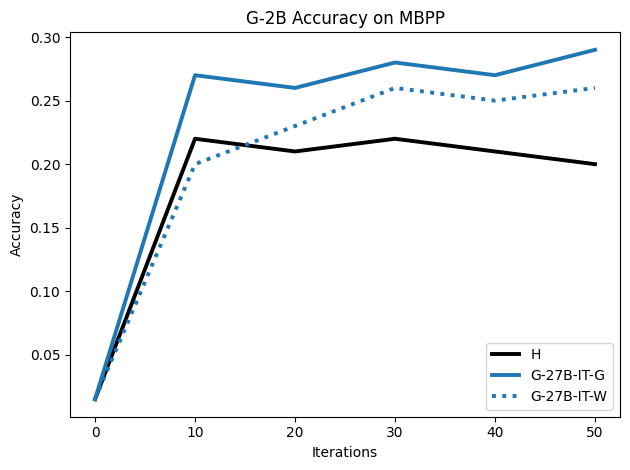

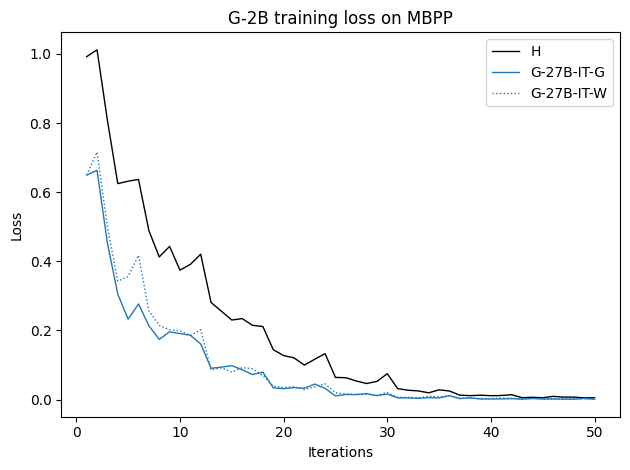

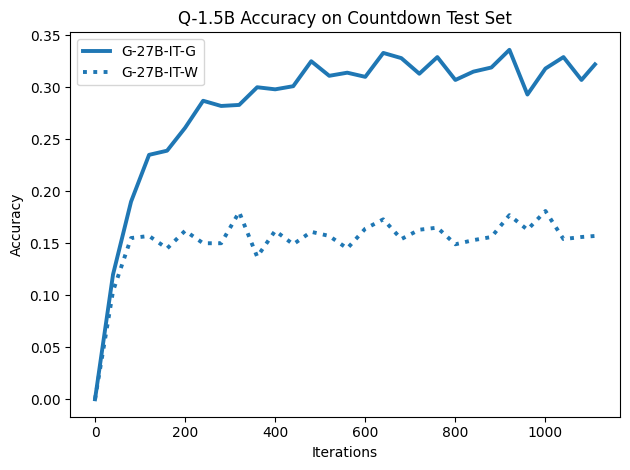

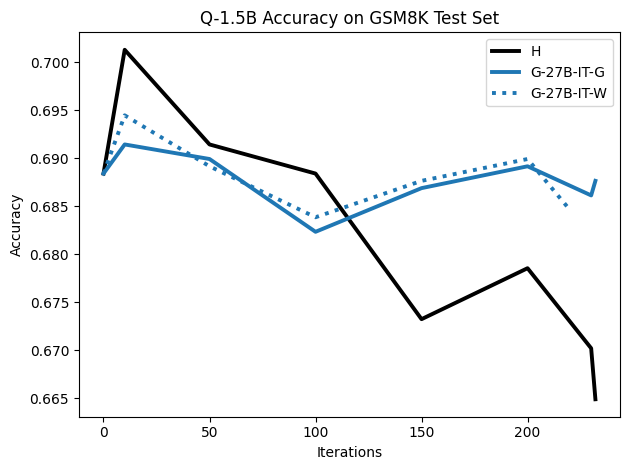

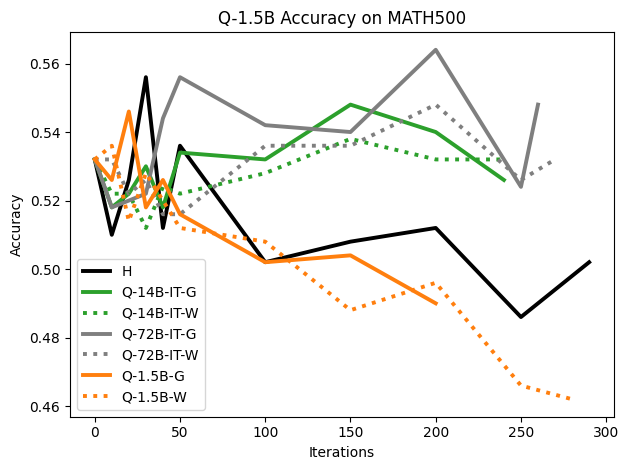

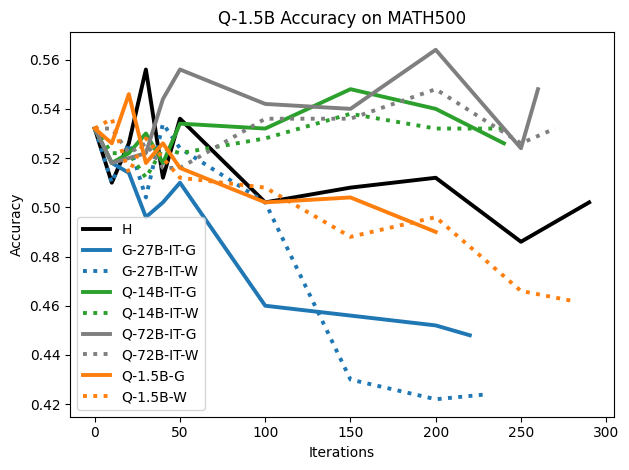

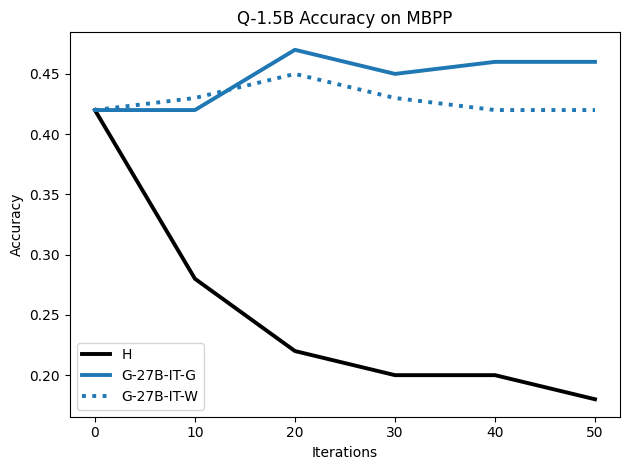

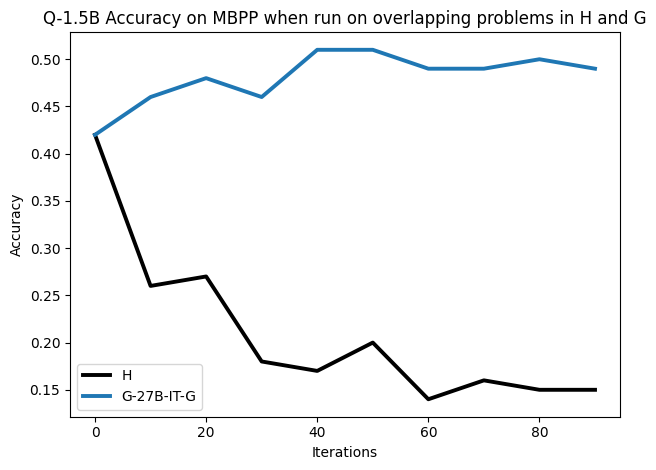

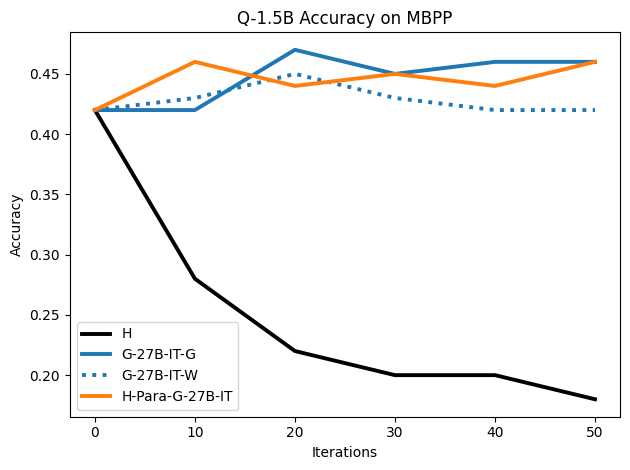

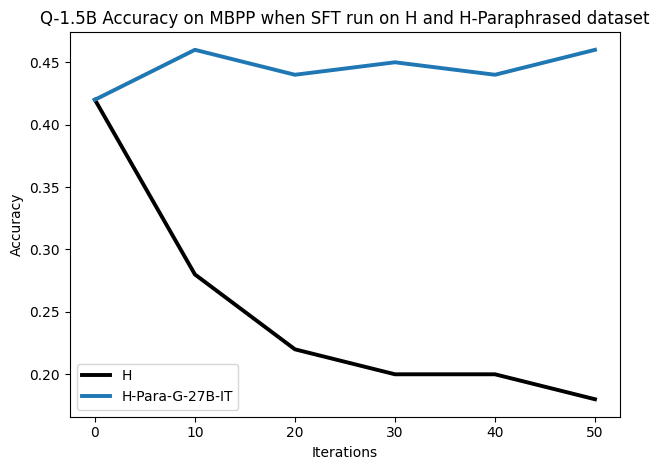

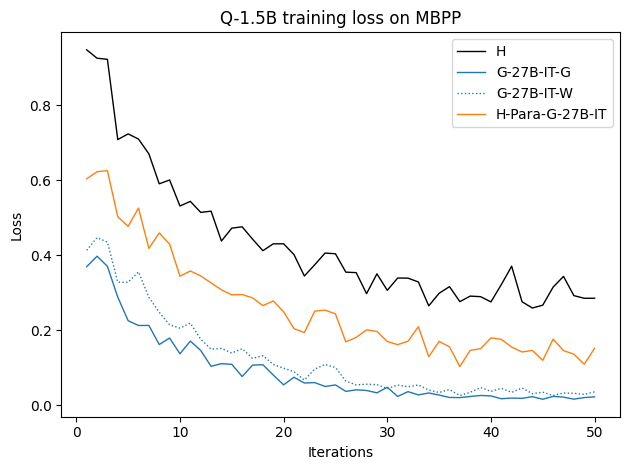

