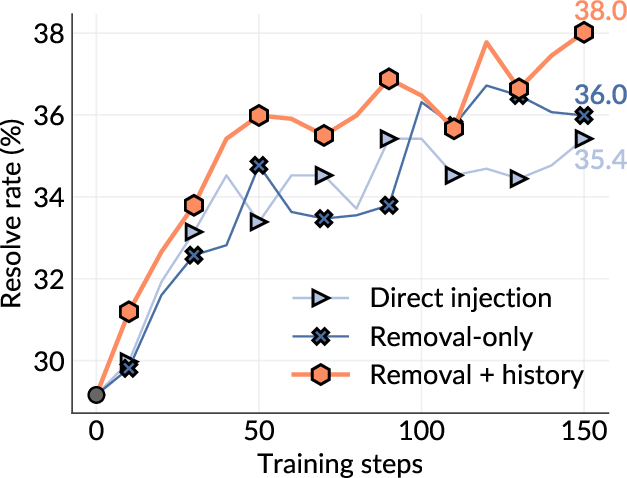

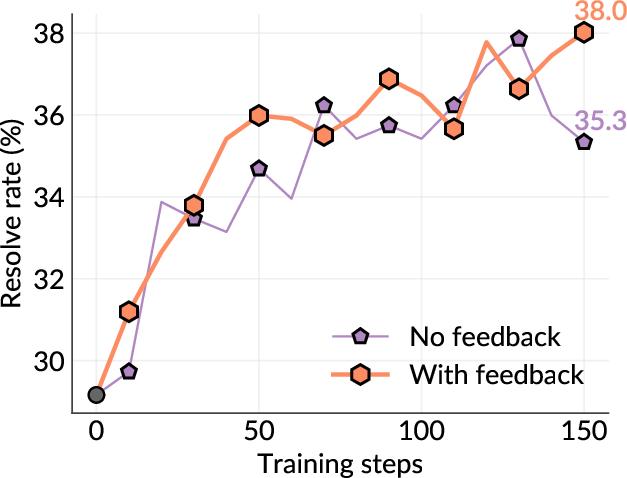

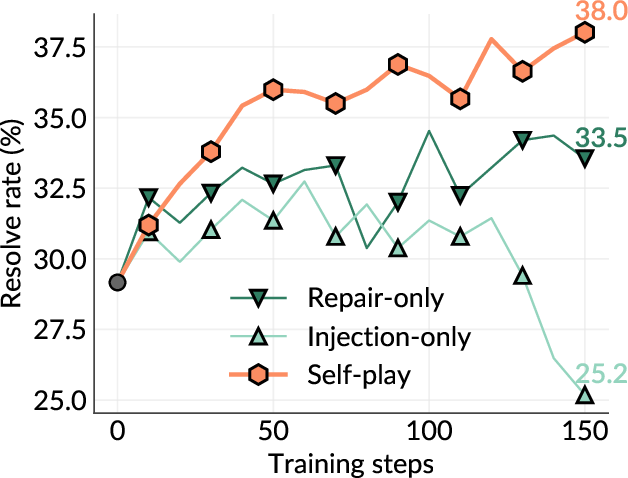

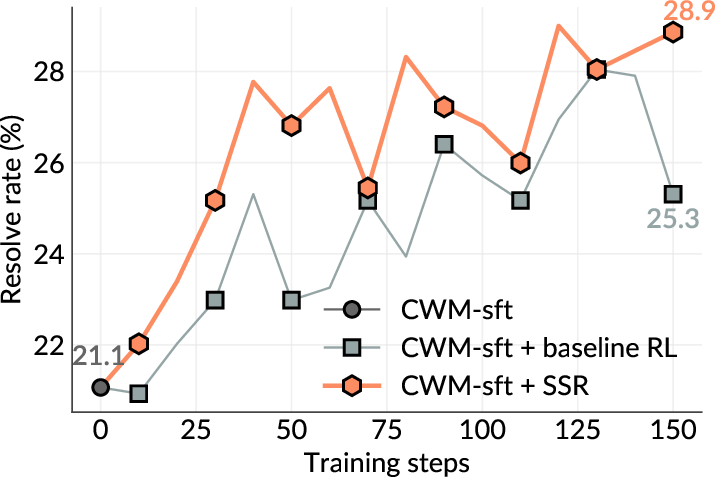

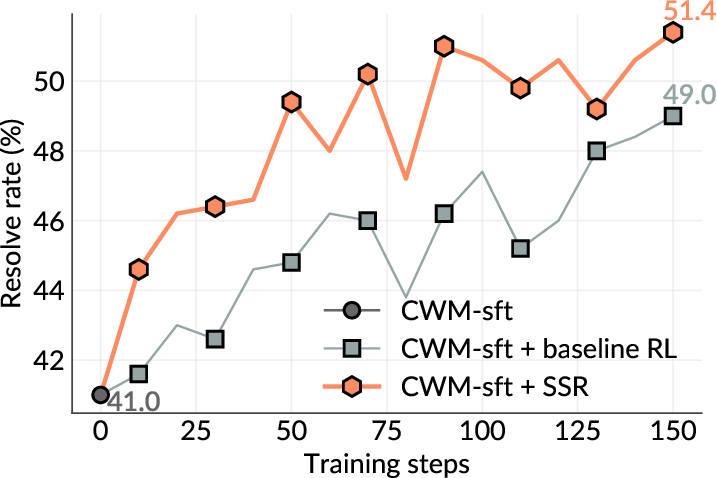

While current software agents powered by large language models (LLMs) and agentic reinforcement learning (RL) can boost programmer productivity, their training data (e.g., GitHub issues and pull requests) and environments (e.g., pass-to-pass and fail-to-pass tests) heavily depend on human knowledge or curation, posing a fundamental barrier to superintelligence. In this paper, we present Self-play SWE-RL (SSR), a first step toward training paradigms for superintelligent software agents. Our approach takes minimal data assumptions, only requiring access to sandboxed repositories with source code and installed dependencies, with no need for human-labeled issues or tests. Grounded in these real-world codebases, a single LLM agent is trained via reinforcement learning in a self-play setting to iteratively inject and repair software bugs of increasing complexity, with each bug formally specified by a test patch rather than a natural language issue description. On the SWE-bench Verified and SWE-Bench Pro benchmarks, SSR achieves notable self-improvement (+10.4 and +7.8 points, respectively) and consistently outperforms the human-data baseline over the entire training trajectory, despite being evaluated on natural language issues absent from self-play. Our results, albeit early, suggest a path where agents autonomously gather extensive learning experiences from real-world software repositories, ultimately enabling superintelligent systems that exceed human capabilities in understanding how systems are constructed, solving novel challenges, and autonomously creating new software from scratch.

