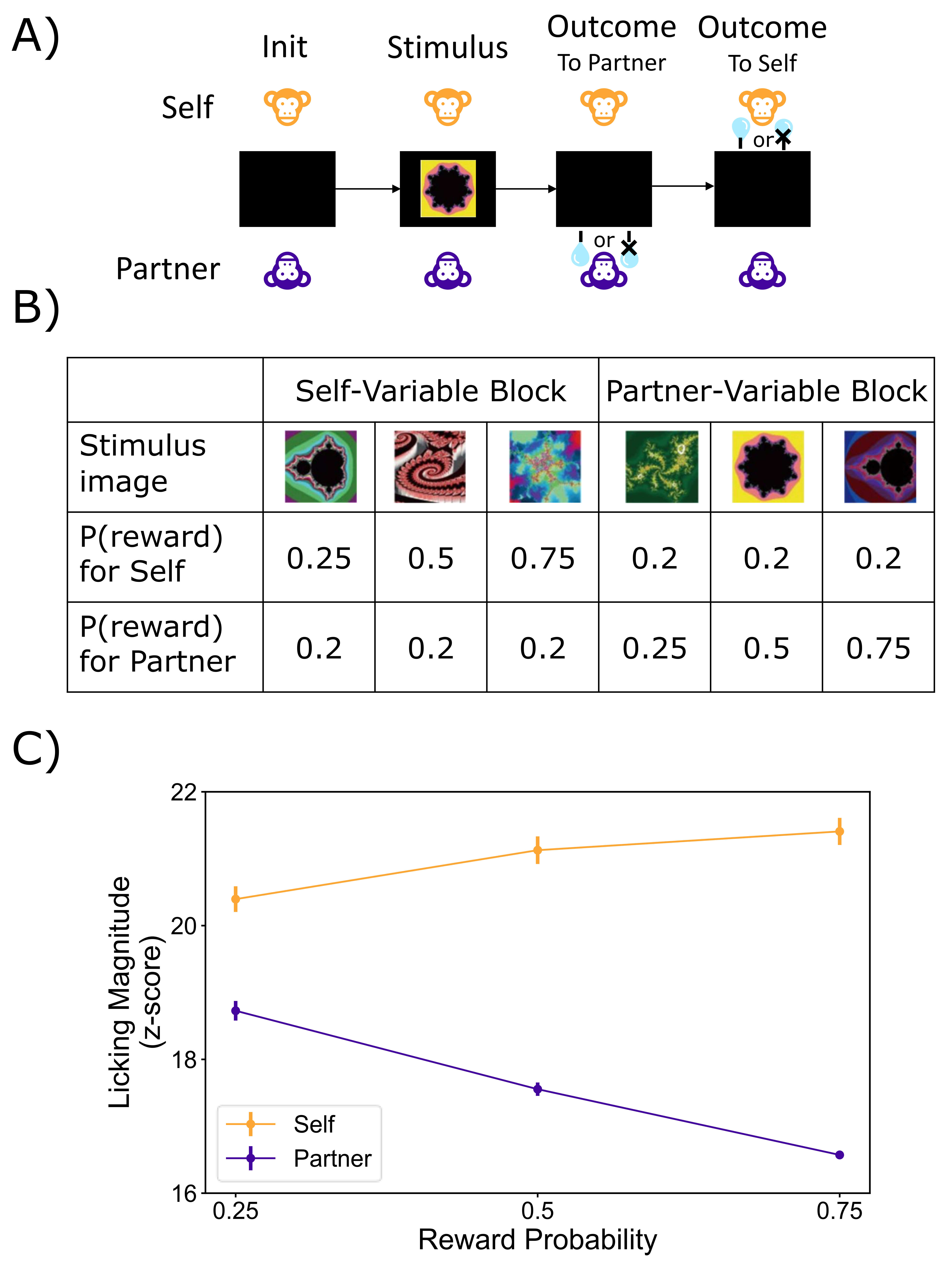

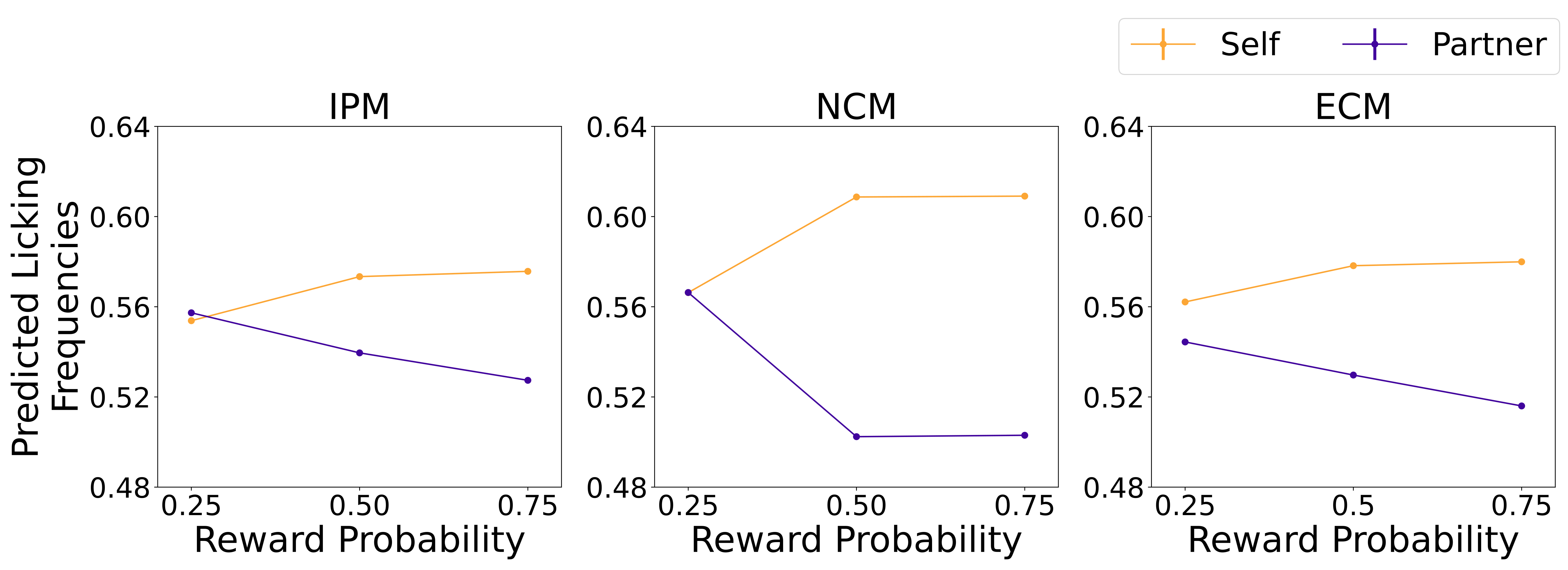

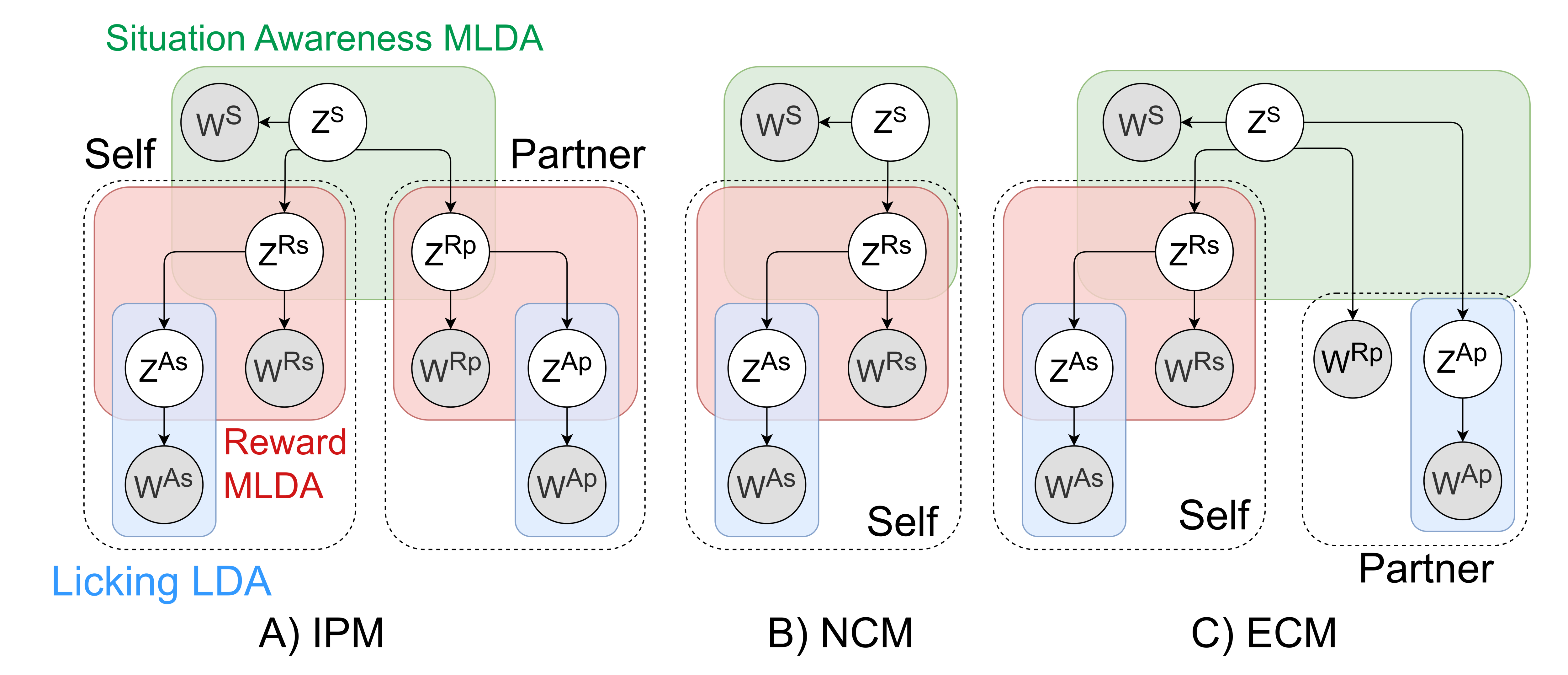

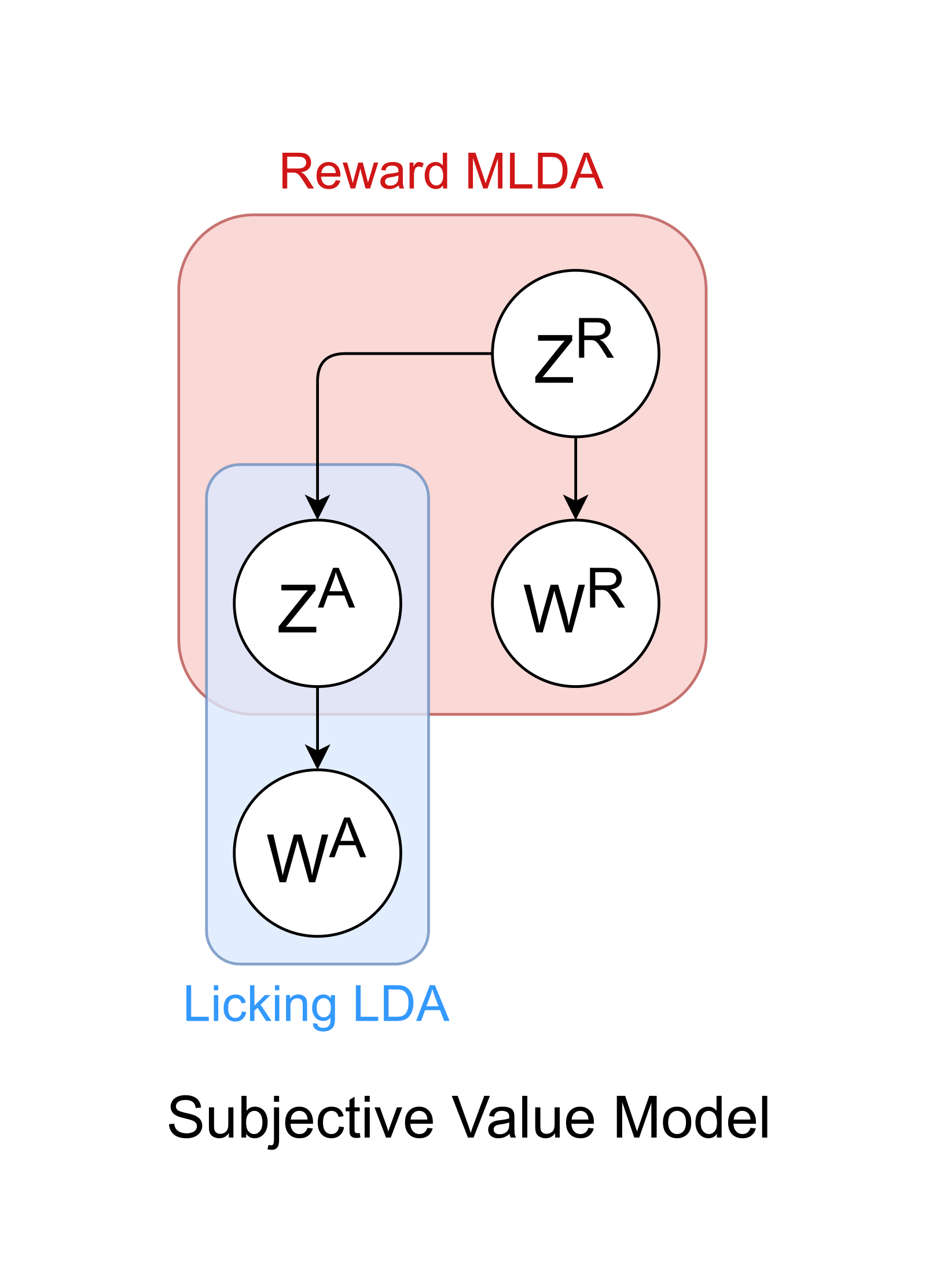

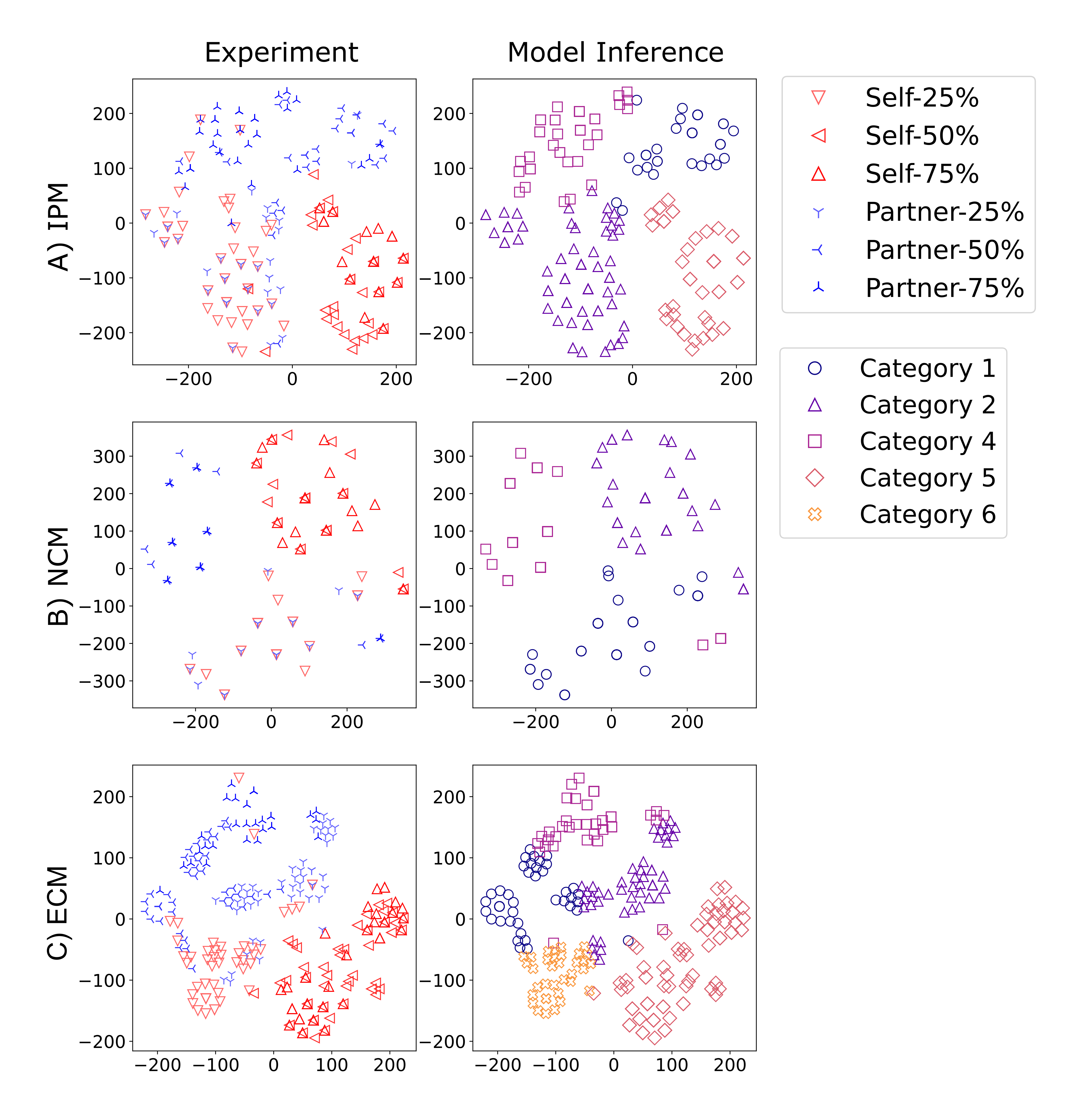

Social comparison$\unicode{x2014}$the process of evaluating one's rewards relative to others$\unicode{x2014}$plays a fundamental role in primate social cognition. However, it remains unknown from a computational perspective how information about others' rewards affects the evaluation of one's own reward. With a constructive approach, this study examines whether monkeys merely recognize objective reward differences