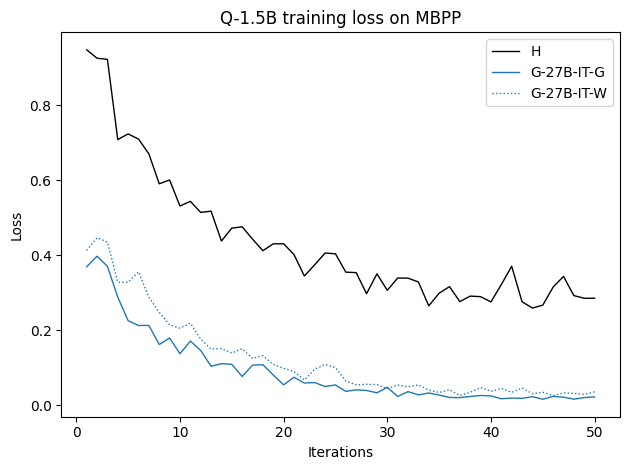

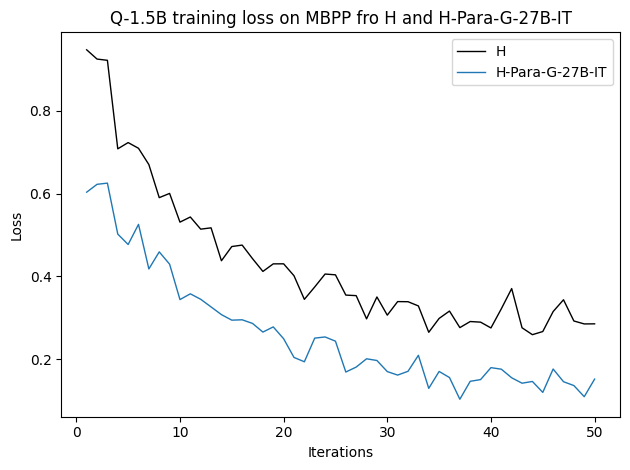

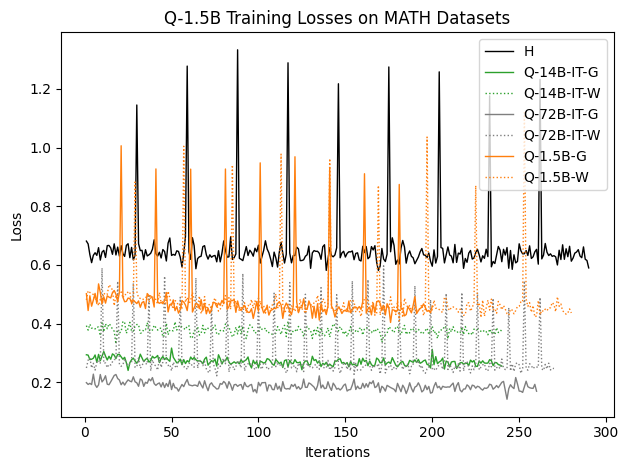

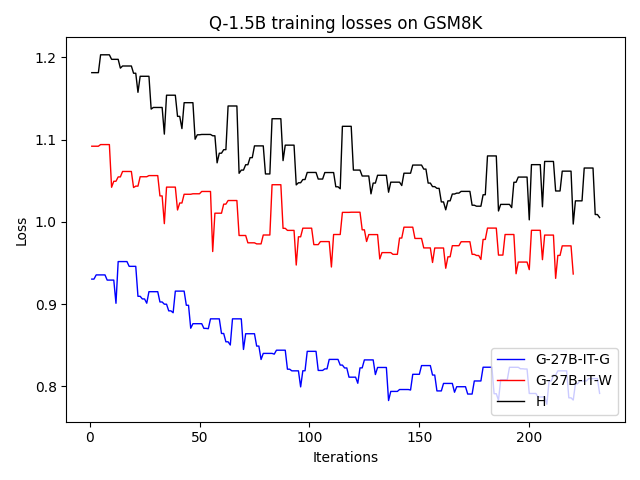

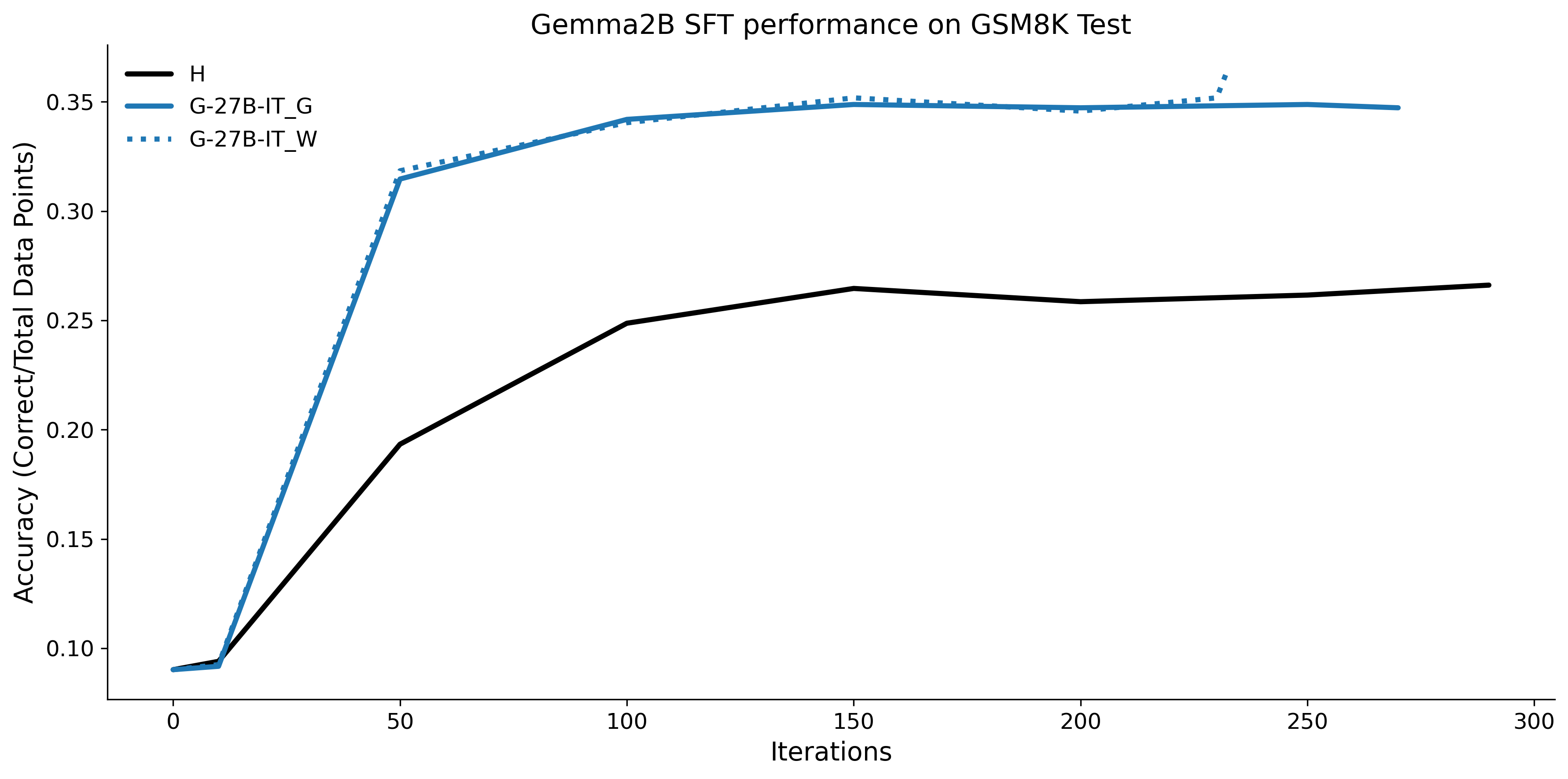

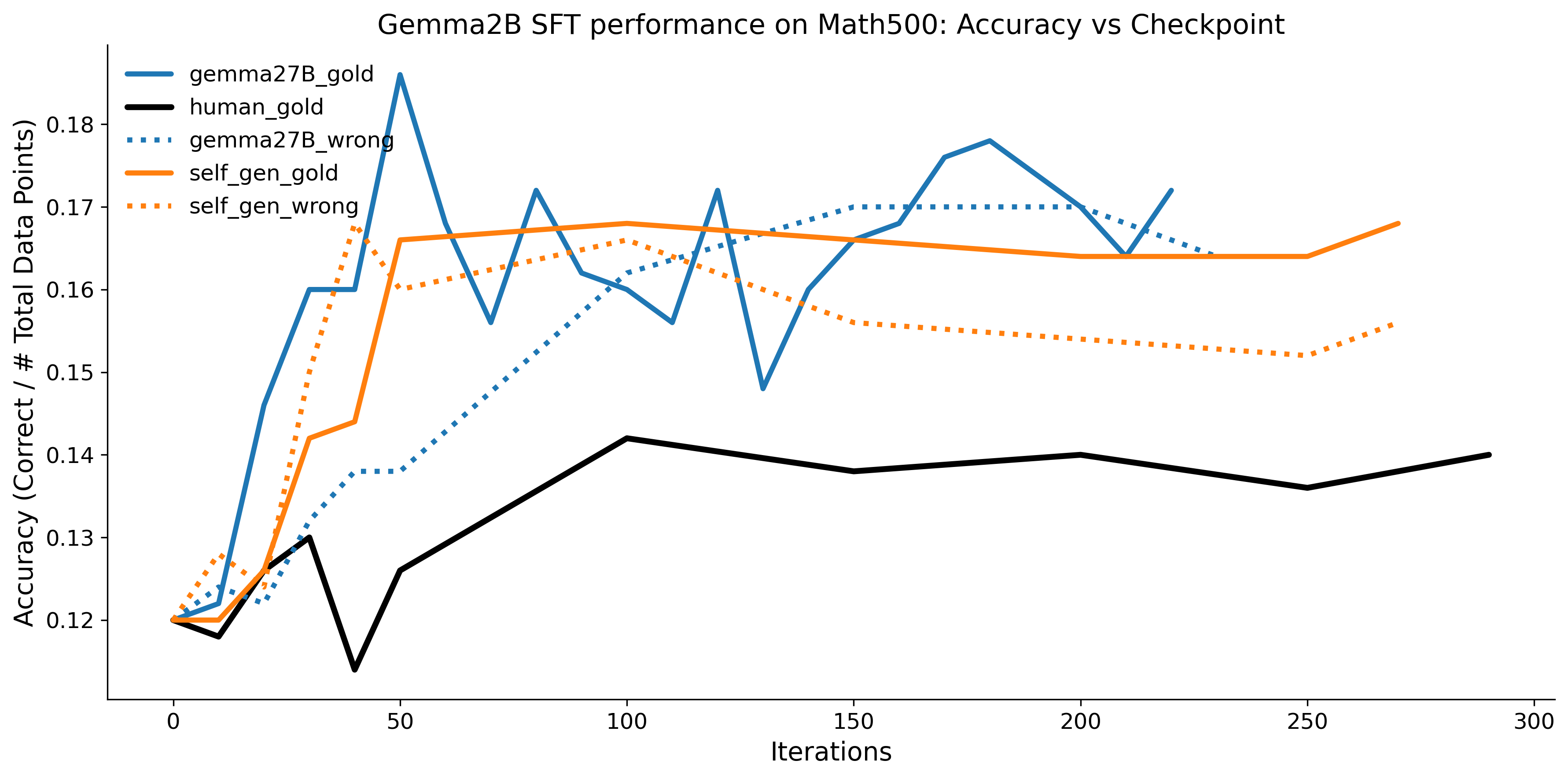

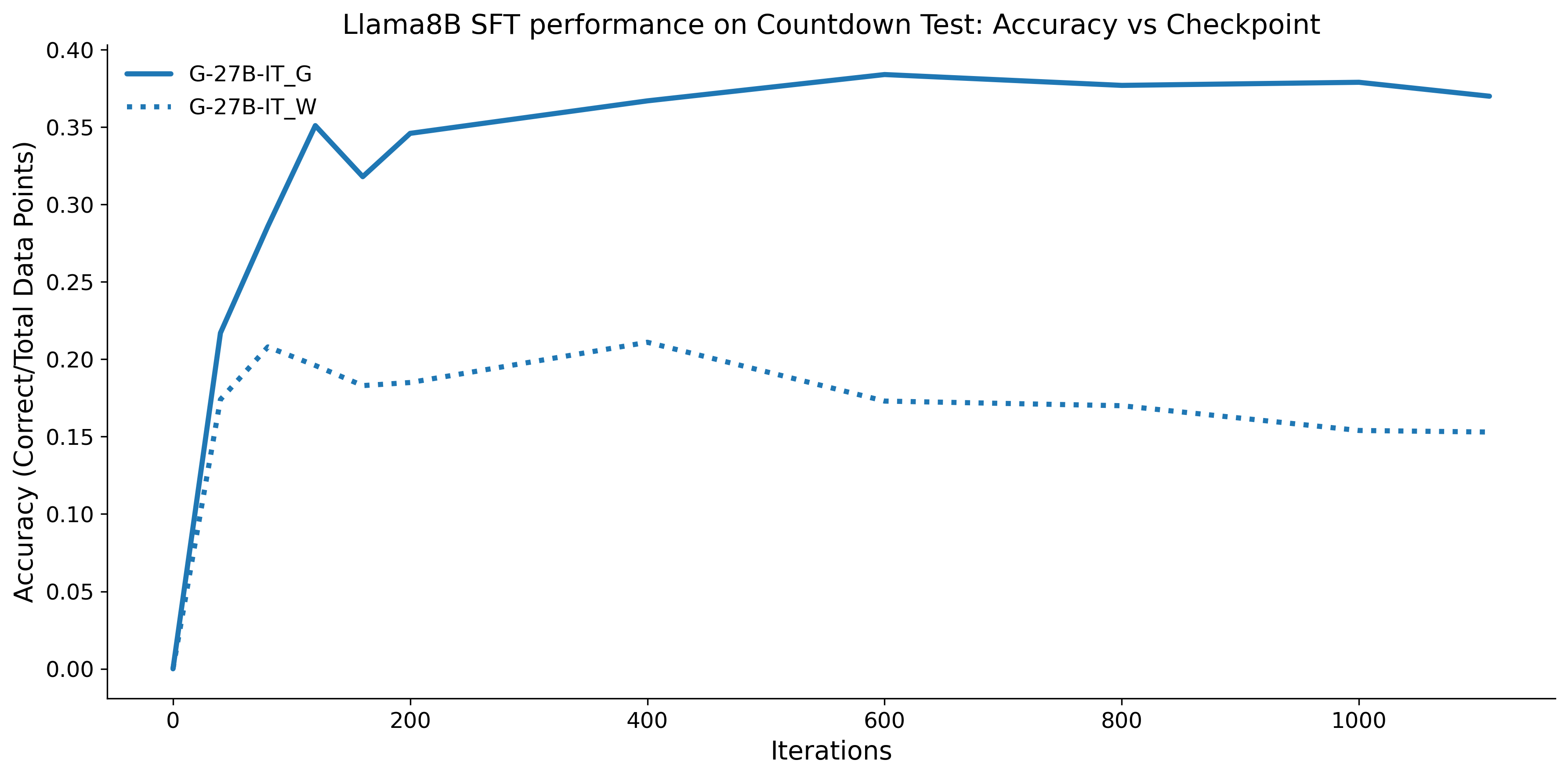

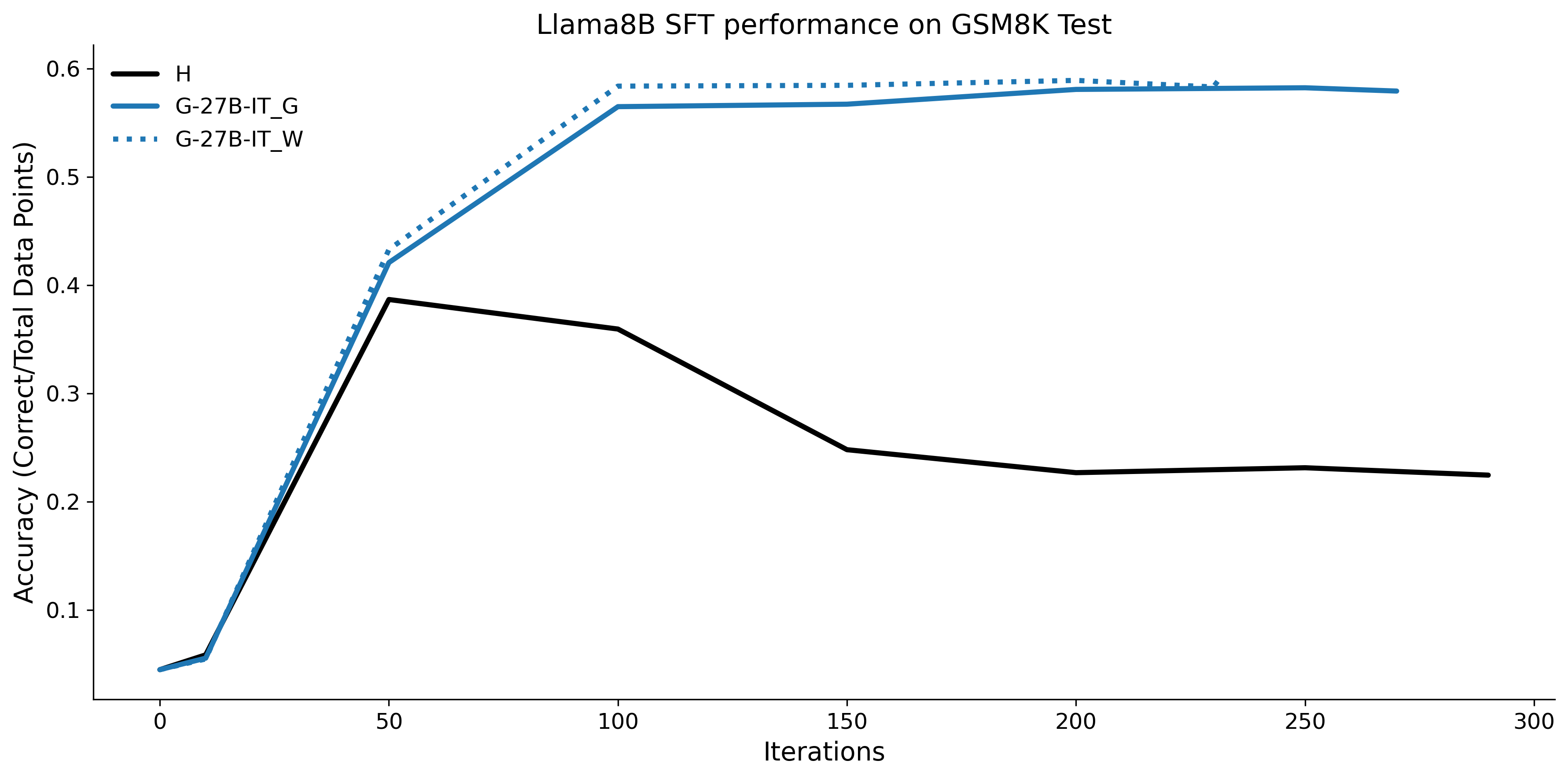

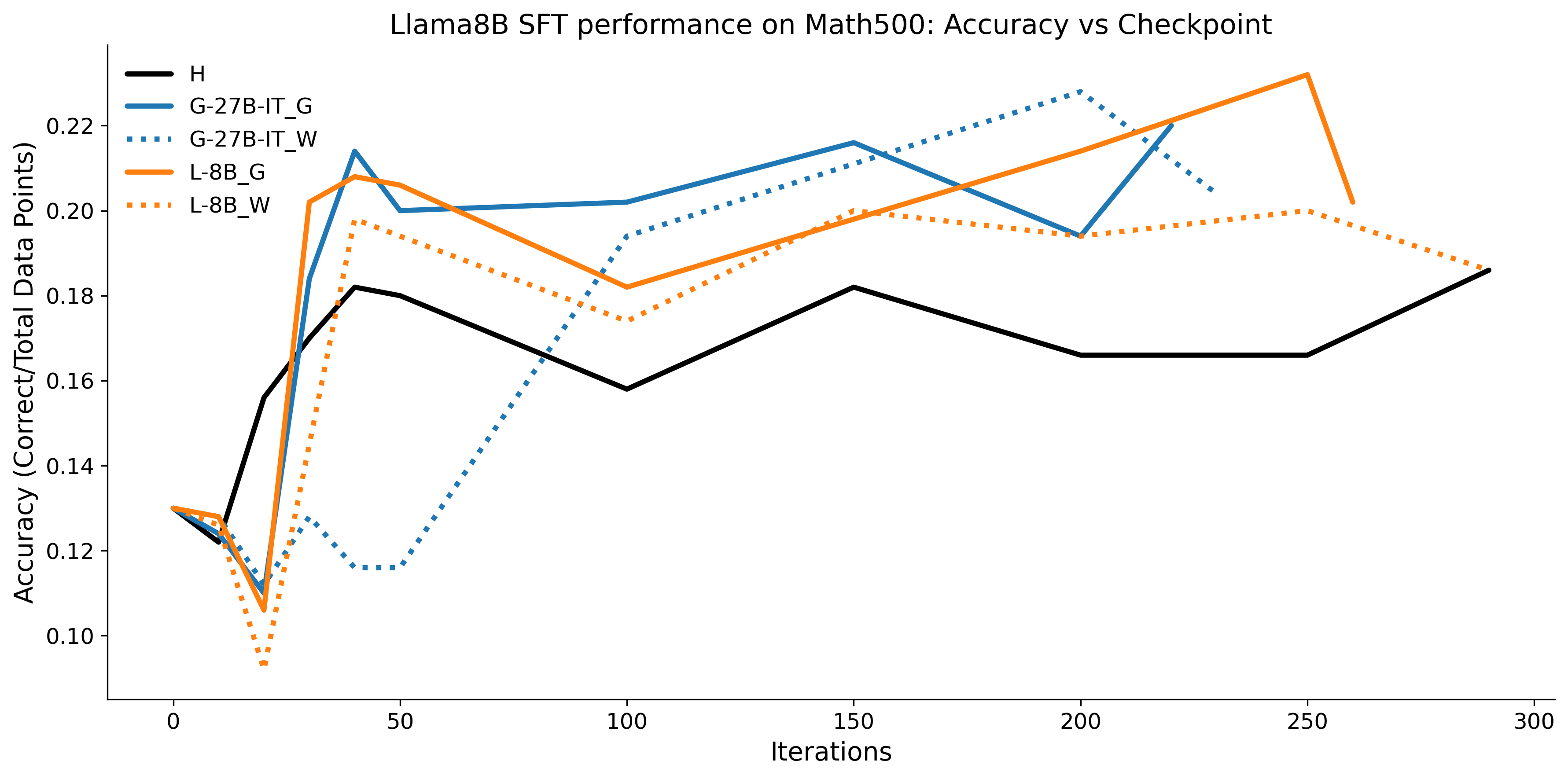

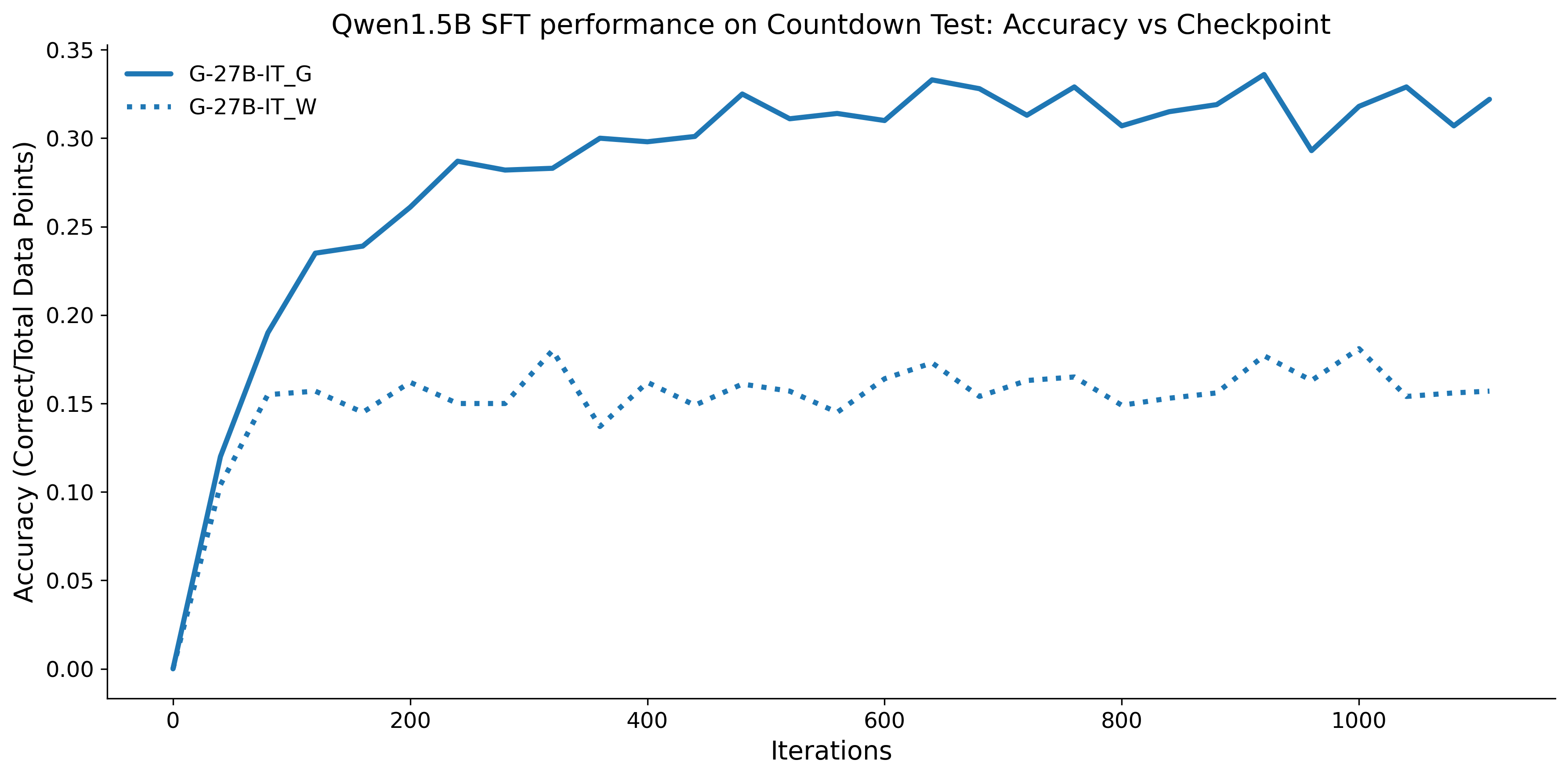