Software engineering agents [49,43,1,54,47,48,53,29,52,14,38,12] based on large language models (LLMs) have advanced rapidly and are boosting developer productivity in practice [15]. To improve LLMs' agentic ability, reinforcement learning (RL) with verifiable rewards has become the focal point. SWE-RL [45] is the first open RL method to improve LLMs on software engineering tasks using rule-based rewards and open software data. Since then, a variety of open LLMs focused on agentic RL have been released, including DeepSWE [29], DeepSeek V3.1 [2], MiniMax M1/M2 [7], Kimi K2 [22], and Code World Model [14]. However, both the data and the environments used to train these agents, such as the issue descriptions and test cases, are heavily based on human knowledge or annotations. Even with RL applied, the resulting agents primarily learn to replay and refine human software development traces rather than independently discovering new classes of problems and solutions. Moreover, such curated training signals can be unreliable without extensive human inspection, as evidenced by the need for human-verified evaluation subsets like SWE-bench Verified [3]. Consequently, this dependence on human knowledge and curation is unlikely to scale indefinitely, making it difficult for software agents to achieve the open-ended or superintelligent capabilities that purely self-improving systems might attain.

Although recent efforts such as SWE-smith [50] and BugPilot [37] explore the use of LLMs for large-scale synthetic bug generation, these methods often hold stronger human-data assumptions, such as access to test suites and parsers, thus suffering the same aforementioned scalability limitations, and depend on teacher models for distillation. In addition, such existing methods typically rely on static bug generation pipelines without any consideration of the model being trained, limiting their ability to generate maximally informative examples as the agent improves. As a result, the system cannot continually self-improve.