or, instead, infer others' subjective reward valuations. We developed three computational models with varying degrees of social information processing: an Internal Prediction Model (IPM), which infers the partner's subjective values; a No Comparison Model (NCM), which disregards partner information; and an External Comparison Model (ECM), which directly incorporates the partner's objective rewards. To test model performance, we used a multi-layered, multimodal latent Dirichlet allocation. We trained the models on a dataset containing the behavior of a pair of monkeys, their rewards, and the conditioned stimuli. Then, we evaluated the models' ability to classify subjective values across pre-defined experimental conditions. The ECM achieved the highest classification score in the Rand Index (0.88 vs. 0.79 for the IPM) under our settings, suggesting that social comparison relies on objective reward differences rather than inferences about subjective states.

Social comparison, introduced by Festinger et al. [1], is the comparison of one's rewards with others'. It clearly has a critical social role because it enables individuals to assess their abilities and the resources they possess, including social status. Interestingly, social comparison also occurs in non-human primates: macaque monkeys exhibit behavioral markers of social comparison, such as changes in anticipatory licking, and neural correlates in midbrain dopaminergic neurons [2]. However, a particular challenge in studying social comparison in non-human primates is that they cannot verbally report their subjective experiences and internal states. To address this issue, robotics research using interpretable computational models presents an intriguing methodology for elucidating the cognitive mechanisms underlying social comparison by fitting the models to behavioral and other observable data.

