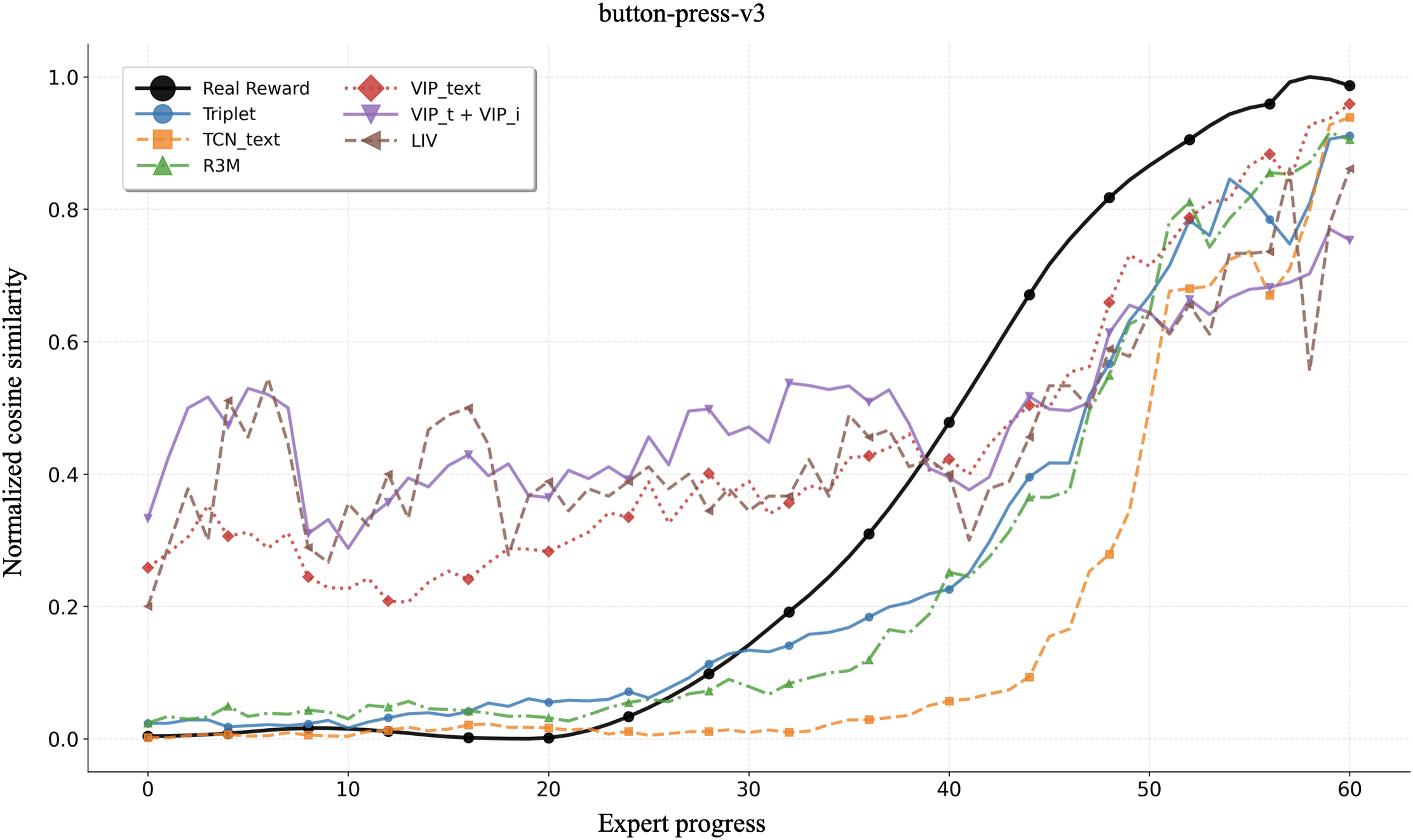

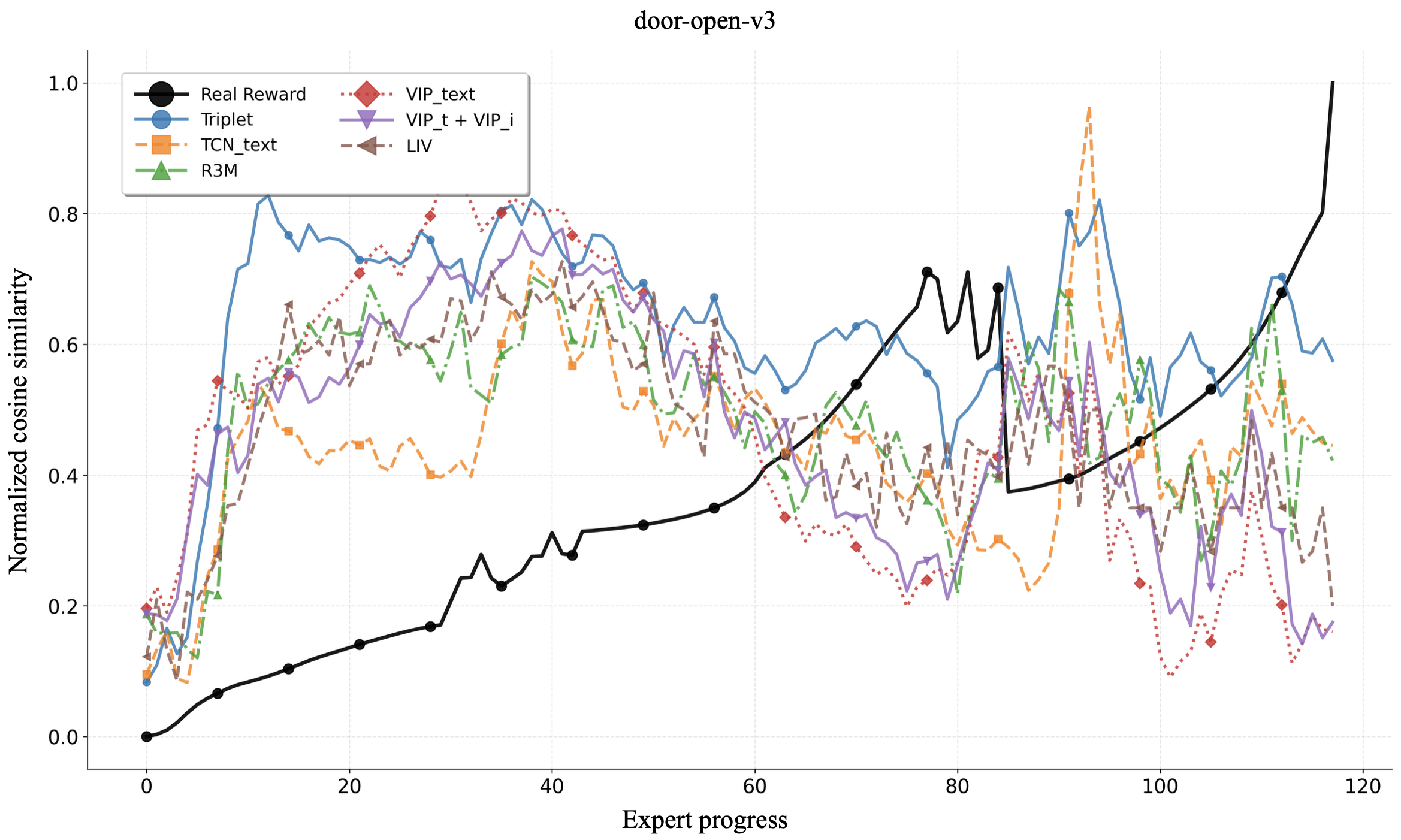

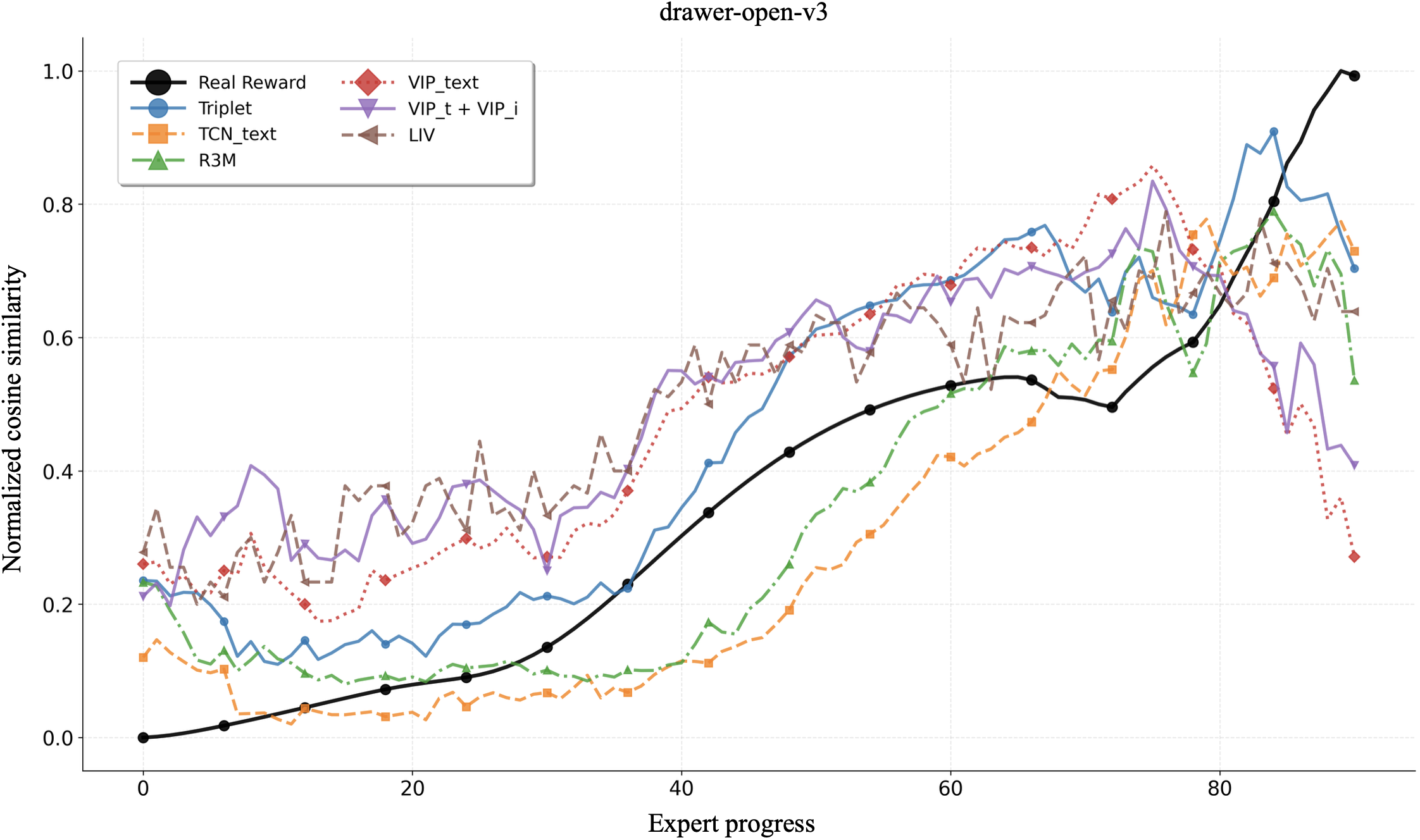

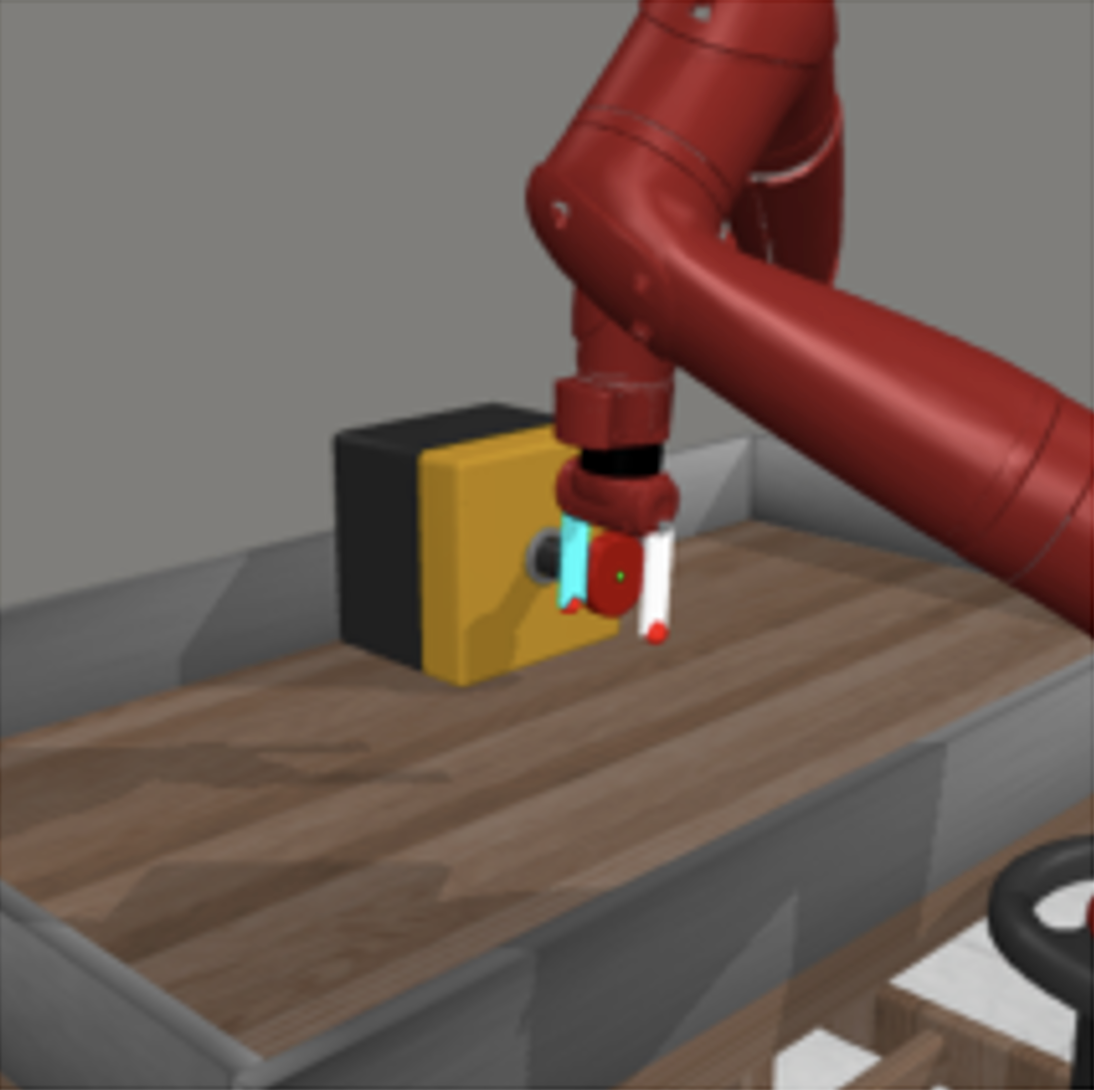

Learning generalizable reward functions is a core challenge in embodied intelligence. Recent work leverages contrastive vision language models (VLMs) to obtain dense, domain-agnostic rewards without human supervision. These methods adapt VLMs into reward models through increasingly complex learning objectives, yet meaningful comparison remains difficult due to differences in training data, architectures, and evaluation settings. In this work, we isolate the impact of the learning objective by evaluating recent VLM-based reward models under a unified framework with identical backbones, finetuning data, and evaluation environments. Using Meta-World tasks, we assess modeling accuracy by measuring consistency with ground truth reward and correlation with expert progress. Remarkably, we show that a simple triplet loss outperforms state-of-the-art methods, suggesting that much of the improvements in recent approaches could be attributed to differences in data and architectures.