In contrast, some of the most compelling examples of superintelligent AI arise from self-play. Following AlphaGo [35], AlphaZero [36] achieves self-improvement in Go, chess, and shogi through self-play with only the game rules as input, showing that exploring and exploiting the implications of these game rules using RL can reach superhuman play. Recently, researchers have started to adopt self-play in open domains [55,18,24,25,8,27,17], some impressively but implausibly using nearly zero external data and relying on LLM introspection instead. Absolute Zero [55] trains a single reasoning model to propose coding tasks that maximize its own learning progress and improves reasoning by solving them. Similarly, R-Zero [18] co-evolves a challenger and a solver to improve LLMs’ reasoning on multiple domains. LSP [24] also shows that pure self-play can enhance LLMs’ instruction-following capability. However, such “zero” self-play cannot acquire knowledge beyond the fixed environment rules and the model’s existing knowledge. Instead, SPICE [26] performs corpus-grounded self-play to interact with the external world for diverse feedback, which improves LLMs’ general reasoning ability and outperforms ungrounded methods. For a thought experiment, consider what a human can learn by only interacting with the Python interpreter like in Absolute Zero. While they can learn all the intricacies of Python, they cannot learn the much greater knowledge and experiences contained in real-world codebases but cannot be inferred from Python semantics. This raises a natural question for software engineering: can we build software agents that, grounded in extensive real-world repositories, learn primarily from their own interaction with diverse code environments rather than from human-curated training data?