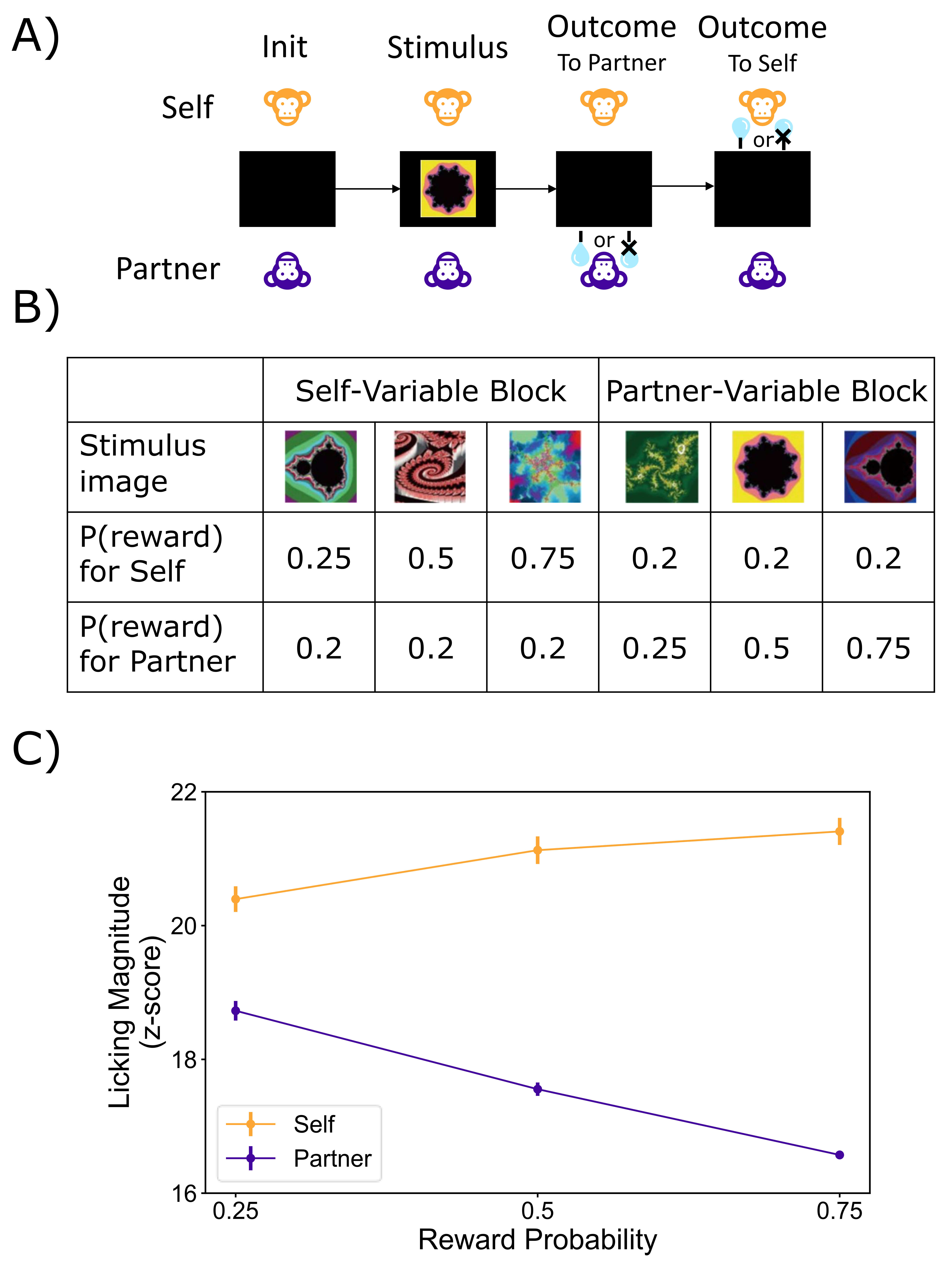

A key finding of social comparison in monkeys is that while objective rewards remain constant, the subjective value that monkeys assign can vary depending on the context [2]. In experiments where monkeys repeatedly received rewards in the presence of a partner, the subjective value of the rewards declined as the partner’s reward probability increased, despite the objective amount of outcomes remaining constant for the monkey itself. This shift was confirmed neurally and behaviorally through altered activation of midbrain dopaminergic neurons and corresponding changes in anticipatory behavior [2]. The experiment demonstrated subjective valuation in monkeys but did not address their inference of the partner’s subjective value. We therefore investigate whether monkeys can infer their partner’s reward valuations, given evidence that monkeys exhibit theory of mind abilities-attributing beliefs distinct from their own and predicting others’ actions [3]. If monkeys can represent others’ mental states, they may infer the value a partner assigns to a reward and incorporate this inference into their own valuation during social comparison.

Despite extensive research on social comparison in primates, few studies directly examine whether non-human primates understand others’ subjective reward valuations. Significant progress-e.g., by Noritake et al. [2,4]-has clarified how primates monitor and evaluate their own rewards relative to others, yet evidence for representations of others’ subjective valuations remains scarce. Computational research focusing on this topic is also lacking, while two prior computational studies have explored related questions [5,6]. Zaki et al. [5] combined fMRI with reinforcement learning models to demonstrate that humans can estimate others’ emotional states, which may involve the other’s subjective valuation; their paradigm, however, centered on empathic emotion inference rather than on valuation changes from reward comparison. Devaine et al. [6] investigated non-human primates’ (including macaques) theory of