The increasing momentum of embodied intelligence has motivated the study of generalizable reward models that do not rely on hand-crafted human supervision. Recent work leverages large vision-language models (VLMs) as general-purpose reward functions that measure progress through alignment between visual observations and language goals. Rocamonde et al. (2024) showed that CLIP (Radford et al., 2021) can be used as a zero-shot reward model for downstream policy learning, though it struggles with domain shift related to action specification and environmental dynamics. To mitigate this effect, many methods have turned to large-scale video demonstration datasets (Damen et al., 2018;Grauman et al., 2022) to finetune VLMs, enabling a better understanding of task-relevant behaviors. Nevertheless, the question of extracting meaningful signals of task progress from video demonstrations remains a central challenge to vision-language reward modeling. As a result, increasingly complex learning objectives have been proposed to generate more accurate rewards (Sermanet et al., 2018;Nair et al., 2022;Ma et al., 2023b;a;Karamcheti et al., 2023). However, most of these methods were pre-trained using different datasets and architectures, making it difficult to isolate the choice of learning objective from downstream performance. For instance, R3M (Nair et al., 2022) was pre-trained on Ego4D (Grauman et al., 2022) yet compares to methods pre-trained on ImageNet (Russakovsky et al., 2015;Parisi et al., 2022). LIV (Ma et al., 2023a) was initialized with CLIP weights and pre-trained on EpicKitchen (Nair et al., 2022) yet compares to methods utilizing a frozen BERT encoder Devlin et al. (2019) and vision encoder pre-trained on Ego4D from scratch (Nair et al., 2022).

In this work, we systematically compare objectives under a unified framework, holding the pretrained model backbone, finetuning data, and downstream evaluation environments constant. This setup allows us to decouple the impact of the learning objectives from any other confounding factors. We assess model performance via two distinct benchmarks, evaluating consistency with ground truth reward and alignment with expert progress. While initially introduced as a minimal baseline for comparison with recent methods, our results show that a very simple triplet loss Schroff et al. (2015) can surpass current state-of-the-art learning objectives. More broadly, our findings indicate that simpler ranking-based learning objectives offer greater accuracy and robustness, suggesting that much of the apparent progress in recent methods could instead be due to differences in data and model architecture.

State-of-the-art contrastive reward modeling approaches rely on combinations of learning objectives, either in their original form or adapted for alignment with language. For our experiments, we focus on a set of loss functions that can be used to reproduce many popular reward models.

TCN (Sermanet et al., 2018) reduces the embedding distance of images which are closer in time and increases the distance of images which are temporally further apart. Given an image encoder π img , a sequence of images {I t } k t=0 , their corresponding encodings z t = π img (I t ), batches of [I i , I j>i , I k>j ] 1:B and a similarity function S, TCN minimizes the following objective:

We adapt L TCN to language by replacing I k>j with the language annotation for the given sequence.

Inserting the language embedding v = π text (l) results in the following objective

(2)

) uses a goal-conditioned approach that separates embeddings of temporally adjacent images while bringing together embeddings of images that are farther apart in time. Given batches of [I i , I j>i , I j+1 , I k≥j+1 ] 1:B , VIP is defined as:

Just like TCN, we adapt L VIP to language by replacing I k>h with the embedded language annotation v = π text (l) for the given sequence.

Combinations of these losses reproduce popular reward modeling methods minus regularization terms. R3M is obtained by combining both TCN versions:

(5) Note that R3M adapts TCN to language by training an MLP to predict a similarity score from the concatenated vector [z 0 , z i , v], where z 0 is the first image in the sequence. This approach introduces a non-negligible amount of additional parameters, especially for large embeddings like those from SigLIP2. For fairness, we omit the initial embedding in our setup.

LIV is a combination of both VIP versions plus an InfoNCE objective (Oord et al., 2018), the latter which we also include in our experiments:

Triplet (Schroff et al., 2015) applied to this context reduces the embedding distance between the language goal and the later images of the sequence, and pushes earlier images further away. We propose it as a simple baseline for task progress and show its remarkable effectiveness. Given batches of [I i , I j>i , l] 1:B , we use the language annotation as the anchor, the later image as the positive and the earl

This content is AI-processed based on open access ArXiv data.