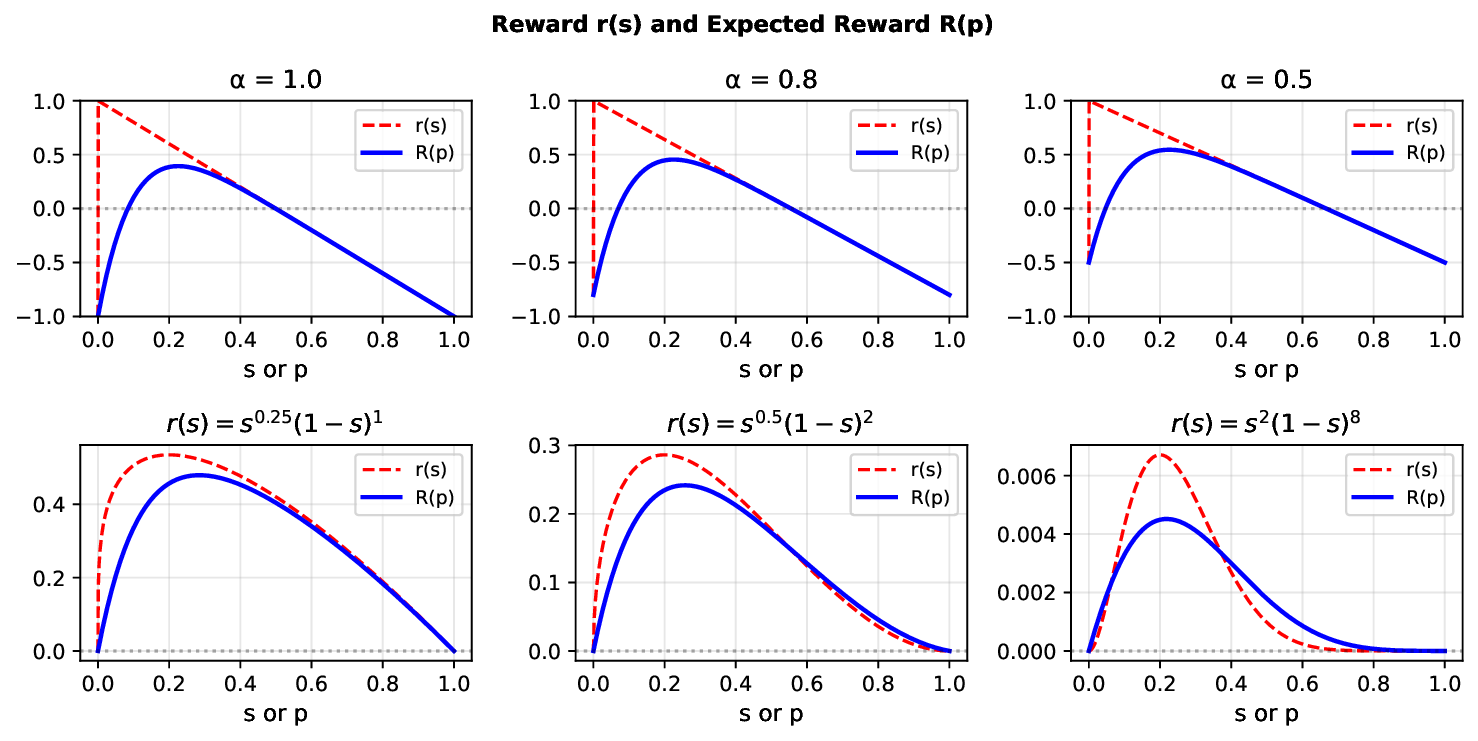

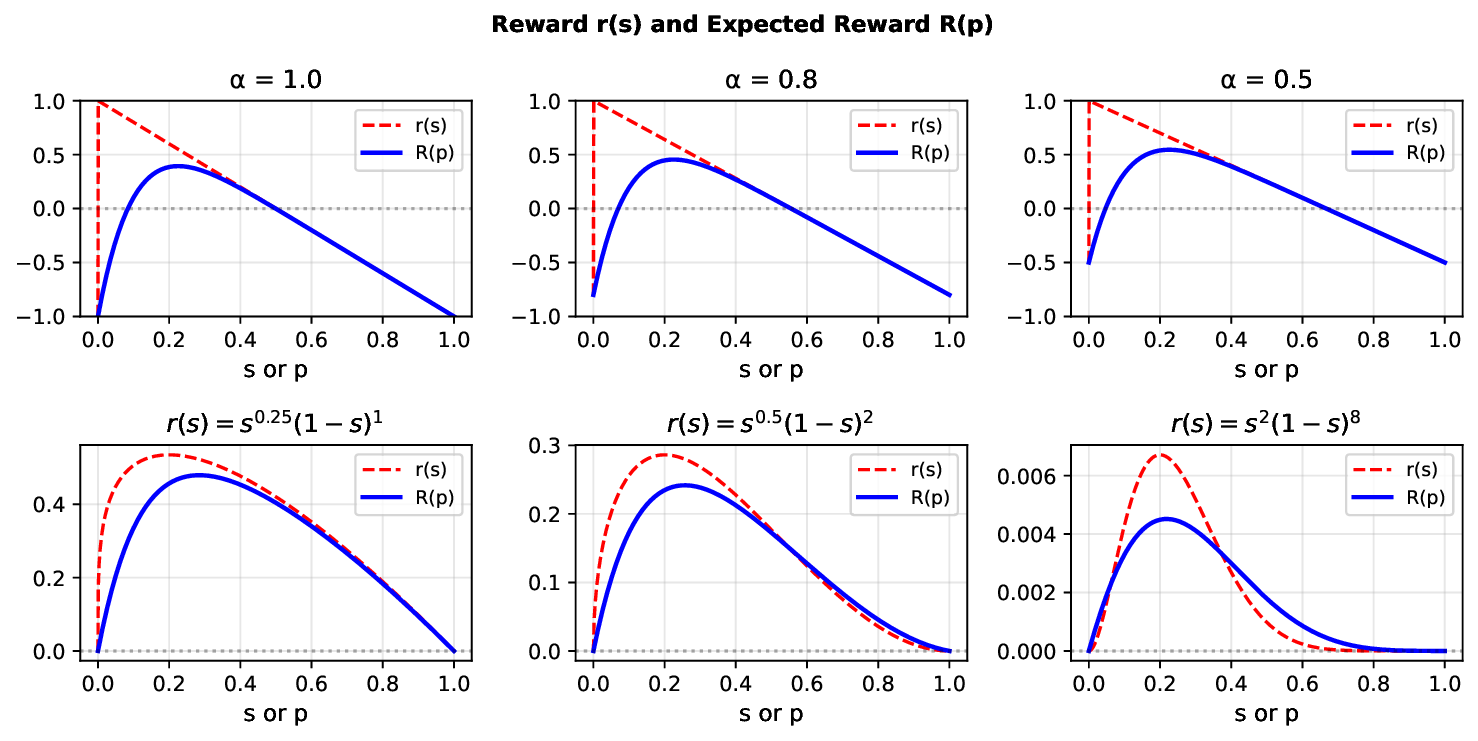

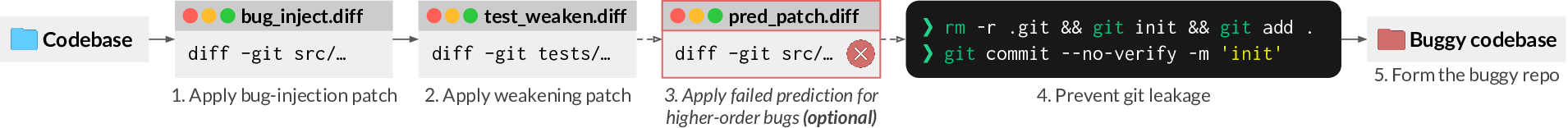

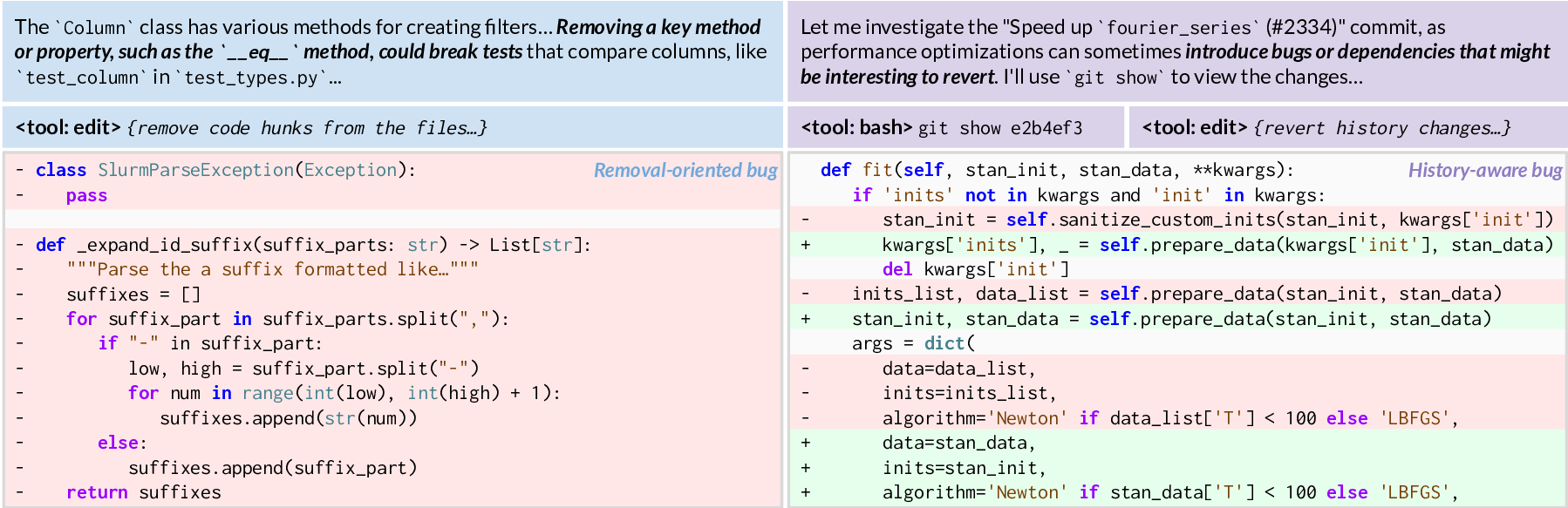

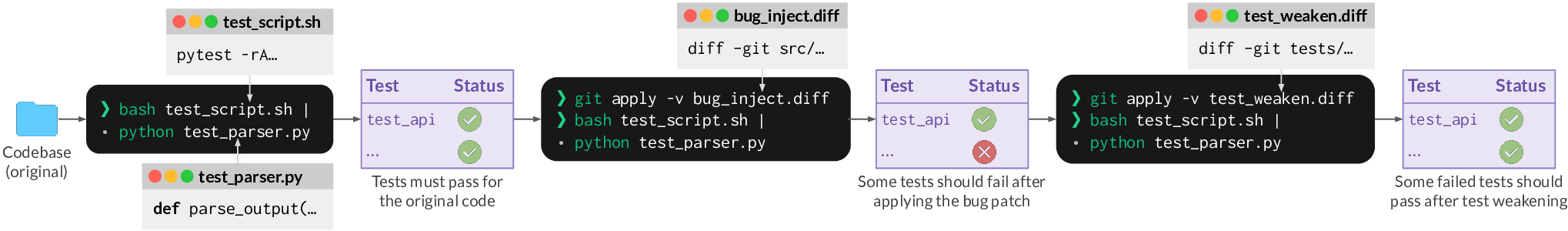

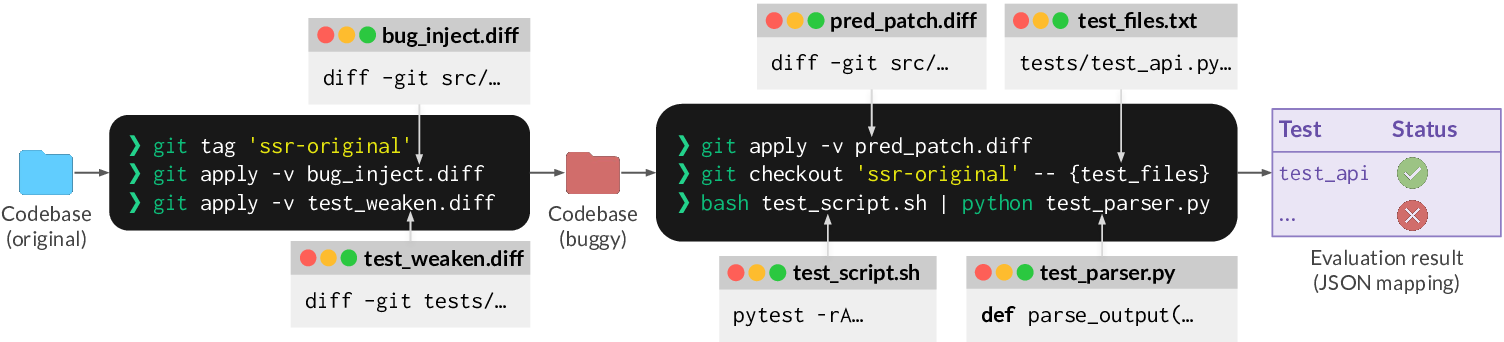

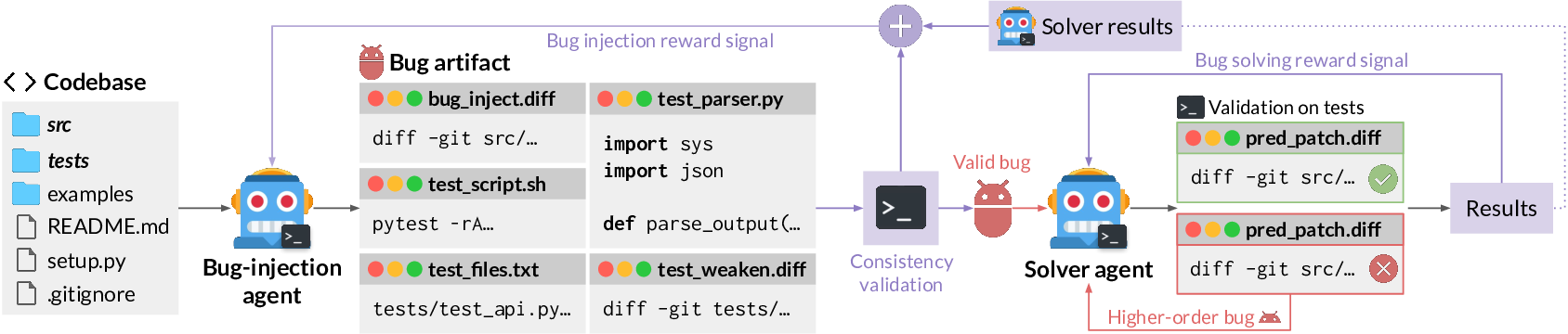

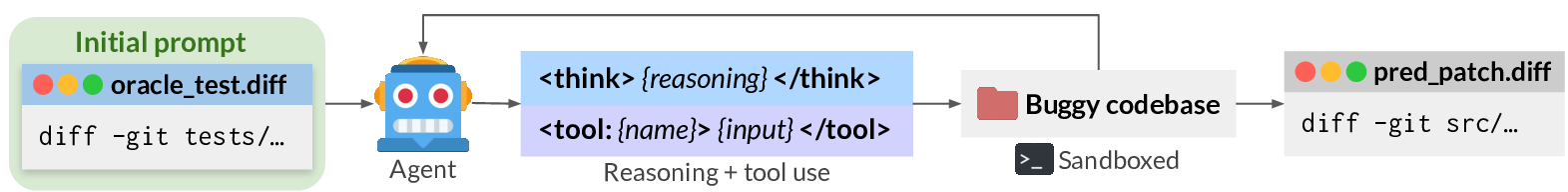

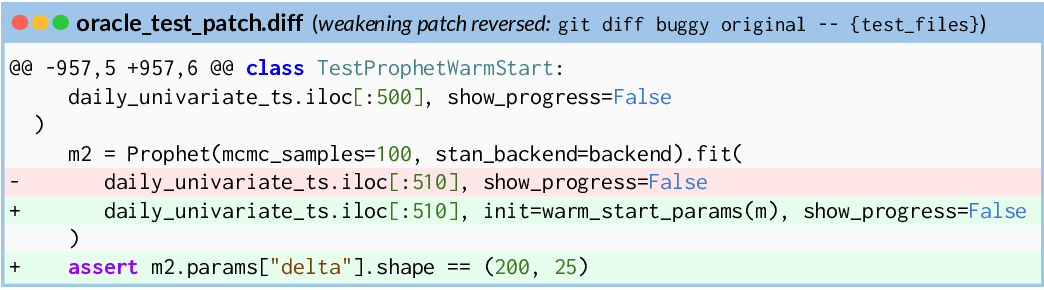

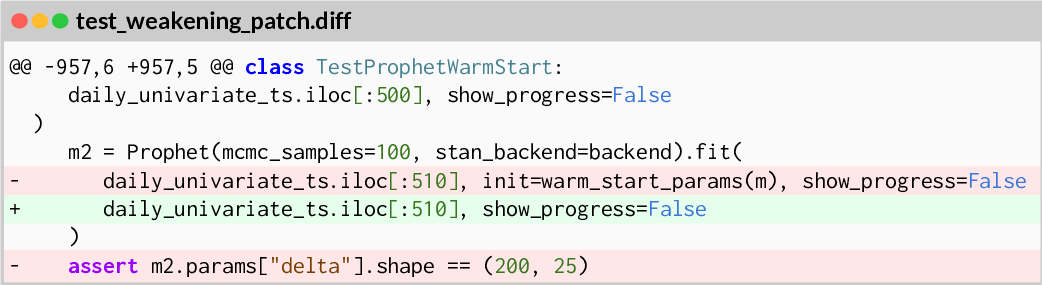

Inspired by these developments, we propose Self-play SWE-RL (SSR), a first step toward superintelligent software engineering agents that learn from their own experience grounded by raw codebases. SSR assumes only access to a corpus of sandboxed environments, each containing the source repository and its dependencies, without any knowledge about existing tests, test runners, issue descriptions, or language-specific infrastructure. In practice, each input to SSR consists solely of a pre-built Docker image. As shown in Figure 1, a single LLM policy is instantiated in two roles by different prompting: a bug-injection agent and a bug-solving agent, both having access to the same set of tools adapted from Code World Model (CWM) [14], including Bash and an editor. When the model plays the bug-injection role, it explores the repository, discovers how to run tests, and constructs a bug artifact that formally specifies a bug via a standard suite of artifacts: (1) a bug-inducing patch over code files, (2) a test script, (3) test files, (4) a test parser script, and (5) a test-weakening patch over test files. These artifacts are validated through a

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.