mind ability in terms of how they infer their partner’s actions in competitive games. Therefore, neither of the studies directly examined how an agent’s inference about a partner’s subjective value influences its own valuation during social comparison, which is the focus of this study. Consequently, the computational principles linking a represented other-value to one’s own subjective value remain largely unexplored.

Given the limited research on inferring the subjective value of others in social comparison settings, the present study asks: when a monkey compares its reward with a partner’s, is its subjective value influenced by an inference about the partner’s subjective valuation, or is it determined solely by the objective reward difference?

The limited investigation of this question reflects the inherently analytic focus of most neuroscientific approaches, which isolate specific neural or behavioral activities from complex cognitive systems. As shown by Noritake et al. [2,4], these studies examined causal interactions among brain regions-the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), lateral hypothalamus, and dopaminergic midbrain nuclei. Although such analyses reveal necessary neural conditions for social comparison, these components alone constitute a sufficient cognitive mechanism deployable in robotic systems. Moreover, causal approaches are less suited for examining internal representations-such as those inferred about subjective valuations of others-especially when their neural correlates are unknown.

This study adopts a constructive approach that complements analytical methods by building and analyzing artificial systems to clarify a comprehensive understanding of the target mechanisms [7,8]. Using computational model selection with behavioral and perceptual data from primates, we identify frameworks that best explain observed patterns. This approach is particularly effective for examining internal representationssuch as how inferences about others’ valuations shape one’s subjective value-

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.