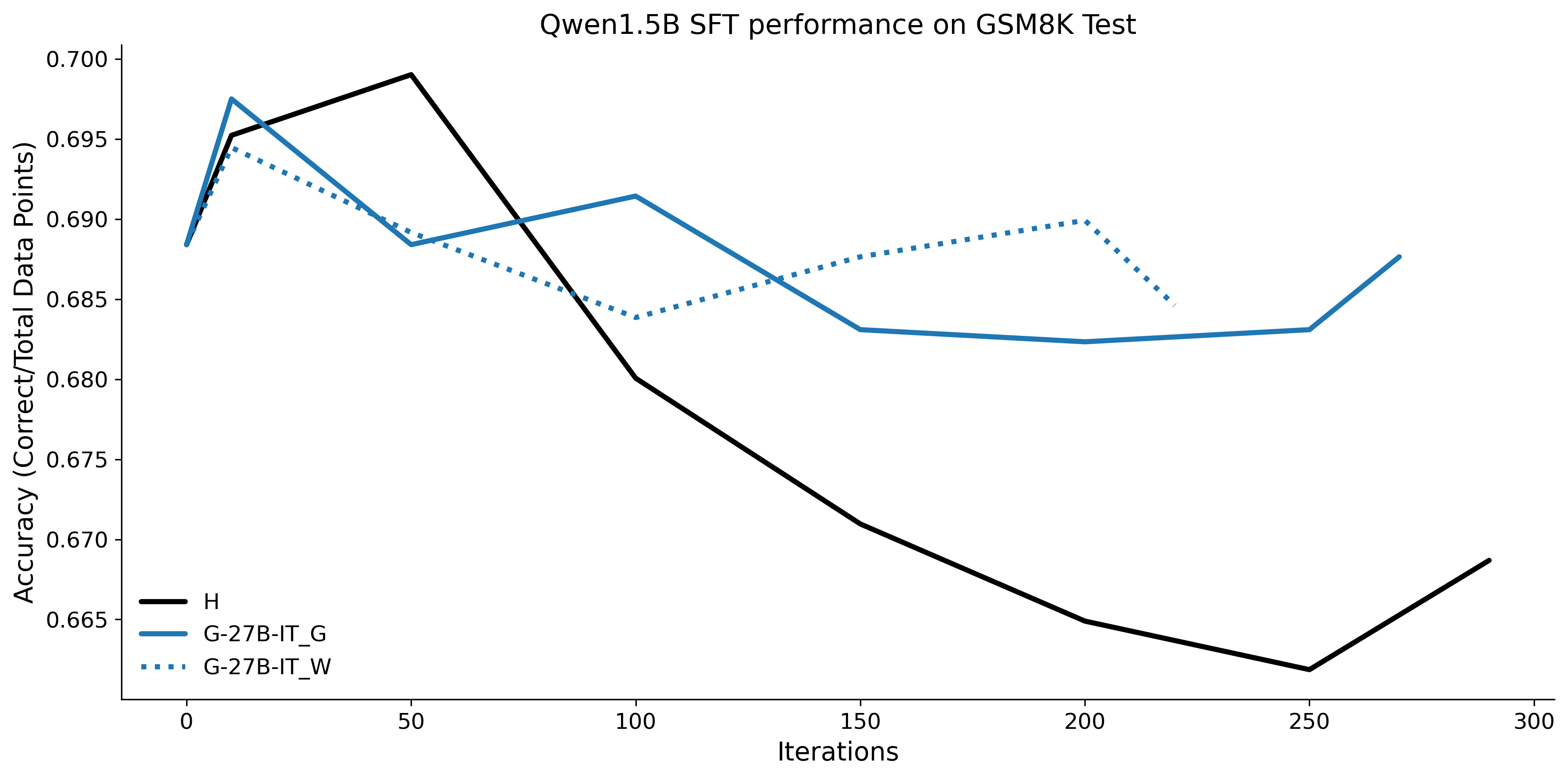

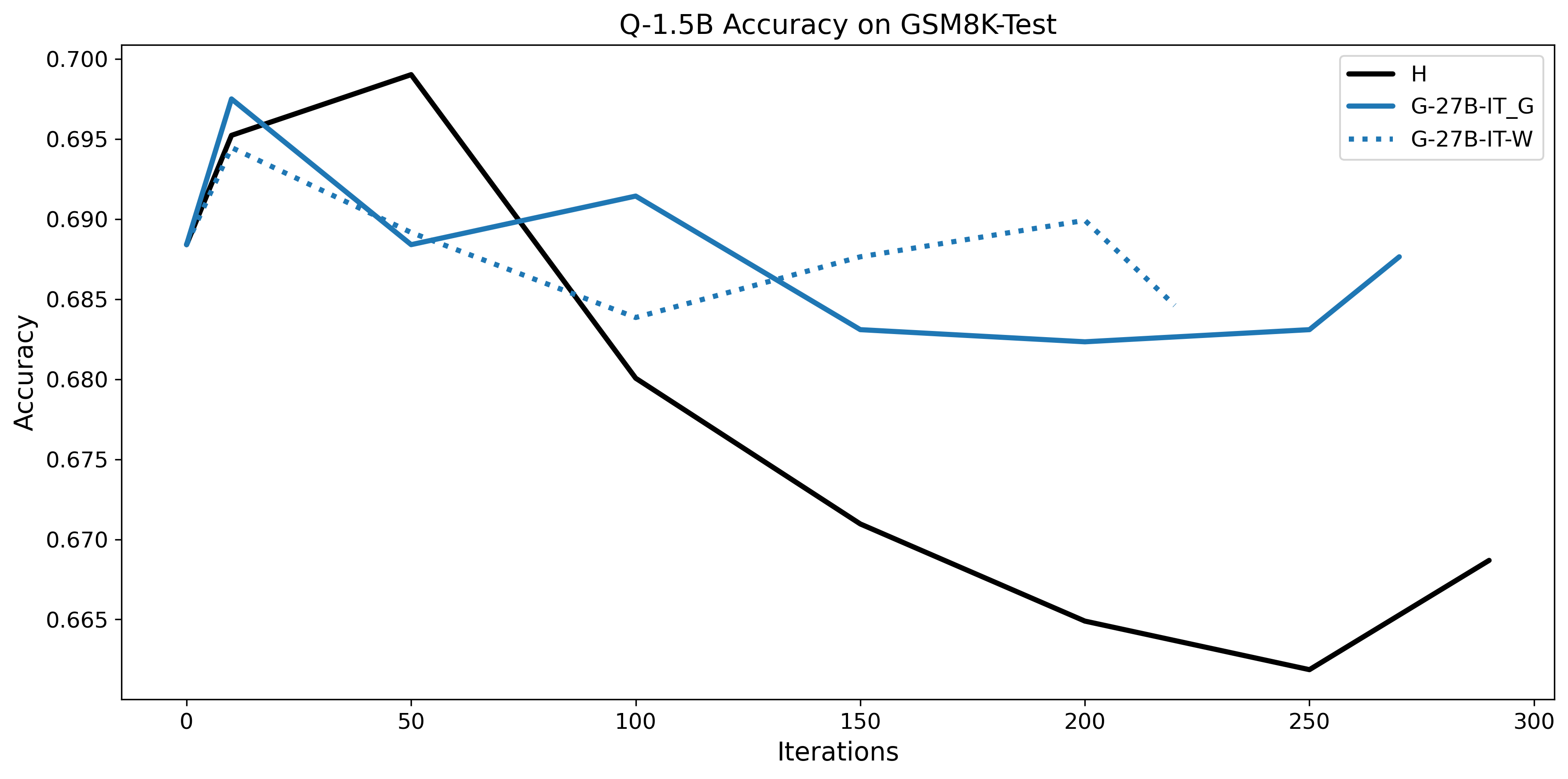

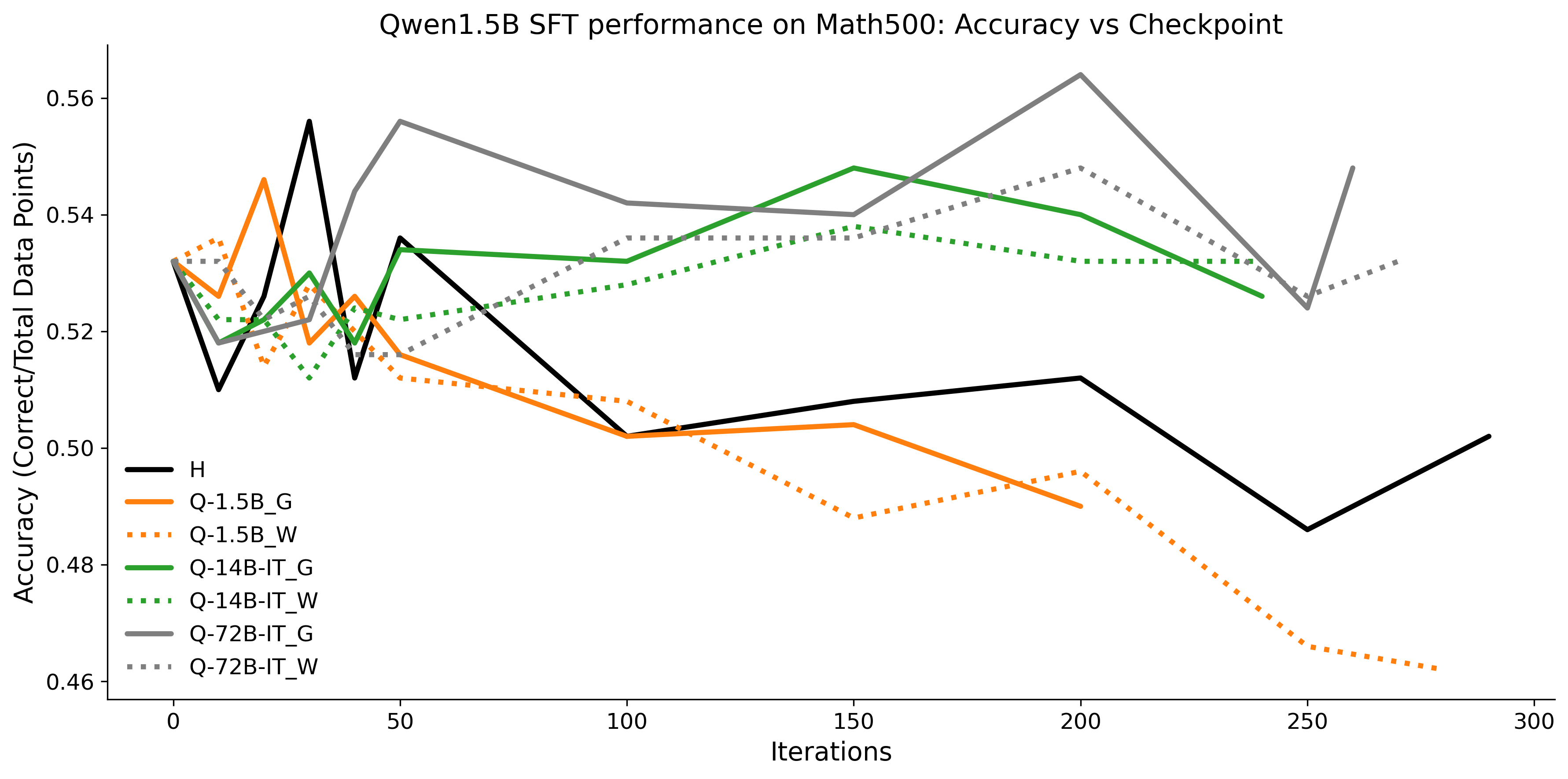

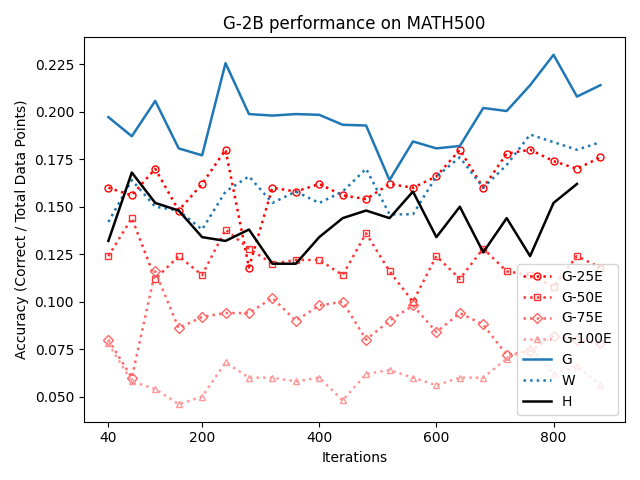

To investigate the above questions, we conduct a systematic study of supervised fine-tuning (SFT) on reasoning traces across categories (1), (2), and (3) above. Our experiments cover multiple reasoning benchmarks -MATH (Hendrycks et al., 2021b), GSM8K (Cobbe et al., 2021), Countdown (Pan et al., 2025), and MBPP (Austin et al., 2021) -and three model families ranging from 1.5B to 9B parameters (Gemma (Team et al., 2024), Llama (Grattafiori et al., 2024), Qwen (Qwen et al., 2025)). We generate reasoning traces for Category (2) and Category (3) using the same or more capable language models (LMs). Surprisingly, we find that training with Category (3) data can improve reasoning performance, even more than using human-written correct traces. We also show that paraphrasing human solutions with an LLM can also improve performance by bringing them closer to the model’s distribution. Finally, we design experiments to introduce completely flawed CoTs in our datasets successively to reveal how tolerant models are to errors before the performance starts to diminish.

While recent approaches prioritize correctness, our results highlight an underexplored dimension: closeness to the model’s distribution can matter as much as, or even more than, correctness.

We summarize the main contributions of our work as follows:

• We show that model-generated CoT traces leading to incorrect final answers (Category 3), which are typically discarded, can improve reasoning performance when used for supervised fine-tuning.

• We demonstrate that training data closer to the model’s output distribution, even if imperfect, can be more effective than correct human-written traces that might be further from model’s distribution. • We progressively degrade CoTs to quantify how much incorrect reasoning a model tolerates, before performance degrades -providing insights into the robustness of learning from imperfect data. • We paraphrase human data to better match the model distribution, improving reasoning scores.

• Qualitatively, we analyse CoT traces generated from the models and show that final answer checking is not the most reliable or holistic way to evaluate CoTs.

In this section, we provide the background on improving reasoning in LLMs. We begin by formalizing LLMs and Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) as the learning paradigm. We then show how large neural networks can learn from noisy data and, finally, draw a parallel to the regulariz

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.